9

Breathing

MANY PEOPLE WHO HAVE restriction in their breathing patterns tell me they “forget to breathe.” Fortunately, they can’t really do that; their bodies will take over, and they will automatically start breathing just to stay alive. In this sense, respiration is an involuntary function we don’t have to think about. Breathing is also voluntary—we can restrict it or deepen it as we choose, and we can also train our breathing patterns. Most of us cannot control our heartbeat or our digestion very well (though this is possible and can be learned).

The beginning of all movement patterns is the breath. A change in the rhythm of breathing marks all physical and emotional transitions. If you can identify when the change takes place, you will be able to understand and work with your patterns before they become so entrenched that the connective tissue is involved. Remember that “forgetting to breathe” involves a lot more energy and effort than just breathing.

Most of us, when we are under stress, hold our breath in an effort to control ourselves. If we don’t like where we are or whom we are with, we may want to reject our environment by not inhaling deeply. The letting go of the breath in the exhale may threaten our sense of autonomy and control. The diaphragm, structurally, functions as a bridge separating the lower body—the organs and the parts of our bodies we associate with instinct and gut feelings—from the upper body and our conscious emotions and thoughts. It is also one of the first muscles we learn to tighten. Even very young babies, before they are mobile enough to develop structural distortions, can learn to suppress crying by squeezing in their diaphragms. It is one of the first ways we learn to not feel strong feelings and often stays with us all our lives as a shallow, suppressed breathing pattern.

We can also breathe incorrectly because we have the wrong idea about how we should be breathing. There is not a right or wrong way to breathe, but different activities require different uses of the breath, and we can make the mistake of believing that specialized breathing patterns are right for everyday life. These are the most common misconceptions people have about the structural aspect of breathing:

- The sternum does not move, only the lower abdomen.

- The shoulders and collarbone initiate the breath.

- The sternum sticks out, and the lower back shortens.

These ideas come from many different sources. Some yoga teaching emphasizes the lower abdominal breath, and various schools of vocal technique use diaphragmatic breath and work with a hyperextended sternum. To understand normal relaxed breathing, get to know your rib cage.

NORMALIZING YOUR BREATHING

One purpose of training the breath is to shift physical and mental patterns. Yogis discovered that changing breath patterns could quiet the mind as a preliminary to meditation, or wake it up when it was listless. Since we spend so much time attempting to change our mental states through therapies and medications, wouldn’t it make sense to explore these possibilities through something as simple as the breath? Maybe it’s so simple we don’t believe it. The mind seems a very complex thing, and we assume that we need to work on it in painstaking, slow, and difficult ways. Medications have shown us that mental and emotional states can be changed easily by taking a pill, so why not use a completely safe and healthy method that will only serve to benefit us (the breath), rather than turning immediately to more risky interventions such as drugs?

Shape of the Breath

You are already exploring the science of pranayama, regulating the life force with the breath, right now, in the sense that the way you are breathing at this moment is influencing your nervous system and your mental state. The way you feel can be changed by the shape of your breath, the parts of your body you use when you inhale and exhale, and whether you use your whole body and lung capacity or restrict yourself to a narrow portion of the torso. You may suppress your emotions by not allowing your chest to move, or your gut feelings by hardening your belly.

It’s natural for the flow of air to shift from right to left and back throughout the day. If your breath pattern is stuck in the right nostril your sympathetic nervous system will be overactivated, making you feel stressed and, maybe, interfering with sleep. If the reverse is true, your parasympathetic nervous system will be constantly dominant, making you sluggish.

Or maybe you can only breathe through your mouth. Mouth breathing is emergency breathing, used when the body needs more air quickly, usually when you are exerting yourself. When your heart rate is stable, you should breathe primarily through your nose, which has natural filters in it (the tiny hairs that keep out dust and some germs). You cannot control the airflow as precisely with the mouth.

There is an expression, “mouth breather,” that refers to a person easily frightened, without backbone. Mouth breathing when you are not exerting yourself tells your body that there is an emergency and can make you feel anxious or even panicky. The classic way to calm down a person who is hyperventilating (having a panic attack) is to have her breathe into a paper bag, so she inhales her own carbon dioxide, which is a natural relaxant and tranquilizer.

All these forms of breathing are fine sometimes, when in their natural place. What can be harmful is the locking of the body into one fixed breath shape, which blocks our natural flow. Breath shape is the first aspect of the breath that we can work with.

Aerobic Capacity

The second aspect of the breath that we can influence is the aerobic—simply, the health of the lungs. This is so basic that it is overlooked all the time. I’ve worked with singers who can barely huff and puff their way up a flight of stairs, and then wonder why they can’t sing a Wagnerian opera requiring huge amounts of cardiovascular stamina. Without this component, there will be no energy to work with, not much juice.

I want to address this briefly, really, just so we can exclude this as a possible source of difficulty. Certain physical conditions—anemia, asthma, and so on—could affect cardiovascular capacity. But it’s usually just lack of fitness.

You can evaluate, and improve, your aerobic capacity easily by exercising on a cardio machine at the gym, like a treadmill, bike, or stair climber. Any kind of sustained exertion that brings your heart rate up for at least twenty minutes will improve your aerobic fitness, but the gym machines also allow you to assess where you are in relation to a norm. You can do lots of exercise of the nonaerobic kind—weights, yoga, Pilates, and so on—and still be weak in the cardiovascular aspect.

The gyms will have training charts that show you what the heart rate “training zone” is for you in your group—remember that this may be different if your resting heart rate is faster or slower than average, and change accordingly. You should be able to stay in your training zone for about twenty minutes without getting winded.

