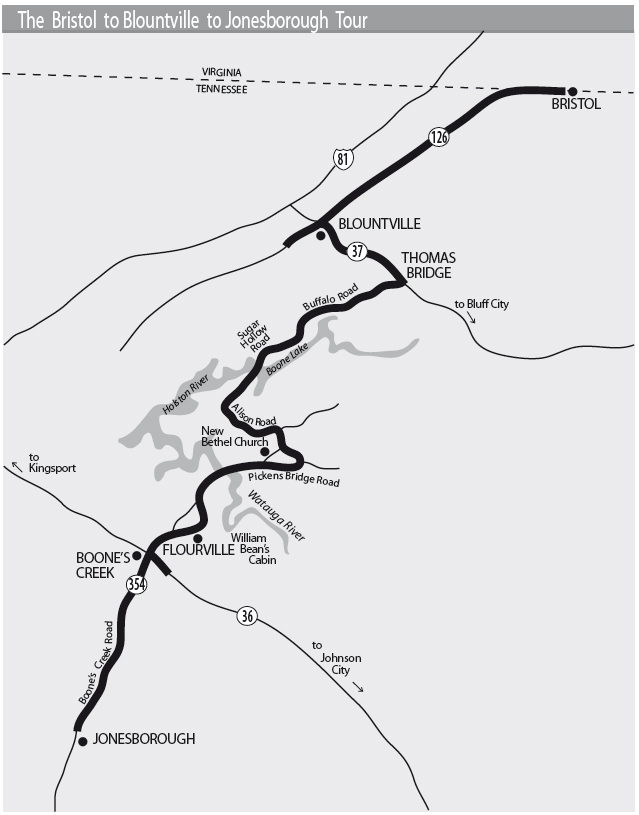

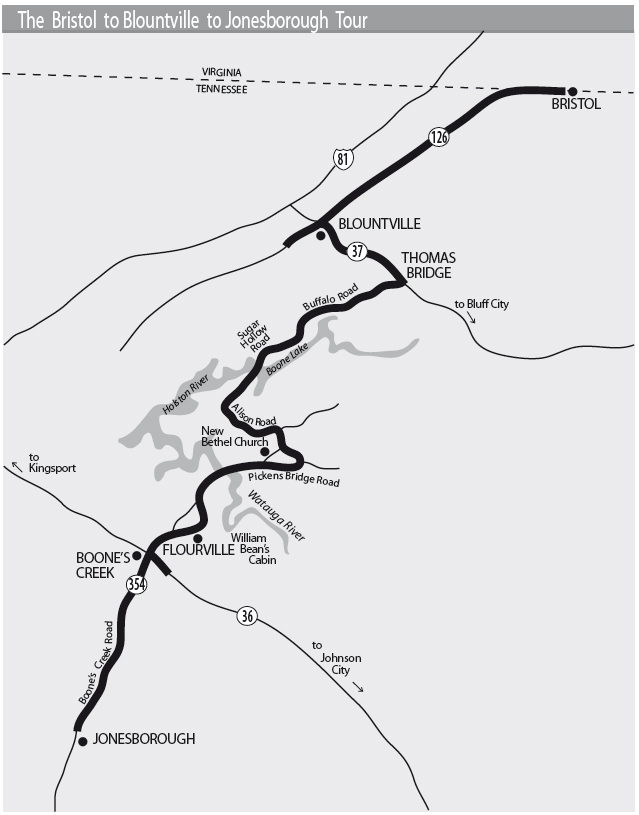

The Bristol to Blountville to Jonesborough Tour

This tour begins in Bristol on the Virginia-Tennessee line. It travels down the Great Stage Road to Blountville. From there, the route goes through the Fork Country to Boone’s Creek and on to Jonesborough.

Total mileage: approximately 40 miles.

This tour begins in downtown Bristol, literally on the state line. Bristol has the distinction of being half in Virginia and half in Tennessee.

This area was first known as Sapling Grove. The original tract of 1,947 acres was sold in 1749 to James Patton for fifty dollars. That same year, Evan Shelby and Isaac Baker came from Maryland and bought the tract. They paid £304 apiece and received 973 acres each. Shelby’s land became the site of Bristol, Tennessee, and Baker’s share part of Bristol, Virginia.

In 1771, the Shelby family built a fort on this land that covered over an acre and a half—about three blocks of the present city. During the 1780s, a hundred thousand immigrants passed through this fort on their way west. Inside the fort were Shelby’s home—known as Travelers Rest—a store, a still, Shelby’s weaving business, and room to shelter five hundred people. Local leaders gathered here to decide to join the forces at Sycamore Shoals that went on to fight at Kings Mountain. (For more information about Evan Shelby, see The Rogersville to Kingsport Tour, page 158.)

Colonel Isaac Shelby, Evan Shelby’s son, won fame during the Revolutionary War. After the war, he moved to Kentucky and became the first governor of that state. On November 26, 1814, he sold the Shelby part of Sapling Grove to Colonel James King. Isaac Shelby had the payment in gold and silver coin delivered to his home in Kentucky. The two horses that carried the payment were useless as beasts of burden after the journey because of the strain on their backs.

King, a civil engineer originally from London, had started an ironworks about 1784. He brought an expert foundry man from England to run it. This plant produced the first nails on the frontier. The quality of the ore, its high cost, and the difficulties of hauling it to the furnaces finally reduced the output of the twenty-nine furnaces.

On July 10, 1852, Joseph Anderson bought a hundred acres of land from his father-in-law, the Reverend James King, son of Colonel James King. Anderson had heard that the railroad was coming to King’s Meadows, as Sapling Grove was then known. The following year, a train depot was built. Anderson was convinced the town would become a leading industrial center, so he named it for Bristol, England. He subdivided his hundred acres into 216 lots, which he sold for a hundred dollars each. By 1856, the Tennessee legislature voted to incorporate the town, and Anderson became its first mayor.

In 1856, Anderson’s holdings in what is now Bristol, Virginia, and adjoining Goodsonville combined to become the community of Goodson. But people still called the town Bristol. Even the railroad refused to change Bristol, Virginia, to Goodson. So, in 1890, Bristol, Virginia, became the official name.

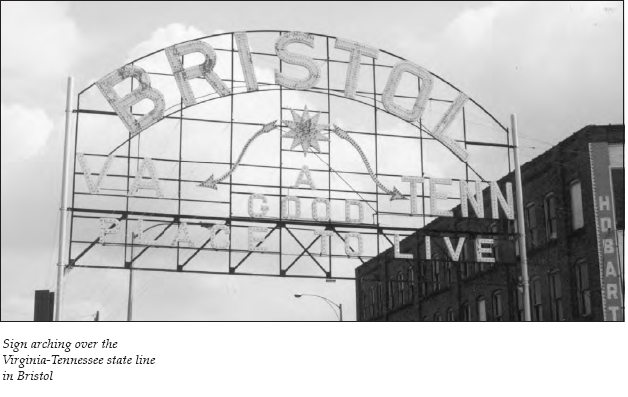

In 1910, the huge neon sign that now arches over State Street—Bristol’s main street—was erected on top of a hardware building near the railroad tracks at the corner of Third Street. The owners of the store complained that the sign was damaging their building, so Bristol Gas and Electric Company formally donated it to the city on July 5, 1910. The sign’s first slogan was “Push—That’s Bristol.” But the lights burned out in various combinations, spelling, at times, “Pu__—That’s Bristol” and “__sh—That’s Bristol.” Local leaders were not amused, so a contest was held to choose a new slogan. In 1921, the sign was changed to read “Bristol VA-TN—A Good Place to Live.”

