The business model innovations that we described in Chapters 3 and 4 are important elements of a strategy to reduce the cost, increase the quality, and improve accessibility of health care. But the business model innovations for the treatment of chronic disease that we describe in this chapter are perhaps the most important innovations of all.

Ninety million Americans currently have chronic conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, arthritis, and dementia. More than one-third of young adults aged 18 to 34, two-thirds of adults aged 45 to 64, and nearly 90 percent of the elderly have at least one chronic disease.1 Acute conditions like infectious diseases, trauma, and maternity care create real costs, of course. But chronic disorders account for three-quarters of direct medical care costs in the United States. And of the myriad chronic diseases, five of them—diabetes, congestive heart failure, coronary artery disease, asthma, and depression—account for most of these costs.2 Many often have their genesis in two other chronic illnesses, obesity and tobacco addiction. A key reason why such a large share of our health-care dollars is spent during the last 18 months of life is that this is when the complications of chronic disease have finally set in with a vengeance.3

In sum: any program for resolving our runaway health-care costs that does not have a credible plan for changing the way we care for the chronically ill can't make more than a small dent in the total problem.

Chronic illness is a relatively new phenomenon, because only recently has technological progress transformed many once-fatal diseases into chronic ones. Before the 1920s, for example, childhood-onset diabetes was an acute disease: those diagnosed with it died within a few months. But the ability to inject animal and now biosynthetic insulin has transformed Type I diabetes from an acute, fatal disease into a chronic condition. Coronary artery disease was largely an acute illness until the 1970s. It went largely undiagnosed until patients experienced, and often died from, a heart attack. Bypasses, stents, and statins have now transformed heart disease into a chronic condition. AIDS and some cancers have been transformed into chronic conditions in just the past decade. New drugs and devices are changing multiple sclerosis and cystic fibrosis from recurring, ultimately fatal episodes of acute illness into diseases whose victims can experience a better quality of life.

Though these triumphs are a cause for celebration, the number of patients who live with a chronic disease, the growth rate of that number, and the cost of their ongoing health maintenance over ever-longer periods of time are staggering.4 A key contributor to this costliness, however, is that the primary business models being used to care for these patients—physicians' practices and hospitals—were primarily set up to deal with acute diseases. They make money when people are sick, not by keeping them well. There are more than 9,000 billing codes for individual procedures and units of care. But there is not a single billing code for patient adherence or improvement, or for helping patients stay well.5

Rather than hoping that improving the efficiency of caregivers working within these business models will solve these problems, a more robust solution must be found by creating new business models for managing chronic disease. Exploring these possibilities is the focus of this chapter.

The task in building any valid theory is to define the categories correctly. In the preliminary or descriptive stage of theory building, researchers typically define the categories in their theory according to the characteristics of the phenomena they are studying. They then correlate the presence or absence of those characteristics with the outcomes of interest. A very typical study in business research, for example, would entail categorizing businesses as entrepreneur-funded or venture-capital-backed, and then compare the success rates of the companies in the two groups.

But descriptive theories that emerge from studies such as these can only indicate average tendencies. The predictive power of theory takes a huge leap forward when a researcher moves beyond such descriptive categories and correlations, and discovers the causal mechanisms that underlie the outcomes of interest. This understanding allows a scholar to make precise and predictably effective prescriptions about the actions that will and will not lead to the desired results in the different situations in which people might find themselves.6

The theories that have guided medical practice follow this pattern exactly. Early on, diseases are classified by their characteristics—by their physical symptoms. If the patient is wheezing, we'll call it asthma; if she has elevated levels of blood glucose, we'll call it diabetes; and so on. When medical theory is in this descriptive stage, the practice of medicine must be intuitive or empirical, and outcomes typically can only be expressed in probabilistic terms.

Medical theory takes a giant step forward, however, when scientists can categorize a disease by the different mechanisms that cause sickness or permit wellness. The ability to diagnose by cause rather than characteristics takes the theory about a disease from the descriptive to the prescriptive stage. This is the essence of the transition to precision medicine. In our example above, it can make a life-and-death difference to know if the patient is wheezing because of an allergic reaction, an inflammation of the airways, a foreign body in the airway, or fluid buildup because of a heart problem. Effective treatment hinges on precise definition.

One of the most common categorizations in health care is the distinction between chronic and acute disease: one group of diseases lasts for a long time, the other doesn't. This is a descriptive categorization, however; it tells us little about how to treat these diseases. Chronic diseases differ fundamentally among themselves, and before we can recommend which types of business models can be effective, we first need to define the different groups of chronic diseases that will require different business models.

In the treatment of many acute diseases, because of their relatively brief duration, the same business model can be used for both diagnosis and treatment. This is not the case with chronic diseases, however. The type of business model that is good at diagnosing the disease and prescribing a course of therapy must be different from the model that can most effectively help patients adhere to the therapy and make the behavioral adjustments necessary to live free from the complications of the disease. These are two fundamentally different tasks. In the following discussion, therefore, we'll note how business model innovation can improve the effectiveness and cost of diagnosis and treatment. We'll then explore what kinds of business models should be used to help people adhere to the treatments that have been prescribed. One of our conclusions is that despite the enormity of cost and suffering associated with chronic disease, there actually are very few business models in health care today whose design is optimized to diagnose and prescribe, and to encourage adherence to therapy.

