The Jonesborough to Greeneville to Bulls Gap Tour

This tour begins in Jonesborough and follows the path of the Great Stage Road past DeVault Tavern to Telford, Washington College, Limestone, and Davy Crockett Birthplace State Park. From there, it continues to Chuckey, Earnest, and Tusculum. In Greeneville, the route covers the town’s historic district. The tour then proceeds to Warrensburg and Russellville before ending at Bulls Gap.

Total mileage: approximately 80 miles.

The historic district in downtown Jonesborough is explored in The Bristol to Blountville to Jonesborough Tour. This tour begins where that tour ends—in front of the Washington County Courthouse on Main Street.

Turn right, or north, onto TN 81 a few blocks west of the courthouse. Just ahead on the right is a historical marker for the home of Alfred Eugene Jackson.

Prior to the Civil War, Jackson was a successful businessman in the area. In 1863, he was commissioned a brigadier general in the Confederate army, becoming the only Washington County man to attain the rank of general on either side. Jackson commanded troops in upper East Tennessee, southwestern Virginia, and western North Carolina. To distinguish him from Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson, Alfred was given the nickname “Mudwall.” One of the units in Jackson’s brigade was Thomas’s Legion, described later in this chapter.

After the war, Jackson continued as a successful businessman. He was one of the major promoters of the East Tennessee and Virginia Railroad. When the original depot burned in 1887, Jackson offered land for a depot, which was built in 1888.

Follow TN 81 north past the historical marker. At the corner, TN 81 turns left onto College Street and heads out of Jonesborough. It is approximately 2.5 miles to a left turn onto Old Stagecoach Road. In case the road sign is not there, note that the Farmstead development is ahead on the right. If you reach the development, you’ve gone too far.

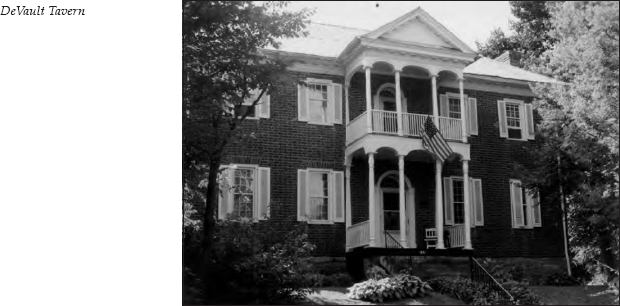

It is 2 miles on Old Stagecoach Road to DeVault Tavern, on the left. This two-story brick home, built in 1821 by Frederick DeVault, was a stopping place for stage passengers until the coming of the railroad in 1857 put the stages out of business. Andrew Johnson, a personal friend of the DeVaults, was a frequent guest. General John H. Morgan, the famed Confederate cavalry leader, spent the night before his death here. More about Morgan’s death will be presented later in this tour.

It is 0.1 mile past the tavern to the intersection with Leesburg Road. Turn left onto Leesburg Road. It is 2.2 miles to the intersection with the four-lane U.S. 11E. Cross that highway. Directly across U.S. 11E, the road you are traveling becomes Telford Road. It is 1.3 miles to the town of Telford. Just before reaching Old S.R. 34, turn right onto Mill Street, which runs parallel to Old S.R. 34. You are traveling alongside Little Limestone Creek. At one time, the Eureka Roller Mill was on the right; you can still see where the waterwheel used to be. Mill Street then runs back into Old S.R. 34. Turn right onto Old S.R. 34. It is 1 mile to Matthews Mill Road, on the right. A short drive on Matthews Mill Road will bring you to the Thomas Embree House; this home can also be seen in the distance without leaving Old S.R. 34.

In 1791, Seth Smith, a Pennsylvania stonemason, built this house for Thomas Embree. Smith also constructed several other architecturally distinctive stone houses in the area.

Embree, a Quaker from Pennsylvania, operated a small iron furnace just west of Telford. In 1797, he published an advertisement in the Knoxville Gazette announcing a meeting to

form a society, similar to those instituted in Philadelphia, Baltimore, Richmond, Winchester and other places, for the relief of those fellow creacher [sic] as are illegally held in bondage, to effect their relief by legal means. Alone, without any intention to injure the rights of individuals not to take Negroes from their legal masters and set them free, as some have vainly imagined, but by lawful means to vindicate the cause of such of the human race as are lawfully entitled to freedom, either by mixed blood or any other cause.

It is not known if anything came of Embree’s efforts, but his son Elihu kept up the work twenty years later when he published The Manumission Intelligencer and The Emancipator. Both of Embree’s sons followed their father into the iron-furnace business. (For more information about Elihu and Elijah Embree, see The Beauty Spot to Nolichucky Tour, pages 65–66, and The Bristol to Blountville to Jonesborough Tour, page 94.)

The stone house at Telford was also the site of a Civil War skirmish involving Colonel William Holland Thomas’s Legion of Indians and Highlanders, more commonly referred to as Thomas’s Legion.

Will Thomas was the son of white settlers who lived near Waynesville, North Carolina. His father died shortly before Thomas’s birth. By age twelve, Thomas was working in a local trading store. There, he became friends with Drowning Bear, the chief of the Cherokees along the Oconaluftee River. Drowning Bear adopted “Little Will”—so named because he stood only five foot four—into the tribe as his son. From that point, Little Will’s destiny became permanently intertwined with that of the Eastern Band of the Cherokees.

Will Thomas was a wheeler-dealer if there ever was one. His financial doings have led many recent historians to question his motives when dealing with the Cherokees, but it seems that negligence was the culprit as often as malevolence. Thomas did become a real-estate tycoon, eventually acquiring at least a hundred thousand acres of mountain land, yet this just left him land-poor. He also ran a chain of stores near the Cherokee villages, but these profited as much from the soldiers who came to speed up the Removal as from the Cherokees themselves.

In 1831, the Cherokees appointed Thomas their legal representative. At that time, the Indians were under intense pressure to accept the terms of the Treaty of New Echota and leave the mountains. From 1836 to 1860, Thomas was the Washington lobbyist for the group associated with Drowning Bear and was instrumental in gaining a concession that the Eastern Band be allowed to remain in the North Carolina mountains. Some sources say Thomas sacrificed the renegade warrior Tsali to gain this concession, but there is little doubt his intervention helped to bring the long struggle to an end.

When Drowning Bear died in 1838, Thomas became chief of the tribe. He remained active in state politics as well. Ironically, when the Civil War broke out, Thomas returned to the mountains to convince the Indians to take up arms against the “demons” in Washington, even though he had implored them for years to be loyal to those same people.

On April 9, 1862, Thomas’s Legion was officially mustered. A few days later, 130 men marched to Knoxville and created quite a sensation among the townspeople. One of the unit’s second lieutenants was Astoogatogeh (also spelled several other ways), the grandson of the great chief Junaluska. When the unit settled near Strawberry Plains two weeks later, the men named their permanent headquarters Camp Junaluska.

