6 | Palpitations

The medical word for palpitations is arrhythmia (pronounced ‘ay-rith-me-ar’) meaning a change in the beating rhythm of the heart.

All of us feel the heart pounding away when we have to run for a bus, have seen an exciting film or had a fright: this is the normal response to exertion or excitement which causes the adrenaline in the blood to increase and stimulate the heart to beat faster. Being aware of the heartbeat, when there is no obvious explanation, can be alarming and lead to anxiety and panic, all of which makes the situation worse.

What doctors mean by palpitations is an undue awareness of the heartbeat. People see it in less matter-of-fact terms: ‘missed beats’, ‘big beats’, ‘pounding’, ‘fluttering’, ‘as if my heart was going to jump out of my chest’ are some of my patients’ descriptions. Underlying these sensations the questions really bothering people are:

•Am I going to die?

•Will I have a heart attack?

•Will my heart stop beating?

•Will it damage me?

First, it is very rare for any form of palpitations to be dangerous or life-threatening. It is true that they are frightening and the fear can make them worse, but, for most people, all they have to fear is the fear, because palpitations do not usually mean disease.

For the vast majority of people, palpitations are just one of the ways that stresses and strains on the body show themselves, so they tend to be more common in people experiencing stress at home or work, in those with family anxieties and in those who are run down or overworked.

TYPES OF PALPITATIONS

I often feel that my heart has missed a beat. Is this serious?

Missed beats are a common sort of palpitation and are invariably harmless. They can be brought on by too much caffeine, for example in tea, coffee, Coca-Cola or chocolate. Of these, coffee is by far the most important source of caffeine. Sometimes alcohol is the cause. If there is another disease present, missed beats may well be important, for example after a heart attack (see your doctor if you get these), but in 9 out of 10 people the heart is sound.

I drink rather a lot of coffee. I have heard that caffeine is bad for the heart and I must admit that sometimes I feel that my heart has missed a beat. Am I about to have a heart attack?

The control of the heart is like an electric circuit with a master switch. Occasionally, short circuits cause extra beats but the master switch is always in charge, even though it lets one or two extra beats escape. You may feel this more when your heart is slow, or when you are resting or just before going to sleep. It can also occur when the heart has been stimulated by caffeine, alcohol, stress, or as a side effect of medication, such as inhalers for asthma. The extra beat arrives early and there is then a pause (the missed beat) whilst the next normal beat comes along. The extra beat may not be felt (‘as if the heart skips a beat’) but, after the pause, the pump of the heart will be fuller than usual, so the next normal beat will feel like a big beat – a ‘kick’ or a ‘thump’. A beat hasn’t really been missed, it just feels like it, and the big beat is the heart making up for the one that came a bit early. This is not dangerous – the heart is compensating for the early beat.

When I was at work the other day, I suddenly felt my heart was working overtime – I hadn’t even been rushing up the stairs! What was happening?

Rapid palpitations may be normal, such as when you are running or excited, but sometimes they occur abruptly (‘out of the blue’) and can cause mainly fear, but also a sweaty feeling, light-headedness, breathlessness or, rarely, pain. Just as the cause of extra beats can be thought of as short circuits, so these palpitations are best thought of as caused by a sensitive area in the wiring of your heart. Again, it may be responding to stress, cigarettes, caffeine or alcohol. Remember that the wiring is only part of the building of the heart, a problem here or there is not going to affect the structure. However, palpitations which lead to chest pain, light-headedness or blackouts need a thorough medical check, so go to your doctor if you get these symptoms. Some people – a small number – have persistent troublesome rapid palpitations which carry on even when you have stopped drinking caffeine or alcohol or when you are no longer stressed. The cause can invariably be identified and treated and is rarely more than an awkward nuisance. Although there may be no major problem with the heart, there is no point in feeling ill if treatment can help you.

I’ve been very worried when I had two attacks of rapid heartbeats recently. Are there any types of palpitations that are dangerous?

Some very rare palpitations are so fast that a blackout occurs. If they occur because your heart muscle is not working very well (ventricular tachycardia – tachycardia just means rapid heartbeat), you will need medication to make them stop as they can be fatal. A common medication used is amiodarone. Your doctor will explain what is happening and it will be very important to follow his advice. You will need close hospital supervision. A defibrillator may also be advised (see p. 191). I must emphasise that this is rare.

