Chapter 1

Hello, JavaFX!

IN THIS CHAPTER

Getting a quick overview of what JavaFX is and what you can do with it

Getting a quick overview of what JavaFX is and what you can do with it

Looking at a basic JavaFX program

Looking at a basic JavaFX program

Importing the classes you need to create a JavaFX program

Importing the classes you need to create a JavaFX program

Creating a class that extends the JavaFX Application

class

Creating a class that extends the JavaFX Application

class

Using classes such as Button

, BorderPane

, and Scene

to create a user interface

Using classes such as Button

, BorderPane

, and Scene

to create a user interface

Create an event handler that will be called when the user clicks a button

Create an event handler that will be called when the user clicks a button

Examining an enhanced version of the Click Me program

Examining an enhanced version of the Click Me program

Up to this point in this book, all the programs are console-based, like something right out of the 1980s. Console-based Java programs have their place, especially when you’re just starting with Java. But eventually you’ll want to create programs that work with a graphical user interface (GUI).

This chapter gets you started in that direction using a Java GUI package called JavaFX to create simple GUI programs that display simple buttons and text labels. Along the way, you learn about several of the key JavaFX classes that let you create the layout of a GUI.

Prior to JavaFX, the main way to create GUIs in Java was through the Swing API. JavaFX is similar to Swing in many ways, so if you’ve ever used Swing to create a user interface for a Java program, you have a good head start at learning JavaFX.

Prior to JavaFX, the main way to create GUIs in Java was through the Swing API. JavaFX is similar to Swing in many ways, so if you’ve ever used Swing to create a user interface for a Java program, you have a good head start at learning JavaFX.

Oracle has announced that JavaFX will eventually replace Swing. Although Swing is still supported in Java 8 and will be supported for the foreseeable future, Oracle is concentrating new features on JavaFX. Eventually, Swing will become obsolete.

Perusing the Possibilities of JavaFX

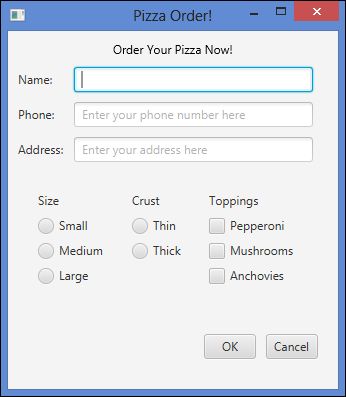

One of the basic strengths of JavaFX is its ability to let you easily create complicated GUIs with all the classic user interface gizmos everyone knows and loves. Thus, JavaFX provides a full range of controls — dozens of them in fact, including the classics such as buttons, labels, text boxes, check boxes, drop-down lists, and menus, as well as more exotic controls such as tabbed panes and accordion panes. Figure 1-1

shows a typical JavaFX user interface that uses several of these control types to create a form for data entry.

Truthfully, the data-entry form shown in Figure 1-1

is pretty plain. For example, the appearance of the buttons, labels, text fields, radio buttons, and check boxes are a bit dated. The visual difference between this dialog box and one you could have created in Visual Basic on a Windows 95 computer 20 years ago are minor.

Where JavaFX begins to shine is in its ability to allow you to easily improve the appearance of your user interface by using Cascading Style Sheets (CSS)

. CSS makes it easy to customize many aspects of the appearance of your user interface controls by placing all the formatting information in a separate file dubbed a style sheet. A style sheet

is a simple text file that provides a set of rules for formatting the

various elements of the user interface. You can use CSS to control literally hundreds of formatting properties. For example, you can easily change the text properties such as font, size, color, and weight, and you can add a background image, gradient fills, borders, and special effects such as shadows, blurs, and light sources.

Figure 1-2

shows a variation of the form that was shown in Figure 1-1

, this time formatted with CSS. The simple CSS file for this form adds a background image, enhances the text formatting, and modifies the appearance of the buttons.

Besides CSS, JavaFX offers many other capabilities. For example:

-

Visual effects:

You can add a wide variety of visual effects to your user interface elements, including shadows, reflections, blurs, lighting, and perspective effects.

-

Animation:

You can specify animation effects that apply transitions gradually over time.

-

3-D objects:

You can draw three-dimensional objects such as cubes, cylinders, spheres, and more complex shapes.

