Biologists try to understand why we have so many or so few species in one place or another. They ask how patterns in the history of Earth mesh with those in the history of a group of animals and how forces, conditions, and processes result in the diversity of species on Earth. In tracing the evolution of cats, or any animal, biologists are guided by the theory of common decent and evolution through natural selection. They look at the basic body plan and diagnostic characteristics of the cats alive today and trace them back to the first appearance in the fossil record of an animal with these characteristics; it is like starting with the tips of the branches of a tree and working down to the trunk. Periods during which little environmental change occurred in terms of climate, competitors, and predators produced fossils that exhibit little change as well. One kind of change occurs in response to other kinds of change. Over time, whether climates change slowly or abruptly, new habitats emerge as a result. Prey species evolve in their adaptations to exploit these new habitat types. The evolution of their predators is close behind.

The real Age of Mammals began after the extinction of the dinosaurs, about 65 million years ago, although mammals first emerged in the late Triassic more that 208 million years ago. The loss of the dinosaurs opened up ecospaces, or niches, for other creatures to proliferate. The major event triggering this shift was a huge meteorite that slammed into the Earth, probably just off the coast of Yucatán, Mexico. The order Carnivora arose from a miacoid, one of a group of small (1 to 3 kilograms) domestic-cat-sized arboreal carnivorans that first appeared in the forests of the Northern Hemisphere 60 to 80 million years ago. These early carnivorans had evolved a trait that was to give the group a flexible advantage in the drama of life that has been playing out ever since. They had evolved the key tool (and the diagnostic character) of the order Carnivora: a single pair of cutting teeth called carnassials, which are the upper fourth premolars and the lower first molars. With the enhancement of the cutting or the crushing aspect of these teeth, different groups of the Carnivora have become either meat-eating specialists, such as the cats and weasels, or plant-eating specialists, such as the red panda and giant panda, or a little of both, which describes most of the Carnivora species.

By about 40 million years ago, the first Carnivora species had divided into two sister groups. The catlike Feliformia eventually came to include the cats, hyenas, civets, mongooses, and a now-extinct catlike group called the nimravids. The second group was the bearlike Caniformia, which eventually came to include the bears, raccoons, weasels, dogs, skunks, badgers, sea lions, seals, walruses, and a now-extinct group called the bear dogs (Amphiconidae). By 37 million years ago, the civet-mongoose group, or clades, had diverged in their specializations from the cat-hyena group. By 35 million years ago, the cats and hyenas had separated into their respective clades.

The dawn cat, or Proailurus, was bobcat-sized, and its morphology suggests it was mostly arboreal. Fossils of this species are rare, but it or a loosely related group of species lived in Europe through the Oligocene (about 33 to 23 million years ago) and on into the mid-Miocene (about 17 million years ago). Cat fossils are very rare or absent in the early to mid-Miocene (about 23 to 17 million years ago), so biologists call this the cat gap. The cat ecospace, that of a stalking, pure meat-eater, was filled in North America by catlike forms of canids, bear dogs, and bears, which had teeth specialized for pure meat-eating. In Eurasia, canids, bear dogs, and hyenas evolved to use the cat ecospace. Fossils of Pseudoaluria, related to but distinct from the dawn cat, first appeared at widely separate sites in Europe, China, and North Africa during the early Miocene. They abruptly appear in fossil beds of the mid-Miocene in the Middle East, Mongolia, and India. This genus entered North America by 16 to 17 million years ago. There was a mid-Miocene decline in the catlike Nimravidae, the “old cats,” or paleofelids. For the remainder of the Miocene, there was an increase in true cat fossils—members of the Felidae, the “new cats,” or neofelids—and a decrease in the fossils of catlike forms from the other Carnivora families, presumably because true cats were better at being catlike and outcompeted the catlike forms that had evolved in the other Carnivora families.

During the Miocene, the Earth’s climate changed, becoming drier and more seasonal. Shrub-grassland steppe, habitat like that of much of the intermontane West of the United States, and open grasslands, like those of the Great Plains or the Serengeti, first appeared, as did grazing mammals adapted to these new habitats, greatly changing the nature of potential prey. A steadily increasing number of cat species evolved in response to these changes. A continuum of habitats from forest to forest-edge, to savanna, to open expanses of grassland and shrub created conditions in which different populations of a species evolved specializations for each different habitat, but there was still genetic interchange among populations. Prey adapted to these new conditions as well. Eventually, however, habitats became more distinct and diverse, resulting in the isolation of some peripheral populations of both predator and prey. With contact between populations broken, new species emerged.

The evolutionary history of successful carnivores is written in their attempts to overcome diverse prey animals, just as that of prey is written in their attempts to escape predation. In the forest, the herbivorous leaf-eating and fruit-eating species that are potential prey for cats do not have access to the majority of the plant biomass because it consists of tree trunks. With the evolution and expansion of grasslands and shrub, a whole new food source appeared for animals that were potential prey for cats. Ungulates and rodents emerged from the forest and evolved to eat the grasses and seeds of grasslands (see Why Don’t Cats Eat Fruits and Vegetables?). Larger size and speed evolved among prey to enable them to escape predators in open environments. Predators evolved larger, faster body types in response. Among the cats, lions, cheetahs, pumas, sand cats, black-footed cats, and others hunt in open country, although they have greater hunting success where they can use some cover to stalk prey. Other cats, such as tigers and leopards, live at the forest edge but often hunt in adjacent open areas. Still others, such as margays and clouded leopards, are confined to forest.

Using a molecular genetic phylogenetic reconstruction—that is, analyzing genes to determine evolutionary history—Stephen O’Brien and his team at the National Cancer Institute’s Laboratory of Genomic Diversity have traced the echoes of the divergence of the various groups, or lineages, of cats we know today back more than 10 million years to the late Miocene. This was a very dramatic period in the history of the carnivores. A major “turnover” occurred during which 60 to 70 percent of the Eurasian Carnivora genera and 70 to 80 percent of the North American ones became extinct and were replaced with large felids, canids, and bone-cracking hyenas. The last catlike nimravids vanished at this time. This upheaval is correlated with significant climate change that resulted in the desiccation of the Mediterranean Sea and the spread of seasonally arid grasslands in place of more moist woodlands. Most of the ancestors of the living cats first appeared in the Pliocene (5 to 1.8 million years ago) and the Pleistocene (1.8 million years ago to about 10,000 years ago). The relationships and the origins of the eight cat lineages are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Several genetic analyses were combined to produce this tree, which reflects current understanding of the evolutionary relationships among the species in the family Felidae. The species within a lineage share a common ancestor, but in the Panthera Lineage, for example, clouded leopards diverged early from the ancestor of the other five cats in this lineage. Similarly, the tree shows that the Leopardus (Ocelot) Lineage diverged very early on from the rest of the cat lineages. Species marked with an asterisk did not cluster in any lineage consistently. (Iriomote cats were not included in the analysis that produced this tree, but they most likely fall into the Leopard Cat Lineage. In the absence of genetic analysis, the placement of the Iberian lynx within the Lynx Lineage was inferred on the basis of morphology.) (Adapted from Johnson, Dratch, et al. 2001)

The evolution of species within a region depends on the geographical configuration of the region, spatial arrangements of habitats, and the ability of the species to disperse into and out of that region. The formation of a new species, or the process of speciation, is the full sequence of events leading to the splitting of one population of organisms into two or more populations that become reproductively isolated from one another. New species can originate from geographically isolated portions of the parental species through their acquisition of an effective isolating mechanism. This is called allopatric, or geographical, speciation. There are two forms of allopatric speciation. The first form, called dichopatric speciation, involves the origin of a new species through the division of a parental species by geographical, vegetational, or other extrinsic barriers.

