Leviticus

1. SACRIFICIAL WORSHIP(1:1–7:38)

According to Genesis, sacrificial worship and priesthood originated long before the Israelites departed Egypt (Gn 4:3–5; 8:20; 12:7–8; 13:4, 18; 14:18; 22:13; 31:54; 46:1). In Leviticus some earlier categories of sacrifice (burnt offerings and “sacrifices”) continue. Also continuing are a number of aspects of sacrifice, such as the need for invoking divine acceptance by a pleasing aroma, restriction of victims to animals and birds that were fit to eat, offering of fat portions, an element of substitution, and remedying sin. However, Leviticus incorporates some key differences affecting sacrificial worship. The Israelites are to transport a portable bronze altar with them and rely on priests, who are entitled to sacrificial portions, to officiate for them at a tabernacle that serves as the earthly residence of the deity.

A. Voluntary sacrifices (1:1–3:17). 1:1–2. Leviticus 1:1–2 introduces the first overall topic of the book in the style of case law: “When any of you brings an offering to the LORD . . .” (1:2). The first subcase, prescribing the burnt offering of herd animals (1:3–9), sets up a pattern of activities that must be performed if the offerer chooses to offer that kind of sacrifice. At strategic points the text indicates meanings or interpretations attached to the activities.

1:3–4. The offerer performs the first action of the burnt offering ritual proper by laying one hand on the head of the animal (1:4a). This gesture has no inherent meaning; however, the Lord attaches to it the meaning of ensuring that the animal is accepted on behalf of this particular person, who is transferring ownership of the victim to the Lord.

The sacrifice accepted by God will “make atonement” (Hb kipper) for this offerer (1:4b). The Hebrew word kipper signifies removing an impediment to the divine-human relationship by making amends through offering a sacrifice of “food” as a token payment of an obligation or “debt.” If the debt is for sin (rather than physical impurity; see below), reconciliation is completed by subsequent divine forgiveness. Thus, a priest who officiates a sin offering thereby makes atonement (kipper) on behalf of the offerer, meaning that the obligation regarding the sin is removed from the offerer, in order that the individual may be forgiven by God. Payment of debt for sin ransoms life (Lv 17:11; for kipper as “ransom,” see Ex 30:12, 15–16) because sin leads to death (cf. Rm 6:23).

1:5. Next, the offerer is to slay (slit the throat of) the bull (1:5a), and the priest dashes its blood around the sides of the altar, which is located at the entrance of the tent of meeting (1:5b). Explanation of this action, for which no precedent is recorded in Genesis, comes later, in Lv 17:11: the life of the flesh is (symbolically) in the blood, which the Lord gave to the people in order to make atonement for, or ransom (Hb kipper; see the CSB footnote at 17:11), their lives by having it applied to his altar (cf. Ex 12:7, 12–13, where Passover blood at dwelling entrances preserves lives).

1:6–9. Subsequent burnt offering activities are listed without explanation until the end of the unit provides the overall meaning or function of the ritual: the priest makes the burnt offering go up in smoke as a “fire offering [from the same Hebrew root as “incense”] of a pleasing aroma to the LORD” (1:9). So the altar is the means of access to the heavenly dwelling place of God (cf. Ps 11:4; 1 Kg 8:30). The Hebrew word for “fire offering” could include sacred offering portions that are not burned (Lv 24:9; Dt 18:1), and the term is never used for sin offerings, even though they are burned.

Sacrifices to the Lord were generally prepared as food gifts (Lv 3:11, 16; 21:6, 8; Nm 28:2). Use of food to signify or build a positive relationship with the deity was related to hospitality in which a person signified friendship by offering food to a guest, who could be a divine messenger (Gn 18; Jdg 6; 13). However, because the Lord does not need to consume food (Ps 50:13), he receives it in the form of smoke as a kind of incense. This interaction with the supernatural being makes the sacrificial system a kind of acted out prayer (cf. Rv 8:3–4).

1:10–17. Leviticus 1:10–13 continues instructions for burnt offerings by outlining the procedure if the victim will be a flock animal. Leviticus 1:14–17 prescribes the process if it is a domesticated bird, which a poor person could afford (cf. 5:7–13). The offerer simply hands the bird to the priest, so there is no need for a separate hand-laying gesture to clear up any potential ambiguity regarding the offerer’s identity.

Summary. In Lv 1, units of instruction are arranged in descending order of the cost of a burnt offering victim. Sacrifices of domesticated (never game) animals always represent financial cost (cf. 2 Sm 24:24), but Israelites could bring what they could afford. Offerings of the poor have no less value in God’s sight than more expensive gifts (cf. Mk 12:41–44).

Although animal sacrifices involved cost to those who offered them, they were only small tokens by which Israelites accepted God’s infinitely greater gift of ransom for their lives, which no human being could provide (Lv 17:11; Ps 49:7–9). God had provided the Israelites with all their property (Dt 8:18), and he graciously initiated sacrifice as the means of making amends with him. So sacrifices expressed faith in God’s free grace (cf. Eph 2:8–9).

Grace has come to ultimate fulfillment in Christ, who has given his lifeblood to ransom life (Mt 20:28; 26:28). Just as the burnt offering was consumed on the altar, Christ’s sacrifice consumed his human life (Heb 7:27; 1 Jn 3:16). Just as the smoke of the burnt (literally, “ascending”) offering ascended heavenward like incense to be accepted by God, Christ ascended to his Father immediately after his resurrection (Jn 20:17). Then he returned to be with his disciples for forty days, at the end of which they saw him taken up to heaven (Ac 1).

Grain offerings or incense would most likely be burned on an offering stand such as this one from Megiddo.

2:1–10. Leviticus 2 provides instructions for the grain offering. The Hebrew expression for “grain offering” here is a technical (more narrow) usage (2:3–5); in Gn 4 the same term refers to the vegetable and animal “offering” of Cain and of Abel (cf. Jdg 3:15, 17–18). Numbers 15 specifies that burnt offerings and “sacrifices” (i.e., sacrifices from which the offerers eat) always require accompanying grain and drink (wine) offerings. Along with the animal portions, these accompaniments complete the Lord’s “meal” (cf. Gn 18). A grain offering is a sacrifice—that is, an offering to the Lord for his utilization—even though it involves no death or blood (cf. Rm 12:1, “living sacrifice”).

Grain offerings consist of choice flour, with oil and frankincense (2:1), but are to be unleavened (2:4–5, 11). They can be presented in various forms (2:4–7), and there is a special subcategory for firstfruits of the harvest (2:14–16). The memorial portion is a handful containing some of the grain and oil but all of the frankincense (2:2, 16). A priest burns the Lord’s portion on the altar, and the remainder belongs to the priests (2:2–3, 9–10) as their commission for serving as God’s agents. So the priests eat from the Lord’s food, just as special servants and friends of a monarch or governor eat at his table (1 Sm 20:29; 2 Sm 9:7, 13; 1 Kg 2:7; 18:19; Neh 5:17; cf. 2 Kg 25:29–30; Dn 1:5).

2:11–16. Leviticus 2:11–13 gives the following rules regarding grain offerings that applied to all sacrifices. First, leaven and honey are excluded from the altar (2:11–12), presumably because leaven causes fermentation and honey is susceptible to fermentation. Fermentation was associated with decomposition and therefore death, which was antagonistic to the sphere of holiness and life. Paradoxically, the altar was “especially holy” (Ex 29:37), even though dead animals were placed on it. Such sacrificial death was uniquely necessary to ransom human life.

Second, sacrifices are salted in order to place them in the context of the permanent covenant with God (2:13; cf. Ezk 43:24 of salting animals). As a preservative, salt appropriately signifies the permanence of a covenant (Nm 18:19; 2 Ch 13:5).

3:1–15. Leviticus 3 outlines the fellowship offering. Unlike the burnt offering, the victim here can be female (3:1), only its suet (fat) goes up in smoke on the altar (3:3–4), the priest’s commission consists of edible portions (7:31–34), and the offerer eats the remainder (7:15–16). There are no fellowship offerings of birds because they are too small to be divided between the Lord, priests, and offerers.

Notice the progression of instructions for voluntary rituals from the burnt offering (none of which is to be eaten by a human; chap. 1) to the grain offering (from which only a priest can eat as his “agent’s commission”; chap. 2; cf. 7:9–10) to the fellowship offering (which is eaten by the offerer[s] as well as a priest; chap. 3; cf. 7:15–16, 31–36). The order is away from exclusive utilization by the Lord toward sharing with human beings. A shared meal expresses mutual goodwill and trust (cf. Gn 31:54).

3:16–17. Leviticus 3:16b–17 adds the general rule that all suet belongs to the Lord, and therefore the Israelites are never to eat it. Neither are they to eat blood—that is, meat from which the blood was not drained out at slaughter (cf. Gn 9:4). But the text avoids saying that blood belongs to the Lord; it never went up in smoke to him as part of his “food.”

