Forager

SAN FRANCISCO AND THE MEDITERRANEAN  1994 to 1998

1994 to 1998

“Aside from the greens offered in the typical American supermarkets there are more than eighty different edible greens that I believe will in time be cultivated and/or foraged for consumption. Just as we now often find wild mushrooms in stores, I foresee a time when purslane, nettles, mallow, lamb’s quarters, and wild fennel will be on the produce counter along with mesclun, radicchio, frisée, arugula, braising mixes, and baby spinach leaves, which, though previously rare, are now thankfully commonplace.”

—Paula Wolfert in Mediterranean Grains and Greens

IN 2008, for a story in Food & Wine about an aristocratic Sicilian winemaker, I was given a recipe with a wild Mediterranean herb so obscure that the cook provided its Latin botanical name, S. vulgaris. The magazine ordinarily avoided ingredients no one could find. But suddenly, thanks to chef-foragers like Daniel Patterson and René Redzepi, wild greens were cool. I just needed to offer a store-bought substitute. For help, I e-mailed two Italy-based food writers and, for insurance, Paula. The first two were stumped. Paula responded within the hour.

“Silene vulgaris,” she wrote. “It’s called bladder campion in English. For a sub, you can use a combo of young spring greens like pea shoots, baby spinach and arugula. See Grains and Greens, p. 348.”

In the introduction to this book, I called Paula a messenger from a future we now inhabit. But that’s not entirely true. Mediterranean Grains and Greens, her sixth book, published in 1998, describes a future that’s not yet here: a world in which supermarkets stock wild greens such as hop shoots and stinging nettles along with kale and chard, and home cooks sort greens by flavor—sweet spinach, for example, versus peppery arugula—and then blend them the way the winemakers blend grapes.

“Blending salad and cooking greens may sound a bit like alchemy,” she wrote, “but if done properly it can add great depth to leafy green dishes. I encourage you to experiment; mixing greens can be an endless pleasure.”

In Grains and Greens, Paula pursued some of the most creative work of her career, especially in the field. In a wonderful merging of an old love with a new—her longtime romance with travel, and a revived passion for gardening (and weeds)—she “picked her way around the Mediterranean,” as she put it, to uncover breathtaking variety in two humble plant categories. She took new liberties with her recipe titles, too, using whimsical turns of phrase like Best-Ever Bugulama, a Turkish pilaf (recipe, here) or Biblical Breakfast Burrito, essentially a Greek salad with feta rolled up into a durum flatbread slathered in hrous, a Tunisian pepper spread similar yet superior to harissa (hrous recipe, here).

In every introduction to her books she took a different stab at explaining her approach; in Grains and Greens she got closest to the truth. She disputed her reputation as an anthropologist, instead admitting that her work was more imaginative. “Even though I work hard to achieve authenticity in my recipes and never make dishes up out of my head, I don’t consider myself a cultural anthropologist. Far from it,” she wrote. Her approach—and the art of cooking—required too much “instinct” and “improvisation.” In Grains and Greens, Paula performed a bold, book-length improvisation on two notes.

“This book was a turning point for me in many ways,” she told me. “My earlier books are not as daring as I got in this book. But I knew enough now [that] I could really jump in and do things. This was like putting your hands in the earth.”

But where the innovations of Eastern Mediterranean achieved widespread acceptance over time, amplified by a handful of food leaders, the improvisations of Grains and Greens still need a microphone.

It’s possible Paula would never have written Grains and Greens had she not moved to San Francisco. In the Bay Area—the most Mediterranean of all US cities—she saw big changes afoot in the grains and greens Americans would soon eat, changes that would inspire her to write the book. Yet for all its Tangier-esque produce and eccentric characters, she didn’t like the city at first. In December 1994, Paula left the East Coast, “kicking and screaming,” as she told the San Francisco Chronicle. Bill used the proceeds from his best-selling crime novels to lease a stunning prewar apartment high on Russian Hill, with gorgeous views of San Francisco Bay to the north and east and a roomy kitchen.

Paula loved the views. She also felt a little better about living on the West Coast after her son, Nicholas, moved to Los Angeles in 1997 to work in the movie business. (Her daughter, Leila, then a wine wholesaler, still lived on the East Coast, in the Hudson Valley north of New York City, where Paula visited her regularly.)