Thomas’s troops were formally organized as a regiment on September 27. The man chosen as second-in-command was James R. Love, the grandson of Colonel Robert Love. (See The Beauty Spot to Nolichucky Tour, pages 60–62, for more about Robert Love.) Another one of the colonel’s grandchildren, Sarah Love, was Will Thomas’s wife.

By March 1863, the legion had established quite a reputation as a fierce fighting force. (For information about how it attained this reputation, see The Dandridge to Sevierville Tour, page 252.) Upon returning from maneuvers in western North Carolina, it discovered that an unpopular turn of events had occurred in its absence—Alfred “Mudwall” Jackson had become its official commander. Such action stripped Thomas of practically all authority except what Jackson chose to give him. Hostility between the two men was inevitable.

In November 1862, Thomas had enlisted one hundred miners in his service with the promise that they would not have to bear arms. He used them as engineers, carpenters, blacksmiths, and gunsmiths. One of the first orders Jackson gave was that the miners should bear arms. Most immediately deserted, just as Thomas predicted.

Many of the men in Thomas’s Legion went home often to check on their families, and Thomas did nothing to check their disappearances. Jackson considered this an outrage. By August 1863, Jackson had Thomas arrested for insubordination. A court-martial was never held because the Confederate forces were too busy with General Ambrose Burnside. But Jackson named James Love colonel of the legion in September 1863.

Under Love’s command, the legion found itself engaged in a large-scale battle. On September 5, the 100th Ohio Infantry moved into Jonesborough. Jackson stationed Love’s regiment at Carter’s Depot and directed, “Urge the holding of Carter’s Depot at all hazard. . . . Reinforcements are coming.” Love replied, “Push forward the cavalry and let us have some fighting.”

On September 8, Love got his wish. The Ohio regiment pulled back to Telford and dug in. Meanwhile, Jackson gathered his forces. He ordered Love to lead the attack. So fired up were the mountaineers that their first charge broke the Federal line and sent the Ohioans back down the railroad tracks. The Yankees rallied, anchoring their defense around the Thomas Embree House. By the end of the battle, 50 Federal troops were either killed or wounded and 350 taken prisoner. The Confederates counted only 20 casualties. But equally important was the capture of four hundred modern rifles.

One more interesting side note about the Thomas Embree House is that Sarah Hawkins, the first wife of John Sevier, is said to be buried near the home.

Continue 1.9 miles on Old S.R. 34 to Washington College; you will see a sign announcing Washington College Academy just before the campus appears on a hill on the left. It is 0.1 mile past the sign to the Salem Cemetery entrance. Turn into the cemetery. At the top of the hill is a large monument marking the grave of Samuel Doak.

After graduating from Princeton College in 1775, Doak came to the frontier as a Presbyterian minister in 1777, preaching at New Bethel Presbyterian Church (see The Bristol to Blountville to Jonesborough Tour, pages 84–85). By 1780, he founded Salem Presbyterian Church, which still stands on the campus of Washington College Academy. The church was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1992.

An interesting story tells how Doak selected this particular spot. He was supposedly riding through the forest that then covered the area when he met some settlers who were felling trees. When they learned he was a minister, they asked him to preach a sermon to as many as they could call together. Doak supposedly used his horse as a pulpit and the grove as a sanctuary. The sermon pleased the hastily assembled congregation so much that the people implored him to stay. He agreed and purchased a farm that now encompasses the church, school, and cemetery.

Doak was adamant about education. Tradition says he brought the first books into this area. In fact, the books rode on his horse while he walked alongside, which says something about his priorities.

By 1784, the North Carolina legislature chartered his school, which he called The Martin Academy. In 1795, Doak’s school was chartered again, by the territorial government of William Blount. This time, it was named Washington College in honor of George Washington. Doak continued to preside over the college until 1818.

Even more important than his teaching duties were his ministerial obligations. Doak formed the Salem congregation in 1780. That same year, he also formed the congregations of New Providence, Carter’s Valley, and Mount Bethel. Mount Bethel Church, located in neighboring Greene County, was the home church of Dr. Hezekiah Balch, the founder of Greeneville College. When Doak resigned his presidency of Washington College in 1818, he moved to Mount Bethel Church. There, he united with his son in conducting a classical school, which later became Tusculum College. More about Tusculum College is presented later in this tour.

During Doak’s tenure at Salem Church, he and his family suffered many hardships. The Cherokees were still hostile during this period, and it was not uncommon to end services abruptly to defend neighbors against raids. On one occasion while Doak was away, his wife noticed a band of warriors approaching. She snatched up their child and fled to a hiding place, from which she witnessed the burning of their home.

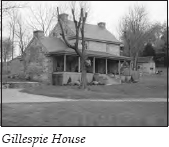

Just past the cemetery, TN 353 goes off to the left. Do not turn. Continue straight on Old S.R. 34, heading toward Limestone. It is 3.6 miles to a ninety-degree left turn at the Limestone fire station. Limestone’s small business district is on the right. Just before the road curves to the right and heads under a railroad bridge, you can see the Gillespie House on the left. Otherwise known as “the Old Stone House,” this home is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. It was in a sad state of disrepair when the first edition of this book was written. Fortunately, it has since been beautifully restored.

George Gillespie was one of the earliest settlers in this area, arriving in 1772. He was one of the signers of the petition sent to the North Carolina legislature asking for separation from that state. This document was the beginning of the State of Franklin movement.

Because this area stood on the frontier, a fort was built here, and the settlement was given the name Gillespie’s Station. J. M. A. Ramsey notes in his Annals of Tennessee History, published in 1854, that Indian raiders often attacked this fort. He writes this about an attack in 1776:

Another division of the Cherokees invaded the settlements. This was commanded by old Abraham of Chilhowie. He led the division along the foot of the mountains by the Nollichucky [sic] path, hoping to surprise and massacre the unsuspecting and unprotected inhabitants upon the river. The little garrison at Gillespie’s station appraised [sic] of the impending danger had prudently broken up their fort and withdrawn to Watauga, taking with them such of their movable effects as the emergency allowed, but leaving their cabins, their growing stock on the range to the devastation of the invaders.

(For more information about the Cherokee hostilities of 1776, see The Rogersville to Kingsport Tour, pages 156–58.)

In 1792, Seth Smith, the busy Pennsylvania stonemason, built this home for Gillespie on the site of the former fort. The foundation is thirty inches thick, the first-floor walls twenty-four inches, and the second-story walls eighteen inches. About five feet from the floor are small, partly filled apertures that probably served as musket loopholes. Judging from Ramsey’s account, these features were an important part of the house’s architecture.

Just past the Gillespie House, turn left before going under the railroad bridge, following the signs to Davy Crockett Birthplace State Park. You are now on Davy Crockett Road, which parallels Big Limestone Creek. It is 1.3 miles to an intersection; turn right onto Keebler Road. It is 0.2 mile to the Snapp Inn, on the left. This structure, built in 1815, is considered one of the area’s finest examples of a Federal plantation house.

