1–2 Samuel

1. A PERIOD OF TRANSITION (1 Sm 1:1–15:35)

After the turbulent days of the judges, the people of Israel are looking forward to better times. The economic and spiritual condition of the nation is deplorable, even though the Lord dwells among his people and has appointed the priests to be their leaders.

A. Eli and Samuel (1:1–7:17). 1:1–8. Samuel’s importance can be seen in the lengthy account of his birth (1:1–2:11). There are no birth narratives for Saul and David, even though they are kings. The story of Samuel’s birth is a testimony to the faith of his mother, Hannah. Like Sarah and Rachel, Hannah has great difficulty becoming pregnant (1:2), and barrenness was considered to be a mark of the Lord’s disfavor. To make matters worse, her husband, Elkanah, has another wife, and she has several children and taunts Hannah the way Hagar scorned Sarah (1:6–7; see Gn 16:4). Although no reason is given for Hannah’s barrenness, it is likely not the result of some sin, for 1:3–8 tells how she often accompanies her husband to the house of God. The yearly festival (1:3) might be the Festival of Shelters, celebrated at the end of the summer to commemorate God’s provision for Israel in the Sinai desert after the exodus (Lv 23:43) and to give thanks for the summer harvest.

1:9–18. Though deeply discouraged, Hannah takes her problem to the Lord and to the high priest Eli at the tabernacle, which at that time was located at Shiloh, about twenty miles north of Jerusalem (1:9). In great earnestness, Hannah makes a solemn promise that if the Lord will give her a son, she will dedicate him to the Lord’s work (1:11). Hannah effectively places her son under the restrictions of a Nazirite vow, which also involved total abstinence from the fruit of the vine (Nm 6:1–3). Long hair was a symbol of an individual’s commitment to the work of the Lord.

Through her vow (1 Sm 1:11), Hannah voluntarily places Samuel in the same position in which God put Samson, whose mother had also been sterile for years (Jdg 13:3–5). Though the Nazirite vow was normally for a limited period, both Samson and Samuel are committed from before birth to be Nazirites for life.

Eli watches as Hannah prays, concludes that she is drunk, and admonishes her accordingly (1:12–14). But Hannah is not drunk; she is simply absorbed in her anguished prayer (1:15–16). To Eli’s credit, once he realizes his mistake, he blesses her (1:17). But Eli’s mistaken assessment is an important signal for the audience: it is used by the historian to indicate Eli’s lack of discernment (which is also seen in his inability to deal with his sons) and to comment on the spiritual condition of Israel in general.

1:19–20. On Hannah’s return home to Ramah (about five miles north of Jerusalem), “the LORD remembered her,” as he had remembered the barren Rachel centuries earlier (1:19; see Gn 30:22). In due time Hannah gives birth to a son and names him Samuel. There is a wordplay in the Hebrew text, but missed in English, that the historian has used to foreshadow the prophet-versus-king theme mentioned in the introduction. When Samuel is born, Hannah names him so because she has requested him from the Lord (1:20). Even though the explanation suggests as much, the name Samuel does not sound like the Hebrew word for “requested” or “asked,” which is a theme word in the section (see also 1:27–28). Instead, the name Saul means “Requested,” and Samuel perhaps means “His Name Is El” (although the name’s precise meaning remains obscure). However, the name Samuel also sounds similar to the phrase “God had heard,” so there might be a subtle wordplay intended. The name itself might connect the son to God’s merciful answer to Hannah’s request. The explanation for the name that the historian gives in the text subtly contrasts Samuel with Saul and thus foreshadows God’s (and the historian’s) opinion that a good prophet is always better than a monarch.

1:21–28. After the birth of Samuel, Elkanah returns to Shiloh to offer the annual sacrifice in fulfillment of a vow he has made. Hannah does not accompany her husband but nurses Samuel until he is weaned, probably at three years of age (1:21–23). True to her promise, she then brings him to the tabernacle and turns him over to Eli (1:24–28). On this occasion she also sacrifices a bull in fulfillment of her vow (Nm 15:8–10) and reminds Eli that she has prayed for a child in his hearing. Here the emphasis is not on the Nazirite vow (1:11) but on the surrender of the child for service “as long as he lives” (1:28).

2:1–11. While still at the sanctuary, Hannah again prays to God, this time lifting her heart in praise of his goodness. She rejoices not so much in her son, Samuel, but in the Lord who has given him to her: he is the “rock,” the all-powerful God who provides security for his people (2:2). Hannah testifies that God humbles the proud and the rich and exalts the weak and the poor (2:3–9). The final couplet of Hannah’s song (2:10) is used to foreshadow Samuel’s role in establishing a monarchy for the Israelites.

Hannah’s prayer highlights the reversals that God brings as he humbles the mighty and exalts the lowly (1 Sm 2:4–8). Mary will later mention these same reversals in her song of praise (Lk 1:51–53). For both Hannah and Mary it is the birth of a son that brings such great blessing.

2:12–17. One of the saddest episodes of this part of the story is the disintegration of the family of Eli (2:12–36). The weakness and gloom of Eli contrast sharply with the faith and joy of Hannah. If the sons of the priest are “wicked men,” the condition of the nation is desperate indeed (2:12). Ironically, Eli’s sons sin in the way they handle the sacrifices (2:13–14)—the very animals brought to make atonement for sin! According to the law of Moses the priests were allowed to eat part of the meat of the sacrificial animals (except for the burnt offerings), but certain restrictions applied (Lv 7:31–37). The fat was always considered the Lord’s portion and had to be burned on the altar (Lv 3:16). Yet Hophni and Phinehas take the meat before the fat is burned and apparently ignore the custom of boiling the meat (2:15). In spite of the complaints of the people, the priests refuse to change (2:16–17). Such an attitude brought death to two of Aaron’s sons several centuries earlier (Lv 10:1–3).

2:18–21. In sharp contrast to the sin of Eli’s sons are the Lord’s blessings on Samuel and his family. Once a year Samuel’s parents visit him, and his mother brings a robe that she has made (2:19). Apparently he wears this under the linen ephod (2:18), an apron-like garment worn by all the priests (1 Sm 22:18). On one of the early visits, Eli blesses Elkanah and Hannah with the promise of additional children (2:20). Over the years three sons and two daughters are born to Hannah (2:21).

2:22–26. Faced by the mounting reports about the wicked deeds of his sons, Eli directly confronts them (2:22–25a). Among other things, they are guilty of sexual immorality with women who serve at the entrance to the tabernacle. Such women are mentioned only in Ex 38:8, but the exact nature of their function is not given. It is possible, though unlikely, that they were temple prostitutes like those present in Canaanite shrines to promote the overall fertility of the land (Nm 25:1–3), even though this practice is forbidden in Dt 23:18. Oblivious to their father’s belated warnings, Eli’s sons continue in their sinful ways (2:25b). And for the second time in the chapter, Samuel’s behavior is directly compared with that of Eli’s sons (2:26): in contrast to Hophni and Phinehas, as he grows up Samuel pleases both God and people.

2:27–36. That God will not let Eli’s sons’ behavior—or Eli’s failure to rein them in—go unpunished is confirmed by a visit from an unnamed prophet. Called “a man of God” (2:27a; cf. 9:6, 10), this prophet makes it clear that part of the blame is Eli’s—he honors his sons more than God by failing to oppose their sinful ways (2:27b–29).

In light of the unfaithfulness of Eli’s sons, the prophet announces that disaster will strike Eli’s family, and his descendants will not live out their days peacefully (2:30–34). This prediction is fulfilled when Eli’s sons—Hophni and Phinehas—both die on the same day (4:11), a grim parallel to the sudden death of Aaron’s sons Nadab and Abihu (Lv 10:1–3). Instead of having choice parts of meat from the sacrifices, Eli’s descendants will have to beg for “a loaf of bread” (2:36). Honor and prestige will be replaced by disgrace and poverty.

3:1–10. Samuel’s calling is told in chapter 3. For the third time in the book, we read that Samuel serves the Lord (3:1; cf. 2:11, 18). He functions as a kind of apprentice priest, and at this point he is probably about twelve years old. The Lord begins to speak to Samuel one night while he is sleeping in his usual place near the tabernacle. Apparently it is close to dawn, because 3:3 mentions that the golden lampstand in the holy place is still burning. Every evening olive oil was brought in to keep the lamps burning until morning, when the flame either grew dim or went out (Ex 27:20–21; 2 Ch 13:11). The ark of the covenant was in the most holy place, and it was from the ark that God used to speak with Moses (Nm 7:89). In this setting, then, it is altogether fitting for God to call a new Moses to lead his people. At first, Samuel thinks that Eli is calling him, but after Samuel has made three trips to Eli’s bed, the aged priest realizes that God is calling the boy (3:4–9).

3:11–21. Unfortunately for young Samuel, and especially for Eli, the divine message is one of judgment against Eli. Action that makes the ears tingle (3:11; see the CSB footnote) is nothing short of catastrophe, and destruction lies ahead for Eli’s family (3:12). Eli has failed to restrain his sons (3:13), who treat the Lord with much contempt, even though he did try to warn them (2:22–25). They will never be forgiven for their stubborn rebellion, regardless of the number of sacrifices they handle (3:14).

Having observed Eli’s sons in action, Samuel may not be surprised at the severity of the Lord’s message, but he must wonder what he should tell Eli (3:15). This problem is solved when Eli uses a curse formula to insist that Samuel tell him everything (3:17). When Samuel complies, Eli accepts God’s sentence (3:18) and reacts the way Hezekiah does when he learns that his descendants will be exiled to Babylon (Is 39:8). In an era when “everyone did whatever seemed right to him” (Jdg 21:25), God takes appropriate measures to judge the wicked. Since Samuel’s account of God’s revelation is the same as the announcement the man of God gave to Eli (2:27–36), Eli has no doubt that God has spoken to Samuel. As time goes by, Samuel’s message is fulfilled (3:19). Chapter 3 begins with the observation that visions are given only rarely (3:1), but it ends with a reference to God’s repeated revelations to Samuel (3:21). Here is a young man through whom the Lord will speak to his desperate people.

