CHAPTER 2

OCI Identity and Access Management

In this chapter, you learn how to

• Explain IAM concepts

• Describe resource locations and identifiers

• Create IAM resources

• Federate OCI with various identity providers

• Set up dynamic groups

Management of on-premises IT equipment increases in complexity as the infrastructure scale increases. It is not uncommon to encounter huge server farms in data centers dedicated to single organizations. These servers are connected by countless networking interfaces, devices, and cables to banks of disk and tape storage devices in a seemingly endless, often overwhelming, infrastructure sprawl. Frequently, teams of engineers and administrators supporting systems, networks, storage, the database, and security roam these halls in an effort to meet ever-increasing and demanding service-level agreements (SLAs) with the respective lines of business that depend on the harmonious operation of both human and machine infrastructure resources.

The Identity and Access Management (IAM) service enabled by default in OCI encompasses the three A’s of security: authentication, authorization, and access. Through a simple, yet powerful, set of entities comprising groups, users, and dynamic groups of principal instances, IAM constructs allow for secure access and governance of OCI resources, including compute instances, block volumes, and VCNs.

This chapter explains the IAM concepts supporting OCI and provides a detailed overview of the policy language, passwords, and keys, and a discussion on identity federation with various identity providers.

Explain IAM Concepts

IAM in OCI revolves around several novel concepts such as tenancy and compartments, while utilizing relatively familiar constructs such as users, groups, and policies. Figure 2-1 depicts policies as the mediating construct between groups of users interacting with OCI resources that are logically separated into one or more potentially nested levels of compartments residing within your tenancy.

Figure 2-1 IAM concepts

Resources

Typical on-premises IT infrastructure resources include servers, SANs, and network infrastructure. OCI infrastructure resources have a parallel definition and refer to artifacts, including compute instances, block storage volumes, object storage buckets, file system storage, virtual cloud networks (VCNs), load balancers, and Dynamic Routing Gateways. The previous list is not exhaustive and is constantly expanding as new computing resources and technologies are activated on OCI.

Your OCI resources may also fall victim to infrastructure sprawl unless a well-planned, standards-based architecture and nomenclature for resource management is established at an early stage in your OCI adoption. If such a system is already in place with your on-premises resources and is working well, it will provide a great baseline onto which the new concepts can be bolted.

Bear in mind that cloud infrastructure adoption should be transparent to your end-users. At the end of the day, your HR executive probably cares more that the people management applications are available, performant, and meeting SLAs, and less about the underlying infrastructure.

Some organizations have data residency regulations that restrict the geographical location of data. These requirements may be accommodated if there are geographically local OCI regions. For example, the initial OCI regions came online in the United States. Many public sector organizations in Canada have a regulatory restriction on data leaving Canadian soil. Oracle has provisioned a Canadian region with an availability domain in Toronto, which has opened the door for widespread OCI adoption in that region. Another design consideration to bear in mind relates to data sovereignty. Some organizations have regulatory limitations on the location of the staff who work on their data. For example, a large Canadian insurance corporation has a legal obligation to its policy holders guaranteeing that their data is never worked on by non–Canadian-based staff. This poses a challenge to infrastructure management which is met by a simple, guaranteed mechanism to logically segregate OCI resources discussed in the next section.

OCI resources are categorized by resource-types. An individual resource-type is the most granular and includes vcn, subnet, instance, and volume resources. Individual resource-types are grouped into family resource-types such as virtual-network-family, instance-family, and volume-family. Resource-types may also be referenced as an aggregation of all resources at both compartment and tenancy levels as all-resources. These resource-types are important for defining resource management policies.

Tenancy and Compartments

OCI resources are collectively grouped into compartments. When an OCI account is provisioned, several compartments are automatically created, including the root compartment of the tenancy. An OCI resource can only belong to one compartment. Because compartments are logical structures, resources that make up or reside on the same VCN can belong to different compartments.

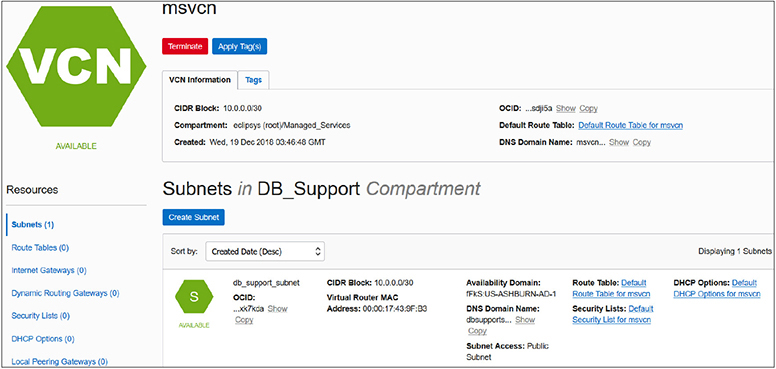

Figure 2-2 shows a VCN called msvcn created in the Managed_Services compartment, with a subnet called db_support_subnet created in the DB_Support compartment. Although this subnet resides in the msvcn VCN in the DB_Support compartment, compute instances that use the db_support_subnet do not have to reside in the DB_Support compartment. You could create an instance in any other compartment using the db_support_subnet. It is useful to think of compartments as responsibility areas. You may want the Networks team to create and maintain the network resources such as the VCN, subnets, route tables, and security lists grouped in the Networks compartment. You may want the Systems team to manage the compute instances in the Systems compartment that use a VCN from the Networks compartment. In this regime, each team manages and maintains resources appropriately using compartments to segregate duties and responsibilities.

Figure 2-2 Resources in multiple compartments

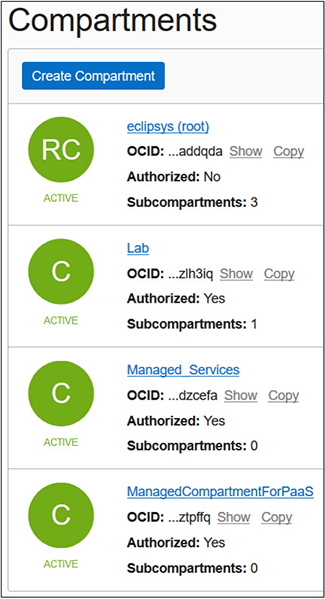

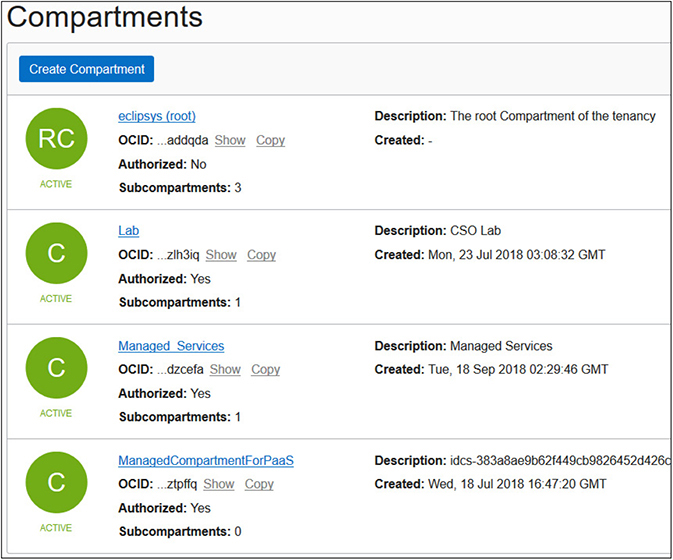

A tenancy is synonymous with your cloud account and comprises a hierarchy of compartments with the root compartment at the top. There can be many compartments, and as of this writing, compartments may have child compartments nested six levels deep. Figure 2-3 lists the root compartment (RC) along with three nested or child compartments (subcompartments) named Lab, Managed Services, and ManagedCompartmentForPaaS. When this cloud account was provisioned, the root compartment named after the cloud account (eclipsys in this case is the cloud account name being used) and one subcompartment (named ManagedCompartmentForPaaS) were automatically created. Avoid renaming or deleting the objects created by default such as the ManagedCompartmentForPaaS compartment. OCI PaaS services depend on the existence of this compartment. Notice that the Lab compartment, despite being nested in the root compartment, has one child compartment. Subcompartments belong to parent compartments and cannot be moved around.

Figure 2-3 Compartment list

Tenancy and compartments are global resources and span across regions and availability domains. In other words, this mechanism supports resource segregation or grouping regardless of the physical location of the resource.

Business units within organizations are typically clients of the IT department. It may be convenient to group all infrastructure resources consumed by a specific department into their own compartment. A trend in infrastructure support is to track infrastructure usage for cost management. There are many compelling reasons for this trend. This model supports accurate financial budgeting, improves capacity planning, and reduces infrastructure sprawl. Compartments support this model. A typical organization usually has HR and Sales departments. Infrastructure that hosts HR applications is often different from the infrastructure used by Sales applications. It is a simple matter to create HR and Sales compartments and provision their respective infrastructure resources by logical compartment groupings. You then have an accurate understanding of resource consumption. This approach supports the implementation of an internal chargeback mechanism. Compartments also allow resources to be secured and managed as a single entity. Once a compartment is created, it is typical to create a policy to allow appropriate access to the resources in the compartment.

Users

An OCI user is an individual or system that requires access to OCI resources. There are three types of users:

• Local users

• Federated users

• Provisioned (or synchronized) users

Local users are created and managed in OCI’s IAM service. Local users can only access OCI services. For example, user Jason is created using OCI’s IAM service by navigating to Identity | Users and selecting Create User. After providing a name and description and choosing Create, a new local user is created. This user has a local password and, by default, is capable of logging in to the OCI console. When the tenancy is provisioned, the administrator receives a customized URL for your cloud account and a base URL, as in these examples:

When you connect to the console using either of these URLs (explicitly specifying the tenancy when using the latter URL), you will be challenged for an OCI username and password. Once these credentials are provided, you sign in to the console with your local user.

Federated users are created and managed in an identity provider outside of OCI’s IAM service such as Microsoft Active Directory or Oracle Identity Cloud Service (IDCS). The identity provider discussed from here on will be IDCS, but the principles discussed next apply to other identity providers as well.

Provisioned users are automatically created in OCI’s IAM service based on federated users in an identity provider. A provisioned user does not exist without a corresponding federated user. If your tenancy has been federated to another identity provider and you attempt to access the OCI console using the preceding URLs, you will be prompted to either use a single sign-on (SSO) credential or to specify your local username and password. Provisioned users allow federated users to sign in to the OCI console using a password managed by their identity provider—for example, IDCS.

Users have one or more user credentials.

