Aging and Menopause

Jacob A. Moorad and Daniel E. L. Promislow

OUTLINE

1. A natural history of aging

2. Theories for the evolution of aging

3. Menopause

4. Pressing questions on the evolution of aging

Given enough time, organisms lose vigor as they age. Traits that may have once seemed optimized for survival and reproduction degrade, increasing the risk of death and reducing fertility. On the surface, it seems paradoxical that natural selection, which always favors increasing fitness, should permit aging to be nearly ubiquitous. However, evolutionary theory provides simple but powerful hypotheses to explain why humans senesce and die. At its heart, this theory states that fitness depends more on what happens early in life than what happens at old age. In other words, there is more natural selection for early-life function. A basic tenet of aging theory is that if the survival or fertility effects of early-acting and late-acting genes are independent but equally distributed, natural selection will favor the evolution of aging in very predictable ways. But do genes really act this way? We humans age, of course, but our species is unusual in that middle-aged females undergo menopause. What is so special about our species, and given that men die sooner than women, why is reproductive cessation in males neither as abrupt nor as complete as in women?

GLOSSARY

Aging. See senescence.

Antagonistic Pleiotropy. A proposed mechanism for the evolution of senescence. Under this model, selection favors alleles with early-acting beneficial effects that have pleiotropic but deleterious effects at late age.

Disposable Soma Theory. The theory that senescence evolves owing to trade-offs between investment in reproduction and investment in somatic (bodily) maintenance and repair. The optimal strategy is one that favors limited investment in maintenance and repair, such that senescence is inevitable.

Gene Regulatory Network. The complex web of interacting genes, some of which regulate themselves and/or downstream target genes, some of which are regulated by upstream regulatory genes.

Genetic Correlation. The statistical dependence between two traits caused by genes that determine the values of both traits.

Genetic Variance. A measure of phenotypic differences among individuals that are caused by genetic differences.

Inbreeding Depression. The loss of fitness that is associated with the mating of relatives.

Iteroparous. Capable of reproducing multiple times throughout life.

Menopause. The late-onset, irreversible cessation of reproductive capability experienced by women, usually at around 50 years of age.

Mutation Accumulation Theory. Theory based on the notion that the strength of selection declines with age; as a result, late-acting germ-line deleterious mutations accumulate over evolutionary time, leading to age-related declines in fitness.

Programmed Death. The idea, generally rejected by most evolutionary biologists as a principle cause of aging, that natural selection favors senescence, such that genes that actually cause death can spread through, causing catastrophic mortality.

Semelparous. Reproducing just once, and then dying; examples of semelparous organisms include spawning salmon and some species of bamboo.

Senescence. An age-related decline in fitness components, including vital rates (age-specific survival or fertility), behavior, physiology, and morphological traits; used interchangeably with aging.

Natural selection is a powerful force. It can shape elaborate developmental pathways that give rise to exquisite morphological characters, it can shape complex behaviors that allow organisms to survive in what to us seem the most inhospitable of environments, and it has even endowed organisms with the ability to heal wounds and to repair themselves. But these characteristics leave us with a puzzle: If selection endows organisms with the ability to repair both genetic and structural damage, why can it not prevent organisms from eventually falling apart as they age?

What Is Aging?

