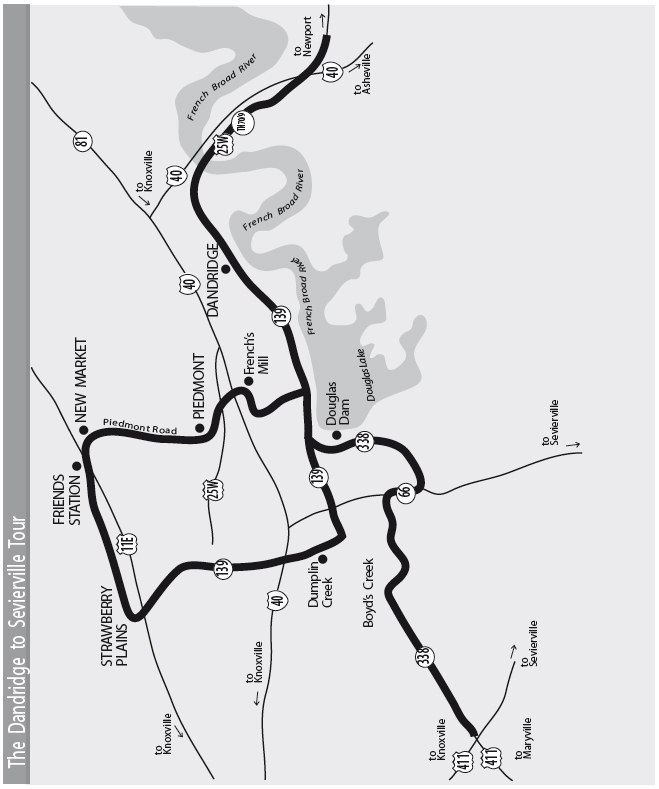

The Dandridge to Sevierville Tour

This tour begins near Newport, visits the original Stokely brothers homestead at Holly Oaks, continues to Dandridge and its historic district, and travels to the site of the Treaty of Dumplin Creek. It then heads to Strawberry Plains, New Market, French’s Mill, Douglas Dam, and Boyd’s Creek before ending outside Sevierville.

Total mileage: approximately 90 miles.

This tour begins at the I-40 exit approximately 4 miles west of Newport, where U.S. 411/U.S. 25W/TN 70/TN 9 intersects the interstate. Turn west, following U.S. 25W/TN 70/TN 9. A short distance beyond the interstate, U.S. 411 goes off to the left. Stay straight, heading toward Dandridge. It is 1.6 miles to the Jefferson County line.

It is 3.3 miles to the Taylor grocery store at Swannsylvania Road. Next to the store is a stone monument commemorating Pine Chapel Methodist Church, School, and Cemetery. All were erected around 1787—the church on this spot, the schoolhouse near the monument, and the cemetery 0.5 mile north. The monument claims these were “the first public institutions in the wilderness.”

Another 0.2 mile down U.S 25W, a road turns to the right and crosses the interstate, which you have been paralleling. Take that road. On the other side of the interstate, turn right. It is 0.2 mile to a road on the left. Turn onto this gravel road. After 0.1 mile, the road curves to the left. A gate is straight ahead. Holly Oaks, a large mansion with white columns, once overlooked the French Broad River at this site. The house burned to the ground in 1983. Only a few outbuildings remain today.

Holly Oaks, built in the early 1800s, consisted of ten eighteen-by-twenty-foot rooms with fourteen-foot ceilings and eighteen-inch brick walls. It had four halls, nine fireplaces, and two hand-carved apple-wood staircases. In the 1890s, this was the home of the remarkable Stokely family.

In 1890, John Stokely died at the age of forty-four, leaving his wife, Anna, with nine children. The first year after her husband’s death, Anna turned the operation of the farm over to Will, her seventeen-year-old son. Will ran the farm with the help of his siblings for one year. At that point, Anna sent Will off to college, and the next-eldest son, James, ran the farm. The next year, James went to college, and the next-oldest son operated the farm. When the fifth son was ready for college, Will returned to the farm.

By 1897, the Stokelys came up with the idea of canning some of their surplus crops. Together with a cousin and neighbor, Colonel Alfred Swann, they formed a partnership on January 1, 1898. The famous Stokely Brothers company, which would become a giant in the canning industry, was born. That first year, they canned four thousand cases of tomatoes, each can soldered by hand. They shipped the tomatoes to Knoxville and Chattanooga, using the French Broad River for transportation.