Of course, to do this you need a gym, charts, and a heart rate monitor. But actually you don’t need any of this to improve your aerobic fitness—just do something where your heart rate stays up but you don’t get so out of breath you cannot talk, for at least twenty minutes. You will need to warm up (your heart rate won’t go up right away) and cool down—at least five minutes of light exercise to lower your heart rate gently. Interval training—raising the heart rate to the high end of your training zone, maintaining this for a few minutes, dropping down to the low end for a longer time, rising again, and so on—is actually the fastest way to improve lung capacity.

You can also improve lung capacity by breathing just through your nose, taking your workout to a place where it is difficult but not impossible. Because the air passageways of the nostrils are much smaller than the mouth, it’s harder work to breathe nasally, and you will learn to control your breathing and use your full lung capacity. That’s pretty straightforward. The other two components of breathing are a bit more complicated.

Breath Control

Breath control is how much you can change and regulate your inhalation and exhalation, how long you can hold in your inhale and exhale (retention of breath), and how long you can practice breathing exercises without becoming lightheaded or dizzy. This is breathing as a skill, something you can learn to manipulate. You can achieve this kind of breathing health through a variety of breathing exercises, the yogic pranayama practice being the prototype. Singing will also increase this particular aspect of breath control.

A good deal of this has to do with your nervous system and how accustomed you are to tolerating the slight fear that comes when we retain breath for a long time or attempt to use the breath in this kind of way.

You may wonder what the purpose of learning and controlling breath patterns is, if you are not a yogi or singer. Most people understand that cardiovascular capacity is an important component of health—after all, doctors give you stress tests to assess this function. But why bother learning fancy, and difficult, breath patterns?

This is where the subject we discussed earlier, the regulation of emotions and states of being through the breath, takes a practical form. The breathing patterns are ways of changing your experience; there are patterns that will calm you, and others that will activate you, reduce stress, and so on. The ability to do this takes for granted that you have adequate lung capacity—you won’t get very far if you don’t.

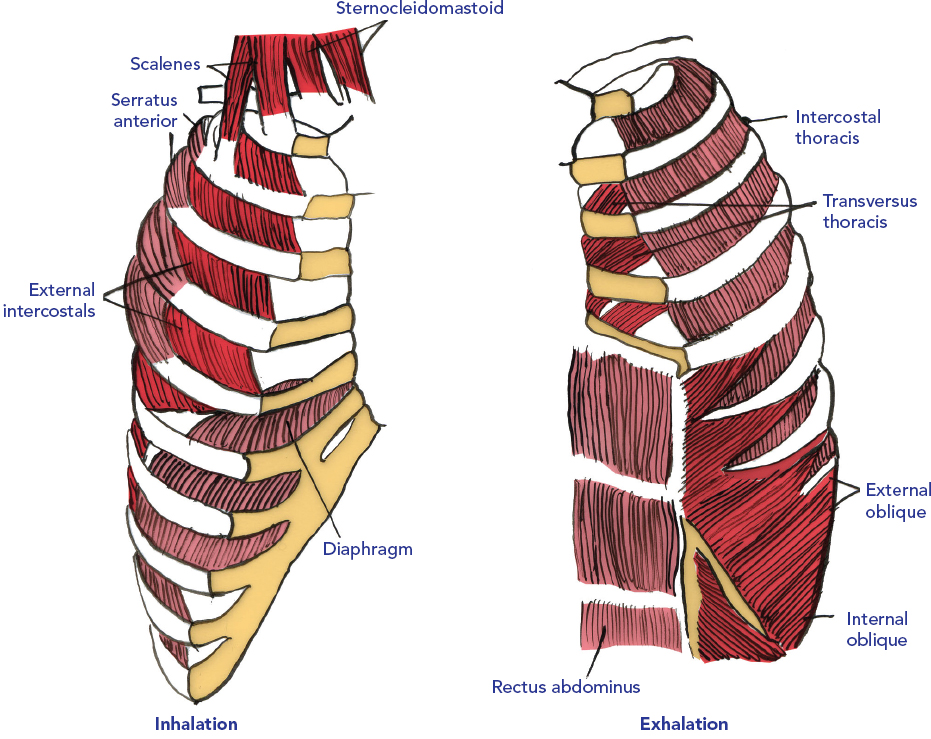

BREATHING STRUCTURE

The next component of the breath is the structural aspect of breathing: the health, strength, and flexibility of all the muscles involved in the flow of breath, inhalation, and exhalation, the alignment of the ribs in relation to the rest of the body, the openness of the throat, and the structures of the neck and head (fig. 9.1). You can be perfectly aerobically fit and able to perform long complicated breathing exercises and still be very uncomfortable when you breathe if your structure is distorted and the muscles can’t open and release a full breath.

I work with lots of singers who develop vocal injuries as a result of stressing a learned breath that they are using incorrectly, usually because they have the wrong idea about how they should breathe, such as not moving their chest when they breathe, so they then tighten the chest muscles, suppressing the natural breath. That’s the most common one based on the idea that when we are relaxed we breathe with our bellies. This is a good example of “a little learning is a dangerous thing.” It is sort of true that letting the breath move into the belly is a relaxed and open way to breathe, but not by restricting the movement of the lungs and tightening the chest. You will actually be able to take a deeper “belly breath” by allowing the upper ribs to expand. Try it and see.

