Chapter 2

Organizing geriatric services

Acute services for older people

Complex day services/day hospitals

HOW TO . . . Do a domiciliary visit

HOW TO . . . Advise a patient about care home placement

Using geriatric services

Geriatric services are radically different from those developed around the inception of the specialty in the 1950s. Locally, services differ, dependent upon resources, organizational structures, and the drive and vision of local clinical leaders. There are some broader national differences within the UK, e.g. services in Scotland and Northern Ireland lean more towards rehabilitation and long-term care than those in England and Wales.

Services should be configured to deliver the best possible population benefit (patient-centred health and social care outcomes) and patient/carer experience, considering the sustainable financial and human resources. Careful attention must be given to vulnerable, difficult-to-access groups and to the optimal balance of centralized care (efficient, resilient, and leveraging high-capital elements such as computed tomography (CT)/magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scanners) versus distributed care closer to home (improved patient experience, greater holism, lower capital costs, and a default enabling approach).

The following is intended as a generic guide, as provision is highly variable.

Services for acute problems

Urgent assessment of the acutely unwell patient where the disease process is new, severe (e.g. acute MI, stroke, sepsis, delirium), and/or very rapidly progressive.

Service examples:

• 1° care (general practice (GP)) emergency assessment services (see  ‘Primary care’, p. 44)

‘Primary care’, p. 44)

• Locality (community)-based emergency multidisciplinary assessment service

• Rapid access (‘admission avoidance’) services (see  ‘Admission avoidance schemes’, pp. 20–21)

‘Admission avoidance schemes’, pp. 20–21)

• Acute medicine assessment service

• Urgent domiciliary visits (DVs) (see  ‘HOW TO . . . Do a domiciliary visit’, p. 31)

‘HOW TO . . . Do a domiciliary visit’, p. 31)

• Emergency departments (EDs; see  ‘Acute services for older people’, pp. 16–17)

‘Acute services for older people’, pp. 16–17)

Choosing which is most appropriate will depend on patient clinical characteristics (e.g. if critically unstable, then an ambulance to the ED may be appropriate; if no change is expected imminently, then urgent outpatient assessment may be used), patient preference, local service characteristics (acceptable case mix, hours/days of operation), and operational issues (availability of urgent clinic appointments, transport, etc.). There has been a strong trend towards provision of services ‘closer to home’—in 1° care or community health settings such as health centres and community hospitals (CHs), although the evidence of clinical and cost-effectiveness is not good.

Services for subacute problems

Assessment of a patient with a progressive disease process (e.g. ↑ falls, complex Parkinson’s disease), unexplained potentially serious problems (e.g. iron deficiency anaemia, weight loss), or a more refined diagnosis and management plan (e.g. cardiac failure).

Discrete (‘single organ’) problems can be assessed in more narrowly specialist clinics, less well-defined or ‘multi-morbid’ problems in a geriatric outpatients, and problems suggesting multidisciplinary need in the day hospital or by a domiciliary multidisciplinary team (MDT).

Local availability, waiting times, and consultant interests affect choice.

There is a strong national drive towards managing patients in an ambulatory (non-admitting) setting. Done well, this improves resource use, may reduce iatrogenic hospital-associated harm, and often improves patient experience.

Service examples:

• Geriatric medicine outpatient clinic

• Specialty clinic (see  ‘Specialty clinics’, p. 24)

‘Specialty clinics’, p. 24)

• Day hospital (see  ‘Day hospitals’, pp. 22–23)

‘Day hospitals’, pp. 22–23)

• Intermediate care (IC) facility (see  ‘Intermediate care’, pp. 26–27)

‘Intermediate care’, pp. 26–27)

• DV (see  ‘HOW TO . . . Do a domiciliary visit’, p. 31)

‘HOW TO . . . Do a domiciliary visit’, p. 31)

• Elective (planned) admission (to acute hospital, rehabilitation wards, or CH) is now much less commonly considered appropriate, as the environment may be disabling, iatrogenic harm is common, and resource use disproportionate

Services for chronic problems

This includes active elective management of slowly progressive conditions by 1° care teams (people aged over 75 in the UK should have a named general practitioner (GP)), community teams, specialist nurses, and 2° care physicians (see  ‘Chronic disease management’, pp. 42–43) and the provision of care for established need.

‘Chronic disease management’, pp. 42–43) and the provision of care for established need.

Long-term care may be provided in a number of ways:

• Informal carers (see  ‘Informal carers’, p. 38)

‘Informal carers’, p. 38)

• Home care and care agencies (see  ‘Home care’, pp. 36–37)

‘Home care’, pp. 36–37)

• Day centres (see  ‘Other services’, p. 40)

‘Other services’, p. 40)

• Respite care (in care homes or hospitals) (see Box 2.1)

• Care homes (see  ‘Care homes’, pp. 32–33)

‘Care homes’, pp. 32–33)

Allocation of these (usually) long-term services is generally after an assessment of need and financial status by a care manager.

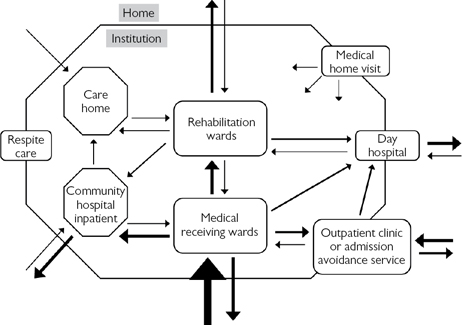

With time, most patients pass through many aspects of the spectrum of geriatric care; a flexible, responsive set of services with good communication between providers is essential (see Fig. 2.1).

Fig. 2.1 An example of possible patient flows within a complex system of care for older people.

Acute services for older people

Since older people present atypically and are at high risk of serious sequelae of illness, high-quality acute services that fully meet their needs are essential. In any setting, older people have special needs and the consequences of not meeting them are amplified in the setting of acute illness. Specific areas meriting attention include the prevention and treatment of delirium, falls, and pressure sores; optimization of nutrition and hydration; and provision of an enabling, individualized setting that maximizes independence and well-being. Accurate, early, and comprehensive diagnosis(es) is (are) essential, alongside careful determination of goals that are valued by the patient and that are realistic.

An acutely unwell older person may present to one of several services, depending on:

• The individual’s understanding of the system

• Advice from others (e.g. relatives, health professionals, NHS 111)

Any service aiming to diagnose acute illness in older people must have access to immediate plain radiography, electrocardiography (ECG), and ‘basic’ blood tests (including prompt results, often facilitated by ‘point of care’ testing technology delivering results in non-laboratory settings in minutes). Access to complementary specialist clinical input (e.g. geriatrician, urologist, neurologist, etc.) is essential, through a range of mechanisms including face-to-face assessment, telephone advice, or telemedicine. Cross-sectional imaging (ultrasound, CT, MRI) must be available promptly, although it may be on another site.

Emergency department (accident and emergency)

Common presentations include falls (with or without injury), ‘fits and faints’, and a broad range of acute surgical and medical problems traditionally referred directly by 1° care to specialist (non-ED) surgical or medical teams.

Direct presentation of such patients to the ED (rather than following initial assessment by 1° care teams known to the patient) has ↑, due to changes in 1° care services both in and out of hours, advice by agencies such as NHS 111, and changing public expectation and behaviour. Often the acute illness itself is not severe but occurs in the context of frailty, comorbidity, and social vulnerability, leading to reflex escalation of care and a brisk and direct channel to the ED.

The ED is potentially inhospitable and dangerous for older people. The environment may be cold, uncomfortable, disorientating, noisy, and lacking dignity and privacy. There is a risk of pressure sores, delirium, and avoidable immobility and falls. Provision and administration of food and fluid may be neglected or inappropriately prohibited on spurious medical grounds. A medical model of care may presume serious illness and restricted mobility (to allow invasive monitoring and treatments) can occur at the expense of a more holistic, individualized, and enabling approach. Staff are experts in emergency medical management, but their expertise in complexity, frailty, and holistic care is often less developed.