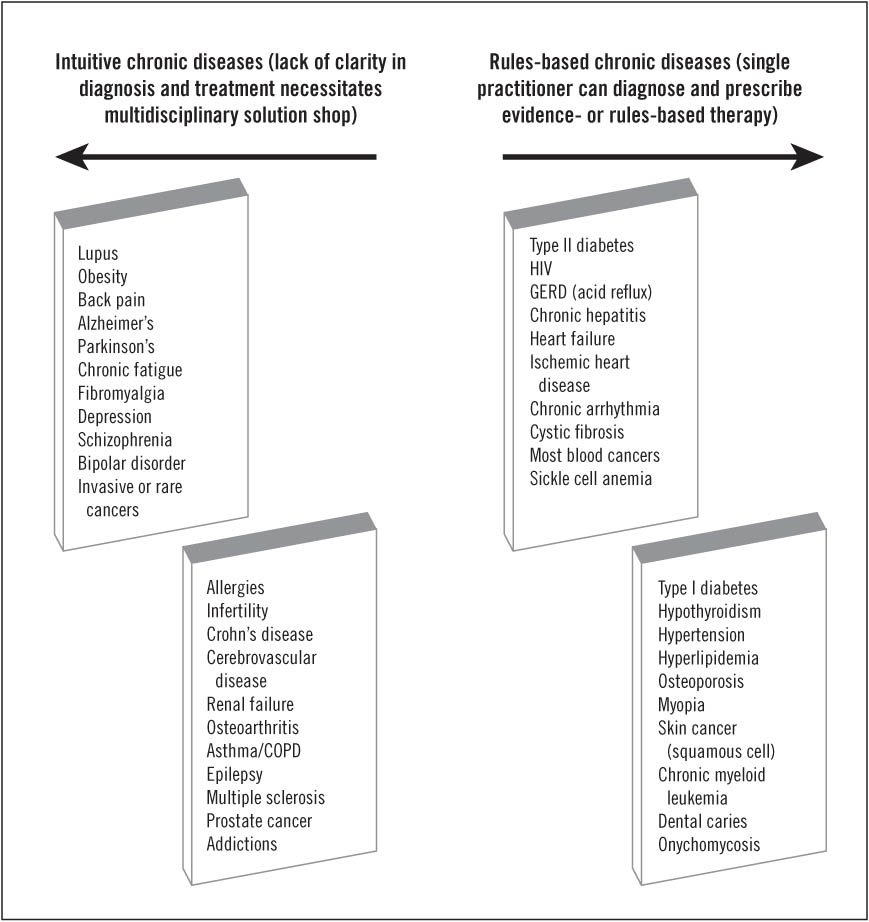

In Figure 5.1 we've grouped a sampling of chronic diseases according to the precision of scientific understanding that underlies the disease, as well as the breadth of subspecialties whose perspectives need to be brought to bear to diagnose the problem and devise an effective therapy. Though experts may disagree with us in the placement of certain diseases, we ask our readers simply to regard these groupings as illustrative only.

We call the diseases on the left side of Figure 5.1 Intuitive Chronic Diseases. We don't know enough about them—because insufficient research has been done to date, often due to lack of funding or awareness, and/or the diseases are inherently complex and require multiple areas of expertise to fully understand.7 We do know two important things, however. First, we know that science will ultimately teach us that each of these "diseases" in truth is a symptom—a broad manifestation of one or more different underlying causal mechanisms. Second, we know that these different causes probably involve multiple organ systems through interdependent molecular pathways, complicated by individual genetic differences and environmental factors. These combine to make diagnosis and treatment extremely complex, limiting the movement toward rules-based care.

FIGURE 5.1 Type of medical practice required to diagnose and devise therapy for a range of chronic diseases

Therefore, to effectively diagnose and prescribe the best course of therapy possible for these intuitive diseases, professionals from multiple medical subspecialties need to interact with each other and, using any available data, intuitively iterate toward the best possible prescription. At the outset, these physicians cannot know which disease truly underlies the presenting symptom, nor can they yet prescribe a predictably effective therapy. Rather, they must synthesize from the data and their multiple perspectives a "differential diagnosis": a hypothesis that is tested by prescribing an experimental course of therapy and seeing what happens. Then they must revise the diagnosis and therapy iteratively, when necessary, until the most effective course of action possible has emerged.

We call the diseases on the right side of Figure 5.1 Rules-Based Chronic Diseases because treatment is in the realm of empirical or precision medicine. The diagnosis and prescription of an effective therapy for rules-based chronic diseases, in contrast to the task with intuitive ones, usually can be competently managed by an individual caregiver. Most of these are not yet in the realm of precision medicine, in that we're not sure of the cause of the symptoms, but most of them ultimately will be sorted into more precisely defined types. For now, however, nearly all of these rules-based diseases are squarely in the empirical mode. Unambiguous measures of the disease-defining symptoms are readily available, and there is clear statistical evidence that if a particular course of therapy is followed, the undesirable symptoms and long-term complications will be minimized, on average, when compared to other therapeutic alternatives. Standardized protocols based on clinical evidence are commonplace for conditions like heart disease (chronic stable angina), diabetes, and congestive heart failure.

The business model to diagnose and arrive at a course of therapy for rules-based diseases exists: it is the traditional physician's practice. In fact, the rules for many of these diseases are now so widely accepted that diagnosis and prescription can be handed off to nurse practitioners without any compromise in outcomes.

There are two costly problems in the way we historically have treated chronic disease. The first is that while effectively treating the diseases on the left side requires the perspectives of multiple specialities, the business models we typically utilize to do this job almost always deploy single practitioners. Recall, for illustration, the account of our friend's struggle with asthma in Chapter 3. It wasn't until he visited the National Jewish Medical and Research Center that a set of practitioners was able to solve his problem by working in an integrated manner. Prior to that visit, our friend had been treated by a plethora of individual physicians in separate specialties. Most were staff members at reputable teaching hospitals. But they cared for him individually. There was no practiced process. And they had never converged upon him in an integrated way before. Although the hospitals thought of themselves as being integrated caregivers, in reality they were simply collections of individual practitioners who had passed our friend from one doctor to the next.

Our coauthor, Jerry Grossman, recounted a similar experience when he visited the Mayo Clinic for a heart problem while we were writing this book. After running him through a series of tests, a team of subspecialists converged in the same room, examined the data together, and told Jerry that he had a cancerous tumor in his heart—a rare condition that ultimately took his life. Despite the bad news he had received, Jerry was absolutely bubbly about the "exquisite experience these guys took me through" in our first meeting after he returned to Boston. "They have a process!" he said. "It's not a one-size-fits-all process. Every patient has a different disease, but they have a practiced way to treat every patient uniquely." National Jewish and Mayo Clinic are coherent solution shops, as opposed to disjointed ones.

The Cleveland Clinic has recently reorganized itself into solution shops. Where most hospitals are divided into departments of medicine, surgery, pediatrics, and other general areas of practice, CEO Toby Cosgrove has directed the restructuring of the clinic into "institutes"—coherent solution shops within the hospital. Its Neurological Institute, for example, employs neurologists, oncologists, radiologists, neurosurgeons, psychiatrists, and psychologists who can converge, as appropriate, in a coordinated way to diagnose as accurately as possible the cause of behavior changes, source of epilepsy, or type of brain tumor in each patient.

There are precious few coherent solution shops like National Jewish, Mayo, and Cleveland Clinic that have reliable processes for integrating the multiple relevant disciplines required to diagnose and recommend solutions for the intuitive chronic diseases in the left side of Figure 5.1. In general, the system in which most chronically ill patients are treated is comprised of individual caregivers. Even if they work in departments and groups, most doctors practice as individuals, and patients are routed from one individual physician to the next. In most of our hospitals there are few proven, practiced pathways through which physicians knit their expertise together in a way that could surface the uniqueness of our friend's type of asthma, or Jerry's heart tumor. Many physicians we've consulted while writing this book have reflected that doctors are trained to work alone, and not together. Other observers have remarked that health care remains the last great cottage industry in America.

Isn't it too expensive, one might ask, for millions of everyday folks to fly to these coherent solution shops that are seemingly staffed by the elite for the elite? There was a time, when the basic structure of our modern health-care industry was put into place a century ago, when it probably was too expensive. But our friend's trip to Denver was actually cheap when compared to the cost to him, his insurer, and his employer of seeing doctor after doctor and taking drug after drug. The diseases on the left side of Figure 5.1 are among the most pervasive and costly conditions in America. They represent markets that would support scores of coherent solution shop clinics around the country and the rest of the world.

