CRUSADES AND THE DEFENCE OF OUTREMER, 1100–1187

Twelfth-century Outremer stood at the extreme physical frontier of Latin Christendom while at the same time occupying a central space in Latin Christian thought, emotion and cosmology. One veteran of the First Crusade and a Jerusalem resident asked, rhetorically, why, despite overwhelming numerical superiority, the Franks’ enemies had failed to crush the newcomers: ‘Why did they not, as innumerable locusts in a little field, so completely devour and destroy us?’ Obviously because of the power and protection of God, but he added, alongside the Almighty, ‘we were in need of nothing if only men and horses did not fail us’.1 Faith and military reinforcements sustained Outremer as an intrinsic, familiar, if exotic, part of Christendom. The phrase ‘shouted aloud at the crossroads of Ascalon’ became a metaphor for common gossip, a twelfth-century version simultaneously of the Clapham omnibus and Timbuctoo, at once popular space and the ends of the earth.2

The Crusade of 1101

Even before the fall of Jerusalem in 1099, further armies were being prepared. In response to news of the success at Antioch and the crusaders’ pleas for reinforcements, new preaching campaigns were launched in Italy and France attracting backsliders who had failed to fulfil their vows of 1095–6; those eager to hop onto the bandwagon of success; and shamefaced veterans who had abandoned the 1096 expedition. With songs, letters and early narratives all unblinkingly emphasising the raw, violent physicality of the bloody victory of 1099 and material success, there was little abstract about the new appeal.3 There was talk of conquering Baghdad or Egypt.4 The heroics of 1097–9 seemed to confirm God’s favour and immanence and a turn in the tide of history. The subsequent dismal failures of the campaigns of 1101 served notice that such high ambitions were spiritually and practically unsound, setting a more restricted, realistic frame around future strategies for defending the new conquests.

While there had been no pause in contingents leaving for the Levant in the years after 1096, the promotional campaigns of 1099–1100 raised very substantial forces, in total perhaps as great as the armies of 1096. Among the leaders were Duke William IX of Aquitaine, Count William II of Nevers, Duke Odo I of Burgundy, Count Stephen I of Burgundy, Duke Welf IV of Bavaria, and even Conrad, constable to Urban II’s arch-enemy Henry IV of Germany. The regions of recruitment mirrored those of 1096. A Lombard army set off from Milan on 3 September 1100, reaching Constantinople in late February or early March 1101, to be met by Raymond of Toulouse, who had been Emperor Alexius’s guest since the previous year. By early June, northern French troops under Stephen of Blois, the Burgundians and Constable Conrad’s small German force had joined Raymond and the Lombards at Nicomedia on the Asiatic side of the Bosporus. Accompanied by the Milanese relics of the city’s patron Saint Ambrose and Raymond’s Antioch Holy Lance, the army’s religious identity did not prevent its Italian leadership deciding on the quixotic political priority of rescuing Bohemund, who had been in Turkish captivity in north-eastern Asia Minor since being defeated in 1100 by an army of Danishmend Turks while trying to relieve the Armenian city of Melitene in eastern Anatolia. Rejecting the advice of the First Crusade veterans to follow the glorified path of 1097, the army captured Ankara before breaking up under sustained Turkish assaults at Merzifon in early August, the leaders fleeing back to Constantinople, abandoning the infantry and non-combatants to massacre or slavery.

The pattern was repeated. The bulk of the other western armies arrived in Constantinople in June 1101. Leaving William of Aquitaine and Welf of Bavaria behind, William of Nevers immediately set out after the Lombard army. After reaching Ankara in mid-August, he changed course, turning towards Iconium (Konya) which he failed to capture. Pressing forward towards Cilicia, his army was destroyed by the Turks at Heraclea (Ereghli). Following an increasingly familiar scenario, the cavalry deserted the infantry, the leaders escaping to reach Antioch. A similar fate awaited William of Aquitaine. Setting out from Constantinople in mid-July along the 1097 route, in early September his army was also defeated at Heraclea, only some of its leaders, including Duke William, managing to flee to the coast or make it through to Syria. These disasters were not down to inadequate preparation or ignorance of local politics and conditions. Some accused the Greeks, most blamed the crusaders’ own sins, cover for over-optimism and incompetence. Despite Emperor Alexius providing material and logistical support, the experience of 1101 showed how difficult it was to sustain large armies in hostile terrain facing an undefeated united enemy. This highlighted the good fortune enjoyed by the First Crusade, gilding even further the lustre of the first Jerusalem journey.

Western Aid for Outremer

The failure of 1101 reshaped western responses. With the exception of what is now known as the Second Crusade (1145–8), subsequent armed assistance for Outremer before 1187 rested with smaller expeditions, whose numbers made travelling by sea possible, in rhythm with the increasingly popular bi-annual Levant marine passages of pilgrims and merchants. The timing of cross-Mediterranean sea travel was regulated by the prevailing Mediterranean winds and currents, which effectively restricted access to spring and autumn. Such military tours, usually lasting months not years, were attuned to the incremental needs of the Franks of Outremer not cosmic strategy. Occasionally, direct Outremer appeals elicited wider efforts at western recruitment, as during the crisis after the defeat and death of Roger of Antioch at the battle of the Field of Blood in 1119, which led to the Venetian crusade of 1122–4 and the capture of Tyre (1124); or in 1127–9, with the recruitment of an army to attack Damascus coinciding with the arrival of Count Fulk V of Anjou to become the future king of Jerusalem. Other expeditions appeared more speculative, offering service to whatever project the rulers of Outremer had in hand. In 1110, as part of an extended Mediterranean progress that took in Byzantium as well as a pilgrimage to the Holy Sepulchre, King Sigurd of Norway was persuaded to join Baldwin I’s siege of Sidon. Reputation came from physical presence in the Holy Land. Sending sums of money hypothecated on some future promised expedition instead, as Henry II of England (a grandson of Fulk V of Anjou through the count’s first wife and so the nephew of Kings Baldwin III and Amalric) discovered, earned few plaudits.5

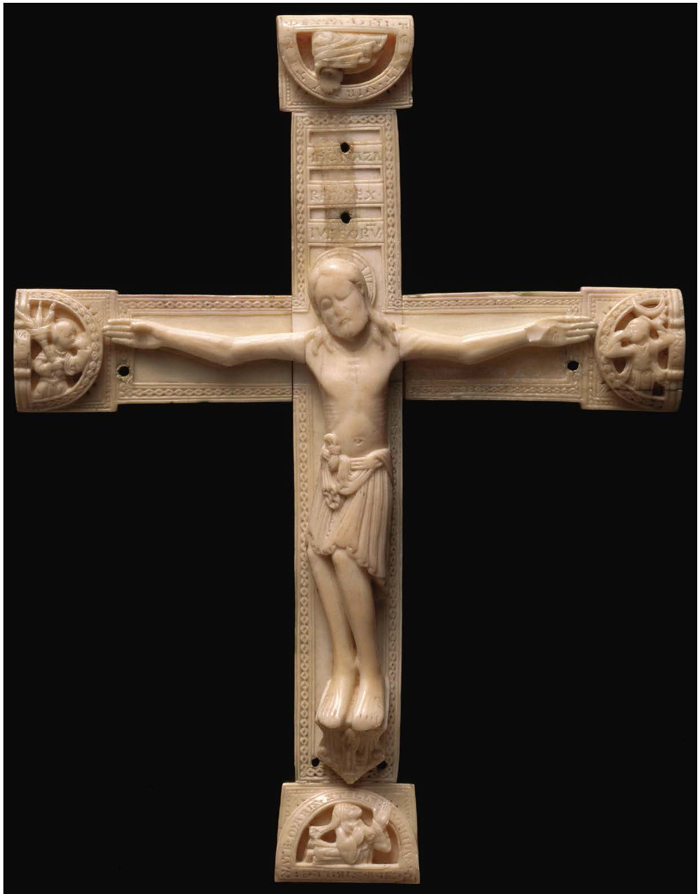

49. Countess Sybil of Flanders’s cross. She settled in Jerusalem 1157–65.

The roll call of visiting western luminaries testified to the status a Jerusalem veteran could hope for back home: Eric I of Denmark (1102–3, though he died in Cyprus before reaching Palestine); Sigurd of Norway (1107–10); Charles of Denmark (1111, nephew of the First Crusade commander Robert II of Flanders and a future count of Flanders himself); Conrad of Hohenstaufen (c. 1124, the future Conrad III of Germany and leader of the Second Crusade, the only European crowned head to campaign twice in the Holy Land itself). Some, like Conrad, made more than one trip: Fulk V twice (1120 and 1128); Count Hugh I of Troyes thrice (1104–8, 1114, 1125); Count Thierry of Flanders four times (1138, 1147, 1157 and 1165); his son Philip twice (1177–8 and 1190–1). Crusading ran in families, such as the dukes of Burgundy; the counts of Flanders, Burgundy, Blois-Champagne; the Italian Montferrats or the English Beaumonts; or the minor French comital houses of Montléry, le Puiset, Lusignan, Brienne or Joinville and the upwardly mobile English Glanvills. The prestige of a Holy Land campaign reflected the glamour that clung to the heroes of 1096–9 whose reputations had quickly been transformed into legend. Those left out of the glory of the First Crusade appeared eager to gain some post hoc association, which may explain why Philip I of France, excluded by excommunication from a role in 1096, allowed his daughter Constance to marry Bohemund, the son of a parvenu Norman adventurer, during his 1106–7 tour recruiting for a new eastern enterprise. Such was Bohemund’s fame, witnessed by his starring role in the earliest narratives of the First Crusade, that men apparently flocked to get him as godfather to their children and Henry I of England had to ban him from entering England lest he signed up too many Anglo-Norman lords for his new via Sancti Sepulchri (in fact an invasion of the western Balkans designed to topple Alexius I, an expedition that met with dismal failure in 1108).6 Bohemund’s reputation survived failure, giving his name (originally a nickname; his baptismal name was Mark) to six successors as princes of Antioch and earning him a distinctively eastern-style domed mausoleum over his tomb at Canossa in Apulia that may have been designed to evoke the Holy Places. These micro-crusades helpe shape a tradition. Despite persistent uncertainties over crusaders’ privileged entitlements, by the 1120s taking the cross had become familiar.7 In the early years of the settlement, there was always some necessary campaigning on offer, to defend or expand the frontiers. This in turn attracted more permanent recruits in the shape of the Military Orders.