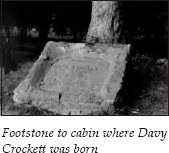

Continue 0.5 mile to the entrance to the state park, on the left. The park has excellent camping and picnic facilities, a swimming pool, a visitor center and museum, and a historical reproduction of the cabin in which Crockett was born. During the Crockett craze of the 1950s, which grew out of Fess Parker’s portrayal of “the King of the Wild Frontier,” the Davy Crockett Birthplace Association built a replica of the log cabin. This replica was eventually replaced by the present structure, which is a more historically accurate reconstruction of the birthplace. In front of the cabin is an engraved marker encased in what is supposedly the footstone of the original cabin. The engraving on the marker has been traced to 1886, the time of Crockett’s hundredth birthday celebration. All of this is nestled picturesquely alongside the creek. Another interesting feature of the park is a wall erected in the late 1960s. Incorporated into this circular wall is a native stone from each state in the country. The wall surrounds a memorial to Crockett, who, the inscription says, was “martyred at the Alamo.”

Thanks largely to Walt Disney, the legend of Davy Crockett looms large in American folklore. The actual man never called himself or signed his name Davy Crockett; he was always David Crockett. Disney’s conditioning must have worked, because it just doesn’t sound right to call him David.

Crockett’s grandparents originally moved to Rogersville, where they were killed during an Indian raid. Davy’s father, John Crockett, moved to Greene County, where Davy was born in 1786, the fifth son among six boys and three girls. When Davy was probably five or six years old, his father built a mill on Cove Creek. The mill and the family’s home subsequently washed away in a flood. The family then moved to Jefferson County, where John Crockett operated a tavern outside what is now Morristown.

Davy spent much of his adolescence away from home, working odd jobs. He married Polly Finley in 1806 and by 1809 had two sons. In 1811, he moved farther west, to middle Tennessee. By 1817, he moved even farther onto the frontier, to western Tennessee. There, he began his political career. By its end, he had served at various times as the representative of seven counties in the lower house of the Tennessee General Assembly and as the representative of eighteen counties in the United States House of Representatives.

Crockett played the eccentricities of the backwoodsman’s speech and dress to the hilt. He had great stories about his hunting exploits, when he was accompanied only by his long rifle, Old Betsy. He told of one occasion when he spent an entire night climbing up and down a tree to keep from freezing to death. Another time, when he was caught in a hollow tree by a mother bear, he held to the furious animal’s tail and prodded her hams with his hunting knife until she pulled him out. He also told of being trapped in a huge crack in the earth, where he fought hand-to-claw with a vicious black bear until he stabbed it to death.

But Crockett ran into political trouble when he bucked the Jacksonians over a proposal to sell all vacant federal lands in Tennessee to “squatters.” He also opposed Jackson’s Indian removal bill in 1830. Crockett admitted he did not know anyone within 500 miles of his home who would have voted the way he did on the Indian removal bill, but he believed the United States was bound by treaty to protect the Indians. He simply would not vote to “remove them in the manner proposed.” He was defeated in his election bid in 1835.

In describing one of his last speeches to his constituents, Crockett reported, “I concluded my speech by telling them that I was done with politics for the present, and that they might all go to hell, and I would go to Texas.” And go he did, on November 1, 1835.

He arrived in San Antonio in February 1836 and joined 180 other volunteers assigned to the former Mission San Antonio de Valero, more popularly known as the Alamo. On March 6, Mexican general Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna attacked the fortress. For eleven days, the volunteers withstood the Mexican army. When the battle was finished, all of the forces inside the Alamo were dead. But before their death, they had reportedly killed over 2,000 of the Mexican soldiers. Crockett was forty-nine years old. The myth was complete.

After leaving the campground, turn left at the park entrance. It is 0.2 mile to a three-way intersection. Turn left onto Charles Johnson Road. It is 1.8 miles to the intersection with TN 351, which is also Earnest Bridge Road. This is the community of Chuckey.

On the right, you can see the old depot, listed on the National Register of Historic Places. When Chuckey was chosen for a railroad depot, its prosperity was assured. Turn right for a brief tour of the community. Behind the depot on the hill is an interesting structure. Built as a bank, it was later used as the Chuckey post office.

As you climb the hill, you will see a large brick home on the right beside Chuckey Methodist Church. In the 1870s, the Reverend J. B. Fitzgerald moved to this community, which was then called Fullen. He built the beautiful brick home on the hillside next to the church. Soon after arriving, Fitzgerald organized a Methodist church and a school, donating land for both the buildings and the adjacent cemetery. That church—now Chuckey Methodist Church—was constructed in 1880. It was first called Alice’s Chapel, in memory of Fitzgerald’s youngest daughter. Her funeral was the first one held in the newly completed sanctuary.

In 1883, the school building was erected. The school was first called Warren College. The name vacillated between Warren College and Wesleyan Academy, but by 1909 Wesleyan Academy seems to have won out.

In 1900, the school had an enrollment of 103. It is interesting to note that one member of the board was Abner Johnson, an African-American. A girls’ dormitory was added in 1905. By 1908, the enrollment increased to 213.

Judging from its catalog, the school was liberal for its time. School authorities did not enforce the strict discipline associated with most church-affiliated schools: “All students are kindly admonished (not required) to attend church.” The catalog also makes this statement regarding discipline: “It is presumed that every student knows RIGHT from WRONG and has an intelligent idea of which should be chosen. . . . Students are human beings, and are appealed to through a mutually humane feeling, to conduct themselves as ladies and gentlemen should.”

But the public schools were quickly taking over the responsibilities of the private academies. In 1914, the property was purchased from the Methodists, and Chuckey High School moved into the building.

Take the road to the right, which leads up to Chuckey Methodist Church. This road makes a loop to another church, sometimes called the Block Church. In 1910, the local Southern Methodist congregation built this church. When the Northern and Southern Methodists united, the Presbyterians purchased it.

Turn left and head back down the hill to the depot. Continue on TN 351 South, or Earnest Bridge Road. It is 0.6 mile to the Mica P. Earnest Bridge, which crosses the Nolichucky River. On the right just before the bridge, you’ll see the Earnest Fort House. This home was built between 1780 and 1783. The first story is of stone and the upper stories of log. The home features an imposing stone chimney. It was called a fort house because settlers gathered here for protection against Indian raids. This is one of the oldest houses in Tennessee.

Across the Nolichucky River stands another Earnest home, built in the 1820s. The woodwork inside, said to be some of the finest in the area, was reputedly done by an itinerant English carver who paid for a year’s board bill with his handiwork.

Henry Earnest settled in this area around 1778. His family was active in establishing one of the oldest Methodist congregations in Tennessee—some sources say the oldest. Records indicate that the first local Methodist society was formed around 1790, the Henry Earnest family constituting four-fifths of the congregation. This congregation’s log-cabin church, known as Ebenezer Church, was dedicated by Bishop Francis Asbury in 1795.

