He wanted something more terrible than money: power. And he had decided to carry out any action in order to obtain absolute power and to become the boss of bosses.

—Nicola Gentile, Vita di Capomafia (1963)

Al Capone was causing trouble for the Sicilians in New York. Capone had been on a meteoric rise since his teenage days as a wharf rat on the Brooklyn waterfront. Barely in his thirties, he was vying to become boss of Chicago during Prohibition. Except now Joseph Aiello, a Sicilian mafioso, was ominously calling Capone an “intruder” in Chicago. As the son of immigrant parents from Naples on mainland Italy, Capone was sneered at by many in the Sicilian Mafia who had thrown their support behind Aiello.1

The wild card was Joe Masseria, the new capo di capi or “boss of bosses” of the Mafia. Had Giuseppe “Joe the Boss” Masseria gotten different press, he might today be as well-known as Alphonse “Scarface” Capone or Charles “Lucky” Luciano. Joe Masseria built a sprawling Mafia syndicate, the largest in New York during Prohibition. He was less concerned with Sicilian lineage than with recruiting the toughest, shrewdest bootleggers he could find. Could Al Capone the Neapolitan gangster make a deal with Joe the Boss?

What followed next has been called the “Castellammarese War of 1930–1931,” a conflict which, it is said, created the modern Mafia. In his bestselling autobiography A Man of Honor, Joseph Bonanno, who participated on the winning side, paints a romanticized portrait of the “war.” Under Bonanno's conventional telling of the story, the noble Castellammarese clan of Brooklyn—the true “Men of Honor”—rally to defend themselves against the greedy, low-class Giuseppe “Joe the Boss” Masseria. This so-called Castellammarese War is the source of many myths about the Cosa Nostra. Even its title is misleading. This was hardly a “war”; it was not only about the Castellammarese clan of the Mafia; and it originated back in the 1920s.2

Another set of myths paints this as a generational conflict in which younger “Americanized” mobsters pushed aside the older Sicilian mafiosi. The conventional history suggests that Italian-American gangsters like Charles “Lucky” Luciano were impatient with the more tradition-minded, Sicily-born “Moustache Petes” for failing to modernize to the times in New York City. But as we will see, the historical facts do not square with this popular myth of “Americanization.”3

Rather, the conflicts were simply gang fights over money and power. Different mafiosi with self-interested motives were rebelling against overreaching by three successive boss of bosses: Salvatore D'Aquila, Joe Masseria, and Salvatore Maranzano. Let us call it simply the Mafia Rebellion of 1928–1931. This chapter tells a revisionist history of this conflict and explores what it actually meant for the New York Mafia. It dismantles the myths presented by the winners of the “war” and perpetuated by subsequent writers on the mob.

CAPO DI CAPI: SALVATORE “TOTÒ” D'AQUILA

As we saw in the previous chapter, Joe Masseria rose to power as the leader of bootleggers and professional criminals during Prohibition. The Masseria Family became the largest mob syndicate in Gotham. By 1928, Joe the Boss had one obstacle standing in his way.

The capo di capi of the American Mafia between 1910 and 1928 was an extraordinarily secretive man by the name of Salvatore “Totò” D'Aquila. He spent the majority of his life in Palermo, Sicily, when that city was swarming with rival clans. Barely 5 feet, 2 inches tall, D'Aquila had a penchant for dressing well and speaking smoothly. Soon after disembarking, he became a confidence man in Manhattan, talking his marks out of their money. D'Aquila gradually established himself as a gang leader with a base of power in East Harlem.4

When Giuseppe Morello went to the Atlanta Federal Penitentiary for counterfeiting in 1910, Salvatore D'Aquila became capo di capi at the nadir of the Sicilian Mafia in the second decade of the twentieth century, only to see its fortunes reverse during Prohibition. Flush with cash, Totò D'Aquila moved his family to an elaborately furnished house across from the Bronx Zoo. By outward appearances, D'Aquila was a quiet family man with successful business ventures in real estate, olive oil, and cheese importing.5

Behind the scenes, it was a different story. According to Nicola Gentile, a kind of freelance consultant to mafiosi in the 1920s, D'Aquila significantly expanded the reach of the capo di capi. D'Aquila became “very authoritative,” enlisted a “secret service” of spies, and brought trumped-up charges against rivals. Other informants confirm that D'Aquila presided over trials of mafiosi who allegedly broke rules of the mob. With D'Aquila acting like a kind of judge, the trials were held before the “general assembly” of Mafia representatives from clans across America.6

6:20 P.M., OCTOBER 10, 1928, 13TH STREET & AVENUE A, LOWER EAST SIDE, MANHATTAN: THE DEATH OF SALVATORE D'AQUILA

In October 1928, the fifty-year-old D'Aquila and his wife were consulting a cardiologist on the Lower East Side. During the drive from the Bronx, Totò D'Aquila noticed something wrong with his sedan. After ushering his wife and children into the doctor's office, he went back outside and lifted the hood of the engine.

Three men came up to D'Aquila on the sidewalk. They engaged him in a conversation that turned into a heated argument. Suddenly, the trio pulled out guns and started blasting away. The autumn dusk was shattered by gunfire as nine bullets ripped through D'Aquila's heart, left lung, pancreas, and other vital organs. D'Aquila collapsed on the sidewalk drenched in blood as his killers escaped on foot.7

JOE THE BOSS…OF ALL BOSSES

The death of D'Aquila paved the way for Masseria to become the boss of bosses. He was the obvious replacement: his Masseria Family was by far the largest in Prohibition New York. So, in the winter of 1928, the general assembly of the Mafia elected Giuseppe “Joe the Boss” Masseria to be capo di capi. Previously, the boss of bosses title was more honorary and consultative. The boss of bosses was seen as a kind of wise mediator among the Mafia families. But under D'Aquila, more and more authority had built up in the position. Masseria intended to take advantage of this to expand his interests in New York and westward to mob enclaves in Detroit and elsewhere.

