This chapter is written for people with disfigurements. If you have body dysmorphic disorder (BDD) or an eating disorder and are preoccupied by a minor defect in your appearance you may be interested to know how people with severe disfigurements cope with an unusual appearance. This is something that health professionals have found interesting too. You may assume that someone with very severe burns scarring is going to find life more problematic than someone with, say, minor scarring from acne – but in fact this is by no means inevitable, as shown by the following case studies. Someone with BDD might find it helpful to assume, temporarily, that the ‘flaw’ in their appearance is as bad as they think it is, and then follow the advice outlined in this chapter.

Geraldine has very severe burn scarring caused by a house fire. The scarring is visible all over her body. One of the practical problems she has is keeping cool in the summer, since she cannot lose heat though her skin by sweating. The easiest thing is to swim. She does so several times a day when it is very hot. She knows that people notice her scarring and sometimes ask about it. She has therefore developed some good answers to questions, which give a minimum of information but satisfy other people’s curiosity. ‘I know I am unusual, and I understand that people are curious, but I don’t intend to tell them my life story’. Geraldine is confident, successful and good fun to be with. She has a partner and her appearance is not a barrier to living a full life.

Louise has very minor scarring on her face following a car accident. She is very aware of it, but it is hardly noticeable to other people. She manages this by wearing a baseball cap pulled down low so that no one can see her face, and she avoids eye contact or speaking to other people. She has stopped working and any kind of social activity and does not go out. Her life has changed dramatically and her mood is low. She is very pessimistic and feels that her chances of a happy life are now over. She is not unusual in feeling devastated by a relatively minor change, and what makes this worse for her is the well-meaning relatives and friends who tell her that she is making a fuss about nothing and that, compared with other people, there is nothing really wrong with her.

Even though Geraldine rates her condition as far more noticeable than Louise, she is less preoccupied by it. The target of treatment for Louise will be to reduce her level of preoccupation and worry; Geraldine, of course, does not need any treatment!

Many people with very obvious disfigurements live totally normal lives – so what is it that makes concerns about appearance such a problem for some people and not for others? Why is Geraldine able to manage, whilst Louise is finding life so hard?

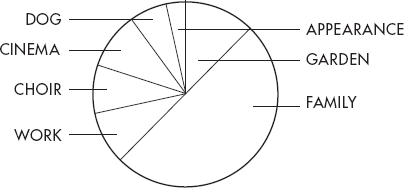

The answer has a lot to do with the value we place on appearance. In the diagram below, a circle has been divided up to represent the importance of different aspects of her life to Geraldine’s identity.

In Geraldine’s pie chart (above), appearance occupies quite a small ‘slice’ of the pie. Most people are concerned about fitting in with their peer group and not standing out in a negative way. For teenagers, this slice might be larger or, for very fashion-conscious girls, part of this slice might be about being slim. But there are lots of other slices too. More important, to Geraldine, are ‘my family’ and ‘my garden’. ‘Work’ is a slice, ‘cinema ‘ and ‘choir’ are additional slices, and so on.

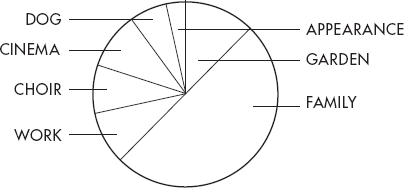

For some people, the ‘appearance slice’ can take over the whole circle. The preoccupation with a particular feature and the search for a means of changing it become more important than anything else in their life. Before treatment, Louise’s pie chart looked like this. She felt very self-conscious and unable to cope with the idea that people would notice her face. Her self-esteem had sunk very low. After treatment, her preoccupation with her appearance was much reduced, she was able to go out and her social life started to take up more space in the circle again.

Psychological treatments aim to help people manage their concerns about their appearance and gradually shrink their appearance ‘slice’ back down to a small or moderate level of importance. Self-esteem and self-confidence depend on far more than what you look like. We all like to feel that other people think about us in a positive way. Although we may believe (and the media encourage us to believe) that appearance has a lot to do with this, our behavior and personality are actually far more important in how we are regarded by other people. One of the most attractive things about other people, and something that makes you feel good about yourself, is being comfortable in social situations and able to demonstrate an interest in other people rather than yourself. People who we know cope well with a visible difference or a disfigurement tend to be those with very good social skills.

