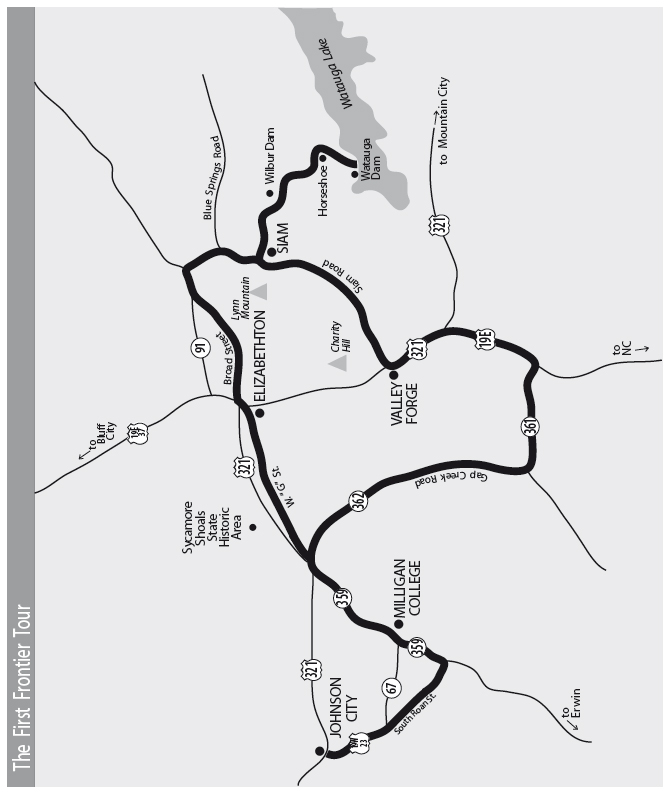

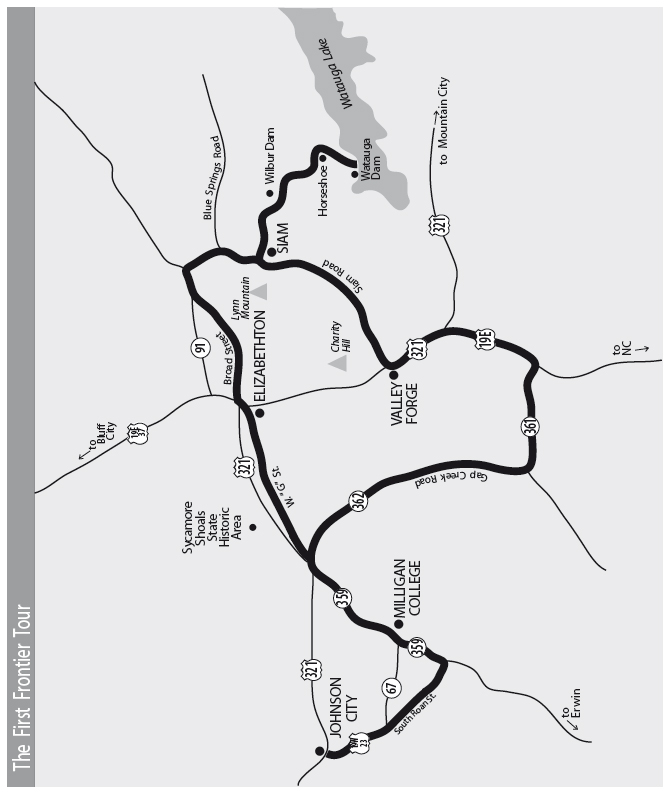

This tour begins at Sycamore Shoals State Historic Area. It travels into Elizabethton’s historic district, then past the John and Landon Carter Mansion to Wilbur Lake, Watauga Dam, and Valley Forge. It continues through the Doe River Gorge to Gap Creek Road, the Big Spring, Sabine Hill, Happy Valley, Milligan College, and the Tipton-Haynes Historic Site. It ends in Johnson City.

Total mileage: approximately 40 miles.

This tour begins at Sycamore Shoals State Historic Area in Elizabethton. An overview of the early history of East Tennessee will prove helpful in understanding the exhibits at the historic area, as well as many of the other sites on this tour.

White settlement in East Tennessee started in the mid-1700s. After early explorers, traders, and long hunters returned with stories of the land beyond the Alleghany Mountains (the name found in early records for what we call the Appalachians), it was only a matter of time before white settlers infiltrated. In 1763, King George III of England issued a proclamation ordering all white settlers to withdraw to the eastern side of the Alleghanies. In an effort to cut the expenses of recurrent Indian warfare, the British reserved the land west of this line for the Indians. A series of treaties left the exact location of land open for settlement unclear. White settlers in Virginia and North Carolina capitalized on the confusion and moved westward.

The first white men had actually moved into the area in the 1750s, when several traders and hunters established camps in the region where the Watauga and Doe rivers meet. The name Watauga came from the Creek word Wetoga, meaning “broken waters.” The first settlers who followed the river to this location found a rich, open valley already cleared by the Indians. They also discovered graves and ancient remains that indicated the area had once been an Indian town—hence their reasoning in calling it “the Watauga Old Fields.”

It wasn’t until twenty-eight-year-old James Robertson arrived in 1770 that permanent settlement of the Old Fields began in earnest. Robertson came from the Yadkin Valley in North Carolina to scout the territory. Some sources say he first heard about the new valley from Daniel Boone, who frequently hunted in the area and was acting as a scout for a land company owned by Richard Henderson. Robertson stayed with local hunters and traders while he raised a crop of corn to feed the settlers who would follow him later. When the crop was harvested, Robertson began the journey eastward to lead others to what he called “the promised land.”