Each year after that, the brothers plowed most of their earnings back into the expansion and improvement of their company. From that initial six-week canning period for tomatoes, the company expanded by canning other produce, until the entire year was covered. As needs for better transportation arose, the company moved its headquarters to Newport in 1905 to be nearer the railroad.

In 1908, George Stokely, the youngest brother, took a job as a day laborer at the Van Camp plant in Indianapolis, Indiana, supposedly the finest in the country. The Stokelys implemented many of the Van Camp techniques observed by George. By 1933, they purchased Van Camp and moved their corporate headquarters to Indianapolis. But it all began with an industrious family and this farm along the French Broad River.

Retrace your route to U.S. 25W. It is 1.8 miles to the bridge across the French Broad. On the right just before the bridge are the remains of Swannburne. At the road just before the bridge, you can turn in for a better view of the estate. Actually, what remains is the Swannburne guesthouse, which should give you some idea of how elaborate the main home was before it burned in 1959.

This estate was the home of the Alfred Swann family. During the Civil War, Alfred joined the Confederate forces at the age of seventeen. His brother, Judge James Preston Swann, was a staunch Unionist and one of the leaders of East Tennessee’s attempt to secede from the state when it joined the Confederacy. On one occasion, Alfred was supposedly so angry with his brother that he jumped on his horse and headed for Dandridge to kill him. Thankfully, their mother, Sarah, ran Alfred down on her own horse and prevented any violence.

After the war, Alfred struggled because of his southern sympathies. He was often forced to hide in the fields when nightriders came looking for Confederate supporters. In 1866, he borrowed twenty-five dollars and began farming and trading. Alfred eventually owned three farms totaling thirty-two hundred acres on both sides of the French Broad.

Swannburne, the third home of the Swann family, was constructed in the 1920s. It was considered one of the showplaces of East Tennessee before it burned. Frances Burnett Swann was the mistress of the house for years. Her letter-writing efforts were influential in the building of the dike that saved the town of Dandridge when the TVA dammed the river to make Douglas Lake. Author Wilma Dykeman describes her this way:

[She] wasn’t quite five feet tall. Her bones were small as a bird’s, and her face was bright and inquiring and gentle. Sometimes she seemed so fleshless that it would have been no surprise if the wind had caught in one of her pink or lavender shawls and billowed her completely away to some never-never land of milk and honey. Delicate as the Dresden treasures that adorned her piano and library table and whatnot shelves, pale and perfect, Cousin Fanny was more than her appearance would admit. . . . She turned her pen and ink against the yards of concrete mixing in the hoppers. She wrote letters to Senators, and sent poems to the President’s wife. . . . Her letters and poems did not save the acres her Colonel Swann had accumulated and worked . . . but she did get, by Presidential decree, a levee around the little French Broad Baptist Church that had been part of her life and community life for generations.

James Stokely worked at Alfred Swann’s farm in 1897. In 1898, Alfred joined Anna Stokely in putting up $1,300 each, along with $650 each from James and John, Jr., to capitalize the Stokelys’ canning enterprise. The next year, the Stokelys bought out Swann’s share, adding a $500 profit.

Continue across the bridge over the French Broad. It is 3.4 miles to the Dandridge city limits. You are now traveling on Meeting Street. You will notice an interesting structure on the right as you enter town—an octagonal house at the corner of Meeting and Hill streets. The home was built about 1905. Three five-sided rooms are on each of the two floors. Each room has a fireplace feeding into a single chimney located in the center of the house.

Continue on Meeting Street to Church Street. The home on the corner on the left is the Nina Harris House. This large brick home has a beautifully restored two-story portico topped by a pediment; the portico sits right on Meeting Street. The home, built in 1848, has a frame addition constructed in 1926.

Turn left onto Church Street. On the left is the Samuel McCuistian House, built around 1850. The story is told that Davy Crockett traded his gun, “Old Betsy,” to Samuel McCuistian’s father so he would have the money to marry Polly Finley.

On the left farther up Church Street is the building that housed First Baptist Church in 1845. Later, when the Baptists relocated to a newer structure, they took this building’s original stained-glass windows with them.

As Church Street curves, you will see a park on the left. It is located next to the dike that saved the town from flooding. The dike is built of native stone, set in tons of solid earth. The parking area offers a good view of Douglas Lake.