The timing of Masseria's accession later fueled suspicions that he was secretly behind D'Aquila's murder. To this day, it is not at all clear that D'Aquila was, in fact, killed by men sent by Masseria.8 But conflicts are sometimes launched on misinformation, and the underworld eventually came to believe that Masseria was behind it. “Masseria managed to kill Totò D'Aquila, becoming himself boss of the bosses,” summarized Nicola Gentile.9

For now though, Joe the Boss of Bosses stood astride the Cosa Nostra. From the winter of 1928 through early 1930, the Masseria Family sought to expand its interests across the United States and to generate more revenues from New York. The general assembly of the Mafia supported him.

Then, like D'Aquila before him, Masseria began to overreach. Masseria's one-time ally Nicola Gentile said Joe the Boss started “bullying” Mafia representatives; further, his top lieutenants did “not permit objections” and “would command with the force of terror.” Joe the Boss's real problems began when he started to meddle with other Mafia families.10

NEW YORK'S OTHER MAFIA FAMILIES, 1929–1931

When Joe Masseria became boss of bosses, in addition to his Masseria Family, there were four other Mafia families in New York City. As a brief overview, they were as follows:

- The second Mafia family was based in South Brooklyn, which as we saw was full of lucrative waterfront rackets (see chapter 1). This family was headed by Alfred Mineo, an ally of Joe Masseria. But this South Brooklyn waterfront family would really be defined by Mineo's successors as boss, Vincent Mangano and Albert Anastasia.11

- The third was the Castellammarese clan of central Brooklyn, headed by Nicola “Cola” Schiro. These men haled from the port village of Castellammare del Gulfo (“Castle on the Sea of the Gulf”) on the northwestern coast of Sicily. This lawless village was thick with mafiosi known for their ferocity. The Castellammarese, who liked to boast that they were “Men of Honor,” were among the most insular and chauvinistic mafiosi in Sicily.12

- The fourth was the Joseph Profaci Family, also based in Brooklyn. Joseph Profaci and his clan mostly came from a suburb outside Palermo, Sicily. With his relative Joseph Magliocco as his underboss, the Profaci Family held a mix of bootlegging interests, the numbers lottery, and some legitimate businesses. Profaci would later secretly ally himself with the Castellammarese clan.13

- And fifth, but not least, there was the Gaetano Reina Family. The Reina Family had its base in central Bronx and East Harlem. Gaetano Reina took control over much of north New York City's wholesale ice business (a valuable business before refrigeration) by muscling out competitors and taking over routes. Reina's top lieutenants were Tom Gagliano and Tommy Lucchese, close partners who would be pivotal in the upheaval to come.14

The New York Mafia families would soon divide into different coalitions, for and against the boss of bosses Joe Masseria. To keep track of the New York families, and their cross-country alliances, table 3–1 serves as a handy reference guide for this chapter:

PROXY FIGHT IN CHICAGO: AL CAPONE VS. JOSEPH AIELLO

Enter Alphonse Capone. During the late 1920s, Al Capone's “Chicago Outfit” was battling Joseph Aiello's Family for bootlegging territory around the Windy City. Capone was the Brooklyn-born son of poor Neapolitan parents; Aiello was a Sicily-born “Man of Honor.” Given their ethnic backgrounds and prejudices, the Sicilian mafiosi might be expected to back Aiello. And most did.

Joseph Aiello's strongest allies were Gaspare Milazzo in Detroit and Steve Magaddino in Buffalo, both of whom were Castellammarese. They maintained cross-country links with the Castellammarese clan of Brooklyn. They sided first with their fellow villagers, and then with fellow Sicilians. Non-Sicilians like Capone were a distant third.15

By contrast, as we have seen, Joe Masseria did not care so much about Sicilian lineage. Although accounts differ as to who approached whom first, everyone agrees on the outcome: Joe Masseria and Al Capone forged an alliance. Capone would become part of the Mafia through the Masseria Family, if he eliminated Joseph Aiello. The alliance was out in the open.16

FEBRUARY 1930: THE REINA FAMILY REBELS

On the evening of Wednesday, February 26, 1930, boss Gaetano Reina was walking with his blonde mistress to his parked coupe in the Bronx when assassins with a sawed-off shotgun fired ten slugs into Reina's body. As with Salvatore D'Aquila's death in 1928, it is not clear whether Gaetano Reina was killed by the Masseria Family. Reina was involved in the wholesale ice racket, which was awash in violence as competitors fought to control routes. Reina seemed to be expecting an attack at any minute: the police found a loaded .32 caliber revolver in Reina's pocket and a rifle with one hundred extra shells in a secret compartment in his car.17

Nevertheless, Masseria's subsequent actions convinced some that he ordered the hit on Reina. According to Joseph Bonanno, Masseria endorsed Joseph Pinzolo, one of his alleged sycophants, as the replacement boss for the Reina Family. Tom Gagliano and Tommy Lucchese, the top lieutenants of Gaetano Reina, began plotting their revenge. They believed that Masseria was behind Reina'a death, and they were unhappy that Pinzolo was taking over as boss. Reina's murder was “why Tom Gagliano fought with all his might against Joe the Boss,” mob soldier Joe Valachi was told by the faction. The Gagliano/Lucchese faction was the first group in New York to start secretly conspiring against Joe Masseria.18

There are, however, reasons to doubt the Gagliano/Lucchese faction's story of why Joseph Pinzolo ascended to boss. Their faction numbered only about fifteen dissidents in the two-hundred-member Reina Family. Most seemed to have accepted Pinzolo. Gagliano and Lucchese may have simply been jealous that they were passed over for Pinzolo.19

MAY 1930: THE CASTELLAMMARESE CLAN REBELS

The other rebellion in New York City was among the Castellammarese clan in Brooklyn. The official “cause for war” for the Castellammarese clan was the murder of their fellow Castellammarese, Gaspare Milazzo, a boss of Detroit, Michigan. On May 31, 1930, assassins killed Gaspare Milazzo and his driver Sam Parrino in a fish market. This time, Giuseppe “Joe the Boss” Masseria's links to the assassins were close. Joe Masseria was supporting Milazzo's crosstown rival Chester LaMare, whose soldiers were identified by the police as the killers of Milazzo.20 Milazzo's murder helped trigger a chain reaction in New York.