In this chapter, we look at the particular challenges faced by someone who has an obvious facial difference, together with some practical ways of meeting these challenges. Even if you do not consider yourself to have a facial difference, it is worth reading this section and using some of these skills and strategies yourself. They will help you to focus ‘out’ on what is happening in social situations, rather than focusing ‘in’ and becoming preoccupied with what people are thinking about you. This is the key to becoming more comfortable with other people and gradually building your self-esteem.

Visible difference is more common than we think. Severe burn injuries, accidents and traumas, such as dog bites, account for some changes in the way people look. Skin conditions, cancer and other diseases account for others. Thyroid gland problems can have an impact on the appearance of your eyes, and rheumatic diseases can change the appearance of your joints, particularly in the fingers. Steroid medication can alter the shape of your face and body; chemotherapy can cause hair loss. Surgery to remove cancer can leave scars. There are therefore many people who experience visible changes in their appearance related to accident or illness.

A second group of people are those who are born with a visible difference. This includes conditions such as cleft lip and palate, birthmarks such as port wine stains and other cranio-facial syndromes which affect the way in which the bones of the skull are fused together and therefore the appearance of the face. Research has demonstrated many similarities between all these groups in terms of the kinds of challenges they face in day-to-day life. We therefore treat any problems that arise in the same way.

Staring by others is commonly reported. The human brain is hard-wired to take note of anything that is unusual or outside our experience. You may have noticed babies and children constantly gazing at objects and people, as they build up a picture of the world. This curiosity never leaves us – we can learn some social skills that prevent us from staring at others, but most of us will notice, or do a ‘double-take’, when we see someone who looks unusual. It is important to note that this is a response stimulated by curiosity. But it can feel like a problem if it is accompanied by comments, questions or a whispered aside to a companion.

However, some people feel they are being stared at, when the problem is more to do with being excessively self-conscious and worrying about what others are thinking. You may only be sure that people are staring, for example, if it is confirmed by someone else who is with you, or the person staring is asking questions or pointing at you.

Questions are common. Curiosity is often followed by the impulse to ask more. ‘I hope you don’t mind me asking – but what happened to you?’ There are not many people with a visible difference who are not familiar with this response from other people. Choosing how to answer this question is important in determining whether the encounter is going to be a positive one.

Comments, either directly to you or about you to others, are often infuriating, even if kindly meant. ‘I think you are so brave, dear’ is designed to be reassuring, but can feel patronizing and unhelpful. ‘People like you should stay at home’ tells you far more about the ignorance of the person who makes the comment than the person it is made about, but can still be experienced as hurtful and aggressive.

Many of us underestimate the luxury of being able to walk down a crowded street and know that no one is taking any notice of us. The sense that we stand out, that others notice us or pay us special attention, can be uncomfortable. Indeed, people whose faces are well known, who have become celebrities, often complain about this kind of intrusion. Attention does not have to be negative to impact in a negative way – it simply needs to be unsolicited, or outside your control. The fear of standing out, of people looking at us, is extremely common in all kinds of body image disorders and can lead us to make unhelpful choices in how we respond. The easiest thing is avoidance. If you stay at home or avoid crowded places, then this apparently solves the problem – except, as we have seen elsewhere in this book, it is important to confront fears, by learning the skills that allow us to stay in situations we find difficult. By doing so, we become able to do everything that anyone else can, without constantly worrying about whether people are looking at us or what they think.

For many people with body image concerns, it is the fear of standing out, of looking unusual or ‘ugly’, that preoccupies them and prevents them participating fully in social activities. For someone with a visible disfigurement, the fear that someone will notice is often a reality. People do notice, they are curious and they do ask questions. But this is manageable. In treating people with a visible difference, we work on the basis that intrusions will definitely happen so we are going to learn how to manage them – from dealing with staring to answering questions in different ways. Mastering these skills is not difficult – in fact they are useful life skills for anyone to develop. For most people with body image problems, working out how you would deal with the thing you fear most is far better than simply dreading it happening and avoiding other people in case it does. This might mean practising a role-play with a friend so you will know how to cope with questions or comments.

