The quintessential con artist of the nineteenth century was the snake oil peddler who sold sham elixirs to vulnerable patients—and it was the specter of his parasitical existence that ultimately spawned the Food and Drug Administration.1 The FDA's essential oversight of certain elements of the health-care industry was just the beginning of regulatory influence, however. The tentacles of governmental control now stretch throughout America's health-care system in a deep, tangled, and pervasive way—to the point that health care isn't private enterprise in the sense that automobiles, semiconductors, and strategy consulting are private. Indeed, much of the current public discourse on health-care reform focuses on whether private industry can be expected to fix the current system—or whether the government will have to become even more deeply involved. In many other economically advanced countries, of course, the government is the health-care system.

In this chapter we will catalog the ways in which government policies influence health care for good and ill, and we'll recommend regulatory changes that are essential to successfully disrupting the system. To do this, we have reviewed the history of government intervention in a range of industries whose products or services have been considered "public goods"—where the public interest has been broader than what market mechanisms might be expected to serve autonomously. These include education, ground and air transportation, financial services, telecommunications, and health care. All policies can't be lumped together and treated alike, of course. But it seems that in general terms, the intent of schemes to influence and regulate these industries in the public interest evolves through three stages:

1. Subsidizing the foundation of the industry

2. Stabilizing and strengthening the companies involved, ensuring fair and equal access to their products and services, and assuring that their products are safe and effective

3. Encouraging competition to reduce prices2

We've organized most of this chapter around these three stages, because government's interaction with the health-care industry can also be grouped into these categories. Much of its energies to date have been expended in the second of these stages. In discussing those regulations, we'll show how the pattern that typified other industries is now at work in health care: regulations whose initial purpose was to protect the patient ultimately get used to protect the provider. After modeling these, we'll draw on our studies to suggest how private-sector innovators can cause policy-makers to begin focusing on the third stage—and help them distinguish the types of regulatory reforms that can predictably lead to lower costs versus those that will predictably backfire.3 Finally, we'll close the chapter by assessing whether adopting a government-led single-payer system will help or hinder the sorts of reforms we need in our system—and we'll apply those insights to the situation in other nations, where national health ministries already provide most health care.

Governments sometimes conclude that a desirable industry can not emerge on its own—so they subsidize or in other ways facilitate the investments required to cause that industry to coalesce. For example, under the Morrill Act of 1862, the federal government gave land to states that agreed to create "land grant" colleges; and under separate legislation that same year, it began giving land and cash to railroads that were willing to lay track to span the continent.4 The 1925 Kelly Act initiated airmail service, which subsidized the establishment of the scheduled passenger airline industry. The Federal Home Loan Act of 1932, the creation of the Federal Housing Administration in 1934, and the Federal National Mortgage Association in 1936, were meant to help an affordable housing industry grow.5 In 1957 the government did the same for the trucking industry, by building the Interstate Highway System.

Often, government subsidies of the cost of launching industries take the form of research and development spending. By illustration, funding of military cargo jet aircraft by the Department of Defense essentially paid for the design of the first commercial jet airliner, the Boeing 707. The research that enabled the commercial nuclear power industry was funded through military budgets—as was development of the Internet. Indirectly, through its regulation of pricing, the government "taxed" AT&T's customers to fund Bell Laboratories, whose inventions in microelectronics and telecommunications proved to be an extraordinary blessing to mankind.6

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) have funded nearly all of the basic and much of the applied research that underpins modern medicine. Much of the knowledge that took many infectious diseases into precision medicine a generation earlier, and many of the insights in molecular medicine that are driving more diseases toward precision medicine today, have been developed in our leading research universities with NIH funding.

While everything can always be improved, we propose one enhancement to the methods used to allocate NIH grants. The NIH currently uses a single-blind referee system for evaluating grant proposals. When a researcher submits a proposal requesting that a project be funded by the NIH, the NIH sends the proposal to experts in the field in question. The reviewers evaluate the proposal's potential based upon their knowledge of the field, and will recommend that it be funded, that the project be reframed and resubmitted for further consideration, or that the grant simply not be made. The reviewers' names are typically not known to the researcher who submitted the proposal. The logic behind the single-blind method is that the reviewers need to know of researchers' track records in the field. But personal relationships and politics need to be kept from the decision-making process, ensuring that each decision is made purely on the merits of the science involved.

However, the inadvertent result of this system of sending proposals for review by the scientists with the deepest expertise in the specific topic is that it has "siloized" the structure of scientific work into ever narrower disciplines and subdisciplines—in our research universities and especially in our medical schools. The referees, as the experts in their particular subdiscipline, tend to view proposals positively if they extend knowledge in their known discipline even deeper. But if the proposal intends to push knowledge in a different direction—crossing the boundary into a different scientific domain—the proposal tends not to be viewed as positively. This is in part because most reviewers aren't comfortable vouching for the scientific potential of something beyond the boundaries of their own domain, and in part because it doesn't deepen knowledge in the direction in which their work and reputation are building.7

This shaping of the enterprise of science into ever more narrow fields generally facilitates the advancement of what the great historian of science, Thomas Kuhn, calls "normal science"—the incremental block-by-block construction of bodies of understanding upon the foundation of a paradigm.8 But this specialization of knowledge and perspective flies in the face of overwhelming evidence that breakthrough insights nearly always come at new, unconventional intersections of scientific or technical disciplines. Breakthroughs rarely emerge from within individual disciplines. Rather, we get new perspectives when researchers from other fields examine old problems from their different, and novel, points of view.9 Problems that have long vexed the experts are often resolved when someone in another field sees something that the first experts simply couldn't see or didn't think to look for.10

Typically, our instinct is to look to our own discipline as the credible source for solutions—and that is the right instinct when the issue is normal science. But it is the wrong instinct when breakthroughs are needed.11 This is also why we proposed in Chapter 10 that the breakthrough structures we need in medical student education might not emerge from within our medical schools, but from corporate medical schools that might be more willing and capable of adopting principles that have already been discovered at Toyota.

There is no doubt that we need breakthroughs in health care. This means the NIH needs to create different tracks for funding, and different methods for evaluating research projects that stand astride multiple disciplines or propose tackling problems in one field through methods that have been developed in another. Projects like these can be accurately assessed and prioritized, but only by different and appropriate means.

Once an industry has been launched, governments quite often then intervene in the name of the public good to stabilize it. The intent and effect of many of these "stabilizing" regulations is to limit competition in order to help companies become strong enough to endure. The purpose of other interventions is to ensure that everyone in the population that politicians believe ought to be served by that industry is in fact served. And many regulations, of course, are written to assure that the quality of products is adequate and won't harm consumers.

As an example, 44 years after the Bell Telephone Company was founded, the Willis-Graham Act of 1921 declared telephony to be a "natural monopoly." There wasn't anything "natural" about this monopoly at all: hundreds of local phone companies and equipment manufacturers populated the industry in the early 1900s.12 But getting their mutually incompatible systems to work together had been a hellacious technological task. Willis-Graham allowed AT&T to acquire its competitors and suppliers to become completely vertically integrated—to make and manage every element of its system, from soup to nuts. Given the technological interdependencies across various pieces of equipment at the time, this integration was needed to give the company the scale and scope to make telephony reliable on a national scale.

