I am not rich.

—Joe Masseria, on trial for burglary in People against Masseria, May 15, 1913

The police declare that both [Umberto] Valenti and [Joe] Masseria were millionaires.

—New York Evening Telegram, August 11, 1922

SUNDAY, APRIL 13, 1913, HOLDING CELL, POLICE STATION HOUSE, MULBERRY STREET, MANHATTAN: JOE MASSERIA'S BURGLARY RING

“What was I to do? Shoot?” said the burglar, in Italian, to his three partners. They were stewing in the holding cell of the Twelfth Precinct Station House in Little Italy, Manhattan.1

“Yes, you should have taken a—” responded one of the men.

“Why, they only found one gun,” the burglar said.

“No, they found two,” corrected the other man.

“No, I know positive he only found one,” the burglar insisted defensively.

The leader of the ring tried to calm everyone down. “We were to get diamonds and we get backhouse,” he lamented, referring to the poor man's toilet. He then sounded a note of unity: “Four we were and four we are.”2

Joe Masseria and his three partners in crime had been arrested that Sunday morning, April 13, 1913, on the charge of the burglary of Simpson's pawnbrokers at 146 Bowery Street in Lower Manhattan. With him in the cell were Pietro “Pete the Bum” Lagatutta and the brothers Salvatore and Giuseppe Ruffino of Brooklyn. None of the “four we are” would flip and give evidence to the police about anyone else in the hope of reducing their charge. They would soon go on trial for first-degree burglary.3

Looking at him in the prison cell that Sunday, no one would have predicted that Joe Masseria would someday become the capo di capi or “boss of bosses” of the Mafia. It would have not been considered much of a title anyway. In the 1910s, the Italian gangs were near the bottom of the underworld. Within a decade, however, Joe Masseria would be one of New York's most powerful gangsters, and the Mafia families were on their way to becoming the dominant crime syndicates in Gotham.

This chapter begins with an overview of the dismal state of the Italian gangs in the 1910s. It looks at the rather sad early “careers” of three gangsters: Joe Masseria, Charles “Lucky” Luciano, and Giuseppe Morello. Next, it looks at how the Prohibition era (1920–1933) helped fuel their ascents and that of the Mafia generally. The chapter then presents three other large-scale factors that accelerated the Mafia's growth beginning in the 1920s. These include: the surge of South Italian immigration to New York, the development of the Mafia franchise system, and the advent of new technologies like the telephone and automobile.

THE HUMBLE BEGINNINGS OF GIUSEPPE “JOE THE BOSS” MASSERIA

Giuseppe Masseria had been looking for a big score since coming to America. Born January 17, 1886, in the southwest province of Agrigento, Sicily, he immigrated to New York City as a teenager in 1902 and lived in the rough-and-tumble Mulberry Bend on the Lower East Side.

A natural leader, Masseria was aggressive, fearless, and physically agile. A stout 5 feet, 4 inches, Masseria had black hair, puffy cheeks, and several gold teeth. Good work in the rackets was sparse for young Italians, however, and he struggled to make it on high-risk, strongarm crimes. He racked up arrests for assault and extortion; in 1909, he was convicted of burglary and given a suspended sentence.4

Masseria had his sights on Simpson's pawnbroking establishment near Little Italy. Simpson's was no low-rent pawnshop. It was a three-story building with a Holmes electric security system and a safe deposit vault holding $300,000 worth of diamonds and other valuables (about $7 million in present dollars).5 Pietro Lagatutta rented an apartment that shared a backyard with Simpson's. During a rainstorm on the night of Saturday, April 12, 1913, the burglars used a ladder to scale a dugout behind the Simpson's building and drilled a hole in the rear brick wall. Once inside, they planned to crack the vault.

Unfortunately for them, a beat cop saw a blanket stuffed in the wall of Simpson's. Early Sunday morning, police on surveillance stopped the men as they tried to leave Lagatutta's apartment. While Masseria was dressed in a brown suit and derby hat, the other men had raincoats with wet brick dust. They were all arrested and charged with burglary.6

MAY 15, 1913, COURT OF SPECIAL SESSIONS, MANHATTAN: THE TRIAL OF MASSERIA

Masseria testified on his own behalf at trial. Although his English was good enough for the judge to dispense with the interpreter, Masseria was out of his element in the staid courtroom. “Before I speak to you and Mr. District Attorney I want to tell something to the judge,” said Masseria, bursting with energy. “Now, you sit perfectly still and just answer questions,” the judge instructed.7

“I am not rich,” Masseria later testified. This was embarrassingly true. Masseria lived with his mother until she passed away, then he moved his wife and children into a room in a tenement owned by his brother-in-law and sister at 217 Forsythe Street on the Lower East Side. Masseria was the barkeep for his sister's saloon across the street.8

The trial went badly. The prosecutor had a lot of physical evidence, including the new technology of a “finger-print” impression of Lagatutta inside Simpson's. Masseria tried to explain his presence at Lagatutta's apartment at 7:00 Sunday morning, testifying that he stopped by looking for help “to work in the saloon on Sunday.” The jury convicted after only ninety minutes of deliberation. The judge sentenced Masseria to the maximum-security prison at Ossining, New York—the infamous Sing Sing—where he would spend the next four-and-a-half years. On January 17, 1916, Masseria reached the age of thirty in prison. He had two felony convictions, three young children, and few prospects in sight.9

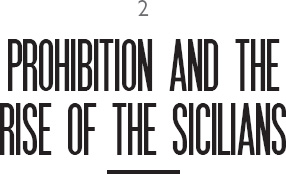

SALVATORE LUCANIA: PETTY CROOK LIVING AT HOME, 1910–1919

Another young Sicilian immigrant was struggling to get by as a petty crook in New York during the 1910s. Born Salvatore Lucania on November 24, 1897, Charles Luciano was the middle child of a family from Lercara Friddi, a depressed mining town southeast of Palermo. His father was among the waves of Sicilian men who left for work in the manufacturing metropolis of New York City, bringing over nine-year-old Salvatore and the rest of the family in 1907. They lived in a tenement on East 10th Street, a polyglot area of Russian Jewish, Southern Italian, and other later-arriving immigrants.10

