The Economic Goals of Schooling

Human Capital, Global Economy, and Preschool

Today, economic goals are the primary influence on public school policies, curricula, and standardized testing. As mentioned at the beginning of Chapter 1, a current goal of schooling is educating students to compete in a global labor market. By educating students for work in the global economy, politicians and policy leaders claim it will result in economic growth and help the United States compete in the global economy. In 2008, the Partnership for 21st Century Skills issued a report with a title indicating economic education goals: 21st Century Skills, Education and Competitiveness. The report declared, “Creating an aligned, 21st century public education system that prepares students, workers and citizens to triumph in the global skills race is the central economic competitiveness issue for the next decade.”

Current global economic goals are based on what economists call human capital theory, which assumes that money spent on education will lead to economic growth, reduce poverty, and improve personal incomes. Human capital arguments are currently providing a justification for the expansion and funding of preschool education from zero to four years of age to improve their chances for employment.

For example, the link between human capital theory, the global economy, and preschool was highlighted in a speech by Montana Governor Brian Schweitzer at a three-day Partnership for America’s Economic Success Economic Summit on Early Childhood Investment held in September 2007. He told the gathering of education leaders, politicians, and business groups: “We’re no longer competing just with Colorado; we’re competing with China. We need to challenge every single educator to create the next engineer.” Reporting on the conference for Education Week, Linda Jacobson gave her article the descriptive human capital title: “Summit Links Preschool to Economic Success.” She reported,

Hoping to win over skeptical policymakers, leaders from the business, philanthropic, and political arenas gathered here this week to strengthen their message that spending money on early-childhood education will improve high school graduation rates and help keep the United States economically strong.

In summary, this chapter discusses the following:

- Human capital theory as related to the role of education in:

- growing the economy;

- reducing poverty;

- raising personal income.

- Education for the global economy.

- School curriculum and the global economy.

- Criticisms of human capital theory:

- Can investment in schools grow the economy?

- Does increased school attendance reduce the value of academic diplomas?

- Preschool education:

- human capital theory and the education of 0- to 4-year-olds;

- preschool education and the teaching of social skills.

- Child-rearing and social and cultural capital.

- Family learning and school success.

The idea of educating for economic growth and competition is not new. Since the nineteenth century, politicians and school leaders have justified schools as necessary for economic development. Originally, Horace Mann proposed two major economic objectives. One was what we now call human capital. Simply stated, human capital theory contends that investment in education will improve the quality of workers and, consequently, increase the wealth of the community.

Mann, often called the father of American schools, used human capital theory to justify community support of schools. For instance, why should an adult with no children be forced to pay for the schooling of other people’s children? Mann’s answer was that public schooling increased the wealth of the community and, therefore, even people without children benefited economically from schools. Mann also believed that schooling would eliminate poverty by raising the wealth of the community and by preparing everyone to be economically successful. The current concept of human capital and the knowledge economy can be traced to the work of economists Theodore Shultz and Gary Becker. In 1961, Theodore Schultz pointed out that “economists have long known that people are an important part of the wealth of nations.” Shultz argued that people invested in themselves through education to improve their job opportunities. In a similar fashion, nations could invest in schools as a stimulus for economic growth.

In his 1964 book Human Capital, Becker asserts that economic growth depends on the knowledge, information, ideas, skills, and health of the workforce. Investments in education, he argued, could improve human capital which would contribute to economic growth. Later, he used the phrase knowledge economy: “An economy like that of the United States is called a capitalist economy, but the more accurate term is human capital or knowledge capital economy.” Becker claimed that human capital represented three-quarters of the wealth of the United States and that investment in education would be the key to further economic growth. Following a similar line of reasoning, Daniel Bell in 1973 coined the term “post-industrial” and predicted that there would be a shift from blue-collar to white-collar labor requiring a major increase in educated workers. This notion received support in the 1990s from Peter Drucker, who asserted that knowledge rather than ownership of capital generates new wealth and that power was shifting from owners and managers of capital to know ledge workers. During the same decade, Robert Reich claimed that inequality between people and nations was a result of differences in knowledge and skills. Invest in education, he urged, to reduce these inequal ities. Growing income inequality between individuals and nations, according to Reich, was a result of differences in knowledge and skills.

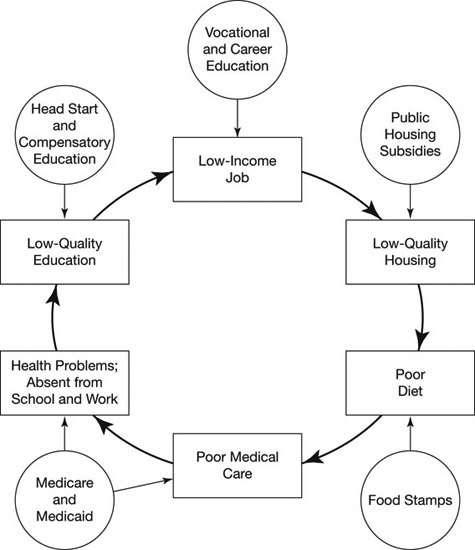

It was human capital theory that provided arguments to support expanding preschool education and previously the 1960s War on Poverty which resulted in Head Start, the television program Sesame Street, and compensatory school programs to eliminate poverty. Based on human capital theory, the economic model of the War on Poverty shown in Figure 4.1 exemplifies current and past ideas about schooling and poverty. Notice that poor-quality education is one element in a series of social factors that tends to reinforce other social conditions. Moving around the inner part of the diagram, an inadequate education is linked to low-income jobs, low-quality housing, poor diet, poor medical care, health problems, and high rates of absenteeism from school and work. This model suggests eliminating poverty by improving any of the interrelated points. For instance, the improvement of health conditions will mean fewer days lost from school and employment, which will mean more income. Higher wages will mean improved housing, medical care, diet, and education. These improved conditions will mean better jobs for those of the next generation. Anti-poverty programs include Head Start, compensatory education, vocation and career education, public housing, housing subsidies, food stamps, and medical care.

Today, preschools for low-income families and Head Start programs are premised on the idea that some children from low-income families begin school at a disadvantage in comparison to children from middle-and high-income families. Head Start programs provide early childhood education to give poor children a head start on schooling that allows them to compete on equal terms with other children. Job-training programs are designed to end teenage and adult unemployment. Compensatory education in fields such as reading is designed to ensure the success of low-income students.