The need for coherent solution shops for intuitive chronic diseases constitutes an extraordinary entrepreneurial opportunity to create new business models for the diagnosis and prescription of care for patients with intuitive chronic diseases. A few studies—we expect many more to come—have demonstrated that a significant portion of the cost of chronic care is wasted, because the prescribed therapy solves the wrong problem for the wrong patient.8 The value of solving a correctly defined problem is immense, in every industry.

A core reason why more coherent solution shops for intuitive chronic diseases don't exist is that the reimbursement formulas of Medicare and private insurers make the provision of therapy much more profitable than diagnosis. Essentially, this is because these formulas are based upon activities, not the value created. As we'll see in Chapters 6, 7, and 11, one way to work around this distortion of value creation is for major integrated provider systems, which operate both insurance and care delivery organizations, to establish these coherent solution shops internally. These integrated systems have a perspective that is unique in our largely dis-integrated health-care system, because they can spend more money at one point in the value chain in order to capture greater savings elsewhere. Their insights about the economics of correct diagnosis can then inform the rest of the industry.

For many acute diseases, the job at this point would be complete: the problem diagnosed and a therapy devised and applied. But for chronic illnesses, diagnosis and prescription is only the start. Patients then need to adhere to the recommended therapy—hourly, daily, monthly, and often for the rest of their lives. Sometimes the prescription entails extensive and unpleasant behavioral changes. The business models that can profitably and effectively help patients succeed with these challenges are very different from those designed to diagnose and devise the original treatment plan. The general absence of such business models is the second major problem in the current care of chronic disease.

As above, the validity of the theory that underlies our business model recommendations is predicated on defining the categories or situations correctly. The chart in Figure 5.2 asserts that the job to be done by these business models varies along two dimensions.

The vertical axis measures the intrinsic motivation of patients to avoid the complications or symptoms of the disease by adhering to the prescribed therapy. What largely drives this motivation is the intensity and immediacy with which patients feel the complications. For example, even though wearing eyeglasses or contact lenses is a bother, nearly everyone for whom they have been prescribed wears them—because if they didn't, they instantly can't see clearly. Patients with chronic back pain religiously take their pills—because they immediately feel the consequences if they don't. At the other end of the spectrum, patients with high cholesterol feel the same on a day-to-day basis whether or not they take their medications and follow the dietary guidelines they've been given. Losing weight, foregoing unhealthy foods, and quitting tobacco are far less pleasant than the other option, which is to continue those habits for one more day. While acknowledging that many of the other patients with these diseases die of lung cancer, go blind, have their extremities amputated, and suffer kidney and heart failure, too many patients with diseases positioned near the bottom of Figure 5.2 intend to begin adhering "tomorrow," or they cling to a conviction that God will exempt them from the fate that so predictably befalls the others. All of this happens because of the deferred consequences for failing to heed therapeutic advice.

FIGURE 5.2 Factors affecting adherence to best-known therapies

Note that we've positioned asthma near the middle of this vertical spectrum. We'll highlight our reasoning for this particular placement to help explain the positioning of the others. When the complications of asthma have set in (wheezing and shortness of breath), patients are very motivated to breathe, and they badly wish they had taken the steps required in the days and hours leading up to the episode that might have prevented the attack—just like smokers who have been diagnosed with lung cancer wish they'd stopped smoking years earlier. The positioning on the vertical axis of Figure 5.2 is our assessment of patients' motivation, before the onset of complications, to take the actions that would have prevented the symptoms or complications from ever arising.

The horizontal axis of Figure 5.2 maps the second determinant of the appropriate business model: the extent to which the prescribed therapy entails behavioral change.9 At the far left are diseases where simply taking a pill is all that is required.10 Keeping at bay the symptoms and complications of diseases on the right side of the spectrum, in contrast, requires extensive behavioral change on the part of patients and their families. Methods of living with disease and adhering to the required new behaviors often need to be worked out intuitively by patients and their families.

Most of these diseases can be diagnosed by the physician, but following that diagnosis and prescription, in many instances physicians can't add much additional value beyond teaching patients broad categories of do's and don'ts. The patients and their families typically must distill from their own experiences algorithms of diet and activity that minimize the severity of their symptoms. When trained to do so, particularly when there is a closed-loop capability to feed back to patients the short-term results of their actions, patients with these behavior-intensive diseases can generally formulate better algorithms of care through trial and error than their physicians can. These rules of thumb can be learned but often are hard to teach because they vary from patient to patient.

As we've suggested in Figure 5.3, the diseases on the right side might be characterized as "behavior dependent," for which there is no simple way to ameliorate the symptoms or escape the consequences of the disease. Regular exercise, weight loss, dietary changes, and vigilant monitoring of symptoms are typical key ingredients—along with drugs in most cases—to living with the disease and avoiding complications. And we'll call those on the left side of Figure 5.3 "technology-dependent chronic diseases." Now let's slice the matrix horizontally. We call the diseases at the top those with Immediate Consequences. We can count on patients with these diseases to search for some combination of behaviors and medications that work and then to dutifully adhere to that regimen, because the immediate and unpleasant consequences of not doing so provide ample motivation to follow the rules. We term the diseases at the bottom as those with Deferred Consequences. Some patients with these diseases have a long enough view that spurs them to take the medication and adopt the prescribed behaviors—but many do not. Many of these patients agree with their caregivers' recommendations, and fully intend to adhere to them—starting tomorrow.

FIGURE 5.3 Chronic quadrangle: behavior-intensive diseases with deferred consequences

The crushing costs of caring for chronically ill patients are largely attributable to diseases in the lower-right box in Figure 5.3. Obesity, tobacco and alcohol addictions, diabetes, asthma, and congestive heart failure are behavior-dependent diseases with deferred consequences affecting tens of millions of people each. We'll term this box the "Chronic Quadrangle."

Before we discuss the business models required to promote adherence to therapy in the four sections of Figure 5.3, we'd like to discuss the impact of technological progress on chronic diseases—because in many ways it is both the cause of chronic disease and the cure. The position of the chronic conditions in the figures above is our estimate of where they are today. But many of them are on the move. Historically, many of these were once acute diseases, in that patients often died from them within short time frames. Others were debilitating, lifelong diseases, and technological progress made it possible for patients to live more normal lives. Continued technological progress can transform intuitive chronic diseases from the left side of Figure 5.1 into diseases that are rules-based and require only a straightforward intervention.

Ultimately, scientific progress can transform chronic diseases into "acute" ones again—diseases that can be cured, and sometimes even prevented. The care of most stomach ulcers has undergone this transformation. A century ago severe stomach ulcers often resulted in bleeding and death. Living with ulcers required extensive behavioral and dietary modifications. Believing that the cause of most ulcers was excess production of stomach acid, providers offered medications like Tagamet to block the production of acid. Patients who avoided stress, shunned spicy foods, and faithfully took their medications then could live with this disease reasonably well.