The regulation of the securities and banking industries during the Great Depression had a similar intent. By setting prices, defining disclosure rules, regulating balance sheet leverage, requiring approval for new banks and securities firms, and mandating deposit insurance, the government limited the potential for fraud and risk-taking behavior that could damage consumers. The Interstate Commerce Commission and the Civil Aeronautics Board regulated pricing and route-by-route entry into the trucking and airline industries to avoid ruinous competition, and to assure that rural and urban consumers alike could access these services at fair prices. The Federal Aviation Administration assures passenger safety. The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration regulations that govern the crashworthiness of automobiles are likewise intended to assure our protection.

The intent of most regulation to date in the health-care industry has likewise been to stabilize and assure. The avenues of influence that the government has used to stabilize the industry and assure the availability and quality of health-care services are not dissimilar to what the financial, trucking, and airline regulators did to stabilize and assure quality and availability in their industries. The government regulates prices, licenses and certifies the people and equipment that provide the services, and determines who can and cannot enter the industry and who they must serve. In the following pages we'll describe these avenues of influence.

We stated in Chapter 7 that the formulas and methods that the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) use to set the prices of products and services constitute the most pervasive and potent regulatory controls in health care. The price at which CMS decides it will reimburse is an "anchor rate" of sorts, because most private insurers follow the lead of CMS in price-setting. This, then, determines the profitability of every product and service in health care—creating incentives for providers to sell more of what is most profitable and less of what isn't.

In a largely unintended way, the reimbursement policies of some large government payers even serve to prop price levels up by discouraging discounting in the rest of the health-care industry. For example, most states' Medicaid programs by statute pay drug companies a fixed percentage of the average wholesale price of each drug—a price that drug companies are free to set. Medicaid's reimbursement policies stipulate that at the end of each quarter, the prices paid for all of the products and services purchased must be rewritten to be as low or lower than the lowest prices offered to any other customers. This is accomplished through federally-controlled price ceilings and mandatory rebates from drug manufacturers.13

This seems like a smart deal for the government—it is the largest customer, and it ought to be guaranteed lowest prices. But consider, by illustration, its unintended, second-order effect. Suppose a chain pharmacy, which we'll call "MediQuik," negotiates a discount from a supplier of diabetes test strips, which we'll call "GluCorrect." Imagine that instead of paying GluCorrect 75 cents per strip (which would be marked up to a retail price of about a dollar per strip), MediQuik negotiates a 50-cent price, intending to pass those savings on to its customers in order to win more of the diabetes care business. But because government payers account for about 40 percent of the volume of this product, GluCorrect, in agreeing to this new discounted price, would have to cut its price to 50 cents not just for the volume it sells through MediQuik, but essentially and retrospectively cut the price to the same level on all of its government-paid business for that product—which amounts to at least 40 percent of its entire sales of those products that year. At the end of the quarter, MediQuik would be required to send to the government a check to refund the excess price that it originally charged—25 cents per strip, multiplied by the total number of strips sold to it that year.14

While this policy on the surface seems to benefit the government—assuring it of the best prices in the market—the effect is to make any discounting by the providers of drugs, devices, and services extremely expensive. Executives in every industry wish that their counterparts in competing companies had the "discipline" to act independently to maintain prices at profitable levels. The policies of Medicaid and other payers actually instill this pricing discipline in the health-care industry.15

Another class of policies for stabilization and assurance defines who does and does not have access to particular types of care. In the United States, for example, medical expenses are the leading cause of personal bankruptcy.16 Yet hospitals cannot deny life-saving treatment to the uninsured or those who cannot pay for care. America, as a result, actually already has universal health insurance, in a sense—though the present system forces people to wait until they have no other recourse but to seek care in an extraordinarily expensive hospital emergency department. Not surprisingly, many of the bills for these services go unpaid; as a result, the regulation of guaranteed access to lifesaving services imposes a much heavier burden on hospitals in lower income areas, such as rural communities and inner cities, than on those in more affluent communities.17

The bad debt that accumulates from uncompensated care isn't relieved by the Internal Revenue System, however, but through a hidden tax collected through private insurance companies from their clients. Charges to those who are insured or who can pay must be high enough to cover the cost of uncompensated care. Ultimately, the impact of this regulation that funnels the neediest and sickest into our costliest solution shops is to significantly increase costs (and human suffering) through its inadvertent second-order effects. It's ironic. America's system, which popular opinion holds excludes the uninsured and the poor from health care, actually guarantees access—albeit access that is costly to the system. In contrast, government systems that are widely viewed as granting universal access often are good at providing access to primary care and other basic services but quite stringently ration more expensive care in an exclusionary way.

There is also substantial evidence that we've framed the problem of access incorrectly. It is the marked inconvenience of finding affordable basic care that makes it inaccessible to the uninsured poor, not simply its cost. Care is often free for those who can't afford it, but only accessible to those who have the patience and fortitude to endure the indignity and inconvenience of finding it. As an illustration, MassHealth, the Medicaid program in Massachusetts, provides comprehensive health coverage for those in need. In March 2002, under pressure to reduce spending, MassHealth reduced the amount it would reimburse dentists for a range of basic dental services—and the already small pool of dentists willing to accept MassHealth patients declined even further by 15 percent. Additional free care was still available in community health centers funded by the state through a different pool of funds, but these were much less convenient to access for many of the poor. Within three years of the reimbursement cuts, 100,000 fewer MassHealth patients received dental services that were reimbursed by MassHealth.18

One option that addresses this issue is to eliminate the unfunded obligation to provide free care. This is not to say that the sick and needy should be turned away—far from it. Rather, our system of charity care needs to ensure they have equal right to convenient, quality care that doesn't threaten them with bankruptcy or force them to wait until they're much sicker before they are allowed succor. One solution is to obligate the uninsured poor to purchase high-deductible insurance on a subsidized basis. They must also be equipped with health savings accounts that can be subsidized, when necessary. But this isn't enough. Regulators must promote—and pay for, when necessary—retail clinics staffed with nurse practitioners and dental technicians, in order to stabilize and assure that a system of convenient care is available and accessible to the uninsured poor, not just to the wealthy and insured. If we uphold our moral and societal obligations to cover the cost of health care for the uninsured poor but do not simultaneously make it affordable and accessible, we have in fact provided "coverage without care."19

In addition to its power to set prices and control who has access to the goods and services of these industries, the government uses a third avenue to bring stability and assurance to health care—by approving, certifying, and licensing, and thereby determining which people and institutions can and cannot compete to provide different types of care.

The most visible form of permitting and certification is the authority of the Food and Drug Administration to approve the sale of drugs and devices. As we noted in Chapter 8, clinical trials for new drugs have traditionally been designed as a "final examination" of sorts, to see whether a drug adequately helped a sufficient portion of patients while harming them a minimal amount. If the result of a trial was that an inadequate minority of patients responded to the drug, then the drug often was not approved. The new perspective that molecular biology has given us is that when only a portion of patients respond to a therapy, it should be taken as a signal that those patients in the trial must have at least two different diseases and/or there is a genetic variation between subgroups that causes them to respond differently to the therapy. Clinical trials in the future therefore need to be managed not as one-off tests, but as research trials whose purpose is to assist the researchers in defining and diagnosing diseases more precisely.

In addition, clinical trials historically have been organized around diseases that were defined and diagnosed by observable physical symptoms in particular organs or locations in the body. As we explained in Chapter 2, it turns out that these categorizations sometimes run orthogonally to the true nature of the diseases being treated. The organization of clinical trials needs to adapt to changing and increasingly precise definitions of disease, so it is the efficacy of the drug in treating the underlying cause that is being tested, and not simply the extent to which the drug ameliorates a symptom that happens to be correlated.