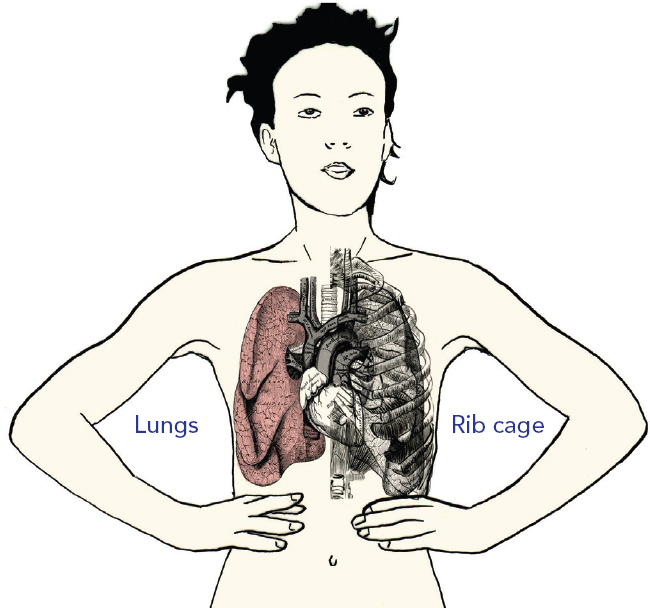

I remember teaching a class of singers about bodywork and realizing that none of them even knew where their lungs were. It sounds odd, but do you know? Place your hands where you think the top of your lungs are and then where you think the very bottom of your lungs are; now look at fig. 9.2.

About 75 percent of the clients I work with think the top of their lungs is at the level of their nipple line, when they actually reach all the way into the top chest and all the way down to the lowest bottom rib. Of course it is much easier to feel the bottom of the rib cage than the top because the collarbone sits right at the level of the top rib and is bigger and thicker. But try out the following experiment to see if you can feel your breath in your top rib.

Fig. 9.1. Breath flow diagram

Fig. 9.2. Lung placement

Feeling Your Breath in Your Top Rib

Feeling Your Breath in Your Top Rib

- First, touch the collarbone and then move your fingers behind and slightly under it, where there is a sensitive, nervy, triangular hollow. Behind that hollow lies the big and powerful trapezius muscle. Place your fingers on the hollow itself, pressing gently down. The top rib is inside that hollow. Depending on how much tissue you have there, you may be able to feel it.

- Press down a little harder and breathe naturally. You should feel a small movement there, a slight rise on the inhalation and a gentle release and drop on the exhalation. Keeping your fingers there and maintaining some pressure will stimulate the top rib. Can you feel the movement of the top rib against your fingers and then in front of it the collarbone, which will move slightly outward, widening as you breathe?

- See if you can activate your top rib a little more and let go of the collarbone completely. The collarbone is a part of the shoulder girdle, which is gently massaged by the breath under it, but it is not a prime mover of respiration.

- Now notice if your shoulder muscles feel any different. Take your fingers away, and see if you can maintain the activation of the top rib while you continue to let go of the shoulder girdle. We have only explored one side so far, so let’s feel the difference. Do your shoulders feel uneven now? How exactly are they working differently? Maybe you have more of a feel now for the relationship between shoulder tension and breathing.

- Now you can explore the other side in the same way, noticing any differences. All of the muscles in the torso, front, sides, and back, some neck muscles, and muscles that connect with the hips are actively involved in the breath; every tissue in the body is passively involved. So you can understand how muscle imbalances, postural misalignment, and even the condition of the abdominal organs will change your breath.

However aerobically fit you are, however long you can retain your breath in practiced breathing exercises, there will be distortions in the pattern of respiration as long as structural imbalances exist. By far the quickest and, for me as a bodyworker, the easiest way to change the breathing patterns is to work directly on the structures around the lungs and the diaphragm. You can, as you may have experienced when you were exploring your top rib, work on some of these muscles yourself. I’ll explain how.

The lungs are big. Everywhere you feel ribs, you basically have lung tissue underneath. Every rib should move away from the center of the body, away from each other, and slightly upward when you inhale and release inward when you exhale (see fig. 9.1). The top rib moves up and the bottom rib moves down to allow the rib cage to expand vertically on the inhalation. The rib cage is a cylinder, which moves as much in the back as in the front and sides. Take some time to feel all the ribs, with your fingers from the outside and from the inside of your body. Let your breath go into all the spaces of the rib cage, the armpits, the upper back, the lower back, and especially any parts that feel numb or difficult to feel. Gently tap those places to encourage the breath.

The Intercostal Muscles

Imagine a balloon with soft strings around it, encircling its perimeter. As the balloon is blown up it expands evenly and the strings move farther away from one another. If the balloon were deflated the strings would move toward one another and inward. Now imagine the strings have other small cords like basket weave wrapping between them. If the ribs are strings, the basket weave is the intercostal muscles (fig. 9.3). These muscles allow the ribs to open voluntarily, at least to an extent.

Fig. 9.3. Intercostal muscles

To take our balloon analogy further, imagine that someone dropped glue on the strings and basket weave unevenly, so that some of the strings didn’t move properly. The glue is our stuck, glued-up fascia caused by muscle imbalance. When the balloon expands, the pressure from the inside builds up and will only move against the flexible areas, so the glued-up areas don’t move at all.

Releasing Stuck Intercostals

Releasing Stuck Intercostals

See if you can find the stuck areas on your ribs and start to open them.

- Start anywhere on your rib cage. Using your thumb and index finger, feel the hard bone of the rib itself. Then move your thumb up or down slightly in the space between that rib and the next one. Even if you have a lot of tissue you can usually feel this area. Press into that space, noticing how much the ribs can move away from each other as you inhale.

- Then inhale and try to push your fingers away from the center of your body with your breath, consciously moving the ribs apart with your breath. Depending on the area you have chosen, you may feel a free, open movement or not much movement at all, and the space you are pressing into may be more or less sensitive. As you breathe into your fingers and encourage the ribs to move, you are lengthening the intercostal muscles. This will help open the stuck, glued-up places in the muscles.

- Explore as much as you can of the rib cage this way, lingering at the stuck places in order to open them. The areas that tend to be inflexible and sore are the armpits, the sternum, near the spine if you can reach it, and the lower side back area. Opening the side back ribs this way can alleviate lower back issues too.

