CRUSADES AGAINST CHRISTIANS

Wars between Christians had been presented as earning spiritual merit long before Urban II’s Jerusalem campaign of 1095. Once Christianity became identified with political authority, dissent could be treated as a challenge to the religious as well as secular establishment. To defend the state was to defend its Church and vice versa. Early medieval Christian armies sought divine approval before fighting other Christians, carrying religious images and relics into battle and enjoying church blessings of troops, banners and weapons. Individual warriors welcomed the comforts of religion before the deadly hazard of battle through prayer, confession or the sacrament. While religious war against non-Christians remained easier to justify, claiming divine sanction in battles against co-religionists became commonplace. By the tenth century, popular liturgies were including prayers likening victory in temporal battle to Christ’s victory on the cross.1 From the eighth century, the image of active Christian warriors received increasing clerical respect, as protectors of the faith and even models of conduct. Martial saints became more prominent in church dedications and iconography. Popes explicitly promoted military champions of the Church. In 1053, Leo IX granted remission of penance and absolution of sins to his followers fighting the Normans of southern Italy. Gregory VII further moralised war in consecrating the violence of his supporters in Milan in the 1070s as a war of God (bellum Dei), offering ‘absolution of all your sins and blessing and grace in this world and the next’ to adherents fighting against Henry IV, and recruiting what he and his partisans called milites Sancti Petri.2 Secular wars against supposed religious disobedience or schism attracted papal blessing as they had enjoyed local episcopal approval for generations. In 1066, William of Normandy fought Harold II of England, stigmatised as a perjured protector of a schismatic archbishop (Stigand of Canterbury), under a papal banner. Gregory’s framing of political conflict in spiritual terms received academic gloss from sympathetic scholars who approved of the penitential service of an ‘ordo pugnatorum’ fighting just wars to defend the Church and the weak against tyrants, excommunicates, schismatics and heretics.

While these precedents formed a significant context for Urban II’s Jerusalem war, the new institutions of the crusade – preaching, vow, cross, privileges – did not automatically transfer to these older forms of ecclesiastically justified inter-Christian conflict. Conservatism prevailed in practice and legal theory. Policing operations by Louis VI of France (1108–37) were supported by parish priests bearing banners to join royal armies along with their parishioners in operations described by sympathetic memorialists in terms of war directly approved by God and the clergy (‘the pious slaughtered the impious’), including, one observer suggested, absolution of sins and salvation for those who died.3 One account of the Anglo-Scottish battle of the Standard in 1138 suggested that the English who died would receive remission of penalties of sin. Offers of remission for those killed in battle, for example against mercenary war-bands in Languedoc in 1139, appeared more frequently. This may reflect the generally greater precision in describing the Church’s penitential and legal systems, as witnessed by Gratian’s canon law compendium, the Decretum (1139), in which wars against Christians occupy much space (the crusade against the infidel none).

Elsewhere, direct links to the crusade were made. Paschal II, in the afterglow of the First Crusade, offered plenary remission or absolution for conflicts against his political opponents and, under the masquerade of a new crusade to Palestine, to Bohemund’s campaign against Byzantium in 1107–8. The influence of the First Crusade provisions was apparent in spiritual rewards offered to papalists in the war against the anti-pope Anacletus in the 1130s, an association explicit in the indulgence proposed at the Council of Pisa in 1135. However, the First Lateran Council of 1123 reserved the Jerusalem war institutions to conflicts in the Holy Land and Spain, a restriction tangentially extended to Wendish pagans by Eugenius III in 1147. During campaigns crucesignati did fight Christians: Greeks during the First, Second and Third Crusades and the Venetian crusade in 1122–5; and Sicilians in 1190; but none was the stated object of crusade vows. In 1197 an exasperated Celestine III exceptionally authorised Holy Land privileges to those who sought to bring Alfonso IX of León to heal after he had campaigned with Moors against fellow Christians. However, the material advantages of crusading as they had matured by the 1190s – legal protection, debt relief, access to special taxation and church funds – coupled with the militant evangelising and political agenda of the papacy, made the association of crusading with wars against Christians likely. In 1199, Innocent III granted Holy Land plenary indulgences to those who campaigned against the German Markward of Anweiler (d. 1202), ‘another Saladin’, who was challenging papally supported regents in the kingdom of Sicily. Innocent argued that Markward threatened the Papal States and the new Jerusalem crusade.4 As other crusade features such as vow, cross and temporal privileges were absent, this hardly constituted radical departure, more logical opportunism.

Crusades against Christians

Innocent’s logic went further. In 1208 the full Holy Land paraphernalia of preaching, cross, indulgence and temporal privileges were deployed to deal with the heretics of Languedoc, an initiative confirmed and reinforced by the Fourth Lateran Council in 1215.5 As the practice developed, three different categories of Christian opponent attracted crusades: heretics, classed as religious deviants, who consciously refused to accept the orthodox teachings and authority of the Church, notably but far from exclusively the Cathars in Languedoc; the religiously ignorant, such as sections of the German peasantry or Bosnian faithful in the 1220s and 1230s, whose failings were deemed to require forcible discipline; and those whose political actions endangered the integrity of the Roman Church, its territory or its client states, and who therefore could be accused of fomenting schism, which readily equated with heresy. Chief antagonists in this last category were the Hohenstaufen rulers of Germany and Sicily until 1266 and, thereafter, anti-papal powers in Italy and the western Mediterranean. As obedience to social and political hierarchies mirrored God’s ordered world, disruption or disturbance invited scriptural condemnation (e.g. ‘Kingdom/House divided against itself cannot stand’, Mark 3:24–5; ‘foxes in the vineyard’, Song of Solomon 2:15). Heresy, in reality rejecting existing ecclesiastical establishments, was branded as treason to God, offering falsehood instead of truth, corrupting the Church, weakening its ability to save souls or, in a crusading context, restore the Holy Land. Heresy was thus deemed to pose an existential danger to every faithful Christian. Like a cancer, it needed excision. Political opponents who attacked the pope’s lands in Italy threatened the pope’s security and, thus, given the Roman Church’s claim to embody the universal Church, constituted an assault on the whole Church. To counter possible disquiet, crusades against Christians were repeatedly equated with less controversial targets, with opponents branded as obstructions to the cause of the Holy Land, collaborators with infidels, similar to or worse than ‘Saracens’ or pagans. The Hohenstaufen excited particularly fevered papal excoriation as enemies of the Church, ‘treacherous and impious’, Frederick II a ‘limb of the devil, minister of Satan and calamitous harbinger of the Anti-Christ’, likened to the Biblical Pharaoh and Herod and the Roman Nero, his son a closet Muslim.6 Not everyone was convinced.

