‘THE LAND BEYOND THE SEA’: LATIN CHRISTIAN LORDSHIP IN THE LEVANT, 1099–1187

Looking back a century later, the Mosul historian Ibn al-Athir described the appearance of western reinforcements in the Levant in 1104: ‘There arrived . . . from the lands of the Franks ships carrying merchants, troops and pilgrims and others.’ He used the same formula in an account of the westerners’ attack on Damascus in 1129: ‘They all gathered, the king of Jerusalem, lord of Antioch, lord of Tripoli and other Frankish [rulers] and their counts and also those who had come by sea for trade or for pilgrimage.’1 Military strength, commercial opportunity, religious magnetism, sea power and links with the west established the Franks (as the settlers were universally if ethnically misleadingly known; ifranj in Arabic), in their settlements in Syria and Palestine that came to be called Outremer, the land beyond the sea.

Settlement

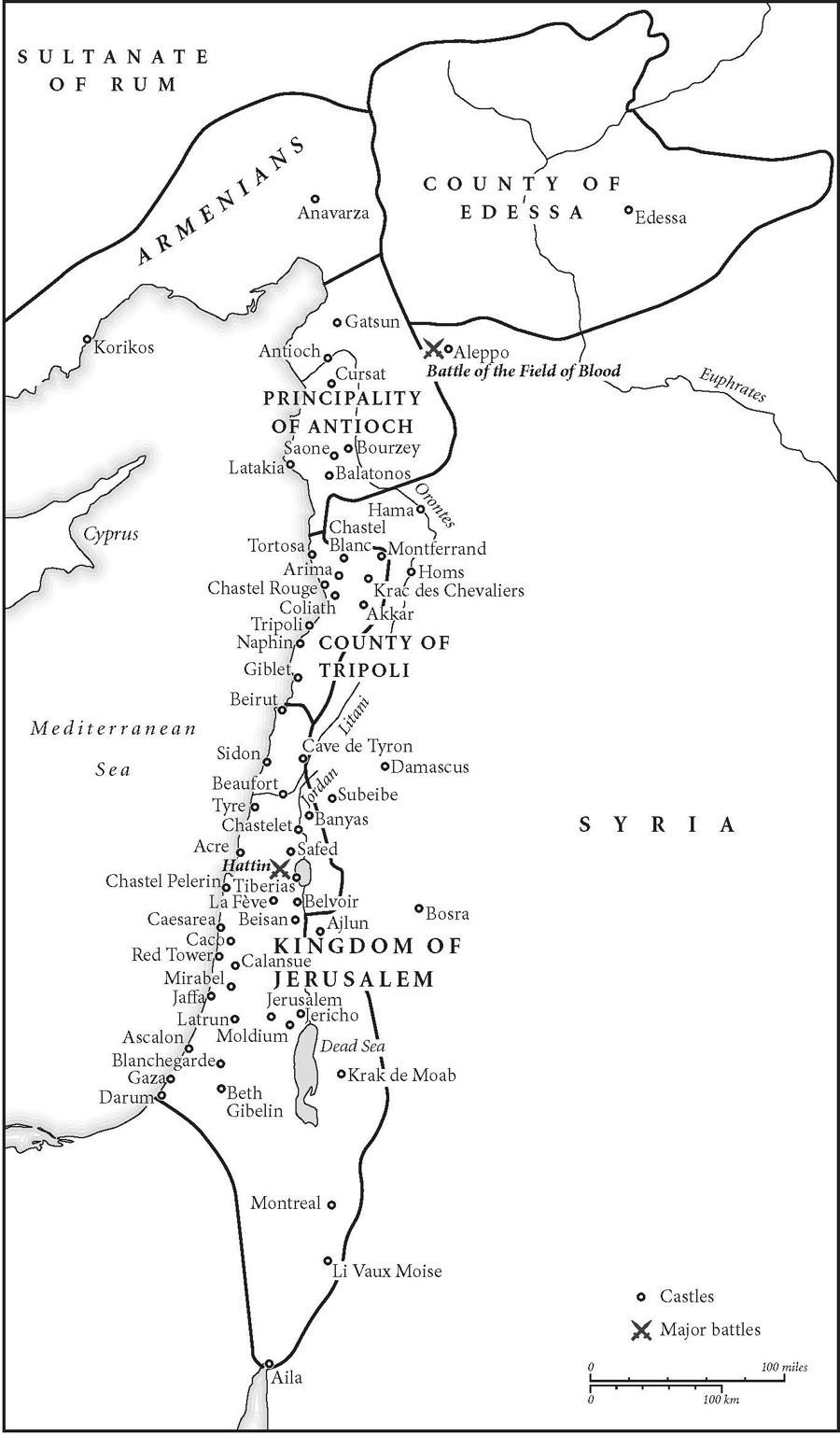

The lands occupied by the western invaders were never very extensive. At their greatest extent, they stretched from Cilician Armenia and the Upper Euphrates valley in the north to the Negev and Gulf of Aqaba in the south, a distance of some 600 miles. Except for the isolated enclave of Edessa beyond the Euphrates to the east, the conquests were physically limited by chains of mountain ranges running north/south, with only a few rivers (such as the Orontes and Litani) and natural gaps (as at Homs, the Biqa valley and the road from Acre through Galilee to Damascus) allowing access from the coast to the interior. Beyond the mountains to the east, agrarian plateaux gave way to the fertile valleys of the Jazira in the north and arid scrub leading to desert in the south. Cutting north/south through this region, the great rift valley of the Jordan led to the Dead Sea. The narrow fertile coastal plain, interrupted by hills in the Lebanon and around Haifa, and flanked in Palestine by the dry Judean hill country, opened out in the south towards the intractable Negev desert between Palestine and Egypt. Failure to annex the great cities of the Syrian interior, Aleppo and Damascus, or extend control to the Nile valley, let alone challenge the Seljuks in Iraq, left the invaders without the major economic and political centres of the region. They were restricted to an area of immense cultural significance for all three Abrahamic faiths, but of patchy economic productivity, embracing fertile valleys and constricted plains, arid hillsides, semi-desert and parched wilderness, an inconveniently configured territory not much larger than modern England or a medium-sized state of the USA, such as Alabama.

Control even of this modest expanse proved strenuous to conquer and maintain. It took the Franks half a century to establish complete command over the coast. In the north, the city state of Antioch failed to secure stable frontiers either in Cilicia or towards Aleppo, which remained conspicuously beyond its grasp. While an important strategic buffer for the rest of northern Outremer, the county of Edessa proved ephemeral, lacking wealth, administration and settlement, reliant on constant military activity to manipulate local rivalries between Muslim and Armenian lordships. Its demolition between 1144 and 1151 proved impossible to resist. In the south, the expansion of the kingdom of Jerusalem to cover, at its height, not only the Biblical Holy Land but large tracts of land beyond the Jordan and Dead Sea and in the desert towards the Red Sea, never secured it from invasion from Syria or Egypt. The absence of permanent regional allies rendered Outremer vulnerable if its neighbours united against it, as happened in the 1180s, a fragility seemingly confirmed when it was all but annihilated in 1187–8 by the sultan of Egypt and Syria, Salah al-Din Yusuf ibn-Ayyub (i.e. ‘the Righteousness of the Faith Joseph son of Job’), known to westerners then and now as Saladin (1137/8–93).

Hindsight imposes a teleological pattern of transience and decay. The obstacles to permanent settlement were formidable: the alien, hostile physical, cultural and political environment; the failure to reach the natural frontiers of mountains to the north and desert to the south or to annex major cities of the interior; the untamed and untapped economic, demographic and strategic power of Egypt. Limited settlement by westerners disguised the inadequacy of material resources within the Frankish territories necessary to support the numbers of immigrants that might have secured a more lasting presence. As it was, the Franks were too few to dominate and too many to integrate. Except in politics and superficial domestic manners, unlike other foreign invaders of the region, the Franks could not conform to indigenous linguistic and religious culture: the Frankish kings of Jerusalem revealingly called themselves ‘king of the Latins’, namely the Franks, those who followed the Latin rites of the western Catholic Church. Arabic presented a barrier to accommodation even where, as with Syrian and Palestinian Christians, religion did not. The Franks lacked the resources to compete numerically with the continuing influx of Islamicised steppe nomads into the Near East or prevent the rise of Turkish and Kurdish warlords to regional political domination. Demography denied Outremer’s survival. However, the impression of a doomed venture obscures the social reality of the Frankish experience. By the 1180s, Outremer had become home to three or four generations of Franks, tens of thousands of people who, however conscious of their special status in ethnicity, language, law and religion, no longer could see themselves or, except in Muslim polemic, be regarded as intruders. For them, Outremer, as its greatest twelfth-century spokesman, the Jerusalem-born scholar, prelate, royal servant and chronicler William, archbishop of Tyre (c. 1130–86), insisted, was their patria, for the love of which ‘if the needs of the time demand, a man of loyal instincts is bound to lay down his life’.2

35. Farming in the Nile valley, the economic dynamo of the eastern Mediterranean.

WILLIAM OF TYRE

William, archbishop of Tyre, intellectual, tutor, administrator, diplomat and pre-eminent historian of the Latin settlements in twelfth-century Syria and Palestine, was born c. 1130, probably in Jerusalem, into a local Frankish non-noble burgess family. After his early education most likely at the school run by the canons of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, c. 1146–65 William received first-class academic training in the liberal arts, theology and civil law at Paris, Orléans and Bologna. On his return to the kingdom of Jerusalem in 1165, he soon garnered elite church preferment, first at Acre then as archdeacon of Tyre. Entering royal service as a diplomat to Byzantium (1168) and Rome (1169–70), in 1170 he was appointed tutor to King Amalric’s son and heir the future Baldwin IV. In his own account, it was William who first discovered Baldwin’s leprosy; tutor and pupil seemed to have continued on good terms into the 1180s. Through the good offices of the regent Raymond III of Tripoli, with whom William forged a lasting political affinity, he became the new King Baldwin’s chancellor in 1174 and in 1175 archbishop of Tyre, the second-ranking cleric in the kingdom. Although his active political and secular administrative roles are unclear, his duties as chancellor (1174–84/5) frequently if not permanently delegated and his patron Raymond regularly out of favour, William’s civil -law skills were used in diplomacy. He led a delegation to the Third Lateran Council (1178–9) and negotiated at home and abroad with Byzantium (1168, 1177, 1179–80). As archbishop of Tyre (1175–84/6), he proved himself a vigilant diocesan.