Besides the issue of poverty, human capital arguments directly influenced the organization of schools. In the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, the dominant model for linking schools to the labor market is the sorting machine, as I discussed in Chapter 3. The image of the sorting machine is that of pouring students – called human capital or human resources – into schools where they are separated out by abilities and interests. Emerging from the other end of the machine, school graduates enter jobs that match their educational programs. In this model, the school counselor or other school official uses a variety of standardized tests to place the student into an ability group in an elementary school classroom and later in high school into a course of study. Ideally, a student’s education will lead directly to college or to a vocation. In this model, there should be a correlation among students’ education, abilities, and interests and their occupations. With schools as sorting machines, proponents argue, the economy will prosper and workers will be happy because their jobs will match their interests and education.

In the twenty-first century, American workers are competing in a global knowledge economy. As U.S. companies seek cheaper labor in foreign countries, American workers are forced to take reductions in benefits and wages to compete with foreign workers. The only hope, it is argued, is to train workers for jobs that pay higher wages in the global labor market. Preparation for the global economy shifts the focus from service to a national economy to a global economy by preparing workers for international corporations and for competition in a world labor market. American workers’ income will supposedly rise because they will be educated for the highest-paying jobs in the world knowledge economy.

The global knowledge economy is linked to new forms of communication and networking. Referring to the new economy of the late twentieth century, Manuel Castells states in The Rise of the Network Society: “I call it informational, global, and networked to identify its fundamental distinctive features and to emphasize their intertwining.” By informational, he meant the ability of corporations and governments to “generate, process, and apply efficiently knowledge-based information.” It was global because capital, labor, raw materials, management, consumption, and markets were linked through global networks. “It is networked,” he contended, because “productivity is generated through and competition is played out in a global network of interaction between business networks.” Information or knowledge, he claimed, was now a product that increased productivity.

The human capital and knowledge economy argument became a national issue in 1983 when the federal government’s report A Nation at Risk blamed the allegedly poor academic quality of American public schools for causing lower rates of economic productivity than those of Japan and West Germany. In addition, it blamed schools for reducing the lead of the United States in technological development. The report states, “If only to keep and improve on the slim competitive edge we still retain in world markets, we must rededicate ourselves to the reform of the educational system for the benefit of all.” Not only was this argument almost impossible to prove but some have claimed it was based on false data and assumptions, as captured in the title of David Berliner and Bruce Biddle’s The Manufactured Crisis: Myths, Fraud and the Attack on America’s Public Schools.

In the 1990s, President Bill Clinton used the rhetoric of human capital and the knowledge economy. When Clinton ran for the presidency in 1992, the Democratic platform declared: “A competitive American economy requires the global market’s best educated, best trained, most flexible work force.” Education and the global economy continued as a theme in President Clinton’s 1996 re-election:

Today’s Democratic Party knows that education is the key to opportunity. In the new global economy, it is more important than ever before. Today, education is the fault line that separates those who will prosper from those who cannot.

The architect of educational policies for the global economy, former Labor Secretary Robert Reich, writes in The Work of Nations, “Herein lies the new logic of economic capitalism: The skills of a nation’s workforce and the quality of its infrastructure are what make it unique, and uniquely attractive, in the world economy.” Reich draws a direct relationship between the type of education provided by schools and the placement of the worker in the labor market. He believes that many workers will be trapped in low-paying jobs unless their employment skills are improved. Reich argues, “There should not be a barrier between education and work. We’re talking about a new economy in which lifelong learning is a necessity for every single member of the American workforce.”

Human capital and global competitiveness are used to justify No Child Left Behind, the most important federal legislation of the twenty-first century. The opening line to the official U.S. Department of Education’s A Guide to Education and No Child Left Behind declares, “Satisfying the demand for highly skilled workers is the key to maintaining competitiveness and prosperity in the global economy.” In his 2006 State of the Union Address, President George W. Bush declared,

Keeping America competitive requires us to open more markets for all that Americans make and grow. One out of every five factory jobs in America is related to global trade … we need to encourage children to take more math and science, and to make sure those courses are rigorous enough to compete with other nations.

The 2012 Democratic Party platform’s education agenda emphasized global economic goals:

An Economy that Out-Educates the World and Offers Greater Access to Higher Education and Technical Training.

Democrats believe that getting an education is the surest path to the middle class, giving all students the opportunity to fulfill their dreams and contribute to our economy and democracy. … We are committed to ensuring that every child in America has access to a world-class public education so we can out-educate the world and make sure America has the world’s highest proportion of college graduates by 2020 [emphasis in original].

Human capital arguments contain an educational agenda of standardization of the curriculum; accountability of students and school staff based on standardized test scores; and the deskilling of the teaching profession. What is meant by deskilling is that in some cases teaching involves following a scripted lesson created by some outside agency or when teachers are forced to teach to the requirements of standardized tests. The deskilling of teaching includes the disappearance of teacher-made tests and lesson plans and the ability of teachers to select the classroom’s instructional methodology.

The following is the list of features of the human capital education paradigm:

- The value of education measured by economic growth.

- National standardization of the curriculum.

- Standardized testing for promotion, entrance, and exiting from different levels of schooling.

- Performance evaluation of teaching based on standardized testing of students.

- Mandated textbooks.

- Scripted lessons.

- Lifelong learning.

In recent years, there has been discussion of the school’s role in promoting a learning society and lifelong learning so that workers can adapt to constantly changing needs in the labor force. A learning society and lifelong learning are considered essential parts of global educational systems. Both concepts assume a world of constant technological change, which will require workers to continually update their skills. This assumption means that schools will be required to teach students how to learn so that they can continue learning throughout their lives. These two concepts are defined as follows:

- In a learning society, educational credentials determine income and status. Also, all members in a learning society are engaged in learning to adapt to constant changes in technology and work requirements.

- Lifelong learning refers to workers engaging in continual training to meet the changing technological requirements of the workplace.

In the context of education for the global economy, the larger questions include the following:

- Should the primary goal of education be human capital development?

- Should the worth of educational institutions be measured by their contribution to economic growth?

- Will a learning society and lifelong learning to prepare students for technological change increase human happiness?