Before we go on to think about managing an unusual appearance, it is worth considering some key pieces of research that tell us more about how the way in which how you think, your beliefs or expectations, colour the way in which you interpret what happens around you.

In the 1980s, psychologists interested in social research used make-up to mimic different kinds of visible difference including port wine stains (purple marks) on the face and facial scarring. They were interested in measuring the experience that people who had these conditions were reporting. The participants in these experiments were asked to report back on how it felt to stand out in a crowd – and they reported many experiences of discomfort, staring by others and generally feeling conspicuous. This seemed to support what people with a visible difference had been telling us. However, half this experimental group did not in fact appear disfigured at all. Before sending them out to gather data, the researchers had removed the make-up with a solvent, whilst pretending that they were ‘fixing it’ or setting it so that it would not rub off. These groups reported just the same experience of intrusion, and staring from others as the group who really did look different.

How can we make sense of this? The best explanation is that we tend to see what we expect to see. So if we go into a situation with a preconceived idea of what is going to happen, it is very easy to interpret what happens in line with this. There is another explanation. It could be that when we expect a hostile or intrusive response from others, we change our behavior, and it is this altered behavior that attracts people’s attention. For example, we avoid eye contact, walk with our head down, pull a baseball cap low over our head – all patterns of behavior that are very understandable when we feel conspicuous, but which have the opposite effect from that intended; they attract rather than reduce attention. Whilst both of these theories explain what the researchers discovered, they are not mutually exclusive – in other words the finding might be due to a little of both.

The psychologist Professor Nichola Rumsey was very interested in the second explanation – the idea that people change their behavior when they have visible differences. She continued to carry out research into this ‘behavioral’ explanation for the problem of facial difference. She was intrigued, partly because she had observed ‘avoidant’ behavior in people who had problems managing facial difference, but also because she believed that social skills training (learning to behave differently in social situations) might be a way of teaching people skills that they could use to cope more positively. By chance, she met James Partridge who had set up a charity helping people with facial disfigurements, following his experience in managing his own burn injury. They discovered that they had come to the same conclusions from their completely different backgrounds in the subject. Good social skills could profoundly alter and improve the experience of facial difference. The charity Changing Faces (see page 376) then developed this social skills idea further, whilst Professor Rumsey evaluated their findings and demonstrated that their ideas really worked.

As you have seen in this book, CBT is a means of changing the way you think about a problem and how you actually behave. Psychologists working in this field have developed the CBT approach to include social skills training, and have shown that this is the most effective way to help people who do not cope very confidently with a visible difference. The aim is to teach people to manage as effectively as those for whom having a visible difference is not a barrier to achieving all that they want to. Changing Faces has made a huge contribution to the development, evaluation and publicizing of these approaches, and the following section draws on their work.

We have seen that certain kinds of ‘thinking styles ‘ or unhelpful patterns of thinking can become automatic (see Chapters 4 and 6). Many people, particularly if their appearance changes suddenly, can ‘write themselves off’ and convince themselves that they no longer have the opportunities that the rest of us may have.

‘All-or-nothing’ thinking often lies behind this.

Examples include:

‘No one is going to employ someone who looks like this’

‘I am never going to get a girlfriend looking the way that I do’

‘None of my friends will want to know me any more’

‘How can I take the children to school when I look like this?’

These are all real examples of all-or-nothing thinking that can lead to people writing themselves off.

One way of reducing the harm that these negative thoughts can cause is by keeping a record of them on paper. You can then distance yourself from such thoughts and not engage with them (see Chapter 6). You can also examine the evidence for each belief and see if there is an alternative. For example, for the belief ‘No one is going to employ someone who looks like this’, is it true to say that no one would employ someone with a visible difference? Clearly not. Many people with an unusual appearance have jobs just like anyone else. So an alternative belief might be:

‘Most employers are looking for someone with good skills and experience who is prepared to work hard and who is reliable.’