A REVISIONIST HISTORY OF THE CASTELLAMMARESE WAR OF 1930–1931

Mob history really is written by the winners. The conventional history on the Castellammarese War of 1930–1931 and its leader Salvatore Maranzano has been driven by his protégé Joseph Bonanno's autobiography A Man of Honor. In Bonanno's romanticized account, his “hero” Salvatore Maranzano rallies the Castellammarese clan—the true defenders of the Sicilian “Tradition”—against the bastardized gangster Joe Masseria. Bonanno's compelling story of an underworld band of brothers sold many books. Is his history accurate?21

I plan to offer a revisionist history of the “Castellammarese War” by balancing Bonanno's version with the perspectives of others as well as with additional facts. It strips away the romanticism for a more realistic portrait of the modern Mafia.

SALVATORE MARANZANO: MAN OF HONOR OR OPPORTUNISTIC DEMAGOGUE?

In May 1930, Maranzano was nominally just a forty-three-year-old soldier under his boss Nicola Schiro of the Castellammarese clan of Brooklyn. Back in Sicily, Maranzano had been the provincial capo of all the Castellammarese clans until he was forced out by the Fascist government of Benito Mussolini in the 1920s. In America, Maranzano became a successful bootlegger.22 A pompous man, Maranzano and his supporters made sure everyone knew he had once studied to be a priest, spoke Latin, and read histories of ancient Rome.23

Salvatore Maranzano was a political demagogue. Back in Sicily, he had been active in electoral politics, politicking alongside his endorsed candidates. Those who saw Maranzano hold forth remember emotional speeches full of reckless charges and inflammatory rhetoric. As a mob rival, he called Joe Masseria “the poisonous snake of our family,” and he said Al Capone was “staining the organization” of “the honorable society.” Even Bonanno admitted Maranzano may have “overstated Masseria's avarice” and “frightened us a little in order to make us bolder.”24

Maranzano further exploited ethnic identity, a tactic the Mafia would return to over the years. As the mob soldier Joe Valachi later testified before a Senate Committee, the Maranzano camp baldly asserted that “all the Castellammarese were sentenced to death,” though the soldiers “never found out the reason.” “He has condemned all of us,” Maranzano told the Castellammarese, referring to Joe Masseria. “He will only devour you in time.” Nicola Gentile similarly describes how Maranzano “began to inflame…the hearts of his Castellammarese townsman inciting them to vindicate Milazzo” and then goaded “the Palermitani inciting them to vindicate Totò D'Aquila.”25

Maranzano's rallying speeches should be taken with a mountain of salt. Nothing in Joe Masseria's past suggests he would engage in ethnic cleansing of the Castellammarese. Joe the Boss welcomed Sicilians and non-Sicilians of every region into his Family. Two of his “four we are” burglary partners—the brothers Salvatore and Giuseppe Ruffino—were in fact Castellammarese.26 Masseria cared about greenbacks, not bloodlines.

Nonetheless, Maranzano played the ethnic-identity card effectively. Several Castellammarese and Palermitani (the fellow townsmen of D'Aquila) rallied behind Maranzano. The charges resonated: “Masseria has always been our enemy, so much that he had our boss Totò D'Aquila killed,” said Vincenzo Troia.27

FOLLOWING THE MONEY: ECONOMIC ROOTS OF THE MAFIA REBELLION OF 1928–1931

Though less trumpeted as an “official” cause, the Reina Family and the Castellammarese clan also had strong economic motives to depose Masseria. By 1930, the Masseria Family, along with its allies, had achieved territorial dominion over most of Lower Manhattan and South Brooklyn, and also much of East Harlem. The major untapped territories were held by the Reina Family in East Harlem and the Bronx, and by the Castellammarese elsewhere in Brooklyn.

For the Reina Family faction, the replacement of Gaetano Reina with Masseria's ally Joseph Pinzolo was seen as power play in East Harlem. As exemplified by Joe Valachi's account, the anti-Masseria coalition complained that when a soldier made a lot of money, “Joe the Boss will send for him and he will tax him so much and if the guy refused, he will be a dead duck.”28

For many in the Castellammarese clan, and others in Brooklyn, it was the Masseria Family's demands for money tributes that spurred the resentment against Joe the Boss. According to Bonanno, in the summer of 1930, Masseria coerced a $10,000 payment from Cola Schiro, the boss of the Castellammarese clan in Brooklyn. Then, on July 15, 1930, Vito Bonventre, one of the wealthiest bootleggers among the Castellammarese clan was shot down in Brooklyn. Maranzano portrayed this as a Masseria protection racket muscling in on their businesses.29

Even Maranzano had something of a financial angle. In the midst of the conflict, Maranzano gave his soldiers a contract to kill Joseph “Joe the Baker” Catania of the Masseria Family. His soldiers dutifully carried out the hit on Catania, though they were not told the full reasons. His soldiers later learned “that Joe Baker was hijacking [alcohol] trucks on Maranzano.”30

Or take Joe Profaci. Profaci was not a Castellammarese. But he wanted to protect the growing profits of his olive oil company and the illegal numbers lottery in Brooklyn. Despite his wealth, Profaci was known as a cheap boss, and he did not have enough men to take on Masseria himself. The armchair general Profaci started going to strategy meetings of the Castellammarese, boasting “we are going to get rid of these [Masseria] guys, all of them.”31

SALVATORE MARANZANO VS. JOE MASSERIA

Central to his version of the “war,” Bonanno repeatedly ridicules Joe Masseria's weight and slovenliness as metaphors for a defective character. “Joe the Glutton,” as Bonanno calls him, “attacked a plate of spaghetti as if he were a drooling mastiff.” This somehow becomes interpreted as reflecting flaws in Joe the Boss's leadership. “Maranzano believed that Masseria was the type of man who, under intense pressure, would get crazier and crazier and fatter and fatter,” asserts Bonanno.32 This image has stuck. Most recently, in the Home Box Office (HBO) series Boardwalk Empire, Masseria is portrayed as a doughy, treacherous bully.