There are criticisms regarding human capital theory and the ability of schools to educate students for occupations in the global economy and end economic inequality. What happens if there are not enough jobs in the knowledge economy to absorb school graduates into skilled jobs or that the anticipated demand for knowledge workers has not occurred? One result may be the declining economic value of high school and college diplomas or what is called “educational inflation.” Are employers, who in the past would hire a high school graduate for a job, now seeking college graduates for the same job because of an overabundance of college graduates?

An important effect of the labor market on the value of academic diplomas is the routinization of so-called knowledge work that allows for the hiring of less-skilled workers. “It is, therefore,” Phillip Brown and Hugh Lauder conclude, “not just a matter of the oversupply of skills that threatens the equation between high skills and high income, where knowledge is ‘routinized’ it can be substituted with less-skilled and cheaper workers at home or further afield.”

Brown and Lauder argue that multinational corporations are able to keep salaries low by encouraging nations to invest in schools that prepare for the knowledge economy. An oversupply of educated workers depresses wages to the advantage of employers. This could be occurring in the United States, as suggested by Brown and Lauder, through a combination of immigration of educated workers from other countries and the increased emphasis on college education for the workforce. In fact, Brown and Lauder argue that there has been no real increase in income for college graduates since the 1970s except for those entering “high-earner” occupations. However, college graduates still earn more than non-college graduates.

Economist Andrew Hacker criticizes the very foundation of human capital arguments. Human capital economists premise their arguments on the fact that growth in school attendance parallels the growth of the economy, but it is a big leap from this fact to say that increased education causes economic growth. Hacker flips the causal relationship around and argues that economic growth provides the financial resources to fund educational expansion and offer youth an entertaining interlude in life. Hacker notes that much of the original funding of higher education came from innovative industrialists who were not college graduates. Today, college dropouts lead the list of innovative developers, such as Larry Ellison (Oracle), Bill Gates (Microsoft), Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak (Apple), and Michael Dell (Dell).

Hacker’s argument does not mean that schooling is not important for jobs. However, human capitalists may have oversold their argument about education causing economic growth and being necessary for global competition. First, the state of the global economy and jobs is uncertain and constantly changing. Second, there may be an over-education of the population causing educational inflation. Inflation refers to employers increasing the educational requirements of jobs when there is an overabundance of graduates. In this situation, the economic value of a high school or college degree declines when there is an overabundance of well-schooled workers.

Are jobs really tied to getting more schooling? Not according to economist Andrew Hacker. In a review of The Race Between Education and Technology by Claudia Goldin and Lawrence Katz, Hacker questions the argument that more schooling, particularly more higher education, is necessary for employment in today’s job markets.

Hacker’s question is legitimate when one examines the 2012 US Bureau of Labor Statistics report, which found “The most new jobs from 2012 to 2022 are projected to be in occupations that typically can be entered with a high school diploma.” Also, the statistics revealed that there would be more jobs for those with less than a high school diploma than for those with Bachelor’s degrees. The job projections show that the number of occupations requiring a high school diploma or its equivalent will grow by 4,630,800 and those occupations requiring less than a high school diploma will increase by 4,158,400. In contrast, the job projections for those with Bachelor’s degrees will increase by 3,143,600, while those for occupations requiring a doctoral or professional degree will grow by 638,400, Master’s degree by 448,500, associate’s degree by 1,046,000, and some college, no degree by 225,000.

In practice some business enterprises disregard the quality of workers’ schooling when they train employees at the workplace. Consider the decision by foreign auto manufacturers to locate in states with low wages and no unions but with high dropout rates: Nissan, Coffee County, Tennessee, 26.3 percent school dropout rate; BMW, Spartanburg County, South Carolina, 26.9 percent school dropout rate; Honda, St. Clair County, Alabama, 28.7 percent school dropout rate; and Toyota, Union County, Mississippi, 31.5 percent school dropout rate. Hacker argues that these companies didn’t care about local school quality because worker training was on the job. Based on these arguments, more schooling may not result in higher paying jobs or economic growth.

There are also questions about investing in education to reduce income inequality. From the 1970s to the present US income inequality has increased so that inequality, according to one report, was greater in 2010 than it had been in 1913. The Pew Research Center claimed, “U.S. income inequality has been increasing steadily since the 1970s, and now has reached levels not seen since 1928.” Economist like Theodore Schulz argued that “changes in the investment in human capital are a basic factor reducing the inequality in the personal distribution of income.” Schultz’s argument appears wrong when it is compared to the reality of increasing differences in income.

A recent argument for expanding preschool is that it can teach the “soft” skills needed by global employers. Human capital theorists make a distinction between soft and hard skills needed for work. Hard skills refer to such things as literacy instruction and numeracy along with specific job skills, and soft skills refer to character traits that will help the worker succeed in the workplace.

Adecco, an employment management firm with 6,600 global offices, reports that employers list soft skills as being more important than hard skills. In their 2013 report “The Skills Gap and the State of the Economy,” surveyed senior executives (44%) claimed that soft skills were the major skills gap in finding workers as compared to technical skills (22%), leadership skills (14%), and computer skills (12%). For soft skills, Adecco listed “communication, critical thinking, creativity and collaboration.”

Preschool has been a concern of educators since the nineteenth century. Originally it was mainly focused on the hard and soft skills which students brought to school and how it effected school achievement. Nineteenth-century common-school advocates worried that children entered school with different social experiences and knowledge – a situation that members of the New York Workingman’s Party wanted to correct by placing children in state residential institutions. Today, the focus is on preschool education to provide all children with similar access to social experiences and knowledge as preparation for schooling and employment. The most well known of the federal preschool programs are Early Head Start and Head Start – which, as indicated by their names, are designed to give children from low-income families a head start in schooling so that they reach the same level of educational achievement as children from high-income families.

In the twenty-first century, human capital economists argue that preschool education is the most efficient way for the government to invest its money to support economic growth by providing young children with the hard and soft skills needed for success in primary school and later in employment. Investing in preschool education to reduce poverty is recommended by Nobel economist James J. Heckman. Heckman’s major concern is the soft skills learning in preschool. His recommendation is based on research studies regarding the Perry Preschool. Before considering the results of research on the Perry Preschool, I will discuss the current approach of human capitalist economists like Heckman as compared to the early human capital economists like Gary Becker.

