The Norris to Cumberland Gap to Oak Ridge Tour

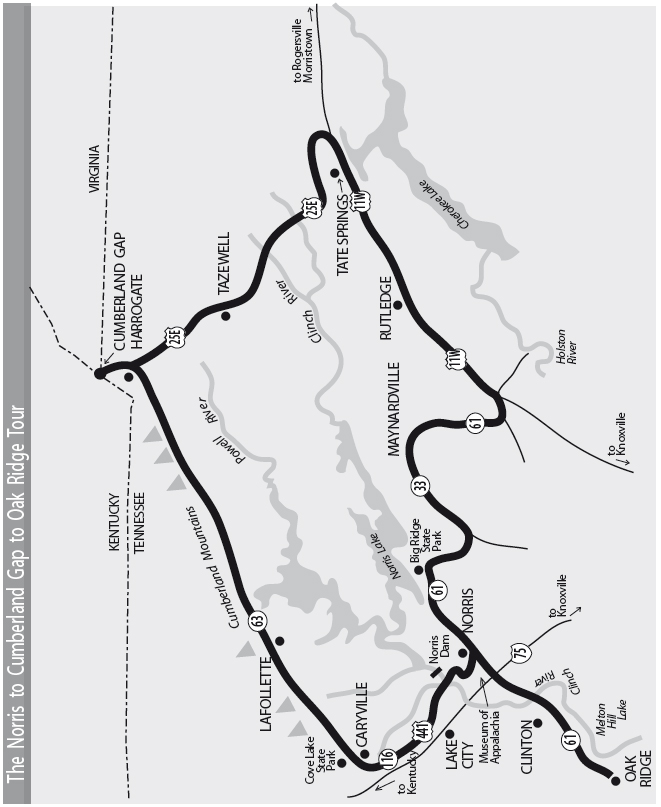

This tour begins at the Museum of Appalachia and continues to the town of Norris, Norris Dam, Norris Dam State Park, and Lake City. It then goes to Caryville, LaFollette, Powell Valley, Harrogate, and the Cumberland Gap. After touring the Cumberland Gap National Historical Park, the tour travels to Tazewell, Bean Station, Tate Springs, Rutledge, Big Ridge State Park, Clinton, and Oak Ridge.

Total mileage: approximately 190 miles.

This tour begins at the Museum of Appalachia, located 1 mile from Exit 122 off I-75; the museum is 16 miles north of Knoxville on TN 61 near the town of Norris. The museum complex, located on your left, is hard to miss.

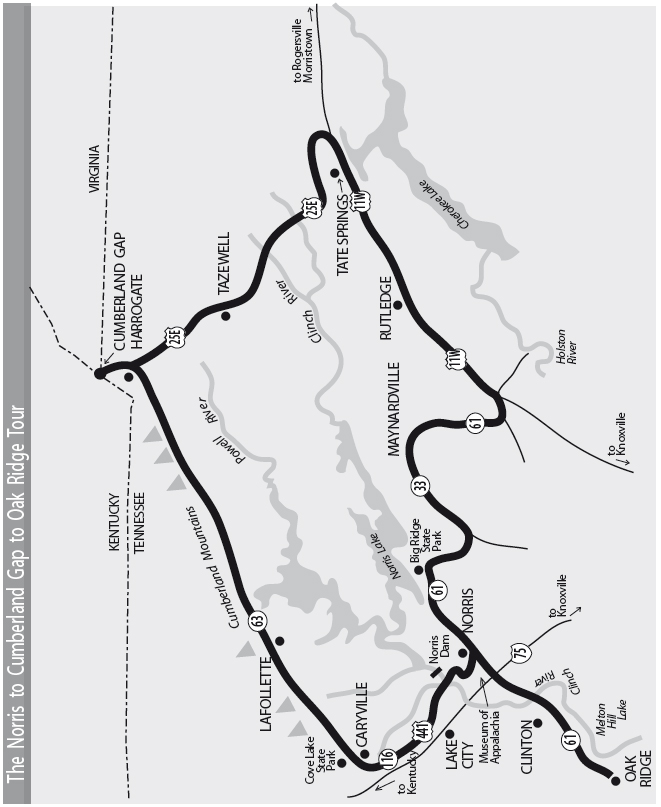

On the sixty-three-acre farm are over thirty buildings that house more than 250,000 objects. The buildings are set up so visitors can capture the feel of what Appalachian life was like in an earlier era. The creator of this museum of Appalachian life and customs was John Rice Irwin. As word spread about Irwin’s collection, some of the mountain people he had come to know acted as “lookouts,” telling him about unusual items that might add to his collection.

Among the buildings is a log house that was moved from the adjoining county. The daughter of the first occupant was born in this house, raised her nine children here, and died here at age eighty-seven. It is a real house, not just a replica.

Every outbuilding on this typical Appalachian homestead has a similar story. The farm includes a chicken house, an underground dairy, a smokehouse, a corncrib, a hog lot, a sheep pen, a loom house, and even a privy. And Appalachian life would not have been complete without a blacksmith shop, a millhouse, a wheelwright shop, a church, and a schoolhouse. You can visit a ten-thousand-square-foot building that houses all sorts of frontier and pioneer memorabilia, along with a three-story structure devoted to relics belonging to notable, historic, famous, and colorful people from the region.

But don’t think these exhibits are commonplace. At one, you may at first glance see just a collection of thousands of traps, but when you look more closely, you’ll find among them a mousetrap that dumps one victim after another into a glass jar while it resets itself, as well as Enoch Williams’s trap that drops a rock on the head of the creature that pulls the bait.

This is not just a museum of inanimate objects either. Various animals are kept on the farm, including a herd of “fainting goats,” which have a tendency to faint when frightened. In the spring, crops are planted. At other times, some type of real-life demonstration is usually taking place somewhere on the property.

The Hall of Fame, located in a separate house in the complex, offers an interesting collection of memorabilia. One section is devoted to Sergeant Alvin York. To give you an idea of how esoteric these exhibits are, Irwin’s handwritten notes accompanying the exhibit relate a story told by York’s youngest son. One of the demands York made before agreeing to sell the movie rights to his life story was that the actor who played him had to be a good, honest, and totally temperate person. Once, while visiting the set, York saw Gary Cooper, the actor playing him, smoking a cigarette. York demanded that all filming stop until Cooper was replaced. After receiving a written apology from Cooper, York agreed to let the filming continue. In this exhibit, you can see Cooper’s note scribbled on a promotional photo of the actor portraying Sergeant York. (For more information about Alvin York, see The Rugby tour, pages 212–14.)

An admission fee is charged for the museum, but it is well worth it. The one drawback is that it is impossible to see everything in one visit. Make sure you allot a good block of time to tour the exhibits.

After visiting the museum, return to TN 61, turn left, and continue toward Norris. Just past the turnoff for U.S. 441, you will see signs directing you to the town.

The history of the Tennessee Valley Authority is closely tied to Norris, since the town was built specifically to house workers on the first dam constructed by the TVA.

From 1898 until the passage of the TVA Act in 1933, some form of legislation during every session of Congress advocated the damming of the Tennessee River. In 1913, Hales Bar Dam was built 33 miles below Chattanooga by the Tennessee Electric Power Company under the supervision of army engineers. When World War I broke out, the nation’s vulnerability in the production of nitrates—used in the manufacture of explosives—was soon evident. America’s primary source of nitrates was Chile. The National Defense Act of 1916 gave the president authority to ascertain the best way to produce synthetic nitrates and to construct dams, plants, and other facilities necessary in the manufacturing process. After the war, these facilities were to concentrate on the manufacture of fertilizer, which also uses nitrates.

At that time, one of the basic ways to manufacture synthetic nitrates was through the cyanamid process, which required large amounts of cheap hydroelectric power. But the war was over before the projected dams were begun. Only two plants, one using the cyanamid process and the other an experimental process, had been built by the end of the war.