In our opinion, the FDA has made significant progress already in designing new "fast track" processes for evaluating drugs, such as its Critical Path Initiative. These newer research programs and trials tend to incorporate biomarkers as end points, pursue drug-diagnostic codevelopment, enrich patient populations by first diagnosing them as precisely as possible, utilize bioinformatics, and retain specimens for future testing and analysis should the understanding of disease change.20 There remains, of course, much to do.

The FAA doesn't just certify new aircraft as being safe to fly after they've been designed and built. They certify pilots as having been thoroughly trained to operate them, and they certify facilities as being equipped to handle aircraft of various types. In the same way, governments don't just certify drugs and devices. They also certify people and places.

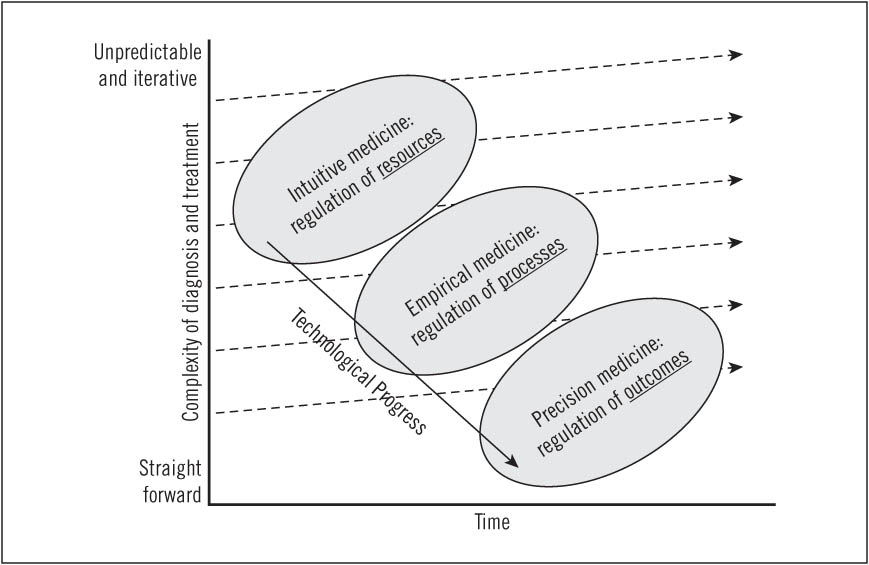

Because the nature of the technology available affects the skill required to use it, the fact that scientific progress pushes care from intuitive toward precision medicine demands different regulatory emphases over time, as illustrated in Figure 11.1. When a disease can only be treated through intuitive medicine, the inputs or resources used in the caregiving process are the critical points of assurance control. In this situation it is primarily the training and qualifications of the physicians that must be assured.

Over time, however, greater understanding and predictability arise from the cycles of qualified physicians repeatedly working together to deliver outcomes in solution shops. Processes coalesce that embody the best of what has been learned about how to approach various diseases. A lot of know-how gets embodied in equipment and drugs. These mechanisms draw treatment into empirical medicine—where we can't guarantee the result, but can assert the probability of achieving a desired outcome if a particular therapeutic process is followed, using particular drugs or devices. When this happens, the emphasis of regulation needs to shift from a focus on the inputs and resources used, to a focus on the process used—to ensure that the best demonstrated practices are employed. This is what happens when an association of medical specialists or a hospital system proclaims new guidelines and standards of care for a certain condition, or an insurer declares that it will only reimburse if a specific procedure is followed. These are all regulations that govern process.

FIGURE 11.1 Matching regulations with the changing nature of medical practice

Often, the training of the professionals who provide care within these processes does not need to be as extensive as was formerly required in the regime of intuitive medicine. As regulators shift focus to process, therefore, they must simultaneously revisit their regulation of resources—because often caregivers with less training can do the job perfectly well.

When improved understanding has further shifted care into precision medicine, the focus of regulation needs to evolve again, toward a focus on outcomes, rather than on resources or processes. And because outcomes are predictable at this stage, regulators should focus on ensuring transparency and reporting relevant data from all providers. Regulating adherence to previously established standards for inputs and processes becomes less relevant, because competitive success typically compels adherence to these standards.

Many who have written about health-care reform urge in an undifferentiated way for transparency—for disclosure of outcomes data for individual hospitals and physicians. We have concluded that a key reason why such transparency hasn't emerged is that what these reformers have urged is not just overly simplistic: it is an impossible apples and oranges problem. For care of diseases in the realm of intuitive medicine that is provided in solution shops, the outcome is a diagnosis. But when care is provided in value-adding process clinics for diseases in precision medicine, the outcome is a cure. It is the latter in which outcomes data must be transparent and comparable. It comes as no surprise to us then that many physicians oppose the idea of pay-for-performance initiatives, often stating that their incentives are tied to processes and decisions beyond their control. This opposition arises not because they are opposed to quality care, but because a pay-for-performance system that attempts to encourage specific outcomes can only be effective for care that is fully in the realm of precision medicine.21

Regulatory insistence on compliance to inputs and process standards eventually can become a hindrance to further innovation if a pioneering company could potentially figure out a way to deliver superior outcomes by deviating from convention. A great example of an appropriate response to changing technology of this sort is in the FAA regulation that there must be an FAA-certified pilot and copilot in the cockpit for each commercial flight. The avionics on these aircraft and in control centers are now so sophisticated and comprehensive that much of the navigation, ground-air-ground communication, and piloting work is performed by computers, not pilots.22 These advances are sophisticated and reliable enough that just a single pilot is needed at the controls. In the new microjets produced by Eclipse Aviation, Spectrum Aeronautical, and others for the emerging air taxi industry, the FAA no longer requires a copilot. There isn't even room for one.

Those who resist regulatory reforms such as these in health care have frequently told us, "Yeah, but it's lives that are at stake in health care." To which we reply, "You're right, and it is lives that are at stake on these planes too." Indeed, as the aviation regulations have shifted in emphasis to equipment, processes, and outcomes, the safety record of the technology is proving better than that of pilots.23

We are not calling for wholesale deregulation of the health-care industry. Indeed, history has shown that when competitive markets can't create an industry that functions for the public good, regulation for stability and assurance has always been critical at a particular stage.

The dark side of this necessity for regulation, however, is that rules survive long after the public need for stability and assurance have been satisfied by technological progress. While the original intent of permitting and certification is a genuine concern for the patient, almost always the rules then come to be used to protect the economic interests of the providers—still invoked, of course, in the name of the patient, or of the passenger, or of the "public good." If regulators do not evolve the focus of their rules as science and technology progress, they will trap care in high-cost business models whose outcomes are less predictable, and are actually not as good as those that might otherwise be developed by innovators. Regulators must keep their vigil and adapt the focus and nature of the regulations to evolutions in medical practices, processes, and technology—but they rarely do.

For example, the Civil Aeronautics Board effectively "stabilized" the airline industry from the 1930s through 1977 by limiting the number and type of airlines that could fly on any given route, and by setting the fares they could charge. The Securities and Exchange Commission similarly "stabilized" the Wall Street brokerage firms as they emerged from the chaos of the Great Depression, by allowing the New York Stock Exchange to set at a profitable level the fees its member firms would charge to execute a trade. When Southwest Airlines and Charles Schwab sought approval in the 1970s to compete with the established firms in their respective industries through discount pricing, the lawyers for the established firms mounted eloquent arguments for why, in the name of the public good, the discounters should not be allowed to enter the market. Fortunately, they were allowed.

