3 The Cycle of Exclusion

What do a public bathroom and a smartphone have in common? From the standpoint of inclusion, they’re similar. The cycle helps illustrate just how much.

Public bathrooms are vivid examples of exclusion. An “accessible” bathroom is most commonly one that meets basic building standards for wheelchair accessibility. Architectural features that create access for someone who uses a wheelchair are critical, and mandated by law in some countries. And yet, the next time you visit a public restroom, take a moment to consider who, exactly, it is accessible to.

Here’s a cringeworthy example. There’s an increase in toilets that can only be flushed by waving your hand over a sensor on the back of the toilet. It’s a futuristic invention, complete with a friendly icon of a waving hand to demonstrate how to activate the toilet.

Unless, of course, you’re unable to see the icon and are expecting some form of button or lever to flush. One of the last things anyone wants to do is reach around a public toilet in search of how to flush it.

Here are a few more perspectives to consider. Are the door locks and toilet seats reachable for someone who’s under four feet tall? Or over seven feet tall? What physical features are required to access the sinks and faucets? Do the automated soap dispensers respond to people with a wide range of skin tones? Is it a safe space for people across a range of genders? How well does the space work for children and their parents? How well does it work for people with luggage? For a person with a broken ankle?

For a team that designs bathrooms these are important questions to ask. If someone on the team has experienced these kinds of exclusion, they likely have expertise that’s helpful to creating a better solution. If a team doesn’t have the experience, and isn’t held accountable for finding a solution, they will likely build a solution that excludes.

For bathroom visitors, often the person who needs to use the solution can’t simply choose not to use it. An exclusive design places a burden on people to find their own workarounds. A hands-free, sensor-enabled toilet leaves people searching the surface of a toilet for a handle to flush, or asking another person to help them. These can be dehumanizing experiences.

Public spaces, like bathrooms, serve universal human needs. They are access points for health, safety, education, economic opportunity, and Internet connectivity. It makes sense to have rigorous criteria that minimize exclusion in these spaces. But do designers need to be as mindful when designing technology? Absolutely.

Disability is critical to any conversation about exclusion. It touches everyone’s life, eventually. Yet disability is commonly misunderstood as applying to only a marginal percentage of the human population. This is simply untrue.

According to the World Bank, one billion people, or 15% of the world’s population, experience disability.1 To put it another way, there are over 6.4 billion people who are temporarily able-bodied.

As we age, we all gain and lose abilities. Our abilities change through illness and injury. Eventually, we all are excluded by designs that don’t fit our ever-changing bodies. We’ll take a much closer look at this dynamic in chapter 7 as we challenge some outdated notions about what it means to be a normal human being.

Everyone gains and loses abilities over the course of their lifetime.

Consider how much of our world is visual. Large amounts of information are conveyed through computer screens, street signs, and various uses of light. An icon isn’t just an icon. It’s a way to communicate information. All people, regardless of their degree of eyesight, want to be able to access these kinds of information, whether in reading a lunch menu or sharing a quirky selfie with your best friend.

Touchscreens are making their way into many environments, often replacing human beings with an automated system. They are often the key to buying groceries, navigating transit stations, pumping gasoline into a car, and even completing classroom assignments. But touchscreens can make these spaces inaccessible to people who are unable to see or touch the screen.

These kinds of exclusion impact many people with varying degrees of sightedness. There are people who are born blind. People with one of many kinds of color blindness, or partial vision. There are people with light sensitivity, farsightedness, nearsightedness. Given a long enough life span, everyone loses some degree of their eyesight.

As our bodies change, we encounter more mismatched designs, simply because the designs that once worked well for us don’t change with us. There are two key side effects that stem from being subjected to high degrees of exclusion: societal invisibility and the pain of rejection. Let’s take a closer look at each one.

Invisible by Omission

Exclusion isn’t evenly spread across social groups. Although we all experience it in our lives, some communities of people are ostracized in more ways and over longer periods of time.

A designer recently confessed to me that they would like to learn more about disability, but that the diversity topic that they cared most about was gender. Why would they feel the need to choose one and omit the other?

This is another kind of mismatch. How we categorize people often doesn’t reflect how they really are: multifaceted. When we design, which facets of human beings are most relevant to our solutions? We’ll explore this question in chapter 4.

Grouping people based on oversimplified categories like “female” or “disabled” or “elderly” can seem like a helpful shorthand when making business or design decisions. But there’s one big problem:

Some categories of people are always last on the list of priorities, or wholly forgotten.

As Paley noticed with her students, the same few children were rejected year after year. They were “made to feel like strangers.”2 This phenomenon can happen to entire categories of people.

Disability is one such category. Exclusion has a profound impact on disability communities, and the consequences are rarely given the attention they deserve. The societal omission of disability runs deep. So deep that entire populations of people are virtually invisible in society.

For example, disability rights and history are rarely incorporated in school curricula. Accessibility is scarcely a required course for engineers and designers. Formative disability rights leaders and the movements they champion are seldom mentioned alongside other civil rights leaders. These omissions can further reinforce stereotypes and isolate people with disabilities from society.