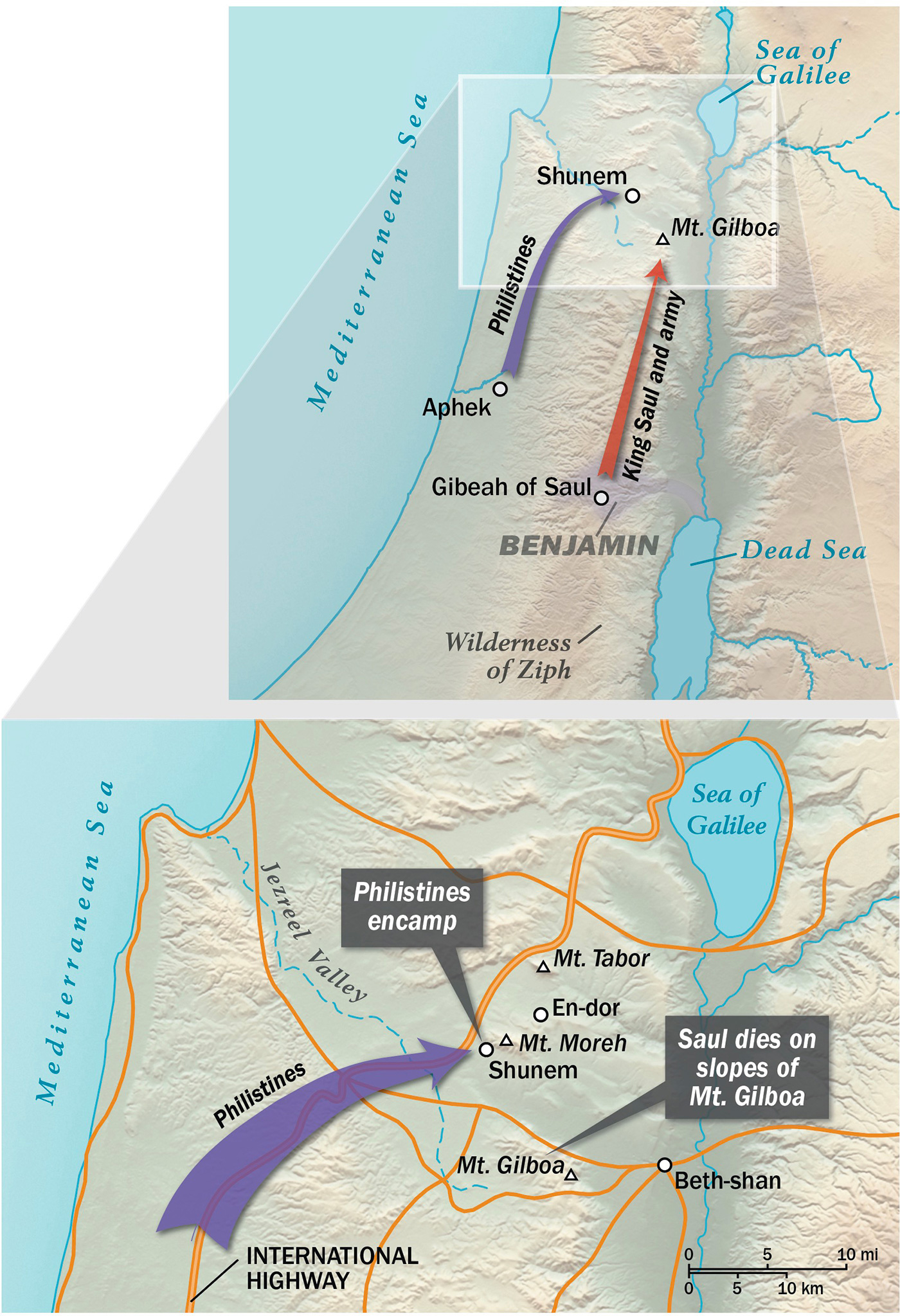

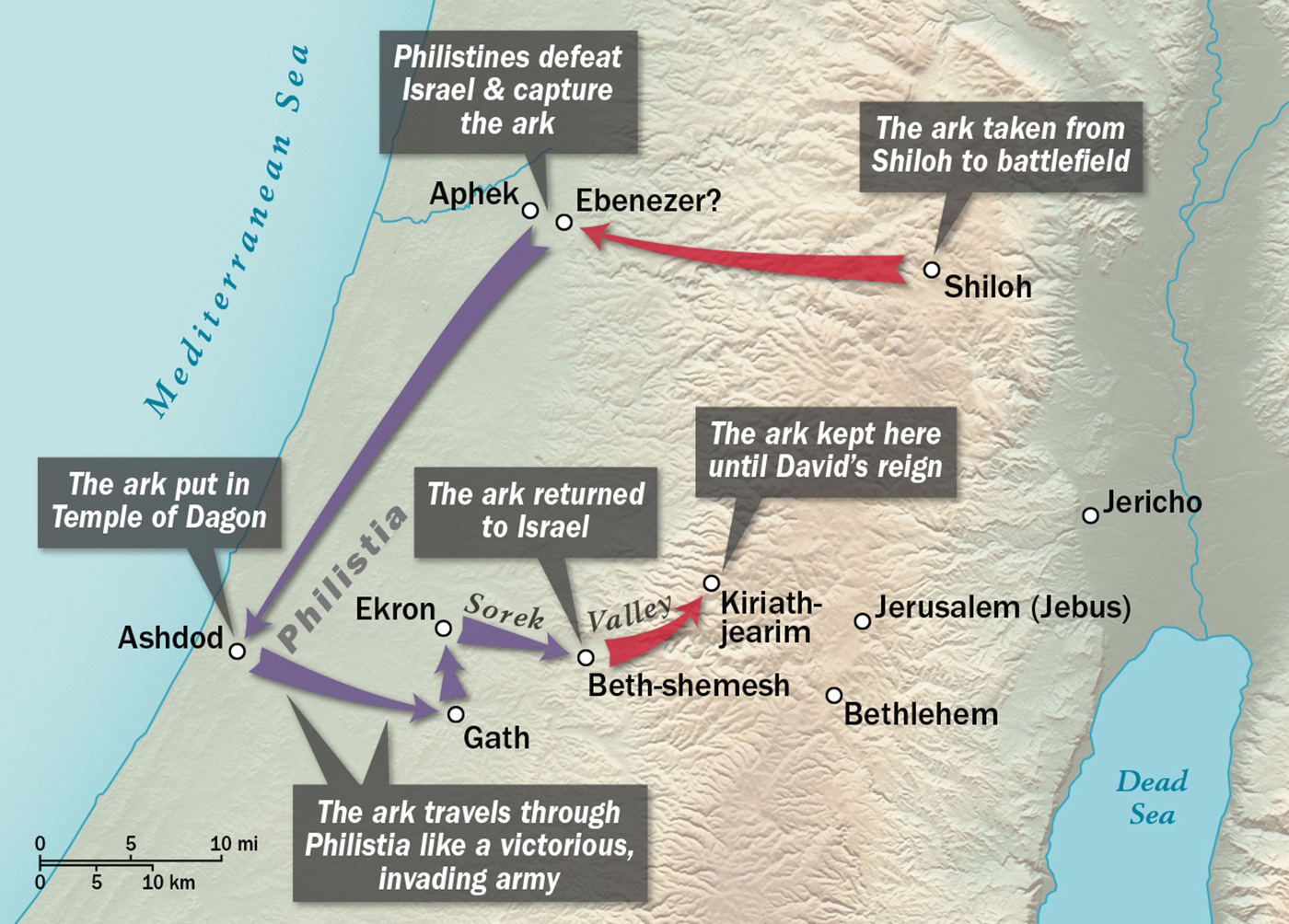

4:1–11. In fulfillment of the prophecies of chapter 3, Eli’s family suffers a devastating blow in the wake of a battle with the Philistines some years later. The conflict takes place near Aphek (4:1), a city about twenty miles west of Shiloh and somewhat north of the main Philistine territory along the Mediterranean Sea. According to Jdg 13–16, the Philistines controlled the tribe of Judah and were putting pressure on tribal regions to the north. Unlike Samson, Israel’s army cannot gain the victory and in fact loses about four thousand (or four “companies” of) men (4:2). (Note that the Hebrew word for “thousand,” elep, may also mean “company [of men]” as well as a “tribal clan.”)

Distraught, the rest of the soldiers wonder why the Lord has abandoned Israel (4:3a), for they—like the surrounding nations—believe that the people with the strongest gods win battles (1 Kg 20:23). The soldiers recall how the ark of the covenant accompanied Israel’s armies when they crossed the Jordan River and defeated the city of Jericho (Jos 3:11, 17; 6:6, 12). The ark was God’s footstool and symbolized his presence more than any other part of the tabernacle. Thus, the men reason that the ark will guarantee victory over the Philistines (4:3b–5). The Philistines likewise believe that the presence of the ark is a bad omen, for they have heard about the plagues with which the Lord afflicted Egypt (4:6–9).

In reality the Philistines have little to worry about, for the ark is not a magical talisman; its mere physical presence cannot compel the Lord to give Israel a victory—especially when Eli’s two wicked sons, Hophni and Phinehas, accompany the ark to the battlefield. Their presence dooms Israel, and in the ensuing battle an additional thirty thousand (or thirty “companies” of) men die, including Eli’s two sons, and the ark is captured (4:10–11). It is an unmitigated disaster.

4:12–22. Eli’s family suffers disaster as well. A messenger whose clothes are torn and who has “dirt on his head” brings news of Israel’s defeat to Shiloh (4:12). When Eli hears the commotion, he asks what has happened (4:14). According to 4:13, Eli had serious misgivings about taking the ark to battle. Old and feeble at age ninety-eight (4:15), Eli falls off his chair and breaks his neck when he hears the extent of the catastrophe, especially the news about the capture of the ark (4:18a). This is worse than the report that his own two sons have been killed (4:17). Following the style of the book of Judges, the author notes that Eli “had judged Israel forty years” (4:18b), and his leadership had proved ineffective.

The Travels of the Ark of the Covenant in 1 Samuel 4–6

Death continues to stalk Eli’s family: his daughter-in-law dies in childbirth after learning what has happened to her husband and father-in-law (4:19–20). Before succumbing, she names her baby boy Ichabod, meaning “Where Is Glory,” because of the capture of the ark (4:21–22). It is as though the cloud of glory that normally fills the most holy place around the ark has left Israel. Since the Lord was “enthroned between the cherubim” above the ark (4:4), the loss of the ark symbolizes graphically his abandonment of Israel. He has refused to be manipulated by his own people.

5:1–12. After their triumph over Israel, the Philistines intend to celebrate their good fortune, but the Lord has other plans. After its capture, the ark is taken to the coastal city of Ashdod, about thirty-five miles west of Jerusalem and one of the five main centers of the Philistines (5:1). There they place it in a temple beside the image of Dagon, a god of grain worshiped in many parts of the Fertile Crescent and the Philistines’ leading deity (5:2). According to popular theology, Israel’s defeat would have meant that Dagon was more powerful than Yahweh, but the ensuing events illustrate for the audience the power of Israel’s deity. Twice the image of Dagon topples to the ground before the ark, and the second time Dagon’s head and hands break off (5:3–5).

Meanwhile, the Lord afflicts the people of Ashdod with tumors of some sort, and the disease follows the ark when it is sent to Gath, a city several miles to the east (5:6–9). Death comes to many, and the people panic, as do the residents of Ekron (about eleven miles northeast of Ashdod) when they receive the ark (5:10–12). The spread of the plague confirms the original reaction of the Philistines when the ark was brought into the Israelites’ camp (4:7–8). They have heard how Israel’s God struck the Egyptians with terrible plagues, and now they are experiencing a similar plague firsthand (cf. 6:6). Instead of having a prized trophy of victory, the Philistines possess an instrument of judgment that demonstrates the power of the Lord and the corresponding weakness of Dagon.