In 1982, however, Dr. Robert Warren, an Australian pathologist who knew little about clinical gastroenterology, identified a strain of bacteria called Helicobacter pylori living in ulcerated human stomach tissue. This was a shocking discovery, because scientists previously had been convinced that such bacteria could not survive the hydrochloric acidity of the stomach. Warren asserted it was infection by this bacterium that was the genesis of most ulcers, meaning they could be cured with antibiotics. In a test reminiscent of Walter Reed's team allowing mosquitoes to bite them in order to prove that Yellow Fever was a mosquito-borne virus,11 Warren's colleague Barry Marshall swallowed a cocktail containing the H. pylori bacterium. Within a few weeks he was diagnosed with stomach ulcers; and following a course of antibiotics, he was cured.12 Subsequent research has revealed that this bacterium causes 90 percent of intestinal ulcers and 80 percent of stomach ulcers—and for most patients, what once was a chronic disease is now managed as an acute disease that can be cured. In a similar vein, technological progress seems to be shifting the position of Crohn's disease on the map of Figure 5.3. What are typically thought of as two different chronic diseases—multiple sclerosis and Crohn's disease—are actually different symptomatic manifestations that share a common cause: destructive inflammation caused by the influx of white blood cells. The drug Tysabri, which addresses the underlying inflammation by blocking signals to white blood cells, seems to ameliorate the symptoms of both "diseases." This holds the ultimate promise of shifting Crohn's to the left side of the map, where therapy is less behavior-intensive.13 Indeed, "statin" drugs such as Lipitor have already moved the management of high cholesterol from the lower right to the lower left of Figure 5.3.14

Massive resources were mobilized in a relatively short period of time to transform AIDS—which is a significant disease in the United States and Europe but is a horrific epidemic in Africa—from being an acute to a chronic disease. Efforts continue in order to transform it further into an acute disease again—one that can be cured.15

There is some possibility that addictions to alcohol and tobacco can be shifted toward the lower left as well, as drugs are emerging that make the treatment of these diseases less behavior-intensive. There is even hope that some forms of obesity and diabetes likewise can be shifted toward the bottom-left of the map and ultimately transformed into curable diseases, as the different underlying disorders that manifest themselves through the symptoms of obesity and elevated blood glucose become better understood.16

What we've asserted to this point is that the care of chronic disease needs to be divided into two different "businesses." The first is a business of diagnosis and prescription, the second is a type of business that can help patients adhere to the prescribed therapy. And there's a handoff between the two that needs to be managed as well, as we'll discuss below. The business models we've historically relied upon to do this job weren't designed to do it—and that's why the diseases in the Chronic Quadrangle are causing such costly complications.

The resources, processes, and profit formulas of doctors' offices and hospitals are optimized to manage acute crises or episodes, yet our health-care system has expected professionals working in these businesses also to be the caregivers during the adherence stage for nearly all chronic diseases. Doctors can be paid for diagnosing the chronic disease, evaluate its progression, and remediating the complications (when possible). But most health plans are really sickness plans, in that they will not pay for the cost that a doctor's office or hospital might incur to call patients between scheduled visits to monitor and encourage their adherence to the prescribed therapy. Insurance, for example, will pay for the amputation of a limb to treat diabetes-related gangrene, but not for the conscientious follow-through that can lessen the probability of needing such costly and tragic remediation. This is not the fault of physicians or insurers. The fault is in the misapplication of a business model that was designed for the practice of acute medicine long ago. As they are now organized, there simply is no way physicians' practices and hospitals can afford to help chronically ill patients during the period of adherence.

Consider the economics of caring for patients with asthma, one of the costliest chronic diseases, as summarized by George Halvorson, chairman and CEO of Kaiser Foundation Health Plan and Hospitals:

Run the numbers and look at the contrasts. Patients might pay a doctor $100 for an asthma prevention visit and another $200 for their inhaler prescription. An E.R. visit, on the other hand, can generate $2,000 to $4,000 in provider revenue, and a full-boat hospitalization could generate $10,000 to $40,000 in caregiver revenue. If money incents behavior, where are we as a society putting our money today? It's not in preventing asthma attacks—even though America is in an asthma epidemic.17

We need disease-appropriate business models to treat patients in the four situations depicted in Figure 5.3. The upper-left quadrant, comprised of technology-dependent diseases for which nonadherence to therapy has immediate consequences, has an easy answer. After diagnosis and prescription, doctors can be confident that patients will take their medication.18 They simply must schedule periodic follow-up examinations to monitor patients' progress. They can get paid for this, as it fits the structure of a physician's practice, and they can do this job well. It is the patients in the other three quadrants who need new business models.

A primary vehicle for care of patients with behavior-dependent diseases such as those on the right side of Figure 5.3 must be a facilitated network business model. As we described in Chapter 1, the essence of a facilitated network is that its participants exchange information or things with each other. Sometimes those things are bought and sold, as occurs in the networks facilitated by eBay and craigslist. In other instances, user-generated content is the material of exchange, as in YouTube's network. As a general rule, the companies that facilitate the networks make the money in this business model, while the users of these networks typically participate for other reasons.

Employing facilitated network business models to cost-effectively address behavior-dependent chronic diseases is not a new insight. Alcoholics Anonymous, for example, is a patient network within which the participants essentially exchange user-generated content. They teach each other how to overcome the disease of alcoholism, and they provide support for each other while doing so. Although most physicians have treated patients with acute symptoms of alcohol withdrawal, alcoholic liver disease, or alcohol poisoning, those same physicians often have little to add in the treatment of the underlying chronic disease. Another example is the host of weight loss networks. Though only modestly successful,19 they are nonetheless focused on the challenge of bringing together people with the chronic disease of obesity and facilitating their interaction.

Many facilitated networks are organized by not-for-profit associations comprised of patients and their families, offering in-person and online support groups in which patients can help each other deal with the disease and find the best possible treatments. One example is the Web site dLife, a network of people with diabetes and their families. Through a weekly CNBC television program and an easy-to-navigate Web site, dLife enables community members to teach each other the "tricks of the trade"—helping and inspiring each other to do better.20—The Restless Legs Syndrome (RLS) Foundation, as another example, exists to help patients "learn about the latest treatments, and to arm themselves with information to educate health care providers about RLS."21 Funny, there was a time when the providers educated the patients! These networks are stepping into the breach where solution shops and value-adding process business models just can't viably provide care.22

We can expect patients in the upper-right quadrant—those who have behavior-dependent diseases with immediate consequences to nonadherence—to participate in these facilitated networks at their own volition. They are motivated to figure out better ways to live with their diseases. Not long ago, patients and their families networked as best they could, relying on doctors, friends, and family to introduce them to others with the same disease. Today, the Internet makes it much easier for patients with these diseases to find and connect with others in similar situations. Doctors still need to follow through periodically with these patients, of course, but until technological progress shifts the location of these diseases toward the left and bottom of the matrix, the objective should be to give patients the tools to care for themselves. Herodotus, the Greek historian who wrote The History of the Persian Wars in the fifth century BC (ca. 484 BC to 425 BC), observed what appears to have been a precursor to these sorts of networks during his travels through Babylonia:

The following custom seems to me the wisest of their institutions . . . They have no physicians, but when a man is ill, they lay him in the public square, and the passersby come up to him, and if they have ever had his disease themselves or have known anyone who has suffered from it, they give him advice, recommending him to do whatever they found good in their own case, or in the case known to them; and no one is allowed to pass the sick man in silence without asking him what his ailment is.23

Care for chronically ill patients in the two bottom quadrants of Figure 5.3 needs to be overseen by entities that can profit from their patients' wellness, rather than profit from their sickness. This basically rules out all providers who work on a fee-for-service basis, because, as we noted earlier, there are no billing codes for wellness.