When Gary Becker did his work in the 1960s, he primarily thought of investment in human capital as involving knowledge, information, ideas, skills, and the health of the workforce. One distinction between Becker and Heckman is the focus on early investments in human capital that enhance the development of later skills and employability; namely preschool education. In their 2005 book Inequality in America: What Role for Human Capital Policies?, Pedro Carneiro and James J. Heckman assert: “This dynamic complementarity in human investment was ignored in the early work on human capital. Learning beget learning, skills (both cognitive and noncognitive) acquired early on facilitate later learning.”

Today, human capital economists like Heckman focus on soft skills, such as motivation, self-discipline, stability, dependability, perseverance, self-esteem, optimism, future orientation, and other soft skills that affect learning and job performance. Many researchers argue that there is a strong relationship between family background and academic success. Economists like Heckman now argue that family background provides the non-cognitive skills needed for school and job achievement. Families “fail” when these non-cognitive skills are not taught to their children.

Carneiro and Heckman stress the importance of non-cognitive abilities: “Noncognitive abilities [soft skills] matter for success both in the labor market and in schooling.” In fact, they argue, the success of people with high cognitive abilities is dependent on their non-cognitive abilities. Simply stated, a smart person without motivation, perseverance, dependability, trustworthiness, and self-esteem may not do well in school or in the labor market. On the other hand, a person with low cognitive abilities but high non-cognitive abilities might succeed at school and work. Carneiro and Heckman assert, “Numerous instances can be cited of high-IQ people who fail to achieve success in life because they lack self-discipline and low-IQ people who succeed by virtue of persistence, reliability, and self-discipline.”

If non-cognitive abilities are important for future school and work success, and early learning of skills helps in gaining future skills, then, according to Heckman, money spent on preschool education provides a greater economic rate of return than increased spending on primary, secondary, and higher education or on job training. This is Heckman’s major conclusion.

For instance, consider the investment in financial aid for college. Family income is related to college attendance and completion. But is it the major factor? The answer according to Heckman is no. Admittedly, the wealthy have an easier time paying for higher education than the poor. However, college readiness and success in college are dependent on non-cognitive abilities like motivation, self-discipline, stability, dependability, perseverance, and self-esteem. Without these attributes both the rich and poor student will fail. Heckman argues that enough funding sources are available for students from low-income families who are college ready and have the right non-cognitive abilities to complete their college educations.

What about increasing spending per public school student and reducing class size? Carneiro and Heckman conclude that “the United States may be spending too much on students given the current organization of educational production.” Spending too much? Also, they argue that spending more money on schools and lowering class sizes will not improve American education. The same arguments are made regarding investment in job training and high school intervention programs. In the end, the success in work and high school depends on non-cognitive abilities learned at an early age.

What about reducing the racial and ethnic gaps in school achievement? “A major conclusion,” Carneiro and Heckman state,

is that the ability that is decisive in producing schooling differentials is shaped early in life. If we are to substantially eliminate ethnic and income differentials in schooling, we must start early. We cannot rely on tuition policy applied in the child’s adolescent years, job training, or GED programs to compensate for the neglect the child experienced in the early years.

The Perry Preschool study is often cited as proof of the value of preschool in fostering soft skills for success in school and employment. After reviewing a Perry Preschool report, Heckman concluded,

This report substantially bolsters the case for early interventions in disadvantaged populations. More than 35 years after they received an enriched preschool program, the Perry Preschool participants achieve much greater success in social and economic life than their counterparts who are randomly denied treatment.

Beginning in 1962, the Perry Preschool study began with 123 African American children from low-income families who were considered at risk for school failure. They had low IQs (this measure is later rejected and not used in subsequent studies) and were borderline mentally impaired with no organic deficiencies that might cause impairment. During the first phase, from 1962 to 1967, the children attended what was considered a high-quality early childhood education program with teachers visiting their homes. Children attended the preschool for 2.5 hours per day Monday through Friday for a two-year period with a staff ratio of one adult for every five or six children. The staff did home visits for 1.5 hours each week. During this first phase the principal concern was improving the cognitive abilities of the children. In 1970, the research became the principal project of the High/Scope Foundation which today claims “is perhaps best known for its research on the lasting effects of preschool education and its preschool curriculum approach.”

A longitudinal follow-up tracked students through the third grade or age 8 for intellectual development, school achievement, and “social maturity.” Another study included the children and families in the cohort group from ages 8 to 15 with an emphasis on intellectual development, school achievement, and family attitudes. Participants were studied after leaving school until age 19 with the research described as follows:

Instead of an intelligence or traditional achievement test, study participants took a test of functional competence that focused on information and skills used in the real world. Other measures focused on social behavior in the community at large, job training, college attendance, pregnancy rates, and patterns of crime. For the first time, the cost–benefit analysis is based on actual data from complete school records, police reports, and state records of welfare payments. … While projections of lifetime earnings are still necessary, the basic patterns of the subjects’ adult lives are beginning to unfold [emphasis in original].

As indicated in Table 4.1, researchers found that those attending Perry Preschool as compared to those who didn’t attend who were from a similar economic and social background were less likely to commit crimes and, if female, become pregnant. They were also more likely to be employed, graduate from high school, and attend college or receive vocational training. In addition, Perry Preschool graduates were less likely to be placed in special education. Regarding cost–benefit analysis, the researchers concluded,

These benefits considered in terms of their economic value make the preschool program a worthwhile investment for society. Over the lifetimes of the participants, preschool is estimated to yield economic benefits with an estimated present value that is over seven times the cost of one year of the program.

Table 4.1 Report Findings at Age 19 of the Perry School Cohort Group

| Category |

Number Responding |

Preschool Group (%) |

No Preschool Group (%) |

| Employed |

121 |

59 |

32 |

| High school graduation (or its equivalent) |

121 |

67 |

49 |

| College or vocational training |

121 |

38 |

21 |

| Ever detained or arrested |

121 |

31 |

51 |

| Females only: teen pregnancies, per 100 |

49 |

64 |

117 |

| Percentage of years in special education |

112 |

16 |

28 |

A 2000 report by the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Project reported that Perry Preschool graduates had significantly lower crime, delinquency, teenage pregnancy, and welfare dependency rates than the no-preschool group. The report concluded that:

the program group has demonstrated significantly higher rates of prosocial behavior, academic achievement, employment, income, and family stability as compared with the control group. The success of this and similar programs demonstrates intervention and delinquency prevention in terms of both social outcome and cost effective ness [emphasis in original].

