3 | Angina

Each year in the UK around 320 000 people visit their doctor for angina. Over six million people in America and two million in the UK are affected. Angina (pronounced ‘ann-jy-na’) is a symptom of a problem, not a disease in itself. It is usually caused by narrowing of the coronary arteries by atheroma (see introduction to Chapter 2). It can also be caused by a high blood pressure (see the section Risks of high blood pressure in Chapter 2), disease of the aortic valve (see Chapter 7), severe anaemia, and rapid palpitations (see Chapter 6) or a mixture of conditions. Far and away the commonest cause is coronary artery disease (see Chapter 2).

The coronary arteries supply oxygen to the heart and the heart gets this supply between its beats, when it is refuelling itself. This means that the faster your heart beats, the less oxygen there is for the heart itself. If your arteries are narrowed, the flow is restricted. The balance will function well enough when you are not doing anything but, when your heart speeds up, there will come a point when the narrow arteries restrict the supply of oxygen to your heart muscle and pain develops. This is when angina is most often felt, as a chest pain, when you are active or when you are worked up about something, because the demands of your heart for oxygen are not being met by the supply of oxygenated blood to your heart muscle.

SYMPTOMS

My husband has got angina. He is obviously in pain but cannot describe it easily. What does it feel like?

The pain usually begins behind the breast bone. It is often felt

as a tightness or a squeezing sensation; your husband probably describes it best by clenching his fist in front of his chest (see Figure 3.1).

The pain of angina can be regarded as a built-in warning device and tells him that the heart has reached its maximum workload. The onset of pain or discomfort indicates that he should slow down or stop any exertion. Alternatively, if emotion (such as anger) has lead to this, then he should relax and remove himself from the situation.

You cannot usually point to where angina pain is felt; it is more widespread and felt across the chest. It is brought on usually by effort, so it will build up if that effort is continued. When it begins, it is often quite mild – more of an ache – so it is easily confused with indigestion. Angina pain may spread (radiate) to the throat or neck, the jaw (like toothache), to the left or right arm or both, and sometimes to the back or stomach. It usually goes down the inside of the arm, in contrast to muscle pain which runs over the shoulder and down the outside of the arm. Rarely, angina occurs in one of these places without being in the chest; for example, a person gets pain in the left arm on effort which is relieved by resting.

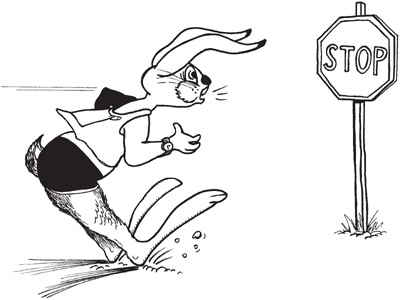

Figure 3.1 Hand movements and chest pain. Heart pain is usually described with the flat of the hand (a) or a clenched fist (b). Heart pain

is almost never localised or pointed to (c).

Can my husband’s chest pain be from causes other than heart disease?

There are many other causes of chest pain and here are some pointers to stop you worrying unnecessarily.

•Joint or muscle pain This is often worse when someone is changing position. This sort of pain can be reproduced by pressing on the ribs or breastbone.

•Lung disorders This pain is aggravated when you take a deep breath.

•Stomach problems Indigestion after a meal or on bending with an acid taste in your mouth (acid reflux).

•Gallbladder problems Colicky pain after a fatty meal may suggest gallstones.

•Stress, anxiety or overbreathing.

Nobody should have chest pain that is a mystery. Do not assume your husband has angina but also do not let him ignore the pain. Get him to ask his doctor’s advice. Table 3.1 shows the main differences in signs between heart and not-heart pain.

What is the difference between angina and a heart attack?

Angina is the result of a temporary shortage of oxygen available to

the heart muscle, usually caused by exercise or strong feelings. Angina pain usually passes off when you stop activity, or very shortly after taking a ‘nitrate’ tablet (see the section Treatment below). Angina results from narrowed coronary arteries.

A heart attack is different (see Chapter 4). The pain build-up is more severe, lasts longer and does not decrease when you stop any activity. It may be modified if you take nitrate tablets but is not relieved. You will often find that you sweat and you may feel sick. A heart attack is caused by an artery blocking off, usually when a clot forms on a narrowed area.

Table 3.1 Chest pain characteristics

Typical angina pain |

Not heart pain |

Tightness |

Sharp (not severe) |

Pressure |

Knife-like |

Weight on the chest |

Stabbing |

Heaviness |

‘Like a stitch’ |

Constriction – like a band |

Shooting |

Ache |

Localised |

Dull |

Positional |

Burning |

Reproduced by pressure |

Crushing |

Located elsewhere than mid-chest |

Retrosternal (behind breast bone) |

Not exertional |

Precipitated by exercise and/or emotion |

Relieved by antacids |

Relieved promptly by GTN* |

*GTN, glyceryl trinitrate (see the section Medication later in this chapter)

I have been diagnosed as having unstable angina. What is this?

Angina that occurs more frequently with ever-decreasing activity

is known as unstable angina. For example, if it is worse when you walk 22 metres (25 yards) rather than 0.8 km (half a mile). It may also occur at minimal activity or at rest, or wake you from sleep.

You should see your doctor urgently if:

•you are getting angina for the first time;

•the pain is getting worse and occurring more frequently;

•the pain happens when you are not doing anything.

I am on medicine for angina and I still often get pains. If I get an attack of angina, it is difficult to know when I should bother the doctor. What should I do?

There are various instances when this would be advisable.

•If you have been newly diagnosed with angina and pain occurs when you are walking less than 22 metres (25 yards) on the flat.

•If it occurs at rest (usually in bed).

•If the pain lasts longer than 20 minutes in spite of nitrates (see below).

•If you are very breathless.

•If you feel faint or light-headed with the pain.

•If the pain comes on while you are convalescing from a recent heart attack.

When should I dial 999 rather than just call a doctor?

If the pain lasts longer than 20 minutes, in spite of nitrate tablets or spray, then dial 999. Tell them that you need an ambulance and have a ‘possible heart attack’. Try another nitrate tablet or spray if the pain continues; crunch a 300 mg tablet of aspirin and then swallow it. Aspirin thins the blood and can help prevent unstable angina developing into a heart attack as well as limiting the damage a heart attack can do.

I have angina, but I want to live an active life. Is there any activity that is likely to bring my angina on?

Any form of exercise can bring angina on – climbing stairs,

carrying shopping, walking up an incline and rushing. Angina may be more of a problem in cold or windy weather, or when you are carrying something heavy or going for a walk too soon after a large meal. It also occurs when you are under emotional stress, especially anger. It can vary a lot from day to day, but if it is becoming more frequent and the distances you can walk shorter, you should report back to your doctor.

I sometimes get a pain after eating. The doctor told me this was ‘post-prandial angina’. What exactly is this?

As your doctor says, this is angina which occurs after a meal.

Eating a large meal can increase the work that the heart has to do by 20% (to digest the food) so angina may occur if you have coronary narrowings. The usual sequence goes something like this: meal – walk the dog – angina. This happens because you have exercised too soon after a meal, adding stress to the heart. Post-prandial angina can be a warning of more severe coronary disease and I expect your doctor will be giving you some more tests.

Sometimes when I drive, for instance in the rush hour, I get angina symptoms – am I wise to carry on?

No. You must not drive until your symptoms are controlled, either by medication or surgery.

TESTS

What tests might I have to undergo for angina?

Your doctor will examine you, check your weight and blood pressure and listen to your heart for certain sounds and noises in your chest. Your blood should be checked when you have not eaten overnight to measure the fat content (cholesterol – see the section Risks of high cholesterol levels in Chapter 2).

Your doctor may want to do an electrocardiogram (ECG) (see below) which is a means of checking the way the heart works and whether there is any damage. An exercise electrocardiogram (see question below) on a treadmill machine or bicycle may be used to assess how well your heart behaves under stress and how much you can do.

Some people may be sent to a specialist heart doctor (a cardiologist) who may suggest that you have an angiogram, with a cardiac catheter inserted (see the section Angiogram below).

ECG

My doctor is sending me for an ECG next week. I am not sure what this involves – will it mean time in hospital for an operation?

No, and it is painless and takes only 10 minutes to do. An electrocardiogram (ECG in the UK, EKG in Europe or the USA) is a simple painless test which looks at the electrical activity of the heart. It tells the doctor about your heart rate, whether you are likely to have a heart attack and if you have any hardening of your arteries, and whether your heart’s rhythm is regular or not.