The story of Robertson’s trip to North Carolina may have been embellished over the years, but it still indicates the resilient spirit that was necessary on this early frontier. Sources say Robertson left the Old Fields during a period of heavy rains. He soon lost his way and eventually had to abandon his horse because of the impenetrable rhododendron thickets. Then he found that his powder was too wet to allow him to shoot game for food. He wandered in the wilderness for several days until two hunters found him. Some accounts say the hunters revived him with a little applejack and gave him a horse.

Whatever the truth behind the legend, the hunters’ rescue of Robertson opened the floodgates to settlement. When Robertson returned to North Carolina, his enthusiasm convinced between sixteen and twenty families to return to the Watauga Old Fields, creating the first permanent settlement west of the Appalachian Mountains. That first settlement was located on the land where Sycamore Shoals State Historic Area and the city of Elizabethton now stand. By 1779, Robertson was one of the leaders of the settlers who founded what eventually became the city of Nashville. It is small wonder that he became known as “the Father of Tennessee.” (For more information about Robertson, see The Rogersville to Kingsport Tour, pages 159–60.)

In 1771, surveyors discovered that the settlements along the Watauga, Holston, and Nolichucky rivers were not located in Virginia, as previously thought. The survey also indicated that the settlers were in violation of the treaty that designated their settlement as land reserved for the Indians.

Records in 1772 showed between seventy-five and eighty-five farms along the banks of the Holston and Watauga rivers. The settlers met and decided to ignore the officials who ordered them to move back across the mountains.

Faced with the prospect of no protection from the government and the need to record deeds, marriages, wills, and other public business, the settlers met to organize their own government. In May 1772, a meeting of all free men over the age of twenty-one was called. Using the Virginia laws as a guide, the men formed the Watauga Association.

Lord Dunsmore, the British governor of Virginia, wrote to the British secretary of state that “a set of people” in the back country had “appointed magistrates and framed laws” and to all intents and purposes erected themselves a separate state, thereby setting a “dangerous example to the people of America, of forming governments distinct from and independent of his majesty’s authority.” These written articles of the Watauga Association are accepted by most historians as the first constitution west of the Appalachians.

At approximately the same time, the settlers decided to address the problem of squatting on Indian land. They came up with a rather ingenious way to get around the British order to move eastward—they arranged to lease their land from the Cherokees. The Cherokees chose Attakullakulla, or “Little Carpenter,” to negotiate the lease for them. For a few thousand dollars in merchandise, the Cherokees granted the use of all the country on the waters of the Watauga to the settlers—the Wataugans—for ten years.

To celebrate the new lease, a day of games was held at Sycamore Shoals in the spring of 1774. Unfortunately, before the day was over, a white settler—the sole survivor of an Indian raid the year before—shot one of the Cherokees. The Cherokees withdrew in an understandably foul mood.

James Robertson and an interpreter traveled the 150 miles to the Cherokee town of Chota (called Echota in many early documents). After hearing expressions of the settlers’ horror at the shooting and their promises to bring the culprit to justice, the Cherokee chiefs agreed not to seek revenge. Some Cherokees did not agree with this decision and later cited the incident when raiding frontier settlements.

In 1774, North Carolina lawyer Richard Henderson learned from his agent, Daniel Boone, that the Cherokees might be willing to dispose of their lands in western Kentucky. Henderson added new stockholders to his Transylvania Company and made the Cherokees an offer.

By January 1775, the Cherokees began camping at Sycamore Shoals, where Henderson had stored six wagons of merchandise that would go to the Cherokees in exchange for their land. By March, twelve hundred Cherokees were camped in the area. Serious negotiations started. Henderson offered two thousand English pounds in cash and eight thousand pounds’ worth of merchandise for the whole Cumberland Valley and the southern half of the Kentucky Valley.

The Cherokees argued among themselves, the main opposition to the purchase coming from Attakullakulla’s son, Dragging Canoe. Dragging Canoe eloquently told his elders that they were paving the way for their own destruction, that the whites would not be satisfied with this one purchase, that the lands of other Indian tribes had already “melted away like balls of snow in the sun.” The next day, eighty-year-old Attakullakulla showed that he could also summon up powerfully persuasive oratory. Contrary to his son’s wishes, he turned the council toward the purchase. Dragging Canoe declared that he, for one, would never yield another foot of native soil.

On March 17, the older chiefs signed the Treaty of Watauga, selling Henderson’s company twenty million acres of land. This event, which became known as the Transylvania Purchase, was the biggest private or corporate land deal to that point in American history—and it was also totally illegal under British law.

But Dragging Canoe had one last word. Although different versions were reported, they all had a similar ring—the young brave predicted that dark clouds would hang over Kentucky, that it would be a bloody ground difficult to settle. Dragging Canoe went on to play an important role in fulfilling that prophesy. (For more information about Dragging Canoe, see The Rogersville to Kingsport Tour, pages 156–58, and The Trail of Tears Tour, pages 344–46.)

The leaders of the Watauga community followed Henderson’s lead and purchased the land they had previously leased from the Cherokees. Although Lord Dunsmore was furious, he could do little to enforce the British laws on the frontier.