In March 1921, the secretary of war invited the public to make offers on the plant properties. Henry Ford, the automobile magnate, came forward and offered five million dollars for the nitrate plants, the steam-power facilities, and other miscellaneous property.

To this day, no one knows exactly what Ford planned to do with these facilities. He and Thomas Edison made an exploratory trip to Muscle Shoals, Alabama, to look over property there in December 1921. At Florence, Alabama, Ford gave a speech announcing that he would use the Muscle Shoals project to demonstrate a new method of financing, which he called “the energy dollar.” He declared that his new financial system would eliminate the one cause of war—gold. It was Ford’s theory that international bankers on Wall Street created wars from time to time in order to raise interest rates. He went on to elaborate that these bankers controlled enough of the world’s gold supply to have enormous power over economic and political life. Ford proposed that, to finance his project, the federal government would issue paper money based on the potential wealth of Muscle Shoals. This method would be so successful that the government would “never again need to borrow interest-bearing bonds for internal improvements but instead it would merely issue currency against its imperishable national resources.”

The next day, Ford went a step farther when he linked the Wall Street conspiracy with international Jewry. Ford’s anti-Semitism created quite a furor in the press. National publicity focused on the issue.

As Donald Davidson describes events in his excellent history of the Tennessee River, The Tennessee: The New River, private power companies that had been waiting for government property to be dumped “like worthless carrion, were compelled to end their watchful waiting. They flapped down from on high and made their own offers.” When his offer passed the House but failed in the Senate, Ford withdrew his bid.

The rejection was largely the work of Senator George W. Norris of Nebraska, a progressive Republican who was chairman of the Senate Committee on Agriculture and Forestry. His committee’s report charged Ford with pettiness and shrewd calculation in the terms of his bid. Norris also argued that Muscle Shoals should remain in government hands, if only for its value in time of war. He argued, “It would be as reasonable to put our battleships up for sale . . . or to dispose at scrap value of the guns and munitions in our forts and arsenals.”

The fertilizer issue, which had lurked as the peacetime rationale for the nitrate-producing facilities, began to take a backseat to the idea of producing electric power. Norris maintained that a government-controlled utility company could act as a yardstick to measure what private companies should charge for power.

Then flood control entered the picture with the massive Mississippi floods of the 1920s. In 1928, Norris presented an ambitious proposal that included plans for the erection of a large storage dam at Cove Creek on the Clinch River. The dam would equalize the flow of water in the Tennessee River, thus assisting in flood control. The House added provisions for the operation of both power and fertilizer facilities by a government corporation.

The measure passed, but President Calvin Coolidge gave it a pocket veto. In 1931, Norris tried again; this time, President Herbert Hoover vetoed it. But when Franklin Roosevelt and his New Deal arrived on the scene, the project was given priority. In May 1933, the act authorizing the Tennessee Valley Authority was created.

This was an experiment people probably would have fought against, if they had known what a “government corporation” would turn into. The TVA was entirely free of state and local control. The three directors of the authority made the rules, but the people affected by those rules could not elect the directors.

One of the first acts of the TVA board was to change the name of the Cove Creek Project to the Norris Project to honor the man who was called “the Father of TVA.” Construction of the dam began in October 1933. The gates were closed on March 4, 1935, and the water began to rise in the Norris Reservoir, which eventually covered thirty-four thousand acres. To gain control of this land, over three thousand families had to be evicted.

By June 1946, the TVA had erected what were called “high dams” in sixteen areas. It had purchased over a million acres of land and moved over thirteen thousand families. About two-thirds of that number were not landowners but tenant farmers. Landowners were made an offer based on estimates by field appraisers. No bargaining was allowed; the owner could take or leave the offer made by the TVA. Landowners could appeal through the courts, but they were usually unsuccessful. As Donald Davidson puts it, “The rising waters gave TVA an argument that General Winfield Scott did not have in 1838 [when he removed the Cherokee Nation to Oklahoma]. One may take arms against a sea of troubles, no doubt, but one cannot take down a rifle to fight an actual, practical flood. When TVA surveyors came through the valley and put bold marks on trees and barns to show where the water would come, the argument was really over.”

The TVA worked with landowners to help them find new farms, but these were usually on property that was more depleted and less desirable than the river-bottom land they were leaving. The tenant farmers were left to their own devices. As the TVA’s general solicitor put it, the TVA could not risk “being turned into a relief and charitable agency.”

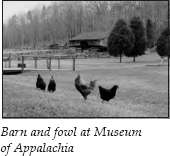

But progress was on the way. The construction of Norris Dam was to employ twenty-eight hundred men. The dam was to be a third of a mile long and 265 feet high and contain a million cubic yards of concrete.

The question now arose as to where the workers building the dam would be housed. Large-scale, short-term public-works projects usually housed workers in temporary construction camps that were later destroyed. But TVA chairman Arthur Morgan proposed building a permanent “model” community.

A site for the town was selected in July 1933. Construction began in January 1934, and the first dwellings were ready for occupancy in May. By that October, the town of Norris had 150 houses and eight campus-like dormitories, which architect Frank Lloyd Wright claimed were “more pleasant than most summer resorts.”

The town plan followed the garden-city movement started in England in the 1890s. The roads curved to match the contours of the terrain. Large parcels of land were preserved as parks, and a rural greenbelt circled the town. Houses were not uniformly situated on their eighth-of-an-acre lots; many were grouped in semicircles around small, green commons. A large commons was located opposite the school, which also served as a community center. Sidewalks did not run next to the streets; they were actually pedestrian paths.

Not just the city but also the houses were an example of experimental planning. Twelve different architectural designs were employed for the houses, and different materials were used so they wouldn’t look uniform. Two-thirds of the houses were all-electric—after all, the TVA was promoting electric power. TVA news releases from this early period are amusing, as they show women demonstrating their washing machines, their electric ranges, and their refrigerators with two ice-cube trays.

The experiment carried over into the lives of the workers. TVA chairman Morgan wanted the construction workers to leave their short-term jobs with some skills. He developed a program that required them to spend only thirty-three hours a week on the job. During off-hours, they were encouraged to take classes in woodworking, plumbing, welding, electricity, writing, or printing.

The community concept even extended to group worship. The Norris Religious Fellowship was a community church that was part of no specific denomination. Its creed was “In things agreed upon Unity, in other things Liberty, in all things the will to be One.”

The residents of Norris knew the massive project would eventually come to an end, but World War II delayed any plans to sell the town. In June 1947, however, the TVA declared Norris “surplus property” and launched what it called the Norris Disposal Project. The TVA announced that it would sell the town within a year.

The town’s fourteen hundred residents now had to face a complete reorganization. The TVA announced that it would take no less than $1.8 million and would sell Norris as one collective unit. A group of residents formed a corporation to purchase their community, but they were quickly outbid in June 1948. Henry Epstein, representing a group of Philadelphia businessmen, won the bidding at $2.1 million. He bought 1,284 acres, 341 dwellings, a small business district, a school, and several other structures. Under the terms of the sale, residents were entitled to retain their leases for one year. Epstein then gave them the opportunity to purchase their homes. Within a year, all the houses were sold. In 1953, a citizen-owned company purchased the nonresidential property from Epstein’s syndicate, and the transfer of property was complete.

The town of Norris is still an impressive argument for city planning. Don’t be misled when you turn off TN 61. You are traveling on East Norris Road, and you are entering a town. No commercial strip of fast-food franchises is anywhere in sight. In fact, the whole community looks like an upper-middle-class neighborhood.

Shortly, you will find yourself at the commons area. Here, you can see the original school and the Norris Religious Fellowship building. The fellowship remains active. The town’s small commercial area offers essentials like a service station, a town hall, and a fire department, all housed in buildings that blend with the surroundings.

