10

The Voice

FOR MOST OF MY CAREER, I’ve worked primarily with singers—maybe 70 percent of my practice—because of my connection with Joan Lader and other body-oriented voice teachers and my general interest in the voice. Since most of what is required for the vocal structures, and thus the voice, to be free and avoid injury is simply for the rest of the body to be free and open, singing has proved to be a useful arena for me to develop some of my ideas. This chapter is written specifically with singers in mind. However, the material is useful for nonsingers as well, because the body affects the voice, and the voice is an expression of the whole body.

Anyone who uses his voice a lot will notice that even slightly poor posture and alignment will be reflected in his voice. It is like being an athlete in that you need to be in top physical condition to use your voice excessively and not damage it. If the muscles of expression such as the throat, jaw, tongue, and diaphragm, mostly in the front of the body, are being asked to take on the role of support, there will be excess vocal tension and strain. Most of what we do with our bodies in everyday life reinforces these habits, so it takes conscious awareness and engagement of the muscles of support—mostly the deep core muscles attaching to the spine, transverse abdominis, multifidis, the back of the body, and the pelvic floor—to support the spine, throat, diaphragm, jaw, and head so they can be free for expression.

Just as everyone can benefit from this chapter, singers and speakers can benefit from the other chapters in this book, particularly those dealing with the exercises for the deep core muscles, most of which are applicable to singing. The postural muscles can be difficult to feel, so it may take time to learn to use them correctly. With patience you can gain support for free vocal expression.

Any tension in the body, any fixity or distortion, is going to show up somewhere in the voice. When a singer, or anyone else for that matter, calls me for an appointment, my first diagnosis is usually based on the sound of her voice on the phone. The telephone can be deceptive, of course, and I wouldn’t diagnose whole-body issues that way. But initially, at least, it can give me a lot of valuable information. All of us should listen to our voices on a recording and evaluate our physical and emotional state through the speaking voice. Since the speaking voice, which of course is an issue for all of us, is the basis of the singing voice, let’s look at, or rather listen to, how the sounds we make can be an expression of ourselves.

Good vocal production requires proper support in the lower body, and a relaxed upper body, specifically the rib cage, jaw, tongue, and muscles connected to the larynx. The structure of the torso and throat repeat each other. The larynx, ultimately responsible for all our sound, is dependent on the alignment, strength, and flexibility of the surrounding musculature, just as the organs of the torso depend on the strength of our core abdominal muscles. Support needs to come from the back; the entire back of the body from the heels to the top of the head, and from the pelvic floor, which supports the spine and the breath. The latissimus dorsi and serratus anterior muscles must be strong to support the rib cage and breathing properly. These muscles strengthen the sides of the body and anchor the shoulder blades.

Strengthen the Latissimus Dorsi and Serratus Anterior Muscles

Strengthen the Latissimus Dorsi and Serratus Anterior Muscles

To strengthen and identify these muscles, stand facing a wall, two or three feet away.

- Place your palms flat against the wall, as though you were pushing it away from you. Make sure your shoulders stay down throughout the exercise.

- Gently push into the wall with your palms, being aware of the sides of your rib cage, especially around the armpit. Do not push so hard you lose the sensation there.

- Hold for 10 to 15 seconds, repeat 4 times.

VOCAL SUPPRESSION

All of us, singers or not, have vocal tension—lots of it—and we’re usually unaware of it. Vocal control, as in learning the muscular patterns that shape language, is a part of education and should not create any tension. However, at around age five or six at the latest, when children go to school and are expected to be “teachable,” vocal tension and eventually suppression begin. Of course, we can’t have little Johnny yelling his lungs out so none of the other kids can be heard. Temporary suppression of the desire to yell is simply learning self-control. However, there is an internal suppression that, I believe, has more to do with emotional expression. It’s usually crying and tears that are held in by contracting the tongue and the throat (soft palate), and when a client gets bodywork, often the first expression that comes out is tears.

I remember my son coming back from school, telling me, “Why aren’t boys allowed to cry and girls are? It’s so unfair.” I was shocked, because he was right. Nobody told him directly, but he picked up from his peers and teachers that he should suppress his crying. From then on, he did, despite my telling him that boys need to cry. And of course, girls aren’t really that lucky, as we know; they are expected to suppress their feelings, too.

