Chapter 27. Microsoft Operating System Features and Tools, Part 2

This chapter covers a portion of the following A+ 220-1002 exam objective:

• 1.5 – Given a scenario, use Microsoft operating system features and tools.

There is so much to discuss when it comes to Windows features and utilities. That’s why I split this objective into two chapters. In this chapter we’ll complete the objective by describing Disk Management, and then covering a slew of system utilities. Onward!

1.5 – Given a scenario, use Microsoft operating system features and tools.

ExamAlert

This portion of Objective 1.5 concentrates on: Disk Management; and system utilities (such as Explorer, System Restore, and Regedit).

Disk Management

The information in this section applies to working with new drives that are designated for operating system installation, as well as drives that have already been installed to. Either way, the concepts of partitioning and formatting remain the same. Regardless of what you are doing with the drive, the proper order for drive preparation is to partition the drive, format it, and then copy files to your heart’s delight. However, sometimes you might also need to initialize additional drives within Windows; this would be done before partitioning. All of these things can be done within the Disk Management program.

The Disk Management Utility

The Disk Management utility within Computer Management is the GUI-based application for analyzing and configuring hard drives. (Run > diskmgmt.msc). You can do a lot from here, including the following:

• Initialize a new drive: A secondary hard drive installed in a computer might not be seen by File/Windows Explorer immediately. To make it accessible, locate the drive (for example, it might be referred to as Disk 1), right-click where it says Disk 1, Disk 2, and such, and then select Initialize Disk. When you install an OS to the only drive in the system, it is initialized automatically.

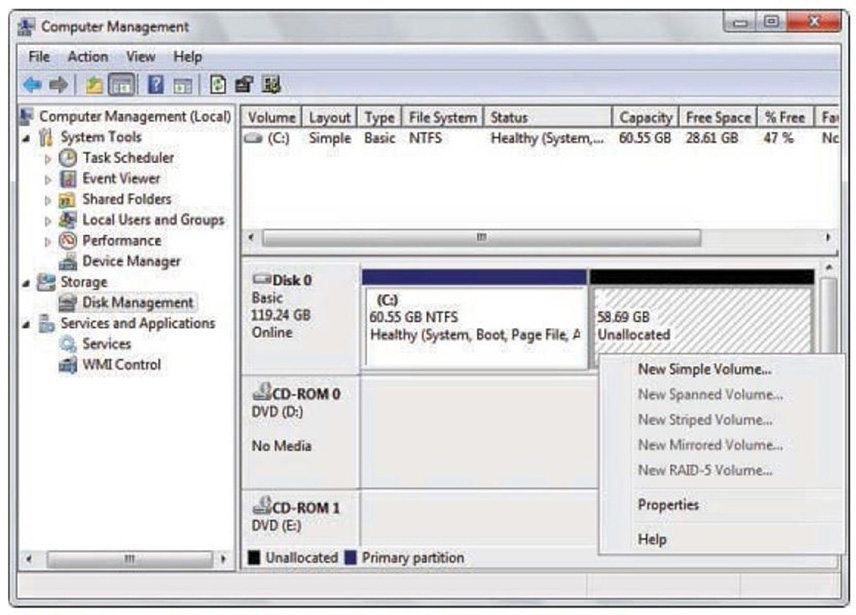

• Create volumes, partitions, and logical drives: When creating these, Windows generally refers to them simply as volumes, but you will also see the terms partition and logical drive. Regardless, you must right-click the area with the black header named unallocated. Figure 27.1 shows an example of creating a new simple volume by right-clicking that area.

Figure 27.1 Creating a volume within unallocated disk space

• Format volumes: When formatting, select the file system (NTFS usually) and whether to do a quick format. Remember: quick formats are usually the way to go, but if you leave this option unchecked (for a full format), it will take much longer, and could reduce the lifespan of the drive. When you format the partition, you must select a drive letter, such as C: or E: or F:, and so on. You can change drive letters in the future, but it’s a good idea to plan it out beforehand. You can use up to Z:, but you probably won’t need to; regardless, keep a few open in the case that you need to map a network drive in the future.

