In the 15 years since we first introduced the term "disruptive technology" into the lexicon of business management, there has probably been as much confusion about it as there has been clarity because the terms "disruption" and "technology" carry many prior connotations in the English language. Disruption connotes something "upsetting" and "radically different," among other things. And to many, "technology" connotes revolutionary ways of doing things that are comprehensible only to Ph.D. scientists and computer nerds. As a result of these other connotations of the words we chose, many who have only casually read our research have assumed that the concept of disruptive innovation refers to a radically new technology that tips an industry upside down.

But we have tried to give the term a very specific meaning: "disruption" is an innovation that makes things simpler and more affordable, and "technology" is a way of combining inputs of materials, components, information, labor, and energy into outputs of greater value. Hence, every company—from Intel to Wal-Mart—employs technology as it seeks to deliver value to its customers. Some executives believe that technology can solve the challenges of growth and cost that confront their firms or industries. Yet this is rarely the case. Indeed, widely heralded technologies often fall short of the expectation that they will transform an industry. Anyone who has been inside a modern hospital, for example, has noted the myriad sophisticated technologies at work today, yet health care only seems to get more expensive and inaccessible. The reason is that the purpose of most technologies—even radical breakthroughs—is to sustain the functioning of the current system. Only disruptive innovations have the potential to make health care affordable and accessible.

In this chapter we first review the concept of disruptive innovation and its constituent elements. We then zero in on the concept of a business model, showing that it is composed of four elements—a value proposition, and the resources, processes and profit formula required to deliver that value proposition to targeted customers. Because business model innovation is the crucial ingredient in harnessing a disruptive technology in order to transform an industry, we then describe three different classes of business models around which the health-care industry will be organized in the future. Along the way, we offer illustrations from other industries showing that when innovators stop short of business model innovation, hoping that a new technology will achieve transformative results without a corresponding disruptive business model and without embedding it in a new disruptive value network or ecosystem, fundamental change rarely occurs. In other words, disruptive technologies and business model innovations are both necessary conditions for disruption of an industry to occur. We close the chapter by explaining the process by which existing companies and their leaders can create new business models that match the degree of disruption needed.

In the subsequent five chapters we will build upon the foundation we lay out in this one. Chapter 2 explores the technological enablers of disruption in health care. Chapters 3 and 4 show how the business models of hospitals and physicians' practices must change in order to harness the power of disruption to make health care affordable and conveniently accessible, while Chapter 5 addresses the type of business model innovation necessary to transform the management of chronic disease. Finally, Chapter 6 explores which companies and industry executives are and are not in a position to lead these disruptive innovations—and what they need to do to get the job done.

The disruptive innovation theory explains the process by which complicated, expensive products and services are transformed into simple, affordable ones. It also shows why it is so difficult for the leading companies or institutions in an industry to succeed at disruption. Historically, it is almost always new companies or totally independent business units of existing firms that succeed in disrupting an industry.

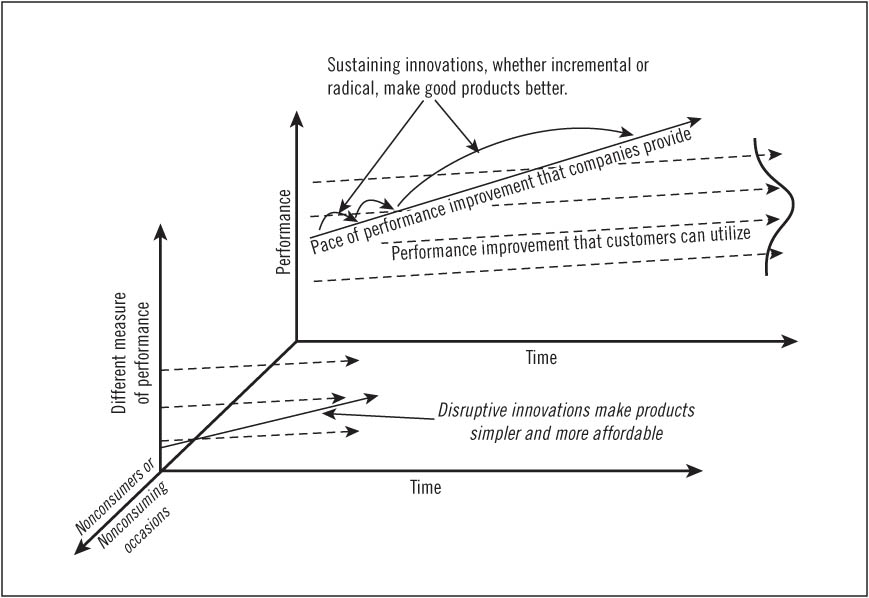

The theory's basic constructs are depicted in Figure 1.1, which charts the performance of a service or product over time. First, focusing on the graph in the back plane of this three-dimensional diagram, there are two types of improvement trajectories in every market. The solid line denotes the pace of improvement in products and services that companies provide to their customers as they introduce newer and better products over time. Meanwhile, the dotted lines depict the rate of performance improvement that customers are able to utilize. There are multiple dotted lines to represent the different tiers of customers within any given market, with the dotted line at the top representing the most demanding customers and the dotted line at the bottom representing customers who are satisfied with very little.

As these intersecting trajectories of the solid and dotted lines suggest, customers' needs in a given market application tend to be relatively stable over time. But companies typically improve their products at a much faster pace so that products that at one point weren't good enough ultimately pack together more features and functions than customers need. A useful way of visualizing this is to note how car companies give customers new and improved engines every year, but customers simply cannot use all of this improvement because of speed limits, traffic jams, and police officers.

Innovations that drive companies up the trajectory of performance improvement, with success measured along dimensions historically valued by their customers, are said to be sustaining innovations. Some of these improvements are dramatic breakthroughs, while others are routine and incremental. However, the competitive purpose of all sustaining innovations is to maintain the existing trajectory of performance improvement in the established market. Airplanes that fly farther, computers that process faster, cellular phone batteries that last longer, and televisions with larger screens and clearer images are all sustaining innovations. We have found in our research that in almost every case the companies that win the battles of sustaining innovation are the incumbent leaders in the industry. And it seems not to matter how technologically challenging the innovation is. As long as these innovations help the leaders make better products which they can sell for higher profits to their best customers, they figure out a way to get it done.

The initial products and services in the original "plane of competition" at the back of Figure 1.1 are typically complicated and expensive so that the only customers who can buy and use the products, or the only providers of these services, are those with a lot of money and a lot of skill. In the computer industry, for example, mainframe computers made by companies like IBM comprised that original plane of competition from the 1950s through the 1970s. These machines cost millions of dollars to purchase and millions more to operate, and the operators were highly trained professionals. In those days, when someone needed to compute, she had to take a big stack of punched cards to the corporate mainframe center and give it to the computer expert, who then ran the job for her. The mainframe manufacturers focused their innovative energies on making bigger and better mainframes. These companies were very good, and very successful, at what they did. The same was true for much of the history of automobiles, telecommunications, printing, commercial and investment banking, beef processing, photography, steel making, and many, many other industries. The initial products and services were complicated and expensive.