36. William of Tyre.

However, his most distinctive activities were literary. He built up the library at Tyre and wrote an account of the decrees of the Third Lateran Council as well as two major historical works: the Gesta orientalium principum, a history of the Muslim world from the Prophet to the 1180s; and the Historia Ierosolymitana (or Chronicon), a detailed account of the First Crusade and the Latin east, beginning with the Byzantine Emperor Heraclius’s return of the True Cross to Jerusalem (629/30) and ending with events recorded contemporaneously in 1184. Only the Historia survives, although the Gesta had a limited circulation in western Europe in the thirteenth century. William had begun collecting historical material soon after returning to Palestine in the 1160s, attracting early support from King Amalric. The Historia, composed between 1170 and 1184, was explicitly conceived as an account of the foundation and fortunes of William’s patria, although after his attendance at the Lateran Council in 1178–9 he began to revise and recast the work more as an apologia for the Latins of Outremer and, increasingly, a description of their growing travails in the face of resurgent Muslim neighbours, his analysis of the material rise of Saladin remaining a classic. While too cumbersome (almost 1,000 pages in the modern edition)3 for simple propaganda for a new crusade, the Historia invites understanding and sympathy for the plight of the heirs of the First Crusaders, while not concealing William’s partisan reflections on the immediate, and to him all too depressing, politics of his own time. It was later alleged that William had been disappointed not to have been elevated to the Patriarchate of Jerusalem in 1180 and had later fallen victim to the malice of the successful candidate, Patriarch Heraclius. Alternatively, William’s vivid depictions of Jerusalemite factional rivalries may have been those of a close observer not political player, even if the gloom that pervades the later passages of the book at times conveys an almost existential despair. William’s Historia stands as a monument to its author’s erudition, human sympathy and literary mastery in its coherent expression of themes, clarity of style, breadth of learning, control of detail and range of material. Deploying extensive scriptural, classical and Christian allusions, motifs and models, William, who died before October 1186, combines sustained analytical synthesis, and vivid delineations of people, character and events, with an engaging individual voice. Extensively copied, continued and translated over the following centuries, it stands as one of the greatest historical works of the Middle Ages.

While it is impossible to calculate the raw numbers of Frankish inhabitants or their proportion in the total population, their presence in cities and certain rural areas was significant. By the 1180s, the Frankish community in the kingdom of Jerusalem possibly generated an armed force of around 20,000 including lightly armed auxiliaries known as Turcopoles, comprising local Syrians and some Franks.4 Unlike the nomadic Turks, the Franks were accustomed to sedentary agricultural society, as lords, farmers and peasants, and to cities, as merchants, shopkeepers and artisans. Many immigrants were already familiar with a Mediterranean economy of cereals, olives and wine. The chief agricultural novelty most settlers would have encountered was sugar cane, only grown in the west by 1100 in parts of Sicily and Spain, yet integral to Outremer’s prosperity, with centres of production at Acre, Sidon and Tyre, Galilee and the Jordan valley.5 Rural settlement was patchy, clustered in areas of existing Syrian Christian occupation in southern Samaria, north of Jerusalem; western Galilee in the hinterland of Acre; and on the royal demesne around Nablus. Rulers, landlords and estate-owning religious corporations actively encouraged rural settlers in a deliberate policy of rural colonisation. As Franks, they were ipso facto free from the sort of restrictive or servile tenancy burdens familiar in the west. While in Antioch and Tripoli, Frankish settlement was largely restricted to towns and cities, and in parts of the kingdom of Jerusalem local peasant occupation could be significant. By the 1160s, the new Frankish village of al-Bira (Magna Mahomeria) near Jerusalem may have housed between 500 and 600, with a new settlement, Qubeida (Parva Mahomeria), being established nearby in mid-century, dedicated to producing olive oil. In 1170, al-Bira sent at least sixty-five troops to the defence of Gaza. As the villages’ names suggest, the Franks probably replaced Muslim inhabitants, indicating some process of ethnic cleansing to match that in the city of Jerusalem.6

Al-Bira and Qubeida were two of a number of planned villages. Lists of settlers suggest that the bulk of rural immigrants came from other Mediterranean regions, especially southern France, but also northern Italy and Spain. Others came from Burgundy and the Ile de France. Although it may reflect more plentiful surviving evidence, settlers in cities appeared to come from a slightly wider international background, including most parts of France as well as Italy and Spain. Mention too is made of Scots, English, Germans, Bohemians, Bulgars and Hungarians.7 Some towns and cities had been evacuated during the First Crusade and those conquered before 1110 had their inhabitants massacred or expelled. Thereafter, most contained mixed populations of Syrians and Franks. In cities many of the immigrants were clerics or associated with ecclesiastical institutions. The cities also harboured transient populations of visiting pilgrims, warriors, clergy and traders. The new Orientals (nunc orientales), as they were optimistically described by one of their number,8 if non-noble, pursued a wide range of skilled and unskilled occupations: catering to elites as servants, coiners, goldsmiths and furriers; skilled artisans; carpenters, masons, cobblers, blacksmiths, butchers, bakers, grain and wine growers, and traders; humbler shopkeepers, gardeners, drovers and herdsmen. In ports such as Acre, Tripoli and Tyre, Italians from maritime communes enjoyed privileged quarters as did members of religious orders, monks and canons, and of the Military Orders drawn from across Europe. Rural landscapes were marked with castles, estate towers, manor houses, new villages, mills, oil-presses, vineyards and pigs. Urban centres were reconfigured to suit Frankish social, commercial and religious requirements, what the German pilgrim John of Würzburg called in the late 1160s ‘new Holy Places, newly built’.9 The motives of emigrants from Europe are hidden, but, like the Mormons trekking westwards in nineteenth-century North America, incentives of piety and material opportunity plausibly combined. Some arrived with succeeding waves of crusade armies, but others, perhaps a majority, such as Constantine, a cobbler from Châlons, or John, a Vendôme mason, did not.10

37. Map of thirteenth-century Acre, showing the different Pisan, Venetian and Genoese quarters.

38. Frankish-built entrance to the Cenacle, the supposed Upper Room of the Last Supper story, Mount Sion, Jerusalem.

Creating Outremer

The early years saw precarious garrisons become distinct principalities. In Antioch, Bohemund’s military entourage proved sufficiently large and robust to maintain control even after their leader was captured by Danishmend Turks in August 1100. In Jerusalem, Godfrey of Bouillon’s small garrison force of perhaps 300 knights and 2,000 infantry, having secured the Holy City, a handful of Judean towns and villages, and a narrow strip of land leading down to the coast and the port of Jaffa, began to assert Frankish power in the coastal plain, Judea and Galilee. A generation of Turkish-Egyptian contest had left no united local opposition to Frankish expansion. At Antioch and Edessa, the unstable political mosaic of the region offered the Franks greater opportunities for local alliances, as did the larger proportion of non-Muslims in the population. Taking advantage of a society where small committed companies of well-trained, heavily armed troops could impose themselves on people and resources across wide swathes of territory, Frankish rule in Palestine began more as a form of banditry and coercion than administration. Local resistance was feeble, as Muslim elites fled as refugees or were killed in the massacres that attended early Frankish conquests of the coastal cities. The major threats to Frankish success came from outside: Iraq, the Jazira and Egypt.

5. Political map of Outremer in the twelfth century.

Systems of governing the conquests emerged from events not prior planning. In Jerusalem, in 1100 the new papal legate Archbishop Daimbert of Pisa unsuccessfully sought to install a theocracy, perhaps in line with Urban’s liberation policy.11 Material constraints imposed extemporised solutions. Each of the Latin principalities established after the First Crusade, while never entirely obliterating existing or traditional regional political structures, was perforce self-created. Antioch sought, not always successfully, an independent path between repeated reliance on the Franks of Jerusalem and the occasionally enforced claims of the Byzantine emperor. The county of Edessa existed alternately as a coalition with local Armenian interests and an adjunct to Antioch. The status of the county of Tripoli emerged only slowly as a semi-autonomous lordship in the orbit first of Jerusalem and then, from the 1180s, of Antioch. Jerusalem, a self-proclaimed kingdom after 1100, exerted some de facto responsibility over the other Frankish areas but its own status remained equivocal, from grudging acceptance by the papal legate in 1100 to prudentially recognising some general Byzantine overlordship in the 1150s and 1170s. Collapse of the male line of the Jerusalem royal dynasty in the 1180s even prompted the idea of asking the rulers of western Europe to arbitrate in choosing a ruler. However, Outremer’s claims to legitimacy lay elsewhere. While each principality was the result of military and political expediency, ideologically, their legitimacy sprang from the pious heroism of the First Crusaders and the explicit favour of God, the autonomous justification presented by William of Tyre in his great narrative account of Outremer written in the 1180s.12

In Jerusalem, the immediate strategy secured access to the coast and pacified the interior. In the first decade and a half after 1099, Fatimid attacks from the south and those from the north-east sponsored by the Seljuks in Baghdad were undermined by Seljuk and Fatimid rivalry. This did not remove a lasting asymmetry in the Franks’ predicament. Outnumbered and culturally alien, the Jerusalem Franks were always only one major military defeat away from a potentially fatal crisis while their opponents could always regroup, sustained respectively by the resources of the Syrian interior, the Jazira, Iraq, Egypt and the steppes. Nonetheless, Baldwin of Edessa’s reign in Jerusalem after the death of his brother Godfrey in 1100 as King Baldwin I (1100–18), during which he extended Frankish control east across the Jordan, southwards towards Egypt, and along the Palestinian coast, demonstrated how much could be achieved through energetic use of limited military resources, aided by regular modest reinforcements from the west.

