This chapter will look at some of the production techniques associated with radio drama; these would also apply if you were making a radio advertisement. While writing and researching a radio play is very different to writing and researching a radio advertisement, the production process is similar. Whichever you are planning for your project you should read the whole of the chapter to understand the techniques you are going to need to use.

A phrase often quoted by radio producers is attributed to a small boy who supposedly said, ‘I like radio – the pictures are better’. Nowhere is this more true than in radio drama. Radio creates pictures in the imagination and because the listeners create their own image it’s a deeply personal and powerful experience.

If you ask anyone who listens frequently to the long-running radio soap The Archers they will probably be able to describe to you what each of the characters looks like, they will have a mental picture of the village and they will probably know exactly what the inside of the local pub looks like. They will be able to do this without having ever seen a single image. Indeed, those images can be so powerful that listeners often don’t like it much when they do see a picture of the real actor: they’ll often complain, No, that doesn’t look a bit like Tom Archer. They have a mental picture of the character and want to stick with it. This tale of country life may not be to your taste but talk to someone who is a fan and you will start to understand how drama on radio can work directly with the imagination.

Since radio creates pictures in the mind, there is no limit to the pictures which can be created. TV and film drama are hugely expensive. Locations, sets, costumes, all cost vast amounts. So except for the very fortunate, writers in TV drama are rather constrained as to type and number of locations. Not so on radio. The writer is free to set the piece anywhere they want to. The sets are created by the skill of the writer and the production team in conjunction with the active participation of the listener. One of the most famous radio comedies A Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy has gone through many different iterations since. It’s been a book, TV series and feature film, computer game, even a stage show. The initial success of radio was that it skilfully created a humorous sci-fiadventure. It created a fantasy world in the mind of the listener and the locations literally went from one end of the galaxy to the other.

Radio is a writer’s medium. There is very little between the writer and the audience. If you like words then this is your medium.

If you are thinking of recording some radio drama but haven’t listened to much of it, log onto the website where you’ll find a link to a number of recordings.

Just as with anything else there are several tasks which you should allocate to members of the group when you do your drama.

As with the other types of recordings you may not have a different person responsible for each task; one person may have to take on several tasks, but you will need to know what the tasks are and who is going to do them.

It’s quite possible that you won’t have access to a studio. This shouldn’t necessarily stop you from thinking about making a radio drama piece. It is quite possible to do the recording without a studio, although there are other things you will need to be thinking about, in particular the acoustics. However, you will also need to make sure that you have the equipment to record the drama itself, so you will need the microphones and some sort of mixer.

However, you may be lucky enough to have access to some sort of studio. A radio studio can comprise one room or two. If it has one room, all the recording equipment will be in the one place along with the microphone. They tend to be used for simple recordings. For the most part radio studios will have two rooms. One is called the cubicle. The cubicle has all the recording equipment, speakers and the mixing desk and computers If it’s a digital studio the computer software will control the recording, playbacks and all the editing. The other section is the studio; it will have a microphone, possibly a table and chairs and stands for the script. Radio drama is usually conducted in this kind of studio.

An earlier chapter looked at the different kinds of microphones which you might be using. You will need to know what kind of microphones you have. Are they omnidirectional or directional, for example? This is because you will need to position the actors in front of the microphone to get the best sound and you will need to know how the microphone is picking up the sound. Generally a directional microphone is likely to be more useful, particularly if you don’t have a studio to record in. However the clip-on microphones can also be helpful.

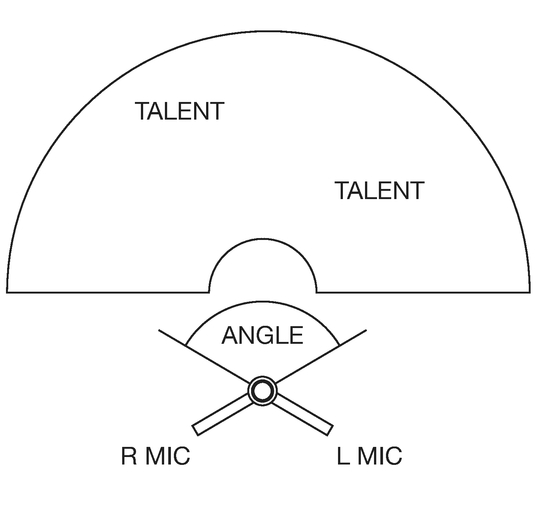

Radio drama is often recorded in stereo. The idea of stereo in the context of music is quite familiar. In radio drama, using stereo can help create a sense of space. When the listener is creating a mental image of what is happening in the play, the stereo effect will put the characters on the left or right of the sound stage. This will help the listener create a mental image of what is going on. You don’t’ necessarily need a stereo microphone to get a stereo picture. You can use two mono microphones. These are called a coincident pair and they are usually set up so that they cross over one another (Figure 19.1).