Summary. Fellowship offerings were given to celebrate joyfully a healthy relationship with God (cf. Lv 7:12; 1 Sm 11:15) and did not serve to atone for specific sins. Nevertheless, they were still sacrifices carrying a basic element of ransom (Lv 17:11), which makes divine-human interaction possible in a fallen world. Even praise to God is made possible by sacrifice, without which we could have no access to God. Just as ancient Israelites ate meals shared with the Lord, Christians enjoy peace with God through Christ (Rm 5:1), who invites them to partake of him spiritually through his words (Jn 6:48–58, 63).

A reconstructed horned altar at Beer-sheba

B. Mandatory sacrifices as moral remedies (4:1–6:7). Two new kinds of mandatory sacrifices protect the holy sphere centered at God’s earthly residence. These are the sin and guilt offerings. The sin offering removes defilements caused by sins (4:1–5:13) and by physical conditions (chaps. 12–15) that can affect the state of the sanctuary (15:31; 16:16). The guilt offering remedies various kinds of sacrilege (5:14–6:7).

A guilt offering also remedies a sin of taking property, which carries a specific value. The sinner is required to make reparation before bringing a sacrifice by restoring what was taken from the wronged party (God or another Israelite), plus paying a penalty of one-fifth or 20 percent (5:16; 6:5), unless the offender does not know the nature of the sin (5:17–18). The sin offering lacks prior reparation, and only its suet is burned on the altar (unlike the burnt offering). However, it compensates by emphasizing blood, which represents ransom for life (Lv 17:11). In other sacrifices blood is dashed on the sides of the altar in the court, but sin-offering blood is applied higher and more prominently on the horns of the outer altar or of the golden incense altar in the outer sanctum (4:7, 18, 25, 30, 34).

4:1–35. The sin offering atones for or expiates moral faults involving violation of divine laws, so that the offerer can receive forgiveness (e.g., 4:20, 26, 31, 35). However, elsewhere the same kind of sacrifice also expiates in the sense of purifying the offerer from severe physical ritual impurities, which are not sins in the sense of moral faults and require no forgiveness (Lv 12:7–8; 14:19–20). The common denominator among physical impurities is association with mortality, the state resulting from sin (Rm 6:23).

In Lv 4, there are two main kinds of sin offerings. If the offerer is a chieftain or ordinary person, the priest is to daub the blood on the horns of the outer altar (4:25, 30, 34), burn the suet on the altar, and eat the remaining meat (6:26, 29). Sin-offering suet is not considered a food “gift” (contrast 3:3, 5, 9, 11 of the fellowship offering), apparently because it is a mandatory token fulfillment of an obligation or debt.

Sins of community-wide significance committed by the high priest (4:3–12) or the whole community (4:13–21) require the high priest to sprinkle blood seven times in the outer sanctum (in front of the inner veil), daub blood on the horns of the incense altar, and dispose of the remaining blood at the base of the outer altar (4:5–7). Blood is especially prominent in three ways: vertically on the altar horns, horizontally by coming closer to God’s place of enthronement in the most holy place (cf. Ex 25:22; Nm 7:89; 2 Sm 6:2), and by the fact that there are two applications of blood (not including disposal). The officiating high priest is also the offerer, or part of the offerer (when the community sinned), so he is not allowed to eat the meat, which is disposed of by incineration (4:11–12, 21).

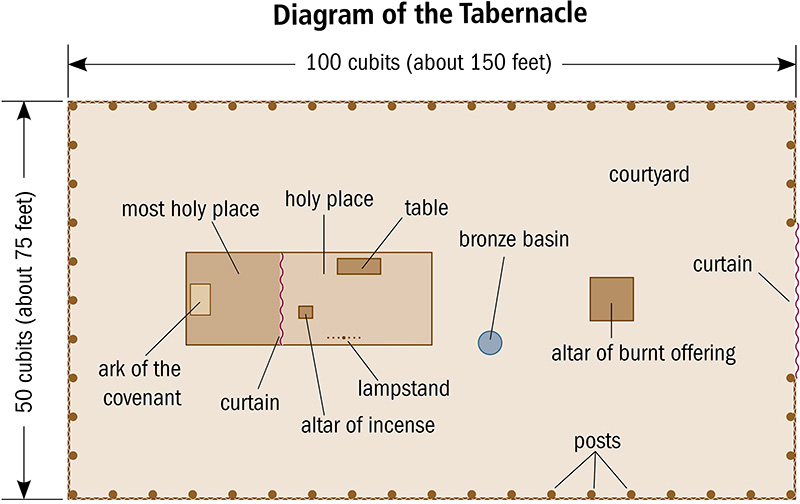

Diagram of the Tabernacle

Both kinds of sin offering have the same effect: to make atonement for the sinner from his or her sin—that is, to remove the guilt from the sinner, so that the person can be forgiven (Lv 4:26). The priest accomplishes atonement, but only God can forgive. Until he forgives, full reconciliation is not complete. When Jesus forgave like this, he claimed divinity (Mk 2:5–7).

5:1–13. Leviticus 5:1–13 continues the instructions for the offering of ordinary people that began in 4:27. Here sins remedied are not inadvertent but hidden, in that they involve deliberate neglect or forgetfulness (5:1–4). The sinner can perceive the need to bring a sacrifice only by realizing or experiencing guilt (5:2–5; cf. 4:22, 27), not by another person pointing out the fault (cf. 4:23, 28), because nobody else necessarily knew about it. One who becomes aware of a need for atonement is required to confess before bringing the sacrifice to the sanctuary (5:5). So the confession is not to a priest.

A sinner who cannot afford a flock animal is allowed to bring a less expensive sacrifice of two birds: one for a sin offering, supplemented by another for a burnt offering (5:7–10). The pair is functionally equivalent to the offering of a single flock animal. The offering is performed first because it is a token debt payment, which has to be taken care of before the burnt offering gift can be accepted.

An even poorer sinner is allowed to bring a sin offering consisting only of flour, without the oil or incense (5:11–13) that would have been included in a (nonexpiatory) grain offering (2:1). The ritual provides atonement, prerequisite to divine forgiveness, just like blood sacrifices (cf. Heb 9:22—almost everything is purified with blood). A substitute of grain (cf. Mt 26:26) was a concession so that not even the poorest sinner would be left behind.

In the NT, there is only one sacrifice for all kinds of sin: Christ’s sacrifice (Jn 1:29; Heb 9:28). Jesus is regularly identified as the sacrificial lamb whose blood purifies humanity from sin (Jn 1:36; Rm 8:3; 1 Co 5:7; Eph 5:2; 1 Pt 1:19; 1 Jn 1:7; Rv 5:6, 12; 7:14; 12:11; 13:8; cf. Heb 10:1–10). His sacrifice is considered a propitiation that turns away God’s wrath (Rm 3:25; 1 Jn 2:2).

5:14–6:7. Leviticus 5:14 introduces the guilt offering. The procedure itself is reserved for the additional instructions in 7:1–7. The guilt offering is for inadvertently misappropriating something sacred (5:14–16); the possibility of sacrilege, even when the cause of a sense of guilt is not known (5:17–19); and deliberately misusing God’s name in a false oath to defraud another person (6:1–7). The burnt offering already functioned as an expiatory sacrifice, so we can assume that it continued to remedy all the other expiable (nondefiant) cases that were not taken over by the sin and guilt offerings.

The guilt offering teaches several concepts: (1) Only after sinners make wrongs right to the best of their ability will God accept their sacrifices (cf. Mt 5:23–24). (2) It is not enough for sinners to put things right as best they can; they still need expiation provided by sacrifice (see Is 53:10—the messianic suffering servant is the ultimate “guilt offering”). (3) Divine forgiveness is available to those who are unable to identify their sins.

C. Additional instructions regarding sacrifices (6:8–7:38). The earlier basic instructions were for all Israelites (1:2; 4:2), but here the priests receive additional guidance regarding their role (6:9, 14, 20, 25). The unit on fellowship offerings, which were also eaten by the people, is logically reserved until the end (7:11–36).

6:8–13. Instructions regarding the burnt offering are concerned with ensuring that the sacred altar fire, lit by God himself (cf. 9:24), will never go out. The burnt offering is the basic, regular altar sacrifice that is to burn throughout each day and night (6:9; cf. Ex 29:38–42; Nm 28:1–8).

6:14–23. Leviticus 6:14–18 expands on the grain-offering procedure, specifying where (sanctuary court) the members of the priestly family (males) are to eat their most holy portions. Leviticus 6:19–23 prescribes a special, regular grain offering of each high priest as his personal tribute to God. He occupies a high position, but the Lord is his superior.

6:24–30. Leviticus 6:24–30 regulates allocation and eating of sin-offering meat. As with the grain offering, the meat is most holy (6:25), must be eaten in the sacred court (6:26), and conveys holiness (implying ownership by the sanctuary) to things by touch (6:27a), and the priest may not eat it if he also benefits from the same sacrifice as offerer (as when the blood is brought inside the tabernacle; 6:30; cf. 4:3–21).

Sin offerings are most holy, but their blood and meat are paradoxically treated as though they are contaminated: what they contact is to be washed or destroyed (6:27b–28; cf. 11:32–33, 35; Nm 31:20–23). This contamination can come only from the offerer, from whom it is removed, and it conveys to the altar residual pollution from sin or physical ritual impurity when blood from the same sacrifice is applied to the altar’s horns. This explains why special sin offerings are needed to remove such defilements from the sanctuary on the Day of Atonement (Lv 16:16).