The voice has the interesting characteristic, like breathing, of being half unconscious, half conscious. We should be able to yell and scream powerfully without getting hoarse and running out of air. Yet most of us, singers or not, have a significant degree of vocal suppression. These habits, which are mostly detrimental, become unconscious. The habits become part of us and cause strain. When I work on people, they quite often release emotions through sound—yelling and screaming—and usually they do not get hoarse afterward, as the efficient, natural sound of the voice is released in tandem with the physical release.

The physical areas that hold tension and reflect vocal suppression are, principally, the diaphragm, the soft palate, the tongue, and the TMJ (temporomandibular joint). You can experiment with these places yourself by manipulating and massaging them, which we will discuss throughout this chapter. In terms of kyo/jitsu (see here), the line of energy between the pelvic floor and the soft palate and the deep core and back muscles are kyo, and the diaphragm, jaw, and laryngeal elevators are usually jitsu. That central channel can be blocked because of tightness, weakness, and imbalance anywhere in the body. The more you can energize and connect the pelvic floor and the soft palate, aligning the soft palate over the center of your pelvic floor, the more the other areas holding tension can let go.

It is important to be able to manually release the muscles that most directly affect the voice because the same muscles are used in daily life for mostly unconscious processes such as swallowing and breathing. For example, normally in swallowing, the larynx raises as the soft palate depresses, and this is also part of the “gag reflex.” We train singers to manually learn to release and lift the soft palate, through direct manipulation, so that the soft palate can raise as the larynx stays released, which is what is needed for optimal use of the singing voice.*5

The throat and jaw are areas that can be difficult to consciously release, and physical manipulation of the musculature can help to bring them into awareness. It is much easier to release using vocal exercises, visualizations, and so on once the body knows what it feels like to be free of tension. Tensions held for decades feel “normal” and often it is not until they release through bodywork, or by another means, that they are even felt. It is beneficial if you can find a bodywork practitioner to work with who understands the vocal structures; however, there is a lot you can do on your own.

Retraining the Breath

The number one problem most singers have is that they breathe incorrectly, usually tightening their ribcages and obstructing the natural movement of the diaphragm and the lungs, creating unnecessary tension and actually limiting the airflow. To release the breath, and effect change in the power of the voice, preventing “pushing” and overuse of the more delicate small muscles of the mouth and larynx, we must free and strengthen the intercostal muscles first, then release tension that obstructs the movement of the diaphragm. This technique is described here in the previous chapter on Breathing.

You’d think that after undergoing a great deal of training singers would breathe wonderfully. But it’s the training that is the problem. Often, singers are taught to belly breathe, because the exhalation is of such primary importance in singing; a good, powerful usage of the lower abdomen to control the outward flow is crucial. But most of us don’t have the requisite strength and awareness in the deeper layers of abdominal musculature, especially in the transverse abdominis, to accomplish this without overuse of the superficial layers and lots of tightening in the rib cage. So my first task with a singer who has vocal issues is usually to open the ribs, encourage the client to widen the rib cage on the inhalation, and free up the whole thoracic structure. Since the emotional breath is contained in the chest, it is interesting that those in the performing arts, who need to feel and express in order to perform, are often taught a breathing style that constricts the sternum and thus the heart center.

All the relevant breathing material is covered in the chapter on Breathing, but to reiterate—

- Inhale away from the diaphragm, relax and soften the solar plexus, widen the side and back ribs and stabilize the xiphoid process, expand the rib cage in all dimensions, widen and lower the collarbone, lift the top ribs, widen and relax the jaw and larynx.

- Exhale by contracting the area between the navel and pubic bone, particularly just above the pubic bone, contracting it upward, with a very slight contraction of the pelvic floor. Keep the rib cage soft and lifted during the exhalation. In other words, the ribs stay roughly in the same position during exhalation as during inhalation; they do not collapse forward. Think of air releasing from the lower abdomen, then the back ribs lift to allow the air to pass out from the spine and into the larynx.

When the breathing is corrected, about half the time the vocal issue is too.