The flooding of the Bering Strait, between Asia and Alaska, at the end of the Pleistocene probably separated populations of a single species of lynx and created the Canadian and Eurasian lynxes. Advancing glaciers in the Pleistocene separated widespread populations into isolated ice-free refuges, and during arid periods of the same epoch, the large expanses of tropical rain forest were reduced to a number of smaller rain forest refuges surrounded by arid, treeless areas. We don’t know how these may have influenced the number of cat species we see today, but we strongly suspect they did, especially in today’s tropical areas in South America, Africa, and Southeast Asia. Retreating, melting glaciers resulted in rising sea levels, which created islands. This is probably what created the Bay Cat Lineage, with the bay cat currently restricted to the island of Borneo and its close relative, the Asian golden cat, living in much of the rest of tropical Southeast Asia.

The second form of allopatric speciation, called peripatric speciation, involves the origin of a new species through the modification of a peripherally isolated founder population. The founders may be just a few individuals or even single pregnant female. Some of these founder populations go extinct; some may eventually merge again with the parent species; some become full species. This is called species budding. A founder population may find itself in an entirely new environment or in a changing environment that offers the ideal situation for evolutionary departures into new niches and adaptive zones. The evolution of lions, cheetahs, and snow leopards may be examples, and so are the members of the Caracal Lineage. The African golden cat, a member of this lineage, is restricted to the rain forest, and the closely related caracal lives in the drier portions of Africa and south Asia, but not in deserts.

Large gaps occur between populations of many cat species, such as fishing cats, leopard cats, and rusty-spotted cats, perhaps because the species became extinct in parts of a once-continuous range. It is also possible for members of a species to establish founder populations far away from the original population after dispersing across unsuitable terrain such as water, mountains, or inhospitable habitat. This is called vicariance speciation. These widely dispersed populations may eventually become full species themselves.

Sympatric speciation, or the splitting of a single breeding population into more than one species without geographical isolation, is not known for any birds or mammals.

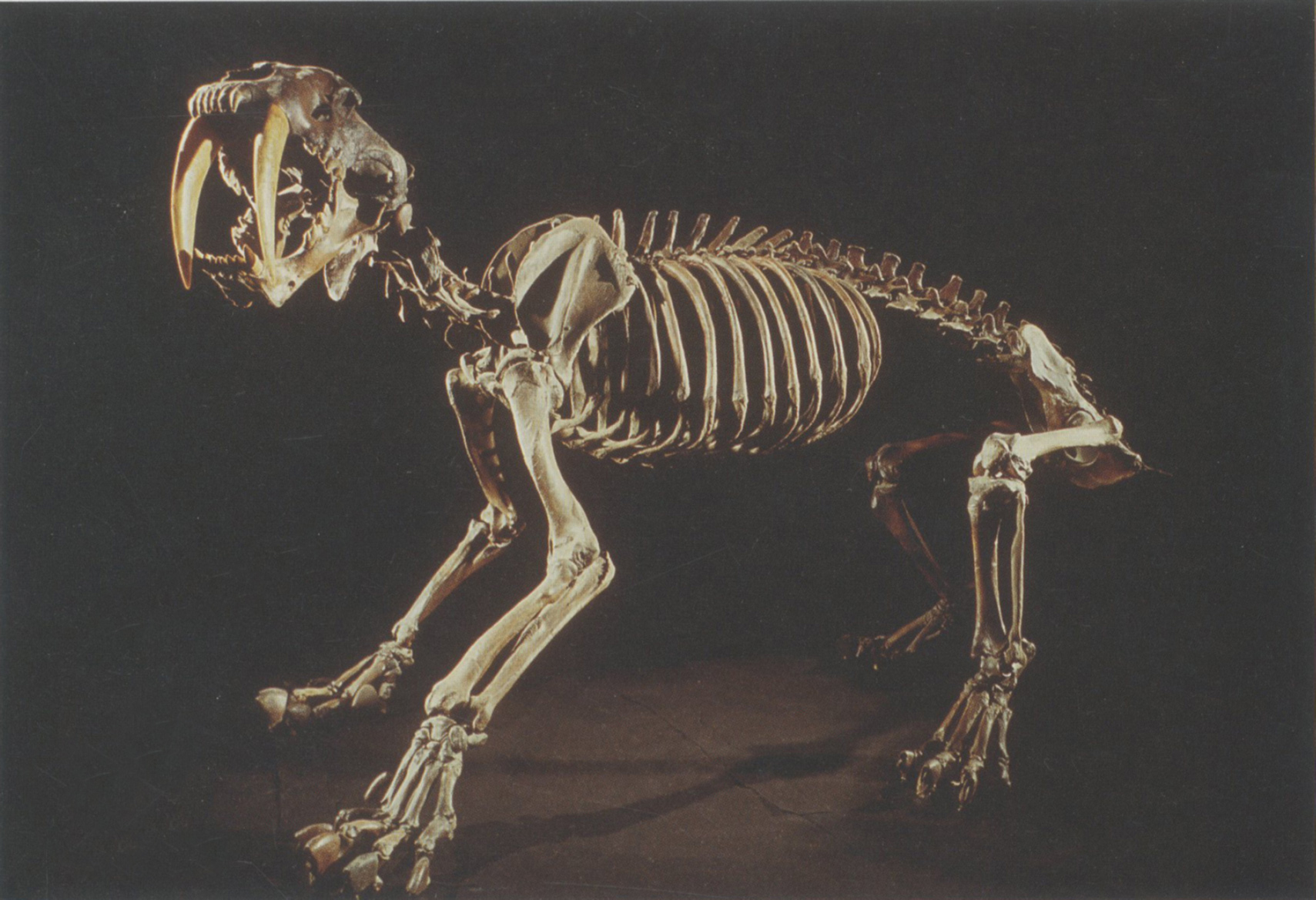

Growing up, we were transfixed by images of saber-toothed “tigers” that appeared in books and magazines, such as the wonderful C. R. Knight painting of a larger-than-lion-sized Smilodon fatalis lording over its domain. This great saber-toothed cat is known from many fossils of animals trapped in the La Brea tar pits in what is now Los Angeles, although the Smilodon genus was widespread in both North and South America and became extinct only about 10,000 years ago. The term saber-toothed comes from the shape of their upper canines, which resembled the long curved sabers brandished by mounted cavalry. Tiger referred to their large size but is misleading because it gives the impression that this species had an ancestral relationship to the tiger we know today, though it did not. Most saber-toothed cats were smaller than tigers. Paleontologists call tigers conical-toothed cats, and all cats living today are conical-toothed. The upper and lower canines are about equal in size, are shaped like cones, and are not serrated. When biting down, the upper canines fit behind the lower canines. Conical-toothed cats use their canines to bite into the throat or neck of their prey to kill them by suffocation, or by crushing, or by separating the vertebrae to damage the spinal column. Saber teeth come in two types: scimitar teeth and dirk teeth, both elongated upper canines. Dirk-toothed saber-toothed cats had extremely long, narrow upper canines with finely serrated edges. Smilodon was a dirk-toothed cat. Scimitar teeth are shorter, broader, and have coarse serrations.

The gape of a lion’s wide-open mouth is about 65 degrees. That of Smilodon was about 100 degrees, and the gape reached 115 degrees in a scimitar-toothed species such as Homotherium serum, many fossils of which have been found in deposits in Texas and Eurasia. Smilodon was a powerful predator that probably ambushed prey. Because its saber teeth were relatively vulnerable to breakage, it probably stabbed and sliced its prey in places where there was little risk of hitting bone, such as the esophagus-jugular area of the neck, as paleontologist Larry Martin (1980) reasoned, or the stomach area, as other paleontologists have argued. The saber-toothed cat also must have been a careful feeder and avoided any contact with bone that might damage or fracture its highly specialized killing teeth. It probably left behind substantial portions of the carcasses of the prey it killed and, thus, provided food for a whole guild of scavengers. The scimitar-toothed cat Homotherium had longer front legs and probably pursued prey for longer distances than the squat and powerful dirk-toothed Smilodon.