-

Touch interface:

JavaFX can handle touchscreen devices, such as smartphones and tablet computers with ease.

You discover all these features and more in later chapters of this minibook. But for now, it’s time to have a look at a simple JavaFX program so you can get a feel for what JavaFX programs look like.

Looking at a Simple JavaFX Program

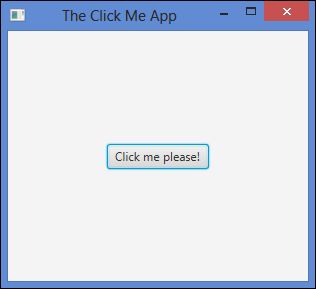

Figure 1-3

shows the user interface for a very simple JavaFX program that includes just a single button. Initially, the text of this button says Click me please!

When you click it, the text of the button changes to You clicked me!

If you click the button again, the text changes back to Click me please!

Thereafter, each time you click the button, the text cycles between Click me please!

and You clicked me!

To quit the program, simply click the Close button (the X at the upper-right corner.)

Listing 1-1

shows the complete listing for this program.

LISTING 1-1

The Click Me Program

import javafx.application.*;

import javafx.stage.*;

import javafx.scene.*;

import javafx.scene.layout.*;

import javafx.scene.control.*;

public class ClickMe extends Application

{

public static void main(String[] args)

{

launch(args);

}

Button btn;

@Override public void start(Stage primaryStage)

{

// Create the button

btn = new Button();

btn.setText("Click me please!");

btn.setOnAction(e -> buttonClick());

// Add the button to a layout pane

BorderPane pane = new BorderPane();

pane.setCenter(btn);

// Add the layout pane to a scene

Scene scene = new Scene(pane, 300, 250);

// Finalize and show the stage

primaryStage.setScene(scene);

primaryStage.setTitle("The Click Me App");

primaryStage.show();

}

public void buttonClick()

{

if (btn.getText() == "Click me please!")

{

btn.setText("You clicked me!");

}

else

{

btn.setText("Click me please!");

}

}

}

The sections that follow describe the key aspects of this basic JavaFX program.

Importing JavaFX Packages

Like any Java program, JavaFX programs begin with a series of import

statements that reference the various JavaFX packages that the program will use. The Click Me program includes the following five import

statements:

import javafx.application.*;

import javafx.stage.*;

import javafx.scene.*;

import javafx.scene.layout.*;

import javafx.scene.control.*;

As you can see, all the JavaFX packages begin with javafx

. The Click Me program uses classes from five distinct JavaFX packages:

-

javafx.application

: This package defines the core class on which all JavaFX applications depend: Application

. You read more about the Application

class in the section “Extending the Application Class

” later in this chapter.

-

javafx.stage

: The most important class in this package is the Stage

class, which defines the top-level container for all user interface objects. Stage

is a JavaFX application’s highest-level window, within which all the application’s user-interface elements are displayed.

-

javafx.scene

: The most important class in this package is the Scene

class, which is a container that holds all the user interface elements displayed by the program.

-

javafx.scene.layout

: This package defines a special type of user-interface element called a layout manager.

The job of a layout manager is to determine the position of each control displayed in the user interface.

-

java.scene.control

: This package contains the classes that define individual user interface controls such as buttons, text boxes, and labels. The Click Me program uses just one class from this package, Button

, which represents a button that the user can click.

Extending the Application Class

A JavaFX application is a Java class that extends the javafx.application.Application

class. Thus, the declaration for the Click Me application’s main class is this:

public class ClickMe extends Application

Here, the Click Me application is defined by a class named ClickMe

, which extends the Application

class.

Because the entire javafx.application

package is imported in line 1 of the Click Me program, the Application

class does not have to be fully qualified. If you omit the import

statement for the javafx.application

package, the ClickMe

class declaration would have to look like this:

Because the entire javafx.application

package is imported in line 1 of the Click Me program, the Application

class does not have to be fully qualified. If you omit the import

statement for the javafx.application

package, the ClickMe

class declaration would have to look like this:

public class ClickMe

extends javafx.application.Application

The Application

class is responsible for managing what is called the life cycle

of a JavaFX application. The life cycle consists of the following steps:

-

Create an instance of the Application

class.

-

Call the init

method.

