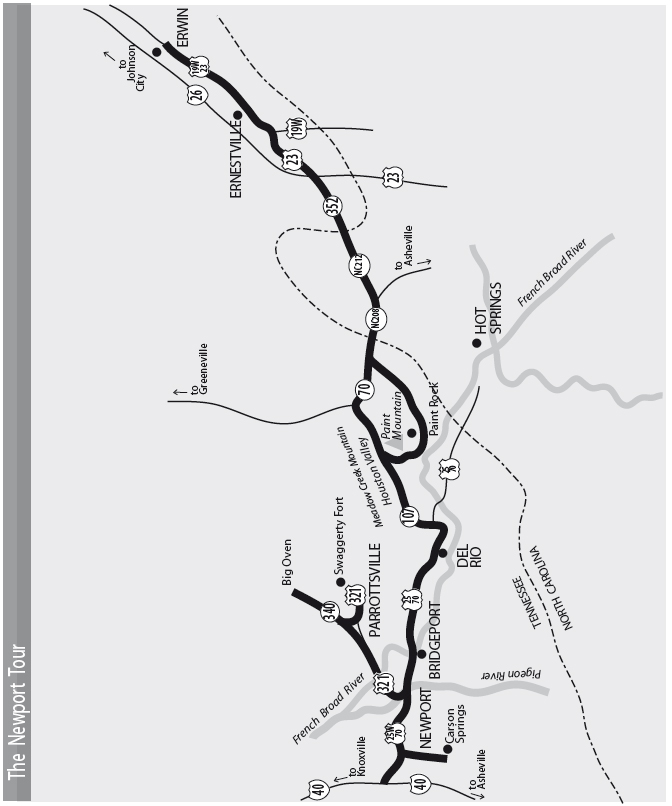

This tour begins in Erwin and travels to Ernestville, Shelton Laurel, and across Houston Valley to Paint Rock. It continues to Del Rio and Newport, then travels to Parrottsville and back to Newport. From there, it goes to Carson Springs.

Total mileage: approximately 120 miles.

From Erwin, take I-26 to Exit 43. Begin traveling on U.S. 19W/23 toward Asheville, North Carolina. You will turn right onto U.S. 19W/23, but note that Granny Lewis Creek is 0.3 mile to the left.

In 1793, the Lewis family was the victim of a bizarre turn of events. According to local historian Pat Alderman, the Cherokees meant to destroy John Sevier’s family. They sent out three bands of braves on a mission. One band of twenty-eight mistakenly found the isolated cabin of William Lewis. His cabin and barn were located on South Indian Creek near the mouth of Granny Lewis Creek. Lewis was away from home when his family was attacked. His wife and five of his children were killed. One son managed to escape to report the massacre. One daughter was taken captive. Folklore says Lewis tracked the Indians down and exchanged a gun for his daughter.

This region was also home to a colorful character named Kan (short for Kanada) Foster. At one time or another, Kan owned most of the land in the area. He and his first wife, Mary, owned five thousand acres along Spivey and Coffee ridges. When Mary died, Kan divided his land among his nine children and moved to Higgins Ridge. When he married a second wife, they settled in the Devil’s Creek section near the mouth of Granny Lewis Creek and raised seven more children. That farm is still called Can Lot on topographical maps today—mapmakers, at least, know the proper spelling of Canada.