The coastal ports became the most urgent targets. Between 1099 and 1124 the Franks captured all the ports of the Syrian and Palestinian coast except Ascalon, which held out until 1153. Each success was achieved with the assistance of western fleets: Jaffa in 1099 (Pisans); Haifa 1100 (Venetians); Arsuf and Caesarea 1101 (Genoese); Tortosa and Jubail 1102 (Genoese); Latakia 1103 (Genoese); Acre 1104 (Genoese); Tripoli 1109 (Genoese and Provençal); Beirut 1110 (Genoese and Pisan); Sidon 1110 (Norwegian); Tyre 1124 (Venetian). Without a fleet, as at Tyre in 1111, or where a fleet failed to impose a complete blockade, as at Sidon in 1108, sieges failed. At Ascalon in 1153, reinforcements from the bi-annual passage of fleets from the west helped the Frankish fleet tip the balance after months of failed naval blockade. The dual role of Italian maritime cities as military allies and commercial entrepreneurs was recognised by grants of extensive lucrative trading immunities and privileges to the Genoese at Antioch, Jubail, Acre and Jerusalem, and the Venetians’ reward of a third of the city of Tyre after its capture in 1124. Such commercial encouragement directly benefited rulers through tolls on trade and the thousands of pilgrims the Italian shippers transported each year.

Beyond pious tourism, imports to Outremer included leather, fur, timber, warm textiles such as wool and some culturally specific foodstuffs, including bacon. The Franks’ taste for pork remained undimmed, as excavated rubbish dumps and middens testify, some of it probably supplied by local Christian communities. Apart from a booming trade in relics, the most high-value exports were cane sugar, luxury textiles and spices. The rulers of Outremer took advantage of shifting trade routes across western Asia which, with the growing dominance of western shippers in the Levant, increased the volume of trade through the ports controlled by the Franks. Acre emerged as a major entrepôt, with links to the west, to the Asian interior via Damascus and to Egypt. The importance of cosmopolitan commerce was recognised by Baldwin III (king of Jerusalem 1143–63), who granted a safe conduct to a Muslim merchant from Tyre, a copy of which found its way into a storeroom at the great mosque in Damascus. Commercial success depended on a contradiction noticed by a Spanish Muslim visitor in 1183, the Franks giving free access to their ports from the Turkish-held interior, even during times of war.13 Other sources of income for the new rulers came chiefly from minting coinage; exploitation of inland caravan routes in the desert and semi-desert beyond the Dead Sea and Judean hills; and control of the agrarian economy as rent-collecting landlords. The distribution of castles and stone towers across the interior of the kingdom of Jerusalem shows that oversight of rural estates was as important as frontier protection and defence.14

The Franks’ investment of Outremer followed strategic necessity. Antioch sought to annex the Upper Orontes valley and Cilicia and threaten Aleppo; Edessa to establish strongholds across the Upper Euphrates valley; and Tripoli to conquer the Biqa valley and the Homs gap that led from the sea through the Lebanese mountains to the Syrian interior. Each pursued immediate political advantage, willing, if convenient, to ally with Armenians, Arabs or Turks. This did not obscure a religious dimension. Antiochene coins showed the head of St Peter. The priorities for the Jerusalem Franks were more constrained by their role as defenders of the Holy Places, emphasised on coins that depicted key sites in the Holy City (e.g. the Tower of David or the Holy Sepulchre).15 The chief religious sites were quickly secured: Jerusalem itself, where non-Christian residence was symbolically outlawed, Bethlehem, Nazareth, Hebron (supposed site of the tombs of the Old Testament patriarchs), and the rest of the Biblical Holy Land from the Jordan to the sea, Banyas and the Dog River in the north to Ascalon and Beersheba in the south. However, the settlement remained vulnerable. Egyptian attacks in 1101, 1102 and 1105 on occasion penetrated to within twenty-five miles of Jerusalem. Invasions by Mawdud of Mosul between 1110 and his assassination in 1113, and a further attack from Mosul in 1115, devastated parts of the county of Edessa and, in 1113, threatened Galilee. The Franks were helped by the fragmented politics of their Syrian neighbours, who were equally dismayed by the prospect of dominance from Iraq as by the presence of the Franks. The febrile relations between Aleppo, Damascus, Mosul and Baghdad offered the Franks opportunities for alliances regardless of religious scruples. The Franks of Antioch occasionally allied with the Turkish ruler of Damascus against Aleppo and even, some sources suggested, against fellow Franks at Edessa.16 Diplomatic alliances, such as between Damascus and Jerusalem, were commonplace during the first half-century of Frankish occupation and temporary truces were frequent throughout. The Outremer lordships took their places among the competing city states and regional principalities jostling for survival and ascendency. Their existence demanded a high degree of non-confessional political flexibility and ingenuity (see ‘Coins in Outremer’, p. 120).

Politics

The kingdom of Jerusalem became the leading polity of the Frankish settlement in charisma and resources. The early kings managed to subordinate the territorial ambitions of their acquisitive nobles to fashion a coherent political system in which precedence was afforded the royal High Court; land and money fiefs were held from the monarch; and military obligations to the king’s summons were accepted and performed. This was achieved by mutual recognition of rights. Territorial lords were autonomous in their own lands, such as the great fiefs of Jaffa, Ascalon, Transjordan or Galilee, but in cases of rebellion or other conflict, royal jurisdiction was accepted by them and their Frankish subjects. By the reign of King Amalric (1163–74), under a legal procedure known as the assise sur la ligece, subtenants were to swear allegiance directly to the king and thus, in theory, were given the right to sue in the High Court, even against their own lords (although none is known to have actually done so). The king exercised the right to summon to arms his tenants and popular militias; to call assemblies to discuss matters of common interest, such as an emergency tax in 1183; and to make church appointments. This last flew in the face of the very principles of church autonomy that underpinned the policies of the papal reformers who had conceived of the idea of the Jerusalem war. Despite the impression retrospectively given by thirteenth- and fourteenth-century law books, the kingdom was governed by pragmatism not legalism. Survival depended on cooperation and mutual self-interest between king and nobles, with the crown holding the most lucrative parts of the kingdom based on Jerusalem, Acre, Tyre and the region north of the capital around Nablus, and, although lacking an extensive or sophisticated bureaucracy, dispensing lucrative preferment and protection.

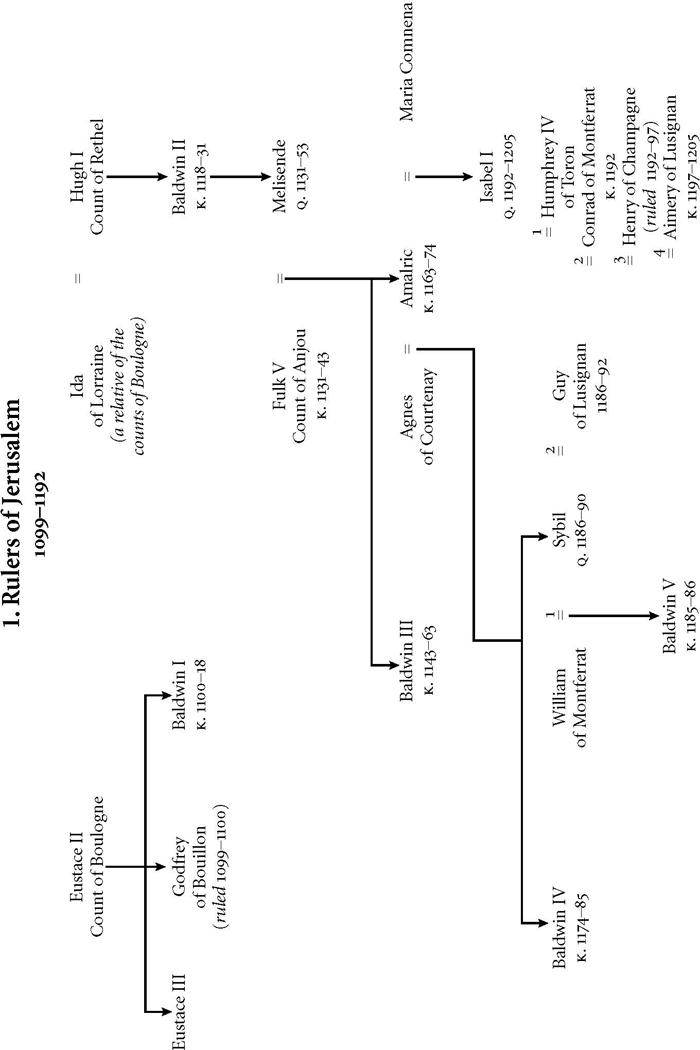

This accommodation became especially important as the kingdom’s stability was threatened by a sequence of dynastic and political crises. Succession to the crown was openly disputed in 1100, 1118, 1163 and 1186. Civil war threatened in 1133–4, 1152 and 1186. The chief minister was assassinated in 1174. Baldwin II (1118–31) spent a year in Turkish captivity (1123–4), a fate similarly suffered by significant numbers of Frankish nobles throughout the period. The marriages of two kings, Baldwin I and Amalric, were successfully challenged as bigamous or uncanonical. Only twice in eighty-eight years did a son succeed father (in 1143, a child; and 1174, a leprous child). Minors inherited in 1143, 1184 and 1186. Baldwin I may have been homosexual; Baldwin IV (1174–85) was a leper. Of the eight kings between 1100 and 1188, Fulk (1131–43) died as a result of a hunting accident, his sons Baldwin III (1143–63) and Amalric died in their thirties, Baldwin IV in his twenties and Baldwin V (1185–6) succumbed as a child of nine. However, dynastic misfortune and complexity were not the unique preserves of Jerusalem. With the exception of France, orderly royal succession was rare throughout twelfth-century Christendom. Muslim Syria and Egypt also shared confused successions, rule of minors and political assassination. Similarly disrupted inheritance among the Frankish nobility allowed kings to exploit the lack of adult male heirs that also attracted ambitious nobles from the west eager to enhance status, most famously Raynald of Châtillon, younger son of a minor lord from central France who rose, through two successive marriages, to become Prince of Antioch (1153–61) and lord of Transjordan (1177–87). Such figures relied on royal patronage or approval, as did church appointments where a colonial dimension was most marked. Almost all episcopal appointments went to western immigrants, often second- or third-raters who stood little chance of similar preferment in the increasingly competitive home ecclesiastical job market.