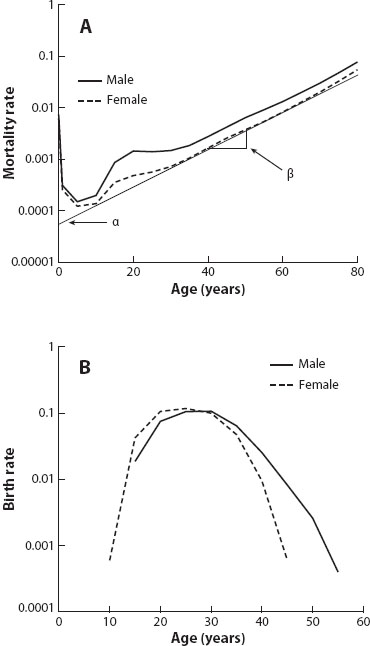

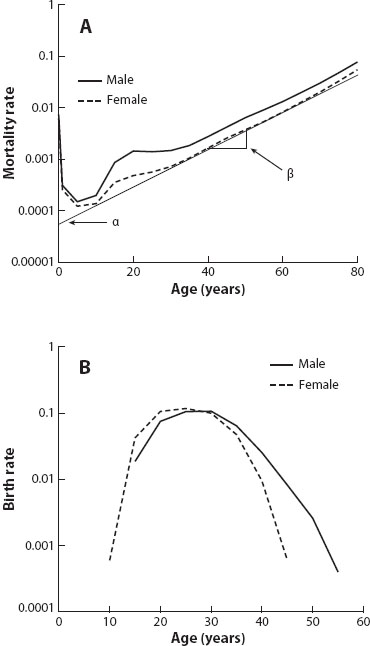

In all human populations, the probability of dying varies across ages, following a bathtub-shaped trajectory (figure 1A). Mortality rates are relatively high in utero and in the months immediately after birth. They then decline, reaching a minimum in late adolescence. From this age onward, the probability of dying increases. In humans, the risk of dying doubles every eight years. In the late twenties, fertility starts to decline, as another manifestation of the aging process (figure 1B).

Figure 1. (A) Age-specific mortality in the United States, males and females, 2007 (see http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/deaths.htm). The thin solid line represents a Gompertz curve fitted to adult mortality, μx = αeβx, where μx is instantaneous mortality at age x, α is the intercept of the line, and β, the slope of the line, represents the rate of aging. (B) Age-specific birth rate in the United States, males and females, 2007 (see http://www.census.gov/compendia/statab/cats/births_deaths_marriages_divorces.html).

We measure aging (or senescence; here we use the terms interchangeably) as the age-related rate of decline in fitness traits. It is manifested at the level of the population and of the individual. Demographic senescence refers to the age-related decrease in the frequency of survival and mean reproductive output of groups of same-age individuals. Physiological senescence refers to late-age-related changes in individual phenotypes. Life span per se is not a measure of aging but an outcome of cumulative mortality risks, some of which are constant throughout the life span and some of which vary with age.

Aging in Model Systems

Most of what we know about the biology of aging comes from studies of lab-adapted organisms—yeast, nematode worms, fruit flies, mice, and rats. The general patterns of aging in both survival and reproduction seen in humans are much the same in these laboratory populations.

Much has been learned from these lab-adapted species about the way that both environmental and genetic factors can shape longevity. In many species, researchers have been able to enhance age-specific survival and late-age physiological function simply by restricting nutrient intake. In most cases, this effect appears correlated with the cessation of reproductive output. The fact that diet restriction can increase life span in species separated by a billion years of evolution has led some to argue that the ability to survive nutrient stress is an ancient adaptation. However, others have suggested that the response may be a side effect of a very modern adaptation to the lab environment. The response to nutrient restriction is much less clear in wild-caught animals.

In the early 1980s, Michael Rose and his colleagues found that artificial selection in fruit flies could dramatically extend mean life span, demonstrating that there was a large amount of genetic variation for longevity. In subsequent work, researchers have shown that changes in the structure or expression level of single genes in many pathways—most notably, genes associated with insulin/insulin-like growth factor signaling—can greatly enhance life expectancy. These results raise an evolutionary question: If altering a gene can increase life span in a worm or a fly, why has nature not already done the experiment? The answer likely follows from the observation that these life-extending mutations generally reduce fitness, such as by decreasing early-age fertility.

What can these lab-based studies reveal about patterns of aging in the wild? Until the 1990s, it was commonly assumed that aging did not, in fact, occur in natural populations. Biologists argued that wild animals would not live long enough to manifest signs of aging. It may be true that wild animals showing obvious signs of infirmity are rarely seen, as they are likely to have been killed by predators. But closer demographic analysis—in particular, measures of age-specific mortality and fertility—have shown clear signs of age-specific declines in fitness components in birds, mammals, and even wild insects.