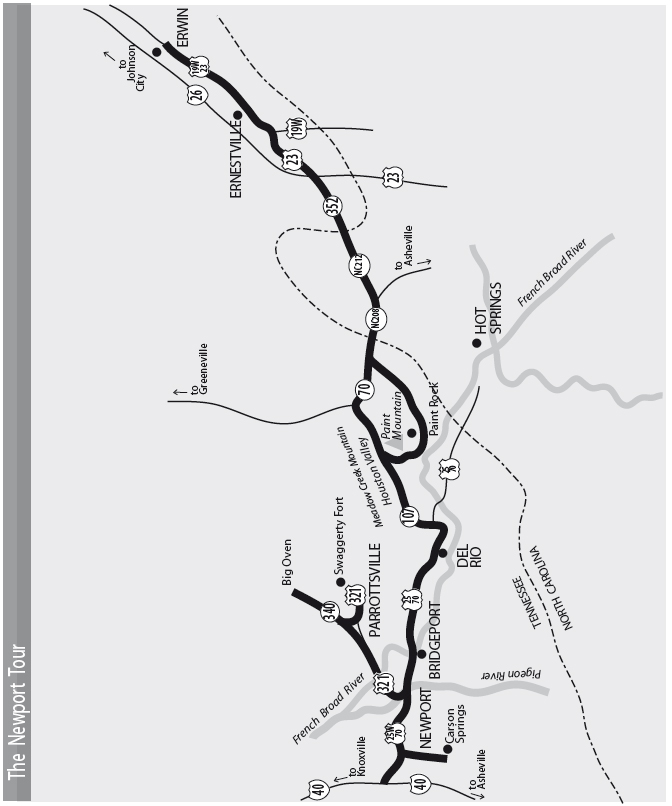

Kan Foster was immortalized in a totally unexpected way. In January 1858, an illustration of him appeared in Harper’s Monthly. This familiar image is now used whenever anyone wants an old-fashioned etching of an early mountain man. David Strother, the chief illustrator for Harper’s Monthly, was on a field trip, sketching for some writers preparing stories about the Alleghany Mountains. Coming down the Tennessee side of Big Bald Mountain, Strother and his party lost their way—not to mention their horses—until stumbling on Kan’s home, then located near Spivey Creek. Kan and his oldest son spent the following day finding and returning the horses. While Kan and his son were searching for the horses, Strother sketched his family, watermill, and neighbors. Later, he sketched Kan himself. Strother also sketched the adventure of tumbling down the mountainside the day before. The sketch of this episode has also been reproduced repeatedly.

It is 1.1 miles from the right turn at Exit 43 to Ernestville, where U.S. 19W goes south to Burnsville. Continue straight on U.S. 23. The road parallels South Indian Creek.

It is 4.9 miles from Ernestville to where U.S. 23 heads south to Mars Hill, North Carolina. Rocky Fork, South Indian, and Devil Fork creeks all come together in this general area. Turn right onto TN 352 West, following Devil Fork Creek.

Ahead on the right is Flint Ridge. In January 1789, while John Sevier was still governor of the ill-fated State of Franklin (see The Beauty Spot to Nolichucky Tour, pages 68–70), he learned that a large body of Creeks and Cherokees was gathered at Flint Ridge and that those warriors planned to venture forth in small groups to raid isolated cabins and settlements. Sevier gathered a force and marched up South Indian Creek, while another force entered the opposite side of the gorge from Devil Fork Creek.

After the ensuing battle, Sevier buried 145 Indians. His official report to the privy council of the State of Franklin gives insight into the frontiersmen’s side of the battle: “Our loss is very inconsiderable; it consists of five dead, and 16 wounded; amongst the latter is the brave Gen. M’Carter, who, while taking off the scalp of an Indian, was tomahawked by another whom he afterward killed with his own hand. I am in hopes this brave and good man will survive. . . . We suffer most for the want of whiskey.” The battle proved to be one of the last engagements with Indians in the area.

It is 4.4 miles to the North Carolina–Tennessee state line. The road becomes NC 212 as it enters Madison County. As you cross the state line, you are crossing Devil Fork Gap, the gap Sevier closed off to the retreating Indians during the Battle of Flint Creek.

It is 14.3 miles along this winding road to the junction with NC 208. At this intersection is a historical marker for the Shelton Laurel Massacre. On your way through Madison County, you may have noticed signs for Shelton Laurel Backcountry Areas. This region was the center for Union sympathizers in Madison County during the Civil War.

Madison County was one of the most hotly divided areas in the South during the war, but it took a shortage of salt in the winter of 1862–63 to bring matters to a head. Shopkeepers in the town of Marshall tended to be southern sympathizers. They frequently denied salt to Union supporters. That January, some fifty armed men from Shelton Laurel traveled to Marshall and plundered the town’s salt depot and stores.

A company under Confederate lieutenant colonel James Keith was dispatched to round up the culprits. Fifteen men and boys were captured on the first sweep. They were quartered in a cabin and denied food while the search continued. Another thirteen suspected culprits were then captured. Thirteen of the twenty-eight prisoners were subsequently marched to a field near Shelton Laurel Creek. They were ordered to their knees and told to pray, and then they were shot. Their bodies were thrown into a nearby sinkhole. Four women who had followed to see what would happen to their loved ones protested. One of them was stripped bare and flogged. The other three were tied to trees with ropes around their necks.

The local militia leader wrote Zebulon Vance, the governor of North Carolina, that twelve “Tories”—an apparent miscalculation—had been killed and another twenty, including the four women, captured. Vance ordered his friend Augustus Merrimon, the solicitor for the Eighth Judicial District, to visit the scene and send him a report. Merrimon submitted a horrified account that read in part, “Such savage and barbarous cruelty is without a parallel in the State and I hope in every other.” He charged that Keith’s men had killed the captives without any semblance of a trial, and that Keith was the man who ordered them to kneel and then shot them without warning. Merrimon also estimated that “probably eight of the thirteen” who were executed were not in the band of looters. Ultimately, only four prisoners—not twenty—were brought in alive. Governor Vance pronounced the incident “a horror disgraceful to civilization” and demanded that court-martial proceedings be brought against Keith. Others found it difficult to blame Keith for his reaction to the hot resistance he had encountered from snipers in Shelton Laurel. He was finally allowed to resign without facing a court-martial, and the relatives of the slain swore revenge. The incident earned the county the sobriquet “Bloody Madison.”

Stay straight at the intersection of NC 212 and NC 208; you are still on NC 208. It is 2.8 miles to a historical marker for the home of Frances Goodrich.