She struggled to feel at home in San Francisco, however. She didn’t like walking the hills (she always hated exercise). And she had no idea what to make of the food world, which felt almost too friendly compared to cutthroat New York. “Everyone was so nice,” she recalled, still bewildered. She reunited with old friends Alice Waters and Judy Rodgers (whom she met when Rodgers was a teenaged apprentice in Southwest France) and became close with food writers like Peggy Knickerbocker. In 1995, San Francisco magazine wrote, “Paula Wolfert moving to San Francisco (as she did last year) is like Barry Bonds being traded to the Giants—a veritable coup for the home team.”

With San Francisco friends, including Alice Waters and Peggy Knickerbocker (second and third from right, respectively)

But for once she felt uneasy about all of the attention. She wasn’t sure who liked her because she was Paula Wolfert and who liked her for her. She told Boston Globe food editor Sheryl Julian, “When you live in New York, you come up in the trenches shoulder to shoulder. In San Francisco, it takes a long time to make a best friend.”

She quickly chose a new book topic, one that required many more visits to her friends across the Mediterranean. But the topic had roots in San Francisco’s exploding supply of organic produce. During the second half of the 1990s, the number of farmers’ markets around the country shot up. The organic-driven supermarket chain Whole Foods expanded its reach; its first San Francisco outpost was just a few blocks from Paula’s apartment. To save her from walking the steep hills, her new friend Knickerbocker gave her rides to Whole Foods during the week, and to the pioneering new Ferry Building farmers’ market on Saturdays. Seeing all of this easy urban access to such good food, Paula predicted Americans could soon take on two next-level ingredients: wild greens and alternative grains.

Grains made a certain amount of sense. In 1994, William Rice wrote in the Chicago Tribune, “After years of going against the grain, so to speak, potato-loving Americans are being tempted to try grains with such names as couscous, bulgur, millet, barley, polenta, quinoa and amaranth as well as rices such as Italy’s arborio, India’s basmati, Spain’s Valencia and the Orient’s jasmine.”

Greens, too, had gained cachet for their nutritional qualities—particularly bitter leafy ones. But wild ones?

“Weeds are the coming thing,” Paula insisted to a Connecticut publication in 1994.

In a literal sense she was right: more organic produce meant fewer herbicides, which meant farmers had more weeds on their hands, many of them edible. But could they become trendy?

For evidence of a coming trend, in San Francisco she could point to Rodgers, who bought wild greens for Zuni Café and connected Paula to her source. Or to Chez Panisse, where her new friend, chef Catherine Brandel, was also an enthusiastic forager. Paula also remembered urging on the trend herself at the Ferry Building, where one Saturday she spoke through a bullhorn to implore farmers to bring mallow, purslane, nettles, and other weeds to the market for her (and everyone else) to buy. To add enticement, she spoke and wrote about their nutrition, as well. “The best part of the Mediterranean diet is the weeds,” she told the San Francisco Chronicle in 1995. “That’s why these people are so strong. Purslane and nettles and amaranth and goosefoot—these are the future greens, and they’re delicious.”

Fran McCullough, her former editor, came up with the book’s title, though she was not its editor. “She knew where the cutting edge was,” McCullough said. “Grains and greens were very popular at the time. She was doing it through gritted teeth, but she really wanted to have a big commercial hit. To me the idea seemed perfect, where everything was headed.”

Paula does not remember wanting a hit. “There is something wrong with me,” she said. “I never did the right things to make money. I could have created a product, a line of cookware, or gone on television. I just did the things that interested me.” Whatever her motivations for picking the initial topics, the book soon lost any potential for mass appeal as it traveled down the rabbit hole of Paula’s mind.

Grains had interested her since she discovered couscous. Wild foods also pop up like weeds along the path of her career. She bought her first wild mushrooms in the Tangier markets in 1959; she cooked her first purslane and mallow with Madame Jaidi in 1972 to prepare a wild greens jam (recipe, here). In the 1980s, she first studied foraging with the best: chef Michel Bras, among the earliest haute chefs to “pick” for his restaurant. She later honed her skills at her and Bill’s vacation home in Martha’s Vineyard and in Connecticut.