110. A contemporary depiction of Markward of Anweiler.

Developing academic canon law on categories of just war made war against fellow Christians easier to justify on general grounds of legitimate violence, defence, retribution, the recovery of land and rights denied or wrongfully invaded, and the restoration of peace. The clergy attached to the Fourth Crusade persuaded crusaders to fight the Greek Christians in 1204, arguing that the Greeks were regicides, or tacitly complicit in regicide and ‘above and beyond all this’ schismatics, so ‘this battle is right and just (droite et juste)’; those killed in the fighting qualified for the crusaders’ indulgence provided they had fought with the ‘right intention’ of returning Byzantium to obedience to Rome and had confessed their sins.7 As crusade preaching and propaganda became increasingly the preserve of theologians and canonists trained, like Innocent III himself, at the universities of Paris and Bologna, crusade rhetoric adopted just-war arguments. In the mid-thirteenth century the canonist and crusade preacher Henry of Segusio (Hostiensis, c. 1200–71) identified seven different types of just war, arguing for the priority of crusading within Christendom (the crux cismarina) over the overseas crusade (crux transmarina). As well as condoning papal crusades against the Hohenstaufen, this drew on the older legal criteria for just war against heretics, seen as a greater threat to Christian souls than infidel possession of the Holy Land.8 Not all wars fought against Christians on behalf of Church or pope after Innocent III’s reign attracted the trappings of crusading. Nonetheless, the crusade within Christendom became the most exploited use of the war of the cross in the later thirteenth and fourteenth centuries.

Four long-term trends contributed to this. Two were financial: the extension of the uniquely generous crusade indulgence to non-combatants who, from 1213, could redeem their vows for material contributions; and the introduction of church crusade taxes (proposed in 1199; implemented in 1215). These provided obvious incentives for rulers to get their wars proclaimed crusades. The third development arose from the consolidation of a papal state in central Italy from Innocent III’s pontificate onwards that required policing and defending. Finally, the thirteenth century saw the general promotion of the crusade as a model of Christian life within a beleaguered societas Christiana threatened by sin, temporal enemies and religious dissidents. Initiative for crusades against fellow Christians came from the pope but also from regional secular and ecclesiastical authorities pursuing local interests. This denied many internal crusades the universal appeal of wars with infidels and attracted more critical scrutiny than their Holy Land exemplars.

The Albigensian Crusades, 1209–29

The suppression of heresy, broadly defined as false beliefs and disobedience to the authority of the Church, provided an established justification for the use of physical force. Gratian of Bologna’s mid-twelfth-century Decretum conveniently collated patristic and later texts defining heresy and the measures that legitimately could be employed against them. Events pushed the issue into prominence as religious diversity and dissent proliferated during the eleventh and twelfth centuries across western Christendom. The reasons for this are contested and complex: the quickening of the transmission of ideas following the expansion of regional and international commerce; a simultaneous growth of literacy, the technology of writing and access to learning; the encouragement of criticism of ecclesiastical structures and traditions by church reformers, including some eleventh-century popes; the erosion of customary hierarchical alliances between lay and church authorities in the wake of the Investiture dispute; the emergence of greater urban political autonomy; the popularity of ideals of puritanical austerity in reaction to the increased materialism of a wealthier society; the emergence of a self-conscious clerical elite jealous of its authority and privileges; the encounter with different Christian and infidel belief systems. The move towards greater definition in theology and canon law inevitably placed uniformity at a premium, threatening eccentricity or deviation with exclusion and condemnation and making anomalies in law, doctrine or ritual more obvious and more dangerous. Heresy was defined by shifting orthodoxy. Nevertheless, in the sense of adherents to different belief systems or lived patterns of expression, heretics existed, more visible to the vigilant gaze of fresh-minted guardians of religious truth.

Heresies fell into different categories. Refined academic disputes; evanescent charismatic personality cults exploiting popular anxiety over death, divine judgement and the end of the world; and organised social revolts that embraced aggressive anti-clericalism. Most proved fleeting, arcane or ephemeral. More challenging were groups of believers with resilient corporate identity possessing distinctive shared literature, doctrine and ritual. Notable among these were the followers of Peter Valdes (c. 1140–c. 1205), the Poor Men of Lyons or Waldensians, whose puritanical scriptural fundamentalism contradicted the official Church’s development of an elaborate sacramental penitential system. After papal investigation condemned them as heretics from the 1170s and 1180s, Waldensian communities established themselves, chiefly in the French and Italian Alps, suffering a crusade as late as in 1488, before being subsumed into the sixteenth-century Protestant Reformation.

More threatening than cells of radical Christian dissenters appeared to be the adherents to a wholly alternative Christian theology to trinitarian Christianity, now known as Cathars (from the Greek katharos, ‘clean’ or ‘pure’, a term used by some of their opponents). Cathars regarded creation as controlled by two principles, Good and Evil, expressed through the different spheres of the spiritual and material. Some thought that Evil/the material came from a rebellion against the Good God, a view not that far removed from orthodox Christian teaching. Others, more radically, believed the two forces were co-eternal, the material world being the creation of Lucifer, the Evil force, not the Good God. This dualist doctrine contradicted the most fundamental tenets of traditional Christianity as it denied the Good God could in any material sense become part of the Evil temporal world and so rejected the Incarnation. The more absolutist position became prevalent across Cathar communities from the 1160s. As with orthodox Catholic believers, precise details of doctrinal theory were filtered by Cathar faithful, the credentes, into simpler articles of belief: the reality of sin; the evil inherent in creation and the material world; the primacy of asceticism; the rejection of the carnal, including marriage, sex and procreation. The central ritual to which the faithful aspired, often on their deathbeds, was the consolamentum (derived from the Latin for ‘strengthening’ or ‘comforting’), a sacramental rite in which the believer received the Holy Spirit and absolution of sin, becoming a perfectus (or perfecta: unlike the Catholic Church the Cathars lacked formal institutional misogyny). Perfecti, sometimes known as Boni Homines, or Good Men, acted as preachers, delivering the consolamentum, and leading exemplary lives avoiding meat and sexual intercourse.

Cathar communities apparently produced written theological and doctrinal texts, in Latin and the vernacular. The circulation of these texts was mirrored by international contacts between dualist groups in northern and southern France, west Germany, northern Italy, the Balkans (another name for Cathars was ‘Bulgarian heretics’) and Constantinople. Some of these communities appear, by the second half of the twelfth century, to have been organised into recognised bishoprics that shadowed Catholic provinces. Cathars were Christian, just not Catholic or Trinitarian, rejecting the Catholic sacramental system and the humanity of Christ. Large parts of the New Testament and a few passages from the Old Testament were incorporated and reinterpreted by Cathar preachers and theologians, their discussions, as recorded, littered with scriptural references. Theirs was a wholly different version of the Christian message, which nonetheless confronted many of the same issues as Catholic teaching: the problem of sin and evil; anxiety over materialism; the dangers of moral and venal corruption of the Church and churchmen; the desire to return to some pristine austerity. In many ways, the similarities and points of contact with mainstream Catholicism made Cathars in the eyes of church authorities appear more insidious, especially where organised in regional social networks supported by believers with property, money and status.9