In ancient Israel sin-offering blood served as a carrier agent to remove pollution, as in a living body. There was nothing wrong with the blood, which cleanses faulty people (cf. Heb 9:14; 1 Jn 1:7). Not only can expiation be regarded as removal of debt that stands between God and human beings (cf. Mt 6:12); it also cleanses from defilements that separate them from him (cf. 1 Jn 1:9). Amazingly, God makes himself vulnerable by allowing their pollutions to affect his holiness so that he can restore them (2 Co 5:21).

7:1–10. Leviticus 7:1–6 outlines the procedure of the guilt offering, which is similar to the sin offering, except that the blood is dashed on the sides of the outer altar. Its suet serves as a food “gift,” even though the sacrifice is mandatory, because it follows payment of reparation to the wronged party. Leviticus 7:7–10 specifies priestly ownership of guilt-offering meat and summarizes priestly agents’ commissions of the other sacrifices.

7:11–36. Leviticus 7:11–36 provides additional instructions for varieties of the fellowship offering, which the people are to eat. Anyone who (intentionally) violates the sanctity of a fellowship offering by eating its meat while impure incurs divine punishment (7:19–21), in keeping with the principle that interaction with the holy God requires purity (cf. Mt 5:8).

7:37–38. A summary at the end of chapter 7 lists sacrifices in the order of their presentation in 6:8–7:36 but looks ahead to chapter 8 by inserting the ordination offering before the fellowship offering (7:37). The ordination offering is similar to the fellowship offering in that it includes special grain accompaniments (8:26–28, 31; cf. 7:12–14) and the breast belongs to the officiant (8:29; cf. 7:30–31). [Sacrifices in the Old Testament]

2. ESTABLISHMENT OF RITUAL SYSTEM (8:1–10:20)

Chapters 8–10 describe a one-time event: founding the Israelite ritual system by consecrating and inaugurating its sanctuary and priesthood. Once this is done, regular and cyclical rituals will serve the Lord and maintain his presence at his earthly dwelling place (e.g., Ex 29:38–46; 30:7–8; Nm 28:1–29:40), and expiatory rituals will restore divine-human relationships when problems resulting from human faultiness arise (e.g., Lv 4:1–6:7).

A. Consecration of sanctuary and priests (8:1–36). 8:1–13. Leviticus 8 reports fulfillment of the divine instructions for the consecration service (Ex 29:1–44; 30:26–30). Special anointing oil (8:2; cf. Ex 30:22–33) conveys permanent holiness to objects and authorizes persons because God has given the oil that function as an extension of his presence (cf. Ex 29:43). Moses, the prophet (cf. Dt 18:15; 34:10), officiates at these sacrifices as temporary priest (Lv 8:14–32) in order to set up the permanent priesthood (8:4).

8:14–36. Sin and burnt offerings (8:14–21) prepare for the unique ordination offering (8:22–32). Although the sin offering is on behalf of the priests, it also purifies and further consecrates the outer altar (8:15; cf. Ex 29:36–37). Since the priests and altar are in the process of consecration, the sin offering does not leave a residue of defilement on the altar (contrast Lv 6:27).

The Hebrew term for the “ordination offering” (8:28, 31) refers to “filling” the hand (cf. Ex 28:41; 29:9)—that is, authorizing for a function. Moses daubs some blood on the right ears, thumbs, and big toes of the priests (8:23–24). This implies their commitment to ministry, as a life-and-death contract in blood, to hear and obey, do, and go according to the Lord’s will. Moses also takes some anointing oil and some blood that has been applied to the altar and sprinkles them on the priests and their vestments to consecrate them (8:30). Thus they are bonded to the Lord by blood (cf. Ex 24:6, 8). Their strict confinement to the sacred precincts during seven days of repeating the ordination sacrifices reinforces the fact that they now belong to the holy sphere as the Lord’s servants (8:33–35).

It is striking that both the outer altar and the priests are consecrated by anointing and with sacrificial blood (8:11–12, 15, 23–24, 30). From the Hebrew term for “anointed,” referring especially to the high priest (4:3, 5, 16; 6:22), comes the English word “messiah.” The prophesied Messiah (Dn 9:25–26) is Christ (from the Greek for “anointed one”), who has been consecrated as the heavenly High Priest (Heb 5:5–10). He qualified for that role through his own sacrificial blood (see Heb 13:10–12).

B. Inaugural priestly officiation and divine acceptance (9:1–24). 9:1–16. The final phase of establishing the ritual system is to initiate the priests by having them officiate their first sacrifices at the altar. Expiatory pairs of sin and burnt offerings are repeated, first for the priests (9:8–14) and again for the rest of the community (9:15–16).

The NT book of Hebrews describes Jesus as both high priest and the ultimate sacrifice. Whereas high priests such as Aaron had to sacrifice daily, “first for their own sins, then for those of the people,” Jesus the “holy, innocent, undefiled” High Priest accomplished this “once for all time when he offered himself” (Heb 7:26–27; cf. 9:6–14, 24–28; 10:1–18).

9:17–22. Although the priests are consecrated, they are still faulty human beings. So before they can mediate for their people, they need expiation for themselves (unlike Christ—Heb 7:26–27). Then Aaron performs grain and fellowship offerings (9:17–21) and blesses the people (9:22; cf. Nm 6:22–27). Sacrificial worship to the Lord and blessing people in his name go together.

9:23–24. Moses and Aaron enter the sacred tent, which is permitted only for authorized priests. The fact that Aaron emerges alive to bless the people again (with Moses) means that the Lord has accepted him as priest. This is confirmed by the appearance of the Lord’s glory at that moment (9:23). Then divine fire consumes the sacrifices that have started burning on the altar (9:24; cf. 1 Kg 18:38), overwhelming the people with evidence of divine favor and acceptance for their benefit.

C. Divine nonacceptance of inaugural ritual mistake (10:1–20). 10:1–3. Tragedy strikes before the priests have even finished their duties, such as eating their portions. Two sons of Aaron offer incense to the Lord with unauthorized fire in their firepans, rather than the divinely lit altar fire (10:1; cf. Lv 16:12). Thus they put human power in place of divine power, failing to glorify the Lord as holy (10:3). Ministering with kindling ignited by humans is unacceptable to God, and the same kind of divine fire that has favorably consumed the altar sacrifices now consumes Nadab and Abihu (10:2).

The Lord’s presence is an awesome force, like a nuclear reactor. His protocols had to be carried out to the letter if he were to dwell among faulty, mortal people without destroying them. Priestly failure in this regard could affect the safety and well-being of the people, both physically and in terms of their attitude toward God’s nature and character.

10:4–7. The surviving priests are sanctified, so they are forbidden to mourn (10:6–7, as in 21:10–12, at the strict standard for the high priest). Thus the God of Israel rejects death as evil and therefore alien to his holy nature, which his priests are to represent. This separation between holiness and death is in stark contrast to the religious culture of Egypt, where death was considered holy because it was the passage of the soul (which was immortal) to another phase of life.

10:8–11. In the middle of Lv 10 is a divine speech that prohibits the priests from entering the sacred tent while under the influence of alcohol (10:9) and summarizes the priestly roles of distinguishing between categories (holy and profane, impure and pure) and teaching the people all the Lord’s rules (10:10–11). Placement of the speech here could imply that Nadab and Abihu erred due to impaired judgment because they were intoxicated.

10:12–20. Moses reminds the surviving priests in detail regarding their portions of the inaugural sacrifices (10:12–15) to ensure that no more mistakes will derail the ritual system at the vulnerable moment of its inception. When he finds that they have already incinerated the remainder of the people’s sin offering, which they should have kept to eat (6:26, 29; unlike their own sin offering, which they correctly incinerated because it was on their behalf [9:11]), he is understandably furious (10:16–18).

Moses’s rebuke clarifies the role of priestly consumption of sin-offering meat: This is a privilege, but it is also a requirement; by consuming the meat, priests bear the culpabilities of the offerers as part of the mediatorial process of atoning for the offerers (10:17). Thus, priests participate in the role of God, who bears culpability (Ex 34:7) when he extends mercy to sinners. The fact that Christ bore the culpabilities for our sins as our priest and died for those sins as our sacrificial victim, combining the two roles in himself, proves that he died as our substitute. Moses accepts Aaron’s explanation that at this time of divine judgment on his family, he (with his surviving sons) did not feel worthy to partake of the sin offering meat (10:19–20).

3. IMPURITIES AND RITUAL REMEDIES(11:1–17:16)

A. Separating physical impurities from persons (11:1–15:33). Leviticus 11 picks up the themes of eating meat (10:12–20) and making category distinctions (10:10; cf. Dt 14:1–29) and addresses general dietary rules to all Israelites. The priests are especially consecrated as the Lord’s house servants, but all Israelites are holy in a wider sense. So they are to emulate the holiness of their God (11:44–45), from whom impurity is to be kept separate (cf. 7:20–21), by separating themselves from specified physical impurities (Lv 11–15). In chapter 11 this means abstaining from eating meat of creatures regarded by God as “unclean” in the sense of unfit to eat.

