Equality of Educational Opportunity

Race, Gender, and Special Needs

This chapter focuses on the issue of equality of educational opportunity. In contrast to equality of opportunity to compete in the labor market, equality of educational opportunity refers to giving everyone an equal chance to receive an education. When defined as an equal chance to attend school, equal educational opportunity is primarily a legal issue. In this context, the provision of equal educational opportunity may be defined solely on the grounds of justice: If government provides a service like education, all classes of citizens should have equal access to that service.

Another aspect of equality of educational opportunity is the treatment of students in schools. Are all students given an equal chance to learn in schools? Do students of different races and gender receive equal treatment in schools? Is there equality of educational opportunity for students with special needs? This chapter discusses the following issues regarding equality of educational opportunity:

- The legal issues in defining race.

- The major court decisions and laws involving equality of educational opportunity.

- Current racial segregation in schools.

- The struggle for equal educational opportunity for women.

- Students with disabilities and equality of educational opportunity.

The problems courts have in defining race is illustrated by the famous 1896 U.S. Supreme Court case Plessy v. Ferguson, which allowed segregation of public schools (I discuss the details of this case in the next section). According to the lines of ancestry as expressed at that time, Plessy was one-eighth African American and seven-eighths white. Was Homer Plessy white or black? What was the meaning of the term white? Why wasn’t Plessy classified as white since seven-eighths of his ancestry was white and only one-eighth was black? Why did the court consider him black?

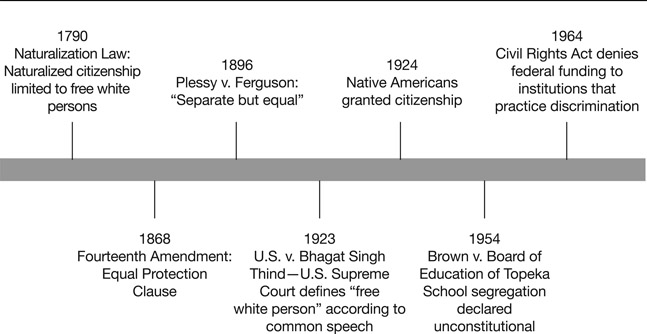

Plessy v. Ferguson highlights the principle that race is a social and legal construction. The U.S. legal system was forced to construct a concept of race because the 1790 Naturalization Law limited naturalized citizenship to immigrants who were free white persons. This law did not define “white” and it excluded Native Americans from citizenship. The limitation on being “white” for naturalized citizenship remained until 1952. Because of the law, U.S. courts were forced to define the meaning of white persons. Adding to the legal problem was that most southern states in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries adopted the so-called one drop of blood rule, which classified anyone with an African ancestor, no matter how distant, as African American. Under the one drop of blood rule, Homer Plessy was considered black.

The startling fact about the many court cases dealing with the 1790 law was the inability of the courts to rely on scientific evidence in defining white persons. Consider two of the famous twentieth-century court cases. The first, Takao Ozawa v. United States (1922), involved a Japanese immigrant who graduated from high school in Berkeley, California, and attended the University of California. He and his family spoke English and attended Christian churches. A key issue in Takao Ozawa v. United States was whether “white persons” referred to skin color. Many Japanese are fair skinned. The Court responded to this issue by rejecting skin color as a criterion. The Court stated,

The test afforded by the mere color of the skin of each individual is impracticable, as that differs greatly among persons of the same race, even among Anglo-Saxons, ranging by imperceptible gradations from the fair blond to the swarthy brunette, the latter being darker than many of the lighter hued persons of the brown and yellow races [emphasis added].

Rejecting the idea of skin color, the Court recognized the term Caucasian to define white persons – and denied citizenship to Takao Ozawa.

However, the following year the U.S. Supreme Court rejected Caucasian as a standard for defining white persons in United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind (1923). In this case, an immigrant from India applied for citizenship as a Caucasian. According to the scientific rhetoric of the time, Thind was a Caucasian. Faced with this issue, the Court suddenly dismissed Caucasian as a definition of white persons. The Court argued, “It may be true that the blond Scandinavian and the brown Hindu have a common ancestor in the dim reaches of antiquity, but the average man knows perfectly well that there are unmistakable and profound differences between them today.” Therefore, rather than relying on a scientific definition as it had in Takao Ozawa v. United States, the U.S. Supreme Court declared, “What we now hold is that the words ‘free white persons’ are words of common speech, to be interpreted in accordance with the understanding of the common man.” The Court never specified who was to represent this common man. Thind was denied citizenship.

U.S. court histories are filled with efforts to define race. My nineteenth-century ancestors on my father’s side were denied U.S. citizenship and were recognized as having only tribal citizenship despite the fact that many of their ancestors were European. Until Native Americans were granted U.S. citizenship in 1924, many so-called mixed-blood Native-Americans were limited to tribal citizenship. The confusion over legal racial categories was exemplified by an 1853 California court case involving the testimony of immigrant Chinese witnesses regarding the murder of another Chinese immigrant by one George Hall. The California Supreme Court overturned the murder conviction of Hall by applying a state law that disallowed court testimony from blacks, mulattos, and Native Americans. California’s chief justice ruled that the law barring the testimony of Native Americans applied to all “Asiatics” since, according to theory, Native Americans were originally Asians who crossed into North America over the Bering Straits. Therefore, the Chief Justice argued, the ban on court testimony from Native Americans applied to “the whole of the Mongolian race.”

The effect of this questionable legal construction of race was to heighten tensions among different groups of Americans. Many of those classified as African American have European and Native American citizenship. However, because of the one drop of blood rule and legal support of segregation, the possibilities for continuing assimilation and peaceful coexistence between so-called whites and blacks were delayed and replaced by a tradition of hostility between the two groups.

The 1965 Immigration Act shifted the bias of immigration laws from favoring European immigrants to a broader acceptance of immigrants from all the world’s regions. However, this new immigration law did little to define the meaning of race. According to the 2010 census (the reader is reminded that the official census is required by the US Constitution to be taken every ten years), being classified as African American is problematic, with one in ten blacks being foreign-born and with Africa accounting for one in three of foreign-born blacks. Is an African American a person with ancestry that can be traced to American slavery or any person with ancestors from Africa? Is it any person with African ancestry even if he or she was born in Africa, the Caribbean, or Central and South America? In 2014, the U.S. Census Bureau announced that the African-born population of the US had doubled every decade since 1970. The Census Bureau reported:

The foreign-born population from Africa has grown rapidly in the United States during the last 40 years, increasing from about 80,000 in 1970 to about 1.6 million in the period from 2008 to 2012, according to a U.S. Census Bureau brief released today [October 1, 2014].

