Chapter Five

Empathic Resonance

Such empathy is made possible by the fact of the essential unity of human nature existing beneath, and in spite of all individual and group diversities.

—Roberto Assagioli

To the extent therapists die to their world, they realize a deep union with the client in Self, that is, they are “in altruistic love” or “in agape” with the client. The expression of this love in spiritual empathy then allows the therapist to function as an authentic unifying center, a “true link, a point of connection between the personal man and his higher Self” (Assagioli 2000, 22). To use a crude analogy, the therapist is rejuvenating a pipeline to the Source of the client's being, so naturally the client's being unfolds, blossoms, emerges. To put it another way, spiritual empathy “waters the seed” of the client's I-amness.

This empowerment of “I” in turn opens the possibility for clients' disidentification from chronic limiting patterns—this is their own dying—and a resultant openness to their inner experience, an expansion of their experiential range, and an increased potential for following their own unique meanings in therapy and in life.1 Held in love, the person can become less defensive, more open, and so all parts of the personality are freer to emerge, all experiences are increasingly able to arise. In other words, the emergence of I-amness increases clients' self-love and self-empathy, their ability to be engaged with, yet not be overwhelmed by, the various currents of their experience (see the section Held in Transcendent-Immanent Being in chapter 2).

THE EMPATHIC RELATIONSHIP

In a spiritually empathic relationship, then, each person is invited to an openness to the many diverse aspects of themselves. Again, an instructive example of this type of empathic intimacy is when you are spending time with a close, trusted friend. When you and your friend are together, you each are nondefensive and open to your arising experience, open to all the many diverse layers and “ages” of yourselves; in the relationship you both are free to express your joy and sorrow, hopes and fears, insights and idiosyncrasies, and what emerges between you is often surprising, creative, and life-giving.

So again note carefully that spiritual empathy does not necessarily imply that one's body language mirrors the other's body language, that one is feeling what the other is feeling, or that one is thinking what the other is thinking. Rather, the openness of this empathic relationship allows a mutual interplay and resonance between all the many different aspects, expressions, and levels of you both, whether these are similar or different.

EMPATHIC RESONANCE

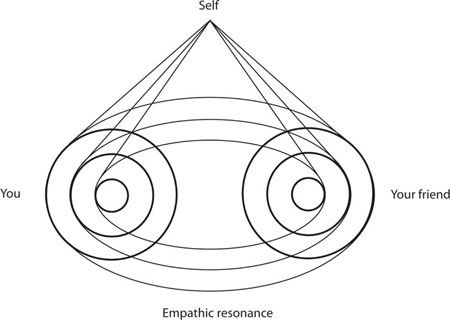

The possibilities of these many types of interactions and relational resonances within the empathic relationship are virtually infinite. The central dynamic is that the complex diversity of both parties is welcomed by the empathy flowing within the relationship, resulting in an extremely rich, creative interplay. This resonance among the many different aspects and levels of ourselves, or empathic resonance (Firman and Gila 1997; Firman and Russell 1994), is illustrated in Figure 5.1.2

Here we see represented the many psychological levels of one person—the “rings” from the developmental model in chapter 2—resonating with levels of the other person as both are held within the empathic field. All the while, Self, the ultimate source of the union between them, stands transcendent-immanent within the relationship.3

This mutual interplay is like a dance in which each is listening to the music of Self, responding to the same music in individual ways. Here there is a wholeness of the dance, a unity, and yet a unity that includes an intimate engagement of individualities. Such an empathic relationship is a dance of closeness and distance, of union and separation, of what can be called confluence and complementarity.4

CONFLUENCE AND COMPLEMENTARITY

This interplay or dance of the empathic relationship is confluent when, for example, your client expresses childlike hopes and fears and you feel these as well; there is a mutual mirroring of response, a confluence between you and the client. Here the worlds of therapist and client are as one, each individual expression or “dance” reflecting the other.

FIGURE 5.1

On the other hand, there may be a complementary resonance if the client's childlike hopes and fears trigger a parental soothing and caring response within you. Here you are not feeling what the client is feeling but rather empathically responding to what the client is feeling. Here the dance of both therapist and client appears quite different, yet each is responding to the same music—the client's sense of meaning and direction.