Continue past the commons on West Norris Road, which winds along the ridge through more neighborhoods. You will pass several churches established when the community made its transition to private ownership. West Norris Road intersects U.S. 441, also known as the Norris Freeway. Once again, TVA planning played a role in creating a model. This is how Davidson describes the road: “On either side, as the road wound among the ridges, the motorist could see, or begin to see, neatly fostered illustrations of the forest conservation and proper land use which the authority was committed to sponsor. The nearer he came to Norris Dam, the more the countryside took on the appearance of an amiable wild park which told him, without words, how Tennessee ought to look if it were benevolently protected from man’s foolishness.”

This 21-mile-long “freeway” runs across the top of the dam and connects two important highways—U.S. 25W and TN 33. The concept of having a twenty-five-foot right of way that prohibited roadside stands, service stations, and billboards was considered revolutionary when this road was constructed in 1934.

Turn right onto the freeway, heading toward Norris Dam. Before you reach Norris Dam, you will see a low-water dam on the left. This dam was built to improve trout fishing downstream. The TVA sometimes shuts off the flow from the big dam for hours at a time. The riverbed used to get so dry that aquatic insects died. With their food supply gone, the trout disappeared as well. This low dam—called a weir dam—provides a constant supply of water and keeps both the trout and the trout fishermen happy.

On the right just past the low dam, you will see signs for the Lenoir Museum. It’s purely coincidental that Will G. Lenoir’s collection of memorabilia is housed in a museum so close to the similar Museum of Appalachia. Unlike John Rice Irwin’s collection, this museum houses items that are not exclusively Appalachian in nature. The highlight of this free museum is a rare barrel organ with forty-four movable figures. When the organ is wound, it plays ten tunes while the figures dance, gallop, and work.

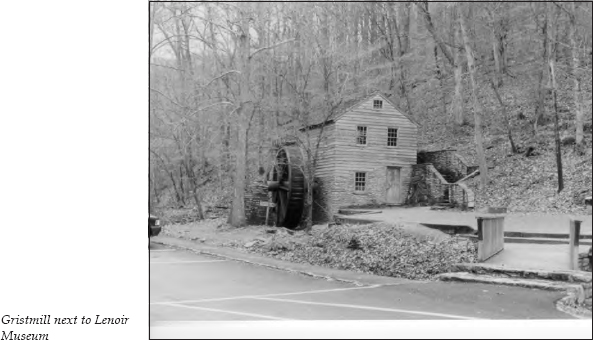

Next door to the building that houses the collection are an eighteenth-century gristmill and a threshing barn built in the early nineteenth century. Ironically, John Rice Irwin’s ancestors once operated the gristmill.

After touring the Lenoir Museum, continue toward the dam. You can take the left fork and drive to the bottom of the impressive structure, or you can continue on the main road, which runs across the top of the dam. Norris Dam State Park and Norris Dam Municipal Park control this area. To the right is a loop that leads to some of the rustic cabins available for rent from the state park.

Drive across the top of the dam and continue past a section of cabins for 3 miles to Lake City. Lake City used to be called Coal Creek. The older name was appropriate, because this area was dominated for several decades by the mining of coal.

In 1853, Coal Creek had only one log house. But after the Civil War, railroads made shipping the area’s coal a practical endeavor. In October 1867, the first car of coal was shipped from Coal Creek. By 1905, six hundred thousand tons were shipped from Anderson County. As many as seven major coal companies and ten to twenty smaller companies operated in the Coal Creek Valley. In 1905, approximately fourteen hundred miners worked in the valley.

But 1905 was the high-water mark for coal production in Anderson County. New coal fields in Kentucky and West Virginia opened. By 1919, only eight hundred men still worked in the area’s mines. But during those peak years, coal mining dominated the region and created the environment that made Coal Creek famous nationwide.

Shortly after the Civil War, Tennessee, like most bankrupt southern states, needed to come up with a plan to cover the cost of prison upkeep. In 1865, the state passed an act “to lease out the penitentiary.” Initially, only a few convicts were leased to work in the mines, but it quickly became evident to mine owners that convicts were far cheaper than the labor they had been hiring.

As more miners were displaced by convict labor, tempers rose. The miners were already frustrated that they were usually paid in scrip, which was redeemable only at the company store, where prices were generally considerably higher than elsewhere. The miners were paid according to the amount of coal they brought out. In early 1891, they asked for a check-weighman to be hired from their ranks, who would give them a fair accounting of how much coal they mined each day. That spring, the miners balked at accepting the operator’s new contract, so the Tennessee Mine at Briceville brought in forty convicts to replace the dissatisfied workers. One of the convicts’ first jobs was to tear down the company-owned houses where former miners lived and replace them with a stockade to house even more convicts.

On July 15, the miners took things into their own hands. Over three hundred of them marched to the stockade and ordered the guards to release their prisoners. The miners then escorted the convicts and their guards to Coal Creek, where the miners put them all on a train back to Knoxville. The Coal Creek War had begun.

On July 16, Governor John “Buck” Buchanan showed up with three companies of Tennessee militia to install and protect the convicts. Buchanan debated union organizer Eugene Merrell, but the workers already knew what they thought. On July 20, more miners arrived from all over East Tennessee. A crowd of over two thousand marched to the Briceville stockade. Once again, the convicts were put on the train to Knoxville. The miners then marched to another mine at Coal Creek and sent those convicts away as well.

On July 24, the state legislature made it a crime to lead a protest group or interfere with the work of a convict. The miners were not impressed. On October 31, fifteen hundred men marched on the stockades at Briceville and Coal Creek, burning the one at Briceville. This time, the miners supplied the convicts with food and clothing and told them to get lost. Some of these convicts were never recaptured. Rewards were offered to anyone who would bring in the leaders of the miners. But the miners stuck together.

In January 1892, the militia returned. By this time, twenty-six newspapers were sending “war correspondents” to cover the insurrection. Several European newspapers carried accounts of the “East Tennessee War.” Amazingly, no bloodshed had yet occurred.

The militia now dug two lines of trenches in the valley and fortified the stockade called Fort Anderson with Gatling guns. The fighting escalated, and people started getting shot. That August, five hundred soldiers were sent into the valley. They arrested three hundred miners in ten days. Most miners were eventually forced to sign a disclaimer of any involvement in the release of the convicts. The convicts returned to work in the mines until 1896, but the lease system was not renewed after that. Governor Buchanan’s handling of the situation cost him reelection in 1892.

One more incident followed in April 1893 at Tracy City, but the miners were unsuccessful in their attack on the stockade. This ended the Coal Creek War, but not coal mining in the area.

On Monday, May 19, 1902, at seven-thirty in the morning, an explosion occurred in the Fraterville Mine near Coal Creek. It proved to be one of the most disastrous mine explosions in America. Of the 184 men and boys who went into the mine that morning, none came out alive. Some were killed instantly, but others found air pockets and lived long enough to write heartrending farewell letters to their loved ones. One letter read, “Dear Ellen, I have to leave you in a bad condition. But dear wife set your trust in the Lord to help you raise my little children. . . . There is but a few of us left here and I don’t know where the other men is.” Another read, “We are all praying for air to support us but it is getting so bad without any air. Horace, Elbert said for you to wear his shoes and clothing.”

After the disaster, only three adult men were left alive in the small mining community of Fraterville. Criminal indictments were returned by the grand jury against the Coal Creek Coal Company for failing to provide proper ventilation, but no final judgments were ever handed down. Most of the widows settled out of court for approximately three hundred dollars for each certified death.

Follow U.S. 441 under the I-75 overpass to the stoplight at the junction with U.S. 25W/TN 116 in Lake City. Turn left, following U.S. 25W (Main Street) south through town. It is 2.4 miles to Big John’s Foodette, on the left. Turn left, following the signs to Clear Branch Baptist Church.