Bishop Asbury visited on several occasions. He was one of the circuit riders who traveled all over the early American frontier, establishing Methodist congregations. It is said that he traveled over three hundred thousand miles, preached an estimated seventeen thousand sermons, ordained over four thousand ministers, crossed the Appalachians sixty times, and at his death claimed over four hundred congregations totaling over two hundred thousand members. In his journal, he once wrote, “My horse trots stiff, and no wonder when I have ridden him upon an average of 5,000 miles a year for 5 years successively.”

If you wish to take a side trip to see the historic Ebenezer Methodist Church, travel 2.1 miles past the Earnest home to Ebenezer Road and turn right. Turn right again when the road ends at the river 0.8 mile later. The church is straight ahead.

After viewing the church, continue on TN 351, also known as Chuckey Road, for 2.8 miles to the intersection with TN 107. Turn right, heading toward Greeneville. It is 2.8 miles to the Nolichucky River. Just before crossing the river on the Kinser Bridge, you will see a monument to Sergeant Elbert Kinser on the right. Kinser, killed during the fighting on Okinawa on May 4, 1945, received the Congressional Medal of Honor. He was the leader of a marine rifle platoon. When Japanese forces attacked, Kinser engaged the enemy in a fierce hand-grenade battle. When a grenade landed nearby, he threw himself on it, absorbing the explosion and saving his men at the expense of his own life.

Continue on TN 107 for 1.2 miles. Turn left as the road becomes a four-lane highway. Follow the signs to Tusculum College, ahead on the left.

In 1818, after Dr. Samuel Doak resigned the presidency of Washington College, he joined his son, Samuel Witherspoon Doak, in opening a private school named Tusculum Academy. Tradition says the academy was named after the home of Dr. John Witherspoon, the president of Princeton when the elder Doak attended school there. Witherspoon took the name from that of Cicero’s villa outside Rome.

To distinguish between the two Samuel Doaks, most sources call the father Dr. Doak and the son the Reverend Doak. When Dr. Doak died in 1829, the school’s operations were suspended. But the Reverend Doak reopened Tusculum Academy in 1835 with four students. By 1840, attendance had risen to seventy. In 1868, Tusculum merged with Greeneville College, founded in 1794 by Hezekiah Balch, to become what is now Tusculum College.

The campus was designated the Tusculum College Historic District in 1980. Eight of the buildings and the stone archway marking the main entrance were constructed between 1841 and 1928.

The oldest building on campus is the Samuel Doak House, begun in 1818 by the Reverend Doak for his father. Dr. Doak lived in this house until his death. The next oldest structure, called Old College, was built in 1841. Classes were held in the Samuel Doak House until this structure was completed. Tradition says the building was constructed by slaves owned by the Reverend Doak. When it was completed, he supposedly gave them their freedom.

The next burst of construction came courtesy of a benevolent patron. McCormick Hall, erected in 1887, was named in honor of Cyrus McCormick of International Harvester fame. It was not Cyrus but his wife, Nettie Fowler McCormick, who proved to be one of Tusculum’s most important benefactors. Mrs. McCormick donated funds for the building of Craig Hall in 1891. It was named in honor of Dr. Willis G. Craig, her pastor in Chicago, who had been influential in bringing Tusculum to her attention. Mrs. McCormick admired small schools in rural settings. She never forgot that two of her sons had taken up smoking at Princeton at what she regarded as an excessively young age, so she was looking for small, rural schools to support. She especially liked hearing that many Tusculum students brought food from their farms, which they prepared in humble cabins that were kept clean and orderly.

Mrs. McCormick’s contributions also led to the erection of Virginia Hall in 1901. Named for her daughter, this is one of only three buildings in the South designed by famed architect Louis A. Sullivan. Virginia Hall enabled the college to establish a program in domestic science, with a focus on cooking, sewing, and household management. Mrs. McCormick sponsored instructors in this discipline for several years. Her biographer notes that the first instructor showed “what each teacher could do in her own kitchen with her own little mountaineers.” This seems a bit patronizing by today’s standards, but there is no doubt that Mrs. McCormick kept the school alive.

For a quick drive through the campus, take the first left past the stone archway. Behind the archway is McCormick Hall. As the road curves to the left, you will see the Old College building on your left. It now houses the President Andrew Johnson Museum and Library. Supposedly, Johnson made a twenty-dollar donation to the construction fund—one of the largest local donations, according to the minutes of the board of trustees. Craig Hall is on the left as you approach the quadrangle drive. Turn left to go behind McCormick Hall, then turn left to head back to the highway. Virginia Hall is on the right.

When you reach TN 107 again, turn left. You will see the Samuel Doak House, or the Doak House Museum, on the left just as you pass the road you took around the campus.

Just after crossing a small bridge, turn left onto Old Tusculum Road, which winds through a residential area for 1.9 miles before joining Tusculum Boulevard at a stoplight in front of a shopping center. You have now entered the Greeneville city limits.

Turn left onto Tusculum Boulevard. This road passes through a congested commercial district. You will see brown signs directing you to the Andrew Johnson Visitors Center. You will also pass under a sign across the road proclaiming, “Ye Olde Town Gate.”

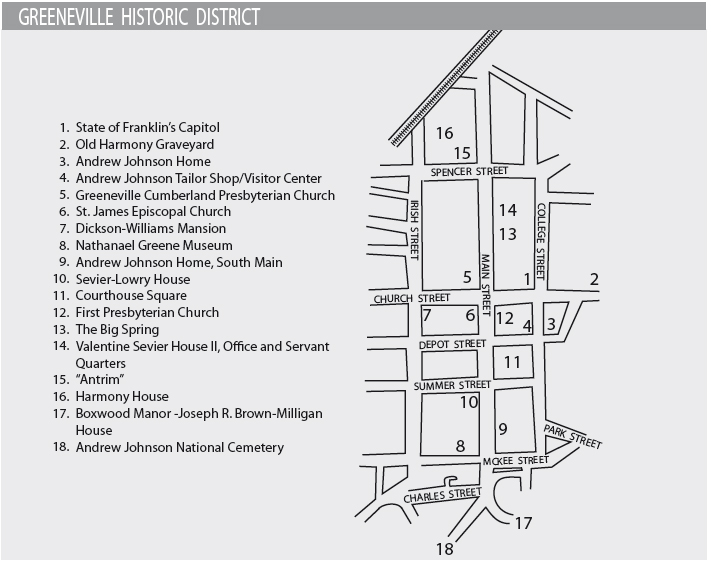

Just before reaching College Street, you will see a performing-arts center and high school on the left. After you turn left onto College Street, the Greeneville/Greene County Center for Higher Education will be on the right. Head up the hill. On the right is a log-cabin replica of the capitol of the State of Franklin as it looked when Greeneville was the seat of that government from 1785 to 1788. (For more information about the State of Franklin, see The Beauty Spot to Nolichucky Tour, pages 68–70.)