Recently rediscovered prison reports, which were based in part on interviews with Luciano himself, provide insight on his “formative years.” Luciano's parents were a respectable, working-class married couple with no history of criminality, mental illness, or major alcoholism. Nevertheless, they found themselves with an incorrigible son, who was sent to reform school for truancy and juvenile delinquency. He dropped out of school permanently at the age of fourteen in 1912.11

Charlie then went through jobs like a tour of Manhattan's manufacturing industries. He stuffed dolls in a doll factory, labored alongside his father in a brass factory, pressed dresses in a garment shop, worked in the fish market, and prepared shipments for the Goodman Hat Company. “He admits he did not like to work so never held a job for any length of time,” read a prison report. Luciano would learn how to extract money from such industries through racketeering.12

But for now, he simply wanted to find easier ways to make money. Luciano's psychiatric evaluations found he was an “egocentric, antisocial type,” and “rather a socio-path than a psychopath,” who chose the criminal life. Aptitude tests found him to have “bright intelligence,” and a report noted his “calmness at times of stress” and “reserve and strength.” (Essentially, the exact opposite of his portrayal as a hotheaded buffoon in HBO's Boardwalk Empire). These traits eventually brought him respect in the underworld.13

There was something else: Luciano's coolly indifferent, nihilistic view of life. “He manifests a peasant-like faith in chance and has developed an attitude of nonchalance.”14

This good-time Charlie said he “liked luxury,” spending freely on high-class hotels and nightclubs, platinum jewelry, and beautiful women. Unlike most mafiosi, he never married or had children. At age fourteen, he lost his virginity and caught gonorrhea, the first of seven cases of gonorrhea and two cases of syphilis. Luciano did have common-law relations for six years with a special woman, but they never married because he “couldn't get along with the girl.”15

2–1: Charles Luciano, 1928. (Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration)

Luciano's drooping right eye, caused by a vicious cutting of his face by assailants, reinforced this appearance of indifference. His nickname “Charles Lucky” was a play on his surname and his fortunes. Luciano later admitted to a psychiatrist that he had been arrested dozens of times (including several never made public) but was able “to free himself from most of these charges and because of this was nicknamed Lucky.”16

“Charles Lucky” saw himself as a gambler. Though he would later become a bootlegger and labor racketeer, controlling trucking in the Garment Center, when Luciano was asked about his profession, he usually said “bookmaker” or “gambling.” He would purchase a place in upstate New York, and he spent summer months at the Saratoga Springs racetrack betting on the ponies. To avoid the fate of Al Capone, Luciano's lawyers filed federal income tax returns in which he listed “miscellaneous” income. “I'm a gambler. That's my profession,” he brashly told IRS examiners. Like any good gambler, Luciano was at ease taking huge, calculated risks in the underworld.17

These traits would come in handy in the years to come. But that was all in the distant future. Through the late 1910s, Salvatore Lucania was just another petty crook with a record. At age twenty-two, he was still living at home with his parents on East 10th Street.18

THE MORELLO FAMILY IN SHAMBLES, 1910–1919

Meanwhile, the small Mafia of New York City was in shambles as well. The first substantial Sicilian cosca (or clan) in New York was led by Giuseppe “The Clutch Hand” Morello, his brother-in-law Ignazio “The Wolf” Lupo, and Morello's three half-brothers Ciro, Nick, and Vincenzo Terranova. The Morello Family barely survived on petty extortion, horse thievery, and insurance fraud. A few of its leaders graduated to early racketeering by using threats and extortion to control shipping and access to the wholesale vegetable markets in early 1900s.19

Then, the Morellos made a disastrous mistake: in 1909, they got caught counterfeiting US currency. Disastrous because, while the Morellos might be able to bribe local officials, counterfeiting fell under the federal jurisdiction of the US Secret Service. In 1910, the Morello Family, which never totaled more than 110 men, including its associates, saw 45 of its men convicted and sentenced to lengthy prison terms in the Atlanta Federal Penitentiary. All their legal appeals failed, and their convictions were affirmed.20

The hardest fall was Giuseppe Morello. Besides being the head of his own family, Morello held the title of capo di capi or “boss of bosses” of the American Mafia. After being sent to prison, Morello lost that title to Salvatore D'Aquila, a former confidence man and gang leader in East Harlem. Morello's underboss Ignazio Lupo went away with him, too. With their leadership decimated, the remnants of the Morello Family came under attack from a Brooklyn-based Camorra gang (whose members were from the Naples area of Italy), which began trying to kill off the Morello's remaining men and poach their territories.21

The Morello Family prisoners grew increasingly desperate as their sentences wore on at the Atlanta Federal Penitentiary. Mislead by their ability to pay off local police, they convinced themselves that influence might spring them from federal prison. They banked their hopes on an Italian politician from the Lower East Side who apparently promised them that “an attempt will be made to pass a law in Congress” to help them. When that fizzled out, they next retained a lawyer who claimed he was “cousin of the President's Secretary,” and put $5,000 in deposit “for the lawyer after Morello is released.” It did not work. Giuseppe Morello wasted away in the Atlanta federal prison for a full decade, until he was finally released in 1920, a gaunt and penniless man.22