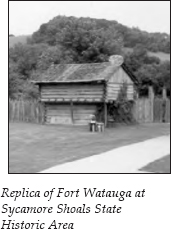

When the American Revolution broke out in 1776, English agents again warned the Watauga settlers to move behind treaty lines. The Wataugans knew they were in a precarious position. They began building up their forts in preparation for Indian attacks. One such fort was Fort Caswell, later called Fort Watauga, near Sycamore Shoals. A replica of that fort now stands at the park.

True to his threat, Dragging Canoe was one of the leaders of the Cherokees who began attacking forts all along the frontier. However, the white settlers were given a warning from an unlikely source. Nancy Ward, a Cherokee called “Beloved Woman” by her tribe and a niece of Attakullakulla, knew that war would be disastrous for her people. She decided to warn the settlers. (For more information about Nancy Ward, see The Trail of Tears Tour, pages 330–31.)

When the attacks began in July 1776, the white settlers were ready. One group of Cherokees, led by Abraham of Chilhowee, reached Fort Caswell on July 21. Several legends involving this attack have survived. One says several women were out milking cows when the attack began. During the confusion, the gates of the fort were closed, leaving one woman, Catherine Sherrill, outside. Being resourceful, “Bonny Kate,” as she was known, scaled the wall. As she reached the top, Kate was assisted by John Sevier, one of the commanders of the fort. She would marry Sevier four years later. (Most sources spell her nickname Bonny, but in Carter County it is Bonnie.)

A second legend arose during the two-week siege. In the course of one attack, the Indians tried to burn the fort. Ann Robertson, sister of James, organized a bucket brigade of women, who poured boiling water down on the attacking Indians. Though wounded during the attack, Ann Robertson continued to pour scalding water down the walls of the fort until the Indians withdrew.

Another woman, Lydia Bean, was captured while trying to reach the fort from her home. She was taken to the Cherokee town of Toqua, where she was questioned. While the Indians were preparing to burn her at the stake, Nancy Ward once again intervened. She scolded the warriors for stooping so low as to torture a squaw, and Lydia Bean was spared. During her captivity, Lydia taught the Cherokee women how to make butter and cheese. After the hostilities ended, she returned to her home to tell of Nancy Ward’s intercession.

Today, a monument designates the original location of the fort. You will pass it later in this tour.

By September 1780, the British seemed to be beating the Americans. They turned their attention to patriot forces in the South. British commander Patrick Ferguson sent a message to Colonel Isaac Shelby warning American militia officers on the Watauga, Nolichucky, and Holston rivers to halt any opposition to the British or he would march his army over the mountains, hang the leaders, and lay waste to their country with fire and sword.

Ferguson greatly underestimated the men of this frontier, who did not take threats lightly. Shelby rode to the home of John Sevier, where tradition says Sevier was celebrating his wedding to Bonny Kate Sherrill. Sevier and Shelby consulted and then issued a call to area forces to volunteer in aiding the patriots against Ferguson.

On September 25, 1780, approximately one thousand men from the frontier assembled at Sycamore Shoals. They came to be known as the Overmountain Men. In sending them off to fight, the Reverend Samuel Doak offered the following prayer: “O Lord, have consideration for the British, for Thou knowest that we intend to bring them to Thy Bosom.” (For more information about Samuel Doak, see The Jonesborough to Greeneville to Bulls Gap Tour, pages 110–11, 115–16.)

On October 7, 1780, the Overmountain Men found Ferguson’s army at Kings Mountain, just over the South Carolina line. At the end of the battle, Patrick Ferguson lay dead, his army defeated. Historians credit this victory with tipping the balance of the war in the South.

As a gathering point for preserving the memory of all these historic events in early Tennessee history, Sycamore Shoals State Historic Area sets the stage for any tour of the region. The historic area includes a fifty-acre park, a visitor center with historic displays and an interpretive film, a replica of Fort Watauga, and a fitness trail that offers a nice walk along the Watauga River to the location of the actual shoals.

From the park, turn left onto U.S. 321, also known as Elk Avenue. When U.S. 321 bears left, continue straight, following the signs directing you to the historic district. You are still on Elk Avenue.

Elizabethton was named for Elizabeth Carter, the wife of General Landon Carter. (More information about the Carter family is presented later in this tour.) When Carter County was created in 1796, the commissioners chose what is now Elizabethton as the seat of justice. Seventy-seven lots were laid out, nine of them reserved for public buildings.

As Elk Avenue turns left going into the downtown business district, you will see the Soldier’s Monument ahead. This sixty-five-foot cement shaft was built as a memorial to the soldiers of Carter County in all conflicts from the Revolutionary War to 1912, when the monument was dedicated. The monument includes a tribute to the memory of Mary Patton, “who made the gunpowder that fought the King’s Mountain Battle.”

Mary Patton made her powder at a mill located on Powder Branch. Some amusing stories about her have survived. She supposedly carried her powder as far as South Carolina, where she sold it for a dollar a pound. She then invested the profits in real estate, which she purchased for fifty cents to a dollar an acre. She was supposedly so thrifty that she would shoe her horse for one of her sales trips and take the shoes off upon her return, saving them for her next trip.

One story says she stopped overnight at an inn, where she met a man who was traveling the same way. She suggested they could travel together if he would wait a few minutes. The man agreed to wait, saying, “Bad company is better than none.” After several hours of travel, the stranger, thinking he had missed his turnoff, asked where it was. Mary answered, “Fourteen miles back. I thought bad company was better than none.”