What about the racial category of white? Eighty-seven percent of Americans born in Cuba and 53 percent born in Mexico identified themselves as white. However, many immigrants from Cuba and Mexico identify themselves as Hispanic or Latino and Latina. Adding to the confusion about racial labels, one in fifty Americans identify themselves as “multiracial.” Immigrants from the Dominican Republic and El Salvador describe themselves as neither black nor white. Rather than race, many immigrants identify themselves by their countries of origin or world regions, such as Africa and Asia.

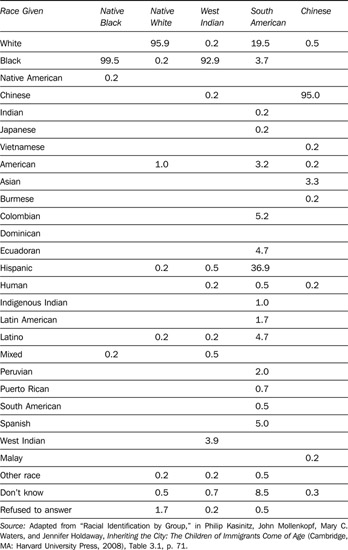

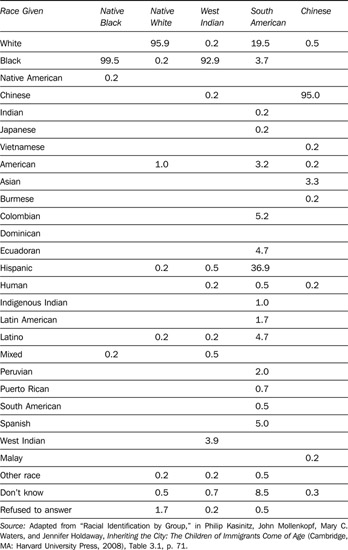

Concerning the racial identity of students, the 2008 book Inheriting the City: The Children of Immigrants Come of Age reports a survey of racial concepts in New York City schools. First- and second-generation immigrants when asked their race used a variety of descriptors, including nationality, ethnicity, culture, and language. In other words, racial identity varied among new immigrant groups. There were also variations of the concept of race within each immigrant group. In contrast, more than 90 percent of native-born African Americans and whites express a clear racial identity as black or white. The range of racial identifiers among other groups, even among non-immigrant groups such as Puerto Ricans, is amazing, and highlights variations in the social meaning of race. The majority of Puerto Ricans identify their race in either ethnic or group concepts. For instance, 30.4 percent of Puerto Ricans gave their racial identity as Puerto Rican and 26 percent as Hispanic. Other racial identities among Puerto Ricans include white, black, American, indigenous Indian, human, Latin American, Latino, mixed, and Spanish.

First- and second-generation immigrants provide a similar range of racial concepts. For instance, 95 percent of first- and second-generation Chinese immigrants gave their race as Chinese, while others gave their racial identity as American, Asian, or don’t know. Some Chinese identified their race according to country of origin – there are many Chinese communities around the world – such as Vietnamese, Burmese, and Malay. In these countries, they are considered ethnic Chinese. The largest range of racial identifiers is among first- and second-generation immigrants from the Dominican Republic and South America. Among Dominicans racial identifiers include white, black, Indian, American, Dominican, Hispanic, human, Latin American, Latino, mixed, Spanish, and West Indian. Some people state that they don’t know their race. For South Americans the range is even greater, and includes countries from which people originally immigrate to South America such as Japan. South Americans identified their race as white, black, Indian, Japanese, American, Asian, Colombian, Ecuadoran, Hispanic, human, Latin American, Latino, South American, and Spanish.

The variety of responses from first- and second-generation immigrants regarding race indicates the changing character of racial concepts since earlier in American history when they were defined by American law and judicial rulings. The only ones who continue to think in former legal and judicial racial concepts are native-born African Americans and whites. Table 5.1 provides a short summary of the racial identities of first- and second-generation immigrants in New York City (a more complete table of racial identities may be found in Inheriting the City: The Children of Immigrants Come of Age). Are U.S. citizens in transition to a society where concepts of race are less important in determining social status? One indication of this possibility is those people who give their racial identity as human.

For the past several ten-year U.S. Census racial classifications have proven problematic. To resolve problems in defining a person’s race, the U.S. Census Bureau is using personal self-identification and a variety of categories. For example, Item 8 of the 2010 Census form asks if a person is “Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish Origin.” This is a complex issue because of problems inherent in the terms Hispanic and Latino which might encompass only Spanish speakers from the Caribbean or Central and South America. However, there are peoples from these regions who speak English (such as Jamaica, Barbados, Belize, and Guyana), French (such as Haiti and Martinique), Portuguese (such as Brazil), and a variety of Native Americans speaking indigenous languages. To guide the responder, Item 8 offers the following choices:

- No, not of Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish Origin.

- Yes, Mexican, Mexican Am., Chicano.

- Yes, Puerto Rican.

- Yes, Cuban.

Table 5.1 What Does “Race” Mean? Varieties of Racial Identities among Native and Immigrant Groups (Percentage)

- Yes, another Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin – Print origin, for example, Argentinean, Colombian, Dominican, Nicaraguan, Salvadoran, Spanish, and so on.

These options for Item 8 gloss over the fact that some immigrants from the Caribbean and Central and South America are not Spanish speakers. What happens to non-Spanish speakers from these regions? They are not identified in the Census.

The 2010 Census’s Item 9 grapples with the multiple meanings of race. Item 9 asks responders to identify their race. The choices exclude any indigenous peoples who do not identify themselves as “American.” In other words, indigenous peoples from Central and South America have no way of identifying themselves in the 2010 Census, nor do non-Spanish speakers from the Caribbean and Central and South America, as previously noted. Item 9 provides the following options for responders to identify their race:

- White.

- Black, African Am., or Negro.

- American Indian or Alaska Native – Print name of enrolled or principal tribe.

- Asian Indian.

- Chinese.

- Filipino.

- Other Asian – for example, Hmong, Laotian, Thai, Pakistani, Cambodian, and so on.

- Japanese.

- Korean.

- Vietnamese.

- Native Hawaiian.

- Guamanian or Chamorro.

- Samoan.

- Other Pacific Islander – print race, for example, Fijian, Tongan, and so on.

As indicated by the responses provided by the 2010 Census form, the concept of “race” includes nationality (such as Japanese), skin color (such as white or black), and tribal affiliation (American Indian or Alaskan Native).