Early in the nineteenth century, a man named Allan kept a stand here where drovers could spend the night while driving cattle, sheep, horses, and swine from Tennessee to the South Carolina and Georgia markets. This route and one following the French Broad River were popular trails for the drovers. More about these livestock drives will be presented later in this tour.

In 1890, Frances Goodrich came to the region as an unpaid assistant to a teacher sent by the Presbyterian Church to educate and convert the mountain people. Goodrich loved the nickname given to her by the local people—“the Woman Who Runs Things.”

The Yale School of Fine Arts was the first art school at an American university, as well as the first part of Yale to admit women. From 1879 to 1882, Goodrich had studied art and painting there. She later went to New York to be an artist, but sometime in the late 1880s, she decided to change her focus to social service.

Soon after arriving at Brittain’s Cove in western North Carolina, Goodrich organized a meeting of local women at “The Library,” one of the small buildings she paid to have built there. At one of these “mothers’ meetings,” as they were called, a local woman gave Goodrich a gift of a Double Bowknot coverlet. Goodrich had been searching for a way to help the local mountain people without injuring their pride. With the coverlet came the birth of the famous Allanstand Industries.

Goodrich took the coverlet north to confirm what she suspected—that a large potential market existed for handmade quilts and coverlets.

On a subsequent trip to Greeneville, Tennessee, to attend a presbytery meeting, Goodrich and her fellow travelers passed through Allanstand. She had heard you could identify the Laurel folk by the distinctive, homespun red clothes they wore; here was evidence that the old-time weaving tradition was still alive.

By the end of 1897, Goodrich opened a school and a cottage, which quickly needed to be expanded. There, she began supervising the making of quilts and coverlets by local women. The first exhibition of the crafts of the Cottage Industries Guild was held in 1899. By 1908, Goodrich’s operation was called Allanstand Industries, with a shop in Asheville.

In 1931, to ensure that Allanstand would continue after her death, Goodrich gave her business to the recently formed Southern Mountain Handicraft Guild. The guild, still thriving today as the Southern Highland Craft Guild, sells its members’ wares at several locations in the area.

It is 2.8 miles to the Tennessee–North Carolina line. The highway is now called TN 70 North. After 3.6 miles, turn left, following the signs for Paint Creek Campground. Travel 1.2 miles and turn left onto Lower Paint Creek Road. It is 1.7 miles to a sign announcing that you’ve entered the Paint Creek Corridor. Turn right, following the one-lane paved road that parallels Paint Creek.

This 5-mile route follows the former Paint Mountain Turnpike, which travelers in the nineteenth century used for their fourteen-hour journey between Asheville and Greeneville.

During the early 1900s, Patterson Lumber Company logged in this area. The lumber company converted 4 miles of Paint Creek into flumes that carried logs to the French Broad River.

Along this route today, you’ll find camping and picnic areas. You’ll also see numerous fishermen, since the creek is stocked with rainbow trout.

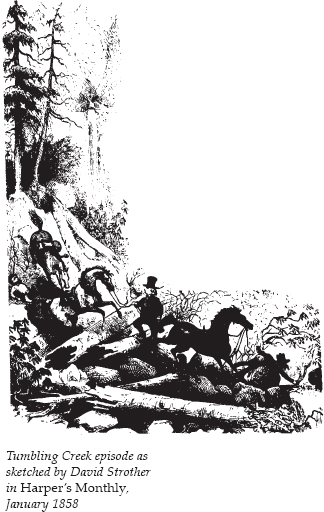

The Paint Creek Corridor ends at Paint Rock on the banks of the French Broad. As the road curves around the rock formation, you will come upon a stunning view of the French Broad River ahead and on your right.

In her book The French Broad, Wilma Dykeman explains how this river received its name. Some of the first white men to explore the region were the long hunters, who spent extended periods in the wilderness on hunting expeditions. These hunters named the river. Dykeman says,

The rivers must have impressed them by their width for they named them First and Second and English Broad. And when at last a party of these trail breakers climbed the Ridge and stood in a gap facing toward the unknown western land under control of France by way of the Mississippi, they looked at the new river they found in the valley just beyond the Blue Ridge and called it the French Broad. It flowed toward the lands and rivers owned by France; when a Long Hunter had gulped from a spring on the far side of the dividing mountains, he could say he had drunk of the French waters.

The impressive formation known as Paint Rock has been an area landmark for centuries. In 1799, a commission was appointed to establish the boundary between North Carolina and Tennessee once and for all. David Vance, Joseph McDowell, and Mussendine Matthews assembled at the Virginia border that May with surveyors John Strother and Robert Henry. The men worked their way south. Strother kept a daily journal that provides some of the best material available about early frontier life.

On June 28, the men dropped a plumb line from the top of Paint Rock and established its height as 107 feet, three inches. Strother reported that Paint Rock “rather projects out” and that “the face of the rock bears but few traces of its having formerly been painted, owing to its being smoked by pine knots and other wood from a place at its base where travellers have frequently camped. In the year 1790 it was not much smoked, the picture of some humans, wild beasts, fish and fowls were to be seen plainly made with red paint, some of them 20 and 30 feet from its base.”

