Detail from Ancient Pathways (110 X 32cm). Incorporating versions of several important symbols described in this chapter, this large hand and machine-embroidered piece has a central panel representing the richness of cultural life and traditions. It is mostly made from metallic threads and fabrics, cut away to reveal a gold leaf ‘pathway’. In contrast, the panels on either side, representing earth, are very simply hand-stitched on a variety of joined and applied hand-made papers. More of this piece is shown on here.

Over time, people have taken the patterns they see around them in nature, have simplified them and bestowed symbolic meaning upon them. From these symbols meaningful patterns, characteristic of a particular group or culture, have been developed.

Pattern originates in the marks or signs used in a particular group:

• To communicate knowledge to others.

• To denote and establish identity and belonging.

• To mark territory.

• To give directional information.

These signs and their variations have been applied for thousands of years by people across the world. Whilst some signs may be distinct to one culture, many signs are universal and have been used by many civilizations over time and around the world, although they can mean different things to different people or tribes. However, it is known even in very early times, that travel was sufficiently widespread to allow for trade to take place as well as for territorial wars to be waged. In this way it is quite possible that ways of life, rituals and signs were transferred between communities.

Eventually, basic signs took on deeper and particular meanings, and began to symbolize special aspects of people’s surroundings and life.

‘A symbol is a word or sign whenever it “means” more than one sees at first glance.’

Carl Jung (Swiss psychiatrist and psychoanalyst, 1875–1961)

As discussed previously, in ancient times people living very close to nature were utterly dependent upon their environment for their survival and the continuation of their race. It is therefore understandable that their symbols were usually connected to the natural world and were often imbued with magical or spiritual properties that were part of ritual, worship and ceremony.

When symbols are repeated or combined, pattern or ornamentation is created. Not only does this answer the human need for repetitive, rhythmic decoration arising from the rhythms of natural life, it also binds people even more closely to their surroundings. René Smeets, author of Signs, Symbols and Ornaments refers to ornamentation as ‘the natural handwriting of mankind’.

Patterns, some of them quite complex, which have developed from meaningful symbols, can hold great ritualistic and religious significance for a culture. They create a distinctive visual language, a way of communication, including the telling of stories that are understood within the group. These patterns have been described as ‘saying things that cannot be said in words’.

It is thought that some origins of early pattern making were the marks or signs made with fingers or sticks in mud, sand or clay, perhaps scratched onto rocks and cave walls, or used on early pottery. The meaning of some of these is not at all clear, but it can be seen that dots and points develop into scratches, which become lines that go together to make many powerful symbols and patterns. It is generally accepted that the smallest line is a dot that can be developed into a dotted line, a line of small dashes, and then larger and larger dashes, eventually becoming a solid line.

A dot symbolizes the beginning or birth, the origin of life, such as a seed or a kernel. In pattern dots can be larger (small circles), filled in and can sometimes have small extensions (see diagrams above).

Pathway by Clyde Olliver. This sculptural piece, made from Welsh slate, is 158cm high. The long linear format is composed of graduated, textured, horizontal pieces of cut slate that have been carefully crafted to leave uneven zigzag edges that contrast beautifully with the strong, evenly placed stitches holding the horizontals to the supporting slate strip underneath.

As lines appear everywhere around us, delineating, creating and connecting shapes, it may seem very obvious to draw attention to the importance of line in pattern-making. But if we step back and look at how lines are constructed, the various forms that they can take, the arrangements that can be made and how these may be interpreted in stitch (after all, our threads and many embroidery stitches are linear), we can start to understand the infinite possibilities for making quite complex patterns from very simple beginnings.

The strength of line as a design and pattern-making tool is more easily appreciated when we discover the symbolic purpose of different single and groups of lines. The line is universal and, even in its simplest form, can be symbolic. Many meaningful patterns are formed by the way lines are configured and, if we accept that pattern is a visual language, it can be seen how these may be ‘read’.