FIGURE 1.1 Model of disruptive innovation

Occasionally, however, a different type of innovation emerges in an industry—a disruptive innovation. A disruptive innovation is not a breakthrough improvement. Instead of sustaining the traditional trajectory of improvement in the original plane of competition, the disruptor brings to market a product or service that is actually not as good as those that the leading companies have been selling in their market. Because it is not as good as what customers in the original market or plane of competition of Figure 1.1 are already using, a disruptive product does not appeal to them. However, though they don't perform as well as the original products or services, disruptive innovations are simpler and more affordable. This allows them to take root in a simple, undemanding application, targeting customers who were previously nonconsumers because they had lacked the money or skill to buy and use the products sold in the original plane of competition. By competing on the basis of simplicity, affordability, and accessibility, these disruptions are able to establish a base of customers in an entirely different plane of competition, as depicted in the front of Figure 1.1. In contrast to traditional customers, these new users tend to be quite happy to have a product with limited capability or performance because it is infinitely better than their only alternative, which is nothing at all.

The personal computer is a classic example of a disruptive innovation. The first personal computers (PCs), like the Apple IIe, were toys for children and hobbyists, and the first adult applications were simple things like typing documents and building spreadsheets. Any complex computational problem still had to be served by the back plane of competition, where experts with mainframe computers ran the jobs for us. However, the performance of these simple PCs just kept getting better and better. As they became good enough, customers whose needs historically had required the more expensive mainframe and minicomputers were drawn one by one, application by application, from the back into the front plane of competition.

None of the customers of mainframe or minicomputer companies like Control Data Corporation (CDC) and Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC) could even use a personal computer during the first 10 years that PCs were made; PCs just weren't good enough for the problems they needed to solve. When CDC and DEC listened to what their best customers needed, there was no signal that a personal computer was important—because it wasn't to them. And when they looked at the financials, the personal computer market looked bleak. The $800 in gross margin that could be earned from selling a personal computer paled in comparison to the $125,000 in margin per unit that DEC could earn when it sold a minicomputer, or to the $800,000 in margin that Control Data could earn when it sold a mainframe.

Eventually, every one of the makers of mainframe and minicomputers was killed by the personal computer. But they weren't killed simply because the margins and volumes were different. The PC simply got better at doing more things. And it wasn't because the technology was difficult; in fact, given their industry expertise, companies like DEC could build some of the best PCs in the world. But it never made business sense for them to pursue the personal computer market. Even when PCs were becoming good enough to do much of what mainframes and minicomputers could do, the business model at companies like DEC could only prioritize even bigger and faster mainframes or minicomputers.

The only one of these companies that didn't fail was IBM, which for a time became a leader in personal computers by setting up a completely independent business unit in Florida and giving it the freedom to create a unique business model and compete against the other IBM business units.

The Kodak camera, Bell telephone, Sony transistor radio, Ford Model T (and more recently Toyota automobiles), Xerox photocopiers, Southwest Airlines' affordable flights, Cisco routers, Fidelity mutual funds, Google advertising, and hundreds of other innovations, all did or are doing the same thing. They used disruption to transform markets that had been dominated by complicated, expensive services and products into simple and affordable ones.

In each of these cases, the companies that had successfully sold their products or services, often dominating industries for decades, almost always died after being disrupted. Despite their stellar record of success in developing sustaining innovations, the incumbent leaders in an industry just could not find a way to maintain their industry leadership when confronted with disruptive innovations. The reason, again, is not that they lack resources such as money or technological expertise. Rather, they lack the motivation to focus sufficient resources on the disruption.

During the years in which a commitment to succeed with a new innovation needs to be made, disruptions are unattractive to industry leaders because their best customers can't use them and they are financially less attractive to incumbents than sustaining innovations. In a company's resource allocation process, proposals to invest in disruptive innovations almost always get trumped by next-generation sustaining innovations simply because innovations that can be sold to a firm's best customers for higher prices invariably appear more attractive than disruptive innovations that promise lower margins and can't be used by those customers. In the end, it takes disruptive innovations to change the landscape of an industry dramatically.

An industry whose products or services are still so complicated and expensive that only people with a lot of money and expertise can own and use them is an industry that has not yet been disrupted. This is the situation in legal services, higher education, and, yes, health care. The overarching theme of this book, however, is that these processes of disruption are beginning to appear in health care. One by one, disorders that could be treated only through the judgment and skill of experienced physicians in expensive hospitals are becoming diagnosable and treatable by less expensive caregivers working in more accessible and affordable venues of care. True to form, most of these innovations are being brought into the industry by new entrants, and they are being ignored or opposed by the leading caregiving institutions for perfectly rational reasons.

We mention above that of all the companies that made mainframe computers, IBM was the only one to become a leading maker of minicomputers; and of all the companies that made minicomputers, IBM was the only one that became a leading maker of personal computers. The reason is that IBM was the only company that invested to create new business models whose capabilities were tailored to the nature of competition in these disruptive markets. The others, if they attempted at all to participate in these emerging market segments, did so by trying to commercialize the disruptive products from within their existing business model.

So what is a business model? It is an interdependent system composed of four components, as illustrated in Figure 1.2.1 The starting point in the creation of any successful business model is its value proposition—a product or service that can help targeted customers do more effectively, conveniently, and affordably a job that they've been trying to do. Managers then typically need to put in place a set of resources—including people, products, intellectual property, supplies, equipment, facilities, cash, and so on—required to deliver that value proposition to the targeted customers. In repeatedly working toward that goal, processes coalesce. Processes are habitual ways of working together that emerge as employees address recurrent tasks repeatedly and successfully. These processes define how resources are combined to deliver the value proposition. A profit formula then materializes. This defines the required price, markups, gross and net profit margins, asset turns, and volumes necessary to cover profitably the costs of the resources and processes that are required to deliver the value proposition.

Over time, however, the business model that has emerged begins to determine the sorts of value propositions the organization can and cannot deliver. While the starting point in the creation of a business model is the value proposition, once a business model has coalesced to deliver that value proposition, the causality of events begins to work in reverse, and the only value propositions that the organization can successfully take to market are those that fit the existing resources, processes, and profit formula. In other words, the available business model is often the constraint to the realization of a disruptive technology's full potential.

A business model innovation is the creation of a new set of boxes, coherently established to deliver a new value proposition.2 Because the value proposition is the starting point for every business model, in the next few pages we take you on a deep dive into the concept of "helping customers do more effectively, conveniently, and affordably a job they've been trying to do." Understanding the job that customers are trying to do is critical to successful innovation, and we draw upon this concept in several of the subsequent chapters.

FIGURE 1.2 Elements of a business model

The way in which companies choose to define market segments is a crucial strategic decision, because it influences which products they develop, drives the features of those products, and shapes how they are taken to market.

Most marketers divide their markets into categories based on the characteristics of their products or customers. Automakers, for example, segment their markets by product characteristics. There are subcompacts, compacts, midsize and full-size cars; minivans, SUVs, luxury vehicles, and sports cars. They can tell you exactly how large each segment is and which competitor has what share. With this framing of the market's structure, they try to beat the competitors in their segments by adding more features faster and at the lowest cost. Meanwhile, other companies segment their markets based on the characteristics of their customers. There are low-, middle-, and high-income segments; the segment of 18- to 34-year-old women; and so on. Or, in the business-to-business world, they'll segment by small, medium, and large enterprises, industry verticals, and so on. Almost all managers frame their market's structure by product category and/or customer category because if you're in the company looking out on the market, this is indeed how things appear to be structured.

The problem with segmentation schemes such as these is that this is not at all what the world looks like to customers. Stuff just happens to customers. Jobs arise in their lives that they need to do, and they hire products or services to do these jobs. Marketers who seek to connect with their customers need to see the world through their eyes—to understand the jobs that arise in customers' lives for which their products might be hired. The job, and not the customer or the product, should be the fundamental unit of marketing analysis.