Strother also put to rest the argument voiced by some Tennesseans that the “painted rock” referred to in the Act of Cession—the act by which North Carolina ceded its western lands, starting the State of Franklin movement—was farther downstream. Strother wrote that Paint Rock “has, ever since the River F. Broad was explored by white men, been a place of Publick Notoriety.”

After viewing Paint Rock, you can backtrack 0.2 mile and take Paint Mountain Road as it climbs the hill on the left. If you take Paint Mountain Road from Paint Rock, you will have a 5-mile drive on an unpaved, narrow road. The route climbs to the top of the ridge at Lone Pine Gap before making the descent to intersect TN 107. Although you can travel this road without a four-wheel-drive vehicle, it might be wise to take the following alternate route if you have an RV.

The alternate route follows paved roads. Backtrack along the corridor to TN 70. Turn left onto TN 70 and travel 2.5 miles to TN 107. Turn left, heading west on TN 107. After 4.8 miles, you will see Pine Spring Baptist Church on the left. This is where those who choose to travel Paint Mountain Road will connect to TN 107.

From Pine Spring Baptist Church, turn left onto TN 107. It is 5.3 miles to the turnoff for Meadow Creek Lookout Tower, on the right. It is 2.4 miles on this gravel road to a parking area. Located off this road are several horseback and hiking trailheads, including those for Meadow Creek Mountain and Bitter Creek Mountain trails. This area is in the Nolichucky/Unaka District of Cherokee National Forest. (See the appendix for the address and phone number of the district ranger’s office in Greeneville.)

From the parking area, a short walk along a well-maintained path leads up the hill to the observation tower. The huge markings reading “C9” serve as a landmark for aviators. The view from the tower is beautiful on a clear day.

Retrace your route to TN 107 and turn right. It is 3.5 miles to the junction with U.S. 25/70 West. To your left are Hot Springs and Asheville. Turn right, heading toward Newport. You are traveling alongside the French Broad River once again. In the summer, the foliage may prevent you from getting a good look at the river.

From the early 1800s until the mid-1880s, when the railroad through the mountains was finally completed, this same route along the French Broad was the gateway for a large traffic in Tennessee livestock herded to market in the Carolinas. An estimated 150,000 to 200,000 hogs were driven along this route every year.

Charles Lanman describes the turnpike road along the French Broad in his Letters from the Alleghany Mountains, written in 1848:

The French Broad must be considered one of the most beautiful rivers in this beautiful land. . . . Its shores are particularly wild and rocky, varying from one to four hundred feet in height, usually covered with vegetation. . . . Over this road also quite a large amount of merchandise is constantly transported for merchants of the interior, so that mammoth wagons, with their eight and ten horses and their half civilized teamsters, are as plenty as blackberries and afford a virulentic variety of profanity to the stranger.

The drives from Cocke, Greene, and Jefferson counties in Tennessee usually began around the first of November. The highways were run by turnpike companies, which charged the drovers a toll on each head of livestock. The herds could usually travel from 8 to 10 miles a day, stopping at night at stock stands along the way. The stands provided food and lodging for the drovers and pens and corn for the livestock. The term lodging might be stretching things a bit, for sleeping quarters were usually crowded. It was not uncommon for ten to twelve herds numbering from three hundred to one or two thousand animals apiece to stop overnight and feed at the stands. At least forty men often slept inside the stands. The stand keepers usually made five beds on the floor of each room, three men sharing a bed. For most, this arrangement was preferable to sleeping outside with the animals.

As you travel along U.S. 25/70, you will see railroad tracks on the other side of the river. Although the need for a railroad through these mountains was obvious for decades, various attempts to complete the project met with failure. As early as 1831, a newspaper called The Railroad Advocate promoted the building of railroads in East Tennessee. But political fighting postponed any real progress.

After the Civil War, railroad building started again. By 1868, one section from Morristown to Wolf Creek near the North Carolina line was completed. Things were looking up for completing the line to Old Fort, North Carolina, when officials from the Western North Carolina Railroad absconded with four million dollars’ worth of bonds from the company treasury. Finally, the state of North Carolina purchased the company in 1875 and completed the railroad in 1882 with the aid of legislation permitting the use of convict labor. The construction of the railroad took a heavy toll, as over five hundred convicts lost their lives completing the project.

Driving along the French Broad today, it is still easy to see why travelers on the completed railroad wrote enthusiastic descriptions of this route for magazines, travel books, and even novels. One author went so far as to say of the surrounding mountains, “In comparison with them, the Catskills are a suburb; the White Mountains ornamental rockwork; and the Adirondacks, a wood-lot.”

Follow this scenic route for 2.9 miles to the Del Rio post office. On the left 0.1 mile past the post office is a rock monument. The plaque notes that Grace Moore’s birthplace is 4 miles away.