Racial classifications are complicated when considered against the background of nationality. For instance, how do you classify those Mexicans whose ancestors were African? A 2014 New York Times article posed the question in its title: “Negro? Prieto? Moreno? A Question of Identity for Black Mexicans.” Mexico at one time had enslaved Africans. Their descendants worry about their identity in a society dominated by mestizos with many terms being used, such as Afromexican, moreno, mascogo, jarocho, and costeño. How should this population of African descendants from Mexico be classified if they migrate to the United States? Today, the issue of racial classification is tied to the concept of equality of educational opportunity. In addition, current school policies are trying to reduce the gap in test scores between so-called minority groups. But how are these minority groups classified – by skin color, national origin, or tribal affiliation? While racial identification is a problematic concept, the public schools, as I discuss in the next section, must provide equal educational opportunity.

Equal treatment by the law is the great legal principle underlying the idea of equality of educational opportunity. This concept is embodied in the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution and provides that everyone should receive equal treatment under the law and no one should receive special privileges or treatment because of race, gender, religion, ethnicity, or wealth. This means that if a government provides a school system, then everyone should be treated equally by that system; everyone should have equal access to that educational system.

Added in 1868, the purpose of the Fourteenth Amendment was to protect the basic guarantees of the Bill of Rights against laws passed by state and local governments. The Fourteenth Amendment guarantees that states cannot take away any rights granted to an individual as a citizen of the United States; this means that although states have the right to provide schools, they cannot in their provision of schools violate citizen rights granted by the Constitution. The wording of Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amendment is extremely important in a variety of constitutional issues related to education, particularly equality of educational opportunity.

Fourteenth Amendment

All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside. No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property without due process of law [Due Process Clause]; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws [Equal Protection Clause].

These few lines of the Fourteenth Amendment are important for state-provided and state-regulated schools. For instance, “no state shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States” means that the courts can protect the constitutional rights of students and teachers particularly with regard to freedom of speech and issues related to religion. The Due Process Clause is invoked in cases that involve student suspensions and teacher firings. Since states provide schools to all citizens, they cannot dismiss a student or teacher without due process. As we shall see later in this chapter, the courts established guidelines for student dismissals.

All the protections of the Fourteenth Amendment depend on the states making some provision for education. Once a state government provides a system for education, it must provide it equally to all people in the state. The Equal Protection Clause is invoked in cases that involve equal educational opportunity and is central to cases that involve school segregation, non-English-speaking children, school finance, and children with special needs.

Originally, the U.S. Supreme Court in 1896 interpreted equal protection as allowing for “separate but equal.” In other words, segregated education based on race could be legal under the Fourteenth Amendment if all the schools were equal. The separate but equal ruling occurred in the previously mentioned 1896 U.S. Supreme Court decision Plessy v. Ferguson. The U.S. Supreme Court’s decision was that segregated facilities could exist if they were equal. This became known as the separate but equal doctrine.

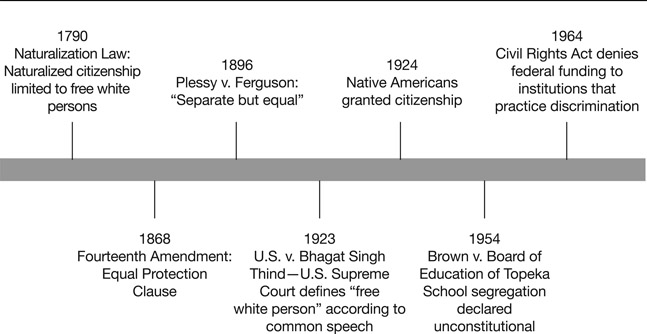

Figure 5.1 Timeline of Events Discussed: Quality of Educational Equality

The 1954 desegregation decision Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka overturned the separate but equal doctrine by arguing that segregated education was inherently unequal. This meant that even if school facilities, teachers, equipment, and all other physical conditions were equal between two racially segregated schools, the two schools would still be unequal because of the racial segregation.

In 1964, Congress took a significant step toward speeding up school desegregation by passing the important Civil Rights Act. Title VI of the 1964 Civil Rights Act provided a means for the federal government to force school desegregation. In its final form, Title VI required the mandatory withholding of federal funds from institutions that practiced racial discrimination. Title VI states that no person, because of race, color, or national origin, can be excluded from or denied the benefits of any program receiving federal financial assistance. It required all federal agencies to establish guidelines to implement this policy. Refusal by institutions or projects to follow these guidelines was to result in the “termination of or refusal to grant or to continue assistance under such program or activity.”

Title VI of the 1964 Civil Rights Act remains important for two reasons. First, it established a major precedent for federal control of American public schools by making it explicit that the control of money would be one method used by the federal government to shape local school policies. (This aspect of the law will be discussed in more detail in Chapter 9.) Second, it turned the federal Office of Education into a policing agency with the responsibility of determining whether school systems were segregated and, if they were, of doing something about the segregated conditions.

Title VI speeded up the process of school desegregation in the South, particularly after the passage of federal legislation in 1965 which increased the amount of money available to local schools from the federal government. In the late 1960s, southern school districts rapidly began to submit school desegregation plans to the Office of Education.

In the North, prosecution of inequality in educational opportunity as it related to school segregation required a different approach from that used in the South. In the South, school segregation existed by legislative acts that required separation of the races. There were no specific laws requiring separation of the races in the North. But even without specific laws, racial segregation existed. Therefore, it was necessary for individuals bringing complaints against northern school districts to prove that the existing patterns of racial segregation were the result of purposeful action by the school districts. It had to be proved that school officials intended racial segregation to be a result of their educational policies.

The conditions required to prove segregation were explicitly outlined in 1974, in the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals case Oliver v. Michigan State Board of Education. The court stated, “A presumption of segregative purpose arises when plaintiffs establish that the natural, probable and foreseeable result of public officials’ action or inaction was an increase or perpetuation of public school segregation.” This did not mean that individual motives or prejudices were to be investigated but that the overall pattern of school actions had to be shown to increase racial segregation; that is, in the language of the court, “the question whether a purposeful pattern of segregation has manifested itself over time, despite the fact that individual official actions, considered alone, may not have been taken for segregative purposes.”

In 2014, sixty years after the 1954 Brown desegregation ruling by the Supreme Court, the UCLA Civil Rights project founded by Gary Orfield and Christopher Edley, Jr. released its report on current school segregation. The report noted that since the court decision there has been a 30 percent drop in white students and an increase of close to 500 percent in Latino students. Its major conclusions are as follows:

- Black and Latino students comprise an increasingly large percentage of suburban enrollment, particularly in larger metropolitan areas, and are moving to schools with relatively few white students.