To illustrate what a job is and how much clearer the path to successful innovation can be when marketers segment by job, we offer illustrations below from the fast food and textbook industries, where companies historically have segmented markets by product and customer categories but would greatly benefit from segmenting by job.

A chain of fast-food restaurants some time ago resolved to improve sales of its milkshake.3 Its marketers first defined the market segment by product—milkshakes—and then segmented it further by profiling the customer most likely to buy milkshakes. They would then invite people who fit this profile to suggest how the company could improve the milkshakes so they'd buy more of them. The panelists would give clear feedback, and the company would improve its product—but this had no impact on sales whatsoever.

One of our colleagues then spent a long day in a restaurant to understand the jobs that customers were trying to get done when they "hired" a milkshake. He chronicled when each milkshake was bought, what other products the customers purchased, whether they were alone or with a group, whether they consumed it on the premises or drove off with it. He was surprised to find that over 40 percent of all milkshakes were purchased in the early morning. These early-morning customers almost always were alone; they did not buy anything else; and they left the restaurant to consume the milkshake in their cars.

The researcher returned the next day to interview the morning customers, milkshakes in hand, as they emerged from the restaurant. He essentially asked (in language that they would understand), "Excuse me, but could you please tell me what job you were needing to get done for yourself when you came here to hire that milkshake?" As the customers struggled to answer, he'd help them by saying, "Think about a recent time when you were in the same situation, needing to get the same job done, but you didn't come here to hire a milkshake. What did you hire?" Most of them, it turned out, bought it to do a similar job: they faced a long, boring drive to work. One hand had to be on the steering wheel, but they had an extra hand and there was nothing in it. They needed something to do with that hand to keep them occupied during the drive. They weren't hungry yet, but knew that they'd be hungry by 10:00 A.M., so they needed something now that would stay in their stomach for the morning. And they faced constraints: they were in a hurry, they were wearing work clothes, and they had (at most) one free hand.

In response to the researcher's query about what other products they hired to do this job, the customers realized that sometimes they hired bagels to do the job. But bagels were dry and tasteless. Bagels with cream cheese or jam resulted in sticky fingers and gooey steering wheels. Sometimes these commuters bought a banana, but it didn't last long enough to solve the boring-commute problem. Doughnuts didn't carry people past the 10:00 A.M. hunger attack. A few had hired a candy bar to do the job, but it made them feel so guilty that they didn't do it again. The milkshake, it turned out, did the job better than any of these competitors. It took people 20 minutes to suck the viscous milkshake through the thin straw, thus addressing the boring-commute problem. It could be eaten cleanly with one hand. And though they had no idea what the milkshake's ingredients were, they did know that at 10:00 A.M. on days when they had hired a milkshake, they didn't feel hungry. It didn't matter that it wasn't a healthy food, because becoming healthy wasn't the job they were hiring the milkshake to do.

Our colleague observed that, at other times of the day, parents often bought milkshakes, with a meal, for their children. What job were the parents trying to do? They felt like mean parents because they had been saying no to their children all week long, and they hired milkshakes as an innocuous way to placate their children and to feel like loving parents. The researchers observed that the milkshakes didn't do this job very well, though. They saw parents waiting impatiently after they had finished their own meal while their children struggled to suck the thick milkshake up through the thin straw.

Customers were hiring milkshakes for two very different jobs. But when marketers had asked a busy father who needs a time-consuming milkshake in the morning (and something very different later in the day) what attributes of the milkshake they should improve upon, and when his response was averaged with those of others in the same demographic segment, it led to a one-size-fits-none product that didn't do well either of the jobs for which it was being hired.

Once the company understood the jobs that the customers were trying to do, however, it became very clear which attributes of the milkshake would do the job even better, and which improvements were irrelevant. How could it better tackle the boring-commute job? Make the shake even thicker, so it would last longer. And swirl in tiny chunks of fruit, nuts, or candy so that the drivers would occasionally suck chunks into their mouths, adding a dimension of unpredictability and anticipation to their monotonous morning routine. Just as important, it could move the dispensing machine in front of the counter and sell customers a prepaid swipe card so that they could dash in, gas up, and go without getting stuck in the drive-through lane. Addressing the other job to be done with the children would entail a very different product, of course.

As Peter Drucker said, "The customer rarely buys what the company thinks it is selling him."4

Understanding the job and improving the product so that it would do the job better would enable the company's milkshakes to gain share against the real competition—not just competing chains' milkshakes, but doughnuts, bagels, bananas, and boredom. This would grow the category, which brings us to an important point: job-defined markets are generally much larger than product category-defined markets. Marketers who are stuck in the mental trap that equates market size with product categories don't understand who they are competing against or how to enhance the value of their product, from the customer's point of view.

Before it understood the job for which its milkshake was being hired in the morning, the company had thought it was integrated. It sold a dizzying array of sandwiches, side dishes, salads, drinks, and desserts. But this integration simply helped it to do anything for anyone, and not very well. This mode of integration simply pitted its plethora of products into a product-for-product competition—against bananas, doughnuts, bagels, breakfast drinks, coffee, diet cola, and other fast-food products. But once it understood the morning commute job, the restaurant chain could integrate differently—linking together an optimized product, a delivery mechanism, and a payments system that together did the job perfectly—in a way most makers of the competing products couldn't replicate because they didn't see the rationale. Proprietary integration of the company's resources, processes, and profit formula in order to do a job that the customer is trying to do is the essence of competitive advantage.

Very often, customers will tell market researchers, "Sure, I'd buy that product," and then they don't. Why? A second case history provides some clues.

In the past decade the college textbook companies together have spent several billion dollars creating Web sites where students can explore more deeply topics that can be covered at only a cursory level in the textbook. In a geography textbook, for example, only about 10 pages can be allocated to the Amazon rain forest because there is so much other geography to cover. But thank goodness for the Internet. At the end of the text on the Amazon rain forest is a Web site address, which students can visit to get almost limitless additional information about the rain forest. Overwhelmingly, students and their professors indicated during market research interviews that they would love to have that capability.

It has turned out, however, that very few students ever click on those links. Why? What most students really are trying to get done in their lives (as evidenced by what they do, rather than what they say) is simply to pass the course without having to read the boring textbook at all. They should have a limitless appetite for learning—but they don't.

So what's the solution? Face the facts. When you help customers do more affordably, conveniently, and effectively a job that they have been trying to get done, they will pay a premium price, digest all kinds of instructions, and change lots of habits in order to get the job done better and faster. But when your product helps them do a job that they've not been trying to do, selling your product is akin to an uphill death march through knee-deep mud.

This doesn't mean that the idea of online or electronic books is dead. It simply means that if textbook companies wanted students to start using their Internet-based learning materials, they need to package them in a way that helps college students do the job that they're trying to do. In this case, you'd create a facility called Cram.com with the objective of helping college students cram for their exams more effectively, with less effort, later in the semester. These customers would be willing to pay steep prices for this assistance. The stereotypical student would feverishly log on to Cram.com two days before his final. The screen would ask, "What course are you trying to cram for?" The student would click on "College Algebra." The next page would ask, "Which of these textbooks did your old professor think you'd have read by now?" After he clicked on the title, the next page would ask, "Now, which of these problems is giving you a hard time?" The student would click on one that is vexing him, and the next pages would nurse him through the problem, giving him tricks and methods for solving it.