Two small, subtle pieces from a series by Liz Hunter. The series explores possibilities for making whole patterned surfaces from ric-rac braid – a commercial haberdashery product largely out of fashion in recent years. Essentially experimenting with zigzag lines, the braid has been interlocked and hand-stitched in place. Small triangular spaces have been obtained in the upper piece by folding down some of the tiny points.

A vertical line is the sign of life, vigour and stability. It can represent a single figure, a man; the spirit directed upwards and the connection between the Heavens and the Earth. Vertical lines, with or without additions, indicate growth, perhaps trees.

Horizontal lines indicate the opposite of vertical ones. They symbolize the Earth, woman, passivity and rest, or even death; they are earthbound.

When horizontal and vertical lines intersect, a cross, one of the very oldest universal signs is created. The cross is a symbol for unification of the spiritual and the material – of life and death and of man and woman. It can also indicate the four points of the compass. The cross did not become a Christian symbol until after the crucifixion of Christ, since which time it has taken on many different variations.

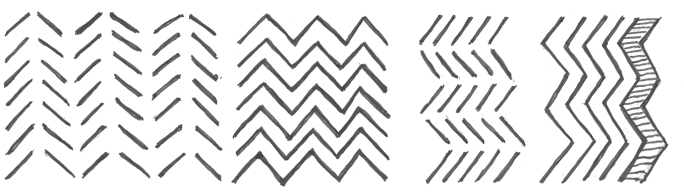

Lines joined in pairs diagonally (left and right) become chevrons that are found in many forms of pattern making from earliest times. When these diagonal lines are continuously joined, they form the zigzag, generally acknowledged to convey dynamism and energy.

Urban by Sue Reddish. This subtle piece demonstrates some of the possibilities for using a variety of textured and fine solid lines. Deeply interested in changes in the urban environment and the marks left upon it by humans, Sue builds up her imagery using her own techniques – a combination of painting and drawing on fabric, needle felting and hand stitching on a felted wool background. Straight stitches and seeding are worked in fine cotton and rayon threads.

Patterns made from zigzag lines are found across time in many early cultures. Sometimes combined with dots and other symbols, they represent a variety of natural phenomena such as mountains and the rhythm of change from night into day, for example. It can easily be seen how these marks could be realized in stitch, firstly in one thread, then in a variety of threads to change scale, density and emphasis to produce an array of different designs.

This sample explores linear stitched patterns in fine black threads on a white linen background. All the stitches are straight but spaced and angled differently, very gradually developing a range of related patterns. These could be starting points for work with colour and more changes of scale.