For those patients who do require urgent hospital assessment, there is ↑ focus on offering ambulance clinicians and 111 teams direct access to Acute Medicine, Geriatric Medicine, and other urgent care specialties; done well, this can deliver quicker, more effective care in a more age-appropriate environment. However, it is important that older patients who would benefit from ED capability—such as the critically unwell—are not excluded.

Deadlines and targets that minimize time spent in the ED (e.g. the 4-hour standard) generally benefit older ED users with limited physiological and functional reserve, for whom the best outcomes are often time-sensitive.

Strategies to optimize care for older people in the ED—that must be available for extended hours and 7 days a week—include:

• Close liaison with geriatric medical and nursing specialists

• Medical, nursing, and therapist rotation between ED and geriatric specialist settings

• Focus on optimizing food and fluid provision and pressure-relieving care

• Provision of alternative modes of admission and assessment, e.g. Rapid Access Clinic, direct admission to a geriatric ward

• Provision of specialist geriatric assessment units which may be embedded in or near the ED (‘Acute Frailty Units’)

• Occupational therapist (OT), physiotherapist (PT), and social worker with expertise in older people based in the ED

There are ↑ calls for the creation of discrete areas in the ED with an environment and clinical capability tailored to the needs of frail, complex patients. This development—akin to that of the ‘Children’s ED’—is hampered by constraints on human and capital resources and physical space; in practice, immediate pragmatic assessment and ‘streaming’ to more appropriate settings is a more sustainable and deliverable approach, particularly in smaller departments.

Further reading

British Geriatrics Society. Quality care for older people with urgent and emergency care needs: ‘Silver Book’.  http://www.bgs.org.uk/campaigns/silverb/silver_book_complete.pdf.

http://www.bgs.org.uk/campaigns/silverb/silver_book_complete.pdf.

The integration debate

There is a long-standing debate among UK geriatricians about the best model of care for older people in hospital. Historically, age-related care grew out of poor-quality workhouse facilities, and the advent of specialist care provided from mainstream hospital settings with equitable access to services was a major progressive step. Traditionally, care has been divided into either:

• Age-related. A separate team of admitting doctors to deal with all patients over a certain age (varies—commonly around 75 years) who then care for these patients on designated geriatric wards

• Integrated. In truly integrated care, specialists maintain additional generalist skills. These generalists admit all adult medical patients, regardless of age, and continue looking after them on ‘general medical’ wards, in parallel with specialist clinical commitments (see Table 2.1)

The debate has not been fuelled by high-quality evidence and has become less febrile as constraints—not least reduction in junior doctors’ working hours—have made it less practical to run two entirely separate acute teams. As a result, a range of blended or ‘hybrid’ systems have been developed, managing patients pragmatically and delivering the best compromise of robust 24–7 generic acute services with selective, complementary specialist in-reach.

A common compromise is that there is integrated acute assessment, with a single admitting team, but rapid dispersal to the most appropriate service. This dispersal occurs at varying points in the patient pathway, depending on local service strengths and constraints. Models include triage of need (‘function’-related segregation) by an appropriate person immediately after admission (admitting specialty registrar or consultant, experienced nurse, bed manager, etc.) and dispersal by a ward allocation system after removal from the admitting ward, or over a period of a few days (by inter-specialty referral) as special needs become apparent.

As individual systems evolve, the debate recedes and energies are invested into providing the best possible care for all patients through innovation and flexibility within a certain hospital structure, rather than in drawing boundaries and maintaining rigid definitions. Relentlessly, ↑ median age and the complexity of the inpatient population in most specialties are driving the development of systems that put in place a geriatric capability in all relevant settings, ideally integrated with that of the local ‘organ or condition specialist’ team (e.g. Oncology, Surgery, Neurology). Vigilance against ageism in these evolving systems remains essential.

Table 2.1 Comparison of age-related and integrated care

| Age-related care | |

| Advantages | Potential drawbacks |

| All old people seen by doctors with a special interest in their care | Possibility of a two-tier standard of medical care developing, with patients in geriatric medicine settings having lower priority and access to acute investigation and management facilities |

| All old people looked after on wards where there is an MDT | Less specialist knowledge in those doctors providing day-to-day care |

| Even apparently straightforward problems in older patients are likely to have social ramifications that are proactively managed | May be stigmatizing for all patients of a certain age to be defined as ‘geriatric’ |

| May be less kudos and respect for geriatric medicine practitioners | |

| Integrated care | |

| Advantages | Potential drawbacks |

| As the majority of patients coming to the hospital are elderly, it maintains an appropriate skill base and joint responsibility for their care | Many generalists will not be skilled in the management of older patients, so those under their care may not fare as well |

| There is equal access to all acute investigative and maintenance facilities, as older patients are not labelled as a separate group | Specialist commitments are likely to take priority over the care of older patients |

| Trainees from all medical specialties will have exposure to, and training in, geriatric medicine assessment | The MDT input is harder to coordinate effectively where the patients are widely dispersed |

| Sharing of specialist knowledge is more collaborative and informal | Management of the social consequences of disease tends to be reactive (to crisis), rather than proactive |

Admission avoidance schemes

Admission avoidance schemes (AAS) are variable in content and name. Schemes may be divided into those that do and those that do not offer specialist geriatric assessment (provided by a geriatrician, a GP with a special interest (GPSI), or a geriatric specialist nurse).

Non-medically supported schemes

These may include emergency provision of carers, district nurse, OT, and PT, delivering prompt functional assessment and ↑ care after a fall, acute illness perceived as minor, or carer illness. As specialist medical assessment is not a part of the scheme, treatable illness may be missed. As a minimum, such schemes should incorporate assessments by capable healthcare professionals who can recognize the need for specialist geriatric assessment and can access such services promptly.

Schemes with a medical assessment

• Variously titled Early Assessment, Rapid Assessment, Emergency or Rapid Access clinics

• All aim to provide a prompt response to medical needs in older people, with acuity falling somewhere between immediate admission and more elective outpatient services

• Some schemes provide same-day assessment; most assess within a day or at most a fortnight (the equivalent of cancer ‘2-week wait’)

• There is an assumption that patients are midway between first symptoms and more severe disease, and that early intervention may prevent decline, permit less aggressive or invasive treatment, and reduce health service resource use (not least inpatient care)

• Services are best accessed via telephoned, faxed, or electronic referral, with prompt ‘triage’ by an experienced professional

There is a risk that acutely unwell older people who need emergency assessment or treatment are referred to AAS, rather than admitted immediately. If in doubt, arrange immediate assessment by the emergency medical/geriatric medicine team. Delirium is an example of a presentation where admission to hospital from home should be considered carefully, balancing the risks and benefits of both settings; neither setting is risk-free.

• In practice, most schemes admit a modest proportion of patients to hospital following assessment. In some cases, this two-stage pathway represents optimal care, but there is a risk of clinical harm if delay is material

• AAS staffing usually includes senior medical staff (± junior support). Experienced nursing assistance is invaluable; roles are variable but may be very advanced, to include history taking, physical and mental state examination, and prescribing

• Most commonly, AAS are housed in ‘general’ outpatient facilities. Examples of problems managed here include anaemia or breathlessness

• A more comprehensive geriatric response (see  ‘Comprehensive geriatric assessment’, p. 68) is facilitated when the AAS is housed in, or adjacent to, outpatient multidisciplinary services, e.g. day hospital (DH)

‘Comprehensive geriatric assessment’, p. 68) is facilitated when the AAS is housed in, or adjacent to, outpatient multidisciplinary services, e.g. day hospital (DH)

• AAS should have prompt (ideally same-day) access to OT and PT services, to support the patient at home while the effect of medical interventions become apparent. Patients with complex needs are best managed in this environment, e.g. Parkinson’s disease with on/off periods

Increasingly, driven by financial penalties, there is a focus on readmission avoidance. Services provide rapid access to specialist assessment and treatment in an ambulatory (non-admission) setting, following recent discharge.