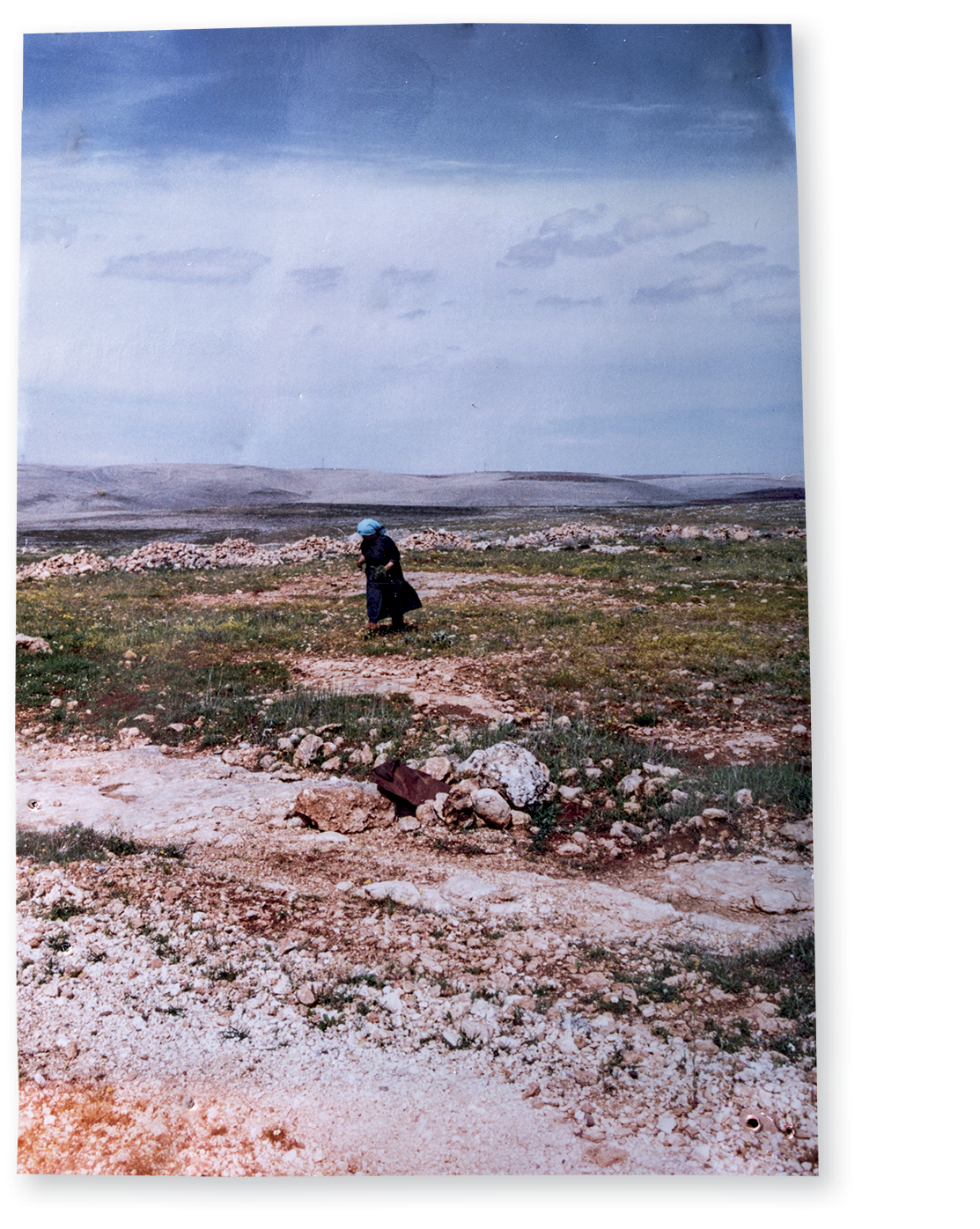

But she didn’t think she wanted to dedicate a portion of a book to wild greens until she had her first Mediterranean foraging adventure in 1991. While researching Eastern Mediterranean, in a village outside Gaziantep, Ayfer Ünsal introduced her to Zeliha Gungoren, a gifted Armenian Turkish cook who announced they would pick lunch in a field by her house. To Paula, the field looked as barren as the moon (see picture). But Gungoren, who had looked after her family flock as a child, had learned to forage from fellow shepherds. Paula wrote in Saveur, “Soon my notebook is filled with pressed specimens—corn poppies, wild mustard, nettles, mallow, and more.” Gungoren transformed their haul into a dozen dishes, including a robustly flavored bugulama, a warm grain salad (recipe, here). Paula could hardly believe that so many flavors could spring from such seemingly bare terrain. She became obsessed with learning all she could about edible weeds. “I went on a greens binge,” she said.