In reality, Salvatore Maranzano was less svelte than Joe Masseria. At 5 feet, 4 inches Masseria weighed 155 pounds for a body mass index of 27, while Maranzano, at 5 feet, 8 inches, weighed 218 pounds with a body mass index of 33. Or, as a doctor put it, Maranzano had a “tendency to obesity.” A vain man, Maranzano took to wearing a “rubber abdominal support”—a male girdle—underneath his suits to try to smooth down his gut. And while Maranzano dressed well, Masseria was no slouch either: he was a tailor in his youth and is described as almost invariably wearing a suit and hat.33

Although Salvatore Maranzano spoke more eloquently than Joe Masseria, their characters were not so different. Frank Costello saw right through Maranzano. Like Masseria, Frank Costello used his native intelligence to become a wealthy bootlegger and well-coifed powerbroker in New York. Nevertheless, Costello never bought into Maranzano's image. Comparing his one-time boss Masseria to the pompous Maranzano, Costello told his friend that a “greaseball is a greaseball,” by which he meant “that Maranzano, despite his polished appearance was of the same ilk as Masseria.”34

3:50 P.M., FRIDAY, AUGUST 15, 1930, EAST 116TH STREET, ITALIAN EAST HARLEM: THE SNEAK ATTACK ON GIUSEPPE MORELLO

East Harlem was enduring a sweltering summer in 1930, with temperatures topping 100 degrees, until the heat wave broke the second week of August. That week, Giuseppe Morello went to his second-story office in a building he owned at 352 East 116th Street.

Late in the afternoon of Friday, August 15, Morello was sitting around a table in his spartan office with building contractors Joseph Perrano and Gaspar Pollaro. They were talking business. Around 3:50 p.m., there was a knock at the door, which Morello got up to answer. As Morello cracked open the door, two men pushed their way in. They fired at the sixty-three-year-old Morello, who “kept running around the office,” until he succumbed to five bullet wounds. After being shot, Perrano dove out the second floor window and perished. Only Pollaro barely survived.35

There is no sign that the Masseria Family even knew a “war” had been declared. Giuseppe Morello was hardly expecting trouble: he went into his office ]unarmed and answered the door himself. He never knew his killer, Sebastiano “Buster” Domingo, a hit man imported from Chicago. Salvatore Maranzano wanted an early knockout of the veteran consigliere because, if Morello went into hiding, he “could exist forever on diet of hard bread, cheese and onions.”36

The Reina Family faction in East Harlem was equally surprised by Morello's murder only blocks away. Until that evening, they had no idea there were other rebels. Gagliano and Lucchese were “sneaking” around, “not knowing there was someone else who had the same intentions.” Throwing their support to the coalition, they got their vengeance when Girolamo “Bobby Doyle” Santuccio killed replacement boss Joseph Pinzolo on September 5, 1930.37

2:45 P.M., WEDNESDAY, NOVEMBER 5, 1930, PELHAM PARKWAY SOUTH, THE BRONX: THE LIEUTENANTS FALL

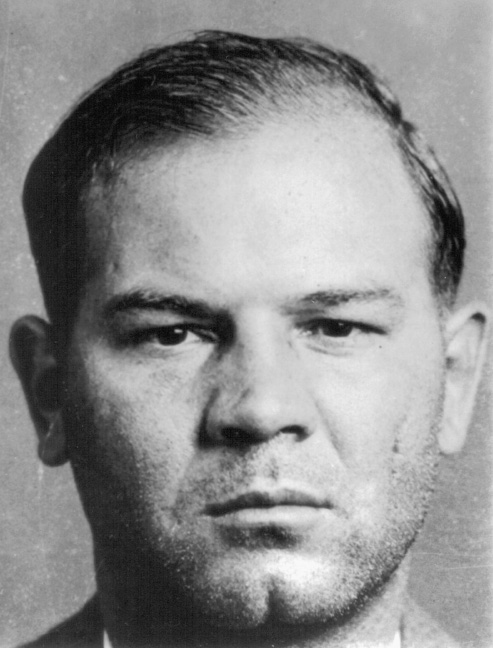

The anti-Masseria rebellion got its next big break a few months later when soldier Joe Valachi spotted Joe the Boss entering an apartment complex in the Bronx with two of his top lieutenants during the conflict, Alfred Mineo (a Brooklyn boss in his own right) and Stephen Ferrigno (Mineo's deputy). Maranzano dispatched three of his best shooters: Girolamo “Bobby Doyle” Santuccio, Nick Capuzzi, and Sebastiano “Buster” Domingo. Smuggling shotguns in guitar cases, they set up a gunner's nest in a ground-floor apartment.

On Wednesday, November 5, Masseria held a conference with a half dozen of his men at the apartment complex. Around 2:45 p.m., Ferrigno and Mineo left ahead of their boss. As they walked around the garden, shotgun blasts killed them instantly. Hearing the blasts, Joe Masseria hid inside the apartment until the police arrived. Joe the Boss had narrowly evaded gunfire again. But the rapid loss of Masseria's top two lieutenants, his consigliere Giuseppe Morello, and his ally Joseph Pinzolo, was destabilizing the Masseria Family.38

3–1: Maranzano hit man Girolamo “Bobby Doyle” Santuccio, ca. 1930. (Used by permission of the John Binder Collection)

DECEMBER 1930, BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS: GENERAL ASSEMBLY OF THE MAFIA

The Mafia clans on the sidelines were unhappy with the bloodshed. Gangland shootings were bad for business. The Masseria Family was being decapitated. The clans called for a general assembly of Mafia representatives to take place in December 1930 in Boston.