Complex day services/day hospitals

DHs provide a health intervention and a patient experience quite distinct from that of outpatient or inpatient care. Typically, patients receive an extended intervention (for a half or full day), during which there is a multifactorial, multidisciplinary assessment and/or treatment.

DHs usually provide a mixture of new patient assessment, rehabilitation, and chronic disease management. Patients may be referred directly from the community, from other hospital outpatient services, or following an inpatient stay. Some units designate sessions for specific patient groups (e.g. movement disorder, admission avoidance).

The case mix and interventions vary widely between units but can include:

• Medical—new patient assessment, e.g. for falls, frailty, immobility, multi-morbidity

• Nursing, e.g. pressure sore, leg ulcer, or continence assessment and treatment

• Physiotherapy and/or occupational therapy, e.g. following stroke, fracture, surgery, or non-specific functional decline

• Diagnostics—facilities for blood tests (including point-of-care testing), urinalysis, ECG, radiology, ‘tilt-testing’

• ‘Drug’ treatments, e.g. blood product transfusion, intravenous (iv) furosemide, iron infusion, levodopa monitoring

A flexible, tailored, holistic approach is usual. Many DH clients benefit from several elements in a ‘one-stop-shop’ approach.

Multidisciplinary teamwork, comprehensive geriatric assessment (see  ‘Comprehensive geriatric assessment’, p. 68), and functional goal-setting are important tools.

‘Comprehensive geriatric assessment’, p. 68), and functional goal-setting are important tools.

History and evolution

The first DHs began in the 1960s. With time, many units attracted a large number of long-term patients who were very frail but had little or no active health needs—the benefits were largely social (respite for carers and social interaction for patients). Unacceptably long waiting lists hindered efficient running in some units. Transport arrangements were often weak, with patients spending lengthy periods of time waiting for, or during, transport.

This monitoring and supportive role has now been largely taken over by day centres (see  ‘Other services’, p. 40). Contemporary DHs have a much higher ratio of ‘new to follow-up’ patients and rapid patient turnover, and are supportive of the urgent care pathway, including acute admitting functions and the ED.

‘Other services’, p. 40). Contemporary DHs have a much higher ratio of ‘new to follow-up’ patients and rapid patient turnover, and are supportive of the urgent care pathway, including acute admitting functions and the ED.

Strong drivers to ambulatory care have led to the introduction and expansion of ‘rapid access’ (‘admission avoidance’) clinics and early supported discharge schemes. These teams, vertically integrated across the hospital and home, often have a base in, or adjacent to, the DH.

Cost-effectiveness

A number of studies have examined clinical and cost-effectiveness. While this area remains controversial, systematic reviews have shown that a multidisciplinary DH intervention results in less functional deterioration, institutionalization, and hospital admission than control groups receiving no care. However, DHs did not generally prove superior to other comprehensive care approaches such as domiciliary rehabilitation.

DH care is costly, but this is offset by ↓ inpatient bed usage, institutionalization, and home care costs. Insightful clinical leadership with careful ‘prescription’ of DH intervention is essential in ensuring that the DH team delivers the greatest possible population benefit.

Specialty clinics

Every region configures resources in different ways, reflecting the local context. All have a portfolio of specialist clinics, supporting the care of patients with a range (narrow or broad) of symptoms or conditions (e.g. Parkinson’s disease, falls/syncope, chest pain). Pathways and resources should be configured in a way that optimizes available resources to deliver the best outcomes, including patient experience, with consideration of the need to provide a responsive (sometimes 7-day) service.

The portfolio of clinics for older people may be delivered by geriatricians, by other specialists, or sometimes jointly. Advantages of specialty clinics include:

• Optimized referral protocol and access

• Improved training quality for juniors

• Specialist nursing and therapy staff

• ↑ patient education and awareness of the condition—through meeting others with the same diagnosis, the work of specialist nurses, and the availability of dedicated information

• Supporting parallel scheduling of relevant diagnostic investigations (e.g. carotid Doppler ultrasound or magnetic resonance angiogram in transient ischaemic attack (TIA) clinics)

• Supporting improved quality through use of agreed care pathways and protocols

Where the same clinic is offered by differing specialties, or where you are unsure if referral to a geriatrician or an ‘organ specialist’ is the most appropriate, ask the following:

• Is this a new or urgent problem? An ↑ number of clinics have a protocol-defined maximum wait for urgent assessment. This may support admission avoidance and effective outpatient management of many conditions (e.g. TIA, chest pain, possible malignancy) but are prone to being overwhelmed with referrals, thereby rendering them less responsive to the needs of truly urgent cases. Non-urgent cases should be referred to routine clinics

• How well defined is the diagnosis? A patient with ‘cardiac-sounding’ chest pain without extensive comorbidity is likely to benefit from a specialist cardiology-delivered service, giving rapid access to the appropriate expertise and investigations. If the source of the pain is less clear, then the patient may be more effectively managed in a generalist clinic (general or geriatric medicine) where multiple options can be considered and explored in parallel

• Does the patient have a single dominant problem? If so, then they are likely to benefit from a focused clinic delivered by a narrowly specialist team. If, however, co-morbidities and/or frailty are prominent, then a geriatric clinic is likely to deliver a more comprehensive, holistic, patient-centred assessment and care plan

• Is this patient already attending a geriatric clinic for follow-up? If so, most new problems can be addressed by that team, rather than referring to another specialty

Intermediate care

IC is a generic term referring to a spectrum of services lying between acute hospital inpatient care and ‘usual’ (unenhanced) 1° care, aiming ‘to promote faster recovery from illness, prevent unnecessary acute hospital admission and premature admission to long-term residential care, support timely discharge from hospital, and maximize independent living’.

The term came into widespread use in 2001 as a key element of the UK National Service Framework for older people. Generally, these services were designed to deliver a time-limited, enabling intervention outside hospital. Many were refashioned from existing services and re-branded, but some approaches have been genuinely progressive and innovative and have a strengthening evidence base.

Many geriatricians welcome the emphasis on non-hospital-based care for older people, but others have warned against IC as a vehicle for covert ageist care that allows rationing of acute hospital medicine, substituting less expensive, and perhaps less effective, care.

The emphasis is often not primarily medical, but multidisciplinary and holistic. There are two main bodies of patients:

• ‘Step-down’ (following admission) care. Following acute admission or planned intervention such as major surgery. For those requiring rehabilitation, reablement, and/or reassessment of care needs in a non-acute setting

• ‘Step-up’ (admission avoidance) care. For patients at home who require enhanced assessment and treatment following functional deterioration or acute illness. The aim is to minimize functional decline and/or to avoid a hospital stay

Provision has developed locally; models of staffing, facilities, ethos, and access are heterogeneous. Some services concentrate on very specific groups (e.g. ‘post-surgical hip fracture in older people’); others are more generic. Most regions have a set of complementary services organized according to geographic and/or clinical rationales.

IC occurs in a range of environments, e.g.:

• The patient’s own home (the most common arrangement)

• Care homes, usually ‘care homes with nursing’

• Other community facilities, e.g. day centre

Interventions are often based around a comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) (see  ‘Comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA)’, p. 68) by an MDT, including appropriate medical support. More focused services may lack important team members (e.g. medical, social work); in those services, care is needed that important interventions (such as treatable illness or unclaimed benefits) are not overlooked.

‘Comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA)’, p. 68) by an MDT, including appropriate medical support. More focused services may lack important team members (e.g. medical, social work); in those services, care is needed that important interventions (such as treatable illness or unclaimed benefits) are not overlooked.