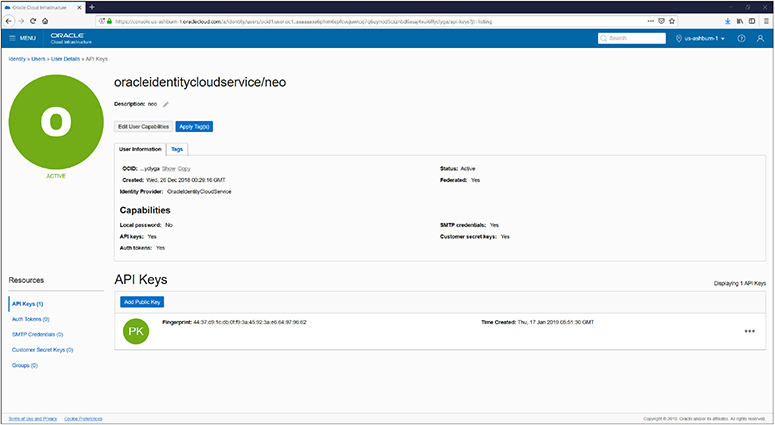

User Credentials

Users connect to OCI using several types of credentials. Your username and password are authenticated when you sign in to the OCI console. When you access a Linux compute instance, you need an SSH key (see Chapter 4) to make a connection to the operating system. Figure 2-4 shows a federated user named neo with a list of user resources on the bottom left, including API keys, Auth tokens, SMTP credentials, customer secret keys, and the number of groups to which the user belongs. Usernames may also be simple names or based on email addresses.

Figure 2-4 OCI user management

An Oracle-generated Auth token is required when authenticating users with third-party APIs that do not support OCI signature-based authentication. Customer secret keys may be used to connect to your object storage bucket with Amazon S3–compatible APIs. This allows you to utilize existing scripts that already work with S3 buckets to interface with your OCI object storage buckets. SMTP credentials are used with the Email delivery service.

Your API signing keys are used for authenticating your user when accessing protected OCI service APIs. You generate a private and public key pair in PEM format and associate the public key with your user. You can then use the private key to access OCI service APIs programmatically through the command-line interface or one of the SDKs (discussed later in this chapter).

User management tasks such as creating or resetting passwords, and restricting or enabling user capabilities, may also be performed by administrators through this console interface.

Groups

OCI users are organized into groups. A user may belong to many groups. When your OCI account is created, a default Administrators group is created. The Administrators group initially has a single member—the user that was created when the tenancy was provisioned. As an administrator, you may create additional administrator users and add them to this group or create other groups for duty separation. The administrator users have complete control over all resources in the tenancy so access to this group should be tightly regulated. It is good practice to set up groups for teams of users who perform similar work.

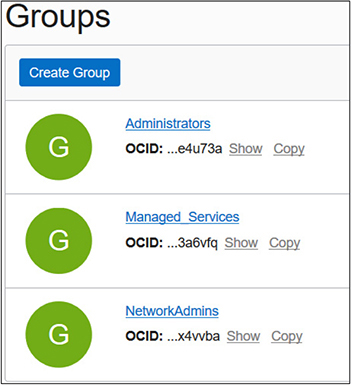

For example, you may have a team of network administrators in your organization that is placed in a NetworkAdmins group. For applications or systems that have data sovereignty requirements, you could create a group of users who reside in a specific locale—for example, Canadian Network Admins. This group could be given permission to manage the network resources in the Canadian HR compartment to meet the data sovereignty requirement. Groups cannot be nested. Figure 2-5 shows the default Administrators group along with two custom groups: Managed_Services and NetworkAdmins.

Figure 2-5 OCI groups

Your nomenclature and group management strategy may already be in place with on-premises resource management, and OCI user and group management may be a natural extension of this system. If a well-defined strategy is not in place, this is an important design decision. The current segregation of your infrastructure and, more importantly, the current partitioning of your human resources into technical teams are often good models on which to base OCI groups. These teams may support specific applications or technologies or different infrastructure layers such as OS, storage, network, Oracle or other databases, or Oracle or other middleware. They may also support specific departments or business units. Aligning OCI group design with your existing human team divisions often simplifies the IAM nomenclature and group management strategy. As the volume of users and infrastructure grows, management of OCI resources inevitably grows in complexity. Groups are that piece of the IAM solution essential for practical, auditable user and infrastructure governance.

Policies

Policies are the glue that determines how groups of users interact with OCI resources that are grouped into compartments. You may want the HR application administrators to manage all resources in a compartment dedicated to the HR department:

Allow group HRAdmins to manage all-resources in compartment HR

This policy statement expressed in simple language is all that is required to authorize the users that belong to the HRAdmins group to manage all resources in the HR compartment. The manage verb is the most powerful and includes all permissions for the resource. The policy statements are submitted as free-form text. As of this writing, there is no tool provided to assist with constructing these policy statements.

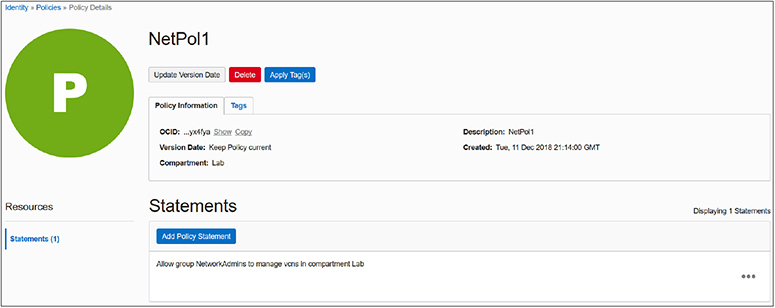

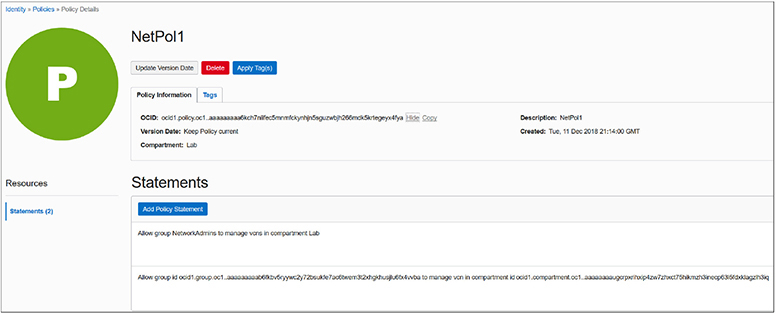

Figure 2-6 zooms into the NetPol1 policy that is created on the VCN resources in the Lab compartment. This policy comprises a single statement but at the time of this writing can contain up to 50 statements. These limits may be modified by requesting a service limit change.

Figure 2-6 Policy to manage VCNs in the Lab compartment

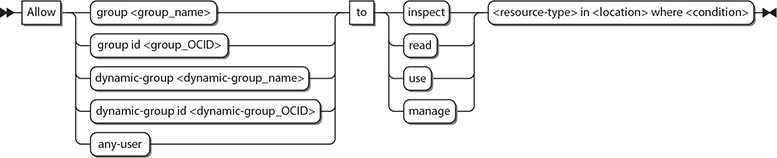

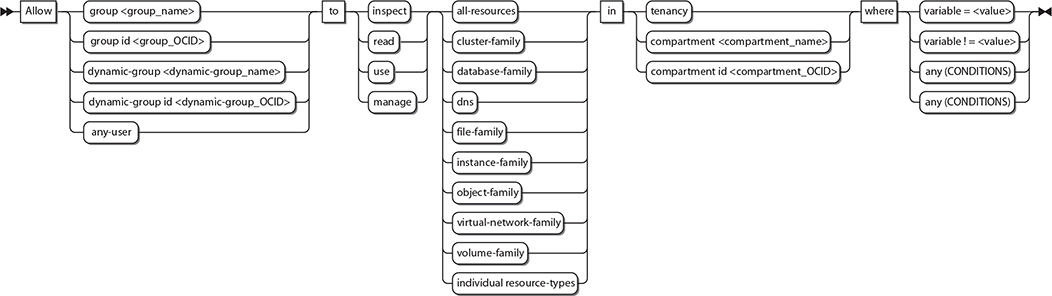

The policy statement follows this syntax:

Allow <subject> to <verb> <resource-type> in <location> where <condition>

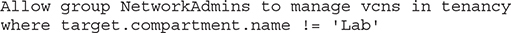

The policy statement in Figure 2-6 references the NetworkAdmins group as the subject, manage as the verb, vcns as the resource-type, and the Lab compartment as the location. There are no where conditions specified but the ability to specify conditions in policy statements supports more sophisticated policy features. For example, you could create a policy on the root compartment with this statement:

This statement grants all permissions required to manage all VCNs in all compartments in the tenancy except the Lab compartment to the users that belong to the NetworkAdmins group.

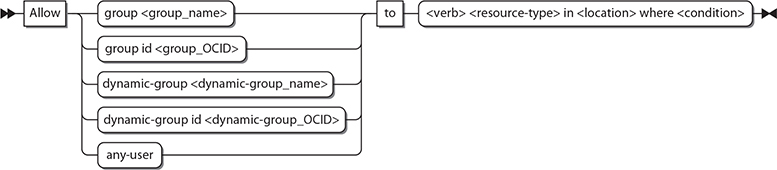

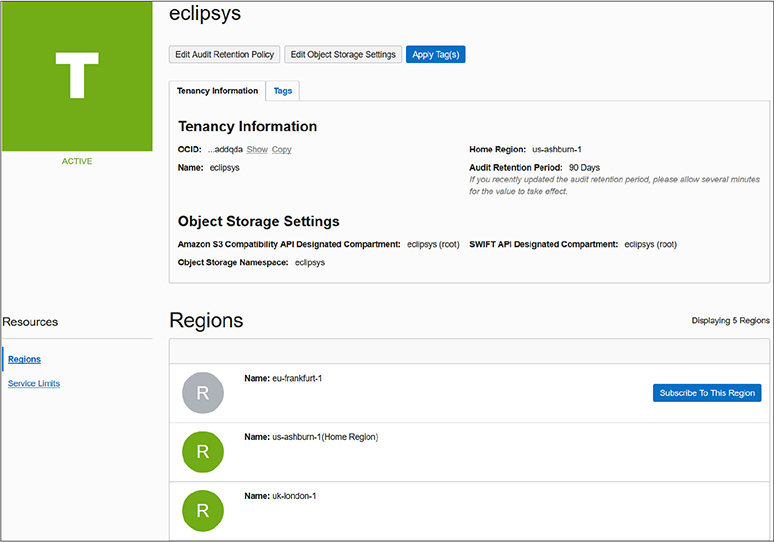

Subjects in the policy syntax specify one or more comma-separated groups by name or OCID. Chapter 1 introduced the unique identifier that each OCI resource is assigned, called an Oracle Cloud ID (OCID). In addition to the group name and group OCID, other valid subjects are dynamic groups (discussed later in this chapter), and a reserved collective noun called any-user, which refers to all users in your tenancy. Figure 2-7 shows the policy syntax expansion for the subject component. The Allow keyword grants permission to one or more subjects to interact with OCI resources. These subjects are currently limited to either all users in the tenancy, one or more groups of users or instances (dynamic groups), or any combination of these subjects.

Figure 2-7 Policy syntax expansion for the subject component

The candidates for subjects, verbs, resource-types, and locations are an evolving list, but the essential terms are articulated in various policy syntax diagrams in this chapter. Figure 2-8 expands the policy verbs: inspect, read, use, and manage, which has been used in examples provided so far. These verbs have a generic meaning that determines your level of access to a resource. The exact meaning of each verb depends on the resource-type it acts upon.