Some impurities are temporary and it is permitted to incur them, provided that proper purification is carried out, but an impure kind of creature is permanently prohibited as food. This impurity is not physical dirt, nor does the Bible indicate that an impure creature is not good for other things; indeed, all creatures were created “good” (Gn 1:20–25).

In Dn 1, Daniel risks his life to maintain his holiness by not defiling himself with a forbidden diet, even though he is far from the temple and the land of Israel, and God blesses him for his choice.

Leviticus 12–15 moves to physical ritual impurities that originate in human beings. These include healthy or unhealthy flows of blood from reproductive organs (Lv 12; 15), emissions of semen or unhealthy genital flows of other kinds (Lv 15; cf. Dt 23:10–11), and skin disease (Lv 13–14). Numbers 19 includes the impurity of corpse contamination.

These impurities are not mere physical dirtiness but conceptual categories excluded from contact with the sacred. Their common denominator is association with the birth-death cycle of mortality that results from sin (cf. Rm 5:12; 6:23). These rules and remedies do not apply to Christians, whose High Priest ministers in heaven (Heb 4:14–16; 8:1–2) rather than in an earthly temple. However, we can learn from them about human nature in relation to God. He is the Lord of life and does not want himself to be misrepresented as comfortable with death, which was never part of his ideal plan. He saves people from (not in) their mortality to give them eternal life (Jn 3:16).

11:1–47. Noah already knew the difference between clean and unclean animals (Gn 7:2, 8–9; 8:20), but Lv 11 enumerates the distinctions in detail within the broad categories of creatures inhabiting and moving in the different zones of planet Earth: land, air, and water (11:46; cf. Gn 1:1–31). There are simple criteria for recognizing clean land animals (split hooves and cud chewing, 11:3–7), water creatures (fins and scales, 11:9–12), and some edible kinds of insects (jointed legs to leap, 11:20–23). For birds there are no criteria; the text only lists the forbidden species (11:13–19). Among land-swarming creatures there is no distinction in terms of fitness for eating; all are unclean (11:29–31, 41–44).

Scholars have proposed possible reasons why a given creature should be permitted or prohibited for eating, such as dietary impact on human health, the need to teach respect for animal life, and reflection of the creation ideal of life, which excludes animals linked to death. However, the Bible never states such a rationale. God’s people are to obey his instructions simply because they trust him.

Some kinds of animal carcasses convey temporary impurity to persons who merely touch them (11:24–40). Of these, carcasses of some rodents and reptiles additionally defile any object that they contact (11:32–38). But there is a striking exception: they do not contaminate a water spring or cistern (11:36). This principle that a source of purity would not be defiled explains how Jesus is not defiled when he touches lepers or is touched by a woman with a hemorrhage and power goes forth from him to heal them (Lk 5:12–14; 8:43–48).

Regarding the categories of edible and inedible animals (not including any additional temporary impurities), Lv 11 only presents categorical permissions or prohibitions, without any ritual remedies. The fact that such basic dietary distinctions long preexisted Israel (Gn 7:2, 8) suggests that they are permanent and universal for God’s people, who are to emulate divine holiness (cf. 1 Pt 1:14–16; 2:9). [Cleanness]

12:1–8. Most ritual impurities originating in humans pertain to the birth-death cycle, so this section of Leviticus logically begins with the impurity of a woman who gives birth. This impurity arises from the genital flow of blood that normally follows birth (12:4). Birth of a girl keeps the mother impure twice as long as if she bears a son (12:5). The text does not explain the reason for this. At birth a girl may produce some vaginal discharge, which can include blood, so perhaps the mother also bears the child’s impurity in this case. Alternatively, perhaps the mother’s initial period of heaviest uncleanness is shortened to seven days (and therefore her subsequent purification from lighter impurity is proportionally shortened) if she has a boy so that she will not transmit impurity to him by contact (cf. 15:19) at or following the time of his circumcision on the eighth day (12:3; cf. Gn 17:12). But circumcision is to be performed at home rather than at the sanctuary, so it is unclear why such mitigation of impurity would be necessary.

The mother’s impurity is a serious one, lasting a week or more. Therefore, she is to complete the purification process by offering a pair of sacrifices: a burnt offering and a sin offering (12:6). As elsewhere, the sin offering is performed first, and the combination functions as a larger sin offering (cf. Lv 5:7–10; Nm 15:24, 27). A mother who cannot afford a sheep may bring a bird for the burnt offering (12:8; cf. Lv 1:14–17). This is what Mary offers after the birth of Jesus (Lk 2:24). Notice that women are allowed, and in some cases even commanded, to participate in sacrificial worship (cf. generic language in Lv 2:1; 4:27; 5:15).

A female’s need for purification does not devalue her as a human being. She is the source of precious new life, but through no fault of her own it is mortal life. So she needs only cleansing from her impurity (12:7–8), not forgiveness.

13:1–59. While Lv 12 concerns a healthy condition, chapters 13–14 give instructions for diagnosis of and ritual purification from an unhealthy state: skin or surface disease. In humans this complex of conditions, some of which resemble psoriasis, is not the same as modern leprosy (Hansen’s disease; see the article “Skin Disease in the Old Testament”). Analogous surface maladies could take the form of mold in garments (13:47–59) and fungus in walls of houses (14:34–53). [Skin Disease in the Old Testament]

For Leviticus the concern is not spread of the disease itself but that the disease makes persons, garments, or dwellings ritually impure; they therefore have to be kept separate from the holy realm until symptoms abate and they can be purified. Here ritual purification does not heal (unlike the miracle of Naaman; 2 Kg 5:14); it only follows healing.

Authoritative diagnosis of suspected skin disease and evaluation of its healing is left to experts: the priests (13:1–44). Symptoms, manifested by appearance, mainly involve discoloration of skin spots or hairs, or abnormal skin texture. Diagnosis of mold in garments of fabric or leather, worn over the skin, is analogous to that of skin disease (13:47–59).

The ritual impurity of surface disease was contagious, severe, and associated with death (Nm 12:12). So persons diagnosed with this condition are required to adopt the appearance of mourners, warn others of their presence (13:45), and dwell outside the Israelite camp in order not to defile it, because the holy God is in residence there (13:46; cf. Nm 5:2–3).

14:1–32. Leviticus 14 outlines ritual purification of persons if they are healed (14:1–32) and of houses if fungus abates (14:33–53). The section on houses includes some diagnostic criteria, but the unit is here because the emphasis is on purification. Houses, like garments, are closely connected with their owners, so the Lord’s concern for the purity of his people extends to them.

In Mt 8:4, when Jesus cleanses a man afflicted with leprosy and then tells him, “Show yourself to the priest, and offer the gift that Moses commanded,” he is referring to the instructions laid out in Lv 14.

Skin disease generates such potent impurity that purification requires several stages. Repeated pronouncements that the person is pure (14:8–9, 20) mean “pure enough for this stage.” Compare the way Jesus heals a blind man in stages so he can experience restoration as a process (Mk 8:22–25).

If a priest certifies that an individual is healed from skin disease (cf. Mt 8:4), a bird is slaughtered over “fresh” water (i.e., from a flowing source; 14:2–5). The priest then dips a live bird, together with cedar wood, red yarn, and hyssop, in the life liquid, consisting of the living water and the lifeblood of the slain bird (14:6). The priest sprinkles some of the life liquid on the person and sets the live bird free, representing departure of the impurity transferred to it (14:7; cf. 16:10, 21–22). Nothing is offered to God, so this is not a sacrifice, but it begins to transfer the person from impurity and death to purity and life.

After additional purification, the person is pure enough to enter the camp, but not one’s tent (14:8). By the eighth day, the individual is pure enough to offer sacrifices at the sanctuary (14:9–20). Apparently the guilt offering is for the possibility of sacrilege (cf. 5:17–19) because in some instances the “stroke” of skin disease could be perceived as coming from God (cf. 14:34; as divine punishment, see Nm 12:10; 2 Kg 5:27; 2 Ch 26:19–21).

There is striking similarity between use of oil and the blood of the special guilt offering on the extremities of the formerly skin-diseased person (14:25–29) and use of oil and blood in the consecration of the priests (8:12, 23–24, 30). The formerly skin-diseased person did not become holy as would a priest, but purification restored status among the holy people (broadly understood), who were eligible for limited contact with the holy sphere. This powerful enactment of return to purity and life would reassure those who had suffered not only physically but also from fear regarding their relationship with God.

14:33–57. Fungus in houses could be a problem in Canaan (14:33–53). As with garments, priestly diagnosis could have different results, depending on the behavior of the infestation. In Leviticus, though, it is priestly pronouncement, not mere presence of fungus, that makes a house and its contents impure. This reinforces the fact that impurity is a conceptual category.

Purification of a “cleaned” house involves a ritual that parallels the first-day purification of a person healed from skin disease (14:49–53; cf. 14:4–7). The idea that a dwelling can be purified by atonement to benefit its owner (14:53) paves the way for understanding purification of the Lord’s sanctuary on the Day of Atonement (Lv 16).