Similarly, the belief ‘I am never going to get a girlfriend’ is about partnerships. Many people with a visible difference are married or in happy long-term relationships with others. So a more realistic belief might be:

‘Happy relationships are based on who you are and not what you look like.’

The belief ‘None of my friends will want to know me any more’ can be challenged with the alternative belief:

‘Good friends enjoy being with me because they have a good time – not because of how I look.’

Finally, children are far less interested in appearances than adults are. Given a good explanation, and provided they see that you are coping well with your altered appearance, they will cope well too.

Note that these alternatives avoid the ‘all-or-nothing’ patterns that are typical of the unhelpful beliefs. We are not challenging the idea that finding a partner or a job may sometimes be harder – we live in a very appearance-conscious society where some people may make judgements that are overly dependent on appearance. But it is not true that all or even most people think in this way.

Remember the example we gave earlier with the make-up experiments, of how anticipating a problem can become a self-fulfilling prophecy? This is very true when it comes to finding a job or developing a relationship. If you write yourself off before you get there, this will come across in the interview. If you appear confident and self-assured, this will act in your favour. It is very tempting to blame lack of success on appearance. But the reason you do not get a job is equally likely to be because there was a better candidate with more experience. The reason someone does not want to go out with you may equally be because you do not share the same interests or think very differently about important issues.

Another very common example of all-or-nothing thinking is the belief:

‘Everybody’s staring at me!’

(This is so common in fact, that the charity Changing Faces has produced a booklet with this title.) Again, a cognitive behavior therapist would examine the evidence for holding this belief. One way of doing this is to design a ‘behavioral experiment’.

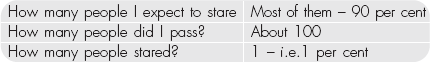

George, who was anxious about being stared at, conducted the following behavioral experiment: he decided to count how many people he passed on the way to his office from the train station. He also kept a note of how many people stared hard in his direction.

George noted that he had passed about 100 people and only one person had stared at him. So he was easily able to challenge his all-or-nothing thinking. In fact, 99% of people took no notice of him. (There was a nice bonus to this experiment; the person who had been staring hard at him finally came up and asked him directions. So, far from being identified in a negative way, George had been identified in a positive way as someone who looked friendly and helpful).

Other common types of thinking errors that characterize people with appearance-related concerns are described below.

This is the tendency to think that every mention of appearance is somehow stimulated by seeing you. For example, if someone comments that someone else is looking fatter, has let themselves go, should get a haircut – or anything similar, you may think:

‘They are really thinking that I should do something about my appearance.’

‘It is really my nose that is making them think about another person’s appearance.’

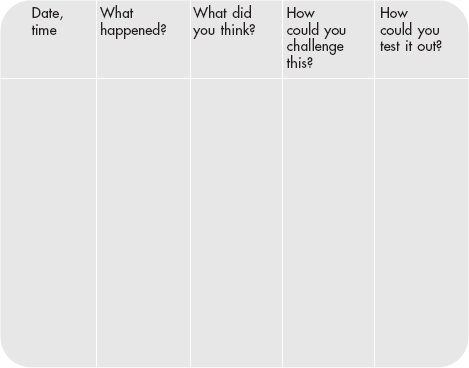

Again, you can challenge these thoughts by looking for evidence to support them, and then find an alternative explanation that is equally likely to account for what was said. We have provided a form below that you can use to consider an alternative explanation, which can then be tested out in an experiment.

Here is an example of someone using this form, who had a very large and distinctive nose characteristic of his racial group.

When he asked this question, his friend responded by telling him about his sister who had recently had a breast reduction operation. He was then able to reduce the strength of his belief that it was his appearance that had triggered the conversation

Before considering behavior and how to change it, it is worth making a particular point about appearance. We have talked about ‘write-off thinking’ above. However, one common mistake people can make is to think that, because they have a visible difference, it is not worth bothering with other aspects of their appearance. This could not be further from the truth! If you give other people a strong message that you have given up on yourself, why should they be interested in you?