The origins of western Christian dualism – the belief in two competing cosmic forces – probably lay in evangelism from the Bogomil dualist Church, established in the Balkans in the tenth century. As part of the increasing flow of commerce and people between Byzantium and western Europe in the eleventh and early twelfth centuries, Bogomil dualist doctrines were possibly mediated by western, Latin converts in Constantinople. Probably from at least the 1140s, dualist communities existed in the Rhineland, Champagne, western Languedoc and Lombardy. By the 1170s, dualist bishops had been established in Lombardy, northern France and across Languedoc – Agen, Albi, Carcassonne and Toulouse – and were likely in contact with a bishop from Constantinople. The number of Cathar believers is hard to assess through lack of statistical evidence and because the nature of the faith blurred confessional boundaries. Dualism existed socially in tandem with Catholicism, one strand in a diverse popular religious culture, the plurality of which added to the disquiet of church authorities. A Catholic knight justified his refusal to pursue heretics from his lands: ‘we cannot; we were brought up with them, there are many of our relatives amongst them, and we can see that their way of life is a virtuous one’.10 Where lay and ecclesiastical authorities worked in harmony, as in parts of the Rhineland, northern France, or England, heretics were vigorously policed and contained by orchestrated repression and swift joint legal action. Where no such alliance existed and where the Church’s increasingly prescriptive intrusions into social behaviour were matched by popular dislike of clerical wealth and hierarchical solipsism, alternative doctrines could flourish.

Languedoc between the Garonne and Rhône rivers proved especially fertile ground, a region of distinctive cultures, commerce, political rivalries, loose centralised lordship, and ineffective pastoral leadership, with intractable geography, distant from the centres of reformist Catholicism. The Cathar heresy attracted members of social elites, not just the excluded or marginal. The papacy began to take notice, from the 1170s planning counter-measures that within a generation led to the unleashing of a crusade to eradicate heresy in the region. Heresy was not new to Languedoc in the 1170s. Bernard of Clairvaux had preached against heretics there in 1145. However, the rise of organised Catharism prompted Count Raymond V of Toulouse (count 1148–94) to seek outside assistance. A mission to Toulouse led by a papal legate, Peter of Pavia, and Henry of Marcy, abbot of Cîteaux, in 1178 excommunicated a number of prominent local heretics. They probably observed how heretics were accepted members of Languedoc society, freely engaged in trade, employment, landholding, and mundane communication with their Catholic neighbours and relatives. A more strident policy was proposed by Canon XXVII of the Third Lateran Council of 1179, which offered the threat of physical coercion as well as excommunication. Those who fought heretics in southern France were to receive papal protection of person and property, ‘as we do those who visit the Lord’s Sepulchre’, and a limited, two-year remission of penance; those who were killed would be rewarded with a full indulgence and salvation. The politicisation of the campaign against heresy was reinforced by the canon’s inclusion of similar provisions for those who enlisted against rapacious mercenary companies terrorising Christian communities ‘like pagans’.11