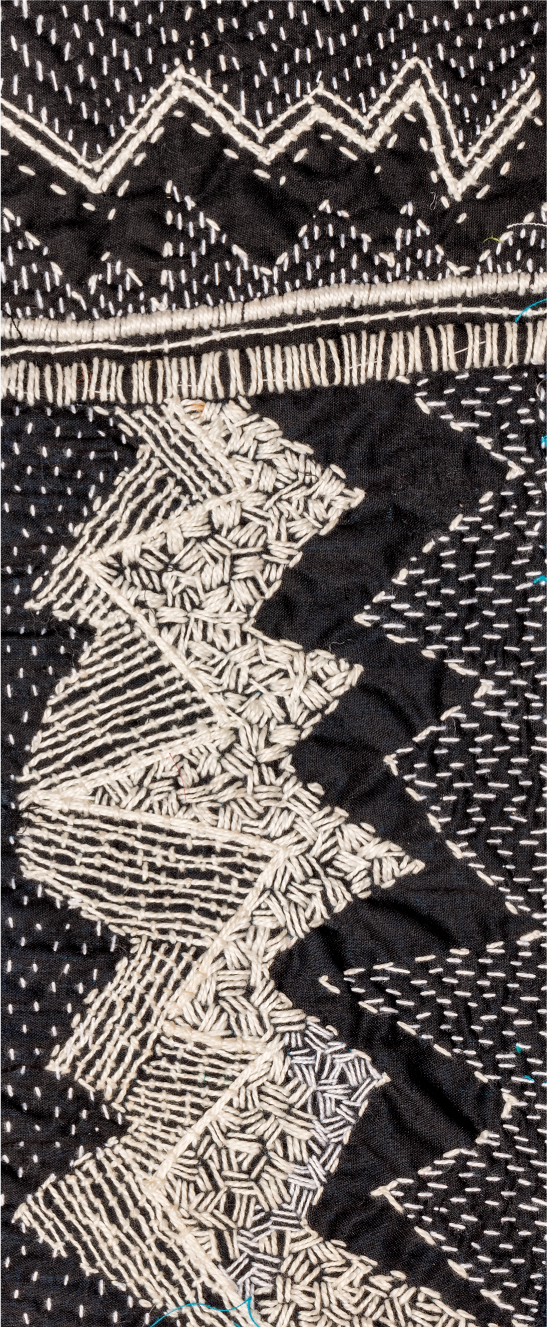

A simply stitched sample, with couching, running and straight stitches in various cotton threads, on a black cotton background. Different sizes and spacing of stitches create changes in density. The stark simplicity of the piece emphasises the dynamic quality of zigzag lines.

Opal by Michael Brennand-Wood, composed of layers of painted and fabric-wrapped wooden dowelling that is assembled and held together with long stitches in fine threads that pass through and around the layers. Some of these stitches are threaded with fragments of bright fabric. Always concerned with stitched textiles and pattern, much of Brennand-Wood’s work at this time has a base of layered wooden frameworks or grids representative of fabric weave structures. These are wrapped with complex repetitive stitches. The work illustrated above, and others like it, are reminiscent of disintegrating grids (or fabric). In common with all work by this artist, this piece demonstrates tremendous energy and movement in its dynamic lines.

Of all the many known symbols, three – sometimes called the primal symbols – have been found to be common throughout history to all peoples, regardless of religion, race or culture. These are the circle, the square and the triangle. They form the main structural framework (even when hidden) of many patterns throughout the ages. They are studied here in greater depth due to their early and continued importance in pattern-making. Using different interpretations, in a variety of stitched samples and resolved work in each category, the potential for pattern-making from the three primal symbols is illustrated on the following pages.

The circle, formed from one continuous line, has no beginning and no end. It is therefore the symbol of infinity, eternity, perfection and God. Regarded as an embracing symbol, the circle can also mean family and community, the Sun, the Earth and the planets.

Many variations exist, such as circles with centre points, circles divided both vertically and horizontally and circles representing wheels, all with particular meanings.

Closely related to circles is the spiral, which has been widely used across time by many cultures. It too represents eternity and can also be a symbol for the Sun. Developing from one point into adulthood, the spiral is found in nature in the shell of a snail, the centre of a sunflower and other growth forms. This ancient symbol has been brought forward in our consciousness in more recent years with the discovery of the structure of DNA, in the form of the double helix. The spiral has many variations and in some forms it is similar to labyrinth and maze patterns (see pages here).

Rhythmic hand embroidery largely composed of various couched spiral forms and curving lines. A variety of hand-made and commercial cords and threads were used on a silk background. Additional colour interest is obtained by contrasting the couching threads with the laid ones.

Delicate and small machine-embroidered dots are suspended on fine nylon fibre so that they cast shadows and appear to hover. Marian Bijlenga individually makes the rich little elements from very tiny fragments of fabric, dyed horsehair and stitching. Dozens of these are assembled to make large works.

A selection of experimental circular designs. A variety of mixed materials, such as nails, tin tacks, copper washers, thorns and large matt beads are worked over wrapped metal rings, or wire-wrapped horsehair intuitively joined with hand stitch. If wished, circular motifs like these could be joined together to form either regular or random repeating designs.