The Military Orders

50. Bohemund’s tomb, Canossa, Puglia, Italy.

The Military Orders provided crusading’s most original contribution to the institutions of medieval Christendom. Their combination of charitable purpose, religious discipline and armed violence tapped into aristocratic mentalities of aggressive piety and anxious self-justification. Their defining visual as well as institutional images of militancy, charity and the cross, as displayed for example on Templar seals, expressed the complexity of Christian teaching on the crusades. In retrospect appearing a logical extension to the militant religiosity that produced the First Crusade, originally the Military Orders were products of the circumstances of the Frankish enclave in Palestine and the plight of the increasing numbers of visiting pilgrims. After 1099, the countryside around Jerusalem and roads from the coast remained unsafe, especially for unarmed pilgrims now arriving in large numbers. In 1119 a group of pious knights, already attached to the canons of the Holy Sepulchre, established a formal confraternity to provide military protection for pilgrims to Jerusalem and Jericho. Led by Hugh of Payns from Champagne and Godfrey of St Omer in Picardy, these knights followed the canons’ rule, swearing vows of chastity, poverty and obedience, and depended for income on alms. Recognised by the Council of Nablus (1120) and licensed by the patriarch of Jerusalem to defend pilgrims in return for remission of their sins, the knights were given quarters at the royal palace in the former al-Aqsa mosque on the Temple Mount (Haram al-Sharif), known to the Franks as the Temple of Solomon. After the king moved across the city to the Tower of David a few years later, the knights took over the whole al-Aqsa site as their headquarters, providing them with their resonant name, the Order of the Temple of Solomon, Templars for short. After a successful European recruiting tour in 1127–9, Hugh of Payns received recognition of his Order at the Council of Troyes (1129), confirmed by subsequent papal privileges, and enshrined in a detailed rule. Lingering, and never wholly suppressed, disquiet at such a blatant confusion of the spiritual and the material, of the profession of a regular canon with that of a knight, elicited a famous polemical apologia from the leading preacher, pastoral theologian and ecclesiastical publicist of his day, Bernard of Clairvaux’s De laude novae militiae (In Praise of the New Knighthood, c. 1130). This wove traditional motifs of Christian self-sacrifice, martyrdom and salvation together with a conveniently radical refashioning of St Paul’s spiritual metaphors for fighting for Christ into literal exhortations to physical warfare for the faith, in Bernard’s catchy phrase, the Templars transforming sinful warfare, malitia, into God’s militia.8

51. Templar seal.

52. The al-Aqsa mosque, headquarters c. 1119–87 of the Templars.

The Templars proved immediately popular, attracting international recognition, recruits and patronage in Outremer and across western Europe. Visiting pilgrims and crusaders could become temporary confratres (as did Fulk of Anjou on his first trip in 1120). Others joined permanently, some after long secular careers, bringing with them lucrative donations and further networks of family contacts. Rapidly, from the 1120s, the Templars built up a large pool of patrons and estates across western Europe as well as the Levant, supplying Outremer with troops and external funding, as a proportion of profits from Military Order holdings in the west was sent to the east. This cross-Mediterranean presence led to the Order becoming used by crusaders and others as bankers. By the time of the Second Crusade, the Templars were providing loans, military advice, leadership and a de luxe hotel service for western crusaders. In places, the Templars created lasting physical symbols of their calling in building round churches on their property, evoking the Holy Sepulchre or the al-Aqsa in towns and countryside across western Europe. Within Outremer, the Order was soon manning forts and castles, especially to protect strategic roads, as well as providing a standing military regiment.

53. Templar round church, Tomar, Portugal.

The Order of the Hospital of St John began with a pilgrim hospice in Jerusalem founded in the early 1080s to cater for pilgrims and funded by Amalfitan merchants. In common with hospital institutions across western Christendom, the laymen who ran the hospital assumed the character of a religious community, with nursing as their vocational duty. After 1099, under its administrative head Gerard, the hospital and its community attracted lavish donations from local rulers and western patrons and, in 1113, recognition and protection from the pope. By the 1120s, the hospital had acquired extensive estates in Italy, Catalonia and southern France as well as lands and rents across Outremer. The Jerusalem hospital grew into a huge business, with hundreds of beds for patients of all religions and both sexes, providing a social service for exhausted and sick pilgrims, the local community, pregnant women, abandoned children and the destitute. Nursing remained an obligatory vocation for all brothers of the Order. Early military association may have come from its provision of field hospitals on military campaigns. The Order’s lay religious brotherhood may have acted as the model for the early Templars. The debt was soon reciprocated when the Hospitaller Order assumed direct military functions. As an increasingly well-funded private institution, a wider social and political role in cash-strapped Outremer was almost inevitable. In 1126 members of the Order were made responsible for units in the Jerusalemite army that attacked Damascus. In 1136 a castle built at Bayt Jibrin to resist raids from Ascalon was assigned to the Order, possibly the second to be so assigned. By the 1140s, the Order appears to have become militarised on the lines of the Templars, in the process becoming more aristocratic in recruitment, although not abandoning the formal obligation of nursing. With their military function came further responsibilities for manning (and funding) castles. The Jerusalem hospital continued providing an ecumenical service to the whole community, its local importance transcending politics as well as religion: apparently Saladin allowed ten Hospitaller brothers to continue to tend the sick in the hospital for a year after his capture of the city in October 1187.9

The two Jerusalem Military Orders became leading political players in Outremer (and, indeed, the west). Although frequently at odds with each other, the Orders featured prominently in deciding military strategy. Jurisdictionally independent of all except the distant papacy, they could act as supposedly neutral arbiters in politics and financial management. As the costs of defence rose, decreasingly matched by the resources of the crown and local secular nobility, the Orders’ power and influence increased as they controlled more castles and frontier military sites.10 By the 1180s, the combined Templar and Hospitaller contribution of around 700 knights to the full muster of the kingdom of Jerusalem was roughly equal to that from all other sources. The Orders grew into large international corporations, their fighting knights an elite minority, supported by military sergeants, clergy, lay officials, servants. Some professed knights were more estate managers than warriors. There were even groups of nuns who wished to be attached to the Orders. Effective in channelling funds, faith, recruitment and property management, the Orders prompted imitation. As efforts to conquer Muslim al-Andalus gathered pace, local Iberian Military Orders were founded: Calatrava (Castile, 1164); Santiago (León, 1170), Alcantara (Castile, 1176) and Avis (Portugal, c. 1176). Within Outremer, the Order of Lazarus (1130s) was modelled on the Templars, mainly attracting knights with leprosy; in 1198 the hospitaller Order of St Mary of the Germans, founded at Acre in 1190, was militarised under a Templar-style rule, later known as the Teutonic Knights; so, in 1228, was the English Order of St Thomas of Acre, originally founded for canons in 1190/1. The institutional alliance of mission, holy war, ecclesiastical exemption and religious discipline proved popular on Christendom’s northern frontiers, with the Swordbrothers of Livonia (c. 1202) and the Prussian knights of Dobrin (Dobryzn, c. 1220).11