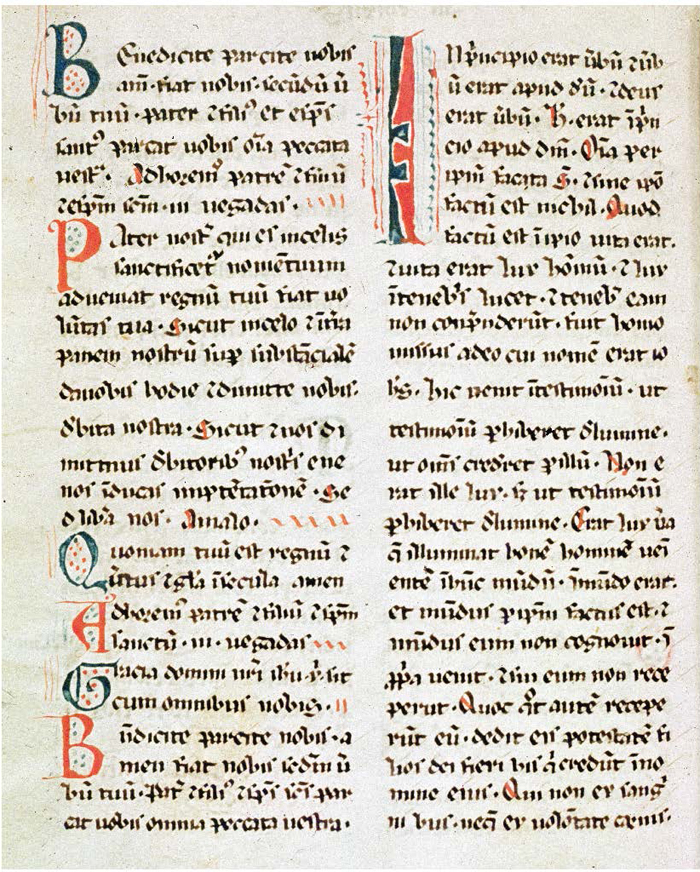

111. Fragment of a Cathar text.

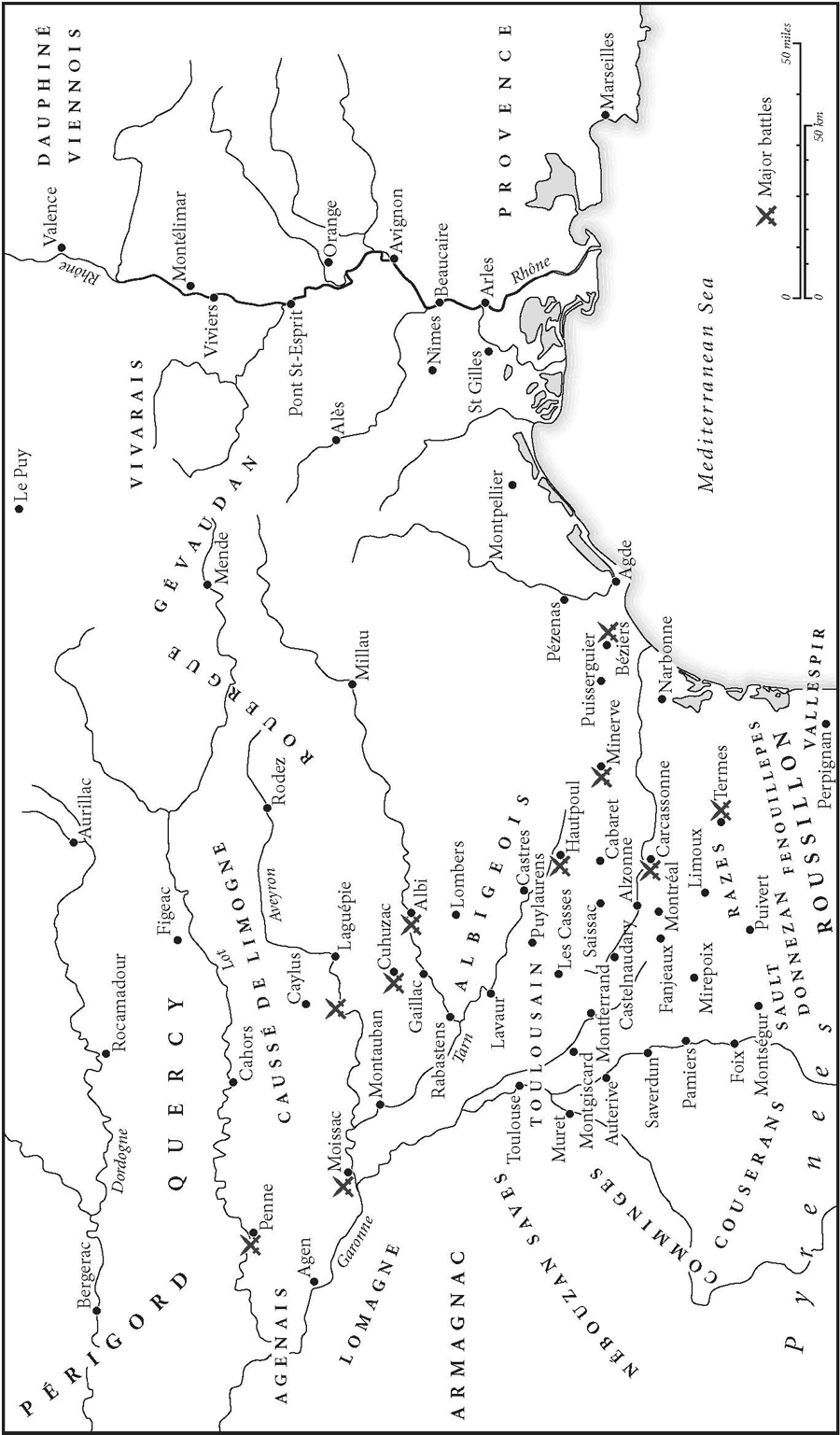

15. Languedoc and the Albigensian Crusade.

The response was modest. A small military campaign in 1181 under Henry of Marcy, now Cardinal Bishop of Albano (and future preacher of the Third Crusade), briefly besieged Lavaur, a major Cathar centre between Albi and Toulouse, securing the conversion of two prominent Cathars who were then installed in canonries in Toulouse – an ironic demonstration of the fluidity of allegiances that made eradicating heretics so problematic. In 1184, Lucius III’s bull Ad Abolendam decreed condemned heretics should be delivered to the secular powers for unspecified punishment. However, only with the failure of Innocent III’s legatine missions (1198, 1200–1, 1203–4) did a new policy of direct action emerge that bypassed the inertia of Count Raymond VI of Toulouse (1194–1222), increasingly seen by the pope as an obstacle if not an outright enemy, and a supporter of heretics. In 1204, when appointing a new legate in Languedoc, Innocent offered Holy Land crusade indulgences to those who joined the struggle against the heretics, at the same time trying to persuade Philip II of France to support the ‘material sword’ against them.12 Efforts to engage Philip failed, despite a further offer of Holy Land indulgences in 1207. The direction of Innocent’s policy was clear: ‘wounds that do not respond to the healing of poultices must be lanced with a blade’. In January 1208 the assassination of the papal legate Peter of Castelnau near St Gilles on the Rhône by an employee of Raymond VI provided Innocent with the opportunity to launch a full crusade in the cause of ‘faith and peace’, urging ‘knights of Christ’ against ‘the perverters of our souls’, worse than Saracens: ‘we must not be afraid of those who kill the body but of him who can send the body and soul to hell’.13 Command, preaching and recruitment for the crusade army were entrusted to the papal legate Arnaud Aimery, abbot of Cîteaux. Recruits were clear that they were crucesignati ‘against the heretic Albigensians’ (hereticos Albigenses), and, like those in the Jerusalem wars, their mission was penitential, their status akin to pilgrims.14

In practice, the Albigensian crusades differed from other theatres of crusading. With recruits from across much of France, the proximity of the battlefields – not more than a very few weeks’ march – encouraged short-term commitment. In 1210 the legates insisted that at least forty days of service were required before crusaders could receive the full indulgence, a term that soon became standard. Rhetoric was tailored to elevate the war against heretics and their supposed protectors to equivalence with the Holy Land crusade. From the start the Albigensian crusades involved regime change across western and southern Languedoc. This held serious implications alike for the invading crusaders and the local counts and lords threatened with dispossession, but also for other interests: the kings of Aragon, France and England (in his role as duke of Aquitaine), each of whom had claims to overlordship in the region; the compromised southern French ecclesiastical establishment; urban communities in cities such as Toulouse, eager to assert autonomy; and the papacy, whose policy never lost sight of wider international implications. The objective of extirpating heresy provided a raw, at times vicious religiosity, inciting, if chroniclers can be believed, often fanatically barbarous ferocity in treating opponents and captives. Until subsumed into French royal policy in the 1220s, the Albigensian crusades lacked consistent or adequate external funding beyond the resources of participants and the lands they invaded. Socially, the crusades exposed a cultural gulf: the crusaders’ genuine or confected horror at the existential threat of heresy collided with the daily experience of Languedoc where fellow Catholics and heretics had lived together without violent confessional conflict.

For the first campaign in 1209, Abbot Aimery recruited widely in northern France, despite Philip II remaining aloof. The leading nobles included Duke Odo III of Burgundy (1193–1218) and the counts of Nevers, St Pol and Boulogne. They were self-funded; their followers were paid. Duke Odo recruited Count Simon V of Montfort (d. 1218), the future leader of the crusade, with ‘substantial gifts’.15 This did not suggest a lack of emotional or ideological commitment: Simon proved a stern, tenacious uncompromising zealot against heretics. Given the temporary seasonal nature of most crusaders’ commitment, material incentives of conquest alone cannot explain recruitment. Rather, motives conformed to similar church-approved expeditions: peer-group enthusiasm; reputation; spiritual reward; payment; and putting military habits to recognised good use.

Although the crusaders identified their enemies as ‘Albigensians’, after Albi, a major centre for heretical support, the initial target in 1209 was Toulouse and its excommunicate count. This quickly changed when Raymond VI prudently submitted, taking the cross in June 1209 as the crusading army neared. This deflected the invasion to Béziers and Carcassonne, lands held by Viscount Raymond Roger Trencavel (also lord of Albi) who, though personally orthodox, refused to comply with the crusaders’ demands to persecute heretical subjects. The tone for the crusade was set on 22 July with the sack of Béziers and the massacre of its inhabitants, regardless, the legates with the army reported, ‘of rank, sex or age’.16 Even if the notorious story of Aimery Arnaud dismissing qualms over killing fellow Catholics (‘Kill them. The Lord knows who are his own’, II Timothy 2:19)17 is apocryphal, making an example of Béziers showed the religiously inspired invasion as determinedly political in execution. Previous failures of direct evangelism had persuaded crusade planners that eradication of heresy depended on the removal of complaisant or complicit local rulers and their substitution by energetic promoters of Catholic orthodoxy. The first step came after the surrender of Carcassonne on 14 August 1209 with the election of Simon V of Montfort as commander of the crusade and ruler of the Trencavel lands. Over the following twenty years, to the accompaniment of calculated self-justifying sanctimonious atrocities, the Albigensian crusades redrew the political map of Languedoc, redesigning its social and tenurial contours through dispossession and the redistribution of loyalties, lordships and estates. The consequent disruption, devastation and lawlessness scarred the region for decades. Yet, with cruel irony, while heresy was driven underground, it was far from obliterated.