In a similar way, health-care providers regularly fall back on stability and assurance regulations to block competition. For example, in 2003, at the urging of the hospital industry, Congress imposed a nationwide moratorium on the construction of specialty hospitals such as heart and orthopedic hospitals. The argument was that in the event that a patient undergoing a cardiac bypass procedure suffered a stroke, for example, you needed to have within the hospital the ability to treat stroke, not just to repair hearts or replace hips. For the good of the patient, they claimed, all care needed to be delivered in general hospitals. It is interesting that the general hospitals have never militated to ban specialty psychiatric hospitals, even though, surely, patients in psychiatric hospitals on occasion have heart attacks, strokes, and hypoglycemia. Certainly, for the good of the patients, those with mental disorders also should be cared for in general hospitals. The reason for general hospitals' schizophrenic concern about heart and orthopedic hospitals but not psychiatric ones, of course, is that the procedures siphoned off by the former two are highly profitable, and psychiatric patients typically are far less profitable (and usually unprofitable). The actual reason for the 2003 ban was that these specialty hospitals could perform some of the general hospitals' most profitable procedures, but at much lower cost.24

As another example, out of concern for patient safety, many states still prohibit nurse practitioners from writing prescriptions without the direct supervision of a doctor, even for precisely diagnosable, rules-based disorders like strep throat. This effectively prevents retail clinics from competing against physicians' practices in those states—even though in the other states the patients are doing just fine, at less than half the cost. Worse still, patients who may not be able to afford the rates of physicians' practices or who do not have access to a primary care physician but might be able to afford a visit to MinuteClinic get shut out altogether—in the name of patient safety.25

Because assurance-oriented regulations initially limit rights of practice to those with the required expertise, a paternalistic culture often emerges in regulated industries that is built around the belief—validated at the outset—that people can't be expected to care for their own needs. This was the defense raised against discount and on-line brokerage firms. It is the fabric of the regulatory culture in legal services that to date has stymied disruption of that industry. And it pervades the defenses of the status quo in health care as well. In the realms of empirical and precision medicine people can actually competently assume responsibility for a growing portion of their care. This is a key reason for our call in Chapter 5 that patients with diseases in the "Chronic Quadrangle" be financially affected by their adherence to therapy. This is a critical change that regulators must allow. These diseases are decidedly in an empirical, rather than intuitive mode. We are no longer in the realm where paternalism is appropriate.

Many of the activities of certification, licensing, and permitting in health care are actually administered by trade or professional associations in the private sector, as well as by universities and various nonprofit organizations. The actions of these entities are given teeth when the ability to get paid for something—by Medicare or by private insurers—is tied to being credentialed. Among the best known and most influential agencies are the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Hospitals, which certifies hospitals for compliance with federal regulations and whose accreditation is required for Medicare reimbursement; the National Board of Medical Examiners, which tests the capabilities of medical school graduates and whose assessment is required for medical licensure; and the members of the American Board of Medical Specialties, which evaluates physicians in areas of specialty care and whose certification is necessary for physicians to be hired or credentialed by most hospital systems.

When Medicare or insurance companies follow a policy of paying only for services provided by licensed professionals, they can block disruptive innovations. There are many examples where technology has progressed to the point that procedures can be performed in clinics instead of hospitals, or by nurse practitioners instead of doctors, resulting in outcomes that are as good or better. Yet the rule of reimbursing only for services provided by certified caregivers makes it impossible or unprofitable to hand off care to lower-cost disruptive providers, because changes in certification typically lag many years behind changes in technology.

When governments are democratic rather than autocratic, the entities that profit from the status quo typically have many more means of influencing elected and appointed officials to preserve the present system, compared to the more meager resources of disruptive entrants who petition to shift the focus of obsolete regulations away from resources like professionals and institutions and toward processes and outcomes instead. The $450 million the health-care industry spent in lobbying efforts with the government in 2007, in fact, exceeded spending to influence government policy by the finance, insurance and real estate, telecommunications and electronics, and energy and natural resources industries.26

The result of this massive imbalance of resources on the side of those resisting reform, based upon our studies, is that the reformers almost always lose head-on battles to deregulate what is regulated. Would-be disruptors who have directly petitioned the authorities to change regulation are left waiting on the sidelines for the regulation to one day change by fiat, or have simply abandoned their disruptive ideas. On the other hand, those disruptors that successfully dismantled the regulations that stood in their way succeeded by circumventing the regulation—by innovating in a disruptive market that was beyond the regulators' reach or was peripheral to their vision. Regulations ultimately change in reaction to the innovators' success in those markets—they rarely change to enable disruptive success.

For example, until 1980 Regulation Q profoundly shaped the structure and nature of competition in the consumer banking industry. It dictated that banks could not pay interest on checking accounts and capped the interest rates commercial banks and savings and loan associations could pay on savings deposits at 5.25 and 5.5 percent, respectively.27 These regulations were broken when Merrill Lynch offered a cash management account that allowed customers to write checks against a "money market fund," and whose assets were short-term government securities that yielded more attractive interest rates. Fidelity quickly joined Merrill Lynch in offering interest-bearing checking accounts. Because they weren't banks and operated only on the periphery of bank regulators' vision, Merrill Lynch and Fidelity didn't attract the scrutiny that banks drew when they sought permission to pay interest on checking accounts. The disruptive Merrill Lynch and Fidelity products drew such enormous volumes of assets out of the conventional banks that ultimately the Federal Reserve had to change its regulations in response. Aggressive banks and consumer groups had lobbied for years to change these regulations from within the dominant value network, and they failed. It was the creation of a new disruptive value network, and the pulling of customers into it, that brought regulatory change.

As another example, until 1978 the Civil Aeronautics Board regulated the routes that airlines could fly and the prices they could charge. In 1971, Southwest Airlines began flying short routes within the state of Texas at very low prices, competing as a new-market disruptor to the major airlines by serving people who previously couldn't afford to travel by airplane. Because Southwest did not offer interstate travel, its routes and fares could not be regulated by the CAB. Furthermore, Southwest steered clear of the main DFW airport in Dallas, electing instead to fly in and out of the smaller, older, Love Field—where there were no established competitors. Southwest gradually started a few cross-border flights to adjacent states, but it minimized the opposition of established carriers by shuttling between smaller airports that weren't the bread and butter of the major airlines. By 1978 it became clear that the safety of discount airlines was just as good as—and the pricing for consumers significantly better than—what major airlines had been offering. So the CAB deregulated the airline industry. But once again, deregulation did not come from a direct appeal to the regulators.28

Note that in the earlier example of the virtual copilot in the minijets of Spectrum Aeronautical and Eclipse Aviation, even though similar avionics had long ago automated control on major aircraft, the mainstream pilots' union would have fought elimination of a required copilot to the death. But by going where they aren't—where the alternative is no pilots flying at all—the pilots and their passengers are delighted to see the regulation changed. Little by little, as Eclipse and Spectrum move up-market into bigger planes and grow from selling hundreds to thousands every year, the need for a copilot will be obviated.

And we see the same pattern in those few instances where the focus of health-care regulation has changed: you have to start where they aren't.