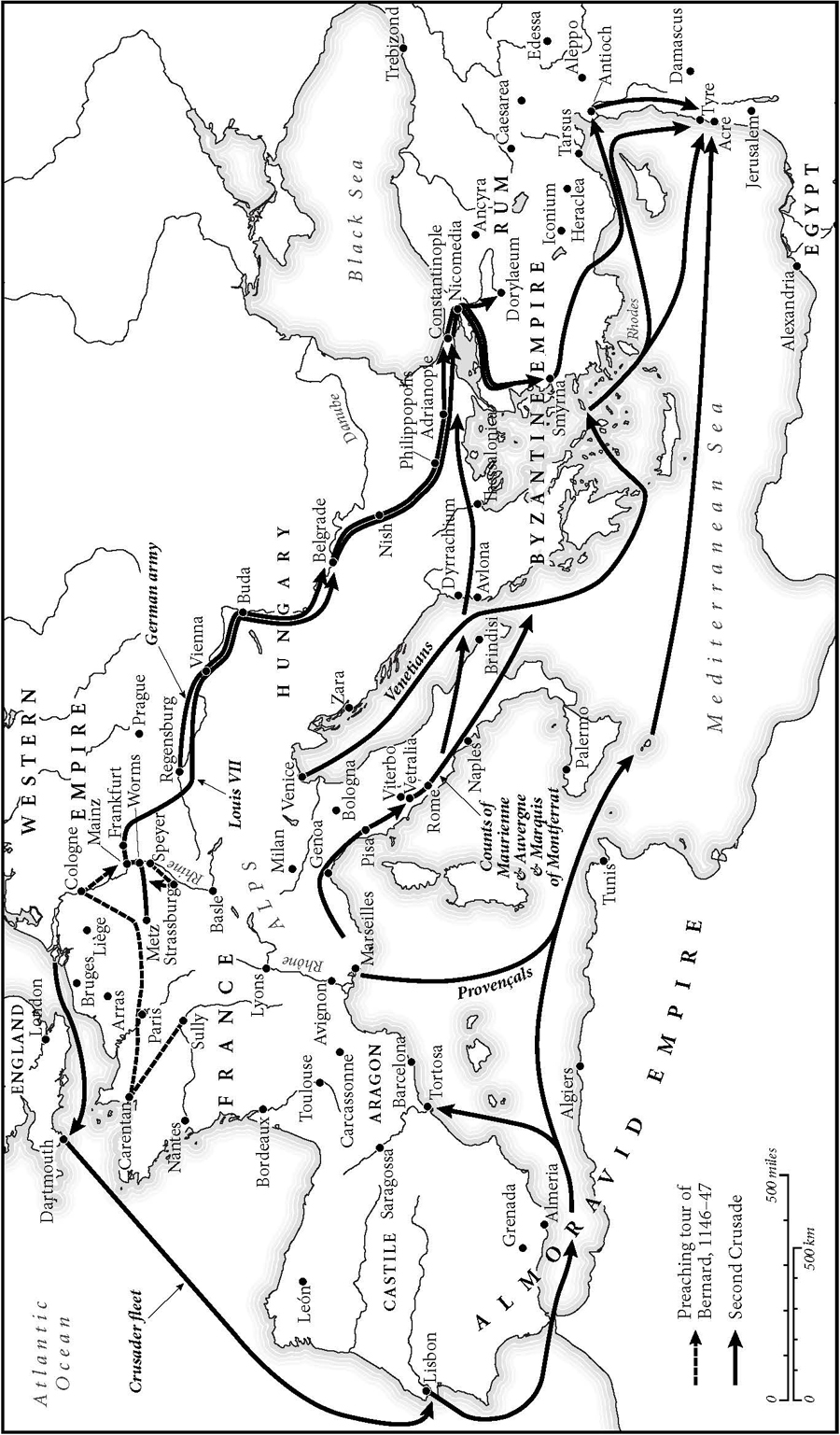

7. The crusades of 1122–48 and the Second Crusade.

Members of the Military Orders were not technically crucesignati. As brothers they did not take the cross, and, except for the temporary confratres, their commitment, like a monk’s, was for life. However, they shared the crusader’s purpose, idealism and spiritual privileges. They also shared a social and cultural milieu. Involvement in crusading and the Military Orders often ran in tandem through families. As striking, the Orders left tangible and lasting memorials to crusading, in castles and fortified headquarters in the east, in Iberia and the Baltic and, across western Europe, in their round churches evoking Jerusalem, the remains of their religious houses and manorial properties, or the preserved names of the places and estates they owned: the Rue du Temple in Paris; the Temple Church, St John’s Gate, Knightsbridge, and St John’s Wood in London; Tempelhof in Berlin.

The Holy Land Crusades of the 1120s

The Venetian Crusade, 1122–5

A series of major crises in Outremer in the 1120s provoked the first concerted western military campaigns since 1101. Antioch was leaderless after the defeat and death of its prince, Roger of Salerno, at the Field of Blood in 1119. Baldwin II of Jerusalem, previously count of Edessa, acted as Antioch’s regent, having only assumed the crown after a divisive succession struggle following Baldwin I’s death in 1118. Baldwin II failed to impose as firm a grip on his factious nobles, some of whom still questioned his right to rule. Although attacks from Iraq had ceased after 1115, banditry and raids from the Fatimid garrison at Ascalon as well as the continuing threat from Egypt itself undermined security in the south, while in the north Aleppo and Damascus alternated between alliance and attack. Gloom was deepened by economic and environmental difficulties, such as earthquakes (1113, 1114, 1117) and plagues of locusts (1114 and 1117). The Jerusalem government appealed to the papacy and Venice for help. Pope Calixtus II responded by sending the doge of Venice, Domenico Michiel, a papal banner. The doge took the cross in 1122. The subsequent Venetian campaign (1122–5) demonstrated how enthusiasm for holy war operated in collaboration with a range of material and pious objectives while confirming the significance of sea transport’s increasing ability to convey substantial forces.

54. Relics of St Isidore taken by Doge Michiel during the Venetian crusade. Fourteenth-century mosaic, St Mark’s, Venice.

One Jerusalem witness put the Venetian fleet at 120 ships, carrying 15,000 Venetians and pilgrims, the latter presumably paying customers, and, significantly, for the first time, 300 horses. The fleet also carried timbers for catapults, ladders and siege machines, a precedent for future sea-borne expeditions.12 On their way eastwards, the Venetian crusaders plundered Corfu to put pressure on the new Byzantine emperor, John II Comnenus (1118–43), to confirm Venetian trading rights. The capture of Baldwin II by Balak, ruler of Aleppo, in April 1123 coincided with the fleet’s arrival at Acre. In May 1123 the Venetians decisively destroyed an Egyptian naval squadron patrolling the southern Palestinian coast, and captured Egyptian supply vessels with their cargos of weapons, siege timbers, gold, silver and spices.13 Except for the siege of Sidon in 1110, the Venetians had not previously played much of a distinctive role in Outremer, unlike Genoa and Pisa. Now they took the opportunity to gain a permanent stake in the increasingly lucrative Levantine trade. Over the winter of 1123–4 they negotiated a deal with the regency Jerusalem government for the capture of Tyre. In return for their assistance and a loan of 100,000 gold pieces to pay the Jerusalemite army, Venice would receive a third of the conquered city, free trade, legal autonomy, the use of their own weights and measures, and an annual tribute of 300 bezants. After a five-month siege, the Damascene garrison surrendered in July 1124. Returning to Venice in 1125, Michiel’s fleet terrorised its way through the Aegean and Adriatic, sacking cities and looting islands of booty and relics. The Venetians staked men, money and ships on a grand scale, a substantial investment risk from which they derived substantial capital return, holy relics and remission of sins: good business all round.14 The crusade’s benefits were material, enhancing Venice’s civic identity, not least in physical terms through the display of holy booty, such as the relics of St Isidore deposited in the treasury of the Cathedral of St Mark’s.

The Damascus Crusade, 1129

The capture of Tyre, the release of Baldwin II a few weeks later and the arrival in Outremer in 1126 of the heir to Antioch, Bohemund II, son of the First Crusade hero, seemed to promise greater stability. After besieging Aleppo in 1124 and defeating a Mosul army in 1125, Baldwin II now planned a major assault on Damascus, to follow raids towards the city in 1125 and 1126. An embassy sent to Europe in 1127, including the Templar leader Hugh of Payns, sought soldiers for the Damascus campaign; the securing of Fulk V of Anjou’s agreement to marry Baldwin’s heir, his eldest daughter Melisende; and papal recognition for the Templars. Crusaders came mainly from France: Champagne, Flanders, Normandy, Provence as well as Anjou, although equivocal evidence exists of Hugh recruiting in England and Scotland.15 Subsequent coordination betrayed inept strategic management. While Fulk arrived with the spring passage of 1129, Hugh, having to secure his Order’s recognition at the Council of Troyes in January, only reached Palestine months later, which may explain why Baldwin launched the attack on Damascus as late as November. The Frankish army penetrated to within ten miles of Damascus before bad weather, inadequate supplies, indiscipline among its foragers, and effective Turkish harrying tactics forced a retreat. One local chronicler stated that the Damascenes paid 20,000 dinars for the Franks’ withdrawal, with a promise of annual tribute to follow.16 If true, this was not what the western crusaders had come 2,500 miles to achieve. For Baldwin, while welcome, it would hardly shift the terms of Syrian politics decisively in his favour. Unlike the siege of Tyre, the Damascus campaign lacked the advantages of being able to invest the city closely from territory already held. Supplies, communication and mobility all presented predictable problems. Baldwin II’s political imperative to use the Damascus enterprise to assert his authority, newly upholstered by the presence of Count Fulk as an experienced heir, failed to mitigate the logistical shortcomings. Extending Frankish rule to the cities of the Syrian interior made political, strategic and economic sense. However, successful inland sieges usually came not by forced conquest but by military pressure producing political negotiation or diplomatic accommodation, as at Antioch in 1098, only taken through treachery. The Franks at Damascus faced an additional obstacle. A Damascene witness noted that the Turkish auxiliaries were eager to fight the Franks because they were infidels.17 The politics of the jihad soon became a public touchstone for the politics of Syria.

The Unification of Turkish Syria

The political history of Syria and Palestine between 1099 and 1187 is dominated by the successive conquests between 1127 and 1174 of Imad al-Din Zengi and his son Nur al-Din, which united inland Syria and the Jazira, followed by the incorporation of these lands between 1174 and 1186 into the empire of Saladin, sultan of Egypt, prior to his annexation of most of Outremer in 1187–9. The reordering of the politics of the region was furthered by Saladin’s suppression of the Fatimid caliphate in 1169–71. In 1187, for the first time in over two centuries, the great cities of Mosul, Aleppo, Damascus, Jerusalem, Alexandria and Cairo, as well as the Holy Places of the Hijaz, acknowledged the same overlord.