The general assembly tried to make peace by stripping Masseria of the title of capi di capi and temporarily replacing him with the well-liked Gaspare Messina. The assembly then set up a commission to try to negotiate a peace between the two sides.39

Salvatore Maranzano would have no talk of peace with Joe Masseria still alive. Maranzano thwarted peace negotiations and made overtures to potential defectors. “Those who want to cross into my ranks are still in time to do so,” said Maranzano. He sent word that if Joe the Boss were disposed of by his own men, there would be no other reprisals.40

THE BETRAYAL OF JOE MASSERIA

Joe Masseria's erstwhile lieutenant Charles Luciano had had enough. Luciano had not joined the Masseria Family for the vainglory of bosses. His cabal wanted to end the conflict. And the quickest way was to remove their weakened boss.

Charles Luciano, the high-stakes gambler, secretly accepted the overture from Salvatore Maranzano. They met in a private house in Brooklyn in the spring of 1931. The conversation between the men was veiled, but gravely clear:

“Do you know why you are here?” Salvatore Maranzano began.

“Yes,” Luciano answered. He never would have stepped foot there had he been unsure.

“Then I don't have to tell you what has to be done,” Maranzano continued.

“No,” he replied.

“How much time do you need to do what you have to do?” Maranzano asked.

“A week or two,” he answered. And with that, Luciano set out to betray his boss.41

2:00 P.M., WEDNESDAY AFTERNOON, APRIL 15, 1931, NUOVA VILLA TAMMARO RESTAURANT: THE ASSASSINATION OF JOE MASSERIA

Joe Masseria spent the winter behind guards at his penthouse atop a fifteen-story complex at 15 West 81st Street just off Central Park. Joe the Boss could not stay cooped up forever.

On Wednesday afternoon, April 15, 1931, Masseria's men persuaded him to venture out to a restaurant called the Nuova Villa Tammaro on Coney Island, Brooklyn.42 Contrary to his image as a slob, Joe Masseria dressed dapperly: a light grey three-piece tailored suit with handkerchief, a white madras shirt, and black Oxford dress shoes. Properly attired, he went downstairs to his armored sedan and rumbled off to Coney Island.43

Around 1:00 p.m., Masseria's sedan arrived outside the Nuova Villa Tammaro. As Masseria walked to the restaurant, he breathed in the warm sea breeze of Coney Island.44 Contrary to myth, Masseria did not gorge on pasta that afternoon. The purported glutton skipped lunch. Masseria sat around a table with a few men he knew, playing cards for cash and silver. The proprietor Gerardo Scarpato later claimed that he had just stepped out for a walk.45

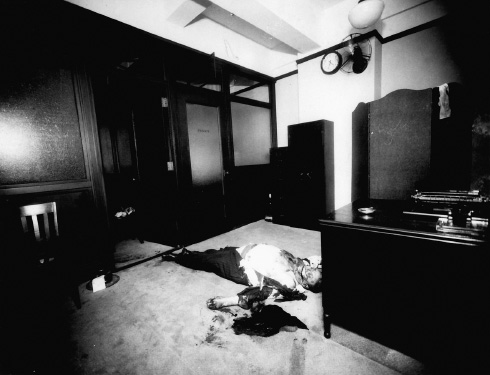

For the first time in his life, Giuseppe Masseria did not see them coming. At 2:00 p.m., as Masseria was sitting in his chair, he was shot from behind. Four bullets hit his back. The fifth and fatal bullet ripped through his brain and exited his eye socket. He fell out of his chair onto the floor. Joe the Boss was dead.46

The gunmen walked out of the restaurant in a hurry. Whether from nerves or shock, they left behind four overcoats. The assassins got into an automobile and sped off. Police found their abandoned car about two miles away in Brooklyn. The automobile had been reported stolen; its license plates were unregistered. In the back were a pair of .38 revolvers and a .45 automatic.47

The question of who betrayed Joe Masseria has focused on famous mafiosi. Multiple insiders confirm that Charles Luciano planned Masseria's assassination. Joe Valachi later testified that he had heard that Vito Genovese, Frank “Cheech” Livorsi, Joseph “Joe Stretch” Stracci, and Ciro Terranova were among those present at the Nuova that afternoon.48

But there was another gangster who has since been largely forgotten. In April 1931, John “Silk Stockings” Giustra was a thirty-two-year-old racketeer on the Brooklyn waterfront. The New York Police Department identified Giustra as their prime suspect in the shooting. In 1940, an internal NYPD note stated: “Confidential information was received by the Detective in the case that the person who shot and killed the deceased was one John Giustra,” and that one of the coats left behind “was identified as the property of [Giustra].” Because Giustra himself was murdered on July 9, 1931, the NYPD closed the case.49 In 1952, another informant on the waterfront stated: “John ‘Silk Stocking’ Giustre [sic] murdered Joe the Boss and thought he would take over from him,” but Phil Mangano, Albert Anastasia, and others “double-crossed Silk Stocking.”50 The conflict may have been affected by yet another individual's crass ambitions.

WEDNESDAY EVENING, APRIL 15, 1931, CHARLES LUCIANO'S RESIDENCE

That evening, Charles Luciano gathered his men at his Manhattan residence. Luciano summoned Vincenzo Troia, an ally of Maranzano, to his residence for a message. “Vincenzo, tell your compare [godfather] Maranzano that we killed Masseria not to serve him, but for our personal reasons,” Luciano warned.51 They wanted to go back to making money.