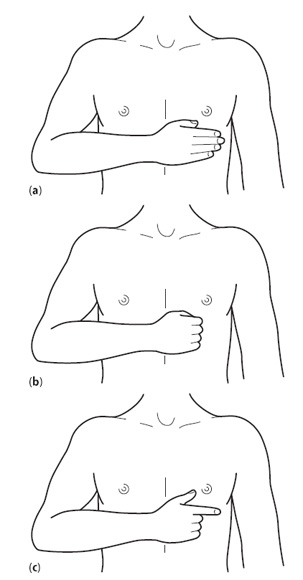

You will have electrodes (usually sticky pads) applied to your arms and legs, and six are placed across your chest (see Figure 3.2) to record the electrical activity in your heart, while you are not doing anything. Men with hairy chests may need a small area shaved. The resulting ECG trace gives an electrical picture of your heart. It is not dangerous and you cannot be electrocuted!

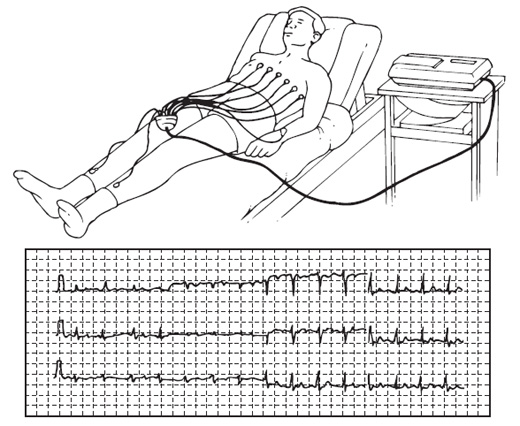

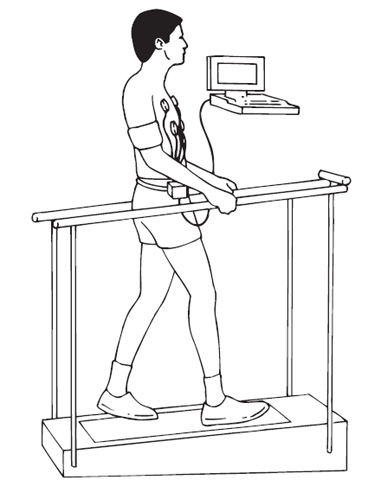

What does an exercise ECG involve?

An exercise ECG records the electrical activity of your heart when

you are walking on a treadmill (or bicycle) exercise machine (see Figure 3.3); in other words, it imitates you walking in the street or uphill, when the effect of any coronary narrowing is most likely to show up. It is used to help your doctor when unsure whether you have angina or, if you have angina, to decide whether it is severe or not.

The test speeds up every 3 minutes and the uphill slope is increased to give your heart a gradual stress. The doctor looks for any changes on the ECG, whether you are getting chest pains or are unduly short of breath, and an eye is kept on your blood pressure. Whilst on the treadmill, tell the doctor or technician if you have any pain or discomfort, or if you feel light-headed or sweaty. When the machine is stopped, the heart rate is monitored for another 5 minutes or so to see what happens.

Figure 3.2 An electrocardiogram is being taken while the patient is at rest. The trace from the machine is also shown.

Figure 3.3 An electrocardiogram is being taken while the patient

is on a treadmill.

I have an appointment for an exercise ECG. How should I prepare for it?

Wear comfortable shoes and loose clothing. Do not eat a meal or have caffeine drinks for 2 hours beforehand. Bring along any medication you are taking, including your nitrate tablets (see the section Treatment on p. 99). If you have a cold or flu, tell your doctor so that the test can be postponed.

My ECG last week was absolutely normal. However, because the doctor still thinks that I have angina, I have got to go for more tests. Why?

You probably had an ECG at rest (lying down) and, if this was normal, it does not rule out coronary artery disease. It can be falsely reassuring, so an exercise ECG is usually advised. If the ECG is abnormal at rest or on exercise, you may then need further tests to try and find out if coronary narrowing exists and how severe it is.

What makes the exercise test abnormal?

An exercise test may suggest that you have coronary artery disease

if the ECG changes, if you get pain of a certain kind or get out of breath, or if your blood pressure falls. As a rule, the longer you can keep going, the better: 9 minutes is average and 12 minutes or more is good. The doctor will tell you the result of the test in the clinic and may make recommendations for treatment or further tests. If you get pain or your ECG shows changes in less than 6 minutes, then this is a strong sign that you have narrowed arteries and need specialised treatment.

My doctor says the exercise test is equivocal, so he can’t be sure if there is or isn’t a problem, and is sending me for a nuclear scan. Will I be radioactive?

No, but I understand your concern. A ‘nuclear’ or perfusion scan is an outpatient test which looks at blood flow to the heart. If there is an area of the heart muscle that does not show up on the scan, it could be a permanent scar such as occurs after a heart attack. If an area does not show up after exercise but returns a few hours later, it means the blood supply to that area is reduced by a narrowing in the coronary artery and there is only temporary lack of blood nutrients, so the heart muscle is viable and it is not a scar.

A nuclear scan is used to clarify any doubts when the ECG alone gives an uncertain result. It can also be used when people can’t exercise (for example, because they have arthritis), when the heart can be speeded up using drugs through a vein in the arm. A scan like this helps the doctor decide what’s best for you and there is no need to be worried about it.

Angiogram

I have been told to go to the hospital for an angiogram. What is this and what does it involve?

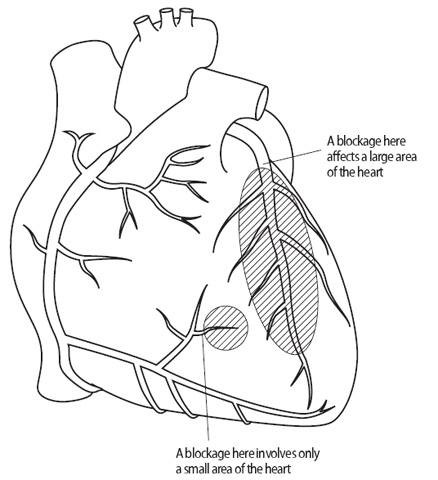

A coronary angiogram (pronounced ‘ann-gee-o-gram’) is also

known as cardiac catheterisation. This is a technique for establishing if there are any narrowings in your coronary arteries, how severe they are and whether they represent an increased risk of heart attack (see Figure 3.4). If narrowings are severe and in dangerous places, the doctor will then know that surgery is the best treatment for you. An angiogram can also give information about the heart valves and the quality of the muscle pump (left ventricle) and whether there is any damage.

The test involves small tubes (catheters) being passed through your arteries. Special X-rays are then taken of the coronary arteries and the heart muscle. When a dye is injected into the tube, any narrowings will be shown and any danger discovered. This test is straightforward but only done when there is a probability of narrowing that could be corrected by an operation or by the technique of angioplasty (see question later on Percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty).

You will usually be in and out the same day. You will be given a ward bed and have nothing to eat or drink for 4 hours before the test as, just occasionally, the dye used to show up the arteries can make people feel sick.

You may be given medicine to help you relax. You will be taken to the catheter laboratory usually by a porter or a nurse. Some hospitals use trolleys, others wheelchairs and, in many, you simply walk down with the nurse. The laboratory nurses will introduce themselves and you will meet the cardiologist who is doing the angiogram. The ‘cath lab’ is full of sophisticated equipment all designed to help diagnose your problem.

Figure 3.4 The relative risks of coronary artery blockage.

You will be asked to lie on a table (usually it is rather hard!) beneath an X-ray camera, which will make a noise when in use. TV screens will show the procedure as it’s happening, so that you can watch what’s going on (if you want to).

There are two ways of doing the angiogram – one from the arm and one from the leg. Most procedures are done from the leg, but different hospitals have different procedures, and the leg procedure may not be suitable for some people because of hardened leg arteries.

A local anaesthetic is applied to the top of your leg and you will feel a needle prick followed by a stinging numbing sensation. This is the only discomfort that you should feel. A fine tube is passed through the artery all the way to your heart. You will not feel this tube. Once the tube (the catheter) is safely in place, dye is injected into the arteries and the ventricle (pumping chamber) and pictures will be taken. You will hear the camera run several times as pictures are taken from different angles, and the camera will move over your chest to the left and right. Imagine your arteries to the heart are like a big tree and that you are walking around the bottom looking up at all the big and little branches; as you move around, any area of overlap becomes clear. So it is with the camera: it moves to unravel the branches so that nothing is missed. You may be asked to hold your breath from time to time and your arms may be put over your head if they are in the camera’s way.