Continue straight as Church Street turns into Main Street. On the left is the Hickman Tavern Coach House, which now houses the town hall. The coach house was built as an inn for stage travelers. Next door is the Hickman Tavern. Both of these structures were built in 1845. The Hickman Tavern now serves as the town’s visitor center.

Across the street is Shepard’s Inn, built in 1820. The Shadrack Inman family was known for its hospitality, and the family’s inn was noted for its good food, especially its country ham and fried chicken. The house became a tavern and boardinghouse at the close of the Civil War. The old register has the names of patrons from all fifty states and many foreign countries. It is even said that Joan Crawford once stayed at the inn.

Next to the inn is a Revolutionary War cemetery located at the original site of Hopewell Presbyterian Church. More information about the church is presented later in this tour.

The town of Dandridge began near this cemetery. In 1793, a commission was set up to find a site for a courthouse, a prison, and stocks. The commission recommended a location known as Henderson’s Lower Meeting House. This house was actually a log cabin near the Revolutionary War burying ground. The commissioners were swayed by the site’s location near the French Broad River, which would make transportation easy. A good spring was near the cemetery, as was excellent bottom land for farming. A church and cemetery were already on the site. Some say the commissioners were also impressed by the quality of the spirits made at the nearby spring.

Francis Dean donated forty acres of land, and a survey was made. The town was named for Martha Dandridge Custis Washington, the wife of President George Washington. It became the new county seat. The first jail was built in 1793, but it must not have been much. Records show that the sheriff appeared before the court and protested the condition of the jail soon after its construction.

On the corner of Main and Gay streets stands the Jefferson County Courthouse. This structure, built over a four-year period, was completed in 1845. The first floor houses four county offices and a large courtroom. On the second floor were four more offices and a large auditorium called Thespian Hall. According to an address delivered by Mrs. A. M. Felknor during the courthouse’s centennial celebration, “This hall was the scene of the famous Christmas balls, amateur theatricals, the closing exercises of the public school and many other interesting occasions.”

Today, the county courthouse also houses the Jefferson County Museum. The museum is not in a separate area but is spread throughout the hallways. The most popular item is the framed marriage license that David Crockett took out to marry Polly Finley on August 12, 1806.

A local legend claims that this was actually the second marriage license that Crockett filed at the courthouse. Supposedly, he had previously taken one out to marry Margaret Elder on October 21, 1805. The story says she eloped to Kentucky with another man. Apparently, Crockett’s broken heart healed pretty quickly.

Along with other artifacts, the museum has an old copper still confiscated years ago by the local sheriff, various Indian relics, the original 1793 survey plat for Dandridge, a collection of Philippine instruments of war donated by a former Manila chief of police when he retired to Dandridge, and a photograph of the famous New Market train wreck of 1904, which is discussed later in this tour.

Turn right at the courthouse onto Gay Street, heading away from the lake.

By now, you have probably noticed what a strange feeling the dike lends to this historic district. Looking from the courthouse, it appears that the town is located at the base of a hill; the face of the dike is a nice, grassy knoll. Visitors approaching from this side experience quite a shock when they crest the hill and find themselves literally on the shores of a vast lake, previously unseen.

On the courthouse lawn facing Gay Street is a water fountain placed in memory of Judge James Preston Swann by his grandchildren. In Mrs. Felknor’s centennial address, she reminded the audience of the legend attached to the well that feeds this fountain. The legend says anyone who drinks from the courthouse well will always return to Dandridge. Unfortunately, the water fountain is not always in working order.

Next to the courthouse stands the old jail. This is not the original jail that drew protests from the sheriff, but its replacement, built in 1845. The old portion is located in the rear of the building. The original iron-barred cells are located on the second floor of the old section.

Across the street is the Hynds House, with the original town spring in its backyard. The home was built around 1845 by Shadrack Inman as a wedding present for his daughter Elizabeth. After the siege of Knoxville during the Civil War, the two front rooms were turned into a Confederate hospital.

During the winter of 1863-64, Confederate general James Longstreet moved troops into East Tennessee in an effort to gain control of the area from Union general Ambrose Burnside. By mid-December, Burnside succeeded in repulsing the attack on Knoxville. During that winter, Longstreet billeted in Russellville (see The Jonesborough to Greeneville to Bulls Gap Tour, page 131). Union forces coming from the northwest through Dandridge were attacked at Hay’s Ferry, about 4 miles northeast of town. The Confederates drove the Union men back through Dandridge and on to New Market.