After viewing the sign, travel down State Street (which is also U.S. 421), heading toward Kingsport. State Street is actually the boundary between the two states. You will see the brass plates that follow the centerline and define the exact boundary between the two Bristols.

At the corner of State and Eighth streets is a large mural on the side of the building on your left. This mural depicts the famous recording sessions that give credence to Bristol’s claim of being the birthplace of country music.

In July 1927, Ralph Peer, a scout for Victor Recording Company, announced in the Bristol Herald Courier that he was searching for talent to record at a temporary studio set up at 408 State Street. Musicians and singers from all over the Appalachians flocked to Bristol to take advantage of this opportunity.

On August 1, Peer recorded the Carter Family, from Maces Springs in nearby Scott County. This recording of A. P., Sara, and Maybelle Carter included “Bury Me Under the Weeping Willow” and “The Poor Orphan Child.” The following day, Sara and Maybelle returned to record “Single Girl, Married Girl” and “The Wandering Boy.”

That same summer, a former railroad worker from Mississippi named Jimmie Rodgers was performing with a band in Asheville, North Carolina. When the band members heard of Ralph Peer’s search, they came to Bristol. But on the eve of their first session, they voted to drop Rodgers and go it alone as the Tenneva Ramblers. Having nothing to lose, Rodgers decided to record as a solo act.

On August 4, between 2:00 and 4:20 p.m., Rodgers recorded four takes of “The Soldier’s Sweetheart” and three takes of “Sleep, Baby, Sleep.” His distinctive “blue yodel,” a mixture of the blues from his days on the railroad and the yodeling of the mountain region, made Rodgers country’s first real star and a household name between 1927 and 1933.

To say that the Bristol recording sessions were a success would be an understatement. These sessions produced the first country-and-western records distributed nationwide.

After viewing the mural, continue along State Street. The Bristol Chamber of Commerce is located on the left at the corner of State and Volunteer Parkway. It is 1.6 miles from this intersection to the intersection where TN 126 goes off to the left, heading west. Turn onto TN 126. You are following the route of the Great Stage Road.

In 1795, one main stage route went from Abingdon, Virginia, to Blountville. Blountville served as a kind of crossroads, since there were three different routes stagecoaches could travel when leaving town. Horses were changed about every 10 miles at relay stations. The first change after leaving Abingdon was at King’s Meadows and the second at Blountville. Drivers’ runs were about 25 miles, so the driver from Abingdon laid off at Blountville, and another driver then took the stage from Blountville to Jonesborough. The run from Abingdon to Blountville took three and a half hours, barring serious trouble along the way.

After your turn onto TN 126, it is 1 mile to the turnoff for Steele Creek Park, a recreation area operated by the Parks and Recreation Department of Bristol, Tennessee. It is a short distance down to this park, which offers good picnic areas and recreational facilities, including a golf course.

Return to TN 126, turn left, and continue 1.7 miles past the Steele Creek Park turnoff. You will see a sign for Akard Elementary School on the left; this is a good landmark to alert you to the upcoming turn. It is 0.2 mile past the sign to the turnoff for Old Stage Trail, a dead-end road that veers off to the left for 0.2 mile. At the end of Old Stage Trail, you will see two houses known as the Steele-Barker-Senecker Houses. These homes are listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

The Steele (or Steel) House, on the left, was built around 1777 and is one of the oldest houses in Sullivan County. Actually a two-story log structure, it is sheathed in aluminum siding today. Nearby Steele’s Creek was named for the family that owned the home.

The Steele-Barker-Senecker House, across the road, was also built around 1777. It once served as a stagecoach stop. This home, made of hand-fired brick, is reputed to be the second-oldest brick house in Sullivan County. During the old days, when the stagecoach delivered the mail, this house served as the local post office, called “Stop Tennessee.” An old post office still stands on the property. The Steeles were early settlers who were instrumental in surveying the Great Stage Road, a section of which remains on the south side of this house.

Return to TN 126 and turn left. On your right immediately after the turn is the James King Senecker House, built shortly after the Civil War. During the war, Union soldiers camped near the spring on the property. The compensation the family received for the soldiers’ occupancy went into building the house, which was first occupied in 1870.

It is approximately 3 miles to the intersection with TN 37 on the outskirts of Blountville. Continue straight on TN 126 into the town’s historic district.

After the establishment of Sullivan County in 1779, the courts met in various private homes until land for a county seat was donated in 1792, the year Blountville was born. That same year, James Brigham gave thirty acres of his plantation to build a permanent county seat. The town was named in honor of William Blount, the first governor of the Territory of the United States South of the River Ohio. By 1795, Blountville had become a major stopping place on the Great Stage Road.

The Battle of Blountville was fought on September 22, 1863. This area of East Tennessee was of strategic value during the Civil War, since the railroad served as a vital link between the upper Confederacy of Virginia and the states of the lower South. The area remained under Confederate control until Ambrose Burnside took command of Union forces in East Tennessee. Burnside mapped out an aggressive campaign all along the railroad line. He sent General James Shackleford and his twenty thousand troops into upper East Tennessee. In response, Confederate general Sam Jones led his five to six thousand men out of Zollicoffer (now Bluff City). Shackleford then sent Colonel John Foster on a flanking move, and Jones sent Colonel James Carter to meet Foster. The Confederates drove Foster back. But the Union forces received reinforcements and drove the Confederates back to Blountville on September 22.

Colonel Carter stationed his 1,257 men on the plateau east of town. Foster, whose forces numbered twice the Confederate strength, took his stand near the graveyard on the opposite side of town. The townspeople—mostly women and children—were not aware that a battle was impending until the firing started about noon. The battle lasted four hours.

A shell hit the courthouse, setting it on fire, and the flames spread quickly to surrounding buildings. In the confusion, women and children ran through the streets, more dangerously exposed than the soldiers on either side. Most residents fled to the meadows and hills outside town. By the end of the afternoon, Jones reinforced Carter, and the Union soldiers retreated from Blountville. The Confederates lost only three men, while the Federals counted twelve dead.

The residents of Blountville returned to their homes to find that what had not been destroyed had been looted. The women were forced to beg food from the soldiers.

In October, Burnside’s forces came through the area again, and George Stoneman’s troops followed in December 1864. Although looting occurred each time, Blountville did not again suffer the extensive destruction of the first battle.

The buildings that remained after the battle make up the bulk of the Blountville Historic District, which is on the National Register of Historic Places. The district has a quaint charm. A map of the historic district is included here; this tour will offer interesting anecdotes about some of the buildings in the district.

