The Rogersville to Kingsport Tour

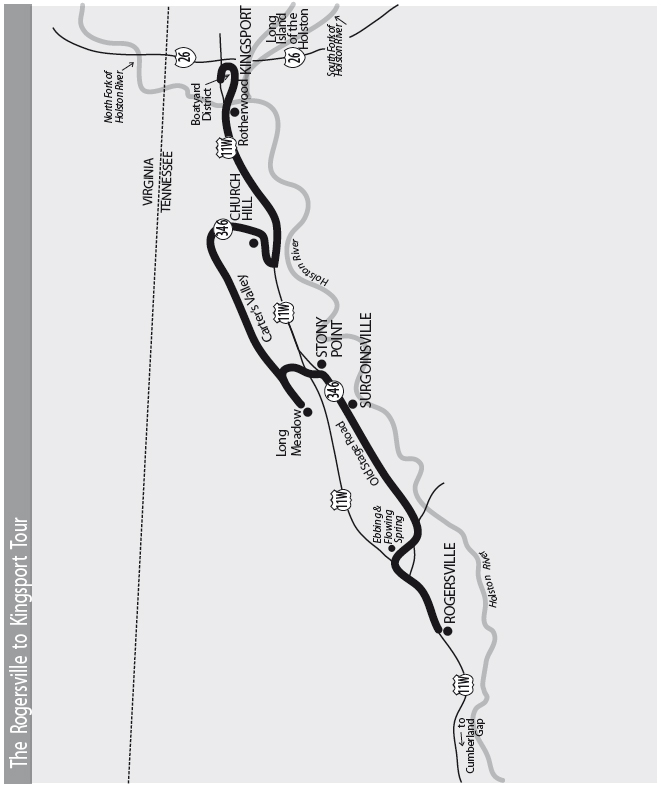

This tour explores the Rogersville historic district. It goes to Ebbing and Flowing Spring and follows the Great Stage Road to Surgoinsville. The tour travels through Carter’s Valley to Church Hill and the outskirts of Kingsport. There, it follows the Holston River through the Old Boatyard District to the Long Island of the Holston before ending at Old Kingsport Presbyterian Church.

Total mileage: approximately 70 miles.

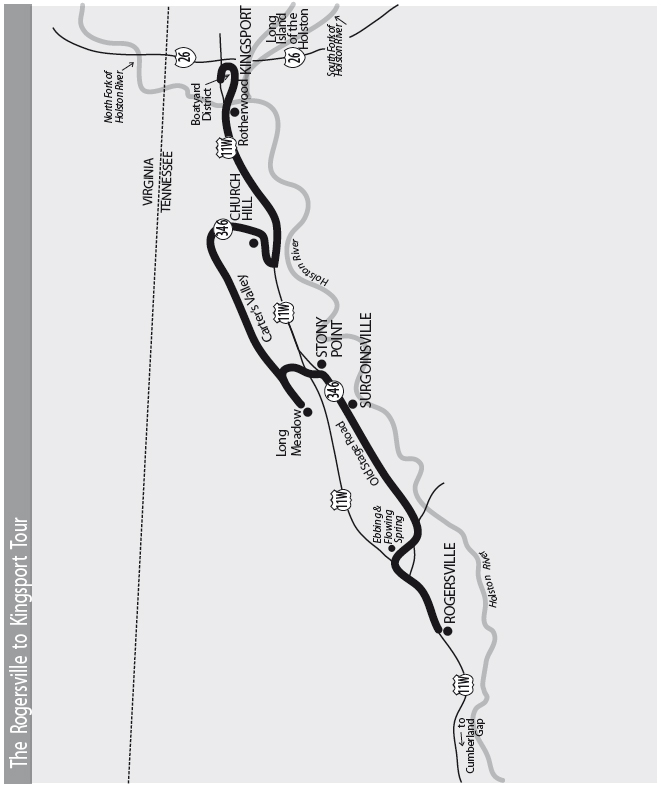

The tour begins at the town square in the center of Rogersville, the county seat of Hawkins County.

One of the earliest settlers in this area was Thomas Amis, who moved here shortly after the Revolutionary War, having received a grant of one thousand acres along Big Creek. Along with a home, Amis built a blacksmith shop, a gristmill, a sawmill, a distillery, and a store. He did a thriving business with the Indians as well as the early white settlers. This was still a pretty wild place when Amis settled here. One source quotes Mary Amis Rogers, Thomas’s daughter, who told of bears that often invaded their yard and devoured the pigs. Mary also said it was not unusual to wake up early in the morning and find Indians sharpening their tomahawks on the family’s grindstone. More information about the Amis House is presented later in this tour.

In the early 1780s, a young Irishman named Joseph Rogers came to the area and worked as a clerk for Thomas Amis. Tradition says he eloped with Mary in 1786, while Amis was off serving in the North Carolina legislature. Although Amis was furious when he learned of the marriage, he soon reconciled himself to it, as evidenced by his wedding present to the newlyweds. He gave them the land that is now the town of Rogersville.

The land was near one of the main wagon routes through the area and also near a good water supply, Crockett Creek, which took its name from some other early settlers—the David Crockett family. In 1777, David Crockett and members of his family were massacred in an Indian raid. As fate would have it, some of the sons of the family were not at home during the raid. One of those sons went on to father another David Crockett, who became the inspiration for Disney’s “King of the Wild Frontier.”

Joseph Rogers built a tavern on the Great Stage Road, which ran between Washington, D.C., and what is now Nashville. In 1789, Rogers and his brother-in-law James Hagan, who had married another Amis sister, applied to the North Carolina legislature to establish a town at what was then known as Hawkins Court House. Commissioners were appointed to lay out thirty acres of land in lots. One of the last acts of the North Carolina General Assembly that affected what is now Tennessee was the naming of Rogersville as the county seat.

In 1791, Rogersville also boasted the first Tennessee newspaper. The Knoxville Gazette appeared on November 5 of that year. It was printed on the second press west of the Alleghanies. The editor, George Roulstone, was apparently waiting for Knoxville to be incorporated as a town and designated the state’s seat of government. Wanting to get publication under way, he went ahead in Rogersville, even though he called his paper the Knoxville Gazette. About a year later, the paper moved to Knoxville.

The second issue of the newspaper carried this interesting quote: “A company going through the wilderness to Cumberland was met on the road by a party of Indians. Upon first sight the men, being seven in number, rode off with the utmost precipitation and left the women, four in number, who were so terrified that they were unable to proceed.”

In 1831, Rogersville was home to another first in the newspaper business—the first paper in the nation expressly advocating the building of railroads. Ironically, the tracks belonging to the Southern Railroad that run through Bulls Gap today were originally planned for Rogersville, but the town fathers voted the railroad’s offer down.

In 1805, another Irishman, John McKinney, came to Rogersville as an attorney representing a client from Philadelphia. While here, he met and married Eliza Ayer, who was visiting her sister in Greeneville. In 1810, McKinney built a brick mansion. Fourteen years later, he began work on McKinney’s Tavern House, located on the town square opposite the courthouse. The East Tennessee stagecoach line ran right through the middle of Rogersville from 1825 to 1855. McKinney’s Tavern became one of the most popular stops along the route.

