Jeremiah

1. JEREMIAH’S CREDENTIALS (1:1–19)

1:1–3. The stage is set for the book of Jeremiah by introducing person, place, event, and historical time. The person is Jeremiah (1:1), whose name probably means “The Lord Is Exalted.” He is from a priestly line. It is unclear whether Jeremiah came from the family of Abiathar, a priest exiled by David to Anathoth (1 Kg 2:26–27). The place is Anathoth, the modern Anata, two to three miles northeast of Jerusalem.

The event is the coming of the word of God (1:2a), which means that the subsequent book has a divine quality to it. The time frame extends from Josiah through Jehoiakim to Zedekiah, Judah’s last king (1:2b–3). This list omits two three-month reigns: Jehoahaz (609 BC) and Jehoiachin (598–597). Jeremiah’s life coincides with the final years of Judah and its collapse. The prophet lives through Josiah’s reform, Nebuchadnezzar’s siege of Jerusalem in 597, the reign of the vacillating Zedekiah, and the capture and burning of Jerusalem in 587, as well as the horror of Gedaliah’s assassination.

While appropriate for the entire book, the introduction is, to be formal, limited to chapters 1–39, since Jeremiah’s ministry did not conclude with Zedekiah (cf. chaps. 40–44). Almost certainly, therefore, the book grew in stages.

1:4–10. The date for the prophet’s call is 627 BC, the thirteenth year of Josiah’s rule (1:2), when Jeremiah is in his middle or late teens. The dialogue points to an intimacy between the Lord and Jeremiah.

God’s “forming” activity (1:5) recalls Gn 2:7. The word for “prophet” is most appropriately defined, according to the Hebrew root, as “one who is called.” Prophetic work was exemplified by Moses (Dt 18:18), as depicted in Ex 7:1.

Jeremiah registers an excuse (1:6). The word translated “youth” suggests inexperience and inadequacy as well as age. God identifies the given reason (inability to speak) as well as the unspoken but deeper reason (fear) (1:7–8a). The fear is met with the so-called divine-assistance formula, “I will be with you” (1:8b; cf. 1:19; also Gn 28:15; Mt 28:20).

The installation ceremony involves God’s personal touch (1:9). Jeremiah’s primary vocation is speaking, though he will engage in sign acts (chaps. 13, 19, 32). The gift of words recalls Moses (Dt 18:18).

Jeremiah’s ministry is to extend beyond Judah/Israel to other nations (1:10). He is called to demolish false securities (Jr 7:1–15) and to root out the cancer of idolatry and social corruption. Deconstruction precedes construction. Much of Jeremiah’s message is about threat and punishment; good news, as in the Book of Comfort (chaps. 30–33), is less characteristic. His six-part job assignment is to uproot and tear down, to destroy and overthrow, to build and to plant (18:7–9; 24:6; 31:28; 42:10; 45:4).

1:11–16. Two objects—a flowering branch and a boiling pot—are used to further clarify the call. There is a wordplay between “almond” (Hb shaqed) and “watch” (Hb shaqad) (1:11–12; see the CSB footnote for 1:12). Almond trees are among the first to flower in spring and so become “watching trees.” The word over which God is watching is the promise to Jeremiah.

The boiling pot (1:13–16) represents an unnamed northern army (later to be identified as Babylon; cf. chap. 39). The reason for disaster, variously nuanced throughout, is basically that the people have forsaken God. This summary accusation and the announcement of disaster foreshadow two themes that will dominate chapters 2–10.

1:17–19. Jeremiah’s commission is restated. “Get ready” (1:17) points to promptness in obeying an order (cf. 1 Kg 18:46). Jeremiah will face strenuous opposition from religious officialdom. He will be opposed by kings, by princes, by priests, and by the people (1:18b). But God will make him as strong as a fortified city (1:18a). To call Jeremiah a weeping prophet is not incorrect, but the projected portrait is of a man of steel. His unbending personal courage is most impressive (1:19).

2. SERMONS WARNING OF DISASTER (2:1–10:25)

A. A marriage about to break up (2:1–3:5). The prophet’s opening sermon, dated prior to Josiah’s reform in 621, is direct, even abrupt. The “house of Jacob” (2:4) technically refers to all descendants of Jacob, which includes the ten tribes exiled by the Assyrians in 722 BC as well as the people in the southern territories of Judah and Benjamin, who have, at the time of speaking (627–622), been spared an invasion.

The first scene (2:1–3) shows God with his people, who are like a new bride on a honeymoon. But almost at once there is trouble. The last scene (3:1–5) puts divorce talk squarely at the center. It is a case of a ruined marriage. But God does not want a divorce. Through these verses rings the pathos of a hurt marriage partner. Here is sweet talk about a honeymoon, nostalgic talk about good times, angry talk about people turning to Baal, and exasperated talk about guilty people who claim innocence. Evidence of the partner’s neglect, her arrogance, self-sufficiency, idolatry, injustice, and physical/spiritual adultery is cited. There is no outright call to repent—yet. Pleas for a people to reconsider are frequent.

Jeremiah frequently uses a marriage analogy to speak of God’s relationship to his people. This analogy, also prominent in Ezekiel and Hosea, will continue into the NT, where the church will be called the wife or the bride of Christ.

2:1–3. The initial honeymoon has been called the “seed oracle” for chapters 2–3, where the themes are expanded. The partners share courtship memories of good days: the exodus and Sinai. To that covenant, the people, like a bride wanting to please, responded, “We will do and obey all that the LORD has commanded” (Ex 24:7). “Loyalty” (Hb hesed, 2:2) is a strong word indicating covenant love. As the firstfruits are choice fruit, so Israel was special to God (2:3). As a protective bridegroom, God would not allow the slightest injury to be inflicted on his bride. God and Israel were intimate and close.

2:4–8. Then there was trouble. Neither the leaders nor the people asked the Lord for orientation (2:6). Ironically, the priests, whose major duty was to teach the law—a law that called for the worship of the Lord—did not bother about the Lord (2:8). The prophets, who were to rebuke transgressions, instead now themselves prophesied by Baal. Each group of leaders mishandled its responsibility.

Baal was the god of the Canaanites, a god of weather and fertility. But God’s favors, not Baal’s, made crops productive (2:7). God as partner spelled benefits. To walk after Baal was of no profit. “Worthless” is Jeremiah’s customary word for idols (2:5; cf. 8:19; 10:8, 15; 16:19). Disregard for God, departure from God, and courtships with another god spell deep trouble for the covenant.

2:9–13. In 2:9, a court lawsuit gets under way. It is the Lord, Yahweh, versus Israel. God the prosecutor claims that Israel’s behavior is unprecedented. Were one to go west to the island of Cyprus in the Mediterranean or east to the Kedar tribes in Arabia, one could not find an example of a pagan people switching allegiance to another god (2:10–11). Israel’s action is irrational. She has exchanged God—with his deliverance at the exodus, his law at Sinai, his care of the people in the wilderness, and his blessing of Canaan—for a god of no worth. It is a bad bargain. The move is shocking. The heavens are court witnesses (2:12).

Israel is like a man who decides to dig for water despite the artesian well on his property (2:13). Beyond the hard work of digging the cistern and lining it with plaster, he faces the problem of leaky cisterns, not to mention stale water. The unsatisfactory “cisterns” (Egypt and Assyria) are described in 2:14–19. Living (fresh) water is at hand (Is 55:1; Jn 4:1–26). Enough has been said to dispose the court in favor of God and against Israel.