The variety of different models and quantum of provision results in inequity of access across territories. Research into the clinical and cost-effectiveness of IC is sparse and at times contradictory; the general conclusions are that there are sometimes cost benefits, compared to more traditional ‘hospital-centric’ approaches, but that these benefits are often marginal; some studies showed ↑ ‘whole system’ costs. Patient experience is more often a beneficiary. The UK National Audit of Intermediate Care continually identifies weaknesses in governance, the breadth of clinician support, and the quantum of provision at a population level.

Examples of popular approaches include:

• Crisis care. Rapid response to ‘social care failure’ in the home, often following unforeseen carer illness. Carers support the client at home, preventing ‘social admission’ to hospital

• Hospital-at-home. Intensive nursing, medical, and/or therapy input at home delivers effective treatment without hospital admission, or following hospital admission, to minimize length of stay

• ‘Rapid response’ or ‘supported discharge’ teams. Sometimes vertically integrated, providing inputs to hospital and home. The ‘front door’ intervention is across accident and emergency (A&E) and acute assessment areas, providing a rapid holistic assessment of needs to support immediate enabling home care (‘discharge to assess’); domiciliary teams pick up care promptly following hospital assessment or else respond to a patient with an urgent need at home (‘assess to determine need for admission’). These approaches contrast with the traditional ‘assess to (= before) discharge’ and ‘admit to assess’, which lead to unnecessary hospital care

• Reablement at home. A team of trained carers, acting under the supervision of a therapist team, deliver a prescribed enabling care package. Usually a time-limited intervention, with specified functional goals, aiming to reduce long-term social care needs and institutionalization

• Early supported discharge. A term most commonly applied to multidisciplinary rehabilitation following a stroke. Evidence for effect is good.

• ‘Care home plus’. 24–7 support in a care home, with additional clinician support from PT, OT, and the care manager. May have specialist medical input beyond that of the home’s ‘retained’ GP

In hospital, discharge coordination teams (often comprising nurses experienced in the care of older people and who understand complex care pathways) have an important role in bridging the gap between often complex and disintegrated hospital and community-based services.

Community hospitals

CHs vary substantially in size, clinical focus, and facilities. Some deliver a substantial contemporary clinical function that supports effective care of older people closer to home. Others have much more limited capability and may not meet contemporary patient needs.

Their origins were commonly as small ‘cottage’ hospitals, providing very limited services from buildings dating from the first half of the twentieth century. This century, some have undergone substantial change, with reinvention as decentralized foci of inpatient, outpatient, and increasingly day (diagnostic or therapeutic) care.

Often there is substantial community support, both emotional and tangible (volunteers, gifts, legacies). This makes service changes politically sensitive, slow, and difficult, if it is possible at all. In some cases, CH facilities are in desperate need of reconfiguration to reflect current patient needs. Emotive, unevidenced preservation of traditional arrangements risks patient care.

Facilities may include:

• Inpatient beds for between 10 and 60 patients

• PT, OT, and other therapy services (in- and outpatient)

• DH for urgent or planned intervention

• Office/professional base for community-based health and social care

• Outpatient facilities for medical and surgical clinics

• Psychogeriatric services; outpatient and/or inpatient

• Minor injuries unit—often staffed by nurse specialists

• Maternity services—midwife office base ± maternity beds

• Often a GP practice is based on site or close by, with mutual benefits

• GP out-of-hours service base

• Diagnostic testing, e.g. near-patient blood tests, plain radiography. More complex tests (e.g. CT, ultrasound, endoscopy) usually require transport to another hospital, although the most modern facilities may include them

• Local health (e.g. Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG) locality) management base

Medical cover. The traditional ‘cottage hospital’ approach was to admit patients on their own practice list and to visit reactively when called. More contemporary models employ dedicated specialist clinicians (GPSIs, geriatricians, or nurse consultants) to deliver proactive care. Visits should be both regular—identifying potential problems and planning prospectively—and highly responsive to acute problems identified by nursing staff.

Specialist geriatric medical input must be available when the need is identified. Other specialists, e.g. surgeons or neurologists, may hold outpatient clinics on site.

Nurses and therapists are often very experienced in the care of older people and are able and willing to work more independently from doctors. Nursing staff often lead the discharge planning process, including MDT meetings. Staff turnover is often low, with a high proportion of committed long-term staff.

Community hospital admissions

Groups of patients being admitted include the following.

Rehabilitation and discharge planning

Often transferred from acute hospitals following surgery (elective or emergency) or acute medical problems. Timing of transfer must be appropriate—is the patient medically stable? Have relevant investigations been completed? Are ceilings of care clear?

Palliative care

Where the nature of illness is clear, and cure is not possible, CHs can provide high-quality care and symptom control when things can no longer be managed effectively in the patient’s home. A CH setting is preferable to an acute hospital admission. Hospice beds are often limited and focus on those in whom symptom control is especially difficult.

Acute illness or functional decline

• ‘Step-up’ (acute) admissions to CHs must be considered carefully, based on local CH capability to offer effective diagnosis and treatment of what may be concealed or an atypical acute severe disease

• Admission to a CH is more likely to be justified in cases of strong informed patient preference, where the diagnosis is clearer, where invasive treatments and advanced monitoring are unlikely to be required, or when logistics dictate (e.g. very long distances). CHs with more advanced clinical capability can accept a more extensive ‘step-up’ case mix

• Admission may also be appropriate after specialist assessment in a rapid access clinic, DV, or frailty unit

• After accurate diagnosis and completion of invasive (e.g. iv) treatments, transfer to a CH becomes appropriate

‘Social’ admissions

Where staff perceive that the precipitant to admission has been a change in social supports (e.g. death or illness of a carer), not the condition of the patient. These patients are often very frail; high death rates in such admissions have been reported. Beware covert medical factors driving admission—seek and address them proactively.

Respite care

Usually now performed out of hospital, in care homes. Some especially complex or emergency/unplanned respite care may occur.

Effectiveness/cost-effectiveness

As with other forms of IC, there is little evidence that CHs provide improved outcomes or cheaper care than alternative systems. Much depends on local arrangements (scale, co-location, integration), governance and leadership arrangements, and the enthusiasm and innovation of local teams striving to deliver the best possible individualized care from available resources.

Domiciliary (home) visits

A medical assessment in the home, usually by an experienced geriatrician or, in some cases, a consultant nurse. This involves visiting the home of the ill person, sometimes alone, but perhaps with a GP, therapist, nurse, or care manager. Distinguish this ‘medical’ home visit from the home assessment visit performed by an OT to determine functional capacity and the needs for aids/adaptations.

Historically, DVs were widely used to prioritize patients on the waiting list for admission to hospital, but with the disappearance of such lists for acute medical problems, this is now rarely done.

There are advantages and disadvantages. The disadvantages—and an appreciation of how much elderly people benefit from selective use of modern acute hospital facilities—led to a substantial reduction in the number of visits performed. In many regions, their use atrophied to focus predominantly on those who refused to attend hospital and who appeared seriously or terminally ill.

The frequency of home visits is now ↑ again, as ‘care closer to home’ strategies intensify. DVs by geriatricians now often occur, whilst working within community-based MDTs supporting admission avoidance or early supported discharge.

Disadvantages

• Lack of equipment and other hospital facilities

• Lack of nursing support (chaperone, lifting/handling during clinical examination)

• A limited portfolio of tests, although the repertoire is ↑ (e.g. point-of-care haematology and biochemistry technology delivers results in minutes from a device the size of a desk phone)

• An inefficient use of time—as well as travelling time, patients and family often expect longer discussions and they effectively control the duration of the consultation

• Difficulty in coordinating synchronous multidisciplinary assessment, treatment, or discussion

Advantages

• Brings ‘care to the patient’ with generally better patient experience

• Function may be rapidly and effectively assessed, e.g. is there evidence of incontinence, is the larder stocked, is the dwelling acceptably clean, what degree of mobility is achieved (through, e.g. ‘furniture walking’), are there appropriate aids and adaptations?