6:1–9. After seven difficult months, the Philistines are ready to send the ark back to Israel. But they want to make sure they do not offend Yahweh any further, so they consult with their religious leaders (6:1–2). The leaders urge them to send a gift with the ark to compensate for the way they have dishonored Israel’s deity (6:3). This guilt offering consists of “five gold tumors and five gold mice” (6:4–5a), representing the five main cities of the Philistines and reflecting the symptoms and likely medium of the plague (that is, rodents may have carried the disease as a bubonic plague). Through this offering and the return of the ark, the Philistines hope to bring an end to the plague (6:5b–6).

To carry the ark, the priests suggest that a new cart be used, one that is ceremonially clean. The cart is to be drawn by “two milk cows that have never been yoked” (6:7a). According to Nm 19:2, in some cases a cow was not to be used in a sacrifice if it had been under a yoke. In relation to the new cart, it was likely a common ritual belief that the most appropriate instrument for dealing with a sacred object was something new—that is, something not used for nonreligious purposes. The two cows not only were usable for sacrificial purposes but may have been used by the Philistines as divination tools. If two cows would walk away from home and their unweaned calves and do so pulling a cart, even though they had never been yoked, then it would be clear (and it was!) that the Hebrew God was behind the entire event (6:7b–9).

6:10–18. When the Philistines hitch the cows to the cart and send them on their way, the cows head straight up the Sorek Valley to Beth-shemesh, a city of Judah close to the Philistine border (6:10–12). The implication of the cows’ actions would be obvious to the Philistines: the Israelite God has indeed been against them. Providentially, Beth-shemesh is also a city belonging to the priests (cf. Jos 21:16), who are responsible for the ark of the covenant. The people are harvesting wheat (6:13a), which usually took place in May or June. When they see the ark they are overjoyed and proceed to sacrifice the cows as a burnt offering (6:13b–14). They place the ark on a large rock, which becomes a monument to this event (6:15, 18).

6:19–7:1. Tragedy strikes, however, when God puts seventy persons to death for looking into the ark (6:19). According to the law of Moses, the sacred articles of the tabernacle are to be treated with great reverence. Not even the Levites can look at the holy things without risking death (cf. Nm 4:20). Since the ark is the most sacred object and since it is closely associated with the presence of God, access to it is very restricted. Even the high priest himself cannot look into the ark without endangering his life, a reminder that being in the presence of God requires ritual purity.

Distraught at the death of these people, the rest of the townspeople follow the example of the Philistines and look for another city where they can send the ark (6:20). Kiriath-jearim, located about fifteen miles northeast of Beth-shemesh, accepts the ark, and a man named Abinadab is given custody of it (6:21–7:1). The ark is not put back in the tabernacle probably because of the destruction of Shiloh by the Philistines. Although the tabernacle itself is moved in time, it will not have a more permanent home for many years.

7:2–6. Approximately twenty years elapse before the Israelites gain any lasting relief from Philistine oppression (7:2). Finally, Samuel senses that a genuine repentance is under way, so he challenges the people to rid themselves of their “foreign gods” (7:3–4). Throughout the period of the judges, many Israelites have worshiped these deities. Baal was the Canaanite god of rain and agriculture and, ironically, was sometimes described as the son of Dagon. The Ashtoreths were female deities such as Astarte (the Babylonian Ishtar), goddess of fertility, love, and war. As in Jdg 10:16, the Israelites stop worshiping these gods and return to being loyal to the Lord. Samuel gathers “all Israel” at Mizpah, about seven and a half miles north of Jerusalem, and promises to pray for them (7:5). As they fast and confess their sin, they pour out water before the Lord (7:6), perhaps symbolic of their earnestness and wholehearted commitment to God.

7:7–12. Believing that the Israelites have gathered at Mizpah for military reasons, the Philistines march up to attack them (7:7). In light of their repentant attitude, the people of Israel beg Samuel to pray for them, which he does; he also sacrifices a burnt offering (7:8–9). True to his covenant promise, the Lord intervenes on behalf of his beleaguered people and thunders against the Philistines (7:10). Apparently the Lord sends a storm similar to the ones that routed the Amorites (Jos 10:11–12) and bogged down the chariots of Sisera (Jdg 5:20–21). Thunder, hail, and heavy rain cause panic among the Philistines and send them fleeing to the west and south (7:11). Recognizing that it is the Lord’s victory, Samuel sets up a stone as a monument and calls it Ebenezer, which means “Stone of Help” (7:12).

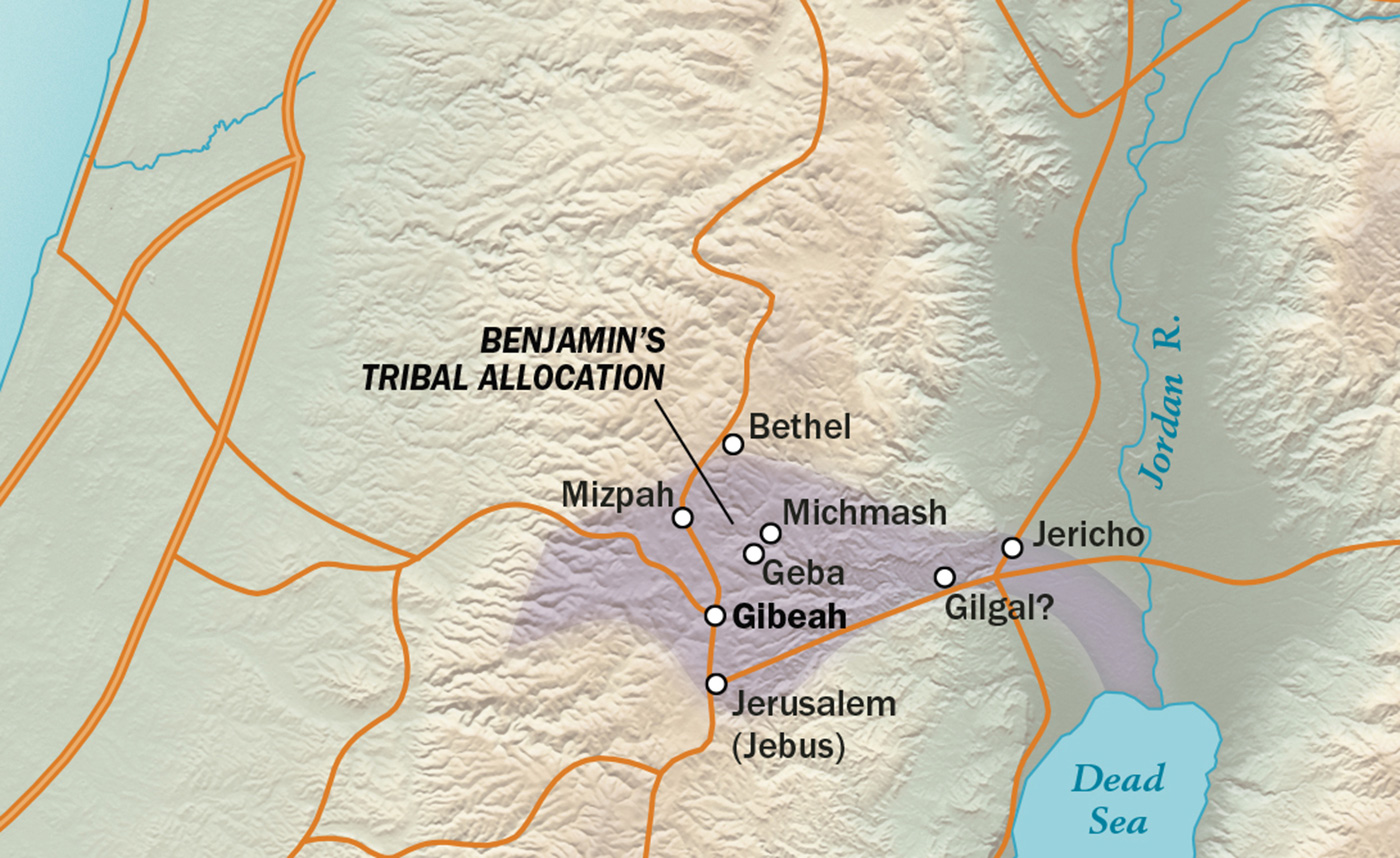

7:13–17. After this victory, the Israelites gain the upper hand over the Philistines and at least temporarily put an end to Philistine oppression (7:13–14). During this time of peace, Samuel travels to many towns in the tribe of Benjamin, serving as a judge and spiritual leader (7:15–16). Since Samuel ministers as a priest and prophet, he builds an altar to the Lord in his hometown of Ramah (7:17).

Here we can identify a literary strategy that the historian has continued from the books of Joshua and Judges: events that may have focused on one or two tribes or concerned a small regional conflict are placed in the context of the entire people and country. In 1–2 Samuel this literary device is used to broaden the scope of Samuel’s reputation and authority. For instance, Samuel’s yearly circuit as a judge is limited to Bethel and Mizpah, in the central hill country down to Gilgal, near Jericho in the Jordan Valley (7:16). Yet he is said to have gathered “all Israel” at Mizpah (7:5), and the historian asserts that “all Israel from Dan to Beer-sheba” knows of Samuel’s prophetic abilities (3:20). What this information illustrates is the historian’s interest in making clear that events and people associated within a limited area often have broader implications for the entire nation.

B. The early years of Saul’s reign (8:1–15:35). Even though Samuel has led the people well as a judge, he will be the last to hold this charismatic office. Under pressure from the people, Samuel anoints Saul as the first king and thereby ushers in a new era of Israel’s history. Saul’s initial years as king are promising, and it appears that the unified nation will be a powerful one.

8:1–9. Unlike most judges, Samuel appoints his sons to succeed him (8:1–2), but, like Eli before him, Samuel proves to be an unsuccessful parent: his sons are dishonest and create serious problems for both Samuel and the nation (8:3). Using the misconduct of Samuel’s sons as a pretext, the elders ask Samuel to appoint a king over Israel (8:4–5). They want what they perceive to be the stability and strength of a monarchy, as in the nations around them. By this request the people effectively reject the leadership of Samuel and, more important, the kingship of the Lord (8:6–7). From the standpoint of faith, the people choose to remove themselves one step from trust in God, with a human monarch standing between them and their divine King. Thus the Israelites repeat the mistakes of their past, for their ancestors made a similar choice at Mount Sinai, instructing Moses to listen to God and speak for them while they stood at a distance (Ex 20:18–21).

8:10–22. To help the people see the implications of their request, Samuel tells them what it will be like to have a king. Using the policies of other ancient Near Eastern kings as a pattern and reflecting a similar caution in Dt 17:14–20, Samuel warns the Israelites how their sons and daughters will be drafted into the king’s service and how government officials will take control of fields and vineyards (8:11–14). In addition to the tithe required by the law of Moses, the king will demand an additional 10 percent of crops, flocks, and livestock (8:15–17). Samuel asserts that eventually the people will feel like the king’s slaves and will cry out to God for relief, just as they have cried for help during times of foreign oppression (8:18).