Figure 2-8 Policy syntax expansion for the verb component

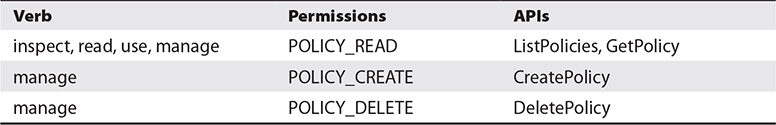

The inspect verb offers the least access to a resource. It provides the ability to list and get resources. This level of authorization is typically reserved for external or third-party limited access to the resource. All resources have a set of APIs (application programmer interfaces) that provide a programmatic interface for dealing with the resource. One or more related APIs are collectively grouped into permissions, which represent an atomic unit of authorization that determines the interactions between users and specific resources.

For example, the object storage buckets resource has two APIs, HeadBucket and ListBucket, covered by the permission BUCKET_INSPECT. The HeadBucket API checks if a bucket exists, while the ListBucket API lists all the buckets in a compartment. When the Financial_Auditors group is allowed to inspect the object storage resources in the Finance compartment, the BUCKET_INSPECT permission in granted internally, which permits users in the group to interface with the resource using the associated APIs. The corresponding policy statement may be

The read verb includes the permissions of the inspect verb and additionally provides access to user-specified metadata about the resource and access to the actual resource. This level of authorization is typically reserved for internal oversight and monitoring. Let’s stay with the example of the buckets resource; consider the following policy statement:

Users in the Financial_Analysts group receive both the BUCKET_INSPECT permission and the BUCKET_READ permission because the read verb includes the permissions of the inspect verb. The BUCKET_READ permission exposes three additional APIs: GetBucket, ListMultipartUploads, and GetObjectLifecyclePolicy. Users in the Financial_Analysts group can access these five bucket-related APIs: HeadBucket, ListBuckets, GetBucket, ListMultipartUploads, and GetObjectLifecyclePolicy.

The use verb cumulates the permissions from the read verb with the ability to actually work with the resource. Let’s continue with the example of the buckets resource; consider the following policy statement:

Allow group Financial_Controllers to use buckets in compartment Finance

Users in the Financial_Controllers group will be granted the permissions that the inspect and read verbs granted, which were BUCKET_INSPECT and BUCKET_READ, as well as the BUCKET_UPDATE permission, which fully covers two additional APIs—UpdateBucket and DeleteObjectLifecyclePolicy—and partially covers PutObjectLifecyclePolicy, which additionally requires other permissions such as OBJECT_CREATE and OBJECT_DELETE. Partially covered APIs are excluded from this discussion. Users in the Financial_Controllers group can access these seven bucket-related APIs: HeadBucket, ListBuckets, GetBucket, ListMultipartUploads, GetObjectLifecyclePolicy, UpdateBucket, and DeleteObjectLifecyclePolicy.

Generally, the use verb permits you to use and update a resource but not to create or delete that type of resource. This level of authorization is typically reserved for end-users of the resource. Bear in mind that these are general guidelines for these verbs and actual permissions vary depending on the resource-types involved. For some resource-types, the update operation is equivalent to the create operation, which is covered by the manage verb, so for these resources, the use verb precludes the update permission. Table 2-1 lists the verbs, permissions and APIs associated with the policies resource-type. Note that the inspect, read, and use levels of permission for this resource-type are identical.

Table 2-1 Permissions, APIs, and Verbs for the Policies Resource-Type

The manage verb includes all permissions for the resource. It effectively combines the read permissions with the abilities to create and destroy the resource-type. It is the highest level of permission that can be granted on a resource-type and is generally reserved for administrator groups. To complete the example of the buckets resource, consider the following policy statement:

Users in the Financial_Admins group will be granted all permissions on this resource, including BUCKET_INSPECT, BUCKET_READ, and BUCKET_UPDATE granted through the use verb, as well as the BUCKET_CREATE, BUCKET_DELETE, and PAR_MANAGE permissions, which cover six additional APIs: CreateBucket, DeleteBucket, CreatePar, GetPar, ListPars, and DeletePar. The latter four APIs relate to pre-authenticated requests discussed in Chapter 5. Users in the Financial_Admins group can access the bucket-related APIs shown in Table 2-2.

Table 2-2 Permissions, APIs, and Verbs for the Bucket Resource-Type

The exploration of the verbs in the policy syntax introduced several new concepts, such as APIs and permissions. These are key building blocks for advanced policy design, which is discussed later in this chapter.

When you create a policy, you are prompted for the policy versioning scheme you would like to use. The options are to Keep Policy Current, which adapts the policy dynamically to stay current with any future changes to the IAM services definition of verbs and resources, or to Use Version Date, which is to limit access to resources based on the definitions that were current on a specific date. It is likely to be a safer bet to use the version date approach on production policies.

Dynamic Groups

A powerful feature closely related to the notion of self-driving, self-tuning, automated systems involves granting groups of compute instances permission to access OCI service APIs. If you require aggregations of compute instances to interface with OCI resources, you create a dynamic group and add compute instances as members. Instances in dynamic groups act as IAM users to provision compute, networking, and storage resources based on IAM policies.

The next section describes resource locations and resource identifiers as well as how they pertain to policy formation.

Describe Resource Locations and Identifiers

Resources are the building blocks of your infrastructure. In data centers all over the world, there are thousands of racks of servers, storage, and networking equipment tethered together with miles of cabling. The OCI software layer abstracts this massive collection of hardware into infrastructure resources in many digestible shapes and sizes. Through interfaces like the OCI console, you can carve out an infrastructure architecture with just the resources you need and with just a few commands. The OCI console, however, is not the only interface you can use to work with OCI.

All resources in OCI have been exposed through REST APIs introduced earlier. Developers can also use several Software Development Kits (SDKs), which are all open source and available on GitHub. These include documentation, online sample code, and many useful tools for interfacing with OCI resources. As of this writing, there are OCI-related SDKs available for Java, Ruby, Python, and Go. Apache Hadoop applications can also use object storage resources through an HDFS connector. The Data Transfer Utility is a command-line tool for facilitating large data transfers and is detailed in Chapter 6. A noteworthy tool is the OCI command-line interface (CLI), which provides the same functionality as the web console and is available on the command line. As we proceed to explore several commonly used resources and their locations, it is instructive to do so using a combination of both the web console and the OCI CLI. The OCI CLI is discussed in detail in Chapter 7. It is not a requirement for you to have the CLI operational at this stage, but if you want to follow along with the examples, feel free to jump ahead to Chapter 7, set up the CLI on your machine, and then proceed with this chapter.

Resource Locations

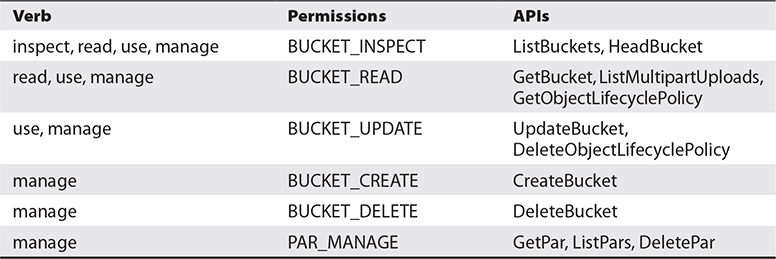

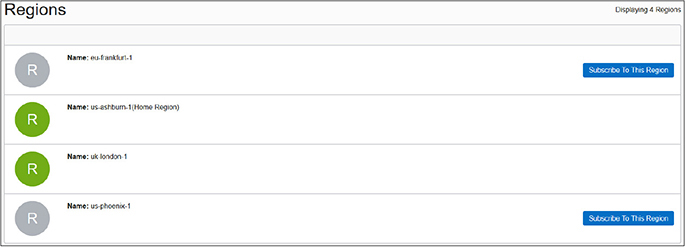

When a cloud tenancy is created, a default data region is chosen. As of this writing, you can choose APAC, EMEA, or North America as your default data region. You should choose the region based closest to your primary cloud users or primary on-premises data center locations. The tenancy is then created in one of the regions. When you log in to OCI, the top-right corner indicates your primary or home region. Choose Manage Regions from the region drop-down list and you see more details about your tenancy. Figure 2-9 shows a tenancy created with a North American default data region and allocated us-ashburn-1 as its Home Region. A home region is important for IAM resources.

Figure 2-9 Tenancy and regions

Global Resources

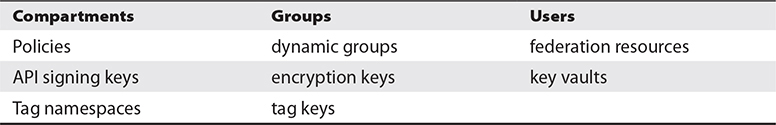

IAM resources such as users, groups, compartments, and policies are considered global resources. A list of global resources is provided in Table 2-3. These resources exist in all regions and availability domains. However, they are initially created in the home region of the tenancy. Here, the master copy of their definition resides. When changes are made to IAM resources, they must be made in the home region and then these changes are automatically replicated to other regions. Changes to IAM resources in the home region typically take a few seconds, while it may take a few minutes for these changes to propagate to all regions. All API changes to IAM resources must use the endpoint for the home region.

Table 2-3 Global IAM Resources

Many organizations have users spread across the globe. You may require OCI resources in other geographical locations, and this is supported by subscribing to one or more non-home regions. Figure 2-9 lists non-home regions with a Subscribe To This Region button. IAM resources are available in the new region but their master definitions always reside in the home region.

Exercise 2-1: Subscribe to Another Region

In this exercise, you will log in to your OCI tenancy, examine your tenancy home region, and subscribe to a new region. The OCI CLI is used in this and many other exercises throughout the book.

1. Navigate to http://cloud.oracle.com and choose Sign In. Select your account type (IDCS or Traditional), specify your cloud account name, authenticate your user, and you should be in the My Services dashboard.

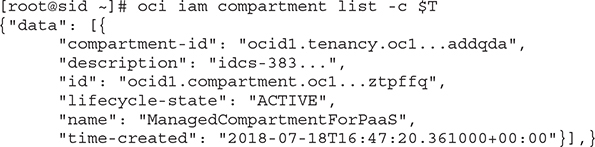

2. Navigate to your compartment list and take note of the compartments. If you have a new cloud account, you should at least have the root and ManagedCompartmentForPaaS compartments.

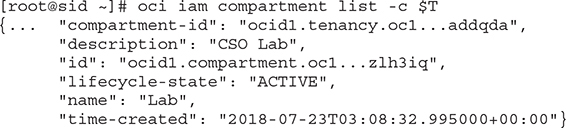

3. An OCI CLI listing of the ManagedCompartmentForPaaS compartment returns this JSON output. Take note that no metadata exists for the compartment that ties it back to a region. For the compartment-id key, a tenancy OCID is listed because compartments are global resources. Note also the OCID (id key value) for the compartment.

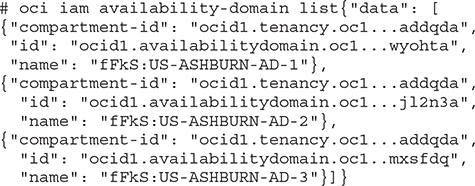

4. Access the OCI console, choose Administration | Tenancy details, and you should see your tenancy details similar to Figure 2-9. The list of available regions may also be retrieved with an OCI CLI command:

5. The home region for the tenancy shown in Figure 2-9 is us-ashburn-1. This region has three availability domains. The OCI CLI output shows the JSON output for this query. Notice that even the availability domain has an OCID.