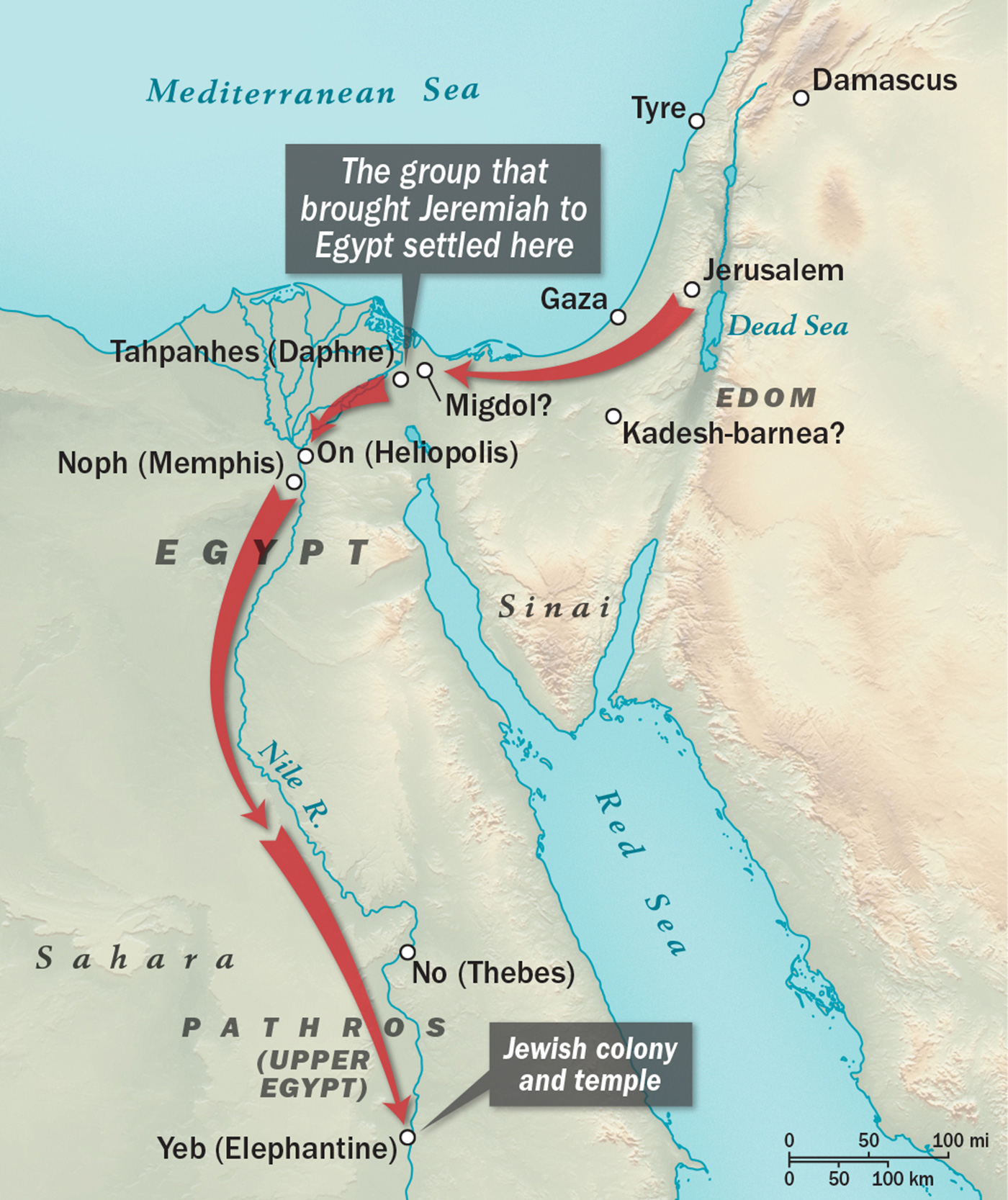

2:14–19. In a series of questions, God both accuses his marriage partner and brings her to reconsider her ways. The first two questions (2:14a), about status, imply a negative answer: No, Israel’s destiny was not to be some servant or slave. Next, God raises a question about Israel’s ravaged condition (2:14b). Since the lion was the insignia for Assyria, that country may be in view (2:15). Memphis was the capital of the pyramid-building Pharaohs, and Tahpanhes was a Nile Delta fortress city (2:16). Egypt had “broken [Israel’s] skull.” The expression certainly refers to a defeat or humiliation brought on by Egypt, possibly a raid into Israel’s choice lands.

Jeremiah 2:8 criticizes prophets who “prophesied by Baal and followed useless idols.” This figurine of the god Baal is from Megiddo, in northern Israel, from the period before the monarchy.

© Baker Publishing Group and Dr. James C. Martin. Courtesy of the British Museum, London, England.

The next question is about assigning blame (2:17). The final two questions concern direction (2:18). Will Israel go for help to Egypt, which has already mistreated her? Or to Assyria, which has invaded the ten northern tribes and occupies the area just north of Jerusalem? The summary accusation is that Israel has forsaken her covenant partner and has no reverence or appropriate fear of God (2:19). The title “Lord God of Armies” speaks of power and rulership.

2:20–28. God’s pleas fail. Hard evidence must now be marshaled. The yoke continues the figure of a partnership, a binding relationship (2:20a; given the line of argument, it may be preferable to follow those ancient manuscripts that read, “you broke your yoke” [see the CSB footnote]). The Canaanite god Baal (2:23a) was worshiped on hilltops and in the shelter of large, spreading trees (2:20b)—a practice noted in Hs 4:13 and forbidden in Dt 12:2.

Figures of speech follow in profusion. The vine, Israel, is of a good variety (2:21). The lye and bleach metaphor stresses the deeply ingrained nature of Israel’s evil (2:22). The young camel, wobbly on its feet, illustrates how directionless Israel is as she crisscrosses her ways (2:23b). The donkey at mating time (2:24) illustrates the passion with which Israel pursues the Baals even in the valley (2:23a), which, if the Hinnom Valley, would be the place for child sacrifice.

In sarcasm, God warns Israel in all this pursuing of other gods not to stub her toe (to use a modern idiom) or to overexert and so become thirsty (2:25a). Israel, self-consciously determined to do evil, responds in fiery language (2:25b). The wood posts and stone pillars mentioned in 2:27 were both worship objects in the Baal cult.

2:29–37. Courtroom language continues. God complains of breach of covenant, as exemplified by the way Israel handles correction, treats the prophets, and announces her independence (2:29–31). Her deliberate desertion is incomprehensible, since God and people, like bride and wedding gown, belong together (2:32).

Four additional accusations undermine any protests of innocence: (1) Israel has sought other lovers, and in such an abandoned way as to teach the professionally evil women, the prostitutes, a thing or two (2:33); (2) Israel is guilty of social violence by killing off innocent ones (2:34); (3) Israel is guilty of lying by claiming she has not sinned (2:35); (4) flighty behavior puts her in league once with Egypt, next with Assyria, but not with the Lord (2:36).

God’s patience is huge but not infinite. A court sentence is missing but is implied in the announcement of Israel’s exile from her land, for to go with hands on one’s head is to go as a captive (2:37).

3:1–5. Israel acts as though she can at any time sweet-talk her way back to God. Not so. The law forbade a divorced husband from returning to his former, now-married wife (Dt 24:1–4). Israel is now “married” to Baal (3:1).

Israel has not simply been overtaken by temptation; she has deliberately planned to be promiscuous (3:2a). Language of prostitution has a double meaning (3:2b–3): physical unfaithfulness in marriage and spiritual disloyalty to God (sacred prostitution was part of Baal worship). Israel’s immature appeals to a supposedly indulgent father only add to the ugly picture of her evil (3:4–5).

B. A story of two sisters (3:6–4:4). Two sisters, Israel to the north and Judah to the south, are each characteristically tagged: “unfaithful” Israel, and “treacherous” Judah (3:6–7). In 722 BC Assyria captured Samaria and occupied Israel. In Jeremiah’s time Judah was still an independent nation, but the Assyrian garrison was only a few miles away. God argues that Judah is more evil than Israel. For Israel, distressed because of God’s punishment, there is an earnest plea to return to God. For Judah, there is a short but very stern warning (4:3–4). The passage is piled with wordplays on the word “turn,” which in its various forms occurs sixteen times in the Hebrew. The messages date early in Jeremiah’s ministry, during Josiah’s reign, possibly between 625 and 620 BC.

3:6–10. Ever-turning Israel is accused of prostitution (3:6). Prostitution, with its overtones of desertion from the marriage partner and illicit sex, is a graphic way of describing Israel’s unfaithfulness to God. God’s harsh action in divorcing Israel by sending her into exile (3:8) should have been a lesson to Judah, who not only saw all that happened (3:7) but was herself severely threatened by the Assyrians (2 Kg 18–19). Stone pillars, sometimes representing the male sex organ, and trees or wood poles representing the female deities were standard Baal symbols (3:9).

3:11–18. Instead of making the expected judgment speech, God issues a plea for ever-turning Israel to turn once more, this time to him. In 3:12–14 three exhortations occur: “return,” “acknowledge,” “return.”

Model of the ark of the covenant

The appeal is persuasive. God advances reasons for Israel to return: (1) he is merciful (3:12); (2) repentance is demanded because of the breach of covenant (3:13); (3) he is still Israel’s husband (3:14; see the CSB footnote); (4) good things will follow if they repent (3:15–18). Among these good things are return from exile, godly leaders, shepherds, prosperity, a holiness extending to the entire city of Jerusalem rather than just the ark, a transformed heart, fulfillment of an earlier promise that nations would be blessed through Israel, and a returned and unified people.

The ark (3:16) was a box in which were kept the stone tables of law that symbolized the presence of God. It had been relocated during Josiah’s reform into the most holy area in the temple (2 Ch 35:3). To do away with the ark would be radical in the extreme. In the new era all of Jerusalem would contain God’s presence. Also striking in these announcements is Israel’s return to the land from the exile, a frequent subject in Jeremiah (24:6; 30:1–3; 31:17; 32:37). [What Happened to the Ark of the Covenant?]

3:19–4:2. God advances further motivations for the people to return to God. Jeremiah 3:19 is not so much a statement as it is a thought, a dream. For a moment we see inside God’s mind. He schemes how he can give his people the very best, and he has pleasant thoughts of how in response Israel would in love call out “My Father” (cf. 31:9). Imagery in this section moves between marriage (3:20) and family.

The dream is shattered, yet it continues. Hypothetically, we must understand, God envisions a change, as though he hears voices calling to him from out of Israel’s perversion (3:21). In imagination, so one must suppose, Israel does an about-face. The people who said they wanted nothing but to go after alien gods (2:25) now declare the Lord, Yahweh, to be their God (3:22). They admit they were wrong and that from the mountains (the place of noisy Baal worship) no help could come (3:23). The “shameful” gods are Baals (3:24; see the CSB footnote). Here is no attempt to look good. Here is no excuse and no belittling of evil (3:25). The speech, however, is God putting words in Israel’s mouth.

For this reason the divine response begins with “if” (4:1). Ever-turning Israel might turn, yet fail to turn to God. Turning to God demands action as well as words. Negatively it means throwing away the detestable things—all that is ungodly. Positively it means a change in behavior to just and righteous dealings (4:2). Then Israel can rightfully make promises by invoking the name of the Lord. Meeting the conditions means good things to nations who will be blessed and who will give the Lord praise; for God’s eye is not on his people alone but on other peoples as well.