It is 0.4 mile up the hill to the church. Leach Cemetery is located behind the church. At the far end of the cemetery, you will see a large shaft marking a circle of graves where eighty-seven miners were buried after the Fraterville disaster. On the monument is a list of all the miners who are buried here in what is known as Miner’s Circle.

Retrace your route into Lake City. At the junction with U.S. 441, continue straight on TN 116, heading north to Caryville. TN 116 parallels I-75 for the 5.1 miles to Caryville. At the intersection with U.S. 25W/TN 63, turn right. It is 0.5 mile to Cove Lake State Park, on the left.

After Norris Dam was built, water backed up into the hollows around Caryville. When the water level was lowered at Norris Dam during the winter months, the bare, exposed land became an eyesore. In 1938, a new dam was built at Caryville. Since this dam was higher than Norris Dam, it formed a year-round beauty spot, which was called Cove Lake.

From Cove Lake State Park, you can hike an 11-mile segment of the Cumberland Trail. The Cumberland Trail, a state scenic hiking trail, became Tennessee’s fifty-third state park in 1998. When Justin P. Wilson Cumberland Trail State Park is completed, it will contain a corridor of 300-plus miles that will begin at Cumberland Gap National Historic Park and continue to Chickamauga and Chattanooga National Military Park and Prentice Cooper State Forest outside Chattanooga. Forty-seven miles of trail will connect the Cumberland Gap starting point to Cove Lake State Park. The Eagle Bluff section of the trail is open from the Tank Springs trailhead to Cove Lake State Park. You can pick up the trailhead at the state park. This section takes hikers to breathtaking views at Devil’s Racetrack. But be forewarned—the descent of the main trail off the crest is so steep that it has earned the nickname “Suck Air.”

After leaving Cove Lake State Park, follow U.S. 25W/TN 63 for 3.1 miles to LaFollette. You will notice that this town employs a sensible system of numbering its stoplights. At stoplight #8, U.S. 25W turns north. Continue straight on TN 63.

For the next 34 miles, you will travel through Powell Valley as the Cumberland Mountains loom on the left. When this segment of the Cumberland Trail is opened, you will be able to hike the ridge along these mountains.

TN 63 intersects U.S. 25E on the outskirts of Harrogate. Turn left onto U.S. 25E, heading north toward the Cumberland Gap. Harrogate was founded in 1888 by Alexander Alan Arthur. (For information about Arthur’s activities in Tennessee, see The Newport Tour, pages 231–32.)

After the collapse of his Scottish Carolina Timber and Land Company in Newport, Arthur came to the Cumberland Gap to check out the possibility of building a railroad from Morristown into Kentucky so he could exploit the coal resources across the border. He gained the support of a group of wealthy young men in New York and Baltimore and formed the Gap Associates. Next, Arthur ventured to England and rounded up more investment. He then formed the American Association, Ltd.

The biggest hurdle in building the railroad was getting through the Cumberland Mountains. Arthur’s company built the town of Cumberland Gap, Tennessee, to house workers while they dug a tunnel through the mountain. They dug from both ends for eighteen months until they finally completed the tunnel on August 8, 1889.

On the Kentucky side of the mountain, Arthur laid out his model city and named it Middlesboro. Always hustling, he also convinced investors that a resort community would thrive if the health benefits of the area’s mineral water were touted. In 1892, his company built a seven-hundred-room hotel named Four Seasons, along with a sanatorium; this resort community was located in what is now Harrogate.

Three years after it was built, the hotel was torn down. The Reverend A. A. Myers wanted the land where the hotel stood for his Harrow School, which he had founded for the education of local mountain children.

Myers, a Congregational minister, had come to Cumberland Gap with his wife in 1888. In two years, they opened a school in their church’s basement. Two years later, they moved the school into the vacated Cumberland Gap Hotel. They charged one dollar a month for tuition. Some 255 mountain children were soon enrolled in Harrow Academy.

In June 1895, Myers heard that General Oliver Otis Howard was coming to East Tennessee on a lecture tour. Myers invited Howard to address Harrow Academy’s graduating class. At dinner following the address, Myers approached Howard about the school’s need for funds. Howard recalled a time in September 1863 when he and President Abraham Lincoln were in a planning session about military strategy for the Cumberland Gap. At that time, Lincoln had expressed his desire to help the people of the area. For that reason, Howard suggested that Myers make his school a living memorial to Lincoln, and Lincoln Memorial University was born. The school’s charter states that the university “shall ever seek to make education possible to the children of the humble, common people of America, among whom Abraham Lincoln was born, and whom he said God must love because he made so many of them.”

The university was chartered in 1897 on February 12—Lincoln’s birthday. Its first major building was the old sanatorium constructed by Arthur’s investors.

At a 1901 celebration of Lincoln’s birthday held at Carnegie Hall in New York, Howard explained the purpose of Lincoln Memorial University. This event was reported in the New York Times, and contributions to the school flowed in.

As you enter the town of Harrogate, you will see the campus of Lincoln Memorial University on the left. The Abraham Lincoln Museum, located on the campus, houses one of America’s most complete collections on Lincoln and the Civil War. Among the items on display is the ebony cane Lincoln carried on the night he was assassinated.

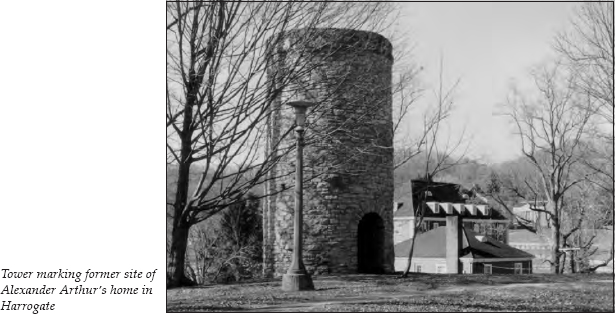

Although the old sanatorium burned, Grant-Lee Hall, as it was named, was rebuilt using the original stonework on the bottom half of the building. Arthur’s home also burned. Its former location is marked by a stone tower visible on your left when you enter the campus.

Continue on U.S. 25E to the exit for TN 58 East, following the signs to Cumberland Gap, Tennessee. You will descend the mountain to this quaint village of only a few blocks. Nestled in the shadow of the mountain, the town has retained many of its historic buildings and turned them into bed-and-breakfast inns. Now that the busy highway passes above the town, it has become even more enticing for those seeking out-of-the-way places.

Turn right onto Colwyn Avenue and continue to the town hall, where you can obtain tourist information. Turn left onto Pennlyn Avenue. A historical marker here indicates the original site of the Reverend Myers’s Harrow School.

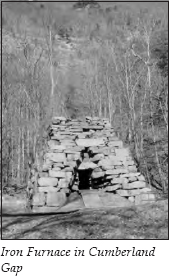

Continue two blocks to the Iron Furnace, on the right. This furnace began operation in the early 1820s. It required two hundred bushels of charcoal, five hundred pounds of limestone, and two tons of ore to make one ton of iron. The furnace produced six tons of pig iron a day. Most of it was shipped to Chattanooga or sold to local blacksmiths. By 1880, cheaper methods of manufacture and the availability of steel made this type of iron smelting uneconomical.

The first white man to see this area was Gabriel Arthur. (For more information about Arthur and his journey into Indian country, see The Overhill Towns Tour, pages 309–10.) When Arthur was released by his Shawnee captors in 1674, he was shown a trail that led through Ken-ta-ke (now the state of Kentucky), through the Great Gap, and on to Chota. The Cherokees called this trail Athawominee, or “Path of the Armed Ones.” The white settlers called it the Warriors’ Path. It was the western half of a well-traveled trading path and warpath used by various tribes as they moved from Ohio through Kentucky into Tennessee. The eastern half of the path, called the Great Indian Warpath, connected the Iroquois Confederacy in the north with the Cherokees and Creeks in the south.