As you come into the historic district, you will see Anderson Hall on the right. This two-story brick home was made of hand-fired bricks. In 1799, Dr. Elkanah Dulaney came to Sullivan County from Virginia. He purchased this lot in 1800 and built the oldest brick edifice still standing in Blountville. One of Blountville’s first physicians, he used this home as his townhouse. His country plantation, called Medical Grove, was a short distance west of town. Dr. Dulaney supposedly took his slaves to Mount Vernon to learn the art of brickmaking from the slaves of George Washington.

Across the street on the corner is the Miller-Haynes House, also called “the Cannonball House.” This two-story white frame home was built in 1848 by another physician, Dr. Elbert Miller. In 1855, the house was sold to Matthew Taylor Haynes, a Blountville attorney. Haynes was the brother and law partner of Landon C. Haynes. (For more about Landon Haynes, see The First Frontier Tour, page 22.)

During the Civil War, Matthew Haynes held the Confederate office of state receiver, responsible for confiscating the property of Union sympathizers. As you can imagine, this made him a rather unpopular guy with some factions. When the Battle of Blountville began, Federal troops fixed their cannons on his home. Several balls hit the west side and lodged in the chimney on the opposite side, giving the house its nickname. Matthew was ill with a fatal case of typhoid fever at the time. When the attack began, he was carried across the street to the Deery Inn for safety. A side door in the Miller-Haynes House remains riddled with bullets even today.

Farther down the street, you will see Blountville Methodist Church on the left. In 1806, the Methodists became the first denomination to erect a church in Blountville. The current building, constructed in 1939, is the third Blountville Methodist Church.

An interesting story about its predecessor survives. During the Battle of Blountville, the Confederate forces included a battery led by Captain Davidson. This battery had distinguished itself for its marksmanship earlier in the war. Captain Davidson was told that Federal sharpshooters were in the belfry of the Methodist church, but he was instructed not to hit the bell. He sent one ball just above and one just below the bell—even though the church was a quarter-mile away. Since the church stood almost next door to Matthew Haynes’s home, a lot of ammunition must have been flying through the air in that general area.

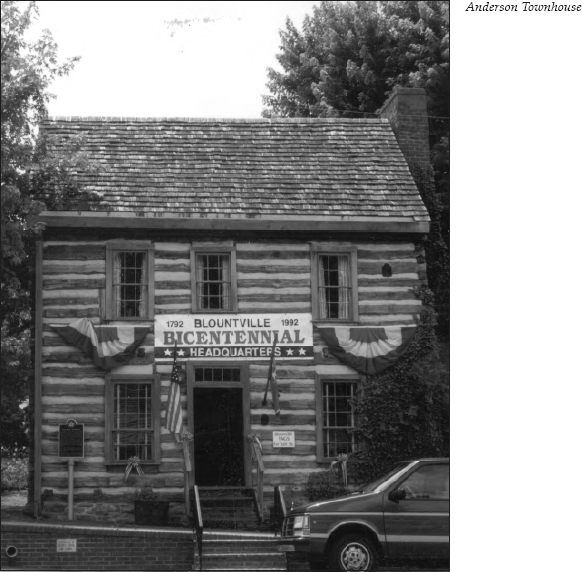

Next to the church is the Anderson Townhouse. This two-story structure of hand-hewn logs was built between 1792 and 1795. The first Blountville town commissioners used it as a home while they were in town. Colonel John Anderson, whose home straddled the Virginia-Tennessee line north of Kingsport, lived the greatest distance from Blountville; when he was appointed a justice of the first Sullivan County Court in 1780, he became the most frequent resident of the townhouse. Joseph Anderson, who went on to found the city of Bristol, resided in the townhouse from 1835 to 1853 while he clerked at his uncle’s store in Blountville.

Next to the Anderson Townhouse is Blountville Presbyterian Church. The present church’s cornerstone was set in 1935, but the congregation was organized way back in 1820. The first church actually stood on Graveyard Hill.

This church hosted a famous visitor on July 27, 1836. The Reverend Daniel Rogan was beginning his sermon when a group of eighteen people approached, some in carriages, others on horseback. Seeing the party outside, the preacher stopped and said that Andrew Jackson, then president of the United States, was arriving. He announced a hymn and led the singing. The party entered, and when the song was finished, the minister preached his sermon, “Remember the Sabbath Day and Keep It Holy.” After the sermon, the visitors were introduced to the congregation.

Across the street from the Anderson Townhouse is the Deery Inn, listed on the National Register of Historic Places. This inn has served many distinguished travelers, including Andrew Jackson; the Marquis de Lafayette; Louis-Philippe, the duke of Orleans; James K. Polk; and Andrew Johnson.

Built sometime around 1785, it has eighteen rooms, two attics, three cellars, and ten outbuildings. The building actually is comprised of three sections: a two-story hewn-log house, a two-story frame store building, and a three-story stone house. It has four chimneys and seven fireplaces. The building was used off and on as an inn until 1939.

William Deery was born in Northern Ireland and immigrated to Baltimore. From his base in Maryland, he traveled all over the country as a pack peddler. After moving to Blountville, he accumulated enough wealth by 1821 to purchase fifty-three teams of horses and eight stagecoaches. He also owned stores all over East Tennessee and even owned a steamboat that ran from Knoxville to Chattanooga. After he died in 1845, his estate was in litigation for thirty-seven years.

Next to the Deery Inn is the Sullivan County Courthouse. The west end of the structure was erected in 1853, then rebuilt in 1866 after it burned during the Battle of Blountville. The thick, hand-fired brick walls sustained little damage, although the roof and interior were destroyed. A Confederate monument commemorating the Battle of Blountville stands in front of the courthouse.

A good story is told about the discovery of treasure in the courthouse. Supposedly, in September 1882, John Hicks, a day laborer, was hired to clean out the cellar so wood could be stored there for the winter. Rubbish had not been cleaned out of the cellar since the courthouse was rebuilt. After digging for a while, Hicks struck a cast-iron box. Inside were gold and silver. Hicks made the mistake of running outside and telling everyone he saw about the treasure. Half the town showed up at the courthouse, and in the wild scramble, all the money disappeared. The box contained an estimated two thousand dollars, but no one ever determined the source of the money. Because several coins fell in the rubbish during the mad scramble, people came to search the area for some time after the incident.

Behind the courthouse is the old jail, built in 1870.

Proceed down Main Street to the intersection with TN 394. Cross this highway and go straight up the hill. It is 0.1 mile to the Blountville Cemetery, on the right. The cemetery is on Graveyard Hill, the location of Federal batteries during the Battle of Blountville. The cemetery was in use as early as 1800, and many of the area’s most illustrious citizens are buried here.

Once you have viewed the cemetery, retrace your route to the intersection with TN 394 and turn right. After approximately 3 miles on TN 394, you will see a little red schoolhouse nestled on the hillside on the left. Built in 1905, it served area children for many years.