4:3–4. After the message to Israel (3:11–4:2), Jeremiah turns to his immediate audience, the city of Jerusalem and the territory of Judah (4:3a). This group will be the focus of the book until chapter 30. Israel appeared ready to change, and so the plea. But Judah is hard, and therefore a threat.

The call is for drastic action. The hard soil of stubbornness is to be broken before good seed is sown—otherwise it will still fall among thorns (4:3b). In spiritual renewal one cannot shortcut repentance. The exhortation turns from agricultural to physiological symbolism (4:4a). Circumcision for Israel was a physical sign of the covenant (Gn 17:1–14). Since it signified a people spiritually linked with God, circumcision talk came to be associated with the heart. The circumcision of hearts refers to removing whatever spiritually obstructs (Dt 10:16). The sense is of giving oneself totally to God’s service.

God’s anger—a very frequent theme in the book—will go forth as a fire so hot that stopping it is impossible (4:4b).

C. Trouble from the north (4:5–6:30). The story now shifts from marital language to military language. In his capacity as a watchman, Jeremiah sees a God-appointed nation about to invade Palestine. The destroyer “from the north” (4:6), frequently mentioned in subsequent chapters, is unnamed but later identified as Babylon (27:6). The large Assyrian Empire, which had dominated the Middle East for 150 years, crumbled quickly after the rise of Nabopolassar, the Babylonian, in 626 BC. This oracle is likely early in Jeremiah’s ministry, before 621 BC or between 612 BC and 608 BC.

In earlier prophets a judgment speech classically included an accusation followed by an announcement. In Jeremiah both elements appear, but not in the usual order. In broad strokes, however, one can identify the sequence: announcement (4:5–31); accusation (5:1–13); threat and further accusation (5:14–31); warning (6:1–9); further warning (6:10–21); and second announcement (6:22–30). The announcement is about the invader. God’s accusation attacks Judah’s lack of moral integrity, spiritual dullness and social injustice, and widespread covetousness and corruption. Laced within announcements, accusations, and warnings are expressions of the prophet’s great sorrow and appeals by God to a people to wash their hearts and to walk in the old paths.

4:5–18. Urgency is the note in 4:5–18. Through short, command-like calls, people are urged to leave their fields and hurry into the walled cities, Zion (Jerusalem) in particular (4:5). The power of the nation bringing disaster “from the north” is lionlike (4:6–7). Before it the leaders, both political and religious, lose their courage (4:9).

Lions stride along the lower section of the facade from the throne room of Nebuchadnezzar’s southern palace in Babylon (sixth century BC). Jeremiah 4:7 appropriately compares Babylon to a lion that “has left his lair.”

Jeremiah 4:10 is the first of the prophet’s many personal responses. Jeremiah is markedly affected by the message he preaches. Boldly he faces God with the contradiction—as listeners would see it—between what has been promised and what is. But the deceit is not to be attributed to God; it is Jerusalem’s wickedness that accounts for the impending disaster.

The burst of the invading nation on the scene is graphically pictured as a windstorm of hurricane proportions (4:11–12). The announcement of the army’s march is sounded first from Dan, Israel’s northern border town, and then from Mount Ephraim, roughly in the middle of Palestine, thirty miles north of Jerusalem (4:15). Like a security force, the enemy directly surrounds Judah’s cities (4:16–17). Judah need not ask why. Her rebellion has brought disaster on her (4:18).

4:19–31. The upcoming invasion is not a skirmish but an onslaught that will demolish everything. Like a photographer using a zoom lens, the prophet first gives an initial picture of the devastation of the whole earth (4:23–26), then a wide-angle shot of all the land (4:27), and finally a close-up of what happens in a town (4:29). The earth becomes chaotic, formless, and empty, as it was before the creation (Gn 1:2). There are four references to nonlife (earth, heaven, mountain, hill) and four mentions of life (humanity, birds, fruitful land, cities) (4:23–26). Behind that army is God’s wrath. God is fully committed to this action of judgment and will not be dissuaded.

God complains that his people are as those who have not known (i.e., experienced) him; they are unwise and undiscerning (4:22). Proof of their lack of discernment is that Judah, sitting atop a dynamite keg, misreads the situation: with trouble about to break in on her, she is primping herself with cosmetics and jewelry (4:30). She is preparing to meet her lovers, who are really her murderers.

The description of devastation is bracketed by expressions of pain and hurt. Jeremiah is bent over with pain, as with prophetic perception he hears the war trumpet and sees the war flag (4:19–21). The invaders are like murderers who will strangle Judah to death (4:31).

5:1–13. So far, statements about Judah’s evil have been only sketches. Now the people are commanded to investigate the moral situation by means of a citywide poll to show that the place, like Sodom and Gomorrah (Gn 18:23–33), totally lacks persons of integrity. And worse—people are defying the Lord. The poll gives warrant for God’s severe judgment. Were there even only one who would seek after truth, God would pardon the city! Jeremiah 5:1 refers to honorable and upright relationships, in every social contact or transaction. Justice is a prime requirement of God’s people. Some merely mouth the words of an oath (5:2). Taking the oath, however, is not proof that people mean it.

Jeremiah participates in the research. The poor are not excused because they are poor but are faulted for hard-heartedness (5:4). The leaders, who have every advantage, fail the test (5:5). Besides, they lead in breaking the relationship (yoke) between people and God. Deliberate defiance and covenant breaking will bring God’s judgment—attack by wild animals (5:6).

God responds to the statistical research. Like a highly sexed male horse, Judah goes neighing adulterously after another man’s wife (5:8). Prosperity apparently has led to luxury, which led to sexual liberties. God will judge sexual promiscuity. The people disparagingly suggest that God does not know what is going on, or if he does, he is too nice to punish (5:12)! Vineyard language of pruning (5:10) is figurative for enemies “pruning” Israel. In mercy God stops short of complete destruction. There is a difference between punishment and annihilation.

5:14–19. The people conclude that God will not punish them. God will give to Jeremiah fiery words that will devastate the people’s arguments (5:14). Babylon, still unnamed, will demolish Judah’s fortresses and consume stored provisions as well as current harvests (5:15, 17). The sense of 5:16 is that their arrows are deadly. War casualties are many.

5:20–31. A second round of announcements and accusations begins in 5:20, in which greater stress is put on the evils that necessitate severe judgment. Specifically, Judah has spurned the Creator God, and within society, including even religious life, people practice injustice.

God presents himself as the Creator, basically the God of space and time. God curbs the mighty sea (5:22) and ensures the regularity of the seasons (5:24). Yet his people, unimpressed, have violated God’s limits and have no awe before him. Irreverently, their eyes and ears are closed to God’s wonders (5:21). Along with the evils of omission are evils of defiant action. In a rebellious spirit they have deserted their God, much to their own hurt, for the rains have ceased (5:23, 25). Sinning people cheat themselves out of what is good.

On the human plane there are likewise sins of action and sins of neglect. Evil persons, like hunters of game, fill their traps (cages) to the limit (5:26–27). By their clever maneuvers, they exploit other people. Their riches have accumulated, due to their deceptive schemes. They are described as overstepping even the usual evils. They have neglected the defense of orphans and other marginal people who do not have access to power (5:28). God makes careful treatment of the disadvantaged a measuring stick for social righteousness (cf. Mc 2:1–5; Is 3:13–15).

Corruption has penetrated even the religious arena (5:30–31). Prophets prophesy falsely. The priests are conniving power grabbers who use their position unethically. For these evils God would judge any other nation. And Israel is no exception (5:29).

6:1–9. Earlier, people hurried into the city for safety (4:5). But now the invader (compared to a nomadic shepherd whose flocks eat away the pasture, 6:3) has moved southward to Benjaminite territory just north of Jerusalem (6:1). God will destroy fragile Zion (6:2).

Attacks are made early in the day (6:4). The commander barks orders; the attackers are determined. The Lord, now on the side of the enemy, adds his orders to build a ramp up against the city wall (6:6a; cf. 21:4). Oppression, violence, and plundering are the reasons for this turn of events (6:6b–7). God may, if Judah does not take warning, do even worse by turning completely away and not restraining the enemy at all (6:8). The enemy will make a thorough search, like a grape gatherer reaching into the vine branches, for the last fugitive (6:9).

6:10–21. With language heightened in intensity, additional reasons are given for the invasion: disinterest in God’s message (6:10); covetousness (6:13a); corrupt religious leaders who fail to be radical but instead do easy counseling, assuring peace and well-being (6:13b–14); callousness about evil (6:15); intentional disobedience (6:16–17); and rejection of God’s word (6:19). Sacrifices continue with rare incense from Sheba in Arabia and specialties possibly from India (6:20). But these are unacceptable because of Judah’s moral condition.

Even so, Jeremiah gives warning; God counsels Judah to return to the older, tried lifestyle and calls forth watchmen (prophets, 6:17a). The warning, however, is not heard because of stopped-up (uncircumcised) ears (6:10), nor is ear given to the prophets (6:17b). God will therefore unleash his anger (6:11–12). Nations are called to witness that such proceedings are just (6:18–19). Jeremiah’s personal outrage seems to ignite God’s anger, for in the interchange both become increasingly exasperated. [Stumbling Block]

6:22–26. Throughout the larger block (4:5–6:30) more and more details about the invader from the north have been supplied. Here the army is depicted as advancing fully armed and altogether cruel and merciless (6:23). The defenders are hopelessly enfeebled (6:24). Escape routes are cut off (6:25). Jeremiah anticipates sackcloth rituals of mourning for those slain (6:26).