- Segregation for blacks is the highest in the northeast, a region with extremely high district fragmentation.

- Latinos are now significantly more segregated than blacks in suburban America.

- Black and Latino students tend to be in schools with a substantial majority of poor children, while white and Asian students typically attend middle-class schools.

- Segregation is by far the most serious in the central cities of the largest metropolitan areas; the states of New York, Illinois, and California are the top three worst for isolating black students.

- California is the state in which Latino students are most segregated.

In the above findings it is important to note the increasing numbers of black and Latino students in suburban school districts, reflecting a general movement of minority populations out of central cities. And, unlike the past, Latino students are now more segregated in schools than black students. Also, Latino and black students are economically segregated and are more likely to attend schools with a high concentration of low-income students. Also, Latinos are more segregated in California schools, while central cities in New York, Illinois, and California have the greatest segregation of black students.

The reader should check the websites of the following organizations for current issues, policies, and the history of struggle regarding women’s education: American Association of University Women (http://www.aauw.org), National Organization for Women Foundation (http://www.nowfoundation.org), and Education Equality of the Feminist Majority Foundation (http://www.feminist.org/education). These organizations are in the forefront in protecting women’s rights in education.

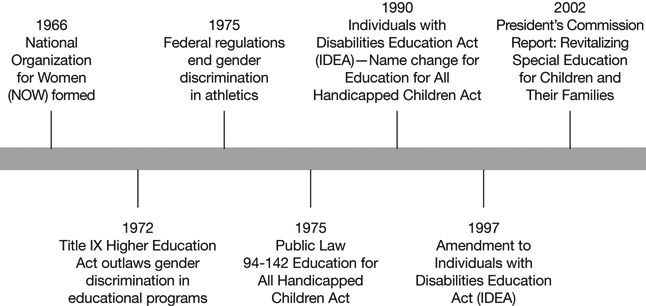

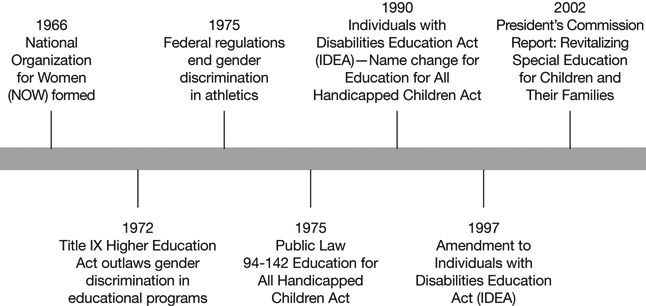

Since the nineteenth century, the struggle for racial justice has paralleled that of justice for women. Demands for equal educational opportunity pervaded both campaigns for civil rights. In the second half of the twentieth century the drive for equal educational opportunities for women was led by the National Organization for Women (NOW), which was organized in 1966. The founding document of the organization declared, “There is no civil rights movement to speak for women as there has been for Negroes and other victims of discrimination.”

NOW’s activities and those of other women’s organizations turned to legal action with the passage of Title IX of the 1972 Higher Education Act. Title IX states: “No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving federal financial assistance.” The legislation applied to all educational institutions, including preschool, elementary and secondary schools, vocational and professional schools, and public and private undergraduate and graduate institutions. A 1983 U.S. Supreme Court decision, Grove City College v. Bell, restricted the application of Title IX to specific educational programs within institutions. In the 1987 Civil Rights Restoration Act, Congress overturned the Court’s decision and amended Title IX to include all activities of an educational institution receiving federal aid. Armed with Title IX, NOW and other women’s organizations placed pressure on local school systems and colleges to ensure equal treatment of women in vocational education, athletic programs, textbooks and the curriculum, testing, and college admissions.

In 2014, the federal government updated the coverage of Title IX to protect all students, regardless of sexual orientation or gender identity. The US Department of Education released the following guidelines for Title IX:

Title IX protects all students at recipient institutions from sex discrimination, including sexual violence. Any student can experience sexual violence: from elementary to professional school students; male and female students; straight, gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender students; part-time and full-time students; students with and without disabilities; and students of different races and national origins [emphasis in original].

In addition, under these guidelines gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender students are protected against discrimination and sexual harassment and violence. These guidelines broaden the scope of Title IX and allow the federal Office of Civil Rights to handle complaints about bullying of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender students.

Title IX’s sex discrimination prohibition extends to claims of discrimination based on gender identity or failure to conform to stereotypical notions of masculinity or femininity. OCR accepts complaints about these issues and can launch an investigation. Similarly, the actual or perceived sexual orientation or gender identity of the parties does not change a school’s obligations. Indeed, lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) youth report high rates of sexual harassment and sexual violence. A school should investigate and resolve allegations of sexual violence regarding LGBT students, employing the same procedures and standards that it uses in all complaints involving sexual violence.

In addition, the new guidelines require schools to investigate any negative comments about a student’s sexual orientation:

The fact that incidents of sexual violence may be accompanied by anti-gay comments or be partly based on a student’s actual or perceived sexual orientation does not relieve a school of its obligation under Title IX to investigate and remedy those instances of sexual violence.

Providing an example of discrimination against transgender youth, Education Week’s reporter Evie Blad wrote in 2014,

I’ve written previously about a transgender student suing her school when administrators refused to let her use girls’ restrooms because she was born a boy. In January, a new California law went into effect that allows transgender students to use single-sex facilities and join sex-segregated teams that match their gender identities. Supporters of that law have pushed for federal guidance that addresses such issues.

By the 1960s, the civil rights movement encompassed students with disabilities. Within the context of equality of educational opportunity, students with special needs could participate equally in schools with other students only if they received some form of special help. Since the nineteenth century, many of the needs of these students have been neglected by local and state school authorities because of the expense of special facilities and teachers. In fact, many people with disabilities were forced to live in state institutions for persons with mental illness or retardation. For instance, consider “Allan’s story,” a case history of treatment prior to the 1970s, provided by the U.S. Office of Special Education Programs:

Allan was left as an infant on the steps of an institution for persons with mental retardation in the late 1940s. By age 35, he had become blind and was frequently observed sitting in a corner of the room, slapping his heavily callused face as he rocked back and forth humming to himself.

In the late 1970s, Allan was assessed properly for the first time. To the dismay of his examiners, he was found to be of average intelligence; further review of his records revealed that by observing fellow residents of the institution, he had learned self-injurious behavior that caused his total loss of vision. Although the institution then began a special program to teach Allan to be more independent, a major portion of his life was lost because of a lack of appropriate assessments and effective interventions.