At the corner of College and Church streets is a historical marker indicating that Benjamin Lundy published his monthly paper devoted to the abolition of slavery, Genius of Universal Emancipation, at this location from 1822 to 1824. After 1824, Genius was published in Baltimore. The town hall now stands here. This corner was also the site of Greeneville’s first Presbyterian church and Judge Sam Milligan’s home, which General James Longstreet used as his headquarters during his stay in Greeneville.

Turn left onto Church Street. Behind the town hall is Old Harmony Graveyard. Many of Greeneville’s prominent early citizens, including Dr. Hezekiah Balch and Dr. Charles Coffin, are buried here. Balch and Coffin were two of the figures in a complicated religious controversy that involved some of Greene County’s most influential settlers.

Dr. Samuel Doak formed the Mount Bethel Presbyterian congregation in Greeneville in 1780. By 1783, he was joined by Dr. Balch. The congregation often met under a clump of oaks near the Big Spring in Greeneville. In 1794, Dr. Balch founded the first college chartered west of the Alleghany Mountains—Greeneville College. It was located on a farm he owned 3 miles south of town.

While visiting New England in the interest of the college in 1795, Dr. Balch met with adherents of a new theology known as “Hopkinsianism” or “New Divinity.” Without elaborating on the theological issues, suffice it to say that Dr. Balch returned to Greeneville ready to preach the new gospel. He was not warmly received, especially by Dr. Doak.

Balch was continually brought to task before ecclesiastical bodies, often due to charges presented by Doak. Their animosity was so great that a story is told about a day they chanced to meet on a muddy street crossing in Greeneville. One lone plank passed over a particularly muddy spot. Doak, who spoke first, said, “I never make way for the devil.” Balch replied, “I do,” and stepped aside in the mud to let Doak pass.

All of this controversy caused great turmoil in Dr. Balch’s congregation. At one point, the doors of the church were locked against him, so he preached for three months under the trees bordering the graveyard. By 1798, the church officially split. The party that followed Dr. Balch adopted the name of Harmony Church—quite an irony—and retained possession of the old house of worship. James Witherspoon, a student of Dr. Doak’s at Washington College, was installed as pastor over the other faction, which included all the elders and most of the members. Witherspoon’s congregation took the old name of Mount Bethel.

In 1800, Dr. Charles Coffin, the third member of what historian R. H. Doughty calls “the Great Triumvirate of Presbyterian Divines,” joined Dr. Balch at Greeneville College. Coffin had graduated from Harvard at age eighteen. By all accounts the most conciliatory of the three “Divines,” he was respected by those on both sides of the controversy.

By 1805, Balch relinquished one-third of his preaching duties to Coffin. Two years later, he withdrew entirely.

A meeting of the trustees of Greeneville College was held following Dr. Balch’s death in 1810. The minutes simply say, “The disposition of Divine Providence having occasioned a vacancy in the office of the President of the College, the Board unanimously elects the Rev. Charles Coffin President of Greeneville College.” It was not much of a tribute to a founder.

By 1815, Mount Bethel moved to the “country,” a mile east of town. Coffin, who led Harmony until 1820, saw that congregation grow. In 1840, it requested that the name Harmony be changed to Greeneville Church. Today, the congregation is associated with First Presbyterian Church.

The graves of Balch and Coffin rest in the far corner of Old Harmony Graveyard. Before his death, Balch made a special request to be interred here. This was where he had preached to his people in the open air while barred from using his church. He said it was from this place that he wished to rise on the morning of Judgment Day.

Across from the cemetery, turn onto Academy Street, which becomes Depot Street. The parking lot for Andrew Johnson National Historic Site is on the next corner. In front of the parking lot is Johnson’s first home in Greeneville. Across College Street is the visitor center. Inside the center is a replica of Johnson’s tailor shop.

One of the highlights of the museum is a reward poster for Johnson from the days when he was apprenticed as a tailor in Raleigh, North Carolina. Just before the end of his period of service, Johnson secured work elsewhere. He offered reparation, but his master wanted a bond against loss, which Johnson could not give. Johnson left for the West. The tailor put out a reward for his return, which was never collected.

Johnson was eighteen years old when he came to Greeneville in 1826 with his mother and stepfather. It was a simple matter of fate that the family stopped here to rest. Johnson struck up a conversation with a local merchant named John A. Brown. Brown convinced him to stay, since the only tailor in town was getting old. As a further inducement, Brown commissioned Johnson to make him a suit. Johnson’s first suit as a Tennessee tailor is on display at the museum.

In 1827, he married Eliza McCardle, the daughter of the local shoemaker. He was nineteen, and she was seventeen. The cabin across from the visitor center was their first home.

In 1829, Johnson was elected an alderman. By 1843, he was elected to Congress, where he served until 1853. He next served as governor of Tennessee from 1853 to 1857. On the day of Johnson’s inauguration, the retiring governor called at his hotel to take him to the ceremonies in a carriage. Johnson declined the carriage ride, saying he was “going to walk with the people.” One of his first acts as governor was to request a “tax of 25 cents on the polls, and two and a half cents on the hundred dollars, of all the taxable property of the State . . . for the common schools.” No doubt, he remembered his own struggle to gain an education.

Johnson then served in the United States Senate from 1857 to 1862. He was the only southern senator to remain in Congress after the outbreak of the Civil War. In 1862, when Union forces took possession of most of Tennessee, Abraham Lincoln appointed Johnson the military governor. In 1865, he became vice president of the United States and succeeded to the presidency upon Lincoln’s death a short time later.

His tenure as president was a stormy one. Johnson was bitterly opposed by the radical Republicans who dominated Congress. The House brought impeachment proceedings against him, but the vote fell one short of the two-thirds majority required for removal from office. Johnson returned to the Senate in 1875, where he served until his death six months later. He remains the only person to serve in the Senate after being president.

The visitor center is a good place to park your car if you wish to take a walking tour. Since the historic district is also a busy commercial area, a walking tour offers some advantages. Check at the visitor center to see if it still supplies brochures about the historic district. At one point, guided tours of the district were also offered.

Retrace your route on Depot Street to Old Harmony Graveyard. Turn left onto Church Street. You will pass the town hall. Continue to the corner of Church and Main streets. On that corner is Greeneville Cumberland Presbyterian Church, founded in 1841. The present church was begun in 1860 on land purchased from Andrew Johnson. Used as both a hospital and a stable during the Civil War, it was caught in the crossfire on the day General John Morgan was trapped in Greeneville. The cannonball in the facade is evidence of this skirmish.

Continue on Church Street. On the left, you will see St. James Episcopal Church, completed in 1850. The interior is noteworthy for its walnut woodwork and pews and its slave gallery. It also boasts the oldest organ in the state of Tennessee. The organ cost four hundred dollars and was built in Baltimore. Paul Rosenblatt, who had recently come to Greeneville from Saxony, assembled the organ upon its arrival and kept it tuned without charge until his death.