For many years, being Grace Moore’s birthplace was one of the area’s greatest claims to fame. Grace Moore was at the peak of her career when she met an early death in an airplane accident in Copenhagen, Denmark, in 1947. At the time of her death, Grace had spent several successful seasons with the Metropolitan Opera, beginning with her debut in 1928. She had also appeared in several motion pictures, including One Night of Love, for which she received an Oscar nomination. Doubleday published her autobiography, You’re Only Human Once, in 1944.

Her life began in the home of her maternal grandparents, William and Emma Stokely. That home stood on the west bank of Big Creek between Del Rio and Nough (sometimes known as Slabtown). Since Grace Moore may not be a household name to those born after her death, it is interesting to note what critics say about her movies. Stephen Scheuer, in his Movies on TV, calls One Night of Love “one of those marvelously stupid Moore opera movies. . . . The singing and music stink, but it’s all so delirious that no one need care.” This may not be very complimentary of Grace’s movie career, but it certainly makes the movie sound intriguing in a campy way. Whatever present-day critics may think of Grace Moore, the people of Cocke County who remember her fame still think of her with pride.

After leaving Grace Moore’s monument at Del Rio, continue alongside the French Broad. It is 3.1 miles to a small roadside area on the left. The area has stone picnic tables and is marked by large boulders. In the fall, it provides a good view of some small, scenic rapids in the river. In the summer, it may be harder to catch a glimpse of these rapids.

It is 3.4 miles from the picnic area to the James T. Huff Bridge across the French Broad River. On the other side of the bridge is the community of Bridgeport. The origin of its name is obvious. It was the location of the first bridge in the county.

As you travel the 3.5 miles from the bridge into Newport, you will notice high limestone cliffs along the opposite bank of the river. Many of the caves along this ridge attract spelunkers.

The history of Newport is intertwined with that of a community once known as Clifton. Before white settlers arrived, Indians traveled through this area on the Great Indian War Path, which ran from near what is now Chattanooga to the Watauga River near Johnson City. (For more on the Great Indian War Path, see The Rogersville to Kingsport Tour, page 154.) The path crossed the Pigeon River at what came to be called the War Ford.

By 1799, the settlement of New Port had grown up around the ford on the nearby French Broad River. A ferry was built there, and the landing became the center of flatboat navigation on the French Broad.

Henry Ker, a traveler in the early 1800s, wrote this impression of New Port:

It is the most licentious place in the State of Tennessee, containing about twenty houses of sloth, indolence and dissipation. It is not my desire to stigmatize the character of any place; but when I discover people inhabiting a country of so much importance, and where they live in peace and plenty, subject only to wholesome laws, continually violating the laws of God and their country, I cannot avoid expressing my disgust, and considering them an injury to their country and a disgrace to the human family.

Judging from histories of New Port, it seems that some local historians—and especially the natives of nearby Clifton—felt the same way toward this community. Clifton was on the Big Pigeon River about 1.5 miles south of old New Port. The two communities existed independently until 1867, when the railroad came to Clifton. Soon, residents of New Port lusted for the activity that the railroad had brought to Clifton.

In the years after the Civil War, it was necessary to replace the destroyed jail in New Port. The courthouse was also in disrepair. Many wanted to build the new jail and courthouse in the thriving community of Clifton. According to state law, an election was required to move a county seat. To avoid a hard-fought election, officials decided to simply expand the city limits to include Clifton. That way, they would simply be moving the courthouse within the same town.

A seventeen-year legal battle that went all the way to the state supreme court found that this move was illegal. The local historians must have been Cliftonites, judging from the condemnations in their descriptions of this legal battle. The courthouse was finally built in the town of Clifton in 1884. However, it was a Pyrrhic victory. Although the county seat moved to Clifton, the residents chose Newport as their community’s name. The former New Port was called Old Town; Clifton was now Newport. Today, all this area is simply Newport.

At approximately the same time this political fighting was going on, Alexander Alan Arthur arrived in Newport. Arthur was the American head and general manager of The Scottish Carolina Timber and Land Company. Early in the 1880s, he located virgin timber stands along the Pigeon River and proposed to build booms to float his timber down to Newport and on to Knoxville.

Arthur, a world traveler born in Canada and educated in Scotland, shook up the town from the moment he arrived. Wilma Dykeman describes him in The French Broad:

He had about him the well-fed, intelligent suaveness of a man accustomed to importance: important friends and events, large transactions brought to successful conclusion. The fine cloth of his black coat, the fit of his trousers, the very heaviness of the gold watch chain lying across his stomach, even these objects were invested with a life of their own, because he had chosen them in the faraway cities of the world, because they had been worn in the company of Leaders on Occasions far above the average experience.

Arthur didn’t arrive alone. He brought investors from Edinburgh, Glasgow, London, Canada, South Africa, and the Sudan. He also brought Nellie Goodwin Arthur, his beautiful twenty-year-old wife. Mrs. Arthur was so mortified by the social conditions she encountered that she quickly sent home to Boston for two Irish girls who had been with her family for years. When Katy and Mary arrived, they burst into tears to see where their young mistress was living.