Consider this illustration. Despite the fact that it is preventable, tooth decay, the chronic disease that leads to most tooth loss, is present in over a quarter of all children between ages two and five, over half of all children between ages 12 and 15, and 90 percent of all adults over age 40.29 Tooth decay plagues 5 billion people worldwide, disproportionately affecting low-income households. It accounts for 10 percent of all health costs in industrialized nations.30 There must be an opportunity for disruptive innovation to address this global public health concern.

There is. But for the good of the patients, it's having a hard time getting to those who need it. Consider what's happening in Massachusetts as an illustration of how, when attacked directly, regulations get morphed to defend the professionals, not the patients.

Dental hygienists have been promoting legislation to allow specially trained hygienists to clean teeth and apply fluoride without direct supervision by a dentist.31 The Massachusetts Dental Society has vociferously opposed this, citing concerns for public safety. But the MDS has proposed an alternative—the creation of a different class of specially trained dental assistants who could clean teeth and even place fillings under direct supervision by a dentist.32 The Massachusetts Dental Hygienists' Association (MDHA) then voiced its opposition, concerned about how the introduction of dental assistants might "squeeze out more qualified registered dental hygienists."33 All evidence points to a long battle in Massachusetts over these direct disruptive attacks. Organizations and professions will predictably fight to protect their livelihood.

Yet where fewer people are looking, dentistry is being disrupted. In 2000, to address the lack of dental services in rural areas,34 the Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium (ANTHC) persuaded the state to create a new type of dental provider called a dental health aide therapist (DHAT).35 The model had been implemented in New Zealand over 90 years ago with demonstrable success, and similar programs existed in 42 other countries, including Canada and the United Kingdom.36 In fact, the first Alaskan students to train in dental therapy went to the School of Dentistry at the University of Otago in New Zealand, since no such program was available in the United States. DHATs train for two years, instead of the minimum of four that dentists train, and at $60,000 per year, they make about one-third the salary of a typical dentist.

Since 2003, DHATs in rural Alaska have been providing services such as cleaning, drilling, filling, and extraction with only indirect supervision via periodic case reviews. Today, 10 DHATs serve 20 villages in Alaska—places that previously received dental care only one or two weeks each year from a visiting dentist. In 2005 a quality assessment by a professor of dentistry from the University of Washington School of Dentistry reported:

During my four-day site visit to the dental clinics at Bethel, Buckland, and Shungnak, I evaluated the clinical performance of the four dental therapists who have been providing primary care for Alaska Natives since the beginning of 2005. In every respect their performance met the standard of care I had established. Their basic training and subsequent preceptorships have produced competent providers. Each is equipped not only to provide essential preventive services but simple treatments involving irreversible dental procedures such as fillings and extractions. Their patient management skills surpass the standard of care. They know the limits of their scope of practice and at no time demonstrated any willingness to exceed them. On multiple occasions they demonstrated their ability to recognize and avoid clinical situations that might pose a threat to patient safety. My firsthand observations convince me that statements by dentists and dental societies suggesting that dental therapists cannot be trained to provide competent and safe primary care for Alaska Natives are overstated.37

The American Dental Association and Alaska Dental Society have predictably opposed allowing DHATs to provide unsupervised dental services, requesting an injunction from the Alaska Superior Court in 2006 to block their encroachment.38 The judge ruled in favor of the ANTHC, stating that "a significant number of the enumerated health objectives . . . would continue to go unmet if the Alaska State Board of Examiners were placed in charge of dental health for Alaska Natives located in rural areas."39 We expect that DHATs will soon be allowed in rural areas in the lower 48 states of America, where the population is not being well served by dentists. Eventually, the disruption will arrive in Massachusetts. But the shortest distance between two points is not a straight line.40

Over the past decade, there has been significant growth in the use of teleradiology, beginning with off-hours, or "nighthawk," radiology services, which allow hospitals to transmit digital images to anywhere in the world for interpretation. Even if the patient arrives in the dead of night, the radiographs can be interpreted within minutes by a radiologist at another center in the United States, or even in Australia, India, or France. This implementation of teleradiology has enabled hospitals to maintain reliable and efficient services around-the-clock and to meet the exploding demand for CT scans (growing at 14 percent annually) and other imaging studies, despite much slower growth in the number of radiologists.41 The largest of these off-hours radiology providers, Idaho-based NightHawk Radiology Services, serves 26 percent of all U.S. hospitals.42

Teleradiology services began by targeting nonconsumption—radiologists gladly allowed the new services to manage their less desirable time slots on nights and weekends. However, once they began to offer daytime services, there was predictable opposition from radiologists. Leaders of the American College of Radiology raised concerns about ensuring the quality, accuracy, and accountability of personnel based in another state or country.43 There were also concerns about communication problems when the radiologist and referring physician were so far apart. In 2002 an attempt by Massachusetts General Hospital to partner with a nonprofit company in India to shift some of its radiology work to Indian doctors resulted in hate mail and ultimate failure for the venture.44 Legislators got involved, claiming that patient privacy was at risk, and placed restrictions on transferring patient data abroad.

In response to this reinforcement of the intuition-era regulatory focus on the doctor's qualifications, most teleradiology services, even if located abroad, have been compelled to employ only U.S.-trained and -licensed radiologists, who must also be credentialed at the hospitals for which they perform services.45 Furthermore, their interpretations are often considered only preliminary until reviewed, or "overread" by a U.S.-based radiologist. The Joint Commission on Accreditation of Health Care Organizations also weighed in to require teleradiology services to meet licensing and accreditation standards that have long been in place for hospital-based solution shops of radiologists.46 The result: a typical NightHawk radiologist has licenses in 38 states and is credentialed at over 400 hospitals. The company employs 35 to 40 people simply to manage all of this administrative overhead—and yet can still provide these services at lower cost than most of its customers can when they choose to perform them in-house.47

However, a funny thing is happening at the edge of this stalemate. A growing segment of work is no longer dependent on a radiologist's expert eye and clinical experience to interpret shadowy anatomical structures and link them to patients' clinical histories and physical symptoms.48 "Functional" radiology, involving dynamic in-motion studies and molecular tracers rather than still pictures, and "quantitative" radiology—a related discipline based on measurements and scoring algorithms—have significantly enhanced the ability of nonradiologist physicians to elucidate physiologic abnormalities.49 Starting with basic technologies like ultrasound and fluoroscopy, these machines automate image acquisition and analysis, embedding into algorithms some of the diagnostic skill that used to reside only in the intuition of radiologists. These machines also require less space, shielding, and power, so they can be integrated into the offices of cardiologists and orthopedic surgeons working in value-adding process clinics.50

The door was opened, in typical disruptive fashion, to nonradiologist physicians to begin performing and interpreting some of the simpler studies for themselves, and they are referring fewer and fewer patients to the radiology solution shops of the local hospital. So while radiologists were trying to figure out how to prevent the loss of work overseas, other physicians were beginning to perform some of that work for themselves within their very same offices and communities.