Easing the Throat and Tongue Muscles

Notice your tongue and larynx. You can probably feel a holding and tension all the time, which you can’t let go of. Your throat and tongue muscles are deep muscles; you won’t be able to consciously release them unless you have extraordinary control. They connect into the hyoid cartilage (see fig. 8.1) and affect its ability to move freely. The hyoid, which houses the larynx, is connected entirely by muscle; it does not connect directly to another bone. The only other bone in the human body that shares this situation is the patella, the kneecap. From this, you can understand: first, how much the larynx requires free movement, space, and blood flow; and second, how distortions in any of the numerous small muscles can distort the sound.

Relax the Larynx, Jaw, and Tongue

Relax the Larynx, Jaw, and Tongue

The larynx, jaw, and tongue must be relaxed to sing properly without stressing the vocal cords. What you experience as tightness in the larynx is tightness in the strap muscles, which tighten and pull the larynx toward the chin.

- You can push the larynx down directly by placing the heels of the hands against the sides of the throat and pushing gently down toward the collarbone.

- To release the base of the tongue, place the tips of the fingers of both hands on the larynx and find the ridge in the middle. If you find several ridges, it is the one nearest the chin. Place your fingertips right above that ridge, in the hollow.

- Press the fingertips gently toward each other, squeezing the larynx slightly. Let the tongue relax, stretching it slightly out of the mouth.

Releasing the Cranium

After releasing the breath, usually the next place we work with singers is the whole cranium, paying special attention to the muscles around the occipital ridge. In terms of kyo and jitsu, the jaw is generally jitsu, consciously tight and overworking, while the other cranial bones and the cranial fascia are devoid of movement and blood flow, holding the cranium in a fixed, inflexible position on the body rather than having very slight movement in the cranial bones, particularly the inner ones such as the sphenoid. We can release the cranial bones through bodywork and release the tight fascia of the scalp. We can also influence the position of the sphenoid bone by working in the hard and soft palate, despite not being able to palpate it directly.

When the muscles attaching to the occiput at the back of the skull are too tight, as though the head is glued onto the neck, the jaw has to compensate muscularly because it cannot release from the skull; the chin (which is the jaw, of course) will point up and out instead of releasing downward with gravity. It is then held in a state of constant tension, which results in an inability to release the larynx and lift the palate. In other words, the muscles of the jaw must be released, which means that the whole cranium must be released and positioned well on the top vertebra inside the skull in order for the laryngeal elevators to be able to relax enough while the palate lifts and the larynx maintains freedom of movement.

FREEING THE TONGUE

The most flexible and changeable structure in the mouth is the tongue, which also has a significant effect on releasing vocal tension. A well-known yogi once said that all the words we tell ourselves are formed by our tongues, soundlessly. You can feel a slight vibration in the tongue all the time. It cannot be stopped and goes on even during sleep. That is harder to prove, of course, but I’ve watched people’s tongues as they sleep, and I believe it to be true.

The tremendous ability of the tongue to change shapes also creates the sounds of speech and singing. It needs to be mobile and free in order for the muscles to have full range and create the many possibilities of positions the tongue is capable of. Stiffness and immobility of the tongue cause strangled sound, sore throat, and so on.

Exercise for Tongue Tension

Exercise for Tongue Tension

To understand where the ideal resting position of your tongue is, try this five-part exercise.

- First, stretch the tongue by pulling it out of your mouth with your fingers—you can use a paper towel or a piece of gauze so that your fingers don’t slip. Pull it gently up, down, left, and right.

- Now push your tongue against the back of your lower teeth as far to the right of your inner gumline as you can, and then push your tongue as far to the left as you can, as though you were pushing your teeth outward from the inside, running back and forth along the teeth with moderate pressure, not to the point of creating tension. Repeat 10 times on the upper gums and 10 times on the lower gums.

- Push your tongue hard against the roof of your mouth, and then push the floor of your mouth down with your tongue; open the mouth using the strength of your tongue, without tightening the jaw. Repeat both the up and down 10 times.

- Now stick your tongue out of your mouth as far as you can. In this outstretched position, move it as far as you can to the right, turning the head with the tongue. Allow the tongue to lead the head. Repeat this moving to the left. Repeat both 10 times.