Ignoring the urgency of Samuel’s arguments, the people remain firm in their desire for a king (8:19–20). Their minds are made up even though Samuel has pointed out the painful consequences of establishing a monarchy. When Samuel takes their decision to the Lord, God tells him to “appoint a king for them” (8:21–22).

9:1–13. The Lord’s choice is a man named Saul, who belongs to a prominent family from the tribe of Benjamin (9:1–2a). He is tall—a head taller than anyone else (9:2b)—but he is looking for lost donkeys and not a crown when he encounters Samuel (9:3). After searching the tribal areas of Ephraim and Benjamin, Saul is ready to give up the search, but his servant suggests that they consult a highly respected man of God (9:4–6). Fortunately the servant has a small amount of silver to give to the prophet (9:7–8), for payment of some sort was customary (see 1 Kg 14:3). When the two men ask about the prophet, they are told that he is on his way to bless a sacrifice at the local high place (9:11–13), a shrine located on a hill.

Saul is introduced as one looking aimlessly for his father’s lost donkeys, while David is introduced as one who is caring for his father’s sheep. The contrasts between these two are many and are emphasized throughout the narrative.

9:14–10:1. Unknown to Saul, the Lord has told Samuel that he is to anoint a man from Benjamin as king of Israel the very day of their meeting (9:15–16). The Hebrew verb mashah, “to anoint,” from which the noun “messiah” (“anointed one”) is derived, is used of a king for the second time in the book in verse 16 (see 2:10). In Exodus it is priests who are anointed for service (Ex 29:7; 40:12–15), but from this point on “the anointed one” is usually the king. Anointing indicated that a person had been set apart for a particular task and that the Lord would enable the person to perform the appointed task. The anointing oil was a symbol of the Holy Spirit, who empowers both Saul and David after they are anointed (see 1 Sm 10:6; 16:13).

Note also the reason that the Lord gives Samuel for anointing a king, the day before Saul shows up (9:16). Similar language is used in connection with God’s call to Moses in Ex 2:23. The intertextual allusion suggests that the historian viewed the establishment of the monarchy on par with the choice of Israel’s greatest leader.

When Saul meets Samuel, the prophet surprises him by announcing that the lost donkeys have been found and that the desire of “all Israel” is directed to Saul as the new king (9:20). Saul protests that the tribe of Benjamin is not very prominent (although it was neatly situated between the powerful tribes of Judah and Ephraim). During the period of the judges Benjamin was nearly wiped out in a civil war that seemed to end its influence permanently (Jdg 20:46–48). Like Gideon before him (Jdg 6:15), Saul protests that his clan is too small and insignificant to be considered for such an honor (9:21). But Samuel insists that Saul join the invited guests at the high place for a meal after the sacrifice, and Samuel reserves for Saul a choice part of the animal, the thigh (9:22–24). Normally the right thigh of fellowship offerings belongs to the priests (see Lv 7:33–34), so the people realize that Saul is in line for special honor.

Saul stays with Samuel that night, during which he likely receives instruction about his coming responsibilities and the challenges he will face (9:25). The next morning Saul and his servant prepare to leave, but Samuel sends the servant ahead while he gives Saul “the word of God” privately (9:26–27). Then, taking a flask of olive oil, Samuel pours it on Saul’s head and anoints him king (10:1). So begins Samuel’s key role as a king maker, and Israel’s monarchy is launched. A new era has begun.

10:2–8. Before Saul leaves, Samuel gives him some signs as further proof that God has indeed chosen him to be king. Samuel predicts the location at which Saul will meet various individuals and what they will do, demonstrating again that he is a legitimate prophet of the Lord (see Dt 18:21–22). The third sign is the most significant, for it deals with Saul’s empowering by the Spirit of God (10:5–7). A group of prophets will approach Saul playing musical instruments. While the band of prophets is prophesying, Saul will join with them and the Spirit of the Lord will come on him in power, just as it came on Othniel (Jdg 3:10), Gideon (Jdg 6:34), and Jephthah (Jdg 11:29). Each of these judges was designated as God’s chosen leader in this fashion, and the same is true for both Saul and David.

When God gives an individual an assignment, he also supplies divine power to perform that assignment. In Saul’s case Samuel indicates that he will be “transformed” (10:6), which likely refers to the ecstatic state or prophetic frenzy that will overcome Saul in the encounter with the Spirit of the Lord. The event might reflect the historian’s pro-prophet stance by asserting that some prophetic ability is necessary for a monarch to be acceptable. Whatever the precise significance, Saul recognizes that God is with him to bless and strengthen him.

Even though Saul will have the authority of a king, 10:8 is a reminder that he also needs to obey the word of God. At a forthcoming gathering at Gilgal—the sacred town near the Jordan River—Saul is instructed to wait a full week for Samuel to advise him.

10:9–16. The rapid fulfillment of signs leaves little doubt that God has spoken through Samuel. Saul’s participation in prophesying startles his friends, and they ask, “Is Saul also among the prophets?” (10:11–12). By this time the curiosity of Saul’s uncle has been aroused, but when he questions Saul about his visit with Samuel, Saul says nothing about the anointing (10:14–16).

10:17–27. As rumors about Saul begin to multiply, Samuel summons the people to reveal God’s choice of king. Before proceeding with the selection, however, he scolds the people for rejecting the Lord and reminds them that God has rescued them from Egypt and saved them out of all their calamities (10:17–19). Even with a king, Israel has to remember that it is God who is the source of their strength and salvation.

The selection of the king is probably accomplished through casting lots in conjunction with the Urim and Thummim handled by the priest (see Ex 28:30; 1 Sm 14:41–42). By this means the tribe of Benjamin and the clan of Matri are chosen, and finally Saul himself is singled out (10:20–21a). Knowing that he will be selected, Saul has hidden himself among the supplies (10:21b–22); this response foreshadows the type of character flaws and lack of faith that will come out later in his interactions with David. When Saul is finally presented to the people, they shout with enthusiasm, “Long live the king!” (10:24).

At this point, Samuel reminds the people of “the rights of kingship” (10:25), likely the same regulations, built on Dt 17:14–20, with which he tried to deter them from choosing a monarchy in 1 Sm 8:10–22. Given Samuel’s prophetic perspective on monarchy, the depositing of this document about kingship “in the presence of the Lord” suggests that above all the people and the monarch must remember who is the true King of Israel.

When Saul returns to his hometown of Gibeah he enjoys the support of many valiant men (10:26). The tribe of Benjamin was renowned for its excellent warriors, and now one of their number is king of the whole land. Some of the people are dubious about Saul’s abilities, however, and openly withhold their support (10:27).

11:1–5. Before long Saul has a chance to prove himself, when the Ammonites besiege the city of Jabesh-gilead, a town just east of the Jordan River, about forty miles northeast of the area of Benjamin (11:1–2). The Ammonites also lived in the Transjordan and had captured a large section of Israel’s territory before Jephthah drove them out (Jdg 11:29–33).

Note that the great Samuel scroll from the Dead Sea Scrolls provides a transition between chapters 10 and 11, a transition that most scholars take to be the original text that was lost by scribal errors (see the CSB footnote for 10:27). The material in the Samuel scroll makes sense of the rather abrupt beginning of chapter 11. From this lost piece we learn that Nahash has previously reconquered land in the Transjordan that belonged to Ammon before the Israelite tribes or Reuben and Gad laid claim to it. In order to preclude recrimination, he mutilates the men so that they will not be able to effectively lead future campaigns against him. During the fighting, seven thousand (or seven “companies” of) Reubenite and Gadite warriors flee north to the Gileadite city Jabesh-gilead. Nahash’s attack on that city is punishment for sheltering the warriors he has defeated, whom he now considers his subjects. His insistence on mutilation reflects the fact that those harboring his enemies deserve the same punishment.

Since the people of Jabesh-gilead have close family ties with the tribe of Benjamin (cf. Jdg 21:12–14) and since Saul has been appointed king over all the tribes, they appeal to Saul for help (11:4–5). Saul hears the news when he comes in from plowing the fields, an indication that his kingly responsibilities are not yet very extensive.

11:6–15. For the second time, “the Spirit of God suddenly came powerfully on him” (11:6; cf. 10:6, 10) as Saul, like the judges before him, goes into action against the enemy. Asserting his authority as king, Saul cuts up two oxen and sends the pieces throughout the land to indicate that death is in store for those who do not respond to the crisis (11:7; cf. Jdg 19:29–30). More than three hundred thousand (or three hundred “companies” of) soldiers gather (11:8). Following the strategy used by Abraham and Gideon, Saul surprises the enemy in the middle of the night and thoroughly defeats them (11:11). Jabesh-gilead is saved, and Saul is a hero.

On the heels of victory the people want to execute those who opposed the selection of Saul as king, but Saul refuses to go along with the idea (11:12–13). This is a day to rejoice, because God has given them a great victory. Samuel suggests that everyone assemble at Gilgal (11:14), the town near the Jordan where Joshua and his army celebrated the conquest of Canaan (Jos 10:43). There they present fellowship offerings to thank the Lord for his goodness to the nation and to confirm Saul as king (11:15).

12:1–5. Like Moses and Joshua, Samuel does not relinquish his leadership without challenging the nation to be faithful to the Lord (12:1–25). The theme of covenant renewal that characterizes the whole book of Deuteronomy and Jos 24 is emphasized once again in Samuel’s farewell.

Since the wickedness of Samuel’s sons was a factor behind the initial request for a king (cf. 8:3–5), Samuel begins his speech with an examination of his own conduct as leader (12:1–5). He challenges the people to point out any instance where he has wronged anyone or used his position for financial gain (12:3–5). By pointing to his own clean record, Samuel hopes to provide an example for Saul and future kings.

12:6–15. As Samuel seeks to establish the monarchy on a sound footing, he reminds the Israelites of the way God has provided for them in the past. When they cried for relief in Egypt, the Lord sent Moses and Aaron to deliver them from slavery (12:6–8). When their own sinfulness brought oppression in Canaan, God raised up heroes such as Gideon (Jerubbaal), Barak, and Jephthah to rescue them from the enemy (12:9–11). God would have saved them from the recent Ammonite attack even if no king had been appointed (12:12). Although the Lord used Saul to deliver Jabesh-gilead, the monarchy brings with it a new danger. Will the people put their trust in a human leader at the expense of their faith in the Lord? Samuel warns that both the people and the king must serve and obey the Lord (12:13–15). The covenant structure remains the same, for the Lord demands the unwavering allegiance of all the people.

12:16–18. To impress on the Israelites the evil inherent in their request for a king—and their rejection of God as King—the Lord sends thunder and rain in the dry season. The wheat harvest normally occurred in June, and it rarely rained in Israel during the summer. The people stand in awe as their forefathers did at Mount Sinai, when God revealed his power in thunder and lightning (Ex 19:16; 20:18). God spoke through Moses, and now he is speaking through Samuel, and the message must be taken seriously.