Although Gabriel Arthur brought news of this route when he returned to Fort Henry, Virginia, the path was not used by white men.

In April 1750, Dr. Thomas Walker, a member of a well-established Virginia family, led a party exploring the large land grant Colonel James Patton had secured in 1745. Walker was firmly convinced that should the English prevail over the French for control of the western lands, there would be great opportunities to amass considerable estates. He was one of the primary promoters of the white settlers’ westward movement.

On his journey, Walker kept a journal that provides insight into the country at that time. On April 13, his party reached the Cumberland Gap. Walker reported that the “Gap may be seen at a considerable distance, and there is no other that I know of, except one about two miles to the North of it, which does not appear to be so low.” He also mentioned that “on the North side of the Gap is a large Spring, which falls very fast, and just above the Spring is a small Entrance to a large Cave, which the Spring runs through. . . . On the South Side is a plain Indian Road.”

Although historians agree that Walker gave the name Cumberland to the gap and the nearby mountains, they disagree on when he did this. In Early Travels in Tennessee Country, Samuel Cole Williams says Walker named the gap ten years after his first visit, when he made a second journey to the area.

Regardless of the date, Walker named the gap after the duke of Cumberland, the son of the reigning English monarch. The duke had established a reputation for brutality when he refused quarter to the wounded Scottish Highlanders fighting for Bonnie Prince Charlie at the Battle of Flanders. Some of the early settlers of Scottish ancestry remembered the duke’s role all too well and refused to call the mountains and gap by his name. One settler, Colonel Arthur Campbell, insisted on writing the Indian name Ouasioto on all his maps and correspondence.

But white settlement was still in the future. After Richard Henderson completed his Transylvania Purchase in 1775, he engaged Daniel Boone to blaze a trail to the Kentucky River. On March 10, 1775, Boone and about thirty axmen left the Long Island of the Holston to cut a trail to the newly acquired land.

Earlier, an explorer named John Finley had told Boone about a gap through the mountains to the rich land beyond. In 1767-68, Boone had convinced Richard Henderson to subsidize a hunting expedition into this little-explored area in exchange for information about choice sites for settlements.

Boone missed the gap on that expedition, but he met Finley again when he returned to North Carolina. The two were members of a group that went out the next spring. They easily found the gap and hunted the area. That December, Boone and Finley were captured by Shawnees. After their escape, Finley and the other members of the party left Boone and his brother-in-law, John Stuart, in the wilderness by themselves. Daniel’s brother, Squire, arrived with fresh supplies but soon returned eastward with the furs the hunters had accumulated. Then Stuart disappeared, which left Boone alone.

During this period, Boone began his explorations of Kentucky in earnest. Squire returned in July, and the Boone brothers joined other hunting parties for the winter. They started east with their furs in March 1771. Just past the Cumberland Gap, a band of Indians took all of their possessions, leaving them with nothing to show for a winter of hunting except information for Henderson.

In 1773, Boone, his family, and four other families started toward Kentucky to begin a settlement. They were attacked before reaching the gap. Boone’s oldest son, James, was killed in the skirmish.

But Boone was ready to try again when Henderson hired him to cut a trail in 1775. The trail went north from the Long Island to Martin’s Station (now Rose Hill, Virginia). It then swung west and dipped through the Cumberland Gap. It continued to Cumberland Ford (now Pineville, Kentucky) and ended at the mouth of Otter Creek on the Kentucky River. Here, the town of Boonesboro was built at the terminus of Boone’s Trace.

By April 1775, Henderson arrived with forty riflemen, several slaves, and a number of packhorses carrying provisions. Several other small communities quickly sprang up in the new territory, which eventually became the state of Kentucky.

Before the Revolutionary War, over twelve thousand people followed this route to the new frontier. By the time Kentucky was admitted to the union in 1792, over a hundred thousand people had passed through the gap. The governor of the new state, Isaac Shelby, succeeded in getting funds to expand Boone’s Trace to accommodate wagons. The construction was completed in 1796, and the newly improved route was called the Wilderness Road.

From the Iron Furnace, you can hike a restored section of the Wilderness Road, which climbs the mountain to the Cumberland Gap. This trail, restored to the way it looked in 1810, will give you some idea of why it took settlers from six to eight months to make the 208-mile journey along the Wilderness Road. Towering above the furnace is the Pinnacle Overlook, visited later in this tour.

Gap Creek, which runs alongside the furnace, comes from a spring in the nearby hillside. This spring is apparently the one noted by Thomas Walker in his 1750 exploration. It originally emerged from the wall of the Pinnacle, but the highway has since been built over the spring.

If you continue past the furnace for a short distance, you will reach railroad tracks. On the right is the tunnel built by Alexander Alan Arthur’s company to connect Kentucky and Tennessee by rail.

Return to U.S. 25E and continue the climb. In 1996, the route through the gap was changed again upon the opening of the Cumberland Gap Tunnel—actually twin forty-six-hundred-foot tunnels that each have two driving lanes.

After passing through the tunnel on U.S. 25E, stop at the visitor center for Cumberland Gap National Historical Park. Here, you can obtain information about the hiking and camping facilities in the park and view an interpretive film.

From the visitor center, follow the signs to the Pinnacle Overlook. The road winds 3.7 miles up the mountainside. Approximately 2.4 miles from the visitor center, you will see signs for the McCook Earthworks, on the right. This fort was named for a general in the Union army. When the Confederates held the gap, it was called Fort Rains.

During the Civil War, both armies feared an invasion of their territory through the gap. The gap was first controlled by Confederate forces. In 1861, they constructed seven forts on the north slope and cleared the mountains of all trees within 1 mile of each fort. One Union solider, O. G. Swingburg from Ohio, later wrote in 1863, “The trees, which had formerly covered the mountain were all cut down. Their trunks lie tangled and scattered in all directions, to prevent rapid charges of infantry. Surely a valley of death could not have been more skillfully constructed. All who walked that road today would agree that had the charge been made, it would have been the last road walked in eternity. It would have been murder to have ordered that assault.”

As the war progressed, Confederate troops were needed more urgently in other locations, so they abandoned their forts here in June 1862. Union forces under George Morgan moved in and built nine forts facing south. Confederate forces under General Edmund Kirby-Smith bypassed the gap and cut Morgan’s supply line, forcing him to retreat. The Confederates returned to their forts.

In September 1863, Union general Ambrose Burnside moved his force toward the gap. On September 7, Union soldiers captured Gap Spring—the same spring spotted by Walker—which was the major water source for the Confederates. The Confederates, thinking the attacking force was much larger than it was, surrendered. Union forces held what George Morgan called “the Gibraltar of America” for the rest of the war.

Several interesting stories survive from this period. One concerns a Georgia soldier named William McEntire. After his capture at the gap, McEntire spent eighteen months in a northern prison. He eventually returned to his home in Georgia, only to find it burned by Sherman and several members of his family killed. He then moved to Texas. On his deathbed, he asked his grandson to return to the gap a hundred years after his surrender, stand at the Pinnacle, and curse the Yankees for five minutes. On September 9, 1963, McEntire’s grandson fulfilled the deathbed request.

Another legend concerns an eighteen-foot-long gun called “Long Tom.” It supposedly had a range of 5 miles and shot projectiles that some sources say weighed sixty-four pounds and others say weighed thirty-two pounds. The Confederates hauled Long Tom to the top of Cumberland Mountain in 1861. When they abandoned their fortifications, they pushed Tom off the cliff. Upon Morgan’s arrival, he had the gun hauled back to the top of the mountain. When the Union forces left, they spiked Long Tom by driving a rat-tail file into the vent, then pushed the gun off the cliff again. No one knows exactly what happened to Tom after that. The most plausible theory is that the iron was salvaged and melted down for other uses, but some say Long Tom is still out in the woods somewhere.