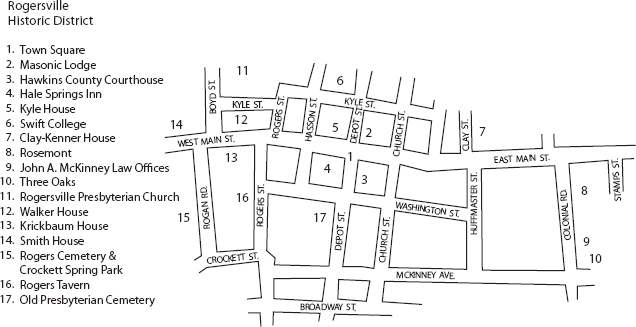

As you view the town square, you will see Hale Springs Inn, formerly McKinney’s Tavern. The building, still striking today, must have been truly impressive by frontier standards. Its size attests to the importance of the Great Stage Road and the number of travelers who used this route.

McKinney hired John Dameron to design the three-story building, which has four chimneys and four fancy dormers on the roof. The porches extending across the front and back were called galleries. McKinney’s Tavern opened to the public late in 1824 and kept that name until 1884.

During the Civil War, the inn served as headquarters for the Union forces holding Rogersville. The wellhouse behind it was used as a stockade for Confederate prisoners. Its walls were covered with wartime graffiti when the structure was torn down in 1940.

When stage traffic was replaced by the railroad, the inn continued to thrive because of the nearby Hale Springs Resort. George Murray operated the resort, where travelers came to enjoy the healing qualities of the mineral springs. Murray’s sister Annie Ross acquired the inn and renamed it Hale Springs Stopover House in 1884. Travelers en route to the resort were met at the train station and stayed overnight at the inn. After breakfast, they were transported by carriage to the resort. The trip took a full day, the travelers arriving in time for supper.

J. B. Murrell, a half-brother of George Murray, purchased the inn in 1903 and operated it for fourteen years as Hale Springs Hotel. During that time, eighteen full-time servants maintained the fifteen rooms and the restaurant.

In 1929, the inn was sold again. The new owner divided the original large rooms into small ones. The fireplaces were sealed, and the original heart-of-pine floors were overlaid with linoleum.

In 1982, a major restoration project was begun. The pine floors were uncovered, the fireplaces restored, and the formal garden replanted. Hale Springs Inn operated as a popular bed-and-breakfast inn but was later closed. Today, the fate of the inn is still up in the air. At this writing, the building is owned by the Rogersville Heritage Association. Construction bids for a major renovation were taken in the spring of 2007.

Across the street from Hale Springs Inn is the Kyle House, built in 1837. This structure served as the Confederate headquarters when southern forces controlled the area. It is said that long after the Civil War ended, local residents would walk only on the side of this street that had belonged to the forces who shared their loyalty.

On the northeast corner of the town square is the oldest Masonic lodge in continuous operation in Tennessee. The lodge was chartered in 1805 and the building constructed in 1839 as the first branch of the Bank of the State of Tennessee. The structure was originally capped by a cupola, which was removed early in the twentieth century following storm damage.

Across the street on the corner of East Main and Depot streets is the Hawkins County Courthouse, built in 1836. Actually the third courthouse in town, it was designed and built by John Dameron. The front stairway, said to be fashioned after Independence Hall in Philadelphia, was removed to make room for more office space in the 1870s. In 1929, the stairways were restored to their original position. However, Dameron’s distinctive cupola was removed and replaced with a New England–style church steeple. The brick columns of the original building still remain. This is the second-oldest courthouse in the state, and the oldest still showing its original outside walls.

Head south on Depot Street. The next intersection is Washington Street. On the right is a historical marker for Old Presbyterian Cemetery, where many of the area’s early settlers are buried. One unusual monument in this cemetery is the urn containing the ashes of Ruth Hale. Ruth was married to Heywood Broun but retained her maiden name. She was the mother of Heywood Hale Broun, a well-known columnist for several New York newspapers from 1911 to 1939. Broun was the most highly respected newspaper essayist of his era.

Ruth Hale left very definite instructions about how her remains were to be handled. Local resident Alice Summers Hale tells the story she heard from her mother of the day Ruth’s relatives awaited the arrival of her ashes by train from New York. These relatives heard the whistle announcing the train, but no one delivered the package. When they called the depot, they learned the ashes had been mistaken for pepper and delivered to the local grocery store.

Safely retrieved, the ashes now rest in an urn on top of the grave of Ruth’s mother.

Continue on Depot Street to the intersection with Broadway. On the right is the old railroad depot. It is now home to the state’s only printing and newspaper museum, which is fitting, since the Knoxville Gazette was first printed in Rogersville. The museum contains several exhibits from a nineteenth-century print shop and originals or photocopies of more than two dozen newspapers printed in this town. It also offers a display of artifacts from the Pressmen’s Home.

During the late 1800s, it was believed that water from mineral springs had great healing properties. Luxurious resorts appeared near natural springs all over the country. One of these was Hale Springs Resort, which was 16 miles northeast of Rogersville.

In 1909, George L. Berry, president of the International Printing Pressmen and Assistants Union, presented information to the union’s annual convention showing that a high percentage of pressroom employees were afflicted with what was then known as consumption. We now call this disease tuberculosis. Berry received authority from the convention to find a healthy location for the union’s headquarters.

A survey at the time showed that the greatest number of people cured of the disease found treatment within a 50-mile radius of Asheville, North Carolina. In August 1909, Berry and an associate, John Geckler, went to Asheville to see if they could find a suitable site. On their way back to their homes in Cincinnati, they dropped by Berry’s boyhood home in the Clinch Valley area of Hawkins County. They missed the last train out of Rogersville on Saturday, and there wasn’t a Sunday train. Someone suggested nearby Hale Springs Resort as a place to spend the weekend.

Berry and Geckler stayed the night there and learned that the resort was up for sale. They took an option on the 519-acre estate that included the land, a partially completed hundred-room hotel, a twelve-room hotel, twenty-three cottages, eight log cabins, a bathhouse, a barn, outbuildings, and an electric power plant.

The union convention approved the purchase in June 1910. Construction of a school where members could learn more skills, and thus earn higher wages than nonunion pressmen, began that October.

The 1911 union convention was held at the new headquarters in Tennessee. The Technical Trade School also opened that year. In 1916, a three-story, thirty-five-bed tuberculosis sanatorium opened. That same year, the powerhouse was rebuilt and a swimming pool was added. The Pressmen’s Home, as it came to be known, also raised livestock and poultry and operated a dairy, a flour mill, a lime kiln for making fertilizer, a cannery, and a pasteurization plant.

During the early Depression years, the union joined WPA workers in building a dam that formed a beautiful lake for the home. In 1926, a memorial chapel was completed, and the home’s total acreage grew to sixteen hundred.

In the 1930s, blasting operations in the area destroyed the flow of sulfur water that had given Hale Springs Resort and the Pressmen’s Home their reputation for curing ills. The home eventually increased its holdings to 5,280 acres, but by 1958, the union began selling its assets and leasing the land. By 1961, the sanatorium closed. In 1967, the union moved its headquarters to Washington, D.C.

The facilities are now abandoned, and the dammed lake has been drained. All that remains to testify to this once-impressive complex are the empty buildings and the still-thriving golf course adjoining the property.