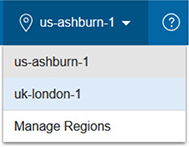

6. In this exercise, you are going to subscribe to a region different from your home region. Choose a secondary region that is sensible for your architecture and click Subscribe To This Region. OCI prompts you if you are sure and once you say OK, your IAM global resources are propagated to the new region. After a few minutes, your new region should be available for use by your tenancy.

7. There is no additional financial implication but be aware that users are allowed to use the new region because they are allowed to use the home region resources unless you explicitly set preventative policies. In the top-right area of the OCI console, the region list of values should now reflect your new region. You may have to refresh your browser to see the updated list. Choose the new region. Navigate to the compartment, group, and policy lists in the new region, and note that they are identical to the views from the home region.

Regional and Availability Domain–Level Resources

Non-IAM resources exist at a region level or at an availability domain level. Remember that a region consists of one or more ADs. An AD is a fault-tolerant data center. If you think about it, when you launch a compute instance, there is either a bare metal or virtual machine running in a data center. The compute instance is therefore an availability domain–specific resource. It exists in a single physical location. A virtual cloud network, however, spans all the ADs in a region and is therefore a regional resource. The following are some examples of region-specific resources:

• buckets

• images

• Internet Gateways (IG)

• Customer Premises Equipment (CPE)

• Dynamic Routing Gateways (DRGs)

• NAT Gateways

• route tables

• Local Peering Gateways (LPGs)

• repositories

• security lists

• volume backups

The ADs in a region are connected by a low-latency high-bandwidth network. It is not surprising that many of the regional resources are network resources. These networking resources are explored in Chapter 3.

Exercise 2-2: Create a Compartment and a VCN

In this exercise, you will log in to your OCI tenancy and create a new compartment in your home region. The compartment in the exercise is called Lab, but you should provide a name that is meaningful in your environment.

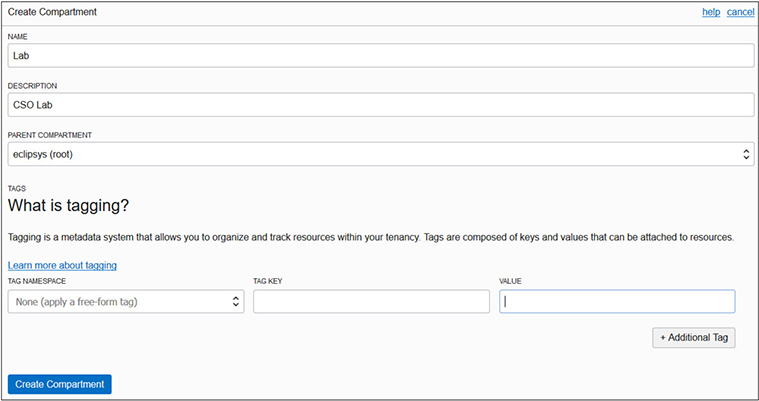

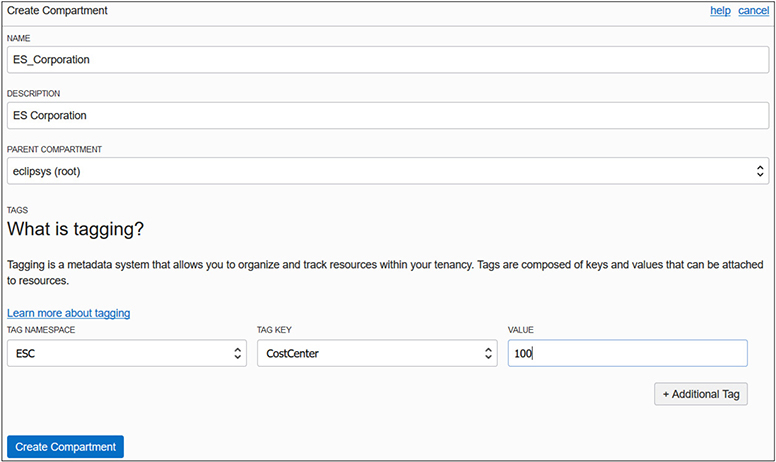

1. Navigate to your compartment list (Identity | Compartments), and choose Create Compartment. Provide a name and a description, check that the parent for your new compartment is the root compartment, and choose Create Compartment. Tagging will be discussed in a subsequent section.

2. After a few seconds, your compartment should be ready. The replication of this IAM resource will begin, and, after a few minutes, this compartment will be visible in your non-home regions as well.

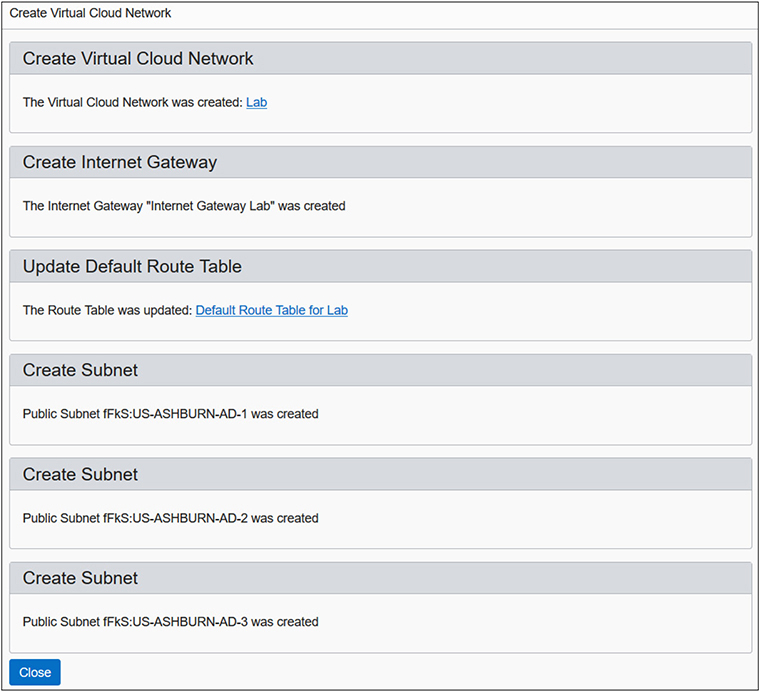

3. Navigate to the VCN list (Networking | Virtual Cloud Networks). Ensure your new compartment is chosen under List Scope on the left, and choose Create Virtual Cloud Network.

4. Provide a name for the VCN. Choose the radio button: Create Virtual Cloud Network Plus Related Resources. The VCN details are explored in Chapter 3. For now, choose Create Virtual Cloud Network.

5. You have created a VCN. In addition, an Internet gateway, route table, and security list have been created in the Lab compartment. These network elements are regional resources. They are available for all ADs in the region to use.

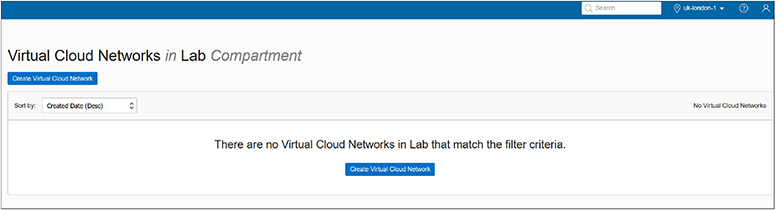

6. Connect to a non-home region and navigate to the Lab compartment. There is no VCN in the Lab compartment in the uk-london-1 region because the VCN is a regional and not a global resource.

7. You can optionally clean up by connecting back to your home region, dropping the VCN in Lab compartment, and deleting the compartment. Bear in mind that after deleting the compartment, it remains visible as a deleted compartment for 60 days. It may be useful to retain a Lab or Sandbox compartment for testing purposes.

After completing Exercise 2-2, you should have one subnet per AD. This is an availability domain–specific resource. Instances created in AD: US-ASHBURN-AD-1 in the Lab compartment (in this example) will be assigned IP addresses from the subnet created in AD: US-ASHBURN-AD-1. These instances will exist only in AD: US-ASHBURN-AD-1. Regional subnets may also be created. Subnets are resources that may be created at an AD or regional level. The following are some examples of AD-specific resources:

• volumes

• database systems

• instances

• ephemeral public IPs

Volumes are storage resources allocated to specific compute instances within the same availability domain.

Resource Identifiers

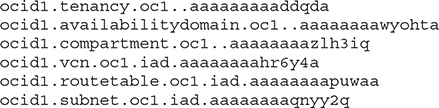

Tenancies, Regions, ADs, Compartments, Groups, Users, Policies, and every other OCI resource is assigned a unique identifier known as an Oracle Cloud Identifier or OCID (sometimes pronounced “o-sid”). OCIDs are required to use the API for OCI. OCIDs are unique across all tenancies.

The OCID is based on this format:

The following are some examples:

The resource-type component is a character string describing the resource. The realm is always oc1 for now and is meant to represent the set of regions that share OCI entities.

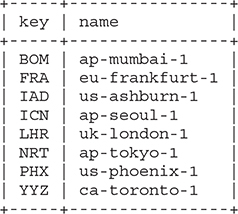

The region segment is blank for global resources such as tenancy and compartments but contains the region code for regional and AD-specific resources. As per Table 2-4, IAD represents the us-ashburn-1 region. Table 2-4 lists several provisioned OCI regions.

Table 2-4 OCI Regions

The future use segment is blank for now, while the unique alphanumeric string completes the OCID. As you have navigated the OCI console, you have inevitably noticed the OCID field alongside virtually every artifact. The OCID is partially displayed and is adjacent to hyperlinks that either Show or Copy the OCID.

Your tenancy OCID may be obtained by logging in to the console and either navigating to Administration | Tenancy Details or choosing Manage regions from the menu next to your home region and selecting the Show link.

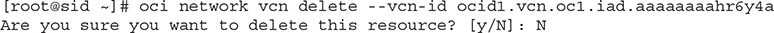

Your tenancy OCID is required to access the OCI APIs through the CLI or the SDKs. For example, the following CLI command to delete a VCN takes its OCID as a parameter to the API to delete VCNs.

Policy statements also use the OCID for IAM resources. Figure 2-10 shows an updated version of the NetPol1 policy created earlier. Here, the Show link has been clicked, exposing the OCID for the policy. Note that it has been replaced by a Hide link adjacent to the Copy link. A second policy statement has been added using OCIDs but these statements are equivalent because the NetworkAdmins group OCID and Lab compartment OCID are referenced in the second statement.

Figure 2-10 Policy statement using OCIDs

The OCI console search feature also uses OCIDs. For example, you can paste in the OCID of a compartment to see a list of all resources that belong to that compartment. Once you have used the search feature, you can select Advanced Search in the simple search results page. The advanced search option has a query language that also uses OCIDs. For example, this search query returns a list of subnets that belong to a specific compartment.

