Numbers

1. PREPARATIONS FOR RESUMING THE JOURNEY (1:1–10:10)

A. Military organization (1:1–2:34). Preparation for completing the trip to Canaan and conquering that land requires organization of the Israelites as a sacred fighting force. This process includes a military census (Nm 1), arrangement of tribes in a holy war camp and assignment of their marching order (Nm 2), as well as a census of sanctuary personnel (members of the Levite tribe) and allocation of their duties (Nm 3–4).

1:1–54. The military census numbers able-bodied adult males along tribal lines, implying that military divisions correspond to tribes and their subunits. Organizing the army in this way would have had two major advantages. First, tribal hierarchy supplied a naturally effective military chain of command. Second, Israelites fighting alongside members of their extended families would have a strong vested interest in supporting each other.

Twenty years old and upward (with no upper limit) is considered fighting age (1:3, 18, 45). Compare Lv 27, the previous chapter of the Pentateuch, which places a premium on the valuation of males twenty to sixty years of age, based on their capacity for work benefiting the sanctuary (1:3).

Following a tally of men in each tribe, except for Levi, the grand total is 603,550 (1:46). If we add younger and infirm males, the tribe of Levi (22,000 aged a month old and upward; Nm 3:39), the “mixed crowd” that left Egypt with the Israelites (Ex 12:38), and a corresponding number of females, the total population under the leadership of Moses could easily be between two and three million. [How Accurate Are the Census Figures in Numbers?]

2:1–34. Numbers 2 arranges twelve tribes (not including Levites) in four major divisions, consisting of three tribes each. The Israelite war camp has the shape of a hollow square, with the residence of the divine king protected in the middle.

Including the Levites, there are thirteen tribes descended from the twelve sons of Israel (formerly Jacob). There are thirteen because Jacob granted Joseph a double inheritance by adopting his two sons, Ephraim and Manasseh, who each became a tribe (2:18–21; see Gn 48). The Levite tribe is to camp inside the hollow square, around the sanctuary, in order to guard its sanctity and thereby protect the Israelites from an outbreak of divine retribution (2:17; cf. 1:53; 3:23, 29, 35). Moses, with Aaron and his priestly family, camps in front of the sanctuary’s entrance in order to guard its most vulnerable point. Any nonpriest who presumes to usurp priestly function is to be put to death (3:38).

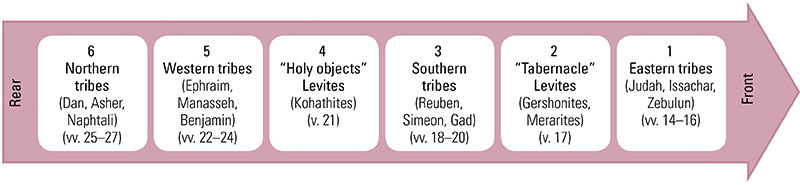

Positions of the Encamped Tribes

When the Israelites traveled, the Levites were responsible for taking down, transporting, and setting up the tabernacle (Nm 1:50–51; 2:17; 4:1–33). Exodus 39:32–40:8 lists the many furnishings and articles for the tabernacle and summarizes what was involved with setting it all up.

B. Organization of sanctuary personnel (3:1–4:49). The Levite tribe (including priests) is not included in the military census, because it is responsible for taking care of the Lord’s sanctuary (1:47–53; 2:33). Nonpriestly Levites are to serve as assistants to the priests. In addition to the regular care and guarding of the sanctuary and its contents, the Levites are responsible for packing up, transporting, and reassembling the tabernacle when the Israelites journey from one place to another. [Aaron]

The Levites belonging to the three subdivisions of their tribe are counted in two censuses. The first reports 22,000 Levite males at least a month old (3:14–39). A census of the firstborn males, a month old and upward, from other tribes yields a total of 22,273 (3:40–43). These reports are placed together because the Levites have been chosen to serve God’s sanctuary, and as such they redeem and replace the firstborn males of the other tribes (3:44). The second census of the Levites numbers mature males at the prime of life from thirty to fifty years of age, preliminary to organizing them as the sanctuary workforce (4:1–49).

The Lord claimed the firstborn males when he saved them from destruction of the firstborn in Egypt, but they are to be redeemed rather than sacrificed as firstborn animals are (Ex 12:29; 13:2, 12–15; 22:29; 34:20; Nm 8:17). Instead of using the firstborn of the various tribes as his priests and their assistants, God transfers this privilege to the Levites because of the loyalty they showed by executing apostate Israelites at the time of the golden calf incident (Ex 32:25–29; Dt 10:8). By substituting for the firstborn, the Levites redeem them by substitution (cf. Nm 35:25, 28, 32), but the 273 firstborn over the number of Levites have to be redeemed with five shekels apiece (3:45–51).

C. Laws and blessing for purity and holiness (5:1–6:27). The Israelite camp is sanctified by the presence of the Lord’s sanctuary in its midst. Therefore, the community within the camp is to be ritually and ethically pure.

5:1–4. Males or females with severe physical ritual impurities are required to stay outside the camp so that they will not defile its sphere of holiness that surrounds the sanctuary (5:3). This is no ordinary public health quarantine. Leviticus 13:46 already commanded that individuals afflicted by skin disease are to dwell apart. But exclusion of persons contaminated by genital discharges and corpses (5:2) goes beyond the rules in Lv 15 and Nm 19 because life in the sacred war camp demands a standard that is higher than usual.

5:5–10. Numbers 5:5–10 continues the theme of solving problems that males or females cause with regard to the sacred realm. However, this passage turns to a topic of deliberate ethical sin: men or women wronging other persons through unfaithfulness or sacrilege against the Lord (by taking false oaths; 5:6; cf. Lv 6:2–3). This topic was already treated in Lv 6:1–7, dealing with cases remedied by guilt offerings. But Nm 5 adds the requirement of confession (5:7; cf. Lv 5:5 for other sins that are not simply inadvertent) and provision to pay reparation to a priest if the wronged person dies and has no kinsman to whom it can be given (5:8–10).

5:11–31. Thus far, supplementary instructions in 5:1–4 and 5:5–10 serve as potent reminders (in reverse, chiastic order) of the entire systems regulating physical ritual impurities from human sources (Lv 12–15) and expiation for moral faults (Lv 4:1–6:7). The next law (Nm 5:11–31) picks up the factors of men and women, impurity, the moral fault of unfaithfulness, and giving something to a priest. This time the case involves the possibility that a woman becomes ritually impure by having sexual intercourse (cf. Lv 15:18) with the wrong man, thereby committing unfaithfulness against her husband. A husband suspecting that adultery has occurred, even though witnesses are lacking, is to bring her to the sanctuary (5:12–15).

In biblical law, this is the only kind of case in which the Lord himself renders the verdict at his sanctuary through a ritual procedure. The Lord’s verdict is revealed by the presence or absence of punishment. If a woman is guilty, her punishment will fit the crime by afflicting her sexual organs and making her sterile (5:16–28).

God does not entrust such a case to a regular Israelite court, which would have been all male in that society. Men naturally would have tended to sympathize with a suspicious husband, which meant that an innocent woman could have difficulty obtaining a fair hearing and could be unjustly condemned to death (cf. Lv 20:10; Dt 22:22). Only women needed this level of protection, which explains why there is no corresponding law for a suspected adulterer.

The ritual procedure is a kind of litmus test in which the woman takes into her body a holy substance, holy water, the sacredness of which is enhanced by adding some dust from the earthen floor of the holy tabernacle. It is a basic principle of the sanctuary and its ritual system that holiness is compatible with purity but antagonistic to impurity (cf. Lv 7:20–21). So if a morally pure woman drinks the holy water, there will be no problem. But if she is guilty of adultery, combining holiness with her moral impurity will cause a destructive physical reaction with a permanent effect worse than wearing a scarlet letter A for “Adultery.”

An innocent woman vindicated in this way by the all-seeing Lord himself would be completely freed from any social stigma of suspicion. Her husband could enjoy full confidence that she was faithful, and their marriage could be healed. A less potent ceremony would not have the same effect. (Compare parallels in Lk 7:37–50, but Jesus forgave a woman rather than vindicating her.)

6:1–8. The next law in Numbers, regarding temporary Nazirites (6:1–21), continues the theme of holiness versus impurity, involving factors such as treatment of hair, binding speech, and drinking (or not). Any Israelite man or woman could voluntarily take a special Nazirite vow of separation in order to be holy to the Lord for a period of time that he or she would specify. A holy lifestyle during the period of dedication would include abstaining from drinking intoxicating beverages or consuming any grape products, letting one’s hair grow without cutting it, and avoiding the severe physical ritual impurity of corpse contamination (6:3–8).

In Jdg 13 God tells Samson’s mother that her son will be a Nazirite “from birth until the day of his death,” and even from conception, since she is restricted from consuming anything alcoholic or unclean during her pregnancy (Jdg 13:7; cf. Nm 6:3–4). Samson, however, breaks every one of his vows, culminating in the cutting of his hair (Jdg 16:16–20; cf. Nm 6:5).

Through the Nazirite vow, the Lord makes it possible for nonpriestly Israelites to enjoy a high level of sanctity connected to himself. In terms of holy lifestyle, priests were prohibited from imbibing wine or other fermented drinks only when they entered the sanctuary (Lv 10:8–11). But such beverages are prohibited at all times to Nazirites (6:3), whose standard in this regard is higher. Ordinary priests were permitted to become impure by participating in burial of their closest relatives (Lv 21:1–4). But the holiness of Nazirites is like that of the high priest in barring them from going near any corpse at all (6:6–7; cf. Lv 21:11).

