2 Shut In, Shut Out

Imagine you work in an office with other people. One day, you arrive at work to discover a new rule is in effect. Maybe it’s sent to you by the CEO of the company, or simply printed on a poster by the coffee machine:

You can’t say “you can’t play.” Effective immediately, if anyone wants to participate in your project you must agree to let them join. Yes, you will still be held accountable for the success of your work.

How would you react? Although the exact results might vary, there’s a good chance that most adults might mirror the reactions you’d find with a group of young children: anger, defiance, and a few tears.

In her book You Can’t Say You Can’t Play, teacher Vivian Gussin Paley recounts what happened when she proposed this rule to her kindergarten class.

Before enacting the rule, she and her students speculated on what might happen. Their own reactions ranged from fear to excitement. Fear that their games would cease to be fun. Fear that an overwhelming number of people would want to join in, thus ruining the game. Or that unwanted people might intrude into the game. And the children who were most often excluded were excited about the protection the new rule would provide them.

Paley was inspired to introduce the rule after teaching countless students. Every year a few children in each class would be consistently excluded, sometimes to an extreme. As her former students became adults, they would recount stories of rejection as the most difficult times in their education. She created the rule as a way to study why this happened year over year, looking for ways to disrupt the pattern. Paley writes:

Exclusion is written into the game of play. And play, as we know, will soon be the game of life. The children I teach are just emerging from life’s deep wells of private perspective: babyhood and family.

Then, along comes school. It is the first real exposure to the public arena. Children are required to share materials and teachers in a space that belongs to everyone.

Equal participation is the cornerstone of most classrooms. This notion usually involves everything except free play, which is generally considered a private matter. Yet, in truth, free acceptance in play, partnerships, and teams is what matters most to any child.1

Paley’s classroom of kindergarteners can help highlight why exclusion dominates many shared environments. Their unfiltered honesty gives us a clear view of why exclusion persists and how to evolve it. It starts with language.

The Circle

Many cultures have different approximations of the words “inclusion” and “exclusion,” with unique origins and exact meanings. For the purposes of this book let’s take a closer look specifically at the English words “include” and “exclude.”

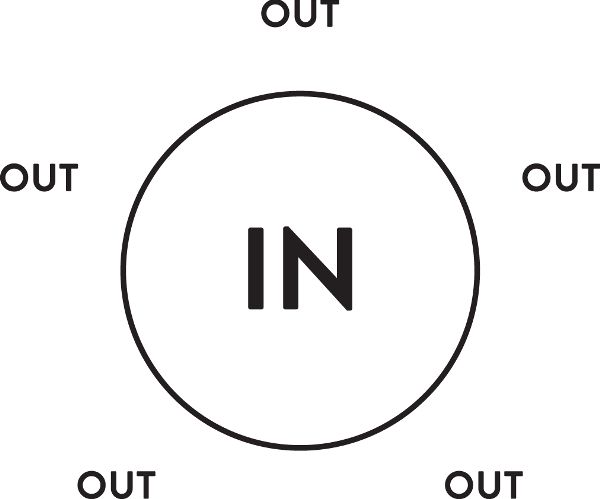

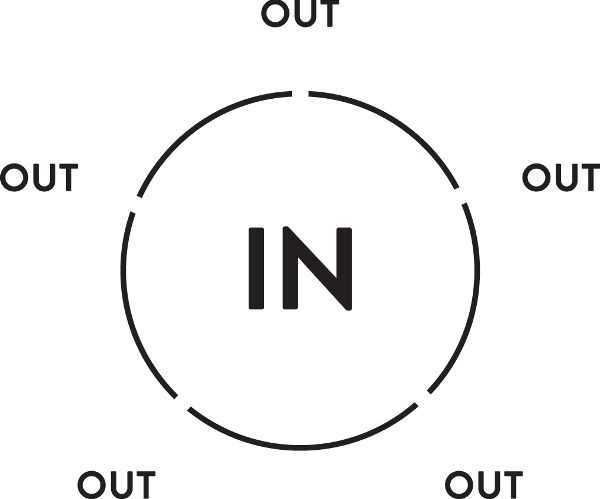

Both words are based on the Latin root claudere, which means “to close or shut.” It represents a literal enclosure, but it also represents a mental model of separation. The most common image that comes to mind is a boundary created by a closed circle.

A shut-in-shut-out model of exclusion is centuries old and leads to a fixed way of thinking about inclusion.