Managing Tags and Tag Namespaces

Tagging is a service available to all OCI tenants by default. Tagging in not an IAM concept but is being discussed here to encourage the best practice of tagging your resources in a planful manner. As your OCI estate expands, resource sprawl is inevitable and tagging from the beginning is a great way to remain organized and in control of your OCI resources.

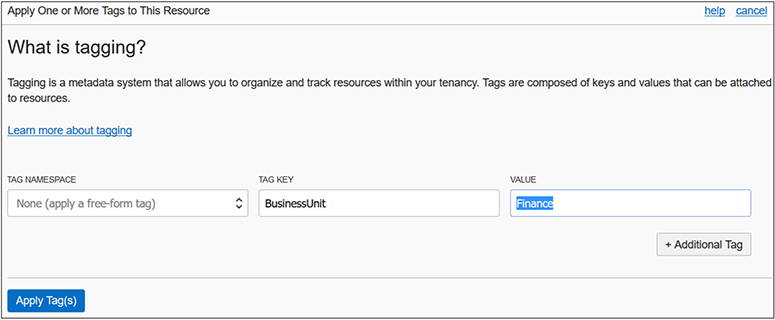

A tag is simply a key-value pair that you associate with a resource. There are two types of tagging: free-form and defined tags.

Free-Form Tags

Free-form tags are limited and offer a pretty basic form of tagging. You can apply as many tags as you want to a resource, but there is a 5-kilobyte JSON limitation on all applied tags and their values per resource.

Figure 2-11 shows a free-form tag with a key called BusinessUnit (no spaces are permitted) and a value of Finance being added to a resource. This particular free-form tag was added to a parent compartment, its child compartment, and an object storage bucket used by the Finance business unit.

Figure 2-11 Creating a free-form tag

Free-form tags can be created, updated, or deleted by users with use permission on the resource. These tags are descriptive metadata about a resource, but they are not subject to any constraints. So typos could easily enter the metadata and affect the reliability of this tagging system. When adding a free-form tag, you cannot see a list of existing free-form tags. Most importantly, you cannot use free-form tags in IAM policies to control access to tag metadata of resources.

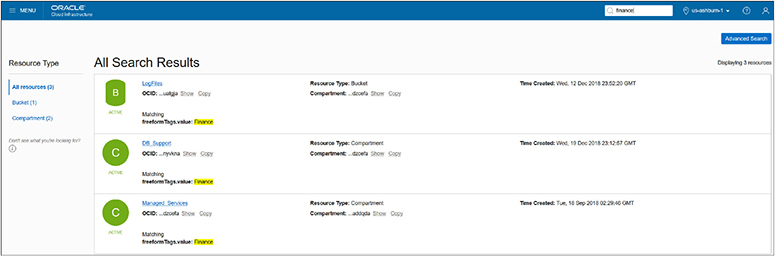

Free-form tagging is best used for demo, proof-of-concept, or tenancies with few resources. Searching for finance using the Search dialog in the console returns the three free-form tagged resources, as shown in Figure 2-12.

Figure 2-12 Search results of resources with free-form tags

Defined Tags

Defined or schema tagging is the recommended enterprise-grade mechanism for organizing, reporting, filtering, managing, and performing bulk actions on your OCI resources.

Defined tags rely on a tenant-wide unique namespace that consists of tag keys and tag values. The tag namespace serves as a container for use with IAM policies.

Consider your existing on-premises infrastructure tracking system. Chances are high that you have a system that factors in departments or lines of business or cost-centers for your infrastructure. You may also want to organize resources by project or team. There is a facility for enabling tags as cost-tracking tags that appear on your invoice, which is very useful for implementing a chargeback system. As of this writing there is a limit of ten tags that may be identified as cost-tracking tags, so factor this into your tag naming strategy.

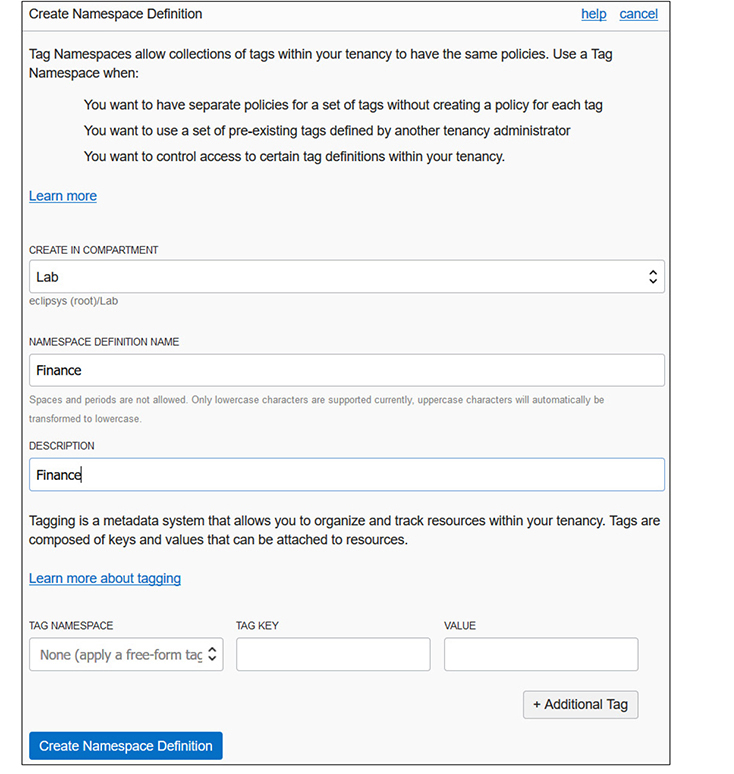

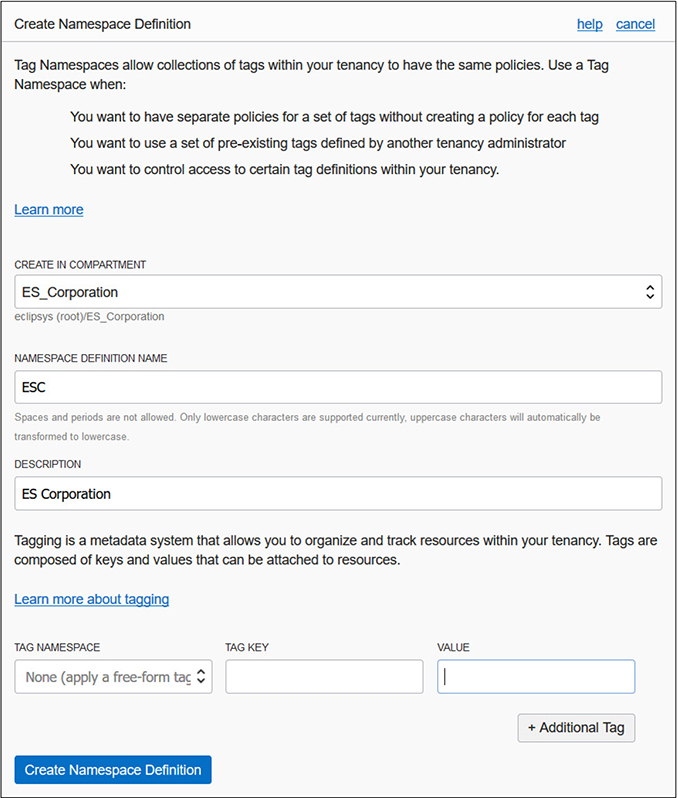

To set up a defined tag schema, you must first create a tag namespace. In the console, navigate to Governance | Tag Namespaces, and choose Create Namespace Definition, as in Figure 2-13 where the Finance namespace is created in the Lab compartment.

Figure 2-13 Creating a defined tag namespace

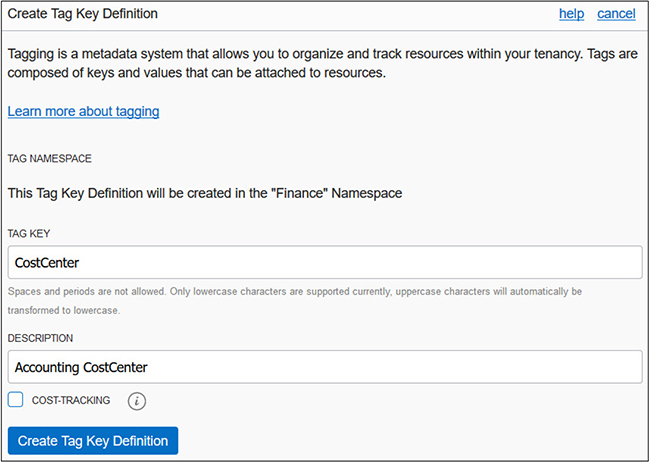

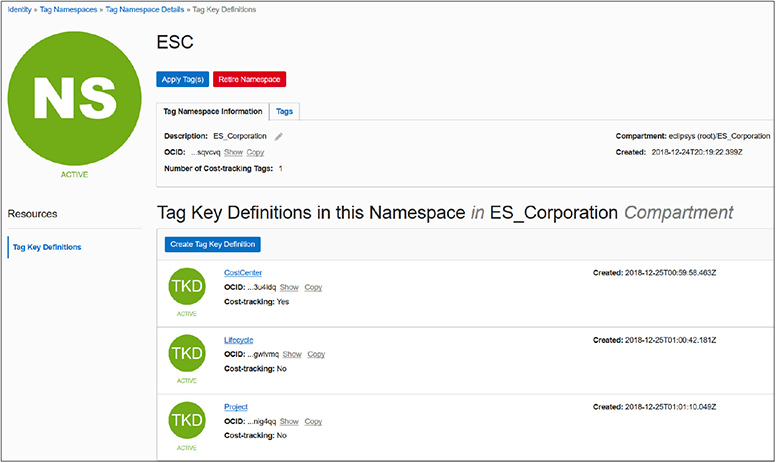

You create your tag namespace in a compartment but the namespace is unique across the tenancy, which means you cannot create another namespace with the same name in another compartment in the same tenancy. To add tag keys to the namespace, navigate to Governance | Tag Namespaces, click the tag namespace, and choose Create Tag Key Definition. Figure 2-14 shows the CostCenter tag being added to the Finance tag namespace. Checking the cost-tracking checkbox converts this tag key into a cost-tracking tag key that you can use to track usage and costs on your online statement in My Services.

Figure 2-14 Create Tag Key Definition

Once you define your tag keys, you can apply these to any resource by navigating to the resource, choosing the tag menu, and choosing the namespace and tag key from a list of values. You are then required to provide just a tag value. This prevents accidental sprawl of many similar but misspelled tags, which is a pet peeve for many administrators. Tags generally refer to defined tags in the documentation. Most resources are taggable, and the list is expanding with the intention of making all OCI resources taggable. You can apply tags with the console, CLI, or SDKs, but usually it is good practice to do so when creating resources. Applying tags does require authorization, and an IAM policy must be created to permit non-administrator users to apply tags. A group can be explicitly given permissions to inspect or view the tag key definitions as follows:

Use permission on both the tag and the resource allows tags to be added, removed, or edited.

Tag key definitions can only be retired, not reused. Resources with retired tags will retain the tag key definitions. These may be manually done per affected resource. The limit of ten cost-tracking tags per tenancy at a time includes both retired and active tags.