The default implementation of the init

method does nothing, but you can override the init

method to provide any processing you want to be performed before the application’s user interface displays.

-

Call the start

method.

The start

method is an abstract method, which means that there is no default implementation provided as a part of the Application

class. Therefore, you must provide your own version of the start

method. The start

method is responsible for building and displaying the user interface. (For more information, see the section “Overriding the start Method

” later in this chapter.)

-

Wait for the application to end, which typically happens when the user signals the end of the program by closing the main application window or choosing the program’s exit command.

During this time, the application isn’t really idle. Instead, it’s busy performing actions in response to user events, such as clicking a button or choosing an item from a drop-down list.

-

Call the stop

method.

Like the init

method, the default implementation of the stop

method doesn’t do anything, but you can override it to perform any processing necessary as the program terminates, such as closing database resources or saving files.

Launching the Application

As you know, the standard entry-point for Java programs is the main

method. Here is the main

method for the Click Me program:

public static void main(String[] args)

{

launch(args);

}

As you can see, the main

method consists of just one statement, a call to the Application

class’ launch

method.

The launch

method is what actually starts a JavaFX application. The launch

method is a static

method, so it can be called in the static context of the main

method. It creates an instance of the Application

class and then starts the JavaFX lifecycle, calling the init

and start

methods, waiting for the application to finish, and then calling the stop

method.

The launch

method doesn’t return until the JavaFX application ends. Suppose you wrote the main

method for the Click Me program like this:

public static void main(String[] args)

{

System.out.println("Launching JavaFX");

launch(args);

System.out.println("Finished");

}

Then, you would see Launching JavaFX

displayed in the console window while the JavaFX application window opens. When you close the JavaFX application window, you would then see Finished

in the console window.

Overriding the start Method

Every JavaFX application must include a start

method. You write the code that creates the user interface elements your program’s user will interact with in the start

method. For example, the start

method in Listing 1-1

contains code that displays a button with the text Click Me!

When a JavaFX application is launched, the JavaFX framework calls the start

method after the Application

class has been initialized.

The start

method for the Click Me program looks like this:

@Override public void start(Stage primaryStage)

{

// Create the button

btn = new Button();

btn.setText("Click me please!");

btn.setOnAction(e -> buttonClick());

// Add the button to a layout pane

BorderPane pane = new BorderPane();

pane.setCenter(btn);

// Add the layout pane to a scene

Scene scene = new Scene(pane, 300, 250);

// Finalize and show the stage

primaryStage.setScene(scene);

primaryStage.setTitle("The Click Me App");

primaryStage.show();

}

To create the user interface for the Click Me program, the start

method performs the following four basic steps:

-

Create a button control named btn

. The button’s text is set to Click me please!

, and a method named buttonClick

will be called when the user clicks the button.

For a more detailed explanation of this code, see the sections “Creating a Button

” and “Handling an Action Event

” later in this chapter.

-

Create a layout pane named pane

and add the button to it.

For more details, see the section “Creating a Layout Pane

” later in this chapter.

-

Create a scene named scene

and add the layout pane to it.

For more details, see the “Making a Scene

” section later in this chapter.

-

Finalize the stage by setting the scene, setting the stage title, and showing the stage.

See the “Setting the Stage

” section later in this chapter for more details.

You find pertinent details of each of these blocks of code later in this chapter. But before I proceed, I want to point out a few additional salient details about the start

method:

-

The start

method is defined as an abstract method in the Application

class, so when you include a start

method in a JavaFX program, you’re actually overriding the abstract start

method.

Although it isn’t required, it’s always a good idea to include the @override

annotation to explicitly state that you’re overriding the start

method. If you omit this annotation and then make a mistake in spelling the method named (for example, Start

instead of start

) or if you list the parameters incorrectly, Java thinks you’re defining a new method instead of overriding the start

method.

Although it isn’t required, it’s always a good idea to include the @override

annotation to explicitly state that you’re overriding the start

method. If you omit this annotation and then make a mistake in spelling the method named (for example, Start

instead of start

) or if you list the parameters incorrectly, Java thinks you’re defining a new method instead of overriding the start

method.

- Unlike the main

method, the start

method is not a static method. When you call the launch

method from the static main

method, the launch

method creates an instance of your Application

class and then calls the start

method.