Note

WARNING: ALL DATA WILL BE ERASED during the format procedure.

• Make partitions active: Partitions need to be set to active if you want to install an operating system to them.

• Convert basic disks to dynamic: Basic disks can have only simple volumes or regular partitions/logical drives. If you want to create a spanned, striped, mirrored, or RAID-5 volume, you need to convert the disk to dynamic. This is done by right-clicking the drive where it says Disk 0 or Disk 1, for example, and selecting Convert to Dynamic Disk. It’s highly recommended that you back up your data before attempting this configuration.

• Extend, shrink, and split volumes: A volume can also be extended, shrunk, or split if you have converted it to a dynamic disk. Just about any volume can be shrunk or split, but to extend a volume, you need available unallocated space on the drive. By shrinking a volume that takes up the entire hard drive, you can also ultimately split that partition into two pieces, allowing you to better organize where the OS is stored and where the data files are stored.

You might ask: What is the difference between a partition and a volume? The partitions are physical (and logical) divisions of the drive. A volume is actually any space among one or more drives that receives a drive letter.

You can also see the drive at the top of the window shown in Figure 27.1 and its status. For example, the C: partition is healthy. You also see it is a System partition, which tells you that the OS is housed there. It also shows the capacity of the drive, free space, and percentage of the drive used. What’s more, this section tells you if the drive is basic or dynamic or if it has failed. In some cases, you might see “foreign” status. This means that a dynamic disk has been moved from another computer (with another Windows operating system) to the local computer and it cannot be accessed properly. To fix this and access the drive, add the drive to your computer’s system configuration. This is done by right-clicking the drive and then clicking Import Foreign Disks. Any existing volumes on the foreign drive become visible and accessible when you import the drive.

Mount Points and Mounting a Drive

You can also “mount” drives in Disk Management. A mounted drive is a drive that is mapped to an empty folder within a volume that has been formatted as NTFS. Instead of using drive letters, mounted drives use drive paths. This is a good solution for when you need to work with disc or OS images. It’s also helpful in the uncommon case that you need more than 26 drives in your computer because you are not limited to the letters in the alphabet. Mounted drives can also provide more space for temporary files and can allow you to move folders to different drives if space runs low on the current drive. To mount a drive:

1. Right-click the partition or volume you want to mount and select Change Drive Letters and Paths.

2. In the displayed window, click Add.

3. Then browse to the empty folder you want to mount the volume to, and click OK for both windows.

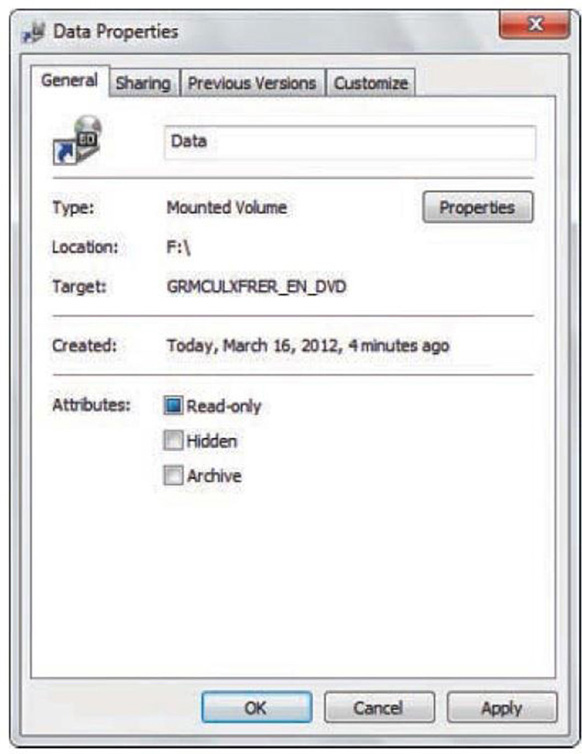

As shown in Figure 27.2, the DVD-ROM drive has been mounted within the Data folder on the F: volume on the hard drive. It shows that it is a mounted volume and shows the location of the folder (which is the mount point) and the target of the mount point, which is the DVD drive containing a Windows DVD. To remove the mount point, just go back to Disk Management, right-click the mounted volume, select Change Drive Letters and Paths, and then select Remove. Remember that the folder you want to use as a mount point must be empty, and it must be within an NTFS volume.