The entities that can profit by keeping patients well are those that provide all of the health care their members need, in exchange for a fixed annual fee. This insurance mechanism has acquired the unfortunate rubric of "capitation," because caregivers charge a fixed per capita annual fee. Capitation hasn't worked well in the nonintegrated health systems that provide care to 95 percent of all Americans,24 because, as we'll discuss in greater detail in Chapter 7, it pits independent caregivers into a zero-sum, I-win-only-if-you-lose game. These independent providers aren't able to take a systemwide perspective on cost effectiveness. Capitation only can work in an integrated system where the insurer is also the provider.

There are two types of caregiving entities in which this insurance mechanism of capitation works. The first, which we'll call a "disease management network," is typified by Nashville, Tennessee–based Healthways, Inc., and by OptumHealth, a unit of UnitedHealth Group. Healthways and Optum take responsibility for the health of a "population" of patients with chronic diseases such as asthma, diabetes, obesity, and congestive heart failure.

Healthways employs nurse practitioners, who connect with each patient by phone at least weekly. The nurses collect data from the patients in order to monitor their progress in following the prescribed therapy. They teach patients how to care for and monitor themselves, and they work to tailor the therapy to each patient's situation. The data and details of each interaction are noted in Healthways' patient record system, so that the next week another nurse practitioner, if necessary, can call and interact with the patient and be fully informed, as if she had always been the one on the other end of the line. Major self-insured employers such as General Electric, Hewlett Packard, Caterpillar, and Federal Express have been primary drivers of the growth of disease management networks. They pay the network a fixed annual fee for the care of all of their patients who have certain costly, chronic diseases. To the extent that its oversight improves patients' health by helping and motivating them to adhere to their prescribed therapies, Healthways makes money. The company claims that its costs are significantly lower, and the outcomes much better, than for patients who are cared for in a fee-for-service world where money cannot be made by keeping people well. Healthways has been growing at 35 percent annually and now collects nearly $750 million in revenues, while covering 28.9 million lives.25

The other caregivers that can profit from patient wellness are integrated fixed-fee providers like Kaiser Permanente and Gei-singer Health System. Providers like these own their own hospitals and clinics, employ their own doctors, and operate their own insurance companies.26 Kaiser, for example, charges its members a fixed up-front monthly or annual fee for all of the care they might need—so it profits by keeping its members well. These integrated providers also profit by retaining members within their systems, which gives them the incentive to save costs by keeping their members well and satisfied with their care, not by restricting their access to care. Incidentally, Kaiser members are far less likely to switch plans than members of other health plans.27

In order for this business model to work effectively in keeping chronically ill patients free from the complications of their diseases, patients must be able to self-monitor (and often self-treat) their diseases using technological enablers. The potential for doing this is probably best developed for Type I diabetes care. Well-informed, proactive patients carry pocket-size blood glucose meters wherever they go; inject their own insulin, while adjusting the dose according to their recent glucose measurements; control the size and timing of their meals; and track their level of physical activity. All this monitoring and self-care allows them to develop individualized algorithms for controlling the levels of glucose in their blood. The interactions among diet, activity, and medication with patients' unique physical characteristics are not nearly understood well enough for physicians to articulate a rules-based regimen that will work for each individual patient—instead, the patients work it out for themselves.

Hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and congestive heart failure are other diseases in which affordable, convenient measurement equipment can be designed and made so patients can become their own primary caregivers, assisted and overseen by professionals in the disease management network business models described earlier.

We sense that the problem of adherence to prescribed therapy for disorders with deferred consequences will be mitigated, though not completely resolved, by putting care in the hands of providers whose economic model profits from wellness. The patients themselves need to be able to profit from wellness as well.

Nearly all health-care decisions that affect chronically ill patients are made by the patients themselves—out of the eyesight and earshot of their doctors. For example, doctors spend about two hours each year with their diabetic patients, but the patients spend 8,758 hours managing the disease on their own.28 Even for those technology-dependent diseases in the lower left of Figure 5.2, the decision to take or not take prescribed medication is made by the patient. After all the caregivers can do, the efficacy of therapies for chronic diseases and the costliness of the complications from these diseases depends, in the end, on patients' motivation to adhere to courses of therapy that will prevent or delay the complications stemming from the disease.

For each of the major public health concerns in the Chronic Quadrangle at the lower right of Figure 5.3, we often know what needs to be done to reduce the cost and improve the care of patients with these diseases. Quit smoking. Lose weight. Maintain levels of blood glucose between 90 and 130 mg/dl. Keep LDL ("bad") cholesterol at or below 100 mg/dl. Use your steroid inhaler for asthma even on days when your breathing seems normal.29 The question is: how can we help these patients become motivated to do what they know they should do?

Our research on the value of understanding the job that customers are trying to do, which we introduced in the discussion of business models in Chapter 1, offers some clues. To predict what actions people will prioritize, we need to watch what they do, because we are often misled when we listen to what they say.

Recall, for illustration, what life was like before digital photography. We took our roll of film to a store to be developed. Most of us chose to get double prints because the second one was almost free, and in case one of the prints turned out to be especially good, we wanted to be able to send that extra one to Grandma. When you picked the prints up, what did you do with them? You flipped through them and then put them back in the envelope, which you then put in a box or drawer. Ninety-eight percent of all photos that were taken have only ever been looked at once. Only the most conscientious people took the trouble to mount the most memorable photos in an album to look at again. The rest of us knew that we should, but we just didn't— or we planned to start tomorrow. Market researchers learned from speaking with consumers that many of them wanted to start keeping photo albums. But if you watched what people did, it was very different than what they said they wanted to do.

When digital cameras emerged to disrupt film photography, companies offered several value propositions to camera users, based on this market research. One was, "You can click 'attach' and e-mail photos to friends and family whenever something interesting or important happens!" Another was: "If you'll just take the time to learn how to upload these photos, you can edit the red eye out of all those pictures that you used to look at only once!" A third proposition was: "You can keep all those images in this online scrapbook that makes it easy to sort, search, and print from your gallery of thousands of photos!"

If you watch what most digital camera users actually do, very few of them have learned to use photo editing software; and even fewer keep online photo albums. Why? These just weren't things that had been priorities in their lives before the new technology arrived. The feature that most digital camera users actually use is the facility for e-mailing images to family and friends. Why? Because that is the same job we were trying to do when we ordered double prints. An innovation that makes it easier and cheaper for people to do what they're already trying to do is called a "killer app."30 An innovation that makes it easier and cheaper for people to do what they're not trying to do, in contrast, faces a struggle for success akin to an uphill death march through knee-deep mud—and then it typically fails.