-

The start

method accepts one parameter: the Stage

object on which the application’s user interface will display. When the application calls your start

method, the application passes the main stage — known as the primary stage

— via the primaryStage

parameter. Thus, you can use the primaryStage

parameter later in the start

method to refer to the application’s stage.

Creating a Button

The button displayed by the Click Me program is created using a class named Button

. This class is one of many classes that you can use to create user interface controls. The Button

class and most of the other control classes are found in the package javafx.scene.control

.

To create a button, simply define a variable of type Button

and then call the Button

constructor like this:

Button btn;

btn = new Button();

In the code in Listing 1-1

, the btn

variable is declared as a class variable outside of the start

method but the Button

object is actually created within the start

method. Controls are often declared as class variables so that you can access them from any method defined within the class. As you discover in the following section (“Handling an Action Event

”), a separate method named buttonClicked

is called when the user clicks the button. By defining the btn

variable as a class variable, both the start

method and the buttonClicked

method have access to the button.

To set the text value displayed by the button, call the setText

method, passing the text to be displayed as a string:

btn.setText("Click me please!");

Here are a few additional tidbits about buttons:

- The Button

constructor allows you to pass the text to be displayed on the button as a parameter, as in this example:

Btn = new Button("Click me please!");

If you set the button’s text in this way, you don’t need to call the setTitle

method.

-

The Button

class is one of many classes that are derived from a parent class known as javafx.scene.control.Control

. Many other classes derive from this class, including Label

, TextField

, ComboBox

, CheckBox

, and RadioButton

.

The Button

class is one of many classes that are derived from a parent class known as javafx.scene.control.Control

. Many other classes derive from this class, including Label

, TextField

, ComboBox

, CheckBox

, and RadioButton

.

-

The Control

class is one of several different classes that are derived from higher-level parent class called javafx.scene.Node

. Node

is the base class of all user-interface elements that can be displayed in a scene. A control is a specific type of node, but there are other types of nodes. In other words, all controls are nodes, but not all nodes are controls. You can read more about several other types of nodes later in this minibook.

The Control

class is one of several different classes that are derived from higher-level parent class called javafx.scene.Node

. Node

is the base class of all user-interface elements that can be displayed in a scene. A control is a specific type of node, but there are other types of nodes. In other words, all controls are nodes, but not all nodes are controls. You can read more about several other types of nodes later in this minibook.

Handling an Action Event

When the user clicks a button, an action event

is triggered. Your program can respond to the event by providing an event handler,

which is simply a bit of code that will be executed whenever the event occurs. The Click Me program works by setting up an event handler for the button; the code for the event handler changes the text displayed on the button.

There are several ways to handle events in JavaFX. The most straightforward is to simply specify that a method be called whenever the event occurs and then provide the code to implement that method.

To specify the method to be called, you call the setOnAction

method of the button class. Here’s how it’s done in Listing 1-1

:

btn.setOnAction(e -> buttonClick());

If the syntax used here seems a little foreign, that’s because it uses a lambda expression

, which is a feature that was introduced into Java in version 1.8. As used in this example, there are three elements to this new syntax:

-

The argument e

represents an object of type ActionEvent

, which the program can use to get detailed information about the event.

The Click Me program ignores this argument, so you can ignore it too, at least for now.

The Click Me program ignores this argument, so you can ignore it too, at least for now.

- The arrow operator (->

) is a new operator introduced in Java 8 for use with Lambda expressions.

- The method call buttonClick()

simply calls the method named buttonClick

.

You’ll see more examples of Lambda expressions used to handle events in Chapter 2

of this minibook, and you can find a more complete discussion of Lambda expressions in Chapter 7

of Book 3.

After buttonClick

has been established as the method to call when the user clicks the button, the next step is to code the buttonClick

method. You find it near the bottom of Listing 1-1

:

public void buttonClick()

{

if (btn.getText() == "Click me please!")

{

btn.setText("You clicked me!");

}

else

{

btn.setText("Click me please!");

}

}

This method uses an if

statement to alternately change the text displayed by the button to either You clicked me!

or Click me please!

. In other words, if the button’s text is Click me please!

when the user clicks the button, the buttonClicked

method changes the text to You clicked me!

. Otherwise, the if

statement changes the button’s text back to Click me please!

.