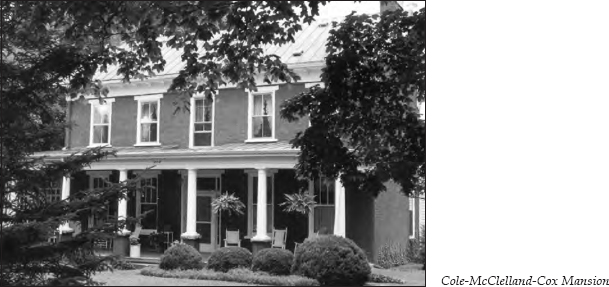

Just past the Bristol Motor Speedway, on the left, you will cross Beaver Creek. Just beyond the bridge is the Cole-McClelland-Cox Mansion, on the left.

This impressive hand-fired brick home is an excellent example of Federal-style architecture. Its several outbuildings are all in excellent condition. The home evolved from an early frontier log house into a beautiful brick mansion. The log section is believed to have been built around 1785. During the early nineteenth century, it was enlarged to a frame structure when several rooms were incorporated into the log house. Before 1860, the entire house was placed within its present hand-fired brick exterior. In 1906, Thomas Edison, Harvey Firestone, and Henry Ford traveled in this area. They made a stop at the house to see a well-run Tennessee farm.

Across from the Cole-McClelland-Cox Mansion, turn right onto Beaver Creek Road. Travel 2.3 miles on Beaver Creek Road to a sign on the right announcing the Buffalo Ruritan Club. Turn right here onto Buffalo Road and travel over a short bridge. It is 2.6 miles on Buffalo Road to a T intersection with Sugar Hollow Road. Turn left and travel 2 miles on Sugar Hollow Road, which ends at DeVault Bridge Road. Turn left. It is 0.8 mile to the bridge. During this whole segment of the tour, you have been traveling alongside Boone Lake, a TVA-created lake on the South Fork of the Holston River.

It is 1.4 miles on DeVault Bridge Road to where the road makes a sharp curve to the left. A general store sits on the left in the curve. Just past the curve, the road’s name changes to Alison Road.

John Alison, Sr., and his family moved to this area from Maryland in 1779. Alison owned a large tract of virgin hardwoods that is still referred to as “the Alison Forest.” Although modern homes are quickly popping up in this pastoral area located about midway among Johnson City, Bristol, and Kingsport, you can still see evidence of the hardwood forest.

Alison settled in what was known as the Fork Country, so named because it was located at the confluence of the Holston and Watauga rivers. His original log homestead burned in 1840. Jesse Alison was the son of John Alison, Jr. After his father’s death in 1832, Jesse purchased the interests of the seven living heirs to the 428-acre home tract of John Alison, Sr. This tour will pass the homes of several Alison heirs.

It is 3.3 miles from the store at Alison Road to the turnoff for New Bethel Road; this is not a four-way intersection, so keep your eyes peeled for the road. Turn right onto New Bethel Road. It is 0.7 mile to Carter Hill Road. Turn left onto Carter Hill Road. It is 0.4 mile to a two-story brick house on the left. This home, known as the Oliver Mansion, was built sometime around 1855. It has two brick chimneys, four fireplaces with walnut mantels, and all its original hardware. The doors and windows are pegged. The surrounding outbuildings are still well maintained.

It is 0.5 mile to the T intersection with Pickens Bridge Road. Turn right. After 0.7 mile, you will see New Bethel Road on your right. Turn right onto New Bethel Road for a detour of 0.3 mile to New Bethel Church and its cemetery, located atop the hill. This church, one of the oldest in Tennessee, was organized in 1782 by Samuel Doak and named in honor of Bethel Church in Virginia, where Doak spent his early years. (For more information about Samuel Doak, see The Jonesborough to Greeneville to Bulls Gap Tour, pages 110–11.)

The first church on this site was made of logs. The pulpit was in the west end, where the male portion of the congregation gathered. The women and children occupied the end near the chimney. When an addition was built in 1838, the pulpit was then in the middle of the north side of the church. The present church replaced that building in 1879. The adjoining cemetery is the resting place of many soldiers who served in the Revolutionary War and later wars.

After viewing the church and cemetery, return to Pickens Bridge Road and turn right. It is 0.2 mile to the Finley Alison House, on the right.

Finley Alison was the youngest son of John Alison, Sr. Finley built this hand-fired brick home around 1811 on land he inherited from his father. The home, listed on the National Register of Historic Places, has been carefully restored. It has brick walls eighteen inches thick and a twenty-inch-thick limestone foundation.

One sad footnote about the house tells of a day in 1833. After most of the Alison family had attended services at New Bethel Church, they returned home and found Finley lying dead at the foot of the long, steep stairs leading to the front veranda. Apparently, he slipped on the stairs and died from a broken neck.

It is 0.3 mile down the road to the Robert Alison House, on the right. Robert was the oldest son of John Alison, Sr. He was thirty years old and a Revolutionary War veteran when he came with his father to the Fork Country. He married Martha McKinley, whose family eventually produced President William McKinley. In 1784, Robert received a hundred-acre grant on the north side of the Watauga River, where he built this home. Actually constructed of hewn logs, the house is covered by siding today.

It is 0.5 mile to the Pickens Bridge across the Watauga River. After the bridge, it is 1.9 miles to a turnoff on the left for Flourville Road at Oak Hill Farm, which you will see as you approach across the valley. Turn onto Flourville Road.

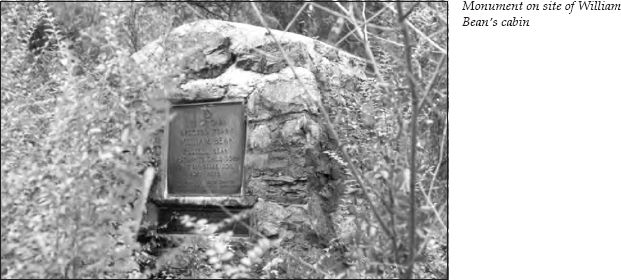

After traveling 0.9 mile, you will see an old mill ahead. Just before the mill is a bridge crossing Boone’s Creek. To your left is Cabindale Road. Turn left onto Cabindale Road, following the creek as it empties into Boone Lake. It is 0.3 mile to Sonny’s Marine Store. If the store is open, ask the people there if it is a good time to walk to the site of William Bean’s cabin.

William Bean, who settled here in 1769, is considered the first permanent settler west of the Appalachians. His son, Russell, born in 1769, was the first white child born in Tennessee. (More information about Russell Bean is presented later in this tour.)

The site where William Bean located his cabin had previously been used as a hunting camp by Daniel Boone, a good friend of Bean’s. Boone made frequent trips to the area both to hunt on his own and to explore on behalf of Richard Henderson. Boone was a surveyor and hunter, as well as a good real-estate agent. His confidence and his glowing tales of the undeveloped wilderness convinced many settlers to purchase land from Henderson and travel west. Although Boone’s long and solitary times in the wilderness seem amazing by today’s standards, he was only doing what all long hunters did. What made Boone different was his role in leading other settlers to the region.

Today, this historic site is in bureaucratic limbo. When the TVA built Boone Dam on the Watauga River, it acquired much of the land bordering the new waterfront. The historic site was left stranded. The TVA donated it to the state, but no one currently maintains it. Even in a time of budget crunches, it seems that some local civic organization should adopt the preservation of this site. Some of the neighbors try to keep the weeds down in the summertime, but access to the area is difficult.