People who don't want to do something that they know they should do have marvelously inventive abilities to ignore what they know. They resolve to start tomorrow, or conclude that it's okay if they just don't do it. We rationalize the rules to comply with our desired behavior. Marketers in every industry confront this reality: consumers demonstrate daily the propensity to prioritize what they want to accomplish, not what they are told they should accomplish. College students should be motivated to expand their learning by delving into the online expansions of their textbooks. Drivers should obey speed limits, for their own good. But they don't. It's human behavior, not the behavior of diabetics, smokers, and the obese, that we're dealing with. Most of us are frightfully guilty of believing we don't need to follow certain rules that are demonstrably important for everyone else to follow.

One of the reasons why the jobs-to-be-done concept is proving so powerful in directing successful innovation within so many companies is that it gets directly at the cause of action. The fact that someone is in a particular demographic segment is often correlated with a propensity to buy certain products and not others, but what causes the purchase is that the customer has a job that needs to be done. Similarly, the fact that someone has Type II diabetes and is overweight might be correlated with tendencies to adhere or not adhere to recommended therapies. But what causes adherence is the need to do a job.

So what is the job that most noncompliant patients who suffer from obesity, Type II diabetes, heart disease, and tobacco addiction are really trying to do? They just don't want to have the disease. "I feel fine today and I'll feel fine tomorrow, so I just don't want to think about it." Maintaining health is a job that only a minority of people prioritize in their lives. For the rest, becoming healthy only becomes a priority job after they become sick. This is a key observation. In some ways it is tautological. Most patients for whom the "I want to become and remain healthy" job is important have kept themselves out of these chronic diseases. Or if they got the disease, they quit smoking, lost weight, and got the requisite cardiovascular exercise. Even when the genetic endowment of some of these patients makes it impossible to lose the weight that might put Type II diabetes into remission, for example, the patients who have the "become and remain healthy" job assiduously monitor and control their blood glucose so that complications don't happen.

It turns out that for most people who have chronic diseases with deferred consequences, "improve my financial health" is a much more pervasively experienced job than "maintain my physical health."

An executive of one of America's largest companies reflected with us a short time ago about her frustrations in reigning in her company's health-care costs. "We set up several different wellness programs offering fitness club memberships to our employees at a 50 percent discount to give them an incentive to lose weight and become and remain fit. A couple of years into the program, we looked at which employees were using the benefit. Less than 15 percent of the total had enrolled, and almost all of these were people who already were in good physical condition. Few of those we had targeted—those with or at risk of developing diabetes and heart disease—took advantage of the benefit."

This company offered a 401(k) retirement plan as another benefit. The company matched employees' contributions to their 401(k) account dollar-for-dollar. We asked this executive what portion of her employees were enrolled in and actively contributing to their 401(k) savings plans. "Over 70 percent," was her reply. "It sure seems like people care a lot more about their financial health than their physical health."

This executive's observations are typical. Many of those with or at risk of developing obesity, Type II diabetes, tobacco addiction, and heart disease are actively working to assure their long-range financial prosperity. Seventy-two percent of Americans contribute to a 401(k) account.31 A large and growing number of people monitor and proactively manage their FICO,32 or credit scores. They pay their bills on time, constrain their debts, and manage the other variables in the equation that determines this score, in order to preserve the option of borrowing affordably in the future.

An important implication of this behavior is that for diseases with deferred consequences, a system that makes adherence to therapies a vehicle for getting the "financial health" job done will be more successful in reducing the costs and tragic complications of these diseases than traditional "wellness" programs. Systems such as health savings accounts (HSAs) make the pursuit of health a mechanism for accomplishing the pursuit of wealth.33

The present systems of Medicare and employer-paid health care actually decouple patients' health from the job of ensuring long-range financial prosperity. For example, patients with diabetes are supposed to test their blood glucose regularly. At a price of over a dollar for each test strip, this self-monitoring can cost up to $1,500 per year. It actually costs less than ten cents apiece to make these strips.34 The major retailers of diabetes supplies such as CVS, Wal-Mart, and Liberty years ago began selling their own brand of glucose meters, with test strips priced at less than half those of name-brand strips.35 But the store-brand tests have gained only modest traction in the market because patients covered by conventional reimbursement plans experience little cost difference.

Currently, when patients fail to adhere to prescribed therapy for diseases in the Chronic Quadrangle of Figure 5.3, there are no immediate consequences for physical or financial health. In the short term, nonadherence in this category has little effect on physical well-being, nor does the rigor by which patients strive to cure themselves or manage their diseases more cost-effectively impact their short-term trajectory of asset accumulation. And the long-term trajectory isn't affected either, because insurance and Medicare will step in to cover the very high costs of complications that result from nonadherence.

At present, a range of regulations forbid employers or insurers from differentially pricing the cost of health coverage for those employees who, because of genetic predisposition or behavioral choices, have these diseases and are not complying with prescribed therapy. Interestingly, we allow life insurers to price differently, based upon risks associated with various diseases their customers have. Disability insurance can also be differentially priced. We price loans differently, as well, based upon customers' financial behaviors, fortunes, and misfortunes. As we'll describe in Chapter 11, we need to change these regulations so that improving adherence improves financial health, not just physical health.36

Here's one possible mechanism for doing this: just as several companies are constantly keeping our credit scores up to date by collecting data on all of our debts and the extent to which we pay our bills on time, other companies, like Ingenix, have been calculating a health score for each of us.37 They reach into the databases of pharmacy benefit managers and compile a complete record of all the prescriptions each of us gets filled. They therefore have a very good sense about most of the acute and chronic diseases we've had, and, using those profiles, they've developed algorithms to predict the costs of insuring each of us and our families in the future.

Until now, Ingenix has only made our health scores available to insurers like Blue Cross/Blue Shield, which then use those scores to price the health insurance policies they sell to employers. It would be a small step for Ingenix to begin sending each of us our updated health score every six months. They could send this score through the same firm, such as Fidelity, that is already handling our 401(k) and health savings accounts. Such a statement could include predictions of what our HSA account balances will be in the future if we maintain our current health scores and if we and our employers continue to contribute to our HSAs at historical rates. The statement could also estimate for us how the projected balance in our HSAs could be increased if we improved our health scores—and it could show us which behaviors and components of our health scores will have the greatest leverage.

Each employee HSA will have an insurance policy against catastrophic illness packaged with it.38 Because health scores are used today to calculate the costs of reimbursement and insurance coverage for each of us, a system such as this would simply make the calculations explicit. If a person's health score is low enough so the projected future cost of catastrophic insurance will increase, the employer's contribution to the employee's HSA might drop and be diverted to pay for insuring against the increased cost of long-term complications.

A system such as this—one that aligns physical health with financial health—is essential to developing viable business models to care for the chronically ill. In the past, some have objected to such propositions on fairness grounds. The argument essentially is that because to some degree our health might be determined by things beyond our control, those who became sick through no fault of their own should not have to pay a higher price for their health coverage. We would argue in return that with literally every other type of insurance—life, disability, home, and auto—society already has agreed that people can and should pay different rates based upon their experience—whether it was their fault or that of others. We predict that despite all of the predictable, self-protecting rhetoric around this issue, people will actually adjust to this policy quite readily.