Paula’s 1991 snapshot of her first foraging adventure with Zeliha Gungoren, outside Gaziantep, Turkey.

From 1994 to 1998, Paula picked her way across Greece, Israel, Italy, Turkey, Tunisia, and Spain, tapping her old friends for new greens (and grains) intel. She timed many of her trips to coincide with Oldways conferences, making her arrangements to do her field work before, during, and after the events to take maximum advantage of the free airplane tickets.

In Greece, Paula first learned about the Mediterranean practice of blending greens for richer flavors. Aglaia Kremezi, her research partner, didn’t have much experience with weeds, having grown up in Athens. (Paula says that Kremezi’s knowledge has since surpassed her own.) When she learned of Paula’s interests, Kremezi tracked down Mirsini Lambraki, a wild greens expert who took them foraging in Crete. There, Lambraki introduced them to the Mediterranean tradition of apron greens, something Paula later found in Turkey and Italy. Before heading out to pick, home cooks (mostly women) donned three-pocketed aprons so they could easily sort their finds by flavor: one pocket for sweet greens, one for peppery, one for bitter (or for roots and mushrooms). They often cooked their blends into stuffings or sauces. These blends gave Paula the idea that all greens, wild or cultivated, should be mixed by taste. She included suggestions in the book.

In Israel, Paula had her ultimate foraging experiences. On a press trip to Jerusalem, she met Moshe Basson, a chef known for modern takes on ancient Middle Eastern recipes. Having foraged since he was a boy, Basson took Paula into the hillsides around Jerusalem to pick wild purslane. She liked the greens so much, she engineered a return about a year later in the early spring, when wild greens peak.

Sara Hatan foraging with her flock, photographed in Israel by Paula

On her second trip, she heard her first warning about the potential unpopularity of the topic, even in the Mediterranean. On a farm in the Galilee, a Kurdish Iraqi woman named Sara Hatan took Paula picking at dusk, a journey during which they worked their way through a dazzling profusion of over thirty edible weeds, including a patch of sow thistle so thick that Paula named it “sow thistle alley.”

“I was in a state of bucolic exhilaration,” she wrote. Hatan told her, however, that even Israelis weren’t interested in eating wild greens anymore—for poignant reasons. “Mallow and nettles had kept both Israelis and Arabs from starvation during the austere wartime period following Israeli independence,” Paula wrote. Eating them reminded them of those bitter years.

Undaunted, Paula forged ahead. Recognizing that it was impractical for cooks to rely solely on foraged wild greens, in the book Paula introduced both lesser-known varietals and new ways to cook store-bought greens. She urged readers to plant Lacinato (Tuscan) kale, which was not yet available in stores. She predicted that the variety was “a vegetable success story waiting to happen, much like radicchio a few years back.” (She was correct.) She found traditional but unorthodox cooking methods, such as salting and massaging chopped greens for bugulama, or presalting greens to concentrate their flavors before cooking them in an unusual northern Greek sprinkle pie (recipe, here).

Ever eager for new discoveries, Paula looked for little known but delicious grain dishes. Since everyone knew about paella from Valencia, she asked Spanish food expert Janet Mendel to help her research the more obscure arroces (rice dishes) from the nearby coastal region of Alicante.

In Italy, polenta turned into an obsession. While in the Marche, Paula became enamored with the use of polenta boards, the tradition of pouring just-cooked soft polenta out onto long planks, then topping it with a sauce. Although the porridge-like cornmeal dish traditionally requires long stirring, in San Francisco she stumbled on a no-stir, oven-baked polenta (recipe, here) that brings out the corn flavor of the cornmeal. In a classic example of her thoroughness, she even studied an American equivalent with an expert home cook from North Carolina, James Villas’s mother.