The buttonClicked

method uses two methods of the Button

class to perform its work:

-

getText

:

Returns the text displayed by the button as a string

-

setText

:

Sets the text displayed by the button

For more information about handling events, see Chapter 2

of this minibook.

Creating a Layout Pane

By itself, a button is not very useful. You must actually display it on the screen for the user to be able to click it. And any realistic JavaFX program will have more than one control. The moment you add a second control to your user interface, you need a way to specify how the controls are positioned relative to one another.

For example, if your application has two buttons, do you want them to be stacked vertically, one above the other, or side by side?

That’s where layout panes come in. A layout pane

is a container class to which you can add one or more user-interface elements. The layout pane then determines exactly how to display those elements relative to each other.

To use a layout pane, you first create an instance of the pane. Then, you add one or more controls to the pane. When you do so, you can specify the details of how the controls will be arranged when the pane is displayed. After you add all the controls to the pane and arrange them just so, you add the pane to the scene.

JavaFX provides a total of eight distinct types of layout panes, all defined by classes in the package javafx.scene.layout

. The Click Me program uses a type of layout called a border pane,

which arranges the contents of the pane into five general regions: top, left, right, bottom, and center. The BorderPane

class is ideal for layouts in which you have elements such as a menu and toolbar at the top, a status bar at the bottom, optional task panes or toolbars on the left or right, and a main working area in the center of the screen.

The lines that create the border pane in the Click Me program are

BorderPane pane = new BorderPane();

pane.setCenter(btn);

Here, a variable of type BorderPane

is declared with the name pane

, and the BorderPane

constructor is called to create a new BorderPane

object. Then, the setCenter

method is used to display the button (btn)

in the center region of the pane.

Here are a few other interesting details about layout panes:

Making a Scene

After you create a layout pane that contains the controls you want to display, the next step is to create a scene that will display the layout pane. You can do that in a single line of code that declares a variable of type Scene

and calls the Scene

class constructor. Here’s how I did it in the Click Me program:

Scene scene = new Scene(pane, 300, 250);

The Scene

constructor accepts three arguments:

-

A node

object that represents the root node

to be displayed by the scene.

A scene can have only one root node, so the root node is usually a layout pane, which in turn contains other controls to be displayed. In the Click Me program, the root note is the border layout pane that contains the button.

- The width of the scene in pixels.

- The height of the scene in pixels.

Note:

If you omit the width and height, the scene will be sized automatically based on the size of the elements contained within the root node.

You can find out about some additional capabilities of the Scene

class in Chapter 3

of this minibook.

Setting the Stage

If the scene

represents the nodes (controls and layout panes) that are displayed by the application, the stage

represents the window in which the scene is displayed. When the JavaFX framework calls your application’s start

method, it passes you an instance of the Stage

class that represents the application’s primary stage — that is, the stage that represents the application’s main window. This reference is passed via the primaryStage

argument.

Having created your scene, you’re now ready to finalize the primary stage so that the scene can be displayed. To do that, you must do at least two things:

- Call the setScene

method of the primary stage to set the scene to be displayed.

-

Call the show

method of the primary stage to display the scene.

After you call the show

method, your application’s window becomes visible to the user and the user can then begin to interact with its controls.

It’s also customary to set the title displayed in the application’s title bar. You do that by calling the setTitle

method of the primary stage. The last three lines of the start

method for the Click Me application perform these functions:

primaryStage.setScene(scene);

primaryStage.setTitle("The Click Me App");

primaryStage.show();

When the last line calls the show

method, the Stage

displays — in other words, the window that was shown in Figure 2-1

displays onscreen.

You can read about additional capabilities of the Stage

class in Chapter 3

of this minibook.

Examining the Click Counter Program

Now that I’ve explained the details of every line of the Click Me program, I look at a slightly enhanced version of the Click Me program called the Click Counter program. In the original Click Me program that was shown earlier in this chapter (Listing 1-1

), the text displayed on the button changes when the user clicks the button. In the Click Counter program, an additional type of control called a label

displays the number of times the user has clicked the button.