The saber-tooth adaptation was found in cats of various sizes, and they have a very broad distribution. Fossil saber-toothed cats have been found in North and South America, through Eurasia, and into Africa. Moreover, this adaptation has not been restricted to cats; the saber-tooth specialization appeared independently at least four times in examples of convergent or parallel evolution. Many of the members of the extinct Carnivora family Nimravidae had long canines, as did large marsupial carnivores that once lived in South America. The marsupial saber-toothed carnivore Thylacosmilus, from South America, dates from the Pliocene, 5 to 1.8 million years ago. It had saberlike upper canines parallel to descending bony flanges on the lower jaw; it also had short, powerful limbs, suggesting it had a stalking-ambush hunting style. The Nimravidae were once thought to be the direct ancestors of the Felidae, but this is no longer considered to be the case. Yet, the Felidae and the Nimravidae both included saber-toothed species. The extinct creodonts—the first large carnivores to emerge after the demise of the dinosaurs 65 million years ago—also had species with saber teeth. The creodonts were a sister taxon to the miacoids, the group that gave rise to the Carnivora.

How are the saber-toothed cats related to the cats we know today? The molecular phylogeny was worked out by painstakingly harvesting ancient DNA from the fossil remains of the Smilodon from La Brea and comparing this with DNA from living species. This remarkable work was done by Dianne Janczewski in Stephen O’Brien’s lab (Janczewski et al. 1992). The work confirmed that the most recent saber-toothed cats were clearly members of the modern family Felidae, not the Nimravidae. What remains unclear is just how the modern cats and the recent saber-toothed cats, as exemplified by Smilodon, are related to one another. The saber-toothed cats have traditionally been included in their own subfamily, the Machairodontinae, within the family Felidae, and the conical-toothed cats in their own subfamilies, the Felinae and Pantherinae. These biologists propose instead that the old subfamily designations be dropped because all the cats are more closely related than we once thought.

For the last 40 million years or so, there has always been a saber-toothed mammalian carnivore living some place on Earth. Through much of their history, humans lived cheek by jowl with great saber-toothed cats, until the last saber-toothed cats, Smilodon, became extinct. We are now in what paleontologist Blaire Van Valkenburgh (1991) calls a unique saber-toothless period. Clouded leopards have very large canines for their body size, but these are of the conical-tooth type and thus different from Smilodon and other extinct saber-toothed cats.

Smilodon was just one of many cats with saber teeth that once lived in North and South America, Eurasia, and Africa before the last of these species disappeared at the end of the Pleistocene. Smilodon has recently been shown to belong to the modern family Felidae. (Photo by Chip Clark)

The largest cat we have ever seen was a wild male Bengal tiger in Nepal. Male 105 he was called, because he was the fifth tiger captured in the Smithsonian-Nepal Tiger Ecology Project in 1975. He was massive. His muscles rippled, and he did not seem to have an ounce of fat. He weighed more than 250 kilograms; how much more we don’t know, because the scales we had registered no higher than that. Reports exist of tigers weighing more than 300 kilograms, but it is likely that these weights were estimated and perhaps exaggerated. Other reports of heavier tigers have involved some very fat zoo animals.

However, some of the largest cat species in existence today were once larger, and other very large cats are now extinct. The fossil remains of American lions that were trapped in the La Brea tar pits more that 10,000 years ago show that those animals were huge. Some were estimated to have weighed 344 to 523 kilograms, more than twice the mass of a modern African lion (180 kilograms) or a very large tiger (250 kilograms). The great saber-toothed cat Smilodon, whose fossil remains were trapped in the tar along with the American lion, is estimated to have weighed between 347 and 442 kilograms. Another saber-toothed cat, Homotherium serum, is estimated to have weighed between 146 and 231 kilograms, a close match for today’s African lion or Asian tiger.

Why were the big cats bigger in the past? Paleontologists speculate that their size allowed these very big cats to kill very large prey, such as giant bison, horses, mylodont sloths, camels, mastodons, mammoths, and tapirs, the fossils of which were also found in the same tar pits with their giant predators. This whole assemblage of giant mammals, predator and prey, is now extinct. Scientists argue heatedly about whether they were killed off by the first wave of humans into North America, suffered because the climate became drier and harsher, or some of both.

Lions once did range in North America, and they may have lived in South America too. In Alaska, fossils have been found of what may be tigers, but some biologists believe these fossils come from lions. Paleontologists are challenged by the difficulty of telling the big cats apart without their coats. Some biologists say it is impossible to tell the fossilized skulls of lions and tigers apart or even to distinguish them from leopards and jaguars. Size offers some clues: the largest leopard skulls today are considerably smaller than the smallest lion and tiger skulls, but this doesn’t help separate lions and tigers. Lions, however, have longer legs than tigers relative to their body size, and where more complete fossilized skeletal material exists, the ratio of limb-bone length to skull size helps to separate the two species.

Cats occupy terrestrial habitats virtually the world over. Only Australia, Antarctica, and islands that have never had a land bridge to a continent with a native cat species lack native wild cats. Because humans have left domestic cats wherever they have gone, feral domestic cats now live nearly everywhere. The general distribution and diversity of cat species in selected areas is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5. The comparative distribution of wild cats. In mapping the Earth’s biodiversity, ecologists have described 14 biomes and 8 biogeographic realms. The cat species that now live at selected sites within these realms and biomes (or have been only recently extirpated in them, designated with E) are shown. (Biome map from the World Wildlife Fund–US)

The center of felid diversity and abundance is Asia, home to 22 species, with 10 species living in Southeast Asia alone and 10 species living in the mountains of China on the eastern side of the Tibetan plateau. Africa has 9 species. South America has 12 species. Today Europe has only 3 species (Iberian and Eurasian lynxes and wildcats), but lions lived in southern Europe in historical times. North America north of Mexico now has 4 species (puma, bobcat, Canada lynx, and a small population of ocelots in Texas). Within historical times, the jaguar and jaguarundi were also part of the North American assemblage, but today they are only occasional visitors.

A few cat species have extremely wide geographical distributions. Leopards inhabit most of Asia and Africa, and pumas much of North, Central, and South America. The Eurasian lynx lives across northern Europe and Asia. Wildcats live in Europe, Africa, and Asia. The leopard cat’s range stretches from the Indonesian islands through Southeast Asia, into part of India in the south, and into the Russian Far East in the north.

Other species have very restricted ranges. Bay cats live only on the island of Borneo; black-footed cats live only at the southern end of Africa; kodkod live in the southern Andes; and the Andean mountain cat lives only in the central Andes. Iberian lynx live only on the Iberian Peninsula; the African golden cat is restricted to African rain forest areas.

The distributions of the cats that are habitat specialists are easily read from maps of vegetation types and landforms. The African golden cat lives in Africa’s wet tropical forests; its closest relative, the caracal, is found in the remaining areas of Africa that are neither wet tropical forest nor true desert, and it occupies similar habitats into Asia Minor and south Asia. The sand cat lives in the sand deserts of Africa and Asia Minor to Pakistan. The snow leopard lives in the mountains of central Asia. The Pallas’ cat lives in the parts of central Asia that are dry and usually cold, but it does not live where there is any appreciable snow accumulation in winter. The Asian golden cat, marbled cat, and clouded leopard are closely associated with rain forest but also with the moist forests in the northern and western portions of their range in Asia. The bay cat and flat-headed cat are cats of the Southeast Asian rain forest. The oncilla and margay are tropical wet-forest cats of South and Central America. Canada lynx live in the boreal (northern) forest of North America and are tied to the distribution of their primary prey, snowshoe hares. The Eurasian lynx occurs across Eurasia, where it inhabits the boreal forest but also the margins of the steppe and the mountains. Hares are a major part of its diet, but it also feeds on small ungulates.