Yet the influence of these leaders permeates the design of our world. Curb cuts are the quintessential example. A curb cut is the sloped transition from a sidewalk to a street that makes the crossing accessible to people who use wheelchairs.

Between 1970 and 1974 Telegraph Avenue in Berkeley became an extensively accessible route for wheelchairs, making it one of the first streets in the United States to do so. It was one culmination of changes sparked by Ed Roberts and leaders of the Independent Living Movement, in their fight for disability rights on the University of California campus. The design was evolved and refined over time to include adjustments for people who are blind, who had relied on the shape of the curb as a way to avoid accidentally walking into street traffic. Different textures were used to indicate the transition into a street, as many corners continue to do today. Curb cuts are also widely used by anyone who’s pushing a baby stroller, towing a suitcase, or riding a bike.

Another example of societal invisibility is the low labor participation rates for people with disabilities. Just 35.2% of people with disabilities in the United States were employed in 2015.3 This is compared to a 62% labor participation rate for people without disabilities in the same year.4 Multiple sources have different statistics, but they all point to the same general truth.

There are many other significant gaps in equality for people with disabilities. Design, alone, isn’t going to close all of these gaps. Yet designers, engineers, and business leaders can make progress toward equality with every design decision they make. And it starts with building a baseline understanding of the accessibility policies that impact their work.5

These examples reflect how exclusion impacts people with disabilities. Similar examples can be found for communities that are excluded based on ethnicity, gender, economic status, and more.

For designers, one important way to change invisibility is to seek out the perspectives of people who are, or risk being, the most excluded by a solution. Often, the people who carry the greatest burden of exclusion also have the greatest insight into how to shift design toward inclusion.

Heartbreaking Design

If we could prove that exclusion causes physical pain, what would we change about the design of our classrooms? Our workplaces? Our technologies?

We have rules in schools and society against physically harming each other, but for some people being left out is treated as a fact of life. It’s just part of the way the game was designed. It’s fairly common for people to treat social rejection as a necessary part of learning to survive in the world of humans.

Yet multiple studies show that social rejection might manifest in our bodies in ways that approximate physical pain.

This is exactly what Ruth Thomas-Suh reveals in her film Reject. She features a community of researchers and academics working to understand the links between exclusion and pain.6 They all point to a similar insight: rejection hurts.

More specifically, they found that the regions of the brain that “regulate the distress of social exclusion” were similar to the regions that regulate physical pain.7 In other words, being socially rejected might directly affect our physical well-being.

This rejection has many consequences: anxiety, insecurity, anger, hostility, feelings of inadequacy, a sense of being out of control. Even the words that people use to describe social exclusion approximate physical pain. Hurt feelings. A broken heart.

What if an object rejects us? Is it as painful as being rejected by a person?

Dr. Kipling Williams was relaxing at a park one afternoon when a wayward frisbee landed in his lap. He stood up and tossed it back to two people who were playing frisbee. They started throwing the frisbee to Williams, including him in their game.

Suddenly, without a word, they stopped. They continued to play with each other, but Williams was no longer included. The experience stuck with him, with its feeling of dejection.

He quickly realized that he could recreate this experience in his laboratory at Purdue University to study the effects of exclusion. He made a simple computer simulation, called Cyberball, in which two characters on a screen tossed a virtual ball to the research participant, who was led to believe that the two other players were real people in another room. Then, suddenly, the two characters stopped tossing the ball to the research participant, effectively excluding them for the rest of the game.

People who participated in Williams’s Cyberball studies typically reported a degree of sadness and anger that often accompanies rejection. This was expected.

What surprised Williams was that their anger increased once they learned that the two other players were controlled by a computer, not by real people. One person aptly described their reaction as, “You know that people will let you down, but computers aren’t supposed to.”

We expect people to be unfair. People are fallible and prone to faults. Yet we expect technology to be impartial. Maybe it doesn’t always work the way it’s supposed to, but we tend to believe that inanimate objects are largely unbiased.

That is, until we’re locked out of accessing a building, product, or event that most people can access without difficulty. When the cycle of exclusion is in effect, the resulting designs are far from fair.

Not all exclusive designs are negative. They simply reflect a series of choices made by people who have the power to set the rules of a given design. Clothing made to fit certain body shapes. Special-edition products created to generate interest in a new business. An invitation-only birthday for an inner circle of friends. Sometimes creating limited access can have positive benefits.

The problem comes when there’s a mismatch between the stated purpose of a design and the reality of who can use it.

When a solution is meant to serve any member of society and then doesn’t, the effects of exclusion can be negative. The experience can feel like rejection from society itself. Especially in the shared physical and digital spaces where we learn, work, share, heal, advocate, create, and communicate.

There is a risk that exclusion will become more prevalent as technology moves into every area of our lives, because interactions that were once human-to-human are now facilitated by machines. Every human interaction that includes technology gains a wild card: who will it reject and who will it accept?

Exclusion Habits

What leads to cycles of exclusion and why are they more prevalent than inclusion?