15:1–30. Leviticus 15 covers a variety of healthy and diseased genital discharges. It treats genital discharges of males and then females in chiastic order moving from abnormal male (15:2–15) to normal male (15:16–18) to normal female (15:18–24) to abnormal female (15:25–30). The transition from male to female is with sexual intercourse (15:18), which involves both genders. Genital flows could be involuntary (diseased discharges, nocturnal emission, menstruation) or voluntary (intercourse). Abnormal urethral discharge of males could be caused by a kind of gonorrhea (not modern venereal gonorrhea). In females, a chronic vaginal discharge of blood could result from a disorder of the uterus.

During the Second Temple period, bathing for ritual purity (as prescribed in Lv 15) often occurred in a mikvah, a ritual bath. The mikvah shown here was excavated near the southern wall of the Temple Mount in Jerusalem.

© Joe Goldberg / Wikimedia Commons, CC-by-sa-2.0.

Minor impurities lasting one day until evening require the remedy of bathing (15:16–18). More serious impurities lasting a week (menstruation) or more (abnormal flows) indirectly convey impurity by touch. Purification of a person healed from an abnormal or diseased discharge requires two stages: (1) waiting seven days plus ablutions and (2) sin and burnt offerings on the eighth day. Water and sacrifice, involving blood, are the agents of purification, with blood sacrifice providing the stronger remedy (cf. Jn 19:34; 1 Jn 5:6).

15:31–33. Near the end of chapter 15 is a concluding warning to separate the Israelites from their impurities so that they will not die when they defile the Lord’s sanctuary in their midst (15:31). This points ahead to chapter 16, which addresses the problem of the sanctuary’s defilement.

B. Separating defilement from sanctuary and community (16:1–34). 16:1–28. Once a year on the tenth day of the seventh month, called the Day of Atonement (23:27–28; 25:9), it is necessary for the high priest to purge the sanctuary of the evils that have reached it and accumulated there throughout the year. These evils consist of severe physical ritual impurities, expiable “sins,” and “rebellious acts” (16:16). The impurities and expiable sins affect the entire sanctuary when sin offerings that remove these evils from their offerers contact parts of the sanctuary.

Notice the part-for-all principle here, which also explains how blood on one part of an altar can affect the whole altar (cf. Lv 8:15; Ex 30:10), how daubing blood and oil on extremities can affect whole persons (Lv 8:23–24; 14:17–18), and how a whole animal from which part (blood) was taken into the sanctuary to purge it will absorb evils (16:27–28).

Indication of the way rebellious faults can defile the sanctuary comes later, in Lv 20:3 and Nm 19:13, 20. These egregious sins (worshiping Molech and wantonly neglecting to be purified from corpse contamination) automatically contaminate the sanctuary from a distance when they are committed. These sins must be removed from the sanctuary, but the remedy does not benefit the sinners themselves. Rather, they are condemned to the terminal divine penalty of being “cut off,” which denies them an afterlife.

Some scholars hold that every instance of sin or severe physical impurity automatically defiled the sanctuary so that the purpose of sin offerings throughout the year was to purge the sanctuary from these evils on behalf of the sinners. However, this kind of automatic defilement and sacrificial expiation to benefit the sinners were mutually exclusive: one who automatically defiled the sanctuary was terminally condemned, which meant that such a person had no opportunity to receive forgiveness through sacrifice (cf. Nm 15:30–31).

The high priest purges the sanctuary by applying the blood of a bull (on behalf of himself and his [priestly] household) and of the Lord’s goat (for the people) to each division of the sanctuary from the inside out, as we would expect for a housecleaning job (16:14–19). This process reverses the flow of defilements into the sanctuary that have occurred when sin offerings removed evils from their offerers at the sanctuary. The purgation procedure in the outer sanctum follows the pattern set in the inner sanctum (16:16; cf. 16:14–15), which means that the blood is applied once on the horns of the incense altar (cf. Ex 30:10) and seven times in front of it (reversing the order in Lv 4:6–7, 17–18).

The Day of Atonement sin offerings are supplemented by two burnt offerings for the same offerers: priests and people (16:24). After purging the sanctuary with blood, the high priest transfers the culpabilities and sins of Israel to a live goat by confessing while placing both hands on its head. Then he banishes the goat as a ritual garbage truck, sending Israel’s toxic moral waste to be dumped in the wilderness, and thereby permanently removing the moral faults of the Israelites from their camp (16:10, 21–22). [Azazel]

16:29–34. Throughout the year, Israelites received sacrificial expiation that either was prerequisite to forgiveness (4:20, 26, 31, 35) or purified them from physical ritual impurities (12:7–8; 14:19–20; 15:15, 30). But on the Day of Atonement, as a result of the sanctuary’s purification, people who have already been forgiven receive another kind of expiation that now purifies them from all their expiable sins (16:30). This is a second stage of expiation for the same sins, beyond forgiveness, which provides moral (rather than physical ritual) purification. No text dealing with the Day of Atonement (Lv 16; 23:26–32; Nm 29:7–11) mentions forgiveness from sin at all. While the high priest is cleansing the sanctuary through sacrifice for the people, those who have been loyal thus far are to reaffirm their loyalty to God by practicing self-denial (e.g., through fasting) and abstaining from work (16:29, 31) in order to receive the benefit of moral cleansing (16:30). [The Day of Atonement and God’s Justice]

C. Additional instructions regarding sacrifices and impurity (17:1–16). 17:1–9. Leviticus 17 serves as a transition. While it shares contents with earlier chapters, its style of exhortation, with emphasis on motivations and penalties, is characteristic of later chapters. The instructions in this chapter counter disloyalty to God by prohibiting Israelites from offering idolatrous sacrifices in the open country to male goats or goat-demons, with which the Israelites have committed (spiritual) promiscuity (17:5, 7; cf. 20:5; Ex 34:15; Dt 31:16). This material aptly follows instructions for the Day of Atonement since such illicit sacrifices appear related to (and perhaps a reaction to?) dispatch of a male goat into the wilderness (Lv 16:10, 21–22).

Leviticus 17 reinforces earlier instructions regarding the authorized place of sacrificial slaughter (17:1–9; cf. e.g., 1:3; 3:2), draining blood at slaughter (17:10–14; cf. 3:17; 7:26–27), and the need to purify oneself after eating a clean animal that dies without slaughter by a human (17:15–16; cf. 11:39–40). The main new element is the prohibition against slaughtering any sacrificeable kind of herd or flock animal without offering it as a sacrifice at the sanctuary. Any violator incurs bloodguilt for illicitly shedding blood, in this case of an animal that should have been offered to the Lord, and is condemned to the divine penalty of being “cut off” (17:3–4).

17:10–16. There is a close connection between the topics in this chapter. The blood now has to be drained out at the sanctuary to ensure that the Israelites do not eat meat with its blood. Blood contains life, so the Lord assigns it the function of ransoming human lives when it is applied to his altar (17:11). Thus, he provides a powerful rationale for not eating meat with its blood: respect for animal life and reverence for his blood ransom, without which people would perish (cf. Mt 20:28; 26:28; Heb 10:26–29).

The blood of a wild game animal is not assigned to the altar, but the moral principle of respect for life (cf. Ex 20:13) still applies (17:13–14). The prohibition of eating meat from which the blood is not drained at the time of slaughter goes back to God’s initial permission to eat meat in the days of Noah (Gn 9:4), long before Israel existed. Draining blood does not apply to animals that died in other ways, whether naturally or by predators, but an Israelite who eats such meat incurs ritual impurity (17:15–16).

In the NT, abstaining from blood (see Lv 17:14) and what has been strangled is treated as timeless moral law (with prohibitions against pollution from idols and immorality) that remains in effect for Gentile Christians (Ac 15:20, 29).

4. HOLY LIFESTYLE(18:1–27:34)

A. Holiness of people (18:1–20:27). Aspects of sexuality were introduced in chapters 12 and 15, where the focus was on separating remediable physical ritual impurity from the holy sphere centered at the sanctuary. Here the concern is with avoiding moral impurity (18:24, 30), for which there is no ritual remedy.

18:1–5. Leviticus 18 begins by explaining the purpose of the instructions that follow. God’s laws are good for his people, so by cause and effect, those who keep his laws can live (18:5). This means that his principles enable the people to live long in the land that he has given them (cf. Ex 20:12) rather than be expelled from it and die as the Canaanites do (Lv 18:24–30). This is not a legalistic approach to gaining eternal life through one’s own works. Gaining eternal life faces the problem that everyone has already sinned and the law is powerless to help those who have broken it (cf. Rm 3:19–26; Gl 3:10–14).

18:6–16. The remainder of chapter 18 forbids several kinds of sexual practices. Leviticus 18:6 states the general prohibition of incestuous sexual relations, which in Hebrew is euphemistically expressed in terms of approaching a blood relative to uncover nakedness. A blood relative obviously includes one’s full sister or daughter, who do not need to be mentioned, but 18:7–16 specifies other relations by blood or more indirectly through marriage to which the prohibition of incest applies or extends.