LATE MAY 1931, CONGRESS PLAZA HOTEL, 520 MICHIGAN AVENUE, CHICAGO, ILLINOIS: GENERAL ASSEMBLY OF THE MAFIA

With Masseria's blood still on the floor of Nuova Villa, Maranzano called Al Capone in Chicago. Capone had succeeded in eliminating Joseph Aiello and had become the unquestioned crime boss of the City of Broad Shoulders. They agreed to call a general assembly of the Mafia.52

In late May 1931, Al Capone hosted the Mafia's general assembly at the Congress Plaza Hotel on Lake Michigan. A few hundred representatives from Cleveland, Pittsburgh, New York, and elsewhere traveled across the country to Chicago.53 The mob was in disarray. “In the general assembly…an indescribable confusion reigned,” recalled Nicola Gentile, who attended the conclave. “Some representatives, mindful of the past dictatorial regime of Masseria…had proposed to elect for the job of boss of the bosses a commission composed of six,” Gentile said. The idea of a power-sharing commission had a lot of support.54

The ambitious Salvatore Maranzano outmaneuvered them. Maranzano cynically cut a deal with the Neapolitan Al Capone, the man whom Maranzano only recently had said was “staining the organization” of the Mafia. In exchange for Capone agreeing to “affirm Maranzano's supremacy in the national scene,” he would recognize Capone in Chicago after all. Next, Maranzano cajoled or intimidated the smaller clans. It worked. “Maranzano was thus elected boss of the bosses of the United States mafia,” explained Gentile.55

JUNE 1931, FEDERAL GRAND JURY, CHICAGO, ILLINOIS

“CAPONE IS INDICTED IN INCOME TAX CASE,” blared the June 6, 1931, edition of the New York Times. Weeks after the general assembly departed Chicago, the United States attorney for Chicago announced that Alphonse Capone was being indicted on charges of income tax evasion on $1 million of illegal income ($14 million in present dollars).56

Capone's tax indictment shook the underworld. New York mobsters hardly bothered filing income tax returns, and they certainly did not pay taxes on bootlegging and other illegal income. They would have a very difficult time explaining their assets.57

AUGUST 1–3, 1931, NUOVA VILLA TAMMARO, CONEY ISLAND, BROOKLYN: MEET THE NEW BOSS OF BOSSES

The Castellammarese threw a banquet in honor of Maranzano from Saturday, August 1 through Monday, August 3, 1931, under the guise of a local Italian festival. Pouring salt in the wound, they chose the same site where Joe Masseria was killed: the Nuova Villa Tammaro restaurant, freshly scrubbed of blood stains.58

3–2: Nuova Villa Tammaro restaurant after shooting of Joe Masseria, 1931. Salvatore Maranzano would celebrate his ascension to boss of bosses at the same site in August 1931. (Photo from the New York Daily News Archive, used by permission of Getty Images)

The bacchanalian weekend was an intoxicating experience for Maranzano. The clans sent fat envelopes of cash as tribute to the capo di capi. “In the banquet room, on the immense decorated table, with magnificent lavishness, there towered a grandiose tray on which handfuls of dollars were placed,” described Gentile. The piles of money totaled $115,000 ($1.7 million in current dollars). “Compare, these victories have made me drunk!” admitted Maranzano. “I feel a ball of fire inside!”59

Like a dictator's parade, there was a palpable phoniness to the honors. The attendees were greeted by Maranzano's soldiers, who steered each attendee to the cash tray. “Viva il nostro capo!” shouted his soldiers. “Long live our boss!” Street guys put on airs for the refined boss. “Many, who, even being boors, cared to appear like gentlemen,” Gentile recalled. His supplicants praised him a little too much, laughed a little too loudly. “I would like to go to Germany to be more secure,” Maranzano mumbled nervously.60

EAGLE BUILDING CORPORATION, PARK AVENUE, GRAND CENTRAL BUILDING

The capo di capi sets up his empire. He opens an elaborate suite of Art Deco–style offices on the ninth floor of the bustling Grand Central Building at 230 Park Avenue. In the mornings, he walks through the spectacular expanse of Grand Central Station. The Eagle Building Corporation is the official name of the enterprise, though no one knows what it does exactly. He hires an English-speaking secretary. File cabinets contain the meticulous paperwork of business concerns. To be closer to work, he leases a luxurious apartment on 42nd Street in Manhattan.61

Beneath the surface is something else. The nominal president of Eagle Building Corporation is James Alescia, a convicted narcotics trafficker who served time at the Atlanta Federal Penitentiary. In the afternoons, the anteroom is full of gangsters waiting impatiently to see the big man. He keeps even important mafiosi like Steve Magaddino waiting an hour or more to see him. The capo di capi can do that.62

SAME AS THE OLD BOSS OF BOSSES

As an aficionado of ancient Rome, Maranzano should have learned from Caligula, who sought to concentrate all power in himself (“Let there be One Lord, One King,” he declared). He became the first Roman emperor stabbed to death by conspirators.63

Maranzano proved even more power hungry than Masseria. He made a list of people he wanted dead. “Al Capone, Frank Costello, Charley Lucky, Vito Genovese, Vincent Mangano, Joe Adonis, Dutch Schultz,” recounted Joe Valachi. “These are all important names at the time.” They all happened to be former Masseria allies. So much for no reprisals. An FBI electronic bug picked up Steve Magaddino describing how Maranzano “wanted to shoot in the worst way” various men. “I said what are you crazy…there isn't any need to,” recalled Magaddino. The Castellammarese, the vaunted band of brothers, started backbiting over Maranzano.64 Perhaps even more galling, Maranzano began threatening their money, too. There were rumors that Maranzano's men were hijacking booze trucks belonging to fellow mafiosi and dividing the spoils. A new cabal began plotting against the capo di capi.65

Although Charles Luciano was involved again, the roles of Tom Gagliano and Tommy Lucchese of the former Reina Family have been seriously underestimated.66 First, they had motive: Gagliano and Lucchese owned trucking companies in the garment district, an industry Maranzano had been eyeing. Joe Valachi recalled how Tommy Lucchese told him that the capo di capi “had been doing a lot of bad,” and asked if “I knew if Maranzano hijacked trucks of piece goods.”67 Second, they had means: Gagliano and Lucchese had become regulars in his Park Avenue office. Bonanno said he learned Lucchese was funneling intelligence on “Maranzano's office habits and his preoccupations with the IRS.” Gentile likewise suggested there was a mole in his office.68 Third, they had opportunity. Both would be present at the scene of the crime.