After viewing the remains of the Civil War fortifications, continue to the Pinnacle. It is an easy two-hundred-yard walk from the parking area to the Pinnacle Overlook. From the overlook, 2,465 feet in elevation, you can supposedly see six states on a clear day. At the foot of the mountain is the town of Cumberland Gap. To the right is Middlesboro, Kentucky.

You can also see Powell Valley, which you drove through earlier in this tour. Ambrose Powell accompanied Thomas Walker on his early exploration of this area. When Elijah Walden and his party of long hunters came through in 1761, they kept finding “A. Powell” carved in trees along the river. They started calling it Powell’s River, and the name endured.

While you’re at the park, ask about taking one of the ranger-led Gap Cave Tours. This cave opened for tourists in 1935 under the name Cudjo’s Cave. It is actually a five-tier cave system. This is the same cave that Thomas Walker wrote about in his journal in 1750. The spring that he noted comes from an underground river that flows inside the cave. Among the cave’s attractions is one of the largest stalagmites in the world. It is sixty-five feet high, thirty-five feet in circumference, and an estimated eighty-five million years old. The name for the cave came from an 1863 novel, Cudjo’s Cave by J. T. Trowbridge. The description of the cave where an escaped slave named Cudjo hid fit the cave at the gap, so the name stuck. The 1-mile hike includes three levels of the cave and has 183 steps. One interesting aspect of the tour is that the park rangers use lanterns to light the way. The tour usually takes two hours. Children under five are not allowed because of safety precautions. You can make reservations for a tour up to a month in advance.

You may also want to walk the trail to Tri-State Peak. It is less than 1 mile on this trail to the top of the ridge where Tennessee, Kentucky, and Virginia come together. Tri-State Trail also marks the beginning of Cumberland Gap Trail.

After touring the national park, retrace your route south on U.S. 25E to Harrogate, then continue approximately 10 miles to Tazewell. You might want to take a brief detour by turning one block west and driving through Tazewell’s small business section. A number of impressive stone buildings are in this community.

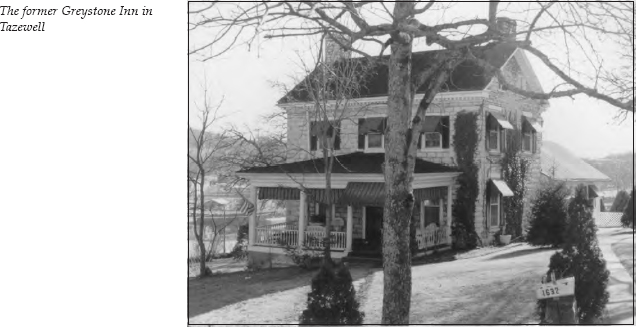

Turn left onto Court Street and proceed to where it ends at Church Street. Straight ahead is a beautiful two-story stone house erected in 1810 by William Graham, an Irish immigrant who opened the first store in Tazewell. During the Civil War, the home became the focal point of a skirmish. Supposedly, the words “I stand here watching Tazewell burn” were written on a third-floor wall of the house when Civil War forces burned the town. The house was later operated as the Greystone Inn. It is still beautifully preserved today.

Turn left onto Church Street and head down the hill toward the Hardee’s restaurant. Turn left and then immediately right to get back on U.S. 25E, heading south.

It is 5 miles to Springdale, where you will see a historical marker on the left for Big Spring Church. This log Baptist church, one of the oldest church buildings in Tennessee, was constructed by Drew Harrell and the Reverend Tidence Lane in the winter of 1795-96. The original building was thirty feet by thirty feet with a thirteen-foot ceiling. It had double doors on one side and a door on the other side for quick exit in case of Indian attack.

U.S. 25E soon begins descending Clinch Mountain. As you make the descent, you will see a sign for a scenic overlook, located on the right. The view from this overlook makes it worth a stop.

At the overlook is a historical marker for Bean Station, the first permanent white settlement in Grainger County. Bean Station was founded in 1781 by William and Jesse Bean, sons of William Bean, Sr., who settled on Boone’s Creek. (For more information about the elder William Bean, see The Bristol to Blountville to Jonesborough Tour, pages 86–87.) By 1792, George Bean, Sr., was advertising in the Knoxville newspaper that he had opened a “Gold Smith and Jewelry Shop” at Bean Station, where he also made and repaired guns.

The Beans actually weren’t the earliest settlers in the area. Supposedly, a family named English (or Ingles or Inglis, depending on the source) lived at this location until their home was attacked by Indians. Some sources say one of the women of the family was sitting in the cabin weaving when she heard a noise outside. She looked through a crack in the wall and was hit in the eye by an arrow. She died instantly. The other women and children in the family were captured by the Indians and taken north toward Ohio.

Some sources claim that a female slave was resourceful enough to tear bits of her apron and leave clues for the men to follow when they returned from their hunting expedition and found the family gone. Other sources suggest that the northern tribes traded the hostages to the Cherokees, who later exchanged them for Cherokee hostages captured by white settlers. At any rate, the family apparently abandoned its homestead.

In 1813, Thomas and Jenkins Whiteside built the famous Bean Station Tavern. Bean Station had long been a major intersection of transportation routes. In its early days, it was the intersection of Boone’s Trace and the Great Indian War Path. Later, it became a crossroads for the stage routes from Baltimore to New Orleans and from Kentucky to the Carolinas. It was only fitting that what became known as the largest and finest inn between Washington and New Orleans cropped up here.

The Bean Station Tavern sported spacious parlors, a ballroom, fifty-two rooms at its height in the 1830s, and space for two hundred guests. It also claimed to have one of the finest wine cellars in the South.

An interesting story is told about a family that came to the tavern in 1808 asking to work in exchange for food and lodging. The woman was hired as a cook, since the local court was in session and the inn had plenty of guests. During the three-week court session, her husband and young son also helped with chores. At the end of the session, they continued their journey to Kentucky, where, several months later, the woman gave birth to another son—Abraham Lincoln.

In 1886, all but eight rooms of the Bean Station Tavern were destroyed in a fire. When the TVA planned to flood the site with Cherokee Lake, it dismantled the remaining rooms. Plans were under way for a restoration project when vandals set fire to the building where the materials were stored. Today, nothing remains of this once-famous tavern except the sign at this overlook; down in the valley, Cherokee Lake now covers the site. A community called Bean Station still exists, but it is located east of the original settlement.

Continue down Clinch Mountain on U.S. 25E. It is 16 miles from Springdale to the junction with U.S. 11W. Turn right, heading west on U.S. 11W. It is 0.5 mile to a roadside park on the left. The stone monument there once held a bronze plaque erected by the Daughters of the American Revolution to commemorate the location of the Beans’ home.

Continue on U.S. 11W for 0.5 mile. You will see Kingswood School on the right. This is the site of what was once the popular resort of Tate Springs.

Samuel B. Tate purchased over six thousand acres surrounding a mineral spring in 1787. The Tate family built a two-story Victorian-style hotel that could hold five hundred people. It was located about three hundred feet from the spring.

In 1876, Captain Thomas Tomlinson purchased the property. For the next thirty-three years, he made it one of this country’s premier resorts. Tomlinson built a gazebo over the spring and added several wings to the hotel, increasing its capacity to six hundred guests. He also constructed the largest swimming pool in East Tennessee, engaged the services of a Swedish masseur, hired a resident physician who developed a popular treatment for arthritis, and constructed a Donald Ross eighteen-hole golf course that was kept trimmed by a herd of sheep.