COINS IN OUTREMER

The coinage of the Frankish Levantine conquests revealed the extent of the conquerors’ reliance on the region’s economic and commercial system. Unlike in western Europe, where currency was silver-based, gold provided the high-value coins in the eastern Mediterranean. In general the Levantine economy was far more monetised than in the west, despite a marked increase in the amount of bullion and coin in circulation and use in Europe during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. Initially, the Outremer Franks operated a hybrid system that included silver coins from western Europe, mainly northern Italian and southern French; copper coins based on local Arabic or Byzantine designs with modest Frankish iconographic modifications; and local silver and gold coins, dirhams and dinars. Under Count Bertrand (1109–12), Tripoli issued silver pennies of Toulousain design. In the early years, Antioch used Seljuk coins. The gold coins minted in Tripoli and, after 1124, in the kingdom of Jerusalem (bezants), were simply copies of Fatimid dinars, complete with Arabic Koranic inscriptions, a habit that lasted until banned in the 1250s by an outraged visiting papal legate. Even then the new Christianised designs were in Arabic. Only in the 1130s and 1140s did Antioch, Tripoli and Jerusalem begin to mint their own silver coins, billon (i.e. debased silver) pennies. In Jerusalem the initial reform under Baldwin III by the 1140s was superseded by a lasting new issue under Amalric in the 1160s. The chief mints were located in Antioch, Tripoli, Tyre, Acre and Jerusalem. Re-coinages appear to have been irregular. Some local lords minted their own silver and copper coins, as at Jaffa, Beirut and Sidon, while others produced, presumably for immediately local consumption, lead tokens, perhaps as small change, or to pay labourers and tradesmen, or even for use in gambling. In addition, Turkish coppers seem to have been in common use across Outremer, as small change.

39. A Tripoli imitation of a Fatimid bezant.

This heterogeneous eclectic coinage reflected Outremer society and its commercial needs. Inevitable economic exchange between the different communities required a degree of currency synergy between Frankish and neighbouring currencies as well as coins that would be familiar across social, religious and linguistic divides within Outremer. The Franks were never in an imperial position to impose a wholly exclusive financial system on the indigenous population. Equally, the high-value bezants’ aping of Egyptian currency acknowledged the mutual dependence between Frankish rulers and Syrian and Egyptian traders and merchants. Although lighter, and of less fine gold, than the dinar, the Frankish bezant could act almost as a proxy common currency. It formed part of the Franks’ rapid assimilation into the regional gold-based monetary system; the great Jerusalem tax of 1183 was calculated and paid in bezants as were land values and wages.17 On the other hand, the introduction of a distinctive Frankish silver penny across Outremer at roughly the same time in the 1130s and 1140s suggests an advance of government administration and political reach, as well as possibly an increased Frankish demographic footprint.

40. A denier of King Amalric of Jerusalem showing the rotunda of the Holy Sepulchre.

The collapse and limited reconstruction of Outremer after 1187 left its mark on minting and coins in circulation. The Third Crusade, and probably the Fifth as well, saw an immense influx of western coins, mainly silver pennies, a trend that continued into the thirteenth century. There appears to have been no systematic attempt to re-mint these coins into local currency, suggesting they circulated within ports where multiple currencies operated, while pointing to the new limits to the power of the local Frankish rulers. These continued to mint coins as before, still on an ad hoc and perhaps restricted basis. The needs for bezants remained in the prosperous commercial centres such as Acre. Local lords in Tyre, Beirut and Sidon continued to issue their own silver pennies and coppers. This is hardly surprising as, proportionately, incomes increasingly came from trade not land. However, the production of copies of Ayyubid drachmas after 1251 mirrors shrinking Frankish dominion and underlined the constant reality of Outremer’s integration within the wider economy and commerce of the eastern Mediterranean and the Fertile Crescent.18

The political history of Frankish Jerusalem is commonly divided into three broad periods: expansion with a focus on northern Syria to the 1140s; competition with Nur al-Din of Aleppo in Syria and then Egypt from the mid-1140s to late 1160s, encompassing the failure of the Second Crusade and Amalric’s abortive attempt to control the Nile; and subsequent decay and defence in the face of Saladin’s ascendancy in uniting Egypt and Syria in the 1170s and early 1180s, culminating in the disastrous defeat of the Jerusalem army at Hattin in 1187 and the subsequent loss of most of the kingdom. This conceals continuities, such as the unstable intimacy of the domestic political scene, dominated by a handful of nobles jostling for access to or control over the wealth at the king’s disposal. There was no clear trajectory of stability or decadence. The early conquests of 1099–1124 were punctuated by serious defeats, in 1102 or 1123 when Baldwin II was captured. Despite setbacks in 1129 and 1148 at Damascus; the near civil wars, in 1134 between the Angevin King Fulk and the local baronage, and in 1152 between Baldwin III and his mother Queen Melisende; and the rise of Nur al-Din to dominate Syria in the 1150s, Baldwin III was still able to broker power in Antioch and Tripoli and extract tribute from Egypt. Comparably, Antioch suffered repeated defeats and the death or capture of its leaders, in 1100, 1104, 1119, 1130, 1149 and 1161, and disruptive power struggles within the ruling family in the 1130s, yet survived as a Frankish city state until 1268. Tripoli managed to assert and maintain its separate identity from the 1120s despite limited territory, a series of succession disputes down to the 1140s, the assassination of one count (Raymond II in 1152) and the long captivity of another (Raymond III 1164–74; his first cousin Amalric of Jerusalem acting as regent). The kings of Jerusalem regularly intervened to rescue the other principalities during such crises, an involvement that assumed a dynastic dimension after two of Baldwin II’s younger daughters married into the ruling houses of Antioch and Tripoli.

The paradox of vulnerable strength persisted. In the 1160s, despite the loss of Banyas in northern Galilee, Amalric of Jerusalem was able to compete vigorously for control of Egypt. In 1176–7 an assault on Saladin in Egypt, with help from a large Byzantine fleet and western arrivals, remained possible. From mid-century, the increasing use of the new Military Orders of Templars and Hospitallers to garrison strategic castles showed both an awareness of the mounting threat from Muslim Syria and a policy to deal with it, while simultaneously signalling a lack of royal resources forcing kings into dependence on the Military Orders (see Chapter 4). At the same time, increased fortification of strong-points deep within the kingdom, even near Jerusalem itself, spoke of resources and resilience as well as the heightened reality of danger. Land for sale around the Holy City remained at a premium in the 1160s.19 Between the 1120s and 1170s most of the kingdom of Jerusalem was free from attack. The power vacuum of a leper king between 1174 and 1185 exacerbated internal divisions but did not prevent military victory over Saladin at Montgisard in 1177 or raids to the Red Sea and Arabian coast under the auspices of Raynald of Châtillon in 1183. In the same year, the levy of a general tax following a fiscal survey of the realm and the consultation of a representative assembly spoke of financial strain yet robust political institutions.20 Saladin’s own serious illness in 1185–6 threatened the unity of his empire. His death would have destabilised it, letting the Franks off the hook, if only temporarily.

On such a narrow stage damaging factionalism could not be avoided. In 1100 a group of Boulogne loyalists ensured the succession of Godfrey of Bouillon’s brother Baldwin in the face of opposition from the legate Daimbert and the ambition of Tancred of Lecce. A coup in 1118 led to the accession of Baldwin II to the exclusion of the legitimist heir Eustace of Boulogne, Baldwin I’s elder brother. The deal brokered by Baldwin II for Count Fulk V of Anjou to marry his eldest daughter Melisende and for them, after his death, to rule jointly, in association with their son, the future Baldwin III, almost came unstuck twice. In 1133–4 local nobles, under Count Hugh of Jaffa (himself an incomer who spent his youth in the west), a cousin of Baldwin II, rebelled against what they may have seen as an Angevin takeover of power and the marginalisation of the rights of Queen Melisende. The rebels even called in help from the Fatimid garrison at Ascalon. Fulk survived but Angevin influence was reined in. In 1152 the now adult Baldwin III had to use force to prise power from his mother and her protégés. In 1163, before allowing his coronation, baronial opposition forced Amalric to repudiate his first wife, Agnes of Courtney, possibly on the grounds of bigamy, certainly to prevent Agnes wielding patronage. In 1174 the chief minister, Miles of Plancy, another westerner, was murdered during a baronial struggle to control the new leper king. From 1174 to 1186 the political vacuum caused by Baldwin IV’s illness and his nephew Baldwin V’s infancy removed the safety net of royal arbitration as different factions near the throne scrapped for control of patronage and policy. On Baldwin V’s death in 1186 these rivalries almost spilled into open civil war in a move orchestrated by the disruptively ambitious Raymond III of Tripoli, by marriage lord of Galilee. The dead child king’s first cousin twice removed, Raymond, tried to deny the crown to Baldwin’s mother Sybil, elder daughter of King Amalric, and her second husband, Guy of Lusignan. When his counter-putsch failed, Raymond seceded from obedience and allied with Saladin, treason only repudiated when the whole kingdom was threatened with invasion the following year.21