The whole procedure usually takes less than 30 minutes and often only 10–15 minutes.

I am told I need an angiogram but I saw on TV a new kind of angiogram using CT scanning. What’s this?

It’s known as 64-channel multi-detector computed tomography (MDCT). It is an outpatient specialised X-ray procedure which can take pictures of your arteries in less than half an hour. You have an injection in a vein (not an artery) and your heart is slowed, usually by taking a beta-blocker drug beforehand, as this leads to better pictures. It’s an exciting new technique which does not replace an angiogram but can be used instead when the diagnosis of heart disease is unlikely but the doctor is not certain. It also is used when the person is at risk but has no symptoms – for example, someone with diabetes who has no chest pain but an abnormal ECG. It does involve X-rays so cannot be used casually in a check-up. New scanners are being introduced which are claimed to reduce X-ray exposure by 80% so this is going to be an exciting area of development with the possibility of repeated scans to monitor progress.

MRI does not involve X-rays so can I have an MRI instead of an angiogram?

Not yet. Magnetic resonance arteriography (MRA) can show up any problems in the aorta and renal (kidney) arteries but not yet in the coronary arteries. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can tell us about the structure and pumping of the heart.

Is there any difference between an angiogram from the arm or the leg?

The leg approach does not involve stitches but pressure is needed for 10 minutes or so to stop the bleeding (a tiny hole is made in the artery by a fine needle). To prevent re-bleeding, you will be advised to rest in bed for 4–6 hours. This technique is ‘percutaneous’ which means ‘through the skin’ but no surgical cut is involved. Devices have been developed to ‘plug’ the hole in the artery and, if you are a suitable candidate, the artery will be closed and you will not need pressure on the groin. You will rest in bed for about an hour and then get up and about, going home sooner.

The arm approach is usually percutaneous at the wrist (radial artery) and does not need bed or chair rest for more than an hour.

The arm approach at the elbow can be percutaneous but often needs a cut and then stitches (the jargon we use is cut-down). Again, you are up and moving very soon. The wrist and leg techniques are the most common. The wrist approach is being used more frequently but is not suitable for everyone.

I have been on warfarin tablets for some time now, to prevent blood clots. Do I need to stop or reduce my warfarin before the angiogram?

Warfarin is a medication used to prevent blood clots from forming. It is not always necessary to stop or reduce warfarin with an angiogram taken from the arm, but it is essential with the leg approach to prevent severe bruising. We usually advise four days of no therapy before an angiogram. Always remind the doctor that you are taking warfarin so your clotting can be checked before the procedure.

I’m taking aspirin every day – do I need to stop this for the angiogram?

No, this is not necessary. The mild blood-thinning action of aspirin helps prevent clotting in the artery narrowings but it does not usually significantly increase the tendency to bruising or bleeding. The same applies if you are taking clopidogrel as an alternative to aspirin, or both together.

Is the angiogram at all painful?

The only discomfort should be the injection of local anaesthetic. When the dye is injected into your muscle pump, you may feel hot and flushed with a strange warm feeling in your bottom. This passes quickly. Sometimes, when the catheter is in the pumping chamber, your heart may appear to miss a beat or flutter for a few seconds. Don’t be afraid; this is all routine.

After the procedure, pressure will be applied to your groin to stop the bleeding (about 15 minutes) and you will be asked to rest in bed for 4–6 hours while the small hole in your artery closes. If your arm has been used, a pressure bandage will be applied to your wrist.

Is the angiogram procedure dangerous?

All tests have a slight risk but in an experienced centre the

complication rate is about 1 in 1000. Remember that this figure includes emergency cases and people who are ill as well as people undergoing routine tests. The test is never done without a good reason and the risks are very low.

What happens after I have had my angiogram?

Most departments have a recovery area, but if this is not available your ward nurse will collect you from the ‘cath’ department and take you back to your bed on the ward. If you have had an angiogram by the leg approach, until you are safely back in bed, you may be asked to press on the leg used and to keep it as straight as possible. This is to prevent further bleeding from the site. This rarely happens but, if it does, don’t panic; press as the nurse or doctor did and call for help.

Your nurse will record your pulse and blood pressure at frequent intervals to check that all is well. The site of the catheter insertion will be checked and the pulses felt in your feet or arm. If you notice any blood, apply pressure as before and tell your nurse. If your arm or leg feels cold, also tell the nurse.

If the arm has been used, you will get up almost straight away but, if the leg is used or a ‘plug’ has not been inserted, you will be asked to remain in bed for 4–6 hours, still keeping that leg straight. When you wish to go to the toilet, the nurse will bring the urinal or bedpan. If you have had a leg angiogram, you can usually get out of bed after 4–6 hours (1–2 hours if a plug has been inserted). Check when it is safe to get up. Don’t get up without checking first.

How long after my angiogram will I get my results?

When your films have been developed and studied, the doctors will come to discuss the results of your angiogram with you, usually the same day. Some hospitals have a weekly conference so there may be a delay. Any further treatment that you may need, either medical or surgical, will then be discussed with you, either before you go home or in the outpatient clinic after the conference.

If the coronary arteries are hardened, the doctor will be able to show you your results by means of a diagram.

What happens after I have been discharged from hospital, following the angiogram?

Problems are rare. Sometimes the leg is bruised but this slowly fades over 2–3 weeks. Occasionally a hard lump, like a gland, is felt in the groin: this is just a bruise again. Don’t worry – if it is tender, take painkillers. Have a quiet evening when you get home, but you can be up and about the next day. Any sticking plaster is best removed in the bath the following morning. If you have had a leg angiogram, you should avoid strenuous exercise for 48 hours. If you have had an arm cut-down angiogram, you need to make arrangements for stitch removal if the non-dissolvable sort have been used – your family doctor will do this at about seven days. If pain continues, or the scar looks red and swollen, go to your doctor. It is unusual, but infection can occur and antibiotics will then be needed.

If you are taking warfarin, you should start your tablets again the same day, although it is a good plan to confirm this with the hospital doctor before leaving. Those who work can get back to work usually in a couple of days; driving is possible also the next day.

I always thought that angina was a man’s problem. Do women get angina?

Coronary disease is the most important cause of death and disability in women. It is seven times more likely to cause premature death in women than breast cancer. Angina is just as much a woman’s problem as a man’s (see the section Women and coronary artery disease in Chapter 2).

I have had my angiogram and my arteries are clear, but I still have angina. My doctor says that I have Syndrome X – what does this mean?

This is a condition which is more common in women. There is no extra risk of a heart attack or dropping dead, but nearly two-thirds of people with chest pain and normal arteries who suffer from angina are significantly limited by it. It is very difficult to treat. Drugs that relax the arteries to try and improve the blood flow (nitrates, calcium antagonists, nicorandil) may help. It is important to rule out other problems that may mimic angina, in particular a hiatus hernia or excess stomach acid.

People who suffer from Syndrome X can help themselves by:

•not smoking;

•exercising as much as possible; and

•losing weight if they need to.

It is a very frustrating condition to treat and we do not have all the answers – some people are helped, some are not. It is important, however, not to give up trying to help. It is a real condition and not ‘in the mind’.

TREATMENT

What is there, apart from medication, to treat angina?

Relief measures other than medication include angioplasty and surgery. First, there are some general self-help measures. These have been discussed before but to summarise:

•stop smoking;

•lose weight;

•cut down on alcohol;

•take exercise;

•Take life easier by reducing stress.

Table 3.2 Drugs for angina

|

Nitrates |

|

Isosorbide mononitrate |

Elantan, Imdur, Ismo, Isotard |

|

Glyceryl trinitrate |

|

|

Beta blockers |

|

Atenolol |

Tenormin, Totamol |

Acebutolol |

Sectral |

Bisoprolol |

Monocor, Emcor |

Metoprolol |

Betaloc, Lopresor |

Nadolol |

Corgard |

Oxprenolol |

Trasicor |

Pindolol |

Visken |

Propranolol |

Inderal, Beta-Prograne |

Timolol |

Betim, Blocadren |

Calcium antagonists |

|

Amlodipine |

Istin |

Diltiazem |

Adizem, Dilzem, Tildiem |

Felodipine |

Plendil |

Nicardipine |

Cardene |

Nifedipine |

Adalat, Adalat LA, Cardilate MR, Coracten XL |

Nisoldipine |

Syscor MR |

Verapamil |

Cordilox, Securon, Univer |

Potassium channel activators |

|

Nicorandil |

Ikorel |

Sinus node slowers |

|

Ivabradine |

Procoralan |

The use of aspirin as a preventative drug has been discussed a lot in the media recently. What does aspirin do?