18:17–18. Leviticus 18:17–18 forbids sexual liaisons (including marriage) with two women who are related to each other: a woman and her daughter or granddaughter (18:17), and a woman as a rival in addition to her sister in a bigamous situation while the first wife is still alive (18:18). This reminds the reader of some biblical narratives recounting painful rivalries between wives, whether literal sisters (Gn 29–30) or not (1 Sm 1), in polygamous households. Although the prohibition of 18:18 in its context refers to literal sisters, it alludes to “sisters” in the extended sense of any two women, and thereby tends to discourage all polygamy.

18:19–20. Within the moral law context of chapter 18 is the prohibition against having sexual intercourse with a woman during her menstrual period (18:19; cf. Ezk 18:6, also within a moral context), implying that it too has ongoing application. According to Lv 20:18, the problem with such intercourse is that it exposes the woman’s source of blood through sexual activity, apparently showing disrespect for life.

Reiteration of one of the Ten Commandments in 18:20 (against adultery; cf. Ex 20:14) accords with the fact that the divine commands in Lv 18 regarding sexual lifestyle are categorical statements of moral principles. Neither the scope nor observance of these principles depends on the ancient Israelite cultural or ritual context. Therefore, these are timeless laws against immorality (cf. Ac 15:20, 29).

18:21–23. Prohibition of idolatrous and cruel worship of the god Molech (18:21) seems out of place here until we see the parallel with the law regarding adultery: just as you shall not (literally) give your penis for seed (or sperm) to your neighbor’s wife (18:20; cf. the CSB footnote), you shall not give of your seed (or offspring) to be presented to Molech. This recognizes the parallel between physical and spiritual adultery (disloyalty to God; cf. Lv 17:5, 7) and the close relationship between the sexual and religious practices of the Canaanites, which will later become a lethal snare to the Israelites (e.g., Nm 25).

The nontechnical language of 18:22 is unambiguous: for a man to sexually lie with another man as with a woman is abominable to God. Censured here is not simply homosexual tendency but acting on it. Also violating the creation order of sexual expression between one human male and female (Gn 2) is bestiality (18:23), which was well known in ancient times.

18:24–30. See the commentary on 18:1–5.

19:1–18. Leviticus 19 contains a remarkably diverse group of laws, mixing moral or ethical injunctions with religious or ritual instructions. Such a combination of categories is not found elsewhere in the ancient Near East, where religious and ethical laws are separated in different collections. This combination of ethics and religion in the Bible emphasizes that for God’s people, every aspect of life is holy and under his control. Thus, the heading in 19:2 calls for the Israelites to be holy as the Lord their God is holy, and the following laws teach them how to emulate his holy character (cf. 11:44–45) in the ways they interact with him and each other. The principle underlying all of God’s laws occurs at the end of the first half of the chapter: love for one’s fellow or neighbor (19:18). Near the end of the second half of the chapter, such love is extended to the resident alien (19:34).

There is a logical flow of topics in this chapter, although it is not immediately apparent. The first half of the chapter begins with the need to respect the human and divine parties involved in creating people (19:3): parents (mother first here; cf. Ex 20:12) and God, who rested (sabbathed) at creation (cf. Gn 2:2–3; Ex 20:8–11). Respect for God rules out unfaithfulness to him through idolatry (19:4; cf. Ex 20:3–6) or profaning a fellowship offering (19:5–8; cf. Lv 7:16–18). Another restriction on food that shows respect for God is to leave some of the harvest for disadvantaged people to glean (19:9–10). Such concern for others, especially the underprivileged, calls for honesty (19:11–14; cf. Ex 20:15–16), fairness (19:15–16; cf. Ex 20:13, 15–16), and love rather than hate (19:17–18).

Much of the legislation in chapter 19 reiterates or is related to principles of the Ten Commandments (Ex 20:3–17). The first nine commandments are clearly represented, and the principle of the tenth (against coveting; Ex 20:17) is implied behind laws against stealing, exploiting, and seeking to profit by another’s death. Notice that whereas Ex 20:16 is against harming someone by giving testimony (in court), the biblical law against lying in general is in 19:11.

God commanded the Israelites not to “turn to idols or make cast images of gods” (Lv 19:4), such as this bronze figurine representing the Canaanite god Baal.

A number of laws in Lv 19 have to do with basic ethics of kindness and decency (especially to vulnerable people) arising from unselfish love, which is the basic principle of all divine law and revelation (Mt 22:37–40). The fact that love can be commanded (19:18) shows that it is a principle, not only an emotion. Unlike human lawgivers, God can hold people accountable for such inner attitudes because his knowledge penetrates to thoughts (1 Kg 8:39; Pss 44:20–21; 94:11).

19:19–25. The second half of the chapter commences: “You are to keep my statutes” (19:19a; cf. 19:37). Again, topics begin with a connection to creation in terms of reproduction of animals and crops (from which come materials for garments), human beings, and new fruit trees (19:19b–25).

Rationales for some laws are not immediately apparent. Prohibitions of mixtures between kinds in animal breeding, sowing, or garments (19:19; cf. Dt 22:9, 11) seem to emphasize a distinction between the earthly sphere, in which each species generates life according to its kind, and the supramundane or holy sphere represented at the sanctuary, where mixtures can be appropriate (Ex 25:18–20; 26:1, 31; cf. cherubim in Ezk 1:5–12; 10:8–22). The connection between mixtures and holiness is reinforced by Dt 22:9, where sowing another crop in a vineyard results in the entire harvest becoming holy, which would mean that it is forfeited to the sanctuary. The earthly sanctuary and the temple that replaced it are now gone, so it appears that the need for maintaining such distinctions, at least with regard to mixed materials in garments, is no longer a divine requirement.

In ancient Israel, illicit sex with an engaged woman was treated as a form of adultery and was normally punishable by death to both parties if the woman consented and to the man alone if he raped her (Dt 22:23–27). However, in 19:20–22 the woman is a slave, lacking the right of consent that could make her culpable. Since the nature of the offense depends on the woman’s role, which in this case is ambiguous, the man also escapes capital punishment. However, he must offer a guilt offering because he has broken God’s moral law by committing sacrilege in the sense of violating the sanctity of the woman’s marriage, even before it is consummated (cf. Ex 20:14; Lv 6:1–7).

Following the prescribed treatment for new fruit trees (19:23–25) shows grateful acknowledgment of the Lord’s sovereignty over the land that he has provided. The horticultural practice of removing the buds of an immature tree rather than letting it prematurely produce edible fruit would also increase the yield (19:23).

19:26–29. Respect for the holy Creator also rules out eating meat over or with (life)blood (19:26a; cf. Gn 9:4; Lv 3:17; 7:26–27; 17:10–12), divination that seeks knowledge of the future apart from God (19:26b; cf. Ex 20:3), pagan mourning practices (19:27–28; cf. 21:5, 10), and defiling one’s daughter by making her a prostitute (19:29; cf. Ex 20:14).

A cluster of three laws prohibits doing certain things to one’s body: cutting side-growth of hair and beard, gashing oneself for the dead, and tattooing (19:27–28). Mention of “the dead” here reveals that these were pagan mourning practices involved in ancestor worship (cf. Dt 14:1–2; Jr 48:37; 1 Kg 18:28).

19:30–37. Continuing the theme of creation, 19:30 repeats, “Keep my Sabbaths” (cf. Ex 20:8–11), which first appeared at the beginning of the chapter after “Each of you is to respect [literally “fear”] his mother and his father” (19:3), but here in verse 30 is followed instead by, “And revere [“fear”] my sanctuary” (cf. 26:2). The sanctuary is the place of holiness and life where God’s presence resides, so it is associated with creation (cf. Ex 31:12–17, immediately following instructions for constructing the sanctuary).

Just as 19:4 forbids turning to idols, 19:31 prohibits turning to occult sources of knowledge, which includes the spirits of the dead. It is forbidden to pay attention to the dead (including ancestors) in that way, but elderly living persons should be treated respectfully (19:32, as in 19:14 regarding the handicapped). Concern for other people continues with loving the resident alien (19:33–34; cf. 19:9–10) and practicing honesty in business (19:35–36; cf. 19:11; Ex 20:15).

20:1–5. Leviticus 20 is a highly effective reinforcement of chapter 18, so that these two chapters frame chapter 19 in a unified section concerning Israelite lifestyle. However, chapter 20 also reiterates parts of chapter 19, so it serves as a fitting conclusion to the section as a whole. By contrast with the apodictic formulations (straightforward statements of principle: “You are to . . .” or “You are not to . . .”) of chapter 18, chapter 20 uses casuistic formulations to emphasize a variety of severe punishments: if a person does (offense), as a result that person will suffer (penalty).

Leviticus 18:21 briefly forbids Molech worship, but 20:1–5 places this case up front, adding stoning by the community plus the divine penalty of being “cut off.” Sympathizers are also to be “cut off.” The Molech worshiper loses the present life by stoning, and by “cutting off” he or she loses the life to come (cf. Mt 10:28). Being “cut off” is punishment for defiling the Lord’s holy sanctuary and profaning his holy name by giving of one’s offspring to Molech. This defilement occurs when the egregious cultic sin is committed (20:3; cf. Nm 19:13, 20). But the sinner has no opportunity for sacrificial expiation. There is no evidence here or anywhere else that expiable sins, which may be remedied through sin offerings, automatically defile the sanctuary like this when they are committed. Going astray after Molech is expressed metaphorically in terms of promiscuity (20:5), which helps to explain why Molech worship appears in chapters 18 and 20, with sexual offenses.