6:9–12. Nazirites, then, avoid corpse contamination, but people could suddenly die near them. Although this prohibited defilement would be incurred inadvertently, it would abruptly abort the period of Naziriteship. Therefore, the (now former) Nazirite is to undergo purification for corpse contamination (cf. Nm 19:11–19) and shave his or her defiled hair on the seventh day (6:9).

On the eighth day, the person is to bring a pair of sacrifices to the sanctuary (sin offering and burnt offering) to receive atonement for the inadvertent sin of violating the prohibition (6:10–11). In addition, a guilt offering expiated for inadvertent sacrilege: depriving the Lord of the remaining days of the vow and the dedicated hair that was to grow during that period (6:12; cf. Lv 5:14–16). Having rededicated his or her head (of hair) and the same duration of separation as before, the Nazirite begins the vowed period of time all over again (6:11–12). God takes seriously a person’s commitment to spend special time with him!

6:13–21. An Israelite who successfully completes the Nazirite period is to culminate his or her sacred dedication through a special group of rituals. First is a pair of sacrifices, listed as a burnt offering and a sin offering (6:14; cf. Lv 12:6, 8). However, the sin offering is actually performed first (6:16; cf. Lv 9:7–16, 22). This sin offering has puzzled scholars. Elsewhere in the Israelite sacrificial system, this kind of sacrifice expiates for nondefiant (including inadvertent) sins (Lv 4:1–5:13) and physical ritual impurities (Lv 12:6–8; 14:19, 22, 31; 15:15, 30). But in this case there is no mention of the Nazirite sinning or becoming impure.

The key to the function of this sin offering is found in the close parallel between the offerings of the Nazirite and those of the priests at the time of their consecration (Ex 29; Lv 8). Each set of sacrifices includes a sin offering, a burnt offering, a sacrifice partly eaten by the offerer(s) (i.e., ordination offering of the priests; fellowship offering of the Nazirite), and unleavened grain items in a basket. In the context of the priestly initiation, the sin offering apparently serves to raise Aaron and his sons to a higher level of ritual purity in preparation for completing their consecration. Similarly, the Nazirite is already basically pure, but the sin offering enhances purity to a high level before the climax of Naziriteship: shaving the dedicated hair and offering it to the Lord on the fire under the fellowship offering (6:18). Thus the hair, which is a token part of the Nazirite, is permanently sacrificed to God. The Israelite ritual system never comes closer to human sacrifice than this.

The priests are consecrated at the beginning of their ministry as lifelong servants of God. Nazirites, on the other hand, are brought to a kind of consecration at the end of temporary periods of dedication to special holiness. After a concluding dedication of priestly portions, Naziriteship is over (6:19–20). The high level of religious intensity is costly for a Nazirite (6:21; cf. Ac 21:23–24) and cannot be sustained. But for a brief, shining, and memorable moment, an ordinary Israelite can experience exceptional closeness to God.

The Bible also attests a lifelong Nazirite: Samson, whom the Lord dedicates before his miraculous birth to perform a special task of deliverance (Jdg 13). Samuel and John the Baptist are similar to Samson in some ways (1 Sm 1:11; Lk 1:15), although they are not called Nazirites. Jesus was not a Nazirite (Hb nazir; cf. Mt 11:19), although linguistic confusion with his identity as a Nazarene (someone from Nazareth, derived from the Semitic root nsr rather than nzr) has inspired centuries of artists to give him the long hair of a Nazirite. Nevertheless, his life of dedication to a special mission of deliverance ended, like Samson’s, with the sacrifice of his life (Jdg 16; Mt 27). But this end is also a new beginning because it serves as his sacrifice of consecration to eternal priesthood following his resurrection (Heb 7).

6:22–27. After the Aaronic priests are consecrated (Lv 8), they officiate inaugural sacrifices (Lv 9). Then Aaron raises his hands toward the people and blesses them (Lv 9:22; cf. v. 23). In Nm 6, after the concluding ceremony of elite Naziriteship, which somewhat parallels priestly consecration (see above), verses 22–27 instruct the priests how to orally bless all the people in order to place the Lord’s name on them so that he will bless them. Invoking him as the deity of all Israel affirms that the entire nation, not only priests or Nazirites, is to be God’s own possession, “my kingdom of priests and my holy nation” (Ex 19:5–6).

To give assurance that the blessing will be effective, the Lord himself gives the words to the priests (6:22–23). Because this is a request for divine blessing, it is a kind of prayer or benediction (paralleling the requests of the Lord’s Prayer, Mt 6:11–13). The blessing is formulated as poetry, with three pairs of expressions (6:24–26). The first member of each pair wishes for God to be favorably disposed toward his people (“bless,” “make his face shine,” “look with favor”). The second member wishes for his aid (“protect,” “be gracious,” “give you peace”). All benefits flow from a positive relationship with the Lord, which he freely offers.

D. Sanctuary supplies and service (7:1–8:26). 7:1–89. Following this reminder of Aaron’s blessing at the time when the ritual system was inaugurated (see Lv 9:22), Nm 7 fills in some details regarding establishment of the sanctuary: gifts for the sanctuary presented by chieftains on behalf of their twelve tribes (not including Levi). The gifts belong to two main categories. First is a practical offering of carts and oxen that the Levites will use to transport the sanctuary (7:1–9; cf. Nm 4). Second is a set of offerings for the dedication of the altar when it is consecrated (7:10–88; cf. Lv 8:11, 15).

Chronologically, the report of these gifts belongs with Lv 8–9. However, Leviticus focuses on ritual procedures. So the report is placed in Numbers because the presents are from the tribal chieftains (cf. Nm 1–2) for the sanctuary infrastructure, including the work of the Levites (cf. Nm 4).

This mosaic from a fifth-century-AD synagogue (Beth-shean, Israel) depicts the most holy place, lampstands, incense shovels, and ram’s horns.

© Baker Publishing Group and Dr. James C. Martin. Courtesy of the Israel Museum.

The offerings of the chieftains are practical gifts, honor the Lord’s altar, and acknowledge his sovereignty over their tribes. Numbers 7:89 emphasizes the dynamic nature of this sovereignty by reporting that when Moses enters the sanctuary (cf. Lv 9:23), the Lord speaks to him from between the cherubim over the ark of the covenant (cf. Ex 25:22).

8:1–4. Numbers 7 refers to establishment of the outer altar (7:10–88) and the most holy place (7:89). Numbers 8 then adds a reminder of the outer sanctum, or holy place, reiterating the instruction for the priest to mount the seven sanctuary lamps so that they will shed light in front of the golden lampstand to illuminate the area (8:1–4; cf. Ex 25:37).

8:5–26. Continuing the theme of founding the sanctuary system, 8:5–26 describes the ceremony of ritually purifying and setting apart the Levite workforce (cf. Nm 4). Some interpreters have mistakenly supposed that cleansing the Levites removed sin. It is true that the Hebrew word here is a form of the verb that often means “to sin” (e.g., Lv 4:2–3, 14, 22). However, the same verb can also refer to purification from physical ritual impurity alone (Lv 14:49, 52; Nm 19:12–13, 19–20; 31:19–20, 23). The cleansing procedures for the Levites in 8:7 only have to do with removing ritual impurity (especially corpse contamination; cf. Nm 19:9, 13, 20–21; 31:23), not sin in the sense of moral fault. They need this purification before they can safely come close to holy things in order to do their work at the sanctuary.

To complete their purification, the Levites offer a sin offering and a burnt offering (8:12). This pair of sacrifices functions as the equivalent of a larger sin offering (here for the entire Levite workforce), with the burnt offering supplementing the quantity of expiation provided by the sin offering (cf. Lv 5:6–9; Nm 15:22–29). The goal in this instance is for Aaron to make atonement for the Levites in order to purify them (8:21). This rules out the theory that the purpose of all sin offerings was to purify the sanctuary alone, never the offerer(s) (see further Lv 4; 16).

Numbers 4 stipulated that the Levite workforce must consist of men from thirty to fifty years of age (e.g., Nm 4:3, 23, 30). However, 8:23–26 puts the beginning age at twenty-five. The ages in chapter 4 may apply only to the period when it is necessary to perform the sensitive and potentially hazardous duty of moving the sanctuary from place to place (cf. 1 Ch 23:24–27; 2 Ch 31:17; Ezr 3:8).

E. Passover and final organization (9:1–10:10). 9:1–3. God reminds Moses in the first month of the second year after they have left Egypt to observe the Passover festival at its proper time on the night of the fourteenth day of the month. This reminder chronologically precedes the Lord’s command on the first day of the second month to carry out a military census (Nm. 1). But the book’s placement of the second Passover just before a second exodus, this time from the Wilderness of Sinai (Nm 10), gives the festival an impact of resumptive repetition: in the continuation of God’s deliverance from Egypt, his people are picking up where they left off and continuing to the promised land.

9:4–14. Some are not able to participate in Passover because they are ritually impure through corpse contamination (9:6–7; cf. Lv 7:20–21; Nm 5:1–4). So God graciously provides the solution of an alternate Passover date a month later for any Israelites or resident aliens unable to participate at the normal time due to their impurity or absence on a long journey (9:9–14).

9:15–23. Speaking of absence on a long journey, 9:15–23 recounts God’s guiding Israel to Canaan through the movements of his glory cloud (cf. Ex 13:21–22; 14:19–20, 24; 40:34–38). It is crucial for his people to stay with him and follow his leading.

The cloud has been guiding the Israelites since the beginning of their journey from Egypt (Ex 13:21–22). In Ex 40:34–38, after the tabernacle has been built, the cloud is associated with the glory of the Lord.

10:1–10. A system of signals, consisting of two trumpets blown by priests, is established for making announcements to the large community (10:2)—announcements such as precise times when tribal divisions are to set out after the cloud lifts from the tabernacle (10:5–6). Putting priests in charge of the signals (10:8) emphasizes that the Israelites are under divine control. Trumpet calls are to vary according to the number of trumpets, kinds of blasts, and the number of blasts. These variables will communicate different messages. For instance, one kind of blast indicates assembly and celebration at the camp (10:3–4, 7, 10), and another signals moving out to travel or to make war (10:5–6, 9).