Figure 27.2 An empty NTFS folder acting as a mount point

Storage Spaces

Windows 8 and newer, as well as Windows Server 2012 and newer, incorporate a technology called Storage Spaces. This enables the Windows user to virtualize storage by grouping physical hard drives into storage pools and then creating virtual drives called storage spaces from the available capacity in the storage pools. The physical drives (or arrays of drives) need to be SATA or Serial Attached SCSI (SAS). This tool can be accessed by typing spaces in the Search field or by going to Control Panel > System and Security > Storage Spaces. From here, multiple drives can be selected and used collectively as a “pool.” From within that pool you can then create a storage space. There are four main types of storage spaces that can be selected:

• Simple, which is similar to RAID 0 and has no fault tolerance

• Two-way mirror, which is similar to RAID 1 mirroring

• Three-way mirror, which is similar to RAID 10

• Parity, which is similar to RAID 5

The concept is similar to RAID in that you are either looking to increase performance, or more likely, want fault tolerance. But remember, a hardware-based RAID solution is usually the more effective option, but it will all depend on your environment. If you do use Storage Spaces, consider downloading the Diskspd Utility from the Microsoft TechNet (or similar tool), which can test the speed and efficiency of the storage space array. This can help you to verify quantitatively if your array is working at peak performance.

ExamAlert

Know that drives are grouped together into a storage pool. The storage capacity from that pool is then used to create Storage Spaces.

Optimize Drives/Disk Defragmenter

Over time, data is written to the drive and subsequently erased, over and over again, leaving gaps in the drive space. New data will sometimes be written to multiple areas of the drive in a broken or fragmented fashion by filling in any blank areas it can find. When this happens, the hard drive must work much harder to find the data it needs—spinning more and starting and stopping more (in general, more mechanical movement). The more the drive has to access this fragmented data, the shorter its lifespan becomes due to mechanical wear and tear. Also, the computer will run slower and continually get worse until the problem is fixed. A common indicator of this is when the hard drive LED constantly shows activity. When this happens, you need to rearrange the file sectors so that they are contiguous—you need to defragment!

Defragmenting the drive can be done with Microsoft’s Optimize Drives utility (Disk Defragmenter in Windows 7), with the command line utility defrag.exe, or with third-party programs. The Optimize Drives utility is actually listed within the Administrative Tools in Windows 10 and 8 as “Defragment and Optimize Drives”, but when it opens, the title will simply say “Optimize Drives”. You can also search for the utility by typing “defragment” in the search field, or open it directly from the Run prompt and typing dfrgui.exe. In Windows 7, navigate to Start > All Programs > Accessories > System Tools > Disk Defragmenter.

This program can be used to analyze your drives for fragmentation, remove fragmentation, and schedule periodic examinations. You can also access this utility by right-clicking a volume in Explorer, selecting Properties, then clicking the Tools tab, and finally clicking Optimize. Either way, the ultimate goal is to make the data contiguous—moving and reorganizing it so that it is not fragmented, or at least, as fragmented.

If you are using the Disk Defragmenter program, you need 15 percent free space on the volume you want to defrag. If you have less than that, you need to force the operation by using the command line option defrag -f.

ExamAlert

Know how to access the Optimize Drives/Disk Defragmenter utility in Windows, and know the defrag command in the Command Prompt.

If you do initiate a defrag, it could take a while, so it’s best to do this off-hours. After it completes, a restart is recommended.

System Utilities

This CompTIA A+ objective covers a bit of a hodge-podge of system utilities, from basic utilities such as Notepad to advanced utilities such as the Registry Editor. We’ll start with some basic ones, and progress through the section to the more advanced ones. As usual, take it slow, and try to digest them one at a time.