I am in my twenties and am getting rapid heartbeats every so often. I work in the type of job where results are all important. My husband has just lost his job as well, so sometimes I feel really stressed. Should I go to the doctor?

Rapid palpitations are a bit more of a problem because they are more

scary. Again, younger people can be under stress, and the heart is behaving in an exaggerated variation of normal, as if you are running all the time, owing to higher adrenaline levels in the blood. A visit to your doctor and an ECG are necessary if symptoms are a problem (dizziness, breathlessness). The doctor will test you for various things such as anaemia, an overactive thyroid gland; he may also check to see whether you are pregnant, because pregnancy makes the heart beat faster in order to feed the baby. Very rarely, the ECG shows evidence of a specific ‘extra wire’ in the heart, which conducts beats much faster than the usual circuit; you will need to go to hospital in this case.

SELF-HELP

I occasionally get palpitations. Now that I am approaching 50 are they going to get worse?

The first thing to do is not to panic. Your doctor will have already told you about not smoking and not drinking excess caffeine or alcohol. As you get older it is a good idea also to try and keep your weight down. Make sure that you:

•take regularly any tablets you have been prescribed;

•attend your doctor for regular checks;

•report any change in how you feel.

I have just had three attacks of palpitations in a week, which made me very worried. By the time I got to see my doctor, they had gone away. What should I do if I get another attack?

When you experience palpitations, take deep breaths and try to relax. If you feel faint, sit down or lie down with your feet up. Try doing a deep cough. If the palpitations are missed beats or rapid beats, and you feel unwell or know that you have a heart condition, let your doctor know. If you are otherwise well and just afraid, ask yourself whether any of these factors might have caused it:

•stress;

•caffeine;

•workload;

•alcohol;

•smoking;

•family anxiety or grief;

•problems at work;

•no recent holiday;

•being generally run-down and anxious.

Try to help yourself by learning to relax more and avoid stimulants to the heart.

After you have tried the first-line principles of not panicking, taking deep breaths etc., try the following procedures, designed to stimulate a nerve called the vagus nerve which can switch rapid palpitations off. These include:

•drinking ice-cold liquid or eating ice-cream, or putting your hand in a bucket of cold water;

•coughing deeply;

•blowing your nose with it pinched, as if trying to make your ears pop, for 20 seconds;

•pressing the right artery in the neck (this is known as carotid sinus massage (CSM) and needs medical instruction);

Do not press your eyes as this can be dangerous.

If rapid palpitations are a more frequent problem or cause distressing symptoms, then medication will be needed to suppress them (see the section Treatment below). Many types are available and more than one may be necessary. Just because you may need more than one medication does not mean that palpitations are dangerous, just awkward. Treatment is a bit hit and miss, so be patient and ask your doctor about any side effects.

I have heart disease and am finding that I occasionally get attacks of palpitations. Is this serious?

Missed beats in people with heart disease are not usually much to worry about but a check-up is a good idea. Those people on water pills (diuretics – see the question on diuretics in the section Risks of high blood pressure in Chapter 2), or blood pressure pills (see Chapter 2) may have a low potassium level. Although this is not a common cause of missed beats, the problem can easily be treated, so it should be considered if palpitations arise for no obvious reason when these medications are being taken. You should ask your doctor if your palpitations seem to arise for no apparent reason. Fresh fruit contains lots of potassium as does fruit juice, so the treatment is pleasant; however, it is best to avoid grapefruit juice as this affects the action of some medications.

There was something in the media about a problem with grapefruit juice interacting in some way with medications. Should I avoid the fruit or juice completely?

It is the concentrated juice that is a problem. The juice leaves the body via the liver where it shares the same breakdown system as some medications. It competes with the medications and stops them from being broken down (metabolised) so they may stay around much longer than normal and become more powerful.

I am in my sixties and have developed rapid heartbeats in the last few weeks. I like to drink with friends most evenings. Do you think I am drinking too much?

Rapid palpitations in older people may be caused by atrial fibrillation (see below). This is an irregular heartbeat caused by wear and tear but it is also more common in people with high blood pressure and those who drink a lot of alcohol. Sometimes it can be due to the coronary arteries becoming narrowed or to a thyroid problem (thyrotoxicosis).