In January, the left wing under Longstreet surprised Union forces under General Gordon Granger in Dandridge. After a short skirmish, Longstreet drove the Yankees back to Knoxville. A good story tells about events in the Hynds House. General Granger stayed in the house the night before the battle, and in his haste to depart, he left behind a bottle of good Yankee brandy. After the Confederate victory, the woman living in the house invited the Confederates in for a victory celebration. Granger’s bottle of brandy was used for satirical toasts that evening.

Continue up Gay Street to Meeting Street and turn right. Turn left at the next corner onto Hopewell Street. On the right is Hopewell Presbyterian Church. This is the church organized in 1785 that originally met near the Revolutionary War burying ground. The present structure was built in 1872. Across the street from the church is Old Dandridge Cemetery.

Retrace your route to the courthouse by turning onto Meeting Street, then Gay Street. At the courthouse, turn right onto Main Street. On the right just past the courthouse is the Roper Tavern. Across the street is another Federal-style brick structure, the Roper House. Both were built in 1817 by Colonel John Roper. Because the Great Stage Road between Abingdon, Virginia, and Knoxville ran right through the middle of town, Dandridge was able to support several inns and taverns.

Next to the Roper House is the Thula Swann House.

Across the street in the next block of Main Street is the striking Rogers-Miller House, built in 1860. The elaborate Italianate porch was added at a later date.

Continue on West Main Street, which is also TN 139. The next street to the right is Cherokee Drive. Squirewood, the home built by Judge James Preston Swann in 1858, is located on the lot where Squirewood Way, West Meeting, and Cherokee Drive come together. However, the house is hidden by trees and hedges. All you can see from the street is a sign denoting its location.

This house contains an interesting room—a small, hidden room located upstairs under the center gable. The entrance to the room was through a closet. The Swanns hid a wounded Union soldier in this room until they could smuggle him around the Confederate lines.

Continue on TN 139, heading west. It is 5.1 miles to the Samuel McSpadden House, on the left. This home was built in 1804. The ground level is four bricks thick and the second floor three bricks thick. The attic contains portholes that could be used for defense during Indian attacks.

At the outbreak of the War of 1812, Samuel McSpadden operated a small powder mill near his home. He made a load of gunpowder for the American forces and loaded it on two flatboats that he sent down the French Broad, Tennessee, Ohio, and Mississippi rivers to New Orleans. The boats reached their destination just before the Battle of New Orleans. After that battle, Andrew Jackson gave McSpadden a voucher for forty thousand dollars in gold—supposedly, one dollar for each pound of powder. McSpadden had to take the voucher to Washington to cash it.

Continue on TN 139 for 2.7 miles. There, TN 338 turns left, heading toward Douglas Dam. The tour will return to this turnoff later. Stay straight on TN 139 for 3.1 miles to the intersection with TN 66. Continue across TN 66, still staying on TN 139. Take the right fork, following Douglas Dam Road.

About 1.1 miles after crossing TN 66, Douglas Dam Road makes a ninety-degree right turn. You are still on TN 139. You will cross Dumplin Creek 1.5 miles later.

On the left just past the creek is a historical marker for Henry’s Station. The marker is often blocked by trees, so you may miss it. If you reach the store in Kodak, you’ve gone too far. Major Hugh Henry, who lived at Henry’s Station, was one of the early settlers active in the Watauga Association and the State of Franklin. He also fought at Kings Mountain and Boyd’s Creek, which will be covered later in this tour.