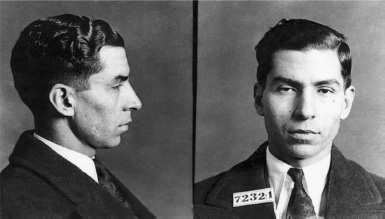

PROHIBITION NEW YORK, 1920–1933

Then came Prohibition. At 12:01 a.m., Saturday, January 17, 1920, the Eighteenth Amendment to the Constitution went into effect, prohibiting “the manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors within…the United States.” The new Prohibition Unit was given the task of enforcing the federal law, with only fifteen hundred enforcement agents initially for the entire United States. “Detailed plans have been made to carry out the law in cities, such as New York,” the New York Times reported. “Fifty men are said to have been assigned to New York.”23

New Yorkers rejected Prohibition in massive numbers by continuing to buy beer and booze. Law enforcement was quickly overwhelmed. The federal court in Manhattan held “cafeteria court” hearings where two hundred defendants at a time were brought before a judge to plead guilty and pay fines averaging $25. Responding to the public backlash, the New York State Legislature repealed its state “dry” law in June 1923. Gotham thus became the symbolic capital of drinking in America. As a Prohibition report said, “New York is considered the most conspicuous example of a wet city.”24

Prohibition agents, and some local police, arbitrarily enforced the federal law just enough to keep the liquor trade underground.25 By the late 1920s, the NYPD was still making over eight thousand arrests a year for violation of the National Prohibition Act. Manhattan speakeasies were especially vulnerable to shakedowns from corrupt cops. A report on Prohibition noted the NYPD's peculiar practice of wholesale arrests of “bartenders in speak-easies and waiters in night clubs, cabarets, and so-called restaurants.”26 It was in this environment that gangsters thrived.

2–2: Deputy police commissioner and agents dump illegal beer during Prohibition, 1921. (Courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, New York World-Telegram and Sun Newspaper Photograph Collection)

MOONSHINERS AND BASEMENT BREWERS

Moonshining and basement brewing was a phenomenon common in immigrant neighborhoods. “I think that about twenty minutes after Prohibition started, my father made a deal with the tinsmith to make him a still,” recalled Tom Geraghty, who grew up in Hell's Kitchen.27 In the South Village, Italian immigrants had long produced homemade wines. Now that it became a premium product, Italian grocers and barbershops sold it out the back door. When mafiosi started converting their basements into distilleries, they looked no different than the innumerable other makeshift stills throughout Italian neighborhoods.28

Over time, bootleggers built large and sophisticated brewing operations. Gangsters learned that they could increase profits by producing quality beer and achieving economics of scale. “I set out to make a superior product,” said Roger Touhy, a Chicago bootlegger who sparred with Al Capone. “At peak production, we had ten fermenting plants, each one a small brewery in itself.”29 The Irish gangsters William “Big Bill” Dwyer and Owney “The Killer” Madden operated secret breweries in buildings on the West Side of Manhattan.30

The Italian gangs were an emerging force in bootlegging during Prohibition. A study of New York's top bootleggers in the late 1920s found that about 50 percent were Jewish, 25 percent were Irish, and 25 percent were Italians. Most were young and ambitious. They scrambled to make it in the cut-throat world of bootlegging.31 In Williamsburg, Brooklyn, future mob boss Joe Bonanno and his relative Gaspar DiGregorio started out with a basement distillery. They had a tunnel to a garage where they loaded their booze onto delivery trucks. Bonanno later went to work for a major bootlegger named Salvatore Maranzano, a Sicilian mafioso who like Bonanno came from Castellammare del Gulfo (“Castle by the Sea”) in northwestern Sicily. Barely in his twenties, Bonanno was an overseer of Maranzano's huge brewery operations in upstate New York.32

Gangsters made money in related businesses, too. Mafioso Nicola Gentile sold raw materials to bootleggers. Gentile conspired with Italian barbershops to divert their licensed supplies of alcohol meant for perfumes. He later ran a general store to supply “bootleggers with corn sugar for alcohol distillation and the jars and tin for the contraband of alcohol.”33

RUM RUNNERS

“Rum runners” smuggled name-brand liquors from foreign countries into America. While bathtub gin was (usually) drinkable, Manhattan's connoisseurs started clamoring for the finest brand liquors from Europe and the Caribbean. Gangsters circulated “flyers and price lists with recognizable brands—Johnny Walker scotch, Martell cognac, Booth's gin, Bacardi rum, and Veuve Cliquot champagne—catering to customers who refused to settle for anything else,” explains historian Michael Lerner.34

Rum running involved sophisticated smuggling operations. Rum runners would purchase crates of liquor from foreign ports like London then travel across the ocean, stopping just outside a three-mile perimeter of the East Coast (the United States Coast Guard agreed not to search British ships outside three miles). Speed boats then smuggled the crates to clandestine landing points on Long Island or the New Jersey shore. There, the crates would be loaded onto waiting trucks. So many boats were anchored off the coast that it came to be known as “Rum Row.” Although Jewish and Irish gangsters had the biggest rum-running operations, there were major Italian smugglers, too.35

FRANK COSTELLO, BUSINESSMAN SMUGGLER

The leading Italian rum runner was Frank Costello. Born Francesco Castiglia in a mountain village in Calabria, Italy, he grew up in a ghetto in Italian East Harlem. “It is important, very important, to put in evidence the education received by Frank in the streets of 108th and 109th,” said a lifelong friend. “There is Frank, a very intelligent boy, whose aim was to arrive higher, to get revenge.” He took on the Irish surname of Costello to try to gain more respect. But like Joe Masseria and Salvatore Lucania, he struggled to make it on petty crimes. In 1915, the newly-wedded Costello was sentenced to a year in prison for illegal possession of a revolver.36

2–3: Frank Costello, 1915. (Courtesy of the New York Police Department)

Then came Prohibition. Costello learned that he was very good at bootlegging and rum running. He soon opened a “real estate” front office at 405 Lexington Avenue, from which he managed sophisticated smuggling operations with employees responsible for police payoffs, logistics, and distribution. He did business with such luminaries as Arnold Rothstein, the Jewish gangster, and Samuel Bronfman, the Canadian owner of the Seagram's liquor conglomerate. As we will see, Costello gained additional street protection under a new Mafia family.37