• Assessment of mental state may be more accurate in the patient’s home

• Assessment of drug compliance (see  ‘HOW TO . . . Improve concordance’, p. 130)

‘HOW TO . . . Improve concordance’, p. 130)

• Patients appear more frail and vulnerable in a hospital setting and are usually less functionally capable in an unadapted, impersonal setting

• Some patients adamantly refuse hospital assessment. The experience of the visit itself may persuade a reluctant patient to be admitted

• Provides a second opinion for the community care team, which may be struggling to diagnose or treat, or needs reassurance that it is doing all that is possible

• Provides effective learning for predominantly ‘hospital-based’ clinicians about the imperfect correlation between function assessed in hospital versus the home

HOW TO . . . Do a domiciliary visit

When?

• Combine with other trips, if possible

• Not too early or late (patient may rise late and settle early)

Will you and your property be safe?

• Danger from patient, relatives/carers, neighbours?

• Tell someone where you are going and when you should be back

What do you need to know before you go?

• Name, address, directions (especially in rural areas), satnav

• Do you have a referral letter?

• Review and take any previous medical notes

• Can the patient’s family or carer attend? (One or two is useful—discourage excessive numbers of family members)

• Will the patient be in? Telephone in advance, including just before you set off

What to take?

• Blood pressure (BP) cuff, stethoscope, tendon hammer, auroscope, ophthalmoscope, ‘PR tray’ (jelly, gloves, wipes), urinalysis sticks, phlebotomy

• Scoring charts, e.g. the Abbreviated Mental Test Score (AMTS), Barthel, Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS)

• Paper and pen, dictation device

What will you do?

• Medication (check the drug cabinet or top drawer for over-the-counter and prescription drugs)

• Accepting a cup of tea will inform in several areas!

• Discuss your findings and plan with the patient and family

What to do afterwards

• Telephone or email the GP to report findings and discuss plans

Care homes

The care home sector is developing rapidly, with changes driven by:

• ↑ in numbers of severely co-morbid older people

• Reduced numbers of informal carers

• Care home legislation, improved mandatory standards, and systematic inspections by the Care Quality Commission (CQC)

• Many smaller homes have proportionately higher per capita costs, both revenue (salary) and capital (buildings) costs

• Reductions in social services funding

Until recently, there was a clear division between ‘residential homes’ (providing hotel-style services and basic personal care) and ‘nursing homes’ (providing full care to very dependent, often bed-bound patients). This distinction was always arbitrary, and as patients’ care needs fluctuated or ↑ with time, they could find themselves inappropriately housed. There is a trend to larger establishments, often in modern, purpose-built accommodation, which provide services for a wider range of dependencies under the generic term ‘care homes’.

Staffing

Most of the care provided in care homes is by staff with limited training, who nonetheless may have extensive experience. In ‘care homes with nursing’, a trained nurse has to be available on site at all times.

The quality of care is a key factor for clients and their relatives in selecting a home. Care quality is variable, often independent of the quality of the physical fabric of the home, and is difficult to judge. Observations that are useful include the subjective well-being of residents, the extent to which they are cared for outside their rooms, the attitude of staff during routine interactions with residents and their response to calls for assistance, the provision of food, drink, and call bells close to residents, and the reports of patients and family.

Regrettably, high-profile cases illustrate how poorly managed and monitored homes can harbour a very small proportion of staff ranging from uncaring to criminal in their interactions with residents. Continual vigilance by professionals helps identify such cases early.

Care home medicine

Medical care is usually provided by one or more GPs from a local ‘retained’ practice (clients are rarely able to keep their own GP), who may be in receipt of an enhanced service contract. Some community geriatricians routinely visit care homes to provide focused support and education; other areas have dedicated in-reaching MDTs. Attention should be paid to optimizing medication, maximizing preventive interventions (e.g. ‘flu, falls), and advance care planning (e.g. decisions about future hospitalization, regional ‘do not attempt cardiopulmonary resuscitation’ (DNACPR) forms). Telemedicine and other advanced clinical support can reduce inappropriate A&E attendances or admissions, particularly outside routine 1° care hours.

HOW TO . . . Advise a patient about care home placement

This task is of great importance; there are implications for the patient’s independence, quality of life, and finances. Ensure that the patient has a full assessment (ideally CGA; see  ‘Comprehensive geriatric assessment’, p. 68) at a point of maximized health and functioning and, if indicated, an adequate trial of rehabilitation.

‘Comprehensive geriatric assessment’, p. 68) at a point of maximized health and functioning and, if indicated, an adequate trial of rehabilitation.

It is unwise to make recommendations based on only your own or family’s impression—an OT’s or social worker’s perspective is complementary. Consider the prognosis and likely functional trajectory.

Some patients (often with normal cognition, living alone) may choose to go into care and are grateful for help with arrangements. They often describe loneliness or fear. If they are functionally independent, ensure that sheltered housing, day centres, or befriending have been considered as alternatives.

Most patients resist care home placement because of:

• Negative ‘workhouse’ preconceptions

• Emotional attachment to neighbours, spouse, home, pets

• A fear of loss of independence and dignity

• Anxiety over costs and loss of the family’s inheritance for family

• Stigmatization and perception that they have failed

Patients with dementia may lack insight into their care needs (see  ‘HOW TO . . . Manage a patient insisting on returning home against advice’, p. 662). Many of the principles of ‘breaking bad news’ apply, e.g. ‘warning shots’ prepare the patient. Explain what factors make it advisable to consider residential care and why other options are not feasible—use factual examples (e.g. you need help during the night and we cannot provide this at home). Clarify the contribution that other professionals have made to this assessment. The following positive points can be persuasive:

‘HOW TO . . . Manage a patient insisting on returning home against advice’, p. 662). Many of the principles of ‘breaking bad news’ apply, e.g. ‘warning shots’ prepare the patient. Explain what factors make it advisable to consider residential care and why other options are not feasible—use factual examples (e.g. you need help during the night and we cannot provide this at home). Clarify the contribution that other professionals have made to this assessment. The following positive points can be persuasive:

• By actively choosing a care home, they are more likely to get one they like. Leaving it until an emergency may remove choice

• Placements are often on a trial basis initially

• Emphasize the positive—company, hot meals, less family anxiety

• Where placement is from home and is not urgent, then a trial stay/respite period of a week or two can sometimes be arranged

• Reassure there will be help with financial/logistical arrangements

Care homes for people with dementia

Elderly mentally infirm (EMI) homes are registered to take patients with significant dementia with behaviour problems such as aggression, antisocial behaviour, or ‘wandering’. These homes are in particularly short supply. They have specially trained staff and secure entrances/exits. Some ordinary homes are not registered to take patients with a diagnosis of dementia and decline to do so, although many patients in ordinary homes will have a degree of cognitive impairment.

Further reading

Age UK. Care homes.  http://www.ageuk.org.uk/home-and-care/care-homes/.

http://www.ageuk.org.uk/home-and-care/care-homes/.