Aspirin helps stop blood clotting. It reduces by 25% the risk of a

heart attack and helps prevent strokes in people with angina or who have had a heart attack. You only need 75 mg a day and should not take more, unless specified by your doctor; 75 mg is a quarter of an adult 300 mg tablet. It occasionally upsets the stomach and a small number of people with asthma or bronchitis may be sensitive to it (it worsens the wheezing). Overall it is cheap, safe and very effective. Special types of coated aspirin are available for those who get indigestion but they are not always helpful. Taking a compound like Alka-Seltzer is another way of taking aspirin and reducing the chances of a stomach upset; it contains 324 mg aspirin, so you will need to take only a quarter.

I get indigestion on aspirin – is there an alternative?

Clopidogrel (Plavix) 75 mg daily thins the blood to the same degree as aspirin and is used as an alternative. It is only available on prescription. It still may cause indigestion and it may be best to stay on aspirin and use a drug that blocks stomach acid such as omeprazole.

Medication

What relieves the pain of angina? Do I have to take medication?

Angina is relieved after 1–2 minutes by slowing down or stopping

activity, or using a nitrate tablet or spray, usually GTN, short for glyceryl trinitrate. If you get pain on walking after a meal and stop to take an indigestion tablet, it will seem as if the tablet has helped. In fact it was the stopping that relieved the pain: this is often how angina and indigestion get confused.

Several drugs are available to stop angina occurring or to deal with an attack. We have already discussed cholesterol-lowering diets and tablets in Chapter 2 and it is essential that people with angina have a cholesterol test and know the result.

Anyone with angina should be prescribed and told how to use sublingual (under the tongue) nitrates and aspirin or clopidogrel. The other medications – oral nitrates, beta-blockers, calcium antagonists and potassium channel activators (discussed below) – are prescribed as necessary. See Table 3.2 for a list of currently available medications. Check the trade name against the generic name.

Nitrates

How do the nitrates work?

Nitrates open up the arteries by relaxing the muscle in the artery wall. They relax the coronary arteries to improve the blood flow; by relaxing the peripheral arteries (such as in the legs) and veins, they reduce the work the heart has to do. As the problem is one of too much demand and too little supply, nitrates attempt to rectify the situation by improving supply (by dilating the artery) and reducing demand (the heart pumps against less resistance as the arteries are relaxed).

My mother has been given sublingual nitrates but seems unclear what to do. As I am her carer, what do I need to know?

Sublingual nitrates are taken in tablet or spray form and are absorbed via the veins under the tongue. They are effective in 1–2 minutes and last 20–30 minutes. They relieve attacks and can be used when your mother fears an attack; for example, she can use them at the bottom of a hill before she starts to climb. Headache is the main side effect.

After you collect them from the chemist, the tablets last only about 8 weeks and have to be stored correctly.

•Keep the tablets in the airtight bottle in which they have been dispensed.

•After use, close the bottle tightly.

•Do not put cotton wool, other tablets, or anything else in the bottle with these tablets.

•Store the tablets in a cool place. When your mother carries them with her, tell her not to put them too close to the heat of her body – she could keep them in a purse or handbag (other people can carry them in a briefcase).

•If she does not use the tablets within 8 weeks of opening the bottle, get a fresh supply and discard the old tablets. An active tablet produces a slight burning sensation when placed under the tongue. If this does not happen, you should get a fresh supply for her.

The spray lasts 2–3 years but is more expensive. It is useful when attacks are infrequent as it lasts longer in storage. Tablets can be bought over the counter without prescription whereas the spray needs a doctor’s prescription.

I have been given nitrate tablets to swallow. Are these different from the sublingual ones?

Yes, nitrates also come as tablets that are swallowed once or twice daily and can be taken on a regular basis to reduce your angina attacks and improve your ability to take exercise. The commonest are isosorbide mononitrate which are taken twice daily, or in slow release formulations (Imdur, Elantan, Ismo) once daily. They must not be taken more often or the body gets used to them – known as tolerance – and they are then ineffective in relieving angina. Sublingual tablets are only taken when you have, or fear, an angina attack coming on.

There are also nitrate patches which are effective when placed on the skin like a plaster; they have to be taken off after 12 hours or your body again develops tolerance. Used 12 hours on and 12 hours off, they act as a back-up and can be helpful overnight if put on in the evening and taken off in the morning. They should not be used on their own because, with 12 hours off, no angina protection is provided for that period.

Since I have been taking nitrates for my angina, I seem to get headaches. Is this due to my medication and are there any other side effects?

Headache is certainly the most frequent side effect. Occasionally you may get palpitations (see Chapter 6) or flushing and sometimes the tablets under your tongue make your breath smell. Rarely, and particularly if the tablets are taken within a short while of drinking alcohol or when starving, you might get a dizzy attack, caused by a temporary lowering of blood pressure. If headaches are a problem, the nitrates will be stopped and other drugs substituted.

Beta-blockers

I have been prescribed beta-blockers for my angina. What are these?

These are very important medications. They are the only ones (besides aspirin, cholesterol-lowering tablets and ACE inhibitors) that have been medically proved to lengthen the life of many people with heart problems. Beta-blockers reduce the work that the heart has to do by slowing the heart rate and lowering the blood pressure. They also reduce the force with which the heart muscle contracts, so that it needs less energy. By slowing the heart rate, they allow more time for blood to flow to the heart past the narrowings, and they blunt the heart rate’s response to exercise. If you were to run for a bus, your heart rate might rise to 130 beats per minute (bpm); with a beta-blocker it might not get above 110 bpm, so you would be less likely to develop angina. A slower heart rate is therefore a feature of beta-blocker treatment and one of the main reasons that they are so effective in reducing the number of attacks that people experience, as well as allowing them to walk further. They also help people to live longer after a heart attack and may therefore help protect people with angina from serious complications.

Beta-blockers are swallowed, once or twice daily. The commonest in use are atenolol and bisoprolol but a large number exist. They should never be stopped suddenly because the heart can rebound the other way, and this can lead to severe bouts of chest pain or even a heart attack.

I have been taking beta-blockers regularly. Are there any side effects with this treatment?

Yes, beta-blockers can cause:

•wheezing (they should not be given to asthmatics);

•breathlessness and fatigue (general tiredness with feelings of being ‘worn out’ or ‘washed out’);

•cold hands and feet and heavy leg muscles (by slowing the circulation);

•muzzy head with poor concentration and vivid dreams;

•rarely, depression;

•occasional erection problems in men and reduced sex drive in women.

Do not stop taking your medication if you experience any of these effects. Tell your doctor and your tablets can be changed.

I have been very forgetful lately. Do you think this could be

due to the beta-blockers I am taking? Are there any others I

could take?

Yes. Some beta-blockers (such as atenolol) are soluble in water and do not cross into the brain, so dreams and confusion or forgetfulness are less common. These are known as hydrophilic (dissolve in water) types. Others (such as propranolol) are soluble in fat (lipophilic) and can cross into the brain. Although you may have more side effects with propranolol, you may also find that you are less anxious.

I have noticed that I have a slight tremor. Can beta-blockers relieve tremor and shakiness?

Yes, beta-blockers can be very effective, particularly propranolol, if you have tremor. As a result they can also help people with Parkinson’s disease. It is also claimed that they improve the performance of snooker players and golfers! This is likely where anxiety and tremor are a major problem, of course, but the routine use of beta-blockers to improve performance is not approved of!

If my pulse drops below 50, should I stop taking my beta-blockers?

No. Beta-blockers act to slow the heart. The coronary arteries receive their oxygen and food between the beats, so the slower the rate, the more time the heart has to receive its food supply.

Your treatment will only be stopped if, owing to your slow heart rate, your symptoms of lethargy and fatigue become a problem. It is best to reduce the dose first. Do not stop any treatment without your doctor’s advice. Beta-blockers should certainly not be stopped suddenly as this can cause a rebound chest pain and could be very dangerous.

When is the best time to take beta-blockers?

The once-a-day variety such as atenolol or bisoprolol are useful for people who have problems in remembering to take tablets (see question later in this section), and these are often best taken at night. This is a useful time to take them if they make you feel drowsy.