Furthermore, from the point of view of the oval diagram of the person (chapter 1), this interplay and resonance can include both the higher unconscious and the lower unconscious. As you and your client become open to the heights and depths of yourselves, these heights and depths will also resonate with each other. Here too these resonances might be confluent, as when your client's excited spiritual or creative insights stir your own or when your client's sudden childhood anxiety arouses your own; or complementary, as when your client's despair from early abuse triggers tenderness in you toward the client or anger toward the abusers. All of these responses can be expressions of spiritual empathy, arising from an attunement of “I” to “I” in Self.

PERSONAL BOUNDARIES

Engaging in empathic resonance can bring up the question of boundaries. “How far shall I let myself feel with the other?” “Am I merging?” “What distance should I keep?”

In spiritual empathy, the answers to all such questions need to be referred to the ultimate source of the loving empathic field, Self. Remember that we are essentially in union already. So, in a way, the boundary issue has already been resolved. Through our connection to the same Source in altruistic love, we are completely in union and at the same time our sense of individuality and personal volition arises from this very union.

So there is no a priori right or wrong answer about the degree of confluence or complementarity you should have with your client. You may be called to closeness, even a blending of reactions, or to objectivity, even distance. As you sit with your client, a dance will unfold as confluent and complementary responses come and go, as they wax and wane. One minute you can feel so at one with your client that you in effect lose yourself for a moment, becoming caught up in the client's experience—confluence. The next moment you may find yourself having feelings, thoughts, and insights in response to your client's experience—complementarity.

You may also find your own needs emerging, as when you want clarity about what is being said, or wish for some reflective silence, or need to attend to your own physical comfort. The boundaries between you and the other are fluid. There is no rigid, artificial, imposed way of being, but rather a trusting openness to the spontaneous dance of the relationship.

So boundaries are a function of your relationship to Self, to your sense of trust and love in the relationship, your sense of how you are called to be in the moment. You may be called to listen and “hold space,” or share a reflection, or report your confusion, or offer a technique, or provide information. It all depends on where you are invited by the love and truth of the relationship.

EXPLORING THE RELATIONAL EXPERIENTIAL RANGE

As therapists we can ask ourselves, however, if we are able to move freely throughout the range of experiences we are invited to in empathic relationships—from confluence to complementarity. First of all, do I feel comfortable “dying to self” such that I turn over my moment-to-moment position on this range to my deepest sense of truth, to Self? Remember, agape is a selfless, nonpossessive, unconditional love. Can I trust to surrender to this or are there fears about losing control, feeling awkward, or facing the unknown, for example? I may here need to work with my own therapist on a pattern of compulsive control, or defensive attachment to a rigid professionalism, or overdependence on protocol and technique. Any such psychological work will go a long way in helping us, as therapists, with the “boundary issue.”

Then one might explore the range from confluence to complementary encountered in intimate personal relationships. Do I feel comfortable in a close confluence or does it bring up fears of losing myself, for example? Contrariwise, am I comfortable acting from my own perspective or does it bring up early fears of conflict and rejection? Exploring patterns around confluence and complementarity—discovering habitual beliefs, chronic attitudes, and early wounding around each—can free up our ability to respond to the changing dynamics of the empathic relationship. This is another creative response to the “boundary issue.”

But again, the boundary issue has been resolved at the most essential level, the Ground of Being, Self. At that level we are completely at one, non-dual, in agape, and at the same time our sense of personal integrity and efficacy arises directly from this deep union of love. This is, remember, one of the core principles in any psychology of love: personal selfhood is not at risk in the union of altruistic love but arises from, and is sustained by, that union.

EMERGING PRIMAL WOUNDING

In empathic resonance then, there is a rapport, a simpatico feeling, an attunement—a love—between therapist and client at many levels of depth. But since inner layers of the personality contain primal wounding from earlier nonempathic environments, it should be no surprise at all that empathic resonance, as close and intimate as this is, will also surface wounding from the past that exists, hidden and active, in the present.5 While this emergence of wounding represents an opportunity for healing and growth, it may be surprising and challenging to all concerned:

The client began by saying that his life was a disaster. He was going to get fired from his job and he'd broken up with his girlfriend. In anguish, he said that he'd never, ever, felt this awful in his whole life, and what was he to do?

As he looked up at me, I felt put on the spot and asked hastily, “How do you feel about all this?” He quickly answered with a lot of anger, “How the f**k do you think I feel about it? I f**king feel awful! Haven't you been listening to me?!” I was hurt and irritated by his response—all I was doing was asking him how he felt, right? Wasn't that being with him?

But I knew I hadn't met him and needed to get back to him. I said I was sorry, that for a moment I had been flustered by all that had happened to him. I told him that I did want to be present with him, and that I was here to go where he wanted to go. He thanked me for hearing him and said he wanted to explore his angry reaction to my question. Thank God our therapeutic alliance held up.