Zengi, atabeg of Mosul in 1127 and Aleppo in 1128, with a deserved reputation for ruthlessness and brutality, had extended his power on both sides of the Euphrates and southwards towards Damascus. In 1144 he captured Frankish Edessa, the dismemberment of the principality completed by his son Nur al-Din in 1151. After Zengi’s assassination in 1146, Mosul and Aleppo had been divided between his two sons, only reunited under his second son, Nur al-Din of Aleppo (1146–74) in 1149. In 1154, Nur al-Din finally occupied Damascus. Both Zengi and Nur al-Din chipped away at neighbouring Frankish territory, especially in the north. After his victory over Prince Raymond of Antioch at Inab in 1149, Nur al-Din threatened Antioch itself and symbolically washed in the Mediterranean to signal the wider Muslim advance. The implosion of the Fatimid regime in Egypt in the 1160s drew Nur al-Din to send his Kurdish general Shirkuh to annex the country, in competition with the Franks of Jerusalem. Victory in 1169 left Shirkuh’s nephew Saladin as sultan and, although nominally subject to Nur al-Din, de facto ruler, a position he consolidated by abolishing the Fatimid caliphate. On Nur al-Din’s death in 1174, Saladin moved quickly to control Damascus, then dispossess or subjugate Zengid and other rulers in Syria, Aleppo submitting in 1183 and Mosul in 1186. Despite a few forays against Outremer, and a few successes, such as at Jacob’s Ford in 1179 (see ‘A Day at Jacob’s Ford’, p. 128), only after commanding the united resources of Egypt, Syria and the Jazira did Saladin move to conquer Outremer.

55. Saladin, a contemporary image.

It has become common for the unification of Syria, Egypt and Palestine in the twelfth century to be ascribed to a Muslim religious revival. The First Crusade had attracted a call for jihad from a Damascene religious scholar ‘Ali ibn Tahir al-Sulami (d. 1106), who regarded it as part of a general Christian assault on Islamic lands stretching from Iberia and Sicily to Syria, its success attributed equally to Muslim political divisions and the abandonment of the tradition of jihad. This embraced both the military struggle against infidels (al-jihad al-asghar or lesser jihad) and the more important inner contest against enemies of the soul (al-jihad al-akbar or greater jihad): ‘Put the jihad against your souls ahead of the jihad against your enemies, for truly your souls are greater enemies to you than your human enemies.’18 The association of politics with religion became standard among twelfth-century Arabic commentators on the wars in Syria and Outremer, although some preferred more temporal analyses of greed and danger. Whatever their private commitment, Zengi, Nur al-Din and Saladin each proclaimed their status as leaders of the jihad. However, the alleged Muslim revival might more accurately be described as a process whereby successful Turkish and Kurdish warlords harnessed suitable strands of Muslim law and theology to bind the administratively vital indigenous judicial, academic and bureaucratic elites, the ulema, to accept their usurping rule. In 1130, Zengi’s announcement of a jihad against the Franks concealed his designs on Muslim Hama and Damascus.19 Almost six decades later, Saladin was accused of similar dereliction of duty in his persistent campaigning against fellow Muslims, not the Franks.20

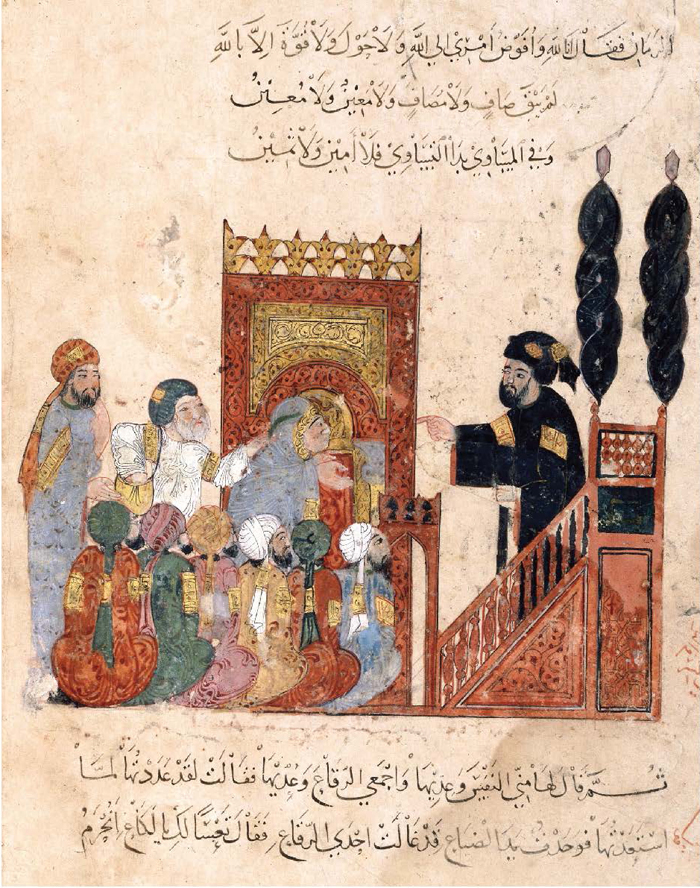

Following Seljuk precedent, conquest came hand in glove with lavish investment in religious institutions and promotion of the parvenu rulers’ Islamic credentials, Koranic virtues and deferential lip-service to the Abbasid caliphate. However, as mujahidin, these rulers could also distinguish themselves from their increasingly ineffectual Seljuk or Arab predecessors. Fostering good relations with the members of the ulema such as Saladin’s influential minister, the Palestinian writer, lawyer and poet al-Fadil (1135–1200), granted thuggish warlords respectability.21 This process was supported by endowing religious schools, madrasas, that offered employment for educated civilians and military nobles alike. New Turkish and Kurdish rulers built their regimes on war, wealth, patronage and propaganda but also on indigenous administration, justice and accommodation of diversity. Madrasas were visible symbols of this alliance, prominently situated within major urban centres, such as Damascus. Unlike their Frankish conquerors, the unifiers of Muslim Syria respected local interests, where convenient, allowing a patina of continuity to cover new regimes. In 1136, after capturing Ma’arrat al-Numan from the Franks, Zengi restored property to owners who had been dispossessed by the Franks in 1098 or their heirs, their title checked against the Aleppan land tax archives.22 The political use of religion rested on theological and scholarly trends in west Asian Islam stimulated by uncertain political legitimacy and lent focus by the Frankish occupation’s creation of an influential body of vociferous refugees. The Seljuks’ patronage of madrasas in Iran and Iraq had encouraged the identification of religion, politics and social community, emphasising conservative Sunni textual tradition in the study of the Koran and the hadith (sayings of the Prophet), rather than innovative philosophy or natural science. In a parallel investment in religious study, some schools were founded in early twelfth-century Shi’ite Fatimid Egypt, perhaps to combat the influence of the Christian Copts.23 Scholarly promotion of uniformity through madrasas helped rulers counter political dissent and encourage identity between the nomadic warrior Turkish lords and their settled subject peoples, with, in Syria, the Franks providing a convenient rhetorical focus of threat.

56. Teaching in a mosque.

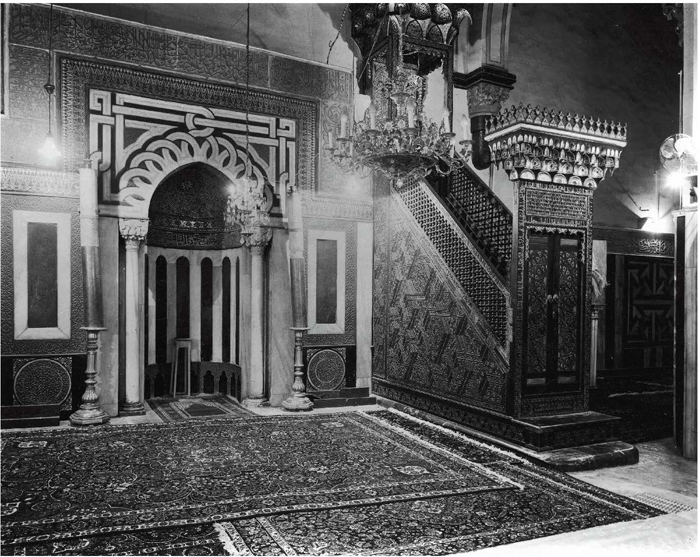

Inscriptions even before his capture of Edessa in 1144 praised Zengi as ‘tamer of the infidels and the polytheists, leader of those who fight the holy war, helper of the armies, protector of the territory of the Muslims’, all rather far from the reality: the early Seljuks and other Turkish rulers adopted a rather relaxed adherence to Islam, retaining many aspects of steppe culture.24 By contrast, Nur al-Din, seemingly a man of sincere private piety, went further, hugely increasing the number of madrasas in his lands, many with personal endowments.25 In 1168 he commissioned a pulpit (minbar) in Aleppo decorated with exhortations to jihad, which was intended for the al-Aqsa mosque once Jerusalem was recovered. It was, by Saladin, in November 1187.26 The recovery of Jerusalem became a symbol for spiritual as well as political renewal, a theme exploited by Saladin and his propagandists, particularly once that goal had been achieved. The courts of the Zengids and Ayyubids (namely Saladin, son of Ayyub, and his family) were staffed with members of the ulema steeped in the new orthodoxy; at Nur al-Din’s court Ali ibn Asakir (1105–76), the leading scholar of his generation, also collected hadith on the jihad; another of Nur al-Din’s civil servants, the Iranian Imad al-Din Isfahani (1125–1201), had taught in a Damascus madrasa, later becoming Saladin’s secretary and biographer. The Iraqi Beha al-Din ibn Shaddad (1145–1234), a noted legist, taught in madrasas in Mosul and Baghdad and, among other works, composed a monograph on jihad; hired by Saladin in 1188 as judge of the army, he repaid the compliment by writing a flattering biography of the sultan showing him in the best light of a Koranic mujahid as befitted his honorific title Salah al-Din, ‘Righteousness of the Faith’.27