In 2004, High/Scope researchers reported the continued educational success of Perry Preschool. Of particular importance for human capital economists were the reported economic benefits:

- More of the group members who received high-quality early education than the non-program group was employed at age 40 (76 vs. 62 percent).

- Group members who received high-quality early education had median annual earnings of more than $5,000 higher than the non-program group ($20,800 vs. $15,300).

- More of the group members who received high-quality early education owned their own homes.

- More of the group members who received high-quality early education had a savings account than the non-program members (76 vs. 50 percent).

The findings concluded, “Overall, the study documented a return to society of more than $16 for every tax dollar invested in the early care and education program.”

All of these studies reinforce the claim that investment in preschool yields high rates of economic returns for the participants and nation. They also suggest that preschool will reduce the cost to the public of special education programs, the criminal justice system, unemployment, and losses to crime victims. Table 4.2 shows the cost-benefit data reported by Carneiro and Heckman.

However, there are some issues regarding the replication of the Perry Preschool study. One is the sample size and location. The sample size for the study is small with only 123 low-income African American children between ages 3 and 4 who were considered at high risk of school failure. Only fifty-eight attended the Perry Preschool program while the other sixty-five received no preschool. Can a study using only fifty-eight pre school students justify the economic value of preschool?

The research group, High/Scope, suggests another limitation on its applicability to other contexts. The study specifically uses low-income African American students in Ypsilanti Michigan. In answering the question about generalizability, High/Scope researchers state, “The external validity or generalizability of the study findings extends to those programs that are reasonably similar to the High/Scope Perry Preschool program.” By “reasonably similar” they mean a preschool taught by certified early childhood teachers that serves low-income families, enrolls children 3 to 4 years old, and meets daily for 2.5 hours.

In conclusion, the Perry Preschool study is used to support arguments on the economic value of preschool. However, as mentioned previously, there are issues about sample size and applicability in other cultural contexts. In recent studies the emphasis has been on non-cognitive abilities or soft skills in contrast to the early concern with intellectual development. The 2004 study of the Perry Preschool graduates relates their school achievement to non-cognitive abilities and attitudes:

the program group spent more time on homework and demonstrated more positive attitudes toward school at ages 15 and 19. More parents of program group members had positive attitudes regarding their children’s educational experiences and were hopeful that their children would obtain college degrees.

Table 4.2 Perry Preschool: Costs versus Benefits through Age 27

| Costs and Benefits |

Increased (1) and (2) Decreased Costs |

| Cost of preschool for each child aged 3–4 |

(1) $12,148 |

| Decreased cost of special education for Perry Preschool graduates |

(2) 6,365 |

| Decreased criminal justice system cost for ages 15 to 28 |

(2) 27,378 |

| Projected decreased criminal justice system cost for ages 29 to 44 |

(2) 22,817 |

| Income from increased employment ages 19 to 27 |

(2) 28,380 |

| Projected income from increased employment ages 28 to 65 |

(2) 27,565 |

| Decrease in losses to crime victims |

(2) 210,690 |

| Total benefits or decreased costs to public |

323,195 |

| Total benefits or decreased costs to public without projections for criminal justice costs and income |

300,378 |

| Benefits minus cost of preschool |

311,047 |

| Benefits minus cost of preschool without projections for criminal justice costs and income |

277,561 |

Do different family environments for preschool children affect children’s school achievement and, consequently, their economic futures? In other words, do children enter school with differing abilities as a result of dissimilar family backgrounds? Do these differences in family back grounds continue to affect learning throughout the student’s school years and do they have an effect on the level of a student’s educational attainment, such as graduating from high school or college and their future employment?

There are a number of studies purporting to show the importance of particular types of families in determining academic success. Like the Perry Preschool studies, these other studies can be questioned regarding their relevance to different forms of family lifestyles. Should the findings discussed in this section be used to try to change family structures to ensure success in school?

The key to answering these questions is the concept of social and cultural capital, which refers to the economic value of a person’s behaviors, attitudes, knowledge, and cultural experiences. It may be argued that education, which provides a person with particular knowledge and attitudes, is related to income and therefore has economic value when seeking employment. Also, behaviors learned in the home contribute to soft skills. Experiences in the home might provide the social knowledge that will help the child later climb the occupational ladder. Do the behaviors learned in the home prepare a child to interact with professionals and managers or do they prepare the child to feel comfortable only in social situations with blue-collar workers? Visits to museums, concerts, stage performances, and similar experiences increase children’s cultural capital, which may make them better prepared to interact with elite groups. In other words, what social and cultural experiences does the family provide that will help the child succeed in school and in later employment?

Variations in social and cultural capital affect the ability of children to learn in school and to gain future employment. In Unequal Childhoods: Class, Race, and Family Life, Annette Lareau writes:

Many studies have demonstrated that parents’ social structural location has profound implications for their children’s life chances. Before kindergarten, for example, children of highly educated parents are much more likely to exhibit “educational readiness” skills, such as knowing their letters, identifying colors, counting up to twenty, and being able to write their first names.

Lareau demonstrates that educational readiness is affected by differences in child-rearing practices. She distinguishes child-rearing practices by the terms “concerted cultivation” and “accomplishment of natural growth.” Concerted cultivation is practiced by what she calls “middle-class” families and accomplishment of natural growth by “working-class” families.

The terms middle class and working class have a special meaning in Lareau’s work. Throughout this chapter, I highlight differing definitions of social class. For Lareau’s purposes, a middle-class family is one where one or both parents have supervisory or managerial authority in the workplace and are required to have stringent educational credentials. In working-class families, parents’ occupations are without supervisory authority and do not require a high level of educational credentials.

Differences in child-rearing between working- and middle-class families are summarized in Table 4.3. Lareau concludes that middle-class families consciously intervene (concerted cultivation) in their children’s lives to develop their talents. In contrast, working-class families have a more laissez-faire attitude, allowing their children to grow without much intervention (accomplishment of natural growth) apart from attending to their basic needs.