An important insight from this end run around regulation is that the cardiologists and orthopedic surgeons didn't need to seek regulatory approval. Radiologists make their money on a fee-for-service basis by interpreting images ordered by other physicians. Teleradiologists have been attempting a low-end disruption into this business—using a lower-cost business model to capture segments of the market—but still on a fee-for-service basis. The cardiologists and orthopedists working in capitation or fee-for-outcome models didn't need to worry about regulatory approval because they don't make their money interpreting images—they make it by repairing hearts and bones. Radiology simply helps them repair more hearts and joints better and faster.51

We suspect that after a few years of cardiologists, orthopedic surgeons, and others using these computer-assisted imaging technologies with results comparable to those of radiologists, regulations will eventually change to focus on processes and outcomes, rather than on the credentials of the physicians. Already, in fact, the initial fears about the safety of outsourcing radiology services to off-hours providers now seem unfounded.52 The time will even come when point-of-care doctors won't need a radiologist as a copilot.53

Lao-Tzu framed the deregulation strategy of "Starting where they aren't" better than we have when he wrote, "Water is fluid, soft, and yielding. But water will wear away rock, which is rigid and cannot yield. As a rule, whatever is fluid, soft, and yielding will overcome whatever is rigid and hard. This is another paradox: What is soft is strong."54

When stability and quality have become assured, governments often then shift their focus toward the third stage of government influence—to regulations that improve the affordability and convenience of the products and services in question. This can be achieved by deregulation, or the unwinding of restrictions on price-cutting and entry, that had been put in place when stabilization and assurance were paramount concerns. Antitrust action is another weapon used in the pursuit of competitiveness and efficiency.

Economists and economists-turned-deregulators have habitually employed a standard and simplistic formula for cost-reduction: ↑ competition = ↓ prices. Their simple creed is that in the absence of competition, companies will charge monopolists' prices. If you intensify competition it will drive prices down. It turns out that the hoped-for good news of this gospel often doesn't materialize. When deregulation or antitrust action pits new entrants against the established industry leaders from the regulated era in sustaining competition, it typically results in an enormous waste of resources and little impact on prices, because the entrants fail. It is disruptive competition that yields dramatic reduction in price and improved accessibility. The implication is that deregulators need to focus not simply on enabling competition—but on facilitating disruptive competition.55 When regulators don't get this formula right, history has shown time and again that the results can be catastrophic. Let's look at three such cases, the scenarios of which are summarized at the end of the following section, in Figure 11.2.

In the 1960s, IBM dominated the market for mainframe computers. It enjoyed a 70 percent market share, but captured about 95 percent of the industry's profit. This near-monopoly of course bothered the United States Department of Justice, and so in 1968 the DOJ sued to break up IBM into a set of smaller companies in the belief that more intense competition amongst mainframe computer makers would reduce the cost of computing. For 13 years the government spent hundreds of millions of dollars prosecuting this lawsuit, and IBM spent hundreds of millions defending itself.

While the lawyers were working on this problem, the disruptive minicomputer and personal computer value networks were emerging. As these ecosystems grew, they pulled more and more customers and applications from the mainframe value network in the back plane of the disruption diagram into the disruptive networks in the front. One day one of the lawyers noticed, "Hey! There aren't many customers back here using these mainframes! They're out there computing on those microprocessor-based machines!" So they closed their briefcases and went home. IBM's mainframe monopoly indeed had been broken—but not by the Justice Department. It was broken through disruption.

We invite our readers to pause at this point, boot up their notebook computers, and reflect on two historical possibilities. What impact would breaking up IBM's mainframe monopoly—in order to create more competition among mainframe providers—have had on the cost, availability, and quality of computing? How does that compare with the impact that disruption has had on these three variables? It's a great way to visualize how important it is for regulators and the economists who advise them to differentiate between sustaining and disruptive competition.

By the late 1990s an even more dominant near-monopolist named Microsoft had emerged in the personal computer operating system business. Its market share exceeded 90 percent, and the company was making extraordinary profits. This of course bothered the United States Department of Justice deeply, and so in May 1998 it sued to break up Microsoft in the belief that more intense competition among operating system and Internet browser vendors would reduce the cost of computing. The government spent hundreds of millions of dollars prosecuting this lawsuit, and Microsoft spent comparable sums defending itself. A decree in 2001 signaled that Microsoft had survived the first attack of the Justice Department.

While the DOJ's Antitrust Division is figuring out its next steps, a new disruptive value network is emerging in a new plane of competition. While it has many names, we'll call it Internet-centric computing. It is disrupting the enterprise-centric computer networks within which most of us have been computing during the last decade. Linux has become the operating system of choice in Web servers, and firms like Google, Yahoo, and Amazon have built their systems upon Linux. As these Internet-centric services are becoming faster, more convenient, secure, and reliable, more and more applications are being drawn out of the enterprise network in the back plane of the disruption diagram, into the Internet-centric value network in the front—customer by customer, application by application, from searching for documents on our hard drives to searching for them on the Internet.

One day soon some antitrust lawyer will notice that the government's latest legal briefs had been composed on GoogleDocs, not Microsoft Word, and will send out the message, "Hey! There aren't many customers left here using these enterprise networks! They're all out there computing on those Web servers!" They will then close their briefcases and go home. Microsoft's monopoly will indeed have been broken—but not by the Justice Department. It will have been broken through disruption.

In the Telecommunications Deregulation Act of 1996, the United States government again attempted to enhance affordability and accessibility with the same naive theory—that competition per se will drive costs down. To promote competition, the act required that the independent local exchange carriers—also known as ILECs, comprising US West, Pacific Bell, Bell South, Ameritech, Southwestern Bell, and Bell Atlantic—share their networks with new entrants at discounted, regulated rates. These entrants, called competitive local exchange carriers (CLECs), were invited to create competition over the "last mile" to customers' homes and offices, and then "plug in" to the established ILECs' local networks that interfaced with long-distance networks. The hope was that a large barrier to entry—the creation of the physical "local loop" of communications lines and switches—could be circumvented by utilizing existing networks, thereby promoting competition in local telephone service that would hopefully result in lower rates for consumers.

Close to 300 CLECs garnered more than $300 billion in funding from venture capitalists and Wall Street, entering the markets of over 100 cities. By 2002 only 70 CLECs remained, and by 2007 nearly all of them were gone. High fliers like WinStar, Covad, NorthPoint, Rhythms, and Teligent all went bankrupt.56 The sector became a poster child for the dot-com bubble burst. Indeed, rather than spurring more competition and lowering prices, a wave of industry consolidation occurred, and pricing for local telephone service remained high.

What happened? By enticing new entrants to use the prevailing business model, based on the existing local communications infrastructure, the regulators essentially pitted the start-up CLECs into head-on, sustaining-innovation competition against the ILECs on their home turf. Again, our research on innovation has shown overwhelmingly that when entrant companies attack incumbent leaders with a sustaining innovation, using a similar business model in the leaders' existing markets, the leaders invariably triumph. And they did.

While the regulators and their lawyers and economists have been using head-on sustaining competition as their tool for making telecommunications services more affordable and pervasively accessible, disruptive business models already are booming in a new disruptive plane of competition—without the subsidy of government. Using Voice over Internet Protocol (VoIP), Skype, to name just one example, is now one of the largest telephony providers in the world, with more than 350 million users. Its premium service offers unlimited local and long-distance calling starting at $35.40 per year—and its customers take their telephone numbers with them wherever they go in the world.57 And we are only beginning to see the revolution in affordability and accessibility that will come with wireless VoIP and video over the Internet.58 Meanwhile, in the rearmost plane of competition in the disruption diagram, the network companies and cable companies are engaged in multi-billion-dollar competitive battles of sustaining innovation, each striving to bring higher-definition television and more reliable wire-line telephony at higher prices to their most attractive customers in "Triple Play" bundled pricing.