57. Nur al-Din’s minbar in the al-Aqsa before its destruction in 1969.

Jihad provided a legitimising cause as part of the wider promotion of Koranic Islamic virtues, what has been described as a ‘recentring’ rather than a revival.28 Enthusiasm for armed jihad, as distinct from the habitual round of regional warfare, was not a creation of the Zengids. They merely took advantage of a vocal minority within the educated elites, reinforced by articulate refugees at Iraqi and Syrian courts with carefully preserved memories of crusade atrocities such as the massacre at Ma ‘arrat al-Numan in 1098. Territorial competition became rebranded as religious war. Jihad proved especially significant for Saladin. The Zengids were Turkish nobility, with experience of rule stretching back to the reign of Malik Shah, when Zengi’s father was governor of Aleppo. The Kurdish Ayyubids were upstarts, mercenary generals who traded their military service under the Zengids for political power, beginning with Saladin’s father Ayyub’s appointment as governor of Baalbek by Zengi in 1139. Saladin himself owed his position to his role as his uncle Shirkuh’s lieutenant in the conquest of Egypt in 1168–9 under the nominal suzerainty of Nur al-Din. Helped by a remarkable series of convenient (and not necessarily coincidental) deaths – Shirkuh in 1169; the twenty-two-year-old last Fatimid caliph al Azid, 1171; Amalric of Jerusalem, 1174; Nur al-Din, 1174, and his teenage son al-Salih of Aleppo, 1181 – Saladin imposed his family’s rule in Egypt and abolished the Shi’ite caliphate in 1171, cloaking usurpation with the aura of a Sunni champion. Careful to pay formal obeisance to the Abbasid caliph, between 1174 and 1186 Saladin swept aside the Zengids in Syria and the Jazira through force, bullying, bribery, patronage and diplomacy, drawing to himself and his family the adherence both of the civilian ulema and the mercenary regiments, the askari, on whom political control depended. Across Egypt and Syria, Saladin methodically placed his relations in control of key economic, fiscal, military and administrative resources through grants of political office and tax revenues (iqta). A conquering parvenu with no legitimacy beyond his own agency, Saladin needed to demonstrate his religious credentials to rule through the overt performance of Koranic models: public ritual piety; puritan domestic simplicity; strict but merciful legal judgement; generosity in finance, charity and patronage; dedication to the culture of jihad. Regardless of Saladin’s private beliefs, and it might be noted that Nur al-Din founded many more religious schools than he did, politics required such behaviour.

Saladin’s empire also relied on fresh conquests to consolidate new alliances and reward new followers. The Franks presented unique adversaries. Totems of enmity for the revived Islamic seriousness, they were immune to Saladin’s usual carrot-and-stick tactics of annexation. Legally, Saladin could only agree temporary truces with the infidel. Politically he had nothing to offer, as the Franks could not submit to his overlordship. Mortal confrontation was therefore inevitable, encouraging the presentation of power politics as jihad. Thus, the presence of the Franks ideologically as well as materially assisted Syrian unification and the development of the strong Muslim militarised polities of the Zengid and Ayyubid Empires.

The Second Crusade, 1145–8

The Franks’ greatest opportunity to contest Syrian unification came in response to Zengi’s serendipitous capture of Edessa in December 1144. Although leading to no immediate assault on the rest of Outremer, as Zengi turned his attention to policing his existing conquests, the loss of Edessa and the Franks’ failure to retake the city in 1146 presented a strategic and moral blow, exposing the lack of providential certainty in the Franks’ occupation. The political context was confused. The deaths of Fulk of Jerusalem and John II of Byzantium in hunting accidents in 1143 were balanced by a Mosul revolt against Zengi in 1145, his murder in 1146, and the division of his empire between his sons. In 1145 the new Byzantine emperor, Manuel I (1143–80), received the homage of Prince Raymond of Antioch (r. 1136–49), who otherwise stood to gain most by a new crusade in northern Syria. Jerusalem was adjusting to the uneven joint rule of the widowed Queen Melisende and her teenage son Baldwin III (1143–63). Any substantial crusader intervention in Syria threatened to undermine Byzantine interests there, as would the involvement of Sicily and Germany, rivals to the Greeks in Italy. Equally, Byzantium saw no advantage in disturbing relations with Muslim neighbours, while wariness of western motives had grown since the First Crusade, with Antioch remaining a source of potential conflict. The diplomatic bouillabaisse was thickened by the precarious position of Pope Eugenius III (1145–53). Elected in February 1145, after his predecessor had been killed in street fighting in Rome, overshadowed in Italy by rivalry between Sicily, Germany and Byzantium, Eugenius’s decision to follow Urban II’s precedent in calling for a mass redemptive military campaign to the Levant operated, as had the 1095 appeal, as part of a policy of consolidating papal influence and authority.

Eugenius’s letter calling for a new crusade, Quantum praedecessores (‘How much our predecessors’), was framed by the glorious memory of the First Crusade. While citing the loss of Edessa as the specific casus belli, Eugenius repeated Urban II’s formula of the urgency of help for the ‘eastern Churches’, perhaps as a sop to Byzantium, but certainly in evocative imitation of the 1095 call with its implicit claim of papal responsibility for the universal Church. Urban’s precedent was again cited for the grant of remission of sins, while papal authority was invoked in offering the crusaders’ temporal privileges, fully described for the first time with reference to a Holy Land campaign.29 Initial response was muted, and the bull, first sent in November 1145, was reissued in March the following year. The call was first taken up at Christmas 1145 by Louis VII of France, who may already have been toying with an eastern expedition of his own, but preaching and recruitment only gained momentum with the involvement of the pope’s mentor Bernard of Clairvaux and the network of his Cistercian order of monks, of which Eugenius had been a member (see ‘Bernard of Clairvaux’, p. 170). Thereafter, in contrast to 1095–6, the pope played a secondary role, easing diplomatic contacts and issuing bulls in response to requests to extend crusaders’ privileges to campaigns in northern Spain and the Baltic. Conrad III of Germany admitted to the pope that he had taken the cross (from Bernard at Christmas 1146) ‘without your knowledge’.30 Although he attended Louis’ ceremonial departure from St Denis near Paris in June 1147, Eugenius left set-piece exhortations and the necessary grind of promotional touring to others, especially his old tutor, the charismatic Bernard.

Recruitment for the new venture probably outstripped that for the First Crusade, the consequence of careful orchestration between the papally authorised preaching campaign of Bernard and the Cistercians and the commitment of the kings of France and Germany and leading regional nobles, such as the counts of Flanders, Champagne, Savoy and Toulouse and the duke of Bavaria. A series of high-profile theatrical assemblies, at Bourges (December 1145), Vézelay (March 1146), Speyer (December 1146), Etampes (February 1147), Regensburg (February 1147) and Frankfurt (March 1147) established domestic support for two monarchs whose authority was otherwise limited or contested. Crusade leadership paid political dividends; for Louis VII it provided the first instance of a French king commanding a large national army on an international campaign since the 870s. Recruitment stretched from Languedoc to the eastern marches of Germany, from the North Sea to Tuscany, pulling in urban elites as well as rural lords, knights, merchants, soldiers for hire, townspeople, artisans, men and, to the misogynist disgust of clerical critics seemingly after the event, women. Recruits included at least two who were dumb from birth.31 Local habit, family connections, dynastic traditions and political convenience were again as instrumental as inspirational oratory. Bernard set a tone of general religious revivalism. Already a champion of the Templars and an enthusiast for redemptive holy war, he argued that the crisis in Outremer provided a unique opportunity: in serving the ‘cause of Christ’, to paraphrase St Paul, ‘to conquer is glorious, to die is gain’ (cf. Philippians 1:21): win win.32

Bernard’s success cast him as the victim of aggressive stalking by audiences who identified in him Christ-like qualities.33 Other preachers were less fastidious. One, a Cistercian called Radulph, thrilled crowds in the Rhineland during the summer and autumn of 1146 preaching against ‘the foes of the Christian religion’, including local Jews.34 Popular anti-Judaism faced equivocal church policy. At almost the exact time Radulph was stirring up racial hatred, Abbot Peter the Venerable of Cluny was writing to Louis VII comparing the Jews of Europe unfavourably to Muslims, regarding their presence in Christendom as polluting and calling for them to be punished, short of actually killing them. Anti-Jewish riots and murder accompanied crusade recruitment in eastern France and central Europe as well as those encouraged by Radulph in the Rhineland. Ecclesiastical and secular protection appeared to be more effective than in 1096, with violence, though extreme, less widespread or concerted. Bernard’s main concern was that Radulph had preached without licence. Crusading was popular in the Rhineland where some, perhaps many, resented what appeared to them the privileged status of the Jews, protected by the king, wealthy bishops and rich lords, enjoying financial benefits while poorer crusaders plunged into debt. Eugenius III had forbidden crusaders access to Jewish credit in Quantum praedecessores if they wished to enjoy immunity from interest. The theological refinement of protecting those proclaimed by the Church as the oldest enemies of Christ may have been lost on those summoned to avenge the insult to Christ in the east. To the authorities the disturbances constituted acts of civil disobedience, unwelcome distractions to crusade planning. Radulph was silenced by being returned to his monastery; the agitation subsided.