While almost all species show signs of aging, some live notably longer than others. These differences have led to the recognition that there are certain ecological factors associated with long life span. For example, species that fly (bats and gliding mammals, as well as birds) tend to be long-lived relative to terrestrial species of similar mass. Similarly, life span is longer in species that are well armed against predators (like porcupines) and in species that live underground (naked mole rates, queen bees, and ants).

Some species of animals, such as hydra, appear to avoid aging altogether, with a constant risk of mortality throughout life. Other animals simply live what to humans seems like an extraordinarily long time, including Galápagos tortoises (almost 200 years), some species of rockfish (over 200 years), and even some small clams (over 400 years). Whether these long-lived species show signs of senescence is unknown. However, it is clear that aging can vary and is subject to evolution. This observation is borne out by explicit phylogenetic studies as well.

Sex Differences and Senescence

In the temperate rain forest of eastern Australia, males in the marsupial species Antechinus stuartii become sexually active during a brief one-week period in the middle of winter. By the end of this brief mating season, all the females in the population are pregnant, and half will survive to breed next year. All the males are dead. Such a dramatic difference between semelparous males and iteroparous females is unusual, but in almost all mammal species, males die sooner than females. In the final section, we consider possible explanations for this widespread pattern.

Aging in Humans

The patterns of aging in humans (and in nonhuman primates) mirror the general pattern seen in model systems, with age-related declines in survival and fertility and higher rates of mortality in males than in females. Human females differ in one important respect in that they show a prolonged period of postreproductive survival (menopause). We discuss the evolutionary explanations for this later (see also chapters VII.10 and VII.11). Perhaps the most striking pattern in human mortality is that which has taken place over the past 250 years: a 90 percent decline in childhood mortality and a 50 percent increase in life expectancy at birth. The percentage of people living past the ages of 60 or 70 is higher now than at any other time in human history. But to fully understand the evolutionary forces that have shaped human aging, it is necessary to know what human demography looked like prior to modern medicine and sanitation.

In nonindustrial indigenous societies, life expectancy at birth can be as low as 35 or 40 years of age. But for those individuals who make it through the riskiest period of infancy, there is a high probability of surviving to age 60 or 70 or beyond. While the immediate risk of dying is higher for adults in these populations than for those living in developed countries, the general pattern of age-specific mortality and fecundity is very similar. Baseline mortality rates have changed dramatically over time, but rates of aging appear to be quite constant among different human populations.

2. THEORIES FOR THE EVOLUTION OF AGING

The natural world offers up limitless examples of the power of natural selection. Aging differs among populations and organisms, and these differences appear to have been shaped by natural selection. But this observation then leaves us with a puzzle: Why does natural selection fail to evolve organisms that can function indefinitely, repairing any damage that arises along the way? In fact, this seems to be the case for hydra. So, why is this not the dominant pattern? Over the past century, three themes have emerged in attempts to understand aging from an evolutionary perspective—aging as adaptation, aging as maladaptation, and aging as constraint.

Aging as Adaptation

The German biologist August Weismann is best known for his germplasm theory of inheritance in animals, which recognizes that the germ line and somatic tissue represent two distinct lineages, with inheritance occurring only through the germ line. But Weismann is also credited with formulating the first evolutionary theory of aging in 1881 when he proposed that death in late age is adaptive and that natural selection actively favors the evolution of a death mechanism. This idea has become known as the programmed death hypothesis. Weismann emphasized that natural selection acts for the good of the population or species (not the individual) by removing useless individuals from the population and making room for the young.

Researchers have raised many objections to this theory. First, this mechanism requires the preexistence of senescence to explain selection for senescence, because it is predicated on the notion that the old are less fit than the young. Thus, this mechanism certainly cannot explain the origin of senescence. Second, the model gives group selection a central role in the evolution of aging but neglects individual-level selection, which should favor longer life span, all else being equal. While recent evolutionary theory considers a role for group selection in the evolution of many kinds of traits (social behaviors, for example), the conditions that allow group-level selection to overwhelm individual-level selection are very restrictive. The evolution of programmed death would require intense group benefits to overwhelm the great loss in individual fitness associated with early death.