If the rapid palpitations are other than normal speeding up (sinus tachycardia), your doctor may decide to treat you and base the treatment on how you feel. For instance, if your heart is sound and only one attack a month happens, then the main thing for you to do will be to cut down on your drinking which acts as a stimulant. Your doctor may treat you for high blood pressure.

I have tried all sorts of self-help methods but I keep getting palpitation attacks; when should I see the doctor?

Palpitations are common, mostly harmless but invariably worrying. Don’t be afraid, try to understand the reasons – have a good look at how you are living and seek medical advice if there is not an obvious cause or the attacks just won’t go away. If palpitations lead to symptoms of chest pain, light-headedness or blackouts, always get your doctor to check you over.

TESTS

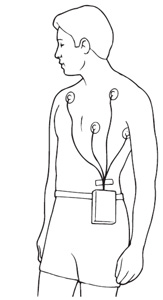

I have been to the doctor because I was so worried about these rapid heartbeats that occurred. He has given me a little machine to record any attacks that I get in future. Can you tell me more about this please?

Because palpitations don’t usually occur when you visit the doctor, a 24-hour ECG (see Chapter 2) is often used. This is like a ‘Walkman’ but it records your heartbeats instead of playing music. The digital card is replayed through a computer and we see the results in a matter of minutes. It does not record any sound so you need not worry that Big Brother is listening in!

You can use this machine at home so that the doctors can watch what your heart is doing during normal daily life. You will be asked to keep a diary and the recording will be checked for times when you felt palpitations or became dizzy.

Four electrodes are attached to your chest and fastened with wires to the recorder which is worn on a belt round your waist (see Figure 6.1). The monitor is quiet and you should not be inconvenienced.

Whilst using the recorder, act normally and try to bring on the symptoms you have been having. You are not allowed to have a bath or shower without a special cover being used. You will be asked to return the recorder the next day so that we can analyse the recording to see if you need any special treatment. Sometimes we do several recordings over 2–5 days.

Figure 6.1 A mobile ECG recorder known as a Holter,

about the size of a ‘Walkman’.a

I think the machine that I am to be given is called an event recorder. Is this different to the ‘Walkman’-type recorder?

This is a small machine which you put on your chest to record a palpitation as it happens. It is about the size of a mobile phone and can be carried easily. The palpitation is then decoded over the telephone or in the technicians’ department, and printed out on an ECG. It is useful when attacks are infrequent but noticeable, and they have to be long enough for you to take action to record them. You will be shown how to use it by the technician at the outpatient department when you collect it.

There are now several recorders which you can activate yourself – some are very small so they are easy to live with. They store information which can then be downloaded and analysed on a computer. They are particularly useful when attacks are infrequent, and where a 24-hour ECG may miss them. Sometimes a device called a Reveal is inserted under the skin, under local anaesthetic. This is about the size of a PP3 battery and can be used to record infrequent episodes, being kept in place for up to a year.

An appointment has been made for me to go to hospital for electrophysiological (EPS) tests. What are these?

These are tests which have to be done in hospital, not at home. Pacemaker catheters (usually four) are passed via a vein at the top of your leg to the heart and the source of palpitations pinpointed and analysed with complex computers. It usually takes up to an hour but can take several hours; it generally needs to be done with X-ray guidance in the catheter laboratory. The only pain you should feel is the local anaesthetic in the groin, but as the doctor moves the catheters you may become aware of your palpitations as the doctor identifies them and tries to get them to occur again. It is usually done as a day case, or one night in hospital may be advised.

TREATMENT

I have a very stressful job and find that I get really nervous.

My heart seems to miss a beat when I am stressed or anxious.

Is there anything that can help me?

Missed beats usually respond to self-help, perhaps with a doctor’s reassurance which might include taking an ECG at rest and recording the heartbeat for 24 hours (24-hour ECG see the section Tests above). A lot of people, who get palpitations like this, are young and under stress, and are helped by beta-blockers which block the stimulation of adrenaline and caffeine to the heart (see the question on beta-blockers in the section Risks of high blood pressure in Chapter 2). These can be used for a month while you try and change your lifestyle where possible, and then as required, for instance before a stressful meeting. Try not to drink too much coffee at meetings and change to decaffeinated-type drinks.