In 1926, Frank Costello was indicted along with sixty other defendants of a conspiracy to smuggle liquor from Newfoundland, Canada, in boats to Rum Row off the coast of New York. Among those indicted were Irish gangster William “Big Bill” Dwyer and thirteen sailors of the United States Coast Guard. While William Dwyer was convicted of the conspiracy at trial, a hung jury could not reach a verdict on Frank Costello. Observers believed that the involvement of Coast Guard sailors turned the case into something of a referendum on Prohibition.38

Frank Costello later admitted to the New York State Liquor Authority (NYSLA) that he had, in fact, imported foreign whiskey during Prohibition:

NYSLA: What years were you engaged in bootlegging during prohibition?

Costello: From 1923 to 1926.

…

NYSLA: You brought whisky into the United States?

Costello: That is right.

NYSLA: From places outside the country?

Costello: That is right.39

Costello admitted making at least $305,000 during Prohibition (about $5.2 million in 2013 dollars). He invested his bootlegging profits in slot machines and real estate, and he became a powerbroker in Gotham, finally getting the respect he had so badly wanted.40

LIQUOR DISTRIBUTION

The most dangerous part of bootlegging was not making beer, or even smuggling in foreign liquor, but distributing it without getting robbed or killed. Much of the violence associated with Prohibition was due to truck hijackings and territorial disputes.

Bootleggers had to move high-premium, illegal goods on back roads and through dark alleys. Liquor trucks became prime targets for hijackers. “Four armed ‘hijackers’ yesterday morning forced four truckmen waist deep into the [water canal], and then sped off with two trucks containing 320 cases of whisky, valued at about $30,000,” reported a typical news story from August 1924.41 “A common occurrence was the hijacking of delivery trucks by rival bootlegging groups,” recounted Joe Bonanno. To protect Maranzano's operations, Bonanno began carrying a pistol and hunting down stolen liquor trucks.42

Rival bootleggers fought fiercely over territories around the city as well. Bootleggers would muscle in on neighborhoods and require all the speakeasies to buy booze only from them. “There were guys going around selling beer, and you had to buy it. You just couldn't switch outfits. They may blow you away,” explained John Morahan, who ran speakeasies in Hell's Kitchen. “Owney Madden's beer would come and the guy would say, ‘You take this beer,’ and you didn't have much choice.”43 Arthur Flegenheimer (a.k.a. Dutch Schultz) had fleets of trucks shipping beer from the Bronx down to areas of Harlem he had taken over. He did battle with Jack “Legs” Diamond and his lieutenant Benjamin “Bugsy” Siegel over beer territories. A neighborhood study of the South Village found that while alcohol makers were plentiful during Prohibition, “selling liquor was still a rough proposition” and the “deliveries were a dangerous business.”44

Since their product was illegal, bootleggers could not resolve their disputes by calling the police or bringing a civil suit in court. This added up to an extremely dangerous business: roughly one thousand bootleggers would be killed on the streets of New York City during Prohibition. “The scramble for bootlegging revenue was far more vicious and complex in New York than in any other American city,” concluded historian Humbert Nelli.45 It was within this violent context of Prohibition that many mafiosi made their names.

THE MAKING OF “JOE THE BOSS” DURING PROHIBITION

Joe Masseria had perhaps the most dramatic reversal of fortune during Prohibition.46 When Masseria got out of Sing Sing prison a couple years before Prohibition, he went back to his sister's saloon on Forsythe Street. Masseria was in the right place at the right time: he was working at the Forsythe Street saloon just before Prohibition went into effect. The saloon was located near the Curb Exchange, an underworld marketplace for illicit alcohol wholesaling on the Lower East Side. Masseria's traits of aggressiveness, fearlessness, and persistence found an outlet as a leader of bootleggers in Prohibition New York. Masseria and his men could assure that shipments of whiskey and other spirits made it through to the thirsty residents of Gotham. His underworld reputation grew amid wild shootouts in 1922.47

MONDAY EVENING, MAY 8, 1922, GRAND STREET, MANHATTAN: THE STREET SHOOTOUT

Around 5:45 p.m. on Monday, May 8, 1922, three well-dressed Italian men were milling in front of a cheese dealer's shop on Grand Street in Little Italy, a block east of the headquarters of the New York City Police. The sidewalks were bustling with people returning from work on the Lower East Side. Joe Masseria and his partner were among those walking up Grand Street. Spotting Masseria, the three men pulled out semiautomatic handguns and fired at their targets.48

With bullets flying at him, Masseria grabbed his .32 caliber Colt pistol and returned fire. Pandemonium ensued as sixty bullets crisscrossed the air. Masseria stood firm on the street, pushing back his would-be killers with his gunfire. As the gunmen ran off, Masseria realized police were now on the scene. Masseria tossed his Colt and tried to disappear into Little Italy, but he was apprehended. Even though five innocent passersby had been shot, Joe Masseria escaped unscathed. Masseria had a gun permit, and there was no proof he shot any pedestrians: steel bullets were found in the wounded, while his gun was loaded with lead bullets.49

TUESDAY AFTERNOON, AUGUST 8, 1922, SECOND AVENUE, MANHATTAN: DUCKING BULLETS

Joe Masseria's rivals were still lurking. On Tuesday, August 8, 1922, a Hudson Touring car dropped off two men at a restaurant across the street from Masseria's brownstone at 80 Second Avenue. At 2:00 p.m., they saw Masseria leave his front stoop and walk north on the sidewalk.