Some species that are widespread and even some with smaller geographical distributions have disjointed ranges, or vicariant distributions, that are the manifestations of past climatic and geologic changes. Today, the serval is confined to sub-Saharan Africa, but a North African population, separated by the Sahara, went extinct. The sand cat’s range has been divided into at least five fragments of sand desert stretching from the western Sahara to Pakistan. We don’t know why the populations have become fragmented. The leopard cat has a wide distribution, as we have seen. But where its range extends west along the foothills of the Himalayas, it suddenly stops and mysteriously does not occur through most of the rest of India except in the southwest, on the Malabar Coast. Fishing cats also have a disrupted distribution. They occur on Java and Sumatra but not on the Malay Peninsula or Borneo, then appear again in Southeast Asia and extend along the foothills of the Himalayas. They, too, are mysteriously absent through much of India except in the southwest, on the Malabar Coast. They are also found on the island of Sri Lanka. The westernmost population once occurred along the Indus River in Pakistan but is now believed to be extinct there.

Some species are undergoing massive range collapse. Lions now live only in sub-Saharan Africa, except for a small relict population in India’s Gir Forest, but 12,000 years ago they were found at virtually every corner of the Earth, occupying the Americas, all of Europe, the Middle East, northern Asia to Siberia, and southern Asia to India and Sri Lanka. Cheetahs are also now found mostly south of the Sahara in Africa except for relict populations of a few tens of individuals in the central Sahara and in Iran. Formerly they had nearly a continuous distribution in open habitats throughout Africa, Asia Minor, the Middle East, and southern Asia, including the Indian subcontinent. The caracal’s distribution once nearly mirrored that of the cheetah but is now limited to specialized habitat within its former range. In historical times, tigers lived across 70 degrees of latitude and 100 degrees of longitude, from the Russian Far East to the south through Indochina, the Indian subcontinent, and into the Indus Valley. Apart from this primary distribution, tigers lived adjacent to the Caspian Sea and on the Indonesia islands of Sumatra, Java, and Bali. Now they are confined to about 150 isolated patches scattered over this region, and those that lived around the Caspian Sea and on the islands of Bali and Java are extinct. On the other hand, the puma, which had been extirpated from all but the most remote mountain systems in the western United States, today is expanding into mountain ranges where it has not been seen for 100 years or more.

Conservation biologist Michael Soulé has pointed out, “Diversity and rarity are synonyms for ‘everything’ in ecology” (1986, 117). Ecologists who can explain and predict patterns of diversity and rarity in landscapes or regions understand one of the most fundamental issues in biology. Biologists recognize different types of rarity. An animal may be called rare because it occurs only in one particular small area, or because it is restricted to one of a few specialized habitats, or because it is always found in small numbers across its range.

In 1992, scientists saw a live bay cat for the first time ever; previously it was known only from 12 museum specimens. Since then, two have been photographed by camera traps. The bay cat, found only in the rain forest on the island of Borneo, is the rarest of the living cats. “Bay” refers to this cat’s chestnut-colored fur, not its habitat.

The rarest cat in the world is probably the bay cat, which lives both at a very low density and only on the island of Borneo, where it is apparently restricted to rain forest. The bay cat is known from only a few museum specimens and a very few individuals that have been captured and photographed. A camera-trap photo of a bay cat was taken in 2002 and another one in 2003. No individuals are living in zoos. Biologists believe this cat has always been very rare; they were not encountered during night forays into the field with spotlights except in one area of Sarawak (part of Borneo).

Just across the way, on the island of Sumatra, biologists regularly see and camera-trap the bay cat’s close relative, the Asian golden cat. John has seen many tracks of Asian golden cats while walking along logging roads in the Sumatran rain forest.

The Iriomote cat is restricted to the small Japanese island of Iriomote, near Taiwan, where fewer than 100 occur. It is very closely related to the leopard cat, which is much more common and widely dispersed in Asia. The Iriomote cat eats almost anything it can catch and is not a strict habitat specialist.

The tiny rusty-spotted cat is called rare and has a patchy geographic range that extends from Sri Lanka to Kashmir, where there is only a single old record of its occurrence. Biologists didn’t know it lived in the tropical dry forest of western India until A. J. T. Johnsingh photographed one in 1989. Subsequent searches resulted in more photographs of this little cat in and outside the Gir Forest in southern Gujarat. In southern India, villagers showed biologists where rusty-spotted cats were living in abandoned houses in thickly populated areas, distant from any forest thought to be their habitat. This cat may be more common than we appreciate.

The Andean mountain cat is also a very rare cat, known only from 14 museum specimens and three published observations as well as from some recent photographs of a few individuals. This cat is thought to have been much more abundant until a primary prey species, the chinchilla, was decimated by the fur trade.

Closely related groups of cats are called lineages, or clades, as shown in Figure 4. Relationships are determined by looking at molecular similarities of the genes and chromosomes of the various species. Using these methods, biologists have been able to resolve the cat lineages back to about 10 million years ago. Ancestors of some of the cats diverged before this time, and it is not certain how they fit into the currently recognized lineages. Despite this uncertainty, these cats are included with some of the lineages we describe below rather than being treated separately. Figure 4 traces the ancestors of today’s cat species, but we cannot assume that the cats we know today are the same as their ancestors. Also, probably many other budding species arose but did not survive. There are many fossils of long-extinct cats, but most speciation events will never be known. All the cats we know today are the result of one long evolutionary process. In the formal classification of the living cats, the Panthera Lineage is included in the subfamily Pantherinae, and all the other lineages are in the subfamily Felinae, but some specialists think these distinctions are not correct.

Often thought of as the archetypical big cats, the members of the Panthera Lineage vary markedly in weight. Lions (Panthera leo) and tigers (P. tigris) are extremely large, weighing more than 80 kilograms and up to 200 kilograms for the largest lions today and 250 to 300 kilograms for the largest tigers. A few of the very largest jaguars (P. onca) weigh as much as 100 kilograms. However, most jaguars, as well as leopards (P. pardus) and snow leopards (Uncia uncia), are medium-sized cats, weighing between 20 and 80 kilograms. The largest snow leopards are 50 kilograms; the largest leopards are 70 kilograms. While all the large cats are terrestrial hunters, the clouded leopard (Neofelis nebulosa), the smallest big cat, is also adapted for hunting in trees. Biologists say that the clouded leopard has a small cat body and a large cat head, with the longest canines of any cat relative to body size. Coat colors in this lineage match habitat, as they do in all the cats. Living in dry, open country, lions are tawny in color with a striking furry, dark tail tip. The forest-living tiger has black stripes on a reddish-orange background. The jaguar and leopard, also forest-living, have spots and rosettes; the jaguar has a central spot in its rosettes, and the leopard does not. The alpine snow leopard has longer, lightly spotted, smoky-gray fur with countershading. The forest-living clouded leopard has a blotched, countershaded coat.

The marbled cat (Pardofelis marmorata) is found only in the rain forests of Southeast Asia and diverged from all the other cats more than 10 million years ago. Molecular biologists are uncertain of its affiliation with any of the cat lineages, but some features suggest that it may be most closely associated with the Panthera Lineage, and with the tiger in particular. Marbled cats, thought to be arboreal, have never been studied, but they have been camera-trapped on the ground. They are extremely small, weighing from 2 to 5 kilograms. The marbled cat has thick, soft, spotted fur that varies from dark gray-brown, to yellowish-gray, to red-brown. These cats have large feet for their size and long bushy tails.