Dealing with Lower Back Pain

When you feel what a large area of your back the rib cage covers, you can understand how important the rib cage is, not just to our breathing, but also to any kind of back problem. Each rib expresses the vertebra it is attached to, and you can mobilize the entire thoracic spine by releasing its partner rib. After releasing the appropriate ribs, you may find a new degree of flexibility and maybe less pain, if you had any pain, in your back.

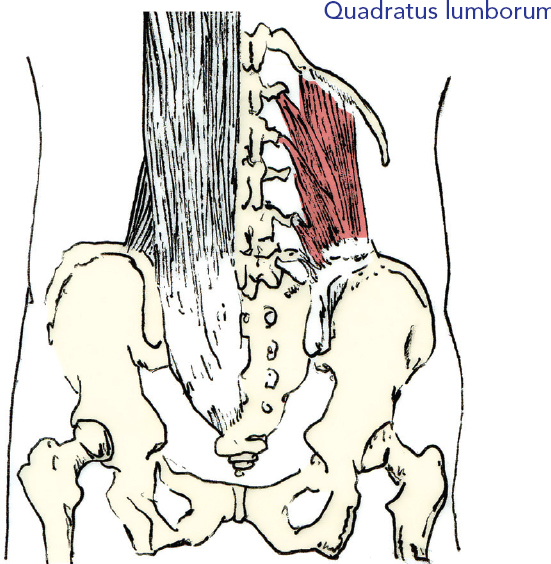

One of the muscles that’s often responsible for lower back pain, quadratus lumborum, is also a breathing muscle that shortens on the inhalation, pulling down the lower ribs and increasing lung capacity (fig. 9.4). Quadratus lengthens on the exhalation, allowing the diaphragm to release and the back ribs to soften.

Fig. 9.4. Quadratus lumborum

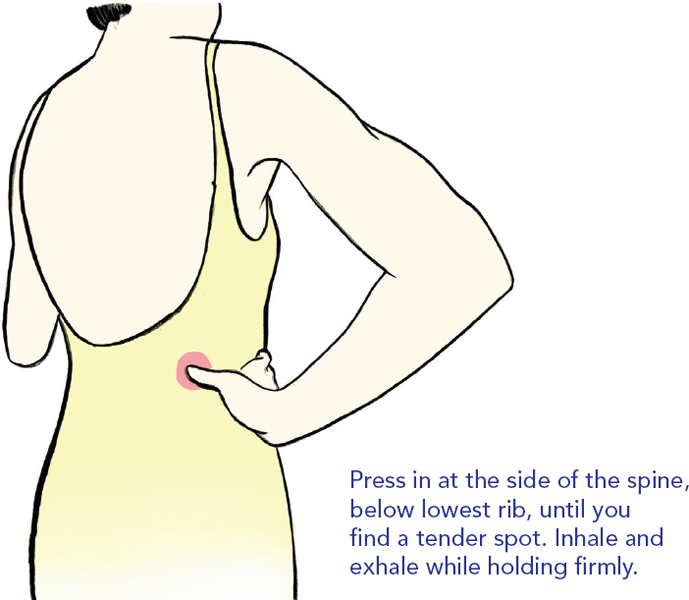

Quadratus is worth getting to know in its dual role as breathing muscle and stabilizer of the rib cage and back. Find it by pressing in at the side of the spine just below the lowest rib that is attached to it (fig. 9.5).

Fig. 9.5. Finding the Quadratus Lumborum

Finding the Quadratus Lumborum

Finding the Quadratus Lumborum

- You can work both sides of your spine with your thumbs, or a knuckle. Quite far in to the side and high up under the lowest rib, you’ll find a tender spot. If you have lots of surface tissue, it may be harder to find, so bend to the side, stretching that area to make it more accessible. You’ll find it!

- Now, hold your hand in that area and see if you can feel the movement of the back ribs away from where you are holding. You may not feel much—this tends to be one of the laziest areas of the rib cage. Breathe into the back ribs consciously, inflating both sides equally to the side, as you hold the tender spot firmly. This may help relieve lower back pain.

You can work this way with any tight or painful area in your back. Locate the ribs that run through that area and work the spaces between them as we described, all the way round the body. Usually you will find tender or stuck places in the ribs, often more sensitive on the opposite side of the painful places in the back. See if the pain is relieved at all this way.

This is how I work with scoliosis—I’ve found that working the ribs thoroughly enough to reposition them opens up the spine in a way that working directly into the spine itself cannot accomplish.

See if you can work into chronic back problems this way also. When you get more practice at it you’ll know your trouble zones and just work there. If you want a stronger pressure, you can use a very small hard rubber ball, about the size of a plum, and lie on a mat with the ball between you and the mat so that it presses into the spaces between the ribs. This will be a much stronger pressure if you want that intensity. Soft small balls don’t seem to fit properly in the intercostal spaces, but you could try lying on a thicker mat if you find the pressure too strong. The advantage of using a ball this way is that you don’t have to work at the same time. Once you have found the right places, you can relax on top of the ball and focus on the breathing.

Correcting Breath Imbalance

Now you can check the sides of the rib cage with your hand to see which side, left or right, you are breathing more on. Usually we breathe more deeply into one lung than the other, quite unconsciously, but you can see how that might affect your structure, opening up and strengthening the back and chest on the dominant side, and shortening and tightening the same areas on the weaker side. There’s one common reason for this you can check now, which is if the nostril on the weak side is closed, either from muscular weakness or congestion. So see if that’s the case.

If you find one nostril not able to breathe fully, check this by blocking off the other nostril. There is a natural switch over every few minutes from one nostril to the other. If a nostril is chronically blocked you won’t be able to shift your breath into it easily. Don’t be surprised to find you can’t breathe through one nostril at all.