I am going for tests at the hospital next week for palpitations. Will I be offered any medication to treat irregular heartbeats?

It will depend on what type of palpitations that you are found to have. There are a large number of medications used to slow down fast heartbeats and to suppress extra beats.

•Digoxin is most often used to control atrial fibrillation (see below). Doses vary according to how old you are and how good your kidneys are. Your body gets rid of digoxin through your kidneys so, if the kidney function is not as good as it should be, digoxin will build up in the blood. Commonest side effects are loss of appetite, nausea and vomiting. Your doctor may check the level of digoxin in the blood 6 hours after you have taken it to make sure it is not too high or too low. If you get side effects, these will probably disappear if the dose is reduced. (See the section Treatment in Chapter 5.)

•Beta-blockers are also used for controlling palpitations. They also help angina, heart failure and high blood pressure; they are especially useful if you have more than one of these conditions. (See under Treatment in the Risks of high blood pressure section in Chapter 2.)

•The calcium antagonists, verapamil and diltiazem, are alternatives to beta-blockers for palpitations and, like beta-blockers, can be combined with digoxin.

Other more specific medications can be used to suppress extra beats and these include flecainide and amiodarone. These are powerful drugs, used if the simpler medications such as beta-blockers are not proving effective.

•Flecainide is effective in 30 minutes, so is often used as and when the attacks have to be stopped immediately. It is a very effective medication when taken on a regular daily basis by people whose lives are made a misery by troublesome palpitations, but it is unsafe to use it at all if you have heart failure or soon after a heart attack. It can cause nausea, dizziness, and unsteady feelings. It can be used just to stop an attack, known as ‘pill in the pocket’ so you carry it and use it when needed.

•Amiodarone is a life-saving medication for some but, because of its side effects, it is not normally used as a long-term treatment unless there is no alternative. It is very effective in the management of atrial fibrillation (see below), extra beats and dangerous palpitations, and it can be used when you have heart failure and after a heart attack. It takes some time to start working and can take a long time to leave the body. Side effects include sensitivity to sunlight, skin reactions, lung problems and disturbances of the thyroid gland and liver. You will need regular supervision so that the doctor can check for side effects. Amiodarone increases the action of warfarin so extra care is needed by your doctor to monitor the blood-thinning effects of warfarin, if you are taking this.

•Other drugs less frequently used and mainly alternatives to flecainide include disopyramide, propafenone and mexiletene. All are effective drugs but side effects can be a problem. If you are prescribed any of these drugs, always read the package label and discuss the potential benefits and side effects with your doctor.

ATRIAL FIBRILLATION

I have just had a test for irregular heartbeats and been told that I have atrial fibrillation. What is this?

Atrial fibrillation is a very specific irregular heartbeat. The heart works like an electric circuit. There is a master switch at the top of the heart in one of the upper chambers, the atria (see Chapter 1). This switch regulates the speed of the heartbeat and normally controls how and when the heart beats, by sending messages to the muscle pump (ventricle) which is located below the atria.

When the atria fibrillate, this means that the master switch is no longer in charge, discipline is gone and chaos reigns. Atrial fibrillation occurs at around 600 beats per minute (bpm) and the top chamber (atrium) resembles a wriggling bag of worms. The heart muscle (ventricle) could therefore, in theory, be bombarded with 600 bpm and would cease to work. Fortunately below the master switch there is a junction box (called the AV node) which prevents all 600 beats getting through to the heart muscle, so the heart beats at anything up to about 180 bpm, at the rate the junction box will allow. Medication is used to further block beats through this junction box so that the rate will settle to a more normal and pleasant 70–80 bpm. Doctors refer to the fibrillation being ‘poorly controlled’ or ‘well controlled’, depending on the rate achieved after medication. Good control is when the heart beats at less than 90–100 beats per minute.

Atrial fibrillation (a fluttering feeling) is quite common and, for most people who get it, unavoidable. It responds to treatment and, although the heart is beating less efficiently than a normal regular heart rhythm, it can be improved, so that for most people it is hardly noticed. For a small number of people, it can be difficult to control and they will need to be looked after carefully.