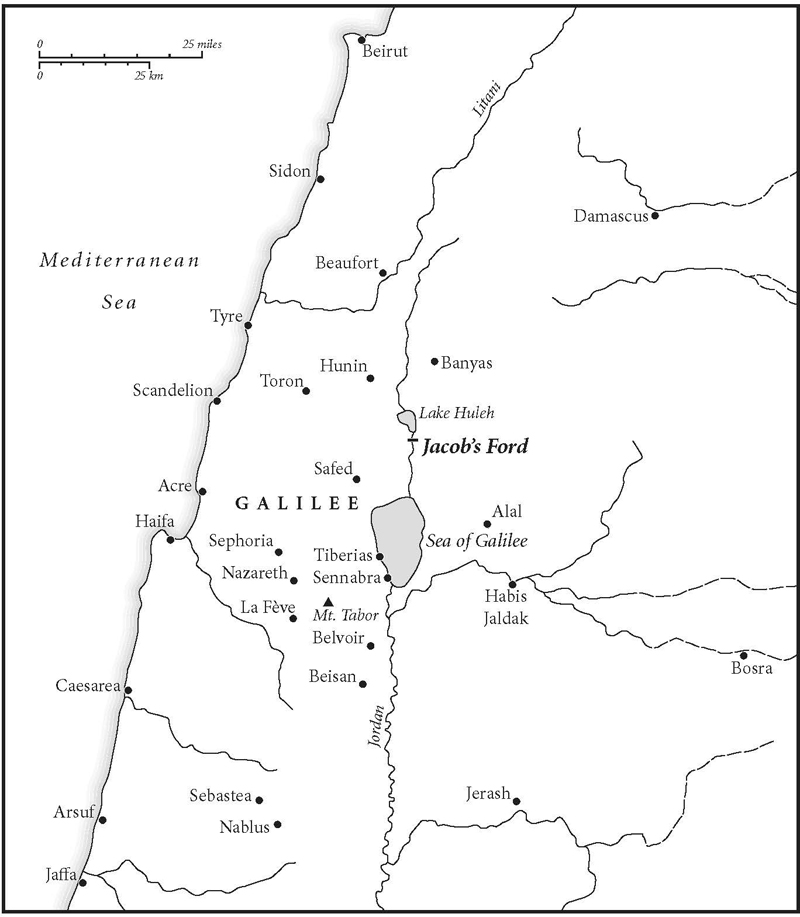

The hindsight of the catastrophic defeats of 1187–8, when Outremer was almost completely overrun by Saladin after his devastating victory over the Franks at the battle of Hattin, frames a seemingly dismal picture. Yet such teleology misleads, masking a more uneven narrative of opportunity and accident. Factional feuding, succession crises, rebellion and civil war were as rife in twelfth-century England as in Jerusalem. The rise and the ultimate fall of the kingdom were far from determined or inevitable. Attacks on Damascus in 1129 and 1148, Aleppo in 1124–5 or Shayzar in 1111, 1138 and 1157 could have expanded Frankish rule into the Syrian interior and annexed major centres of power. The losses of the strategically important northern Galilean strongpoints of Banyas in 1164 or Jacob’s Ford in 1179 were exceptional; they were neither preordained nor were their consequences inevitable (see ‘A Day at Jacob’s Ford’, p. 128).

Baldwin III had imposed tribute on the rulers of the decayed Fatimid caliphate of Egypt and the full conquest, planned by him and pursued by his brother Amalric in the 1160s, came close at least to military success. The effectiveness and adaptability of Frankish arms should not be underestimated. Diplomatic alliances with Byzantium in the 1150s and 1170s, with the marriages of Baldwin III and Amalric to Greek princesses, potentially offered much. Famous defeats such as the Antiochene disasters at the Field of Blood (1119) or Inab (1149) were avoidable, as was the disaster at Hattin in 1187, a battle as notable for how nearly the Franks won it as for the annihilating scale of Saladin’s victory.22

Society and Shared Space

The internal development of Outremer society cannot be assessed solely in terms of a failed or doomed community. Despite impediments of religion, culture, geography and resources, the Franks secured their occupation and even thrived for generations. The elites governed themselves according to agreed structures of law, judicial procedure and convention. As in the west, rulers consulted their officials, great lords, clerics and others in deliberative councils, as at Nablus in 1120, which promulgated canons mainly concerning moral behaviour and relations with the Church, or in 1183 to agree a general tax in the kingdom of Jerusalem. Military contingency required constant informal as well as formal consultation. Politics and patronage sought validation in legal process, the ruler’s High Court providing a cockpit for factional contest as much as judicial settlement. This could be writ large, as at Tripoli in 1109, where Baldwin I presided over a council of all Outremer to settle outstanding territorial claims.

While Frankish institutions were imported, elements of continuity survived in the configuration of lordships, partly a product of geography, as in the boundaries of the county of Tripoli. In Antioch and Edessa the presence of large indigenous Greek and Armenian Christian communities enforced a degree of institutional accommodation. In Antioch it seems the mainly Norman ruling elite adopted the local Greek title of dux (duke) for the leading civilian official.23 In general, Franks imposed their own officials to administer their military, judicial and administrative responsibilities while Frankish landlords relied on their own or local mediators with their indigenous subjects and tenants, Syrian dragomanni (literally interpreters) or a ra’is (headman).24 As elsewhere around the Mediterranean, internal self-determination allowed for separate communities to co-exist as neighbours. The Franks’ relations with the indigenous Syrian population within Outremer were primarily economic not social, as taxpayers, workers or slaves, not citizens.

This produced a layered political and legal society, in which each community regulated itself, with relations between them – fiscal, commercial or criminal – ordered and scrutinised by ruling Franks, through law courts and lordships. Syrian Christians, Muslims and Jews held their own courts for civil disputes and petty crimes, as did the Franks, but serious offences and any involving Franks came before the Frankish cour des bourgeois, often presided over by Frankish officials called viscounts, operated by local Frankish lords according to western legal norms, such as trial by combat. Freedom was assumed for all Latin Christian settlers of whatever social or economic standing, in marked contrast to social systems in the west. Local Syrian Christians, Muslims and Jews were largely excluded from this ruling legal and political community. In ports, such as Acre or Tyre, inevitable inter-communal exchange was regulated by commercial courts dealing with judicial and fiscal responsibilities. Syrian Christians acted as port officials. In the market court (cour de la fronde), both Latins and Syrians could act as jurors while witnesses across the faith communities swore oaths on their respective holy books, ‘because be they Syrians or Greeks or Jews or Samaritans or Nestorians or Saracens, they are also men like Franks’ – necessary pragmatism not ecumenical tolerance.25

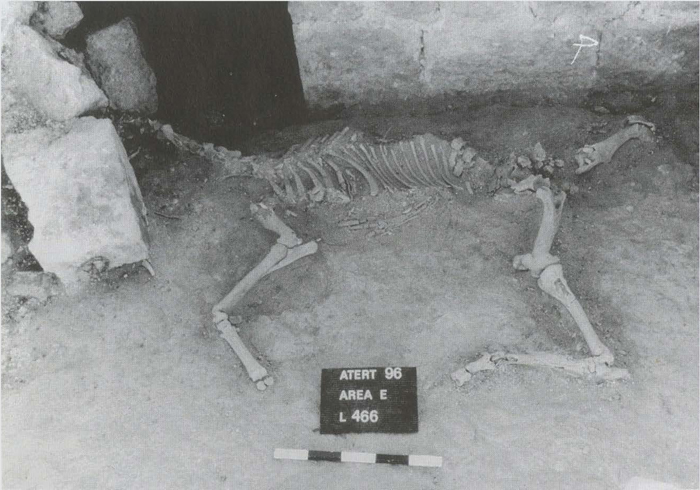

A DAY AT JACOB’S FORD, 29 AUGUST 1179

At dawn on 29 August 1179, following a siege of five days, troops led by Saladin launched a final assault on the Frankish castle of Le Chastellet overlooking a strategic crossing of the River Jordan on the main road from Acre to Damascus in Upper Galilee know as Vadum Iacob, or Jacob’s Ford, a site associated with the Patriarch Jacob and of scriptural and spiritual significance for both Muslims and Christians. The castle, commanded by Templar knights, was unfinished, having only been begun the previous October, which meant that its defenders, a substantial force perhaps numbering 1,500 men, included many civilian masons, carpenters and other building workers and Muslim captives as slave labour. The importance of the castle, only a day’s walk from Damascus, on the Ayyubid side of the porous frontier with the kingdom of Jerusalem, was recognised by the attendance of Baldwin IV of Jerusalem and his army from October 1178 to April 1179 to protect the early stages of construction and to prevent Saladin’s repeated attempts to stop the building by diplomacy or force, even by offering 100,000 dinars in compensation if the Franks withdrew. In late August, knowing a Frankish relief force would take time to assemble, Saladin, aware that time was of the essence, attacked in strength. Although his siege machine failed to effect a decisive breach, after five days, early on 29 August, sappers finally managed to bring down sections of the walls, the fire used in the process setting alight the Franks’ final makeshift wooden lines of defence. It was reported that the commander of the garrison deliberately leapt to his death in the flames. Saladin refused a negotiated surrender. Perhaps as many as 800 defenders were killed, with 700 captured, along with armour, weapons and animals. Some of the captured were converts from Islam who were summarily executed. The loss of Le Chastellet at Jacob’s Ford was both a tactical success for Saladin after his defeat in 1177 at Montgisard and a strategic one, as it left Galilee open to future attack. Some have seen this day as the beginning of the military process that ended at the battle of Hattin in 1187.