An interesting anecdote about the organ involves Mary Lincoln. At age thirteen, she knitted a bag, which she hoped to sell for the organ fund. William R. Brown observed her work and told her that he would buy the bag upon completion. Mary sent it to his store when she was finished, but it was returned with twenty dollars in gold—the beginning of the organ fund. In 1852, William R. Brown and Mary Lincoln were married in the first wedding performed in St. James Episcopal Church.

In front of St. James is a historical marker describing the death of General John H. Morgan, the famed leader of the Confederate cavalry unit known as Morgan’s Raiders. Morgan had such nicknames as “the Thunderbolt of the Confederacy” and “the Wizard of the Saddle.” Depending on your loyalties, Morgan’s raid through Kentucky, Indiana, and Ohio was either an act of daring bravery or the work of a bunch of outlaws unleashed on the countryside. Morgan made a second and third raid into Kentucky, but the third was unsuccessful—he entered the state with twenty-six hundred men and left with only seven hundred stragglers.

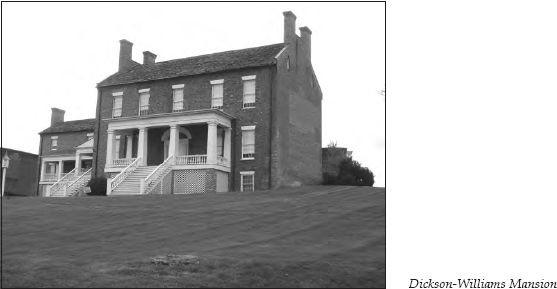

It was in this declining state that Morgan and his men arrived in Greeneville on September 3, 1864, during a cold and bitter rain. He and his officers established their headquarters at the home of a friend, Mrs. Catharine Williams. That home, the Dickson-Williams Mansion, was begun in 1815 and finished in 1821. William Dickson built “the showplace of East Tennessee” for his only child, Catharine, who was married to Dr. Alexander Williams. The mansion was designed after a country home in Ireland. The circular staircase rose three full flights. The house, surrounded by formal gardens and occupying an entire block, was the site of many balls and receptions, the guest lists including the likes of Davy Crockett, President James K. Polk, Henry Clay, Frances Hodgson Burnett, the Marquis de Lafayette, and, of course, on this fateful night, General John Morgan.

Federal troops led by General Alvan Gillem were staying in nearby Bulls Gap. Several accounts tell how they learned that Morgan was in the area. The most romantic version says that Morgan was betrayed by Mrs. Williams’s own daughter-in-law. This version says Lucy Williams left the very supper table where Morgan was being entertained and stole away to alert Gillem.

An account supposedly written by “an acquaintance” of Mrs. Williams appeared in the Knoxville newspaper a few weeks later. Many were willing to place the blame at Lucy’s feet, as this account attests: “Perhaps it would be pleasing to your readers to give a few facts concerning the creature that was bold and base enough to betray the chivalrous Morgan. . . . Lucy was a good looking girl, but forwardly inclined. As she grew, her faults increased in inverse ratio to her graces; and at seventeen little complimentary could be said of her beyond her mere personal(ity). . . . She loved dancing and card playing and was noted as a reckless rider.”

What a hussy!

It is highly improbable that Lucy was the traitor, because even at her divorce proceedings years later, her husband testified that she had been somewhere else on the night in question. Union reports attributed the intelligence information about Morgan’s whereabouts to a young boy who had been stopped earlier that day by Morgan’s men.

Whatever the source of betrayal, Gillem, after some prodding from his subordinates, moved out during the rainy night with somewhere between a thousand and two thousand men, depending on the account. He sent a small group of Tennessee cavalry down the back way on the Newport-Warrensburg Road. The principal force continued on the main road between Bulls Gap and Greeneville. Some sources say the sentries on the Newport Road were asleep, while others say they mistook the force for Confederate troops in the dark. Either way, the Federal forces gained easy entry into town.

The following account, supposedly based on the report of Major W. D. Williams—one of Catharine Williams’s sons, who was serving on Morgan’s staff—is one of the best versions of what transpired, even if it is not objective:

When the Federals dashed into the town [Major Williams] ran upstairs to the General’s room and cried, “For God’s sake, General, get out of here, the town is full of Yankees!” The general hurriedly put on his trousers and socks, threw his pistols over his shoulders, ran down the stairs and out the back door into the thick foliage of the yard. Seeing Mrs. Williams, as he passed out the door he gave a military salute and smilingly said, “Goodbye, Mrs. Williams, I am all right now.” The enemy was then at the front door. He ran down to the Episcopal Church, but seeing the street was guarded by soldiers, he turned and ran back into the garden. The notorious Mrs. Fry [whose husband, David, was a prisoner of war in Richmond, Virginia, for his role in leading the local bridge burners] and other fiendish women saw him from their windows, and knowing him pointed him out to the soldiers, saying, “There he is; there he goes; that’s Morgan, over there in the vineyard!” The soldiers rode up and began shooting through the grounds. Being closely pressed, and hearing the soldiers’ oaths and threats, the general stood at bay, and feeling assured that they meant to kill him he returned their shots until he had emptied his pistols, and then threw up his hands and surrendered. Captain Wilcox . . . rode up to the general and received his pistols. After a moment’s conversation, Wilcox rode away. While standing there a defenseless prisoner, a soldier approached the general and presented his gun. The general exclaimed: “My God! Don’t shoot! I am a prisoner!” With an oath the cowardly ruffian fired, the ball striking the general full in the breast, passing through the heart and ranging downward. The murderer threw the dead body across his horse and galloped along the streets, exulting in his diabolical deed. He then galloped out to Gillem’s quarters, about two miles from town, and threw the body into a muddy ditch by the roadside.

Different accounts describe how brutally Morgan’s body was abused. Most of these versions come from highly prejudiced Confederate sympathizers. But all sources acknowledge that the Union forces did return Morgan’s body to Mrs. Williams’s home, where it was kept until it could be transported for a proper burial.

The famous Dickson-Williams Mansion, where this incident started, is on the left on the corner of Church and Irish streets, past St. James Episcopal Church. During its lifetime, this house has also served as an inn, a tobacco factory, and a hospital. It has now been restored to its pre–Civil War condition.

Turn left onto Irish Street and travel three blocks to McKee Street. Several historic homes are along this route. Turn left on McKee and go one block to Main Street. On the right at the corner of McKee and Main is the Nathanael Greene Museum, which houses “a record of the life and heritage of Greeneville and Greene County, Tennessee,” according to its brochure.

And house that heritage it does. Inside, you can find the usual farm and domestic implements of local museums, but you can also see some unusual items—Samuel Doak’s Windsor bench, Elbert Kinser’s Congressional Medal of Honor, the bed where John Morgan slept his last night, the slippers Catharine Dickson Williams wore the night she danced with the Marquis de Lafayette, and a ticket to Andrew Johnson’s impeachment. To attend the impeachment proceedings, an invitation and a ticket were required. A different color ticket was used for each day’s session.