The best time to view the historic marker, erected by the Daughters of the American Revolution years ago, is to wait until the water in the lake is down in the late fall or winter. Then you can walk along the edge of the water to the point. The lack of foliage during the cold season also makes the marker easier to see. Since no one works at Sonny’s Marine Store during the winter months, the best advice is to walk along the edge of the woods from the lawn of the brick house nearest the store. Well-worn paths lead from the docks—which lie in the dirt when the water is down—to where the marker is located.

Return to Flourville Road and turn left, heading toward the old mill. This mill was where Daniel Boone Flour and Becky Boone Corn Meal were made. You can see the waterwheel on the left side of the mill as you drive up.

Continue on Flourville Road for 0.5 mile to a stop sign at the intersection with Pickens Bridge Road. Turn right for a short side trip to Boone’s Creek Baptist Church, located at the top of the hill. This church was founded in 1881. The adjoining cemetery has several graves of Revolutionary War veterans.

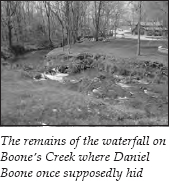

Retrace your route on Pickens Bridge Road and continue 0.4 mile to the intersection with TN 36. Turn left onto TN 36, or North Roan Street. It is 0.5 mile to Boone’s Creek School, on the left. Across from the school is Old Gray Station Road. Turn right and go 0.2 mile to a bridge across Boone’s Creek. Park in the lot just before the bridge if you want to take a look at Daniel Boone’s famous waterfall, which is now the focal point of Landlord’s Landscaping.

Legend says that Daniel Boone once hid from hostile Indians underneath these falls. He was supposedly on one of his frequent hunting trips to the area when he noticed that Indians were on his trail. Not wishing to lead them back to his camp, he hid underneath the falls. When it seemed to the Indians that he had vanished into thin air, they supposedly fled in terror, believing he had made himself into an invisible spirit.

It is difficult to imagine anyone hiding underneath the small cascade you see today. Sources say the waterfall used to be four feet high but has eroded over the years.

After 0.3 mile, Old Gray Station Road intersects Boone’s Creek Road. Continue on Old Gray Station Road for 1 mile. You will cross Reedy Creek. On the left is a dirt road located on private property. A famous beech tree bearing a knife-carved inscription was located along this creek. The inscription read, “D. Boon cilled a Bar on Tree in the yEAR 1760.” Some of the wood from the tree was carved into gavels, which were given to important political figures. Today, a marker is located where the tree once stood. Because the marker is on private property, searching for it is not advised.

Return to Boone’s Creek Road and turn right, heading toward Jonesborough. It is 7.1 miles to the intersection with U.S. 11E on the outskirts of town. Go straight across the intersection. You will see the Historic Jonesborough Visitors Center on the right. There, you can view a brief film about the area and tour the museum for a small admission fee. You can also buy a map for a walking tour of the historic district. The map accompanying this tour highlights portions of the historic district; some of the buildings with interesting historical figures or anecdotes are detailed in the following pages.

Although many places in East Tennessee argue over being the second- or third-oldest town in the state, no one seems to dispute that Jonesborough is the oldest. Authorized in 1779, the town was laid out in 1780. The fact that the early settlers had the foresight to insist on high standards is shown in the building restrictions included in the enabling act. Each owner was required “to within three years build a brick, stone, or well framed house, 20 feet long and 16 feet wide, and at least 10 feet in the pitche [sic], with a brick or stone chimney. . . . If the owner failed to build and finish theron as before described, then such a lot shall be forfeited.” The result is a quaint village that attracts tourists to its historic area. Jonesborough also holds claim to being Tennessee’s first national register historic district.

After leaving the visitor center, continue into town on Boone Street, which flows into Main Street. Follow the curve to the right, heading west on Main.

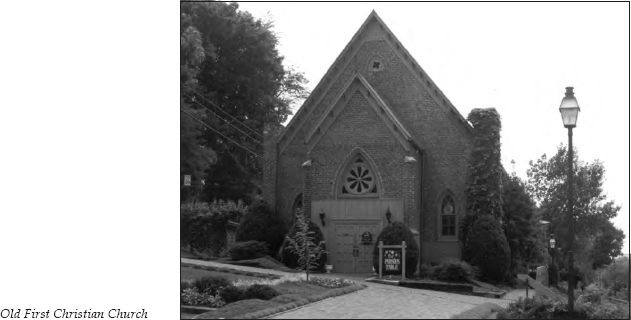

As you come down Main Street, you will see the clock tower atop the Washington County Courthouse. Just before the courthouse is Central Christian Church. During the Civil War, Jonesborough Presbyterian Church was split between Union and Confederate sympathizers. The Union sympathizers broke away and constructed this building for their house of worship. After the war, the Presbyterians reunited, and the members sold this building to First Christian Church. The congregation of First Christian Church was in need of a larger facility, having outgrown its own building, which will be visited later in this tour.

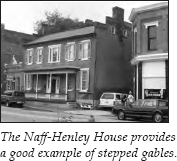

Across the street is the Naff-Henley House. One of the oldest private residences in the downtown business district, it provides an excellent example of stepped gables. Jonesborough is said to have more structures with stepped gables than any other Tennessee town of similar size. Instead of having the gable wall and the roof end in a straight line from eve to ridge comb, the wall rises above the roof, ascending in a series of large steps on either side and generally ending in a chimney in the center. Most of the buildings exhibiting this characteristic were built between 1830 and 1860.

Across the street is the Washington County Courthouse. In front of the courthouse stand two monuments, one indicating the route of Daniel Boone’s explorations, the other acknowledging this street as the route of the Great Stage Road.

The day after the signing of the Declaration of Independence, the leaders of the Watauga Association sent a request to the Provincial Council of North Carolina asking permission to form their own district, which would include a court and a militia. (The timing was coincidental, since it was weeks before local people learned of the signing of the Declaration.) A year later, the North Carolina General Assembly formed Washington County, with boundaries a little greater than the present state of Tennessee. The court met in private homes while the residents along the Watauga and Nolichucky rivers argued over the court’s permanent location. The choice, Jonesborough, was a compromise, halfway between the two existing settlements and near a number of free-running springs, which would assure a sufficient water supply.

The first courthouse was built in 1779, and five subsequent courthouses were all located on approximately the same site. The present building was erected in 1913. The Washington County Courthouse served as a meeting place for the men who formed the State of Franklin until the new state’s capital was moved to Greeneville in 1785. (For more about the State of Franklin, see The Beauty Spot to Nolichucky Tour, pages 68–70.)

A whipping post and pillory stood in front of the courthouse. The people of the frontier were used to violence and did not hesitate to deliver sharp justice. Women as well as men felt the whip. Records show that one woman found guilty of petty larceny was sentenced to “receive ten lashes at the public whipping post by the hours of four o’clock this afternoon.” A particularly brutal punishment was handed out to a man convicted of perjury. He was sentenced to “stand in the Pillory one hour, having his Ears nailed during the whole time, and at the expiration of said hour, both Ears of him . . . shall be cut off and Severed from his head, leaving them nailed to the Pillory until the Setting of the Sun.”

