1 | How your heart works

Your heart is a pump made of muscle which pushes blood through your arteries to all organs of your body. The body needs oxygen and energy to work normally and blood is the delivery system. Blood picks up its oxygen in the lungs and becomes bright red as a result. After it gives up its oxygen, blood takes carbon dioxide and waste products for elimination to the lungs, liver and kidneys in the veins, where it is a now a dark red colour. Your heart muscle needs oxygen and energy and this is obtained from the blood through the coronary arteries. Disease of the coronary arteries is the commonest cause of death and disability in the western world because it stops the heart – the body’s engine – doing its job properly.

ANATOMY OF THE HEART

What is the heart?

The heart is a muscular pump but it is a very sophisticated one. It is made of muscle different from the sort that moves your arms and legs. Heart muscle is particularly strong as it has to cope with the physical and emotional stresses of normal daily life and, of course, it never takes a rest (you hope!). It beats on average 100 000 times every 24 hours and pumps out between 5 and 20 litres of blood (1 litre equals just under 2 pints) every minute, depending on your body’s needs – more when you are being active than when you are resting. Every organ in the body needs oxygen to function normally and efficiently. Fresh blood in the arteries delivers oxygen and energy to your body tissues and then, when it has given up its energy supply, blood carries away in the veins unwanted waste products including carbon dioxide. The heart is the engine that pumps the blood around; normally it is the size of a clenched fist.

Can you tell me what the coronary arteries are?

These are the tubes or vessels that supply your heart muscle with the oxygen and energy that it needs to pump efficiently. The vessels that carry the oxygen round the body are called arteries. Coronary arteries* are tough tubes able to cope with the pressure pumped out by the heart. They are often confused with veins, such as those that we see on the back of the hand or on the legs (usually blue). Veins bring used-up blood back to the heart. They are thinner than arteries and do not work or cope with high pressure in the same way as arteries do.

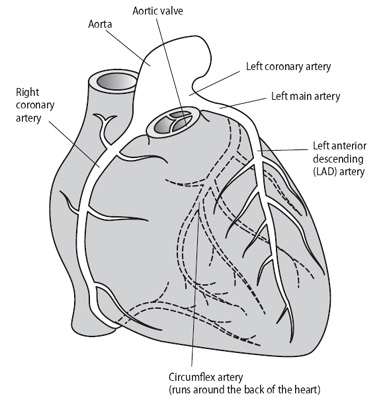

Think of your coronary arteries like the branches of a big tree with a main trunk branching out into smaller and smaller branches and twigs. There are three important coronary arteries with many branches. There is a left coronary artery which divides into two large branches, and a right coronary artery which is usually one big vessel (see Figure 1.1). The coronary arteries arise from the main artery leaving your heart (the aorta), beginning just above the aortic valve (see question below). The most important coronary artery is the left main stem, which controls both branches of the left coronary artery and, as a result, most of the blood supply to your heart muscle.

Figure 1.1 The coronary arteries surround the heart muscle and send branches into the muscle, delivering blood containing oxygen. They start from the aorta just above the aortic valve. Dotted lines indicate the arteries running around the back of the heart.

The coronary arteries start at about 3–4 mm in size (like a thin straw) and as they feed the muscle they divide to reach all the layers of muscle. They run around the outside of the heart, sending their branches inwards.

What happens when things go wrong with the coronary arteries?

The inner lining of your arteries is called the endothelium (pronounced ‘en-doe-thee-li-um’) which is a smooth surface allowing the blood to flow easily. If the endothelium becomes damaged, the tube becomes narrower, and the blood flow becomes turbulent with a chance of clots forming. Think of the artery as a roadway with a new road surface (the endothelium) – now imagine what happens to traffic flow if potholes are allowed to develop and road works cone off one or two lanes or humps are introduced – drive too fast and you will come a cropper! Your endothelium can become damaged by:

•cigarette smoking;

•poorly treated high blood pressure; and

•a high level of cholesterol in your blood, causing localised deposits of fatty material (‘road humps’).

Narrowed coronary arteries can cause:

•angina;

•heart attack: the medical term for this is myocardial (heart muscle) infarction (death of part of the heart muscle) (see Chapter 4);

•irregular heartbeats (some types of palpitations, see Chapter 6); and heart failure (where your muscle becomes weak, see Chapter 5).

What is the aorta?

The aorta is the main artery leaving your heart. It sends blood to your head and then curves over to run down your chest along the spine. It passes along the back of your stomach, and at the top of the legs it divides into the big arteries which send branches down to your feet. Arteries branch off the aorta supplying arms, legs and all the important organs, such as the kidneys and liver.

What are the valves?