The Israelites travel from the Wilderness of Sinai into the Wilderness of Paran.

2. WILDERNESS JOURNEY WITH GOD (10:11–25:18)

A. Departure from the Wilderness of Sinai (10:11–36). 10:11. At last, on the twentieth day of the second month of the second year after the Israelites left Egypt, the divine cloud lifts from “the tabernacle of the testimony.” This is only twenty days after the Lord has commanded Moses to carry out the military census (1:1) and a week after the alternative Passover, on the fourteenth day of the second month (9:11). References to the Lord’s testimony (10:11) and covenant (10:33) in Nm 10 remind the audience that the Israelites’ bond to the Lord requires them to serve him with respect, trust, loyalty, and obedience, all of which will be in short supply on various occasions recounted in the following chapters. [Paran]

10:12–28. When the Israelites set out from the Wilderness of Sinai in accordance with the procedures that the Lord has specified (cf. 2:1–34; 4:1–49), the Levites move the sanctuary and its sacred objects (10:17, 21), and the ark of the Lord’s covenant leads the way (10:33).

According to 2:17, the sanctuary and Levites are to travel in the middle of the four major tribal divisions. In chapter 10 the Kohathite Levites, carrying the sacred objects, do set out between the second and third divisions (10:21). However, the Gershonite and Merarite Levites with the tabernacle have departed earlier (10:17). This makes it possible for the Gershonites and Merarites to reach their destination and set up the tabernacle before the Kohathites arrive (10:21). Then the sacred objects can go directly into their places rather than remaining on the shoulders of the Kohathites while the tabernacle is reassembled.

10:29–36. Moses seeks the assistance of Hobab, his Midianite brother-in-law, to locate good camping places and be the “eyes” of Israel (10:29–32; cf. Ex 2:18, 21). This would at first glance seem to be in tension with the notice that the ark of the covenant goes before the Israelites to seek a resting place for them (10:33). But the Lord’s role in guiding Israel does not rule out human participation and cooperation in working out details that are within the framework of his plan.

B. Escalating rebellion (11:1–14:45). 11:1–3. Journeying through wilderness is a lot more strenuous than camping at Mount Sinai. The Israelites have not gone far when they start to complain, and God is incensed. His fire blazes among them, causing damage in the outer part of their camp (11:1). It is not clear whether anybody is hurt, but the people are traumatized. They cry out to Moses, who intercedes with the Lord through prayer, and the fire dies down. Moses dubs the location Taberah, “Place of Burning,” as a reminder that divine fire has blazed there (11:2–3).

This brief episode contains the DNA of much of the Israelites’ wilderness experience. Elements that recur and develop with variations include rebellious complaining, divine wrath in response, intercession by Moses, subsiding of divine wrath after infliction of some damage, and remembrance of the experience as a lesson for the future.

Order of the Tribes When Traveling (Nm 10)

Another element is implicit in the notice that the Lord targets the outskirts of the camp, where the “mixed crowd” would have had their tents. Because they did not belong to the Israelite tribes, they would have camped outside the four main tribal divisions that surrounded the sanctuary (cf. Lv 24:10). These non-Israelites or partial Israelites cast in their lot with the Israelites when they departed from Egypt (Ex 12:38). The fact that the Lord strikes the area of the mixed crowd at Taberah suggests that they instigated or led the chorus of complaining.

11:4–15. The next episode explicitly begins with the mixed crowd, described as inferior “riffraff,” or a bunch of vagabonds. Their intense craving for meat infects the Israelites and incites them to weep again (11:4). The people prefer Egyptian food to manna, and life under Pharaoh to their present situation under the leadership of God and his servant Moses (11:5–9; cf. 11:20). Still slaves at heart (cf. Ac 7:39), they rebel against the cost of freedom.

God is angry again, but this time Moses is upset too. Rather than interceding, he bitterly objects that God has laid the burden of all the people and their unreasonable request on him (11:10–15). The Lord treats Moses with patience and understanding (cf. 1 Kg 19:4–8), providing two solutions for his dilemma.

11:16–30. First, God has him appoint seventy elders, who are already recognized as leaders, to help him govern the Israelites (11:16). Then if the people become unhappy, these tribal representatives will absorb the impact and have a vested interest in calming them down. Notice how God works with existing social structures that are already familiar and credible to the Israelites.

The Lord legitimates the participation of the seventy elders with Moses as mediators between himself and the people by taking some of the divine Spirit that is on Moses and putting it on them (11:17). They demonstrate their gift of the Spirit by prophesying just once (11:24–25). The text does not record their words; the point is the fact of their prophesying rather than the content.

Most of the elders prophesy while they are assembled around the sanctuary. However, two have not answered the call to go from their place of encampment to the sanctuary. Nevertheless, the Spirit finds them and they prophesy too (11:26–27). Their breach of protocol alarms Joshua, Moses’s assistant. Rather than seeking to quench the Spirit (cf. 1 Th 5:19–20), as Joshua suggests, Moses only wishes that all of the people would similarly receive the Spirit (11:28–29). He understands that the Spirit has confirmed the call of the two men, in spite of their apparent reticence, and it is not his place to get in God’s way (cf. Ac 10:44–48; 11:15–18).

11:31–35. The Lord’s second solution for Moses is to miraculously provide all the Israelites with an abundance of meat, without depleting their livestock. He does this by sending a wind to divert millions of quail from the sea to the area of the Israelite camp (11:31; cf. Ex 16:13). Quail have relatively heavy bodies, so they tire easily on long flights, especially if winds are not in their favor. Therefore, it is not surprising that quail flying a few feet above the ground would be easy prey for the Israelites to knock out of the air.

The ravenous Israelites work around the clock to gather a huge number of the hapless birds, at least sixty bushels (or ten homers; a homer was originally a donkey load) of quail each (11:32). Flocks consisting of millions of migrating quail have been recorded as recently as the 1900s. But the remarkable number in Nm 11, combined with the timing in response to the Israelites’ cry for meat, would be due to divine intervention (cf. 11:23).

Abundantly giving the people what they want is not weakness on God’s part but a way to discipline them. He provides enough meat for them to eat it every day for a whole month, but this is to make them come to loathe it, in order to teach them a lesson for rejecting him and questioning why they ever left Egypt (11:18–20).

The Lord has told Moses to command the Israelites to consecrate themselves in preparation for eating the meat that he will provide (11:18). This implies that receiving God’s miraculous gift will be a sacred event, like a sacrifice from which the offerer could eat (cf. 1 Sm 16:5). But the people turn it into an orgy of greed and a feeding frenzy. Disgusted by their lack of restraint or respect for him, he does not waste time by giving them a month to experience their punishment but immediately strikes many dead with a plague. The place is named after the new cemetery there: Kibroth-hattaavah, “The Graves of Craving” (11:33–34). The name provides the Israelites (and us) with a potent reminder of the Lord’s attitude toward greed and gluttony.

12:1–3. At Hazeroth (11:35), Moses has to endure a more personal kind of attack on his leadership from Miriam and Aaron, his own sister and brother (12:1–2). Miriam is named before Aaron, suggesting that she is the instigator. Criticism of Moses’s marriage is a way to lower him closer to the level of his sister and brother, who have also received the prophetic gift and therefore believe that they should have a greater role in leading Israel than Moses is giving them. This sibling rivalry is about power.

It is surprising that Moses’s wife is described here as “Cushite” (see the article “Who Are the Cushites?”). This raises the question of whether Moses took a black African wife, either in place of or in addition to Zipporah. Aside from this verse, there is no clear record of Moses marrying anyone but Zipporah, a Midianite (Ex 2:16, 21). Nor is there any indication that Zipporah has died. The Midianite relatives of Moses were mentioned recently in Nm 10, when the Israelites departed from Mount Sinai (Nm 10:29). It is possible that Miriam and Aaron are making a racial slur against Zipporah, belittling her for the darker color of her Midianite skin by likening her to a Cushite. Whether the reference is to Zipporah or another wife, Miriam and Aaron are choosing to regard Moses’s marriage to a non-Israelite, whom they view as inferior, as diminishing his leadership. [Who Are the Cushites?]

Moses does not attempt to defend himself against Miriam and Aaron, due to his extreme humility (12:3—not likely written by Moses to honor himself). He is not confident in himself but is completely confident in and zealous for the Lord, under whom his ego is subsumed. Undoubtedly this was a key to his unique access to God and his unparalleled career as a leader whom the Lord was able to use in order to accomplish his purposes.

12:4–10. God does not deny the prophetic gifts or leadership roles of Aaron and Miriam (cf. Mc 6:4). Rather, he rebukes them for speaking against Moses, who is more than a prophet, communicating with him face to face (12:4–8). Then Miriam is struck with a disease that gives her skin an appearance like snow, whether flaky or white or both (12:10; cf. Lv 13–14). Apparently Miriam receives the blow because she is the prime culprit in diminishing Moses’s sacred role, a sin of sacrilege (cf. the same divine punishment for sacrilege in 2 Kg 5:27; 2 Ch 26:19–21). The punishment of skin disease, especially if it makes Miriam an ugly white color, also exquisitely fits the crime of casting contempt on Moses’s wife for the dark pigment of her skin.

12:11–16. If a skin disease were inflicted on Aaron, its impurity would disqualify him from priestly service and profane his high-priestly garments (Lv 13:1–59; cf. 22:1–9). Nevertheless, he is punished by anguish at seeing the repulsive living death of his sister. He is the appointed ritual mediator for all Israel, but he confesses their sin to Moses and begs for Moses’s intercession (12:11–13; cf. Jb 42:7–9).