Turn left onto Main Street. On the right halfway up the block is Andrew Johnson’s second and last home in Greeneville. He bought the home in 1851, and it served as his Greeneville residence until his death in 1875. The house was desecrated by Confederate sympathizers during the Civil War. Though the state was under Union rule by 1862, Confederates still held parts of pro-Union East Tennessee. Johnson’s property was confiscated and turned into a hospital. His wife, Eliza, escaped to join her husband in Nashville. They did not return until the end of Johnson’s presidential term in 1869. By then, his real-estate holdings had made him the wealthiest citizen in Greeneville.

The two-story white frame house across the street, known as the Sevier-Lowry House, is the oldest home in Greeneville. It was built around 1795. The original part is log, with a stone foundation. The house was expanded and later covered with white clapboards. It was originally the home of Valentine Sevier, nephew of John Sevier. The historical marker in front of the house notes that among its owners were Quincy Marshall O’Keefe and Edith O’Keefe Susong, the only mother and daughter in Tennessee’s Newspaper Hall of Fame.

Continue to the corner of Main and Depot streets. The Greene County Courthouse stands on the right.

The area around the front of the courthouse is crowded with monuments. One commemorates the State of Franklin, since Greeneville served as its seat of government for a time. The monument listing the names of “the role of honor of Greene County” commemorates some of the more interesting characters mentioned in this book, though it may be stretching things a bit to call all of them Greene County natives. You’ll also find a marker about Sergeant Kinser and a monument to Union soldiers. This is particularly ironic, since nearby stands a monument to John Morgan, “the Thunderbolt of the Confederacy.” Another historical marker notes that the Greeneville Union Convention was held here on June 17, 1861. Delegates from every East Tennessee county except Rhea convened here for four days to keep East Tennessee in the Union after the state voted to secede. The marker notes that Tennessee’s reply to these rebels was to occupy the area with troops under the command of Felix Zollicoffer. These monuments attest to the deep divisions this community faced during the War Between the States.

Continue on Main Street. On the right in the middle of the next block is First Presbyterian Church. The walls and columns of this building date to 1848. They survived a disastrous fire in 1928, but the steeple and other parts of the church had to be replaced. The congregation is descended from the original Mount Bethel Church and the Harmony Church group that split off with Hezekiah Balch.

On the right in the middle of the next block of Main Street is a historical marker for the Big Spring. Behind the library is a small park, where the spring is still visible. The Big Spring is the source of Richland Creek and the main reason early pioneers chose this area. Prior to white settlement, this spring was the crossroads for two Indian trails. It served as the major water supply for Greeneville for over 150 years.

Just past the walkway to the spring on the same side of Main Street are Valentine Sevier’s second home, his office, and his servants’ quarters.

Several other historic homes are located in the rest of this block and the next.

On the left in the next block is the Harmony House, built in 1851 by Dr. W. A. Harmon, who taught at Rhea Academy. One interesting bit of history about this house is that soldiers from both sides camped in the backyard at different times in the Civil War. During skirmishes, the neighbors supposedly gathered in the basement of this home for protection. A hole cut in the floor of the living room provided a secret place to store food.

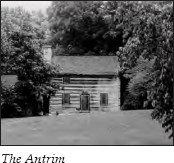

Next to the Harmony House is a structure called the Antrim. In 1793, Thomas Alexander built a one-room log structure near the Nolichucky River. In 1814, he constructed a two-story section for his growing family and joined the two sections with a dogtrot. In 1965, the house was dismantled and reassembled at this location.

Turn around and retrace your route on Main Street to the Nathanael Greene Museum, on the corner of Main and McKee. Just past the museum, South Main Street takes a left turn. The Lutheran church is on the right. Follow South Main up the hill. At the top is the Joseph R. Brown–Milligan House, better known as Boxwood Manor.

This house was begun in 1855. Unfinished at the time of the Civil War, it was given over to the Confederates for their headquarters while in Greeneville. The central hall is dominated by a circular stairway that ascends three floors. The original kitchen came complete with a dumbwaiter, and the dining room still retains its original French wallpaper. But the most distinctive feature, the huge boxwoods, give the home its name. These boxwoods grew from plantings taken from the home of Dr. James F. Broyles on the Nolichucky River. Joseph Ramsey Brown married Dr. Broyles’s daughter Frances Josephine. The original boxwoods were brought over the mountains in oxcarts from Charleston, South Carolina.

Continue on South Main Street past Boxwood Manor. At the intersection with Crescent Street, you will see James Hardin Memorial Park across the street. Turn right onto Crescent, which curves to the right. Then follow the road that veers to the right alongside the stone walls of Andrew Johnson National Cemetery. You will see a back entrance to the cemetery; you can enter here, or you can go to the stop sign and turn right onto Forest Street, which leads to the main entrance on Monument Avenue.

This is the spot President Johnson selected for his last resting place. The Italian-marble monument at the top of the hill marks the graves of Andrew and Eliza Johnson. Erected by their surviving children and dedicated on June 5, 1878, it stands twenty-seven feet tall and features an eagle perched atop a globe. A scroll of the Constitution is above an open Bible; a hand points toward the Constitution. The inscription reads, “His faith in the people never wavered.”

Johnson was the first person buried in this cemetery. He has since been joined by his family and veterans of the Civil War, the Spanish-American War, World Wars I and II, the Korean War, and the Vietnam War.

Leave the cemetery through the main entrance on Monument Avenue. Go one block to West Main Street and turn left. Heading out of Greeneville, West Main turns into U.S. 321. General Alvan Gillem’s troops used the predecessor of this highway on their surprise mission into town to find General John Morgan.

Approximately 2.3 miles after U.S. 321 crosses TN 70 (Asheville Highway), TN 349 turns west, or right, toward Warrensburg. The highway is also called Warrensburg Road. Turn right onto this highway.

After approximately 3 miles, Dulaney Road turns off to the right; Dulaney Store, on the left, was established in 1892. Continue on Warrensburg Road, which now travels through rolling farmland, with the mountains off in the distance.

After 8.9 miles, you will come to the Bible Bridge, a covered bridge located adjacent to the present-day road. In 1820, this route, known as the Warrensburg Turnpike, was one of the main thoroughfares in the area. It served the Warrensburg community, which boasted some of the most fertile land in East Tennessee and had a thriving corn and hog economy.

Christian Bible and his family settled here in 1783. They built a log house nearby around 1800. The bridge was constructed in 1923. At one time, perhaps thirty or forty similar bridges crossed Little Chucky and Lick creeks. The Nolichucky River probably had at least ten covered bridges across it in this area, but they were all washed away in the flood of 1900.

You can tell this area has been prosperous farming country for generations by some of the dates of the farms and cemeteries—Hillsdale Farm, on the left 0.8 mile up the road, was established in 1830, while Gum Spring Cemetery, 0.3 mile farther on the left, was founded circa 1836.

It is 1.6 miles from the Bible Bridge to the junction with TN 340. Turn right onto TN 340, heading north. On the left is a wide valley between the road and the Nolichucky River. The road follows this valley.