20:6–8. Another kind of “promiscuity” punishable by being “cut off” is to turn to occult sources of knowledge (20:6; cf. 19:31). The Israelites are to sanctify themselves (rather than defile themselves by idolatry and the occult) by keeping God’s laws because the (holy) Lord is their God (20:7–8; cf. 11:44–45; 19:2). They are able to do this because the Lord has made them holy (see also Ex 31:13; Lv 21:8; cf. Php 2:12–13).

20:9–21. In Lv 19, a call to holiness is followed by a command to revere parents (19:2–3). Similarly, in chapter 20 the call to holiness (20:7–8) is followed by the death penalty for cursing parents (20:9). Continuing the concern for family relationships, 20:10–21 reiterates a number of sexual laws presented in chapter 18, this time with penalties attached to each.

20:22–27. An exhortation (20:22–26) recapitulates the endings of chapters 18 and 19. The Lord has separated the Israelites from other peoples to be holy to himself, so they must separate between clean and unclean animals. The idea of separation links two themes: creation, in which the Lord separated elements (Gn 1:4, 6, 7, 14, 18), and separation or dedication of persons to holy service of God. As holy people, the Israelites are responsible for making some category distinctions (see Lv 10:10, of priests). By implication, members of the “kingdom of priests” and “holy nation” (Ex 19:6) serve as ambassadors of God’s creation order and its corresponding purity (cf. 1 Pt 2:9).

Peter quotes from Lv 11:44–45; 19:2; and 20:26 when he writes, “But as the one who called you is holy, you also are to be holy in all your conduct; for it is written, ‘Be holy, because I am holy’” (1 Pt 1:15–16).

B. Holiness of priests and offerings (21:1–22:33). 21:1–9. Priests are held to special standards in order to keep their holiness separate from impurities of various kinds. They are to properly represent God and not profane his name or reputation (21:6; 22:2).

Priests are forbidden to engage in pagan mourning practices (21:5; cf. 19:27–28) and prohibited from even participating in burying the dead and thereby incurring corpse contamination, except in the case of close blood relatives (21:1–4). Their holiness (21:8) prevents them from marrying women who have lost their virginity or been divorced (21:7). Thus the lives of priests are to model ideal life in order to portray the Lord’s holiness as ideal.

Family members of the Lord’s ministers are also responsible for protecting their reputations, which affects people’s perceptions of God. A priest’s promiscuous daughter profanes herself and thereby profanes her father, who is God’s representative (21:9).

21:10–15. The highest lifestyle standards apply to the specially anointed high priest, who is closest to God. He is prohibited from even approaching a corpse, with no exceptions (21:11; cf. Nm 6:6), and can marry only a virgin from his people (21:13–15).

21:16–22:7. Leviticus 21:16–23 continues the idea that the inner sphere of the Lord is as close to ideal life as possible by limiting the privilege of officiating sacrifices to priests without physical defects, just as sacrificial victims must be unblemished (1:3, 10; 22:17–25; cf. Heb 4:15—Christ as high priest is morally unblemished). However, a defective descendant of Aaron can eat sacred food (21:22). Nevertheless, physical ritual impurity disqualifies any of Aaron’s descendants from eating sacred food (22:1–7).

22:8–16. Priests are not allowed to incur impurity by eating meat from animals that died naturally or were killed by predators (22:8; contrast 17:15–16, of other Israelites). However, their dependents are authorized to share some kinds of holy meat (but not the most holy; 22:10–13).

22:17–30. Leviticus 22:17–25 lists permanent defects that disqualify animals from being given to God. The Hebrew word for “defect” is the same as that used for physical blemishes of priests (21:17–23). Again, the holy realm is ideal, and it would be an insult to the Lord to offer him a poor gift (Mal 1:6–14). Additional criteria for acceptable sacrifices, apparently based on respect for life, exclude an animal that is too young and slaughter of an animal and its young on the same day (22:26–28).

22:31–33. Chapter 22 ends with an exhortation. God has sanctified the Israelites by bringing them into a special relationship with himself. Correspondingly, they are to sanctify him by treating him as the source of holiness and by obeying him.

C. Holiness of time (23:1–44). The liturgical calendar in Lv 23 lists Israel’s special appointments with the Lord throughout the year, which are to be proclaimed as sacred occasions.

Leviticus 23 refers to annual festivals prescribed earlier (Ex 12:1–50; 23:14–17; 34:18, 22–23; Lv 16:1–34) and adds new instructions. It lists festivals in chronological order throughout the year, beginning with the first month in the spring. There are four festival occasions in the spring and four in the autumn, in the seventh month.

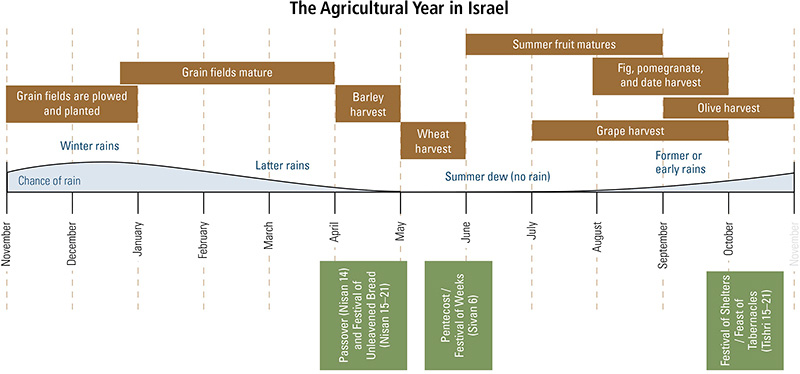

Each festival has a distinct character. Passover and Unleavened Bread commemorate the traumatic and glorious historical circumstances of Israel’s birth as a nation, when the Lord delivered his people from Egyptian bondage (cf. Ex 12–13). Several festivals joyfully celebrate God’s agricultural provision for his people through the stages of harvest from the beginning of the barley (Elevated Sheaf) and wheat (Weeks) harvests to completion of the harvest season (Shelters and Concluding Holiday).

23:1–8. Following the initial introduction (23:1–2) is a reminder to keep the seventh-day Sabbath (23:3), which is the foundation of all sacred time. Then a second introduction (23:4) precedes enumeration of annual festivals, thereby setting them apart from the weekly Sabbath. Weekly Sabbath rest is established for all inhabitants of planet Earth by the Lord’s example of celebrating his creation (Gn 2:2–3; cf. Mk 2:27), but the festivals are commemorations of God’s redemption, leading, and blessing in the history and agricultural life of the Israelite nation.

In addition to the weekly Sabbath, there are seven ceremonial days of rest that can occur on various days of the week (23:7–8, 21, 24, 27, 35–36). Six of them require only rest from laborious or occupational work. But the Day of Atonement is like the weekly Sabbath in that all work is excluded (23:27) so that God’s people can completely focus on him.

23:9–22. Timing of the festivals of the Elevated Sheaf and Weeks is based on the agricultural cycle rather than fixed dates. The Israelites are to bring a sheaf of the first grain harvested and give it to a priest as a firstfruits offering. At the sanctuary on the day after the next weekly Sabbath, the priest is to lift it in a gesture of dedication to the Lord (23:10–11), implicitly acknowledging the Lord’s ongoing creative power and thanking him. Counting from this day (including the first day), the Festival of Weeks (or Pentecost, in Ac 2:1; 20:16; 1 Co 16:8) comes on the day after the seventh Sabbath, that is, on the fiftieth day (23:15–16).

In the Second Temple period, it was assumed that the timing of the Elevated Sheaf was tied to the beginning of the Festival of Unleavened Bread. This raised a question regarding which there was fierce debate: Does “the day after the Sabbath” (23:11, 15) refer to the first weekly Sabbath after Passover or to the ceremonial Sabbath (partial rest day) at the beginning of Unleavened Bread (23:7)? The Sabbath between Jesus’s crucifixion as the ultimate Passover sacrifice (1 Co 5:7) and his resurrection as the firstfruits (1 Co 15:20) is described as a “special day” (Jn 19:31), meaning that the ceremonial and weekly Sabbaths happened to be the same day that year. So he was the fulfillment either way. [Holy Days and Celebrations]

23:23–32. A Festival of Trumpets, celebrated in the autumn on the seventh new moon, involves a reminder announced by a trumpet (or horn) signal (23:24). In Nm 23:21 the same Hebrew word for the signal refers to acclamation of the Lord as king in the war camp of his people (cf. Ps 47). This concept of divine kingship fits the context of the Festival of Trumpets: a reminder of the Lord’s sovereignty prepares his people for the great Day of Atonement ten days later, when he judges between his loyal and disloyal subjects (23:26–32).

23:33–44. Leviticus 23:37–38 concludes the liturgical calendar, but 23:39–43 adds further instructions regarding the Festival of Shelters to give it a dimension of historical commemoration. Temporary shelters, or booths, reenact the period when the Lord provided for his people during their wilderness journey (23:40–43). So when they enjoy the bounty of the land, they are to remember that it is a gift from God.