The foe from the north (6:22) has been said to be the Scythians, but that is hardly likely since their invasion is historically questionable. Since in mythology the mountain of the north was not only the home for the gods but also the source of evil, some have advocated that Jeremiah used this myth to generate fear and foreboding. Most likely, even though the enemy remains unnamed and may initially not have been known to Jeremiah, the army “from a northern land” was the Babylonian army.

6:27–30. Jeremiah is to assay the worth of metals (6:27). Lead was added to silver ore so that when heated, it would remove alloys. Here there is ore, but not enough silver. Jeremiah’s conclusion: these are “stubborn rebels” (6:28). There is no true Israel. This negative judgment is elsewhere tempered with some words of hope. But now, refine as one will, there is no precious metal, only scum silver at best, which is to be rejected (6:29–30). On this hopeless note ends a passage that has included strong warnings, earnest appeals for change, and dire threats.

D. Examining public worship (7:1–8:3). The basic mode of poetry in 2:1–10:25 is interrupted by a prose sermon. The sermon, a sharp attack on moral deviations and misguided doctrinal views about the temple, stirs up a vehement response, as we learn from a parallel account in 26:1–15. Attack on venerated tradition is risky business (cf. Ac 7). The sermon, on worship, leads to some instructions designed to correct misguided worship (7:16–26) and to halt bizarre worship (7:27–8:3). It is a prelude to further talk about siege (chaps. 8–10). Similarly, the sermon of chapters 2–3 precedes the announcement of the northern invader (4:5–6:30).

7:1–7. The temple gate, perhaps the so-called New Gate (26:10), from which Jeremiah spoke (7:2), belonged to the three-hundred-year-old Solomonic temple. The call to reform is given without preamble but with specifics. The famous temple sermon at once identifies the points at issue: a call to behavioral reform and a challenge to belief about the temple (7:3–4). The first point is amplified in 7:5–7, the second in 7:8–11. A biting announcement concludes the sermon, which was preached early in the reign of Jehoiakim.

Practicing justice—that is, the observance of honorable relations—is a primary requirement (7:5). Specifically, “doing justice” (as contrasted to the Western notion of “getting justice”) means coming to the aid of those who are helpless and otherwise the victims of mistreatment, often widows, orphans, and strangers (7:6a). To shed innocent blood is to take life by violence or for unjust cause (7:6b). The gift of land was outright (7:7); the enjoyment of that gift was conditional. The theme of land loss and land repossession is frequent in Jeremiah (16:13; 24:6; 32:41; 45:4).

7:8–15. A second consideration is a popular chant that had become a cliché: “the temple of the LORD” (7:4). Its popularity arose from the teaching that God chose Zion, and by implication, the temple (Ps 132:13–14). A century earlier, with the Assyrian threat, God had shielded and spared the city (2 Kg 19). Any threat to the city’s safety was apparently shrugged off with the argument that God would protect his dwelling place under any circumstance. A theology once valid had become stale, even false.

Jeremiah points to violations of the Ten Commandments (7:9; Ex 20:1–17). It is incongruous that people who steal and go after Baal, this Canaanite nature deity of weather and fertility, should claim immunity on the basis of the temple. Brashly these worshipers contend that standing in the temple, performing their worship, gives them the freedom to break the law (7:10). The temple, like a charm, has become a shelter for evildoers. Theirs is (eternal) security, so they think. Yet God sees not only their holy worship but their unholy behavior (7:11).

The clincher in Jeremiah’s sermon comes from an illustration in their history more than four hundred years earlier (7:12–15). Shiloh, located in Ephraimite territory some twenty miles north of Jerusalem, was the worship center when Israel entered the land (Jos 18:1). Eli was its last priest. It was destroyed, likely by the Philistines. Samaria, the capital of Israel, was taken by the Assyrians in 722. God threatens to do to Jerusalem what he did to Shiloh and Samaria.

As he pronounces judgment on the temple, Jeremiah calls the place “a den of robbers” (Jr 7:11). In the NT, Jesus likewise implies judgment as he quotes this verse to the market sellers in the temple (Mt 21:13; Mk 11:17; Lk 19:46).

7:16–20. The people’s worship is misguided in two ways: they offer to the queen of heaven (7:16–20), and they offer to God but without moral obedience (7:21–26).

The queen of heaven (7:18) was Ishtar, a Babylonian fertility goddess. Worship of Mesopotamian deities became popular with Manasseh (2 Kg 21:1–18; 23:4–14). Such apostate worship was anything but secret since it involved entire families. Cakes, round and flat like the moon or possibly star-shaped or even shaped like a nude woman, were offered as food to this deity. But any worship of gods other than Yahweh is a violation of the first commandment. Violations bring dire consequences.

7:21–26. The tone of 7:21 is sarcastic. Some offerings required participants to eat meat; others, such as burnt offerings, were to be offered in their entirety. God did, of course, give commandments in the wilderness about sacrifices (7:22; cf. Lv 1–7).

External worship practices are empty without a devoted heart. Three factors should encourage obedience: (1) the promise of covenant, a part of God’s initial design (7:23a; Ex 6:7; variations of the formula “I will be your God, and you will be my people” occur twenty times in the Bible); (2) total well-being (7:23b); and (3) prophets to encourage it (7:25).

7:27–31. Again the people are charged with failure to receive correction (7:27). The result is the disappearance of truth and integrity (7:28) and a turning to a bizarre religion (7:30–31). God’s punishment will be as outlandish as their practice is bizarre. Anticipating that awful death, Jeremiah is commanded to cut his hair and to cry on the bare hilltop, as was customary to mark a calamity (7:29).

Vandalism in worship exists. Representations of other deities were brought into the temple reserved for Yahweh (7:30). The Ben Hinnom Valley, also known as Topheth (7:31), is immediately south of old Jerusalem. Topheth (“Fire Pit”) was a worship area (high place) in this valley. Child sacrifice was introduced by Ahaz and Manasseh (2 Kg 16:3; 21:6), abolished by Josiah (2 Kg 23:4–7), but renewed by Jehoiakim.

7:32–8:3. This judgment speech predicts that the deaths either through plague or military slaughter will be so overwhelming that the valley’s new name will be the Valley of Slaughter (7:32). The sacrifice area will become the cemetery. None will be left to chase off vultures who feed on corpses (7:33). Bones of past kings will be exhumed by the enemy as an insult (8:1). The astral deities, so ardently served and worshiped, will look on coldly and helplessly (8:2).

E. Treachery, trouble, and tears (8:4–10:25). “If my head were a flowing spring, my eyes a fountain of tears, I would weep day and night” (9:1). It is from such expressions that Jeremiah has been called the weeping prophet. The prophet aches for his people. Trouble will be everywhere, and it will be terrible. And the reason is that God’s people have forsaken God’s law (8:9; 9:13), and they have not repented of their evil. Jeremiah’s emotional outpourings of sorrow are a new dimension in the development of the theme of judgment.

As the book now stands, this kaleidoscope of accusation, threat, and lament—mostly in poetry—follows the temple sermon, which is in prose. One can discern three rounds of presentation: 8:4–9:2; 9:3–25; 10:1–25. Three sections occur in each round: the people’s sins (8:4–13; 9:3–9; 10:1–16); the coming trouble (8:14–17; 9:10–16; 10:17–18); and sorrow in the minor key (8:18–9:2; 9:17–22; 10:19–25).

8:4–13. Those who stumble ordinarily get up. Those who find themselves on a wrong road turn around. Not so Israel. The words “turn” and “return” occur five times in 8:4–5. Like horses with blinders, Israel stubbornly charges ahead (8:6). Israel has less sense than birds or animals, whose instinct at least returns them to their original place or owner (8:7).

There are four other problems: (1) Pseudowisdom. Judah prides herself in the possession of the law, possibly a reference to the newly found law book (Deuteronomy?) in 621 under Josiah (2 Kg 22:1–10). “The lying pen of scribes” (8:8) does not refer to miscopying or questionable interpretations as much as to leaving a corrupt society unchallenged. (2) Greed. All strata of Hebrew society crave the accumulation of wealth (8:10a; cf. 6:12–13a). (3) Lying. Religious leaders treat Israel’s serious wounds (her crisis of wickedness) lightly. They say that all is well (8:10b–11; cf. 6:13b–14). The duty of prophets was to expose evil, not to minimize it. One can be occupied with God’s word yet have an unscriptural message. (4) Failure to feel shame. The prophet, in contrast to Israel, knows what time it is (8:12–13; cf. 6:15).

8:14–17. The list of harmful consequences continues. It is now the people who understand that the human evils of the enemy’s advancing cavalry and poisoned water (8:14b), as well as natural evils such as poisonous snakes (8:17), are God’s agents. Sarcastically it is noted that people leave the fields only to die in the cities (8:14a). Resistance is futile. Poisonous adders cannot be charmed; horses, like modern cruise missiles, are unstoppable (8:16–17).

8:18–9:2. We have here not a dispassionate onlooker but a tender caregiver torn up over the news of the coming disaster (8:18). The prophet, perhaps imaginatively, hears the cry of a now-exiled people. Plaintively they ask about God, their king (8:19). At the same time, the prophet hears God saying in effect: “I can’t stand their idolatry.” Listening once more, the prophet detects the hopeless cry of those in exile who approach a dreaded winter without provisions (8:20). The early harvests of grain (May–June) and the later harvests of fruits (September–October) are over. This agricultural allusion may be a way of saying, “We counted on help (our own or that of others), but nothing came of it.”