The political movement for federal legislation to aid students with disabilities followed a path similar to the rest of the civil rights movement. First, finding themselves unable to change educational institutions by pressuring local and state governments, organized groups interested in improving educational opportunities for students with special needs turned to the courts. This was the path taken in the late 1960s by the Pennsylvania Association for Retarded Children (PARC). PARC was one of many associations organized in the 1950s to aid citizens with disabilities. These organizations were concerned with state laws that excluded children with disabilities from educational institutions because they were considered uneducable and untrainable. State organizations like PARC and the National Association for Retarded Children campaigned to eliminate these laws and to demonstrate the educability of all children. But, as the civil rights movement discovered throughout the century, local and state officials were resistant to change and relief had to be sought through the judicial system.

In Pennsylvania Association for Retarded Children (PARC) v. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, a case that was as important for the rights of children with disabilities as the Brown decision was for African Americans, PARC objected to conditions in the Pennhurst State School and Hospital. In framing the case, lawyers for PARC focused on the legal right to an education for children with disabilities. PARC, working with the major federal lobbyist for children with disabilities, the Council for Exceptional Children (CEC), overwhelmed the court with evidence on the educability of children with disabilities. The state withdrew its case, and the court enjoined the state from excluding children with disabilities from a public education and required that every child be allowed access to an education. Publicity about the PARC case prompted other lobbying groups to file thirty-six cases against different state governments. The CEC prepared model legislation and lobbied for its passage at the state and federal levels.

In 1975, Congress passed Public Law 94–142, the Education for All Handicapped Children Act, that guaranteed equal educational opportunity for all children with disabilities. In 1990, Congress changed the name of this legislation to Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). In 2010, the twentieth anniversary of IDEA was commemorated by U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan with the statement:

The Americans with Disabilities Act is a landmark piece of civil rights legislation. It protects individuals with disabilities from discrimination and promotes their full inclusion into education and all other aspects of our society. I want to celebrate the progress that we’ve made and highlight our commitment to continuing the work of providing equal access for all Americans. I acknowledge we still have work to do and renew my commitment to ensuring that individuals of all ages and abilities have an equal opportunity to realize their full potential.

The major provisions in Public Law 94–142 provided for equal educational opportunity for all children with disabilities. This goal included the opportunity for all children with disabilities to attend regular school classes. As stated in the legislation, “all children with disabilities [should] have available to them … a free appropriate public education which emphasized special education and related services designed to meet their unique needs.”

In 2010, the U.S. Department of Education released its report “Thirty-five Years of Progress in Educating Children with Disabilities through IDEA” which listed the following four purposes:

- to assure that all children with disabilities have available to them … a free appropriate public education which emphasizes special education and related services designed to meet their unique needs.

- to assure that the rights of children with disabilities and their parents … are protected.

- to assist States and localities to provide for the education of all children with disabilities.

- to assess and assure the effectiveness of efforts to educate all children with disabilities.

In celebrating thirty-five years of the legislation, the report declared: “During these last 35 years, IDEA also has developed a national infra structure of supports that are improving results for millions of children with disabilities, as well as their nondisabled friends and classmates.”

The National Center for Educational Statistics in The Condition of Education 2008 provides a listing of disability categories. The percentage of students in schools for each disability in 2010/2011 is given in Table 5.2. The following are the disabilities recognized by the federal government.

- Autism: A developmental disability significantly affecting verbal and nonverbal communication and social interaction, generally evident before age 3, that adversely affects a child’s educational performance.

- Deaf-Blindness: Concomitant hearing and visual impairments, the combination of which causes severe communication and other devel op mental and educational problems.

Table 5.2 Children (aged 3–21) with Disabilities in Public Schools, 2010–2011

| Disabilities |

Percentage with Disability |

| All disabilities |

13 |

| Specific learning disabilities |

4.8 |

| Speech or language impairments |

2.8 |

| Intellectual disability |

0.9 |

| Emotional disturbance |

0.8 |

| Hearing impairments |

0.2 |

| Orthopedic impairments |

0.1 |

| Other health impairments |

1.4 |

| Visual impairments |

0.1 |

| Multiple disabilities |

0.3 |

| Autism |

0.8 |

| Traumatic brain injury |

0.1 |

| Developmental delay |

0.8 |

- Developmental Delay: This term may apply to children ages 3 through 9 who are experiencing developmental delays … who therefore need special education and related services.

- Emotional Disturbance: A condition exhibiting … characteristics over a long period of time and to a marked degree that adversely affects a child’s educational performance.

- Hearing Impairment: An impairment in hearing, whether permanent or fluctuating, that adversely affects a child’s educational perform ance.

- Mental Retardation: Significantly sub-average general intellectual functioning … that adversely affects a child’s educational perform ance.

- Multiple Disabilities: Concomitant impairments (such as mental retardation–-blindness, mental retardation, orthopedic impairment).

- Orthopedic Impairment: A severe orthopedic impairment that adversely affects a child’s educational performance.

- Specific Learning Disability: A disorder in one or more of the basic psychological processes involved in understanding or in using language, spoken or written, that may manifest itself in an imperfect ability to listen, think, speak, read, write, spell, or to do mathematical calculations.

- Speech or Language Impairment: A communication disorder such as stuttering, impaired articulation, a language impairment, or a voice impairment that adversely affects a child’s educational performance.

- Traumatic Brain Injury: An acquired injury to the brain caused by an external physical force, resulting in total or partial functional disability or psychosocial impairment, or both, that adversely affects a child’s educational performance.

- Visual Impairment: An impairment in vision that, even with correction, adversely affects a child’s educational performance.

One of the issues confronting Congress during legislative debates was that of increased federal control over local school systems. Congress resolved this problem by requiring that an individualized education plan (IEP) be written for each student with disabilities. This reduced federal control, since each IEP would be written in local school systems. IEPs are now a standard part of education programs for children with disabilities. Public Law 94–142 requires that an IEP be developed for each child jointly by the local educational agency and the child’s parents or guardians. This gives the child or the parents the right to negotiate with the local school system about the types of services to be delivered.

According to U.S. guidelines, after a student is identified as having a disability:

The school system schedules and conducts the IEP meeting. School staff must:

- contact the participants, including the parents;

- notify parents early enough to make sure they have an oppor tunity to attend;

- schedule the meeting at a time and place agreeable to parents and the school;

- tell the parents the purpose, time, and location of the meeting;

- tell the parents who will be attending; and

- tell the parents that they may invite people to the meeting who have knowledge or special expertise about the child.