Next year, like any disruptive company, Cram.com would need to improve its products—to make it even easier to cram even later in the semester, with even better results. Within a few years, you might see a couple of students in their college bookstore anguishing over whether they should really pay $129 for a textbook. Another student, walking by, would notice their pain and offer, "I wouldn't buy the book. I took that course last semester, and I just used Cram.com from the beginning—and it worked great." Bingo. The disruption of a horrifically expensive industry would be underway.

The graveyard of failed products and services is populated by things that people should have wanted—if only they could have been convinced those things were good for them. The home-run products in the marketing hall of fame, in contrast, are concepts that helped people more affordably, effortlessly, swiftly, and effectively do what they already had been trying to get done.

In ensuing chapters, readers will find that understanding the job that customers are trying to do is a major issue in every health-care innovation. Many wellness programs that seek to ameliorate or stave off the onset of certain chronic diseases stumble, for example, because for a great many people who are obese, are addicted to tobacco, or who suffer from coronary artery disease, becoming healthier isn't a job that they're prioritizing—until they become sick. Indeed, as we show in our discussion of chronic disease in Chapter 5, for certain patients, financial health is a much more pressing job-to-be-done than physical health. Our analysis in Chapter 7 explains the reason why health savings accounts have been adopted more slowly than expected: because they're being marketed into a product category, and not positioned to fulfill a job-to-be-done.

There are three levels in the architecture of every job. The highest level is the job itself—the basic, root problem the customer needs to resolve, or the result he or she needs to achieve. Once innovators understand the job, they can then burrow into the second level of the architecture: What functional, social, and emotional experiences in purchasing and using the product do we need to provide the customer in order to get the job done perfectly? Knowing what these experiences need to be gives product designers and marketers a sense of "true north" as they delve into the detail at the third level of the architecture: the specific characteristics, features, and technologies that comprise the product and how it is sold and used. If a feature helps provide one of the experiences that is required to get the job done perfectly, it will enhance the product's success. If not, then it will add cost and complexity to the product that customers don't value. Understanding the job to be done provides a sense of "true north" to innovators.

What this means is that convenience and cost are not jobs. Convenience is an experience that must be provided to get some, but not all, jobs done well. And cost, likewise, is a feature of products that customers will assess when deciding what product to hire to do a job.

Jobs exist independently of a market for products that can be hired to do them. By illustration, since the days of Julius Caesar there's been an I-need-to-get-this-from-here-to-there-with-perfect-certainty-as-fast-as-possible job. Caesar's only option was to put someone he trusted in a chariot pulled by a fast horse and order him to go like crazy. When FedEx came along, a huge new market was created—but the job had always been there. And the job exists independently of customers as well. Not every person has this job to do, and those who find themselves needing to do this job don't need to do it every day.

In our research on disruptive innovation, as noted earlier, the only instances in which the original market leader in the back plane of Figure 1.1 also became the subsequent leader in the new disruptive plane of competition occurred when the leader set up a completely autonomous business unit whose value proposition focused on a job to be done. This independent business unit was given the freedom to create a different profit formula, permitting it to make money on lower margins than the parent ever could. This required, in turn, processes and resources that were markedly different and that could deliver the disruptive value proposition under the new profit formula.

The history of innovation is littered with companies that had a disruptive technology within their grasp but failed to commercialize it successfully because they did not couple it with a disruptive business model. An example of a disruptive technology that withered in the absence of a disruptive business model occurred at Nypro, a successful manufacturer of high-precision plastic products in Clinton, Massachusetts. The Nypro business model, which it replicates in each of its 60-plus plants around the world, centers on a single value proposition: making ultra-high-precision parts in high volumes for the world's largest product companies, including Nokia (mobile phones), Hewlett-Packard (printer components), and Eli Lilly (insulin injection pens). To make high volumes of precise parts at low costs for customers such as these, Nypro utilized resources such as multicavity molds that could yield as many as 32 parts with a single stroke of its molding machines. In order to squeeze plastic into that many cavities, Nypro's molding machines had to inject the plastic at very high pressures—meaning the machines had to be huge and powerful. And because the technology was so complex, the processes that developed at Nypro involved long setup times to ensure that perfect parts were made in each of the molds' cavities. For Nypro's plant managers, this meant that very long runs of standard parts were extremely attractive, because the company's profit formula necessitated high yields and equipment utilization to support the cost of its resources.

In the mid-1990s Nypro's founder and CEO, Gordon Lankton, foresaw a change in the company's future: the product markets of Nypro's customers were beginning to fragment. This portended that the market for parts produced in high volumes would diminish, giving way to a much wider variety of parts produced in shorter production runs. To help Nypro catch this new wave of growth and deliver this new value proposition, Lankton's engineers developed a new injection molding machine dubbed Novaplast. It used only four-cavity molds that could be snapped into place quickly and filled precisely with low pressures. Its features were cleverly designed to produce a wide variety of low-volume parts without the cost penalties that would have been incurred by using the larger and more powerful machines.

Lankton considered building a special plant with its own sales force to pursue this high-variety, low-volume-per-part business, but he ultimately decided instead to leverage the company's existing resources, such as its sales and manufacturing infrastructure, offering to lease the Novaplast machine on attractive terms to his plant managers. Only nine plant managers took Lankton up on his offer, and seven of them returned the machines after just three months, complaining that there was no business to keep the machines utilized. When Lankton inquired why the other two plants kept their Novaplast machines, he learned those plants had previously struggled to use traditional 32-cavity molds to produce the extremely thin plastic liners that were inserted inside AA battery canisters. It turned out, serendipitously, that the Novaplast machine could make those standard, high-volume parts with much higher yields.

Why did so few plant managers take the Novaplast machine in the first place? Despite the burgeoning market for high-variety, low-volume-per-part products, orders to produce a wide variety of parts in low volumes simply weren't attractive to Nypro plant managers. They weren't consistent with Nypro's business model, because they didn't support the existing profit formula and help the company's plants make money in the way they were structured to make money. Why did seven of the nine plants conclude there was no demand for low-volume parts, even though the company's CEO had already seen that there was booming demand? Because selling low-volume parts didn't fit the compensation structure of the Nypro sales force. The salespeople had little reason to push a large number of low-volume products when all the incentives of the sales process were aligned with turning out high-volume runs for their existing customers. Finally, the two plants that actually kept their Novaplast machines only did so because they were able to use the machine by plugging the resource right into their existing business model—thereby making extremely high volumes of precision thin-walled battery liners.

In other words, those within a business model cannot disrupt themselves. Managers can only implement new technologies in ways that sustain the model within which they work. Although the Novaplast machine was capable of attacking the growing wide-variety, low-volume-per-part market, the business model in which it was ensconced was not. Lankton's vision actually proved correct: the market for high-variety, low-volume parts grew significantly, while the market for standard, high-volume parts declined. Yet the only way Nypro could have attacked that market would have been to embed the Novaplast machine within an autonomous business model whose profit formula, processes, and resources were optimized for the disruptive value proposition.5

Professor Øystein Fjeldstad of the Norwegian School of Management and his colleague Charles Stabell have developed a framework that defines three general types of job-focused business models: shops, chains, and networks. For purposes of added clarity in this book, we refer to these three types as solution shops, value-adding process (VAP) businesses, and facilitated networks.6 As we will demonstrate, these are fundamentally different institutions, in terms of their purpose, where their capabilities reside, and the formulas by which they make money.