This time, Masseria was unarmed and defenseless. Spotting the gunmen, he made a dash for his home, but they cornered him on the sidewalk. As Masseria dodged and weaved at point-blank range, “four bullets passed through his straw hat and two passed through his coat” yet none struck his head or torso. The police found a stunned Masseria “sitting on the edge of his bed, shot-punctured hat still on.” Newspapers reported how Masseria's “astonishing agility in ducking bullets from automatics saved his life.”50

These shootouts enhanced Masseria's standing in the underworld. But he had enough near-death experiences. As an insurance policy, he built an armored sedan with steel plates and inch-thick windows. He would later have a penthouse on the Upper West Side, too. Within a decade, he would go from staring at grey prison walls in Ossining, New York, to a view of Manhattan's Central Park.51

2–4: Giuseppe “Joe the Boss” Masseria, ca. 1922. (Courtesy of the New York Police Department)

A NEW MOB: THE MASSERIA FAMILY

Giuseppe “Joe the Boss” Masseria's real innovation was creating a mob meritocracy in his new Masseria Family. Rivals such as the Castellammarese clan of Brooklyn limited their membership to men who came from the town of Castellammare del Golfo on the northwestern coast of Sicily. By contrast, Masseria did not particularly care if his men were from his village or were even Sicilians. Rather, Joe the Boss recruited the best bootleggers and racketeers he could find. Masseria was aided by his consigliere (counselor) Giuseppe Morello, the former capo di capi or “boss of bosses,” who had been released in 1920 after a decade in Atlanta federal prison. Joe the Boss benefitted from Morello's deep experience and connections. The remnants of the old Morello Family were reconstituted as part of the Masseria Family. Masseria also recruited young new talent like Charles Luciano, who proved himself to be a savvy and cool-headed bootlegger on the Lower East Side.52

Along with able Sicilians like Morello and Luciano, Masseria welcomed into his ranks Neapolitans like Vito Genovese and Joe Adonis; Calabrians (from mainland Italy's southernmost province) such as Frank Costello and Frankie Uale; and American-born men like Anthony “Little Augie Pisano” Carfano. Although Charles Luciano is often said to have “Americanized” the Mafia, the seeds were actually planted by his boss Joe Masseria.53

By the late 1920s, the Masseria Family became a thriving, multifaceted crime syndicate. By swallowing or forcing out competitors, it became the “A & P of bootleggers” in New York. And the Masseria Family was not limited to bootlegging. Masseria's broad confederation held interests in everything from the Italian numbers lottery to the Brooklyn waterfront labor-union locals taken over by mobsters Vincent Mangano and Albert Anastasia (see chapter 1). New York police detectives identified “Joe the Boss” as the gangster who was “the biggest of ’em all.”54

THE END OF PROHIBITION

Prohibition officially ended with ratification of the Twenty-First Amendment on December 5, 1933. It was a major blow to bootleggers. “We made $400,000 in one year, and we thought we had something going on forever,” said an Irish bootlegger. “But when Prohibition ended, that was the end of the empire. We had to go to work and find a way to make a living.”55

The thirteen-year boom of Prohibition masked longer-term trends among the gangs. The Prohibition era would be the swan song for the Irish gangsters, the high point for the Jewish syndicates, and the coming-out party for the Italian Mafia. The following sections examine other trends fueling the rise of the modern Mafia.

TRENDS IN THE 1920s: ITALIAN IMMIGRATION, MAFIA FRANCHISES, AND NEW TECHNOLOGIES

Prohibition was not the only factor behind the ascent of the Cosa Nostra. Throughout the 1920s, others forces were having transformative effects on the New York underworld. These included south Italian immigration to New York, Mafia family franchising, and new technologies like the telephone and automobile.

DEMOGRAPHY AS DESTINY: IMMIGRATION TO NEW YORK CITY

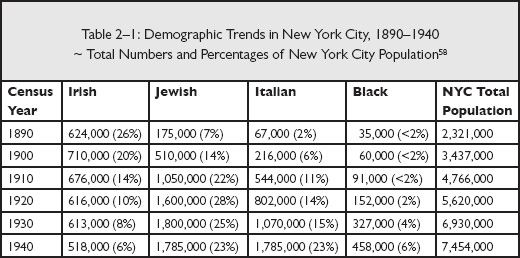

“Demography is destiny,” is a truism of population experts.56 In the early twentieth century, New York City was not so much a giant melting pot as a series of overlapping, immigrant enclaves. In 1910, 41 percent of its residents had been born outside America. While Germans and Irish were the largest immigrant groups in the 1800s, Jews and Italians were the largest groups by the early 1900s. “Within the brief span of less than a generation the ethnic composition of the metropolis altered radically,” explains demographer Ira Rosenwaike. “Persons of Jewish and Italian background had become numerically superior to those of Irish and German descent.”57

In chapter 4 “The Racketeer Cometh” we will see how these demographic trends bolstered the Mafia's labor racketeering. Now, let us look at their social effects on the underworld.

THE SOUTH ITALIAN COLONIAE IN NEW YORK CITY

South Italians especially favored living among fellow paesani. “No other nationality in New York City is so given over to aggregation as the Italians,” observed a writer. Settlement patterns bear out this observation. Gotham was home to large-scale Italian enclaves. The two largest were Italian East Harlem and the Little Italy along Mulberry Street; each was home to about 110,000 Italians. There were also major settlements in the South Village (70,000 Italians) below West 4th Street in Manhattan; in Belmont (35,000 Italians) in central Bronx; on the northern tip of Staten Island (15,000 Italians); and in Williamsburg (40,000 Italians), Bushwick (30,000 Italians), and Red Hook (20,000 Italians) in Brooklyn.59