When Mary Patton died in 1836 at the age of eighty-five, she owned seventeen hundred acres of the best land in the area.

After traveling two blocks into the business district on Elk Avenue, turn right onto Sycamore Street at the stoplight. Go one block to Hattie Avenue and turn left. This block boasts several late-nineteenth-century homes that indicate the neighborhood was once one of Elizabethton’s most prosperous.

The lot on the corner of Hattie Avenue and Riverside Drive was once owned by Hattie Taylor, for whom the street was named. Hattie Taylor was the daughter of Dr. Abraham Jobe, who deeded a six-acre parcel of land as a “token of love and affection” to his daughter in June 1884. Hattie married Nathaniel Winfield Scott Taylor, a great-grandson of General Nathaniel Taylor and the brother of Alfred Alexander Taylor and Robert Love Taylor. A later deed shows that Robert Love Taylor and his wife, Sarah, also owned the two-story white frame house that sits on the corner today. (More information about the Taylor family is presented later in this tour.)

To the left a few yards down Riverside Drive is a marker on the lawn in front of a house. The marker designates the spot where the first court west of the Alleghany Mountains was held in 1772. When the Watauga Association was established, five magistrates were appointed. Their first court sessions were held under a large sycamore tree located on the spot where the marker now stands. Unfortunately, the sycamore, which old photographs show as a huge, sprawling tree, no longer exists. A portion of the tree’s trunk has been preserved. It stands under a shelter next to the entrance to the Doe River Covered Bridge.

Tradition gives us stories of this early court that indicate some creative approaches to justice. If a settler was of generally bad character but the court was unable to punish him for a specific crime, he was notified by the sheriff to “take poplar.” This meant that he was given time to build a poplar canoe and sail down the Watauga out of the settlement.

Another story survives about a man who stole some freshly baked bread. Given the nickname “Bread Rounds,” he suffered the punishment of having everyone in the community call his nickname and his full name each time they saw him. This punishment soon caused the man to leave the area.

And of course, horse thieves were branded with an H and a T on each cheek.

The centerpiece of Elizabethton’s historic district is the Doe River Covered Bridge. Built in 1882, the predominantly oak structure stretches 134 feet to span the river. The bridge, built at a cost of three thousand dollars, is listed in the Historic Engineering Record. The original structure was made entirely of wood, with the exception of steel spikes, which fastened the massive oak pieces in the floor.

During the flood of 1901, all other bridges in the county were destroyed. This bridge offered residents on the east side of town their only means of escape to higher ground.

The present-day structure is walled with boards, except for a few windows. Supposedly, these high openings prevented livestock from seeing the water below. The walkway inside serves those who wish to walk across the bridge to enjoy the surrounding park or to take a few photographs.

To continue the driving tour, turn left onto Riverside Drive and go one block to Elk Avenue, where the Soldier’s Monument stands. Behind it is the county courthouse. The core of the courthouse was constructed during the 1850s, but the building has been altered several times. In the courthouse yard is a boulder with a plaque commemorating the Watauga Old Fields, where the Watauga Association was formed.

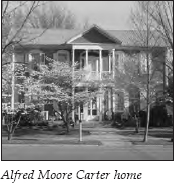

Turn right onto Elk Avenue. On the left in the next block is the Alfred Moore Carter Home, considered one of the finest Federal-style structures in Tennessee. Alfred Moore Carter was the son of Landon Carter. He followed in his father’s footsteps by constructing a stately home. The house, built in 1819, is covered with wide, hand-hewn tongue-and-groove boards. The foundation and chimneys were built of large bricks imported from England. An old “upping stone”—used to assist riders mounting their horses—still stands in front. Today, this building houses the Carter at Main Restaurant.

Alfred’s son Samuel P. Carter was born in this house. He spent two years at Princeton before graduating from the United States Naval Academy. During the Civil War, President Lincoln made him a brigadier general and sent him back to East Tennessee to organize volunteers. After the war, he returned to the navy, eventually becoming a rear admiral. Samuel Carter stands as the only man in United States history to achieve the ranks of major general and rear admiral. His brother, William Blount Carter, Jr., was commissioned by President Lincoln to organize the “bridge burners” of East Tennessee. (A detailed description of the bridge burners’ activities is presented later in this tour.)

The home directly across the street, now used by the Agricultural Extension Service, is known as the Folsom House. It was built in 1861 by Henderson Mitchell Folsom, who was Carter County’s only commissioned major in the Confederate army. Ironically, he lived right across the street from some of the area’s strongest Union supporters.

Continue on Elk Avenue to the end of the block, where it intersects the four-lane U.S. 321/19E. For those who want more tourist information, the chamber of commerce is straight ahead, across the highway. In front of the visitor center is an interesting exhibit about trains in Carter County. Included is an original boxcar used by the East Tennessee & Western North Carolina Railroad, which was popularly known as “Tweetsie.”

The exhibit also showcases a Southern Railroad caboose and a North American Rayon steam engine, believed to be the last active steam locomotive in the country.

From the visitor center parking lot, turn right onto U.S. 321/19E. At the intersection, turn right onto Broad Street. It is 0.1 mile to the John and Landon Carter Mansion, on the left. Although your first impression may make you question the word mansion, the interior of this structure, open to the public, deserves that title. For its time and location, it was undoubtedly a mansion.