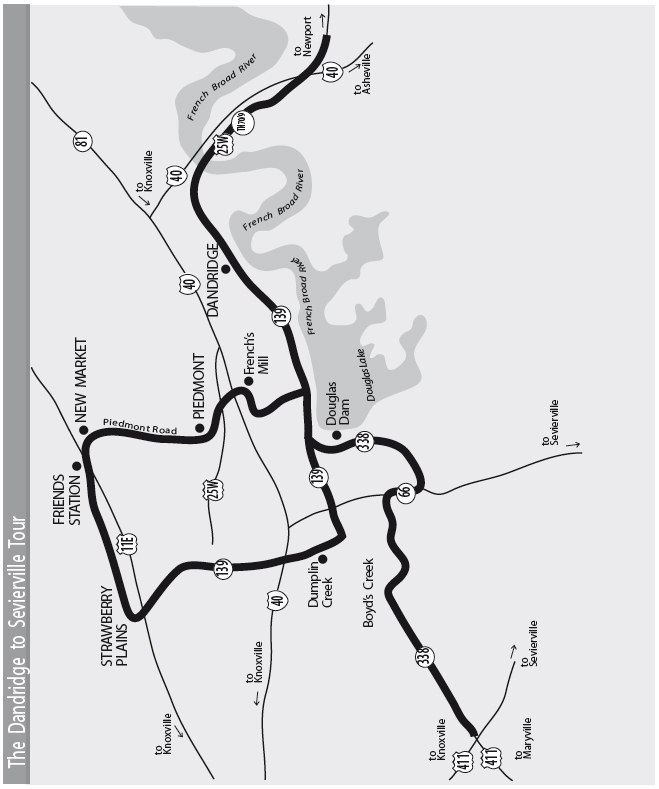

You will also see the old Kodak mill and a gravel road off to the left. The road sign indicates that this gravel road is Treaty Road. Turn left onto Treaty Road, passing beside the mill. Follow the gravel road for 0.3 mile as it curves past the white house on the left and goes to the top of the hill. Next to the road in front of an abandoned house is a huge stone with a historical marker for the Treaty of Dumplin Creek bolted to it. This treaty was the only one made by the State of Franklin.

On June 10, 1785, John Sevier and several other men representing the State of Franklin met with Ancoo of Chota, Abraham of Chilhowee, the Sturgeon of Tallassee, the Bard of the Valley Towns, and thirty other Cherokees to sign the Treaty of Dumplin Creek. This treaty opened a large area south of the French Broad and Holston rivers for white settlement. The newly opened territory included what are now the counties of Blount, Hamblen, Jefferson, Knox, and Sevier.

A good tale survives about the naming of Dumplin Creek. It says that during one of the Indian campaigns, some soldiers camped on the creek were cooking their supper of cornmeal dumplings in a big iron pot. When one of the men accidentally knocked the pot into the creek, another yelled, “There go our dumplings, down the creek!” Hence the name.

Return to TN 139 and turn left. It is 3.5 miles to an intersection with U.S. 25W/TN 70. Continue straight on TN 139, also called Douglas Dam Road at this point. Go 1 mile to a stop sign and turn left. You are now on Old Dandridge Pike, though no road signs are located at the stop. This is still TN 139 West, but you won’t see a marker for a while. It is 3.5 miles to an intersection with U.S. 11E. Cross U.S. 11E and go one block to a stop sign. Turn left to enter Strawberry Plains.

In History of the Lost State of Franklin, Samuel Cole Williams discusses the origin of the name Strawberry Plains. When land was cleared for cultivation, the burning occasionally got out of hand and scorched a large area, which settlers called a “barren.” While exploring this region, botanist André Michaux described such a barren north of the Holston River: “Wild strawberry vines matted the earth and in season the berries covered the ground as with a red cloth.”

In her book, Bent Twigs in Jefferson County, Jean Patterson Bible tells an anecdote about the town’s name. In the early 1900s, the porters and flagmen on the passenger trains that went through town shortened the name to Straw Plains. Soon, the railway station and even the post office were using the shortened name. In 1914, the general manager of the Southern Railroad passed through in his private car. While visiting a local family, he was urged to change the name back to the original. He agreed, and everyone eventually began calling it Strawberry Plains again.

The important railroad bridge at Strawberry Plains lent this area strategic value during the Civil War. The Tennessee and Virginia Railroad ran all the way up to Lynchburg, Virginia, passing the vital salt mines at Saltville on the way. This was an important supply link to the lower Confederacy. When the war broke out, a guard was placed at the bridge. By November 1861, the Confederates felt it was safe to leave the bridge under the watch of one person.

On November 8, James Keelan was the only person on duty at the bridge. Shortly after midnight, forty Union men came through William Stringfield’s nearby farm. A wonderful pamphlet was published in 1862 describing the night’s events and the role of “the immortal hero James Keelan.” According to the pamphlet’s author, Radford Gatlin, the “desperadoes” were armed with “repeaters, bowie-knives, torch-pine, and loco-matches.” Their intent was obvious. Gatlin goes on, “The moon had disappeared; all was silent about the bridge; the people of Strawberry Plains were profoundly sleeping, darkness shrouded every object. But the immortal Keelan was awake; the lion was aroused in his lair; the hero rose up, and stood in his box.”