Is it a disaster if I forget to collect my prescription and run out of tablets?

You must try not to run out of your tablets as you may get rebound chest pain. Your chemist will give you some until you get your prescription renewed: it is dangerous to stop beta-blockers suddenly (see question above about stopping tablets suddenly).

My doctor prescribed beta-blockers some time ago and now has put me on nitrates as well. Is this safe?

Yes, the combination is very effective. For example, you may be given atenolol plus isosorbide mononitrate.

Calcium antagonists

What are calcium antagonists (calcium blockers)?

Calcium is an ion (an electrically charged particle) which increases the tone of muscles and strengthens the contraction of the muscle. The muscle in the wall of the artery depends on calcium for its tone, so if the movement of calcium into the muscle cell is ‘antagonised’ or ‘blocked’, the muscle will relax. As the muscle relaxes the artery becomes bigger, blood flow increases and the demands on the heart decrease.

Do calcium antagonists act in the same way as nitrates?

In a way, yes. They both increase the size of arteries but by different mechanisms. In combination they may have an additive effect, so you may be prescribed both.

Can I take calcium antagonists with beta-blockers?

Only some calcium antagonists. Verapamil must never be taken with a beta-blocker because of the danger of slowing the heart too dramatically. Diltiazem is used cautiously by some hospitals. Amlodipine, felodipine and nifedipine are quite safe and effective in combination with beta-blockers. Never mix your medications without first checking with your doctor or pharmacist.

I have not got on well with verapamil so my doctor plans to change my medication to nifedipine. Are there differences between the various types of calcium antagonists?

There are several calcium antagonists on the market and they have some differences which are important. Verapamil and diltiazem slow the heart rate as well as widening blood vessels, so they are a good alternative to beta-blockers, if beta-blockers are not suitable for you (for instance if you have asthma) or they are giving you unacceptable side effects. The calcium antagonists amlodipine, felodipine and nifedipine do not slow your heart rate and are often used in combination with beta-blockers.

Will I experience any side effects with calcium antagonists?

There are plenty of calcium antagonists on the market, so if you are prescribed one that does not suit you, tell your doctor so that your medication can be changed. Two common effects you are likely to experience are headaches and flushing, because these medications open up the arteries.

Another common side effect is swollen ankles and this does not respond to water tablets (diuretics; see the section Treatment in Chapter 5). Ankle swelling may improve as the dose is decreased but often the tablets have to be discontinued. Verapamil and diltiazem are less likely to lead to swollen ankles.

Constipation can be a problem if you are taking verapamil (and more so the older you get). High-fibre diets and lactulose can help but, if constipation becomes a serious problem, your doctor will change you onto another type of calcium antagonist.

Rarely, eye pain and gum problems occur. Calcium antagonists do not usually cause the tiredness that can be a problem with beta-blockers. They may be less effective if you continue to smoke, whereas beta-blocker treatment is not affected by smoking. (Remember smoking causes heart attacks and can kill you.)

Why did my doctor prescribe beta-blockers for me rather than calcium antagonists?

Usually calcium antagonists are prescribed only if beta-blockers are not suitable or are giving side effects. Some calcium antagonists can be combined with beta-blockers to give an additional benefit and all of them can be combined with nitrates (see question above about combining these medications).

I have found that beta-blockers have given me an unfortunate problem, in affecting my love life. My doctor says he will try me on calcium antagonists, but not straight away. Why not?

Your doctor will do this gradually. The beta-blocker must be wound down and the calcium antagonist wound up over a period of time. Calcium antagonists do not give you protection when beta-blockers are suddenly stopped.

Potassium channel activators

I seem to have been given all sorts of medication for my angina over time. My doctor has now said he wants me to try a new type called a potassium channel activator. I have never heard of this one! Will it do any good?

These are medications which work half like a nitrate and half like a calcium antagonist. There is only one available at the moment – nicorandil. It can be used on its own or in combination with the other three types of medication for angina (see Table 3.2). It does not cause swollen ankles, but headaches can be a problem. It is as good as the other medications but not any better, and it is very expensive in comparison. It tends to be used after the other options have been tried and in this way can be very helpful. So if you have tried all the other options, you might – with luck – find that this suits you. Do not drive or operate machinery until settled on nicorandil and your performance is not impaired.

My doctor says she would like to try me on ivabradine as I have side effects on atenolol. How is it different?

Ivabradine (Procoralan) is a new drug which slows the heart rate by an electrical action, so it is different from a beta-blocker. It may be used when beta-blockers are not tolerated and when the heart rhythm is regular (in sinus rhythm). Side effects are not common but include temporary visual disturbances (blurring), headache and dizziness. The pulse must be monitored to make sure it’s regular and not below 50 beats per minute. Unlike beta-blockers there is no evidence to date that it prolongs life, but it does relieve angina pain.

Taking your medication

I am rather confused over the various medications available for angina. How many can I take at any one time?

Quite often, too many are taken at any one time! You will need aspirin and, usually, a cholesterol-lowering tablet (usually a statin) to reduce your chances of the coronary narrowings becoming worse. If one angina drug doesn’t work, there is a tendency among doctors to add other medications rather than change the combination. If one drug partly works, it makes sense to increase its strength or add another in but, if it’s not working, it makes no sense to continue it. There is no medical evidence that taking more than two medications for angina is better than one or two used properly. Many people could have their medication simplified, and it is possible that your doctor does not know exactly what you are taking, so always take all your tablets with you when you visit the surgery. If you are on many different tablets, discuss their strengths with your doctor and whether all of them are necessary. Do not make changes on your own. Many medications, taken twice or three times a day, are now in once-a-day formulations which makes life easier.

I am bad at remembering to take tablets. What should I do?

If you are on frequent doses (say three times a day), ask for a once-a-day alternative. For example, if you are on diltiazem 60 mg three times a day and isosorbide mononitrate 20 mg twice a day (five tablets), this could be changed to long-acting diltiazem 200 mg once a day and long-acting mononitrate once a day (that is, two tablets altogether) with the same effect. Beta-blockers are often best taken at night. Any sedative side effects can then be slept off.

Try to establish a routine. Take your medication at the same time of day – with your morning cup of tea or after brushing your teeth. If you are on a lot of tablets, special pill boxes are available, such as the Dosette, that are split into time of day and days of the week: ask your pharmacist about these. Ask your partner or friends to remind you or stick reminders by the phone or on the fridge (use one of those reminder magnets).

Remember not to run out (see a previous question on this). If you have a question about your medication, write it down – most people forget when they go to the doctor. It’s a good idea to ask what each tablet is for and when you should take it. And remember to take all your tablets with you to the surgery – the doctor may not know what you are taking.

If you miss a dose of beta-blockers, take an extra tablet to catch up – others do not need boosting so just get back on schedule.

I have been told that cold remedies react with angina tablets. What can I do if I need them?

Some of these medications react, some don’t. Show your heart tablets to the pharmacist and ask for advice about what you can or cannot take.

Am I allowed to drink alcohol with the medication?

Yes. However, alcohol does widen blood vessels, so the effects may add up with those of nitrates and calcium antagonists to give you more chance of a headache.

Are there any special dietary precautions that I should take while I am on angina medications?

The only precaution is to avoid grapefruit juice as it reacts with some medications in the liver – especially calcium antagonists and some statins. Advice on orange juice is to avoid it within 4 hours of taking your medication.

Are there any new medications for angina in the pipeline?

There are always new ones coming along. Most are variations on what we have already. We always need to see whether they are better than what we have or whether they can be added in to improve what we have. Always beware of exaggerated claims and look carefully at any statistics that are given.

I have heard that a drug called trimetazidine is available – what is this?

Trimetazidine is an interesting drug; it acts to improve oxygen supply by affecting how the cells of the heart work. It does not affect heart rate or blood pressure. It is not available (unless specially requested) in the UK but it is widely available elsewhere. It is an effective drug with minimal indigestion side effects and can be combined with all the other drugs available. It is the first of a class of drugs known as ‘metabolic agents’ because of its action improving how the cells function.

I read in the paper that there is a new drug called ranolozine about to become available – in what way is it different?

Ranolozine (Ranexa) acts a bit like trimetazidine (see above) but also inhibits the build-up of sodium and calcium in the cells, causing relaxation and improving oxygen supply, so angina is reduced. It can be added to other drugs but caution is needed in case there is a clash in the way they are metabolised (broken down). It can cause constipation, nausea and dizziness but these side effects are not common. Some evidence exists that it improves diabetic control. It appears to be a useful new therapy with a good safety profile.