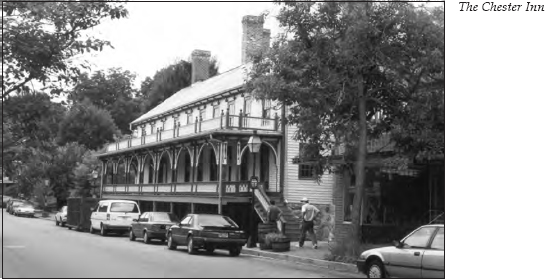

The Chester Inn is located on the right farther along Main Street. Considered the oldest frame structure in town, it was built by Dr. William P. Chester, who came to this area from Pennsylvania in the 1790s. Built in 1797, the inn and tavern became immediately popular with the traveling public. Among the visitors were Andrew Jackson, James K. Polk, Andrew Johnson, and John C. Calhoun. The inn has been restored and is now part of the International Storytelling Center’s complex. Each October, the International Storytelling Center sponsors a national storytelling festival that draws large audiences for storytellers from all over the country.

Next to the Chester Inn is the Christopher Taylor House. Built by Jacob Womack in 1778, this is one of the oldest log houses in Tennessee. For years, it sat on the outskirts of Jonesborough. Since it was moved to its downtown location, it has served as a keystone of the town’s restoration effort.

Andrew Jackson’s early legal career was closely intertwined with the history of early Jonesborough. In fact, Jackson boarded with Christopher Taylor while living in town. Jackson and four other lawyers were admitted to the bar in the log courthouse in Jonesborough in 1788. His fellow inductees also went on to illustrious legal careers. This group claimed three judgeships and the governorships of two states; members of the group became a representative in Congress and a United States senator. And of course, Jackson became the seventh president of the United States.

When the new court district was formed, twenty-one-year-old Andrew Jackson left North Carolina for opportunities in the West. John Allison records in his 1897 book, Dropped Stitches in Tennessee History, that when Jackson arrived in Jonesborough in 1788, he was “riding a race horse, with a pair of holstered pistols strapped to the saddle leading a pack horse carrying his personal possessions, whilst trotting along behind was a pack of fox hounds.” Jackson soon put his racehorse to work in the famous Greasy Cove race (see The Beauty Spot to Nolichucky Tour, pages 61–62).

All accounts indicate that Jackson was a man of action whose hot temper frequently got him in trouble. Soon after he began practicing law, he was opposed by Waightstill Avery, an experienced lawyer. Jackson was continually forced to rely on his favorite authority, Bacon’s Abridgement of Law. In the course of the trial, Avery began to ridicule Jackson’s frequent references to Bacon. Insulted, Jackson followed up with a letter to Avery on August 12, 1788, that read, “When a man’s feelings and character are injured he ought to seek a speedy redress. . . . I therefore call upon you as a gentleman to give me satisfaction for the same and further call upon you to give me an answer immediately without equivocation and I hope you can do without dinner until the business done, for it is consistent with the character of a gentleman when he injures a man to make a speedy reparation.” Jackson added a postscript: “This evening after court adjourns.”

The two men and their friends met at sunset on a hill south of town. By that time, tempers had cooled, so both men fired into the air. Avery had brought a small package to the field. He handed it to Jackson, saying, “Had I mortally wounded you, I know of nothing that would have so cheered your last moments as your beloved Bacon.” Thinking it a copy of his favorite book, Jackson opened the package to find a piece of well-cured bacon instead. He was not amused, but mutual friends intervened to restore calm.

Jackson soon moved on to a judgeship. While he held that position at the court in Jonesborough, an incident occurred that added to his growing legendary status. This incident involved the arrest of Russell Bean, who was William Bean’s son and the first white child born in Tennessee. Russell Bean, who resided in Jonesborough, was noted as one of the best gunsmiths in the area. Although he had served as deputy sheriff in territorial days, his temper often brought him on the wrong side of the law.

Bean had been off selling his wares in New Orleans for two years. The incident began when he returned to Jonesborough and found his wife with a new baby. This presented a small problem. Being a typical frontiersman, Bean simply drew his knife and cut off both the baby’s ears. The warrant for his arrest noted that Bean justified his actions by saying he wanted “to mark it so I can tell it from my own.” After receiving punishment for this act, Bean gave the brother of his wife’s lover a severe beating. When a trial for this new offense was called, the sheriff reported to Judge Jackson that Bean was sitting in his doorway, rifle across his knees, defying arrest.

Enraged at this defiance of his court, Jackson ordered the sheriff to bring the culprit in “if you have to summon every man in town to do it.” The sheriff retorted, “All right, I’ll summon you first.” Unafraid, Jackson marched up the street and confronted Bean. Bean put his rifle aside and announced, “I’ll surrender to you, Mr. Jackson, but no other living man could take me.” Jackson marched his prisoner back to court, held the trial, and levied a stiff fine.

On March 22, 1803, Jackson added another incident to his legend. Concerning his role in extinguishing a fire in the local stables, he wrote his wife, “During the distressing scene I was a great deal exposed, having nothing on but a shirt. I have caught a very bad cold—I saved my horse from the flames not until I made the third attempt before I could force him into the passage.” Others reported that Jackson was the hero of the hour. One of the first on the scene, he organized a bucket brigade and moved property out of the flames. His principal assistant was Russell Bean.

In 1832, Jackson returned as president of the United States. He was met about 4 miles east of Jonesborough and escorted into town by a group of a hundred horsemen. The next day, a reception was held on the porch of the Chester Inn, where he had stayed on occasion.

Next door to the Christopher Taylor House stands Jonesborough Presbyterian Church. In 1790, Samuel Doak and Hezekiah Balch organized this church’s predecessor, Hebron Presbyterian Church, which had about fifteen original members. Soon, a log meeting house was built. A larger church was erected in 1831.

Dissension later broke out over doctrinal issues. But Hebron Church remained united, siding with the Reverend Balch and “the New School.” (For more information about the division between Doak and Balch, see The Jonesborough to Greeneville to Bulls Gap Tour, pages 119–20.)

In April 1840, the Hebron name was dropped, and the church became Jonesborough Presbyterian Church. Unfortunately, as mentioned earlier in this tour, the congregation couldn’t stay united when the Civil War broke out.

In 1847, a lot was purchased next to the Chester Inn for the erection of the present church. The original design called for wide front steps outside the building, but the women in the congregation demanded an alteration. Although hoop skirts were the fashion rage, social standards required that ladies’ ankles never be displayed. The open stairs had to go. They were replaced by an inside staircase.

Next to the church is the Humpston House. The historical marker in front of the house indicates that this was the location of Jacob Howard’s print shop. Howard came to Jonesborough in 1818. His shop printed The Manumission Intelligencer and The Emancipator, Elihu Embree’s abolitionist newspapers (see The Beauty Spot to Nolichucky Tour, pages 65–66). In fact, the first sheets to come from Howard’s press were The Manumission Intelligencer. When the short-lived Intelligencer folded, Howard offered his own paper, the Tennessee Patriot, which lasted only a year or two. In November 1825, he issued The Farmers Journal, which he announced would avoid politics and disseminate useful knowledge. This paper lasted for several years.