The clouded leopard’s ancestor diverged from the rest of the lineage about 5 million years ago, at the beginning of the Pliocene. Molecular biologists tell us that the rest of the cats in this lineage diverged from one another in the Pleistocene, 1.8 million years ago, and more recently. However, paleontologists date some of the fossils back to the mid-Pliocene, about 3 million years ago or so, but because it is very difficult to tell species apart on the basis of skull characteristics, it’s hard to say whether a given fossil is a very large leopard or a small tiger or whether it is a very large jaguar or a small lion (see Did Lions and Tigers Once Live in North America?).

Tigers live in forest and lush tall grassland and reach their greatest density at the edges between forest and grassland. The earliest fossils thought to be tigers appeared almost simultaneously about 2 million years ago in northern China and Java. However, it’s not clear whether these were very small tigers, smaller than any we know today, or leopards that are larger than any we know today. By the mid-Pleistocene, the tiger had a wide Asian distribution, including China, Java, and Sumatra. The first appearances of the tiger in the Russian Far East and India occurred later. Fossil tigers exist from Japan in the late Pleistocene. Traditionally the tigers were divided into eight subspecies: Javan (Panthera tigris sondaica), Bali (P. t. balica), Sumatran (P. t. sumatrae), Indo-Chinese (P. t. corbetti), South China (P. t. amoyensis), Amur (Siberian) (P. t. altaica), Bengal (P. t. tigris), and Caspian (P. t. virgata). The Javan, Bali, and Caspian are extinct. The most recent genetic analysis indicates that the Amur tiger, the Sumatran tiger, and the tiger of the Malay Peninsula (formerly included as part of the Indo-Chinese subspecies) are actually distinct enough to deserve subspecies categorization (at least), and the remaining Asian tigers are lumped into a fourth subspecies.

Lions live in open plains or relatively open woodlands. They originally had the largest geographical distribution of any cat. The first fossils thought to be those of lions are from Tanzania 3.5 million years ago. Once the lion adapted to living in open country, it dispersed from Africa into Eurasia and crossed the Bering land bridge into North America, where it became widespread. However, the American lion disappeared about 10,000 years ago. Fossils thought to be those of lions have been found as far south as Peru, but some paleontologists now consider those fossils and others from South America to be very large jaguars. Except for one relict population of about 300 individuals that live in the Gir Forest of India, the once great geographical range of lions has shrunk to sub-Saharan Africa. Even within their present range, lions live in highly fragmented populations and are frequently killed outside protected areas.

Brian Kurten and Elaine Anderson (1980) have suggested that the New World jaguar is the same species as one known from fossils found in Eurasia of a cat that is now extinct. They suggest it crossed into North America about 800,000 years ago. These early jaguars were about 20 percent larger than the largest ones living today. There are jaguar fossils from many sites in North America from the Pleistocene, 1.8 million to about 10,000 years ago, when, like the lion and the saber-toothed cats, the North American jaguar went extinct. Today’s jaguars recolonized Central and North America comparatively recently from refugia in northern South America.

The earliest fossils thought to be those of leopards are from Africa in the mid-Pliocene, 3.5 million years ago. Subsequently, the leopard dispersed through Eurasia. As many as 27 subspecies of leopards have been recognized, but genetic analysis suggests that only 9 are valid, including African, Javan, Sri Lankan, Amur (Siberian), India, Asia Minor, south Asia, Southeast Asia, and east Asia south of Beijing. The first snow leopard fossils are from Pakistan from more than 1 million years ago.

Both male and female lions live in social groups composed of close relatives, an adaptation for living in open country, where other lions are abundant and dangerous competitors. Lions kill medium-sized and large open-country ungulates, such as wildebeests and zebras. The other members of this lineage live in solitary social systems. The snow leopard is a specialized predator of goats and sheep through the rugged mountain ranges of central Asia. Leopards live in habitat as diverse as the Kalahari Desert, dry and wet forests, savannas, and woodlands, where they kill medium-sized ungulates and primates, supplemented with smaller mammals and birds. The clouded leopard is an enigma to biologists, because in captivity, unless young cats are reared together from before the age of 6 months, a male nearly always kills a female when they are placed together to mate. They prey on terrestrial species such as muntjac and small deer as well as tree-living monkeys and apes. Tigers are specialized predators of large deer and pigs and live in mangrove forests, rain forests, tropical wet savannas, and cold temperate forests. The jaguar lives in moist savannas and rain forest and kills deer, peccaries, and also caiman and large terrestrial and aquatic turtles.

The four species of lynx are the foremost predators of hares and rabbits. On the basis of fossils, we now believe the Issoire lynx, more robust than today’s lynxes, originated 4 million years ago in Africa, during the early Pliocene, and is thought to be the original lynx. The Pliocene (5 to 1.8 million years ago) was a period of glacial expansion and retreat, with a colder and drier seasonal climate than in previous periods, perhaps selecting for a lynxlike cat. But today no lynxes remain in Africa; this lineage is found only in Eurasia and North America. Pleistocene lynx fossils have come from many sites in Europe, Asia, and North America. Molecular genetic analysis shows that the North American bobcat (Lynx rufus) is the oldest branch of the radiation, followed in age by the Iberian lynx (L. pardinus). The Canada and Eurasian lynxes (L. canadensis and L. lynx) have been separated for about 3 million years, when rising sea levels submerged the Bering land bridge between Asia and North America. Naturally occurring hybrids of Canada lynx and bobcats have been reported.

All the lynxes are spotted and have soft hair, face ruffs, and black tassels on their ears. The Iberian lynx, Canada lynx, and bobcat are small (5 to 20 kilograms); most of the Eurasian lynx are medium-sized cats, weighing up to 40 kilograms. Lynxes are solitary, terrestrial hunters mostly specializing in rabbits and hares, so their evolution should correspond to the evolution of the lagomorphs, but biologists remain uncertain about the evolutionary history of lagomorphs. Rabbits and hares are thought to have last had a common ancestor about 15 million years ago. Today’s hare species, such as snowshoe hares, jackrabbits, and European hares, are all placed in a single genus, Lepus, and can be traced back to the late Pleistocene. Some rabbits may have more ancient roots. In North America, the typical rabbit belongs to the cottontail genus, Sylvilagus; in Europe, there is one species—the European rabbit. (A third group of lagomorphs, the small pikas, aren’t important in the lives of lynxes but are for the Pallas’ cat.)

The Iberian lynx is a specialized predator of the European rabbit, which was originally from the Mediterranean region but has since been widely introduced elsewhere as well as domesticated by man. The Iberian lynx must have adequate populations of European rabbits to live (see What Are the Most Endangered Cats?). Cottontails and bobcats are closely matched in their distributions and habitats, although cottontails occur in the northern Neotropics, and bobcats do not. Where rabbits are few, bobcats live on a diet of rodents and birds. They are also significant predators of white-tailed deer in some areas.

Across the boreal forests of North America and Eurasia, the Canada lynx and Eurasian lynx hunt hares, and Canada lynx populations follow the cyclical waxing and waning of hare numbers (see How Do Cat Numbers Affect Prey Numbers and Vice Versa?). These northern lynxes are forest hunters and don’t hunt hares that live in the open tundra. In Newfoundland and some other areas, Canada lynx eat caribou calves on the calving grounds and grouse and red squirrels when they find them, but their fortune is tied to the snowshoe hare. Both hares and lynxes have large feet, which are adaptations for moving easily through snow. In addition to hares, the larger Eurasian lynx hunts roe deer, red deer, and even wild pigs. In some areas, these ungulates are the mainstay of the lynx diet year around.