12:19–25. In 7:8 the people asked Samuel to pray when the Philistines attacked. Now that God has revealed himself they ask Samuel to pray for them again (12:19). Like the generation at Mount Sinai, they are afraid they might die. Samuel assures them that the Lord will not reject them, but he urges them to “worship the Lord with all your heart” (12:20; cf. 12:24). God has done “great things” for them (12:24), and he will continue to work wonders on their behalf (cf. Ps 126:2). And Samuel promises to keep praying for them and teaching them how to live (12:23). Although he is retiring as the military and judicial leader, he will continue to function as a prophet for the nation and as an adviser for the king.

13:1–7. After the victory over the Ammonites east of the Jordan, Saul turns his attention to the Philistines, Israel’s perennial enemy along the Mediterranean coast (13:1–14:46). Undoubtedly the Philistines are worried about Israel’s upstart king and likely want to attack him before he becomes too established and powerful.

Since the initial conquest under Joshua, the cities most solidly under Israel’s control have been located in the hill country, an area about two thousand feet above sea level that runs from north to south through much of central Palestine. Saul’s capital of Gibeah is located there, but this does not stop the Philistines. As chapter 13 begins, the Philistines have pushed to within five miles of the capital. Jonathan, Saul’s oldest son, attacks the Philistine outpost at Geba and thus angers the Philistines (13:3). They amass an army supported by three thousand (or three “companies” of) chariots, and the Israelites withdraw to Gilgal, by the Jordan (13:4–5). Some of Saul’s soldiers hide (13:6).

13:8–15. Saul starts with three thousand (or three “companies” of) troops (13:2), but while he delays at Gilgal, some of the men grow fearful and begin leaving Saul (13:8), who ends up with a final tally of six hundred (13:15). He is waiting for Samuel to come and offer sacrifices as he has promised to do (13:11; cf. 1 Sm 10:8). After seven days Saul violates Samuel’s command: he offers the sacrifices himself with the hope of gaining God’s blessing on the upcoming battle (13:9–10, 12). When Samuel finally arrives, he condemns Saul’s action and announces that his son will not succeed him on the throne. Instead, God will now choose “a man after his own heart” to rule Israel (13:13–14; cf. 16:7). This phrase “a man after his own heart” does not refer to the Lord’s particular favor of David or some special quality of David’s; rather, it refers to the Lord’s divine right and freedom to choose a new king. Thus it might be better understood as “a man according to his [the Lord’s] choosing.” This new choice is motivated by Saul’s guilt in ignoring the Lord’s command through his prophet.

King Saul loses his right to the throne when he ignores the word of the Lord through the prophet Samuel (1 Sm 13:8–15). In subsequent years, all of Israel’s kings will be responsible to obey the law of Moses and the instructions of the prophets (cf. Jr 25:4). If a king is guilty of wrongdoing, often a prophet will appear on the scene to announce God’s judgment.

13:16–22. In spite of mounting difficulties, Saul and Jonathan head to Geba, only a few miles from the Philistines at Michmash (13:16). The Philistines send out raiding parties to plunder and to demoralize the people, and Saul is unable to stop them (13:17–18). One reason for Israel’s predicament is a lack of weapons. According to 13:19 the Philistines have established a monopoly on the production of iron and have refused to share the secret. They may have learned how to smelt iron from the Hittites of Asia Minor, who used iron to great advantage prior to 1200 BC. The Israelites have to pay the Philistines to have their farming tools sharpened, but in time of war no plowshares are beaten into swords (13:20–21). Only Saul and Jonathan have a sword or spear (13:22); the rest of the troops must use slingshots, bows and arrows, or even ox-goads. No wonder many of Saul’s men have deserted! [Old Testament Weapons]

13:23–14:14. When all seems lost, Jonathan leads a daring attack on the Philistine position north of the Michmash pass (13:23–14:1). At the time Saul is still near Gibeah, trying to take care of national business as he sits under a pomegranate tree (14:2). No one else knows that Jonathan and his armor-bearer are embarking on a dangerous mission (14:3). Jonathan believes that God will intervene on behalf of his people and save them from “these uncircumcised men” (14:6). As Jonathan and his armor-bearer make their way across the Michmash pass, the Philistines spot them and challenge them to come up and fight (14:11–12). This response is a sign to Jonathan (14:10). The Philistines mock Saul’s troops for hiding in holes and refer to the Israelites as “Hebrews,” a term sometimes used by foreigners in a disparaging way (cf. Gn 39:17). This usage might be related to the word’s apparent etymology, from a term meaning “movers,” or it might refer to the Israelites’ origins in the hill country, as in “hillbillies.” Clearly the Philistines expect to make short work of the two men, but convinced that God is with them, Jonathan and his armor-bearer fight and kill about twenty men (14:13–14). Their faith has been vindicated.

14:15–23. As confusion grows among the Philistine forces, the Lord sends the whole army into a panic by shaking the ground (14:15). The earth tremor frightens the Philistines, and they fight among themselves in all the confusion and flee the battleground (14:16, 20). It is the same sort of panic that was behind the victory at Mizpah (1 Sm 7:7–12) and the defeat of the Midianites under Gideon (Jdg 7:22).

Saul’s lookouts at Gibeah report the commotion to their commander, and Saul immediately consults Ahijah the priest, apparently about using the ark to address the Lord (14:16–18). Before receiving an answer from the Lord, however, Saul takes his men to the battle and finds the Philistines in total confusion (14:19–20). As word about the battle spreads, the soldiers who earlier abandoned Saul rejoin his forces to take part in the chase (14:21–22), just as the ranks of Gideon swelled once the Midianites were on the run (Jdg 7:23). Since Saul has done almost nothing to bring about the defeat of the Philistines, the credit for the victory is not his. It is the Lord who has rescued Israel (14:23). The victory leaves Israel with some security in their own heartland and keeps the Philistines at a safe distance for years to come.

14:24–30. As in the case of Jephthah’s victory over the Ammonites in Jdg 11:32–35, the celebration of the Philistines’ defeat ends abruptly because of an ill-advised oath. In an apparent attempt to win the Lord’s favor, Saul has put a curse on anyone who eats any food before the coming evening (14:24–26). The curse demonstrates Saul’s poor judgment, because the weary troops need to be refreshed so they can continue the pursuit of the Philistines. To make matters worse, Jonathan did not hear the curse and eats some honey along the way. He immediately receives some much-needed strength but is upset when someone tells him about his father’s oath (14:27–30).

14:31–35. As a direct result of Saul’s curse the rest of the troops transgress a purity restriction known also from the law of Moses. They are famished after chasing the Philistines into the western foothills, so when they are finally allowed to eat, they butcher animals without properly draining the blood (14:31–33). By eating blood they break the Lord’s command (see Lv 17:11; Dt 12:16), because blood was normally to be poured out in sacrifices and was considered sacred. Saul builds his first altar at this time, perhaps to atone for the actions of his men and to express thanks to God for the great victory over the Philistines (14:34–35).

14:36–46. After the soldiers eat and regain some strength, Saul proposes they continue to pursue the Philistines during the night to follow up the victory. The men agree, but when Ahijah inquires of the Lord—presumably through the Urim and Thummim—there is no answer (14:36–37). Saul reasons that someone must have broken his oath and prays that the Lord might identify the guilty party (14:38–40). Using the same Urim and Thummim to cast lots, Saul and the priest discover that Jonathan is the culprit (14:41–42). Even though Jonathan has only “tasted a little honey,” Saul asserts that he must die (14:43–44). The troops protest Saul’s decision, for they know that Jonathan is the one whom God has used to bring about an amazing victory. Why should he be put to death for being courageous? Whatever their arguments were, which are not specified, the people convince Saul to let Jonathan live, a happy outcome (14:45). Even so, the entire event signals that Saul’s judgment and leadership ability are already in decline and suffering from the reversal of God’s blessing (13:10–14). Moreover, the complications caused by Saul’s curse prevent the Israelites from taking full advantage of the disarray of the Philistines (14:46). Many of the Philistines make it safely back to their coastal cities and resume their attacks, eventually bringing about the death of Saul and the collapse of Israel (31:1–13).

14:47–52. As the first main section of 1–2 Samuel (1 Sm 1:1–15:35) nears the end, Saul’s rule as king is summarized. Even though Saul continues to rule for a bit longer (until the end of 1 Samuel), chapter 15 marks the transition to David’s rise to the throne.

Along with his victories over the Ammonites and Philistines, Saul enjoys some success against Moab and Edom to the east and south and against the king of Zobah, a region north of Israel (14:47). None of these other battles are recorded in Scripture, but chapter 15 does describe the victory over the Amalekites.

Saul’s sons are listed in 14:49, although Ish-bosheth, who succeeds him as king briefly, is not named (see 2 Sm 2:8). Saul’s two daughters, Merab and Michal, are also mentioned. Michal will play an important role as David’s first wife. The key military figure is Saul’s cousin Abner, who commands the army throughout his reign (14:50).

15:1–9. As in the last chapter, Saul wins an important victory but makes a serious mistake. This time the enemy is the Amalekites, a bedouin people who attacked the Israelites after they came out of Egypt (15:2; cf. Ex 17:8–16). In accord with the Lord’s harsh words about Amalek given to Moses, Samuel tells Saul to attack the Amalekites and “completely destroy” all their people and animals (15:3). This technical term for complete destruction (herem) was also applied to the Canaanites when Joshua invaded the land. Because of the wickedness of the people, God decreed that everybody and everything should be wiped out (Jos 6:17–18). No plunder of any kind could be taken. [Wilderness of Shur]

Saul musters a sizable army and heads south to carry out his mission (15:4–5). Before attacking, he warns the Kenites, a seminomadic community, to move out of the area (15:6). Unlike the Amalekites, the Kenites have been friendly to Israel, and Moses in fact married a Kenite woman. Once the Kenites leave, Saul battles the Amalekites, chasing them to the eastern border of Egypt and wiping out all the people (15:7–8). But he unwisely spares the king, Agag, and “the best of the sheep, goats, cattle, and choice animals” (15:9).

15:10–21. Saul’s incomplete obedience creates an immediate crisis for the incipient monarchy because the Lord is grieved that he has made Saul king (15:10–11). Samuel knows that Saul’s future is bleak. Saul’s sin and the sin of his soldiers brings deep sorrow to God, and judgment is sure to follow. As he returns from the victory, Saul sets up a monument in his own honor, revealing an attitude of pride (15:12). Then he goes to Gilgal, where he was confirmed as king years earlier (11:14–15) but where he will now lose the kingship.

When Samuel meets him, Saul greets him warmly, but Samuel quickly dispenses with the niceties and instead responds by asking why the sheep and cattle have been spared (15:13–14). Saul tries to shift the blame to the soldiers, claiming that the animals were saved so that they might be sacrificed to the Lord (15:15). Even if the army had a spiritual purpose in mind, Samuel asserts that it was wrong to spare the animals (15:16–19). Saul protests vigorously, arguing that he did carry out the assigned mission (15:20–21).