The Albigensian crusades fell into four rough periods: the conquest of the Trencavel lands, 1209–11; the Montfortian annexation of the county of Toulouse and the Pyrenean counties to the south, 1211–16; a messy revival of concerted local resistance, 1216–25; and the final decisive campaigns of Capetian armies, 1226–9. Until 1226 regular crusading reinforcements, while militarily significant, merely added temporary makeweights to existing and shifting political balances of power; even the interventions of Philip II’s son Louis (1215, 1219) made little lasting impact. Until his defeat and death at the battle of Muret against the Montfortians (2 September 1213), Peter II of Aragon, a crusader against the Moors at Las Navas de Tolosa only the year before, presented the most serious challenge to the reordering of Languedoc. Historic Aragonese claims of overlordship were incompatible with the creation of a separate Montfortian principality, pushing Peter towards support for the dispossessed Raymond VI. However, even Muret’s apparent resolution of the fate of Languedoc proved temporary.

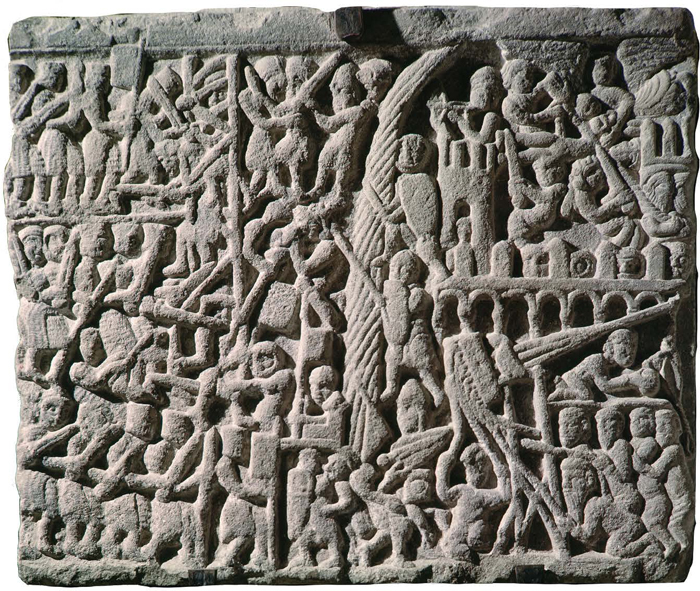

112. Stone relief showing the siege of Carcassonne, 1209.

Apart from the resistance of local baronage, concerned less with religious orthodoxy than their freedoms, traditions and property, and sharp rivalries between Montfort and the new church hierarchy, geography posed the chief obstacle to conquest. The hill country of the Pyrenees foothills and between the valleys of the Aude, Tarn and Lot, speckled with castles and fortified villages, often remote and protected by forbidding terrain, made political control from distant centres on the Garonne or Mediterranean coastal plain difficult. The landscape forced an unceasing round of arduous policing sorties long after nominal control had initially been seized from local lords. Tenacity proved Montfort’s most necessary quality.18 Closely linked to reformist academics and orthodox evangelical groups, such as the early Dominicans, Montfort on the Fourth Crusade had baulked at fighting fellow Catholics at Zara in 1202, reportedly announcing before he left the expedition that ‘I have not come here to destroy Christians’.19 His orthodox horror at heresy appears sincere; it also proved convenient in his attempt to carve out a Montfort principality.

The military campaigns revolved around sieges and piecemeal investment of castles, villages and towns. Precariously funded by church taxes, booty, and income and tributes from conquered territory, the core of Montfort’s armies was modest, although repeatedly swelled by brief attendance by recruits from the north. The conquest of Trencavel lands was complete by May 1211. Attention then turned to the lands of the re-excommunicated Raymond VI and his Pyrenean allies, the counts of Comminges and Foix. After victory at Castelnaudary in September 1211, one of the few pitched battles of the wars (Muret 1213, Baziège 1218 the others), in 1212 Montfort conquered large swathes of territory from Agen on the Garonne towards the Pyrenees, although Toulouse itself eluded him. Signalling his dominance in the creation of a new polity, in December 1212 he issued the so-called Statute of Pamiers, establishing judicial, tenurial and ecclesiastical rights in his new lordship, privileging northern French incomers, who would enjoy the ‘usages and customs observed in France around Paris’.20 However, in January 1213, Innocent III, now focused on a new crusade to the Holy Land, cancelled further crusade indulgences for Languedoc in response to slick diplomacy by Peter of Aragon, whose attempt to broker Raymond VI’s rehabilitation was rejected by the militantly hostile papal legates. Montfort was instructed to return his conquests of 1212. However, pressure from his legates forced a papal volte face. The bull Quia Maior (April 1213) launching the Fifth Crusade allowed inhabitants of Languedoc to take the cross against the Albigensians once more, and Montfort’s position was restored in May, provoking Peter II’s invasion and Montfort’s crushing victory over Aragonese and Toulousan forces at Muret.

113. Languedoc castles: Tour Cabaret and Tour Regine, near Lastours.

In 1214–15, Montfort tightened his hold over the county of Toulouse, extending his control northwards towards the Dordogne and the frontier with Angevin-held Guyenne. His title to the county of Toulouse was recognised by the Church and Philip II’s only son, Louis, who toured Languedoc in the spring of 1215, fulfilling a crusade vow taken in 1213. The Fourth Lateran Council (November 1215), while restoring the count of Foix to his lands, confirmed Montfort in possession of the county of Toulouse and the Trencavel possessions, titles with which Montfort was invested by Philip II in April 1216. By the end of that year even the city of Toulouse was in Montfort’s hands. However, the completeness of his victory provoked reaction, facilitated by the French court’s distraction over Prince Louis’ invasion of England in 1216–17. Raymond VI began to regain support and territory. In September 1217, Toulouse opened its gates to him leading to another siege at which, on 25 June 1218, Montfort was killed, struck on the head by a stone hurled by a mangonel in the city, operated, some claimed, by women. With the tables now turned, a new crusade was announced by Honorius III in August 1218, led in 1219 by Prince Louis. Some initial success was followed by failure to take Toulouse. Louis withdrew in August 1219, leaving Montfort’s less talented son, Amaury, to preside over a gradual deterioration of the Montfortian position. By 1223, a truce between Amaury and Raymond VII (1222–49) found much of Languedoc, including the Trencavel lands, regained by the families of its pre-1209 rulers. By 1225, Amaury had effectively given up, ceding his rights in the south to the new French king, Louis VIII (1223–6), the crusade apparently a military, political and, given the survival of heresy, religious failure.