Solution shops are institutions structured to diagnose and recommend solutions to unstructured problems. Certain consulting firms, advertising agencies, research and development organizations, and many law practices are examples of solution shops. The ability to deliver value to customers resides primarily in the firms' resources, the most significant of which is the people these firms employ—experts who draw upon their intuition, training, and analytical and problem-solving skills to diagnose the cause of complicated problems and then recommend solutions. The work they do for each customer tends to be unique and can vary from project to project, firm to firm.

Almost always, solution shops charge their clients on a fee-for-service basis. Consulting firms will occasionally make a portion of their fees contingent upon the successful results of their recommendations, but such arrangements rarely are satisfactory for either party—there are simply too many variables in addition to the consultants' diagnoses and recommendations that affect the outcome. Because diagnosing the cause of complex problems and devising workable solutions have such high subsequent leverage, customers typically are quite willing to pay very high prices for the services of solution shops—often topping $1,000 per hour for the services of a partner at a leading consulting or law firm.

The diagnostic activities in general hospitals and much of the work done in specialist physicians' practices are solution shop activities. In Chapter 2, we give the work done in medical solution shops a new label: intuitive medicine. In these institutions, highly trained experts use their intuition to synthesize data from a wide range of analytical and imaging equipment, and from personal examinations of the patient. They will then distill hypotheses of the causes of patients' symptoms from these data. When the diagnosis has only the precision of a hypothesis, these experts typically test the hypothesis by applying the most appropriate therapy. If the patient responds, the hypothesis is essentially verified. If not, the experts must then iterate through cycles of hypothesis testing until the diagnosis can be made with as much certainty as possible.

We show in Chapter 5 that there are today only a few entities in health care that qualify as true, coherent solution shops. Most intuitive medicine, unfortunately, is practiced in a disconnected way by individual specialists.

The second type of business model is the value-adding process (VAP) business. VAP businesses transform inputs of resources—people, materials, energy, equipment, information, and capital—into outputs of higher value. Retailing, restaurants, automobile manufacturing, petroleum refining, and the work of many educational institutions are examples of value-adding process businesses. Because value-adding process organizations tend to do their work in repetitive ways, the capability to deliver value tends to be embedded in processes and equipment. They are not nearly as dependent upon the instincts of people as is the case with solution shop businesses. Because of this, VAP businesses that focus on process excellence can consistently deliver high-quality services and products at lower cost, using methods that are far less susceptible to the variability that often vexes businesses whose results primarily depend on their employees' intuition. Of course, outcomes can still vary, because some value-adding process organizations are more efficient and consistent than others.7

Many medical events and procedures are in fact value-adding process activities in that what needs to be done can be verified ahead of time and that a relatively standardized process can be followed to rectify the problem. Certainly, the diagnosis of many problems and the decisions about how to solve them must often still be made in the solution shops of hospitals or physicians' practices. But whenever a definitive diagnosis can be made, the treatment that follows can typically be performed in a value-adding process organization. Just like the more familiar examples of value-adding process models employed by restaurants, business schools, or automobile manufacturers, a patient is brought in, a relatively standard sequence of events is performed, and then the patient is "shipped" out the door.

When value-adding process procedures like the ones described above are delivered by business models that are organizationally independent from solution shops, the overhead cost of the value-adding process work drops dramatically. As a case study in Chapter 3 demonstrates, focused value-adding process hospitals and clinics often can deliver care at prices that are 40 to 60 percent below those incurred in hospitals and physicians' practices, where the value-adding process and solution shop business models are typically intermingled.8 Retail clinics such as RediClinic and MinuteClinic (which was acquired in 2007 by CVS-Caremark); surgical specialty hospitals like Shouldice Hospital and some orthopedic hospitals; ambulatory surgical centers including many eye surgery clinics; and medical specialty hospitals like cardiology hospitals and cancer centers are all part of a growing number of value-adding process businesses in the health-care industry.9 And the patients and diseases that can be managed by VAP businesses are not necessarily limited to the simple end of the spectrum. Transplant services are now often managed as a bundle of services and priced per outcome in a VAP model.10

Because their ability to deliver value to customers tends to be embedded in equipment and processes rather than the individual intuition of people, value-adding process businesses typically bill their customers for results, not inputs. Often, the product or outcome is priced in advance, and because costs and outcomes are relatively predictable, most value-adding process organizations can guarantee their products. If they don't work or should they break, they'll be replaced or repaired free of charge. While most general hospitals charge on a fee-for-service basis for everything they do, many value-adding process hospitals have begun to charge their patients on a fixed-price basis for each procedure offered. And they guarantee the result. In February 2006, Geisinger Health System's ProvenCare program began charging insurers a flat rate for elective heart bypass surgeries, effectively providing a 90-day warranty for its work.11

The employees of Toyota, which is probably the best value-adding process company in the world, follow a standard process religiously in everything that they do—from training employees to maintaining and repairing equipment to designing and making cars. The reason they adhere to standard processes isn't to make the work mindless, however. Rather, they have concluded that doing it the same way every time actually constitutes a controlled experiment by which they test over and over whether doing it that way yields a perfect result. In less mature or experimental processes, where unanticipated problems can arise, Toyota designs methods to respond to these problems in a consistent way—to test whether their method of solving unanticipated problems is a reliable method for doing so. By the same token, we should not expect value-adding process clinics to be manned with robotic personnel who cannot respond to unanticipated problems that might arise during the course of a procedure. Instead, they should be much more able to anticipate and address the unexpected problems that will undoubtedly arise, but in a predictably effective way. These core principles of the Toyota Production System have already been applied to processes within hospitals like Virginia Mason Medical Center in Seattle and the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center to improve quality of outcomes and patient safety.12

The third type of business model, facilitated networks, comprise institutions that operate systems in which customers buy and sell, and deliver and receive things from other participants.13 Much of consumer banking is a network business in which customers will make deposits and withdrawals from a collective pool. Casinos, Second Life, and multiplayer Internet games could also be termed facilitated networks. Approximately 40 percent of the GNP in many economies is generated by facilitated network businesses.14

The companies that make money in network industries are the ones that organize, facilitate, and maintain the effective operation of the networks. Whereas solution shops price on a fee-for-service basis, and value-adding process businesses can price on a fee-for-outcome standard, facilitated networks typically make money through membership or transaction-based fees.

In many network business models, the dependency among customers is the main product delivered. Said another way, the networked users themselves are the key part of the product, and the "size and composition of the customer base are therefore the critical driver[s] of value." Whereas most of the economics literature on the subject of network externalities addresses the size of the network, the compatibility of members is more important.15

As we discuss further in Chapter 5, facilitated networks are now beginning to emerge in health care to address problems in very new ways. Some network businesses tie professionals together to help support each other as they do their work. Sermo, an online community of physicians,16 and some disease management organizations have taken preliminary steps to facilitate provider networks. Other networks are organized around patients and specific conditions. In many cases, they offer an effective business model for the care of chronic diseases, particularly those which demand from patients and their families significant behavioral changes.17 Examples include social networking Web sites such as PatientsLikeMe.com, which focuses on communities of patients with multiple sclerosis, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (Lou Gehrig's disease), Parkinson's disease, and HIV; and CarePlace, which connects users with rare diseases.18 Meanwhile, Waterfront Media and WebMD are harnessing vast amounts of patient and insurer data to generate an extensive facilitated network that will offer patients the ability to find "someone like me." Patients will be able to compare their own progress against directly comparable patients and teach and learn from each other.19

Until now, the care of patients with chronic diseases has been centered in physicians' practices, but these solution shops are simply ill-equipped to meet many of the demands of chronic disease care. Just as value-adding process hospitals can outperform solution shops by delivering higher-quality outcomes at far lower costs, facilitated networks can improve quality and reduce costs for certain chronic diseases by a similar magnitude.20

Most historical examples of disruptive innovation have occurred within a single type of business model. The Boston Consulting Group disrupted McKinsey within the solution shop class of business models. Toyota has disrupted Ford, and Medco is disrupting retail pharmacies within the class of value-adding process business models. Traditional wire-line telephone companies, which are network facilitators, were disrupted by the wireless carriers, which in turn are being disrupted by Skype, which is facilitating a mobile network using voice over Internet protocol (VOIP).