Notepad

This is Windows’ built-in text editor. You can find it by typing “notepad” in the Search field or the Run prompt. It’s also located in Windows 10 at Start > Windows Accessories. While you can format the text to a certain extent, this is the tool to use when you need to write, or copy plain text with no formatting. It can also be helpful for creating scripts and batch files, or doing web developing, though I would recommend other tools for those jobs. (Feel free to contact me at my website to ask what tools I currently use.)

Note

In the old days of Windows, you could edit text within the command line with the edit command. That was when you could use the command line called “command.com”. However, that version of the command line was replaced by cmd.exe long ago, so the built-in command-line text editor is no longer. However, you can install third-party tools to edit text in the Command Prompt, or use the PowerShell.

Explorer

You probably use Explorer quite often; it is the default file browser in Windows. Windows 10 and 8 call it File Explorer, whereas Windows 7 and earlier call it Windows Explorer. To keep it simple, we’ll just call it “Explorer” and that is how you can access it from the Run prompt (Run > explorer.exe). You can also get to it by pressing Windows + E on the Keyboard. In Windows 7 you can navigate to it by going to: Start > All Programs > Accessories > Windows Explorer. In Windows 10, navigate to: Start > Windows System > File Explorer.

Most importantly, users work with Explorer to open, move, copy, and delete files and folders from: local drives, mapped network drives and through browsing the network. There is a group of folders associated with each user account on the computer, including desktop, documents, downloads, music, pictures, and videos. These are displayed at the top of the left-hand window pane, but they are logically stored within C:\Users\%userprofile%, where %userprofile% equals the name of the currently logged in user. Under that you see all of the volumes on the computer, for instance C:, D:, E:, including local drives and mapped network drives. Then you see the Network section which is used for browsing. (In some versions of Windows, you will see the HomeGroup option, though that has been removed from Windows 10.

Interesting note: Explorer is a morphing tool. It changes depending on what you click on. For example, in Windows 10 if you click on the C: drive in the left-hand window pane, you will see options at the top of the screen including copy, paste, delete, and so on. However, if you click on This PC, the options change to things such as Properties, Map network drive, and Manage. If you click on Network, you get options that deal with networking, such as the Network and Sharing Center. So, Explorer becomes a great place to go to initiate all kinds of different work with files, and has plenty of links to other places where you would configure Windows.

Windows Update

As with any OS, Windows should be updated regularly. Microsoft recognizes deficiencies in the OS—and possible exploits that could occur—and releases patches to increase OS performance and protect the system. These patches can be downloaded and installed automatically or manually depending on the user’s needs, or the organization’s needs, and are controlled via the Windows Update program.

Windows Update can be accessed in Windows 10 by going to Settings > Update and Security > Windows Update (or by searching for it). In Windows 8 and 7 it is located within the Control Panel. There is no executable name for it, because Windows Update is a service, not an application. However, you can update the system from the command line if necessary.

From within Windows Update you can decide how updates will be delivered and installed. In Windows 7 and 8 you can disable checking for updates altogether, but with Windows 10 you can only defer updates—unless… you do one of the following: stop and disable the Windows Update service in the Services console window (or in the command line); disable it with the Group Policy Editor, disable it within the Registry, or otherwise turn it off programmatically. Sometimes, larger organizations will do this—in a more Enterprise manner—so that Windows is not randomly updating computers on the network and causing functionality issues between systems.

At times, individual Windows updates, or the Windows Update program itself can fail. To troubleshoot an issue, use the Windows Update Troubleshooter program which can be downloaded from Microsoft’s website. Also, view the Windowsupdate.log file (located in %windir%) to see the failure errors. See the following links for more information about Windows Update troubleshooting and a list of error codes:

https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/windows/deployment/update/windows-update-troubleshooting

https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/windows/deployment/update/windows-update-error-reference

System Information/msinfo32

Another tool that Windows offers for device analysis is the System Information tool. This can be accessed in all versions of Windows by opening the Run prompt and typing msinfo32.exe. (Typing .exe actually isn’t necessary by default.) From here, you can view and analyze information about the hardware components, the software environment, and the hardware resources used, but you cannot make any changes. You view this information for the local computer and for remote computers as well by typing the name or IP address of the system you want to analyze.