In the Pliocene in Southeast Asia, less than 5 million years ago, the flat-headed cat (Prionailurus planiceps) diverged from the ancestor of the leopard cat (P. bengalensis) and the fishing cat (P. viverrinus). Then the ancestors of the fishing cat and the leopard cat diverged, and most recently the leopard cat and the Iriomote cat (P. iriomotensis) diverged. The Iriomote cat lives only on the island of Iriomote (see What Are the Rarest Cats?). The rusty-spotted cat (P. rubiginosus) diverged more than 10 million years ago, and molecular biologists are not certain how it is related to this or any of the other lineages, although biologists who base their work on morphology place it in the same genus as the others of the Leopard Cat Lineage.

The cats of this lineage are all spotted, with uniquely and beautifully marked faces. Their background coat is dark to light gray. The leopard cat and Iriomote cat have dense spotting on their coats; the others are less densely spotted. The flat-headed cat lives in tropical rain forest and also seems to do well where the rain forest has been converted to oil palms. The fishing cat is a cat of Southeast Asia, with separate populations in south India and Sri Lanka. It lives near water in rain forest and in moist forests. Recently John and his associates camera-trapped fishing cats living in Sri Lankan cities (Seidensticker 2003). The leopard cat is widespread in vegetation ranging from rain forest to dry thickets and woodlands in south and Southeast Asia, all the way into the temperate forests of the Russian Far East. The fishing cat, Iriomote cat, flat-headed cat, and leopard cat are primarily terrestrial hunters; the leopard cat, however, also can be a semi-arboreal hunter in some areas. The rusty-spotted cat, flat-headed cat, and the leopard cat living on the island of Borneo are extremely small, less than 3 kilograms in weight. Leopard cats in the Russian Far East may be as large as 10 kilograms but in most other parts of the range are less than 5 kilograms. Fishing cats weigh as much as 15 kilograms, but females of this species are much smaller than males.

The fishing cat and flat-headed cat eat fish and are closely associated with water; the leopard cat and Iriomote cat also are reported to fish. They all eat small mammals and supplement their diet with amphibians, reptiles, and birds. In addition, leopard cats and Iriomote cats eat insects, and fishing cats are reported to eat carrion. Rusty-spotted cats eat small mammals, amphibians, reptiles, and insects.

The serval (Leptailurus serval) and the caracal (Caracal caracal) look as though they could be closely related, but molecular biologists have determined that they probably diverged more than 10 million years ago. The divergence between caracals and African golden cats (Profelis aurata is thought to have occurred in the late Miocene, more than 5 million years ago. Caracals and servals are elegant, relatively small cats with long legs. Caracals weigh from 8 to 20 kilograms; servals weigh about 10 kilograms; African golden cats vary from 8 to 16 kilograms. Most servals are spotted with markedly varying patterns, although many of these cats are black. They have large, untassled ears. The caracal is tan in color with large, black-backed ears that have long black tassels. The African golden cat is more robust in appearance, and the coloration of its spotting and background varies from red and yellow to smoky gray; some are without discernable spots on the sides of their bodies, but all have black blotches on their white or off-white belly fur. They have small black-backed ears. All three live in Africa but occupy different habitats. The African golden cat lives in rain forest and also in secondary or disturbed forests. The serval lives in moist savannas and woodlands. The caracal lives in dry thickets, savannas, and woodlands in Africa, but, unlike the others, extends into similar vegetation in Asia Minor and as far east as western India. All are solitary, terrestrial hunters that prey on small mammals, supplementing with birds, amphibians and reptiles, and insects. The caracal also feeds on hares, and servals sometimes fish. The caracal and African golden cat also hunt small ungulates, especially duikers. All three share their habitats with the larger leopard, and the caracal and the serval hunt in habitats frequented by lions and cheetahs.

At less than 10 kilograms, the bay cat (Catopuma badia) is smaller than the Asian golden cat (C. temminckii), which weighs from 10 to 15 kilograms. The bay cat has two color phases, reddish and blackish-gray, and the end half of the tail is conspicuously white underneath. The coat color of the Asian golden cat may be red, brown, or gray. The amount of spotting varies among individuals in both species, and both have distinctive faces with white lines bordered in black across each cheek. The bay cat occupies rain forest; the Asian golden cat ranges from rain forest into moist temperate forest. Both are thought to be primarily terrestrial hunters of mostly small mammals, which they supplement with birds, but we have no information on their food habitats beyond a few incidental observations.

The puma (Puma concolor) and the cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus) diverged from a common ancestor nearly 10 million years ago; the jaguarundi (Puma yagouaroundi) and puma diverged more than 5 million years ago. The lineage probably originated in Eurasia with a subsequent dispersal of both the cheetah ancestor and the puma and jaguarundi ancestor into North America, where the last two species diverged and then expanded their ranges into South America after the Panamanian land bridge formed about 4 million years ago. In South America, the puma’s and jaguarundi’s range and habitat use overlap those of nearly all the cats in the Leopardus Lineage, with the exception of the Andean mountain cat. The cheetah’s ancestor also dispersed into Africa. In western North America the speedy pronghorn antelope probably evolved in response to the cheetah’s predation. The cheetah and the puma disappeared from North America at the end of the Pleistocene, about 10,000 years ago, along with many other cat species. Genetic evidence indicates that the puma recolonized North America from South America sometime later. The cheetah and puma are medium-sized cats weighing less than 80 kilograms; the jaguarundi is a small cat weighing about 5 kilograms.

The solitary jaguarundi of today lives from northern Mexico to northern Argentina in a great diversity of habitats ranging from thorn forest to wetlands and tropical forest. It hunts on the ground and also apparently in trees and eats small mammals supplemented with birds, amphibians and reptiles, and fish. It is sometimes called the otter cat because of its mustelid-like shape. It has two color types: reddish or grayish, and neither is spotted.

The tawny-coated puma lives in a wide range of habitats from Patagonia to the Yukon. It needs cover for hunting. The largest pumas (males of 70 kilograms, and females of 45) are at the extreme ends of its long range; the ones that live in the tropics are about half as big. The solitary, terrestrial puma kills ungulates, including white-tailed and mule deer, elk, and bighorn sheep in the northern reaches of its range and guanacos in the southern reaches. Pumas eat white-tailed and brocket deer in Central and South America. They supplement these prey with larger rodents and other mammals seasonally. In Patagonia, they prey on the introduced European hare. Through much of the central part of its range, the puma overlaps with the larger jaguar. Biologists have found great overlap in what they hunt as well, with white-tailed deer being the most important prey. But pumas eat more different kinds of prey, from snakes to coatis, than jaguars do.

The cheetah is the only cat that chases its prey over relatively long distances. Now it lives only in sub-Saharan Africa and in small relict populations in Iran and in the central Sahara. Once it lived through southern Asia into India. Among the cats, cheetahs are also unique in that females live alone, but males live in small groups called coalitions. Their primary prey are gazelles, but they also take hares and larger ungulates from time to time. Cheetahs live in grasslands and in dry savannas and woodlands. They do not eat carrion, and they lose many of their kills to larger predators, including lions and spotted hyenas. Nearly everywhere they live, lions dominate cheetahs.