The Lord implicitly agrees to heal Miriam but requires that she remain outside the camp for seven days to bear her shame (12:14–15) and presumably because she is ritually impure (cf. Lv 13:46; Nm 5:1–4). A person healed of skin disease is permitted to enter the camp (but not his or her tent) after the purification ritual of the first day (Lv 14:8). So it appears that God delays healing Miriam for a week. In this episode is a major warning for all Israel: if not even Miriam and Aaron can get away with undermining divinely appointed leadership, do not imagine that anyone else can!

13:1–16. The next crisis is much more serious and negatively affects the Israelites for decades to come. It comes at a major moment of decision as the national war camp approaches the southern border of Canaan and camps at Kadesh (13:26; Kadesh-barnea in Nm 32:8 and Dt 1:19). Will the Israelites go ahead and take the land that the Lord has promised to them?

According to Numbers, Moses follows the Lord’s command to send a group of scouts or spies, consisting of a leader from each tribe (except Levi), to explore Canaan (13:1–16). Deuteronomy presents the idea of sending scouts to obtain military intelligence as coming from the people and accepted by Moses (Dt 1:22–23). The two books do not contradict each other but emphasize different aspects of the same account: the people propose sending scouts and Moses agrees (Deuteronomy); he of course takes the matter to God, who approves and commands Moses to go ahead with the plan (Numbers).

Moses undoubtedly assumes that the report of the scouts, who are credible representatives from the various tribes, will be glowing and will motivate the people to leave the wilderness and enter the promised land. Archaeologists have discovered that during this period (Late Bronze Age), much of the hill country was sparsely settled and lacked extensive fortifications. So the scouts should have found this area vulnerable to conquest.

13:17–29. After a major expedition, the scouts return to the Israelite encampment with impressive samples of fruit and affirm that the land is indeed “flowing with milk and honey” (13:26–27; cf. Ex 3:8, 17; 13:5). But they quickly move on to describe military obstacles. Rather than pointing out a route of least resistance to gain an initial foothold in the hill country, they summarize the nations living throughout Canaan, including on the Mediterranean coast and along the Jordan Valley (13:28–29). This gives the Israelites the impression that the promised land is impenetrable.

13:30–33. The fact that it is necessary for Caleb, the scout from Judah (cf. 13:6), to quiet the people before offering his minority report shows that their dismayed reaction is already causing an uproar (13:30). He emphatically makes the motion that Israel should and can take the land. He has seen the same obstacles as the other scouts but includes God in “we,” believing that the Lord can overcome Israel’s enemies and fulfill his promise.

The other scouts jump in to counter Caleb (13:31). Determined to discourage their people, the negative scouts stoop to contradicting themselves and distorting the truth. They now give a bad report of the land they have earlier praised, claiming that it is deadly (13:32). Whatever they mean by this, it does not make sense that nations living in such a land would flourish (including growing to great stature) and therefore pose a major threat to invaders from outside (13:33).

Numbers 14:2 is not the first time that the Israelites have complained that it would have been better had they died in Egypt. They leveled the same complaint shortly after they started on their journey (Ex 16:3). In fact, they were already complaining before they crossed the Red Sea (Ex 14:11–12).

14:1–10. Faithless as they are, the Israelites do not see through the contradictions but accept the faithless majority report. The next day, they are considering replacing Moses and Aaron with a leader who will take them back to Egypt (14:1–4). Joshua and Caleb make a final, passionate appeal, but the people respond by saying they should be stoned (14:6–10). Thus the people condemn themselves and seal their fate.

14:11–19. The Lord wants to exterminate the Israelites and make Moses a great nation instead (14:11–12). Moses intercedes, as he has earlier, after the golden calf episode (cf. Ex 32:9–13). He appeals to God’s need to maintain his reputation in the world by fulfilling his promise to bring his people into their land (14:13–16). Moses also appeals to the Lord’s gracious character by citing his self-proclaimed slowness to anger, loving-kindness, and forgiveness (14:17–19; cf. Ex 34:6–7).

14:20–38. God agrees to forgive the Israelites as Moses has requested, which means that he withdraws his threat to destroy the entire nation (14:20). But it does not mean that rebellious individuals within the nation will go unpunished, in this case adding up to the entire generation of adults that he has brought out of Egypt, except for faithful Caleb and Joshua (14:22–24, 29–30). He will not kill the people outright and thereby harm his international reputation but will keep them in the wilderness, the home that they have chosen, until they all die natural deaths and their children grow up to replace them (14:31). He refuses to reward rebellion by giving a home in the promised land to disloyal people connected with him. To do that would be to send the world a wrong message about his glorious and holy character (see 14:21) and damage his purpose of blessing all nations through the descendants of Abraham (Gn 12:3; 22:18).

To make sure the connection between the Israelites’ punishment and the scout fiasco will be remembered, the extra time in the wilderness will be forty years, a year for each day that the scouts explored Canaan (14:32–35). The ten faithless scouts, who are especially culpable, immediately die from a plague as firstfruits of death in the wilderness (14:36–38).

14:39–45. In response to the divine sentence, the Israelites admit their sin and claim readiness to obey God by entering Canaan, which now seems like a better option (14:39–40). But they have already definitively proven their pathological lack of faith, without which God cannot give them the land. Their opportunity has passed. Nevertheless, they presumptuously disregard Moses’s warning and vainly attempt to storm Canaan by themselves, without the Lord (14:41–44).

If the Israelites had entered Canaan when it was time to go, they would have enjoyed the advantage that their enemies were terrified because of what the Lord had recently done to the Egyptians (Ex 7–14), not to mention the Amalekites who attacked them on the way to Mount Sinai (Ex 17:8–13). Now the Israelites’ defeat by other Amalekites, along with Canaanites (14:45), removes the fear that these and other nations had of them. By snatching defeat out of the jaws of victory, the adult Israelites make it harder for their children to take Canaan later on.

C. Laws concerning loyalty versus disloyalty (15:1–41). After the tumultuous narrative events of the previous chapter, the collection of laws in Nm 15 seems like an anticlimax. The first part of the chapter concerns offerings to the Lord, including expiatory sacrifices (15:1–29). Then the topic shifts to inexpiable sin (15:30–36), and finally a visible reminder of loyalty to God attached to Israelite garments (15:37–41). Looking at the chapter as a whole reveals its relevance between the reports of major rebellions in chapters 14 and 16. The theme is encouragement to loyalty and warning against disloyalty.

15:1–21. The first law specifies accompanying grain and wine offerings for all burnt offerings and sacrifices of herd or flock animals (15:1–16). The Hebrew term rendered “sacrifice” (15:3, 5, 8) refers to a kind of sacrifice from which an offerer is permitted to eat (especially a fellowship offering; Lv 3:1–17; 7:11–36). The fact that some kinds of animal sacrifices require accompaniments to make them complete meals for the deity (cf. Gn 18:6–8) is already known to the Israelites (e.g., Ex 29:40–41; Lv 23:13, 18; Nm 6:17). However, Nm 15 systematically specifies amounts of grain and drink offerings corresponding to sacrificial victims of different sizes.

This law regarding sacrifices reminds the Israelites of their basic obligation to serve the Lord. But the fact that Israel continues to enjoy the privilege of worshiping him is due to divine grace. The introduction to the law—“When you enter the land . . .” (15:2)—is striking in light of the previous chapter. Whether the legislation was actually given just after the events of chapter 14 or placed here for thematic reasons, it reinforces the promise that the (next generation of) Israelites will indeed live in Canaan. The next law regarding the obligation to offer a loaf of the first batch of dough from the grain harvest (15:17–21) is introduced with the same message (15:18).

15:22–29. The following legislation concerns sin offerings as remedies for inadvertent sins of the entire community (15:22–26) or of an individual (15:27–29). Notice how Nm 15 roughly follows the order in Leviticus, which prescribes burnt, grain, and fellowship offerings in chapters 1–3 and sin offerings in chapter 4.

Numbers 15:27–29 simply reiterates the requirement of a female goat as the sin offering of an individual, adding only the stipulation that the animal be a year old (cf. Lv 4:27–35). However, 15:22–26 significantly modifies the sacrifice for the community. In Lv 4:13–21, the sin of the community requires only the sin offering of a bull, the same as for the sin of the high priest (Lv 4:3–12). But in Nm 15, the community’s sin calls for a pair of sacrifices: a burnt-offering bull, with its grain and drink accompaniments, in addition to a male goat as a sin offering (15:24). The sin offering would actually be performed first (cf. Lv 5:7–10; Nm 8:8, 12). This pair serves the function of a sin offering, but the burnt offering greatly augments the quantity of the sacrifice and its expiation in order to benefit the whole community (cf. Nm 8:12, 21—for all Levites).

15:30–31. There are sacrificial remedies for inadvertent sins (15:22–29) but not for a sin committed “defiantly” (15:30; cf. Ex 14:8; Nm 33:3). In such a case, the perpetrator is condemned to the terminal divine punishment of being “cut off”—that is, denial of an afterlife (15:31). Numbers 15 does not deny that nondefiant deliberate sins can be expiated (Lv 5:1; 6:1–7; cf. Nm 5:5–10). But it contrasts inadvertent sins, which are always nondefiant and therefore expiable, with defiant sins in order to implicitly warn against the latter, for which there is no remedy. This warning is highly relevant to the surrounding narrative context of the book of Numbers, which features rebellious, defiant sins, both of individuals and of the entire community (chaps. 14; 16).