3:45 P.M., THURSDAY AFTERNOON, SEPTEMBER 10, 1931, OFFICE OF SALVATORE MARANZANO: KILLING THE BOSS OF BOSSES

On the afternoon of Thursday, September 10, Mr. Maranzano had his secretary, Miss Francis Samuels, keep several men waiting in the anteroom. In his office, Maranzano sat at his wide desk looking over paperwork. The metal fan buzzed next to the wall clock. Around 3:40 p.m., Tom Gagliano and Tommy Lucchese walked into the anteroom. Minutes ticked by….69

At 3:45 p.m. four lawmen burst into the anteroom brandishing badges and guns. Mr. Maranzano had told his men that he'd received a tip that a government raid on his office was imminent. Not to worry, though. His accountants assured him his office records could withstand even the most rigorous examination by the IRS. To avoid a gun charge, Mr. Maranzano instructed his men to stop bringing firearms to the office for the near future. His bodyguard Girolamo Santuccio did not like being unarmed, but he obeyed his boss.70

This must have been the raid everyone was expecting. The four lawmen were dressed properly, they flashed metal badges, and they were Jews not Italians. They ordered everyone to line up against the wall of the anteroom. “Who can we talk to?” demanded an agent. Hearing the commotion, Maranzano poked his head out his office.71

“I am the one responsible for the office,” Maranzano interjected. “You can talk to me.” He was prepared for this harassment by the government. “There does not exist any contraband goods here. This office is a commercial office, in place with the law,” he declared. One of the lawmen held the group in the anteroom at gunpoint, including his unarmed bodyguard Santuccio. The other agents followed Maranzano into his private office.72

The plan was working: they were alone with Maranzano in his inner sanctum. The real names of the lead “agents” were Sam “Red” Levine and Abe “Bo” Weinberg, and they were not IRS agents. They were professional hit men. And they were there to kill Maranzano. Given they were on the ninth floor of a busy office building, their plan was to use stilettos to quietly stab him to death. Except Maranzano figured it out. They started shouting at each other.73

Unarmed and outnumbered, the refined gentleman disappeared. Maranzano fought fiercely. A stiletto pierced his left elbow, causing blood to run down his muscular arm, yet he continued fighting. Noise was no longer the assassin's main concern. They reached for their guns and fired shots into Maranzano's right arm, chest, and abdomen. Riddled with bullets, Maranzano fell back into his chair. The assassins then picked up the stilettos and thrust the sharp points into him. The coup de grâce pierced an artery in his neck.74

3–3: Body of Salvatore Maranzano in his Park Avenue office, September 1931. (Used by permission of the John Binder Collection)

Red Levine ran into the anteroom and told everyone to leave. The hit men ran to the stairs, followed by Tom Gagliano, Tommy Lucchese, and the rest of the waiting men. In a bizarre coincidence, on their way out the departing hit men ran into the Irish hit man Vincent “Mad Dog” Coll, who was on his way to discuss a contract with Maranzano.75 When Lucchese was questioned as to why he left without checking to see whether Maranzano was still alive, he said lamely, “Nobody likes to stay in a place when something happens.” In truth, Lucchese had helped set the trap: his men spent the day distracting Maranzano's soldiers, keeping them from stopping by the office. Everyone had abandoned Maranzano save for two: his loyal bodyguard Girolamo Santuccio and his devoted secretary Miss Samuels, who found their boss dead in his office.76

THE PURGE THAT WASN'T

In the aftermath of Maranzano's murder, there were stories that his assassination was coordinated with a nationwide purge of all his loyalists. These rumors gained credence when Richard “Dixie” Davis, a disbarred mob lawyer, claimed in a 1939 Collier's article that hit man Bo Weinberg said there was “about ninety guineas knocked off all over the country” simultaneously in a purge that “Americanized the mobs.” Less noticed was Davis's admission that he had “never been able to check up the accuracy of Bo's assertion” of a simultaneous mass murder.77

When historians looked for evidence of this alleged purge, they could not substantiate it. Poring over newspapers from across the country, they could find only a handful of gangland hits even conceivably connected to the Maranzano assassination.78 Nevertheless, the “purge myth” abides. John H. Davis's Mafia Dynasty asserts that Luciano “ordered a purge of the old guard” in which “sixty Maranzano loyalists” were killed.79

The myth is too compelling; it is an archetype of the human mind. The imagery can be traced to the legendary Night of the Sicilian Vespers, when after the Easter evening prayers of March 30, 1282, Sicilians rose up and overnight massacred their French foreign rulers. Giuseppe Verdi immortalized it in his 1861 opera I Vespri Siciliani. Director Francis Ford Coppola and writer Mario Puzo were playing on this imagery in their 1972 masterpiece The Godfather. In the penultimate sequence, Michael Corleone is shown sponsoring his niece's Roman Catholic baptism as his men simultaneously assassinate his enemies in bloody hits. They are compelling images, but they are just images.80

“CASTELLAMMARESE WAR” OR GANG FIGHT?