So – you do need to have your hair cut or styled regularly. You do need to dress in a way that is appropriate for your lifestyle. Wearing appropriate clothes, looking tidy and ensuring that you do not have food spilt all down you is important. Your personal hygiene should be good. Making an effort to fit in with your peer group will help people to see you for who you are and not as an outsider. In this context, it is important to note that sometimes clothes or make-up designed to disguise a feature can have the opposite effect. Baseball hats are particularly unhelpful and we work hard with our patients to get rid of them. In the UK, people associate them with aggressive behavior and you can easily make yourself look threatening, especially if wearing them is combined with poor eye contact. (It usually is – reducing eye contact is why people wear them!) Look back at the example of Eileen in Chapter 9 (page 216). Similarly, wearing very large jackets in the summer can draw attention, rather than disguise problems, and unskilled use of camouflage creams can make a facial disfigurement more, rather than less, obvious.

This is a common pattern that people fall into. So, having noticed someone glance your way, the negative automatic thoughts follow this sort of course:

‘Oh no, I hope she doesn’t notice my face. She is thinking how awful I look and wondering how she can get away from me. She is just like everyone else. What’s the use of coming to places like this, it always ends up the same way. I will never fit in; I will never have any friends or be able to enjoy my life. What’s the point of living like this?’

You can see that the first automatic thought has triggered a whole spiral of further negatives so that just the thought of being noticed has led to the feeling that life is not worth living. You may then start you to brood, as described in Chapter 4. This catastrophic outcome has evolved in six steps from the simple question of whether or not someone has looked your way! This is also an example of writing negative scripts for other people based on no evidence. In fact when we do some behavioral experiments, we often find that people have not noticed anything unusual. They may find it hard to describe the person who believes their appearance to be so distinctive. Or, they may express surprise that the person is so worried by it, because it makes no difference to the judgments they make about them. It is therefore really important to stop yourself and challenge the automatic thought at the start, before you allow these unhelpful beliefs to depress your mood and change your behavior.

Social skills are a good place to start. We talked about making the most of your appearance earlier. Go through your wardrobe and check anything that needs either washing or mending. You do not have to always wear black. One of the things we encourage people to do as they become more confident is to wear clothes that are more colourful and help to challenge the idea that you are trying to hide. How do you style your hair? It can be tempting to wear a long fringe or to try to drape your hair over your face to cover a facial condition, but keeping this in place means walking with your head down. Like hats, this is less helpful than it might seem. If you have a disfiguring condition elsewhere on your body, then wearing long sleeves and high necks can be automatic, but you can become dependent on them.

Veronica, who had a skin condition called vitiligo, developed patches on her skin that lacked pigment. She always used make-up to camouflage her skin. Veronica was worried that she would get constant questions from other people. As her skin condition progressed, she got fed up with the time it was taking to put on the make-up. She decided to try going out with her face bare. To her surprise, although people glanced her way, they really took very little notice of her. She decided that she would wear her make-up some but not all of the time. Now, if she is going to work, or if she is dressing up to go somewhere special, she wears it. But if she is home with her family or with friends she knows well, she does not bother.

This example illustrates the kind of cognitive errors that we described earlier. The belief that ‘everyone will notice and ask me questions’ and ‘everyone will think the marks on my skin are ugly’ were successfully overcome by putting them to the test.

How you stand is important. If you tend to look down and away from people, your behavior is not open and inviting. (Think how difficult it is to communicate with someone who wears dark glasses.) Try to make a conscious effort to stand upright and look straight ahead.

You will be amazed at the difference it makes when you look at other people and smile. This gives a positive message instantly! Sometimes when people have a facial condition making their face move either asymmetrically (more on one side than the other) or, for some people without a facial nerve, not at all, they are unable to smile or try to avoid it. Using other forms of communication – commenting on the situation or using touch – can provide alternative ways of signalling pleasure. For those of us who can smile, responding to others in this way, on the bus, in a queue, in the street, gives a very different message from hurrying past, head down.