15:32–36. A brief story of a man caught gathering wood on the Sabbath, which occurs sometime during the Israelite wilderness experience, is placed here for a thematic reason. The story provides an implicit example of defiant sin, even though his action is not labeled “defiant.” The Israelites have been repeatedly prohibited from work on the seventh-day Sabbath (e.g., Ex 16:29–30; 20:8–11), and the penalty for violation is death and “cutting off” (Ex 31:12–17; 35:2–3—prohibition against kindling a fire). So the man has no excuse and is clearly rebelling against the Lord’s authority. By insisting on working when God has provided rest, he is a microcosm of his faithless generation, which prefers slavery to the Lord’s deliverance. There is no doubt that he will die; the only question is the manner of his execution. The Lord provides the answer: stoning by the community outside the camp (in order not to defile it; 15:35–36).

15:37–41. The last section in Nm 15 instructs each of the Israelites to make tassels or fringes, with bluish (or violet) cords attached to them, on the corners of their garments (15:38; cf. Lk 8:44—fringe of Jesus’s garment). The purpose is to provide them with a tangible reminder to obey the Lord’s commandments and be holy rather than following their own hearts and eyes, which are causing the people to “prostitute” themselves in the figurative sense by disloyalty to God (15:39; cf. 14:33). In other words, they should make their decisions according to the word of the Lord, rather than on the basis of their feelings and senses.

Bluish color was associated with royalty because this kind of dye (extracted from certain snails found at the Mediterranean coast) was expensive. It was also used for priestly garments (Ex 28). So the cords will remind the Israelites that all of them constitute a “kingdom of priests” and a “holy nation” (Ex 19:6; cf. 1 Pt 2:9—priesthood of all Christian believers).

D. Rebellion of Korah and aftermath (16:1–18:32). Numbers 16 is one of the most harrowing and dramatic chapters in the entire Bible. It reports the ill-fated rebellion of Korah and company (16:1–40) and the subsequent uprising of the Israelite community to protest their “martyrdom” (16:41–50).

16:1–2. In the wake of the scouting episode (chaps. 13–14), a large and powerful contingent of leading Israelites blames Moses and Aaron for keeping the Israelites in the wilderness until the adult generation will die. The attack against the Lord’s appointed leaders is two-pronged. Korah, a Kohathite Levite closely related to Moses and Aaron (cf. Ex 6:18; Nm 3:19, 27), leads a group of Levites in challenging the exclusive right of Aaron and sons to the exercise of religious leadership through the priesthood. Dathan, Abiram, and On, from the tribe of Reuben, more specifically target the role of Moses.

16:3. The basic argument of the rebels is that Moses and Aaron have wrongly appropriated excessive power over the Israelites, who are all holy. Indeed, the law regarding tassels at the end of the previous chapter affirms the holiness of each member of God’s chosen community. But there, holiness is tied to obedience to God’s commands (15:40); it is not unconditional. Moses and Aaron have not seized power; the Lord has appointed them as his servants. So Korah and company are challenging God’s leadership.

16:4–17. Moses offers a counterchallenge: if Korah and company want to go ahead and try to be priests, they can show up at the sanctuary the next morning and burn incense along with Aaron. They will find out whether God accepts them or Aaron as holy priests (16:5–11, 16–17). This challenge of a duel with firepans is deadly serious. Did the Levites not believe God when he had warned that any nonpriest who usurped priestly prerogatives would be put to death (Nm 3:10, 38)?

16:18–24. The next day, Korah and his colleagues presume to show up at the sanctuary and burn incense (16:18). With them comes the whole community, which Korah has persuaded to turn against Moses and Aaron (16:19). God is about to instantly destroy the community, but due to the intercession of Moses and Aaron, he only warns that everyone must get away from the dwellings of the chief rebels (16:20–24).

16:25–34. Moses goes to the Reubenite encampment of Dathan and Abiram to pass on the warning to the people there (16:25–27). In response to their sizzling challenge (16:12–14), he proposes another deadly counterchallenge: if God makes the ground swallow them and all that belongs to them, the Israelites will know that they have despised the Lord when they claimed that he had not sent Moses (16:28–30). This immediately happens (16:31–32). Having reached for higher status, they are lowered into the nether region (16:33).

16:35–40. Then divine fire consumes the two hundred and fifty unauthorized men who are offering incense (16:35; perhaps including Korah—cf. 16:40), just as it slew two sons of Aaron when they burned incense with unauthorized fire (Lv 10:1–2). The divine fire has sanctified the firepans of the rebels, so they now belong to the sanctuary (16:37–38). The high priest’s son puts them to good use by having them hammered out as a plating on the outer altar in order to warn nonpriests not to follow the example of the rebels and share their fate (16:39–40).

16:41–50. The people were already sympathetic to the complaints of Korah and company. So the next day, they accuse Moses and Aaron of killing the Lord’s people (16:41). Remarkably, they refuse to accept miraculous retribution on Korah and company as coming from God himself. The implication is that Moses and Aaron are employing some kind of black magic. Thus the people attribute the work of God to an evil force (cf. the unpardonable sin in Mt 12:24–32).

Again the Lord warns Moses and Aaron to get away so that he can instantly consume the Israelites (16:45; cf. 16:21). But this time he has no fuse left and does not wait for their intercession. Aaron’s rapid mediation with incense to make atonement (meaning “propitiation” here) saves most of them (16:46–47), but 14,700 die of a quickly spreading plague before his incense can reach them (16:49). The action of Aaron, who literally stands “between the dead and the living” (16:48), demonstrates the value and urgency of intercession, which Christians can do through prayers (e.g., Mt 5:44; Jms 5:14–18), which ascend to God like incense (Rv 5:8; cf. 8:3–4).

17:1–9. To put a final end to challenges against the priesthood of Aaron and his descendants, God tells Moses to set up a positive test with staffs from the tribal leaders and Aaron, which cannot be viewed as black magic (17:1–7). By the next day, Aaron’s staff (cf. Ex 7:9–10, 12, 19; 8:5, 16–17) has miraculously blossomed and already produced ripe almonds (Ex 25:33–34; 37:19–20), proving that the holy God, the Creator of life, has chosen him to be priest (17:8).

17:10–13. Moses deposits Aaron’s staff back in the sanctuary as a perpetual sign of the Lord’s choice (17:10–11). According to Heb 9:4, Aaron’s staff was kept inside the ark of the covenant, along with the tablets and a jar containing a sample of manna (cf. Ex 16:33–34).

The Lord has convinced the Israelites that it is better to die a natural death in the wilderness than to further incur his retributive justice. But now they are terrified that they might all perish like the rebels (cf. 16:34) if any of them approaches the sanctuary (17:12–13).

18:1–7. God’s answer is to make the priests and other Levites subject to divine wrath if somebody should violate the boundaries and rules protecting the sanctuary’s holiness. If a nonpriest, including a Levite, attempts to usurp any priestly function, only that person will be put to death (18:6–7). If the unauthorized individual succeeds in transgressing a priestly prerogative, the priests will also die (18:2–3; cf. 18:22–23; 1:51; 3:10, 38). This is serious incentive to guard the sanctuary and its priestly service!

18:8–32. God compensates the priests and Levites for their important, hazardous responsibilities and continual vigilance, which would make it hard for those on duty to make a living any other way. Unlike the other tribes, Levi will not inherit a territory in Canaan in order to pursue an agricultural livelihood (18:20). Rather, God allots all the tithes (tenth portions; cf. Gn 14:20; 28:22; Lv 27:30–32; Neh 10:38; Mal 3:8–10) of the Israelites’ agricultural produce to the Levites (18:21–24). To the priests he assigns a permanent (“covenant of salt”; 18:19) entitlement from sacred gifts, including portions of sacrifices, plus a tithe of the tithes received by the Levites (18:25–28). Similarly, Christian ministers have the right to material support for spiritual service (Lk 10:7; 1 Co 9:13–14). [Firstfruits]

E. Law of purification from corpse impurity (19:1–22). Leviticus and Numbers have repeatedly mentioned the severe physical ritual impurity of corpse contamination (Lv 21:1–4, 11; Nm 5:2; 6:6–12; 9:6–12), the possibility of purification from it on the seventh day after defilement (Nm 6:9), and the means of cleansing through sprinkling water of purification (Nm 8:7; cf. 8:21). Numbers 19 explains the nature of the water and specifics of the sprinkling. A comprehensive remedy for corpse contamination comes as a relief after all the deaths that have occurred from chapter 11 onward.

19:1–10. Numbers 19:1–10 outlines the procedure for producing the most powerful active ingredient in the “water to remove impurity,” which is the cleansing agent. This ingredient consists of ashes of a reddish cow that is sacrificed as “a sin offering” (19:9). Rather than applying the blood to an altar, the officiating priest sprinkles some of it seven times in the direction of the sanctuary, thereby linking the ritual to God (19:4).

This sacrifice for a physical ritual impurity (not a “sin” in the sense of moral fault) is unusual in several respects: (1) it is performed outside the Israelite camp to avoid polluting the sanctuary (19:3), (2) it is completely burned up to produce a long-lasting supply of ashes for the entire nation (19:5), and (3) the officiating priest adds several elements to the burning in order to enhance the cleansing properties and volume of the ashes. These elements are cedar wood, hyssop, and crimson yarn (19:6; cf. Lv 14:4, 6, 49, 51–52; Ps 51:7). The reddish color of the cow, along with the (at least partly) reddish cedar wood and red yarn, suggests that the ashes are the functional equivalent of dehydrated blood, which is red.

The most unusual feature of the reddish-cow ritual is its effect on those who participate in burning the cow and storing its ashes: they incur minor ritual impurity that requires laundering clothes, bathing in water, and waiting until evening (19:7–10). Similarly, a pure person who later contacts water of purification containing some of the ashes in order to sprinkle them on a corpse-contaminated person or thing also becomes impure (19:21). Paradoxically, the ashes make pure persons impure but cleanse contaminated persons. This has puzzled scholars for many centuries.