15:22–31. Samuel’s response to Saul gives the classic position about the relationship between sacrifice and obedience. Stated bluntly, “to obey is better than sacrifice” (15:22). Without question, the offering of sacrifices was an integral part of worship in ancient Israel and was valued highly, but it was an empty ritual without the proper motivation and piety. A rebellious and arrogant attitude nullified the effect of any sacrifice. Genuine repentance and obedience are necessary accompaniments to the presentation of sacrifices. Since Saul has deliberately disobeyed the Lord’s command, the Lord rejects him as king (15:23).

Alarmed by the severity of Samuel’s pronouncement, Saul finally admits his sin and begs forgiveness, but Samuel condemns him again and turns to leave. As he does so, Saul, who has taken hold of Samuel’s robe, accidentally tears it (15:24–27). The action proves symbolic of the fact that the Lord has “torn the kingship of Israel” from Saul and given it to David (15:28). Lest there be any doubt about the certainty of God’s word, Samuel reminds Saul that God “does not lie or change his mind” (15:29). Ironically, verse 29 is an allusion to Balaam’s words to the king of Moab warning him that God had fully determined to bless Israel (Nm 23:11–12). For Saul, God’s word has become a curse.

When Saul disobeys God by sacrificing, Samuel tells him, “to obey is better than sacrifice” (1 Sm 15:22). Many of the prophets will wrestle with this issue and assert that a large number of sacrifices will never atone for injustice, oppression, or pride (e.g., Is 1:11–17; Jr 7:1–26; Hs 6:6; Am 5:21–24; Mc 6:6–8; cf. Ps 40:6; Mt 9:13; 12:7; Heb 10).

Although at first (15:26) Samuel refuses to accompany Saul to the place of worship, he finally agrees to go with him (15:31). If he had not gone, the break between the prophet and the king would publicly weaken Saul’s authority and thus that of the monarchy in general. The “honor” of 15:30 is probably the honor of Samuel’s presence at Gilgal, where the sacrifices were offered.

15:32–35. Another reason why Samuel goes to Gilgal is to deal with Agag, king of the Amalekites, whom Saul has spared. Normally victory was not complete until the opposing king was killed, especially if it was a war of “complete destruction” (cf. 15:3). Like Joshua, who executed the five Amorite kings (Jos 10:26), and Gideon, who killed the two kings of Midian (Jdg 8:21), Samuel strikes down Agag (15:32–33). It may seem like a strange role for the aged prophet and priest, but Samuel here is functioning as the “judge” in his military duties. That Samuel has to play the judge, even after the establishment of a monarchy, is yet another sign that Saul is failing.

2. DAVID’S RISE TO THE THRONE (1 Sm 16:1–2 Sm 8:18)

As noted in the introduction, these chapters serve as a defense of the dynasty of David, providing a full account of David’s rise to the throne and explaining why someone from the tribe of Judah replaces Saul of Benjamin. One of the key points in this “apology” is that Saul has disqualified himself as king by his actions, paving the way for David’s accession.

A. David’s fame (16:1–17:58). The OT contains many stories about the young and the obscure and how they become successful, but perhaps none is loved more than the story of David. Born the youngest of eight sons in the town of Bethlehem, David becomes a hero overnight and achieves a level of fame and fortune unmatched in Israelite tradition. As musician, poet, prophet, warrior, diplomat, and statesman, in his versatility and ability David sets the standard for all the monarchs who follow him, from his son and successor Solomon to the kings of the north and south after the monarchy splits. Before David is allowed to develop some of these gifts, however, he first has to survive Saul’s anger and jealousy.

16:1–13. After the series of disasters that marks Saul’s first years (military victories marred by Saul’s lack of faith and judgment), the Lord sends Samuel to Bethlehem, a town six miles south of Jerusalem, to anoint a new king (16:1). This was the setting for the story of Ruth and Boaz, and it is one of their great-grandsons that Samuel anoints (Ru 4:17). Samuel is afraid Saul might kill him, but the Lord shows Samuel how to disguise the purpose of the visit by offering a sacrifice in Bethlehem (16:2–3). When he arrives there, the elders’ reaction—they meet Samuel with some trepidation—perhaps reflects that they either share his concern about a potential negative reaction from Saul or are worried that Samuel has come to reprove them (16:4). Whatever their worries, Samuel calms their fears. He has come only to offer a sacrifice. He then invites Jesse and his sons to come to the sacrifice with him (16:5).

When they arrive Samuel is impressed by the oldest son, Eliab, a tall and handsome man. But the Lord reminds Samuel that he considers the inner qualities of an individual rather than the outward appearance (16:6–7). None of Jesse’s seven sons present at the sacrifice is the chosen one, so Samuel insists that the youngest son be brought from tending the sheep (16:8–11). When David arrives, he too is handsome and fit, but as the youngest he is the unlikeliest choice; even so, the Lord chooses him to shepherd the people of Israel (cf. 2 Sm 5:2). On the spot and with his family looking on, Samuel anoints David with oil as the new king-designate (16:12–13). “The Spirit of the Lord came powerfully on David from that day forward,” as it has come on Saul at the earlier anointing (16:13; cf. 10:6–10). Throughout the rest of his life, David will enjoy the empowering of the Spirit on his work and ministry.

16:14–23. While David is receiving the Spirit of the Lord, it departs from Saul (16:14a). In fact, the language and juxtaposition of these statements in verses 13–14 suggest that the historian saw these events as simultaneous and related. Not only, though, does Saul lose the divine Spirit; the Lord also sends an evil spirit to torment him (16:14b). (We must remember that the Hebrews’ perspective on good and evil was that God created and controlled them both; see Is 45:7.) Saul’s jealousy and depression are made worse because of the influence of this evil spirit, and at times it will drive Saul to violence (cf. 1 Sm 18:10–11). According to 16:23, the evil spirit affects Saul sporadically.

In an attempt to help Saul find relief from the evil spirit, Saul’s attendants suggest that he secure a musician to play soothing music (16:15–16). Ironically, the man they recommend is none other than David. In addition to his ability as a shepherd, David knows how to play the harp, and he has a fine personality. He also enjoys divine favor (16:18). By bringing David to his court, Saul gives his successor valuable training, during which David might make important personal and political connections. Saul likes David very much and asks Jesse if David might remain in his service (16:21–22). While the court service introduces David to the inner workings of the monarchy, what catapults David into the public eye is his heroic victory over Goliath, an event that also betokens his later successes and eventual domination of the Philistines.

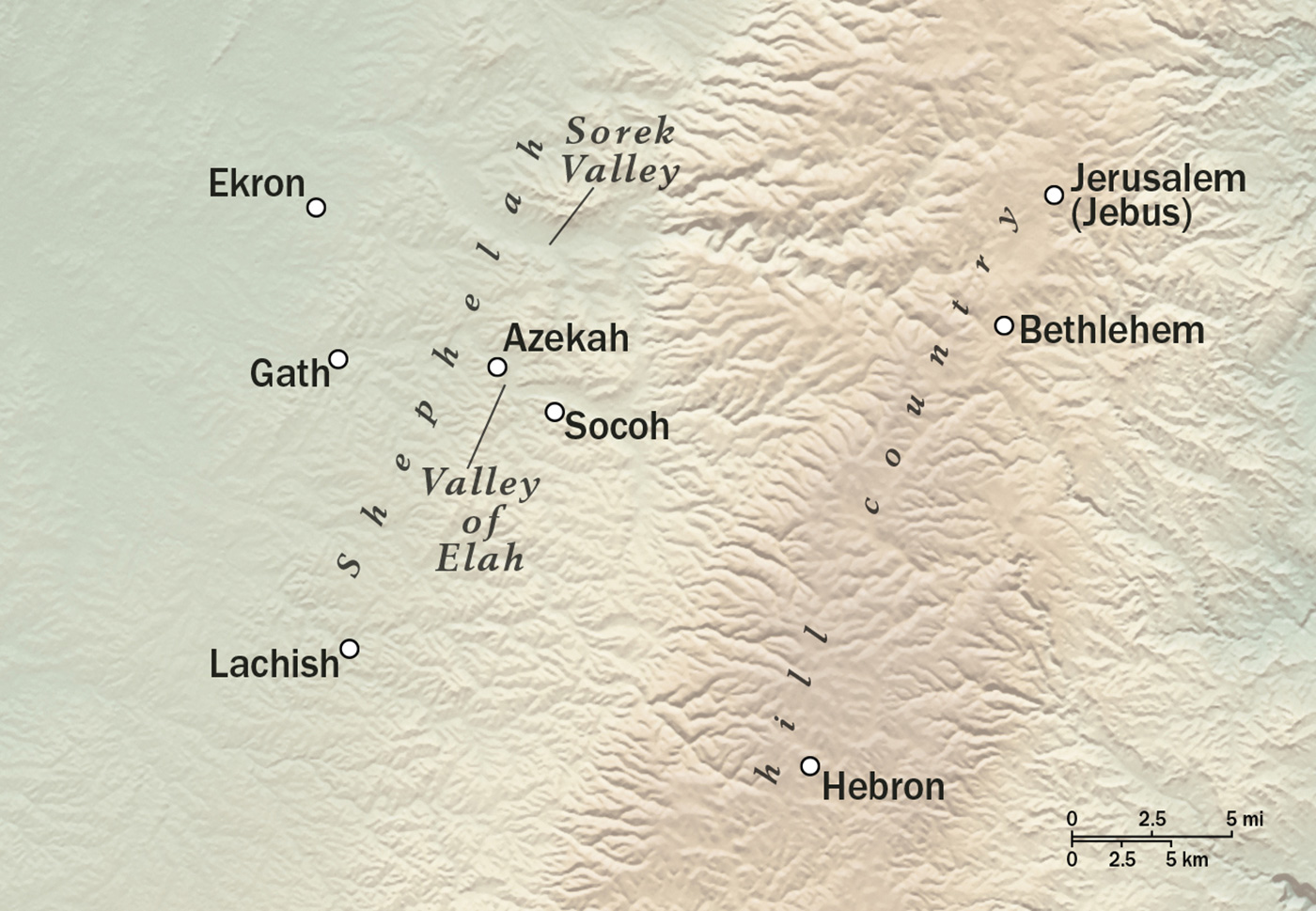

17:1–11. The setting of young David’s famous first military victory is the Valley of Elah, about fifteen miles west of Bethlehem (17:1–2). The Philistines have amassed their troops there in an apparent attempt to reassert control over the emerging Israelite monarchy. Instead of trying to engage the Israelites in full battle, the Philistines send out a champion fighter named Goliath to challenge the Israelites to send out a soldier of theirs for one-on-one combat (17:3–4a, 8–10). In view of Goliath’s great size and strength, it is easy to see why the Philistines are counting on him (17:4b–5). He is about nine feet, nine inches tall—this is significantly taller than the height of the average Iron Age male, which was just over five feet (see the article “How Tall Is Goliath?”). Also, his armor weighs about 125 pounds, which is more than even most modern soldiers carry in the field. [How Tall Is Goliath?]