The Pallas’ cat (Felis manul) and the Felis Lineage, also referred to as the Domestic Cat Lineage, diverged from a common ancestor 10 million years ago; the Felis Lineage radiated in the Pliocene (5 to 1.8 million years ago). The black-footed cat (F. nigripes) is the next oldest radiation in the lineage, followed by the ancestor of the wildcat (F. silvestris) and Chinese mountain cat (F. bieti) and the ancestor of the jungle cat (F. chaus) and sand cat (F. margarita). These ancestors probably evolved in isolation from each other, with an east-west split. The domestic cat (F. catus) was derived from the wildcat about 7,000 years ago, probably in northern Africa (see When and Where Were Cats Domesticated?).

All are primarily terrestrial hunters, and all the wild species are solitary; feral domestic cats sometimes live in groups. All the wild species are either African or Eurasian in their distribution; the domestic cat lives nearly everywhere. There is considerable interbreeding between feral domestic cats and wildcats in Europe.

The black-footed cat and sand cat are extremely small cats, weighing less than 3 kilograms. The sand cat is tan in color and stocky, with the ears set wide on the sides of its head. The black-footed cat has large black or brown spots on a background coat, which varies in color from cinnamon-buff to tawny. The rest are small cats, weighing less than 10 kilograms at most and usually less than 5 kilograms. The northern wildcats are similar in color to domestic tabby cats. The wildcat in Africa has a shorter plain coat and slightly longer legs than the northern form. The Chinese mountain cat is gray with long hair. The jungle cat has a plain, tawny, short coat and appears to have longer legs than the northern cats in this lineage.

The sand cat and black-footed cat live in arid environments, although they do not overlap in distribution: the sand cat lives in true sand deserts; the black-footed cat lives in arid scrub and scrub steppe. In Africa, the wildcat lives nearly everywhere except in rain forest and true desert, although it does require cover. It lives in Mediterranean scrublands and in the temperate forests of Eurasia. In Scotland it lives in heather moorland and even in bogs. The jungle cat lives nearly everywhere except in the jungle, occupying disturbed areas, dry-forest shrub, and reed beds along rivers from Egypt to Thailand. The Chinese mountain cat inhabits mountain terrain, up to more than 4,000 meters in elevation, with brush, forest, and steppe, from central to western China, including the steppe and steep slopes of the Tibetan plateau. All the cats in this lineage eat various species of small mammals, supplemented with birds, amphibians, and reptiles, depending on the particular habitats. Occasionally they kill an ungulate fawn and feed on carrion.

Pallas’ cats have pale gray, thick, long fur, short legs, and live in the harsh continental-climate areas of central Asia from the Caspian Sea to central China up to elevations of 4,000 meters. While adapted to live in cold and hostile climates, they do not live where snow accumulates. They don’t live in true desert, but they do live in semideserts, in hilly areas, and in steppes with rocky outcrops. Russian biologists report that, apparently unique among cats, Pallas’ cats put on extra layers of fat when prey is abundant, to tide them over during long periods of inclement weather, when prey is in short supply. They live on pikas, small lagomorphs related to rabbits, supplemented by small rodents, partridges, and hares.

The origins of the Leopardus (or Ocelot) Lineage extend back more than 5 million years in North America. The members of this lineage entered South America via the Panamanian land bridge, thought to have formed between 4.1 and 2.7 million years ago. Nine species are now recognized in this radiation. This includes the recent decision by biologists that the pampas cat should now be recognized as three species: the Pantanal cat (Leopardus braccatus), the Chilean pampas cat (L. colocolo), and the Argentinean pampas cat (L. pajeros). Experts expect that the oncilla (L. tigrinus) will also be recognized as two distinct species, Central American and Brazilian. All the cats in this lineage are small (weighing less than 20 kilograms), and the oncilla, kodkod (L. guigna), and some Geoffroy’s cats (L. geoffroyi) are extremely small (weighing less than 3 kilograms). It is not surprising that this lineage holds no medium-sized or large forms, because the puma and jaguar occupy these ecospaces in its range. The cats in this lineage eat small rodents, supplemented with birds, snakes, lizards, and other small animals. Spot patterns of the species in this lineage can be so similar as to confuse experienced observers, but there is much intraspecific variation in background color and spot patterns.

These are all solitary cats, primarily nocturnal in their hunting, but radio-tracking data on some species indicate they may have crepuscular and even diurnal hunting bouts. The margay and oncilla are primary arboreal hunters but also hunt on the ground. The remainder of the species in this lineage are primarily terrestrial hunters. The oncilla lives in dry and humid evergreen forests and scrubland from southern Costa Rica to northern Argentina. Its distribution in the Amazon rain forest is not known in detail, but it usually lives at higher elevations than the margay (L. wiedii) or ocelot (L. pardalis). Margay and ocelot ranges extend from northern coastal Mexico to northern Argentina, where the margay is confined to humid tropical forests, premontane moist forests, and cloud forests, and the ocelot lives in a wide variety of habitats from rain forest to thorn shrub. A small population of ocelots also still lives in the Rio Grande Valley in Texas. Margays seem not to tolerate human disturbance, but ocelots can live in disturbed areas.

The Andean mountain cat (L. jacobitus) lives in open landscapes at high elevations in the central Andes. The Argentinean pampas cat (L. pajeros) lives in the high steppe on the eastern slope of the Andes from Ecuador to Patagonia; in Argentina, it lives in lowland steppe, shrubland, and dry forest habitats. The Pantanal cat lives in the humid, wet, and warm grassland and forest areas of moderate elevation in Brazil, Paraguay, and Uruguay. The Chilean pampas cat lives in subtropical forest and in high-elevation steppe in Chile on the western slope of the Andes. The kodkod lives in the southern conifer and deciduous forests of Chile and Argentina. The Geoffroy’s cat lives in open woodlands, brushy areas, open savannas, and marshes, but not in subtropical rain forest or southern conifer forests, where it is replaced by the kodkod.

The Andean mountain cat, ocelot, and margay form one branch in this lineage, with the Andean mountain cat separating first, followed by the separation of the margay and ocelot. The second radiation was the pampas cats, which diversified in the Pleistocene. The third radiation within the lineage was the Geoffroy’s cat, kodkod, and oncilla. The divergence in the three main groups probably occurred in North America, before the formation of the Panamanian land bridge. The radiations continued after these species entered South America. Today, the Andean mountain cat lives apart from any of the others in the lineage. The geographic ranges of the ocelot, margay, and oncilla overlap to a considerable extent. The Geoffroy’s cat and kodkod in southern South America overlap to some extent but are reported to live in different vegetation types. The geographic ranges of the ocelot, margay, Pantanal cat, oncilla, and Geoffroy’s cat overlap in northern Argentina and Paraguay. A natural hybrid has been reported between an oncilla and Pantanal cat.

We don’t know all of the factors that control how many species can coexist in a given place, but some general patterns in species diversity have been discovered. In areas of comparable size, more species live in the tropics, and the number declines as one goes north or south toward the poles. The more stressed the environment, the fewer species will live there; for example, deserts and the Arctic tundra have fewer species than the wet tropical forests. The more favorable conditions are for biological production (in terms of the amount of plant and animal biomass produced annually), such as warm temperatures and abundant rainfall, the more species will be found there. Strongly seasonal environments have fewer species than aseasonal environments. There is a strong relationship between species diversity and habitat complexity. Mountains have greater species richness than flatlands. Natural disturbance also influences species richness. Landscapes disturbed by fire, floods, landslips, and similar events are a mosaic of different habitats that support a greater number of species.

The larger the area you consider, of course, the more species will live there, because by expanding the area under consideration, you also increase the chance of including additional habitat types and species whose ranges are restricted. This relationship is called the species-area curve. If you pick as your starting area, for example, the 2,168-square-kilometer Khao Yai National Park rain forest in central Thailand, you will find that four wild cat species are known to live there: the tiger, the leopard cat, the marbled cat, and the clouded leopard. We don’t know why the Asian golden cat and fishing cat are not in the Khao Yai (in other areas they live in rain forest), but by expanding the area under consideration to the 514,000 square kilometers that make up all of Thailand, these two species are added, plus the jungle cat, the flat-headed cat, and the leopard, for a total of nine cat species.