I have been diagnosed as having atrial fibrillation. What could have caused this?

It occurs in many conditions and, in a small number of people, for no obvious reason: so-called ‘lone fibrillation’. It may be a part of getting older (wear and tear to the heart) but it can be a consequence of:

•mitral valve disease;

•high blood pressure;

•coronary heart disease;

•heart failure;

•an overactive thyroid gland.

Alcohol can cause atrial fibrillation in alcoholics but can also induce it in quite normal people when they have been celebrating a little too much, particularly in women, who are more sensitive to alcohol.

How will I know that the palpitations are due to atrial fibrillation?

Atrial fibrillation may come on suddenly and fast. It is usually felt

as palpitations of a rapid sort, with the heart ‘beating all over the place’. It can bring on chest pain but usually makes people breathless. Naturally, it can be frightening, and may leave a feeling of light-headedness if it is so fast that the blood pressure drops a little.

Fibrillation in some people with heart failure can come and go and, as fibrillation is less efficient than normal rhythm (‘sinus rhythm’), this can lead to periods of fatigue and breathlessness. For people who have atrial fibrillation regularly, it is important to keep the rate under control, or the efficiency of the heart and general well-being will be impaired.

My husband has just been told that he has atrial fibrillation. Is this dangerous and can anything be done to help him?

The short answer is: occasionally yes, it can be dangerous, but usually it is not. If he is given modern treatment, the efficiency of his heart will be improved, so that he will hardly notice that he has atrial fibrillation. If it comes on suddenly, he may become very breathless, and he may have to go into hospital. If he has an underlying heart problem, atrial fibrillation can cause little clots to form, and he will need blood thinning treatment to stop this, in order to reduce any chance of a stroke.

Tests for atrial fibrillation

My doctor has told me that I have will have to undergo some tests to check to see whether I have atrial fibrillation. What will this involve?

There are several diagnostic tests.

•Your heart may be checked by a standard resting ECG or one taken over 24 hours.

•A chest X-ray may be taken.

•A scan (echocardiogram) can be performed to check the heart valves and muscle pump (see the section Tests in Chapter 3).

•Blood may be taken for routine checks and to make sure that your thyroid gland is all right.

In some cases, atrial fibrillation may be part of an illness which needs surgery, such as mitral valve replacement (see Chapter 7), and X-rays of the heart (cardiac catheterisation: see Chapter 3) will be performed before you have to undergo surgery.

You may undergo electrophysiological tests (EPS) studies (see earlier question above) if you have rapid palpitations which cannot be caught on tape, or if you have potentially dangerous palpitations and have palpitations that refuse to respond to safe and normally effective tablets. The reason for these studies is the technique of cardiac ablation (see the section Treatment of atrial fibrillation below).

Treatment of atrial fibrillation

What sort of treatment is there available for me now that I have been diagnosed with atrial fibrillation? Can I just be treated with medication?

Following your tests and depending on the severity of atrial fibrillation, you will usually be prescribed medication. People whose atrial fibrillation has only just started may benefit from electric shock treatment.

If you have heart problems and the fibrillation is considered part of your illness, you will be treated with medication to keep your heart rate as steady as possible. To some extent the medication used will depend on the cause.

•If you have heart failure, you may be prescribed digoxin.

•If you have high blood pressure but no muscle pump damage, you may be prescribed a beta-blocker, verapamil or diltiazam.

•Once heart failure is controlled a beta-blocker may be added to digoxin or replace it.

Most people are on a beta-blocker or verapamil (but not if they have heart failure), but some are on more than one medication to get more benefit. It is vital that you know what each type is for (write it down when you are discussing it with your doctor) because, if you stop taking one medication, your heart may race away again. You will help yourself by reducing caffeine, alcohol, stopping smoking and reducing weight.

What medication will I be offered to treat my atrial fibrillation?

Digoxin, beta-blockers (such as atenolol, bisoprolol, propranolol, metoprolol), calcium antagonists (such as verapamil, diltiazem), amiodarone, flecainide, propafenone, disopyramide, quinidine, and combinations of the above. Warfarin is used to thin your blood. See the section Medication in Chapter 5.