41. Aerial view of Ateret Fortress showing the north-west wall of the castle.

42. A horse killed during the siege.

The site of the castle was left relatively undisturbed until excavations in the 1990s uncovered what was in effect a time capsule of both the siege and the elaborate building work at the castle. Construction was evidently interrupted by the Ayyubid attack, tools and materials being left where they lay. The unfinished nature of the project was clear, as was the nature of the fighting and of injuries suffered by the combatants. The defenders had been bombarded with intense volleys of arrows before the final assault, skeletons showing evidence of arrow wounds prior to death blows from close-quarter weapons, swords, spears or axes. As well as the remains of men and horses who fell that day, the site was littered with tools – axes, chisels, spades, hoes, spatulas for spreading plaster and mortar and picks – as well as sickles, knives, daggers, iron bowls, mace heads, arrow-heads, crossbow bolts, a wheelbarrow, a stone sundial and a board for marelles, or Nine Men’s Morris, a strategy board game permitted by the Templars. The castle was equipped with a cistern and a communal oven and apparently used its own lead coins to supplement royal gold bezants and silver pennies. Le Chastellet was planned on a grand scale, to house a large Templar community of knights, sergeants, servants and, probably, Muslim slaves. Its construction and loss show the scale of the Franks’ ambition, human and material resources, their technical skills and their vulnerability.26

Community parallelism determined interfaith contacts and infra-Christian denominational relations. Limited religious syncretism did exist, in shared shrines, religious space, rituals (for example, Muslims receiving baptism as a curative superstition, not a sign of conversion) and objects of devotion, such as the Greek Orthodox shrine of the Virgin Mary at Saidnaya near Damascus, the icon of the Virgin at Tortosa, or the Tombs of the Prophets at Hebron, each venerated by Muslim as well as Christian pilgrims. Inter-faith association relied on linked folk beliefs, as in the generalised efficacy of baptism, not theological exchange, tolerance or ecumenism. Jews and Muslims were formally banned from living in Frankish Christian Jerusalem. In the twelfth century, few Franks mastered the literary Arabic to engage fully either with Islamic culture and beliefs or with local Christians, although many probably necessarily acquired a smattering of demotic oral Arabic.27 Muslims and non-Latin Christians lived beyond the pale of Frankish citizenship, like serfs in the west, although, like Frankish non-fief holders, they could be arraigned in the Frankish cour des bourgeois. Unable to plead in Frankish civil courts, technically they could hold neither office nor land. There were some exceptions, such as Hamdan ibn Abd al-Rahmin (c. 1071–1147/8), a local Muslim intellectual, whose medical services to the Frankish lord of Atharib, a town near the Antioch/Aleppo border, was rewarded with the fief of a local village. A member of the Arab ruling family of Shayzar leased a village from a neighbouring Frankish knight. In Nablus, Muslims and Frankish Christians lived side by side, operating neighbouring businesses, even intermarrying.28 Obviously, the Franks exploited Muslim labour, including slaves, while encouraging Muslim entrepreneurs to use their ports. They also drew distinctions between the largely quiescent Muslim fellahin living within Outremer, the often-accommodating Bedouin on the frontiers and the hostile Turks across the borders with whom, nonetheless, diplomatic treaties of convenience or even active alliances could be entertained. The Franks’ mission to defend the Holy Land and Holy City did not preclude civil relations with Muslims of equal social standing on an individual basis, such as the Templars in Jerusalem providing space for Muslim visitors to pray towards Mecca.29 The great hospital in Jerusalem, run by the Order of St John, the Hospitallers, was open to all in need regardless of faith.

Nonetheless, within Outremer, religion stood as an absolute barrier to integration, reinforced by civil and criminal laws that discriminated against Muslims. As slaves, labourers, taxpayers, skilled artisans, doctors and traders, Muslims were useful; otherwise, collectively, they existed socially as separate and invisible. Only conversion to Latin Christianity, for Muslims as well as Syrian Christians, secured full citizenship, and the Franks were notoriously negligent in proselytising. A similar picture emerges of Jews, who were left to arrange their own affairs, controlled by rabbinical courts, while contributing to the economy through agriculture in areas of settlement such as Galilee, and in particular, it seems, the dyeing business. At Nablus, the local Samaritan sect was allowed to hold its annual Passover festival, attracting the faithful from across the Near East, a unique example of tolerance of such a non-Christian religious event.30 Religious segregation operated in a two-way street. Although some Christian commentators, such as William of Tyre, noted the differences between Sunni and Shi’ite Islam, most Muslim observers largely ignored the complexity of Christian denominations, dismissing Christians as polytheists.31 Religious bigotry was not the unique preserve of the Franks.

6. Jacob’s Ford.

Language and culture also limited assimilation with local Christians. Two main Christian groups confronted the Franks in Outremer. The Orthodox Church shared belief in the Trinitarian doctrine agreed at the Council of Chalcedon (451). Strong in the kingdom of Jerusalem and Antioch, the Orthodox community divided between a Greek elite and the mass of Arabic speakers who used Arabic or Syriac in their services. On doctrinal grounds, the Franks regarded the Orthodox as members of the same Catholic Church. The other Christian group included ancient indigenous denominations with origins in doctrinal disagreements stretching back to Chalcedon and beyond: Jacobites, Armenians, Nestorians and Maronites. Relations with all these communities depended on politics, status, space, patronage and precedence as much as observance, doctrine or dogma. Ironically, official Latin Catholic relations with the Chalcedonian Orthodox Church proved more fraught than those with the non-Chalcedonians. All were tolerated but the latter, having no hierarchical association with the Latin Church, were afforded protected autonomy, even patronage, whereas the Orthodox Church presented direct competition, at least at the level of episcopal appointments and jurisdiction. Twelfth-century Antioch saw a bitter protracted battle between Latin and Orthodox hierarchies. In Jerusalem, the Latin patriarchs were shadowed by absentee Greek equivalents based in Constantinople. By contrast, ecclesiastical contacts with the Jacobites, strong in northern Syria, and the Armenian Church, prominent in Edessa, were broadly amicable, if largely characterised in the secular sphere by indifference and what has been described as ‘rough tolerance’.32 Political expediency played a role, such as the availability of Armenian noblewomen for Frankish marriages. The Maronites of Lebanon, valued for their military capability, were even persuaded to enter into communion with Rome in 1181 despite their historic doctrinal and continued linguistic and cultural differences.

Away from ecclesiastical politics, contacts were governed by expediency. Flushed with victory in 1099, the Franks initially banned all non-Latin clergy from the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. The failure of the Easter Holy Fire ‘miracle’ in 1101 prompted a relaxation of the ban, allowing access to Orthodox clerics (who presumably knew the secret of generating the miraculous flame, important for Easter tourism), an arrangement followed in other shared churches in Jerusalem. Local Orthodox bishops cooperated with the Latin hierarchy, such as Archbishop Melitus of Gaza who received property for the Hospitallers in the 1170s and was a confrater of the order.33 Greek monasteries around Jerusalem and Antioch flourished during the twelfth century; St Sabas in the Judean desert attracted Frankish patronage. Orthodox monasteries such as St Sabas, those on the Black Mountain near Antioch or the famous monastery of St Catherine at Mount Sinai acted as cultural entrepôts for manuscripts, icons and artists. Funds from Byzantium flowed into the Orthodox community but also paid for redecoration in Latin churches, such as the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem and the Holy Sepulchre. Syrian Orthodox Christians acted as scribes and customs officers. The small Jacobite community in Jerusalem, despite being regarded as heretical by the Latins, was allowed to build a chapel near the entrance to the rebuilt Church of the Holy Sepulchre and on at least one occasion received royal protection for property rights.34 Circumstances could impose inter-denominational contacts and accommodation or the reverse. The Edessan Frankish lord Baldwin of Marasch (d. 1146) apparently spoke Armenian and employed an Armenian priest as his confessor.35 However, Count Joscelin II of Edessa (1131–59) regarded the county’s Jacobites as fifth columnists cooperating with the Turks and harassed them accordingly.

Outremer’s heterogeneity inevitably eroded formal apartheid, although the loss of most of the material evidence of Frankish settlement makes uncovering informal assimilation difficult, as surviving written evidence points to sharp religious division and much archaeology is of culturally exclusive religious or military sites, although many castles reflected long periods of occupation both before and after Frankish tenure. New ecclesiastical architecture showed European inspiration most clearly, although in the twelfth century largely immune from fashionable contemporary French Gothic. In places, it also borrowed distinctive local Near Eastern features – flat roofs, domes, simple geometric lines. Domestic architecture and decoration have mainly vanished, although what does survive suggests Franks imported some styles and features familiar from the west, such as houses opening directly onto the street with plots of land behind. Other vernacular structures – water mills, bridges, store houses, etc. – displayed local pragmatism not cultural imperialism, as did the use of plentiful stone, not scarce timber, as the chief domestic construction material.36 Prestige buildings could attract an eclectic mix of aesthetic and material influences. An early thirteenth-century pilgrim’s literary description of palatial apartments in the Frankish castle at Beirut is suggestive: the interior was dominated by marble floors and fountains, trompe-l’oeil mosaics and frescoes produced by skilled local craftsmen (see ‘Syrians, Muslims and Greeks’, p. 230).37 Cultural exchange from patron to designer to artisan to labourer is evident elsewhere. The cover and illuminations of the famous psalter prepared for Queen Melisende, now in the British Library, combine western, Byzantine, Armenian and Islamic influences (see ‘The Melisende Psalter’, p. 138). The decorative scheme at the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem, financed by the Byzantine emperor Manuel I, displays a similar cultural mix (see p. 51). In a polyglot, multi-faith and, in cities, cosmopolitan society, accommodation was inescapable. The written record of the land deal between the Hospitallers and Archbishop Melitus of Gaza is in both Latin and Greek, as were inscriptions in the Church of the Nativity. Baldwin III issued safe conducts for Muslim merchants and Arab lords, such as the peripatetic Usama ibn Munqidh of Shayzar, whose large library of Arabic books he apparently seized.38