The outcome of the battle will hinge on the struggle between the two men. This custom was known also among the Greeks and the Hittites of Asia Minor. According to 2 Sm 2:15, a later war between Israel and Judah will be settled by a twelve-man “team” representing each side. When Goliath hurls his challenge toward the Israelites, Saul and his men cower in fear (17:11). Their defeatist attitude is reminiscent of the fear of the ten spies who saw the “men of great size” in Hebron prior to the conquest (Nm 13:31–33).

17:12–24. As tension mounts at the battle scene, we are told that David’s three oldest brothers are among Saul’s troops, who have been listening to Goliath’s defiant challenge for forty days (17:12–16). David is back in Bethlehem taking care of the sheep, for Saul’s condition has apparently improved. Anxious about his older sons, Jesse decides to send David to visit the troops and take some food to his brothers and their commander (17:17–19). It is not hard to imagine that young David would welcome the chance to see the excitement of impending conflict and to find out why no battle has taken place yet. When he arrives at the scene, he soon discovers the problem and witnesses Goliath stepping forward to shout his defiance against Israel. David also sees the Israelites again shrink back in fear (17:20–24).

17:25–40. Although no one has yet volunteered to fight Goliath, Saul offers substantial rewards to the man who can defeat him. Wealth and honor will be his, along with exemption from taxes for his father’s family. The victor will also receive Saul’s daughter in marriage, with no further bride-price expected (17:25). Normally a sizable amount of silver or valuables had to be paid by the groom to the family of the bride, though military exploits were sometimes substituted. Saul’s offer is attractive, but who can stand a chance against the Philistine champion?

David is the first one to express any interest, taking youthful umbrage at Goliath’s defiance of “the armies of the living God” (17:26). As David tries to encourage the troops, he is severely reprimanded by his oldest brother, Eliab (17:28). Eliab may be jealous of David’s anointing, or he may feel guilty for not volunteering to fight Goliath himself, but in any event his assessment of his brother is misguided. David is not trying to avoid family chores, nor is his heart conceited and wicked. With a combination of faith and naïveté that belongs predominantly to young men, David simply questions the Israelites’ fear and before long informs King Saul that he will fight the “uncircumcised Philistine” (17:26, 36). In view of David’s age and inexperience, however, Saul at first rejects his offer (17:31–33). But David reminds Saul that as a shepherd he has killed a lion and a bear, both of which are far more agile than Goliath. David is confident that since God has saved him from wild animals, he will also save him from Goliath (17:34–37a).

Convinced of David’s faith and courage, Saul gives him his blessing and offers David his own armor. But the armor does not fit David, nor will the bulky equipment be helpful since it would inhibit his movement (17:37b–39). Instead, he takes his shepherd’s staff, his sling, and five smooth stones from the stream and goes to face Goliath (17:40).

17:41–54. After waiting for forty days, Goliath is disappointed and disgusted when he sees the youthful, unarmed David coming toward him (17:41–44). How much glory is there in killing a defenseless youth? David listens to Goliath’s curses and then acknowledges that his main weapon is “the name of the Lord of Armies” (17:45). Like Saul’s son Jonathan (see 14:6), David believes that the battle is the Lord’s and that victory does not depend on who has the best weapons or the most soldiers (17:46–47).

As Goliath moves in to silence his brash opponent, David slings one of the stones with unerring accuracy. It strikes the Philistine on the forehead, perhaps killing him instantly or at least incapacitating him (17:48–50). David then removes Goliath’s sword from the scabbard and cuts off his head. Stunned by this turn of events, the Philistines flee back toward the coast, to their cities of Gath and Ekron, with the Israelites in hot pursuit (17:51–52). As David predicted (17:46), many of the Philistines are killed along the way. David puts Goliath’s weapons in his own tent (17:54b) and later dedicates the sword to the Lord, taking it to the tabernacle (21:9) as a way of acknowledging that God gave him the victory. According to 17:54a, David takes Goliath’s head to Jerusalem. This may refer to a later time after David has conquered Jerusalem (2 Sm 5:1–9), or David may display Goliath’s head in the Jebusite city as a warning that Jerusalem will suffer a similar fate in the future.

As with all the great acts of Israel’s Warrior God, such as the parting of the Red Sea (Ex 13:17–15:21) or the fall of Jericho’s walls (Jos 5:13–6:27), so the death of Goliath demonstrates the power of Israel’s God, “for the battle is the Lord’s” (1 Sm 17:47).

David uses a sling and stones to defeat Goliath.

17:55–58. Saul’s questions about David’s identity seem peculiar in light of David’s earlier service as a court musician (16:18–23), not to mention the discussion between the two before David fought Goliath. Since David did not stay at the court permanently, however, it is possible that Saul has forgotten his name or at least the name of his father. Alternately, many scholars take this literary bump, as well as many others like it in this episode, as an indication that at least two popular traditions about young David were edited together by the historian.

B. David’s struggles with Saul (18:1–27:12). In spite of, or perhaps because of, the beneficial results that David’s triumph brings to Israel as a whole, Saul soon becomes jealous of David and begins to treat him as a rival to the throne. Perhaps Saul suspects that David is the “neighbor” who will replace him as king (15:28).

After a brief period of promotions and honor, David becomes persona non grata in Saul’s court, and the king tries several methods to get rid of him. Saul’s attitude is diametrically opposed to that of his son Jonathan, who does all he can to help David.

18:1–7. Jonathan admires David greatly and comes to be his close friend (18:1). Both men are courageous warriors who depend on the Lord for victory, and both are national heroes. Out of his love for David, Jonathan makes a covenant with David and gives him clothes and weapons as a pledge of his friendship (18:3–4). Jonathan’s sword, in particular, must be highly treasured by David. In spite of Saul’s increasing ill will toward David, he continues to give David additional military assignments and a high rank in the army due to David’s ability and successes (18:5).

When Saul and David return home after another defeat of the Philistines, the women of the land come out to greet them with singing and dancing (18:6), much like when Miriam and the women of Israel celebrated the victory over the Egyptians at the Red Sea (Ex 15:20). Since David has killed Goliath, his name is included along with Saul’s as the women sing their praises (18:7). The refrain must have been sung throughout the country, because even the Philistines know about it (1 Sm 21:11).

18:8–16. When Saul hears the refrain, he is infuriated, and his jealousy and suspicion of David increase (18:8–9). Coupled with the influences of another “evil spirit sent from God,” this jealousy drives Saul to hurl his spear at David while the young warrior is temporarily back at his musician’s post (18:10–11a). Saul misses twice, and then, frustrated, sends David back to the battlefield. He recognizes that the Lord is with David but somehow hopes that the Philistines will kill him in battle (18:11b–14). When David wins additional battles, the people love him all the more and Saul’s apprehensions increase (18:15–16).

18:17–30. When David killed Goliath, he won the right to marry Saul’s daughter, Merab. Saul, however, adds further military responsibility as a condition of marriage (18:17). As the oldest daughter, Merab would have given her husband an important claim in the matter of succession to the throne. David politely refuses her hand, a decision for which we are not given any reason (18:18–19). In any event, when Saul’s other daughter, Michal, is offered to David, he agrees to the marriage in spite of the required bride-price. Saul hopes that one of the Philistines will kill David, but instead, David and his men double the bride-price by killing two hundred Philistines (18:20–27). Saul is forced to make good on his offer, and Michal becomes David’s wife. Twice the text states that Michal is in love with David (18:20, 28), so the marriage begins on a positive note in spite of the disgruntled father-in-law. Both Saul’s position and his state of mind are becoming more and more precarious, while David’s standing steadily improves (18:29–30).

19:1–7. Unable to bring about David’s death at the hand of the Philistines, Saul appeals to his close associates to kill David. But Jonathan warns David and tells him to go into hiding (19:1–3). Jonathan then tries to persuade his father that David is a friend, not an enemy. After all, he argues, David risked his life to save Saul and Israel from the Philistine threat (19:4–5). Jonathan’s appeal convinces Saul, and he promises not to harm David. David is restored to Saul’s service in the court (19:6–7).

19:8–17. The reconciliation does not last long, however, and it may be David’s continued success as a general that triggers a new outburst of jealousy and violence (19:8). For the third time, an evil spirit afflicts Saul, and as in 18:10, David’s music does not soothe the king. Again Saul throws his spear at David, and again he misses (19:9–10). It is the last time David will dare to be in the presence of the increasingly unstable king.

David returns to his own home, but Michal convinces him to flee that night. Like Rahab with the two spies, Michal lowers David through a window so he can escape undetected (19:11–12). She then buys time for David by putting an idol in his bed and telling Saul’s messengers that David is sick (19:13–14). When Saul learns that Michal helped David escape, he is upset with her. She explains that David threatened her life unless she assisted him (19:15–17). Michal’s actions underscore her allegiance to her husband over her father.

19:18–24. Saul is thwarted in his attempt to capture David. David, deciding to take refuge with Samuel in Ramah, only a short distance from Saul’s capital at Gibeah, pours out his troubles to Samuel, who takes him to the nearby residence of the prophets (19:18). When Saul’s men come to capture David, the Spirit of God comes on them and compels them to prophesy (19:19–20). After two more groups of messengers have the same experience, Saul himself comes in search of Samuel and David. As Saul is on the way to Naioth, the Spirit of the Lord also falls on him, causing Saul to prophesy and strip off his clothes, a sign of an ecstatic state (19:21–24).

Literarily this is an important juncture, since the prophetic frenzy that overtakes Saul here at his last meeting with Samuel mirrors what happened after Samuel first anointed him (10:11–12). Thus, Saul’s anointment began with Samuel and was marked with the sign of prophecy, and it ends with Samuel and is again marked by prophecy as well as the symbolic removal of his garments, representing his removal as the anointed king.

20:1–10. Although Jonathan is Saul’s oldest son and is expected to succeed him on the throne, he has become close friends with Saul’s chief rival. Jonathan sees that David is God’s chosen and does not allow his own ambition to oppose God’s will.

Within a short period of time David’s status has changed from national hero to fugitive. Disappointed and confused, David seeks out Jonathan for an explanation of Saul’s erratic behavior (20:1). Jonathan assures David that Saul would not harm him. But he does agree to sound out his father regarding his current feelings about David (20:2–4). The next day is the New Moon festival, a holiday on the first of the month, marked by rest and special offerings. Verse 27 indicates that it is a two-day festival. Since David is Saul’s son-in-law and has held a high position in the army, Saul evidently expects David to be present at his table (20:5). David uses the situation as a test of Saul’s intentions. He asks Jonathan to give Saul a false excuse for his absence and to note Saul’s response: if Saul accepts the excuse, David is safe, but if Saul is angered, his desire to kill David remains (20:6–10).