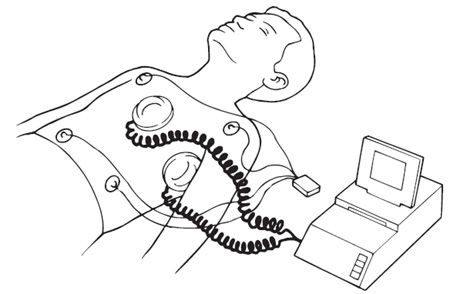

I have been told that I am going to have shock treatment for atrial fibrillation. What will this involve and is it dangerous?

If the heart is all right and it appears to have been a temporary upset, you may undergo shock treatment to get the heart back to its regular rhythm.

Figure 6.2 Electric shock treatment (cardioversion). Often the pad

by the arm is placed on the back instead.

Electric shock treatment involves passing a high voltage electric current through your heart and is known as cardioversion or a DC shock. It is used to correct rhythm disturbance, such as atrial fibrillation or rapid rates from an abnormal origin, and will usually be performed if the fibrillation has been picked up early enough. The machine used is a defibrillator.

Under a brief general anaesthetic, an electric current is passed via a paddle on the top of your chest to a paddle on the left side or back (see Figure 6.2). It takes less than five minutes. The abnormal palpitation is halted at its source, and this allows the normal electrics to take over. It is successful 9 out of 10 times. Usually the patient receives warfarin for at least 4 weeks beforehand and a month afterwards to prevent the formation and dislodging of clots. If cardioversion is performed at short notice, your blood is thinned with heparin given through a vein. Cardioversion is usually done as a day-case procedure (in and out the same day) and you will notice how much better your heart behaves almost immediately.

There is no need to worry about electric shock treatment; it is safe and effective provided that all the precautions are taken – making sure of the diagnosis and use of warfarin.

A new technique involving a shock inside the heart is being used more frequently, as it appears to be more successful. A special tube is passed to the heart via the vein at the top of the leg under local anaesthetic. Once it is in place under heavy sedation or a brief general anaesthetic, a shock is delivered almost directly to the atrium, where the problem arises. The results are very encouraging, and you may be offered this as an alternative to the external shock treatment.

My cardiologist has mentioned cardiac ablation. What will this involve? Is it safe?

First, an electrophysiology study (EPS) is performed by a cardiologist in hospital (see the section Tests above). Once the source of the palpitation has been identified, and if the cardiologist considers you to be a suitable case, a special electrical pacemaker catheter can be placed at the source of the palpitations and radio frequency waves used to ablate them (doctors often say ‘zap’!). When the cardiologist is satisfied that all is well, all catheters are removed; pressure is applied to the vein at the top of the leg for 15 minutes or so, and after two to four hours’ bed rest, you will be allowed up and about; you will usually go home the next day. An ECG will be taken to check the rhythm and a 24-hour ECG may be organised to judge the effectiveness of the procedure when you are out of hospital.

Cardiac ablation can be a lengthy procedure as the catheter has to be placed very accurately. It is usually successful and abolishes the palpitations, removing or reducing the need for medication. Very rarely, the normal electrics are damaged because the abnormal electrics are very close by and they can get caught by the ablation and a pacemaker is then needed.

The procedure can remove young people from a lifetime of dependence on medication; women can become pregnant without fear of any medication damaging the baby. Also, if medication is successful but gives side effects, cardiac ablation is an effective alternative. Because ablation is a very individual procedure, it is important to discuss fully with your cardiologist the potential risks and the chances of benefit for you – not someone in general, but you specifically.

OTHER ABNORMAL HEARTBEATS

Two or three of my friends now have a pacemaker. Although I have ‘funny’ heartbeats, I have not been offered one. When are they used?

Pacemakers will be used when the heart goes too slow. The heart can alternate between fast and slow; a pacemaker will still be needed as medication given to stop the heart beating too fast will make the slowing worse. A slow heart rate is known as a bradycardia. When the electrics of the heart fail to connect up, this is called heart block.

There seem to be a lot of different methods of helping abnormal heartbeats. Why was I offered electric shock treatment and not a pacemaker?