Diagonally across from the depot is the former site of the Rogersville Synodical College campus. This college, a private Presbyterian finishing school for women, was founded in 1850. Its original buildings were destroyed by fire in 1928. However, the enormous boxwoods have survived from those early years.

Turn back down Depot Street, heading downhill. Turn right onto McKinney Avenue and proceed several blocks to the intersection with Colonial Road. Turn left onto Colonial. On the right is Three Oaks, a home built in 1815 by John McKinney, the original owner of Hale Springs Inn. He selected the site because of its fine oak trees and the good water supply from Crockett Spring, which now runs in front of the house. The giant oak tree in the yard is estimated to be more than five hundred years old.

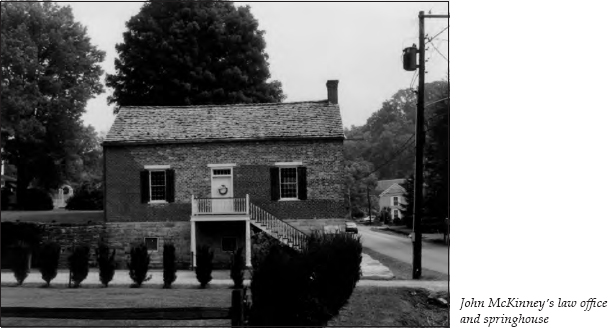

In front of the house is John McKinney’s law office, which also served as a springhouse. The spring that flows in the cut-stone channel beneath these buildings was a source of water for livestock in earlier days.

On the right farther along Colonial is a two-story brick house known as Rosemont. John McKinney built this home in 1842 as a wedding gift for his daughter and John Netherland. Netherland was a brilliant attorney and a Tennessee state senator who ran for governor in 1860 against his cousin, Isham Harris, the leader of the secession movement. Netherland lost the election but remained a loyal supporter of the Union cause.

Susan McKinney Netherland’s garden was well known throughout the area. One source describes how it looked at its height:

On the right an octagonal stand of three shelves was built around a maple tree. On it were fuchsias of many varieties. . . . On the left, between two large apple trees, was a long stand with two tiers of shelves. Here were the geraniums, the pelagorniums, and other distinguished plants. Between the kitchen and the long back porch was a high trellis that acted as a screen. It was covered with roses and woodbine. Wisteria covered the garden gate and also covered the tall cedar tree at its side.

At the corner of Colonial and East Main, turn left onto East Main. On the right on the hill next to the public library is the Clay-Kenner House. John McKinney built this home as a wedding gift for his son, Charles J. McKinney. One story says that Captain Henry Boyle Clay, a grandson of Henry Clay, hid in a secret room in this house after the death of General John Morgan in Greeneville (see The Jonesborough to Greeneville to Bulls Gap Tour, pages 123–25). Captain Clay, a staff officer for General Morgan, escaped the ambush. His daughter, Mary Kenner, was the last owner to reside in this house.

Continue two blocks on Main Street to the corner of Church Street. Turn right onto Church, then left at the next block onto Kyle Street. At the corner of Kyle and Depot streets is what remains of the campus of Swift College.

In 1883, Union Presbyterian Church sent the Reverend William Henderson Franklin to Rogersville to organize a school for Negro girls. The school was named for the Reverend Elijah E. Swift, president of the Board of Missions for Freedmen of the Presbyterian Church. By 1893, Swift Memorial College had a three-story brick administration building and a girls’ dormitory located where the Presbyterian church now stands.

In 1901, the state of Tennessee closed the doors of white colleges to blacks. Maryville College’s board of trustees voted to give twenty-five thousand dollars of the school’s hundred-thousand-dollar endowment to Swift. This fund was held by Union Presbyterian Church. In addition, Mrs. Harry K. Thaw gave a thousand dollars to build a boys’ dormitory in 1903; that dormitory was destroyed by fire in 1926 and replaced in 1931. In 1904, Swift grew from a high school to include four years of college. In 1913, two wings were added to the main building.

In 1929, county schoolteachers began to be paid according to the number of college credits the state board of education would grant them from their alma maters. At that point, the board allowed only one year’s credit for four years’ attendance at Swift. In 1930, Swift became a junior college and followed state standards. In the mid-1950s, the school moved to Jackson, Mississippi.

During the school’s tenure in Rogersville, the students were not allowed out of their dorms at night. Neither were they allowed to go downtown without being accompanied by a house parent. Usually, they gave the house parent a list of what they needed, and the house parent made the trip downtown for them.

Dr. Franklin served as president of the school until 1926. He and his wife, Laura, are buried in a plot on top of the hill to the right. Those graves and the boys’ dormitory, located on the hill near the graves, are the only remains of the college.

Continue on Kyle Street until it makes a ninety-degree left turn. You are now on Rogers Street. Ahead are Rogersville Presbyterian Church and its cemetery. The church was founded in 1805, and the current structure was built in 1840. The church’s balcony retains its original pews, where family servants once worshiped. The original cemetery for this church was discussed earlier in the tour.

Continue straight on Rogers Street instead of following Kyle as it turns right in front of the church. At the next corner, turn right onto West Main Street. On the right at 317 West Main is the Walker House, the home of the daughter of Joseph and Mary Amis Rogers, the founders of Rogersville.

Across the street at 324 West Main is the Krickbaum House, bought by John McKinney for another of his daughters, Sarah Heiskell. The English boxwood hedge on the left is thought to be over two hundred years old.

On the right in the next block at 413 West Main is the Smith House. Built in 1824 by William Kenner, it was later converted into an inn on the Great Stage Road. It was operated by Absalom Kyle, whose granddaughter renovated the house in 1935.

Turn left onto Rogan Road just before the Smith House. You will see a historical marker for Rogers Cemetery on the corner. The cemetery is on the right a few yards south. Joseph and Mary Rogers are buried here, as are the grandparents of Davy Crockett. The area around Rogers Cemetery has been converted into the beautiful Crockett Spring Park.

Continue to Crockett Street and turn left. Turn left onto Rogers Street at the next corner. On the left halfway up the block at 205 South Rogers is the former Rogers Tavern, the inn built by Joseph Rogers in 1786. The original log-and-stone structure is under the clapboard siding. Rogers Tavern is now owned by the Rogersville Heritage Association, which plans to restore it and turn it into a living museum.

An amusing anecdote tells about an early visitor to Rogers Tavern. One day, a stranger came to the public room of the tavern shortly before supper and asked for a room. The landlady showed him to a room that he could share with two other gentlemen. The stranger then made insolent remarks about a town that could not offer a gentleman a separate room. One of the other guests at the inn overheard the remarks and seized the stranger by the arm, saying, “Come with me, sir, I’ll find a separate room and bed for you.” The guest ushered the stranger to the corncrib out back, opened the door, and commanded him to climb in. This guest had a rather insistent manner, so the stranger complied. Once locked inside, the stranger was asked if he was willing to apologize and accept the first-offered accommodations. He agreed. The guest who requested the apology was none other than Andrew Jackson—or so the story says.

Continue on Rogers Street for a block, then turn right onto West Main Street. It is a block and a half to Hale Springs Inn, where this tour of the historic district began.