The prophet identifies with the people (“my dear people,” 8:19, 21, 22; 9:1). Since they are crushed, he is crushed (8:21). The prophet is beside himself with grief. Exhausted, he cries and wishes for his head to be a never-ending fountain so that he could cry more (9:1). On the other hand, he would like to get away from it all (9:2). The people’s sins disgust him. Prophets did not stand at a distance lobbing bombshells; they were closely involved with their listeners.

9:3–9. Lying, mentioned in 8:10, is now treated in full as a major problem. Deception has replaced integrity as a way of life. Out of a false person come falsehoods.

The tongue and its lies are pictured as a bow and arrows (9:3, 8). Lies have a lethal quality about them. Jeremiah 9:4 has a clever turn of phrase: “Jacob” is synonymous with “deceiver”; hence, literally, everyone deceives (“Jacobs”) his brother. [Refine]

For any other nation such flagrant violation of truth and integrity would mean God’s punishment. Should Israel be spared (9:9)? It is as though God throughout wrestles with the issue of what is the just and right thing to do.

9:10–16. The “I” of 9:10 is Jeremiah, who once more responds emotionally by weeping at the prospect of punishment. The desolation is complete. No mooing of cattle and no sound of birds are heard. All signs of life are gone (cf. 4:25). The “I” of 9:11 is God. Scattering among the Gentiles will be a fate for some, death by the sword the fate for others (9:16). The title “LORD of Armies” does not leave the outcome of his decision in doubt (9:15).

Such destruction calls for an explanation (9:12). In a nutshell the reasons are faithlessness to the law (in which they boasted, 8:8), disobedience to the Lord, a godless lifestyle, and long-practiced idolatry of the Canaanite variety (9:13–14). Other reasons are given in 9:3–9.

9:17–22. Voices of wailing in response to the total destruction come from three quarters. First, professional women mourners, usually engaged to prompt crying at funerals and calamities, are hurriedly summoned to lament this awful disaster (9:17–18). Second, wailing is heard from Jerusalem itself, where plundered fugitives explain that they must vacate their dwellings and leave their land because all is ruined (9:19). Third, since in the future, mourners will be in great demand, the professionals are urged to train daughters and neighbors in the art of mourning (9:20). The epidemic is described metaphorically (9:21).

9:23–26. The Lord describes proper boasting (9:23–24). The “wise” have been noted in verse 12 and again in verse 17. “Wisdom” and “wealth” could refer to the royal lifestyle under Solomon. Jehoiakim gloried in riches, in contrast to his father, Josiah, for whom knowing God was important; knowing God meant caring for the disadvantaged. Faithful, covenant love is voluntary help extended to those in need. Justice includes honorable relations in every transaction. Judged by this quality alone, the situation described in the foregoing verses is nauseating. Righteousness is that inner disposition of integrity and uprightness that issues in right action.

The nations listed (9:26) were likely in a military alliance against Babylon. The historical situation is assumed to be 597, when Nebuchadnezzar led an attack against Jerusalem. For Israelites to hear their country named along with others must have been shocking. Yet this emphasizes that inner obedience is more crucial in God’s sight than mere outward compliance.

10:1–16. The blistering tirade against idols is directed against “Israel,” which as an umbrella term includes both Israel and Judah (10:1). Here Judah is particularly in view. Judah is warned about the astral deities commonly worshiped in Babylon (10:2). The contrast between homemade idols and the living God has seldom been better drawn, by alternating a mocking poem with a doxology: idols (10:3–5), God (10:6–7), idols (10:8–9), God (10:10), idols (10:11), God (10:12–13), idols (10:14–15), God (10:16).

With cutting sarcasm, the Lord describes the process of shaping, stabilizing (10:3–4), and clothing these gods (10:9). The idols are nonfunctioning (10:5). They are an embarrassment to their makers and will be the object of divine punishment (10:14–15). Fear, quite inappropriate before idols, is necessary before God (10:5–7).

To clinch the contrast with the unnamed figurines, God is given a name: Yahweh (“LORD,” 10:6, 10), the Lord of Heaven’s Armies (10:16). He is also known as “King of the nations” and “eternal King” (10:7, 10). From a statement about his incomparability (God is in a class by himself, 10:6) and his function as Creator (10:12–13), the writer moves to God’s crowning activity: his election and shaping of Israel to be his special people (10:16).

10:17–18. The crisp word about picking from the ground the fugitive’s bundle (10:17; see the CSB footnote) announces the theme of coming trouble heard throughout these chapters. God serves notice, as to a tenant, that he will fling out the inhabitants (10:18). There is about this a tone of final warning.

10:19–25. Judah is without shelter and without family (10:20). Blame properly falls on Judah’s leaders, chiefly kings, who have failed to seek God (10:21). The destruction comes at the hand of the northerner—still unnamed but later identified as Babylon (10:22).

Instead of taking satisfaction in his announcement coming true, Jeremiah interjects a cry of woe (10:19). Jeremiah speaks again in 10:23. Given the dull-hearted leaders, he is unsure of his next step. The request to be corrected may be for himself or may be made on behalf of the people (10:24). The prayer for God’s anger to fall on the Gentiles could be a quotation from the people (10:25; cf. Ps 79:6–7). Like the prayers for vengeance (Pss 109; 137), while not representing the NT ideal of loving enemies, the prayer at least turns the situation over to God instead of taking it in hand personally.

3. STORIES ABOUT WRESTLING WITH PEOPLE AND WITH GOD (11:1–20:18)

The preceding chapters, though grim with dark announcements and heavy accusations, have had a formal cast. Only rarely has the prophet expressed personal anguish. In chapters 11–20, however, Jeremiah as a person is much more at center stage. In these stories Jeremiah wrestles hard to persuade his audience of their serious situation. He engages in sign acts. Here also we observe a man wrestling with God as he deals with frustrations and discouragements. The so-called laments or confessions—seven of them—are unique windows into the prophet’s interior life (11:20–23; 12:1–4; 15:10–11, 15–21; 17:14–18; 18:18–23; 20:7–13).

A. Coping with conspiracies (11:1–12:17). Two scenes of conspiracy dominate chapter 11. The first is a conspiracy of a covenant people against its covenant God (11:9–13). In the second conspiracy, in the private arena, plotters conspire to do away with Jeremiah (11:18–19). The double conspiracy leads to two personal encounters with God in which the prophet pours out his complaint (11:20; 12:1–4). In each case God answers, but not necessarily as Jeremiah expected (11:21–23; 12:5–17).

11:1–8. Covenant has been a presupposition in the foregoing chapters, but it is now made explicit. At stake in the covenant relationship are intimacy and loyalty. The intimacy factor is pinpointed in the covenant formula: “You will be my people, and I will be your God” (11:4). The loyalty component is explicit in the command “Obey.” To “obey” (very frequent in 11:2–8) is to comply with the will of another. The charge that Israel has not obeyed is repeated more than thirty times in chapters 7, 11, 26, 35, and 42.

Deuteronomy 28 forms the critical covenant background for understanding Jr 11.

“This covenant” (11:2) may be the renewed covenant under Josiah (2 Kg 23). More likely, because the context is ancestors and Egypt (11:4, 7), it is the Sinai covenant (Ex 19–24). Since the Josianic covenant was a renewal of the earlier covenant, we may properly see in these verses Jeremiah’s aggressive preaching on behalf of the reform launched by Josiah in 621 BC.

Deliverance was the presupposition for covenant (11:4a). The idiom “land flowing with milk and honey” (11:5) suggests paradise and in Western idiom could be rendered “God’s country.” Set in between these grace gifts is a call to obedience (11:4b).

Covenant, like ancient political treaties, invokes strong curses on the party that fails to observe the treaty terms (cf. Dt 27:15–26). God threatens to set these curses in motion (11:3, 8). By saying “Amen” (11:5), Jeremiah consents to this understanding of covenant and invites his audience to stand with him on common ground.

11:9–13. These verses are in the pattern of the traditional judgment speech, which begins with an accusation (11:9–10) and ends with an announcement (11:11–13). The accusation becomes the reason for, and shapes the nature of, the announcement.

The accusation is conspiracy (11:9). Both Judah and Israel have conspired to return to old ways (11:10). In defiance they have gone after other gods. In political language this is an act of treason. Jeremiah puts it boldly and shockingly: they “broke my covenant.”

11:14–17. God closes the door to any change of mind by forbidding prophetic intercession (11:14). The sense of 11:15 is that Judah/Israel, God’s beloved, has no business in his temple (perhaps meaning the land) because she has plotted numerous times against him. Sacrifices, which she still offers, are called “holy meat” to suggest her notion that only the outward matters.

Now Israel, a highly desirable and potentially productive olive tree, is hit by a lightning storm and destroyed (11:16). Covenant curses have been activated (11:17).

11:18–23. To pronounce the covenant broken is to stir opposition. The people of Anathoth, Jeremiah’s townsfolk, are almost certainly his immediate family (11:21; cf. 12:6). Embarrassed, then incensed, they eventually plot murder (11:18–19). People who resent a disconcerting message resort to silencing or eliminating the messenger (cf. Am 7:12; Jesus in Jn 19; Stephen in Ac 7:54–59).

The episode triggers an appeal by Jeremiah to God for him to deal with the plotters. As a righteous God, he tests “heart and mind” (11:20). Together the two terms represent a person’s internal motives. Commendably, the prophet refrains from retaliation.