You may be familiar with alternate nostril breathing, a yoga exercise that balances the brain hemispheres. The left nostril stimulates the right brain, the more creative intuitive side, and the parasympathetic nervous system, which controls involuntary systems in our body, such as digestion, and allows us to relax. The right nostril stimulates the left brain, which controls logical thinking and the sympathetic; that is, the more activating part of the autonomic nervous system. So of course we need a balance or we’ll have trouble either mobilizing ourselves or going to sleep. For most right-handed people the left nostril is more chronically blocked or weaker.

Balance Yourself

Balance Yourself

You can experiment with this very simply by finding the nostril you have most difficulty breathing through. Then block the opposite one, making sure you don’t push your head into an uneven position.

Just sit however you’re comfortable and breathe through the weak nostril. You may need to use your other hand to open the nostril. You can breathe slowly and deeply or try a yoga breath of fire: that’s a short, fast, sniffing breath with equal emphasis on the inhale and exhale. I feel a shift in my energy after doing this for about five minutes and a lot more change after fifteen minutes or so. Try it and see how and when you feel the subtle changes of your energy as different brain centers open up.

For most people the left nostril breath is calming and centering, the right nostril more stimulating. Slow deep breathing is relaxing; breath of fire, energizing. So you can combine these factors, as you like, to create the effect you want. If you have a headache on one side, try breathing on the other side. This works on the kyo/jitsu principle (see here) of shifting excessive energy, the pain, to the depleted location, the other side.

After balancing yourself this way, sit for a while and notice the flow of breath in and out of both nostrils. We hold a lot of tension in our noses. That’s the first place your breath will shut down. Mostly you don’t feel tension in the nose; most nasal tension is unconscious and related to holding in the eyes and jaw. This is one way you can tell if you are tight; a relaxed breath will be felt more in the septum area, the inside channel of the nostrils, than the outer edges of the nose. Direct your breath there, and relax the muscles under the nose, the triangular area beneath the nose. Think of this area widening as you inhale, and lifting slightly. That will relax the muscles around the nostrils. Then keep the widened feeling, and let go of the lift as you breathe out.

Muscles Involved in Breathing

The various muscles involved in breathing are shown in fig. 9.6.

Fig. 9.6. Muscles involved in breathing

Running from the top rib to the inside of the cervical vertebrae you’ll see the scalenes. They shorten on the inhalation to allow the lungs to expand upward and then release down on the exhalation. These are the muscles that control the slight movements you felt when you explored the top rib area. You can see now how neck tension influences the breath and vice versa.

As the top rib is pulled up, the collarbones widen and slightly separate, deepening the well in the throat, the sternal notch. They do not lift upward with the top rib but move only to allow space for the expanded lung area. The upper area of the sternum, the manubrium sterni, lifts up toward the chin and slightly rises as it moves away from the body. All the upper ribs open gently up and away from the body, the middle part of the sternum moves outward away from the body, and the lower part, the xiphoid process, mostly stays still to stabilize the rib cage.

You’ll notice that most people, maybe you, move the lower part of the sternum much more than the upper. Think of a piece of string attaching the lowest part of the rib cage right under the xiphoid process to the spine, so it can’t move at all and the ribs separate from each other as you inhale. Notice how that forces you to expand the side and upper areas of the rib cage; it is more muscular effort but ultimately more relaxing.

The spine expands along its whole length, and the back ribs move upward and outward. The shoulder blades move very slightly away from each other to allow for the expansion of the upper ribs. The stabilization of the xiphoid process creates a framework for the diaphragm to move freely, expanding the lungs.

To feel the breath moving into the upper parts of the lung, first run your fingers between the ribs in that area including the sternum, the armpits, and as much of your upper back as you can reach. Then lie on your back with your arms raised and crossed behind your head. This is the easiest position to feel the upper ribs.

Even Chest Breathing

The top part of the chest and the upper back hold the emotional breath, and when this opens we can start to feel deeply held grief and longing. Symbolically and energetically it is the movement from the heart, the center of feeling, to the throat, expression. Due to some misunderstandings about the nature of the breath and the role of the diaphragm, many people deliberately block off this part of their breathing, clamping down on their emotional energy and creating tension in the chest and shoulders.

One misunderstanding involves the role of the shoulder girdle in breathing: it should be passively moved by the ribs beneath it, not actively engaged. In an effort to not involve the shoulders in breathing, many people tighten the whole upper rib cage. Unfortunately, many singers and vocal practitioners have been trained to avoid shoulder breathing, by cutting off the breath in the upper chest. This leads to emotional constriction, neck and shoulder pain, and vocal strain. You should be able to breathe easily while keeping the abdomen tight and the rib cage lifted. Chest breathing is an even movement in all directions of the upper chest, including the upper back.

CORRECT DIAPHRAGMATIC BREATHING

Diaphragmatic breathing comes from widening the lower rib cage and opening the back lower ribs without much movement of the front lower rib cage or the solar plexus. For most people this is counterintuitive, and they restrict the breath to the in-out movement of the solar plexus. This comes from and creates anxiety. The adrenal glands are on top of the kidneys at approximately the location of the lower back ribs. When we are shocked, frightened, or very stressed, they pump out stress hormones into the blood.

It seems as though this fight-or-flight reaction causes us to contract our side ribs, narrowing our vulnerable and sensitive solar plexus area. Think about what happens when someone is punched in the gut; he contracts his ribs inward, making the space of the solar plexus smaller and tighter. This is the adrenal reflex; it’s as though the many shocks we experience cause chronic, self-protecting, curling over and narrowing in the gut. But long term it doesn’t protect us; it only restricts our diaphragm so we can’t breathe freely.