These were intensely insular, family-centric enclaves. “Our Italian neighborhood was a ghetto. Italian was the spoken language. People built this wall around them to keep the outside world from coming in,” said Jerry Della Femina.60 Italians from the same regions, and even same villages, flocked to the same streets. “Most people from Sicily settled on Elizabeth Street, the people from Mott Street were from mixed cities in Italy, and the people from Mulberry Street were mostly Neapolitans,” recounted a man who grew up in Little Italy.61 Italians married fellow Italians, too. As late as 1920, only 6 percent of south Italians married outside their national origin, rarer than every major immigrant group except Jews.62

THE CORNER WISEGUY AND THE CONNECTED UNCLE

Only a tiny fraction of the residents of these neighborhoods were ever involved with the mob, and many more resented the gangsters. At the Mafia's height, it constituted less than one-half of one percent of New York's Italian population. Nevertheless, the creation of south Italian enclaves around New York indirectly facilitated the emergence of the Cosa Nostra.63

Mafiosi exploited the insularity of these enclaves. South Italians placed a strong primacy on the Italian home and had a deep mistrust of government outsiders. The Mafia played on these cultural traditions. Robert Orsi, the author of an award-winning study of Italian East Harlem, explains the mythology he found: “The racketeers, in the community's mythical restatement of their identity, were the enforcers of the values of the domus [the Italian home],” Orsi explained. “Of course, no one talked about what these men might have done outside the community.”64

The mob relied on social pressure and intimidation, too. “We never asked what they did for a living,” said Clara Ferrara, a resident of East Harlem. “We never knew what Joey Rao did. His wife was a lovely woman.”65 It was hard for outsiders to penetrate the wall of silence. “The coroner's office in New York found itself handicapped whenever we had a case involving members of the Mafia,” said the chief coroner. “Respectable and hard-working Italians, some of whom I knew personally, would become evasive or refuse to answer questions.”66

Wiseguys were an everyday presence in many neighborhoods. The unofficial headquarters of the early Mafia was East 107th Street in Harlem. “The tenements gave the block the appearance of a walled medieval town somehow replanted in New York City,” said Salvatore Mondello, who grew up along 107th Street.67 Goodfellas gravitated there for decades. “They used to hang on the corner. There was the Artichoke King, Rao, Joe Stutz, Joe Stretch,” said Pete Pascale of East Harlem. “They think nothin’ of breakin’ your legs.”68

Ronald Goldstock, former director of the New York State Organized Crime Task Force, has pointed out that these Little Italies were recruiting grounds for young members.69 “When you were brought up in the neighborhood, East Harlem in New York City, you always looked up to the wiseguys,” said Vincent “Fish” Cafaro.70 “In Italian neighborhoods, priests and gangsters were held in virtually the same esteem,” echoed Tony Napoli. “Both were loved and feared, and most of all, respected.”71

Kinship ties further drew young men into a “Mafia family.” When FBI agent Joseph Pistone infiltrated the Bonanno Family, he found there was often “some type of family bond, real family, not Mafia family, a father, an uncle, a cousin,” between them.72 Anthony “Gaspipe” Casso was influenced to join the mob by his (lowercase g) godfather Sally Callinbrano, whom young Anthony saw as “a class act” and a “man of respect.”73 Vincent “Fat Vinnie” Teresa was drawn to his mobster uncle Dominick Teresa who “seemed to have everything.”74

MAFIA FRANCHISING: WHY THE COSA NOSTRA WAS LIKE A BURGER FRANCHISE

The Sicilian mafiosi who settled in Gotham brought with them the organizational structure of the cosche or “clans.” In New York, these became known as the Mafia families.75 Mafia families have been inaccurately compared to a traditional corporation, with managers and employees.76

Rather, the Mafia families most closely resembled franchise companies.77 Franchise companies (that is, burger chains and hotels) allow the use of their trademark by franchisees in exchange for a fee or percent of profits. The franchise company controls minimum standards, guarantees exclusive territories, and arbitrates disputes among franchisees. Franchises are economically efficient because they let the franchisees reap the benefits of a trademark, while the franchisees put up their own capital and know-how to operate on a daily basis.78

Similarly, the Mafia families, rather than paying salaries, simply allowed its members to operate under their names to make money in the underworld. Of course, the Cosa Nostra did not produce any (legal) goods or services, and it was a parasitic enterprise in general. Nonetheless, as the Mafia families expanded in the 1920s, they took on the characteristics of franchise companies.

MAFIA FRANCHISES: THE MAFIA TRADEMARK AND FRANCHISE FEE

Like a franchise company, the New York Mafia developed a valuable “trademark” in the underworld. The Cosa Nostra developed a reputation for reliability, for protection from police and other criminals, and for its capacity for violence.79

The Mafia was known for its ability to offer reliable immunity from local cops. “You had to be allied with somebody like Paulie [Vario] to keep the cops off your back,” believed Henry Hill, an associate of the Lucchese Family. “Wiseguys like Paulie have been paying off the cops for so many years,” explained Hill. “They developed a trust, the crooked cops and the wiseguys.”80 The Mafia became an elite slice of the underworld. When NYPD detective Frank Serpico joined the plainclothes division, he was bluntly told by a fellow officer that while he could arrest black and Puerto Rican criminals, “the Italians, of course, are different. They're on top, they run the show, and they're very reliable, and they can do whatever they want.”81

The Cosa Nostra's underworld reputation was so ferocious that it shielded its members from other crooks. “That's what the FBI can never understand—what Paulie and the organization offer is protection for the kinds of guys who can't go to the cops. They're like the police department for wiseguys,” described Hill. “The only way to guarantee that I'm not going to get ripped off by anybody is to be established with a member, like Paulie.”82 Mob connections could shield non-mobsters, too. “When a businessman is ‘with’ someone, it means he has a godfather, a gladiator who will protect him,” explained Michael Franzese, a prominent ex-mafioso. “That status made him ‘hands off’ to anyone on the street.” The Mafia's preeminent reputation in the underworld was such that it often served as a kind of master arbiter of disputes among other criminals well into the 1970s.83