Gatlin continues in this vein, describing the incredible fight in which the badly wounded Keelan continued to fight an overwhelming force:

When the demons were fairly gone, the conqueror, no one coming to his relief, his left hand cut off, his right arm rendered helpless by a deep wound from a bowie-knife and a ball, shot by the retreating incendiaries, his blood fast running, his body a gore, by one leap came to the ground, from the shoulder of the pillar, and proceeded near three hundred yards . . . to the house of Mr. William Elmore, dark as was the night; but the fire of the hero’s eye was not quenched, nor was the never-dying courage of his soul, in the smallest degree, abated.

Thanks to James Keelan, the bridge remained intact and continued to serve the Confederate cause.

By 1862, the Confederacy was all too aware of the strategic importance of the Strawberry Plains bridge. William Thomas’s Legion, comprised primarily of Cherokee warriors, was stationed here to protect the bridge in May 1862.

From these headquarters, the legion moved north that September to protect the railroads in the gaps of the Cumberland Mountains from Union invasion. On September 13, the legion was ambushed at Baptist Gap. Fighting continued until September 15, when William S. Terrell ordered Second Lieutenant Astoogatogeh, the grandson of the Cherokee chief Junaluska, to charge the Yankees. In the ensuing attack, Astoogatogeh was killed. At the loss of their popular leader, the Cherokees rushed forward and, before they could be stopped, scalped several Yankee dead and wounded.

Will Thomas had always worked to overcome the white man’s stereotype of the savage Indian. It was later reported that the scalps were returned to the Union forces, to be buried with the soldiers. Although Daniel Ellis and others fueled the propaganda flames about “Thomas’s Rebel Indians murdering Union men,” supporters argued that the Cherokees took scalps only on this one occasion.

Soon after the encounter at Baptist Gap, the legion was reassigned, and General Alfred “Mudwall” Jackson took command. (For more information about Thomas’s Legion, see The Jonesborough to Greeneville to Bulls Gap Tour, pages 109–10.)

Strawberry Plains Presbyterian Church is located on the right as you enter town. Behind the church is the Biblical Garden, dedicated in 1969 largely through the efforts of Mrs. William Wood, Sr. Throughout the garden are statues depicting various scenes from the Old and New testaments. Symbolic landscaping complements the statues and fountains. The garden even has a miniature Noah’s Ark resting atop a pile of river rocks representing Mount Ararat.

After viewing the garden, turn around and retrace your route; the road becomes Andrew Johnson Highway, now paralleling U.S. 11E. After 5.7 miles, you will see New Market Elementary School on the right. It is 0.6 mile past the school to Lowry Loop Road. Continue straight; the next left turn is where Lowery Loop Road comes out. Turn right onto Friends Station Road. Just after turning onto this short road, you will see Friends Station Meeting House on the right. This church has also been known as Lost Creek Meeting House.

In 1784, John Mills and his family became some of the first Quakers to settle in this area. By 1797, a meeting was officially established. Before any Quakers could transfer their membership, they had to assure the meeting that the land on which they were living had been purchased from the Indian owners.

A considerable number of Quakers moved into the area. By 1815, they organized the Tennessee Society for Promoting the Manumission of Slaves at this old meeting house. Many of these settlers eventually left the area because of their objection to the institution of slavery.

The church hosted an interesting occasion in 1928. When President Herbert Hoover opened his reelection campaign in East Tennessee, he started in Elizabethton. On his way to Knoxville, Hoover, a Quaker, had the train stop so he could go in the meeting house and say a prayer.

Just beyond Friends Station Meeting House, the road intersects U.S. 11E. Turn left onto U.S. 11E, a four-lane highway. After traveling a short distance, turn right onto Old Andrew Johnson Highway; you will be paralleling the four-lane. It is 0.4 mile to a stop sign. Cross this intersection and continue paralleling the four-lane. Lost Creek Golf Club will be on the right. It is 0.7 mile to New Market.

In 1819, James Tucker started a house of entertainment on the Great Stage Road. The village that developed was known as Tuckertown until a general store opened that sold its wares for anything that was available for barter. People in the area started talking about “the new market,” and the name stuck. The first religious service in this area was held at Tucker’s Publick House in 1819. By September 10, 1826, New Market Presbyterian Church was organized, taking many of its members from Hopewell Presbyterian Church in Dandridge.