Continue straight on Main Street, heading east. When you reach the intersection with Burem Road/TN 347, it is 0.4 mile to a roadside park. At the roadside park, you will see a historical marker for Chisholm’s Ford, located 3.5 miles southeast on the Holston River. In the center of the park stands a stone milestone marker. When U.S. 11W was dedicated in 1922, this was one of only five milestone markers placed on the Lee Highway, which ran from Washington, D.C., to San Diego, California. The south face of the marker used to have a bronze frieze showing a stagecoach pulled by two teams of galloping horses. The north face reads, “This monument marks the route of the old East Tennessee stagecoach line.” U.S. 11W has been rerouted 0.6 mile north, but the monument still stands in its original location.

At the park, stay on the road going right. It is 0.7 mile to the turnoff for Ebbing and Flowing Spring Road; no road signs are posted, so watch carefully. Turn right. Ebbing and Flowing Spring Road is a narrow, paved country road. It is 1.1 miles to where the creek literally flows across the road. On the left is the famous Ebbing and Flowing Spring.

When the level of this spring reaches its lowest point, the water begins to flow rapidly; it continues flowing rapidly until it reaches its highest point. For the next two and a half hours, it gradually recedes. Then the cycle repeats. The spring is known to have followed this pattern for at least two centuries. It was part of Thomas Amis’s original land grant, on which it was identified as “the sinking spring.”

On the hill to the left of the spring are Ebbing and Flowing United Methodist Church and Ebbing and Flowing School. The exact date of the schoolhouse’s construction is unknown, but it is believed to date from before the 1800s. The school operated until the 1950s. Miss Mary Beal, one of Amis’s descendants, taught here. An amusing story is told about a questionnaire from the state that asked schools if they had central heating. “Almost” was Miss Beal’s reply. She went on to add that the potbelly stove wasn’t quite in the middle of the one-room school.

In the cemetery adjoining the church is a gravestone that was featured in Robert Ripley’s Believe It or Not. It reads,

Remember me as you pass by

As are you now so once was I.

As I am now, you soon shall be,

Prepare for death and follow me.

The original inscription ended there, but someone has since added another verse, which reads,

To follow you I would not be content

Unless I knew which way you went.

Unfortunately, the area around the church, cemetery, and school is now posted against trespassers.

Continue past the spring for 0.3 mile to an unmarked intersection. Go straight. You are on Bear Hollow Road. Big Creek Fort, one of the original frontier forts, was located near this area. It was built in 1777 by James Robertson, who was serving as superintendent of Indian affairs for North Carolina. Robertson resigned his position in December 1778. The following spring, he led an expedition of settlers that will be described later in this tour. (For more about James Robertson, see The First Frontier Tour, pages 4–5.)

About 1780, Indians besieged a group of settlers at Big Creek Fort. Joab Mitchell volunteered to attempt a trip across the nearby Holston River to bring back salt to the fort. Ambushed and mortally wounded, he galloped his horse to the fort nonetheless. He died inside the fort, and this area has since been called Mitchell’s Hollow.

It was also at this fort that Evan Shelby gathered somewhere between three hundred and nine hundred men in April 1779. These forces sent runners out to warn friendly Indians that patriot troops were coming. On April 10, a flotilla went from Big Creek down the Holston and Tennessee rivers to the mouth of Chickamauga Creek. The early-spring rains made the trip go so quickly that the frontiersmen were able to catch the Chickamauga forces off-guard. The militia spent two weeks destroying all eleven Chickamauga villages. (The events that led to this expedition will be discussed later in this tour. For more about Evan Shelby, see The Bristol to Blountville to Jonesborough Tour, page 73. For more about the Chickamaugas, see The Trail of Tears Tour, pages 344–46.)

As you travel along Bear Hollow Road, Big Creek is on the left. You will see the remains of a rock dam. This dam formerly supplied power for a gristmill and a sawmill built by Thomas Amis. The foundations of the mills are still visible.

It can’t be seen from this road, but the Amis House sits on the hillside on the right. Although covered with white clapboards today, the original house with its eighteen-inch-thick stone walls is still intact. Because dealings with the Indians were still volatile when the house was built in 1780, it resembles a fortress in some respects. The upper half-story features portholes instead of windows. The doors are of double thickness, the outside panels running vertically and the inside panels horizontally. Amis raised his fourteen children in this house.

Continue on Bear Hollow Road for 0.1 mile to the intersection. A water-treatment facility is on the left and a small roadside park on the right. If you wish to glimpse the Amis property, take a short detour of 0.1 mile to your right. The house is set back from the road on a hillside on the right, but you can see part of the farm. The front of the house faces away from the road.

If you opt not to take the short detour to the Amis House, turn left and head east. It is 1 mile to the turnoff for Old Stage Coach Road. Turn left onto this road. If you reach the bridge across the Holston River, you’ve gone too far. As the name implies, this route follows that of the Great Stage Road.

This area was the scene of the Big Creek skirmish on November 6, 1863. Confederate cavalry brigades under General William “Grumble” Jones were coming from Rogersville, while Colonel Henry Giltner’s forces were approaching from Surgoinsville. The Federal force between them was the Second Tennessee Mounted Infantry, along with a detachment of the Seventh Ohio Cavalry. The Confederate forces were in the area to keep Union attention off General James Longstreet, who was advancing from Chattanooga to Knoxville. After an hour of sharp conflict, Colonel Giltner reported that his forces had captured the Union battery and 450 of the enemy. He reported his losses as one killed and three wounded.

It is 3.7 miles from the turnoff onto Old Stage Coach Road to the intersection with TN 346. On the right is a beautiful home built around 1790 by Jacob Miller. This home was an overnight stopping place for travelers on the stagecoach route. Nearby was a structure built in 1795 that housed a general store and post office. This structure, a distribution point for surrounding country stores, was well known in the area as “the Yellow Store” because of its color. A tanyard, a blacksmith shop, and a gristmill all operated in connection with the store, which was destroyed by a tornado that swept through the area in 1955.

At the intersection is a historical marker for Thomas Gibbons, who settled near here in 1778. His home served as the location of various court sessions, including one for the State of Franklin from 1785 to 1787. It also served as the first county court for Hawkins County in 1787.

Turn right at the intersection onto TN 346. It is 2 miles to the community of Surgoinsville. Continue on TN 346 through town. It is 2.6 miles to Fudge Farm, a good example of the type of log-building complex used for agriculture in the first half of the nineteenth century. Fudge Farm is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

It is 0.3 mile to Stony Point, located on the hill on the right. In the late 1700s, William Armstrong constructed what was supposedly the first brick house in Hawkins County. Later, a separate home of red brick was built to the north, and subsequent generations connected the two structures with a passageway of clapboards. Although this house was not operated as an inn, its location on the Great Stage Road made it a favorite stopping place for travelers.

One such traveler was Louis-Philippe, the duke of Orleans. After the overthrow of his father during the French Revolution, the duke was forced to flee France. His two younger brothers were released to him under the condition that they would all come to America, which they did in 1796. Frenchmen loyal to the monarchy hoped the princes would remain safe in America until the revolution ran its course. They met with President George Washington in Philadelphia, where Washington prepared them an itinerary for a journey through “the western country.”