Ultimately, the Mafia's “brand” was based on its reputation for extreme violence. The scholar Diego Gambetta noted how many mafiosi demonstrated “the ability to use violence” early in their careers to enhance their reputations.84 New York's mob bosses commanded authority based on “a reputation for savagery and a history of settling disputes by shedding blood,” confirms undercover FBI agent Joseph Pistone.85

The Mafia's reputation for violence was so intimidating, that it only had to resort to actual violence sparingly.86 As an FBI informant stated, “a ‘button guy’ received a lot of respect in the neighborhood and was able to use this position to obtain money without getting himself involved in a lot of problems.”87 When Jimmy Fratianno became a “made man,” the mafioso John Roselli explained its reputational benefits: “The fact that you're a member gives you an edge. You can go into various businesses and people will deal with you because of what you represent,” said Roselli. “Nobody fucks with you. We're nationwide…. And that means you can make a pretty good living if you hustle,” counseled the veteran wiseguy.88

The Mafia trademark was valuable enough that there was even some “licensing” and “passing off” of the mark in the underworld. Trademark owners sometimes license their mark to nonaffiliated companies (for example, “[trademark] Diet™-Approved” for food companies). In Manhattan, an Irish gang named “the Westies” entered into a virtual licensing agreement with the Gambino Family. As a federal court explained, the Gambino Family “permitted the Westies to use the Gambino name and reputation in connection with their own illicit business,” and in exchange “the Westies paid the Gambino Family ten percent of the proceeds from various illegal activities.”89 Others occasionally tried to “pass off” the mob's trademark by pretending to be affiliated. “Because of my ethnic background, they thought I was mob-connected and it worked to my advantage. It gave me some leverage to keep bettors in line,” said Anthony Serritella, a Chicago bookie. “I really wasn't connected, but never admitted or denied it.”90

In exchange for operating under a Mafia family, the members paid something resembling a franchise fee and percentage of the profits. Joseph Valachi testified before Congress that each of the five-hundred-odd soldiers in the Genovese Family of which he was a member paid $25 monthly “dues” (about $2,300 annually for each soldier). In the mid-1950s, an Anastasia Family underboss named Frank Scalise was selling mob memberships for $40,000—an express franchise fee. Soldiers were also expected to split some of their profits with their caporegimes (captains) who in turn sent some up to the bosses of the family. “Usually the split is half with your captain,” explained FBI agent Joseph Pistone, who infiltrated the Bonanno Family. “The captain in turn has to kick in, say, ten percent upstairs, to the boss.”91

MAFIA FRANCHISES: TERRITORIAL RIGHTS

Franchise companies often guarantee each franchisee an exclusive territory and prohibit encroachments by their other franchisees (for example, no two coffee shops of the same trademark may open on the same block).92 Similarly, the Cosa Nostra upheld territorial rights for wiseguys.

The Mafia's recognition of territorial rights can be traced all the way back to Sicily. An investigative report from Sicily in the 1890s stated:

Among the canons of the mafia there is one regarding the respect for the territorial jurisdictions of other [cosche]. The infraction of this canon constitutes a personal insult. Hence the encroachments…were perceived by the Siino family as an atrocious personal insult.93

This carried over to New York, albeit in a narrower form. Gotham was too dense to grant exclusive rights to all criminal activities in a neighborhood. In the 1920s, East Harlem was divided up between the Masseria Family and the Reina Family. Later, the New York Mafia protected rights to specific rackets. For example, the Lucchese Family controlled shipping at Kennedy Airport, and different families controlled specific factories in the garment district.94

Soldiers were conversely limited by the territorial rights of other members. The Profaci Family had to suppress a dissident crew lead by the brothers Larry Gallo, Joseph “Crazy Joe” Gallo, and Albert “Kid Blast” Gallo. An FBI informant reported that the Gallo brothers believed that once they were “made” they “would come into sudden wealth.” They grew angry when they discovered the rackets “were already under the control of someone else, and the GALLOS were not allowed to move in on anyone else's operation.”95

MAFIA FRANCHISES: MAINTAINING STANDARDS AND ARBITRATING DISPUTES

To preserve the trademark, franchise companies retain the right to enforce standards or step in when a franchisee is harming the brand (for example, running a shoddy motel under their trademark). Similarly, the Mafia families had the authority to maintain rules to protect the organization and its trademark. Among the most serious rules were that a member could not betray secrets of the Cosa Nostra, he could not physically attack another member, and he could not “fool around…with another amico nostra's [made man's] wife.”96 Although the Mafia talked about these rules in terms of “honor,” they also served the business rationale of protecting the organization. “In New York we step all over each other. What I mean is there is a lot of animosity among the soldiers,” Joe Valachi explained. “So you can see why it is that they are strict about the no-hands rule.”97 The Mafia also sought to protect the reputation of its “brand.” Publicly, at least, the Mafia disavowed any involvement with prostitution, pornography, and drugs (much more on that later), which were viewed negatively by the public.98

Like mainstream franchises, the Mafia even had something resembling arbitration panels to resolve disputes among its members. In his memoirs on the 1920s, mafioso Nicola Gentile describes a “council” in which bosses from different Mafia families met to hear charges of wrongdoing and resolve disputes.99 Later, the Cosa Nostra created “the Commission” as a forum to resolve major disputes. As Joe Bonanno explained, “The Commission, as an agent of harmony, could arbitrate disputes brought before it.”100 In chapter 3 we will look at how the Commission came into being in 1931.