System Restore

This tool can be used to create a snapshot of the state of the operating system and store it for later retrieval. It can be very helpful when troubleshooting the system.

System Restore can fix issues caused by defective hardware or software by reverting back to an earlier point in time. Registry changes made by hardware or software are reversed in an attempt to force the computer to work the way it did previously. Restore points can be created manually and are also created automatically by the operating system before new updates, applications, or hardware is installed.

To create a restore point in Windows:

1. Open the System window and then click the System Protection link. This displays the System Protection tab of the System Properties dialog box, as shown in Figure 27.3. Alternatively, you could go to Run, and type systempropertiesprotection.

Figure 27.3 The System Protection tab of the System Properties dialog box

2. Click the Create button. This opens the System Protection dialog box.

3. Type a name for the restore point, and then click Create.

If System Restore is not available, it might be turned off. There are several reasons why a person might turn it off (for example, if the system had been scanned for viruses recently).

To enable or disable System Restore in Windows, click the Configure button within the System Protection tab of the System Properties dialog box. From here you would click the radio button for Turn on system protection in Windows 10 and 8. In Windows 7, you would click Restore system settings and previous versions of files (on the system drive, usually C:) or you would click Restore previous versions of files (on other drives containing data only).

System Restore is kind of like using a time machine (if one actually existed). It allows you to reset the computer to an earlier configuration—hopefully, one that functioned properly. To actually restore the computer to an earlier point in time, just click the System Restore button on the System Properties/System Protection dialog box and then follow the instructions. But beware, some applications might be removed, and drivers might be uninstalled.

Note

If the system won’t boot normally, you can also attempt to run System Restore from Safe Mode or you can use the Windows Recovery Environment/System Recovery Options. We’ll talk about those troubleshooting techniques in the troubleshooting section of this book.

ExamAlert

Understand how to enable and disable System Restore, how to create restore points, and how to restore the system to an earlier point in time.

Remote Desktop Connection/MSTSC

Remote Desktop Connection is a Microsoft tool used to control and work on remote Windows systems. It displays the remote OS in a window on your desktop. It works as a client and a host in Windows Pro and higher editions, but only as a client in Home editions. The executable name is MSTSC so you can use that in the Run prompt or command line to open the program, and to connect directly to systems. We’ll discuss this more in Chapter 29, “Windows Networking.” Remote Desktop Connection is included in Windows, but you can also download a more robust and organized version of the program called Remote Desktop Connection Manager. Technicians often simply refer to these as RDP, which is short for Remote Desktop Protocol—the underlying networking protocol that supports the program.