Surgery

Angioplasty

I have been told that I need an angioplasty. What is this?

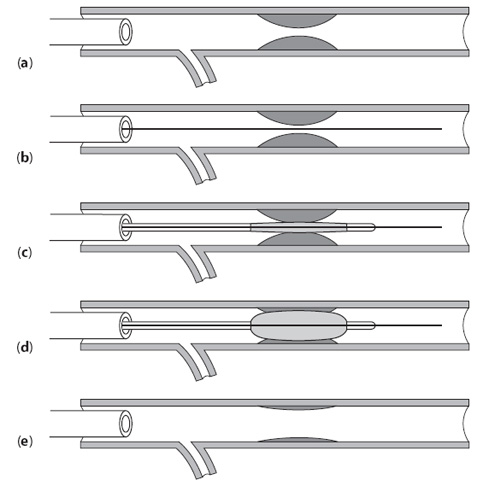

Percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty (PTCA) is a method of using a balloon to squash or push the arterial narrowings out of the way. (The medical word for these narrowings is stenosis, pronounced ‘sten-oh-siss’. ) PTCA is often shortened to ‘angioplasty’. Because stents are used in nearly all cases (see later) we often call this percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).

It is performed in the catheter laboratory usually by the same team who does the angiograms (see the section Angiograms above) so you may meet some familiar faces. The doctor doing the operation will be the cardiologist, with whom you may already have had a consultation.

After a local anaesthetic, a thin tube (the catheter) is inserted into your artery at the top of your leg, or occasionally in an artery in your arm either at the elbow (brachial artery) or, more frequently, the wrist (radial artery). The catheter is guided under X-ray control to the heart, up the main artery known as the aorta (see Chapter 1). You cannot feel the tube moving. It is then directed into the coronary artery that contains the narrowing. This catheter is called the guide catheter (see Figure 3.5). A very fine wire (the guidewire) is now passed up through this catheter and into the coronary artery where it is steered past the narrowing. This may be a bit fiddly. Once it is across the narrowing, the balloon catheter is passed along the wire (like a monorail) and, following the wire, it slides across the narrowing. The balloon is blown up (inflated) once it is in position. This may cause some chest pain – let the doctor know if you have any pain at all.

The pressure in the balloon is increased and the narrowed part is pushed back into the wall of the artery where it has come from. The result is checked after the balloon has been deflated and removed back into the guide catheter. At this point the wire is still in place so that the balloon can be used again, or exchanged for a bigger balloon, if the result needs to be improved.

Figure 3.5 The technique of angioplasty. (a) Guide catheter in left coronary artery. (b) Guidewire advanced through narrowing. (c) Balloon positioned with markers. (d) Balloon inflated. (e) Catheter, with guidewire and balloon, removed leaving expanded artery.

Once the doctor is satisfied with the result, the balloon and wire are removed; and you will be given a dye injection which checks how well the operation has gone; the guide catheter is then removed.

A small insertion sheath is left in the groin for about four hours, because the effects of blood thinning medication (heparin), used to prevent clotting on the wire or balloon, need to wear off. The sheath is removed on the ward and the groin pressed firmly for 20 minutes or so. If the radial artery (at the wrist) is used, it is firmly bandaged. A pressure device may be used which is slowly deflated. Often, the leg artery is plugged so that you can get up and about more quickly.

I am rather worried about the PTCA procedure. Will I be given any relaxing medicine beforehand?

This depends on you and how you are feeling. If you are anxious, then an injection of diazepam (Diazemuls or Valium) or midazolam helps you to relax.

Will I feel any pain when I undergo PTCA?

The local anaesthetic stings rather like when you have an angiogram. When the balloon is inflated, it blocks the artery temporarily (usually for 30 seconds or so), so you may get some chest pain. Let the doctor know if you are feeling any pain.

How long does the PTCA procedure last? Will I need to be in hospital for long?

Some procedures are quick (5–10 minutes), others take up to 1 hour. It depends on the number of narrowings in your particular case, whether they can be reached easily and whether you need a stent (see questions below on stents) or not.

Usually you will be in hospital for one night. This is the big advantage over bypass surgery (see the question later on bypass surgery) – you don’t have to spend long in hospital and you recuperate rapidly.

How long will the effects of PTCA last?

In 7 cases out of 10, PTCA gives a complete cure. However, for reasons we don’t understand fully, 30% of the narrowings come back in about 4–6 months. You will only know that the operation has not been entirely successful because your angina will return.

If my angina returns, can the PTCA be repeated?

Yes – up to five or six times, and each time it is performed, you have a 7 out of 10 chance of it remaining successful.

If you have no angina after 6 months, the effects will last for years, so the first 6 months constitute an important hurdle to overcome.

Can the cardiologist perform PTCA on more than one narrowing at a time?

Yes, as many as are necessary (but see the question below on unsuitable narrowings). Sometimes the procedure may be staged so that you come back for other narrowings to be done on a separate occasion. This decision depends on the importance of each narrowing and whether the procedure was an emergency or not – in an emergency only the most dangerous narrowing is done (the culprit), and the rest are completed when matters have settled down.

I am worried that things may go wrong when I have my PTCA. Is this likely?

Things are very unlikely to go wrong but, if they do not work out, there are other ways to sort out the problem. Complications are not common but they do occur. Sometimes the artery tears and closes completely. We can correct this by inserting a stent or moving on to bypass surgery (see below). However, angioplasty is successful over 95% of the time. You will be asked to sign a form giving your consent to having a stent inserted or bypass surgery, just in case the PTCA is not successful.

I have been told that I am not suitable for PTCA. Why is this?

Some people have complicated narrowings and complete blockages which unfortunately are not suitable for PTCA. If you suffer from angina and many arteries are affected, a coronary bypass (see the question later on bypass surgery) may be the best option for you.

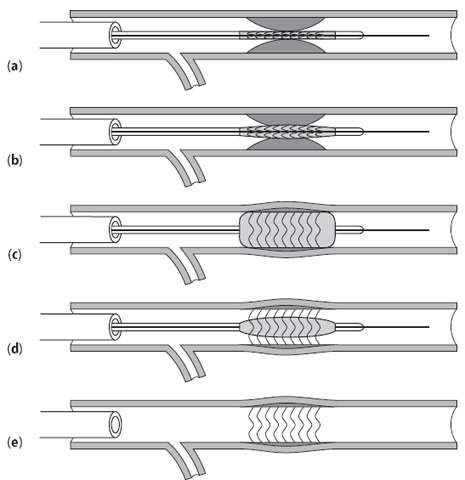

When my husband went into hospital for a PTCA, he had to sign a form saying he consented to having a stent inserted if it was found necessary during the operation. What is a stent and how does it work?

A stent is a metal mesh cage rather like a small meshwork tube (see Figure 3.6). It is made of thin flexible metal wire, and is fixed to a balloon with the balloon deflated. The original angioplasty balloon is removed – the wire is still in the artery so we have access to the narrowing – and the balloon with the stent on it is passed along the wire to the narrowing. The balloon inside the stent is inflated and the stent expands to the size of the balloon. It embeds itself into the artery wall and holds the artery open mechanically. The balloon is deflated and removed but the stent is permanently left behind. More than one stent may be used and the stent sizes vary according to the size of the arteries. Stents may be inserted without a prior balloon – this is known as direct stenting.

When will the cardiologist decide to insert a stent?

There are various reasons why the cardiologist decides to use a stent. The commonest are:

•if the angioplasty is not successful or the artery closes off;

•it is the cardiologist’s choice (the most common reason);

•if the narrowing comes back 4–6 months after angioplasty;

Figure 3.6 The technique of stent insertion. (a) The stent (like a metal cage) on balloon catheter is positioned at the problem site. (b) The balloon catheter is then inflated. (c) The stent is fully expanded and (d) left in place after the balloon has been deflated. (e) The stent remains expanded

inside the artery.

•if the artery is large and the narrowing short, as the recurrence rate with a stent is reduced to 10–15%;

•if the narrowing is within a vein used for coronary bypass.

Stents are now used in over 90% of cases because of the better long-term results, with only 15% getting a narrowing within the stent after 6 months (this figure rises to 30% with the balloon on its own). If possible, they are placed directly without using a balloon beforehand as this reduces the risk of a complication.