In 1797, a party of four departed on horseback down the Shenandoah Valley and through Tennessee on the way to New Orleans. The duke traveled as Mr. Orleans. His journal of the trip survives. In it, he makes his growing distaste for the lack of culinary diversity quite clear. He was especially disgusted with the hoecakes that seemed to be everywhere. When the travelers arrived at the home of a Mr. Smith, where they had been promised a “square meal,” they left hurriedly when they discovered more cornbread. They then traveled 35 miles to a Mr. Armstrong’s home, where they finally received a good supper—though they had to sleep three to a bed. After Louis-Philippe became the king of France in 1830, he jokingly asked the American ambassador, who was from Tennessee, if people still slept “three to a bed” in his state. (For more about Louis-Philippe’s journey, see The Maryville Tour, pages 283–84, and The Overhill Towns Tour, page 308.)

Turn left at the intersection just past Stony Point; there is no stop sign at this intersection. It is 0.4 mile to the intersection with the four-lane U.S. 11W. Go straight across U.S. 11W, following Stony Point Road. It is 0.2 mile to New Providence Presbyterian Church.

This congregation, organized in 1780 by Samuel Doak and Charles Cummings, is one of the three oldest in Tennessee. The present brick structure was built in 1893. The oldest marked grave in the adjoining cemetery is that of Jesse Maxwell, who died on June 13, 1816. For years, the pastors of New Providence were also the teachers at the nearby school, later known as Maxwell Academy. The building across the road, constructed in 1901, housed the school. Maxwell Academy was one of the earliest schools in Hawkins County.

Travel 1.5 miles on Stony Point Road to the intersection with Carter’s Valley Road. Turn left. It is 1.8 miles to Long Meadow Farm, on the right.

In 1762, William Young staked a claim to a large tract of land in what is now Carter’s Valley. He then traveled to Virginia to bring back his wife, Caroline. When he returned to Carter’s Valley, he discovered that another man had claimed his land. Tradition says a fistfight left William Young the owner of the tract.

In 1763, the couple’s son John was born. He was the first white child born in Hawkins County.

William subsequently built a huge log room that still serves as the nucleus of the present home, known as Long Meadow.

When the Young family left Scotland, they reportedly brought slips of boxwood with them. They then planted cuts wherever they lived. Caroline Young supposedly planted the cuts that grew to be one of the finest collections of English boxwood in Tennessee. Unfortunately, the winter of 1985 killed them. The boxwoods on the site of the former Rogersville Synodical College were plantings taken from Long Meadow.

After viewing Long Meadow, retrace your route to the intersection of Stony Point Road and Carter’s Valley Road. Continue straight on Carter’s Valley Road. Carter’s Valley was named for John Carter, who, along with his partner, William Parker, established a store here in 1770. They hoped to supply travelers coming down the Holston River and to trade with the Indians. Unfortunately, the store was burned during an Indian raid, and John Carter moved his family to a new settlement near what is now Elizabethton (see The First Frontier Tour, pages 11–12).

When the treaty was signed for Richard Henderson’s Transylvania Purchase, Carter and his new partner, Robert Lucas, were compensated for the loss with all the lands in Carter’s Valley. Lucas advanced a small sum in payment for this grant. The states of Virginia and North Carolina later refused to recognize the treaty but did compensate the powerful men involved. In 1783, North Carolina gave John Carter and Robert Lucas ten thousand acres of land in the Clinch River Valley.

Travel 7.5 miles along the scenic Carter’s Valley Road. Several prosperous farms are located here, their stately farmhouses dating from the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. At the intersection with TN 346, turn right, heading into Church Hill. It is 2.5 miles to Jaycee Park, on the right as you come into town. You will pass over Alexander Creek, where Patterson’s Mill once stood.

In 1775, Robert Patterson moved into the area along Alexander Creek and constructed a fort for protection. Soon afterward, he built a mill as well.

After the signing of the treaty at Sycamore Shoals in 1775, Dragging Canoe led a faction of Indians who were dissatisfied with the agreement. One of the groups of Cherokees attacking along the frontier in 1776 was led by The Raven. His force concentrated on the settlers in Carter’s Valley. The fort at Patterson’s Mill was one of the locations where area settlers sought refuge during these hostilities. More information about the Cherokee raids will be presented later in this chapter.

The historic mill stood for two hundred years until it was destroyed by arson on Halloween night in 1975.

Continue straight for 0.6 mile to U.S. 11W. Turn left onto U.S. 11W, heading toward Kingsport. It is 3.6 miles to the Allandale Mansion, on the left.

This mansion was built by Harvey and Ruth Brooks in 1950. The portico, the hand-carved cypress pillars, and the staircase were brought from the home of C. B. Atkins in Knoxville. They are all over one hundred years old. An old frame home on the premises when the Brookses purchased the property was incorporated into the kitchen wing. This old home was built by Robert Glen Netherland and his wife, Adenaida “Ida” Phipps Netherland, soon after they married in 1851. Netherland was the grandson of Richard Netherland, who owned the Netherland Inn. Ida was the daughter of Joshua Phipps, the owner of Rotherwood Plantation. More information about both places is presented later in this tour. The Allandale Mansion is open to the public for tours; an admission fee is charged. It is also available for private parties.

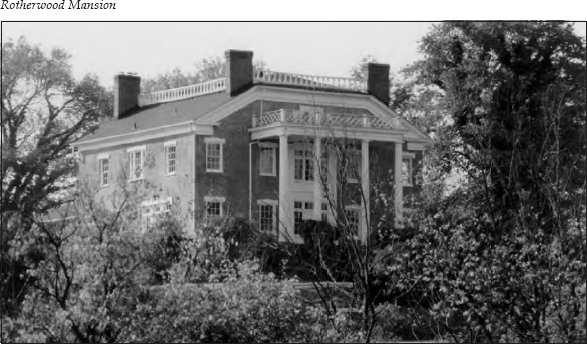

It is 0.3 mile to a stoplight where Netherland Inn Road goes off to the right. Turn onto that road, following the signs for Bays Mountain State Park. It is 0.4 mile to Rotherwood Mansion, on the right just before the river.

In 1789, David Ross came from Virginia and built the Ross Agency (or Trading Post) along what was then the Great Indian War Path. This route evolved into the Great Wagon Road and later the Great Stage Road. From 1789 to 1795, Ross developed a small community known as Ross Ironworks. Though he never actually lived in the community, he sent agents to operate his many enterprises in the area. When he died in 1817, he left this land to his youngest son, Frederick A. Ross.

When Frederick Ross came to manage his new estate, he decided to build his own bridge across the North Fork of the Holston River, rather than wait for the legislature to order one. In so doing, he rerouted the Great Stage Road right by his new home. He later wrote in his autobiography, “Besides this decision, I also determined to build a fine house on a beautiful eminence overlooking, from the west bank, the river and my new road. Both undertakings were begun in ten days. The bridge was completed in a few months and the house without delay.”

Ross hired Tennessee’s first architect, Thomas Hope, to design his home, which he named Rotherwood. Ross loved the works of Sir Walter Scott and chose Rotherwood because it was the name of Cedric the Saxon’s home in Ivanhoe. The first Rotherwood was begun in 1818 and finished in 1820. Unfortunately, it was destroyed by fire in 1865.