The Franks adapted to a monetised economy very different from that in western Europe. Local currency, such as gold bezants, continued under the Franks, who persisted in minting imitation Arabic coins. Although Tancred produced his own copper coinage at Antioch by 1110, in Jerusalem no distinctive Frankish currency was produced before the 1130s at the earliest, while imported foreign currencies from Lucca and Valence long remained standard tender. Baldwin III may have been the first king to engage in a substantial re-coinage programme, asserting a royal monopoly on minting in the kingdom, a policy followed by his successor Amalric.39 The fiscal and social role of money was more immediately adopted. Patronage dealt in money fiefs drawn on the revenues of cities, some still calculated in Saracen hypereroi, as well as grants of land.40 The 1183 tax on incomes and property was assessed in bezants. Absorption of indigenous culture had limits. The Arabic texts left by the Franks on the walls of the Dome of the Rock and the al-Aqsa mosque (under the Franks the headquarters of the Templars), or on the imitation bezants minted at Acre, did not suggest understanding of the Koran from which they came; rather they were seen as decorative and, in the case of the bezants, usefully familiar and convertible for indigenous merchants.41

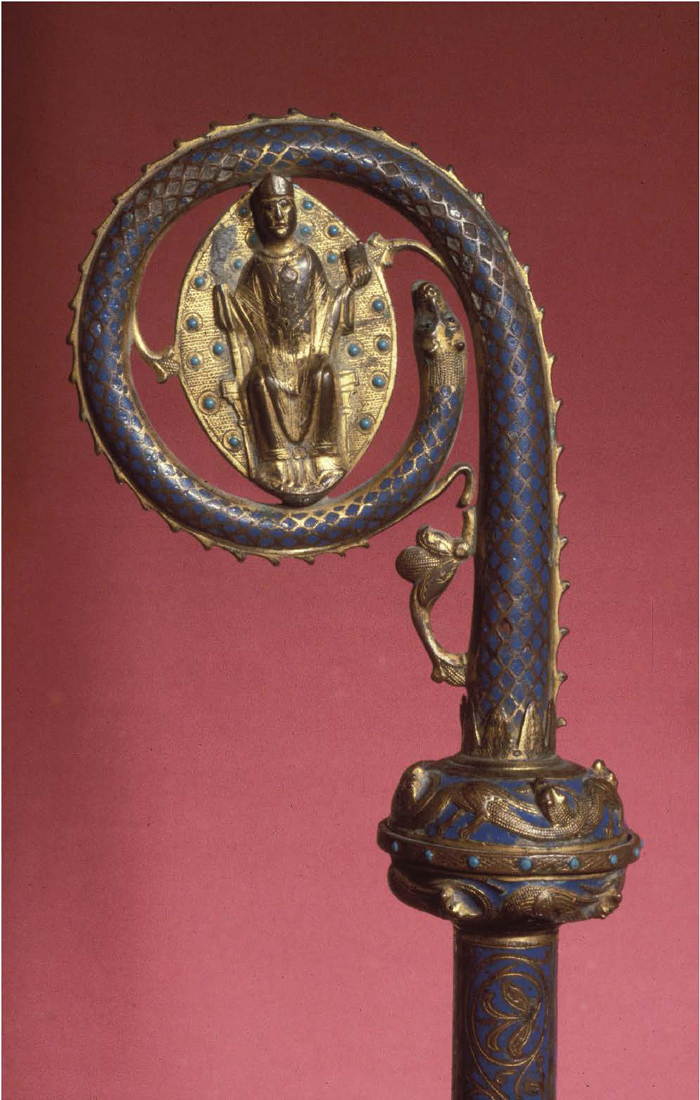

43. A twelfth-century bishop’s crozier found at the Church of the Nativity, Bethlehem.

Diversity

44. The church of St Anne’s, Jerusalem, an 1856 engraving.

The courts of the Frankish rulers, like those of their Syrian and Egyptian neighbours, reflected diversity. Nur al-Din (d. 1174), the Turkish atabeg of Aleppo and conqueror of Muslim Syria, ruled over Jews, Muslims, Christians, Arabs, Turks and Armenians, and employed Kurdish mercenary chiefs. The Fatimid caliphs in Egypt employed Christian Copts and Armenians as secretaries, generals and administrators; the Vizier Bahram (1135–7), called the ‘Sword of Islam’ (Saif al-Islam), was originally an Armenian Christian whose brother was the Armenian patriarch of Egypt. Kurdish Saladin’s entourage included Jewish physicians, Iranian and Iraqi civil servants as well as Turks, Arabs and fellow Kurds. Franks not only allied with Turks; some also fought for them, as was permitted under Jerusalem law. The court of King Amalric (1163–74) shared the cosmopolitan Near Eastern pattern. His mother, Queen Melisende, was half-Armenian; his father a Frenchman from Anjou. His first wife was a Palestinian Frank; his second a Byzantine Greek princess. Apparently, he unsuccessfully sought the medical aid of the great Jewish scholar and physician Maimonides (1135–1204), then living in Egypt. The academic tutor of Amalric’s son Baldwin – William of Tyre – was a Jerusalem Frank educated for two decades at the grandest schools of the west – Paris, Orléans and Bologna – while young Baldwin’s riding master was a Palestinian Christian whose father and brother served as the king’s doctors before the family decamped after 1187 to serve Saladin. Jewish, Samaritan, Syrian Christian and Muslim physicians were popular with the Frankish nobility, much to William of Tyre’s disgust. Raymond III of Tripoli’s doctor, a local called Barac, treated the ailing Baldwin III in 1163.42 Antioch, with its rich intellectual history and continued contacts with the academic centres of inner Syria and Iraq, provided a forum for cultural exchange, although chiefly via local Greek- and Arabic-speaking Christians.44 Such cross-community links only grew as the Franks entrenched their presence in Levantine society, settlers picking up demotic Arabic. Frankish rulers could receive similar deference as that afforded their Arab or Turkish predecessors. The process began early. An Arabic poet celebrated the deeds of his employer, Raymond IV of Toulouse, at the battle of Ascalon (1099). The funeral processions of Baldwin I (1118) and Baldwin III (1163) attracted locals from across the ethnic and religious divides, including Muslims, some of whom may have been professional mourners.45

Despite the image of Frankish exceptionalism promoted by William of Tyre, the courts of twelfth-century kings of Jerusalem were as diverse and multicultural as any other in the Levant. Royal dynasticism promoted close association with Greeks and Armenians while royal patronage acted as a magnet for indigenous professionals and servants, from medical doctors to artists and craftsmen. The brothers Kings Baldwin III and Amalric had an Armenian grandmother, Morphia, wife of Baldwin II, and a French father, King Fulk; both married Greek princesses (Theodora Comnena and Maria Comnena respectively). The court of Amalric attracted Arab and Jewish doctors, Syrian instructors in horsemanship and, in William of Tyre, tutor to the future Baldwin IV, a Jerusalem Frank possessed of the grandest elite western European academic training. This was not a new development. Baldwin I had employed local Syrian converts, and kings regularly patronised local Syrian Christian religious houses. Frankish Outremer was not hermetically sealed from either its non-Frankish subjects or neighbours. Cross-border alliances of convenience, even against fellow Franks, were not unknown. Aristocratic Muslims visited the Haram al-Sharif and the al-Aqsa mosque. The rebellious Count Hugh of Jaffa attempted to make common cause with the Fatimid garrison at Ascalon in 1134. The refurbishment of the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem c. 1170, whose bishop was born in England, was paid for by King Amalric and his father-in-law, the Byzantine emperor Manuel I, and included Greek mosaics with Latin inscriptions.