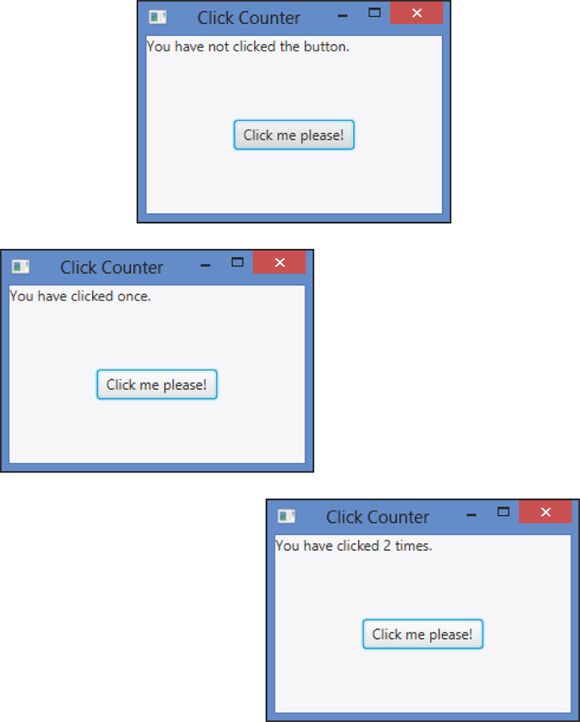

Figure 1-4

shows the Click Counter program in operation. The window at the top of this figure shows how the Click Counter program appears when you first start it. As you can see, the text label at the top of the window displays the text You have not clicked the button.

The second window shows what the program looks like after you click the button the first time. Here, the label reads You have clicked the button once.

When the button is clicked a second time, the label changes again, as shown in the third window. Here, the label reads You have clicked the button 2 times.

After that, the number displayed by the label updates each time you click the button to indicate how many times the button has been clicked.

Listing 1-2

shows the source code for the Click Counter program, and the following paragraphs describe the key points of how it works:

LISTING 1-2

The Click Counter Program

import javafx.application.*; →1

import javafx.stage.*;

import javafx.scene.*;

import javafx.scene.layout.*;

import javafx.scene.control.*;

public class ClickCounter extends Application →7

{

public static void main(String[] args) →9

{

launch(args); →11

}

Button btn; →14

Label lbl; →15

int iClickCount = 0; →16

@Override public void start(Stage primaryStage) →18

{

// Create the button

btn = new Button(); →21

btn.setText("Click me please!"); →22

btn.setOnAction(e -> buttonClick()); →23

// Create the Label

lbl = new Label(); →26

lbl.setText("You have not clicked the button."); →27

// Add the label and the button to a layout pane

BorderPane pane = new BorderPane(); →30

pane.setTop(lbl); →31

pane.setCenter(btn); →32

// Add the layout pane to a scene

Scene scene = new Scene(pane, 250, 150); →35

// Add the scene to the stage, set the title

// and show the stage

primaryStage.setScene(scene); →39

primaryStage.setTitle("Click Counter"); →40

primaryStage.show(); →41

}

public void buttonClick() →44

{

iClickCount++; →46

if (iClickCount == 1) →47

{

lbl.setText("You have clicked once."); →49

}

else

{

lbl.setText("You have clicked " →53

+ iClickCount + " times." );

}

}

}

The following paragraphs explain the key points of the Click Me program:

-

→1

The import

statements reference the javafx

packages that will be used by the Click me program.

-

→7

The ClickMe

class extends javafx.application.Application

, thus specifying that the ClickMe

class is a JavaFX application.

-

→9

As with any Java program, the main

method is the main entry point for all JavaFX programs.

-

→11

The main

method calls the launch

method, which is defined by the Application

class. The launch

method, in turn, creates an instance of the ClickMe

class and then calls the start

method.

-

→14

A variable named btn

of type javafx.scene.control.Button

is declared as a class variable. Variables representing JavaFX controls are commonly defined as class variables so that they can be accessed by any method in the class.

-

→15

A class variable named lbl

of type javafx.scene.control.Label

represents the Label

control so that it can be accessed from any method in the class.

-

→16

A class variable named iClickCount

will be used to keep track of the number of times the user clicks the button.

-

→18

The declaration of the start

method uses the @override

annotation, indicating that this method overrides the default start

method provided by the Application

class. The start

method accepts a parameter named primaryStage

, which represents the window in which the Click Me application will display its user interface.

-

→21

The start

method begins by creating a Button

object and assigning it to a variable named btn

.