Freeing the Diaphragm: Freeing the Breath

Freeing the Diaphragm: Freeing the Breath

Experiment with this.

- Put your hands on your side ribs and breathe into them, so your hands move farther away from each other. The ribcages are pulled away from each other on the inhalation. You should feel a significant (at least 2 inches) movement sideways. To do this you will have to suppress the opening of the front lower ribs to some degree, not entirely; there will maybe be a half an inch outward of movement.

- Notice how this diaphragmatic breath makes you feel, and breathe as you naturally do. Is that different? Maybe there is less movement or none in the side ribs, more in the solar plexus. How is that; does it feel different? Without a good diaphragmatic side breath you will not be able to obtain much stamina, in exercise or vocal work, and you will probably feel pulled in and anxious as the adrenal glands are overstimulated. It’s like putting yourself in a tight, confining box.

- Now lie on your back and press your hands gently onto the front ribs, suppressing the outward movement slightly and the upward movement slightly. Imagine you have a band expanding from the bottom front of one side of your rib cage to the other. The solar plexus area does not change much as you breathe, only the side back and upper ribs expand.

- Imagine little balloons inflating under your side ribs as you inhale. Let the back ribs drop to the ground; it’s a relaxed easy breath with no tension. If the deeper muscles are not strong enough to create significant movement, work the side ribs and visualize the balloons moving. See if you can feel the spaces between the ribs moving outward and upward as you inhale.

- As you exhale, keep the rib cage lifted and bring in the lower abdomen, about 2 inches below the navel, not the upper part.

- The solar plexus stays soft and relaxed through the breathing cycle. You’ll probably find, if you have the breathing habits of most people, that at a certain point in the exhalation your solar plexus will want to tighten. If that happens, raise the rib cage even more and think of pulling the pubic bone up toward the navel, slightly firming the lower abdominal area, just slightly, and you should feel a deep contraction under the navel, pulling in and squeezing together laterally (this is engagement of the transverse abdominis to support exhalation).

Diaphragm Opening

Diaphragm Opening

The diaphragm is not a muscle that can be strengthened, nor would you want to. The effort of breathing comes not from the diaphragm, but the auxiliary muscles of inhalation and exhalation. The diaphragm needs to be relaxed and released so that it is free to move properly, allowing the auxiliary muscles to do their job.

- To relax the diaphragm, lie on your stomach with a 5- or 4-inch ball under your solar plexus, below your rib cage. Breathe into the rib cage and relax. It may be slightly painful at first, but that should lessen after a minute or so. The smaller the ball, the less the sensation.

- You can also stretch and open the area by lying on your back, with a 7-inch ball under your back at the level of the solar plexus or slightly above it. Stay in that position for a while, breathing in the rib cage. Turn to your side to get off the ball.

- If you have a large physio ball, you can lie back over it and stretch the diaphragm that way.

- You can also do the Psoas Stretches because of the position of the psoas and the diaphragm attachments to the spine. The psoas must be released for the diaphragm to move properly.

Advanced Diaphragm Technique

Advanced Diaphragm Technique

You can also try this more advanced technique.

- Sit any way you are comfortable, and bring your fingertips to slightly above your navel, pressing in hard. Of course, make sure your stomach is empty. You should feel the navel pulse, which is the pulse of the main artery (the aorta). Is this pulse on the navel, or to the side, above or below? For you to feel strong and steady, it should be most clear and powerful just below your navel.

- Now lean forward, and press the fingertips hard below the navel. Breathe long and deep, pushing in farther as you exhale. You may feel a lot of tightness in the solar plexus, where the diaphragm meets the spine. It will release as you breathe in the sides, back, and chest. Continue for at least a minute, longer if you want.

- Then bring your fingertips out slowly. Now feel the navel pulse and notice any changes. When the diaphragm is relaxed and moving freely, the pulse will probably drop lower, to be felt most strongly just below the navel.

Don’t do this at all if you are pregnant or menstruating.

INHALATION

Inhalation, anatomically, involves the synergistic action of many muscles in the torso, mostly in the rib cage. The assessment of how many muscles are involved varies between forty and fifty-five—anyway, lots. It involves freedom in pectoralis minor (fig. 9.7) and between the ribs.

Fig.9.7. Pectoralis minor

Traditionally, ease on the inhalation (in other words, being able to inhale a long, deep breath easily and comfortably) is associated with self-assertion, the ability to start things, and to create prosperity. Ease in maintaining the inhalation is connected to keeping things going, to holding on to what you have, and to containing feeling.

Exhalation is supposed to represent the ability to deal with anxiety, and to tolerate the idea of death. Do you think this is true?

Equalizing Breathing Pattern

Equalizing Breathing Pattern

Try a breathing pattern with an even count—four counts for the inhale, four for the retention of the inhale, four for the exhale, and four for the holding of the exhale—then repeat over and over with no pause for at least three minutes. You can use any count you want; the point is to keep each portion of the breath pattern equal. You will find out which is hardest and which is easiest for you. For most people, holding out the breath is the most difficult and unpleasant. But not for everyone.

Let’s look at how you might use the information you get if you do this exercise.

Tight, hunched shoulders that rotate inward and a collapsed chest—a slumped posture—will inhibit inhalation. I associate this type of posture with depression. In Core Energetics Theory (a method developed by John Pierrakos, M.D., which brings consciousness to how we block our energy and recreate defense patterns adapted in childhood that keep us limited and disempowered), the body type that expresses itself this way is called the oral type and is considered to have been deprived of nurturance at an early developmental stage, causing repressed oral desires and a kind of unsatisfied neediness. Whether this is true or not, we do associate the posture resulting from lack of strength and flexibility with an inability to assert oneself and take in what we need.