A key tenet of this chapter is that the business of diagnosing the disease and recommending a therapy is very different than the business of assuring day-to-day adherence to the behavior and medications that were prescribed. Because the business models are so different, different caregivers must provide each piece of the complete package of care for chronic disease—which means there is a big handoff between the two. Some entity needs to be sure that patients don't fall through this crack.

Though we treat this topic more thoroughly in the next chapter, we'll note here that employers are critical players to enroll in the fight against chronic disease, and need to play an active role to ensure that their employees don't fall into the chasm between these providers. A critical job that employers always need to do is attract and retain the best possible employees, and make those employees as productive as possible.

When you listen to what employers say, most sound eager to get out of the business of funding health care for employees and their families. But if you watch what employers do, they spend thousands of dollars per employee every year, and invest an extraordinary amount of managerial attention to attract, train, improve, and retain their employees. We expect, as a result, that employers will take an increasingly active role in managing the quality and cost of employee health care—especially chronic diseases—because they profit from productive employees. In the past, because they haven't known what else to do, many employers have simply been shifting costs to their employees. We hope to show through this book that health-care cost isn't a variable determined exogenously to our system. It is caused by our system; and as the next chapter shows, proactive executives can profoundly influence those costs and service quality.

We hope that the sections above have laid bare the basic parameters for how care for chronic disease must change. Diagnosing these diseases and defining the most effective therapy possible is a very different business than ensuring day-to-day adherence to the recommended course of action. The same chronically ill patient needs to be served by two fundamentally different business models.

A significant portion of the cost of caring for chronic disease arises because the patients have been misdiagnosed and treated with medications that are not effective for them. Although some of these misdiagnoses can be traced to actual medical error, for many others the culprit is business model error. Because so many of these diseases arise at a multiavenue intersection of several different systems of the body in the realm of intuitive medicine, a single specialist often will not have the perspective required to get the right answer. Simply passing the patient off to another subspecialist with a comparably specialized perspective doesn't solve the problem of interdependencies. It's not the doctors' fault. It's the fault of the business models in which they've been asked to work. Many more need to do what a few of our leading medical centers already have done: create coherent (as opposed to disjointed) solution shops whose job is to diagnose and devise effective therapy for patients with intuitive chronic diseases.

Patients whose therapy is behavior-dependent need help to figure out what to do and how to do it. From at least as early as Herodotus, to Alcoholics Anonymous in our day, network business models have a proven track record as the best of the three types in getting this job done. The Internet makes it infinitely easier for patients with these diseases to find "some- one like me," who can inspire and coach others from personal experience.

In the past, the physicians' practices that by default were the ones we've counted on to police adherence to prescribed therapy weren't motivated to do it, because they simply couldn't make money doing it—and professionals cannot survive doing what they don't get paid to do. We know of two business models that can make money by keeping patients healthy: disease management companies like OptumHealth and Healthways, and integrated fixed-fee provider companies like Kaiser Permanente and Geisinger.

The fact that these (and the few others like them) care for only a fraction of patients with diseases whose consequences are deferred means there is an extraordinary opportunity for employers and insurers to guide more of their employees and members who need this type of oversight into the reach of the businesses that can provide it. And the fact that many of those with behavior-dependent diseases, whose consequences are deferred, care more about financial than physical health, merits addressing, not denial, by those who would do good among the massive population of patients with these diseases.

1. While some who study these problems make a distinction between chronic diseases and chronic conditions, for purposes of brevity we'll refer to both conditions and diseases as diseases.

2. Halvorson, George, Health Care Reform Now! A Prescription for Change (San Francisco: Jossey Bass, 2007), 4.

3. This means, of course, that the aging populations in most economically developed countries will cause health-care costs to balloon even more in the future.

4. Indeed, while much of modern health care is lifesaving and life-prolonging, it often is not yet a complete cure—making lifelong treatment necessary. But the technological progress that makes this possible, which is so welcome in the developed world, creates huge new problems in impoverished nations. There, the technologies that transform acute, fatal diseases into chronic ones, while welcome at the personal level, can spell financial disaster to government health ministries that simply do not have the resources to prolong the lives of so many more sick people.

5. See Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, "HCPCS Release and Code Sets Overview;" American Medical Association, "CPT (Current Procedural Terminology);" and "Relative Value Units and Related Information Used for Medicare Billing," Federal Register, Nov. 15, 2004.

6. See Christensen, Clayton, and Paul Carlile, "The Cycles of Theory Building in Management Research," Harvard Business School Working Paper Series, no. 05-057, 2005.

7. Some diseases, like depression and schizophrenia, have lagged behind most other chronic diseases in research funding, for example, and in many aspects are still poorly understood. Other conditions, like chronic back pain and dementia, remain quite imprecisely defined with fuzzy diagnostic criteria, and therefore demand a more intuitive approach than a simple chronic disease like myopia (nearsightedness). Other diseases, like prostate cancer, may be simpler to diagnose, but involve competing treatment options. Finally, some diseases, like lupus, are inherently complex because they can affect multiple organ systems at different times.

8. The Institute of Medicine estimated that $17 to $29 billion annually is spent unnecessarily, and between 44,000 and 90,000 people are killed each year as a result of misdiagnosis and preventable medical errors. These figures include diagnostic errors for acute care as well, but do not include the substantial malpractice costs involved in many cases.

9. The extent of behavioral change required, and the degree to which the intuition of patients and family members needs to guide those behavioral changes, in theory are two different variables. We feel that the correlation of the two constructs is close enough that, for simplicity, we've chosen to map them on the same axis, as if they were one variable constructed from two highly correlated ones.

10. Interventions can also include surgical procedures and devices, probably the best examples of "set it and forget it" treatments for chronic disease. However, the scope of these interventions has been limited primarily to conditions rooted in anatomical and mechanical defects. In addition, there are other chronic diseases for which treatment options are extremely limited and behavior changes have little impact, such as Huntington's disease or Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (Lou Gehrig's disease). Our discussion in this chapter will focus on the management of chronic diseases through medications.

11. A Cuban doctor, Juan Carlos Finlay, seems to have been the first to assert that mosquitoes were the perpetrators of yellow fever. To test this idea, several members of Walter Reed's team, based near Havana, allowed themselves to be bitten—and one of Reed's top deputies, Jesse W. Lazear, actually fell sick and died. Further research convinced Reed that the disease was spread by mosquitoes sucking the blood of people victimized by yellow fever and then biting others. These brave volunteers were essential to Reed's work. Major Reed took what was then the unusual step of securing each man's informed consent—the volunteers understood that by participating in his research they risked contracting yellow fever. To advance science, they flirted with death. Mortality rates fluctuated from outbreak to outbreak, but generally about 20 percent of those who contracted yellow fever could expect to die from it. The volunteers' courage is perhaps best embodied in the words of Private William Dean of Lucas, Ohio, who insisted that he wasn't "afraid of any little old gnat." Dean became the first man to let an infected mosquito bite him. He developed yellow fever and recovered.