The valves control the flow of blood into and out of your heart. They open and shut just like a tap being turned on and off. When working normally, they act as one-way valves. The valves are on the inside of your heart, whereas the coronary arteries are on the outside.

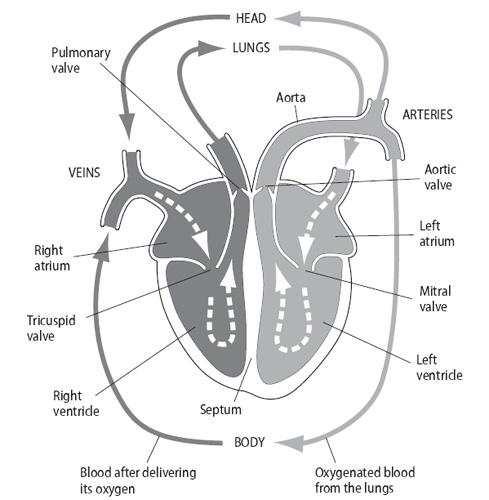

There are four valves – the aortic, mitral, pulmonary and tricuspid. Look at Figure 1.2 and see the sequence of events.

Blood returns to your heart through the veins. It has given up its oxygen to your brain, kidneys and muscle. It comes from the head region in a big vein called the superior (from the top of the body) vena cava, and from the lower body in a big vein called the inferior vena cava. It collects in a chamber called the right atrium.

Blood returns to your heart through the veins. It has given up its oxygen to your brain, kidneys and muscle. It comes from the head region in a big vein called the superior (from the top of the body) vena cava, and from the lower body in a big vein called the inferior vena cava. It collects in a chamber called the right atrium.

The tricuspid valve separates this collecting chamber from the right ventricle, which is part of your muscle pump. (Ventricle is the medical word for pump.) You will notice the use of the word ‘right’ at this stage. This is because your heart is divided into two sides. The right side (on your right) collects used-up blood and passes it to your lungs to pick up oxygen, and the left collects oxygen-rich blood from the lungs and pumps it round the body. The muscle pump on the left is called the left ventricle. This is the most important part of the heart and the one that is most often damaged in a heart attack.

The tricuspid valve separates this collecting chamber from the right ventricle, which is part of your muscle pump. (Ventricle is the medical word for pump.) You will notice the use of the word ‘right’ at this stage. This is because your heart is divided into two sides. The right side (on your right) collects used-up blood and passes it to your lungs to pick up oxygen, and the left collects oxygen-rich blood from the lungs and pumps it round the body. The muscle pump on the left is called the left ventricle. This is the most important part of the heart and the one that is most often damaged in a heart attack.

Figure 1.2 The circulation of blood from the body through the heart to the lungs. From the lungs the blood containing oxygen returns to the heart and circulates to the rest of the body. The atria are the collecting chambers; the ventricles are the muscle pump.

On the left side of your heart, blood leaving the lungs has been collecting in the left atrium. Blood therefore collects in the right atrium and left atrium at the same time. Separating the left atrium from the left ventricle is the mitral valve. The mitral valve opens at the same time as the tricuspid valve so that blood enters the right and left ventricles almost simultaneously.

On the left side of your heart, blood leaving the lungs has been collecting in the left atrium. Blood therefore collects in the right atrium and left atrium at the same time. Separating the left atrium from the left ventricle is the mitral valve. The mitral valve opens at the same time as the tricuspid valve so that blood enters the right and left ventricles almost simultaneously.

Both the right ventricle and left ventricle contract at the same time. As the pressure builds up, the force closes the tricuspid and mitral valves (preventing any leaking backwards) and opens the pulmonary and aortic valves. Blood is ejected through the pulmonary valve to your lungs, and the aortic valve to your body. When the pump has emptied, the pressure drops, the pulmonary and aortic valves close, and the tricuspid and mitral valves open again; the cycle is then repeated.

Both the right ventricle and left ventricle contract at the same time. As the pressure builds up, the force closes the tricuspid and mitral valves (preventing any leaking backwards) and opens the pulmonary and aortic valves. Blood is ejected through the pulmonary valve to your lungs, and the aortic valve to your body. When the pump has emptied, the pressure drops, the pulmonary and aortic valves close, and the tricuspid and mitral valves open again; the cycle is then repeated.

What keeps the right and left heart apart?

The muscle that divides your heart is called the septum. Between the right and left atrium, it is known as the atrial septum, and between the ventricles, the ventricular septum. When a hole occurs in your heart, we call it a defect. If it is between the atria (plural of atrium), it is known as an atrial septal defect (ASD) and if it is between the ventricles, it is a ventricular septal defect (VSD).

HOW YOUR HEART WORKS

When I asked my doctor how my heart works, he said that it would take too long to explain! Can you tell me simply how the normal heart works?