John Carter and his son Landon left their home in Virginia and settled west of what is now Kingsport in an area that is still known as Carter’s Valley. (For more about Carter’s Valley, see The Rogersville to Kingsport Tour, pages 150–51.) About 1770, after Indians burned their store, they moved to the Watauga settlement, where they became leaders of the community. In fact, if you read the biographies printed on the monument in the graveyard adjoining the mansion, it sounds like they ran the whole settlement. When the Watauga Association was formed, John Carter was elected chairman of the court. He was also colonel of the militia stationed at Fort Watauga during the Revolutionary War, and he served as a member of two constitutional conventions in North Carolina. At his death in 1781, he left an estate worth an estimated five hundred thousand pounds, the largest in existence at that time in North Carolina.

Landon Carter was no lightweight either. He was a captain at Kings Mountain, the secretary of state of the State of Franklin (see The Beauty Spot to Nolichucky Tour, pages 68–70), a member of North Carolina’s constitutional convention, a member of the first constitutional convention in Tennessee, and a brigadier general of the Tennessee militia. He also built the first iron forge in the county. When Carter County was established in 1796, it was named for Landon Carter, and the county seat, Elizabethton, was named for his wife, Elizabeth Maclin Carter. When Landon Carter died in 1800, he was survived by his wife and seven children. Many of these Carters are buried in the cemetery next to the mansion.

The mansion’s exterior was built of clapboards with windows placed high as a defensive measure against Indian attack. The glass windows were supposedly the first on the frontier. Many of the interior features strikingly resemble the interior of Shirley, the Virginia home of another Carter family. When you enter, you will be struck by the extensive woodwork and paneling, which must have seemed incredibly opulent on the frontier of the late eighteenth century. The mantels over the fireplaces are particularly impressive, especially the one in the master bedroom, where an oil painting on a single panel of wood depicts a stag, pursued by a dog, bounding toward a church and graveyard.

After viewing the mansion and cemetery, continue on Broad Street, heading out of Elizabethton. Travel 2.6 miles along the Watauga River. Just before crossing the river, you will see Lincoln Drive on the right. This area was once the farm of Isaac Lincoln.

Lincoln arrived around 1773 or 1774. Eventually, he came to own about twelve hundred acres on or near the Watauga River. Isaac and his wife, Mary, built their home about 4 miles up the Watauga from the mouth of the Doe River. One of Mary’s sisters married Daniel Stover, who settled in nearby Siam about 1796. Mary and Isaac were childless, but they took Mary’s nephew William Stover into their home. (The Stover family will appear again later in this tour.)

In 1798, another nephew, Thomas Lincoln, came from his home in Kentucky to work for his uncle. He lived in a log cabin near the base of Lynn Mountain, the high peak visible on the right as you drive along the river. Historian Samuel Cole Williams describes Thomas Lincoln as “thriftless.” Tradition says Uncle Isaac was so displeased with his nephew that he sent Thomas home. Ten years later, Thomas Lincoln and Nancy Hanks became the parents of a baby boy, Abraham.

Continue across the bridge and turn right onto TN 91 North. You’ll see a historical marker for Carriger’s Landing on the right.

Godfrey Carriger came to this area from Pennsylvania in 1782. He was one of the wealthiest of the settlers, bringing with him slaves, six four-horse wagons loaded with supplies, and thirty-five thousand dollars in cash. He also brought the area’s first cookstove, which people came from miles around to see. Carriger’s Landing was the loading place for the corn, wheat, and wrought iron that was shipped out of this area in the late 1700s and early 1800s. It was also the place from which many immigrants embarked for westward travel.

One of Godfrey Carriger’s sons, Christian, married Levisa Ward, another sister of Mary Ward Lincoln. Christian built one of the first brick houses in the area; it still stands on this site today. Christian later moved to Missouri, fought with John C. Fremont in the Mexican War, and died while crossing the Rocky Mountains on his way to California.

Go 0.8 mile and turn right at the stoplight onto Blue Springs Road. Just before the turn, you will pass Hunter First Baptist Church on the left. A sign at the turn indicates this is the route to Wilbur and Watauga dams.

As you travel the first 0.9 mile on Blue Springs Road, the road makes a couple of ninety-degree turns. Follow the turns and stay on the paved road. When you come to the first left-angle turn where a paved road continues straight ahead, stay straight. You are now on Steel Bridge Road, traveling alongside the Watauga River. You will see a steel bridge ahead. It is 0.9 mile to the right-angle turn that leads across the bridge.

After crossing the bridge, the road makes a left turn. After 0.2 mile, you will notice Wilbur Dam Road coming in from the right. Make note of this road for your return trip.

Continue straight; the road is now named Wilbur Dam Road. It is another 0.2 mile to the community of Siam. You will see old bridge abutments standing in the river on your left. Siam now consists of a few buildings and a gas station on the right.

It is 1.5 miles from Siam to Wilbur Dam. This area was originally Wilbur Lake, used as a power reservoir for East Tennessee Light and Power Company before Watauga Dam was built. The lake is approximately 1.5 miles long and two hundred to three hundred yards wide, with a shoreline between 3 and 4 miles in total length. The north and east shorelines are actually high bluffs.

The road follows the gorge for much of the way. It is 0.7 mile to a riverside picnic area on the left; it is obvious why the bend in the river here was known even by the earliest settlers as Old Horseshoe. The road then crosses the river and begins the climb to the top of Watauga Dam, where you’ll find a reception center and a view of Watauga Lake surrounded by mountains. (For more information on Watauga Lake, see The Mountain City Tour, pages 40–42.)