Advanced Policies

Armed with an understanding of OCIDs and resource-types, the full power of IAM policies can be expressed. This section discusses aggregate, or family, resource-types, policy location options, and how to use conditions in policies.

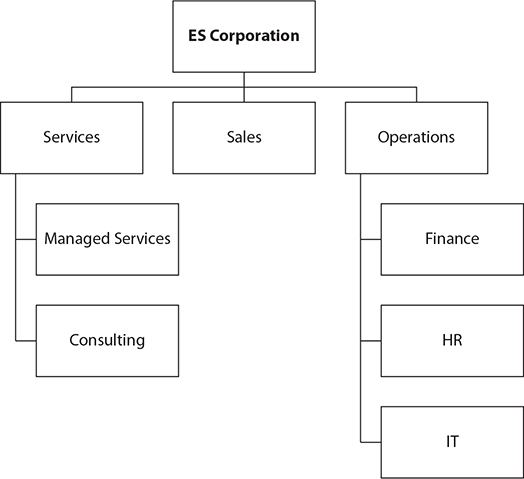

Family Resource-Types

Individual resources may be grouped into collections or families of related resources for ease of management. In Exercise 2-2, a VCN, route table, default security list, Internet gateway, and three subnets were created. All of these individual resource-types belong to the aggregate resource-type called virtual-network-family. Policy syntax can be applied to both individual and aggregate resource-types. Some examples of aggregate resource-types include:

• all-resources

• cluster-family

• database-family

• dns

• file-family

• instance-family

• object-family

• virtual-network-family

• volume-family

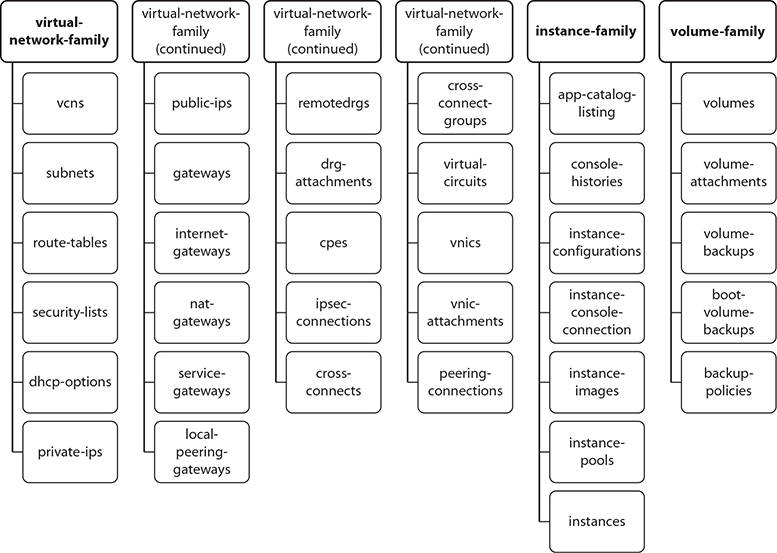

The all-resources aggregate resource-type refers to all OCI resources in your tenancy. The virtual-network, instance, and volume families each consist of many individual resource-types compared to the other aggregate groups. Figure 2-15 expands the virtual-network-family, instance-family, and volume-family aggregate resource-types into their individual resource-types.

Figure 2-15 Virtual-network, instance, and volume family resource-types

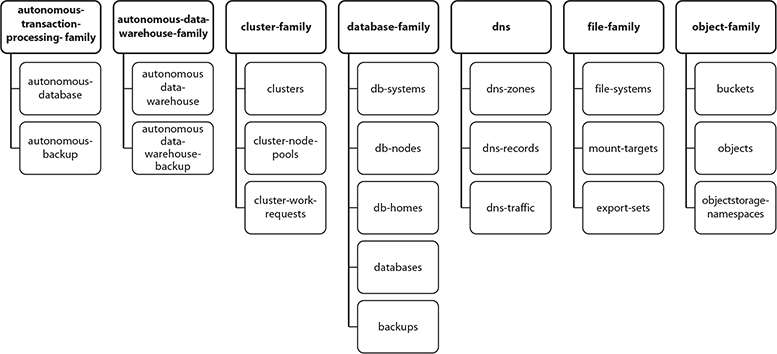

Figure 2-16 lists the individual resource-types for the seven remaining aggregate resource-types: autonomous-transaction-processing-family (ATP), autonomous-data-warehouse-family (ADW), cluster-family, database-family, dns, file-family, and object-family. There may be several unfamiliar resource-types listed but all are covered in later chapters. These diagrams provide valuable context. When you encounter an unfamiliar resource-type, simply look up the family it belongs to in order to understand where it fits in the grander scheme. Figures 2-15 and 2-16 serve as useful reference lookups when designing IAM policies.

Figure 2-16 ATP, ADW, cluster, database, dns, file, and object family resource-types

The policy statement introduced earlier in this chapter followed this syntax:

The subjects and verbs are discussed in detail in the “Policies” discussion in the earlier “Explain IAM Concepts” section. The resource-type component of this syntax may be substituted by any individual or aggregate resource-type, as shown by the expanded syntax diagram in Figure 2-17. Instead of granting manage permissions to over 20 virtual network resources in the Lab compartment to the NetworkAdmins group, you can simply use a single statement:

Figure 2-17 Policy syntax expansion for resource-type, location, and conditions

You can permit your DBAs to manage all organizational databases with this policy statement:

Policy Locations

Figure 2-17 also extends the location component of the policy syntax to include compartment OCID in addition to compartment name and tenancy. An example of this was shown in Figure 2-10, where the Lab compartment is referenced in a policy statement using its OCID.

Policy Conditions

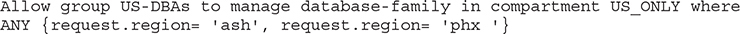

You may specify conditions on policy statements to have finer-grained control over your resources. Policy conditions use one or more predefined variables that you reference in the “where clause” of the policy statement. The following policy statement permits members of the US-DBAs group to manage all database resources in the US_ONLY compartment, as long as the group member makes a request from either the Ashburn or Phoenix regions.

Refer to the conditions “where clause” in Figure 2-17. The policy syntax allows conditions to test the equality or inequality of a variable or whether any of a set of conditions is true or whether all conditions in a set of conditions are true.

Table 2-5 summarizes the variables allowed in policy conditions.

Table 2-5 Variables Allowed in Policy Conditions

Create IAM Resources

It is time to get your hands dirty with the IAM concepts introduced previously. This section is devoted to the practical tasks associated with creating IAM resources for a fictitious company, ES Corporation. You can play along in a trial or sandbox cloud account, or using your organization’s OCI account. You just need a user in the Administrator group. Feel free to change the IAM resource names in the following exercises to align with your current naming standards and structures.

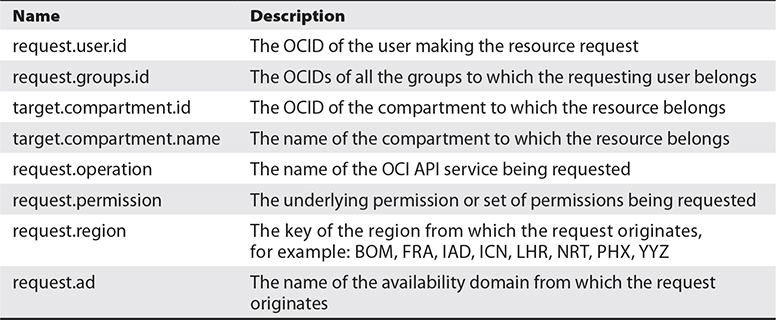

ES Corporation is an IT company with two primary lines of business: Infrastructure and Services. There are Sales, Services, and Operations business units. The Services business unit is further divided into Managed Services and Consulting Services, while the Operations business unit is divided into the HR, Finance, and IT departments. The business has offices in San Francisco (US) and London (UK). The IT department manages the infrastructure through a team of application, network, storage, systems, security, and database administrators based in each location working in local on-premises data centers. ES Corporation has decided to embrace Oracle Cloud Infrastructure and needs your help to design an efficient architecture that optimizes human and infrastructure resources. Learning from historical budget cycles, the new infrastructure must provide a mechanism to understand utilized infrastructure by respective departments.

Create Compartments

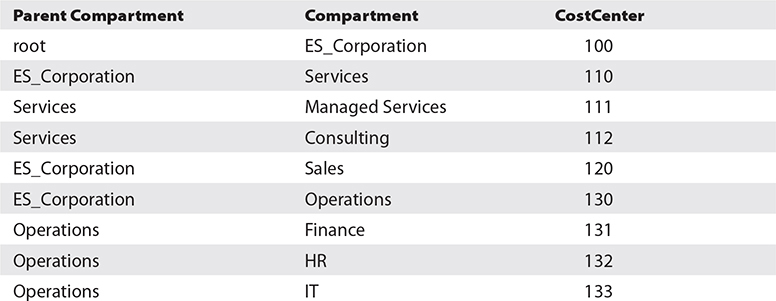

After careful business analysis, you conclude that all the departments should have a dedicated compartment to host resources specific to their needs. Shared resources will be located in the parent compartment at the organization-level compartment.

Exercise 2-3: Create Compartments for Organization

In this exercise, you will create compartments for the organization, each of the three business units, and their departments.

1. To ease management of these compartments but specifically to fulfill the mandate to track resource utilization by departments, a defined tagging schema should be configured. Navigate to Governance-Tag Namespaces and select Create Namespace Definition. Ensure that the newly created ES_Corporation compartment is chosen. Provide a name, say ESC, and a description, and select Create Namespace Definition.

2. With a tag namespace in place, tag keys should be defined. Navigate to Governance-Tag Namespaces-ESC and select Create Tag Key Definition. Create a tag key called CostCenter with an appropriate description, check the cost-tracking checkbox, and select Create Tag Key Definition. Repeat this step to define two additional non-cost-tracking tag keys: Lifecycle and Project.

3. Navigate to Identity-Compartments. Choose Create Compartment. Provide a name for the organization, say ES_Corporation, and a description, and ensure that its parent compartment is the root compartment. Tag the compartment by choosing the ESC namespace, tag key CostCenter, and tag value 100, and then select Create Compartment.

4. Use the details in the following table to create the remaining subcompartments of the ES_Corporation compartment.

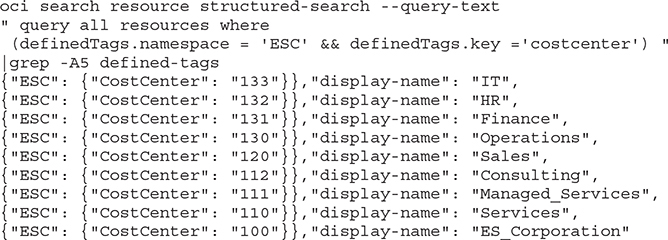

5. You have just created nine new compartments. Search your resources for the defined tag costcenter using the OCI CLI. The following output is truncated for brevity:

Create Groups, Users, Policies

A set of compartments mapping onto the organizational chart neatly partitions business unit and departmental resources. The challenge now is to create groups of users who manage or administer your OCI infrastructure. If there are existing infrastructure teams managing on-premises infrastructure, the path to the cloud is often more direct than you imagine. On-premises network administrators often already understand networks, subnets, route table, security lists, and other network resources. The cloud version of network resources closely resembles their on-premises counterparts. This principle is generally true for all OCI resources.