This leads to a larger point about Joe Bonanno's romantic account. Painting these events as a “war” in service of a mob myth diminishes the gravity of the word war. The total number of casualties nationwide in the “Castellammarese War of 1930–1931” was under twenty mafioso.81 To put it in perspective, recall that more than a thousand Prohibition-era bootleggers were killed in New York City between 1920 and 1930—an average of seventy-seven men a year.82

Although he occasionally drifts into war language, Nicola Gentile calls the conflict “The Fight between the Gangs.” This is a more accurate description. In New York, outside of a small group of men around Masseria and Maranzano, most wiseguys went about their business. Giuseppe Morello and others were not even armed for much of the “war.” After the police warned Masseria to stop the fighting, Masseria ordered his men to disarm. He was apparently more worried about a police crackdown.83

Joe Bonanno's breathless talk of Maranzano's “wartime staff” and vast supplies of “money, arms, ammunition and manpower” is just hyperbole.84 Although Joe Valachi heard stories of war chests, he saw little money put into the fight. Valachi testified that Maranzano's four main hit men together were paid the paltry sum of “$25 a week” (about $350 in current dollars). As it was “kind of rough” to survive on his $6 split, Valachi moonlighted as a burglar to make ends meet during the “war.”85 An FBI electronic bug picked up Steve Magaddino mocking Maranzano's meager funding of the hit men. “He didn't give them anything. He only would give them sandwiches,” laughed Steve Magaddino.86

THE “MOUSTACHE PETES”

Another myth is that the conflict was about a younger generation of “Americanized” mobsters purging the older, tradition-bound “Moustache Petes.” In his book Five Families, journalist Selwyn Raab claims that “Luciano had become increasingly frustrated by Masseria's refusal to adopt his ideas for modernizing…by cooperating with other Italian and non-Italian gangs” and that he “referred disparagingly to Masseria and his ilk as ‘Moustache Petes’ and ‘greasers.’”87

Labeling Joe Masseria a “Moustache Pete” renders the term meaningless: Joe the Boss enthusiastically created the first pan-Italian “Americanized” mob. There is also no sign that Masseria barred his men from working with others. The Masseria Family's members collaborated with Irish and Jewish gangsters on the docks, in the garment district, and elsewhere. Indeed, in March 1930, Masseria was arrested in a gambling resort in Miami Beach in the company of Jewish gangsters Harry Brown and Harry “Nig” Rosen.88

Neither did the two other mafiosi pointed to as “Moustache Petes” fit the stereotype of tradition-bound, ethnically isolated Sicilians. Giuseppe Morello was a mustachioed Sicilian, his whiskers drooping down over his gaunt face. Yet when he was boss of his Morello Family, he partnered with Irish counterfeiters Jack Gleason, Tom Smith, and Henry Thompson.89 Even Salvatore Maranzano had in his inner circle a convicted drug trafficker in James Alescia and a Neapolitan in Joe Valachi. And it was Maranzano who ultimately validated Al Capone and his Chicago Outfit.90

LATE SEPTEMBER 1931: THE CREATION OF THE COMMISSION

After Maranzano, there would never again be an all-powerful boss of bosses. Between 1928 and 1931, the Cosa Nostra saw the murders of three sitting capo di capi: Salvatore D'Aquila in October 1928, Joe Masseria in April 1931, and Salvatore Maranzano in September 1931. All three overreached and were violently deposed. Former capo di capi Giuseppe Morello was killed in August 1930 as well. The general assembly concluded that giving such a title “to just one, could swell the head of the elected person and induce him to commit unjustifiable atrocities.”91

As we will see, new technologies and rackets were expanding opportunities for more dispersed crews of wiseguys as well. Their sophisticated operations would stretch across states and multistate regions. No dictatorial boss would be able to control everything. Although the Mafia family structure would be essential to their success, the money operations would be run by the caporegimes (captains) and street soldiers.

In the fall of 1931, the general assembly of the Mafia abolished the capo di capi title. They replaced it with a power-sharing commission. This was not the invention of Charles Luciano. Rather, it was the very same idea that the general assembly of the Mafia nearly adopted back in May 1931. It would serve as a forum to discuss major decisions and arbitrate disputes. As Nicola Gentile explained, “With the administration of this commission one could begin to breathe a more trustworthy air,” and men could return to “the best positions from which they could gain large profits.”92

The Commission, as it came to be called, had seven charter members. Given Gotham's importance, each of the five bosses of the New York families received a seat. These included the incumbent bosses Charles Luciano, Tom Gagliano, and Joseph Profaci, and two new bosses from Brooklyn: Vincent Mangano (who replaced a Maranzano loyalist) and Joseph Bonanno (who replaced Maranzano himself). Steve Magaddino of Buffalo got the sixth seat as an influential Castellammarese with surprising strength in upstate New York. Al Capone held the seventh seat for Chicago, which also represented by proxy the smaller western clans.93

Capone's seat on the Commission would be short-lived. On October 6, 1931, the trial of United States v. Alphonse Capone commenced in federal court in Chicago. Twelve days later, on October 18, 1931, the federal jury found him guilty of income tax evasion for failing to pay taxes on illegal revenues. Paul “The Waiter” Ricca of Chicago (who stands on the far left of the cover of this book) would take Capone's seat on the Commission. Maranzano's fear of the taxman was not so crazy after all.94

THE COMMISSION: FOUNDING MEMBERS, 1931

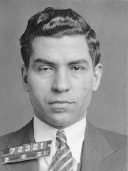

3–4: Tomasso Gagliano, boss of the Gagliano Family. (Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration)

3–5: Charles Luciano, boss of the Luciano Family. (Courtesy of the New York Police Department)

3–6: Vincent Mangano, boss of the Mangano Family. (Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration)

3–7: Joseph Bonanno, boss of the Bonanno Family. (Used by permission of the NYC Municipal Archives)

3–8: Joseph Profaci, boss of the Profaci Family. (Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration)

3–9: Al Capone, boss of the Chicago Outfit (© Bettman/CORBIS)

3–10: Steve Magaddino, boss of the Buffalo Arm. (Photo by Walter Albertin, courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, New York World-Telegram and Sun Newspaper Photograph Collection)

Although Joe Bonanno and others have portrayed the “Castellammarese War of 1930–1931” as a defense of the honor of the Castellammarese clan, the facts show it to be something less romantic. Rather, the Mafia Rebellion of 1928–1931 was mostly about money and power. But the rise of the modern Mafia was more than just the result of high-level intrigue among mob bosses. Our next chapter looks at how the Mafia's soldiers gained footholds in the labor unions.