After viewing the lake, return to Siam. After passing Siam, go 0.2 mile to the left turn onto Wilbur Dam Road, noted earlier.

It is 0.7 mile to an intersection where you must turn. Turn left onto Siam Road. It is 0.6 mile to Siam Baptist Church, on the right.

The first school in Siam was established before 1850 on land donated by Daniel Stover. Daniel Stover was the son of William Stover, who was raised by Isaac and Mary Lincoln. Daniel married Mary Johnson, the daughter of Andrew Johnson, who became president of the United States. Andrew Johnson visited the Stover home frequently after his retirement and died in the Carter County home of his widowed daughter in 1875. Siam Baptist Church stands on the school lot donated by Daniel Stover. Siam School is across the road.

The area to the right of the road just past the church is called Charity Hill. In the 1800s, Charity Hill was home to the Ellis family. This area was a prime example of “brother against brother” during the Civil War. For example, Caleb Cox, who married a descendant of the Carriger family, had two sons who served on opposite sides in the war. The brothers, killed during the conflict, were buried side by side. Caleb Cox supposedly remarked, “One was right and one was wrong, but God will decide.”

Probably the most notorious soldier to emerge from this area was a man from Charity Hill, Daniel Ellis.

In November 1861, a group of Union loyalists led by William Blount Carter instigated a plan approved by President Lincoln himself. On the designated night, Unionists would simultaneously attack, seize, and burn all nine bridges on the railroad through East Tennessee, thus knocking out a 225-mile stretch of track. Federal troops would then make a thrust out of Kentucky that the Confederates would be unable to counter because of the crippling railroad attack, and East Tennessee would revert to Union control.

Unbeknownst to the men of East Tennessee, the Confederates made a preemptive attack on the Kentucky forces, so no help would be forthcoming from that arena. Nevertheless, the Carter County rebellion went forward as planned. The Unionists succeeded in destroying five of the nine bridges, alerting the Confederate army that something was afoot that needed to be suppressed. When it became apparent to the bridge burners that no immediate help was coming from the Federals, many fled to the mountains to escape punishment. Many who did not were captured and hanged.

One of the bridge burners was Daniel Ellis. As he later described in his autobiography, Thrilling Adventures of Daniel Ellis, the Great Union Guide of East Tennessee for a Period of Nearly Four Years During the Great Southern Rebellion. Written by Himself, his illustrious career as a “pilot” began when he fled to the hills to avoid being hanged. A pilot’s role was to guide Union sympathizers, escaped Union prisoners, and runaway slaves to safety in Kentucky. Colonel Daniel Stover, the leader of the bridge-burning element, was the first man Ellis piloted.

Ellis supposedly guided over four thousand men through Confederate lines, as well as conducting an informal mail service for soldiers sending letters home to their loved ones. A standing five-thousand-dollar reward was offered for his capture, but “the Old Red Fox,” as he was called by the rebels, was never caught. When he died on January 6, 1908, he was buried in the family cemetery at Charity Hill.

Although Ellis hardly hides his bias against the Confederates, whom he usually describes as “howling fiends from the nether pits of Hell,” his story is great fun to read and amazingly articulate. He frequently uses analogies from the classics and cites Shakespearean lines in just the right context, suggesting a ghost writer from Harper & Brothers. However, his chronicle does give a compelling picture of the atrocities committed in an area that epitomized the bitter division caused by the war.

It is 3.2 miles from Siam Baptist Church to the intersection with U.S. 321/19E at Valley Forge. Turn left onto the four-lane highway and head into the Doe River Gorge. The four-lane is a modern addition to the gorge. (For more information about the gorge, see The Mountain City Tour, pages 38–39.)

Travel past the turnoff to TN 67 East and U.S. 321 South leading into the town of Hampton. (For information about Hampton, see The Mountain City Tour, page 39.)

Continue on the four-lane. It is 1.9 miles on U.S. 19E to the turnoff for TN 361, also known as Gap Creek Road. Turn right and cross the Warner Dunlap Bridge. A sign designates this road as part of the Overmountain Victory Trail.

After 1.5 miles, TN 361 goes off to the left. Stay on TN 362, which is the continuation of Gap Creek Road. This is the same route taken on September 26, 1780, by the men who gathered at Fort Watauga before marching to fight the British at Kings Mountain.

It is 3.8 miles from the TN 361/362 intersection to the Elizabethton water treatment plant, on the right. This area was once known as Clark’s Big Spring, a well-known landmark that the Overmountain Men passed on their journey.

Colonel Daniel Stover gathered about a thousand men at the Big Spring on November 10, 1861, after their bridge-burning activities. According to Daniel Ellis, his group succeeded in burning the bridge over the Holston River at the town of Union in Sullivan County. The bridge over the Watauga River some 6 miles from Elizabethton at Carter’s Depot (now the community of Watauga) escaped destruction because a company of rebels was stationed there. The bridge burners who gathered on the Watauga River were soon joined by other Union sympathizers. When they received word that rebel reinforcements were on the way, Stover and his group moved out to the Big Spring. Later, they marched on to Elizabethton, but news that rebel forces were “killing every man whom they might find who had been concerned in the rebellion in Carter County” caused them to retreat to the mountains, thus beginning Ellis’s career as “the Old Red Fox.”

The Big Spring was capped in 1982 and now provides water for the city of Elizabethton. The capped spring is next to the water treatment plant.