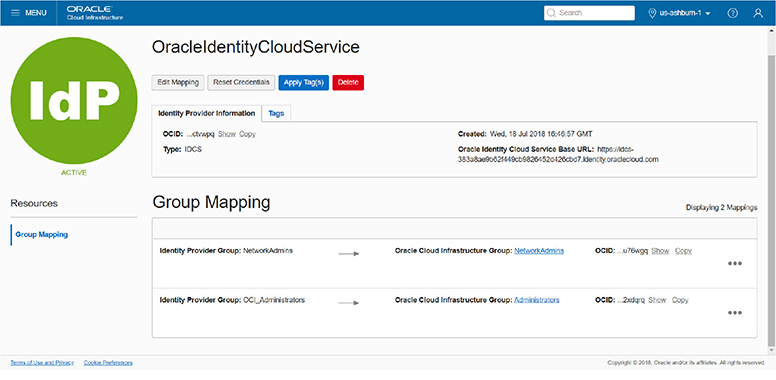

Exercise 2-4: Create Groups, Users, and Policies

In this exercise, you will create groups of administrators (local users) that parallel the on-premises teams. The IT department currently manages the infrastructure with a team of application, network, storage, systems, security, and database administrators based in each location working in local on-premises data centers.

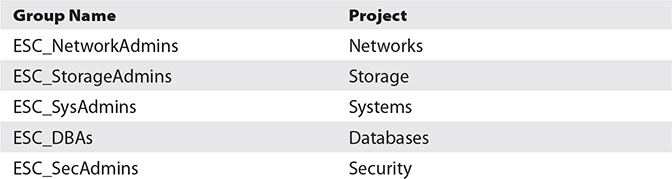

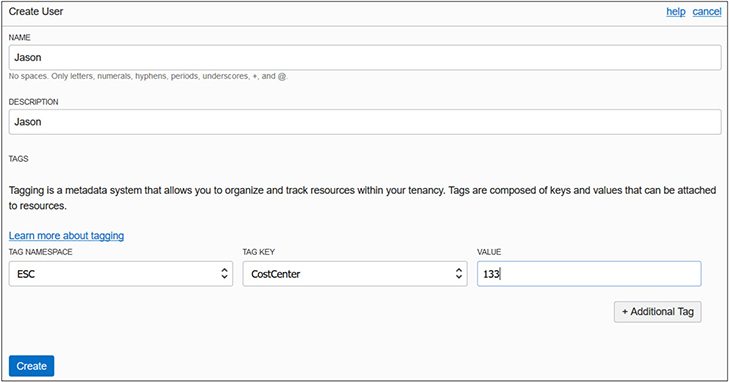

1. Navigate to Identity-Groups and select Create Group. Provide a name and description and select the Project tag key from the ESC namespace, supply the appropriate key value, and click Submit. Create the five groups you see in the following table:

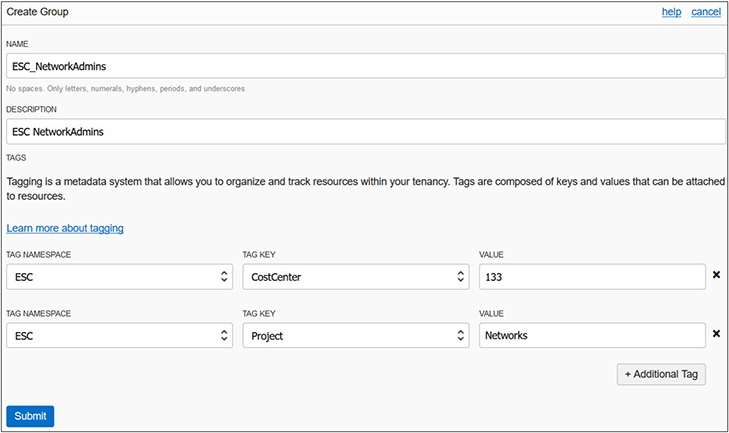

2. In this exercise, you have begun the construction of an IAM framework with compartments and groups. To illustrate the process of creating local users, a single user is created and added to the ESC_NetworkAdmins group. Feel free to substitute any meaningful username and to create additional local users in your environment. Navigate to Identity-Users and select Create User. Provide a name and description, select the CostCenter tag key from the ESC namespace, supply the appropriate key value, and click Create. The user Jason was created with ESC.CostCenter=133.

3. Jason is the lead network engineer and is often consulted with regard to operating systems hardening as well as network penetration testing. It is necessary that he has management level access to these resources. Jason will be added to three groups: ESC_NetworkAdmins, ESC_SysAdmins, and ESC_SecAdmins. Navigate to Identity-Groups-ESC_NetworkAdmins and select Add User To Group. Choose user Jason and choose Add. Repeat these steps for adding Jason to the ESC_SysAdmins and ESC_SecAdmins groups.

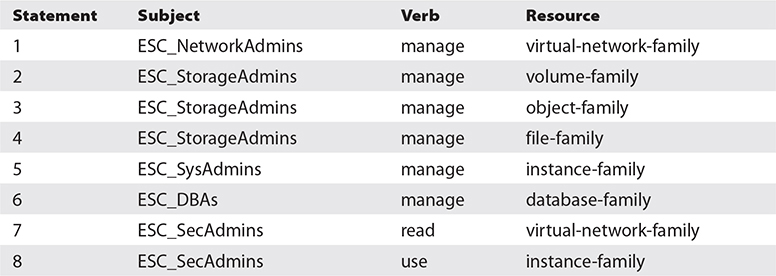

4. The admin groups now require permissions to access OCI resources. Navigate to Identity-Policies and select Create Policy. Provide a name and description. To keep the policy current as OCI changes occur, choose the Keep Policy Current radio button and add eight policy statements in the ES_Corporation compartment as per the following table. Notice that family resource-types are being used instead of many statements for each individual resource-type. Also, each group has manage privilege on respective resources for the parent compartment ES_Corporation. This policy will be inherited by all subcompartments.

5. Your security design for infrastructure is now complete. You can log in as Jason and should be successful in managing network resources in the ES_Corporation compartment and all its child compartments.

6. Within the corporation there are usually one or more applications deployed, for example the HR application. It usually requires resources such as a network, web servers, databases, compute instances and block storage. If these resources are created and tagged in the HR compartment, the administration framework you just created supports the administration of the HR resources with no further modification because the policy ESC_ITPol1 is inherited by the HR compartment. It may be useful to group your applications and create compartments for infrastructure resources used by these applications.

Federate OCI with Various Identity Providers

The discussion concerning users earlier in this chapter introduced three types of users: local, federated, and provisioned. Usernames and passwords, groups, and group membership are managed either through OCI’s IAM service or through an external identity provider (IdP). OCI supports federation with Oracle Identity Cloud Service (IDCS), Microsoft Active Directory (through AD Federation Services), and any IdP that supports the Security Assertion Markup Language (SAML) 2.0 protocol such as Okta and Oracle Access Manager (OAM).

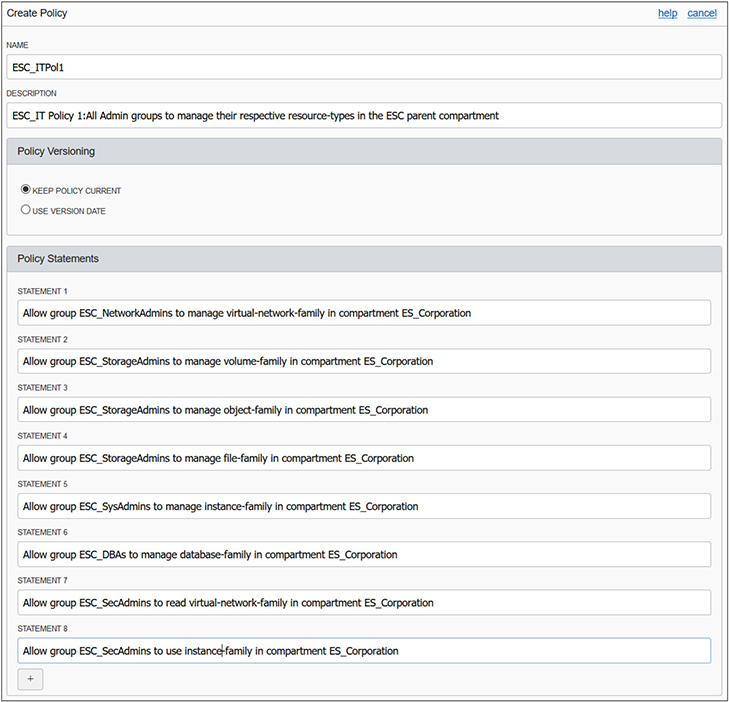

If your tenancy has been federated to another identity provider and you attempt to access the OCI console, you will be prompted either to use a single sign-on (SSO) credential or to specify your local username and password. Figure 2-18 shows that once you try to access OCI using a tenancy federated with IDCS, you can choose to be authenticated through local user authentication (OCI IAM service) or through SSO authentication, which redirects your connection to the third-party identity provider (IDCS), challenges you for credentials, authenticates you, and grants you access to OCI.

Figure 2-18 SSO sign-in for federated users

To standardize user provisioning across discrete identity providers, an IETF protocol called SCIM (System for Cross-domain Identity Management) is implemented in OCI. A consequence of this standard is that users are synchronized automatically between IDCS and OCI IAM. A synchronized or provisioned user is automatically created in OCI’s IAM for each federated user.

User Neo is created in IDCS in your federated tenancy. A few minutes later, a synchronized or provisioned user named oracleidentitycloudservice/neo is automatically created in OCI IAM. Local OCI users have several capabilities, including:

• Using a local password for direct console access

• Adding API keys to the user profile for programmatic access to OCI APIs

• Generating Auth tokens (previously known as Swift passwords) for third-party API authentication

• Generating SMTP credentials to access the Email service

• Generating Customer secret keys (previously known as Amazon S3 Compatibility API keys)

Synchronized or provisioned users from non-OCI IAM providers have all the capabilities listed except for a local password for direct console access. Passwords for federated users are managed by the external identity provider. One of the benefits of federation is that users are managed in a single directory service and trust is established between the local and remote identity providers. Typical federated tenancies tend to not have many local users.

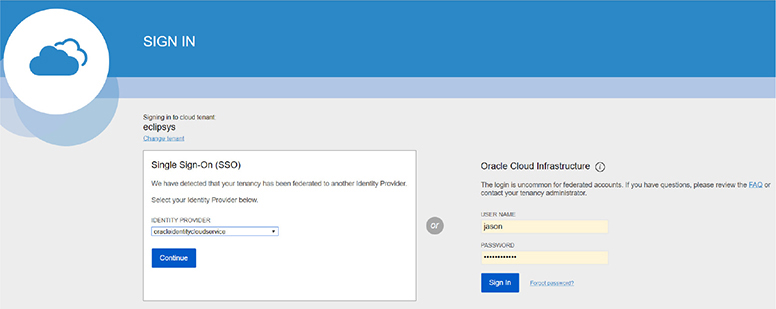

While users are directly synchronized, groups are not. In OCI IAM, an Administrators group is created during the tenancy setup process. When federating to IDCS, an OCI_Administrators group is mapped to the OCI IAM Administrators group. IDCS users appear in the IDCS OCI_Administrators group, but they are not listed in the OCI IAM Administrators group. If an IDCS user who belongs to the OCI_Administrators group signs in to OCI, they have full administrator access to the tenancy.