However, a more fundamental disruption occurs when one type of business model displaces another. eBay is a network facilitator, for example, but it is disrupting certain retail and distribution channels that historically were configured as value-adding process businesses.21 The top section of Figure 1.3 gives some examples of disruptions in a variety of industries that occurred within a business model type. The examples in the bottom section are companies that transformed, or are transforming, the type of business model. When disruption occurs across different classes of business models, the gains in affordability and accessibility are even more profound than when disruption occurs within the same type of business model.

The appendix to this chapter briefly summarizes why we classified the disruptive companies in Figure 1.3 in the way that we did.

We foresee three phases of disruptive business model innovation in health care, which together hold the potential to reduce costs by between 20 and 60 percent, depending on the situation—while at the same time improving the quality and efficacy of care received.22 The first phase will entail carving hospitals apart, creating coherent rather than disjointed solution shops, value-adding process businesses, and facilitated networks as focused business models. These will employ similarly qualified doctors, but their significantly lower overhead burden qualifies them as disruptive relative to our hospitals as they currently work. Second, we foresee lower-cost disruptive business models emerging within each of these categories—disruptors akin to those companies in the top row of Figure 1.3. Among solution shops, for example, a telemedicine-based institution would be a disruptive business model to the diagnostic activities of certain hospitals and physicians' practices. Ambulatory and mobile clinics will represent value-adding process business models that can disrupt specialty hospitals, and so on. The third phase of disruption will occur across business model types. Retail clinics, for example, transfer the ability to care for rules-based disorders from solution shops to value-adding process businesses. Firms like SimulConsult, through which the published research of thousands of specialist physicians is integrated on the computers of primary care physicians, disrupts the solution shop of specialists with a professional network business model. We explore each of these possibilities in greater depth in subsequent chapters of this book—after we examine the role of technological enablers in disruption in Chapter 2.

FIGURE 1.3 Examples of disruption within and across business model type

The Disruption of Angioplasty |

A narrowing of the arteries, whether caused by cholesterol deposition, high blood pressure, or myriad other causes, is a common problem that can affect blood vessels throughout the body. When intervention is warranted, the typical treatment involves inserting a catheter, inflating a balloon to expand the narrowed portion of the vessel, and inserting a stent to keep the area propped open. Yet today, though the same technologies and techniques are used, a patient who needs angioplasty of the heart will see an interventional cardiologist; a patient who needs angioplasty of the kidney might see an interventional radiologist; a patient who needs angioplasty of a carotid artery in the neck may visit a vascular surgeon; and a patient with peripheral disease, such as in the leg, could be treated by any one of the three. |

Much of this care is delivered today through solution shops that are organized around disease type or medical specialty. For example, cardiologists practicing angioplasty have been disrupting cardiac surgeons practicing coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) for 25 years. But this has largely occurred within the solution shop business model of the general hospital. However, we propose that these vascular interventions may be better suited for new disruptive business models that compete across very different categories. |

The first phase of disruption will involve the separation of the different business model types currently housed within general hospitals. Specialty heart hospitals were among the first focused value-adding process business models to break off from general hospitals, but disruption within this category can continue to affect how care is delivered. |

For example, as the field of angioplasty has developed, we've learned that the traditional categories of competition no longer make sense. Rather than cardiology, radiology, and vascular surgery patients, the competitive category is really the same for all of these patients—blood vessels. Patients undergoing this procedure, beginning with those with stable disease and low risk of complications, would be much better served by seeing a "vascular interventionalist" who does nothing but angioplasties day in and day out in a value-adding process business, surrounded by support staff who are experts in managing all the processes of angioplasty care, no matter which organ system happens to be involved. By reframing the categories of competition, the value-adding process business model allows you to bring scale and lower overhead costs to areas where you didn't have it before. |

Because these patients no longer need to be located with all the other processes meant to handle complex patients, they can be treated in a lower-cost, ambulatory facility. This new business model would be even more focused on a select few processes than the specialty cardiology hospitals that already exist today, and they would essentially disrupt other value-adding process businesses. |

Eventually, the vascular interventionalist we describe here may not even need to be a physician. A skilled interventionalist primarily requires video-gaming-like skills that a nonphysician could acquire through practice, and this would result in even further disruption of other, more costly value-adding process businesses. Peripheral vascular occlusive disease (PVOD) tends to be the simplest of the vascular diseases that undergo angioplasty and would be the most likely category of patients to be managed under a nonphysician technician first. However, we can foresee even multivessel cardiac cases eventually being handed off to a technician, while an interventional cardiologist will be involved, perhaps just as a supervisor, in those cases where there is a higher risk for complications.23 |

Of course, cardiologists, radiologists, and surgeons should continue managing the most complex vascular diseases, particularly when there are unpredictable interdependencies such as unstable disease or high risk for undesirable outcomes. But the number of patients who require their costly expertise will diminish over time as more care is handed off to value-adding process businesses that can focus on very specific procedures and techniques that cut across traditional disciplines and specialties—and that can deliver better outcomes at lower cost.24 |

Whether the changes described here would naturally lead to yet another phase of disruption across business model types remains to be seen. It's difficult to imagine today what that would look like, but we'll know it when we see it, and we hope our readers too will spot the opportunity when it does arrive. |

Amazon.com. Book and music retailing historically were value-adding process businesses. With its ratings system, discussion groups, and a network of resellers called Amazon Marketplace, Amazon is pushing these VAP activities toward a network facilitator business model. MP3 and electronic publishing technologies are enabling artists and authors to create and sell their own content to each other through the network that Amazon is facilitating.

Bain Capital. Bain Capital today is one of the world's largest private equity and leveraged buyout firms. In the investment business, the vertical axis on the diagram of disruption is the size of the company receiving the investment. Partners with limited time and lots of money to put to work will always opt to make a larger investment over a smaller one. Bain started by making rather small investments in start-ups like Staples, instead of attempting a head-on attack against Kohlberg Kravis Roberts & Co. Then little by little it raised more and more money, going after larger and larger deals.

Bloomberg. Bloomberg LLC started selling simple, low-value-added data to financial analysts, who used the data to analyze the problems and opportunities facing the companies in which they were considering investing. Gradually, Bloomberg integrated into its systems the ability to perform analyses so that anyone today who has a Bloomberg terminal simply needs to push a button to get even the most sophisticated of those analyses that previously had required a Wharton MBA.

Boston Consulting Group (BCG). In the consulting business, the vertical axis on the diagram of disruption is the size of the project. Given the choice, the partners (who are the salespeople) would much prefer to sell large projects to clients than small ones. When BCG entered the market in 1963 with a product offering in a new field it called "strategy," McKinsey was caught flat-footed for about 15 years. It's not that the McKinsey staff lacked the intellectual horsepower to compete against BCG in the strategy market. It's because strategy projects are inherently smaller than are operations improvement, postmerger integration, and reorganization projects. After establishing a foothold, BCG was able to move up-market, and now it does lots of operations and postmerger integration work—and less strategy work.