Drug-eluting stents have been developed and are widely used because they have better than 95% long-term success. These have a drug coated on the metal stent, which acts to stop any further narrowing occurring. They are much more expensive than ordinary stents, which are now known as bare metal stents, but obviously reduce the chances of a repeat procedure. They may be particularly important in people with a higher risk of recurrence – those who have had a recurrence already, people with diabetes, and when the artery being stented is small.

I need an MRI scan. Do I tell the radiologist about my stents?

Yes. Routine MRI scanning is safe in all patients who have had a stent in place for 6 weeks. Stainless steel stents may displace in the first 6 weeks, but other makes remain secure. The chances of a stainless steel stent moving are minimal, however, so that MRI in an emergency should go ahead. Non-urgent cases should play safe and wait 6 weeks.

I was not offered a stent as a choice. Why was this?

This is most likely because angioplasty alone gave an excellent result. Stents are not as successful in smaller arteries, so this may have been the reason. Sometimes the arteries are too tortuous to allow a stent to pass through.

I am on tablets only at the moment for my angina. Is angioplasty or stenting better than medications?

Angioplasty or stenting can relieve any pain that medications have

failed to control. They do not, however, provide any benefits compared to medication for preventing heart attacks. They are used only if conventional medical treatment does not give you relief from pain and a good quality of life. Angioplasty is a safe and effective procedure, but any operation has a slight risk, which you should avoid if possible.

I have been told that I need an angioplasty. I would prefer not to have an operation. Am I being overcautious?

Probably not. Because a narrowing looks suitable for a balloon, that doesn’t mean that it is the best treatment. Angina from a narrowing in a branch vessel that is not a danger to life will usually settle with drug treatment, and the angioplasty option can be saved for later. As angioplasty in research studies has not been shown to improve (or shorten) life expectancy, it must be used selectively and it is then a very effective procedure. Using any procedure in every circumstance invites complications and devalues what is a useful form of therapy.

I am worried about having angioplasty done. Is there any chance that I will not get through the operation?

You have a greater than 99% chance of survival. These statistics include emergency operations and very sick people – routine cases like yours have a lower risk.

When will the doctor decide that I should have an angioplasty?

If you have angina and your tablets are not controlling it, the doctor will probably refer you for an angioplasty, if the narrowings are suitable. You will have an 80–90% chance of being relieved of your angina as a result.

I have just undergone an angioplasty with a stent and now been given some medication called clopidogrel. What is this drug for?

This is a powerful aspirin-like drug that prevents clotting on stents until they fully bed in. You usually start taking it about 6 hours before the procedure with a ‘loading dose’ of 300–600 mg. You will then take at least 75 mg daily for 4 weeks with a bare metal stent. Most doctors use it with aspirin also. Clopidogrel 75 mg daily is also used as an alternative in those unable to tolerate aspirin. Clopidogrel is also used in patients with unstable angina (see the earlier section Symptoms) as it reduces the complication rate. Skin rashes are the commonest side effect, and you may also notice that you bruise easily.

I have a drug-eluting stent in place and have been told to take clopidogrel and aspirin together for a year – is that correct?

Drug-eluting stents are vulnerable to clotting just like bare metal stents but they also have a late clotting risk when clopidogrel is stopped. Though this is not common it can be serious so doctors advise clopidogrel and aspirin for at least a year, and for some people, indefinitely. Clopidogrel has to be stopped for at least 5 days if you need an operation, such as a hernia repair, to avoid bleeding. A drug-eluting stent may therefore not be used if you plan to have non-heart surgery soon after the procedure.

Now that I have had an angioplasty, which has cured me of my angina pain, can I throw away all those tablets?

No, not all! You will need to continue with aspirin, cholesterol-lowering tablets and blood pressure tablets, if necessary. Any tablets that you take for angina might be reduced or stopped. Ask your doctor first – do not stop any medication without advice.

My wife has just come out of hospital where she underwent an angioplasty. She wasn’t allowed to drive herself home. Why?

A week off is recommended. If you are recovering satisfactorily, you

can then start driving again. The DVLA need not be notified but car insurance companies must be informed. For Group II driving, see the question below.

I hold a Group II licence and drive a lorry for a living. Will I lose my job and livelihood after angioplasty?

Driving is not recommended anyway if you have angina, even if your symptoms are controlled on medical treatment. This is a safety rule to protect the general public in case you should lose control of the vehicle during an attack. If you have heart failure (see Chapter 5), the DVLA can refuse you a licence. After a heart attack, bypass or angioplasty, you should stop professional driving for 6 weeks and you will only be allowed to resume if you have no symptoms and are able to complete an exercise test to the required standard.

How many people who have undergone angioplasties or stent insertion will have to then have an urgent bypass operation?

Only about 1 in 100.

My doctor mentioned a PCI – what is this?

PCI stands for percutaneous coronary intervention and this term covers both balloons and stents.

Bypass surgery

I have had medication and lots of tests for angina. I am now being offered bypass surgery. Why do I need this?

Operations for coronary artery disease are usually designed to improve the blood supply to the heart. A decision by the consultant as to whether to advise an operation for you is based on your case history and on several special tests, including an electrocardiogram, an exercise test and an angiogram (see the section Angiogram earlier in this chapter). This last test is the most crucial one for bypass operations as it demonstrates the exact position and extent of the narrowings. An operation may be advised because of the severity of the symptoms or the extent of the disease or both. The operation may be performed to make you feel better, to prevent a heart attack or to correct life-shortening disease, thus giving you a longer and more active life.

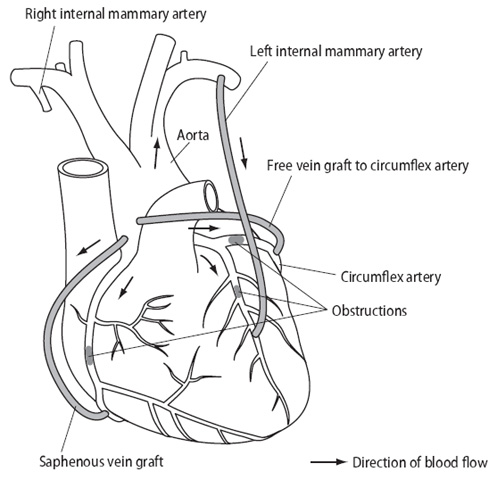

Figure 3.7 Diagram of coronary artery bypass surgery. Veins are used

from the aorta to beyond the blockage and the mammary arteries taken directly from inside the chest.

Can you tell me what the bypass operation is all about?

The most common operation for angina is a coronary artery bypass. The full name is coronary artery bypass graft or CABG – often referred to as ‘cabbage’.

A portion of vein is carefully removed from the leg and attached to the affected coronary artery beyond the narrowing. The other end of the vein is attached to the aorta, the main artery leading from the heart (see Chapter 1). In other words, the narrowing or obstruction is bypassed, just as a road bypass can avoid bottlenecks in towns. Several of these vein grafts may be placed, often one to each of the three major coronary artery branches. Frequently the graft is made with the left and right mammary artery from inside the chest (Figure 3.7). The radial artery is more frequently used now and taken from your lower arm between the wrist and elbow. Artery bypasses are believed to be stronger and longer lasting than vein bypasses. In each case your body can put up with the loss of the vein or artery used for the bypass.

In order to do these operations, the surgeon requires your heart to stop beating; so the heart and lungs are rested while the body is kept going by a heart-lung bypass machine. The operation is carried out through an incision down the front of the chest.

I read that some people can have a bypass without the need for a heart-lung machine – is this keyhole surgery?

Not really keyhole, but in selected cases the bypass can be done with the heart still beating. This is known as ‘off-pump’. In appropriate cases the results are good and there may be fewer complications. The surgeon will decide who is suitable, based on the angiogram and medical history.

I am rather confused about the differences between the cardiologist and the surgeon – aren’t they the same?

No. The cardiologist is a medical doctor and heart specialist who makes the diagnosis, investigates and treats you, and decides what is best to be done. The surgeon is a medical ‘plumber’ who puts in the bypasses and heart valves. When the job is done, the surgeon usually hands you back to the cardiologist to keep an eye on you. The cardiologist and surgeon work closely as a team to advise on and time the best treatment for you.