Aging as Maladaptation

The first modern explanation for the evolution of aging came from cell biologist Peter Medawar’s work in the 1940s and 1950s. Medawar was inspired by evolutionary biologist J.B.S. Haldane’s 1941 study of Huntington’s disease (HD). Haldane was struck by the fact that HD is a lethal disease caused by mutation at a single, dominant gene. Surely, natural selection should eliminate such a gene from the population, and yet it struck 1 in 18,000 people in England. Haldane explained its prevalence in terms of two forces, mutation and selection (see chapters III.3 and IV.2). While selection works to purge the genome of genes that increase mortality, germ-line mutations that lower survival are constantly being generated. Under mutation-selection balance, natural selection and mutation work in opposition, and an evolutionary equilibrium is met when the two forces are equal in magnitude. Thus, at such an equilibrium, lethal genes can persist in a population. However, the frequency of these alleles should be very low unless selection is very weak.

Consider the case of HD. Affected individuals typically begin to show symptoms around 40 years of age, by which time carriers could have already passed the lethal allele on to their offspring. For most individuals, the lethal consequences of the gene will be seen only after they have finished reproducing. As a consequence, there will be very little natural selection against the allele.

Whereas Haldane saw one particular lethal allele spreading because of its delayed effects, Medawar saw that the same was true for all alleles with late-acting deleterious effects. More generally, he recognized that the later the age at which the effects of a deleterious allele occur, the weaker is the ability of natural selection to eliminate that allele from the population.

If mutations can have age-specific effects on mortality or fertility (their effect is not manifested at all ages), then at mutation-selection equilibrium, the frequencies of age-specific mutations that decrease fitness will be smallest at early age and greatest at late age. This evolutionary mechanism, usually referred to as the mutation accumulation, or simply the MA hypothesis, was first suggested by Medawar in 1946. This model has been extremely influential because it is both a very general and very simple evolutionary model that assumes only that selection decreases with age (as William Hamilton, also the father of kin selection, was to show with his mathematical models 20 years later) and that at least some mutations have effects that are confined to specific ages. We can consider these the necessary and sufficient conditions for the evolution of aging.

Aging as Constraint

In 1957, George Williams built on Medawar’s insight in one simple but critical respect. Consider a mutation that affects fitness at two different ages, first quite early in life, and then at some much later age. If the direction of the effects at both ages is the same (both beneficial or both deleterious), then natural selection will lead to the mutant allele’s fixation or loss, respectively. Neither case is very interesting from the perspective of aging, but suppose that the effects of the mutation are in opposite direction at the two ages. Consider a mutation that decreases survival or fertility early in life but increases it later. Selection might favor its spread and contribute to extended longevity of old individuals, but because selection cares more about changes early in life, the early costs of the allele would tend to outweigh its later benefits. In contrast, mutations with benefits early in life and costs late in life are more likely to be favored by natural selection, and to spread through a population and lead to senescence. Importantly, this antagonistic pleiotropy (AP) model does not view aging as an adaptation, since it is not the aging per se that increases fitness, but as a constraint associated with other adaptations that evolve to maximize early life survival and/or fertility.

Twenty years after Williams published his AP model, Tom Kirkwood (1977) suggested a plausible model of AP based on how selection is expected optimize the allocation of limited resources across ages. Kirkwood’s disposable soma model argued that there is substantial energy demand both from reproductive functions and from functions relating to the maintenance and repair of the individual (the soma). Given that energy is a limited resource, individuals cannot have it all. Selection favors the functions that lead more directly to increased fitness, which in this case, is the production of offspring at the cost of less energy invested in maintaining and repairing old soma. Thus, the equilibrium level of investment in the soma is one that fails to ward off the effects of senescence.

Genetic Variation and Aging Theory

Starting in the mid-1990s and motivated by quantitative genetic models that seemingly provided diagnostic tests of MA versus AP gene action, evolutionary biologists invested considerable effort in trying to describe the standing genetic variation for aging. These studies compared components of genetic variation and inbreeding depression at early and late life with the expectation that they should change if MA causes aging. Work was carried out primarily in fruit flies, but it also included studies of soil nematodes, seed beetles, and even hermaphroditic snails. Most of these studies found putative support for MA. However, Moorad and colleagues have argued recently that quantitative genetic tests of genetic variation and inbreeding depression are not truly diagnostic. From their perspective, the genetic results support the contention that senescence evolved, but they do not favor any one particular model.