“Mother said, ‘Don’t tell me about polenta, honey. In the South we just call that corn mush,’” Villas recalled. “Well, that intrigued Paula, and she immediately had to know everything about corn mush. That’s the closest I ever knew Paula to come to American food.”

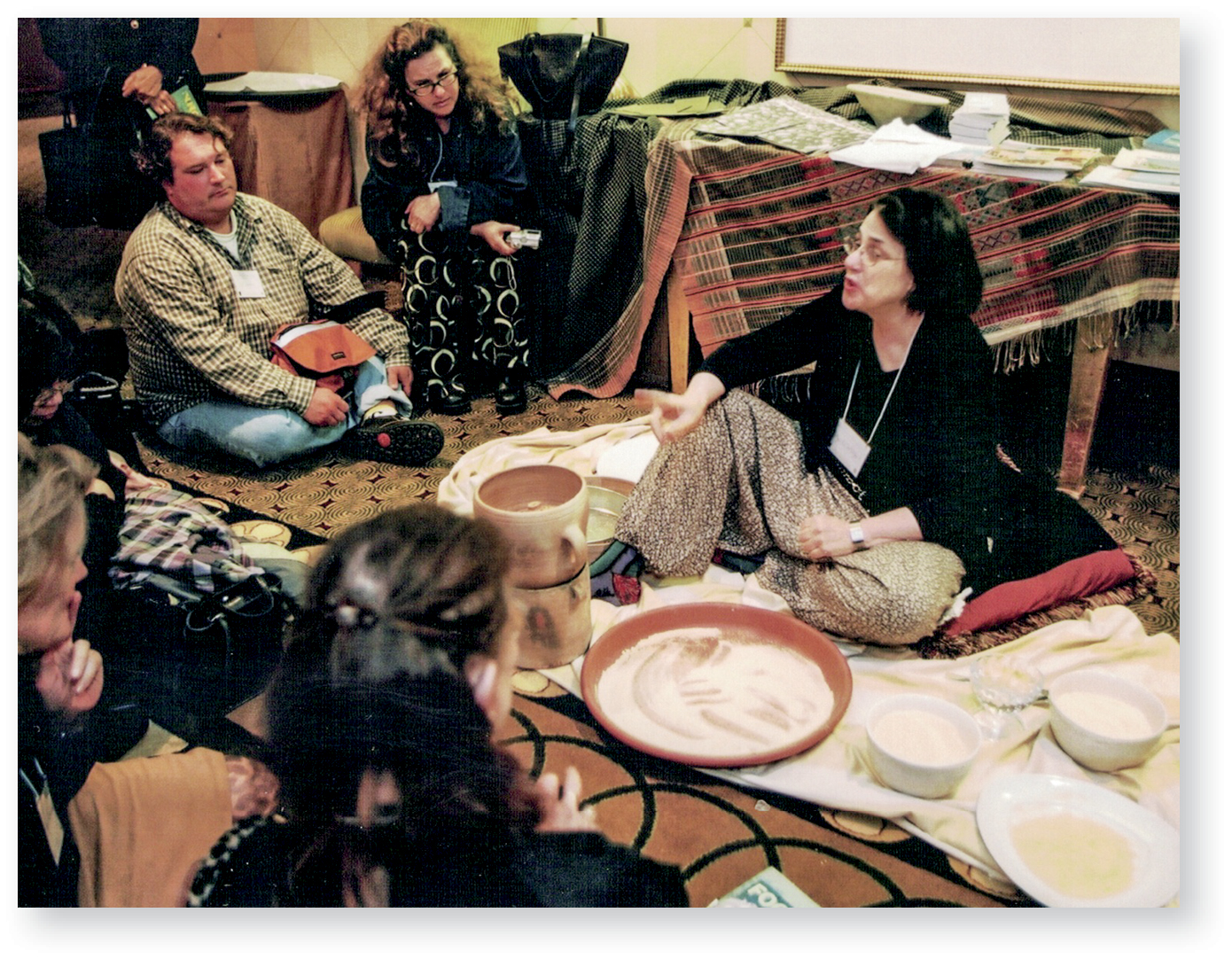

In Tunisia, Paula finally learned to hand-roll couscous (recipe, here). Despite her reputation as the queen of couscous, she’d never learned this in Morocco because, she was told, it was only rolled (and sun-dried for storage) once a year, when the semolina was freshest. She also saw little point to including the method in Couscous, as it required two sizes of semolina grains, neither then available in the United States. By the mid-1990s, however, two of her favorite mail-order food retailers, Sahadi’s and Kalustyan’s, carried both sizes, so she began teaching classes on hand-rolled couscous in San Francisco and New York.