The government guidelines specify the following process in writing an IEP:

- The IEP team gathers to talk about the child’s needs and write the student’s IEP. Parents and the student (when appropriate) are part of the team. If the child’s placement is decided by a different group, the parents must be part of that group as well.

- Before the school system may provide special education and related services to the child for the first time, the parents must give their consent.

- The child begins to receive services as soon as possible after the meeting.

- If the parents do not agree with the IEP and placement, they may discuss their concerns with other members of the IEP team and try to work out an agreement. If they still disagree, parents can ask for mediation, or the school may offer mediation. Parents may file a complaint with the state education agency and may request a due process hearing, at which time mediation must be available.

The term inclusion is the most frequently used word to refer to the integration of children with disabilities into regular classrooms. The phrase full inclusion refers to the inclusion of all children with disabilities. The 1975 Education for All Handicapped Children Act called for the integration of children with disabilities into regular classes. Similar to any form of segregation, the isolation of children with disabilities often deprives them of contact with other students and denies them access to equipment found in regular classrooms, such as scientific equipment, audiovisual aids, classroom libraries, and computers. Full inclusion, it is believed, will improve the educational achievement and social development of children with disabilities. Also, it is hoped, bias against children and adults with disabilities decreases because of the interactions of students with disabilities with other students. The integration clause of the Education for All Handicapped Children Act specified that to the maximum extent appropriate, handicapped children, including children in public or private institutions or other care facilities, are educated with children who are not handicapped, and that special classes, separate schooling, or other removal of handicapped children from the regular educational environment occurs only when the nature or severity of the handicap is such that education in regular classes with the use of supplementary aids and services cannot be achieved satisfactorily.

In 1990, advocates of full inclusion received federal support with the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). This historic legislation bans all forms of discrimination against people who are disabled. The ADA played an important role in the 1992 court decision Oberti v. Board of Education of the Borough of Clementon School District, which involved an 8-year-old, Rafael Oberti, classified as educable mentally retarded. U.S. District Court Judge John F. Gerry argued that the ADA requires that people with disabilities be given equal access to services provided by any agency receiving federal money, including public schools. Judge Gerry decided that Oberti could manage in a regular classroom with special aides and a special curriculum. In his decision Judge Gerry wrote, “Inclusion is a right, not a privilege for a select few.”

The 1997 congressional amendments to this legislation, now called the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), emphasized the importance of including children with disabilities in regular classes. In the text of the 1997 amendments, it was claimed that since the passage of the original legislation research, inclusion in regular classes improved the academic performance of children with disabilities. In the words of the amendments,

Over 20 years of research and experience has demonstrated that the education of children with disabilities can be made more effective by … having high expectations for such children and ensuring their access in the general curriculum to the maximum extent possible.

During congressional hearings leading to the passage of the 1997 IDEA amendments there were complaints that appropriate educational services were not being provided for more than half of the children with disabilities in the United States. Also, more than one million of the children with disabilities in the United States were excluded entirely from the public school system and were not educated with their peers. In addition, there were complaints that many disabilities were going undetected.

The inclusion of children with disabilities in regular classrooms created a new challenge for regular teachers. Classroom teachers, according to the legislation, were to be provided with “appropriate special education and related services and aids.” The legislation specified that teachers should receive extra training to help children with disabilities. In the words of the legislation, school districts must provide “high-quality, intensive professional development for all personnel who work with such children in order to ensure that they have the skills and knowledge necessary to enable them to meet developmental goals.” Also, teacher education programs were to give all student teachers training in working with students with disabilities.

In 2005, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) issued its “Guidelines for Inclusion: Ensuring Access to Education for All.” A global organization, UNESCO is particularly concerned with the inclusion of students in education in developing nations. The organization estimates that globally over half a billion persons are disabled and excluded not only from schools but also from fully participating in local economies and political systems. It estimates that 80 percent of the disabled live in developing countries. The Guidelines state, “Today there are an estimated 140 million children who are out of school, a majority being girls and children with disabilities. Among them, 90% live in lower middle-income countries and over 80% of these children are in Africa.”

UNESCO’s supports inclusion as a human right based on Article 26 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights:

Everyone has the right to education. … Education shall be free, at least in the elementary and fundamental stages. Elementary education shall be compulsory. Education shall be directed to the full development of human personality and to the strengthening of respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms. It shall promote understanding, tolerance and friendship among all nations, racial or religious groups, and shall further the activities of the United Nations for the maintenance of peace.

In the context of Article 26 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, UNESCO’s concept of inclusion includes not only students with disabilities but also children from differing cultures and religions. Thus, UNESCO’s definition is:

Inclusion is seen as a process of addressing and responding to the diversity of needs of all learners through increasing participation in learning, cultures and communities, and reducing exclusion within and from education. It involves changes and modifications in content, approaches, structures and strategies, with a common vision which covers all children of the appropriate age range and a conviction that it is the responsibility of the regular system to educate all children.

In other words, UNESCO is actively making inclusion a global education doctrine that includes not only students with disabilities but also all children.

On December 9, 2003, federal regulations, Title I – Improving the Academic Achievement of the Disadvantaged – from the U.S. Department of Education were posted in the Federal Register requiring that children with disabilities be included in the state testing systems under the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001. However, states are allowed to create alternative tests and standards for students with disabilities. Inclusion is one reason given for requiring the assessment of students with the most significant cognitive disabilities to be included in state testing programs. The argument is made that teachers will expect more of students and work harder at teaching students with significant cognitive disabilities if they are included in the state testing system. “Students with disabilities,” the federal regulation states,

accrue positive benefits when they are included in school accountability systems. Educators realize that these students also count, just like all other students; they understand that they need to make sure that these students learn to high levels, just like other students. When students with disabilities are part of the accountability system, educators’ expectations for these students are more likely to increase.

Also, federal regulations indicate a fear that if these students are not included in the state testing programs then school administrators will attempt to raise their school’s test scores by classifying more students as having disabilities. In other words, excluding students with disabilities raises the specter of school administrators cheating by over-enrolling students in these programs. As the federal regulation states: “For example, we know from research that when students with disabilities are allowed to be excluded from school accountability measures, the rates of referral of students for special education increase dramatically.”

The federal regulations included the testimony of an unnamed Massachusetts state official about the benefits of including students with the most significant cognitive disabilities in its assessment. The state official claimed that these students were taught concepts not normally developed in their classes. “Some students with disabilities,” the state official explained, “have never been taught academic skills and concepts, for example, reading, mathematics, science, and social studies, even at very basic levels.” The official asserted his or her belief in inclusion in state testing programs under No Child Left Behind: “Yet all students are capable of learning at a level that engages and challenges them.”