This verdict was rejected by Louis VIII. The crusade posed unfinished business for a twice-sworn Languedoc crusader eager to promote his new kingship in sacral terms and anxious to further dominate the south following his conquest of Poitou from the Angevins in 1224. With the pope still implacably hostile to reconciliation, Raymond VII was excommunicated in late 1225 and a clerical crusade tithe ordered. Louis took the cross for the third time in January 1226, leading a large army south in June. A three-month siege of Avignon led to its negotiated surrender in September and the submission of Provence and most of Languedoc. Although Louis died on his return journey north (in November 1226), remaining Toulousan resistance was broken by vicious ravaging campaigns in 1227 and 1228 led by Humbert of Beaujeu, the Capetian agent in Languedoc. The Albigensian crusades ended when Raymond VII submitted to Capetian terms at the treaty of Paris in 1229. Besides accepting reduced lands and the prospect of their absorption after his death into Capetian lordship, Raymond agreed to assist in the suppression of heresy, a tacit admission that the crusade had failed in its primary aim. Over the following decades heresy was rooted out, occasionally by military force, as with the siege and capture of the Cathar stronghold of Montségur in 1244, but more conclusively by the alliance of the new political and ecclesiastical establishments championing direct evangelism, especially by friars, and new processes of clerical inquisition, legal intimidation and punishment. While pivotal in the political reordering of southern France, the crusades had proved ineffective in creating an obedient Catholic community cleansed of error. Yet the former proved vital in the subsequent achievement of the latter, once more confirming the ineradicable fusion of the secular and spiritual, the cultural rationale of crusading in the first place.

The Extension of Crusading

The Albigensian crusades let the genie out of the bottle. Accusations of heresy and schism against a protean array of opponents flowed freely. The association of crusading and the defence of rights suited political contests, such as the civil wars in England in 1215–17 and 1263–5: at the battle of Evesham in 1265 both royalists and rebels wore crusade crosses (respectively red and white). On one occasion, in Germany in 1240, a pseudo- or anti-crusade, complete with preaching, giving the cross and granting of indulgences, was directed against a papal legate promoting a crusade against King Frederick II.21 Crusades were directed against the Colonna family in Italy (1297–8), enemies of Pope Boniface VIII (1294–1303), and to crush the disruptive northern Italian charismatic cult of Fra Dolcino (1306–7). As a tool of social and political discipline, crusading became a weapon of choice for rulers who energetically (and not always successfully) petitioned popes for access to crusade indulgences and money.

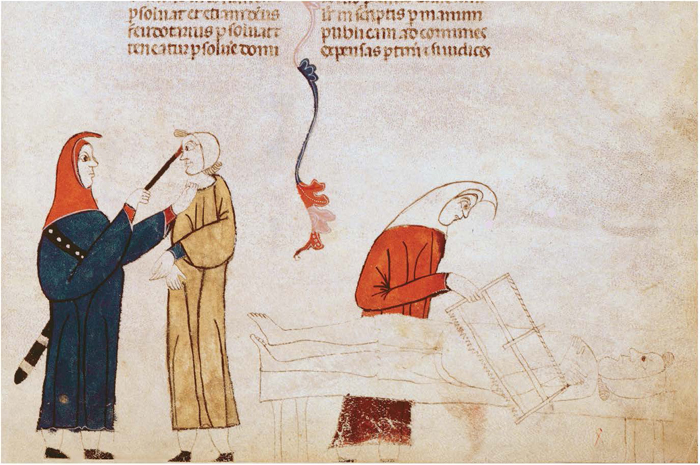

114. From the Customs of Toulouse, 1296: torture.

115. Heretics thrown to the fire.

Papal enthusiasm could be impressive. Gregory IX (1227–41), a canon lawyer and veteran crusade preacher, demonstrated particular versatility in authorising, with careful legal justification, full-blown crusades or the reward of plenary indulgences. Targets included the supposedly heretical Stedinger peasants in the Lower Weser valley (1232–5) and German heretics more generally (1228–32, 1233–4); Bosnians suspected of heresy and inadequate orthodoxy (1233–8); Italian heretics and their alleged protectors (1231, 1235); Greek Orthodox rulers (1231, 1235–8); the Bulgarian King John Asen (1238), who threatened the Latin empire of Constantinople established in 1204; and Russian Orthodox enemies of the Teutonic Knights (1240). Gregory’s eagerness provided precedents for his successor, the even more distinguished canon lawyer Innocent IV (1243–54), whose crusade attention fell on Bosnians, Italian heretics, Greeks and Sardinians. For both Gregory and Innocent, the main enemies were the Hohenstaufen: Frederick II, his descendants and their supporters.

The Hohenstaufen

The wars against the Hohenstaufen provided the most dramatic example of the crusade used to redress a political problem, in this case the prevention of territorial encirclement of papal lands in Italy by Emperor Frederick II (1197–1250). Indelible distrust between successive popes and what Urban IV (1261–4) called a ‘viper race’ prevented a settlement, the feud becoming increasingly venomous under a succession of popes: Gregory IX, Innocent IV, Alexander IV (1254–61), Urban IV and Clement IV (1265–8). Frederick had first been excommunicated in 1227; a campaign against him led by the former king-regent of Jerusalem John of Brienne in 1228–30 had attracted clerical taxes. However, only after Frederick had again been excommunicated in March 1239 did Gregory IX declare a crusade against him in the winter of 1239–40, hoping to reassure local allies and extend support in northern Italy and Germany where, renewed in 1240 and 1243, the crusade was preached. The full vial of papal vitriol was liberally poured on the Hohenstaufen as schismatics, heretics, harbingers of the Anti-Christ, fomenters of disorder and covert Muslims. After Innocent IV had deposed Frederick at the First Council of Lyons (1245), anti-kings were set up in Germany (Henry Raspe of Thuringia, 1246–7; William of Holland, 1247–56), perhaps encouraged by funds generated by the crusade. Thereafter, the crusade provided a focus and respectable cover for local rivalries in Italy and Germany as well as papal hostility that persisted after Frederick’s death. Crusades continued in Germany against his son Conrad IV (1250–4) and his illegitimate son, Manfred (regent, then, after 1258 king of Sicily; d. 1266), in Italy where, after 1254, the military action took place. In 1255, Henry III of England accepted from Alexander IV the crown of Sicily on behalf of his second son, Edmund, the pope wishing to harness the resources of a secular kingdom to the cause. English involvement failed to materialise, as Henry’s optimistic financial guarantees almost cost him his throne when leading English magnates rebelled at what they saw as the cost and caprice of the ‘Sicilian Business’. In place of the English, Urban IV and Clement IV enlisted Louis IX of France’s youngest brother, Charles of Anjou (d. 1285), to tackle Manfred. Following a swift, daring campaign in the winter of 1265–6, Charles defeated and killed Manfred at the battle of Benevento (February 1266). In 1268, Charles repulsed an attempted Hohenstaufen restoration, defeating Conrad IV’s son Conradin at Tagliacozzo (in August) and executing him in Naples (October), the last Hohenstaufen in the male line.