DxDiag

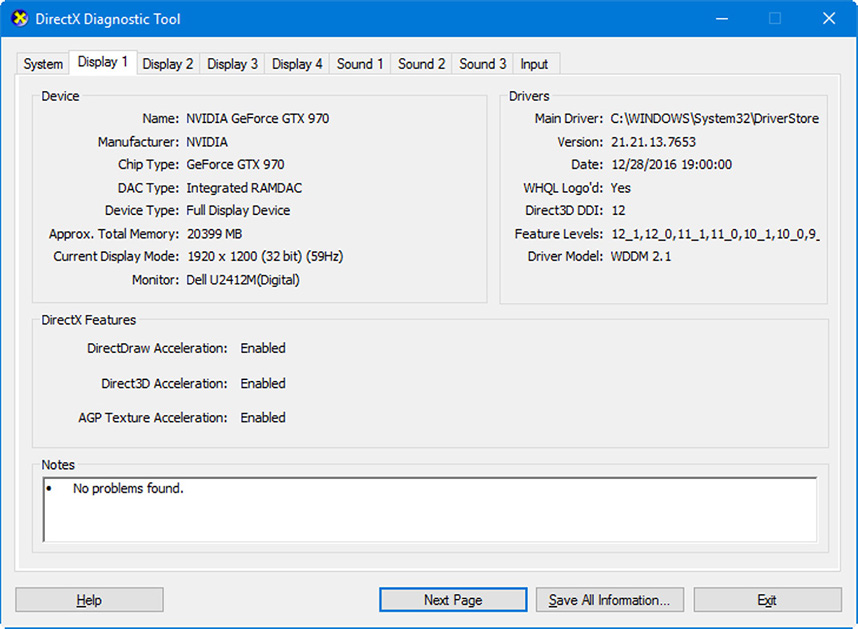

When it comes to making sure your devices work properly, one of the most important devices is the video card; a utility you can use to analyze and diagnose the video card is the DirectX Diagnostic Tool (also known as DxDiag). To run this, open the Run prompt and type dxdiag. Depending on the version of Windows and the configuration, the utility might ask if you want it to check whether the corresponding drivers are digitally signed. A digitally signed driver means it is one that has been verified by Microsoft as compatible with the operating system. After the utility opens, you can find out what version of DirectX you are running. DirectX is a group of multimedia programs that enhance video and audio, including Direct3D, DirectDraw, DirectSound, and so on. With the DxDiag tool, you can view all the DirectX files that have been loaded, check their date, and discern whether any problems were found with any files. You can also find out information about your video and sound card, what level of acceleration they are set to, and you can test DirectX components such as DirectDraw and Direct3D. The DirectX feature is important to video gamers and other multimedia professionals. Figure 27.4 shows an example of the Display tab within the DirectX Diagnostic Tool running on a Windows 10 Pro computer that has DirectX 12 installed.

Figure 27.4 Windows 10 DxDiag window showing the Display tab

The Windows Registry

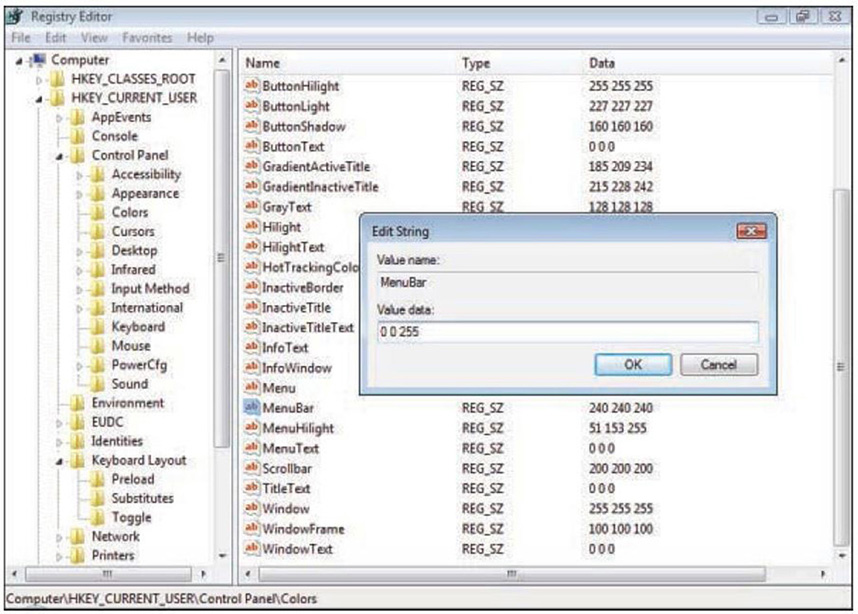

Left this one for last! The Windows Registry is a database that stores the settings for Windows. It contains hardware and software information and user settings. If you cannot make the modifications that you want in the Windows GUI, the registry is the place to go (aside from the command line). To modify settings in the registry, use the Registry Editor, which can be opened by typing regedit.exe at the Run prompt. This displays a window like the one shown in Figure 27.5.