BERNARD OF CLAIRVAUX AND THE CISTERCIANS

The influence of Bernard of Clairvaux (1090–1153) on the development of the ideology and practice of crusading ranks in significance beside that of Urban II and Innocent III. An early recruit (1113) to the new austere Cistercian monastic order (founded in 1098 at Cîteaux in Burgundy), from his position as abbot of Clairvaux, which he founded in 1115, Bernard became the dominant pastoral voice in western Christendom, promoting a distinctive theological message of intense spirituality and direct personal religious commitment. A spare, ascetic, charismatic figure, he pursued his advocacy of monastic rigour and the need for the laity to abandon luxury and materialism to transform their lives and secure salvation through his writing, preaching, public debate, political lobbying and formidable administrative skill. Coming from minor Burgundian nobility, he saw the potential of crusading and the new Military Order of the Templars in his programme of devotional renewal. In the 1130s his treatise De laude novae militiae (In Praise of the New Knighthood), composed in support of the Templars, decisively transformed the metaphorical New Testament language of spiritual conflict, such as employed by St Paul, into unequivocal religious justification of literal physical warfare in defence of the Christian faith, a task that invited salvation, the malitia of secular war transmuted into the militia of Christ. Bernard’s appeal combining spiritual and physical Christian militancy became central to the promotion campaign he led for the Second Crusade (1145–8). Recruited by his former pupil and fellow Cistercian Pope Eugenius III, his sermon at Vézelay at Easter 1146 to the French king and nobility, despite leaving no surviving record of what Bernard actually said, became iconic, as did stories of the power of his preaching and associated miracles. His orchestration of publicity, sustained by sending letters and well-briefed agents to those regions he could not visit personally and his use of the growing network of Cistercian monasteries, became a model for future organisers, as did the message he projected. His letters read like sermons, repeating central themes of vengeance, reward, duty, redemption and amendment of life. Despite the failure of the Second Crusade, acknowledged in Bernard’s own pained apologia De Consideratione (1149/52), his underlying emphasis on the crusader’s personal responsibility to and relationship with Christ and the cross became standard features of the preaching of subsequent crusades. Any squeamishness at the elevation of Christian violence was swept away as much by Bernard’s intense conviction, clarity of argument, vitality of imagery and power of rhetoric as by his startling reworking of scripture. The concentration on personal spiritual commitment in the context of communal religious responsibility sharpened the evangelic force of recruitment while allowing for the easy accommodation of different terrestrial military objectives. In 1147 Bernard himself authorised the application of crusade privileges to that summer’s campaigns against the Slavs in the southern Baltic, even suggesting that the pagans ‘shall either be converted or wiped out’, an extreme and canonically precarious view of Christian militancy.35

58. Bernard preaching.

The subsequent prevalence of Bernard’s language and his theology of Christian warfare rested on the rapid expansion of the Cistercian Order across western Christendom during and after his lifetime. Despite the Order’s original emphasis on isolation and the simplicity of the monastic vocation, it became a wealthy corporate power in church affairs, its members becoming bishops and many of its abbots acting as willing public promoters of ecclesiastical causes. The Order’s centralised federal structure, with regular general assemblies at Cîteaux, provided a convenient and dynamic network for the transmission of ideas, information and promotional material. Its close association with crusading was reflected in prayers for crucesignati within its liturgies. Cistercians played a central role in every major eastern crusade from the 1140s to the early thirteenth century. Apart from the Second Crusade, in preparation and leadership especially a Cistercian enterprise, preaching the Third Crusade was spearheaded by Cistercians such as Cardinal Henry de Marcy of Albano and Archbishop Baldwin of Canterbury, who used local Cistercian abbots in his recruiting tour of Wales in 1188. The Order hosted promoters and leaders of the Fourth Crusade at Cîteaux in 1198 and 1201, provided preachers and a number of abbots joined the expedition (e.g. Abbot Gunther of Pairis, the abbots of Loos in Flanders, Les Vaux de Cernay and Luciedo). The militant Bernardine legacy found similarly vigorous expression in the assault on heretics in Languedoc, Henry of Marcy leading a military expedition there in 1181 and Arnaud Aimery, abbot of Cîteaux, with other members of the Order, playing a prominent active part in the opening stages of the Albigensian crusades. The alignment of institutional ambition and Christian imperialism found further outlet in the occupation of new Christian territories in the southern Baltic. After 1200, in Livonia, Cistercian entrepreneurs, such as Theodore of Treiden and Bernard of Lippe, himself a veteran former soldier, followed colonising German merchants and warriors under the banner of the cross. Unlike more traditional lavish Benedictine monasteries, Cistercian houses were cheap to found and relatively simple to operate, ideal as centres of missionary work and the expression of crusading ideology. They also, more widely, preserved collective corporate memory of Bernard and of their other crusade champions. The dominant role of the Order in crusading only diminished from the early thirteenth century when preaching and organisation increasingly fell to Paris-trained secular clerics and academics and then, from the 1220s, decisively to the mendicant Orders. However, the Bernardine vision remained an indelible element in crusade preaching and ideology.

Rulers involved in regional frontier conflicts with non-Christians quickly associated themselves with the greater enterprise. Alfonso VII of Castile rebranded his campaign against Almeria as a holy war, earning remission of sins before extracting a papal bull from Eugenius confirming its status in April 1147. A further papal grant of indulgences, harking back to Urban II’s offer in1095, supported an ultimately successful Catalan siege of Tortosa in 1148. Both these campaigns involved the Genoese. In Germany, a deal brokered by Bernard of Clairvaux allowed the dissident Duke Henry the Lion of Saxony and Saxon nobles to assume crusader status for the 1147 summer campaign against the pagan Abotrites and Wends across the Elbe along the southern Baltic shore (see Chapter 8). While the agreement reflected the need for political stability in Germany and suggested the usefulness of the crusade in notionally binding hostile factions together in a common cause, Bernard trenchantly urged the need for the pagans to ‘be converted or wiped out’.36 Once again the pope obliged with retrospective approval. Such dressing scarcely concealed the material motives of the 1147 Baltic campaigns, which in the event spent as much time harassing Christian cities as pagan recalcitrants. Spanish and German frontier wars had increasingly been promoted in terms resonant with the ideology of the Jerusalem holy wars, in Spain explicitly so for the previous thirty years. In 1146–8 the extensions of crusade institutions to Iberia and the Baltic were clearly not coincidental; but neither were they planned as part of some grand strategy. The process remained reactive not premeditated.

Eugenius had set no date for muster or embarkation. Despite an apparent flirtation with a Sicilian offer to carry the French army by sea, Louis VII decided to follow Conrad III along the land route of Godfrey of Bouillon to Constantinople. Others reached the Byzantine capital via Italy and the Adriatic crossing. Alfonso-Jordan, count of Toulouse, son of the First Crusade leader Raymond IV, born outside Tripoli in 1104, sailed directly from Provence. Sea transport of armies with horses and materiel, pioneered by the Venetians in 1122–4, now offered a viable alternative. A fleet gathered from around the North Sea that mustered at Dartmouth in Devon in May 1147 may have comprised 150 to 200 ships capable of carrying up to 10,000 people. This international force, which bound itself into a sworn commune for purposes of command, discipline and sharing booty, came from the rural areas of eastern England and the Low Countries but also the commercial ports of the region: London, Dover, Southampton, Hastings, Bristol, Ipswich, Cologne, Boulogne. Sailing down the Atlantic coast, in June the armada was hired by Afonso of Portugal (1128–85) to help besiege Lisbon, then in Muslim hands (July–October 1147), the first of a number of opportunist attacks on ports in al-Andalus by passing crusaders over the next seventy years. Once the city was captured, many crusaders chose to stay. Others, mainly from Flanders and Germany, after winter refits to the ships, sailed into the Mediterranean, probably reaching the Holy Land the following spring where it is likely many were taken into service by Conrad III.

Although such disparate forces from so huge a geographical region cannot have been minutely coordinated, contingents assembled through forward planning. The North Sea fleet cannot have gathered at Dartmouth and then immediately agreed to form a restrictive commune by chance. Commerce, lordship and the Church provided regular conduits of communication to transmit crusade plans. Most forces departed between April and June 1147 and, despite contrasting fortunes, reached Outremer a year later, suggesting at least a general understanding of the timing of the mission, as well as of the determining factors of seasons, harvests and, at sea, winds, currents and, for those from northern Europe, the need for winter quarters. The precedent was known: it had taken the bulk of the first Jerusalem campaign between a year and a year and a quarter to reach Syria. The Second Crusade was slightly faster.