Turning to AP, we expect negative genetic correlations between early-age and late-age fitness traits. Research in this area begins with Michael Rose’s landmark experiments with fruit flies in the early 1980s. When Rose selectively bred from progressively older individuals, he observed not only a dramatic increase in life span but also a reduction in fecundity during early life, a result since replicated in other labs. While these results were consistent with predictions from AP, we now recognize that these results can also be interpreted as evidence for MA, because selection against early-acting fecundity mutations in these experiments is relaxed independently of late-life survival. Researchers also have found evidence for negative genetic correlations between traits at different ages in natural populations of swans and red deer, among other species. However, negative genetic correlations cannot distinguish between early-acting advantageous AP mutations that have caused aging to evolve and new, disadvantageous AP mutations that reduce aging. The latter kind of gene may have a negative, but transient, effect on life span before its removal from the population by natural selection.

The most compelling evidence for the AP mechanism comes from single genes that are known to extend life span and occur with high frequency (or are fixed in a population). The best example of this sort of gene is the polymorphic TP53 gene in humans, which appears to create a genetic trade-off between risk of cancer and risk of aging. One variant of the gene (R72) reduces the risk of cancer but decreases longevity. The alternative P72 allele has the opposite effect.

All these studies address patterns of standing genetic variation. However, existing genetic variation depends not only on how selection acts but also on the nature of the mutations that enter the genome. By examining the distributions of new mutations, it was hoped that a picture of the raw material for evolutionary change could be resolved without the confounding influences of natural selection. These studies revealed four interesting characteristics of new mutations unanticipated by evolutionary theory:

1. New mutations increase mortality more at early age than at late age.

2. Genetic variance caused by new mutation is highest at early ages.

3. New mutations increase mortality at multiple ages (i.e., these generate positive genetic correlations across ages).

4. Effects of new mutations become more age independent (i.e., pattern 3 becomes stronger) as more and more mutations accumulate.

These findings do not support AP (genetic correlations arising from new mutations are positive, not negative). They may also explain two of the aforementioned patterns that are not anticipated by the basic evolutionary models: the occasional reduction in genetic variance with age (2) and mortality deceleration (1).

There is no consensus regarding the primacy of one evolutionary mechanism of aging over the other. Results from quantitative genetic analyses, artificial selection experiments, and mutation accumulation studies are equivocal, which may reflect the fact that MA and AP models are highly idealized and that real aging genes have characteristics of both.

3. MENOPAUSE

Menopause is an unavoidable physiological transition that defines the end of an individual’s reproductive capacity. In human females, it lasts between one and three years, occurring at 50 years of age, on average, and is presaged by about 20 years of declining fertility (reproductive senescence). Menopause is marked by a loss of ovarian function (including reduced endocrine production) leading to sterility and a suite of symptoms, including hot flashes, insomnia, mood swings, and increased risk of osteoporosis and coronary heart disease. Human males also lose reproductive function over time, but men lack a similarly well-defined period of fertility loss. Accordingly, there is no upper limit to the age at which men can reproduce (apart from death); the record for extreme male reproduction appears to be 94 years.

While the existence of female menopause is firmly established in humans, little is known about how widespread menopause is in other animals. Some captive animals, such as rats and rhesus monkeys, appear to exhibit female menopause but do so at advanced ages that are believed to be largely unattainable in the wild. Natural populations of cetacean species, such as short-finned pilot whales and orcas, are observed to have large fractions of females that live beyond the age of reproductive cessation. As one can imagine, there are substantial challenges to collecting data to determine how fertility changes with age in natural populations. Nevertheless, this information is critical to comparative efforts trying to understand the forces of selection that cause menopause to evolve.