Continue on TN 362 for 1.7 miles to the intersection with West G Street. This area was once known as Watauga Point. Turn right onto West G Street and go 0.5 mile to a monument erected in 1904 to honor the patriots who fought at Kings Mountain. The three-sided shaft of river rocks sits on the right near the site of the original Fort Watauga, built in 1776 as the first settlers’ fort west of the Alleghanies. It is hard to visualize the excitement at the monument’s dedication, but local newspaper articles say that a special train ran from Johnson City carrying a thousand people. A similar train from Bristol brought five hundred more.

Return to the intersection with Gap Creek Road and continue straight. When the road turns right, continue a few feet to where the old road dead-ends. On a hillside on the left is Sabine Hill, the home of the Taylor family, who once owned all of this area, known as Happy Valley. At the time of this writing, Sabine Hill was for sale. One can only hope the new owners will realize the structure’s history and preserve it for future generations.

Sabine Hill was built in 1816 by General Nathaniel Taylor. Taylor was the first sheriff of Carter County and later served in the Tennessee legislature. Commissioned a major general while serving under Andrew Jackson in the War of 1812, he was placed in charge of the fortifications at Mobile, Alabama, when Jackson left for New Orleans. Taylor died before he completed Sabine Hill, but his wife, Mary, finished the house and lived here for thirty-seven years after the general’s death. Traces of the original paint in the house bear out the legend that the general and his wife showed their patriotism by painting the walls white, the wainscoting blue, and the molding red.

The Taylor family is probably best remembered for two of the general’s great-grandsons, Alfred A. Taylor and Robert Love Taylor. Alf was born in 1848, Bob in 1850. Their father, the Reverend Nathaniel G. Taylor, was a lawyer, a Methodist minister, a congressman, and a strong supporter of the Union during the Civil War. Their mother, Emmaline Haynes Taylor, was a sister of Landon Carter Haynes, one of Tennessee’s Confederate senators, and her sympathies lay with the South. (Landon Carter Haynes is discussed later in this tour.)

In 1878, Alf Taylor sought the Republican nomination for Congress but was defeated in the primary by his rival, Major Pettibone. Some Democratic leaders then prevailed upon Bob Taylor to accept that party’s nomination. During the election, Bob capitalized on the fact that he was a native Tennessean, while Major Pettibone was born in Michigan. Bob used his fiddle and extended anecdotes to entertain his audiences. At one gathering, Pettibone irately accused Bob of being nothing but a fiddler. Bob rose for his turn, placed his fiddle case on the platform, and said, “I ask you to choose between this that I carry with no apology and the carpetbag so furtively carried by that one.”

The ploy worked, and Bob was elected a Democratic congressman from the First District, which even today can be counted on to vote Republican. An interesting side note concerns this election. Bob Taylor hired Daniel Ellis as a bodyguard during the campaign. When Taylor won, he rewarded Ellis with the position of assistant doorkeeper of the House of Representatives. Taylor later lost his reelection bid to Pettibone, some said because he married a woman from North Carolina.

In June 1886, the Republicans selected Alf as their gubernatorial candidate. Two months later, the Democrats selected Bob to run for governor. Thus, the stage was set for one of the most colorful election campaigns in history.

Tradition says that their mother, Emmaline, was responsible for the high tone of the campaign. The brothers supposedly signed an oath swearing that if they were ever angry at each other, one would quit the campaign. Emmaline made them promise to argue only about party platforms.

The two sons followed their mother’s directive. They held forty-one debates throughout the state. At the first debate, Bob said, “I have a high regard for the Republican candidate—he is a perfect gentleman because he is my brother. I have already told him to come with me and I would furnish him with crowds and introduce him to society. We are two roses from the same garden.”

Their campaign was soon dubbed “the War of the Roses.” Bob and his supporters took to wearing white roses in their lapels, while Alf and his supporters wore red roses. They also decided to entertain the crowds with music and repartee by playing the fiddle and telling stories. Neither man took himself too seriously, and both used humor to lighten the atmosphere. At a debate in Jonesborough, too many people sat on Alf’s end of the platform, causing it to collapse. Bob jumped up and shouted to the crowd not to be alarmed, that it was merely the “weak Republican platform giving way beneath its candidate.”

One typical story told by the brothers during the campaign concerned a mountain man who was asked to testify about a murder. The man claimed not to know much about the events leading up to the murder. In an effort to get the mountain man to provide evidence, the prosecutor instructed him to “tell what you know.” The witness then proceeded,

We was all up thar at the big dance celebratin’. . . .The fiddles was playin’ and we was swingin’ corners, and the boys got to slappin’ each other on the back as they swung. Finally one of them slapped too hard and the other knocked him down. His brother shot that feller, and that feller’s brother cut t’other feller’s throat, and the feller that was knocked down drawed his knife and cut that feller’s liver out; the old man of the house got mad and run to the bed, turned up the tick and grabbed his shotgun and turned both barrels loose on the crowd, and I saw there was goin’ to be trouble and I left.

Stories like these drew great crowds—fifteen thousand in Memphis, ten thousand in Jackson, twenty-five thousand in Nashville. When the ballots were counted, Bob had won by thirteen thousand votes, an unprecedented Democratic margin. But Alf had also set a record for the largest Republican vote in Tennessee up to that date.

Bob went on to serve as governor for three terms and also as a congressman and senator. Alf was a congressman three times and was finally elected governor in 1921, at the age of seventy-two.