Eye contact is the basis of communication. We use it to signal interest, that we are listening, and whose turn it is to speak in a conversation. Trying to avoid other people’s gaze will always come across as negative, giving a clear signal that you do not want to engage in any kind of contact with them. It is very easy to misinterpret other people’s gaze as intrusive – staring at a feature you dislike – when in fact people are simply trying to talk to you. There are lots of good books and information about improving social skills. For instance, Changing Faces (see page 376) publish information and run workshops where you can practise developing your non-verbal communication skills.

People often describe the fear of going blank in social settings – being unable to think of what to say. This is more likely to happen when you are focused ‘in’ on your own appearance and how people are responding to you, rather than listening and involved in what people are saying. Anxiety tends to heighten the temptation to ‘self-monitor’ so it can be doubly hard to relax and really focus on what is going on around you, rather than other people’s reactions to you. (See Chapter 6 for some strategies to help you overcome problems with inattention.)

It can also be hard to get going again if you have been avoiding social situations because of concerns about staring or questions. (This is another reason to avoid withdrawing from others. It is much harder to pick up your social life again if you have let it stop completely rather than to keep it going, even if it’s at a slower pace).

Developing verbal skills is mainly a matter of practice but there are some simple things that will help. First, it is helpful to listen. What do other people talk about in different settings? The easiest place to start is at work or in a situation where you have lots in common with the other people there, or are with a group of people that you know well. You might have friends in common and can ask how they are. You might have a job in common and can ask about that. Asking people about themselves is a very good way to get a conversation started. So asking if people live nearby, what they do for a living, whether their children go to the local school and similar questions are all ways of initiating a conversation. Similarly, topical subjects are things that other people will have a view about. The result of the latest big football match, the election, the price of petrol, or news headlines are all good places to start.

It can be a good idea to identify something about the other person that you can use as a question if there is a pause in the conversation. So, you might notice that someone is wearing a particular piece of jewellery or an interesting tie. T-shirts often have slogans or flags or something you can comment about. If someone looks tanned you can ask if they have been on holiday. (Note that, in this context, it is not surprising that people ask about your appearance if it is something that stands out – it is something about you that is unusual and therefore an ideal way of getting you to talk about yourself. Other people are simply using the same tactic as you are using yourself.)

Practising with a friend is good way to build your skills and confidence. Try these role-play exercises:

1. You are arriving at a crowded party. You can’t see anyone you know. Another chap is standing on his own, looking as if he does not recognize anyone. He is wearing an Arsenal football shirt. Ask your friend to play this role. Now you go over and start a conversation with him.

2. Imagine that you have broken down miles from anywhere. You phone the AA, but the mechanic can’t mend your car. He calls for assistance and decides to wait with you. What can you talk to him about? (There is a good chance that he is interested in cars!) Ask your friend to role-play the AA man, and see how long you can sustain the conversation.

We have already seen that questions from others are likely, but are related to curiosity and not a negative judgement about you. However, it is important that you do not feel trapped into giving away more information than feels comfortable. You do not have to ‘tell ‘your story’ to other people unless you want to. We would advise you to develop three different ways of answering questions about your appearance.

First, think about answering the question:

Q: ‘What happened to your face?’

A: ‘I was in a house fire. It started at 2.00 in the morning and the first thing I remember is waking up and all the heat and the noise. My mother ran into the room . . .

This kind of answer is the full, detailed and often lengthy one. It is best reserved for the medical team who have been involved in your care and those very close to you when relevant. However, interestingly, for people who worry about answering questions about their appearance, it is often the only one they ever use – with the result that they feel conspicuous and as if their private life is an open book to anyone who wants to know. Not surprisingly, they dread that opening line ‘I hope you don’t mind me asking, but...’

The second answer is the complete opposite. It is a simple response which closes down the questioning firmly, whilst giving little or no detail.

Q: ‘What happened to your face?’

A: ‘That’s a long story. I’ll tell you about it sometime.’

Or

A: ‘It was years ago – you don’t want to hear all about that.’