Table 4.3 Differences in Child-Rearing between Working- and Middle-Class Families

|

Middle-Class Concerted Cultivation |

Working-Class Accomplishment and Natural Growth |

| General |

Parents involve children in multiple organized activities such as sports, music and dance lessons, and arts, crafts, and hobby groups. |

Children “hang out” with siblings, friends, and relatives while parents involve them in a minimum of organized activities. |

| Speech |

Parents reason with their children, allowing them to challenge their statements and negotiate. |

Parents issue directives and seldom allow their children to challenge or question these directives. |

| Dealings with institutions |

Parents criticize and intervene in institutions affecting the child, such as school, and train their children to assume a similar role. |

Parents display powerlessness and frustration toward institutions, such as school. |

| Results |

Children gain the social and cultural capital to deal with a variety of social situations and institutions. |

Children develop social and cultural capital that results in dependency on institutions and jobs where they take orders rather than manage others. |

Imagine the life of middle-class children as detailed in Table 4.3. Their parents spend time chauffeuring them from training events and competitions in organized sports, to music and dance lessons, to an art, craft, or hobby group. After-school time and weekends are packed with events as parents try to develop their children’s various talents. If their children encounter any problems in these activities, parents quickly intervene and discuss the situation with the coach, trainer, or teacher.

These middle-class parents influence their children’s behavior through reasoned discussion in which their children learn to question their parents’ arguments if they think their parents are wrong.

According to Lareau, the result of concerted cultivation is the development of the social and cultural capital that allows the children and later adults to feel comfortable and know how to act in a variety of social and institutional situations; this is a result of all those after-school activities. Middle-class children learn to interact, challenge, and reason with authority; this is learned through their interaction with their parents and the model of their parents questioning institutional authority. Their cultural capital is increased through participation in activities such as dance and music lessons, and attendance at cultural institutions.

In contrast, working-class parents, Lareau argues, allow their children to spend unstructured time with their friends and relatives in their yards, in local parks, on the street, or in another home. The most frequently planned activity for children is some form of organized sports. Working-class parents tell their children what to do and don’t allow the children to be sassy and talk back. When problems occur at school or other institutions their children may encounter, the parents act powerless.

Working-class accomplishment of natural growth, according to Lareau, results in social capital that does not contain the skills to interact in a variety of social and institutional situations. The children lack the verbal ability and behavioral skills needed to become managers and supervisors. They primarily assume jobs where they take rather than give orders. They lack the verbal skills, social graces, and dress to interview for jobs as bank managers, but they do have the social capital to accept low-paying jobs where they are given orders. Without exposure to museums, art and dance lessons, and attendance at concerts and stage performances, these children do not gain the cultural capital to move easily among the social elite.

The social and cultural capital developed in middle- and working-class families has different economic value. First, middle- and working-class children have different social and cultural capital when interacting with schools. These forms of capital are needed for educational success and, consequently, have economic value when educational achievement helps people gain higher paying jobs. Middle-class children have learned the verbal and social skills to advantage themselves when interacting with teachers and school staff. If something negative happens to them at school, their parents are quick to intervene on their behalf. The opposite is true of working-class children. Their social and cultural capital hinders their ability to succeed at school. The social and cultural capital of middle-class children increases their possibilities of gaining jobs high on the income scale while working-class children have the social and cultural capital to work in jobs low on the income scale.

In conclusion, the promise of schooling providing equality of opportunity to compete for income and wealth is seriously compromised before the child even enters the classroom. Parents develop different forms of social and cultural capital which advantage or disadvantage their children in school and in the labor market. In the next section, I discuss how family background is related to the actual reading and math skills of children as they enter kindergarten and which advantages or disadvantages them throughout their school careers.

Valerie Lee and David Burkham’s report Inequality at the Starting Gate: Social Background Differences in Achievement as Children Begin School confirms the fears of early common-school advocates that family background would compromise the ability of schools to provide equality of opportunity. Students entering kindergarten have significantly different reading and ability skills as measured by tests given as part of the U.S. Department of Education’s Early Childhood Longitudinal Study, Kindergarten Cohort. Test results show differences that are correlated with social class and race, with social class being the most important factor.

What are the preschool family factors affecting reading and math skills of children entering kindergarten? The following could be considered a parental guide for ensuring that children have high reading and math skills as measured by tests on entering kindergarten. Lee and Burkham found the strongest correlation between family factors and reading skills on entering kindergarten to be:

- Frequency of reading (including parents reading to their children).

- Ownership of a home computer.

- Exposure to performing arts.

- Preschool.

Other factors weakly correlated with reading skills are:

- 5.Educational expectations of family.

- 6.Rules limiting television viewing.

- 7.Number of tapes, records, CDs.

- 8.Sports and clubs.

- 9.Arts and crafts activities.

For math scores, the most strongly correlated family factors are:

- Ownership of a home computer.

- Exposure to performing arts.

- Preschool.

Other factors weakly correlated with math skills are:

- 4.Educational expectations.

- 5.Frequency of reading (including parents reading to their children).

- 6.Number of tapes, records, CDs.

- 7.Sports and clubs.

- 8.Arts and crafts activities.

Therefore, if parents were planning to prepare their child to enter kindergarten with high reading and math scores they would read to their child, own a computer, take their child to performing arts events, and send their child to preschool. In addition, they should have high expectations for their child’s education; have rules governing television viewing; have a large amount of media in the home, such as tapes, records, and CDs; and involve their child in sports, clubs, and arts and crafts.

Table 4.4 Socioeconomic Status and Math and Reading Scores at the Beginning of Kindergarten

| Socioeconomic Status of Family |

Reading Scores |

Math Scores |

| Highest 20% |

27.2 |

24.1 |

| Next highest 20% |

23.6 |

21.0 |

| Middle 20% |

21.3 |

19.1 |

| Next lowest 20% |

19.9 |

17.5 |

| Lowest 20% |

17.4 |

15.1 |

Social class is directly related to kindergarten entrance test scores and family factors correlated with high reading and math scores. Using a different definition of social class than Lareau’s separation of families into middle and working class, Lee and Burkham divide families by SES, or socioeconomic status, which is determined by a combination of occupation, income, educational attainment, and wealth. They divide SES into quintiles or gradations of 20 percent. Those in the lowest SES represent the 20 percent at the bottom of the SES scale in occupation, income, education, and wealth while the highest are in the top 20 percent. Table 4.4 reports math and reading achievement at the beginning of kindergarten by SES. Test scores are those used by Lee and Burkham in analyzing the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study, Kindergarten Cohort.