Two concepts unlock the mystery. First, water containing the cow’s ashes removes corpse contamination by absorbing impurity from the person or thing on which it is sprinkled. This explains why a pure person who touches the water receives impurity from it. Second, the burning cow is viewed as a unit both in time and space. So when tiny parts of it in the form of ashes later absorb impurity, the whole cow becomes impure at the time of its burning. Therefore, those who participate in the burning become secondarily contaminated.

The reddish-cow sin offering uniquely shows how a sacrifice can expiate future evils. The offering of the cow yields a store of ashes that will serve the community for an extended period of time, therefore covering ritual impurity that has not yet occurred at the time the cow is burned. Sprinkling water that contains these ashes then conveys on the unclean person the purification brought about by the previous offering. By a similar dynamic, Christians today can benefit from Christ’s sacrifice, which bore their mortality and sins many centuries before they were even born.

19:11–22. Numbers 19:11–22 explains (1) how one can know what a corpse has contaminated (including everything and everyone in the same enclosed space; 19:14–16), (2) how to formulate the “water to remove impurity” (some reddish-cow ashes plus fresh water; 19:17), (3) when it must be sprinkled (third and seventh days; 19:12, 19), and (4) the penalty for automatically defiling the sanctuary by deliberately neglecting to be purified (divine penalty of “cutting off,” with no opportunity for forgiveness through expiatory sacrifice; 19:13, 20). Notice that the fresh (from a flowing source) water mixed with the ashes is literally “fresh” water (19:17; cf. Gn 26:19; Lv 14:5–6; Jn 4:10–11; 7:38), an appropriate remedy for impurity resulting from death.

F. From failure to victory (20:1–21:35). 20:1. Following the remedy for corpse impurity (chap. 19), we learn in chapter 20 that Miriam, Aaron, and Moses will share the fate of the adult generation by dying without entering Canaan. Miriam dies when the Israelites arrive (again?) at (the same or another) Kadesh (20:1). The text does not say why she is denied entrance to Canaan, but the last time we have heard from her is in Nm 12, where she is punished with skin disease for undermining Moses.

20:2–13. Also at Kadesh, the reaction of Moses and Aaron to an uprising of the older generation (“brothers” of Korah and company who left Egypt; 20:3) against them due to lack of water results in their exclusion from Canaan. God tells Moses to take his staff, but he and Aaron are to call water from a rock by speaking to it (20:8), rather than striking it, as Moses has done at Rephidim (cf. Ex 17:1–7). This would have been a greater miracle because speaking could not physically dislodge a plug to an aquifer.

Moses loses patience with the people, calling them “rebels.” He fails to glorify God by rhetorically asking, “Must we [Moses and Aaron] bring water out of this rock for you?” (20:10). He fails to follow the divine instruction, instead raising his hand and striking the rock twice (20:11a). Aaron’s role is passive: he fails to speak to the rock with Moses.

Water flows from the rock anyway (20:11b), but because the brothers have not treated God as holy (at Kadesh, which means “Holy”) by showing trust in him before the community, they cannot lead the Israelites into the promised land (20:12; cf. Nm 27:14). As leaders, they have a high level of accountability to properly represent God to their people (cf. Lv 10:3).

20:14–21. Numbers 20:14–21 records diplomatic correspondence from (the same or another) Kadesh, near the end of the wilderness period, between Moses and the king of the Edomites. These people are descended from Esau and therefore related to the Israelites (20:14; cf. Gn 36). For some reason, the Israelites want to enter Canaan from the east, rather than from the south, as they expected to do decades earlier (Nm 13–14). To enter from the east, they need to pass through Edom, on the King’s Highway (20:17). But Moses’s appeal to kinship ties between the two nations is to no avail (20:18–20). Consequently, the Israelites are forced to make a long detour around Edom (20:21).

As God says to Moses and Aaron, they will not live to lead the people into the promised land (Nm 20:12; cf. 27:12–14). Deuteronomy closes with Moses looking out over the promised land before he dies, within sight of the land but unable to enter it (Dt 34:31–34).

20:22–29. During this journey, Aaron dies on Mount Hor. Before Aaron dies, Moses transfers his holy high-priestly garments to Eleazar, Aaron’s son (20:28), presumably to keep them from becoming impure.

21:1–3. While the Israelites are traveling eastward under the southern part of Canaan, the Canaanite king of Arad attacks them (21:1), just as the Amalekites assaulted them at Rephidim soon after Moses brought water from a rock there (Ex 17). The Israelites have withdrawn from the Edomites’ show of force (20:20) because they are relatives (cf. Dt 2:4–5). But there is no reason to refrain from retaliating against unprovoked Canaanite aggression. So the Israelites vow to devote (Hb root hrm, of irrevocable dedication to God; cf. Lv 27:28–29) the towns of this king to the Lord for total destruction, and their holy war is successful with God’s help (21:2). God does not allow other nations to pick on his chosen people with impunity (cf. the fate of Amalek in Ex 17:13–16; 1 Sm 15:1–35).

The Israelites dub the location “Hormah” (from the root hrm), referring to sacral destruction (21:3). Ironically, it was Hormah to which the Amalekites and Canaanites beat back the presumptuous Israelites when they attempted to storm Canaan without God (Nm 14:45). Thus the Israelites gain victory at a place of former defeat.

21:4–9. Victory is soon followed by another failure. The people become impatient during the tedious and taxing extra trip around Edom, complain of lack of food and water, and ungratefully express loathing for the manna (21:4–5). Divine punishment comes in the form of deadly poisonous snakes (21:6).

Moses intercedes, but rather than simply removing the threat as he has at Taberah (11:2), the Lord makes healing from snakebite conditional on trust in him as expressed by looking at a bronze snake mounted on a pole (21:7–9). This is not magic, as many have supposed (including later Israelites who worshiped the object; 2 Kg 18:4), but a test of faith. All are free to accept or reject the means God has provided and will live or die with the consequences. Why a statue of a snake? In this way the people confront the source of their trouble, which they have brought upon themselves.

Jesus likens himself on the cross to the bronze snake that Moses raised up (Jn 3:14–18; cf. 12:32). By becoming sin for us, Jesus enables us to become righteous (2 Co 5:21; cf. Gn 3:1–24).

21:10–15. Moving northward, the Israelites cross the Zered Valley (21:12). Deuteronomy 2:14 notes that by this point the last Israelites belonging to the generation of fighting-age men who rebelled thirty-eight years before at Kadesh (Nm 14) have died. Now the nation can go ahead and enter Canaan.

21:16–20. At Beer (pronounced Be-er), which means “Well,” the Israelites celebrate the divine gift of water that they have received by cooperating with God through digging a well (21:16–18—this is a refreshing change from their complaining about lack of water). Again the Israelites gain victory in an area of past failure (cf. 21:3).

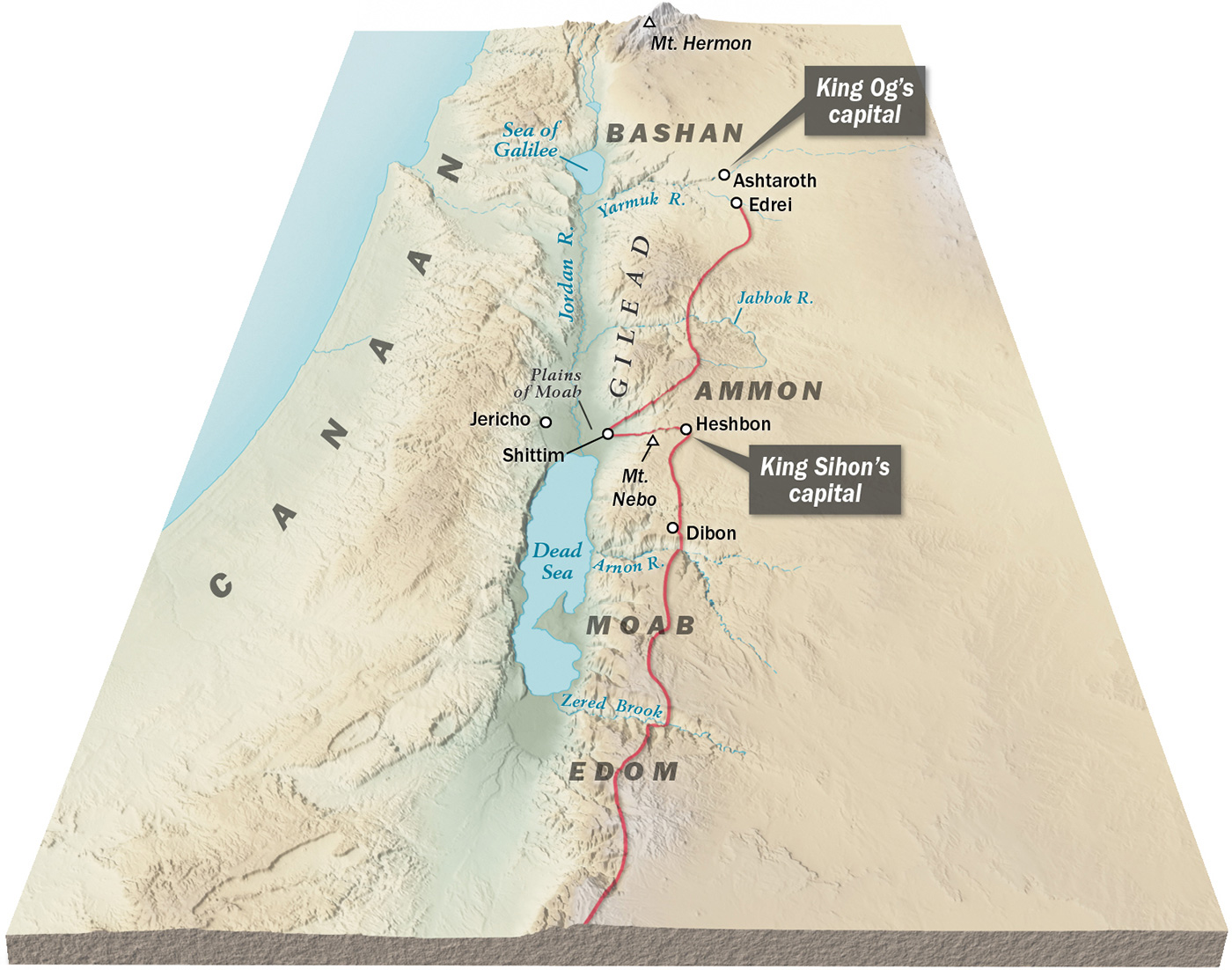

21:21–35. Numbers 21:21–35 recounts Israelite conquests of the Transjordanian territories of Sihon, king of the Amorites (21:21–32), and Og, king of Bashan (21:33–35). The Israelites only want to pass through to a point east of Jericho in order to penetrate Canaan from there, but these kings will not let them do so in peace. These military engagements provide the Israelites with valuable experience, plus encouragement that they can take the promised land by cooperating with God.