You are actually recording two mono tracks. However, the recording engineer can move the sound around the stereo image and put the voice to the left or right. Stereo obviously opens up a wealth of possibilities to radio drama, but it demands careful monitoring. You need to make sure you have a clear mental picture of the scene and that everyone stays in the correct position. The listener will get very confused if a character starts to jump all over the stereo picture; it will have the effect of making it seem as if they are jumping about in the room.

Figure 19.1 A coincident pair

You will need to ensure that everyone has a copy of the script. When you lay out the script there are a number of points to remember. An earlier chapter gave you examples of a script layout.

You can also log onto the website and follow the link to see more examples.

In radio drama you are trying to use sound to create an image in the listener’s mind. Something which just sounds as if it’s being read on the radio isn’t really a drama. The sound image you create is every bit as important as the actual dialogue. It is the sound image that will create a sense of mood and place in the listener’s mind. There are a number of different elements which go into creating a sound image.

One way of creating a sense of place in a radio drama is to alter the acoustic. In radio drama the acoustic refers to the amount of reverberation (echo) you can hear on the recording. In order to get a sense of acoustic you will need to start listening to how voices sound in different locations.

In an actual location the amount of reverberation depends on the extent to which the sound-waves coming from your voice are reflected back. Sound-waves tend to reflect back if they hit something hard. If they hit something soft they get absorbed or if they don’t hit anything at all they just fade away.

You can easily get a sense of this if you use a portable recorder to make some recordings in different locations.

Understanding the acoustic of the space in which you have set the script is important, as it forms the basis of the sound world you are trying to create.

If you are using a studio space then most of the time it will have a fairly neutral acoustic. It won’t have that reverb where it sounds as if you are in a church; nor will it sound as if you are recording in an open space. A professional drama studio will often have different acoustic areas in the same studio. There will be a dead area, usually created by erecting screens or walls made of material which absorbs sounds and laying carpet on the floor. There may also be a live area where there is a wooden floor and harder surfaces. You are unlikely to have this luxury; however, you can still play with the acoustic.

If you don’t have a studio and are recording on location you could try to find an acoustic which matches your script. You could try recording outside if the script sets a scene outside. The difficulty of this is that you are at the mercy of everything else going on around you. Dogs barking, cars passing, aeroplanes will all start to become a nuisance. As discussed in Chapter 13, a continuous sound is less problematic than an intermittent sound, but you will need to think about your editing.

Recording inside is more controllable, and it’s probably easier to find a quiet space. However, it’s worth thinking about the natural acoustic of the room. If you are in a big room with lots of windows and hard surfaces, it will be very difficult to create a convincing exterior acoustic. You would need to construct some kind of dead area with blankets, duvets, etc., and your cast may start to find it a bit comical acting inside some kind of cosy tent you’ve constructed.

Getting the acoustics right takes quite a lot of practice and a good ear. If you want to play with the acoustic then it’s probably best to practise before you have all your cast assembled. You will need to keep trying out different things to hear the different acoustics which you can create and it will take a bit of practice before your ear gets properly tuned in.

There are two types of sound effects. The first is the type you might find in a library. There are all sorts of online Sound FX libraries where you can get a very good selection.

If you log onto the website you will find links to some libraries.

The first thing you need to think about is the atmos (atmosphere); this might also be referred to as ambience. The earlier chapter on sound discussed the idea of recording wild track. This was to get some of the atmosphere of a room. Even if a room sounds quiet there is likely to be some kind of atmospheric noise. If you want to create a convincing soundscape for your drama you will need to choose some kind of background atmos.

The ambience or atmos is generally the first thing you want the listener to hear. In radio you want to create a sense of place in the mind of the listener. Remember: your listener is actively working with you to create this picture. Give them a lead and they will start to create their own mental picture.

It may be that there are a number of specific sounds which you will need to hear at a particular time in the script. This might range from phones ringing, the sound of the TV in the background, dogs barking and cars passing. Again you can find a large range of these sounds from any of the online sites.

When you use this kind of effect you will need to think carefully about where you place them in the sound picture. If, for example, you want the sound of a dog barking in the distance, you will need to make sure that it sounds distant and muffled; otherwise it will sound as if members of your cast are about to be ravaged by a vicious animal.

Some of these sounds can add to your atmos: bells ringing, birds tweeting can add to a sense of being in the countryside. Car horns and so on can add to an urban feel. Others may be specific sounds that are needed and specified in the script.