But Arthur was completely wrapped up in his company. The preliminary work took two years. Then the logs began to roll down the flumes into the river. They were sawed into twelve-by-twelve and twelve-by-eighteen boards. If they weren’t perfect, the wood was left to rot.

Next, Arthur expanded his vision to include the town. He drew up a city plan with a park and a circle surrounded by villa sites. The plan included a town hall, clubhouses for varying strata of society, and even a college. On the heights across and above the river was to be a grand hotel on “The Palisades,” along with the leading residential area. Arthur also planned the Pigeon River Regatta and supervised several years of “tournaments.” During these tournaments, mounted steeds and men calling themselves names like “the Knight of St. George” and “the Duke of Nola Chucky” did combat for the queen of the event.

He also built Arthur House, a huge Victorian dwelling designed to showcase the types of wood native to the area. Each room was finished in a different wood. When Mrs. Arthur returned from her confinement in Knoxville with a new daughter, “the Mansion,” as it was known locally, was complete.

But it all came crashing down, literally, in the spring of 1886. Several days of heavy rain caused the booms to break. Wilma Dykeman describes the devastation this way: “Logs from thousands of trees boiled over the broken dams, smashed together in a grinding roar and surged on down the current like giant toothpicks tossed by some elemental energy. . . . Ripping out chunks of riverbank, lodging on boulders and in fields where the water had overflowed, millions of board feet of tulip-poplar logs were carried down the Pigeon into the French Broad, on down the French Broad and into the Tennessee.”

The company was ruined. The exotic foreigners departed. Arthur moved to Knoxville, where he continued to raise money for new entrepreneurial schemes. He eventually developed the town of Middlesboro, Kentucky, where he was known as “the Duke of Cumberland.” But Newport would never again be quite as cosmopolitan as it once was. (For more about Arthur’s activities in Middlesboro, Kentucky, see The Norris to Cumberland Gap to Oak Ridge Tour, pages 176–77.)

As you enter Newport, you will see the ConAgra Foods plant on the right. ConAgra is the current name for the conglomerate that has seen the merger of such brands as Quaker Products, Stokely, and Van Camp. (For more information about the Stokelys and their company, see The Dandridge to Sevierville Tour, page 242.)

If you circle behind the plant, you will see a large white cross planted atop the cliffs on the other side of the Pigeon River. In October 1900, work was under way to raise the railroad grade along this stretch. Because freight trains had to slow down, young boys often hopped them to ride to the other side of town. Twelve-year-old Vassar Brown was killed trying to hop a freight. A friend of the family placed the cross on the cliff as a memorial. It still stands and is a popular subject for photographers.

Return to U.S. 25/70, also known as Broadway. As you continue into town, you’ll notice something unusual about Newport’s traffic lights. Each stoplight has a number under it. It’s a great idea for giving directions. Locals just say, “Go to traffic light #3 and turn left.”

To the left of stoplight #9 stands the Rhea-Mims Hotel. During its heyday, this was considered one of the finest hotels along the Dixie Highway. An entry in the WPA Guide to Tennessee notes that millstones once used by Indians adorn the arch that extends along the front of the building.

At stoplight #7, turn right onto U.S. 321 (McMahan Street), heading toward Parrottsville. At the end of the bridge across the Pigeon River is a historical marker noting that the War Ford is 2 miles east. The marker says that one of the final battles of the Revolutionary War was fought at this site. In August 1787, General Charles McDowell raised an army of five hundred mounted militia. They came across the mountains and joined a similar number led by John Sevier to fight the Cherokees, who sided with the British during the war. After a three-month campaign in the area, the final skirmish between the Cherokees and the American forces took place here. (For more information about the Cherokees during the Revolutionary War, see The Rogersville to Kingsport Tour, pages 156–58.)

Just past the bridge, turn right, heading up the hill to Clifton Heights. The homes built by W. B. and James R. Stokely, two of the founders of Stokely Brothers, can still be seen in this residential area. The two homes sit next to each other at the top of the hill.

Follow Clifton Heights Road as it circles the mountaintop. It comes out again on U.S. 321. Turn right onto U.S. 321, once again heading toward Parrottsville. It is 1 mile to a second bridge. This one crosses the French Broad River and marks the location of the original New Port settlement.

It is 4.6 miles to the intersection where TN 340 turns north. Turn left onto TN 340 and travel 3.1 miles. You will cross an interesting natural phenomenon without even noticing it. When you see Harned Chapel Methodist Church, a white church on the right, either turn around or park in the church’s parking lot and go back a few feet to view Big Oven. The road actually passes over the top of this natural bridge, but all you can see are guardrails that make it appear like a simple culvert. This is the only natural bridge in Tennessee crossed by a state highway.