Giving a couscous-rolling demonstration at the Culinary Institute of America at Greystone in Napa, California

In Morocco for an Oldways conference in 1994, Paula barely recognized heavily developed Tangier. She visited the old villa where she and Bill had lived, only to despair that her garden had been stripped of its many fruit trees. But at a dinner arranged for her at the home of the grandson of El Glaoui, the famed pasha of Marrakech, she enjoyed the best Moroccan meal of her life—including a pigeon tagine with hand-peeled grapes—which she described in a 1995 story for Saveur.

There is a frantic quality to Paula’s late-1990s travels, as though she sensed these might be her last adventures. The book, too, displays a manic quality that suggests a race to squeeze in everything she could. It is possible she had begun to experience early Alzheimer’s symptoms; friends say her anxieties peaked in these years. She turned sixty in 1991 and started to regard her mortality as a burdensome inconvenience.

“I need five more lifetimes to accomplish everything I want to do,” she told San Francisco magazine.

To impose a little reader-friendly organization, Susan Friedland, her editor at HarperCollins, suggested they alphabetize the grains and greens. But Paula stood her ground. She wanted everything in the order she had assembled it, according to her interests.

Paula photographed in People magazine, blanketed by greens

“I lost that battle, but it was her name on the book,” Friedland said. “The subject matter was very ahead of its time.”

Had it been published today—now that purslane and nettles are available in high-end supermarkets, foraging has become fashionable, and many people have gone gluten-free, creating a new market for alternative grains—the book might have become an overnight sensation. But in 1998, the two topics still seemed so obscure that the book provoked genuine frustration, even among her most devoted fans.

In Saveur, for example, magazine cofounder Dorothy Kalins wrote, “I wonder, as I confront her deceptively simple new title… if focusing on just two kinds of ingredients isn’t like trying to write a novel without the vowels? But no. Wolfert’s book is more like culinary science fiction, where you encounter an entire cast of alien ingredients.”

Other reviews poked fun at the book, at how it all but made a farce of Paula’s obsessive ways. People magazine justifiably warned readers, “Although she coaxes recipes for primal dishes like Cretan Snail and Fennel Stew out of a friend’s deaf Greek aunt, Wolfert’s tantalizing dishes for edible weeds require knowledge of foraging, and the book is not illustrated.”

In a more favorable review in Slate by Nicholas Lemann titled “The Diva,” the subtitle read, “Paula Wolfert is very high-maintenance, but she’s worth it.” Lemann wrote, “The sense-memories that linger after a week of cooking from Mediterranean Grains and Greens are of an intensity, a range, and an unusualness of flavor that you just don’t get from more conventional cookbooks.” At the same time, “the ratio of Wolfert advantages (daring, refusal to compromise, authenticity, unconventionality) to Wolfert disadvantages (her tendency to induce an overwhelming feeling of ‘why bother?’) is as high here as it has ever been.”

Today the book is out of print. But it shouldn’t be. It is a wonderful expression of Paula’s passions, and its time feels nearly here. It may seem farfetched, but hop shoots are now available every spring in Oregon. The day does not seem far off when Whole Foods will stock them, if only in their freezers.

When Mediterranean Grains and Greens appeared in 1998, Paula seems to have worked more aggressively than usual to promote her ideas. For about a year and a half, she wrote articles, gave talks and hosted dinners, and introduced food editors and chefs to the flavors of wild and blended greens. She still cooks with them at home. But in her work, as always, her curiosity got the best of her. She soon moved on. She had a new territory to explore: Sonoma.

She and Bill had bought a weekend house there not long after moving to San Francisco. It had everything she’d loved about Tangier: a warm, almost Mediterranean climate with near-constant sun, amazingly fresh local produce, a small plot to grow her own vegetables (and weeds), and a cast of oddball characters. In the warmth of its embrace, she felt ready to try a personal first, something trailblazing in these quickening, Internet-driven times: slowing down.