Why menopause? is one of the more fascinating (and open) questions of evolutionary demography. If menopause is an adaptation, then we are confronted with the challenge of explaining how natural selection can favor the evolution of a trait that ends one’s ability to reproduce and transmit genes to the next generation. One obvious explanation is that menopause is simply a manifestation of reproductive senescence brought on by the age-related decline in the strength of selection. But there is a flaw in this reasoning. This argument assumes that historical human populations were characterized by such high rates of adult mortality that adult women rarely lived into their fifties, such that selection could not act with sufficient strength to avoid the accumulation of late-acting sterility mutations. We see menopause in our postdemographic transition world, this thinking goes, because life spans of modern humans are unnaturally long.

As noted earlier, indigenous human populations have very low life expectancy at birth, but for those who make it through those difficult early years, the probably of surviving well past the age of 50 is quite high. In this light, researchers think that menopause predates modern human societies.

Perhaps the greatest problem with the “menopause as modern artifact” argument is that human males tend to die before females and yet they do not undergo the abrupt reproductive cessation that is observed in females. As mentioned earlier, this pattern of higher male mortality is widespread among mammals. Moreover, evidence from natural populations of baboons and red deer (two species with pronounced elevated male mortality) indicates that the reproductive life spans of males are even more abbreviated than those of females owing to intense male competition for mates (old males do not compete well against their younger counterparts). If menopause were simply reproductive senescence, then we would expect reproductive cessation to be widespread in males and to occur earlier in life than female menopause. This pattern is not observed.

A more tenable hypothesis for female menopause holds that it is an adaptation. However, the fitness benefits of menopause may be realized by the descendants instead of being conferred to the female in menopause (the benefit to a descendant is indirect, while the cost to the female is direct).

There are two common adaptive hypotheses for explaining menopause—the mother hypothesis and the grandmother hypothesis. In these models, genes that promote menopause are associated with higher fitness in the children of mothers (or grandmothers) in menopause because these children live longer and/or reproduce more than children that are descended from females that do not undergo menopause. At their essence, these models imagine that there is conflict between the fitness interest of the maternal ancestor and her descendants (in this sense the evolution of menopause resembles the evolution of altruism). Menopause is expected to evolve at the age at which the benefits of menopause help the children twice as much as menopause hurts the mother (or helps grandchildren four times as much as it hurts the grandmother). Tests of these hypotheses are currently fertile ground in aging research. The first requirement, that the timing of menopause has a genetic basis, has been met. In humans, the age of menopause in the mother predicts to some degree the age of onset in daughters, suggesting a heritable basis to the age of onset of menopause. The second requirement, that menopause increases descendant fitness, is discussed later. Note that the validity of the mother hypothesis and the grandmother hypothesis are both subject to lively debate, with supporters and detractors on both sides.

The Mother Hypothesis

The mother hypothesis focuses on the observation that the risk of mortality from complications in pregnancy or delivery increases dramatically as women age. For example, rates of gestational diabetes increase fourfold in pregnant women over 40 compared with those under 30. Problems associated with hypertension may be as much as five times more common among older pregnant women. Complications from both of these, as well as an age-related increase in breech births, increase the frequency of operative births in modern societies. Obviously, this was not an option over human evolutionary timescales, and we can safely assume that many of these age-related problems would have resulted in the death of the mother. In the past, these deaths would have denied existing descendants the care or resource provisioning that a mother would otherwise have provided. In this light, menopause might have mitigated a mortality risk in older women. However, recent analyses suggest the increased risk of mortality for existing offspring due to losing a mother, other than for those who have not yet been weaned, is actually minimal. In traditional societies, allocare by a mother’s relatives may have greatly reduced the cost of her death.

The Grandmother Hypothesis

The grandmother hypothesis argues that at some age the benefits to women of helping their daughters care for offspring outweigh the benefits of continuing to produce more sons and daughters. At this age, selection will favor a shift to care directed from grandmothers to grandchildren. Studies from preindustrial Western societies as well as from indigenous societies show that in at least some populations, older daughters have more children if their mothers survive and that the grandchildren of living women are larger and have lower mortality than those of dead women. See chapter VII.11 for further details.