Canon. Photocopying formerly had been in the province of complex, electromechanical high-speed photocopiers made by Xerox, housed in corporate photocopy centers, and operated by technicians. Whereas IBM and Kodak attacked Xerox in a head-on battle of sustaining innovation (and got bloodied), Canon disrupted Xerox by starting with simple table-top boxes that were so slow and limited in their capabilities that none of Xerox's customers could use them. But the Canon machines were so simple and affordable that they could be located just around the corner from one's office. As they got better and faster, Canon's convenient, local machines began to pull jobs, one by one, away from the high-speed copy center.

Cellular telephony. Wireless telephones disrupted wire-line telephony—starting out as big, clunky car phones that often dropped calls when switching from one cell to the next. However, this was an application where wire-line phones were impossible. Then, little by little, the cell phones improved, to the point that many people no longer have wire-line phones.

Cisco. Because Cisco's router "packetized" information in virtual envelopes, addressed them, and then fanned them out over the Internet, it took about three seconds for the packets to arrive at their destination, be ordered correctly, and then opened and read. This was too slow for voice, but for data it was much faster than prior options (airmail). Makers of circuit-switching equipment for voice, such as Lucent, Nortel, and Alcatel, were disrupted as the router and its packet-switching technology ultimately became good enough for voice as well as data.

Community colleges. These schools don't operate under the cost burdens of full-time, research-oriented faculty. They simply teach—and do it quite well, often online. And they are booming. Many graduates of four-year universities took some or all of their first two years of general education at a community college, where credits for similar basic courses cost much less than they do at four-year schools. Many community colleges have subsequently become four-year universities.

eBay and PayPal. Retailing historically has been a value-adding process business. eBay started by facilitating a network through which people could exchange collectibles with each other. The range of products exchanged through the eBay network has gradually increased to encompass cars, boats, and even homes. Many companies now use eBay as their primary sales channel. Meanwhile, eBay's subsidiary PayPal is also a network facilitator business, disrupting the networks of Visa, MasterCard, and American Express, which are network facilitator businesses themselves.

Electronic clearing networks. ECNs are electronic, automated securities exchanges that are disrupting the NASDAQ exchange, which itself has been disrupting the New York Stock Exchange. Leading ECNs include Direct Edge, BATS trading, and Bloomberg Tradebook.

Fidelity Investments. The ability to own a diversified equity portfolio originally was limited to those with a very large net worth. Through its no-load mutual funds, Fidelity enabled a much larger population of people to become diversified equity investors. Fidelity is now being disrupted by Vanguard, which itself is being disrupted by exchange-traded funds (ETFs).

Ford. Henry Ford's Model T decisively transferred the design and manufacture of automobiles out of mechanics' garages, where artisans produced them one at a time. Their solution shops were disrupted by a value-adding process business model.

Geek Squad. This unit of the electronics retailing giant Best Buy is trying to routinize the installation and repair of home entertainment and computer systems—activities that historically had been addressed through small solution shops.

Google. Historically, most advertising and brand-building were done in the province of advertising agency solution shops. Google is transforming these activities into facilitated networks.

Innosight. For the same reasons that enabled the Boston Consulting Group to disrupt McKinsey, Innosight is on a trajectory by which it is disrupting the innovation and strategy consulting business. The company bases its work on theories of strategy and innovation, including those of Clayton Christensen, rather than approaching problems through data analysis. As a consequence, Innosight's work is priced substantially lower, and major consulting firms simply walk away.25

Kodak. Prior to 1890, most photographs were taken and developed in a solution shop environment by artists such as Matthew Brady. George Eastman disruptively transformed photography into a value-adding process business by selling film and an inexpensive Brownie-brand camera to the masses. Customers simply had to mail their shot rolls of film back to Kodak, where the photos were processed and returned to them.

Linux. Computer operating systems historically have been a value-adding process product. Linux is disrupting Microsoft's Windows by shifting the business model type to a facilitated network in which network participants build, improve, and use the product.

Second Life. Pixar, using digital technology, disrupted Disney Studios, which had developed animated content by hand. Both were value-adding process businesses. Second Life is a 3-D virtual world created by its residents, who use tools provided by the network facilitator to create their own animated content and to exchange and interact with others.

Skype. Owned by eBay, Skype is an in-type disruption of one facilitated network business by another. Voice-over-Internet-protocol (VOIP) telephony accounts for a growing share of global telephony traffic, and Skype has already begun its march into the markets of wireless carriers with Skype-branded phones that use VOIP technology.

Toyota. Toyota did not become the world's most profitable automobile manufacturer by attacking Mercedes, Cadillac, and BMW with its Lexus. Rather, it started at the low end of the market with a little subcompact branded Corona. Then it moved up-market with models whose American brands were Tercel, Corolla, Camry, Avalon, 4Runner, RAV4, and then the Lexus. Every once in a while General Motors and Ford would look at Toyota coming up from below and send down a Chevette or Pinto to compete against Toyota. But when the Americans compared the profitability of those subcompacts with the profitability of larger, more powerful SUV and luxury vehicles, it made no sense to defend the low end of the marketplace. Today, Toyota is being disrupted by Hyundai and Kia, which are being disrupted by Chery from China and the Tata Nano in India.

TurboTax. Intuit, which owns TurboTax, is shifting the tax preparation business from the solution-shop realm of tax advisors and preparers to a relatively automated, do-it-yourself value-adding process.

Wal-Mart and Target. Discount retailers are disrupting full-service department stores like Macy's. Until the 1960s, department stores sold the full "merchandise mix." This ranged from branded hard goods on the low-margin end—items like paint, hardware, kitchen utensils, toys, and sporting goods—to harder-to-merchandise soft goods like clothing and cosmetics, which were more difficult, and therefore more profitable, to sell. Discount retailers originally came in at the low end, focusing on branded hard goods that were already so familiar to users that they sold themselves. The department stores quickly fled up-market and became retailers of clothing and cosmetics exclusively. Now the discounters, especially Target, are moving resolutely into fashion soft goods.

1. We owe enormous gratitude to Mark Johnson, our colleague and chairman of Innosight, for his development of the business model innovation framework. See Johnson, M. Seizing the White Space: Business Model Innovation for Transformative Growth and Renewal (Boston, Massachusetts: Harvard Business School Press, 2009).

2. Typically, new-to-the-world business models are formed in the counterclockwise sequence as described. Some disruptive business model innovations, however, are built in a clockwise sequence. Disruption starts with a value proposition for a product or service that is much more affordable and simpler than those available previously. The disruptive innovators then specify the profit formula required to profitably hit the price envisioned in the value proposition. This then defines the sorts of processes the firm will need and the levels of resources required in order to profitably deliver the value proposition.

3. The descriptions of the product and company in this example have been disguised. We thank Rick Pedi and Bob Moesta of Pedi, Moesta & Associates for sharing this case with us and permitting us to publish it in disguised form. Though each has used different words for the phenomenon, the concepts presented in this section have been taught by a number of different scholars, including Ted Levitt and Peter Drucker. Though they are not as well known, we acknowledge the roles that Rick and Bob played in articulating this way of thinking, and we thank them again for their tutelage.