Well before the blaze that destroyed the first Rotherwood, Ross built a second home nearby. It is this home that survives today as Rotherwood Mansion. The earliest portion of the building faced north. At one time, two separately roofed, parallel buildings stood here. A central hallway between the two joined them to comprise one large mansion. In the 1840s, Ross made additions and improvements to the second Rotherwood for his eldest child, Rowena—named for Scott’s Lady Rowena—who was to be married. But tragedy struck the night before the wedding, when the young groom-to-be drowned while fishing in the Holston River.

Ordained a Presbyterian minister in 1825, Ross spent most of his life at that profession. But because of his wealth, he also had to be a businessman. One of his first ventures was to invest in the silkworm business. He wrote,

The only thing I ever had a fancy for in the way of business was the silk culture. I took a wonderful fancy to it and thought I was going to be a benefactor to East Tennessee. I planted the white mulberry, and then the morus multicaules [sic]. I built me a huge cocoonery and got me French reels and made the raw silk and induced many of the farmers to raise and sell to me the cocoons. . . . For several summers I wore a suit of silk woven in the neighborhood and certainly it was the most enduring substance I ever had as my raiment.

By 1847, Ross’s unprofitable investment in a cotton factory he built on the riverbank near his home forced him to sell much of his estate. He sold nineteen hundred acres of his plantation, including the present Rotherwood Mansion, to Joshua Phipps, who made vast improvements on the house.

Near the mansion was the famous Rotherwood Elm. When Dr. Thomas Walker explored this region on March 31, 1750, he recorded in his journal, “We kept down Reedy Creek to Holston where we measured an elm, twenty-five feet round three feet from the ground.” Daniel Boone is said to have camped under this tree on one of his journeys into Kentucky. The Rotherwood Elm later died of disease.

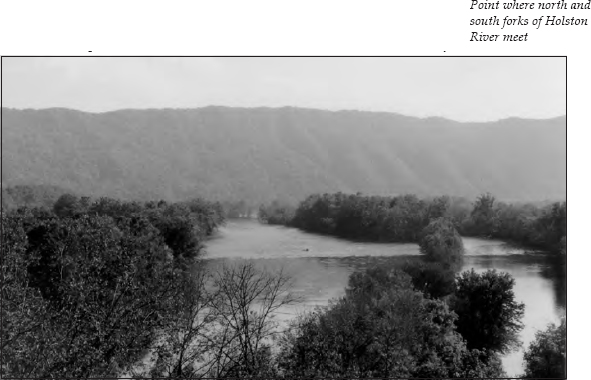

Continue across the bridge. After 0.9 mile, take a right, following the sign to Boatyard Riverfront Park. This loop approaches the point where the North and South forks of the Holston River come together. The park is part of the Boatyard Historic District of Kingsport.

This whole area is steeped in history. The earliest white man’s record was Dr. Walker’s journal, mentioned above. (For more about Walker’s journey, see The Norris to Cumberland Gap to Oak Ridge Tour, pages 179–80.)

The Indians, of course, had known about the region for years, since the Great Indian War Path and its tributary, the Warrior’s Path, ran through it. Originally associated with the prehistoric migrations of buffalo herds, the path extended from the Creek country in Alabama and Georgia north to the island in the middle of the Holston River. Near the island, it split into several branches. The westward branch passed through the Cumberland Gap into Kentucky.

Ancient Indian tribes also lived on the 3.5-mile-long island in the Holston River. But by the time the Cherokees controlled the area, the island had become a sacred place of refuge where nothing was killed. It was called the Great Island or Peace Island, since the Cherokees used it for talks and treaties with other tribes. By the time the white man arrived, it was known as the Long Island of the Holston. According to the Virginia Council, it was considered “a place of general rendezvous” for colonial and Revolutionary War militias.

After the massacre at Fort Loudoun in 1759 (see The Overhill Towns Tour, pages 315–19), settlers along the frontier asked the Virginia government for assistance. In 1761, the Virginia militia started from Chilhowie, Virginia, on an expedition to cut a road for transporting supplies to the Tanasi country. Several hundred axmen led the expedition, clearing what became known as the Island Road. Behind them came packhorses, wagons, and cannons. When they reached the Long Island, they constructed a fort nearly opposite its east end. Fort Robinson was the second fort built in what eventually became the state of Tennessee.

By November 1761, the Cherokees were ready to sue for peace. Two treaties were negotiated to end the hostilities—one in South Carolina, the second at Fort Robinson. Four hundred Cherokees came to the fort with Attakullakulla, whose nickname was “Little Carpenter.” After the treaty’s signing, the Cherokees requested that an ambassador from the Virginia militia return with them to their towns to explain the treaty and make friends with their people. Two volunteers, Lieutenant Henry Timberlake and Sergeant Thomas Sumter (who later became a general in the Revolutionary War), and an interpreter named John McCormack spent several months with the Cherokees.

Timberlake’s memoirs of the journey have survived. The party started out in November, when the Holston River was at its low stage. Almost immediately, their boat lodged on a sand bar. From that time, the journey was interrupted by constant bouts of pushing, pulling, heaving, and wading. The men had only two guns with them, and it wasn’t long before the firing apparatus of one was broken and the other was lost in the river. They were near starvation when Timberlake fixed the broken gun. McCormack was able to kill a bear, on which they subsisted for the rest of the trip. The river froze, and the men had to break their way through the ice. When the thaw came, they made better time.

Upon reaching Indian territory, they were escorted to Chota, where the peace articles were read. Timberlake smoked so much tobacco at the ceremony that he almost collapsed from nausea. He wrote about his welcome to the town of Cheulah: “This violent exercise, accompanied by the band of musick, and a loud yell from the mob, lasted about a minute, when the head-man waving his sword over my head, struck it into the ground, about two inches from my left foot; then directing himself to me, made a short discourse (which my interpreter told me was only to bid me a hearty welcome) and presented me with a string of beads.”

After a stay of a few months, Timberlake returned to Williamsburg, Virginia, with an entourage of chiefs and advisers, whose entertainment presented a problem for the governor. From there, Timberlake took Chief Ostenaco and two warriors to London, where they created quite a sensation. The poet Oliver Goldsmith waited a long time for the privilege of seeing Ostenaco. When Goldsmith was finally admitted, the chief seized him and embraced him with such cordial intimacy that the poet found his cheeks covered with vermilion. Sir Joshua Reynolds painted portraits of the warriors, and they were granted an audience with the king. Timberlake, however, never received reimbursement for the personal expenses he incurred in promoting and carrying out the visit. He published his memoirs in an effort to recoup his loss, but he died before they were released in 1765.

One result of the treaty of 1761 was the complete evacuation of Fort Robinson. Soon after the signing, the militia left, and the fort was never reoccupied.

Also in 1761, Gilbert Christian made his first attempt to settle in what became the Boatyard District. He returned in 1772, but it wasn’t until the Transylvania Purchase in 1775 that he established his permanent plantation on Reedy Creek. (For more information about the Transylvania Purchase, see The First Frontier Tour, pages 5–6.)