This sample was worked in white on a calico ground. Wrapped wire circles were couched to the background and the centres were then cut away. Fillings of smaller circles and stitched mesh were added. Finally, the whole piece was painted with terracotta clay slip and paint before rubbing with sandpaper to create a worn effect.

The spots or ‘eyes’ on butterfly wings were the starting point for this bold piece. Although all the circle motifs are different in colour and placement of stitches, the work has a regular repeating appearance. Each square was made separately from silk fibres needle felted onto cotton. Chain stitch, split stitch, couching and seeding stitches were used. The completed modules were mounted on a background of black felt. Groups of vintage millinery stamens in reference to a butterfly’s antennae, were stitched at the corners.

A series of large and small squares were made from brightly coloured cotton fabrics hand stitched with couching and straight stitches in richly coloured threads. This was an exercise in dividing the squares into different, but related, geometric patterns. Open squares made from wrapped wire were also made. This arrangement was chosen but many different ones could have been made. The piece was carefully assembled by hand stitching the corners. Note the negative shapes.

The square is the symbol of stability and substance. In Christian symbolism it represents the Earth (in contrast to Heaven). The four sides, all the same, represent the number four leading to the possibility that the square can symbolize the four seasons, the four points of the compass and the four elements – air, water, earth and fire.

Linear division of squares produce different figures with various meanings. A square placed on point (diamond-like), is generally regarded as more female, an ancient symbol of the power of creation. So a diamond within a square can represent woman protected by man.

Twelve open squares were made from thread-wrapped wire. They were divided into quarters with wrapped threads and then assembled diagonally in pairs joined at the points. Fine taught threads were stitched in pairs from sides to centre. The negative spaces are very important in this pattern.

Sample showing how rich geometric decoration on small squares could create an interesting mosaic-like patterned surface. Hand stitching creates a wealth of texture.

Fragmented Squares by Janis Firminger. This delicate abstract piece, based on reflected buildings in Venice, is a strong contrast to the square designs on the previous pages. It is worked in free-form machine embroidery with some hand-running stitches. Fine silks, metallic and coloured machine embroidery threads were used on a background of soft gold metallic tissue and chiffon.

As in some of the samples with squares shown on previous pages, wrapped wire was used to make lots of triangular modules in different sizes. Many joining possibilities were considered but the ones above (flat) and below (three dimensional) were chosen. When wall hung, interesting shadows are created.

The third of the primal symbols, the triangle, is an energetic sign because of its outwardly extended points. Balanced with one point downwards, the triangle is thought to appear more feminine whilst, on a flat base with one point directed upwards, it is thought to be characteristic of the male. With a dot in the centre, the triangle represents the all-seeing eye of God, and in Christian symbolism triangles represent the Trinity.

Triangles have been widely used throughout time and in many cultures, forming dynamic patterns when used alone or with other figures. They are easily formed from the negative spaces of a zigzag line and are frequently found together in pattern-making.

See an extended study of design using triangles at the end of Chapter 3 (see pages here).

Rags For Wishes, Threads for Prayers. Inspired by the symbolism attached to triangles, and to the symbolic hanging of threads and rags in India and some other countries, this piece embraces squares, triangles and circles – all the three primal shapes described in this chapter. Borders of shisha mirrors are used in different places, including on the background of waxed cotton fabric. The centre of the piece has a random pattern of gold-leaf triangles hung with coloured threads and fabric strips.

FURTHER WORK

• Look for contrasting lines in your surroundings. Record them.

• Try out stitches and different threads to translate the lines you see.

• Choose a symbol that appeals to you and see how many examples of it you can find around you. Record patterns you can make with your chosen symbol.

• Find and record information about other symbols. Many books are available.

• Look for examples of artwork featuring the symbols covered in this chapter. Study them and try to decide why they are interesting. Is there contrasting scale of shapes within the design? Are there arresting colours? Is there vitality? Record these and, using them as inspiration, develop your own designs.