Every day, design teams make incorrect assumptions about people. They might presume that someone who’s blind doesn’t use a camera. Or that a person who’s deaf doesn’t use a music streaming service. Is it malicious intent? Not likely.

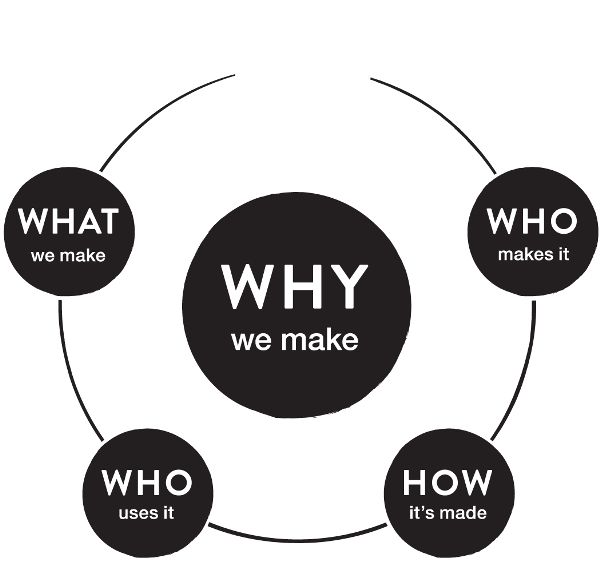

Let’s consider the first element of the cycle: Why we make.

As we set out to solve a problem, let’s imagine that most people have best intentions to create a beneficial solution. Their goal might be to solve a known issue for their existing customers. This is often in competition with other goals, like meeting a due date, looking good in front of someone in an authority position, or earning a reward for driving new business growth. In the crucible of competing goals, even the best intentions can get lost in the shuffle.

There can be little time to think. We might want to pursue our best intentions for inclusion, but there’s a constant pressure to keep growing and moving quickly. Like a carousel on fast forward. In these moments, assumptions become a necessary shorthand.

And then something much more powerful takes the lead: habit.

Paley refers to this as the habit of exclusion. Without an explicit understanding of how exclusion works, our default habits—habits we formed in our early childhood—can dominate, creating a cycle of exclusion.

An exclusion habit is the belief that whoever starts the game also sets the rules of the game. We think we don’t have power to change a game, so we abdicate our accountability. We keep repeating the same behaviors, over and over.

In short and simple games, it might be easy to call on the one who’s responsible for changing the rules to make it more inclusive. Over time, games get more complex, leaders change, and we can forget who authored the original rules. In some organizations, the cultural behaviors were set a long time ago and the founders of that culture are long gone. Or we believe it’s someone else’s job to rewrite the rules, maybe the leaders in our business or community.

We also forget that those rules were initially written by human beings and can be rewritten. Those of us who are now playing the game have a responsibility to adapt it as needed. If we don’t, we are accountable when someone’s left out—not some leader from the distant past. We can respect the intent of the game, but also adapt the rules to make it more inclusive.

Exclusion habits are the reason why we make mismatched designs. They stem from deep-seated assumptions about the people who receive our designs.

An architect might create a building with a grand staircase leading to its front entrance on the basis of tradition or aesthetics. Meanwhile, people who use wheelchairs might be searching for back-alley entrances and convoluted hallways to access the building.

When making choices in the design of a solution, we might think “those are just the rules, I didn’t make them up.” It’s easy to defer responsibility by claiming this is just how the world worked when we arrived.

This is why it’s important to distinguish why we make solutions, especially when we work on behalf of companies and organizations. While anyone can start to shift their personal reasons for creating solutions, inclusion often needs to be made part of an organization’s culture by people in the most senior leadership roles. If inclusion isn’t explicitly part of that leadership, exclusion will be the default.

Building New Habits

Exclusion habits can be hard to break. But, like any habit, they can be changed over time with new practices to challenge our mindsets and behaviors. When we say that we’re committed to inclusion, it’s like declaring that we’ll learn a new language. We start the next day full of enthusiasm and optimism, but become quickly aware of our huge gap in expertise.

Learning a new language can take planning, training, and determination. But above all, it means engaging with people who are native in the new language you want to learn.

To gain fluency, you will need to change aspects of your routine and adjust some the elements of your life to support your new goal. You might even relocate to a community where your new language is spoken every day. The same is true for building skills for inclusion.

These skills can be learned from people who interact with unwelcoming designs every day of their lives. They often have an intimate understanding of all the angles to consider. These are the designers, engineers, and leaders who have the greatest power to disrupt the cycle of exclusion.

Learning from these experts, we will identify the top exclusion habits for each element of the cycle. And we will highlight ways to shift the cycle toward inclusive design.

■ ■ ■

Takeaways: Why It’s Time to Kick the Habit

- ■ Mismatched designs contribute to the societal invisibility of certain groups, like people with disabilities.

- ■ When a designed object rejects a person, it can feel like social rejection and approximate physical pain.

- ■ Exclusion habits stem from a belief that we can’t change aspects of society that were originally set into motion by someone other than ourselves.