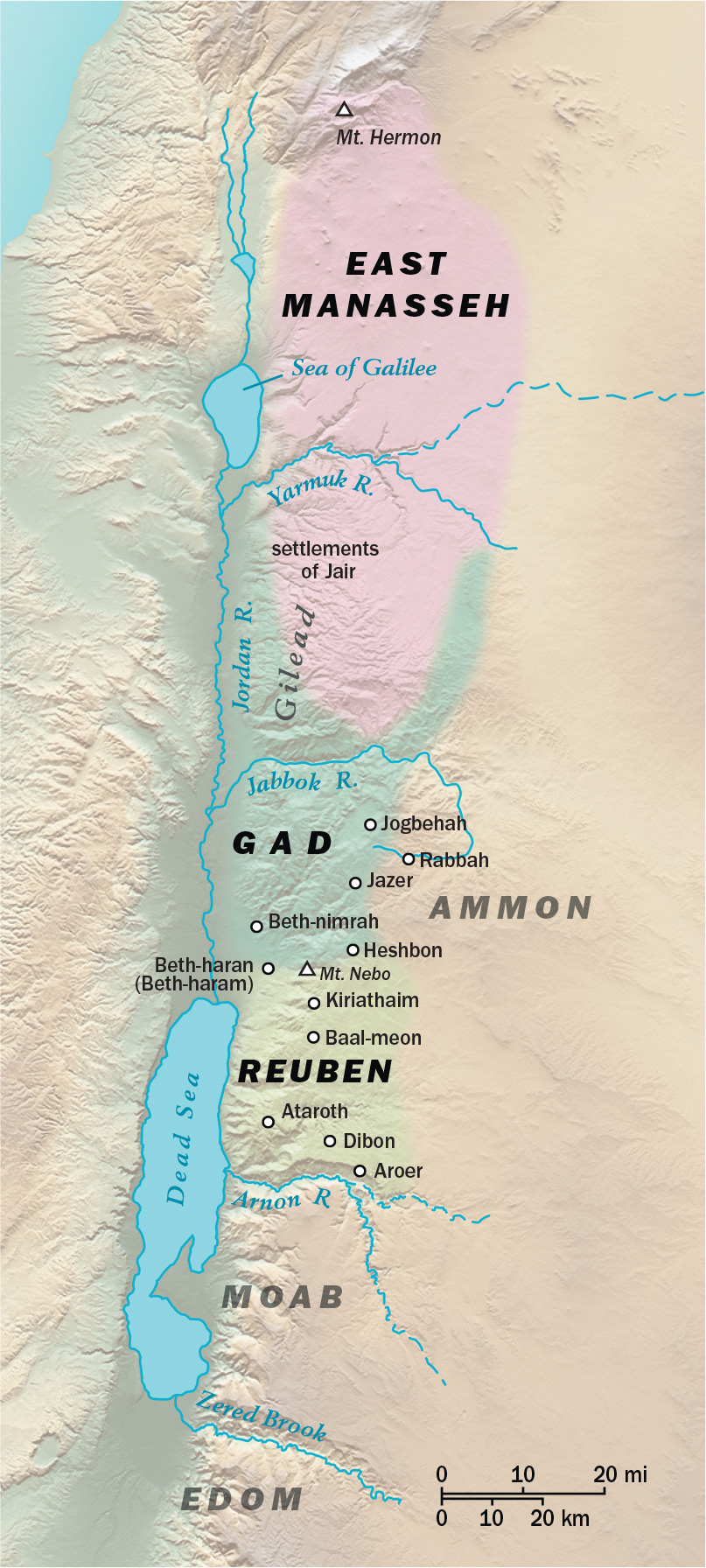

In Nm 21 the Israelites gain control of the eastern side of the Jordan by defeating King Sihon and King Og. The route of this campaign is shown here.

G. Balaam’s failed attempts to curse Israel (22:1–24:25). 22:1–6. Undaunted by opposition, the Israelites continue northward through Moabite territory to a location across the Jordan River from Jericho, within striking distance of Canaan. Balak, king of Moab, is understandably alarmed, particularly because Israel has defeated Sihon (22:1–4), who previously defeated Moab (Nm 21:26). He does not know that God has instructed Israel not to disturb the Moabites or Ammonites, who are their relatives descended from Lot (Dt 2:9, 19). So Balak, allied with Midianites, attempts to hire Balaam to weaken Israel by cursing her so that his army can prevail against this intruder (22:5–6). A curse invoking supernatural intervention was a kind of weapon in the ancient Near East, potentially of mass destruction, which explains why curses were taken so seriously in biblical law (Ex 21:17; Lv 20:9; 24:15; Nm 5:18–27). [Sorcery and Divination]

22:7–21. Balaam enjoyed an international reputation as an effective prophet and diviner. He was from Aram in northern Mesopotamia (northeastern Syria, three to four hundred miles from Moab; Nm 22:5; cf. 23:7; Dt 23:4) and communicated with the Lord of the Israelites (22:8–12). Perhaps he knew the Lord through their Aramean relatives (cf. Gn 25:20; 28:5; 31:24; Dt 26:5).

Balaam initially obeys God, who forbids him to curse the Israelites because they are blessed (22:12–13; cf. Gn 12:2–3; 22:16–18). God gives him permission to go with Balak’s second delegation if the men come to call him. In the morning Balaam goes with them, but God is angry with him for doing so (22:20–21). This could be because God is testing him by permitting him to have what he wants, but he makes a bad choice (cf. chap. 11 and the provision of meat for Israelites at Kibroth-hattaavah). More likely, however, the messengers set out to return home without calling him and he took off after them anyway, violating the Lord’s condition. This would explain why he is accompanied only by his two servants, why he is so upset when his female donkey slows his hot pursuit, and why God is so angry (22:22–33).

22:22–40. This episode involving the donkey is full of irony. The donkey sees what the seer or visionary does not: the angel of the Lord blocking the way (22:22–27). When the donkey miraculously speaks, Balaam dialogues with her as if this were a usual occurrence, and she has the better of the argument (22:28–30). Balaam accuses her of treating him badly and says he would kill her if he had a sword, but she saves his life from the sword of the angel (22:33). When the Lord opens Balaam’s eyes and he sees the angel, he prostrates himself on the ground (22:31), a similar reaction to that of his donkey the third time she saw the angel. Once the distinguished prophet is blinded by profit and sets out to destroy Israel, he is diminished to a level below that of a donkey.

When he meets Balak, Balaam makes it clear to the king that he is bound by what God will put in his mouth (22:38; cf. 22:20, 35). This is Balaam’s escape clause: If he should fail to curse Israel, it is not his fault.

22:41–23:26. Balak takes Balaam to Bamoth-baal, “The High Places of Baal,” where he can see the edge of the Israelite community in order to aim his curses by line of sight (22:41). This is the first of three attempts to have Balaam curse Israel (22:41–23:12; 23:13–26; and 23:27–24:13). On each occasion, Balak takes Balaam to a vista point where he can see the Israelite encampment, Balaam directs Balak to build seven altars there and offer sacrifices to invoke the Lord, and God gives Balaam a blessing on Israel to pronounce in the hearing of Balak. Balak becomes progressively more angry, but Balaam keeps repeating his escape clause.

The NT mentions Balaam in a very negative sense three times (2 Pt 2:15–16; Jd 1:11; Rv 2:14).

Balaam’s inspired blessings do not say a negative word about the Israelites. To outsiders they are the chosen people whom God cherishes, blesses, and protects from curses. Their problems are strictly “in-house.”

Balaam’s first blessing is short (23:7–10). Its thrust is that he cannot curse the Israelites, a separate nation of numerous people, because God has not cursed them. His second speech (23:18–24) points out that God will not change his mind to bless Israel, and Balaam cannot undo his blessing. Furthermore, God is with them as their king in the midst of a royal war camp to protect them, including from occult attacks. He has brought them out of Egypt and is their strength in battle. This is a warning not to oppose them.

23:27–24:14. After two failed attempts, Balaam sees his opportunity to claim Balak’s reward slipping away. So the third time he does not go off by himself to seek the Lord, as he has before, but simply gazes toward Israel and intends to pronounce a curse without God’s interference (24:1; cf. 23:3–5, 15–16). But the Spirit of God comes upon him anyway (24:2; cf. Nm 11:26).

Balaam’s third blessing (24:3–9) begins by describing him as one who receives divine revelation through the senses of sight and hearing. The words “who falls into a trance with his eyes uncovered” (24:4) likely refer to his experience when he met the “angel of the LORD” (22:31). But they could also ominously allude to his downfall in spite of possessing extraordinary insight from God. His moral fall is already under way, and he is pursuing a perverse course with his eyes open, knowing what he is doing.