In 1865, one of New Market’s most famous residents moved to town. In 1854, Frances Hodgson’s father had died in England, leaving his wife with four young children and another on the way. Mrs. Hodgson’s brother, who lived in Knoxville, persuaded her to bring her family to America. By 1865, they settled in a log cabin in New Market. For the next few years, Frances grew up in this little village. By 1868, she published her first short story in Godey’s Lady’s Book, and her literary career was launched; the story is told that she sold blackberries to make the money she sent with her manuscript to make sure it would be returned to her if rejected. In 1873, she married Swan Burnett, a neighbor in New Market. In 1886, her book Little Lord Fauntleroy made her a wealthy woman.

New Market’s other claim to fame came on September 24, 1904, when the westbound and eastbound Southern Railroad trains met in a frightful head-on collision near town. Early newspaper reports said that 54 people died and 120 were injured. The Associated Press account read, “Both engines and the major portions of both trains were demolished, and why the orders were disregarded or misinterpreted probably will never be known as the engineers of the two trains were crushed, their bodies remaining for hours under the wreckage of the monster locomotives, which but a short time before had leaped forward at the touch of their strong hands upon the throttle.”

Some haunting stories about the wreck’s survivors were reported in the newspapers. One report read,

One of those injured tells a touching story of a little child about three years of age, who was crying for its mother. A lady who was rendering as much assistance as she could, took the injured infant whose mother was dead in the debris. She tried to pacify it as well as she could, but it continued to cry for its mother. The woman then asked the child if it would go to sleep if she sang it a song. It said it would, and the woman sang a hymn softly. The child ceased to cry and it was laid gently down on a pillow. When the physicians came by they found the infant asleep, but asleep in death.

Another report read, “A woman searching for her lost husband found a severed hand which she claimed was that of her husband because of the fact that the ring on one of his fingers was his wedding ring, matching the one she wore.”

In 1906, one of the survivors, R. H. Brooks, composed a song about the wreck. It was published in 1915. Soon after that, George Reneau, known as “the Blind Musician of the Smoky Mountains,” recorded the song.

The devastation was so great that the wreck has remained a part of local folklore to this day.

As you enter New Market, you will see a historical marker for Frances Hodgson Burnett on the right. The old log cabin where the Hodgsons lived is now weatherboarded. It is part of the house located where the marker stands.

Next to the Hodgson home is the wellhouse for Houston Mineral Water. In April 1931, William Avery Houston, who ran a general store and served as the telegraph operator in New Market, was seriously ill with kidney disease. His health was so bad that he prepared his will. One night, he had a dream telling him to drill a well on the site where the stone wellhouse stands today. Other wells in the area were generally only 18 to 30 feet deep, but Houston kept digging for 252 feet until he struck water. He drank the water and continued to do so for several days. His disease was cured, and he never had a recurrence. A few years later, he began to bottle and distribute the water.

The wellhouse was built in 1933. Inside is a water fountain for sampling. Local people constantly come and go, filling up their plastic jugs with the water and leaving honor-system donations to help defray the expenses of the electric pump. One gallon of water costs twenty-five cents. The wellhouse remains open from 8 a.m. to 8 p.m. daily—and the water tastes great.

A few yards farther and across the street stands New Market Presbyterian Church, built in 1847. The bell that once hung in the belfry was made in Philadelphia, then shipped to Charleston, South Carolina, and hauled to New Market in a schooner wagon pulled by six horses. It is said that the bell could be heard all the way to Dandridge.

Just past the church, turn right onto Piedmont Road. You will travel through rolling farmland with the mountains off in the distance. After 5.5 miles, you will come to an intersection on a curve where you must make a decision to turn. Turn left here. It is 0.8 mile to the Piedmont Store, on your left. Turn right at the store. After 0.2 mile, the road intersects U.S. 25W/TN 70, which locals also call the Old Asheville Highway. Turn left on this highway. After 0.7 mile, turn right onto French Mill Road.

It is 1.1 miles to French’s Mill, on the left. When Kenneth French purchased this mill, he found the year 1883 carved on one of the inside steps. This well-preserved mill is easily photographed from the road.

Just past the mill, the road forks. Turn right onto Harbin Road as it heads up the hill. After a short distance, you will cross over I-40. No road signs are in this area; simply take the right fork whenever you have to make a decision.

After approximately 2 miles, the road ends. Turn left and go 0.2 mile to Deep Springs Road. You will see an interstate entrance/exit on your right. Turn left. It is 1.1 miles to Deep Springs Baptist Church, on the left. As you crest a hill after 1.3 miles, you will have a good view of Douglas Lake.