20:11–23. Sensing that Saul’s jealousy might make future contact with David impossible, Jonathan takes David outside for a long talk. He promises to carry out David’s wishes at the festival and to let David know if he should stay or flee (20:11–15). But beyond that, Jonathan wants to reaffirm his covenant with David (20:16–17). Jonathan fully expects David to be the next king (20:13), and he wants David to promise that he will be kind to Jonathan’s family even after he takes the throne. Often a king from a new dynasty would put to death the descendants of the previous king. David reaffirms his oath to show “kindness” to Jonathan and his family (20:14–15). When he becomes king, David will remember his oath to Jonathan and make special provision for his crippled son, Mephibosheth (2 Sm 9:7).

20:24–42. All hope that Saul might be reconciled to David is dashed by what takes place at the New Moon festival. Saul assumes on the first day that David has a legitimate reason to be absent, but on the second day he explodes (20:24–26). When Jonathan tells Saul about the sacrifices in Bethlehem, Saul realizes that he will not have another chance to kill David, so he takes out his anger on Jonathan. Saul cannot understand how Jonathan could side with David when David is the one standing between him and the throne. In utter frustration, Saul hurls his spear across the table at Jonathan (20:27–34). He has clearly never been able to accept Samuel’s announcement that his kingdom will not endure, and in his obsession to kill David, Saul manages to alienate his own son as well.

The next day Jonathan goes to the field where David is hiding to give him the prearranged signal (cf. 20:18–23). Jonathan shoots an arrow beyond the boy who is with him as a sign that David must flee (20:35–40). Because Jonathan knows he might be watched, they have not planned to meet and talk, but after the boy returns to town, David ignores the danger. The two have a tearful parting, and Jonathan reminds David of their sworn friendship and of the Lord’s involvement in their families forever (20:41–42). Judging from his praise of the fallen Jonathan in 2 Sm 1:26, David greatly values their friendship.

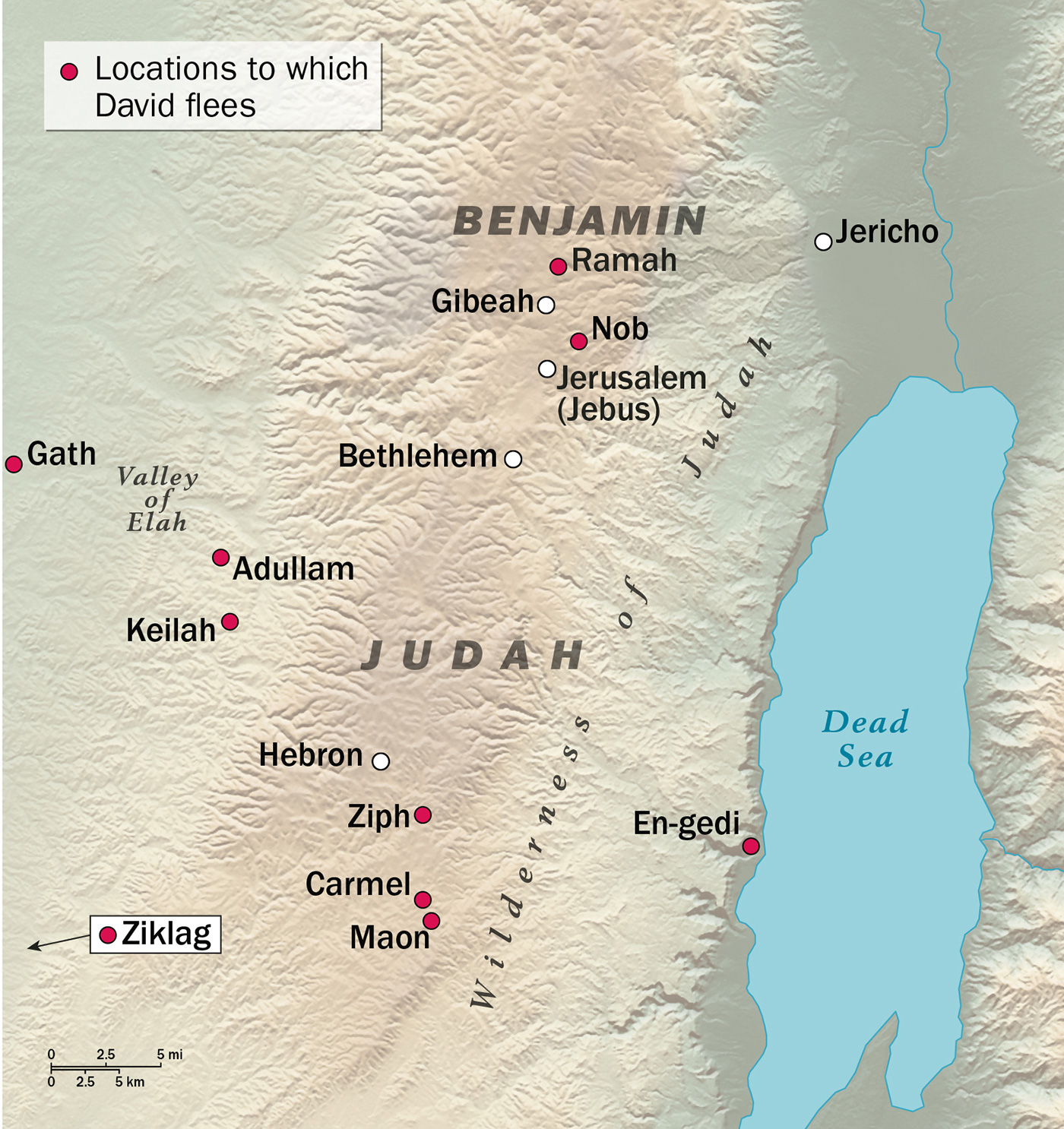

21:1–9. The next several years David spends as a fugitive, moving from place to place trying to avoid Saul. Most of the time he stays within the borders of his own tribe of Judah, although on two occasions he lives under Philistine jurisdiction.

David stops first at Nob, where the tabernacle is located, a town just northeast of Jerusalem. When he arrives alone, the high priest Ahimelech is startled and wonders what is wrong (21:1). David deceitfully replies that Saul has sent him on a secret mission, and then he asks for some food (21:2–3). The only food available is the Bread of the Presence, the loaves kept in the holy place as a symbol of God’s provision. Normally this bread was eaten only by the priests (Lv 24:9), but Ahimelech agrees to give it to David provided that he and his men are ceremonially clean (21:4–6). This involves, in particular, abstinence from sexual relations (Ex 19:15).

In his conflict with the Pharisees over picking grain on the Sabbath, Jesus refers to the incident of David eating the Bread of the Presence (1 Sm 21:1–6) as an example of doing what is right inx an emergency, even though it was, strictly speaking, “not lawful” (Mk 2:25–26).

After receiving the bread, David also takes with him the sword of Goliath that he dedicated to the Lord after his great victory (21:9). According to 22:10 and 15 Ahimelech inquires of the Lord to give David some much-needed guidance.

All this time Ahimelech is unaware of David’s flight from Saul, since David has lied about the purpose of his visit. This deception may have helped David obtain what he needed, but it costs the priests dearly when Saul finds out what they have done for David (22:17–18).

21:10–15. Finding a safe hiding place in a small country is not easy, so David seeks out an area where Saul will be unlikely to follow him. It is nevertheless surprising that David goes immediately to Philistine territory and to Gath, the hometown of Goliath (21:10)! He must have hoped that no one would recognize him, but he is immediately identified as “the king of the land” and a warrior like Saul (21:11). (It is unlikely that the Philistines would have been privy to David’s anointed status, and so in the phrase “the king of the land” we almost certainly see the historian’s hand, reminding the audience through even the mouth of Israel’s enemies that David is the true king.)

David’s response is to pretend to be insane, with the hope that they will not detain him. On seeing his behavior, Achish, the king of Gath, refuses to let him stay in the city (21:12–15). Although David will later return to Gath (27:1–2), for the time being it is too dangerous.

22:1–5. After his narrow escape David travels about twelve miles farther inland, to the cave of Adullam, in the western foothills (22:1a). This is close to the place where he killed Goliath, in the Valley of Elah. Word of his whereabouts reaches his family and other individuals who are in trouble with Saul’s regime. About four hundred malcontents join him and are molded by David into an effective and loyal fighting force (22:1b–2). Managing this motley crew would have been both extremely difficult and excellent preparation for ruling the entire land. Since Saul will have likely taken measures against the rest of David’s family, David asks the king of Moab to allow his parents to live there for a while (22:3–4).

At this time we are introduced to the prophet Gad, who advises David and who is associated with a record of David’s reign (22:5; cf. 1 Ch 29:29). It is Gad who gives David a choice of three options after David sins by taking a census of the land (2 Sm 24:11–14).

22:6–10. Aware that David now has a growing group of supporters, Saul is worried about a conspiracy against his life (22:6–8). He knows that Jonathan is a close friend of David’s, and he is afraid that other high officials might have been tempted to defect to David’s side. If any are so inclined, Saul warns them that David is from the tribe of Judah and most of them are from Benjamin: Will David give them high positions and valuable property if he becomes king?

To prove his loyalty to Saul, Doeg the Edomite, Saul’s head shepherd, reports what he has seen when David received help from Ahimelech the priest (22:9–10). The implication is that Ahimelech might be the next leader to join David. [Tamarisk]

22:11–15. Armed with this new information, Saul immediately sends for Ahimelech and the rest of the priests. He accuses Ahimelech of conspiring against him by giving valuable assistance to a traitor (22:11–13). Ahimelech protests that he had not realized that David was regarded as an outlaw and a fugitive. Moreover, Ahimelech complains, he perceived no reason to suspect David: David is the king’s own son-in-law and a respected military leader who has accomplished much for the whole nation. Besides, David told Ahimelech that he was on a secret mission for Saul (22:14–15; see 1 Sm 21:2).

22:16–23. Ahimelech’s reasoning is sound, but Saul has moved beyond reason. When Saul orders the guards to kill the priests, they are unwilling; but Doeg the Edomite is willing and executes the priests (22:16–18a). Doeg’s actions do not help relations between Edom and Israel, and David later treats the Edomites harshly (cf. 2 Sm 8:12–14).

Not only does Saul order the death of eighty-five priests, but the whole town of Nob is put to the sword, including women and children (22:18b–19). It is the sort of total destruction normally reserved for Israel’s worst enemies. Only one person escapes and reaches David with the news: a son of Ahimelech named Abiathar. When David hears about the massacre, he admits that his deception has contributed heavily to the priests’ deaths (22:20–23). Abiathar remains with David and uses the ephod with the Urim and Thummim to inquire of the Lord for David (23:6, 9). Meanwhile, Saul is left without any guidance from prophet or priest.

The general movement of David’s flight is toward the south and east and the more rugged areas of Judah. But with the help of local residents, Saul is able to track him closely.

23:1–6. Throughout his time as a fugitive David protects the cities of Judah from their enemies. When the Philistines steal grain from the threshing floors of Keilah, a city in the western foothills about ten miles northwest of Hebron, David and his men attack them and drive them off (23:1–6). Even though David is no longer in Saul’s employ, he continues to enjoy mastery over the Philistines. The victory nets David considerable plunder, especially livestock (23:5).