As noted in Table 4.4, reading and math skills on entering kindergarten are closely related to the family SES as measured by tests in the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study: the higher the SES of the family, the higher the test scores; the lower the SES of the family, the lower the test scores.

Is there a relationship between family SES and activities that are correlated with high test scores? Table 4.5 shows the relationship found by Lee and Burkham.

As indicated in Table 4.5, upper SES families are more likely than lower SES families to expose their children to factors that are correlated with high math and reading scores upon entering kindergarten. No wonder children from higher SES families have higher scores on tests measuring math and reading skills when entering kindergarten. Simply stated, families provide their children with differing cultural capital needed to succeed in school. Lee and Burkham’s study seems to confirm fears that family background could hinder the ability of schools to provide equality of opportunity.

Table 4.5 Socioeconomic Status and Family Activity Correlated with Math and Reading Scores at the Beginning of Kindergarten

| Socioeconomic Status of Family |

Percentage of Kindergartners with a Computer in the Home |

Percentage of Kindergartners Whose Parents Read to Them at Least Three Times a Week |

Percentage of Kindergartners Who Attend Preschool |

Percentage of Kindergartners Who Attend Performing Arts Events (play/ concert/show) |

| Highest 20% |

84.7% |

93.9% |

65.0% |

48.4% |

| Next highest 20% |

71.5 |

87.3 |

52.2 |

43.0 |

| Middle 20% |

54.7 |

80.7 |

41.7 |

38.9 |

| Next lowest 20% |

38.3 |

76.6 |

31.2 |

33.9 |

| Lowest 20% |

19.9 |

62.6 |

20.1 |

27.1 |

As discussed throughout this chapter there are many indicators that family income is related to school achievement. What about children living in poverty? It would appear from most evidence that the conditions surrounding childhood poverty hinder school achievement. Table 4.6 provides the official 2012 U.S. government definition of poverty based on income and size of household. For instance, according to Table 4.6 a single person living alone is poor if their annual income is below $11,888. A family of four is poor if their household income is below $23,834.

Table 4.6 Poverty Guidelines for the Forty-Eight Contiguous States and the District of Columbia (2013)

| Persons in Family/ Household |

Poverty Guideline |

| 1 |

$11,888 |

| 2 |

15,142 |

| 3 |

18,552 |

| 4 |

23,834 |

| 5 |

28,265 |

| 6 |

31,925 |

| 7 |

36,384 |

| 8 |

40,484 |

As indicated in Table 4.7, the percentage of children living in poverty has increased for all racial/ethnic groups between 2006 and 2011. The percentage of all 5- to 17-year-olds, according to Table 4.7, living in poverty has increased from 17 percent in 2006 to 21 percent in 2011.

Table 4.7 Percentage of 5- to 17-Year-Olds Who Were Living in Poverty, by Race/ Ethnicity: 2006 and 2011

|

2006 |

2011 |

| Total |

17 |

21 |

| White |

10 |

12 |

| Black |

34 |

37 |

| Hispanic |

27 |

34 |

| Asian |

12 |

14 |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander |

No percentage given |

32 |

| American Indian/Alaska Native |

29 |

33 |

| Two or more races |

16 |

20 |

The highest poverty rate for children in this age range is found among those classified as black with 34 percent living in poverty in 2006 and 37 percent in 2011.

Table 4.8 Percentage of Public School Students in High-Poverty Schools, by Race/Ethnicity and School Level: School Year 2009–2010

| Race/ethnicity |

Percentage of Public School Students in High-Poverty Elementary Schools |

Percentage of Public School Students in High-Poverty Secondary Schools |

| White |

7 |

2 |

| Black |

46 |

21 |

| Hispanic |

45 |

21 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander |

14 |

7 |

| American Indian/Alaska Native |

35 |

17 |

Table 4.9 Percentage of Public School Students in Low-Poverty Schools, by Race/Ethnicity and School Level: School Year 2009–2010

| Race/ethnicity |

Percentage of Public School Students in Low-Poverty Elementary Schools |

Percentage of Public School Students in Low-Poverty Secondary Schools |

| White |

31 |

39 |

| Black |

7 |

12 |

| Hispanic |

11 |

15 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander |

37 |

39 |

| American Indian/Alaska Native |

9 |

17 |

Children living in poverty are often concentrated in high-poverty schools. The Condition of Education 2012 defines high-poverty and low-poverty schools as: “High-poverty schools are defined as public schools where 76 percent or more students are eligible for the free or reduced-price lunch (FRPL) program; and low-poverty schools are those schools where 25 percent or fewer students are eligible for FRPL.” As indicated in Tables 4.8 and 4.9, race/ethnicity is a factor in attendance at high-and low-poverty schools. For instance, 7 percent of whites attend high- poverty elementary schools and 2 percent attend high-poverty high schools. Compare this low percentage of white attendance to the high percentage of Hispanic attendance with 45 percent of Hispanic children attending high-poverty elementary schools and 21 percent attending high-poverty high schools. The situation is reversed, as indicated in Table 4.9, when considering attendance at low-poverty schools.

An important factor in raising school achievement could be reducing childhood poverty. However, reduction of childhood poverty is not something that schools can directly achieve. Reduction of childhood poverty depends on other government social and economic policies.

Human capital economics is now the driving force in public school policies. As indicated in this chapter, not all economists agree with the idea that investment in schooling will result in economic growth and higher personal incomes. In fact, increasing the number of school graduates may decrease the economic value of academic diplomas or, as it is called, cause educational inflation. For instance, many college graduates may be unable to obtain jobs that are related to their academic studies. Some areas of labor market may be flooded with college grad uates which, because of the oversupply of those seeking employment in that particular occupational field, may drive down salaries and force some who are educated for that occupation to seek other types of employment.

A more basic issue is whether or not public school policies, including the curriculum, methods of instruction, and testing, should be determined by the economic goal of growing the economy and educating workers for global economic competition. It could be argued that given the uncertainty of future labor market needs, students should be given a general education that would prepare them for all aspects of living including any type of employment. Others might argue that schooling should prepare students to improve the quality of society and their own happiness. Transmitting culture, including history, literature, and the arts, could be another goal of public schooling. In other words, should human capital economics dominate public school policies?