- Next, very gently turn the head from side to side with the tongue relaxed outside the mouth and the mouth slightly open, not moving the tongue separately this time. Allow the movement of the relaxed tongue to follow the movement of the turning head, as exactly as you can. You should feel a widening and relaxation at the base of the tongue. Repeat this movement 10 times.

When you have completed the exercise, notice the position of your tongue relative to the teeth and the roof of your mouth. Is it touching the upper or lower teeth? There is not a right or wrong way. Believe it or not, much of it has to do with the length of the tongue. See if you can figure out why this might be.

Manual Release of the Tongue and Jaw

Because the tongue and muscles that tighten the throat are so difficult to release consciously, it can be a great help to release them manually. The jaw needs to be able to release open without the larynx rising, which is physically impossible if the muscles of the tongue and jaw are overly tight. If the jaw muscles, such as the masseter, are too tight to allow the jaw to release open, the digastrics has to work to open the jaw. The digastrics is a muscle that engages to open the jaw, but it also raises the larynx because of its connections with the hyoid. If the jaw is relaxed enough to release open, then the digastrics doesn’t have to work to open the jaw and the larynx can also stay released. This is just one example of the type of tension that this manual work can help. This work will help most vocal problems—I’m not going to specify too much because any tensions can affect all vocal problems.

Working in the Mouth to Release Vocal Tension

Working in the Mouth to Release Vocal Tension

Although we cannot work directly on the entire vocal structure, we can help most vocal problems and general vocal tension to improve the singing and speaking voice by working inside and outside the mouth to release many of the muscles of the tongue, jaw, and palate that affect the voice. You can explore and loosen them yourself.

First loosen the outer cranium, including the forehead and temporal area, as well as the occiput, by rubbing your entire scalp with your knuckles. Then go to the mouth. The cranial structures are usually stuck, which leads to excessive jaw tension. The jaw is the jitsu, and overworking because of misalignment of the skull and lack of subtle movement in the other cranial bones is kyo.

You may choose to wear gloves to work inside your mouth, as the oils in your hand can be irritating to the tissues. You absolutely must have clean hands and short nails to do this work.

1. First, go back between the outer back teeth and the inner cheek. You will feel a ridge—part of the inner structure of the mandible. The movements you use are scooping and widening, as you move the flesh away from the center of the head. Start inside the ridge, moving up toward the top of the head first, and then scooping down. There may be no space to go far back. Do not force. Work the rest of the mouth first and come back.

2. Next, go to the upper part of the jaw where it abuts the inner cheek. Scoop out the flesh gently.

3. Repeat on the lower jaw and inner cheek surface of that side. Pay attention to the chin area, where occipital tensions are reflected.

4. Repeat on the other side.

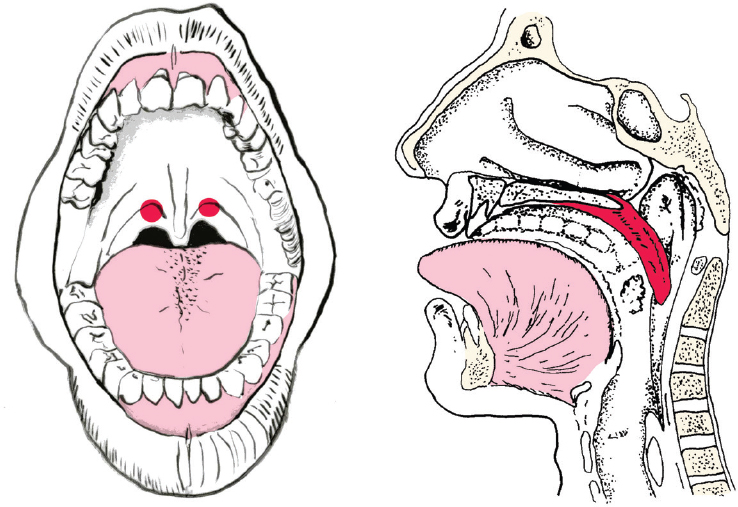

5. Next, go to the pterygoid muscle and the hard and soft palate (fig. 10.1), which influence the sphenoid (fig. 10.2). Start at the hard palate in the centerline with both index fingers or thumbs, and move them to the outer edge to widen. Go back into the soft palate with one index finger if you can. But don’t force it!