Balaam goes on to extol the magnificence of Israel’s encampment and to prophesy the greatness of her future king, who will be exalted above Agag, the later king of Amalek (1 Sm 15:8–9, 20, 32–33). The latter portion of this speech uses vivid imagery to expand on a theme of the second blessing: God is the strength of the Israelites, and they will destroy their enemies. The final words echo God’s blessing to Abraham: “Those who bless you will be blessed, and those who curse you will be cursed” (24:9; cf. Gn 12:3).

24:15–25. Three times Balaam has attempted to strike the Israelites. From Balak’s perspective, Balaam has struck out and is fired (24:10–11). Before leaving, Balaam gives Balak a bonus cluster of four oracles (24:15–24), bringing the total of his inspired speeches to seven. These four are prophecies of breathtaking scope, predicting fates of various peoples in the future and thereby introducing the biblical genre of oracles against nations (e.g., Am 1:3–2:3; Is 13:1–23:18; Jr 46:1–51:64; Ezk 25:1–32:32).

According to the first oracle, an Israelite monarch (“star,” “scepter”) will conquer Moab and its neighbor, Edom (24:15–19). King David will fulfill this (2 Sm 8). In the second oracle, Amalek will perish (24:20). Samuel and King Saul will accomplish this (1 Sm 15). The remaining oracles (24:21–24) are against the Kenites and Asshur (Assyrians or another group?) and mention ships from Cyprus afflicting Asshur and Eber. These verses present serious interpretive difficulties, but Balaam’s point seems to be further emphasis on the contrast between blessed Israel and other nations, which are not similarly blessed.

H. Apostasy with the Baal of Peor (25:1–18). 25:1–4. Balaam and Balak have parted ways (24:25), apparently for good. But Balaam returns to advise Balak (and undoubtedly claim a reward) to defeat the Israelites through another strategy (31:8, 16), which is recounted in chapter 25. Balaam understands that the Israelites’ blessing is conditional on their faithfulness to the Lord. If they can be enticed to worship another deity, the Lord will cease to protect them. To lure the Israelites into such worship, the Moabites deploy time-tested ways to a man’s heart: food and sex.

The diabolical plan works like a charm. Moabite women seduce Israelite men and invite them to sacrificial feasts, at which they participate in idolatrous worship of a local god, the Baal of Peor (25:1–3a). Thus they commit both physical and spiritual promiscuity. Consequently, God is angry with Israel (25:3b). He has warned the Israelites of this kind of danger (Ex 34:15; cf. Rv 2:14). The stakes are incredibly high. Apostasy of the former generation with the golden calf almost aborted his covenant with Israel (Ex 32). Now the next generation is derailed just before entering Canaan.

The tribal leaders are especially culpable for leading the way into disloyalty. To root out the evil (cf. Dt 13) so that the Lord’s retributive wrath against the whole nation will subside, the Lord commands that they be executed and their bodies exposed out in the open rather than buried (25:4; cf. 1 Sm 31:10; 2 Sm 21:3–14). Similar exposure by suspending an executed person’s body from a tree or stake meant that the individual was cursed by God (Dt 21:22–23; cf. Gl 3:13). Such shameful treatment would also serve as a deterrent.

25:5–9. Moses issues the execution order and weeps at the sanctuary with the other members of the community (25:5–6). They have several reasons to weep: apostasy, executions, and a divine plague (cf. 25:8). Just then Zimri, the son of a Simeonite chieftain, appears and brazenly brings Cozbi, daughter of a Midianite chieftain, to a tent chamber at the encampment of his relatives (25:6; cf. vv. 8, 14–15). No doubt their intention is sexual.

Phinehas, son of the new high priest, puts a quick end to the openly defiant offense by dispatching the couple with his spear. God accepts this act of retribution as expiation for Israel, and the plague abruptly ceases (25:7–8; cf. v. 13). This is not substitutionary atonement that benefits the wrongdoers but expiation in the basic sense of purging them from the community (cf. Lv 16:10; 2 Sm 21:3–6).

Before Phinehas’s vigorous action stops the virulent plague, 24,000 die (25:9). This is the highest body count from any divine punishment on the Israelites during the wilderness period, even much higher than the 14,700 slain in the aftermath of the revolt by Korah and company (Nm 16:49; but cf. 2 Sm 24:15—70,000 in the time of David). God holds members of the new generation accountable to learn from the experiences of their parents.

25:10–15. The Lord rewards the loyal zeal of Phinehas—which saves the Israelites from the Lord’s zeal in holding them accountable for an exclusive covenant connection with him—by giving him a covenant promise of a priestly dynasty (25:10–13). Compare the Lord’s reward for the Levite executioners at the time of the golden calf apostasy (Ex 32:25–29; Dt 10:8).

25:16–18. According to Dt 2:9, the Lord has told the Israelites not to fight the Moabites. But the Midianites, who are allied with Moab (Nm 22:4, 7), are under no such protection. Their complicity (as revealed by the role of Cozbi; 25:18) in triggering the destruction of a large number of Israelites by divine agency is tantamount to a declaration of war. So God declares war on them (25:16–17; cf. chap. 31). Of course, the fact that a high-ranking Israelite official kills the daughter of a Midianite chieftain would have made the Midianites even more hostile to Israel.

3. PREPARATION FOR OCCUPATION OF THE PROMISED LAND (26:1–36:13)

A. Organization of the younger generation (26:1–27:23). 26:1–65. The remaining chapters of Numbers focus on preparations for the Israelites to enter Canaan, including a census of the new adult generation, instructions for apportionment of territory, and more laws. A fresh census (Nm 26) is necessary for organization because the generation counted in the earlier census (chaps. 1–3) is now gone. The second census also verifies that only Caleb and Joshua remain of those numbered in the first census (26:64–65).

The census is undertaken after the plague (26:1), which has reduced the Israelites by 24,000. Nevertheless, the total of the military census (not counting Levites) is 601,730 (26:51), only slightly down from the total of 603,550 in the earlier census (1:46). Some tribes have fared better than others, no doubt largely due to the degrees of their loyalty or disloyalty to God. The size of territories allotted to tribes in Canaan is to be proportional to their populations (26:52–56). This indirectly ties land awards to behavior during the wilderness period.

Numbers 26 includes genealogical review, in order to outline tribal structure, as well as some brief historical notes. One of these notes provides startling new information: when Korah, Dathan, and Abiram and their families perished (26:9–10; cf. 16:27–35), Korah’s sons (named in Ex 6:24) did not die (26:11). No explanation is given, but presumably they separated themselves from the rebellion in some way. So in spite of everything, Korah’s line continued and his descendants composed a number of psalms (Pss 42; 44–49; 84–85; 87–88).

27:1–11. Regarding allocation of tribal land, the daughters of Zelophehad (27:1) recognize a problem for their family. Their deceased father is survived only by daughters, who are not eligible to inherit part of Canaan. Consequently, he will be posthumously punished by having no part of the promised land to which his name will be attached in order to perpetuate his memory (27:2–4a; cf. Ru 4:1–22). The solution they propose calls for them to inherit their father’s possession along with their uncles (27:4b). Moses brings their case to the Lord, who rules in their favor and expands this legal precedent to cover related cases of inheritance in the future (27:5–11; cf. 9:6–14).

27:12–23. Moses knows that he, like Zelophehad, will not enter Canaan, because of the debacle at the waters of Meribah, meaning “Quarreling” (20:12–13). Now God reminds him of this and tells him to ascend a mountain belonging to the Abarim range on the western side of the Moabite plateau, which includes Mount Nebo. From there he will see the promised land and then die, as Aaron has (27:12–14; cf. 20:23–29; Dt 32:49).

Since Moses’s end is near, he petitions God to appoint his successor so there will be a smooth transition of leadership and Israel will not be vulnerable. The Lord designates Joshua, “a man who has the Spirit in him” (27:15–18a). Joshua has the right experience as Moses’s assistant (cf. Ex 24:13; 33:11; Nm 11:28), Israel’s military leader (Ex 17:8–13), and a faithful scout (Nm 13–14). But the Spirit is his most essential qualification.

Moses follows God’s directions by transferring some of his authority to Joshua so that the Israelites will follow his leadership. The ceremony is simple and clear: Moses lays his hands on Joshua, as a gesture of transfer, and commissions him before the high priest and the community (27:18b–23; cf. Ac 6:3–6). Moses shares power with Joshua until he dies not long after this (Dt 34). Then Joshua is dependent on the high-priestly oracle of the Urim and Thummim for divine guidance (27:21; cf. Ex 28:30) because he cannot communicate with the Lord face to face, as Moses did (Nm 12:8; Dt 34:10).

B. Calendar of communal sacrifices (28:1–29:40). Following the Baal of Peor episode (Nm 25), chapters 28–29 supplement the liturgical calendar of Lv 23 and thereby remind the Israelites of their worship obligations to the Lord (cf. Nm 15). Numbers 28–29 specifies public sacrifices (with grain and drink accompaniments) to be offered for all Israel on particular days of the year. The order is the same as in Lv 23, moving from smaller to larger time cycles and progressing through the annual festivals from spring to autumn.

28:1–8. Leviticus 23 begins its list of sacred occasions with the weekly seventh-day Sabbath (Lv 23:3), but Nm 28 first reiterates Ex 29:38–42, regarding the foundational sacrifice of the ritual system: the morning and evening regular burnt offering, performed every day of the year (Nm 28:3–8).

All other sacrifices are in addition to the daily burnt offering of two male yearling lambs, which serve as “food” for God (28:2). Other ancient Near Eastern peoples fed their gods twice per day, but the Lord only “enjoyed” his daily food as a token of human faith in the form of smoke; he did not need nourishment from it (cf. Ps 50:12–13).