Two natural bridges are located in the area—Big Oven and Little Oven. Big Oven is 50 feet wide and about 150 feet long. It has an arch about 15 feet above a creek that remains dry except during the rainy season. It stays dry because Oven Creek disappears underground approximately 200 yards east of the bridge and reappears again about the same distance west. Little Oven is about 0.25 mile downstream.

Between the bridges is a tunnel cave three hundred yards long with a ceiling fifteen to twenty feet high. This is known as the Roaring Hole. It is said that this tunnel made an ideal location for moonshiners in earlier days. About fifty feet from the entrance of the tunnel is a vertical shaft called “the Chimney” that penetrates the ceiling and forms an opening through the roof. Moonshiners supposedly used the Chimney as a sort of elevator—the money came down and the liquor was passed up by means of a rope.

It’s obvious from all the litter that this spot is a popular gathering place. No designated path leads down to the tunnel, but you’ll see lots of well-worn trails. It is not an easy descent, but you will find the rock formations interesting if you go down to the creek bed.

After viewing the bridge, retrace your route to U.S. 321. Turn left, heading toward Parrottsville, one of the oldest towns in Tennessee. This community was settled by a Frenchman named John Parrott.

One of the earliest homes in Parrottsville, the Hale House, was built in 1830. It became a popular tavern on the Great Stage Road.

One of the area’s finest houses once stood at what is now the site of the Methodist church. It was supposedly three stories high and had twelve large rooms and three great halls, with a stairway in each hall. On the second floor was a ballroom; the entire front of the second story could be made into one large room by sliding partitions. After the Civil War, the church purchased the property and housed the Parrottsville Seminary there; Parrottsville was the site of the Old Camp Grounds, where Methodist preachers conducted camp meetings. But the mansion was finally razed and replaced by the present church.

Continue through Parrottsville on U.S. 321. It is 1.2 miles to Swaggerty Fort, on the left. You’ll see the fort just after crossing Clear Creek. One of only two remaining blockhouses in Tennessee, it was built about 1787 by Jim Swaggerty for protection from Indians. It consists of three levels. This cantilevered structure was built over Clear Creek, ensuring a constant water supply. The interior was constructed without using any nails. Today, the fort serves as a favorite subject for tourists’ photographs.

Turn around at the fort and retrace your route through Parrottsville and into Newport on U.S. 321. At stoplight #7, turn right, following U.S. 321. At stoplight #6, you will see a historical marker on the left. It notes the birthplace of Kiffin Yates Rockwell, born in 1892 in a house five hundred yards south of the marker.

When World War I broke out in Europe in 1914, Kiffin, his brother, and a friend were the first American citizens to offer their services to France, joining the French Foreign Legion. After being wounded, Kiffin transferred to the French Army Aviation Corps. He and three others founded the Lafayette Escadrille. In July 1916, Kiffin engaged in more air battles than any other pilot in French aviation. In September of that year, he was killed in a battle with a German plane. He was buried in France near where his plane fell. The Legion of Honor and the Croix de Guerre were among the many medals he was awarded.

At stoplight #3, where U.S. 25/TN 70/TN 9 goes straight and U.S. 321 turns left, you will see the Cocke County Memorial Building, which stands on the homesite of the Sanduskys, one of Newport’s earliest families.

Emanuel Sandusky emigrated from Poland to America sometime around 1775–76. He settled first in Jacob Brown’s settlement in what is now Washington County. He and his wife had seven sons and eight daughters, including a daughter named Mary, who was born in 1783. When Mary was three years old, she was kidnapped during an Indian raid. Sandusky spent years searching for her. After nine years, he found a girl of twelve—the same age his daughter would have been. He purchased her and took her home. Mrs. Sandusky found a scar on the child’s arm that positively identified her as their missing daughter.

Mary later met John Gorman, who had come from Maryland on his way to Louisiana and stopped in Newport to build a houseboat. They married in the early 1800s and had eleven children. Some of Newport’s most influential early citizens were descended from this marriage.

If you are taking this tour on a Wednesday afternoon, turn left at stoplight #3 onto U.S. 321 for a brief detour to the Newport–Cocke County Museum, located in the Newport Community Center at 433 Prospect Avenue. In the museum are permanent collections of antiques and artifacts. Two exhibits are of special interest. One contains several items belonging to Ben W. Hooper, who will be covered later in this tour. The other concerns Grace Moore. Grace’s exhibit includes costumes from two of her Metropolitan Opera performances, her makeup case—including her false eyelashes—and original music scores.

Retrace your route to stoplight #3 and turn left, following U.S. 25W/TN 70. It is approximately 4 miles along this congested four-lane highway to Carson Springs Road, on the left. There is no road sign for this turnoff, so watch carefully. The road cuts between an Exxon station and a restaurant; you’ll see a “Home of the Edgemont Rams” sign.

Major William Wilson built his tavern near this intersection in 1800. The Wilson Inn, operated as a stagecoach terminal, was one of the best-known landmarks in the area until it burned in 1951.