The healthy normal heart is made up of strong muscle and four valves in full working order. It gets its oxygen from blood supplied by the coronary arteries. It is controlled by an electric circuit which tells it when to beat and how fast to beat. The medical term for contraction of your heart pump (that is, when the heart beats, felt as the pulse) is systole, and when the heart relaxes (between the beats or pulse), diastole.

The nurse at our practice runs a clinic to test blood pressures. What is blood pressure exactly and why is it so important?

We all need a blood pressure to keep our blood flowing round our bodies. It is the pressure of the blood in the arteries that is needed for delivering oxygen and food where it is needed and taking away waste products to the kidneys and liver.

Blood pressure has two terms applied to it – systolic and diastolic. The systolic pressure is the top (highest) pressure and is at its maximum following each heartbeat. The bottom (lowest) pressure (diastolic pressure) is the lowest recording between heartbeats when your heart is resting. You might see, for example, 120 (systolic)/80 (diastolic) given as millimetres of mercury and, as mercury’s symbol is Hg, you will see 120/80 mmHg, or 120/80 for short. Mercury is simply a visible liquid used to show the difference between liquid and pressure. When pressure is increased, the mercury is pushed up the scale of the blood pressure machine (the sphygmomanometer; see Measurement of blood pressure in Chapter 2) and readings can be taken in millimetres or mm for short. The mercury sphygmomanometer is being phased out in some countries including the UK and being replaced by electronic machines. This development is regrettable as not all electronic machines are as accurate as the sphygmomanometer (particularly when there is an irregular heart rhythm or very high blood pressure).

I know that the heart beats automatically, but what, if anything, keeps it going?

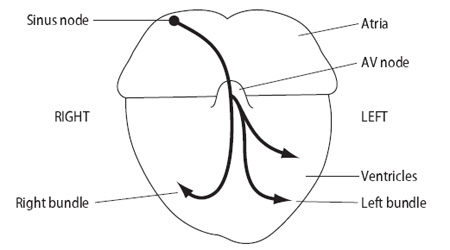

The heart gets its instructions rather like an electric circuit (see Figure 1.3). There is a master switch called the sinus node which speeds up the heart rate and slows it down depending on your body’s needs. If you are feeling emotional, or running, it goes faster; if you are resting or sleeping, it goes slower.

The sinus node sends messages to a junction box (the atrio-ventricular node or AV node) which regulates the electric impulses before allowing them through into the ‘wires’ that supply the left heart muscle (ventricle) known as the left bundle, or the right ventricle known as the right bundle. In this way, if some problem develops so that the control switch races away, the junction box protects your heart by not allowing it to go out of control. Normal impulses start in the sinus node, and travel via the atrioventricular node to the ‘bundles of wires’ that supply the left or right ventricle. The right bundle is single, whilst the left bundle divides into branches (Figure 1.3).

Figure 1.3 The ‘electrics’ of the heart.

WHAT CAN GO WRONG WITH MY HEART?

Various things can go wrong with your heart:

•a problem with the pump: the muscle might become weak (thin) or too thick (hypertrophy);

•damage to your valves: they might become narrow or develop leaks;

•your coronary arteries might become narrowed or blocked; or

•the ‘electrics’ might fail: they might short circuit and go too fast or too slow or alternate between fast and slow.

More than one thing can happen at once and one problem can lead to another. This book will explain that there is plenty that you can do to prevent or deal with the problems that occur.

The heart may also be faulty from birth. This condition is known as congenital (present at birth, by chance) heart disease and can occasionally be inherited (passed on from your parents through your genes).

I am 46 and sometimes feel odd sensations in my chest. Are these to do with my heart? How will I know if I have a heart problem?

The main symptoms people get are:

•chest pain;

•breathlessness;

•palpitations;

•blackouts (less commonly).

If your heart muscle weakens, then you may feel tired or ‘washed out’, feeling as though you have heavy legs or thinking everything is an effort. Of course, there may be other causes for these symptoms and your doctor will be able to sort them out.

What is the commonest heart problem for me to watch out for?

Coronary artery disease (hardening or narrowing of the arteries to the heart) is the most common problem. The next chapters deal with each condition in turn, describing what the problem is and what treatment is available.

What is the pericardium?

The heart is covered by a thin, silky-smooth lining called the pericardium (peri-car-dee-um). It is known as the pericardial sac. Sometimes it becomes inflamed and, instead of being silky, it becomes more like sandpaper and, if the heart rubs against it, it will be painful. Fluid can accumulate in the sac compressing the heart (pericardial effusion) leading to breathlessness and a low blood pressure. If necessary, the fluid can be removed under a local anaesthetic to give instant relief. Inflammation of the pericardium is known as pericarditis.