Figure 27.5 The Registry Editor in Windows

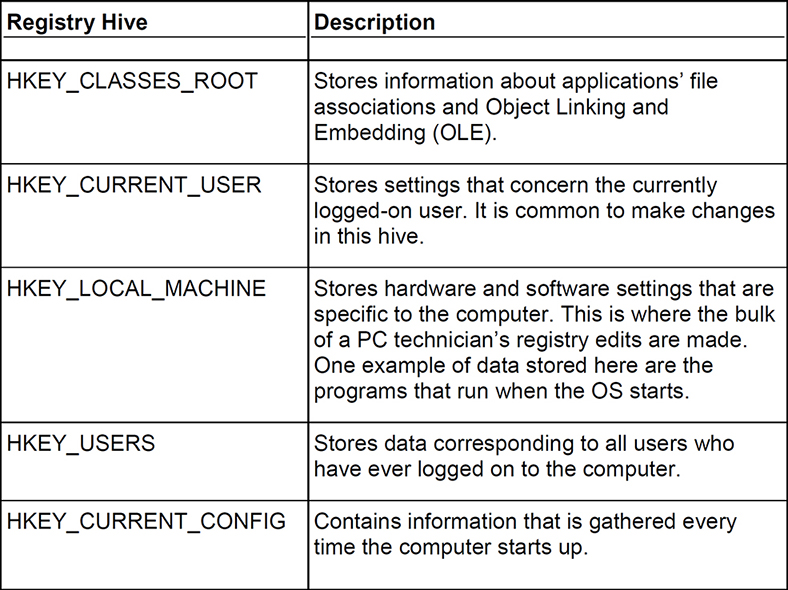

The registry is divided into several sections, known as hives, and these hives begin with the letters HKEY. Table 27.1 describes the five visible hives in the Registry Editor.

Table 27.1 Description of Registry Hives in Windows

Hives are also known as keys that contain other keys and subkeys. This forms the organizational system for the registry. It is similar to folders and subfolders within Windows Explorer or File Explorer. However, the registry does not store actual data files; it stores settings. Inside the keys and subkeys are registration entries that contain the actual settings. These can be edited or new entries can be created. The types of entries include

• String values, which are used for decimal numbers

• Binary values, which are used for binary entries

• DWORD and QWORD entries, which are used for binary and hexadecimal entries

• Multistring values, which can have a variety of information

Registry hives are stored in \%systemroot%\System32\Config.

Many users fear the registry, but the technician need not. Just follow a couple simple rules: 1) Back up the registry before making changes and 2) don’t make modifications or additions until you have a thorough understanding of the entry you are trying to modify or add.

Figure 27.5 shows a registry entry called MenuBar within HKEY_CURRENT_USER\Control Panel\Colors. By double-clicking the MenuBar entry, an Edit String window appears (as shown). Again, the beauty of the registry is that you can make modifications to things that normally can’t be modified in the Windows GUI. MenuBar is one of these examples. In the figure, the entry’s string value has been changed to 0 0 255, which means the color blue. To effect this change, click OK, close the Registry Editor (no saving necessary), and then log off and log back on. Some registry changes require a reboot of the system.

As previously mentioned, you need to know how to back up the registry. You can back up any individual key or the entire registry. Say a user wanted to back up the Colors subkey before making changes to the MenuBar entry. The proper procedure would be to highlight the Colors subkey, click File on the Menu bar, and then select Export. Then it’s as simple as selecting a location to save the registry entry and naming it. It exports as a .reg file.

A typical subkey like this is about 2 KB in size. Backing up the entire registry can be done in two ways. First, you can do this by highlighting Computer, selecting Export, and saving the file. The other option is to select any registry key, select Export, and in the Export Registry File window, select the All radio button in the Export range box.

Later, individual keys or the entire registry can be imported with the Import option on the File menu. You might need to do this if a registry modification caused a problem with the system. For example, certain changes to the registry could cause the GUI to fail to load. Or audio could become disabled. Again, be sure to make a backup before playing around with the registry. To repair a missing graphical interface or audio issue that is registry-related, attempt a System Repair from the Windows DVD or, if possible, restore an older version of a backed-up registry. (You will learn more about System Repair in the Windows troubleshooting section of this book.)