People differ as to when they add the effects. Some directors like to add them in as they are recording the script. They feel that the actors give a better performance if they know what is happening around them. Other directors like to add them in the edit, as this means they have more control. It can be more difficult to edit a piece if there are a lot of sound effects added during the recording.

Spot effects are the types of effects which you will add yourself, usually as you are recording. They are the type of effect that is difficult to create from a recording. If, for example, you have a scene set around a dinner table during a meal, you would expect to hear the sounds of knives and forks clinking on plates. You can get your cast to create these sounds or you can have someone beside them doing it. Sometimes the cast find it difficult to hold the script and create the sound. The spot effects are the equivalent of a Foley artist in film or TV drama. In TV and film it’s usually only quite big productions that will use a Foley artist and the effects are added in post-production. In radio you can have fun with spot effects, experimenting with different ways of re-creating a sound.

There are so many ways to create spot effects that it’s too long to list them here, but if you click onto the sites listed on the website you can find out more.

Depending on how complicated the sound is, some spot effects are recorded along with the dialogue and others might be laid later. Recording at the same time gets the timings better and for simple effects like clinking of glasses this is probably the way to go.

Music can be an important component in a radio drama. It is most frequently used to introduce a scene or to segue between one scene and the next. It is sometimes used during a scene but you should be very careful about this as it can quickly become quite irritating. It’s probably a good idea in a short piece to avoid too many different bits of music as you piece will quickly sound slightly disjointed. Using one piece of music as the theme will probably work better. Music can help create:

There are plenty of mood music libraries you can use so that you can easily search and use the type of music suitable for your production. You should remember however that it is very difficult to make a good music edit. For this reason people usually add the music after they have recorded the speech. That way if there is any editing to be done it can be done without having to edit any music.

Silence can be a powerful effect on radio. You shouldn’t be afraid of using silence if the script calls for it. However, it is obvious that you can’t let that silence run for too long or the listener is going to think something has gone wrong with the radio.

As well as using sound FX and acoustic to create the sound image, you will also need to use some microphone techniques. In order to do this you will need to figure out what kind of microphones you have. If you refer back to the previous chapter on sound you will know how to check this. In radio drama it’s more useful to have a directional microphone than an omni microphone if you only have one choice.

You will need to offer your cast a chance to read through the script together. You can do this in a reading, away from the studio, just so that everyone is familiar with the script and can raise issues if they wish. However, you will need to remember that rehearsals really only start when you can hear what it sounds like through the speakers. Don’t spend too long rehearsing away from the microphone, as it will sound different. If you do a rehearsal away from the microphones it’s better to use this as a chance for everyone to discuss the characters or discuss any issues. You may give the cast some kinds of character profiles, a bit of background and you may also want to discuss the relationships their characters have with each other. However, this is not quite the time to discuss the specifics of a performance; this is better done when you are actually hearing it in the studio or on location.

Once you are on the microphone you will have a much better idea of what a performance is going to sound like. Directing a cast is tricky, particularly since both you and the cast are likely to be inexperienced.

A few tips for directing a cast:

Most drama directors tend to rehearse and then record sections of the script at a time. This allows them to rehearse not just the lines but any sound effects. As the director you need to be thinking about:

As the director, you will also need to make sure that everyone knows what they are supposed to be doing.

Just as you do when you are taking a shot for film there is a kind of sequence of commands that you go through to make sure that everyone knows what is happening. So, for example, if you are happy that everyone knows what they are doing you say something like:

At this point you will need to decide whether you are happy with the take or whether you want to take all or some part of it again. If you want to run anything again you will need to be clear with everyone why you are running the piece again and tell them anything you would like to have done differently. It may be that there were some extraneous noises or some line wasn’t delivered quite correctly.

You may only want to record a few lines again. If you do this make sure you record more than you need both at the beginning and at the end, this will make your edit a lot easier. If you do want to record anything again you will need to repeat the sequence of commands.

Nobody sticks exactly to the script I’ve suggested but they will do something similar. By using this familiar sequence of commands everyone knows what is happening and becomes focused on their job. It saves a lot of wasted time.

Once you have recorded the material you will need to edit and mix it. You will need to choose the best takes of any particular scene, edit out any fluffs or bits that went wrong and then mix the scene with any music or sound effects.

The next thing you will need to do is to lay any of the music or sound FX.

Once you have mixed the piece and done all the final tweaks you will need to play out the material. The format you use will depend on what your particular project requires. However, remember: always keep a backup copy and don’t delete any of your rushes until you know for sure that you are not going to need them again.

Radio drama can be a highly creative and exciting art form, particularly if you like the spoken word. Technically it is less cumbersome than film or TV drama and that leaves you all the more time to make something which is much more creatively challenging and polished. There are no limits to the number of locations and characters you can create and no limits to the scope of your story. It’s a powerful medium.