Jeremiah’s prayer in Jr 11:20 for God to bring judgment is in accord with the teaching, “Vengeance belongs to me; I will repay, says the Lord” (Rom 12:19; cf. Dt 32:35).

God’s response to bring disaster on the plotting townsfolk must be seen as a miniature scene showing how God can be expected to deal with covenant partners who conspire. Jeremiah 11:20–23 makes up Jeremiah’s first personal lament.

12:1–4. The second of Jeremiah’s seven personal laments touches on God, the wicked, the prophet himself, and the land. Jeremiah uses court language and asks for justice, or right dealing. “Righteous” is a term of relationship describing integrity and uprightness (12:1). On what grounds can God prosper evil persons? It is an old question. The wicked discount God by claiming that God will not have final jurisdiction over them (12:4).

The prophet protests his innocence, a feature of other laments (12:3). Moral corruption has ecological effects, death among them (12:4; cf. Hs 4:1–3).

12:5–13. Verses 5–17 are a reply to the questions of verses 1–4. There are two answers. The first is to rebuke Jeremiah, saying essentially, “If such (little) problems upset you, how will you successfully deal with weighty issues?” (12:5). The Jordan Valley has its jungles—a considerable obstacle course. Here is no offer of sympathy nor divine coddling but a call to toughen up. Far harder to explain than the success of the wicked is God’s overturning of his own people.

Jeremiah 12:7–13, a second answer, gives a partial response to the evil about which Jeremiah has complained. God will judge that wicked people even though it is his inheritance, his special people (12:7). Already surrounding nations have beset her, like hawks circling overhead (12:9). The raids of hordes, including the Moabites and Ammonites, could be in view in 12:10, since kings were commonly called shepherds in the ancient Near East.

Successively God loses his vineyard, his field, and in fact, his entire portion (12:10–13). As in the previous lament (11:20–23), Jeremiah’s challenge to God’s justice becomes an excuse to reiterate the now-familiar announcement of coming destruction. One clue to the question about justice lies in the future, when God will punish his people.

12:14–17. God’s justice, about which Jeremiah has inquired, means that the nations who as God’s agents bring desolation will themselves be judged (12:14). This of course raises other issues, not addressed here but elaborated elsewhere (Is 10:5–7). One does not harm God’s possession, his people, without receiving harm in turn. But later on God will restore Moab and Ammon (Jr 48:47; 49:6). He will bless Egypt (Is 19:24). The agenda of justice has become the agenda of compassion (12:15). God’s missionary purpose must not go unnoticed (12:16–17; cf. Is 2:1–4; 19:16–25).

B. Pride ruins everything (13:1–27). 13:1–11. The ruined undergarment (13:1–7) is the first of several sign acts, dramatized attention-getters, for people who have stopped listening. Sign acts consist of a divine command, the report of compliance, and an explanation. The “linen undergarment” (13:1) is like a short skirt that reaches down to the knees but hugs the waist.

Jeremiah’s symbolic act has a double message, the first of which is the evil of pride (13:9). God detests pride (2 Ch 32:24–26; Pr 8:13). Arrogance, an exaggerated estimate of oneself, brings the disdain of others and accounts for the evils of 13:10. Second, the sign act pictures how God would take proper pride in Israel, who, like the undergarment worn around the waist, would be close, as well as beautiful (13:11). That hope was dashed.

13:12–14. Wine at harvest was put into storage jars. Two-foot-tall clay jars held about ten gallons each. Jeremiah states the obvious (or is it a riddle?) in order to secure assent (13:12). Those drunk with actual wine or with divine intoxication (25:15) are civil and religious rulers as well as ordinary citizens (13:13). The smashing of these jars suggests the violent clash between these groups, with resulting factions (13:14). The entire social structure will disintegrate.

13:15–27. A discussion of pride (13:15–20) precedes a miscellaneous collection of evils, all of which justify harsh punishment. To “give glory” (13:16) is literally to give weight or to make God, not self, prominent. To look for light is to look for the time of salvation. The picture is one of a traveler in the mountains overtaken by nightfall. The captivity, indeed Judah’s wholesale exile, is here first mentioned (13:19), even though the northern agent (Babylon) has been announced earlier (4:6). In the invasion, the fortified cities of the Negev in the south will be surrounded and blockaded, becoming inaccessible.

Jerusalem is addressed as a woman in 13:21–27. Those persons and countries whom Judah enlisted as allies will be appointed by the enemy to rule over them. Like civilian women in wartime, so Judah will be violated. She will be disgraced, stripped from head to toe, and exposed.

C. Dealing with drought (14:1–15:21). If past chapters have emphasized God’s punishment of his people through the sword, these two deal primarily with drought. Famine pushes the people to pray, even to acknowledge their sinfulness. God refuses to help; no relief is in sight. The prophet is pained by the people’s plight, and, in a different way, by his own. Chapter divisions here obscure two symmetrical halves (14:2–16 and 14:17–15:9). In each there is a description of the famine (14:2–6; 14:17–18), a prayer (14:7–9; 14:19–22), and a divine response (14:10–16; 15:1–9).

14:1–9. The drought is vividly depicted in its effect on high-ranking people, farmers, and animals (14:3–6). City gates (14:2), more like open areas comparable to modern malls, were places for merchandizing and legal transactions. All has come to a standstill because of the downturn in the economy. To “cover their heads” (14:3) was a cultural expression of embarrassment or frustration.

When people’s livelihood is in jeopardy, they pray. There is recognition of iniquity and acknowledgment of their continual rebellion and sin (14:7). The name Yahweh (“LORD”) means “I Am Present to Save,” yet the people chide God for being uninvolved and for failure of nerve (14:8–9). They seek consolation from old assurances and, in bargaining fashion, ask that God forget their sins.

14:10–18. The finality of God’s “No!” to the people’s prayer (14:10) is evidenced in his forbidding prophetic intercession (14:11). All access to God such as fasting and sacrifice is barred (14:12; cf. Is 58:3–11). False prophets who keep announcing good times and “lasting peace” are Jeremiah’s constant irritation (14:13). His experience of seeing victims of sword (animals put out of misery) in the field and hunger in the city totally contradicts any optimism (14:18). The conclusion: the prophets and priests, who are called to show the way, wander aimlessly.

14:19–22. Suffering, such as hunger, is not necessarily sin related; however, this famine is a judgment. Hope for an answer lies in the Lord’s name, his covenant, and his creation power (14:21–22). “Don’t disdain your glorious throne” is an appeal on the basis of the temple (17:12).

15:1–9. Again intercession is ruled out. Moses and Samuel, both prophets, interceded at critical times (15:1). God fulfills an earlier announcement not to hear pleas for help (11:11). Manasseh, who ruled Judah fifty years earlier, was Judah’s most wicked king (15:4; cf. 2 Kg 21:1–8). A generation is being punished for another’s sin, but also for its own sin.

By sword or other means (15:3) God will annihilate the men, leaving widows (15:8). Once-proud mothers of many sons will gasp in their confused, possibly demented state (15:9). The covenant promising many descendants has been reversed. [Winnowing Fork]

15:10–14. Two laments from the prophet follow (15:10–21). Both are in response to the droughts and, more particularly, Jeremiah’s devastating announcement that God will destroy his people.

Jeremiah claims he is not to be faulted for the nagging and the widespread antagonism against him. He would rather not have been born (15:10). Jeremiah 15:12 is a reference to the strong northern killer nation who, like iron, will not be broken in his advance. The land will be plundered (15:13), and people will be removed from their land (15:14). The response to the prophet’s woes, instead of softening the announcement, hardens it yet more.

15:15–21. The lament of 15:15–18 is by one who shirks further engagement. The prayer for vengeance (15:15) falls short of the Christian teaching to love enemies. “Your words were found” (15:16a) may refer to the discovery of the scroll in the temple (2 Kg 22:13). High joy (to be called by the name the Lord of Heaven’s Armies and so be on the winning side) is followed by loathsome misery, hot indignation, and isolation (15:16b–17). (Jeremiah did not marry; see 16:2.) Jeremiah has disgust for his enemies and difficulty stabilizing his personal life, and he is disappointed in God, who has become a problem. Dry streambeds give a Palestine traveler the mirage of water (15:18).

God’s answer deals with all three parts of the lament. First, Jeremiah is to return (15:19a). In other words, God is saying, “If you change your heart and come back to me, I will take you back.” Second, Jeremiah must not take his cue from others (15:19b). Third, God recalls the promise of his presence given at the time of Jeremiah’s call (15:20; cf. 1:19). The prophet who levels with God finds that God levels with him. [The Laments of Jeremiah]

D. Much bad news, some good (16:1–17:27). Chapters 16 and 17 are a mixture. God privately instructs Jeremiah not to socialize; God speaks publicly about keeping the Sabbath. The people of God will be exiled, but there will be a restoration. A prophet turns to God in his frustration; Gentiles turn en masse to God in conversion. There are mini essays; there are proverb-like sayings. However, the theme remains unchanged: sin is pervasive, and judgment will be certain and terrible.

16:1–13. God gives Jeremiah three commands about his social life. The reason for each command arises out of the coming disaster. First, Jeremiah is to be celibate (16:2). Having children, which was highly desirable, is forbidden him, for all existing families will disappear. Gruesome death will come to children from terrible diseases, the enemy’s sword, and famine (16:3–4).