THE NEW TECHNOLOGIES OF TELEPHONES, AUTOMOBILES, AND PLANES

New technologies have been described as waves that roll through society. At the same time that new technologies were changing New York, they were transforming organized crime as well.101

In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, New York gangsters had relatively limited reach. Groups like the “Eighteen Street Gang” or the “Bottle Alley Gang” rarely controlled more than a couple blocks.102 They were hampered by unreliable communication and transportation. The early Mafia families actually communicated by mail. Men of Honor would even carry with them “letters of recommendation” from their mob bosses when they traveled to new cities.103 Communicating through hard documents proved risky: in the early 1900s, the United States Secret Service seized letters of members of the Morello Family and used the letters to build cases against them.104

The advent of the modern telephone system gave organized crime a valuable new tool to communicate efficiently across regions and the United States. As service grew, New Yorkers developed the habit of using the telephone regularly on massive levels from the 1910s onward.105 Professional criminals were relatively free to use phones in this time, too. The Federal Communications Act of 1934 prohibited the interception and disclosure of wire communications, rendering any wiretapped phone conversations inadmissible in federal court. This remained the law until 1968.106 Although local law enforcement was not so restricted, it was often compromised by corruption from investigating organized crime. From the 1920s through the mid-1950s, there was something of a golden era for gangsters to use phones. Los Angeles goodfella Jimmy Fratianno used pay phones to have conversations about loansharking and casino operations through the 1960s. Asked why he did not take more precautions, Fratianno, referring to his 1970s conviction, explained: “Well, later years we did, but like see, I was the first person that ever went to jail on a wiretap in Los Angeles.”107

The telephone expanded the reach and efficiency of organized crime starting in the 1920s. New York mafioso Frank Costello regularly phoned his partner Phillip “Dandy Phil” Kastel in New Orleans to coordinate their joint gambling operations. During the 1940s, state police discovered that mafioso Joseph Barbara was calling gangsters throughout the East Coast (he kept his conversations short and veiled to avoid incrimination). Despite the growing risks, the efficiencies from telephones were so great that mafiosi were still communicating over pay phones (using coded words) well into the 1970s. As Judge Richard Posner points out, phones are so efficient and attractive that they are still used by many gangsters despite the risks.108

Mass-produced automobiles opened up new territories and criminal enterprises as well. By 1927, a majority of America households owned a car.109 Gangsters likewise started using automobiles for criminal activities. Joe Valachi got his start as a “wheelman” for burglaries, driving his careening Packard car through the streets after heists.110 Bootlegging operations depended on fleets of trucks. The Mafia began relying on cars to smuggle narcotics, too.111

These new technologies enabled gangsters to forge cross-country links during Prohibition. As historian Mark Haller describes, “Bootleggers east of the Mississippi were wintering in Miami and occasionally vacationing in Hot Springs, Arkansas,” they met “in Nova Scotia or Havana, to which they traveled to look after their import interests,” and those with joint ventures were in “continual contact by telephone” to coordinate activities.112 Las Vegas's casino industry, in which mobsters conducted skimming operations, would not have developed without modern cars and airplanes.113

TECHNOLOGY AND GAMBLING: THE NUMBERS LOTTERY AND SPORTS BOOKMAKING

Technology had its most direct impact on illegal gambling operations. Although gambling had been around forever, it was boosted by new communications in the 1920s. The Mafia families specialized in two different forms of gambling: the numbers lottery and sports bookmaking.

During the 1920s, the numbers lottery took off in New York City. Historians have shown that New York's illegal lotteries nearly disappeared in the early 1900s, following revelations that paper drawings were being fixed by their operators. In the early 1920s, African-American gangsters in black Harlem built a new numbers lottery based on an unimpeachable public source of randomly generated numbers: the New York Clearing House. Each morning at 10:00 a.m., as the clearings numbers were announced in Lower Manhattan, numbers runners would telephone the winning digits throughout Gotham. “Once the Clearing House numbers became known in Harlem, the game spread like wildfire,” describes a history of the numbers lottery.114

Numbers lotteries were highly territorial in areas of New York City. Numbers lotteries required “banks” and numbers “shops” (such as liquor stores that sold numbers under the counter) in neighborhoods to enable a large customer base of numbers purchasers. For banks and numbers shops to operate, pay-offs to the police and protection from others were required.115 As a result, the Mafia held interests in numbers lotteries around New York. In the 1930s, the lucrative Harlem numbers lottery was taken over by members of the Luciano family, and it was passed down for decades from Michael “Trigger Mike” Coppola to Anthony “Fat Tony” Salerno.116 Likewise, Joe Bonanno recalled how when he became a boss in central Brooklyn, he “also inherited the ‘rights’ to the neighborhood lottery.”117 Later, his son Bill Bonanno described how “a member could run numbers within a designated four-block area of the neighborhood,” and “if someone else interfered by encroaching on his territory,” the family would intervene.118

Bookmaking was revolutionized by wire services, telephones, radio, and later television. Bookmaking involved handling wagers on sporting events like horse races and boxing matches. During the 1930s and ’40s, “wire rooms” became tools to obtain instant sports results. The Chicago Outfit muscled in on a major wire service to gain an informational advantage on sporting results. This advantage, however, faded with television. “Wherever there was a television set, there was a new type of sports wire service,” described a history of bookmaking. Unlike numbers lotteries, bookmaking could be handled largely over the phone and with “runners,” and did not require as many brick-and-mortar locations.119

Gambling, and bookmaking in particular, has sometimes been called the “life blood” of organized crime. This is somewhat misleading. The ease of bookmaking made it commonplace among low-level wiseguys. However, since it was so easy to become a bookie, the market was fairly competitive and the profits limited.120 Mob soldiers tended to use bookmaking as everyday “work” income and to raise capital for more lucrative activities.121 Few wiseguys relied solely on bookmaking to make money.122

Prohibition reversed the fortunes of the Italian gangsters in New York City. But they were also bolstered by historical trends that were accelerating in the 1920s. The Italian gangsters were very much in the right place at the right time. The profits from bootlegging and other rackets, however, would soon lead to internal conflicts among the Mafia families. In our next chapter, we will look at a series of gang fights that have been shrouded in Mafia mythology.