Together with firm eye contact and a smile, both these answers work superbly at turning off the questioning. They are particularly effective if you then switch the attention to the questioner, for example:

Q: ‘What happened to your face?’

A: ‘That’s a long story. I’ll tell you about it sometime. I hear you’ve just come back from America. How long were you there?’

The third way of answering the question is to give a more general response – about your condition rather than about you. For example:

Q: ‘What happened to your face?’

A: ‘I was injured in a fire. Luckily, now that smoke alarms are available, injuries like mine are far less common.’

It is a really useful exercise to write down some of these alternative answers and personalize them so that they apply to you. Then practise, and see how much more in control of the situation you feel. There are no right or wrong answers, although some answers tend to invite more questioning. For example, look at these answers to the question:

Q: ‘Why are you wearing that scarf on your head?’

A: ‘I have my reasons!’

Or

A: ‘I’ve had a small operation and I am keeping the stitches covered.’

The first answer invites all kinds of speculation about what is under the scarf. The second answer gives a very simple explanation. Any further questioning can be managed with the ‘turn off the questions’ approach above.

Answering children’s questions is very straightforward. They say exactly what they think, but they are equally happy with a simple explanation.

Q: ‘Why have you got a funny arm?’

A: It’s because I was burned in a fire. So don’t play with matches, will you?’

Sometimes humour can be helpful.

Tom, who is in his early twenties, was recently asked how he had lost a finger. To which he responded: ‘it wouldn’t fit up my nose so I cut it off!’.

This is a great reply! It made the questioner laugh, gave nothing away and made Tom feel comfortable and in control. You will find as you develop your own answers, that there will be certain favourites that you use again and again, and then some new ideas that you add in. The aim is to have them at the tip of your tongue so you are never caught out. Sometimes you can be ambushed by the question that comes in the middle of a conversation about something else, but, provided you have an answer ready, you won’t be caught unawares.

Try using the chart below to plan some good replies. Think about some questions that people have asked you. What did you say? What could you have said instead? Try developing three different ways of answering the question, one with lots of detail, one which closes down the questions and one which distances you from the subject, as above.

Sometimes it is actually easier to answer questions than to be in a setting where you can see someone is staring at you, but does not ask. Often when they get into conversation with you, the curiosity will pass. People may become firm friends with others without ever discussing why one of them has a visible difference, and over time it simply becomes insignificant. However, sometimes the staring can be very intrusive. Sitting on a bus or tube with a pair of eyes that keep drifting back to your face is annoying. A firm stare back is often very effective. Or a question:

‘Have we met before? You seem to be trying to remember who I am.’

An aggressive response, though sometimes tempting, is not usually helpful.

Distraction is another very easy way to focus away from the situation. A newspaper or book to read, particularly if you can hold it up and interrupt the staring, is helpful. A ‘shoe review’ when you estimate who has the most expensive trainers or exotic sandals is a simple distraction. You can also use visualization methods to imagine shrinking down the person into a tiny little figure or putting them into a different context (for example, in their pyjamas). All of these strategies will allow you to feel more in control of the situation and, as you feel able to manage more situations, so going out becomes less of an ordeal.

Changing Faces (see page 376) is a very good source of more ideas about managing staring, comments and questions. In addition to written information, they have a website and video materials and are developing on-line interactive programs that help you to practise different social situations before you start doing them for real.

The key to successfully managing a visible difference is to take a positive approach to social situations, work on developing your social skills and then practise them in a graded way. By this, we mean tackling some of the things you find easiest before tackling something harder. Fran’s case is a good example.

Fran had been bitten by a dog and had a very visible ‘V’-shaped scar on her cheek. She was a very stylish woman in her thirties who liked clothes and make-up and was devastated by this change in her appearance. She stopped work, stayed at home and became increasingly depressed. Her greatest fear was that, if she went out, someone would notice her face and ask about it.

We started treatment by developing some answers to questions. Fran settled on a very simple answer:

Q: ‘What happened to your face?’

A: ‘I was bitten by that Alsatian at number 32’.