Achieve, Inc. “About Achieve.” http://www.achieve.org. This organization is composed of members of the National Governors Association and leading members of the business community dedicated to shaping the direction of U.S. schools.

Achieve, Inc America’s High Schools: The Front Line in the Battle for Our Economic Future. http://www.achieve.org. This document, issued for the 2005 National Education Summit on High Schools, stresses the importance of changing the high school curriculum to ensure the success of the U.S. in the global economy.

Achieve, Inc “National Education Summit on High Schools Convenes in Washington.” http://www.achieve.org/node/93. A report on the opening of the 2005 National Education Summit on High Schools.

Achieve, Inc., and the National Governors Association. An Action Agenda for Improving America’s High Schools: 2005 National Education Summit on High Schools. Washington, DC: Achieve, Inc. and the National Governors Association, 2005. This official report of the high school summit calls for a core high school curriculum of four years each of English and math.

Adecco. “The Skills Gap and the State of the Economy.” http://www.slideshare.net/AdeccoUSA/adecco-state-of-the-economy-survey-media-deck-final. This survey identifies the hard and soft skills wanted by global employers.

Becker, Gary. Human Capital. New York: Columbia University Press, 1964. The original explanation of the relationship between schooling and economic growth.

Bell, Daniel. The Coming of the Post-industrial Society. New York: Basic Books, 1973. One of the early books describing the transition to a knowledge economy.

Berliner, David, and Bruce Biddle. The Manufactured Crisis: Myths, Fraud and the Attack on America’s Public Schools. New York: Perseus Books, 1995. This book argues that there is little proof that public schools have declined and that schooling has affected America’s ability to compete in global markets.

Berrueta-Clement, John R. et al. Changed Lives: The Effects of the Perry Preschool Program on Youths Through Age 19. Ypsilanti, MI: Monographs of the High/Scope Educational Research Foundation, 1984. One of the early studies of the Perry Preschool program.

Brown, Phillip, and Hugh Lauder. “Globalization, Knowledge and the Myth of the Magnet Economy.” In Education, Globalization and Social Change, edited by Hugh Lauder, Phillip Brown, Jo-Anne Dillabough, and A.H. Halsey. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006, pp. 317–340. This chapter is critical of human capital arguments.

Carneiro, Pedro, and James J. Heckman. “Human Capital Policy.” In Inequality in America: What Role for Human Capital Policies?, edited by James J. Heckman and Alan Krueger. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2005, pp. 77–240. This chapter describes current concerns of human capital economists with the economic value of preschool.

Castells, Manuel. The Rise of the Network Society. Oxford: Blackwell, 2000. This book describes the relationship between new information technology and the knowledge society.

Democratic Party 2012 Platform. “Moving America Forward.” http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/papers_pdf/101962.pdf. This political platform emphasizes preparing students to make the U.S. number one in the global economy.

Desilver, Drew. “U.S. Income Inequality, on Rise for Decades, is now Highest since 1928.” Pew Research Organization (December 5, 2013). http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2013/12/05/u-s-income-inequality-on-rise-for-decades-is-now-highest-since-1928/. This report highlights the growing inequality of incomes in the United States.

Goldin, Claudia, and Lawrence Katz. The Race Between Education and Technology. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2008. This book argues that improved and more schooling for the knowledge economy is necessary for economic growth.

Hacker, Andrew. “Can We Make America Smarter?” The New York Review of Books (April 30, 2009). Economist Hacker disputes the basic ideas of human capital education and suggests that many occupations needing workers will primarily train them in the workplace.

Heckman, James J., and Alan Krueger, eds. Inequality in America: What Role for Human Capital Policies? Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2005. This book contains articles claiming that preschool education is the best educational investment for reducing poverty.

High/Scope Foundation. “High/Scope Perry Preschool Study.” http://www.highscope.org/. This website provides current information on Perry Preschool graduates.

Jacobson, Linda. “‘Summit’ Links Preschool to Economic Success.” Education Week. Published online September 11, 2007.

Keeley, Brian. Human Capital: How What You Know Shapes Your Life. Paris: OECD Publishing, 2007. Provides a simple explanation of how human capital economics can influence schooling.

Lareau, Annette. Unequal Childhoods: Class, Race, and Family Life. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003. This is a study of differing child-rearing methods between middle- and working-class families and their effect on the development of cultural capital.

Lee, Valerie E., and David T. Burkham. Inequality at the Starting Gate: Social Background Differences in Achievement as Children Begin School. Washington, DC: Economic Policy Institute, 2002. This book reports the impact of preschool experiences on math and reading tests at the beginning of kindergarten.

Parks, Greg. “The High/Scope Perry Preschool Project.” Juvenile Justice Bulletin. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, 2000. This study found positive results, particularly regarding reduced crime rates, among Perry Preschool graduates.

Partnership for America’s Economic Success. Telluride Economic Summit on Early Childhood Investment. http://www.partnershipforsuccess.org/index.php?id518. Conference advocated investment in early childhood education to stimulate economic growth.

Partnership for 21st Century Skills. 21st Century Skills, Education and Competitiveness. Tucson, AZ: Partnership for 21st Century Skills, 2008. Plan to prepare American schools to educate students to compete in the global economy.

Reich, Robert. The Work of Nations. New York: Vintage Books, 1992. One of the major forecasts regarding the nature of work in the global knowledge economy.

Schultz, Theodore. The Economic Value of Education. New York: Columbia University Press, 1963. Shultz provides economic arguments that investment in education will grow the economy and reduce income inequality.

Schweinhart, Lawrence, et al., “The High/Scope Perry Preschool Study Through Age 40: Summary, Conclusions, and Frequently Asked Questions.” High/Scope Press, 2005. http://www.highscope.org/file/Research/PerryProject/specialsummary_rev2011_02_2.pdf. This study includes questions about sample size and cultural context related to the Perry Preschool study.

The Condition of Education 2012. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, 2012. This report contains the characteristics of school students, including the number in poverty and attending high-poverty schools.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Education and Training Outlook for Occupations, 2012–22 (2012).” http://www.bls.gov/emp/ep_edtrain_outlook.pdf. This statistical report projects future jobs and their educational requirements.

U.S. Census Bureau. “Poverty Thresholds by Size of Family and Number of Children 2013.” https://www.census.gov/hhes/www/poverty/data/threshld/index.html. This report provides a definition of poverty based on federal guidelines.