The federal regulation provides an emphatic endorsement of inclusion: Teachers who have incorporated learning standards into their instruction cite unanticipated gains in students’ performance and understanding. Furthermore, some individualized social, communication, motor, and self-help skills can be practiced during activities based on the learning standards. Too often in the past, students with disabilities were excluded from assessments and accountability systems, and the consequence was that they did not receive the academic attention they deserved. Access and exposure to the general curriculum for students with disabilities often did not occur, and there was no system-wide measure to indicate whether or what they were learning. These regulations are designed to ensure that schools are held accountable for the educational progress of students with the most significant cognitive disabilities, just as schools are held accountable for the educational results of all other students with disabilities and students without disabilities.

Unequal educational opportunities continue to plague American schools. Even though the civil rights movement was able to overturn laws requiring school segregation, second-generation segregation continues to be a problem. Differences between school districts in expenditures per student tend to increase the effects of segregation. Many Hispanic, African American, and Native American students attend schools where per-student expenditures are considerably below those of elite suburban and private schools. These reduced expenditures contribute to unequal educational opportunity that, in turn, affects a student’s ability to compete in the labor market.

However, the advances resulting from the struggle for equal educational opportunity highlight the importance of political activity in improving the human condition. In and out of the classroom, teachers assume a vital role in ensuring the future of their students and society. In the areas of race, gender, and children with disabilities, there have been important improvements in education since the nineteenth century. The dynamic of social change requires an active concern about the denial of equality of opportunity and equality of educational opportunity.

American Association of University Women. http://www.aauw.org. This organization plays a major role in protecting women’s rights in education. The reader should check the organization’s annual reports on current issues.

American Council of Education. Gender Equity in Higher Education: 2006. Washington, DC: American Council of Education, 2006. A report on gender differences in enrollment in higher education.

American Federation of Teachers. “Resolution on Inclusion Students with Disabilities.” http://www.aft.org/about/resolutions/1994/inclusion.htm. This resolution describes the concerns of one of the two teachers’ unions about the improper administration of inclusion programs. It also contains a description of the problems that may be encountered by administrative implementation of inclusion programs.

Archibold, Randal. “Negro? Prieto? Moreno? A Question of Identity for Black Mexicans.” The New York Times (October 25, 2014). http://www.nytimes.com/2014/10/26/world/americas/negro-prieto-moreno-a-question-of-identity-for-black-mexicans.html?ref=world&_r=0. This article describes the problem of classifying Mexicans who are descendants of enslaved Africans.

Balfanz, Robert, and Nettie Legters. Locating the Dropout Crisis: Which High Schools Produce the Nation’s Dropouts? Where Are They Located? Who Attends Them? Baltimore, MD: Center for Social Organization of Schools, Johns Hopkins University, 2004. This study shows that a majority of African American and 40 percent of Hispanic students attend high schools where most students do not graduate.

Blad, Evie. “Transgender Youth Protected by Title IX, Updated Guidance Says.” Education Week (April 29, 2014). http://blogs.edweek.org/edweek/rulesforengagement/2014/04/transgender_youth_protected_by_title_ix_updated_guidance_says.html?qs=title+IX. This Education Week blog discusses the broadening of guidelines to include harassment, bullying, and discrimination of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender students.

Carey, Kevin. The Funding Gap 2004: Many States Still Shortchange Low-Income and Minority Students. Washington, DC: Education Trust, 2004. Carey shows disparities in funding based on racial concentrations in school districts.

Commission on Excellence in Special Education. Revitalizing Special Education for Children and Their Families, 2002. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, 2002. This report of George W. Bush’s Commission on Special Education recommends the use of federal funds to support vouchers for students with disabilities.

Feminist Majority Foundation. Education Equality: Threats to Title IX. http://www.femist.org/education/ThreatstoTitleIX.asp (accessed September 7, 2008). This site provides information on the continuing struggle for gender equality in the schools.

Idea ’97 Regulations. http://www.ideapractices.org/law/regulations/regs/SubpartA.php. The federal regulations issued in 1997 that regulate the education of children with disabilities.

Kluger, Richard. Simple Justice. New York: Random House, 1975. Kluger provides a good history of Brown v. Board of Education and the struggle for equality.

Lee, V.E., H.M.T. Marks, and T. Byrd. “Sexism in Single-Sex and Coeducational Secondary School Classrooms.” Sociology of Education, Vol. 67, no. 2 (1994): 92–120. This is an important study of sexism in single-sex classrooms.

Lemann, Nicholas. The Promised Land: The Great Black Migration and How It Changed America. New York: Vintage Books, 1991. A definitive history of African American migration from the South to the urban North.

Lewin, Tamar. “A More Nuanced Look at Men, Women and College.” The New York Times (July 12, 2006): B8. http://www.nytimes.com. This review of the 2006 report by the American Council of Education shows that the gender gap in undergraduate enrollments is greater among students over 25 years old.

Lewin, Tamar “The New Gender Divide: At Colleges, Women Are Leaving Men in the Dust.” The New York Times (July 9, 2006). http://www.nytimes.com. This important newspaper article highlights the growing disparity between female and male attainment in college.

Lopez, Ian F. Haney. White by Law: The Legal Construction of Race. New York: New York University Press, 1996. Legal cases involved in defining the legal meaning of “white” are discussed.

Lopez, Nancy. Hopeful Girls, Troubled Boys: Race and Gender Disparity in Urban Education. New York: Routledge, 2003.

Meier, Kenneth, Joseph Stewart, Jr., and Robert England. Race, Class, and Education: The Politics of Second-Generation Discrimination. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1989. This book studies the politics of second-generation segregation.

Miao, Jing, and Walt Haney. “High School Graduation Rates: Alternative Methods and Implications.” Educational Policy Analysis Archives, Vol. 12, no. 55 (October 15, 2004). Tempe: College of Education, Arizona State University. This study concludes that there is a declining high school graduation rate among black and Hispanic students.

National Center for Education Statistics. “Indicator 9: Children and Youth with Disabilities.” The Condition of Education 2009. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 2009. Provides enrollment statistics for children and youth with disabilities.

National Center for Education Statistics “Indicator 26: Racial/Ethnic Concentration in Public Schools.” The Condition of Education 2009. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 2009. Reports the degree of segregation in U.S. public schools.

National Center for Education Statistics The Condition of Education 2008. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 2008. This excellent annual report on the conditions of schools in the United States is an invaluable source for educational statistics ranging from test scores to school finance.

National Center for Education Statistics “Indicator 8: Students with Disabilities in Regular Classrooms.” The Condition of Education 2008. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 2008. Data on students with disabilities in U.S. public schools are provided in this report.