Also in 1775, Daniel Boone gathered a group of axmen and started westward along what became the Wilderness Road to settle Richard Henderson’s new claims in Kentucky. But Henderson’s Transylvania Purchase also brought a renewal of Cherokee hostilities; at the treaty-signing ceremonies at Sycamore Shoals, Dragging Canoe, the son of Attakullakulla, had warned that the acquisition would prove a dark and bloody ground.

Hostilities were at a lull until the coming of the Revolutionary War. British authorities, who had worked hard to keep the settlers from crossing treaty boundaries, no longer restrained the faction of eager warriors led by Dragging Canoe. In fact, it was in the British interest to supply munitions and make the Indians part of a greater strategy.

In 1776, Nancy Ward sent a white trader named Isaac Thomas to warn settlers along the frontier that the Cherokees planned to attack. In July, forces under Dragging Canoe, The Raven, and Abraham of Chilhowee converged on the territory. Dragging Canoe struck the settlements north of the Holston. Abraham moved on the Nolichucky and Watauga settlements, and The Raven mopped up Carter’s Valley.

Warned by scouts, the frontier forces came out to meet Dragging Canoe on July 20, 1776, at what became known as the Battle of Long Island Flats. The frontier group surprised a small party of Indians, who fled in haste. Since it was late in the afternoon, the decision was made to return to the fort. Some of the frontiersmen challenged this, and while they were arguing with their leaders, scouts brought news that a considerable body of Indians, misled into thinking the frontiersmen were retreating, was approaching rapidly from the rear.

The Indians came running headlong, led by Dragging Canoe himself. They ran right into the frontiersmen’s fire, and a short fight at close quarters ensued. Dragging Canoe was badly wounded in the thigh and had to be carried off the battlefield. The Cherokees fled in confusion.

When Abraham of Chilhowee heard about the defeat, he lifted his siege of Fort Caswell (see The First Frontier Tour, page 7). Dragging Canoe never tried to fight a conventional war again. He fell back on guerrilla warfare, and bands of Cherokee raiders continued to trouble the settlements.

The Virginia Committee of Safety then gave the order to erect a frontier fort large enough to garrison two thousand men. That fort, built near the site of the old Fort Robinson, was completed by September 1776. It covered nearly three acres of ground, with three sides enclosed. The fourth side was the high riverbank. Fort Patrick Henry, as it was called, was under the command of Colonel William Christian. Christian had three lieutenant colonels, three majors, forty captains, two chaplains, three surgeons and surgeon’s assistants, a drum major, ten drummers, ten fifers, five armorers, horses for packs and men, 6,560 head of cattle, and seventy thousand pounds of flour.

On September 22, this army paraded around Fort Patrick Henry and on to an expedition against the Cherokee Overhill Towns. The Cherokees, torn apart by factional squabbling and demoralized by their recent defeat, fled. Christian occupied all the towns without a battle. He burned the notably hostile towns and spared sacred Chota, the home of Attakullakulla and Nancy Ward.

Before leaving the Overhill territory, Colonel Christian posted a reward of one hundred pounds for Dragging Canoe, dead or alive. But Dragging Canoe fled to the region near what is now Chattanooga. There, he was joined by Tory refugees, discontented members of other tribes, renegade whites, and escaped Negroes in such numbers that they were numerically stronger than the Cherokee Nation itself. Because of their location near Chickamauga Creek, these people were called the Chickamaugas.

Nathaniel Gist was sent by General George Washington to the Long Island to parley with the Cherokees. He arrived in March 1777 and dispatched runners to invite the chiefs to a council on the island.

Among the chiefs who came to the council were Old Tassel, Oconastota, and Attakullakulla. The talks were about to begin when an unknown white man killed an Indian brave named Big Bullet. The angry commissioners offered a six-hundred-dollar reward for the capture of the murderer, but he was never found. After the Indians were calmed by presents “with which to cover the grave of the slain warrior,” the conference continued.

The group signed the Long Island of the Holston Peace Treaty in July. The Cherokees formally gave up all the land they had ceded to Jacob Brown and the Wataugans two years earlier, plus more. But they reserved their beloved island for Nathaniel Gist. The treaty contained the following memorandum: “That Colonel Gist might sit down upon Long Island when he pleased as it belonged to him to hold good talks on.” Some sources say Colonel Gist later fathered George Gist, better known as Sequoyah, the inventor of the Cherokee alphabet. Gist rejoined Washington’s army and did not use the island. But Joseph Martin, the newly appointed Indian agent, established a trading post on the Long Island and lived here with his wife, Betsy, a daughter of Nancy Ward, for over a decade.

Dragging Canoe was not finished. He continued to plague the frontier. During one of his raids, David Crockett and his wife were killed at Crockett Creek. By April 1779, Evan Shelby and his force were tired of these attacks and made their trip from the fort at Big Creek, described earlier in this tour. Although the destruction of the Chickamauga towns was a severe blow to Dragging Canoe, he just moved farther down the Tennessee River and established five new towns alongside or below the breaks known as “the Big Suck,” thereby preventing surprise attacks from the water. (For more information about Dragging Canoe, see The Trail of Tears Tour, pages 344–46.)

In November 1779, James Robertson, who had recently resigned as superintendent of Indian affairs, joined John Donelson as a leader of a new enterprise for Richard Henderson. The plan called for Robertson to lead a group of single men, older male children, skilled hunters, livestock, and packhorses by land to a region near the southern bend of the Cumberland River commonly called Big Salt Lick. Donelson was to take the women, servants, younger children, and household furnishings by water.

Donelson’s party left Fort Patrick Henry on December 22, 1779, with thirty flatboats built in the nearby boatyard. But the party floated only a short distance before it was forced to postpone the voyage for two months until the water rose.

Donelson wrote an account of his exploits entitled Journal of a Voyage, Intended by God’s Permission, the Good Boat Adventure, from Fort Patrick Henry, on the Holston River, to the French Salt Springs on the Cumberland River, Kept by John Donelson. In his book The Tennessee: The Old River, Donald Davidson writes, “Historians pause reverently when they come to the Donelson journal. Their gift for exegesis and summary goes to pieces, and they content themselves with verbatim quotation and little comment.” That said, here are a few passages:

Wednesday, [March] 8th— . . . Proceeded down to an Indian village, which was inhabited. . . . They invited us to “come ashore,” called us brothers, and showed other signs of friendship. . . . [They] sailed with us for some time, and [told] us that we had passed all the [Chickamauga villages] and were out of danger. We had not gone far until we had come in sight of another town. Here they again invited us to come on shore . . . [and] told us that “their side of the river was better for boats to pass.”

However, this was a setup. Indians concealed along the shore attacked the boats when they came too close. Here, Donelson describes the plight of a man named Stuart who had agreed to have his boat, carrying twenty-eight people, quarantined from the rest:

His family being diseased with the small-pox, it was agreed upon between him and the company that he should keep at some distance in the rear, for fear of the infection spreading. . . . After we had passed the town, the Indians having now collected to a considerable number, observing his helpless situation, singled off from the rest of the fleet, intercepted him, killed and took prisoners the whole crew. . . . Their cries were distinctly heard by those boats in the rear. . . . We were now arrived at the place called the Whirl or Suck. . . . The canoe was here overturned. . . . The company . . . landed on a northern shore, at a level spot . . . when the Indians, to our astonishment, appeared immediately over us on the opposite cliffs, and commenced firing down upon us. . . . Jenning’s boat is missing.