Shock treatment corrects a rapid abnormal heartbeat whereas a pacemaker corrects a slow abnormal heartbeat. If you have a mixture of fast and slow beats, you may need both treatments. If your heart occasionally speeds up, medication may be needed in addition to a pacemaker, to stop rapid palpitations or keep them under control.

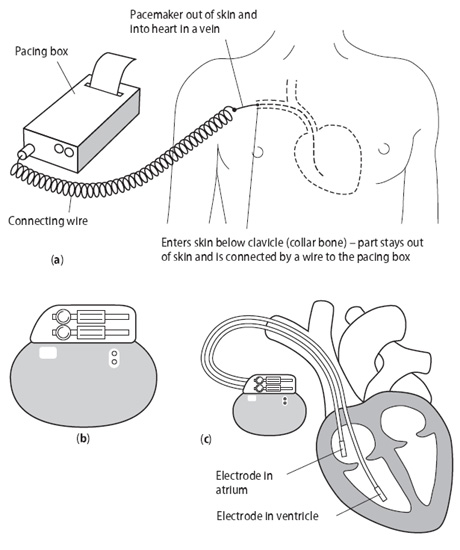

I am going to have a pacemaker fitted next month – are there different types?

There are two types that your cardiologist will choose from, depending on which is most suitable for your problem, both shown in Figure 6.3.

•A temporary pacemaker (Figure 6.3a) will be needed sometimes after a heart attack if the electrics are bruised and a block occurs – it is fitted in an emergency.

•If the electrics are permanently slower, or malfunctioning consistently, you will need a permanent pacemaker (Figures 6.3b, c). If you don’t have this problem corrected, your body will lack oxygen and food; you will be tired and lethargic, and risk falling down from a blackout (see questions below). These pacemakers are small and very reliable computers which can identify your normal heartbeats and the need to fill any gaps. You may need a permanent system if your heart does not recover when the temporary system is switched off. You may be advised that one is needed when you are seen in the outpatient clinic, because your heart has been found to go too slowly at times.

I am rather nervous about having a pacemaker fitted. What will it involve?

For a permanent system, you will usually stay one night in hospital, although your hospital may undertake to fit the pacemaker as a day case. You will be told how long your stay is likely to be so that you can prepare a night bag if necessary.

For a temporary pacemaker, a wire is passed via a vein in the arm, neck or below your collarbone (most often) to the right ventricle (pumping chamber) and connected to a box at the bedside or attached to your arm (see Figure 6.3a). It is fitted under local anaesthesia. This senses normal beats and fills any gaps with pacemaker beats. When the electrics recover, it is removed by simply pulling the wire out; this is not painful.

For a permanent pacemaker, you will be given a local anaesthetic and sedation; then one or two wires are passed to your heart via a vein under the collarbone (the subclavian vein), or the one running on the inside of your shoulder (cephalic vein). The pacemaker box is attached and buried under the skin. The wires are positioned with X-ray guidance and the procedure takes about one hour. A small cut is needed on the front of your chest below the collarbone and stitches will be used to close it up at the end of the procedure. Stitches that do not dissolve will be removed 7 to 10 days later, usually by the nurse at your doctor’s surgery. Before you leave hospital, a chest X-ray will check that all is well, and the technician will use a computer placed on the skin over the pacemaker box to make sure that it is working properly.

Before my heart started to play up, I was very active. Will I be able to go back to that sort of activity when I have had my pacemaker inserted?

The short answer is yes. A pacemaker is all about correcting a problem and allowing you to lead a normal active life. You will need the stitches out a week after the insertion and you will have been given a course of antibiotics to protect you from infection. You will not be allowed to drive a car for a week, and you must inform the DVLA and your car insurance company. You may be able to hold a Group II licence if there are no other disqualifying conditions, but you will need to wait 6 weeks. Group I licences are for motorcyclists, car and light goods vehicle drivers; group II relates to drivers of vehicles in excess of 3.5 metric tonnes laden weight, and bus or coach drivers. Group II standards apply to emergency police, firemen, ambulance drivers and taxi drivers.

Figure 6.3 Pacemakers.

(a) Temporary pacemaker;

(b) Permanent pacemaker;

(c) Permanent pacemaker in position.