Farther down Main Street on the right is the Mansion House, also called the May House. J. W. Simpson, a prosperous farmer who lived south of Jonesborough, built this brick Georgian house in 1851. It was a well-known stagecoach stop in its early days, but its career as a hotel was cut short by the building of the railroad and the beginning of the Civil War. When the railroad came to town, the depot was constructed south of where the courthouse stands today. John Blair, a lawyer and former member of Congress, seized the opportunity to build a third story on his residence near the depot. He then opened a hotel, known as the Washington House. Most travelers chose this new hotel for their meals and lodging. But the Mansion House still stands in all its splendor, while the Washington House no longer exists. The porch, with its Victorian woodwork, was added later.

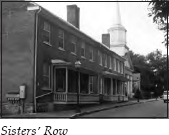

Across the street is Sisters’ Row. In 1820, Samuel D. Jackson built this long, two-story brick house, which featured three separate apartments for his three daughters. Each unit was deeded to one of the sisters, hence the house’s name.

After you have seen Sisters’ Row, retrace your route up Main Street and turn right onto the side street just before the courthouse. On the right, you will see the Mail Pouch building. Its wall boasts a nearly perfect turn-of-the-twentieth-century Mail Pouch Tobacco mural. Constructed in 1889, this is the only remaining saloon building in Jonesborough. The saloon closed in 1904, when the town voted to prohibit the sale of alcohol.

At the end of the street are steps leading up to a building that was the original church used by the First Christian Church congregation—the congregation that later took advantage of the unification of Jonesborough’s Presbyterians to move to its present location. Construction on the original church began in 1870, but a cholera epidemic brought work to a halt. W. H. Fleming, working on the interior woodwork at the time, used the unfinished building as a shop for making coffins for plague victims. When one of the congregation’s largest contributors to the building fund died of the disease, construction was further delayed. The building was finally completed in 1874.

Turn left and travel behind the courthouse. Turn right onto Fox Street, located just past Central Christian Church’s present building. On the left at the top of the hill, just past the railroad tracks, is the Salt House.

Salt, essential for curing meat, was in short supply during the Civil War, even though saltworks in Virginia were not too far away. In January 1864, the county purchased forty-five hundred dollars’ worth of salt and appointed someone to distribute it. The price was fifteen dollars per sack in current bank notes or thirty dollars in Confederate money—the handwriting must have been on the wall as early as 1864. The salt was stored in this building. Even though the building has gone through other incarnations—it has served as a post office, a Masonic hall, and a wholesale grocery—it still retains the name it picked up during the Civil War.

Turn right onto Woodrow Avenue. The several bed-and-breakfast inns on this street are all housed in early Jonesborough structures. The second house on the left is known as the Old Jacobs House.

In 1800, Thomas Emmerson arrived in Knoxville to practice law. Before he retired in 1821, he served as the first mayor of Knoxville, a judge of the superior court, a charter trustee for East Tennessee College (now the University of Tennessee), and a justice on the Tennessee Supreme Court. After retiring, Emmerson moved to Jonesborough to devote time to agricultural experiments on his Cherokee Creek farm. When he first came to town, he lived in the Old Jacobs House.

In 1834, Emmerson published a sixteen-page monthly called The Tennessee Farmer, which included articles about cultivating grain and caring for poultry and fruit trees and even advocated the daring idea of teaching scientific agriculture. He also purchased The Farmers Journal and renamed it The Washington Republican and Farmers’ Journal, commonly referred to as The Republican. Emmerson continued as editor of this publication until shortly before his death in 1837. A series of articles advocating Whig doctrines appeared in The Republican. Emmerson was so impressed with these articles that he convinced the author to give up the ministry and devote his life to journalism. Little did Emmerson suspect that he was unleashing a fury that would cause much dissension in the state of Tennessee. The author was William G. “Parson” Brownlow, who would soon make his name known nationally.

Inspired by Emmerson’s encouragement, Brownlow started his own newspaper, the Whig. As described by Wilma Dykeman in her history of Tennessee, Brownlow fought “the enemies of the Lord, who also happened to be his own adversaries: the devil, Baptists, Presbyterians, Democrats, and finally Confederates, possibly in ascending order of their error.”

Brownlow believed passionately in the federal government and therefore hated its opponents. “I expect to stand by this Union, and battle to sustain it, though Whiggery and Democracy, Slavery and Abolitionism, Southern rights and Northern wrongs, are all blown to the devil,” he wrote.

Given his support of the federal government, you might expect that Brownlow was an abolitionist, but he believed in slavery. That meant he hated Harriet Beecher Stowe: “She is ugly as Original sin—an abomination in the eyes of civilized people.”

On the other hand, he also hated the Confederate cause. Once, when he was asked if he might become a Confederate chaplain, Brownlow responded, “When I shall have made up my mind to go to hell, I will cut my throat, and go direct, and not travel round by way of the Southern Confederacy.”

And he certainly didn’t refrain from personal attacks. In his ongoing feud with Dr. Frederick A. Ross, a widely known Presbyterian minister in Kingsport, he went beyond discussion of doctrinal differences. For two years, Brownlow published The Jonesborough Weekly Review, or Frederick Augustus Ross as He Really Is, bitterly and viciously attacking Ross each week. After a year, this publication became a monthly. (For more information about Frederick A. Ross, see The Rogersville to Kingsport Tour, pages 153–54.)

But the Presbyterians were nowhere near as evil in his eyes as the Baptists: “When Presbyterians, Methodists, Episcopalians, and others, baptize either infants or adults, they introduce their subjects faces foremost. Our Baptist brethren are almost alone in their vulgarity in backing into the Church of God!”

Brownlow’s attacks weren’t limited to the written word. He and Landon C. Haynes hated each other so much that they came to blows in front of the Jonesborough courthouse in 1840. When friends separated the two, Brownlow had a bullet in his thigh, and Haynes’s head had been badly battered by the parson’s unfired pistol. (For more on Landon C. Haynes, see The First Frontier Tour, page 22.)

When the Civil War started, Brownlow was imprisoned by Confederate authorities, who offered him his release if he would leave East Tennessee. He answered, “Good! We will strike a bargain; give me your passport and a military escort and I promise you in return to do more for the Southern Confederacy than the devil has ever done—I will quit the country.”

And he did. Brownlow traveled to the North, where he launched a lecture and fundraising tour in the summer of 1862. To whip his audiences of Unionists into a proper gift-giving frenzy, he used demagoguery such as this: “Hanging is going on all over East Tennessee. They shoot Union men down in the fields; they whip them. . . . They actually lacerate with switches the bodies of females, wives and daughters of Union men.” It worked. The Relief of East Tennessee fund raised over $160,000 in northern cities.