Second, Jeremiah must not attend funerals or extend comfort (16:5a). The reason: God has withdrawn his covenant blessings of peace, covenant love, compassion, and favor (16:5b–7). So must the prophet withdraw his involvement. Cutting oneself to show grief, though forbidden (Lv 19:28; Dt 14:1), was apparently practiced (see the CSB footnote for 16:6).

Third, Jeremiah is to avoid weddings and all parties as a way of announcing the end of all joyful socializing (16:8–9). Judah has deserted God because of the stubbornness of an evil heart (16:12; cf. 3:17; 7:24; 9:14; 11:8; 13:10; 18:12; 23:17). Forewarned of the reason for the disaster, Judah would be able to survive.

16:14–21. Placing promise oracles next to judgment oracles is not new (see Hs 1:9–10). The oracle of 16:14–15 is repeated in Jr 23:7–8, where it better suits the context. The statement is not to deny the exodus event but to emphasize that the return from exile will be even more impressive.

Jeremiah 16:16 notes that fishermen with nets will catch the masses, while hunters will catch the stragglers, so that no one will escape. The language about idols is filled with disgust (16:18).

Ironically, while Judah turns from God to idols, Gentiles, world over, turn from idols to God (16:19–20). The vision is refreshing and overpowering (cf. Jr 12:14–17; Is 2:1–4; 45:14–25; Zch 8:20–23). Gentiles are saying about these gods what God says about them. God speaks in 16:21. He will teach the Gentiles in the sense of giving them an experience of his power.

An Assyrian fisherman. In Jeremiah, fishermen catch people for judgment (Jr 16:16). Jesus reverses this, sending fishermen to catch people for salvation (Mt 4:19).

© Baker Publishing Group and Dr. James C. Martin. Courtesy of the British Museum, London, England.

17:1–4. The judgment speech in 17:1–4 consists of an accusation and an announcement. Sin written indelibly on the heart (17:1) will one day be replaced by God’s law written on the heart (31:33). Horns were corner projections on an altar to which the animal was tied and on which the atoning blood was put. Asherah poles (17:2) were wooden carvings erected to honor the astral goddess Asherah, known in Babylon as Ishtar.

The announcement summarizes the disaster. Jeremiah 17:3 refers to Mount Zion in Jerusalem, where the temple stood. High places were hilltop areas set apart for the worship of Canaanite gods. By default, the people will lose their belongings, their land, and their freedom. The cause is twofold: Judah’s sin and God’s anger (17:4).

17:5–8. In the parable of 17:5–8 the issue is in what or whom one trusts (17:5, 7). Jeremiah’s announcements, if taken seriously, would trigger military preparations. But on a national scale confidence was not to be placed in human leadership (even a new king) or in military resources. The prospect for nations or individuals leaning on human strength is death and isolation (17:6). In stark contrast, God-trusting persons are “blessed” or empowered, like a tree planted by water (17:8).

In contrast to those who trust in human strength, who are like a juniper in the wilderness, those who trust in the Lord are like a tree planted by water (Jr 17:5–8). Similar comparisons between the godly and ungodly are made in Ps 1 and Mt 7:16–20.

17:9–13. Three separate and only loosely related wisdom-like pieces are joined together. The heart, the seat of the will, is examined and diagnosed as deceptive (17:9–10). Verse 9 reflects Jeremiah’s despair in the human situation. The antidote is a heart transplant (31:33).

The proverb of 17:11 emphasizes both the wrongfulness of riches acquired by devious means and the way such riches are vulnerable to attack and loss. A partridge or calling bird is said to gather the eggs of other birds and then brood on them to hatch them.

Jeremiah 17:12 continues the motif of contrasts begun in verse 5. The temple is the place of God’s dwelling and hence the place of safety. Jeremiah 17:13 points to some disgrace or may mean consigned to death, quite opposite to “written in the book [of life]” (Dn 12:1; cf. Ex 32:32).

17:14–18. Another lament as a personal response interrupts the attention focused on the nation. It depicts Jeremiah, however, as one who trusts the Lord. To be “saved” (17:14) is to be brought from restrictive places to the freedom of open spaces. Jeremiah’s personal request for healing and salvation arises from the mocking taunts of others. They jeeringly ask about the unfulfilled announcements of disaster (17:15)—a question likely asked prior to the first Babylonian invasion of Judah in 605. Jeremiah protests his innocence. He has not wished for the catastrophic event (17:16).

The harshness of his prayer for disaster to come on his opponents can be appreciated if his opponents are understood as those opposing God. Jeremiah 17:18, it has been argued, is proportionate destruction (cf. 16:18).

17:19–27. The people are exhorted to observe the Sabbath (Sabbath laws are given in Ex 20:8–11; 23:12; 34:21; Nm 15:32–36). “Watch yourselves” (17:21) is an admonition used in Deuteronomy (Dt 4:9, 15). The instruction is to desist from public trading and from work generally.

Reform and renewal start with specifics. Some have suggested that of the Ten Commandments Jeremiah singled out the fourth because it was the easiest to observe; besides, it was a tangible sign of the covenant (Ex 31:16–17). As with God’s instructions generally, so here, difficulty ensues for those who disregard them; blessing follows those who obey. After two three-month reigns (Jehoahaz, Jehoiachin) the promise of a stable monarchy (17:25–26) would be important. Political stability and religious commitment provide the setting for the good life.

Appropriate sacrifices will be brought from the whole land. Jeremiah 17:26 names the regions: Benjamin, a territory adjoining Judah to the north; the Shephelah, foothills west of Jerusalem; the hill country, the range from Ephraim south; and the Negev, in the desert south. In the gates, the very place of desecration, fiery destruction will begin should the Sabbath not be observed (17:27).

E. A pot marred, a pot smashed (18:1–19:15). Chapters 18 and 19 describe two sign acts. The sign act or symbolic action is in the traditional form: (1) an instruction, (2) a report of compliance, and (3) an interpretation. Both sign acts in these chapters involve clay pots. In the first a marred pot is a prelude to a call to repentance—a call that is defiantly rejected. In the second sign act, a pot is smashed as a visual message about the coming catastrophe upon the city of Jerusalem. God’s sovereignty is evident throughout.

18:1–10. The potter’s equipment consisted of two stone disks placed horizontally and joined by a vertical shaft (18:3–4). The lower would be spun using the feet; the other, at waist level, had on it the clay for the potter’s hand to shape. [Wheel]

Jeremiah 18:7, 9 recalls words from Jeremiah’s call, which occur there, as here, in the context of nations generally (1:10; cf. 24:6).

It is not so much that God offers a second chance but that, just as the potter is in charge and decides what to do when things go other than planned, so God is in charge and at any given moment has the option of choice (18:5–10). In some sense at least, prophetic announcements are conditional. God is not arbitrary; repentance makes a difference.

18:11–17. The principle stated in verses 6–8 is next applied to Judah (18:11–17). Their decision to follow their own stubborn heart is confirmed by their explicit statement (18:12).

God assesses their decision (18:13)—unlike the decision of other nations (2:10–11). The argument in 18:14 is that it is contrary to nature for snow to leave Lebanon. The seriousness of coming disaster is described by responses of others to it: scorn (18:16) is hissing or whistling in unbelief (see the CSB footnote). To show someone one’s face (18:17) is language for blessing and favor.

18:18–23. The decision to follow personal plans puts into effect plans to do away with the prophet (18:18). Priests, the wise, and prophets, along with kings, represent that society’s leaders.

Jeremiah’s prayer (18:19–23) incorporates elements similar to those in his other laments (see 11:18–23; 12:1–4; 15:10–21; 17:14–18). There is personal petition, complaint, and a call for God to bring vengeance. Evil has been paid him for the good he has done—specifically, he has sought the well-being of those now turned against him. The question of 18:20 could also be a question asked by his persecutors, who think of their actions as good.

We are shown an angry prophet. Against families (women, youths, children) Jeremiah would bring famine and sword (18:21). Even more, he prays for God to forestall any atonement for their sins (18:23). Here is a lapse in prophetic intercession. Even acknowledging that Jeremiah leaves the matter in God’s hands, he falls short of Jesus’s response to his enemies: “Father, forgive them” (Lk 23:34). One may, however, in Jeremiah’s response see mirrored how God in justice might deal with those opposing him.

19:1–15. The terrible message of doom is first made vivid to the elders by means of a smashed pot (19:1–13); later the same message is announced to all the people (19:14–15). Egyptians wrote names of enemies on pottery jars and then smashed them, believing that such action magically triggered disaster. [Topheth]

F. Terror on every side (20:1–18). 20:1–6. Here is the first one-on-one announcement of the coming catastrophe. Pashhur might well have been among the religious leaders taken by Jeremiah on a tour to see Topheth (19:1–15). Jeremiah 20:3 catches the emotional dimension of the coming disaster. The name Terror Is on Every Side is a reversal of Pashhur, which, though Egyptian, in Aramaic might mean “Fruitful on Every Side.” Babylon, now named for the first time in the book (20:4), will be Pashhur’s destiny, not because he arrested Jeremiah, but because he collaborated in the big lie of announcing continued safety (8:10–11). In keeping with the principle of corporate personality or social solidarity, Pashhur’s household will share his fate (20:6).

20:7–13. The lament in 20:7–13 follows the classical lament pattern: complaint, statement of confidence, petition, and praise. Jeremiah’s address to God is daring. “Deceived” (20:7) is elsewhere rendered as “seduce” (Ex 22:16) but may here be used in the sense of persuading, though with a sinister purpose (cf. Pr 24:28). God has victimized the prophet. Jeremiah cries out as an innocent sufferer. To shout, “Violence” (20:8) is the equivalent of the modern “Emergency!”