D. Holiness of light and bread (24:1–9). In addition to cyclical festivals observed by all Israelites, regular rituals are to be performed by the priests, as the Lord’s house servants, in the outer sanctum of his sanctuary. These rituals include arranging the lamps to provide light every day and placing bread on the golden table every Sabbath. This passage returns to the Sabbath, where chapter 23 began.

24:1–4. Leviticus 24:1–4 reiterates Ex 27:20–21, where the Lord commands the Israelites to provide olive oil for the lamps to burn from evening until morning (cf. Ex 25:37; 30:7–8). The fact that his light is on throughout each night implies that he stays awake to guard Israel (Ps 121:4). The sanctuary is his palace, but he is no ordinary monarch.

24:5–9. Exodus 25:30 mentions that special “Bread of the Presence” is to be regularly placed before the Lord’s presence on the golden table. Leviticus 24:5–9 provides the details, including twelve loaves (one for each Israelite tribe), two arrangements or piles, frankincense on each pile, and changing the bread every Sabbath to signify an eternal covenant between the Israelites (twelve tribes) and the Lord.

Other ancient Near Eastern peoples fed their gods twice per day, but Israel’s deity needed no human food, even once a week, for his own utilization (Ps 50:12–13). Bread was offered to him, but he retained only the incense as a token portion (24:7) and gave all the bread to his priests (24:9). The covenant bread was renewed on the Sabbath (24:8), which itself was an eternal covenant and sign between the Lord and his people to commemorate his creation (Ex 31:12–17). So the Israelites did not feed God but placed bread or basic food before him to acknowledge their dependence on him as their ongoing Creator and Provider in residence (cf. Ps 145:15–16; Dn 5:23).

E. Holiness of God’s name, and the taking of human and animal life (24:10–23). This passage, like the narrative in Lv 10, recounts failure by a member of the community that led to his death. This time it is an ordinary person who brawled and blasphemed. So his case becomes the occasion for additional divine legislation regarding blasphemy and assault.

Light and bread are powerful symbols of the Lord’s care for the Israelites. In the NT, Christ fulfills these roles for all people as “the light of the world” (Jn 8:12; 9:5) and “the bread of life” (Jn 6:35, 48; cf. 6:51). He also provides for eternal life through the breaking of his body, the new covenant bread (Jn 6:51; Lk 22:19).

24:10–14. The blasphemer is the son of an Israelite woman and an Egyptian man (24:10). So it appears that he belongs to the “mixed crowd” that left Egypt with the Israelites (Ex 12:38). The identity of his mother is more important than that of his father. She is Shelomith, daughter of Dibri, of the tribe of Dan (24:11). Ironically, the name Shelomith is from the same Hebrew root as the noun for “well-being” or “peace” and the verb for “make restitution” (see Lv 24:18, 21); Dibri is from the same root as the verb “speak” and the noun “word”; and Dan is derived from the verb “judge” (Gn 30:6). An Israelite hearing this story would understand that the mother’s identity summarizes the situation: Her son is judged for disturbing the peace and for speaking against God.

The half-Israelite man “went out” among the Israelites (24:10; see the CSB footnote), implying that he initiated the altercation when he entered the encampment of the full Israelites. In anger he blasphemously pronounced “the Name”—that is, the sacred personal name of Israel’s deity (Hb yhwh, usually translated “the LORD”)—and cursed (24:11). The fact that the ensuing legislation deals with anyone who curses God (24:15) suggests that the blasphemer’s curse was against the Lord himself, in violation of Ex 22:28. Since a curse was regarded as a kind of weapon, he has assaulted God.

Model of the table of the Bread of the Presence from the tabernacle replica at the Timna Valley Park, Israel

The blasphemer has broken the third of the Ten Commandments by taking God’s name in vain (Ex 20:7) and has assaulted God and man. Therefore, the Lord directs that the Israelites stone him outside the camp, after those who hear his utterance lay their hands on his head as a symbolic action (24:14), apparently to return evil back to its source (cf. 16:21) so that the originator will bear punishment for his own sin (cf. 24:15).

24:15–23. Leviticus 24:15–22, between the death sentence (24:14) and its fulfillment (24:23), specifies penalties for anyone who commits similar crimes. Assault on a person resulting in a permanent physical defect (the Hebrew word is the same as for defects disqualifying priests and sacrificial animals in Lv 21–22) is punishable by pure retaliatory justice (cf. Ex 21:23–25; Dt 19:19–21). The penalty is so severe because inflicting permanent disfigurement is a kind of sacrilege that diminishes the sacred life of a person made in the image of God (cf. Gn 9:6) who belongs to a “kingdom of priests” and a “holy nation” (Ex 19:6).

In its time the principle of retaliation advanced justice by ruling out disproportionate revenge (cf. Gn 4:23–24) and by mandating equal-opportunity punishment among various social and economic classes (24:20). Christians know about retaliation from the words of Jesus (Mt 5:38–39). Jesus did not repeal the penalties of the law in their judicial contexts; rather, he spoke against personal application of retaliation and advocated a higher ideal: waging peace in the face of adversity.

F. Holiness of promised land (25:1–55). 25:1–7. This chapter continues the theme of Sabbath, which is prominent in chapters 23 and 24, by prescribing rest for the promised land. Analogous to the weekly Sabbath, sabbatical rest for the land is to occur every seventh year (25:1–7; introduced in Ex 23:10–11). Such a year is a sacred time when the land will revert to its natural state and everyone will live off whatever the land produces by itself. This implies a regular exercise of faith: the Israelites need to depend on their Creator to provide enough food.

25:8–12. Leviticus 25:8–55 introduces a super-Sabbath for the land and its inhabitants: the Jubilee year. After seven sabbatical years, totaling forty-nine years, the Jubilee year comes every fiftieth year (cf. timing of the Festival of Weeks in 23:15–16). So the Jubilee follows the seventh sabbatical year and coincides with the first year of the following sabbatical-year cycle. Thus, there are two fallow years in a row. Consequently, the Israelites have to rely on the divine blessing of a bumper crop in the year before the fallow begins (25:20–22; cf. Ex 16:5, 22, 29).

The Israelite calendar year began in the spring (Ex 12:2), and the religious climax in the autumn began on the first day of the seventh month (Lv 23:24—with a trumpet signal), which has become the Jewish New Year (Rosh Hashanah). However, Leviticus dictates that commencement of the Jubilee year is signaled by trumpet, or horn, blasts on the Day of Atonement, the tenth day of the seventh month (25:9). The name Jubilee (25:10) comes from a Hebrew word for “ram” (yobel), an animal that provided horns to blow for signals (Jos 6:4–6, 8, 13; cf. Ex 19:13).

25:13–38. The Jubilee provided release of two kinds: return of ancestral agricultural land to its original owners (25:13–38) and release of persons from servitude (25:39–55). Israelites could lose their inherited property and freedom due to poverty, which could result from a factor such as crop failure. Once a farmer sold his land for living expenses or to pay off debt, if he had no relative to redeem the property for him (25:24–34), he would no longer have the means to support himself in his agrarian society and could be constrained to voluntarily sell himself and his family members into servitude so that they could survive (25:39–41). Servitude could seize him involuntarily if he defaulted on a loan, for which he and his dependents were collateral (cf. 2 Kg 4:1).

25:39–55. Deuteronomy 15:1–2 calls for remission of debts at the end of every seven years, which would reduce the incidence of debt slavery. Exodus 21:2 and Dt 15:12 mandate release of Israelite slaves after six years. But how would such persons independently support themselves after they regained their freedom? Leviticus 25 provides the solution: A servant can be retained up to a maximum of forty-nine years, but with a higher standard of living like that of a hired worker (25:39–43). The servant is released in the Jubilee year, when he regains his land, on which he can support himself and his family. Such servitude would be far from ideal, but it would sustain life until a farmer had the opportunity to begin again.

Summary. While modern Westerners cannot observe the Jubilee legislation as such because we lack the systems of ancestral land ownership and debt servitude that it regulates, we can learn much from Lv 25 about our responsibility to treat the poor and our workers with kindness. The Lord forbids taking advantage of people in economic distress (see 25:36–37, prohibiting charge of interest). If we would remember that we owe everything we have to God and are his tenants (cf. 25:23, 38), our generosity would contribute to alleviating poverty.

G. Covenant blessings and curses (26:1–46). 26:1–2. Leviticus 26:1–2 recalls the first laws in chapter 19 (19:3–4, regarding parents, Sabbath, and idolatry), but in reverse order and with revering the Lord’s sanctuary in place of revering one’s mother and father (as in 19:30). This chiasm frames the intervening chapters, containing a wide variety of laws governing many aspects of life. So when 26:3 refers to keeping God’s laws as the condition for enjoying the covenant blessings, the whole collection of divine statutes is in view. Repetition of two of the Ten Commandments at the outset in verses 1–2—against idolatry and for keeping the Lord’s Sabbath—is significant. Obeying these commands is crucial for showing loyalty to God.

Leviticus 26 is very similar to Dt 28. In both passages Israel is presented with two options: obedience, resulting in blessings, or disobedience, resulting in curses.