After Bob served his second term as governor, he found himself broke. He wrote to Alf for advice, and Alf responded, “The fact that you can serve two terms as governor and come out of office broke convinces me that your hands are clean. Now pay up your debts and move your family to my home. . . . I’ll take care of you till you get back on your feet.” Bob took Alf’s advice and, while living with his brother, wrote his first lecture, “The Fiddle and the Bow,” which made a name for him on the lecture circuit and brought in an estimated seventy-five thousand dollars in admissions. Alf later joined him on the lecture circuit for a joint effort called “Yankee Doodle and Dixie.” The brothers made a good living doing what they did best—entertaining—but they also left a political legacy that is still remembered.

From the dead-end road, you can see the intersection with U.S. 321/TN 67. Turn left onto this four-lane highway. It is 0.3 mile to a stoplight at the junction with TN 359 North. You will see a sign pointing toward Milligan College.

Turn right onto TN 359 North. The road passes under an overpass 0.6 mile later. Powder Branch Road goes to the left. This is the location of the first powder mill west of the Alleghany Mountains. At this same mill, Mary Patton made the powder for the Overmountain Men, as discussed earlier.

It is 1.9 miles to Milligan College, on the left. In 1867, the Buffalo Male and Female Institute was established on this site. In 1875, Dr. Josephus Hopwood of Kentucky became the head of the Buffalo Institute. Seven years later, Hopwood changed the name to Milligan College in honor of his favorite professor in Kentucky. Both Alf and Bob Taylor were students at the Buffalo Institute. Alf lived in a house adjoining the campus.

It is 0.5 mile from the entrance to Milligan College to the intersection where TN 359 turns left. As you turn left on TN 359, Alf Taylor Road is on your left.

Continue on TN 359 for 2.3 miles. The road intersects South Roan Street, where you will turn right. It is 1.6 miles through an industrial area to the Tipton-Haynes Historic Site, on the left.

A spring and cave on this property were located close to an old buffalo trail, making the site an ideal campground for Indians and later for white hunters, traders, and settlers. In 1673, James Needham and Gabriel Arthur, who are believed to have been the first English-speaking traders in Tennessee, camped here. (For more information about Needham and Arthur, see The Overhill Towns Tour, pages 309–10.)

In 1784, the site was purchased by Colonel John Tipton, who built the original home along the Great Stage Road. Tipton played an important role in the military and political activities of early Tennessee. Unfortunately, he is probably best known for his feud with John Sevier over the formation of the State of Franklin. Tipton refused to recognize the State of Franklin’s authority. After Sevier was elected governor of the new state, the feud escalated. In early 1788, Sheriff John Pugh of Jonesborough took a number of Sevier’s slaves under a court order for nonpayment of North Carolina taxes. These slaves were brought to Tipton’s farm. Sevier gathered 150 of his followers and marched to the farm, where about 45 men guarded the slaves. What ensued has been called the Battle of the Lost State of Franklin.

Sevier gave the men thirty minutes to surrender the slaves. Tipton and the sheriff refused and sent for aid, which came in the form of a company of men. Sevier’s band opened fire and drove them back, then laid siege to the house. Firing on both sides resulted in the death of one of Sevier’s men and two on the other side, including the sheriff. Reinforcements arrived and drove Sevier’s men back to Jonesborough in a blinding snowstorm. Two of Sevier’s sons were captured. Tipton wanted to hang them, but Thomas Love convinced him of the rashness of such an act, and the prisoners were released. (For more information about the Tipton-Sevier feud and the State of Franklin, see The Beauty Spot to Nolichucky Tour, pages 68–70.)

In 1839, David Haynes purchased John Tipton’s estate and gave it to his son, Landon Carter Haynes, as a wedding gift. Landon Haynes was the brother of Emmaline Haynes Taylor, mentioned earlier. Haynes was active in politics before the Civil War, but his most visible political years came when he served as a senator for the Confederacy. During the Civil War, the nearby village was named Haynesville in his honor. By 1869, however, the town’s name was changed to Johnson City. When the war ended, Haynes fled to Virginia, losing all his property, including this home.

The Tipton-Haynes Farm has now been restored to its condition during Haynes’s possession. On the homestead, you can see the clearly marked remnants of the old buffalo trail, the cave where hunters and traders camped, and a marker noting Needham and Arthur’s exploration. The farm is open to the public.

From the Tipton-Haynes Historic Site, continue on South Roan Street leading into Johnson City. It is 1.1 miles on South Roan Street to an intersection with University Parkway (U.S. 321). You will see the intersection with I-26 on the right.

Continue 0.3 mile on South Roan Street, where you will see an impressive house on the hill overlooking the street on the right. This mansion was built in 1890. Bob Taylor bought it in 1892 and named it Robin’s Roost. He went from this home to serve his third term as governor. Alf Taylor purchased the mansion in 1900 and lived here until 1903.

Across the street, you’ll see the elaborate entrance to the historic Oaks Castle. Judge Thad Cox started the building of this massive ten-room mansion in 1918. Constructed entirely of native limestone, it features Italian-inspired architecture. Cox, a prominent Democratic leader in the early 1900s, wanted the estate to resemble the Biltmore Estate in Asheville, North Carolina. The mansion’s completion was delayed until 1922 because of shortages of building materials after World War I. Today, the beautifully restored castle is the focal point for a real-estate and medical development.

This ends The First Frontier Tour. If you continue on South Roan Street, you will reach the Johnson City business district. Or you can return to the intersection with University Parkway to travel on U.S. 321 or I-26.