Jeremiah’s personal frustration in dealing with an irresistible urge to speak (20:9) is compounded by external opposition (20:10). His support system has collapsed. His trusted friends mock him with the slogan of his own message, “Terror is on every side!”

The statement of confidence about God as warrior (20:11) harks back to Jeremiah’s call (1:8, 19). God’s vengeance contrasts with the enemy’s vengeance (20:12). Praise within a lament (20:13) is a standard component; one-third of all the psalms are classified as laments, and all but one (Ps 88) contain praise. In contrast to other laments, this one is not followed by a response from God.

20:14–18. The classical statement of cursing in 20:14–18 likely describes another occasion; otherwise its link with verse 13 presents a schizophrenic prophet. Or, this may be not Jeremiah’s curse but a standard outcry made by people caught in calamity. Cursing the day of one’s birth (20:14) stops short of cursing God (cf. Jb 3:2–10). Sodom and Gomorrah, totally destroyed, are the two cities of 20:16 (cf. Gn 19:24–28). The speaker, in his vexation of spirit, would have preferred to be stillborn or unborn (20:17–18). The death wish, if it is Jeremiah’s, arises not only out of personal despair but also out of the shocking public scene.

4. CHALLENGING KINGS AND PROPHETS (21:1–29:32)

The preceding chapters have introduced the message of doom (chaps. 2–10) and the reason for that message (chaps. 11–20). Beginning with this section we are more securely locked into datable historical, though chronologically disarranged, events. We hear of kings: Josiah, Jehoiakim, Jehoiachin, Zedekiah. We meet prophets: Hananiah, Ahab, Zedekiah, Shemaiah. The leaders bear major responsibility for Judah’s evil condition. Prose narrative dominates, which speaks of Jeremiah in the third person.

A. Addressing rulers and governments (21:1–23:8). 21:1–10. The first of two delegations from Zedekiah to Jeremiah is dated to 588 BC. Nebuchadnezzar, the famous ruler of Babylon (605–562), had earlier invaded Judah (597) and had appointed Zedekiah as king. Zedekiah, apparently persuaded by his advisors to invite Egypt’s help, had rebelled (cf. Jr 52:3). Now Nebuchadnezzar was back (21:2).

The delegation wonders whether God might intervene, as he did when Hezekiah was threatened by Sennacherib and the Assyrians (2 Kg 19:35–36). Pashhur (21:1) is not to be identified with the priest of 20:1–6; this Pashhur later calls for Jeremiah’s death (38:1–6). Jeremiah as an intermediary is approached for information.

Jeremiah’s answer is bad news. Judah’s weapons will be turned back on them (21:4), possibly through Babylonian capture or because of confusion during a rapid retreat. Judah faces a God who fights not for them but against them. Jeremiah 21:5 is holy-war language.

The fate of Zedekiah and his officials—death by the sword of Nebuchadnezzar (21:7)—is fulfilled in 52:8–11. Jeremiah’s counsel for the people to surrender peacefully to the Babylonians (also called Chaldeans) brands him a traitor (21:8–10).

21:11–22:9. The passage about God-pleasing government is in two symmetrical parts (21:11–14 and 22:1–9): instruction (21:11–12), announcement (21:13–14), instruction (22:1–3), announcement (22:4–9).

The instruction is first to the royal dynasty generally, almost as if by way of review (21:11–12; cf. Dt 17:18–20; 1 Kg 3:28). Jeremiah walks downhill from the temple to the palace to address a specific ruler of David’s line, possibly Zedekiah (22:1–3). The initial call in either case is for the king to be a guardian of justice, which may be defined as “love in action” or “honorable relations.” Clearly “justice” goes beyond legal court decisions and is expressed in social concern for the oppressed and for the marginal people, those readily exploited or cheated.

The announcement in the first half (21:13–14) assumes a history of failure. God is poised to move against Jerusalem (not named, but inferred from the feminine forms in Hebrew; cf. 21:5). Jerusalem has valleys on three of its sides; the rocky plateau is Mount Zion. “Forest” refers to the pillars in the palace or to the palace itself, called “House of the Forest of Lebanon” (1 Kg 7:2).

The announced promise in the second half (22:4–9) is of good things for the royal house or dynasty and is followed by a warning.

22:10–12. The verdicts about Judah’s kings may at one time have been isolated statements. Or, if Zedekiah is the king to whom 21:11–22:9 is addressed, they may have been spoken for his benefit.

Jehoahaz’s failures are detailed first (22:10–12). The dead king (22:10) is Josiah, Judah’s king for thirty-one years who died in battle at Megiddo in 609 BC, apparently in an attempt to halt the Egyptians. He who has gone away is Shallum (22:11–12), whose regal name was Jehoahaz, the fourth-oldest son of Josiah (1 Ch 3:15). He came to the throne at age twenty-three, in 609 BC, and ruled only three months. Pharaoh Neco of Egypt declared his suzerainty over Judah by taking Jehoahaz captive, first to Riblah, north of Damascus, and then to Egypt, where he died (2 Kg 23:31–34; 2 Ch 36:1–4).

22:13–16. Jeremiah’s sharpest and most extended critique is directed at the despot Jehoiakim, who ruled 609–597 (see 2 Kg 23:34–24:6). Midway through his eleven-year reign he became a vassal of the Babylonians. Jeremiah attacks Jehoiakim’s ostentation and covetousness in connection with a new palace.

A woe statement (22:13), while common in Jeremiah (23:1; 48:1), is more frequent in Isaiah (Is 5:8, 11, 18, 20–21). “Unrighteousness” is lack of inner integrity, and “injustice” is failure to be honorable in transactions. Justice was to be a ruler’s first concern (21:11; 23:5; Mc 3:1–3). Specifically, Jehoiakim cheated his workers out of pay or resorted to forced labor. Because of the heavy tribute to Egypt, he may have been unable to pay (2 Kg 23:35). Large rooms, windows, cedar paneling—a luxury (cf. Hg 1:4)—and red paint signal showiness (22:14). Jehoiakim was obsessed with acquiring wealth and with shedding innocent blood.

Jehoiakim’s insensitivity to the urgency of the times was in contrast with Josiah’s overriding concern to do what was right and just (22:15–16). Concretely this meant acts of compassion and caring for the poor. Knowing (i.e., experiencing) God consists of such caregiving (cf. 9:23).

22:17–23. “Extortion” (22:17), in its verb and noun forms, occurs more than fifty times in the OT. In many contexts the term carries nuances of force or violence, and sometimes misuse of power. In more than half the occurrences, the context also specifies poverty.

People will not hold Jehoiakim, who wants so much to be a somebody, in regard, nor will they express loss at his death or care for his supposed accomplishments, his “majesty” (22:18). The oracle with the catchword “Lebanon” (22:20, 23) is directed in the feminine to Jerusalem.

Casemate wall remains from a royal citadel (seventh century BC) at Ramat Rachel, where Jehoiakim may have built his palace (Jr 22:13–14)

The accusation is that of disobedience. Shepherds are civil rulers; “lovers” refers to Egypt, Assyria, Moab, and the like, who will be driven off by the wind (fulfilled in 597) (22:22).

22:24–30. Jehoiachin, known as (Je)Coniah, was Jehoiakim’s eighteen-year-old son who succeeded him and reigned for three months in 598–597 (2 Kg 24:8–12). The signet ring (22:24) was used to stamp official correspondence. The queen mother was Nehushta (22:26; cf. 2 Kg 24:8). Jeremiah’s prediction was fulfilled in 597 (2 Kg 24:15). The last comment about Jehoiachin is about improved conditions in exile, where he died (Jr 52:31–34).

“Pot” (22:28) is a term for a degraded quality of jar. The address to land is likely a call for a witness (22:29; cf. 6:19). The threefold iteration marks intensity (cf. Is 6:3). Jehoiachin had seven sons (1 Ch 3:17–19), none of whom ruled. Zerubbabel, Jehoiachin’s grandson, returned to Jerusalem to become governor, not king. Since Zedekiah, Judah’s last king, preceded Jehoiachin in death, Jehoiachin in effect marked the end of a 350-year Davidic dynasty (22:30).

23:1–6. The righteous branch is celebrated in 23:1–6. A general woe is spoken to all rulers, known in the ancient world as shepherds (23:1; cf. Ezk 34). God notes and repays officials who have misused their office. The charge “you have scattered” (23:2) refers to the scattering into exile that will be the result of sins such as child sacrifice, which kings condoned and even encouraged. Restoration to the land of those scattered will be a chief theme of the Book of Comfort (Jr 30–33, esp. 30:3; 31:17) and Ezekiel (11:17; 20:42; and 37:21).

“Branch” (23:5) is familiar language in discussion of royal family trees (Is 10:33–11:4) and serves as a messianic title (Is 4:2; Zch 3:8; 6:12). This promise, one of the few messianic promises in Jeremiah, is echoed in 33:15–16. Justice and righteousness will be the trademark of the coming ideal king, as it was to have been of all kings. The name “The LORD Is Our Righteousness” (23:6) memorably embodies God’s concern for justice.

23:7–8. The oracle about a glorious return from exile is elaborated in chapters 30–31. The exodus from Egypt was significant in shaping a people. So will the “new” exodus of the exiles, the descendants of Israel, inaugurate a new era. The return took place in 538 BC and partially fulfilled the oracle, which promised more-spectacular things. It has been noted that a god-sized problem was given a God-sized solution.