The resort was the ultimate in class. The hotel had two four-story cupolas on each end of the veranda that stretched the length of the building. Guests were required to dress formally for dinner. Men seated on the veranda had to wear dress shirts, ties, and jackets even in the hottest weather. Before dinner, it was the custom for guests to promenade on the porch from cupola to cupola nine times—the equivalent of 1 mile.

In the main dining room, guests were kept cool by huge overhead fans that were connected through gearboxes to sets of pedals. Servants sat in the balcony during meals and pedaled to keep the fans rotating. The hotel eventually became one of the first buildings in the area to have electricity; the resort had its own powerhouse next to the hotel.

After-dinner dances were frequently held. The live orchestra always opened with “Stardust” and closed with “Goodnight Sweetheart.” During the day, all sorts of activities were offered, in addition to golf. Bridge was the most popular with the ladies. The men enjoyed a different sort of card playing, as described in an article written by Carson Brewer for the Knoxville News-Sentinel: “Fly poker was what folks played when they got too tired or too lazy or maybe too full of moonshine to concentrate on the cards. Each player put down one card and some money. The first man on whose card a fly lit was the winner.”

But the main attraction was still “the taking of the waters.” Each morning at six o’clock, servants walked through the halls calling, “Get your hot Tate water!” The water was served in guests’ rooms in silver pitchers. A brochure suggested, “The water should be taken only on an empty stomach, hot water two to four glasses one hour before breakfast; two hours after each meal should be allowed before drinking the water, drink two to four glasses between meals and at bedtime. If a laxative only is needed, drink moderately, if a cathartic, drink freely.” During “the watering hour” in midmorning, everyone went to the spring. Another was offered in the afternoon.

The resort also boasted an elaborate bathhouse near the two-hundred-thousand-gallon swimming pool. Between thirty-five and forty buildings were located on the grounds. One group of cottages was set aside for male visitors unaccompanied by ladies. This section was called Rowdy Row, because the males could be as rowdy as they wished in this isolated area without disturbing other guests.

The resort attracted such wealthy families as the Rockefellers, Fords, Firestones, Studebakers, and Mellons. But the Depression and the mobility provided by automobiles spelled the doom of large resorts like Tate Springs. The hotel closed in 1936, and the resort ceased operation in 1941. In 1943, Kingswood School purchased the property and established a Christian school for neglected and abused children. In 1963, the old hotel burned to the ground.

Today, you can still see the gazebo over the original spring. The old bathhouse now contains the school’s offices. You can also see the foundation where the hotel once stood. The homes once owned by members of the Tomlinson family are still located on the school’s property. Cherokee Lake covers all but four holes of the golf course, so sheep no longer graze on the eighteenth hole.

Continue on U.S. 11W for 6 miles past Tate Springs. On the left is one of the famous “See Rock City” signs. (For the story about the barns bearing these signs, see The Trail of Tears Tour, pages 356–57.)

As you enter the community of Rutledge 3 miles later, you will notice a sign for Head of Richland Baptist Church. This church, organized in 1818, was named because of its location at the headwaters of Richland Creek. On the other side of U.S. 11W is the road to Avondale Springs. Another inn capitalizing on the health benefits of the water from a nearby spring grew up here, but it never had the popularity and prestige of its nearby competitor.

It is approximately 2 miles on U.S. 11W to the Grainger County Courthouse in the center of Rutledge. Grainger County is the only Tennessee county named for a woman. The name honors Mary Grainger, who married Governor William Blount.

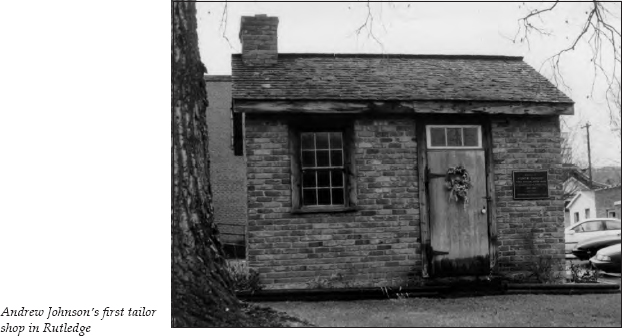

On the courthouse lawn stands a small brick structure that housed Andrew Johnson’s first tailor shop. Johnson stopped in Greeneville on his way westward with his family. There, he was persuaded to work with a local tailor. He later came to Rutledge to set up his own business.

Johnson shared this building with the sheriff’s office. It’s hard to imagine one enterprise, much less two, working out of this small structure. When his former employer in Greeneville died about six months after he came to Rutledge, Johnson returned to that town and established his tailor shop there. (For more information about Andrew Johnson, see The Jonesborough to Greeneville to Bulls Gap Tour, pages 120–21.)

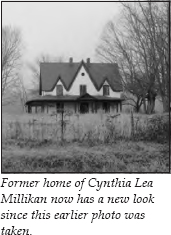

Continue through Rutledge on U.S. 11W for 12 miles. On the right, you will see the Millikan House. Although it has undergone a remodeling since the first edition of this book, this residence, once the home of Cynthia Lea Millikan, still retains its distinctive Gothic style.

The story of Cynthia’s courtship by Sam Houston makes a good tale. Cynthia was the daughter of the prosperous Lea family. As she reached marriageable age, she was encouraged to visit her brother, a prominent attorney in Nashville, in hopes that she would meet and marry an eligible young man. She certainly did just that, because she was soon courted by none other than Sam Houston, who was then the state’s governor. However, when Houston asked for her hand in marriage, she turned him down and returned to her home at Lea Springs. She supposedly told friends she did not care for Houston because he was “the rough and reckless type.” A few years later, Houston did marry, but he separated from his wife after only a few months, resigned his governorship, and returned to live with the Cherokees. Maybe Cynthia knew what she was doing.

Cynthia went on to marry a Baptist minister, the Reverend Elihu Millikan. Millikan was a widower whose wife had died and left seven small children, so Cynthia inherited a family. Although her family supposedly disapproved of the marriage, they at least thought she should live in the style to which she was accustomed. Her father built this home for her as a wedding gift. She lived here until her death and is buried in the nearby Poplar Hill Cemetery.

It is 1 mile to Shields Station, on the left. The first owner of this property was James McDaniel (originally spelled McDannalds), who filed a claim in 1780 and received his land grant in 1790. Shortly afterward, McDaniel was killed by Indians. His daughter sold the property in 1833 to Dr. Samuel Shields and Milton Shields. They opened a store here, as well as an inn and a post office. The tavern, begun in 1790 by McDaniel, was finally completed in the 1830s. This fourteen-room mansion served as a stagecoach stop until sometime around 1860; the stage line was discontinued as travelers switched to rail transportation. The structure was restored to its former grandeur by local historian Thomas Roach in the 1960s.

It is 0.3 mile to a sign on the left for “Red House.” The Red House Tavern and nearby Shields Station were two popular stagecoach stops. Jeremiah Jarnagin built the Red House Tavern sometime in the early 1800s. He painted his house red—the first painted house in the area. Jarnagin lived here the remainder of his life, married five times, and raised thirteen children. The famous structure burned in the late 1940s. The red house where the sign is located is not the original tavern.

It is 0.8 mile on U.S. 11W to an intersection at Breeding’s Restaurant. Turn right, following the signs to TN 61, heading toward Maynardville. You will pass a historical marker for Emory Road, which was a main thoroughfare constructed about 1788.

TN 61 winds north for 12 miles to Maynardville. At Maynardville, turn left, still traveling on TN 61, which runs conjunctively with TN 33 through Raccoon Valley. It is 7.7 miles to a junction where TN 61 turns right, heading north toward Big Ridge State Park. It is 6.5 miles to the entrance to the park.