4. Drucker, Peter F., Managing for Results, London: Heinemann, 1964.

5. See Christensen, Clayton M., and Rebecca Voorheis, "Managing Innovation at Nypro, Inc. (A)," Harvard Business School case #9-696-061, and Christensen, Clayton M., "Managing Innovation at Nypro, Inc. (B)," Harvard Business School case #9-697-057.

6. We are deeply indebted to our friend Øystein Fjeldstad of the Norwegian School of Management, who developed and then taught us of this framework. Those interested in this framework should also read Stabell, Charles B., and Øystein D. Fjeldstad, "ConØystein "Configuring Value for Competitive Advantage: On Chains, Shops and Networks," Strategic Management Journal, May 1998. Professor Fjeldstad chose the terms value shops, value chains, and value networks for these three types of business models. He has graciously given us permission to use different names for each type. The reason we felt it necessary was that Michael Porter has applied the term "value chain" differently in some of his writings to the activities that occur across an entire supply chain. Similarly, Clayton Christensen used the term "value network" to apply to the set of businesses in a value chain that have mutually supportive and compatible business models. In many ways the names chosen by Professors Fjeldstad and Stabell are more elegant and simpler than the ones we've used here.

7. See, for example, Porter, Michael E., Competitive Advantage (New York: The Free Press, 1985).

8. For example, early data from a two-year study of claims at MinuteClinic, conducted by HealthPartners, revealed that visits cost $18 less than visits to other primary care clinics. Kershaw, Sarah, "Tired of Waiting for a Doctor? Try the Drugstore," New York Times, August 23, 2007, A1. The reimbursement for a 10-minute physician outpatient/office visit is roughly $60 according to the 2008 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (this is the amount of reimbursement for CPT 99213 at the nonfacility price, which reflects most small physician practices). Private insurers will reimburse largely in accordance with the Medicare schedule. The $18 difference between MinuteClinic and a primary care clinic would equate to approximately 30 percent savings. The Fee Schedule is available at http://www.cms.hhs.gov/PFSlookup/. In 1985, CardioVascular Care Providers, a bundled pricing plan for coronary artery bypass grafting at the Texas Heart Institute, had a combined facility and physician fee of $13,800 versus the average Medicare payment of $24,588—about 44 percent lower. See Edmonds, Charles, and Grady L. Hallman, "CardioVascular Care Providers: A Pioneer in Bundled Services, Shared Risk, and Single Payment," Texas Heart Institute Journal, vol. 22, no. 1, 1995. 72–76. In Chapter 3, we examine cost reductions at Shouldice Hospital.

9. Our colleague Regina Herzlinger, building upon earlier work by Harvard Business School professor Wickham Skinner, has written extensively on the value of focus. See Herzlinger, Regina, Market-Driven Health Care: Who Wins, Who Loses in the Transformation of America's Largest Service Industry (Reading, Massachusetts: Addison-Wesley, 1997).

10. We refer readers to the work of our colleague Michael Porter, who has emphasized the importance of creating competition based on value and results, using in particular the field of organ transplantation as a case study.

11. Abelson, R., "In Bid for Better Care, Surgery with a Warranty," accessed from http://www.nytimes.com/2007/05/17/business/17quality.html on August 14, 2008.

12. Our colleagues Richard Bohmer and Steve Spear have both researched and written extensively about the applications of the Toyota Production System in health care. More about these two particular examples can be found in Harvard Business School Publishing case #606044, "Virginia Mason Medical Center," by Richard Bohmer and Erika M. Ferlins; and Thompson, D. N., G. A. Wolf, and S. J. Spear, "Driving Improvement in Patient Care: Lessons from Toyota," Journal of Nursing Administration, vol. 33, 2003, 585–95.

13. "Customers" can include individual consumers and/or businesses. Thus, while networks of consumers are perhaps the most familiar examples, companies can also facilitate B-to-B and B-to-C networks. Øystein Fjeldstad has described to us the eventual migration of any value network into facilitated networks that connect individual consumers, solution shops, and value-added process businesses. Readers who wish to learn more about network businesses can also study the work of Harvard Business School professor Tom Eisenmann, which is available primarily in the form of cases and notes from Harvard Business School Publishing Company.

14. Estimate based on data from the U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of Economic Analysis. See Income and Employment by Industry, Washington, DC: Bureau of Economic Affairs, accessed from http://www.bea.gov/scb/pdf/2007/08%20August/0807_account_6.pdf on August 28, 2008. The calculation was made by combining the contributions to national income from the information, finance, insurance, real estate, rental, and leasing sectors; and fractions of wholesale trade, retail trade, transportation and warehousing, professional and business services, as well as education services, health care, and social assistance. The sum was then compared to the total national income without capital consumption adjustment.

15. Stabell, Charles B., and Øystein D. Fjeldstad, "Configuring Value for Competitive Advantage: On Chains, Shops and Networks," Strategic Management Journal, May 1998, 431.

16. Sermo at http://www.sermo.com, is a community of over 70,000 physicians, all authenticated and credentialed at the time of their registration, who exchange thoughts and opinions via online bulletin boards.

17. Some chronic diseases, particularly those less dependent on behavior modification, may be well suited for value-adding process businesses.

18. We thank Graham Pallett of Carol.com for bringing our attention to PatientsLikeMe.com. See also Goetz, Thomas, "Practicing Patients," New York Times Magazine, March 23, 2008. Careplace (http://www.careplace.com/home) was launched in 2006 and encourages users to share similar experiences and concerns by joining online communities organized by health topics and conditions.

19. This was one of the value propositions of Revolution Health, which merged its online activities with Waterfront Media in 2008. It offers online communities of blogs, forums, groups, and people with similar goals.

20. As we discuss in Chapter 5, facilitated networks have the potential to commoditize expertise and decentralize resources. Based on observations of other industries, we can expect the per-transaction cost to decrease tremendously once facilitated networks are established.

21. While Christensen's studies of disruption have focused primarily on disruptions within a type of business model, Professor Fjeldstad has taught us that disruption of shops by chains (which we call value-adding process businesses), and of chains by networks, causes a more fundamental transformation of a firm or industry's value configuration. Professor Fjeldstad's current research agenda includes understanding value configuration transformation at both the firm and the industry level. Readers interested in studying this concept more deeply should read Fjeldstad, Øystein D., and Christian Ketels, "ComØystein "Competitive Advantage and the Value Network Configuration," Long Range Planning, vol. 39, 2006, 126.

22. We explore the source of these cost reductions further in Chapter 3, when we discuss the disruption of general hospitals by focused, value-adding process hospitals.

23. The number of vessels should not even be the primary determinant of complexity in angioplasty. There is, of course, correlation between multivessel disease and risk for complications, but from a technical standpoint, a case involving one vessel should be no different from one involving four vessels.

24. Similar handoffs already exist, but only within and across solution shops like hospitals and specialty practices. For example, there are criteria and algorithms for PVOD (based on guidelines from the Inter-Society Consensus for the Management of Peripheral Artery Disease, also known as TASC) that help determine when patients should be managed by surgical bypass grafting rather than angioplasty. Of course, proper incentives need to be in place for these waves of disruption to occur. In Chapters 6 and 7 we discuss corresponding changes in the employer purchasing and insurance systems that will be necessary for such disruptions to succeed. Our thanks to Dr. Mohan Nandalur for sharing his clinical knowledge and experiences.

25. One of the coauthors of this book, Jason Hwang, works at Innosight LLC and at an affiliate called the Innosight Institute, a nonprofit organization whose purpose is to continue to develop the ideas presented in this book and to help a broad community of health-care reformers understand and implement our recommendations.