-

→22

The button’s setText

method is called to set the text displayed by the button to Click Me Please!

.

-

→23

The setOnAction

is called to create an event handler for the button. Here, a Lambda expression is used to simply call the buttonClick

method whenever the user clicks the button.

-

→26

The constructor of the Label

class is called to create a new label.

-

→27

The label’s setText

method is called to set the initial text value of the label to You have not clicked the button.

.

-

→30

A border pane object is created by calling the constructor of the BorderPane

class, referencing the border pane via a variable named pane

. The border pane will be used to control the layout of the controls displayed on the screen.

-

→31

The border pane’s setTop

method is called to add the label to the top region of the border pane.

-

→32

The border pane’s setCenter

method is called to add the button to the center region of the border pane.

-

→35

A scene object is created by calling the constructor of the Scene

class, passing the border pane created in line 30 to the constructor to establish the border pane as the root node of the scene. In addition, the dimensions of the scene are set to 300 pixels in width and 250 pixels in height.

-

→39

The setScene

method of the primaryStage

is used to add the scene to the primary stage.

-

→40

The setTitle

method is used to set the text displayed in the primary stage’s title bar.

-

→41

The show

method is called to display the primary stage. When this line is executed, the window that was shown in Figure 2-1

displays on the screen and the user can begin to interact with the program.

-

→44

The buttonClick

method is called whenever the user clicks the button.

-

→46

The iClickCount

variable is incremented to indicate that the user has clicked the button.

-

→47

An if

statement is used to determine whether the button has been clicked one or more times.

-

→49

If the button has been clicked once, the label text is set to You have clicked once.

.

-

→53

Otherwise, the label text is set to a string that indicates how many times the button has been clicked.

That’s all there is to it. If you understand the details of how the Click Counter program works, you’re ready to move on to Chapter 3

. If you’re still struggling with a few points, I suggest you spend some time reviewing this chapter and experimenting with the Click Counter program in TextPad, Eclipse, or NetBeans.

The following paragraphs help clarify some of the key sticking points that might be tripping you up about the Click Counter program and JavaFX in general:

-

When does the program switch from static to non-static?

Like every Java program, the main entry point of a JavaFX program is the static main

method.

In most JavaFX programs, the static main

method does just one thing: It calls the launch

method to start the JavaFX portion of the program. The launch

method creates an instance of the ClickCounter

class and then calls the start

method. At that point, the program is no longer running in a static context because an instance of the ClickCounter

class has been created.

-

Where does the primaryStage

variable come from?

The primaryStage

variable is passed to the start

method when the launch

method calls the start

method. Thus, the start

method receives the primaryStage

variable as a parameter.

That’s why you won’t find a separate variable declaration for the primaryStage

variable.

That’s why you won’t find a separate variable declaration for the primaryStage

variable.

-

How does the ->

operator work?

The ->

operator is used to create what is known as a Lambda expression. Lambda expressions were introduced with Java 8 and are often used in situations that would’ve previously required an anonymous class. For more information, please refer to Chapter 7

of Book 3.

Getting a quick overview of what JavaFX is and what you can do with it

Getting a quick overview of what JavaFX is and what you can do with it

Looking at a basic JavaFX program

Looking at a basic JavaFX program

Importing the classes you need to create a JavaFX program

Importing the classes you need to create a JavaFX program

Creating a class that extends the JavaFX Application

class

Creating a class that extends the JavaFX Application

class

Using classes such as Button

, BorderPane

, and Scene

to create a user interface

Using classes such as Button

, BorderPane

, and Scene

to create a user interface

Create an event handler that will be called when the user clicks a button

Create an event handler that will be called when the user clicks a button

Examining an enhanced version of the Click Me program

Examining an enhanced version of the Click Me program

Prior to JavaFX, the main way to create GUIs in Java was through the Swing API. JavaFX is similar to Swing in many ways, so if you’ve ever used Swing to create a user interface for a Java program, you have a good head start at learning JavaFX.

Prior to JavaFX, the main way to create GUIs in Java was through the Swing API. JavaFX is similar to Swing in many ways, so if you’ve ever used Swing to create a user interface for a Java program, you have a good head start at learning JavaFX.

Although it isn’t required, it’s always a good idea to include the

Although it isn’t required, it’s always a good idea to include the