Not all lessons of the First Crusade were well learnt. Louis VII, despite raising money through special taxes, rapidly ran out of cash, having to seek substantial loans from the Military Orders. Militarily, the Germans suffered the same fate as the crusaders of 1101. Assembled perhaps in too great haste between the winter and spring of 1146–7, after reaching Constantinople in September 1147, the German army, possibly concerned about food supplies, refused to wait for the French army close behind, only to be severely mauled by the Turks near Dorylaeum. The army disintegrated as it retreated to Nicaea, where the battered survivors encountered the French forces. Unlike the Franks in Outremer, the Germans had not mastered the technique of a fighting march to counter the harrying tactics of the Turks. Conrad, who had been wounded in the withdrawal from Dorylaeum, retired to Constantinople for the winter before sailing to Palestine the following spring. The French fared slightly better in Asia Minor, battering their way to Adalia on the southern coast by early 1148 despite a bruising encounter with the Turks at Mount Cadmus (Honaz Daghi, January 1148). However, short of money and ships, in another echo of 1101, Louis sailed to Syria with his knights and cavalry, abandoning the bulk of the infantry to fight overland to Antioch: few made it. The Germans and the French had been undone by optimistic strategies, bad tactics, poor intelligence, indiscipline, failed logistics, canny opposition and bad weather. The Greeks, pilloried in the west as treacherous scapegoats, had not requested the crusade and were powerless to provide adequate surplus supplies even in Byzantine territory. By contrast, the Turks proved far more effective opponents than fifty years earlier.

Despite these setbacks and the Lisbon diversion, the crusaders who reached Outremer in the spring of 1148 constituted a very substantial fighting force, many thousands strong, although the French army now mainly comprised knights. On arrival in Palestine, Conrad III, flush with Greek money, hired a new army from freshly arrived crusaders. With retaking Edessa ruled out as the city’s defences had been levelled in 1146 after a failed Frankish attempt to recapture it, a campaign in northern Syria, against Shayzar or Aleppo, was also rejected, ostensibly because of a diplomatic rift between Louis VII and Prince Raymond of Antioch (1136–49) attributed by gossip to an affair between Raymond and Louis’s wife, Eleanor of Aquitaine, Raymond’s niece. More certainly, assistance to Antioch invited complications with Byzantium whose overlordship Raymond had acknowledged in 1145. In any case, most crusaders had gathered in Palestine. Conrad III emerged as the dominant western voice. The crusaders and the Jerusalemite leaders, after debating whether to attack Damascus, as in 1129, or Ascalon, decided on Damascus, with Ascalon a second option.

COMMUNES ON CRUSADE

Crusade armies were held together through a combination of lordship, kinship, clientage, affinity, peer pressure, shared locality and language, enthusiasm, compulsion, necessity and pay. Frequently, these pressures and conditions encouraged the creation of agreed mutual associations, from ad hoc agreements to pool financial and material resources to formal communes and fraternities, bound by oaths, in which disparate or connected groups and individuals combined together outside or complementary to the other cohesive social forces on campaign. Some associations were agreed in advance; some freely entered into during operations; some enforced by leaders during periods of crisis or to impose discipline. Such mutual alliances were necessary in crusade armies that were gathered from multiple localities, different lordships and diverse rural and urban communities, and in which allegiances could shift through the death or impoverishment of leaders. The presence or absence of monarchs on crusade made little difference. Beneath the outward display of hierarchy, most large-scale crusades depended on communal cooperation and consent without which they could not have functioned.

The pattern of communal arrangements fell into four broad categories. First, exigencies of campaigning required leaders to cooperate in providing supplies or the military needs of troops across the army through common funds such as those established at the sieges of Nicaea, Antioch and Jerusalem during the First Crusade; at the siege of Acre in 1189 or at Damietta in 1219. Sometimes these arrangements, as during the siege of Antioch in 1097–8, were secured by oaths, the leaders entering into temporary formal confraternities. One of the more remarkable of these sworn fraternities was established by Louis VII of France with ‘common consent’ after his army’s mauling by the Turks at Mount Cadmus early in 1148 when he put his troops under the discipline and command of the Templars.37 The second general form of communal arrangements was similar in providing for discipline within armies at the instigation of commanders but secured by oaths. Beyond simply reinforcing martial order, such provisions were necessary as in any one large army crusaders came not just from different lordships but from regions with distinct legal systems and expectations. Such communal ordinances first emerged at the siege of Antioch in 1098. They were characterised by an agreed set of detailed rules for behaviour and dispute resolution backed by judicial processes armed with draconian penalties: Louis VII’s at Metz in 1147 (although these proved abortive); successive ordinances regulating the polyglot Angevin forces in 1188–90; or the stern regulations agreed by Frederick Barbarossa, his commanders and ‘sworn in every tent’ as he set out east in 1189. These ordinances could cover everything from theft and violent crime to sexual conduct, gambling, cheating, fraud, hoarding of supplies, food prices, disposal of property, division of booty, suitable dress and the treatment of women. Not all were imposed by kings.38

59. Collective decision-making on crusade, Jerusalem 1099.

In 1147 and 1217 similar regulations were agreed by fleets from the North Sea that organised themselves into the third category of public association, the communes and confraternities established by crusaders’ mutual agreement at the very start of a campaign. The most famous of these was the commune established in May 1147 at Dartmouth, a port on the extreme south-west coast of England, by a coalition crusade fleet drawn from across the North Sea region including west Germany, northern France and southern and eastern England. Besides the agreed regulations of behaviour and punishment, all significant decisions were reached by occasionally rancorous debate in open assembly.39 This model bore similarities to corporate civic institutions appearing in increasing numbers in towns and cities across western Europe. For urban crusaders pooling resources in such a communal arrangement made logistical and business sense. A shipload of Londoner crusaders in 1190 adopted Thomas Becket (a Londoner himself) as their commune’s patron. Sea travel encouraged such sworn associations as companies frequently possessed no previous formal social ties. In 1250 one such crusade company engaged a collective class action against their cheating shippers. However, such associations were more normal than may appear: English crusaders in 1190 were generically described as coniurati, joined together by oaths.

A final method of communal organisation can be found in crusade confraternities that existed on a more permanent basis to organise donations, recruitment, funding and material support for members on crusade. While some, like those of Florence and Pistoia during the Third Crusade, Châteaudun in northern France established in 1247 or the Parisian confrarie of the Holy Sepulchre of 1320, were based on specific urban centres, others, such as the North Italian confraternity of the Holy Spirit, operated with an extended geographical reach across a number of cities.40 Founded during the Fifth Crusade, its statutes received papal confirmation in 1255 and members played a significant part in the defence of Acre in 1291. However, the communal aspect of crusade was not class distinctive. Nobles played prominent parts in the North Sea fleet communes of 1147 and 1217 and the Paris confrarie of 1320. Kings swore with their followers to communal ordinances. Setting out on the Second Crusade in 1147, Milo, lord of Evry-le-Châtel in Champagne, swore oaths of mutual loyalty with his knights (‘se federaverunt juramentis’).41 The idea that the political and ideological dominance of lordship and hierarchy precluded other forms of social engagement and association is misleading. Outside lordship or kindred, communal bonds, of friendship, commerce, occupation or belief, were ubiquitous. For crusaders, technically equal as crucesignati, such associations could be both convenient and essential.

In 1148, Damascus was no longer a Frankish ally as it had been for most of the time since 1129. Nor had it yet been absorbed into Nur al-Din’s growing empire. While the presence of so many troops encouraged Frankish hopes of success, the campaign turned into a dismal failure. A rapid march to Damascus in July 1148 was followed in days by an equally precipitate withdrawal. Although the Latin and Arabic sources do not agree, poor and indecisive tactics, the absence of a plan for a proper investment of the city, tensions within the leadership over who should rule the conquered city, perhaps sterner resistance than anticipated that dashed hopes of a quick surrender or early successful assault on the walls, all undermined the attackers’ resolve, as did rumours of an approaching Zengid relief army. No sustained operation, with catapults, sapping, battering rams and siege towers, was even attempted. As in 1129, the contrasting odds for successful sieges of inland cities and coastal ports were made clear. The retreat to Galilee was chaotic, with heavy casualties. Despite continued German support for an attack on Ascalon, divisions within Frankish and crusader ranks, exacerbated by the simmering rivalry between Queen Melisende and Baldwin III, prevented further action. Conrad left for home in September; Louis the following spring. In 1154, Damascus submitted to Nur al-Din.

The Waning of the Crusade, 1149–87?

The failure at Damascus represented a major humiliation, spawning an industry of blame, finger pointing and soul searching. Although papal bulls continued to call for new eastern expeditions, usually in response to appeals from Outremer, enthusiasm for using crusade formulae elsewhere became patchy. The tradition of associating campaigns against al-Andalus with the Jerusalem war continued, promoted chiefly by papal legates and church councils, holy war becoming embedded within the foundation of Iberian Military Orders. In the Baltic, while the language of religious war was bandied about, between 1147 and the 1190s only a bull of 1171 explicitly offered vows, cross and indulgence to war in the region. For Outremer, the Second Crusade signalled a wasted opportunity to construct a new frontier and stall the advancing unification of Syria. In the west, at least in the eyes of William of Tyre who saw the consequences first hand at both ends of the Mediterranean, enthusiasm to assist Outremer declined as the Damascus debacle was attributed to the allegedly duplicitous behaviour of the Outremer Frankish nobility.42 Despite papal attempts to excite new expeditions (at least seven between 1157 and 1184) and repeated embassies from Outremer calling for aid, western rulers tended to maintain only lip service to the cause.43 From the 1150s to 1180s, veterans of the Second Crusade, such as Louis VII and Frederick I Barbarossa (1152–90), Conrad III’s nephew and successor, but also Henry II of England, (1154–89) talked of taking the cross but failed to do so. Instead, in 1166 and 1185 the French and English kings agreed to levies on income as well as property to help Outremer, the first European income taxes. By the 1180s, Henry II, a close relative of the Jerusalem kings, had salted away a considerable treasure in Jerusalem supposedly to await his arrival. When in 1177–8, Count Philip of Flanders led a substantial army in the Holy Land chiefly drawn from northern France, he fell out with the Jerusalem government and his campaign in northern Syria proved ineffectual, fuelling western disenchantment. The increasingly dysfunctional internal politics of the kingdom of Jerusalem after the accession of the adolescent leper Baldwin IV (1174) presented particular challenges to visiting crusaders.44 Either, like Philip of Flanders, they came with sufficient forces to dictate their own policy that might not fit local plans; or they brought with them contingents too small to alter the military balance in Outremer.