You will be given a check of your pacemaker function at 1 month and then once a year. This yearly check is to monitor its battery life. If the batteries begin to run down (many last over 10 years), the box will be unplugged from the wires and a new box implanted under sedation and local anaesthetic.

You will be given a card to carry with you at all times. You will need to tell airport security as you will set off the alarms. Modern household microwaves and electricity do not affect it but mobile phones may do if placed close to the box (about 10 cm). Avoid placing them in shirt or jacket pockets on the pacemaker side. You will not be able to have an magnetic resonance imaging scan.

Life should not be restricted just because of a pacemaker.

Can pacemakers be troublesome?

Not usually, but occasionally they can cause soreness and, very rarely, become infected (it will then need to be removed). They may need adjusting from time to time – this is done via a computer placed over the box on the outside of the skin. Some early pacemakers developed faults and needed replacing. The wires in the heart do not usually displace after the first 24–48 hours. You can damage the wire or box in a heavy fall or accident, and it should be checked if this happens. Contact sports such as soccer or rugby should be avoided. Most people have no problems at all but, if you do have concerns, contact your pacemaker clinic for advice.

When I went to see the cardiologist, he was very frank with me and said that the type of heart rhythm that I had was rather dangerous. He wants to insert an implantable defibrillator. Is this a type of pacemaker?

The official name for this is an automatic implantable cardioverter defibrillator or AICD and, yes, it also acts as a pacemaker.

Some people have a very dangerous rhythm tendency which could cause them to drop dead suddenly. For people like you pacemaker wires are passed into the heart, under general or local anaesthetic, through the top of your chest wall through a big vein which runs under your collarbone (subclavian). The defibrillator box is attached and then buried under the skin of your chest wall; sometimes it is placed in the abdomen in your stomach area. It recognises normal beats but, if abnormal dangerous beats occur, it shocks your heart immediately. This may be felt as a slight thump. The machine needs checking at regular intervals to make sure that the battery life is satisfactory and, because it is a type of computer, it can also keep a check on how often it has been used. It is an expensive option but a definite lifesaver.

The British Heart Foundation book Implantable cardioverter defibrillators is a superb guide for patient and family (see Appendix 3).

A friend of mine has a defibrillator for atrial fibrillation – is this a new treatment?

Atrial defibrillators are rarely used. They are used in people who

get very occasional attacks of atrial fibrillation – say, two or three a year. They are inserted under local anaesthetic similar to a pacemaker, and provide a shock to correct the atrial fibrillation when an attack occurs.

BLACKOUTS

My wife has suffered from blackouts recently. Can you tell me what these are and what causes them?

A blackout is a sudden loss of consciousness; this causes her to fall

to the floor. If your wife’s heart suddenly goes too fast or too slow, her blood pressure falls and she will collapse. It happens very suddenly; her colour drains away (‘as white as a sheet’), but recovery is usually quick. You will probably notice that your wife’s skin becomes flushed. Often she will recover so quickly that she may think that she has tripped up and ‘wonder what the fuss was about’.

Sometimes it may be a faint, but blackouts can also be caused by lack of blood (anaemia), and problems with the nervous system (the brain), and a low blood sugar, for example in epilepsy or lack of blood from narrowed arteries. Blackouts from a heart problem tend to be sudden in onset with a quick recovery (5–10 minutes); blackouts not caused by a heart problem may be sudden in onset but recovery is slow, sometimes over several hours.

My wife has been ignoring these blackouts because they don’t happen too often. Should I get her to go to the doctor and have them investigated?

Yes, or she could fall and injure herself. Your wife may need a pacemaker or medication to keep them under control.

How does a faint differ from a blackout?

Before a faint there is usually a warning. You may become pale and sweaty, yawn a lot and have a buzzing in your ears. Faints often occur in a warm, close environment or when you have been standing for a long time in heat or a queue. A bad coughing bout can bring on a faint (cough syncope) and it can occur if men (and rarely women) get up suddenly at night to pass urine (micturition syncope). Syncope (pronounced ‘sin-co-pee’) is the medical word for a sudden loss of consciousness.

If my wife feels faint, what should I do to help?

Help her to lie down flat and raise her legs. As she recovers, gradually get her into the sitting position and then let her stand up. Make sure she is steady on her feet before she walks again.