The anti-Hohenstaufen wars further embedded crusading in western European politics. Crusades were directed against Ezzelino and Alberigo of Romano (1256) (see ‘A Day in Venice’, p. 356); Sardinia (1263); and English rebels (1263, 1265). After a Sicilian revolt against Charles of Anjou in 1282 (the so-called Sicilian Vespers) and the occupation of the island by Frederick II’s son-in-law, Peter III of Aragon, a fresh crusade was promulgated (January 1283), which led to a disastrous invasion of Aragon by Philip III of France (1270–85) in 1285. Fresh crusading was instituted when Frederick of Sicily (1296–1337), younger son of Peter III, refused to surrender the island to the Angevins. Only the treaty of Caltabellota in 1302, which left Sicily in Aragonese hands, ended the Sicilian crusades.

116. Charles of Anjou and Manfred.

The Later Middle Ages

In the fourteenth century, Italy remained the chief arena for crusades against Christians. They were employed when Louis IV attempted to revive German imperial claims in the peninsula (1328–30); to prevent Venetian control of Ferrara (1309–10); and against anti-papal (so-called Ghibelline) city rulers, or signori, prominently the Visconti of Milan. (Florence and Naples tended towards the papal – Guelph – side.) However, alliances were necessarily fluid: in 1334, Guelph Florence joined Milan to prevent a papal scheme to erect a Lombard puppet state. Defence of the Papal States, orchestrated by cardinal-legates, such as Bertrand du Poujet after 1319 and Gil Albornoz after 1353, regularly employed crusades. This was chiefly in order to allow the papacy, now settled in Avignon (1309–76), to raise huge sums of money to pay for the wars against Milan (1321, 1324, 1360, 1363, 1368); Ferrara (1321); Mantua and Ancona (1324); Cesena and Faenza (1354). In 1357, 1361 and 1369–70 crusades were directed against freelance mercenary companies (routiers) in the peninsula. Despite conventional rhetoric and privileges, these Italian crusades were restricted to regional politics and local recruitment. Outside Italy, successive popes declined to gild other temporal conflicts with the cross, whether French ambitions on Flanders or the Hundred Years War.

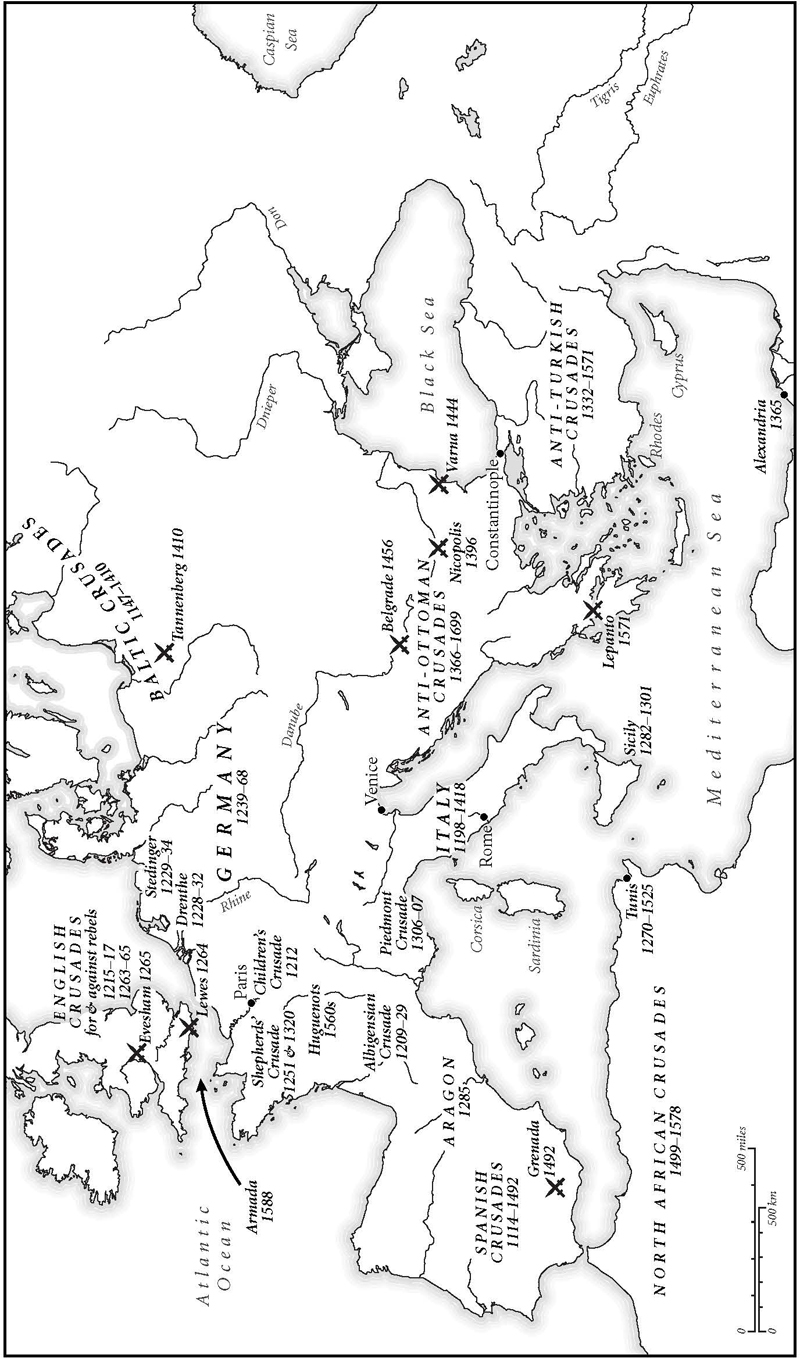

16. Crusades against Christians in Europe, fourteenth–sixteenth centuries.

A DAY IN VENICE, 1258

By the thirteenth century, crusade preachers were well used to employing props and histrionic devices in support of oral rhetoric. However, few could have outdone the scene that unfolded in Venice’s Piazza San Marco sometime in 1258,22 as recorded by the gossipy judgemental Franciscan, Salimbene de Adam (1221–c. 1289). A crusade had been authorised by Pope Alexander IV against the supposedly tyrannical and – in hostile accounts – sadistic ruler of Treviso, Alberigo of Romano, at the time a supporter of the anti-papal Hohenstaufen. One of Alberigo’s alleged atrocities had been the abuse of thirty Treviso noblewomen who had been stripped of their clothes below their breasts and forced to watch their husbands, sons, brothers and fathers being hanged before expulsion from the city. Apparently they made their way to Venice where the papal legate (identified by Salimbene as Cardinal Ottaviano degli Ubaldini), feeding off public outrage, theatrically exploited their predicament to excite the crowd: ‘in order to anger the people more against Alberigo . . . the cardinal . . . had the women come forth in the same shameful and nude condition that the wicked Alberigo had reduced them to’.23 To reinforce his message that the demonised Alberigo needed to be combated by force, the legate rehearsed a string of the more bellicose revenge texts from the Bible before, amid cries of ‘So be it! So be it!’, and by popular demand, he preached and dispensed the cross to the hysterically enthusiastic audience. Salimbene attributed such mass fervour to a combination of deference to the legate, the attraction of indulgences and the witness to Alberigo’s crimes. The friar’s account is lurid, probably more than a little embroidered: if the show did occur, the cardinal may have used actors, as the idea that he, let alone the women themselves, would have agreed to any such a public naked parade defies credulity. Yet, however formal or imaginative, the essential outline features of Salimbene’s story are consistent with many other descriptions of crusade sermons: the emphasis on the lure of spiritual reward; the explicit scriptural support for the justice of authorised violence; the power of atrocity narratives; the validation of reciprocal popular consent; and the skilled mechanics of crowd manipulation, from rhetoric to theatricals and crowd chanting. Effective preaching of the cross, whether outside St Mark’s or elsewhere, involved entertainment as much as conviction.