The importance of applying the model of disruptive innovation to the challenge of improving the cost and accessibility of health-care services is presaged by Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer's opinion after the 1996 Telecommunications Act was challenged by a number of telephone carriers. Breyer offered an apt postmortem of the entire debacle: "It is in the unshared, not in the shared, portions of the enterprise that meaningful competition would likely emerge. Rules that force firms to share every resource or element of a business would create, not competition, but pervasive regulation, for the regulators, not the marketplace, would set the relevant terms."59

FIGURE 11.2 Patterns in the impact of regulation versus disruption in making services affordable and accessible

We could recount in detail for deregulators how air travel, trucking, stock brokerage, and many more regulated products and services have become significantly more affordable not by introducing head-on sustaining competition, but through disruption. The topic deserves a book in itself. Suffice it to say that there is a pattern here. Regulators and deregulators have not once—not once—brought significantly lower costs and better access by demanding enhanced competition among the established practitioners of existing business models. When regulations that were put in place to stabilize and assure subsequently need to be relaxed and refocused, significant improvements in cost and access have only come from disruptive business model innovation. When we read simplistic, undifferentiated calls for more competition, we all ought to invoke Yogi Berra's immortal phrase: "It's déjà vu all over again."60

In the decade over which we conducted the research that we tried to distill into this book, we've noted a growing sense of despair among doctors and executives about the counterproductive roles that Medicare policies play in the overall American health-care industry. Medicare has become so massive, the refrain goes, that it simply cannot be changed. We believe that Medicare can be transformed into a neutral force in the industry—still able to fulfill its mission of providing care to the elderly, yet not inhibiting innovation that can help everyone. This can be done by following the same rules: We need to initiate change in portions of the industry that are beyond Medicare's reach, rather than trying to change Medicare directly. And we need to control the ballooning costs of Medicare through regulatory change that enables or facilitates disruptive business models.

How does one create a value network beyond the reach of Medicare pricing mechanisms that create such powerful distortions in U.S. health care? One way is to internalize the market within the major integrated provider systems described in Chapter 6, where members pay a fixed annual fee for the health services they receive.

If organizations like Kaiser Permanente, Intermountain Health-care, and Geisinger Health System create focused and disruptive business models appropriate for the different categories of disease, they can internally make decisions and direct patient care based upon efficacy and economics, not in response to distorting regulations on reimbursement.61 As these delivery systems prove their efficacy and cost advantage, then one by one, patients can be drawn from the original plane of competition—where independent suppliers apply for Medicare reimbursement on a fee-for-service basis—into a new disruptive one. Ultimately, Medicare would assist its covered population in the payment of annual fees associated with care in the integrated fixed-fee provider system. Importantly, the fixed annual fee would be the only price that Medicare would be concerned with—and it would be a negotiated price between the payer and provider. Other prices would be set between vendors of drugs, devices, and services, and the integrated entities that buy from them, on a competitive basis.

In many respects the United States, with its hybrid public-private system, has a leg up in health-care reform over those democratic countries without a substantial private system. When the government is everywhere, innovators can't go where the regulators aren't, in order to initiate disruption. Reformers in those nations must tackle the system head-on—which, as the final section below will show, is a fight we wouldn't wish for our worst enemies.

Our claim at the beginning of this chapter that "the tentacles of governmental influence and control stretch throughout America's health-care system in a deep, tangled, and pervasive way," actually might have been an understatement. CMS typically sets the anchor rates for medical reimbursement, which private insurers then follow. The NIH and FDA are essentially make-or-break supporters and gatekeepers for innovations in biomedical research and new technologies. Other institutions, including the Veterans Health Administration, Indian Health Service, and an extensive network of federally funded and state-funded public health centers, deliver care.

Given the pervasive influence of all these agencies, one might reason whether the government itself might be the only entity with the power and scope to solve the health-care crisis. In fact, nearly every decade brings a renewed push for the United States to emulate the system used by most industrialized nations—a government-sponsored, single-payer nationalized system.

The critical challenge we actually face is not how to pay for health care. Nobel laureate Milton Friedman long ago assured us that there is no such thing as a free lunch. Whether the check is written by individuals, employers, or government-run health-care systems, in the end it comes from the pockets of the people.

A second question of some import is whether to pay for health care. Overwhelmingly, American employers have chosen to pay for it. A key reason why health care accounts for a smaller share of Gross Domestic Product in other developed nations is that their governments have chosen not to pay for it: Almost every government with nationalized health care has been forced to ration access to advanced care in one way or another. The straits in which Canada's public, paid-for system finds itself, for example, prompted Chief Justice Beverly McLachlin of the Supreme Court of Canada to opine in 2005 that "access to a waiting list is not access to health care."62 As a result, most countries with national health systems have had to develop alternative market-based channels for coverage as well—so people can choose for themselves whether to pay for certain services, rather than leaving that choice to bureaucrats.63

Government health systems in general do a better job not just of rationing, but also of controlling the salaries earned by doctors and nurses, because governments essentially are the only employers for most of those who pursue health-care careers—and monopsonistic purchasers have the power to dictate the prices they will pay.64 Because of governments' tight control on caregivers' salaries, in many nations the best physicians establish themselves in private practice, where they can earn higher incomes by serving the wealthy. This is another paradox of national health systems: while the intent is to assure universal access, often it is the elite who see the elite, while the rest see the rest.65

Hence we come to the focus of this book: how to make health care affordable. We hope our readers are convinced by now that it is the business model within which the professionals work that is the major driver of cost, not just in health care, but in every industry. National health systems have not done a better job than America's system of making health-care costs affordable through disruptive business model innovation. Both, to date, have done poorly.

We believe that despite all the roadblocks we expect disruptive innovators to encounter in America, however, a decade from now disruptive reformers within America's system will prove to have been much more successful at making care more affordable and accessible than will those in most nationalized health systems. We therefore urge America's political leaders not to view further government control as a vehicle for solving our problems. Rather, it is time for America's government to foster disruption.

Most government health ministries are comprised of decentralized fiefdoms. Hospitals are administered independently of the physicians' organizations, which are administered independently of the drug pricing and distribution system, and so on. Though the administrators are civil servants and the doctors are employed by the ministry of health, these systems are not different in their basic administrative structure from the non-integrated system that characterizes most of the United States health-care industry. Those few public health ministries with a high degree of centralized, coordinative control, such as in Singapore and the United Kingdom, resemble in their structure the integrated providers like Kaiser Permanente, which we discussed earlier. In other words, the centralization of the power to orchestrate change is what is critical—and that power can be vested in either a government ministry or a private provider.66 Most government health ministries are actually quite powerless to implement significant changes, because the political process of convincing the separate entities to fall in line in the new disruptive direction would stymie all semblance of reform.

To explain why the power to orchestrate is so critical, we'll draw on a final model from our research on innovation, which we call the "Tools of Cooperation." The essence of this model is that having the right vision for where your company (or a ministry of health) needs to go is just the start. Once you know the necessary future direction, you then need to convince all the other people and entities whose resources and energies are required to succeed in that journey to cooperatively work together to get there.

The effectiveness of the various tools that might be wielded to elicit this cooperation depends upon the extent of preexisting agreement along two dimensions. The first is the extent to which the people involved agree on what they want—the results they seek, what their priorities are, and which trade-offs they're willing to make to achieve those results. The second is the extent to which they agree with each other on which actions will yield the desired result.

For those who must manage change, there is no "best" position along these two dimensions of preexisting agreement. The key is recognizing the extent of agreement and then selecting the tools of cooperation that will work most effectively in that situation. We believe this simple model applies to units as small as families, to business units and corporations, to school districts, and even to nations.