Straight ahead is the intersection with TN 139. Turn right. The McSpadden House is on the left after 0.1 mile. It is 2 miles past the McSpadden House to a junction with TN 338. This time, turn left, or south, onto TN 338, heading toward Douglas Dam.

It is 0.8 mile to a road to the left that leads to the dam and powerhouse. A visitor center is located there as well. You will have an excellent view of the lake and the nearby Smoky Mountains.

The TVA proposed a dam on the lower French Broad River before World War II. The proposed dam was to flood fifteen thousand acres of the best river-bottom land in East Tennessee, not to mention eighteen thousand additional acres of less productive land. Since flood control did not seem a sufficient reason for approving a project that would destroy so much farmland, it was put on hold. But once Pearl Harbor was attacked, the mentality changed. As Wilma Dykeman phrases it, “Power for victory entered the picture.”

President Franklin Roosevelt authorized the dam’s construction on January 30, 1942. Construction began on February 2. On February 19 of the following year, the dam was closed. It is difficult to analyze whether or not building the dam was the right thing to do. However, estimates suggest that the dam saved the city of Chattanooga alone some twenty-three million dollars during the floods of 1946 and 1948.

It is 0.8 mile farther on TN 338 to a turnoff for the scenic campground located along the water behind the dam’s spillway. Continue on TN 338 for 5 miles until it intersects TN 66. Turn right onto the four-lane TN 66. Travel 1.6 miles on this congested strip to where TN 338 turns left again. This part of TN 338 is also called Boyd’s Creek Road.

It is 5.5 miles to Rocky Springs Church, on the right, then 0.4 mile farther to the two-story brick home on the left known as Wheatlands. Built in 1825, Wheatlands is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

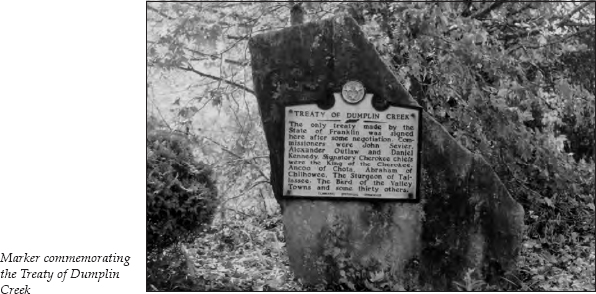

Travel 0.7 mile farther to the Boyd’s Creek Monument, on the right. According to Wilma Dykeman, contemporary historians believe that the fight waged here was the best-fought battle of the border wars between the frontiersmen and the Indians. Of course, there’s not much competition when you consider the disorganized state of most of these battles.

In October 1780, the Overmountain Men marched to the Battle of Kings Mountain (see The First Frontier Tour, pages 7–8). Upon their return, they learned that the Cherokees, who were British allies, had been attacking all along the frontier during their absence. John Sevier rounded up two hundred to three hundred men and marched south, following the Great Indian War Path.

On their second night out, Sevier’s scouts ran into an Indian war party. The scouts fired and retreated. Sevier prepared for an attack. The next day, the frontiersmen marched past a deserted camp and learned they were pursuing a large war party. They crossed the French Broad and made camp. The following morning, scouts reported an Indian camp nearby with ashes still warm in the abandoned fires.

Sevier arranged his men in a half-moon near the mouth of Boyd’s Creek. He ordered his advance guard to engage the Indians and then fake a retreat. It worked. The Indians fell right into Sevier’s trap. Hemmed in on three sides, they did not seek to fight, but only to escape.

After the battle, Sevier retired to Big Island—later called Sevier’s Island—in the French Broad. He camped there until seven hundred reinforcements joined him. Then they swept down on the Overhill Towns of the Cherokees. (For more information about this campaign, see The Maryville Tour, pages 273–75.)

This was the beginning of a long series of bloody forays against the Cherokees that resulted in new treaties ceding more land to the white settlers. Time after time, the latest treaty was broken, hostilities occurred, and a new treaty was signed, only to be broken again when settlers moved beyond the established treaty boundaries.

Next door to the Boyd’s Creek Monument is the house built by John Chandler in 1825. Chandler settled in this valley around 1791.

Continue past Boyd’s Creek for 5.5 miles to the junction with U.S. 441. The tour ends here. You can either turn left on U.S. 441 to reach Sevierville, turn right on U.S. 441 to travel to Knoxville, or continue straight on U.S. 411 to journey to Maryville.