117. The Venice piazza in Bellini’s Procession of the True Cross.

The rivalries of the Great Schism (1378–1417) provided new crusading opportunities: the Roman Pope Urban VI against his Avignon rival Clement VII (1378); both Roman and Avignon popes authorised crusades during succession wars in Naples (1382, Clement VII; 1411 and 1414, John XXIII). Urban VI associated the crusade with Bishop Despenser of Norwich’s campaign in Flanders in 1383. This was no casual association. Bishop Despenser milked the traditional symbolism in a dramatic performance when he assumed the cross at a ceremony in December 1382 at St Paul’s Cathedral in London, the bishop lifting then carrying a large, heavy cross onto his shoulders in a physically theatrical display of observing the central crusading command of Christ to ‘take up his cross’.24 The crusade still provided incentives, not least financial. Despenser’s crusade, for instance, offered the English government a cheap, if in the event drearily unsuccessful, French campaign, while crusade bulls elevated the status of John of Gaunt’s bid to become king of Castile in 1386. However, the nature of the schism meant that neither side’s crusades had access to adequate church taxes to underwrite substantial campaigns. At the same time papal universalist claims underpinning crusade theory were degraded even if crusading against overt heretics, pagans, Mamluks and Ottomans retained cultural lustre. Following the end of the schism in 1417, popes refrained from using the crusade to defend the Papal States until Julius II (1503–13) briefly revived the habit in Italy. Julius also afforded crusade status to Henry VIII of England’s French campaign of 1512–13. Crusade detritus still littered the political landscape. Occasionally, as in Hungary in 1514, it became enmeshed in civil revolt, although in this case the crusaders’ violence was provoked by the Hungarian nobility’s reluctance to fight Ottomans.

The exception to the decline in crusades against Christians came with six crusades fought against the Hussites of Bohemia (1420, 1421, 1422, 1427, 1431, 1465–71) and another planned (1428–9) and with a rhetorically grand but, in execution, petty and squalid assault on Waldensian communities in Savoy (1488). The Hussites combined organised religious radicalism – vernacular texts, distinct liturgies, Bible-based theology, and a rejection of traditional ecclesiastical authority – with the political cause of anti-German Czech nationalism. This gained it important allies among the Bohemian nobility. A policy of a crusade to crush Hussite heresy attempted to demonstrate the new unity of the western Church after the end of the papal schism (1417) and successfully drew international attention and support across western Europe. However, the continuing Hundred Years War sapped Franco-English support. The leadership of the German Emperor Sigismund (king of Hungary, 1387–1437; of Germany, 1411–37), also king of Bohemia (1419–37), emphasised how far the crusades were enmeshed in discrete regional politics, with religion forming only a part of the cause of conflict. The crusaders’ successive military failures between 1420 and 1431, coupled with their indiscriminate violence, served to reinforce Czech identity and independence while hardly adding lustre to the crusade as a weapon against Christian European powers. The 1465–71 crusade concerned politics and diplomacy rather than faith; Bohemia had long since been recognised by fellow rulers less as a rogue state and more as a potential partner. Inevitably, the following century, the Reformation stimulated revived crusade talk, but talk it chiefly remained (see Chapter 12).25

Criticism and Opposition

Given the pre-1095 tradition of holy war and the kudos of the Jerusalem war, the use of crusading against Christians was inescapable. Its rapid extension in the thirteenth century rested on clearer categories of holy and just war, the arrival of a settled theology of plenary indulgences and the new availability of funds. Inevitably, crusades against Christians aroused controversy. Victims and opponents naturally objected: Languedoc poets loudly lamented the rape of their land and culture.26 Such crusades could easily be characterised as tawdry political and financial rackets, sometimes with justice. The popes’ arguments that their enemies were distracting efforts to help the Holy Land could be turned back on them. In the thirteenth century, otherwise crusade sympathisers condemned papal wars against the Hohenstaufen in Italy and Germany. Clergy, such as the rectors of Berkshire in 1240, resented taxation for them. English and French nobles objected to attempts to force them to commute their Holy Land vows to fight the Greeks in the 1230s and 1240s. Opponents were found from citizens of Lille in 1284 to Florentines who refused to permit crusade legacies to be diverted. The papalist preacher and canon lawyer Hostiensis ran into trouble on an anti-Hohenstaufen preaching tour of Germany where he was heckled by crowds who preferred the Holy Land crusade. The diversion of church taxes granted in 1274 and 1312 from the Holy Land to Italy appeared fraudulent. Wars in the Holy Land and against pagans and heretics retained primacy of respect; those against fellow Christians attracted limited international approval and inconsistent papal enthusiasm. While Gregory IX, Innocent IV, Clement IV, Boniface VIII or John XXII (1316–34) eagerly promoted such wars, Gregory X (1271–6) or Nicholas IV (1288–91) worked for internal peace in pursuit of a new eastern expedition. The curia was not deaf to critics: in 1246, Innocent IV wished his order to stop preaching the Holy Land crusade in favour of the Hohenstaufen crusade to remain secret.27 As the disgruntled responses of crucesignati in the 1230s and 1240s showed, the coincidence of different crusade objectives caused unease. To some in the later thirteenth century, the erosion of Outremer while crusades in Italy intensified appeared deplorable.

118. Hussite wars.

However, the German and Italian crusades elicited support, chiefly from those with immediate political interests in play. Crusades against Christians failed to tarnish other wars of the cross and played only a subordinate part in attacks on papal authority. The English radical theologian John Wyclif’s coruscating attack on Despenser’s Crusade of 1383 fitted wider anxieties exposed by the crisis of the Great Schism. Papal crusades against Christians produced some dramatic political successes: the conquest of Languedoc; Charles of Anjou’s success in Sicily; the destruction of the Hohenstaufen. Yet papal territory remained insecure and the aura of sanctity wore very thin during the interminable Ghibelline–-Guelph wars. As with crusade grants in Iberia and elsewhere, the later Middle Ages saw crusades against Christians become financial expedients. By the early fifteenth century, even that failed to compensate.