Reproductive Competition

A third adaptive argument for the evolution of menopause, recently suggested by Michael Cant and Rufus Johnstone, notes that humans evolved in the context of small groups and that reproduction within these groups came at some expense to the social partners of the mother. Because dispersal among groups seems to have been dominated by young females, females tended to become more closely related to their group as they aged (older females were more likely than young females to have sons in the population). As a result, the social cost of reproduction by older females was borne by her relatives, but the relatives of young females were not affected by her reproduction. Cant and Johnstone reason that the relationship between degree of relatedness and female age caused kin- or group-level selection to favor the cessation of fertility most in the older females.

4. PRESSING QUESTIONS ON THE EVOLUTION OF AGING

Why Don’t All Species Hit a “Wall of Death”?

In 1966, William Hamilton explained how the force of selection would change with age, given explicit values of age-specific fecundity and survival. Hamilton’s model made clear qualitative predictions about the increase of mortality with age. Specifically, there should be three distinct phases. First, age-specific mortality is constant and low from birth until the first age in the population at which reproduction occurs. From then, mortality rates increase with age until that at last reproduction. Beyond this point, selection can no longer act, and postreproductive populations should hit a sudden “wall of death.”

Aside from its occurrence in semelparous species like Pacific salmon and Antechinus, this wall of death is generally not seen. How can the fact that populations persist beyond the end of reproduction be explained, and that at least in iteroparous plant and animal species, a wall of death is not seen? One reason might be that the effects of individual mutations are less ephemeral than imagined by Medawar or Hamilton, and there are some genes that affect survival at both reproductive and postreproductive ages. As a result, genes that increase postreproductive mortality are not entirely hidden from the purifying effects of natural selection. This sort of gene action may have other, more subtle effects on human mortality, which we discuss in the next section. Another possibility is that even after the age at last reproduction, there will still be selection to survive and help one’s offspring reproduce, as discussed earlier.

In many populations, mortality rates level off and can even decline at very late ages. However, scientists have yet to determine definitively whether this pattern of late-age mortality deceleration is a statistical artifact (due to variation in mortality rates among subcohorts within a population) or an evolutionary consequence of selection pressures (or lack thereof) at late ages.

Is There a Limit to Human Life Span?

In a now-famous wager, biologist Steven Austad and demographer S. Jay Olshansky placed a $500 million bet as to whether there will be at least one human who has lived to at least the age of 150, and with mind intact, by the year 2150. Austad and Olshansky don’t expect to be around to collect on their wager, so they have each invested $150 and, with careful investment, anticipate that the funds will provide the heirs of the winner half a billion dollars. Austad argues that medical improvements and technological discoveries will lead to 150-year-olds by 2150. Conversely, based on his analysis of existing demographic data, Olshansky argues that humans are already close to the limit of their life span.

Is there an evolutionary response to this question? Consider Rose’s experiments with fruit flies, in which selection for late age at reproduction doubled the life span of flies in just a few years. This reasoning can be pursued with the following thought experiment (albeit an extreme one). Imagine a human population in which only men and women over the age of 40 reproduced. All else being equal (that is, considering only the effects on life span and assuming everything else stayed the same), would this give rise to, let’s say, in 100 generations, or about 4000 years, a significantly longer-lived population? In the case of Rose’s fruit flies, it is thought that selection favored longer life span because only those individuals with genes that promote long life span had a chance to reproduce. In a modern human population, the vast majority of individuals survive to age 40, so there is likely to be little selection on genes affecting survival rates prior to age 40. Rather, a response to an increase in late-age fertility would be expected.

While this thought experiment is an exaggeration, ages at reproduction in industrialized countries are much later now than they were a century ago. If this trend continues, then many centuries from now, our descendants may find that self-imposed selection on fertility has slowed its rate of decline. It remains to be seen whether there are as-yet-unknown deleterious mutations with extreme late-age effects waiting to be discovered once individuals commonly exceed 110 years of age.

Why Do Males Die Earlier Than Females?

There is still no clear answer to why males and females should age differently. However, it is likely that this difference is associated with those traits that define “male” and “female.” After all, the fundamental difference that defines two sexes is the size of the gamete that is produced, with female being the sex that produces larger (and typically fewer) gametes. Do sex roles explain why males and females age differently?