Paying for residential care

• The cost of care in a care home ranges from around £500 to over £1500 a week, depending on client dependency, local costs (e.g. house prices, staff availability), and the quality and variety of facilities provided. Social care ‘block contracts’ pay homes far less than individual private payers

• Contributions by social services are means-tested and calculated on a sliding scale, dependent upon income and capital (savings and investments, including the home, unless it is occupied by someone else, e.g. a spouse)

• ‘NHS Continuing Health Care’ is a complete package of ongoing care arranged and funded by the National Health Service (NHS), for people with particularly extensive care needs (intense, complex, and/or unpredictable). Only a small minority of people entering care homes meet the current criteria. Assessment is first by a screening tool, followed by a more extensive assessment by a health professional if the initial screening criteria are met. The provision of continuing care has been inconsistent between health authorities, and the determination of funding is often a process that is challenged by patients or their advocates

• If a nursing home is needed and Continuing Health Care funding criteria are not met, then the NHS (CCG) should pay a sum for nursing care, direct to the care home. This was formerly known as the Registered Nursing Care Contribution (RNCC) and is not means-tested

• Funding issues are addressed by a care manager (usually a social worker; see  ‘Social work and care management’, p. 96)

‘Social work and care management’, p. 96)

For extensive guidance and current information, see:  http://www.ageuk.org.uk/home-and-care/.

http://www.ageuk.org.uk/home-and-care/.

Delayed discharge

While some patients are admitted directly from their home to a care home in a planned move, the majority are admitted following an acute illness. This often occurs via a hospital setting (e.g. a patient who has a major stroke, or a pneumonia on a background of frailty and who does not regain sufficient function to return home after rehabilitation).

Where patients remain in NHS hospitals after they no longer require hospital treatment while awaiting care home beds or for other reasons (such as rehousing or while waiting for home care), they are referred to as being subject to a ‘delayed transfer of care (DToC)’. Sometimes the term ‘bed blocker’ is used, but this is pejorative and stigmatizing—most delayed patients are desperate to leave hospital and cannot because sufficient care ‘downstream’ of hospital is not available.

Such delays cost hospital services millions of pounds a year and reduce the availability of hospital beds for patients with urgent care needs. Delays in placement are due to one or more of the following:

• Shortage in care home places, especially for EMI homes. Availability varies according to region and generally stems from financial and staffing shortfalls

• Pressurized care systems may prioritize urgent cases from home over patients in hospital (a relative ‘place of safety’)

• Social services that are short of cash may limit the number of new care home places they fund

• Patients/relatives may oppose discharge because they are unwilling to accept that there is no further prospect of meaningful functional recovery

• Patients/relatives may be reluctant to move from free NHS care to means-tested social care because of financial implications

• Delays in financial or other assessments, e.g. for Continuing Health Care funding

Role of doctors caring for delayed discharge patients

• Ensure that it is clear to everyone (including the patient and relatives) that the patient no longer requires acute hospital care. Explain the supports available outside the acute hospital. Record ‘medically ready for discharge’ in the notes. Document follow-up arrangements for outstanding problems

• Continue medical monitoring, but switch to a more holistic, less intensive ‘care home medicine’ approach. Remember, however, that people living with frailty are highly prone to new or recurrent illnesses, not least hospital-acquired infections. Continue to promote enabling care, and be vigilant for complications such as deep vein thrombosis (DVT), pressure sores, dehydration, or poor nutrition

• Actively drive discharge—continual communication is crucial—with the health and social care MDTs, patient, carers, and other stakeholders. Pick up the phone if relatives do not visit during ‘doctor hours’. A walk through the ward in the late afternoon provides opportunities to update relatives and address questions or concerns

• Consider interim options while continuing to plan. For example, the patient may be able to move to an IC facility such as a CH or a ‘transitional’ bed in a private care home arranged by social services

Home care

In most countries, the majority of people needing personal care remain at home, rather than moving into an institution (e.g. care home). Their needs are provided by a carer who may be a family member, informal carers, or professional carers (self-employed or employed by a private care agency or public body). In the UK, the care needs of a patient are often specified by a care manager (social services) and then delivered by care agencies operating independently, mostly as private companies, but some with a ‘not-for-profit’ structure (e.g. social enterprise).

Needs assessment

In England, this is the process whereby a care manager determines the needs of a person and how they can be met. Assessing needs requires information from the patient and others, often including the relatives, OT, PT, and nurse. Meeting those needs requires agreement between the care manager and the client (patient, or next-of-kin/legal representative if the patient lacks capacity) after considering the options, and financial and other resources (e.g. accommodation).

Delivery of care

• The bulk of care is delivered by care assistants, who should have training in delivering personal care and lifting/handling

• In specific cases, they may be trained further to deliver care that is more complex, e.g. bowel care, thickening oral fluids, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) care

• Carers perform important supervision of patients and are often the first to note the possibility of illness

Continuity of care is an important contributor to quality. There is a risk of physical, emotional, or financial abuse by carers (see  ‘Elder abuse’, p. 674); although this is prominent in the media, such cases are relatively uncommon—most carers are hugely committed to providing the best possible care in often clinically challenging and resource-constrained circumstances.

‘Elder abuse’, p. 674); although this is prominent in the media, such cases are relatively uncommon—most carers are hugely committed to providing the best possible care in often clinically challenging and resource-constrained circumstances.

In the UK, there is a national shortage of carers, worse in some geographical areas. This can delay discharge for days or weeks. It also renders existing care packages vulnerable to unexpected carer absence, e.g. due to sickness. Care packages provided by larger organizations tend to be more robust than those provided by a single small provider operating in isolation.

Tasks routinely performed by carers

• Safe moving and handling, including hoists

• Feeding, meal preparation, and housework

• Supervision of self-medication from a monitored dosing system

• Emptying of urinary catheter, fitting of penile sheath catheter

Tasks not usually performed by carers

• Administration of medications from individual containers

Home care costs

• In the UK, state support for care fees is ‘means-tested’—a financial assessment is performed by the care manager. In general, only those with no significant savings have care costs met by the state

• Purchasing personal care is expensive. In the UK, care costs about £15 per hour (but much more in expensive areas). A care package of a total of 2h daily would therefore cost around £210 per week—less expensive than a care home, but a major financial burden for those who meet the fees themselves

Structuring the care package

• Tailor to the individual. A package usually consists of between one and four visits per day, by one or two carers. A common pattern is for two visits daily, one early (wash, dress, toilet, food preparation) and one late (evening meal, ready for bed). Lunch may consist of a pre-prepared meal, frozen and simply reheated by the patient, removing the need for a midday visit. Two carers are needed for ‘double-handed care’, e.g. turning or transferring a dependent patient

• Night-time visits are rarely needed and difficult to provide reliably. Roles may include toileting, pressure care (turns), or administering medication, but there may be other solutions (e.g. other continence management, changing medication regimens)

• Continuous (‘24h’) care is sometimes requested by patients or the family but is difficult and expensive to provide—sufficient staff are difficult to find, and the care is very expensive; a move into a care home is usually cheaper. Therefore, these packages are usually privately funded. Live-in carers are sometimes employed long-term but cannot be on hand the whole 24h, need holidays, and may go sick unpredictably

• Access to the home by carers can be difficult if the patient is immobile and cannot get to the door. Combination locks or a ‘key safe’ (conventional key locked within a small combination—or key-accessed safe) provide a secure solution

• Equipment is often necessary before a patient can be discharged and a care package initiated, e.g. hoist, bed, chair, cushion. OTs usually assess the needs and provide

Commonly reported problems with care packages

• Timing—unpredictable, too early or late (e.g. 7 p.m. ‘bedtime’ visit)

• Carers—variable quality, lack of continuity

• Cost—often a significant issue. Discourages some patients from taking an adequate (or any) care package and may result in it being stopped after a period

• Visits—may be brief; carer and patient feel rushed

The CQC ( http://www.cqc.org.uk) inspects and deals with complaints about social care providers. National minimum standards must be met if a care agency is to gain and retain a licence.

http://www.cqc.org.uk) inspects and deals with complaints about social care providers. National minimum standards must be met if a care agency is to gain and retain a licence.

Informal carers

This term describes anyone who provides regular and substantive care to a person on a non-professional basis, usually without financial reward. This is often a family member but may be a friend or neighbour.