The Holy Land still offered career advancement for nobles and clerics with limited prospects in the west. The pious and those obligated by penance, punishment or oaths still sought Jerusalem. William Marshal, the future Regent of England (1216–19), went east in the mid-1180s to fulfil the crusade vow of his dead master, Henry, the eldest son of Henry II (d. 1183). The north Italian nobleman William of Montferrat was attracted by the promise of a royal marriage to Baldwin IV’s sister Sybil and heir in 1176. The pilgrimage trade still flourished, adding to the growth in the commercial profits of Italian cities whose fleets still underpinned Outremer’s survival. However, short of a defining crisis in Outremer, European politics precluded the necessary diplomatic consensus for a new grand expedition. The papacy was involved in a series of disputes with potential crusade leaders, most draining and damaging being those with Frederick Barbarossa from 1159 to the early 1180s over power in Italy, but also with Henry II of England over his struggle with Archbishop Thomas Becket of Canterbury over church jurisdiction in the 1160s. England only emerged from a long civil war in the mid-1150s. Louis VII and his successor Philip II (1180–1223) conducted a near-permanent feud with Henry II who, as duke of Normandy and Aquitaine and count of Anjou also ruled most of western France. Successive ineffectual treaties between the contestants included mutual agreements to depart on crusade, convenient diplomatic cover rather than binding commitment. In Italy, Frederick Barbarossa’s attempts to assert imperial rule met decades of local opposition that drew in the rulers of Sicily as well as the papacy. The maritime cities remained willing partners but not initiators of an eastern crusade. The failure to take advantage of a papal and Outremer-backed Byzantine alliance in the 1170s represented an opportunity that, after Manuel I’s defeat by the Turks at Myriokephalon in 1176 and death in 1180, followed by the overthrow of the pro-western Greek regime in 1182, did not recur.

Revulsion at the failed Second Crusade did not abolish interest in the Holy Land. Surviving vernacular literature, much of it critical of the antics of crusaders, kept both the images and stories of holy war in the east alive, reflecting continued interest and understanding. Outremer remained a focus of absentee religious devotion and occasional pious chivalric self-fulfilment. General understanding of holy war remained: reward for fighting for the faith. An assumption of Outremer’s permanence naturally grew with the passage of time and the mundane reality of contact through pilgrimage, immigration and trade, consolidating a normalisation of attitudes. Outremer became just another in the community of states in Christendom, elevated by its status not its predicament, its demands assessed on politics not eschatological transcendence. The traditions and memories of past crusades did not disappear. Physical mementos did not lose their attraction. Outside academic refinement, ecclesiastical rules or political calculation, popular understanding, for example of the act of taking the cross, persisted, providing a receptive audience to the dramatic call to arms in 1187 when the sudden collapse of Outremer turned general sentiment into shocked action.

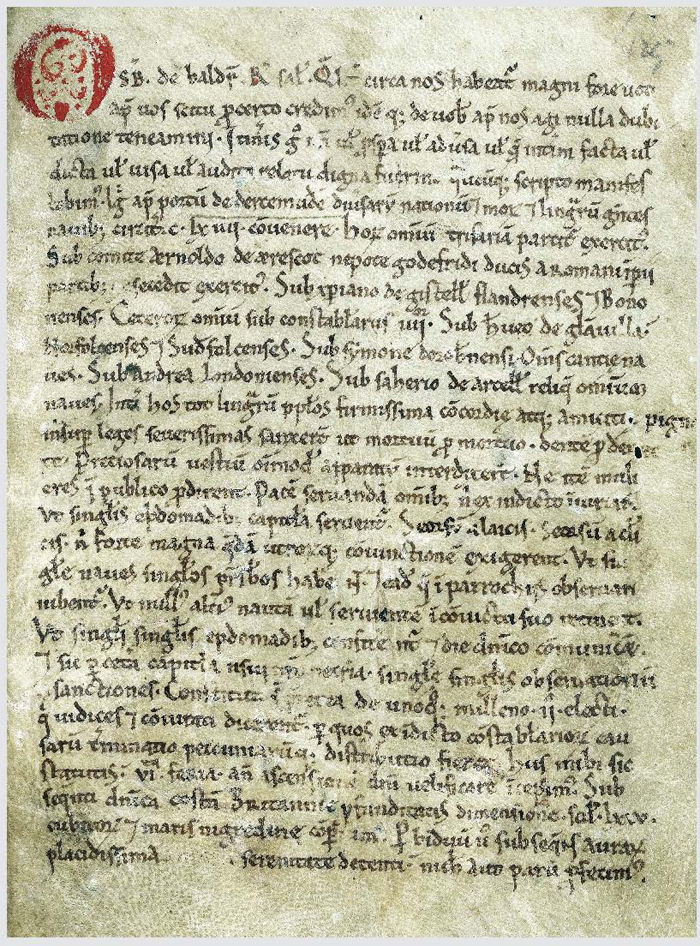

SECOND CRUSADE MANUSCRIPTS

Chronicle accounts of crusades can provide a barometer of contemporary responses. The explosion of texts concerning the First Crusade told its own story not just of the initial reception of those startling events but, in subsequent copying and circulation, of how the memorialised narratives continued to be used in promoting later expeditions and encouraging crusading commitment more generally.45 The reverse is also evident. A dismal crusade left fewer immediate literary traces and even less succeeding interest. Contemporary written accounts of the Second Crusade (1145–8) exemplify this, while simultaneously demonstrating the often precarious and random bases of modern historical information. The most detailed accounts of any parts of the crusade cover the siege of Lisbon in 1147 and Louis VII’s campaign to Antioch in 1147–8. They only survive in a single manuscript each without which our knowledge of events would be both very diminished and very different.

The De expugnatione Lyxbonensi (The Siege of Lisbon) survives in one messy copy written on poor parchment probably dating from the 1160s or 1170s, now bound into a volume of other texts collected in the sixteenth century by Archbishop Matthew Parker of Canterbury and in the library of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge.46 Both its original authorship and subsequent provenance are obscure, although the dedicatee (Osbert, clerk of Bawdsey in Suffolk) and probably the author (‘R’ in the manuscript) came from the circle of a prominent East Anglian family, the Glanvills, one of whom, Hervey of Glanvill, led a contingent of crusaders at Lisbon.47 The text is in a short book form, a libellus, familiar from texts that lay behind First Crusade chroniclers. It describes the course of a North Sea crusade fleet between May and October 1147, from assembly at Dartmouth to the successful completion of the Lisbon siege. Composed in a common narrative epistolary format, despite its apparent eyewitness immediacy, the text’s content is artfully composed, shot through with tropes of canon law, classical and scriptural allusion, and contemporary arguments for holy war. When recording one of Hervey of Glanvill’s speeches to the troops, in a marginal note the text warns the reader that these were not his actual words.48 The general accuracy of the narrative finds some corroboration from a much shorter German account, also in letter form.49 Without the survival of the sole manuscript, we would know little about the Dartmouth commune or details of how the crusaders were hired to besiege Lisbon, and less about the organisation of such fleets and armies or the cultural penetration of central themes of crusade ideology and advocacy in the mid-twelfth century.

60. De expugnatione Lyxbonensi.

The sole manuscript of Odo of Deuil’s account of the crusade of Louis VII of France from Christmas 1145 to his arrival in Antioch in March 1148, De profectione Ludovici VII in orientem (The Journey of Louis VII to the East), is also couched in the context of a letter, in this case to Odo’s monastic superior Abbot Suger of St Denis. Odo claimed to be providing material for the abbot’s putative biography of King Louis.50 Twelfth-century St Denis had established itself as a centre for royalist historiography. Odo (d. 1162), who served as one of King Louis’ household chaplains on crusade, wrote within this tradition, placing the king at the dramatic and didactic heart of the narrative as an exemplar of Christian kingship and personal virtue whose piety prevailed over personal mistakes and extreme challenges. The work’s lack of circulation and its critical appraisals of the crusaders’ actions have led some modern critics to wonder, perhaps implausibly, whether the text is a contemporary literary fiction critiquing crusading ideology and practice. To a standard scriptural and classical education, Odo, who succeeded Suger as abbot of St Denis in 1151, added close awareness of chronicles of the First Crusade, a copy of one of which he took with him on the journey east. Yet Odo’s work led nowhere. Suger died before using it; other writers either ignored or did not encounter it. It survives in a single later (c. 1200) high-class manuscript, probably copied at the Cistercian abbey of Clairvaux in whose library it was until the French Revolution.51

61. Seal of King Louis VII of France.

The survival of these two unique texts allows detailed insight into singular perspectives on just two limited parts of the campaigns of the Second Crusade. While numerous other sources exist, none is as full or seemingly immediate. If these two solitary manuscripts had not survived, our knowledge of the crusade would have been at once severely curtailed and more balanced. Thus they can stand for the study of much of the crusades: inverted triangles of imposing interpretive superstructures perched on narrow evidential support.