45. Front cover of the Melisande Psalter.

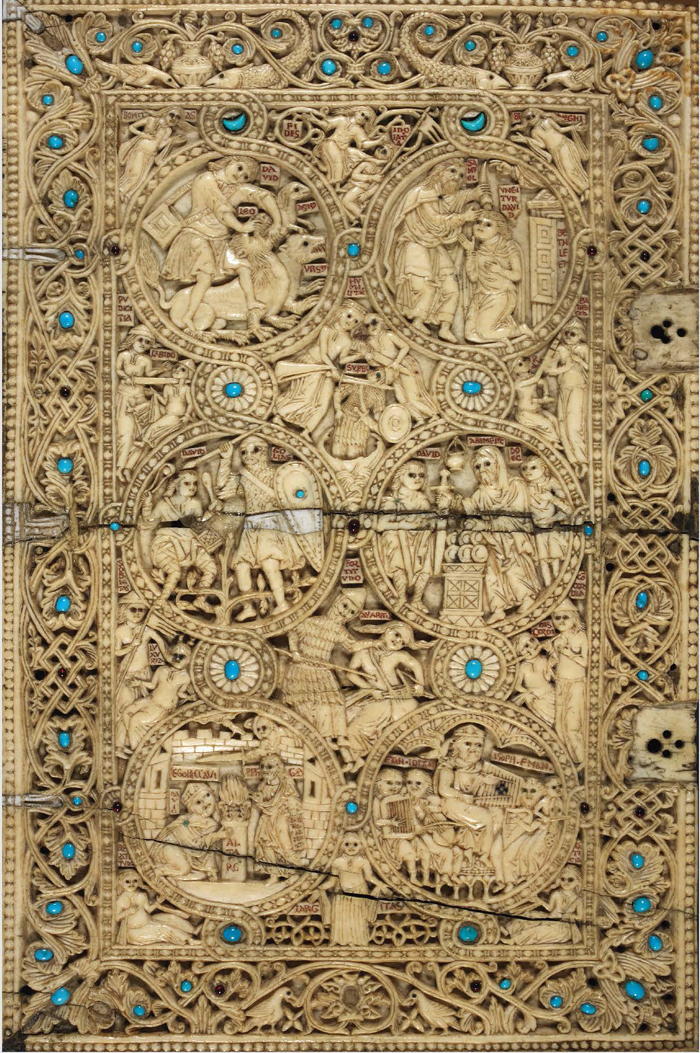

The so-called Melisende Psalter provides exquisite illustration of such cosmopolitan cross-cultural fertilisation. Produced between 1134 and 1143, probably as a special presentation volume from King Fulk to his wife Queen Melisende (the half-Armenian daughter of Baldwin II and heiress to the kingdom), the psalter, a diminutive book (22 cm x 14 cm) of over 200 folios, contains twenty-four illuminated scenes from the New Testament painted by an illustrator with the Greek name of Basilius; an English-style calendar of saints’ and commemoration days, including for Melisende’s parents King Baldwin and Queen Morphia, illustrated by a different artist with monthly signs of the Zodiac showing combined western European and Arabic influence; a copy of the Latin psalms written in northern French script, with a third illuminator contributing initial letters showing a hybrid Italian-Arabic style, possibly Sicilian; and, in the same hand as the psalms, prayers to nine saints, illustrated by a fourth artist who tried to incorporate Byzantine motifs into a western European style. The delicate Islamic-style geometrically designed ivory and gem-studded covers depict, on the front, scenes from the life of King David, and, on the back, a king (perhaps Fulk) performing the Six Works of Mercy from Matthew’s Gospel (feeding the hungry; giving water to the thirsty; clothing the naked; sheltering the homeless; visiting the sick; and visiting the imprisoned). Even the spine, decorated with Byzantine silk and the Greek crosses of the Jerusalem royal arms, breathes a mixture of eastern and western styles and the highest luxury. Probably created in workshops associated with the cosmopolitan Church of the Holy Sepulchre, the psalter bears striking witness to a fertile and eclectic congregation of international styles – northern French, English, Byzantine, Arabic, Islamic and Armenian – that cannot have been as unique as the psalter’s own survival. (It is now in the British Library.)43

46. Qal’at Sanjil, Raymond of Tripoli’s castle that remained in Frankish hands 1103–1289 and still stands today. A late nineteenth-century view.

CASTLES IN OUTREMER

Castles such as Crac des Chevaliers in Syria or Marienburg in Poland represent the largest, most iconic surviving relics of the crusades, symbols of military conquest and rule that lay at the centre of active crusading. This is appropriate, as fortified sites for aggression, defence and authority were central to the imposition and consolidation of political and social control, from the start of campaigns to the enforcement of continued civil power. In every region of crusader conquest – the Levant, Iberia, the Baltic or Greece – castles served a dual function as military bases and as focal points for the protection, subjugation or exploitation of local populations and resources. This merely extended to areas of crusading the use of castles familiar across western Europe from the tenth century onwards. Crusaders brought their expectations and technologies with them, while borrowing from local traditions, adapting existing fortifications, and developing their own innovative sophisticated designs and styles. Each region of conquest imposed distinctive patterns and features.

In Outremer, the earliest castles were simple towers, scores of which, of one or two storeys, were erected in the first fifty years of Frankish occupation, chiefly as centres of lordships in which to dispense justice, receive taxes and store renders. They were very much on the model of the Norman castles that festooned England after 1066, except that in Outremer the castles were of stone and were not constructed on artificial earth mounds (mottes) as in the west. The great nobles of the new Frankish principalities built their own large keeps, which could extend to substantial palatial complexes, in the cities from which they derived their power and wealth, such as Beirut, Tyre, Jubail or Jerusalem, where the king’s castle incorporated the existing Roman Tower of David. On arrival in the east, crusaders found local enclosure fortifications (castra), common across the eastern Mediterranean, which they adapted and copied as these provided relative ease of construction – walls surrounding a courtyard – and convenient shelter for local Franks, especially in remote areas such as Transjordan (Montreal from 1115 and Kerak from 1142), in frontier regions, such as southern Palestine where from the 1130s a string of castra ringed the Fatimid port of Ascalon (e.g. Ibelin, Darum and Gaza), or on suitable sites such as the small islet off Sidon. The Military Orders, whose wealth meant they began to take over most of the rural castles of all types from the mid-twelfth century, also built castra, essentially as fortified cloisters. Some enclosure castles also contained keeps (as at Darum and Jubail) or were surrounded by often extensive protective outworks (as at Ibelin). In the later twelfth century, additions to initial designs charted increased investment and the growing Ayyubid military threat; some fortified manor house complexes were thus transformed into regular castles (for example, Belmont near Jerusalem).

47. Crac des Chevaliers.

From these basic enclosure castles came the famous concentric castle design, simply one castra surrounding another, a double defensive system that echoed Byzantine fortifications such as the Theodosian walls of Constantinople familiar to successive generations of crusaders. The concentric design was pioneered by the Hospitallers at Belvoir, a hilltop site overlooking the Jordan valley and the road from Damascus to Jerusalem bought by the Order in 1168. Completed probably a decade or so later, Belvoir’s concentric design withstood Saladin’s forces for eighteen months to two years (1187–9) before the garrison surrendered once the outer defences had been penetrated; the inner walls were never breached. Belvoir provided a model for later thirteenth-century castle building in Outremer (such as the extensions at Crac des Chevaliers and Margat, both belonging to the Hospitallers) and in the west, notably a number of Edward I of England’s castles in Wales.

48. Belvoir.

Location and topography exerted as much influence on castle design as purpose, the contrasting settings of cities, coastal plain, hill country or desert determining salient features. Accessible hilltops, as at Montreal or Saphet in Upper Galilee, offered attractive sites, although more favoured were those naturally protected on three sides by deep river valleys or, in the case of the great fortress of Athlit, Château Pèlerin, built with the help of pilgrims and crusaders during the Fifth Crusade (1217–18), protected by the sea. Some of the largest and most imposing castles were built on such spurs of land, often in contested hill country or near vital trade routes: Crac des Chevaliers protecting the Homs gap behind Tripoli; Saone on the Latakia to Aleppo road; Margat on the coast road between Tortosa and Antioch. The Teutonic Order’s headquarters (1229–71) at Montfort in Upper Galilee was unusual in being an administrative capital not a strategic military post. Outremer’s eclectic castle system reflected varying Frankish needs: internal oversight of material possessions and the local population; political control; settler protection; ostentatious display of power; control of trade routes; extending areas of influence; and defence along flexible and porous frontier zones. The usefulness and flexibility of castles in different contexts was eccentrically if ingeniously confirmed by Richard I’s prefabricated wooden castle, Mattegriffon, which he brought with him from Sicily to the siege of Acre in 1191.46

As elsewhere, cost dominated the provision of castles in Outremer. Increasingly in the twelfth century and completely in the thirteenth, oversight, ownership and construction of castles became the preserve of the Military Orders who had access to resources beyond the means of the richest secular lords. The costs of construction and maintaining the Galilee Templar castle of Saphet, rebuilt from 1240, were huge: 1,100,000 gold bezants in the first two and a half years, and 40,000 bezants a year thereafter for a garrison of 50 Knights Templar, 30 sergeant brothers, 50 Turcopoles, 300 crossbowmen, 820 servants and labourers and 400 slaves, slave labour having played a necessary part.47 The garrison at Vadum Iacob had been of similar strength, while the complement at Athlit was around 4,000.

Behind their massive walls and extensive outer defences, achieved by extraordinarily skilled and ingenious feats of engineering in moulding the unforgiving landscape to their purposes, these large castles operated as homes and communities not just barracks. Internally, they were furnished, equipped with cisterns, kitchens, stables, dining halls, chapels, domestic quarters, and, at Belvoir at least, a bathroom. Inside walls were plastered and decorated with frescoes. Inside and out, the stonework and vaulting were finished to a high quality, not least the fine ashlar of the outer walls of most of the grandest castles. Yet despite their architectural sophistication and effective defensive designs, these castles could not survive indefinitely on their own resources. Without relief they were doomed to fall to determined attack, as their capture by Saladin and later Baibars and his successors showed only too decisively.48

Outremer did not become a cultural catalyst or melting pot. Inter-communal contacts remained circumstantial and superficial. Each community retained its sealed identity, regarding the others – if at all – as strange. The Arabisation of Syria and Palestine had taken centuries. The Franks never continuously occupied anywhere on the Levantine mainland for longer than 186 years (Qal’at Sanjil, the castle site of Mount Pilgrim outside Tripoli, 1103–1289). Some adopted habits of dress, eating, housing, even military tactics appropriate to the environment. Tancred of Lecce issued coins in Antioch portraying himself as an eastern potentate, bearded and perhaps wearing a headdress, possibly a turban. Loose-fitting clothes, veils, surcoats over armour, cool summer fabrics, furs for the cold winters were dictated by the climate. Some acclimatised Franks took to eastern cuisine, although others stuck firmly to a western diet, including pork. Archaeological evidence indicates that the constant stream of new arrivals from the west, as pilgrims or settlers, hardly helped raise the standards of health as they appear to have been generally poorly nourished and riddled with intestinal parasites. Some adaptation to local hygiene can be traced in Frankish maintenance of aqueducts, water cisterns and, in the Hospitaller castle at Belvoir overlooking the Jordan, a bathroom. Militarily, the Franks proved fast learners, coming to terms with Turkish field tactics by developing counter-measures in the delayed massed charge and the fighting march, where the cavalry was protected by flanking infantry. But the Franks did not copy their enemies’ mounted heavy and light archers or the battlefield feints.49 Despite their sustained military endeavours, by the 1180s, Outremer Franks could strike their western European contemporaries as exotic or dissolute, the Jerusalem embassy to Europe in 1184/5 being remembered by one hostile witness for its ostentation and attendant clouds of perfume, features that made it easier to blame the poulains, as the Franks were derisively known in the west, for the political and military setbacks and disasters that engulfed them.50