As he explored his anger he became aware of an underlying feeling of being overwhelmed. When he explored this, he uncovered an aspect of his relationship with his mother in which he felt abandoned to overwhelming events—exactly what he had experienced in my first reaction to him!

Later, in my supervision, I realized that as my client began talking about these upsetting events, I had become anxious. We discussed “projective identification” of course, but for me to be able to resonate so strongly to this issue also meant I had my own issue in me. I had felt unconsciously that I had to help him somehow and at the same time I doubted my ability to do this. I was afraid I would fail. In my own therapy, I later traced these feelings to my fear of disappointing my father and him seeing me as a failure.

So my intervention, “How do you feel about all this?” wasn't actually about him at all. It was about me. My “innocent” and “therapeutic” intervention was really something like, “Oh my God, what am I going to do now? Quick say something—anything that will show you can handle this!”

Deep down—at a level the client was tuned into beyond my ability to do so myself—I was avoiding feelings of inadequacy and failure, desperately wanting to be a winner in my father's eyes! The client was absolutely right—I wasn't listening to him. I was abandoning him in an overwhelming situation, just like his mother had. I felt bad about this, but I was way, way more glad to see what had happened.6

In this interaction, the therapist ultimately sustained her empathic resonance with the client, maintaining awareness of this connection rather than being sidetracked by her own reactions. Through the maintenance of this I-Thou union, the love and trust allowed both parties to address the emerging wound in the client's experience. One could not have planned such a session. The truth that emerged simply came forth as the empathic relationship was maintained and the “dance” unfolded.

Note well the task of the therapist revealed in this brief vignette. Her challenge was to maintain her knowing of the empathic connection even though the empathic resonance was energizing her own uncomfortable feelings of anxiety, self-doubt, and fear of failure. Some neurobiological writers put it this way: “A therapist loosens his grip on his own world and drifts, eyes open, into whatever relationship the patient has in mind—even a connection so dark that it touches the worst in him” (Lewis, Amini, and Lannon 2001, 178).

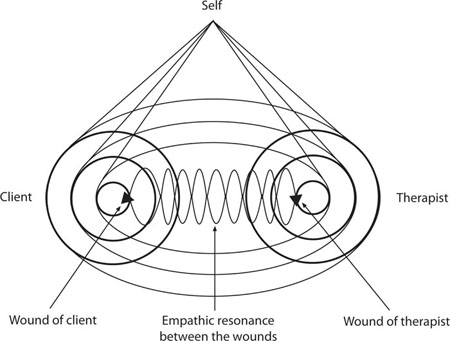

This therapist's anxiety, self-doubt, and fear were her own wounds in a confluent resonance to the client's wounds within the empathic field.7 This traumatic resonance (Firman and Gila 1997) or traumatic countertransference (Herman 1992) is diagrammed in Figure 5.2.

This figure shows the client's wound—being abandoned by his mother to overwhelming events—resonating with the therapist's wound—the self-doubt, inadequacy, and fear of failure from her own childhood. Initially, in order to escape her own difficult feelings, the therapist made her hasty intervention and so caused the empathic break. The function of an empathic failure at this point is quite clear—it disrupts the traumatic resonance and so relieves the therapist's feelings.

FIGURE 5.2

As the therapist said, her intervention was basically an attempt to avoid feeling her own wounding. In effect she was saying, “I better be with you in this so you will know I am present and I won't feel fearful, inadequate, and a failure!” In other words, the client here became an “It” rather than a “Thou”—he became a “thing” by which she was going to make herself feel better. Thus the empathic connection was broken, the client felt the break, and so the client reacted.

THE PSYCHOLOGY OF THE EXTERNAL

Note that this case is not simply a “projection” or “transference” of the client's issue with his mother onto the “blank screen” of the therapist, even though the wounding from his mother was central in the interaction. Making such an interpretation at this point would constitute still another empathic failure because it would miss the valid response of the client to actual impingements in the present.

Rather, the empathic approach to such a triggered situation is founded in two understandings: (1) a wound has been impinged upon in the here-and-now by actual empathic failure, however insignificant this failure may seem, and (2) the wound itself was most likely caused by an event in the past. If there is enough trust and goodwill in the relationship, these two understandings can allow client and therapist to process the here-and-now empathic failure and engage the triggered wound directly. In the example, the client and therapist moved quickly through the empathic failure, carried by the trusting relationship they had developed over time, and so were able to move fairly quickly to the vulnerable wounding.