Jungle cats are common in Thailand, but they live in disturbed areas around villages and in scrubby vegetation, perhaps because the dominant rain forest cats, which exclude the jungle cat from their habitat, do not find favorable conditions for themselves in the scrubby areas. We suspect that the leopard is excluded from Khao Yai because tigers live there, although leopards and tigers both live in rain forest on the Malay Peninsula. The flat-headed cat is restricted in its distribution to below the Isthmus of Kra at the southern end of Thailand and does not occur in northern Thailand. If you expand the area to include all of Southeast Asia, including the Greater Sunda Islands, you will find a total of 10 cat species. The only additional species is the bay cat, endemic to Borneo.

The number of species tends to increase with the size of islands as well. There are seven cat species on 427,300-square-kilometer Sumatra, four cat species on 126,700-square-kilometer Java, and two cat species on the adjacent 5,500-square-kilometer Bali; although the tiger is only recently extinct on Java and Bali. Also, the more remote the island or the longer it has been separated from the mainland, the fewer the species that exist there. Borneo is much larger (743,200 square kilometers) than the other Greater Sunda Islands listed above, but it has been separated longer and has only five cat species.

Geography matters in other ways as well. Through the shifting of the Earth’s plates, mountains rise, creating barriers to dispersal. The formation of glaciers created barriers to dispersal in some parts of the world but also lowered sea levels in other parts of the world, creating dispersal corridors. This is how cats representing the different lineages dispersed from their places of origin to the different continents or ended up in one corner of their former range. For example, the entire Leopardus Lineage radiated just before and right after entering South America when the land bridge formed between North and South America (4.1 to 2.7 million years ago). The process of barriers appearing and disappearing is ongoing. Pleistocene (1.8 million to 10,000 years ago) cooling and glaciation caused massive extinctions and displaced many communities. Now, cats representing the different lineages have, in some cases, come to live together in one place or returned to old haunts in different forms.

Ten different wild cat species belonging to five different lineages live in the mountains at the eastern edge of the Tibetan plateau, in central China—one of Earth’s most important biodiversity hot spots but also one with a large human footprint. Animals adapted to five different broad zones—northwestern mountains, western escarpments, Tibetan plateau, central basin, and subtropical forest—converge here. In these mountains or at their western or northwestern edge, are the Pallas’ cat and Chinese mountain cat from the Felis Lineage, the only species that are found here but nowhere else; and on the southern edge are the jungle cat, also from the Felis Lineage; the Asian golden cat from the Bay Cat Lineage; the leopard cat from the Leopard Cat Lineage; the Eurasian lynx from the Lynx Lineage; and the clouded leopard, leopard, tiger (now extinct), and snow leopard from the Panthera Lineage.

Usually, all of these species would not be found within the same 10 square kilometers or even the same 1,000 square kilometers, but this mountain system is a very heterogeneous environment that provides living opportunities for many different cat species. Elevations range from 500 meters in the Sichuan Basin to snow-clad peaks of 7,000 meters. Habitats range from rock and snow to alpine meadow and thicket, to subalpine coniferous forest, coniferous and deciduous broadleaf forest, evergreen and deciduous broadleaf forest, and evergreen broadleaf forest. Riparian habitats border streams, rivers, and mountain lakes. The climate varies from maritime, with heavy summer rains and cool winters, to severely continental, with very cold winters and dry summers.

Ten cat species also live in Southeast Asia (as discussed above), representing four lineages along with the marbled cat of ambiguous lineage. Some of the species are found both here and in the Chinese mountain complex, and some are found only here. Three cat species are endemic to Southeast Asia—the flat-headed cat, the bay cat, and the marbled cat—and we assume evolved there. The fishing cat probably also evolved in Southeast Asia but now has a wider distribution into south Asia. These four species do not seem to enter the Chinese mountain complex. The Eurasian lynx, snow leopard, Pallas’ cat, and Chinese mountain cat are not found in Southeast Asia. The tiger, leopard, Asian golden cat, and leopard cat live in both.

The pattern of species richness reflects the balance between regional processes that add species to communities (species formation and geographic dispersal opportunities) and local processes that contribute to local extinction (predation, competitive exclusion, adaptation, and chance events). Landscapes include a multitude of partly overlapping cat distributions, and the distributional boundary of each species reflects its relation with the environment. This includes the distribution of its potential prey, its competitors, the depletion of its potential prey by its competitors, its predators and pathogens, and its physiological response to the environment.

On a more local level, competition among cats determines how many may live in an area. No two species can occupy exactly the same niche—the place in an ecosystem where a species lives, what it eats, its foraging routes, activity times, and so forth. Coexisting cat species may avoid competition by hunting different prey, or by using different spaces, or by hunting at different times. Or they may be different enough in size or some other feature that they don’t directly compete.

There are only three species—puma, bobcat, and Canada lynx—living in the Salmon River Mountains in Idaho. Pumas, the largest, dominate and are the most wide ranging, killing mule deer and elk in the winter and expanding their diet to include marmots and ground squirrels in summer, when they move to higher elevations. In winter, bobcats live in the bluffs and along the lower streams, where they kill mostly rodents, the occasional grouse, small birds, and doe and fawn mule deer. They take about the same fare in summer but at higher elevations. Canada lynx, about the same size as bobcats here, are rare and are confined to the upper elevations, even in winter, where they specialize in hunting snowshoe hares and red squirrels. With their large footpads, lynx sink less in snow than bobcats and pumas do. This snow-sinking factor is called foot-loading and is measured by grams of body weight per square centimeter of foot pads. Snowshoe hares have foot-loading values of about 10; lynx, about 100; bobcats, 300; and pumas, 1,000. These cats are separated by body size, locomotion adaptations, prey type, and habitat type, but, even with this ecological and morphological separation, the primary cause of death in bobcats is puma predation.

Tigers, leopards, fishing cats, leopard cats, and jungle cats live in Nepal’s Royal Chitwan National Park. Conservation biologist Dave Smith radio-tracked fishing cats and found they do not go into the riparian forest but stick to riverbanks and the tall grassland and banks of old oxbow lakes beyond the forest. They fish and also kill rodents. Jungle cats live at the edge of the forest and are seen in the grassy areas near occupied and abandoned villages. They presumably live on rodents and the wayward chicken they can catch. Leopard cats seem to be restricted to the mixed forest. John found that leopards and tigers use the same areas of forest and grassland edges and kill the same ungulate prey species, but the smaller leopards kill prey that are about one-fourth the size, on average, of the tiger’s prey (Seidensticker 1976). The leopard is more active in the day than the tiger and uses different trails and stream crossings from those of the tiger. Tigers kill leopards; leopards kill leopard cats.

The tiger, clouded leopard, marbled cat, flat-headed cat, fishing cat, Asian golden cat, and leopard cat—seven species—can potentially live in the same areas in Sumatra; they all occur on the island. (In this cat assemblage, competitors apparently have squeezed the usually tenacious and generalist leopard out, because it does not occur on Sumatra.) No one has yet determined if all seven species actually live in one area or how those that do live in the same area manage to divide resources. We assume two factors: that the Sumatran rain forest provides a variety of different microenvironments that don’t vary much over the year as well as a variety and abundance of potential prey, and that each cat species is a specialist in its own right. These factors may result in the denser packing of species in this tropical rain forest on the equator than in subtropical Nepal at 27° north latitude, with its five species, or in temperate Idaho at 45° north latitude, with three species.