12. Dr. Warren and his colleague Dr. Barry Marshall were awarded a Nobel Prize in 2005 for this discovery. As an aside, their initial announcement was greeted with disdain by the world community of gastrointestinal specialists. Thomas Kuhn chronicled in his 1962 classic, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, 1st ed. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press) that the insights that lead to the toppling of incorrect or incomplete scientific paradigms rarely come from within the discipline of most experts in the reigning theory. Almost always, insights leading to the breakthrough come from an outsider, because typically you need to view an old problem from a new angle in order to see different things. In the case of ulcers, it took well over a decade after Warren and Marshall's discovery before the mainstream gastrointestinal community accepted these findings and began treating ulcers with antibiotics. In terms of our model in Chapter 1, the diagnosis and treatment of duodenal and gastric ulcers has advanced significantly along the spectrum from intuitive to precision medicine. We will return to Kuhn's insights about scientific research in Chapter 11.

13. Because these diseases are defined historically by symptom rather than cause, Tysabri (developed at Elan Pharmaceuticals and marketed in the United States by Biogen-Idec) was tested in clinical trials and approved initially as a multiple sclerosis drug. FDA rules required an entirely new set of trials for Tysabri to be approved for on-label treatment of Crohn's. See Honey, K., "The Comeback Kid: TYSABRI Now FDA Approved for Crohn disease," Journal of Clinical Investigation, March 2008; 118(3):825–26. With continued scientific progress, we can expect that not all patients diagnosed with multiple sclerosis and Crohn's will respond to Tysabri, and that still more precise diagnostics will need to emerge.

14. In many ways, cholesterol-lowering drugs are a disruptive innovation relative to angioplasty, just as angioplasty was a disruptive innovation relative to open heart surgery.

15. One reason so much progress was made so rapidly in AIDS is that it was quickly found to be an infectious disease. A history of successful innovations in the world of infectious diseases has given us processes, paradigms, and an entire infrastructure that could be leveraged in the AIDS effort. A key reason why AIDS and malaria—another horrific disease—have defied curative solutions is that the organisms that cause the diseases mutate and evolve faster than science can keep up with them. If history is any guide (as was the case with ulcers), it is quite likely that the resolution to these problems will come from outside the discipline of infectious diseases and immunology.

16. Indeed, some would argue that bariatric surgery has the potential to transform some diseases that we now lump under the rubric of obesity and diabetes into a disorder whose primary symptom can be made to disappear.

17. Halvorson, George, Health Care Reform Now! A Prescription for Change (San Francisco: Jossey Bass, 2007), 109.

18. Of course, there are still socioeconomic and educational barriers that can impede therapy, in which case facilitated networks can play a more important role. We will again address some of these barriers that disproportionately affect the uninsured poor in our chapters on reimbursement and regulation.

19. Dansinger, Michael L., et al., "Comparison of the Atkins, Ornish, Weight Watchers, and Zone Diets for Weight Loss and Heart Disease Risk Reduction," Journal of the American Medical Association, 2005; 293:43–53. Although overall patient adherence rates to dietary recommendations were low, each diet program in the study demonstrated modest reductions in body weight and cardiac risk factors after one year.

20. O'Meara, Sean, "Diabetes Education Goes Multimedia," Nurses World, April/May 2007. Newsletters, recipes, forums, a national weekly television show and radio station, and online educator-customized interactive tools for providers and patients can be accessed at http://www.dlife.com.

21. Quote taken from the Restless Legs Syndrome Foundation home page, accessed at http://www.rls.org on March 24, 2008.

22. To be sure, not all of these emerging networks are created equal. Whether their recommendations are in the tradition of mainstream medical science or rooted in alternative medicine, some of these Web sites advocate solutions that have no grounding in well-designed research. In every industry at the outset, great value is created by entrepreneurs who create a "portal," with an assurance that once you walk through that portal, what you find inside will be of a quality that you can trust. For example, Sears, Roebuck and Company did this for mass-produced goods as those products first emerged. There were few product brands that people knew and could trust, but you knew if it passed muster in the Sears purchasing process, it had to be good: Sears guaranteed it. For this reason, we would expect that "portals" such as WebMD will play critical roles in validating the trustworthiness of these networks. Over time, some of the Web sites and networks will develop adequate brand reputations of their own so that they can stand alone.

23. Herodotus, The Histories (c.430 BC), I:197.

24. Estimate from Lawrence, David, "Gatekeeping Reconsidered," New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 345 (18):1342–43.

25. This information comes from Clayton Christensen's personal interviews with company executives, as well as Healthways Investor Presentation, June 19, 2008, accessed at http://media.corporate-ir.net/media_files/irol/91/91592/HWAYInvestor_Presentation_06_19_08(1).pdf.

26. There can be multiple entities involved due to regulations. For example, Kaiser Permanente is actually comprised of several organizations, including Kaiser Foundation Health Plan, Kaiser Foundation Hospitals, and a for-profit Medical Group—however, they are tightly aligned and cooperate within a "closed network."

27. See Rainwater, J; P. S. Romano; and J. S. Garcia, "Switching Health Plans and the Role of Perceived Quality of Care, Abstr AcademyHealth Meet., 2005; 22: abstract no. 4232. The switching rate of Kaiser members was 1.0 percent, versus 11.1 percent for members of other HMOs.

28. Demchak, Cyanne, "Choice in Medical Care: When Should the Consumer Decide?" AcademyHealth issue brief, October 2007. Accessed at http://www.academyhealth.org/issues/ConsumerDecide.pdf.

29. These recommendations can differ, of course, depending on the chronic disease involved and its severity.

30. Killer App is a term popularized by Downes, Larry, and Chunka Mui, Unleashing the Killer App (Boston, Massachusetts: Harvard Business School Press, 2000).

31. See "American Express National Survey Finds Multiple and Duplicate Retirement Accounts Pervasive; Benefits of Consolidation, Real Diversification Not Understood by Most Americans," Business Wire, Feb. 9, 2004.

32. FICO is a credit score calculated according to a formula devised by Fair Isaac Corporation.

33. Covel, Simona, "High Deductible Policies Offer Savings to Firm and Its Workers," Wall Street Journal, April 9, 2007, B4.

34. "Test Strip Reveals a Big Profit Motive," Los Angeles Times, November 7, 2007.

35. Mendosa, Rick, "Stripping Down the Cost of Testing," DiabetesHealth, June 1, 2004.

36. As we'll discuss in Chapters 6 and 7, some creative employers and insurers have started to employ this concept already, often testing the legal system in the process. In September 2008 the state of Alabama announced that it would begin charging additional premiums to employees who failed to undergo screenings for health risk factors and, for those found to be at higher risk, failed to see a doctor free of charge to discuss those risk factors. See http://www.cnn.com/2008/HEALTH/diet.fitness/09/19/alabama.obesity.insurance/index.html.

37. Ingenix is a unit of UnitedHealth Group.

38. As we will discuss in Chapter 7, HSAs are required by law to be paired with high-deductible, catastrophic insurance.