• One in ten adults are currently providing informal care in the UK

• A total of 7 million people acted as carers in 2016, projected to rise to over 10 million by 2030

• The carer’s allowance in England is worth £62.10 per week, for an average of 35h caring—just £1.77/h (2017)

• Ten per cent of the >80s are carers, the majority providing over 60h of care per week

• The health of carers themselves is often poor—65% of older carers have long-term health problems and nearly 70% say that being a carer has an adverse effect on their mental health

This vital group of people support many older adults at home; the scale of support provided is often under-recognized. For many people, the support of informal carer(s)—often in addition to formal care—makes the difference between enforced institutionalization and remaining in their own home. For example, a mobile patient with cognitive problems may require constant supervision to ensure safety—a level of care that can only be provided by an informal live-in carer (often a spouse). This level of continuous supervision will often exceed that which can be provided in a care home, leading to dissatisfaction when patients are temporarily or permanently admitted to institutional care.

The importance of carers is recognized in a series of government and non-governmental papers and initiatives, which aim to improve information and support to carers and improve the care they themselves receive. This includes the right of a carer to a ‘carer’s assessment’, carried out by social services, which addresses the following points:

• Is the carer getting enough sleep?

• Is the carer in good health?

• Does the carer have time for themselves?

• Are relationships adversely affected by the care-giving?

• Are there concerns about work?

• Is the carer collecting all available benefits?

• Is all available help being provided (services include emotional support, help with household and caring tasks, accessing benefits and local activities, arranging respite care—see Box 2.1)

The informal carer’s role can be relentless, unrewarding, solitary, and depressing. Elder abuse is a rare, but possible, consequence (see  ‘Elder abuse’, p. 674). Support—both proactive and reactive—is essential.

‘Elder abuse’, p. 674). Support—both proactive and reactive—is essential.

As well as government resources, a number of charity and self-help organizations provide tangible and intangible support.

• Carers UK:  http://www.carersuk.org

http://www.carersuk.org

• Princess Royal Trust for Carers:  http://www.carers.org

http://www.carers.org

• Crossroads:  http://www.crossroadscare-sc.org

http://www.crossroadscare-sc.org

• The Children’s Society:  http://www.youngcarer.com/

http://www.youngcarer.com/

Box 2.1 Respite care

Being a carer is often exhausting, both physically and mentally, and often the patient finds accepting extensive help from a loved one difficult.

A successful care package must be sustainable, which includes proactive consideration of periods of relief for the carer(s). Some of the charities listed above (e.g. Crossroads) will offer a carer support worker to take over the caring role for a few hours at a time, but a longer break may be needed.

In such situations, respite care in a residential setting may provide the solution. Many care homes are able to provide flexible respite care packages. These can range from a stay of one or more weeks (e.g. to cover a holiday) to day care or an overnight stay. A regular arrangement can be made, e.g. one week in every eight may be spent in residential care.

Most local authorities operate a discretionary policy when considering funding for respite care in care homes; several weeks a year of respite may be funded if it sustains a home care arrangement where an informal carer is providing intensive support. This is means-tested.

Respite care provision in NHS settings is now very rare. Patients with challenging psychiatric needs will sometimes receive respite care on psychogeriatric wards. Terminal care patients will often be offered respite care in hospices or, less commonly, in CH wards. These services are free to the patient.

Other services

Day centres

Day centres differ from DHs (see Table 2.2). Attendance is often longer term and cognitive impairment is more common.

• Traditionally commissioned and provided by social services (sometimes jointly with health services). Now increasingly run by ‘not-for-profit’ (e.g. British Red Cross, Age UK)

• Accessed via social services (who assess needs) or by self-referral

• Offer regular attendance (e.g. once or twice weekly), with transport if needed

• There is a charge that is likely to be means-tested and varies with provision (e.g. transport, meals)

• Vary enormously but may include:

• Catering (e.g. coffee, tea, and lunch)

• Personal care (e.g. bathing facilities, hairdressing, etc.)

• Skills development (arts and crafts, adult learning classes)

• Access to health services (e.g. podiatry, district nurse)

• Leisure activities (e.g. quizzes, reminiscence, music, gardening, keep fit, trips out)

• Enables monitoring of progressive conditions (e.g. dementia) and early referral for extra support to prevent crisis

• Rehabilitation and independent living skills (may occasionally have OT, PT, and speech and language therapy (or therapist) (SALT) input)

Social clubs

Many different types that vary from county to county. Usually run by voluntary organizations. Information on locally available clubs can be obtained from libraries, the local county council, or Age UK. They include:

• Lunch clubs (often with transport)

• Special interest groups (e.g. all ♂, all ♀, ethnic groups, hobby groups—gardening, model railways, etc.)

Befriending

Scheme run primarily by third-sector organizations, e.g. Age UK, providing lonely, isolated older people with a regular volunteer visitor who will sit and chat and help with minor jobs such as fetching library books, etc.

Pet schemes

Volunteers bring pets to visit people who can no longer keep them, e.g. in care homes.

Holiday support

Voluntary organizations can provide information on suitable holidays for the disabled, and some will offer financial assistance.

Table 2.2 Differences between DHs and day centres

| DH | Day centre | |

| Medical input | Yes—patients often clinically unstable | No—medically stable clients |

| Attendance | Usually short term | Longer term |

| Staff:patient ratio | Higher | Lower |

| Functional aim | Greater independence | Usually maintenance and monitoring |

| Activities | Health/rehabilitation bias | Social/well-being bias |

| Relationship with hospital services | Close | More distant |

| Role | Complex geriatric assessment and treatment | Patient support and well-being |

| Rehabilitation | Carer relief |

Chronic disease management

• Around 60% of the adult population has a chronic (‘long-term’) condition (commonly asthma, diabetes, hypertension, and cardiac failure); older people make up most of this group

• Multiple chronic diseases lead to increasingly complex healthcare needs and provision and are a particular phenomenon among elderly people, who become increasingly frail as chronic problems accumulate and progress

• Most needs are managed in 1° care, although in 2° care, the 10% of the population who have high-level chronic disease account for over 50% of inpatient bed days

There has been a shift in emphasis away from a reactive acute sector response towards the proactive management of chronic disease. Lessons have been learned from ‘managed care organizations’ in the USA (such as Kaiser Permanente in California) where comprehensive healthcare is provided to a defined population by a single ‘unified’ provider; there are then built-in incentives to actively manage chronic disease, as this may reduce acute (and total) expenditure.

Severity of chronic disease can be summarized as follows:

• Level 1—70–80% of patients who have a single chronic disease (e.g. hypertension). Management is enhanced by ↑ personal responsibility for the condition with education and encouraging active participation in care. Patient experts are developed who take on some of the education of their peers

• Level 2—more complex patients, but still with commonly recognized complications of disease (e.g. Parkinson’s disease). Management is at a population level, with broad guidelines for care, protocols, and patient pathways. The approach is multidisciplinary with innovative delivery of a standard care set (email, telephone, group meetings, nurse clinics, etc.)

• Level 3—highly complex patients with individual needs (e.g. frail elderly patient with multiple interacting pathologies). Active case management by a key worker (often a nurse) promotes early intervention to prevent crisis and facilitates joined-up care

In coordinated proactive care, a competent lead clinician (often a specialist nurse) supports the identification of needs, comprehensive initial assessment, engagement of complementary functions (e.g. social services, voluntary groups, condition-specific teams), creation of a proactive care plan, and communication of that plan to key people/teams (patient, carers, ambulance service, community and acute teams).

The management of older patients who are frail is at the most challenging end of the spectrum of chronic disease management; guidelines and protocols are of less value than insightful, holistic, experienced clinicians who can work flexibly to deliver outcomes important to the individual.