Starting with Charles Darwin and Alfred Russell Wallace, evolutionary biologists have been fascinated by the elaborate displays that animals use to attract the opposite sex. Typically, it is the males that bear these traits and/or that compete with one another for access to females. A great deal is now understood about the selective forces that have led to the evolution of secondary sexual traits and mating behavior (see chapters VII.4–VII.6). Less understood are the immediate (proximate) and long-term (evolutionary) costs of these traits.

In thinking about this problem, researchers have created a rich body of literature that falls at the intersection of two conceptually rich fields of study, uniting theories for the evolution of aging with theories of sexual selection and sexual conflict. A 2008 review by Russell Bonduriansky and his colleagues summarized several predictions that have emerged in the literature. These include suggestions that (1) both within and among species, males that invest more heavily in secondary sexual traits should age more quickly; (2) conflicts of interest between the sexes should lead to higher rates of aging, and if one sex has an advantage over the other in this conflict, it should age more slowly than the other; and (3) the influence of sexual selection on sex differences in aging should be mitigated by the degree of genetic correlation between the sexes.

Can We Understand Aging One Gene at a Time?

The evolution of any trait depends on the way in which that trait affects fitness and on the genetic architecture of the trait. The latter component includes the extent to which the focal trait is genetically correlated with other traits that affect fitness, the number of genes that influence the trait, and potential interactions among these genes. With the introduction of high-throughput genomic approaches to the study of aging, researchers are beginning to develop a better understanding of the genetic architecture of aging. At the simplest level, we know that a very large number of genes have the potential to influence life span, and we are just beginning to uncover the much deeper structure that relates the genotype to this particular phenotype. For example, consider the gene regulatory network, which illustrates how genes are connected to one another if they share a common regulatory mechanism. Research on mice has shown that the number of connections among these genes—the overall complexity of the gene regulatory network—declines with age. We are still at a relatively early stage in the study of gene networks and aging. Just how this complex architecture might have influenced, and possibly constrained, the evolution of aging is an important but unanswered question.

See also Chapter III.2.

FURTHER READING

Bonduriansky, R., A. Maklakov, F. Zajitschek, and R. Brooks. 2008. Sexual selection, sexual conflict, and the evolution of ageing and life span. Functional Ecology 22: 443–453.

Cant, M., and R. Johnstone. 2008. Reproductive conflict and the separation of reproductive generations in humans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 105: 5332–5336.

Gurven, M., and H. Kaplan. 2007. Longevity among hunter-gatherers: A cross-cultural examination. Population and Development Review 33: 321–365.

Hamilton, W. D. 1966. The moulding of senescence by natural selection. Journal of Theoretical Biology 12: 12–45. Developed the key mathematical framework for modeling evolution in age-structured populations.

Hawkes, K., J. F. O’Connell, N.G.B. Jones, H. Alvarez, and E. L. Charnov. 1998. Grandmothering, menopause, and the evolution of human life histories. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 95: 1336–1339.

Kenyon, C. J. 2010. The genetics of ageing. Nature 464: 504–512.

Masoro, E. J. 2005. Overview of caloric restriction and ageing. Mechanisms of Ageing and Development 126: 913–922.

Medawar, P. B. 1946. Old age and natural death. Modern Quarterly 2: 30–49. Developed the fundamental evolutionary argument that senescence arises owing to an age-related decline in the strength of selection.

Promislow, D.E.L. 1991. Senescence in natural populations of mammals: A comparative study. Evolution 45: 1869–1887. Established that senescence, measured as age-related increases in mortality rate, is common in natural populations of mammals.

Rose, M. 1984. Laboratory evolution of postponed senescence in Drosophila melanogaster. Evolution 38: 1004–1010. The first artificial selection experiment leading to increased longevity and tests of evolutionary theories of aging.

Sear, R., and R. Mace. 2008. Who keeps children alive? A review of the effects of kin on child survival. Evolution and Human Behavior 29: 1–18.

Williams, G. C. 1957. Pleiotropy, natural selection, and the evolution of senescence. Evolution 11: 398–411. Established the central role for genetic trade-offs in the evolution of senescence. One of the few papers in the field whose ideas have been adopted by molecular biologists.