Finally, you can connect to remote computers to gain partial access to their respective registries. To do this, select File and then select Connect Network Registry. You can then browse for computers that are members of the same network your computer is a member of, connect to them, and then make modifications to those remote registries. Of course, you need to have administrative privileges on the remote computer.

ExamAlert

Know how to open the Registry Editor, modify entries, export the registry, and connect to remote registries.

Note

Don’t forget, I made that table of Run commands for you. For example: regedit.exe opens the Registry Editor. It’s available at this link:

https://dprocomputer.com/blog/?p=3010

Cram Quiz

Answer these questions. The answers follow the last question. If you cannot answer these questions correctly, consider reading this section again until you can.

1. You have been tasked with repairing a magnetic-based hard drive that is running sluggishly. Which of the following tools should you use to fix the problem? (Select the best answer.)

![]() A. Disk Management

A. Disk Management

![]() B. Optimize Drives.

B. Optimize Drives.

![]() C. Storage Spaces.

C. Storage Spaces.

![]() D. Mount point.

D. Mount point.

2. What is HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE considered to be?

![]() A. A registry entry

A. A registry entry

![]() B. A subkey

B. A subkey

![]() C. A string value

C. A string value

![]() D. A hive

D. A hive

3. Which of the following system utilities should be used to create a text file with no formatting?

![]() A. Notepad

A. Notepad

![]() B. Explorer

B. Explorer

![]() C. msinfo32

C. msinfo32

![]() D. Registry

D. Registry

4. A customer is having a problem connecting to mapped network drives but can connect to the Internet just fine. You are tasked with fixing that system. Which tool should you use to take charge of the system and analyze it?

![]() A. dxdiag

A. dxdiag

![]() B. mstsc

B. mstsc

![]() C. msinfo32

C. msinfo32

![]() D. dfrgui

D. dfrgui

![]() E. diskpart

E. diskpart

![]() F. System Restore

F. System Restore

5. What must you do first to a basic disk to create spanned, striped, mirrored, or RAID-5 volumes in Disk Management?

![]() A. Extend it

A. Extend it

![]() B. Shrink it

B. Shrink it

![]() C. Split it

C. Split it

![]() D. Initialize it

D. Initialize it

![]() E. Convert it to dynamic

E. Convert it to dynamic

Cram Quiz Answers

1. B. Use the Optimize Drives (Disk Defragmenter) utility. This will attempt to defragment the drive and place the files in a contiguous order so that the hard drive doesn’t behave so sluggishly. Of course, there could be other causes for the poor hard drive performance, such as malware, capacity issues, and so on. Disk Management is where you go to configure the hard drive but not to repair it—at least not directly. Storage Spaces is used to build software-based hard drive arrays. A mount point is a drive that is mapped to an empty folder; it is not a utility.

2. D. HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE is one of the five visible hives that can be modified from within the Registry Editor. This hive is where hardware and software settings that are specific to the computer are stored.

3. A. Use Notepad to create basic unformatted text files for use in programming, web design, batch files, and so on. Explorer is Windows’ graphical file manipulation tool. Msinfo32 is the executable that opens the System Information window. The registry is a database of settings in Windows, it is not a utility. To modify the registry, use the Registry Editor.

4. B. Use mstsc. That is the executable that opens the Remote Desktop Connection program which allows you to connect to the customer’s computer and take control of it—and hopefully analyzing and fixing the problem! Dxdiag opens the DirectX Diagnostics Tool. Msinfo32 opens the System Information window. Dfrgui opens the Optimize Drives utility. Diskpart is the command line version of Disk Management. System Restore is used to restore a Windows system to a previous point in time. By the way, mstsc stands for Microsoft Terminal Services Client—the original name for the program long ago… Know those utilities!

5. E. Convert the disk to dynamic. Once this is done, the volume can be extended, shrunk, or split. You would initialize a drive if it is not recognized by Windows immediately. For example, if it is a new or foreign drive that has been installed to a computer that already had Windows functioning.