Figure 2-19 shows the group mappings defined between OCI IAM and IDCS. There are two IDCS groups, OCI_Administrators and NetworkAdmins, that are mapped to the OCI IAM Administrators and NetworkAdmins groups respectively.

Figure 2-19 Map identity provider groups to OCI groups.

IDCS user Neo is a member of the IDCS NetworkAdmins group. His synchronized or provisioned OCI IAM user account, oracleidentitycloudservice/neo, is not a member of the OCI IAM NetworkAdmins account…not directly anyway. Neo logs in to OCI, is authenticated by IDCS, and connects to the OCI console. A policy exists allowing members of the OCI IAM group NetworkAdmins to manage vcns in the Lab compartment. Neo attempts to create a vcn in the Lab compartment and is successful. This is due to the IDCS group mapping setup.

At the time of this writing, users who belong to more than 50 identity provider groups cannot be authenticated to sign in to the OCI console.

A high-level description of the process an administrator follows to federate OCI IAM with a supported identity provider (IdP) is outlined next:

• Through the OCI console, obtain the federation metadata required to establish a trust relationship with the IdP. This typically involves downloading the federation metadata document by navigating to Identity | Federation and choosing the link named: Download this document.

• Configure OCI as a trusted application in the IdP.

• In the IdP, assign users and groups to use with the new OCI application.

• Through the IdP interface, obtain the federation metadata required to establish a trust relationship with OCI. This typically involves downloading the federation metadata document from the IdP.

• Federate the IdP with OCI by adding the IdP to your tenancy and mapping IdP groups to OCI IAM groups

The federated users can then be provided with the tenant name and a console URL; for example:

Set Up Dynamic Groups

A robust feature closely related to the notion of self-driving, self-tuning, automated systems involves granting compute instances permission to access OCI service APIs. Automation technologies are abundant and many systems are designed to behave autonomously, scaling up and down as resources are required with no human intervention. To support this automation, OCI offers dynamic groups.

Dynamic groups are a tenancy-wide construct and represent a collection of compute instances added to the group by one or more matching rules. A typical matching rule is to include all compute instances that belong to a certain compartment. The group becomes dynamic as instances in that compartment are launched or terminated. A single compute instance may belong to a maximum of ten dynamic groups.

Matching rules that determine the inclusion or exclusion of instances in dynamic groups are based on one or more of the following:

• Compartment OCID

• Compute instance OCID

• Tag namespace and tag key

• Tag namespace, tag key, and tag value

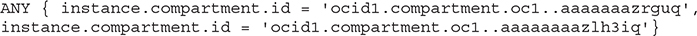

The following matching rule will include any instances that are running in either of the specified compartments with matching OCIDs.

The matching rules can be simple and use equality operators like the preceding example or the inequality operator (!=). The ANY keyword allows matching rules to add an instance to the dynamic group if any of the comma-separated criteria are true while the ALL keyword demands that all comma-separated criteria must be true before an instance is added to the group. The following matching rule uses a defined tag:

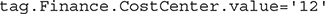

This defined tag with a value of 12 could be applied to any number of compute instances in your tenancy. These groups are dynamic because their membership is dynamic. Figure 2-20 shows how you create dynamic groups in the console by navigating to Identity | Dynamic Groups and selecting Create Dynamic Groups. You provide a name and description and one or more matching rules. You can type these in manually or launch the Rule Builder to help construct matching rules. The Rule Builder is quite limited as it cannot reference defined tags at the time of this writing

Figure 2-20 Create dynamic groups.

Once your dynamic rules are in place, IAM policies must be defined to authorize the dynamic group to interact with one or more resources. Figure 2-17 exposed the policy syntax diagram. Notice that dynamic groups may be referred to by their name or OCID in policy statements.

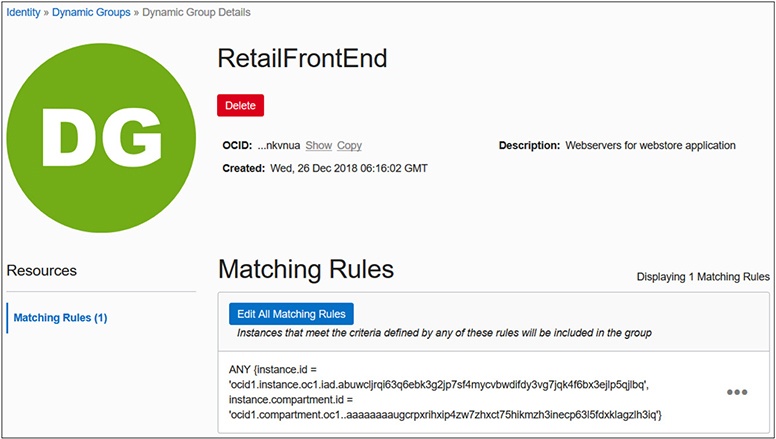

Consider a webstore application that is front-ended by a load balancer that directs traffic to a backend HTTP server running on a compute instance. During busy shopping days, administrators wait for the load on the webstore application to inevitably spike and bring down the system. Additional HTTP servers help with the load issue. So the following policy statements are implemented:

This policy authorizes compute instances that belong to a dynamic group called RetailFrontEnd to provision additional HTTP servers and load balancers automatically as required if unusual load conditions are encountered.

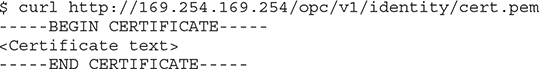

It is not the instances themselves that perform the provisioning but rather applications running on the instances. These applications use either the OCI CLI, Terraform, SDKs, or other interfaces to directly access the OCI APIs once the instance principal is enabled. The instance principal is the IAM service that authorizes instances (to behave as actors or principals) to interact with OCI resources. Each compute instance has a unique identity and it authenticates with OCI when making API calls by using certificates that are automatically added to the instance. These certificates are short-lived for security reasons and are frequently rotated automatically. This avoids the distribution of named credentials to your compute instances and is much safer. The current certificate may be queried from your instance using this command:

OCI CLI scripts on instances in dynamic groups enable the instance principal authorization as follows:

Once the required resources and policies are set up, an application running on an instance in a dynamic group can call OCI API services without requiring user credentials or configuration files.

The following OCI services support access by instances:

• Compute

• Block volume

• Load balancing

• Object storage

• File storage

Because dynamic groups of instances operate in an application-driven manner, there are detailed audit logs captured that enable you to determine all resources accessed by instances in dynamic groups.

Chapter Review

Understanding OCI IAM is key to successful cloud adoption and forms the basis for the remainder of this book. In this chapter, the relationship between many IAM concepts were explored. At the core of OCI are resources grouped into resource family aggregations. Resources reside at a tenancy level or in a compartment. Compartments and their hierarchical nature were discussed as well as the consequential inheritance of policy from parent compartments to child compartments. IAM resources such as users, groups, dynamic groups, policies, and compartments are global and exist in all regions your tenancy is subscribed to, but are mastered in your home region. This means that changes to these global resources are made in the home region first, before being replicated to other regions.

Some resources exist at a region level while others exist at an availability domain level. Regardless of the resource location, they all have a unique identifier, the OCID. OCIDs are used in policy statements, in matching rules for dynamic groups, and in API calls.

The chapter introduced tagging, and although it is not examinable, it is a practical and useful mechanism for controlling and reporting on infrastructure utilization. Policies occupied a substantial chunk of this chapter. Policies are extremely powerful and have been implemented in OCI with a simple, clear syntax.

The chapter also explored federation with various identity providers. Because IDCS federation is standard with all new tenancies, this is likely to be the dominant identity provider you will encounter. The chapter wrapped up by introducing the mechanics of dynamic groups. Dynamic groups support a robust brand of automation and self-regulating systems that are likely to be the norm in the future.

Questions

1. Which IAM resources are global and span regions?

A. Compartments

B. Policies

C. Compute instances

D. DBAAS

2. Which policy verbs authorize groups to interact with resources with the highest level of permission?

A. inspect

B. read

C. administer

D. use

3. Which policy verbs authorize groups to interact with resources in order from lowest to highest level of permission?

A. inspect, read, manage, use

B. inspect, read, use, manage

C. inspect, read, administer, use

D. inspect, read, use, administer

4. Which is a capability of OCI users but not federated users?

A. Can add API keys

B. Can generate Auth tokens

C. Can use a local password for console access

D. Can generate customer secret keys

5. Which of the following statements is true?

A. Region subscriptions occur at the AD level.

B. Region subscriptions occur at the compartment level.

C. Region subscriptions occur at the group level.

D. Region subscriptions occur at the tenancy level.

6. Instances are added to dynamic groups based on what rules?

A. Policy statements

B. Matching rules

C. Compartment OCID and Auth token

D. Inheritance

7. Matching rules that determine the inclusion or exclusion of instances in dynamic groups are based on one of more of the following?

A. Compartment OCID, Instance OCID, tags

B. Instance shape, system load

C. Tenancy OCID, Region OCID, AD OCID

D. Policy syntax

8. Where is a federated user in your tenancy authenticated?

A. OCI IAM service

B. IDCS

C. The identity provider where it was created

D. Active Directory Federation Services

9. Which resource is not an availability domain–level resource?

A. Compute instance

B. Subnet

C. Block volume

D. Object storage

10. What is the name given to the location where the master copy of OCI IAM resources are located?

A. Home region

B. Primary IAM site

C. Identity provider

D. Tenancy

Answers

1. A, B. Compartments, users, groups, and policies are global resources and span regions. When you create these IAM entities, they exist in all regions to which your tenancy or cloud account has subscribed.

2. D. The verbs to authorize groups to interact with resources in order of lowest to highest levels of permission are inspect, read, use, and manage.

3. B. The verbs in order of lowest to highest levels of permission are inspect, read, use, and manage. There is no administer verb in the policy syntax.

4. C. Federated users have to use credentials from their identity provider to sign in.

5. D. The region subscriptions occur at the tenancy level. All IAM resources, including policies, are available in all regions to which your tenancy has subscribed.

6. B. Matching rules determine the inclusion or exclusion of instances in dynamic groups.

7. A. Matching rules that determine the inclusion or exclusion of instances in dynamic groups are based on one or more of the following: compartment OCID, compute instance OCID, tag namespace and tag key, and tag namespace, tag key, and tag value.

8. C. Federated users are authenticated in the IdP where they were created.

9. D. Object storage buckets are an interesting regional resource. An instance in AD: US-ASHBURN-AD-1 may access a bucket in the region: us-ashburn-1. This bucket is equally accessible by another instance in AD: US-ASHBURN-AD-2. Given the correct region-specific object storage URL and permissions, this bucket is accessible from any location.

10. A. IAM resources are available in all regions you have subscribed to but their master definitions always reside in the home region.