Fig. 10.1. Soft palate

Fig. 10.2. Sphenoid bone

6. Now, one side at a time, go to the upper part of the pterygoid (between your upper and lower jaw on the inside) and the soft palate. Scoop and lengthen down. Repeat on the other side.

7. Now come back to the first position, way back inside the TMJ (temporomandibular joint), the outside of the upper teeth. Use both fingers, one on either side of the mouth, if there is enough space. If not, don’t force. The space will open over time.

Soft Palate Release: Advanced

Soft Palate Release: Advanced

The soft palate and base of the tongue are the second place we learn vocal suppression; the first is the diaphragm. After the general mouth release outlined above, the soft palate can be traced back in the mouth using a clean, gloved index finger. If you practice this in a standing or sitting position, you’ll be much less likely to gag. Practice widening and going as far back as you can.

Lift up gently toward the ceiling as though your thumb or finger were a little hook. Then allow the TMJ to drop and the lower and upper parts of the jaw to separate without forcing. Eventually with practice you may be able to feel the very beginning of the atlas vertebra (C1, see fig. 8.2). You may feel changes at the base of the tongue.

Breath Pattern for Breaks in the Voice (at any place)

Breath Pattern for Breaks in the Voice (at any place)

This pattern establishes control of the transitions through different parts of the voice. This exercise actually has more to do with the nervous system than the muscles and has to do with the ability to tolerate blood chemistry changes, flexibility in coordination of different structures, and the ability to use weaker muscles when needed, without strain.

First, find the dominant nostril by blocking one off and breathing through the other. Which nostril is easier to breathe through? If you are not sure, pick the left nostril to work with—that is, assume the right one is dominant. In this exercise you will block the nondominant nostril with your thumb (the left one for our purposes), inhale through the right. Then you will block the right and exhale through the left in the following pattern:

Exhale for 4 seconds.

Hold the exhale for 4 seconds (don’t breathe in at all).

Exhale for 4 seconds.

Hold that exhale for 4, and so on, until you have to inhale.

So this will be the total pattern:

- Breathe in through the right nostril, blocking the left.

- Then unblock the left and block the right.

- Exhale slowly through the left nostril only, not inhaling at all as you exhale for 4, hold exhale for 4, exhale for 4, hold for 4, exhale for 4, hold for 4.

- Then block the left nostril and inhale through the right.

- Repeat the cycle for at least 5 minutes.

You’ll discover something very important when you attempt to lengthen the exhalations, or 20 more cycles of 4/4. If you let out all your air at once, you won’t get very far. You must exhale so lightly that the passage outward through the nostrils is almost imperceptible. This is how you develop strength and power in the breath, not through vigorous breathing. To allow this slow, controlled exhalation, release your muscles as much as possible, even if your nervous system panics.

One of the biggest mistakes both singers and public speakers make (it’s actually much more important in speaking than in singing) is to pull air as though starving for oxygen, as fast and hard as possible, and then push it out way too fast, with the result that not much control develops, and a great deal of tension builds up in the body. It is actually a panic reaction—we gasp air in suddenly when we are shocked or startled. Continuing a chronic panic reaction creates huge stress in the nervous system. Remember how breath controls the mind? This way of breathing disturbs and panics the mind.

When you are under stress, breathe very, very slowly, in a crescendo pattern, starting with pulling in almost no air, and building with continuity until the peak of expansion is reached. That peak is the place where there is a small effort, but no tension. Then exhale slowly the same way, letting out the air as though not even a flower petal under your nose would be disturbed. The interrupted exhalation pattern in the exercise will force you to exhale this way. Otherwise, you’ll just run out of air.

COMBINING STRUCTURAL WORK AND TECHNIQUE

The many singers I have worked with over the years found the exercises I have presented to you here beneficial for their voices. I hope they prove helpful to you too. We have only addressed structure in this chapter, not usage. This work is most helpful for singers when used in conjunction with improving usage and technique with a talented voice teacher or therapist. Nonsingers can also benefit tremendously from working with a voice teacher, as singing can be a tool for accessing and releasing physical and emotional blocks as well as improving your speaking voice. You need a good voice therapist or teacher to train you in the correct speech patterns. That’s not my province. However, working with the vocal structure can assist greatly in the work you do with your voice teacher.