National Organization for Women Foundation. http://www.nowfoundation.org. The annual reports of NOW’s foundation list current educational issues involving gender equity.

National Organization for Women’s 1966 Statement of Purpose. Adopted at the Organizing Conference in Washington, DC (October 29, 1966). http://www.now.org. This historic document establishes the foundation for the participation of women in the civil rights movement.

Orfield, Gary. Schools More Separate: Consequences of a Decade of Resegregation. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, The Civil Rights Project, 2001. Details of the resegregation of American schools in the last quarter of the twentieth century are presented.

Orfield, Gary The Reconstruction of Southern Education: The Schools and the 1964 Civil Rights Act. New York: Wiley-Interscience, 1969. Orfield presents a study of the desegregation of southern schools following the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

Orfield, Gary, and Chungmei Lee. Racial Transformation and the Changing Nature of Segregation. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, The Civil Rights Project, 2006. The latest report from the Harvard Civil Rights Project on the problem of segregation in American schools.

Philip, John Mollenkopf, Mary C. Waters, and Jennifer Holdaway. Inheriting the City: The Children of Immigrants Come of Age. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2008. A study of immigrant students in New York City.

Richard, Alan. “Researchers: School Segregation Rising in South.” Education Week (September 11, 2002). http://www.edweek.org. This report discusses the rise of school segregation in the South.

Rist, Ray. Desegregated Schools: Appraisals of an American Experiment. New York: Academic Press, 1979. This book provides many examples of second-generation segregation.

Roberts, Sam. “Census Figures Challenge Views of Race and Ethnicity.” The New York Times (January 22, 2010). http://www.nytimes.com. Report on the complexity of identifying race and ethnicity in the 2010 Census report.

Schemo, Diana Jean. “Report Finds Minority Ranks Rise Sharply on Campuses.” The New York Times (September 23, 2002). http://www.nytimes.com. Schemo summarizes the American Council on Education report on increased minority students on college campuses.

Schnaiberg, Lynn. “Chicago Flap Shows Limits of ‘Inclusion,’ Critics Say.” Education Week (October 5, 1994): 1, 12. This article describes parent protest about inclusion in Chicago.

Shelley, Allison. “Brave New World.” Education Week (July 10, 2002). Shelley tells the story of Chris Vogelberger, a student with Down’s syndrome, and his inclusion in regular classes.

The Civil Rights Project. “UCLA Report Finds Changing U.S. Demographics Transform School Segregation Landscape 60 Years After Brown v Board of Education” (May 15, 2014). http://civilrightsproject.ucla.edu/news/press-releases/2014-press-releases/ucla-report-finds-changing-u.s.-demographics-transform-school-segregation-landscape-60-years-after-brown-v-board-of-education/National-report-press-release-draft-3.pdf. Study of school segregation since 1954 showing the increasing segregation of Latinos.

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). Guidelines for Inclusion: Ensuring Access to Education for All. Paris: UNESCO, 2005. These UNESCO guidelines declare inclusion to be a human right under the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

U.S. Census Bureau. “African-Born Population in U.S. Roughly Doubled Every Decade Since 1970, Census Bureau Reports.” http://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2014/cb14–184.html. This report shows the rapid growth in African-born population of the US.

U.S. Census Bureau “Current Population Survey (CPS) – Definitions and Explanations.” http//www.census.gov/population/www/cps/cpsdef.html. A guide to the racial and other terms used in the collection of the national census.

U.S. Census Bureau “Form D-61.” United States Census 2010. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Commerce, 2010. Form used to collect census data including racial information. The form demonstrates the complexity of identifying the race of citizens.

U.S. Census Bureau “Current Population Survey 2005. Annual Social and Economic Supplement.” http://www.census.gov/hhes/www/income/dinctabs.html. Data on relationship between race and income are provided.

U.S. Department of Education. “20th Anniversary of the Americans with Disabilities Act a Cause for Celebration and Rededication to Equal Educational Opportunity for Students with Disabilities (July 26, 2010).” http://www.ed.gov/news/press-releases/20th-anniversary-americans-disabilities-act-cause-celebration-and-rededication-e. Statement commemorating the anniversary of IDEA. http://www.ed.gov/news/press-releases/20th-anniversary-americans-disabilities-act-cause-celebration-and-rededication-e.

U.S. Department of Education Digest of Education Statistics, 2012 (NCES 2014–2015), Chapter 2. http://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp?id=64. This table provides statistics on the percentage of students with various disabilities in public schools.

U.S. Department of Education Office of Special Education and Rehabilitative Services. A Guide to the Individualized Education Program (July 2000). http://www2.ed.gov/parents/needs/speced/iepguide/index.html. Government guidelines from writing an IEP.

U.S. Department of Education “Title I – Improving the Academic Achievement of the Disadvantaged.” Federal Register, Vol. 68, no. 236 (December 9, 2003). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 2003. Title I outlines the regulations requiring students with disabilities to be tested under the requirements of the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001.

U.S. Department of Education “Thirty-five Years of Progress in Educating Children With Disabilities Through IDEA.” http://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/osers/idea35/history/idea-35-history.pdf. This report describes the progress made in implementation of IDEA.

Viadero, Debra. “VA. Hamlet at Forefront of ‘Full Inclusion’ Movement for Disabled.” Education Week (November 18, 1992): 1, 14. This article describes the implementation of a full-inclusion plan in a community in Virginia.

Viadero, Debra “NASBE Endorses ‘Full Inclusion’ of Disabled Students.” Education Week (November 4, 1992): 1, 30. This article discusses the report supporting full inclusion of students with disabilities. The report Winners All: A Call for Inclusive Schools was issued by the National Association for State Boards of Education.

Viadero, Debra “‘Full Inclusion’ of Disabled in Regular Classes Favored.” Education Week (September 30, 1992): 11. A report on the court case Oberti v. Board of Education of the Borough of Clementon School District, which involves full inclusion.

Walsh, Mark. “Judge Finds Bias in Scholarships.” Education Week (February 15, 1989): 1, 20. This article describes the court ruling that found the awarding of scholarships by using test scores to be biased against female students.

Wolf, Carmen, et al. Income, Poverty, and Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2003. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau, August 2004. The authors provide important census material on the relationship between race and income.

Wollenberg, Charles. All Deliberate Speed: Segregation and Exclusion in California Schools, 1855–1975. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1976. A good history of segregation in California. It includes a discussion of the important court decision regarding Mexican Americans, Mendez et al. v. Westminster School District of Orange County, and of the segregation of Asian Americans.