It is 1.5 miles to the community of Warrensburg. The drive through the countryside is very scenic, thanks to the well-kept farms and the interesting assortment of barns along the way. It is 7.7 miles from Warrensburg to an intersection with I-81. Continue on TN 340. It is 2.8 miles to the deserted Morristown Fish Hatchery, on the left; you can see the drained ponds. Just 0.7 mile past the hatchery is an intersection with TN 113. Turn right onto TN 113, or Silver City Road. It is 1.8 miles to the community of Silver City, then 1.2 miles farther on Silver City Road to Warrensburg Road. Turn left on Warrensburg Road.

After 2.9 miles on Warrensburg Road, you will see railroad tracks ahead. Little is visible from the highway, but Hayslope, one of the area’s most famous residences, lies behind the trees on the left.

Colonel James Roddye was awarded this tract of land for his service in the Battle of Kings Mountain during the Revolutionary War. Tradition says he discovered a large spring that empties into Fall Creek at the foot of the hill by watching an Indian woman coming and going through the underbrush. The nearby town of Russellville was named in honor of Roddye’s wife, the former Elizabeth Russell.

Roddye built the first home in the area around 1785. This house, known as the Red Door Tavern, became a well-known inn along the highway. It was later sold to Hugh Graham, who gave it as a wedding present to his daughter, Mrs. Louise Rogan. It was Mrs. Rogan who named the estate Hayslope. Some accounts say she was permitted to keep her cows during Lieutenant General James Longstreet’s occupation of the town as long as she supplied the officers with three gallons of milk daily for their eggnog.

Continue straight on Warrensburg Road past the picturesque Russellville Church of God to the intersection with U.S. 11E. Across the street is a two-story white frame house. In its front yard is a historical marker. A short distance down the highway to your left stands a white stone marker with a bronze plaque. The stone marker indicates the site where the Confederate Army of Tennessee camped during the winter of 1863–64. General Longstreet billeted in the white frame house that winter, while Major General Lafayette McLaws stayed at Hayslope. During that time, Longstreet tried to secure East Tennessee for the Confederacy.

Continue straight across U.S. 11E; you are now on Depot Street. After one block, turn right. It is a few yards to a left turn onto Three Springs Road, then 0.5 mile to a sign marking the former site of Cain’s Mill. The loss of this mill to fire in 1971 was a blow to area residents. Old photographs show that the mill, built in 1838, had a beautifully preserved twenty-four-inch waterwheel. During Longstreet’s occupation, the mill ran day and night, grinding corn for the troops. New parts were brought from France in 1880 and installed to grind wheat flour. This area is still well maintained, although little remains of the former mill.

After passing the sign about the old mill, travel 1.6 miles to Cains Mill Road and turn right. If you were to go left, you would eventually wind through backroads to Cherokee Lake, built and controlled by the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA).

In 1940, the United States was already making national defense plans. One vital product needed in defense was aluminum. The American Aluminum Company’s plant at Alcoa was a major source of that metal. The Alcoa plant used tremendous amounts of electricity, so one of the first proposals submitted to the Defense Advisory Commission by the TVA was a plan to build Cherokee Dam on the Holston River. A special appropriations bill passed in July 1940. The dam was closed on December 5, 1941, two days before Pearl Harbor. Almost thirteen thousand acres of land were acquired for the project, eighty-five hundred of them below maximum water level. (For more information about the TVA, see The Norris to Cumberland Gap to Oak Ridge Tour, pages 166–69.)

It is 1.5 miles on Cains Mill Road back to the intersection just above the site of the old mill. Turn left and retrace your route to Dobson Ferry Road. Turn left. It is 0.6 mile to an intersection where Old Russellville Pike goes off to the right. U.S. 11E curves left, so you may not realize Old Russellville Pike is cutting off to the right. Turn left onto U.S. 11E, then immediately turn right onto Old Stagecoach Road.

You will see another historical sign like the one for Cain’s Mill. This one describes the Coffman House, visible on the right just ahead of the sign. David Coffman came to this area much like James Roddye did—with a land grant for Revolutionary War service. His son, Andrew Coffman, became a well-known Baptist preacher. Andrew was born in the original log cabin on this site in 1784. That cabin and its additions, later covered with clapboards, still stand.

Continue on Old Stagecoach Road for another 2 miles. As the name implies, this route follows the Great Stage Road, an important artery between Washington, D.C., and the western frontier. Old Stagecoach Road went from Abingdon, Virginia, to White’s Fort (now Knoxville). It followed an ancient Indian trail that served as a tributary of the Great Indian War Path.

At the stop sign, you will see a sign for Bent Creek Cemetery, on the right. The cemetery may be worth a side trip.

Bent Creek Church was founded in 1785. The first pastor was Tidence Lane, who remained the church’s minister until his death in 1806 at the age of eighty-one. The first services were held under a large tree near the site of the present-day cemetery. A log church was soon constructed. The congregation used it until 1878, when a brick building was erected in nearby Whitesburg; that newer church is now the Kyle Masonic Lodge. After the new church was constructed, the log building was moved to the Coffman Farm, where it was used as a barn. At one point, an attempt was made to restore the historic structure, which some say was the second Baptist church in Tennessee. The logs were moved to Whitesburg, but funds never materialized for restoration, and the wood eventually rotted.

An early member of the church was William Horner, who donated an acre of land in 1810 to be used as a community burial ground. One of the first people interred here was an unknown traveler on what was then the Indian trail who died at Horner’s house. Local citizens donated a stone monument for his grave on the 150th anniversary of Bent Creek Church.

If you don’t take the cemetery side trip, turn left, still following Old Stagecoach Road; you will have to make a quick right turn to continue on Old Stagecoach Road. After 3.3 miles, you will cross the Hawkins County line and enter Bulls Gap. Continue straight into Bulls Gap.

Despite the tendency to attribute quaint meanings to the town’s name, Bulls Gap was actually named for John Bull, a local gunmaker whose rifles were much sought-after by expert marksmen on the Tennessee frontier. Each rifle was marked with the maker’s name, the name of the person for whom it was made, and the date of completion. Bull migrated from Pennsylvania and settled in this natural gap in Bays Mountain about 1794.

Later, the area became strategically important because of the East Tennessee and Virginia Railroad, which was completed through the gap in 1858. During the Civil War, it was the scene of several heavy skirmishes, as each side fought to control the railroad through the mountains. The Southern Railroad still exerts a strong influence on the community.

Today, the birthplace of one of Bulls Gap’s favorite sons may be the area’s leading attraction. Country-and-western star Archie Campbell was a member of the Grand Ole Opry from 1958 until his death in 1987. He was probably best known for his role on the television show Hee Haw. His home has been reconstructed in the town’s park, located in the middle of the community on South Main Street.

Continue on South Main to the stoplight at the intersection with U.S. 11E.

This ends the tour. A few miles to the right is I-81. If you continue straight across U.S. 11E onto TN 66, you will be headed toward Rogersville. If you turn left onto U.S. 11E, you will be headed toward Morristown.