Big Ridge State Park is one of five demonstration parks organized by the TVA in cooperation with the CCC and the National Park Service as examples of how public recreation might be developed along TVA lakes. This park on the southern shore of Norris Lake offers camping facilities, boat rentals, a swimming area with a sandy beach, and hiking trails.

It is 5.2 miles on TN 61 to the turnoff for the town of Norris, visited earlier in this tour. Proceed past Norris and the Museum of Appalachia to the town of Clinton, located 6 miles past the intersection with I-75.

Clinton is the county seat of Anderson County. Most of its buildings that would be of historical interest were destroyed by fires in the business district in 1905 and 1908. The community has experienced bursts of prosperity thanks to the coal-mining industry, the Magnet Knitting Mills, the building of Norris Dam, and later the Manhattan Project.

Clinton was also home to one of the more interesting industries in the region—pearl cultivation. Pearl-producing mussels thrived in the nearby Clinch River. By 1900, the high-quality Clinch River pearls were being featured at international expositions. Buyers from New York came regularly during the pearling season, which lasted from May to September. Everyone from farmers and fishermen to bankers and lawyers supplemented their income by hunting for pearls.

This bonanza ended with the construction of Norris Dam. The cold water flowing from the bottom of Norris Lake into the Clinch River killed off the mussel population. The use of plastic for buttons would probably have dealt the industry a major blow, but the dam expedited things. A historical marker in a small downtown park acknowledges Clinton’s role as one of the nation’s leading pearl-producing markets.

Continue past Clinton on TN 61 for 9 miles toward Oak Ridge. This route follows the Clinch River and Melton Hill Lake, which is on the river. Approximately 5 miles from Oak Ridge, TN 61 turns right. Stay on TN 95, heading into Oak Ridge. This road becomes the Oak Ridge Turnpike. The American Museum of Science and Energy is located at 300 South Tulane Avenue. Well-marked signs direct visitors to this museum. The small admission fee is worth it to learn about the founding of Oak Ridge.

Before John Hendrix died in 1903, he spent the last few years of his life telling everyone around Black Oak Ridge about his visions. He prophesied that someday the valley would be “filled with great buildings and factories. . . . Thousands of people will be running to and fro. They will be building things . . . and there will be a great noise and confusion and the world will shake.” Hendrix’s neighbors dismissed his rantings—until they had reason to reconsider in the fall of 1942.

In August of that year, President Franklin Roosevelt ordered the formation of the Manhattan Engineer District under the auspices of the United States Army Corps of Engineers. Its mission was to produce an atomic bomb within three years. The Manhattan Project was born.

In October, fifty-six thousand acres of Roane and Anderson counties were purchased by government agents. Over a thousand families were given until January 1943 to vacate their homes. In the case of property purchased by the government toward the end of 1942, the former owners were often given only weeks to move from land where their families had lived for generations.

The area now known as Oak Ridge was selected because the project required plentiful and cheap power, which the TVA could supply, a climate that would permit year-round construction, reasonable land prices (the going rate was forty-five dollars an acre), and an inland location, which would lessen the chance of enemy attack by sea or air. Leslie R. Groves, who headed the Manhattan Project, gave another, not altogether flattering, reason for selecting Tennessee. He said, “Tennessee girls would be much more easily trained . . . [because] the women here were not so sophisticated—they hadn’t been reared to believe they ‘knew it all.’ ”

Considering that it was a government-run operation, the Manhattan Project moved with incredible speed. In the fall of 1942, even before all the land had been purchased, construction workers were brought in to start laying the 300 miles of highway and 55 miles of railroad track that would be needed.

The project required three separate plants—an electromagnetic isotope separation plant and a gaseous diffusion plant, both of which enriched uranium, and a complex called X-10, which served as a laboratory and housed the nuclear reactor. To ensure secrecy, fences were erected around 90 square miles of land. After April 1, 1943, only seven entrances led into the area. A pass was necessary to get by the guards.

Groves initially approved three buildings to house five “racetracks,” or calutrons, which would separate the vital uranium 235 from uranium 238. These buildings covered an area greater than twenty football fields. Eventually, the Y-12 complex included 268 permanent buildings. Groves ultimately constructed ten racetracks instead of the five he originally estimated he would need. Twenty thousand construction workers moved into the area to build these plants. Twenty-four thousand people were on the payroll for the Y-12 complex alone.

Tennessee Eastman, a subsidiary of Eastman Kodak, was contracted to operate the electromagnetic separation plant. The company hired a work force of forty-eight hundred people to run the calutrons twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week.

K-25, the gaseous diffusion complex, covered as great an area as the Y-12 complex. The building was four stories high, almost half a mile long, and a fifth of a mile wide. It enclosed 42.6 acres under one roof.

Numbers were used for everything instead of names to improve secrecy. No one except a small group of scientists knew what they were working on. Rumors were rampant. Some people thought this was just a newfangled social experiment designed by Roosevelt to keep people busy. Some thought a new Vatican was being built for the pope.

In 1940, the population of Anderson County was approximately twenty-six thousand. By June 1945, it had risen to seventy-five thousand. Jokes were made about the quickest way to get into Oak Ridge—stand on a corner and wait for a bus, or stand in a field and wait for the town to grow up around you.

The logistical problems were staggering. To house this influx of workers, a city was built virtually overnight. In fact, at one point, construction crews were assembling one prefab house every thirty minutes. Seven thousand trailers were brought in for housing. Black workers were housed in fourteen-by-fourteen-foot “hutments” with dirt floors and coal stoves. These shelters were little more than tents, five people sleeping in a single hutment. Because men and women were segregated in the hutments, black families could not even live together.

Easy distribution of beer helped keep the workers happy, as did the four theaters, the six recreation halls, the thirty-six bowling alleys, the eighteen ballparks, the twenty-three tennis courts, the skating rink, and the swimming pool. The cafeterias served up to fifteen hundred people an hour.

And what about transportation? Freight trains operated twenty-four hours a day, five trains running on each eight-hour shift. Passenger trains ran to and from nearby Knoxville. In one month, over 23,000 workers rode the trains that left Knoxville at 5:05 a.m. and returned at 6:05 p.m. Workers rode for free on the 350 buses in Oak Ridge and on the 400 buses used to transport nonresident workers to and from the plants. Oak Ridge operated the nation’s seventh-largest transit system.

The cost for building the whole town of Oak Ridge, not including the plants and the laboratory, was ninety-six million dollars. Ten thousand people were employed just to keep this gargantuan town running.

But probably the most amazing thing of all was how well the secret was kept. When the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, Japan, on August 6, 1945, most of the workers and residents of Oak Ridge were stunned to learn that the enriched uranium used in it came entirely from Y-12, and that their whole community was centered around producing this bomb. Over a hundred thousand people were involved in this two-billion-dollar program.

What would happen now that the war was over? The trailers and hutments were removed. The town’s population fell by thirty thousand by mid-1946. In January 1947, the Manhattan Project was transferred to a newly created civilian agency, the Atomic Energy Commission. In 1949, the gates were opened, except for certain restricted plant areas. The homes and lots were offered for sale in 1956, and the city incorporated in June 1959. By 1960, seventeen thousand people were employed by the Atomic Energy Commission, but 55 percent of them lived outside Oak Ridge. The Atomic Energy Commission has now been absorbed into the Department of Energy.

In March 1949, the American Museum of Atomic Energy opened on the same day that the gates to “the city behind the fence” were thrown open. In 1975, the name was changed to the American Museum of Science and Energy.

In the museum, visitors can see hundreds of models, gadgets, devices, and machines highlighting all types of energy. The most popular exhibit is probably the one that makes a person’s hair stand straight on end. At the visitor center in the museum, you can pick up a map for a 38-mile self-guided auto tour of the entire area.

This ends the tour. You can easily reach I-40 and I-75 by following the clearly marked signs.