For women, this kind of slumping often comes from having large breasts that they don’t want to stick out. They may have attracted a lot of unwelcome attention when they were growing up, so they got into a habit of slumping to disguise their chest. I see this in a lot of opera singers, who usually have large ribcages, if not big breasts. The feeling of shame and self-consciousness, and whatever negative sexual experiences they might have had, became locked into the posture. When we change posture through bodywork, those repressed feelings surface. As they feel the greater comfort and ease in being able to breathe more freely, the nervous system will process the negativity held in their bodies, which (hopefully) is no longer relevant to them as an adult.

The weight of the breasts themselves can also lead to rounded shoulders—it does require more muscle strength to maintain an erect posture. In this case, the person has a choice: strengthen the muscles that support the breasts or get surgery.

Releasing the Shoulders

Releasing the Shoulders

The ability to separate the rib cage from the shoulders is needed to inhale fully. The shoulders can easily get welded to the sides of the chest. I’d associate this pattern with tight pectoralis minor and serratus anterior and weak rhomboids (the “winged” shoulders we see when there is this muscle imbalance). I work serratus anterior and the intercostal muscles in the armpit to release this pattern. You can do this for yourself, as long as you can get your hand up into your armpit. I think it’s easiest and feels best to use the thumb of the hand on the same side.

- As you worked in the other parts of your rib cage, press the spaces in between the armpit ribs with a firm pressure.

- When you find a good sore spot, keep your thumb pressure firm and focus on sending the breath up and out, pushing your thumb away. Keep your shoulders relaxed!

These points—the Chinese call them the “fire points,” and they are associated with the heart meridian—can be extraordinarily sore and sensitive. Releasing them can begin to open up the part of the chest that holds in grief, longing, and emotions that have to do with connection and relationship. The muscle around the armpit and the roots of the shoulders reach out, push away, and pull things toward us.

Even if none of these things are issues for you, notice the change in your shoulders and neck after you work into the ribs of one armpit. It’s usually much more successful to work shoulder tension this way than to massage the top of the shoulders.

Think of the shoulders as they exist functionally, a girdle of bones, sitting on top of the rib cage and moved by the breath as it ebbs and flows under and around this girdle. Activate the breath in the ribs around and under the shoulders, and notice how this energy focus allows the shoulder girdle to give up some of its excess work and tension. I think of the shoulders being massaged from the inside by the rhythmic movement of the lungs.

EXHALATION AND THE DEEPER ABDOMINALS

The key to letting go of all the air in your lungs in a relaxed way is to keep the rib cage somewhat lifted and open on the exhalation, just as we learned to do when we inhale. The work of expelling the breath comes from the squeezing and pulling in action of the lower and deeper abdominal muscles, specifically transverse abdominis. To find this movement, inhale and exhale fully, not letting the rib cage drop down. Then, with the breath held out, pull your navel in as sharply as you can toward your spine. Focus on the area about two inches below the navel. The purpose of keeping the rib cage lifted is to suppress the action of the upper/outer abdominals, which will close in and squash the natural movement of the diaphragm, if they engage.

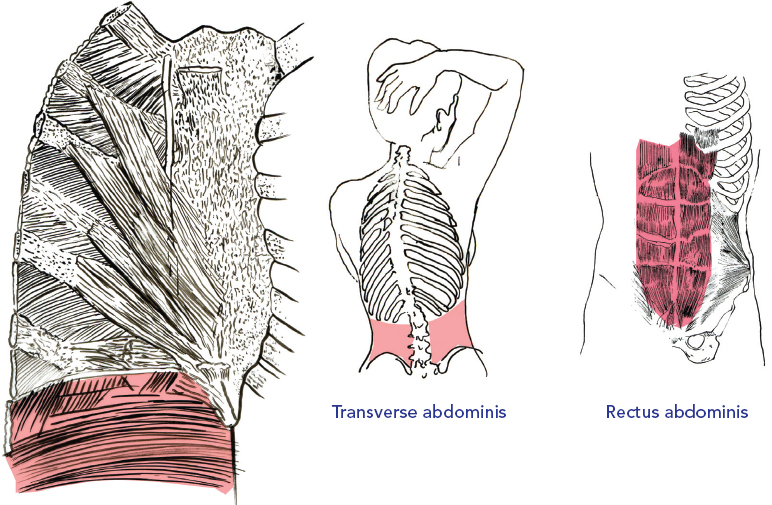

Look at fig. 9.8 below to see the relationship between the surface, usually much stronger, rectus abdominis, and the underlying transverse. Transverse abdominis is a deep abdominal muscle that functions as an inner girdle, shaping and holding in our organs, supporting the spine, and controlling the position of our diaphragm and the depth of exhalation. Think of its function in breathing as being similar to the handles of an old-fashioned bellows. As you squeeze the handles in (by contracting transverse abdominis), the membrane of the bellows (diaphragm) pushes up to expel air.

Fig. 9.8. Transverse abdominis and rectus abdominis

The outer muscle, rectus abdominis, creates those “six-pack abs” when it is developed and can bulge outward when built up. Its main function is to flex the abdomen forward as in a sit-up. When we pull the belly in toward the spine, moving the abdominal wall straight back, not up or down, we are using the lower fibers of transversus. When we tighten the abdomen, pushing the central area out slightly and hardening the belly, as though protecting ourselves from an anticipated blow, we are flexing rectus abdominis.

It is important for our purposes to understand the difference between the two muscles. For example, if we engage rectus instead of transversus on a deep exhalation, over a period of time we will develop the flexion of the muscle to such a degree that the rib cage will be held down and the diaphragm restricted. To engage transverse abdominis on the exhalation, keep the rib cage lifted, create even more length in the abdomen, and contract the muscles under the navel, squeezing in and back, while keeping the solar plexus as wide as possible.