An amusing story tells about the gubernatorial race between James K. Polk and James C. “Lean Jimmy” Jones. Coincidentally, the two opponents stayed at the Wilson Inn on the same night during the campaign. Major and Mrs. Wilson were impressed with Polk’s gracious manner and mentioned it to Jones. They were particularly pleased that Polk felt so much at home that he did not mind sleeping on the floor on a pallet. Jones replied that he understood that when Polk thought he would encounter bedbugs, he always slept on the floor. This comment conveys the tone of Jones’s winning campaign against Polk.

Turn left onto Carson Springs Road. You will pass Edgemont Elementary School. It is 1.4 miles from the turnoff to where Splashaway Road comes in from the left. On the right is an old barn with a “Carson Valley Orchard” sign. In the early 1920s, Ben Hooper and his sons set out a large apple orchard here. In the 1930s, the orchard was purchased by Hooper’s nephew, James Stokely, who added fifteen hundred trees of the latest varieties, bringing the total to thirty-five hundred trees covering a hundred acres. During this time, the orchard produced twelve to fifteen thousand bushels of apples in a season.

Continue on Carson Springs Road for 2.5 miles, where you will see a sign announcing the entrance to the Camp Carson Baptist Assembly. The Carson family came to Cocke County in the early 1780s.

In the 1800s, C. T. Peterson and his wife, Mattie, operated the Peterson Hotel on this site. In her book, Over the Misty Blue Hills, Ruth O’Dell describes the springs that made the resort so popular: “One of the springs contains lithia; the other, sulphur. The strong mineral waters of these springs are particularly effective in driving malaria out of the body, a fact that brought early settlers to the springs during the summer seasons.”

In The French Broad, Wilma Dykeman describes the Peterson Hotel:

Its verandas were built out over the springs and embraced a great old beech tree where initials of courting couples could be carved in its bark during the break in a summer night’s dance or on a long rainy afternoon when the croquet grounds were deserted. . . . The eccentric behavior of the host [Mr. Peterson] who let his small energetic wife do most of the labor while he cared for an alleged heart condition, was only outweighed by the bounty of the table they provided. As at most of these hotels, service was family style, with platters of meat, bowls steaming with vegetables, cruets tart with seasoning, compotes brimming with honey and fruits, pitchers sweating with cool milk from the springhouse and pots boiling with coffee.

The coming of the automobile did not cause the predicted downfall of the resort. Instead, it allowed families to move here for the summer months while their fathers commuted from work in nearby towns. The resort boasted a park with croquet grounds, tennis courts, a swimming pool, and picnic facilities. In the 1930s, it suffered a period of decline, and many cottages fell into disrepair, but in the late 1940s, Carson Springs was rediscovered. In 1947, the Tennessee Baptist Convention accepted the site for Camp Carson. Construction began in 1949. Camp Carson now serves as a conference and retreat center for Baptists in East Tennessee.

A sign on the entrance to Camp Carson acknowledges that a gift from Ben W. Hooper and his family made the camp possible. Ben Hooper’s life, especially as told in his autobiography, The Unwanted Boy, reads like a Horatio Alger story. Hooper was born in Newport in 1870, the illegitimate son of a prominent physician, L. W. Hooper, and an Italian immigrant’s daughter, Sarah Wade. He was born Bennie Walter Wade. Sarah Wade eventually placed Bennie in an orphanage. When he was nine, Dr. Hooper and his wife adopted him.

In 1910, Ben Hooper defeated Alfred Taylor for the Republican nomination for governor. His original Democratic opponent withdrew, and Senator Robert L. Taylor was drafted as the nominee. In November, Hooper defeated Robert Taylor in what was Taylor’s first political loss. Hooper thus had the distinction of defeating both Taylor brothers in the same year. (For more information about Alfred and Robert Taylor, see The First Frontier Tour, pages 17–20.)

When Hooper ran for a second term, the question of his lineage was raised. Instead of denying the charge, Hooper answered, “The people of Tennessee are not so greatly concerned about where I came from as they are about where I am going and what I will do when I get there.” His statement proved accurate—they elected him to a second term. However, Hooper was defeated in his bid for a third term.

In 1921, President Warren Harding appointed him to the United States Railroad Labor Board. A story is told that shortly after his appointment, Hooper went alone into the convention of the Railroad Brotherhoods, which were meeting to announce a nationwide strike. His appeal to reason supposedly persuaded three of the four brotherhoods to call off the strike. Hooper came back to Carson Springs after his term on the railroad board and lived here until his death in 1957.

Turn around at Camp Carson and retrace your route to U.S. 25W/TN 70. You will see the entrance ramps for I-40 on the left. You can go east on I-40 to Asheville or west to Knoxville. Or if you prefer, you can go a short distance beyond the interstate overpass to U.S. 411 South; that road will take you to Sevierville, 20 miles away. Or you can continue on TN 363 to Dandridge. The Dandridge to Sevierville Tour follows this route, if you wish to combine these two tours.