Jennings later caught up with the main party and told the story of what had happened to him, here related by Donelson:

Friday, 10th—[When the] Indians discovered [Jennings’s1 situation they turned their whole attention to him. . . . He ordered his wife, a son nearly grown, a young man who accompanied them, and his two negroes, to throw all his goods into the river. . . . His son, the young man and the negro man jumped out of the boat and left them. . . . Mrs. Jennings, however, and the negro woman succeeded in unloading the boat, but chiefly by the exertions of Mrs. Jennings, who got out of the boat, and shoved her off; but was near falling a victim to her own intrepidity, on account of the boat starting suddenly as soon as loosened from the rock. . . . Mrs. Peyton, who was the night before delivered of an infant, which was unfortunately killed in the hurry and confusion consequent upon such a disaster, assisted them, being frequently exposed to wet and cold then and afterwards, and that her health appears to be good at this time. . . . Their clothes were very much cut with bullets, especially Mrs. Jennings.

Sunday, 12th—We ran through the shoals before night. When we approached them they had a dreadful appearance to those who had never seen them before. The water being high made a terrible roaring, which could be heard at some distance among the drift-wood heaped frightfully upon the points of the islands, the current running in every possible direction. Here we did not know how soon we should be dashed to pieces. . . . We passed it in about three hours.

Wednesday, 15th—The river is very high and the current rapid, our boats not constructed for the purpose of stemming a rapid stream, our provision exhausted, the crews almost worn down with hunger and fatigue, and know not what distance we have to go, or what time it will take us to our place of destination.

Despite all these hardships, the group arrived at Big Salt Lick on April 24, 1780. The exact number in the party at that point is unknown, since Donelson recorded the names of only heads of families. Big Salt Lick eventually became the city of Nashville, obviously founded by hearty stock.

Donelson moved once again, this time to Kentucky. After he was killed by Indians there, his widow returned to Nashville. Andrew Jackson boarded with Mrs. Donelson when he came to town. When Mrs. Donelson’s daughter Rachel had problems with her husband, she moved to Nashville to live with her mother. There, she met Jackson, who became her second husband. Because Rachel’s first marriage was not officially annulled before her wedding with Jackson was performed, Jackson fought many duels during his life to defend her honor. But she remained his beloved Rachel until her death in 1828 at the age of sixty-one.

Meanwhile, back at the site where this adventure began, Gilbert Christian built his boatyard into a large enterprise. By 1802, the town of Christianville was founded.

William King, who owned the saltworks in nearby Saltville, Virginia, built King’s Boatyard and organized a freight company. Soon, several freight companies made the boatyard their headquarters for navigation on the Holston-Tennessee river system.

King built dwellings and boardinghouses for his workmen, who left their farms and moved to Christianville during the late fall and winter to load boats. He also constructed warehouses, a counting house, wharves, a smokehouse, and a stable. Products were shipped from East Tennessee and southwestern Virginia to Christianville, where they were carried on flatboats downriver to the Cumberland, Ohio, and Mississippi rivers.

After King died in 1808, his estate ran into financial difficulty. In 1818, the King’s Boatyard property was sold at a sheriff’s sale. Richard Netherland bought what a flier advertising the sale called “the elegant dwelling house” and immediately procured a stage contract. He then established a beautiful three-story building as an inn and tavern on the new Great Stage Road. Netherland’s wife, Margaret Woods, and her sisters had by then inherited the Long Island of the Holston. Since the Cherokees claimed the island, a firm title had not been secured until 1806-7. By 1810, the Netherlands had built a large brick home on the island and developed a plantation.

Also in 1818, Frederick A. Ross laid out a town on the western boundary of Christianville. He called it Rossville, of course. The Boatyard, as it was known, then became a major mail and passenger stage stop, and the Netherland Inn prospered.

Now that you know the history, you can better enjoy Boatyard Riverfront Park, at the confluence of the North and South forks of the Holston River. At the park, you will see a stone monument commemorating the Battle of Kingsport, the area’s only real skirmish during the Civil War. On December 13, 1864, approximately three hundred Confederate cavalrymen tried to hold off fifty-five hundred of General George Stoneman’s Union cavalry, who were en route to Saltville. Needless to say, a Union victory resulted.

Follow the loop through the park. Steps climb the side of the hill to an observation area, for those who wish a better view of the rivers.

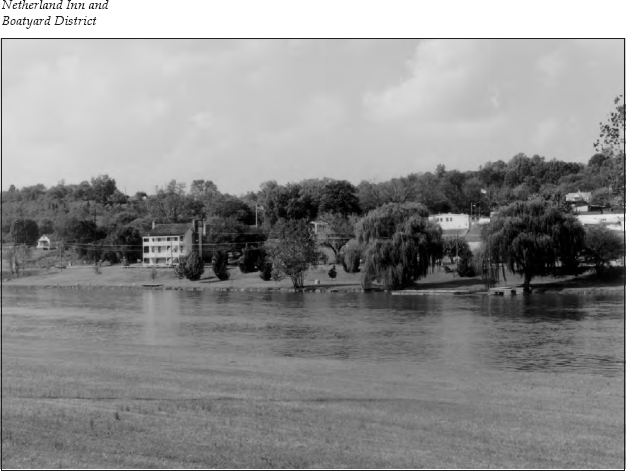

Continue along Netherland Road. This area has been developed into a park featuring jogging trails and picnic areas along the river. It is 0.9 mile to the Netherland Inn, on the left. Tours of the restored inn are offered for a fee. You can also visualize where the boatyard’s wharves used to be located along the riverfront. In the middle of the river is the Long Island of the Holston. In 1935, the island was one of the first sites in America to be designated a national historic landmark. It is now devoted primarily to baseball and soccer fields.

It is 1 mile from the inn to an intersection. Turn left and go under the overpass. Take an immediate left turn onto Fort Robinson Drive, which goes up the hill. This is the area where Fort Robinson and later Fort Patrick Henry were located. You will pass Fort Robinson Baptist Church.

It is four blocks to Marys Street. Turn right onto this street. On the left is Old Kingsport Graveyard, which was once part of Gilbert Christian’s plantation. Christian’s widow was buried here in 1812. The land was donated to the church in 1827.

Continue past the graveyard and turn right, where you will see Old Kingsport Presbyterian Church on the right.

This church, called Old Boatyard Presbyterian Church a few years ago, was organized in 1820. In October 1825, the Reverend Frederick A. Ross became the minister here. He preached at this church for several years without salary. Ross donated the land for the church when he drew up the lots for Rossville. The church was moved to its present location in 1953 but remains in its original condition. The bell tower still holds the great bell donated by Ross in 1850. In 1851, when he was on the verge of bankruptcy, Ross gave the structure to “the New Presbyterian Church.” He left the area in 1854 but continued his ministry in Chattanooga and later in Huntsville, Alabama.

To the left of the church is a fire department. Take a left and go one block to U.S. 11W. In front of the fire station is a river-rock monument designating the location of the Great Indian War Path.

This ends the tour. You can proceed into the city of Kingsport on U.S. 11W. The junction with I-26 is 0.5 mile to the right on U.S. 11W.