And Brownlow thus had his bankroll for a new newspaper. Unionists controlled Tennessee by 1863, so that November the Knoxville Whig and Rebel Ventilator made its debut. Brownlow was not conciliatory in the least: “The mediation we shall advocate, is that of the cannon and the sword; and our motto is—no armistice on land or sea, until all the rebels, both front and rear, in arms, and in ambush are subjugated or exterminated!”

Imagine the feelings of Confederate sympathizers in Tennessee when they learned on April 5, 1865, that William G. Brownlow was their new governor. Brownlow’s biographer, E. M. Coulter, sums it up best: “It was a strange and dangerous act to set a person of Brownlow’s record to rule over a million people. In peaceful times it would have been perilous; in the confusion incident to the closing of a civil war, it might well seem preposterous.”

Given this climate, it is little wonder that the Ku Klux Klan was born in Pulaski, Tennessee, in December 1865. When Brownlow departed the governor’s office in 1869 to go to Washington as a senator, he left nine counties in middle and western Tennessee under martial law. Five companies of militia occupied the town of Pulaski alone.

When he died in 1877, many considered Brownlow a hero. However, judging him by today’s standards, with emotions removed, it appears his leadership only served to deepen the already harsh wounds of the citizens of Tennessee.

As you continue down Woodrow Avenue, you will see two houses on the left across the street from the old First Christian Church. The second of these is the Gresham-Landstrom House, which was Brownlow’s residence when he lived in Jonesborough and published his first newspaper, the Whig.

At the corner of Woodrow Avenue and Second Avenue is a historical marker for Alfred Martin Ray. On July 1, 1898, Lieutenant Ray planted the United States flag on San Juan Hill, Cuba, during the Spanish-American War. He served in the United States Army from 1872 to 1903, first in the Indian wars as a buffalo soldier in the Tenth United States Cavalry and later in Cuba and the Philippines. Born into slavery on the Ray Farm near here, he purchased property on Woodrow Avenue in 1904, when he retired from the military.

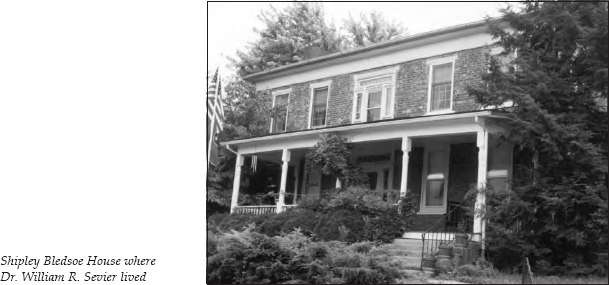

Turn around and retrace your route to the corner where the Gresham-Landstrom House is located. The other house on this corner, now on your right as you head back down Woodrow Avenue, is the Shipley Bledsoe House, the home of Dr. William R. Sevier, a nephew of John Sevier.

In July 1873, several cases of Asiatic cholera were reported in Greeneville. Most Jonesborough residents thought nothing would happen to them. When two sufferers came from Greeneville, they were cared for at the home of A. C. Collins. They recovered, but Mrs. Collins died four days later. When four railroad workers fell victim, three dying within hours, the epidemic was on.

Panic struck. Residents able to do so quickly fled. Of the seventy-five people left, sixty contracted the disease. Thirty died. Dr. Sevier was one of three doctors who chose to stay to care for the sick. The cause of cholera was unknown, as was any effective treatment. Those who didn’t die within a day or so recovered fully in a week.

Of the four ministers who stayed, one died. James Clark chose to remain as a member of the grave-digging force. Graves had to be dug in advance to keep up with the need. Clark was buried on July 30 in a grave he had dug the day before.

The disease disappeared as quickly as it had come. By August 6, no new cases were reported. In a short time, the residents who had fled returned.

Retrace your route onto Fox Street and to Main. Turn right onto Main Street and continue up Rocky Hill. At the top of the hill is the Old Jonesborough Cemetery. This four-acre plot, established in 1803, contains the graves of many of Jonesborough’s most illustrious citizens. The grassy crest of the hill is the site of trench graves dug for the unidentified victims of the cholera epidemic.

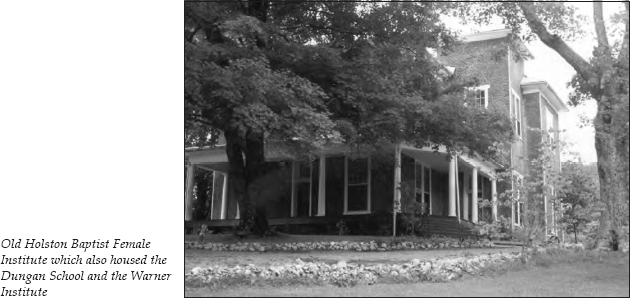

To the right of the cemetery gate is the Old Holston Baptist Female Institute. Encouraged by the success of local schools, the Holston Baptist Association agreed to sponsor an institute to educate young women. From the beginning, the venture was a success. The school’s 1854 catalog lists pupils from eight counties in East Tennessee. By 1858, the two-story brick building on top of Rocky Hill was finished. But the Civil War forced the school to close its doors.

A year or so after the war, Colonel R. H. Dungan purchased the property and opened the Holston Male Institute, more popularly known as the Dungan School. At a fifty-year reunion, one alumnus compared the school’s graduates with his later college classmates at Princeton:

As a group it [Dungan] is unexcelled. My class of 165 at Princeton does not approach it. None of the Dungan boys have committed suicide, four of my classmates did. None of the Dungan boys have been in prison. Some of my college mates have. Some of the Dungan boys have become possessed of millions; none of my New Jersey classmates have. Not one is dependent. Every man is a producer. Every man is connected with a religious organization. Some have known the evils of drink, but every man is sober today.

Now, there’s an endorsement!

In 1875, Colonel Dungan sold the building to the Society of Friends, which was interested in educating the recently freed slaves. The Warner Institute opened for that purpose and continued in operation until the turn of the twentieth century.

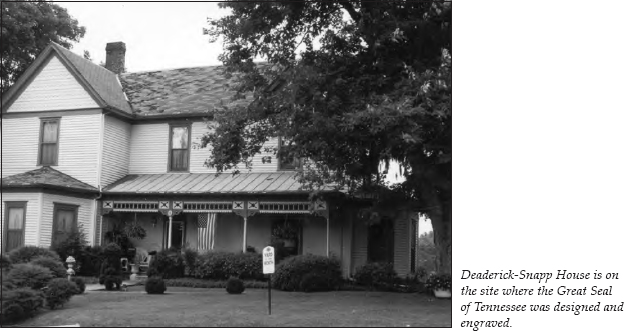

The home on the other side of the cemetery is the Deaderick-Snapp House, the site of the silversmith shop of William and Matthew Atkinson, who designed and engraved the Great Seal of the State of Tennessee. Though the Tennessee constitution authorized a seal, the legislature never got around to having one made. Governor John Sevier had to use his personal seal during his three terms in office. It wasn’t until 1802 that Archibald Roane, the state’s second governor, finally got an official seal.

Retrace your route down Rocky Hill, following Main Street to downtown Jonesborough. This ends the tour. You may wish to combine this tour with The Jonesborough to Greeneville to Bulls Gap Tour, which begins at this location.