Many modern-day societies use “inclusion” and “exclusion” to describe aspects of everyday life. Over time, such circular boundaries have been applied in new ways. They have been used to protect types of power and to separate people by gender identity, skin color, ability, language, religion, and other facets of human difference.

As a result, these societies also inherited the shut-in-shut-out mental model represented by these words.

When inclusion means so many different things to so many different people, understanding how to build it is far from self-evident. When companies talk about having an “inclusive culture,” it’s unlikely they want to shut people inside their walls. Inclusion is generally meant to express something more closely related to equity, empathy, access, or a sense of belonging. Somehow this little word has come to represent a vast world of good intentions, but if we can’t describe exactly what it means, how can we start building it?

In the shut-in-shut-out model, what is the goal of inclusion? Is it for the people inside the circle to graciously allow people outside it to join them?

Are people who are shut out trying to break into the circle? Is the goal to obliterate the circle altogether and intermix freely in a utopian manner? The models that we use to describe the nature of exclusion inform how we think about solutions.

The circle encapsulates things that we want to protect, often power and possessions. The people we consider friends. The resources we believe are critical to our survival and success. As kids, we guard these things with phrases like:

“We already have enough people for this game.”

“The game already started, we can’t stop for you.”

With a shut-in-shut-out model of exclusion, inclusion becomes a struggle between those in and those out.

“You don’t have the right kind of toy to join us.”

And yet, after the new rule was put into effect, Paley’s students adapted their play with minimal conflict. The change was most difficult for a small number of children who consistently instigated games, set the rules, and enjoyed being the boss.

The children who had been most consistently excluded were no longer isolated. How they saw themselves and their contribution to the classroom shifted in positive ways. We’ll explore this benefit in the next chapter along with the physiological effects of social rejection, such as physical pain and depression.

However, the subtlest and broadest benefit was that every child in the classroom gained new friendships, and the games they played got a lot more interesting.

When they could no longer exclude each other, they learned how to adapt their games. They also adapted the roles they were willing to play within a game. They tried on different identities. The kid who was always the villain could now be the newborn baby. The heroes could be the villains. The father could be the mother. Despite all initial concerns, their games were still fun to play.

These childhood fears ring true in our adult lives. We meet the same concerns when improving the inclusivity of our workplaces, products, and public environments. Paley’s classroom experiment illustrates that exclusion isn’t based on a fixed circle.

It’s a cycle of our own making.

A Framework for Change

Unlike in Paley’s classroom, we don’t always have, or want, a higher authority posting rules on our walls to mandate our behavior. The good news is we each hold the power to make or break inclusion. The bad news is we don’t always know that we have this power, or what to do with it.

We each know what it feels like to be excluded. Sometimes we can recognize when someone else is left out. Yet we often have a very difficult time anticipating how people might be excluded in the future.

This is what makes inclusion so relevant to design.

A design has an intent. It’s meant for a purpose. The act of designing inherently requires thinking about the future ways that someone might use a solution. And it’s successful only when the recipient of a design confirms it has achieved its purpose.

Inclusion complements design as a way to align what a solution can be with what a person needs it to be. This dynamic is best described by Dr. Victor Pineda, a leader in accessible urban design and co-founder of the Smart Cities Initiative:

Inclusive design is about engaging with people that can be completely different than you, it stretches your imagination of what’s possible. It has a trickle effect, it has a multiplier effect in that it changes those people and, in a sense, changes society.

Because the fact that the designer thought about a wider group of people opens up for society to see these people that were once invisible.2

Dr. Pineda speaks from experience. He’s one of the most well-traveled people you’ll ever meet, having visited over seventy countries. As a person who uses a wheelchair he has expertise in navigating obstacles in public spaces. He has a combination of strategies, from personal assistants to assistive technologies, that are critical to each of his journeys.

He has an intimate understanding of how interrelated elements, from designed objects to city policies, can create and remove barriers to access. And what happens when they do:

Designers, whether they’re designing a school or software, hold the key to unlocking human potential. Because I want to give all I have to society. You can do that. You can change the rules of the game so the game includes me and includes my talents.3

What makes exclusion a cycle? It’s the enduring notion that “we shape our tools and thereafter our tools shape us.”4 What we produce has an effect on society, which in turn shapes the next set of problems we aim to solve. A solution becomes a barrier when it’s designed only for people with certain abilities. The brainpower and ingenuity of anyone who doesn’t match that design are simply untapped. When we create new ways for people to contribute their talents, their contributions influence everyone.