If the client had wished to know more about the nature of the therapist's “flustered” response, the therapist would have taken time to look within herself to discover what was happening for her. This would not involve actual psychological work on the therapist's reactions in the moment, but a simple brief looking and sharing what she saw, if anything. If the reaction was largely unconscious, there may have been little to report but at least the therapist can hypothesize that there must be something there. This sharing by the therapist would be part of acknowledging the disruption in the empathic field and thereby remaining empathic with the client.

So in psychosynthesis therapy we do not assume that clients' negative reactions derive simply from their own private internal dynamics, but that these are meaningful responses to violations by the external world, past and present. To borrow psychiatrist and abuse expert Lenore Terr's (1990) descriptive term, this focus on the external world can be called “the psychology of the external,” a complement to the more traditional “psychology of the internal.” That is, while therapists are dealing with wounds internal to the client, these wounds—and their subsequent triggering—are the results of actual impingements by the external world. Without a psychology that embraces both the internal and external, wounding will remain hidden and unhealed.8

The psychology of the external can be extended to mean that the client's responses to the larger world, both negative and positive, are taken seriously within the therapy. For instance, to be upset by a spouse's behavior or by the ecological crisis, to be excited by a developing world event or enraged by pervasive societal bigotry, or to be enchanted by the birds singing outside, are not to be considered merely a reflection of the client's own issues. Assagioli was clear that individual psychosynthesis included responsiveness to the wider environment:

In its turn this brings up the many problems and psychosynthetic tasks of interpersonal relationships and of social integration (psychosynthesis of man and woman—of the individual with various groups—of groups with groups—of nations—of the whole of humanity). (Assagioli 2000, 6)

While it may be true that the intensity of response to such external happenings is a function of the client's inner world, the responses cannot be reduced to that world. Just as with the client's reaction to the therapist's empathic failure in the earlier example, concerns about the external world need to be held within the therapy as valid in their own right. Indeed, clients may in such instances be discerning a call to act in relationship to larger interpersonal, societal, and global issues in the living of their lives (see chapters 10 and 11). The psychology of the external thus helps bridge that much-criticized gap between psychotherapeutic insight and action in the world.9

TRIGGERED BY THE POSITIVE

Oddly enough, it is not only painful experiences that can trigger hidden wounds in the therapist. Experiences involving energies such as joy, love, wonder, or bliss—transpersonal qualities or Maslow's “being cognitions” (see chapter 1)—can also push therapists toward their wounding. For example, a therapist may react nonempathically to a client excited about a prospective new lover, a client speaking in wonder about a religious awakening, or a client who warmly expresses appreciation and gratitude for the therapist.

Why would a therapist react negatively here? Because her client's love relationship reminds her of the devastation she herself experienced when she lost her first love, a time that in turn echoed the earlier loss of her father through emotional abandonment. Another therapist might be uneasy with a religious awakening, since it reminds him of his childhood in which his parents used religion and the idea of God to control him. Still another therapist might reject her client's appreciation and gratitude, unconsciously feeling these clashing with her own hidden negative image of herself from childhood.

If we act out from these wounds, we will tend to discount, downplay, or even denigrate such positivity coming from our clients. We may be led to say, for example, “Remember this is the honeymoon stage of the relationship,” or “Are you worried about getting carried away with religion?” or “Thanks for your gratitude, but I can't take any of the credit—you did it all.” At the least we will simply give our clients a cool, quiet reception when they report these positive experiences—anything that will stem their excitement, dampen their enthusiasm, temper their wonder.

We therapists can of course rationalize all our nonempathic reactions as proper therapeutic protocol: we are simply confronting clients' illusions, playing the stern “reality principle” (Freud 1968, 365) to the regressive childish fantasies and infatuations dominated by the “pleasure principle” (Freud 1968, 365). And, after all, it is our duty to represent reality to the client, right? But looking more closely, we will see that our reactions are in fact ways of breaking the empathic connection and avoiding the client's world. Why? Because in this way we protect ourselves from experiencing the hidden wounding that is resonating within the empathic field.10

If we remain unconscious of these emerging wounds, we will be unable to facilitate an integration of the transpersonal qualities embedded in these types of experiences. As discussed earlier, clients will then be placed in the position of developing a survival personality with which to endure therapy, or of resisting therapy, or finally of ending the therapy. It again becomes quite clear why we as therapists need to die to our world in order that we can love our clients in their worlds.