Figure 11.3 maps these dimensions of agreement in a matrix, and describes the types of tools managers can wield in different situations, in order to elicit cooperation among the stakeholders to work in concert in achieving the needed change. The boundaries delineating the domains in which the various tools can work are not rigid, but the broad labels can give leaders a sense of which tools are likely to be more or less effective in various situations.

FIGURE 11.3 Four types of cooperation tools

When there are sharp disagreements among the concerned parties about what they want and how to get it, the only tools that will elicit cooperation in pursuit of a new course are "power tools" such as fiat, force, coercion, and threats. This is how Marshal Tito brought peace to the Balkan Peninsula, for example. After World War II, he herded the disparate and antagonistic ethnic groups in that region into a more or less artificial nation and said, in essence, "I don't care if you agree with me or with each other on what you want out of life or how to get it. I just want you to look down the barrel of this gun and cooperate with me and each other." It worked.

Tools such as negotiation, strategic planning, and financial incentives don't work well in situations of minimal agreement. As depicted in Figure 11.3, these will work only when there is a modicum of agreement on both dimensions of the matrix. In environments of antagonistic disagreement—whether in the Middle East or in the infamous clashes between the management of Eastern Airlines and its machinist union—negotiation does not work. A leader might use strategic planning to figure out where the organization ought to go next, but lacking some agreement on both dimensions, the strategic plan itself will not elicit the cooperative behavior required to get there. And financial incentives—essentially paying others to want what you want—typically backfire in a low-consensus environment. People will react indifferently, because they do not agree with the incentives' goals.

Only power tools are reliably effective in low-agreement situations. The key is having the authority to use them. In democracies, many of these mechanisms are outlawed. This hamstrings public-sector executives who face a mandate for change with little power to do what needs to be done. We will return to this point later.

The tools that elicit cooperation in the lower-right region of the agreement matrix of Figure 11.3 are coordinative and process-oriented in nature. We call these "Management Tools," and they include training, standard operating procedures, and measurement systems. For such tools to work, group members need not agree on what they want from their participation in the enterprise, but they must agree on cause and effect.

For instance, in many companies, unionized manufacturing workers come to work for different reasons from those of senior marketing managers. But if both groups agree that following new manufacturing procedures will result in better levels of quality and cost, they will cooperate. If there is no consensus among the people concerned that following the new methods or metrics leads to the desired outcomes any more effectively than the old ones, however, they are unlikely to behave differently after being trained in the use of the new routines. The effectiveness of training is more dependent on the level of agreement about how the world works than on the quality of the training itself.

In the upper-left region of Figure 11.3, results-oriented tools, as opposed to process-oriented ones, are more effective because there is a high existing consensus about what employees want from their participation in the organization. Charismatic leaders who command respect, for example, often do not address how to get things done; instead they motivate people to just do what needs to be done. The same actions that employees view as inspiring and visionary when they're in the upper-left corner of the agreement matrix are often regarded with indifference or disdain when the people are in the lower quadrants. For example, when people agree on what they want to achieve, vision statements can be energizing. But if people do not agree among themselves about what they want, vision statements typically induce a lot of eye rolling.

People located in the matrix's upper-right region will cooperate almost automatically to continue in the same direction. This is the essence of a strong culture. Their common view of what they want and of how the world works means that little debate is necessary about where to go and how to get there.67 But this very strength can make such organizations highly resistant to change. The tools of cooperation that are available in the realm of strong culture—including ritual, folklore, and democracy—facilitate cooperation only to preserve the status quo; they begrudgingly yield to change. When executives in this circumstance see big changes in the future and realize that the organization's momentum is propelling it in the wrong direction, the culture often fires the manager. Just ask former CEOs John Sculley (Apple), Durk Jager (Procter & Gamble), Carly Fiorina (Hewlett-Packard), and George Fisher (Kodak).

Where are health-care systems positioned in the agreement matrix? For the most part, they are in the lower-left corner of the diagram. Patients, doctors, regulators, IT professionals, hospital administrators, insurance companies, executives in pharmaceutical and medical device companies, small businesses, large businesses, and politicians all have divergent priorities and disagree strongly about how to achieve them.

The fact that health care is in the lower-left world of disagreement helps explain why certain remedies that reformers tried to introduce in the past have not worked. For example, reformers who advocate evidence-based medicine bewail the fact that many doctors continue to follow their own instincts rather than best demonstrated practices. But if those recalcitrant doctors don't agree that doing it a certain way brings the desired results, they won't follow the rules. Similarly, the reason why metrics of performance and value have been almost impossible to create is that the conflation of solution shops and value-adding process businesses within hospitals puts us in the lower-left portion of the matrix. Metrics of performance only work if there is strong agreement on cause and effect, and a modicum of agreement on what various parties want from their participation in the enterprise.

The scary thing about this situation is that democracy—the primary tool in most societies where health-care reform is at issue—is effective only in the upper-right circumstance, when there already is broad, preexisting consensus on what is wanted and how the world works.68 And what's worse, like all the tools in the culture quadrant of the matrix, democracy is not an effective tool for radical change—it is a tool best used for maintaining the status quo.

So is it possible that changing our health-care systems is impossible? No, it can be done—if we use a fifth tool—that of separation.

There are instances in which disagreement among the parties that need to cooperate is so fundamental that it's simply impossible to reach consensus on a course of action—and yet no one has amassed the power to coerce cooperation. When all other tools have failed, there is a trump card to play, and it does not reside within the agreement matrix. We call it "separation"—dividing the conflicted parties into separate groups so they can each be in strong agreement with others inside their own group, yet don't need to agree with those in other groups. In the post-Tito Balkans, by illustration, no one could again successfully amass and wield the requisite power to maintain peace, as Tito had. So we tried the charisma of President Bill Clinton and sales skills of Prime Minister Tony Blair. We tried democracy and negotiation. We used economic sanctions and incentives. Nothing worked—except separation. Peace came to the Balkans when the need for cooperation across antagonistic ethnic divides was obviated by dividing the peninsula into nations and regions for each ethnic group.

In our studies of disruptive innovation, we have seen the same thing. The only instances in which an industry's leading company also became the leader in the following disruptive wave occurred when the corporate leaders wielded the separation tool. These companies survived disruption by establishing an independent business unit under the corporate umbrella and giving it unfettered freedom to pursue the disruptive opportunity with a unique business model, essentially placing it in competition with the parent company.

If employees responsible for sustaining the core business must work in the same business unit as those responsible for disruptive products, they are forever conflicted about whether new or existing customers are most important; whether moving up- or down-market offers more growth; and so on. Separation in these instances is the only viable course of action. In addition, it takes the power of the CEO suite to wield the tool of separation. As a result, only a few companies have ever successfully disrupted themselves.69

It is this model that provides the theoretical foundation for our recommendation of "Starting where they aren't" when pursuing deregulation. Situations requiring regulatory reform, by definition, are in the lower-left corner of the agreement matrix. Cramming deregulation down the throats of those who don't want it requires extraordinary power—and in a democracy, nobody possesses such power. In a health system such as America's, private entrepreneurs can find interstitial spaces in which to establish a disruptive foothold—out of the eyesight and earshot of regulators and influential competitors in the existing market. If America's government were to bring health care into a single-payer system, by definition it would make it impossible to incubate reforms in fringe areas "where they aren't." And it would strip from executives in the industry the ability to wield the tools of power that are critical to making things happen in situations where disruptive innovations will be unpopular to the established interests.