We then designed a ‘hierarchy’ of exposure tasks (as in Chapter 7) , which is a simple ladder with easier items at the bottom and harder items as you climb each rung. Fran’s ladder looked like this:

Fran then carried out each step and repeated this until she felt comfortable doing it. She very quickly managed number one. She then spent a week going up to the shop and back every day but without going in. Gradually, her anxiety about going into the shop lessened. She then went in and picked up a paper and came home. She repeated this twice more and then went up to number three. Fran successfully completed this treatment and went back to work. There is an interesting aspect to Fran’s program. When she got to number 6, she waited patiently in the queue rehearsing her answer to the question she was expecting – and nothing happened. In the end, she got so tired of waiting that she pointed out her dog bite herself. ‘What do you think of this then? I was bitten by the dog at number 32!’ The shopkeeper had noticed, but had politely refrained from asking. Fran laughed as she told me about this. You do not necessarily have to do the same thing, but it does illustrate how taking control of the situation had so lessened her anxiety that she felt able to introduce the topic of her face to a stranger. This was very different from how she imagined herself behaving at the start of her treatment.

If you find certain situations very daunting, it is worth trying to work out your own hierarchy like Fran did. Take it steadily, with not too big a jump between one step and the next. Then make sure you only progress to the next rung when you are completely happy on the rung below. It does not matter how long this takes you. Regular practice is more helpful. Doing an activity every day means that you will progress much faster than if you do it once a week. Be ready for a bad day but don’t let this put you off. You can often have an experience that does not go so well, just before a real breakthrough in behavior change. Go back to the rung below to build your confidence, and then try again.

All the examples given in this chapter are real examples drawn from our clinical experience. They all have something else in common. All these people went on to successfully change their behavior and live normal lives without surgical removal of their disfigurements. They all had surgery at some point in their lives, and some were able to improve their appearance slightly. But all of them learned to live with a visible difference for which no further surgical treatment was possible.

Plastic surgery achieves an enormous amount for people who have disfiguring conditions. However, the media can sometimes portray surgery as offering ‘magic’ solutions. All surgery has its limitations. All surgery leaves a scar, but some scars can be concealed better than others, for example, in the natural contours of the skin. It is impossible to completely modify a disfiguring condition so that the person looks exactly as they did before an accident. Even cleft lip and palate repairs, which produce very good results for children born with this craniofacial condition, will leave a fine scar.

At some point, a decision must be made about whether the benefits of further surgery are outweighed by the costs. Going on and on with surgical procedures is no guarantee of being able to restore appearance. The real goal, after all, is to be able to live a normal life. So draw a line under surgery when your surgeon suggests it, or when you yourself feel that the results are ‘good enough’. Addressing any challenges that you still face using a psychological approach, like the people in the examples we have given, is a very healthy way forward.

This chapter has considered the special case of disfiguring conditions, within the context of body image concerns. We have seen that objectively minor conditions can cause considerable distress, whilst other people cope with a very significant difference without any distress.

Positive coping strategies, taking the initiative, good social skills and social support are helpful. Avoiding difficult situations, increased social withdrawal or coping using non-prescription drugs and alcohol are not helpful.

CBT, which helps you challenge unhelpful beliefs, develop social skills and practise positive coping behavior can enable you to manage your condition even when surgery has no more to offer. This is achieved in a gradual way by tackling difficult situations step by step. Staring, comments and questions are intrusive but everyone can learn to manage them.

For people whose concerns are less to do with objective difference, and more to do with an internal dissatisfaction with appearance, these approaches are still very helpful. The preoccupation with appearance, which is typical in BDD, can be a real barrier in social situations. If you believe that other people are distracted, for example, by your nose, as you are, then it becomes very difficult to focus on the situation, rather than on other people’s response to you. Anxiety about how to interact in this situation means that it can be hard to concentrate on what is really happening and not to write an agenda based on what you think or fear might be happening. For this reason, the section on social skills will be helpful for you too. It is also useful to note that there are answers to appearance-related anxiety that do not involve surgery, and that people with a very obvious visible difference can live just as happily and successfully as anyone else.