Exclusion is also cyclical because it’s constantly renewed by our choices. For example, changing the colors of a website could seem like a small adjustment. Or it could suddenly make that website inaccessible to nearly 8% of men and 0.4% of women who have color blindness.5 The cycle is always in motion and shifts with each design decision.

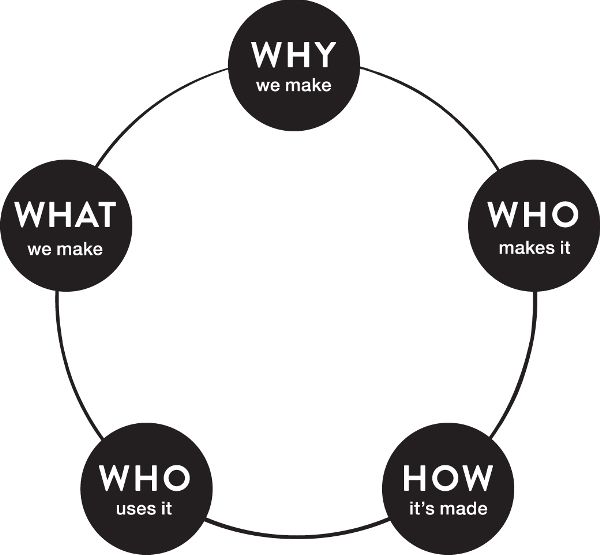

We will use the framework of a cycle to examine how we perpetuate mismatched designs and how to shift toward inclusion. There are five elements to this cycle, and each of them is interrelated with the others.

- ■ Why we make. We’ll focus on the motivations that are innate to the problem solver.

- ■ Who makes the solution. This is the problem solver, the person who is accountable for the success of a solution.

- ■ How we make. These are the methods and resources employed by the problem solver.

- ■ Who uses it. These are the assumptions that the problem solver makes about the people who will interact with, receive, or benefit from the solution.

- ■ What we make. This is what the problem solver creates.

You might notice that the cycle doesn’t include when we make. This is because exclusion can show itself at any moment in the development process. Conversely, the best time to start remedying exclusion is right now. It is most effective, and generally less expensive, to prioritize inclusion as early as possible and build inclusive solutions from the ground up.

The five elements that contribute to a cycle of exclusion.

But design rarely starts with a blank canvas. Nor does it follow a neat and sequential process. When inclusion is characterized as a separate category of activities reserved solely for the early stages of a design process, it can easily be deferred indefinitely. In short, right now is better than never.

That said, in chapter 8 we’ll take a closer look at examples of inclusive design. Some of these are modifications of existing solutions. Others were created by applying inclusive design in the early stages of a new business or product. We don’t need to tear down existing solutions to make inclusive ones. The cycle of exclusion is pervasive and ongoing. Similarly, a shift to inclusive design means we are constantly looking for and resolving mismatches through all stages of a development process.

As an individual or a member of a small team, you might have a high degree of control over all of the elements in this cycle. With practice, you can learn to recognize and remedy exclusion at your own pace.

Larger organizations often have a harder time coordinating the elements of this cycle. Sometimes the elements are isolated silos that are disconnected from one other. This issue is aggravated when leaders try to build inclusion through only one element of the cycle.

Leaders often focus on the single element that relates to their professional expertise. An engineer might focus on accessibility issues with the product they develop. A leader in human resources might focus on hiring practices. An information technology professional might focus on how to make communication tools work better between global teams that have different native languages.

The success of inclusion for each element is gated by the success of the other elements.

Hiring a new engineer whose first language is Mandarin and requiring them to use English-only tools could impede their ability to perform to their full potential. A team that consists of people with perfect eyesight might build a touchscreen interface for a camera without ever taking into consideration how it would work for someone with vision loss.

Whether by lack of awareness, siloed decisions, or simple neglect, it can be difficult for organizations to drive toward inclusion if they don’t have a full picture of how their existing culture perpetuates exclusion. As a result, the default state for most organizations is a cycle of exclusion.

The power to change that cycle doesn’t just belong to the person who starts the game, but to all who participate in it.

■ ■ ■

Takeaways: The Games We Play

- ■ The shut-in-shut-out model of inclusion can make it seem like exclusion is a fixed state, rather than an active choice.

- ■ Reframing exclusion as a cycle helps us recognize the ways that our design choices can lead to mismatches.

- ■ The five elements of the cycle of exclusion are interrelated. Each can be a useful place to start shifting toward inclusion.