The following are useful ways of managing these patients:

• ‘Frailty registers’ to identify and risk-stratify patients

• Use of information systems and shared patient records

• Specialist nurses, e.g. community matrons with close medical backup

• Involving community MDTs, district nurses, and health visitors

• Coordinated care—using care managers

• ↑ liaison between 1° and 2° care with free and frequent sharing of information and care goals and easy access to urgent clinical review (e.g. in urgent assessment clinics)

• Utilization of ambulatory care services to monitor those most at risk of acute deterioration

Further reading

Goodwin N, Dixon A, Anderson G, Wodchis W; The King’s Fund (2014). Providing integrated care for older people with complex needs.  https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/providing-integrated-care-older-people-complex-needs.

https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/providing-integrated-care-older-people-complex-needs.

Primary care

• Ninety per cent of older people see their GP at least once a year

• One-third of GP appointments are for adults over 65 years

• Consultations tend to be more frequent, more complex, and more prolonged than in younger patients

• Consultations in the home are declining, as they are time-consuming, but older people remain the biggest user group. Increasingly, home visits are performed by non-medical clinicians such as nurses or paramedics, liaising as needed with GPs in the team

• GPs tend to be aware of the health problems of their older patients—those that do not attend tend to be healthy. The most common consultations are for respiratory and musculoskeletal problems (whereas 2° care sees more complications of vascular disease such as ischaemic heart disease (IHD) and stroke)

• >70% of those >75 are on three or more medications—treatment is usually prescribed and monitored by the GP

• Most older people live with chronic conditions (such as arthritis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), diabetes); scheduled care is usually by GPs and the extended 1° care team who play a key role in long-term management and 2° prevention

• Input from 2° care may come at a time of crisis (through admission to hospital, rapid referral clinics) or may be planned and more extensive, with regular clinic or day hospital attendance

• Increasingly, teams are integrated across 1° and 2° care—they work closely together, in ways that are patient-centred, rather than service- or team-centred, with sharing of information, proactive care, and advanced expertise ‘closer to the patient’ in community health settings. GPs act as a vital link between hospital and community services, identifying patients at particular risk of crisis, so allowing preventative action to be taken (a skill that is as much intuitive as systematic)

• Patients with multiple co-morbidities and/or extreme frailty may benefit from proactive identification and a preventative multifactorial intervention, focusing on optimizing chronic disease management, advanced care planning, social care management, and strategies to escalate care rapidly during acute illness. GPs, community nursing, health visitors, and therapists all have a role to play

• GPSIs in geriatrics can act as community specialists, working with other MDT members and liaising with hospital departments. They will often take the Diploma in Geriatric Medicine (DGM) (see  ‘Diploma in Geriatric Medicine’, p. 48)

‘Diploma in Geriatric Medicine’, p. 48)

• NHS strategy is for rapid development of an extended 1° care and community capability. Key elements include merger of existing smaller practices into ‘mega-practices’ with much larger clinical teams and a greater specialist capability; ‘polyclinics’ (sites of extended healthcare, including 1° care, specialist clinics, and advanced diagnostics); outreach of 2° care to community settings; and decision support focused on ‘high admission’ settings such as care homes

Further reading

NHS England. NHS Five Year Forward View.  https://www.england.nhs.uk/five-year-forward-view/.

https://www.england.nhs.uk/five-year-forward-view/.

Careers in UK geriatric medicine

Consultant career pathway

• After qualification, Foundation level 1 and 2 jobs are undertaken; most include some time in geriatric medicine or in a specialty with geriatric team in-reach (e.g. acute orthopaedics). This is followed by competitive entry into Core Medical Training (2 years); most doctors will obtain the MRCP (Membership of the Royal Colleges of Physicians of the United Kingdom) at this stage

• Competitive application for a Specialty Registrar post may follow a period of research, but most commonly is directly after core training

• Specialty training in geriatric medicine takes only 4 years but is almost always paired with another specialty, e.g. general internal medicine, rehabilitation medicine, or stroke medicine. Dual accreditation typically takes 5 years

• Triple accreditation in geriatric medicine, general internal medicine, and stroke medicine is an increasingly popular career path and takes 6 years

• A few ‘progressive’ trainees combine training in unusual, but innovative and valuable, ways, e.g. emergency medicine (A&E) with geriatric medicine

• The ‘Shape of Training’ report recognizes complexity and ageing as key challenges and recognizes the need for doctors—such as geriatricians—who can provide ‘general care in broad specialties across different settings’

Non-consultant career grade pathway

• Includes specialty doctors and other locally determined posts

• Responsibilities of the post-holder vary considerably

• The main differences from a consultant post are that roles are often very clinically focused, with modest responsibility for management, administration, and training, and that overall clinical responsibility remains with a consultant

• There is a pathway to convert to consultant grade, but it is time-consuming and expensive (‘CESR: Certificate of Eligibility for Specialist Registration’)

Primary care physicians

• GPs may wish to sub-specialize in geriatric medicine

• They may provide clinical leadership and care within a practice, a cluster or federation of practices, or in-locality functions such as a CH or a multidisciplinary acute/crisis team

• GP skills are also very valuable in larger hospital settings, including the ED and acute assessment units (medicine or frailty), and in ward settings (acute or rehabilitation)

• Such GPs often have significant experience in geriatric medicine during their vocational training scheme and may obtain the DGM

• Some GPs have migrated almost completely to an acute ‘interface’ setting, developing a much expanded acute capability and working at the front foor of hospitals ‘shoulder to shoulder’ and as peers with hospital colleagues

Non-European overseas doctors

• Many overseas doctors wish to train in the UK for a period of time. It can be challenging to secure that opportunity; the first post is often the most difficult to obtain

• Many overseas doctors begin with clinical attachments, which are unpaid observer posts that enable the doctor to become familiar with the UK healthcare system

• Following the UK decision to leave the European Union (EU), arrangements are likely to change, but currently (2017):

• Doctors trained in the EU may apply for any job in the UK

• Non-EU-trained doctors are only able to take up a training post that cannot be filled by an EU applicant

• The Royal College of Physicians (RCP) Medical Training Initiative (MTI) supports placement of internationally trained graduates as paid training fellows within UK hospital trusts

• It is essential for non-EU-trained doctors to take the PLAB (Professional and Linguistic Assessments Board) examination ( http://www.gmc-uk.org/doctors/plab.asp)

http://www.gmc-uk.org/doctors/plab.asp)

• Obtaining the MRCP and the DGM helps to define an interest and demonstrates capability

Diploma in Geriatric Medicine

Qualification awarded by the RCP (UK) to recognize ‘competence in the provision of care of older people’.

Candidates

The qualification is appropriate for any doctor who cares for older people, including GPs, psychiatrists, trainees in internal medicine, and those in specialties, such as orthopaedics or general surgery, where the patient cohort is increasingly complex and frail.

Candidates must be 2 years post-medical qualification and have held a post in geriatric medicine.

Studying towards the Diploma is also of value to junior doctors who are current trainees in geriatric medicine, as it motivates them to study important topics that recur in the MRCGP (Membership of the Royal College of General Practitioners) and MRCP and rewards them with a tangible product following an attachment.

Satisfactory completion of the DGM may contribute to more substantial geriatric qualifications (e.g. Masters), so it may also be pursued by specialist trainees, although it is not primarily designed for this group.

Examination structure

Written section

• 3h—100 ‘best of five’ (multiple choice) questions

Clinical examination

• 76min—4 × 14min stations (incorporating history taking, comprehensive geriatric assessment, communication skills and ethics, and clinical examination skills), with 5min prior to each station

Syllabus

• Demographic and social factors

• Features of atypical presentation of disease

• Management of common conditions

• Domiciliary care for the disabled

• Legal and ethical considerations

• Knowledge of social services

• Special geriatric services and facilities such as day centres, nursing homes, etc.

Full details of eligibility, entry, examinations, and syllabus, are at:  https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/diploma-geriatric-medicine

https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/diploma-geriatric-medicine