Transverse abdominis will automatically contract slightly if you squeeze your “Kegel” muscles (the pelvic floor area, which you use consciously in bladder and bowel control). You may feel a slight but deep pulling, deep in the abdomen under the navel. When you need to inhale, keep the contraction of the abdomen and with the rib cage lifted, breathe in the chest.

Deep abdominal work, as in Pilates and other deep core strengthening, will help develop transverse abdominis, but the muscles must be worked in conjunction with exhalation to be strengthened for breath work.

This is where the belly breathing controversy can finally be cleared up, I hope. The bad habits some kinds of belly breathing can lead to have to do with a misunderstanding of the differences between rectus and transverse abdominis.

Rectus is an easily accessed, phasic muscle. If you employ rectus to power the breath, as you will if you push out your belly and lower your rib cage, whether on inhalation or exhalation, you will shorten the distance between the rib cage and the pelvis, and between the two sides of the rib cage. Over time, this will compress the tendons of the diaphragm, restricting rather than freeing your breath.

You have probably seen bodybuilders who have built up rectus at the expense of the deeper muscles to such an extent that they hunch over. This can even cause back problems over time as the lower back becomes overstretched. Now, most of us are in no danger of that, and abdominal flexion is an important function in back health. But using rectus and not transverse abdominis in breath work is easy, and since the upper fibers of rectus tend to develop more easily than the lower, diaphragmatic compression is a real issue.

There’s a simple way to avoid this happening, which doesn’t depend on the strength of transverse abdominis. On exhalation, just keep the rib cage lifted, front, sides, and back, or try to—it will depress somewhat. You cannot use rectus then; it is stretched too far. To exhale you must squeeze your belly and part of your back in, like squeezing a tube of toothpaste.

Don’t let the sternum depress, either. That may be difficult since there is often a lot of internal tension, and contracted fascia, between the sternum and the abdomen. Rub into your sternum with your knuckles to release some of this. You can also focus more on the squeeze below the navel—that will help.

Finding the Action of Transverse Abdominis in Exhalation

Finding the Action of Transverse Abdominis in Exhalation

- Exhale with the rib cage lifted. Keep it lifted, and exhale fully.

- Hold out your breath, and pull your navel in hard toward your spine. Think of squeezing in from your back toward your belly also, as though compressing an interior place slightly below the navel and right in the center of your body. Hold this contraction, and release all the other places that have probably tightened up!

- If you can’t find this movement at all, engage your pelvic floor muscles (the Kegel exercise) used in bladder and bowel control. This will automatically engage transversus. You may feel a slight, deep pulling in the abdomen.

- Now, when you need to inhale, keep the contraction and breathe into the upper body. Lift your rib cage even higher, relax the shoulders, and repeat.

If there is a lot of tension in the rib cage and the chest, inhalation can be difficult and feel forced. Exhalation can be hampered by tensions in the gut and fascia pulling around the lower abdomen.

All breathing will feel like hard work if the central tendons of the diaphragm that attach to the inside of the spine are restricted by tensions in the surrounding muscles. Then the auxiliary muscles of breathing have to work extra hard to compensate for the lack of freedom of the diaphragm and may even tighten up, restricting the breath further. The Transverse Abdominis Exercises I and II will strengthen the middle to upper part of transversus, providing a natural shelf for those tendons, allowing the auxiliary muscles to release. This is one of the areas that provide support for the voice for singers—and for the rest of us too—the speaking voice needs as much support as the singing voice.

Breathing Exercise for Diaphragmatic Problems

Breathing Exercise for Diaphragmatic Problems

Diaphragmatic problems include tightness in the tendons of the diaphragm; inability to open the side ribs; pushing the breath; hypertension of the sternum; lifting the chin up in an effort to breathe; lower back shortening and lower back rib area weakness.

The pattern in this exercise will make serratus posterior and anterior work together in a way that will open the ribs to the side, forcing the intercostals to engage, and the various muscles involved in stabilization of the rib cage (quadratus lumborum, the serratus group, obliques, lats, and so on), have to coordinate to use this pattern.

You’ll have to do the exercise for at least 5 minutes, preferably longer—up to 15 minutes—to feel the effects kick in. Keep your back straight, lift the back ribs, and support as you need. You may feel a “stitch”-like pain in the sides as the diaphragm releases and the correct muscles engage. Slow down if you need to, but try to work through the sensation—it’s usually just a sign that the muscles involved are starting to strengthen.

1. Sit with your back straight, any way you are comfortable. Lengthen your spine, close your eyes if you can, but keep looking straight ahead, even with closed eyes. Press your palms together by your chest until you feel the bottom tips of the shoulder blades engage and slightly pull down and toward each other.

2. Keep that straight pressure, and with palms together, breathe in and out quite fast through an O-shaped mouth (pursed lips) (fig. 9.9). The cheeks will suck in a little. The lips are engaged and the O-shape is about the size of the circumference of your thumb. Keep your lower back ribs lifted, side ribs engaged, and the bottom of your shoulder blades engaged.

Fig. 9.9. Breathing exercise for the diaphragm

3. Keep breathing, with equal time for inhale and exhale (about 1 second each). All breath is through the mouth. Breathe as vigorously as you can, for at least 5 minutes.

4. Release, with slow nose breathing, for a minute or so after.

Breathing through Water

Breathing through Water

This simple exercise can help asthma. It will also increase cardiovascular strength faster than any other exercise. To do it, simply inhale through your nose, and then exhale slowly through a straw into water (fig. 9.10). The bubbling will tell you if you stop exhaling. Your exhale should be slow and even. Build up to 60 seconds for the exhale.

Fig. 9.10. Breathing through Water