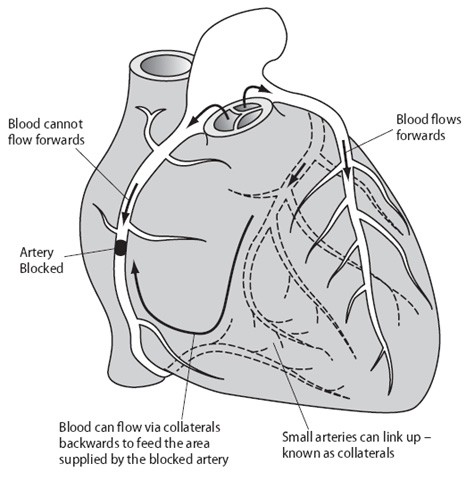

My doctor says that my heart has done its own bypass – what does he mean?

The coronary arteries link up through very small branches – they don’t come to a full stop. This means that the left coronary artery can supply the right via the links, and vice versa. If these branches enlarge, they may fill a blocked artery backwards (see Figure 3.8). This means, for example, that a blocked right coronary artery may get its blood supply from the left system. The enlarging arteries are known as collaterals. Collaterals develop over time and can be encouraged by regular exercise. If you ‘develop collaterals’, so that a blocked artery gets its blood supply from another artery, it is then as if you have done your own bypass because, in effect, the blockage has been bypassed by your own arteries.

Figure 3.8 Developing collaterals – doing your own bypass.

What do you use for a bypass operation if there are no suitable veins?

You have two arteries in the chest that can be used, two spare ones in the arms and also in the abdomen. The surgeon will find a way around the problem.

My doctor has recommended a bypass operation, but after all I’ve read about it, I don’t think I want to have it done. Am I being used as a guinea pig?

The risks of severe coronary artery disease are higher if you do nothing. It is always important to discuss your own risks so that you and your family know where you stand. Risks will vary with age, how strong your heart muscle is and the extent of the coronary disease. On average, 98 patients in 100 pull through and two therefore do not. So you have a 98% rate of success but, if you are one of the other 2%, you have a 100% chance of dying. The odds are heavily on your side but it is important to understand what the statistics mean. If, for example, I told you that, because the operation is difficult, you had a 98% chance of living, you would feel differently to hearing that you had a one in 50 chance of dying, even though the figures mean exactly the same!

How long will a bypass graft last?

It used to be said that bypass surgery lasted 10 years, but these figures are out of date. The mammary artery bypass has a better than 90% chance of working for longer than 15 years after surgery. The veins can still harden and narrow but, with the use of aspirin and cholesterol-lowering medication, the length of time these bypasses last is improving all the time. The success depends on dealing with those factors that you have some control over, in particular high cholesterol levels, smoking and high blood pressure.

What happens before the bypass operation?

The surgeon who is going to perform the operation will examine you and explain what is planned. It is a great help for you to have your teeth checked by your own dentist well beforehand so that last-minute treatment can be avoided. This is to make sure there is no hidden infection that might affect the operation. Blood samples will be taken for tests; an electrocardiogram and a chest X-ray will also be taken. You will be visited by the physiotherapist and intensive care unit nursing staff to explain details of treatment to you. Before the operation, the anaesthetist will check on your lungs and ask about any allergies. The anaesthetist is a very important member of the team – your breathing will be controlled whilst the operation is being carried out.

Your chest and legs will be carefully shaved and you will be given a special antiseptic soap to clean the skin in several baths or showers. You will not have any food or drink for 4 hours before the anaesthetic is due. About 1 hour before the operation an injection will be given which will make you drowsy. The next thing you will know is waking up in the intensive care unit with the operation completed. The operation will take about 2–4 hours.

Why is the intensive care unit different to a normal ward?

The intensive care unit (ICU) is a halfway house between the operating theatre and the ward. You can be carefully observed there until you are again fit to be left to your own devices. Immediately after the operation you will still be fully anaesthetised and on a breathing machine. On awakening several hours later, you will have a tube in your mouth attached to the breathing machine, so that for a little while you will not be able to speak properly. This can be frightening at first and frustrating. However, as soon as you are fully awake, the tube is removed. As you are likely to be very thirsty at this time, you may take sips of water. The ICU is busy and noisy with lots of sophisticated machines. They are all there to help you and make sure the operation is a success. You may find it hard to rest. As soon as the nursing staff consider that it is safe to do so, you will be transferred to the main ward. You may feel that you have lost a day or are ‘jet-lagged’ and it is easy to be confused, but matters soon right themselves and you will soon feel yourself again.

One of the first visitors to the ICU is the physiotherapist. During the operation there is a tendency for your bronchial tubes to collect sputum and become blocked, causing small areas of collapse in the lungs. These then have to be fully expanded again by deep breathing and coughing with the encouragement and assistance of the physiotherapist. Naturally, after such an operation, your chest will be sore and you may be somewhat anxious about exerting yourself. However, with proper pain-killing injections and tablets, and knowing that there is no danger of ‘bursting’ stitches, you will soon overcome this fear. Giving up smoking as long as possible before the operation will greatly help in this respect.

What happens on the normal ward when I get transferred?

As far as operations go, bypass surgery is not one of the most

painful, but many people often complain of feeling a bit low in spirits for a few days afterwards. This is only temporary and may be accompanied by other symptoms such as fatigue, poor concentration, slight blurring of vision, loss of taste, a disturbance of sleep pattern with drowsiness during the day, and restlessness and sweating at night. All these symptoms very rapidly pass off and are no cause for alarm. If it hurts to cough, clutch a small pillow to your chest (or better still a teddy bear – a present for your recovery!).

If you become constipated, mention it to the Ward Sister who will provide a mild laxative.

After one or two days, you will be encouraged to get out of bed and walk about. People vary greatly in their speed of recovery and getting up and about. There are no set rules – so if someone else appears to be doing better than you, it does not mean that anything is wrong. There is no competition involved! The nurses and physiotherapists will encourage you to get on your feet as fast as you can manage it without becoming exhausted.

You will usually be given support stockings for your legs, to prevent swelling and to keep your circulation moving. It is important that, when you are resting, you keep your legs raised on a stool or in bed, to avoid swelling during the first few days.

After about 6 to 7 days, any stitches will be removed from your chest and leg. You can have a bath if you want one. Leg wounds take longer than most to heal, and there may be a discharge of clear fluid, especially if your leg is not kept raised. This is not serious but should be pointed out to your doctor. It may feel a little numb just above the ankle on the inside of your leg.

Is it normal to get chest pains after the operation?

Muscular pains are common and can affect the chest, neck and back. They usually wear off over 2–3 weeks but can remind you of the operation for 2–3 months. Occasionally, bone and joint pain is a significant problem and anti-inflammatory tablets are prescribed. Most pains settle with simple painkillers, e.g. paracetamol or the stronger co-dydramol.

Can I lie on my side after a bypass operation?

You can lie in any position that you find comfortable.

Can the wound from a bypass operation fall apart?

No – your breastbone is wired together and you cannot undo the stitches or damage the operation. Very rarely the breastbone does not heal quickly and a click will be heard.

I am told that bypass surgery will make a large scar. Can’t it be done by keyhole surgery?

Keyhole surgery is a media phrase – it does not happen in real life. In a few carefully selected cases, a bypass operation can be done without the need to open the breastbone or stop the heart. A cut is made to the side of the breastbone through three or four ribs and, whilst the heart is still beating, the surgeon constructs the bypass. Recovery is quicker than after a full bypass operation. It is a new procedure that is very appealing to the public, but applicable only to a small number of people, and it needs more testing to prove its effectiveness. If you are offered this option, ask about your particular surgeon’s results and whether you will be entered in a research study to judge the success. Some surgeons are now opening only the lower end of the breastbone, which means that women can wear lower-cut garments, if they wish, without the scar showing.

I had a bypass some weeks ago. My scar is still tender. Why is this?

At the end of the operation, wires are used to pull the breastbone

together and hold it firm for healing – these are not usually removed. It sounds as though you are one of the small number of people who feel the ends of these wire stitches. This may settle down or only be an occasional problem; however, occasionally they can give trouble. The problem can usually be pinpointed by pressing with a finger. If this problem occurs, the wires can be removed under anaesthesia by your surgeon, because once the breastbone has healed the wires are no longer necessary.

My chest scar is pink and overgrown, following my bypass operation. Can it be improved?

Occasionally, an operation scar may become pink and enlarges like a ridge. This is known as a keloid. It can be tender, itchy and unsightly. If it is a problem, steroid creams can be tried in order to relieve the discomfort. If it is intolerable, the scar can be cut out and then deep X-ray treatment given to stop the skin cells enlarging again.

I am due out of hospital in a few days after a successful bypass operation. What problems might I have?

Most people go straight home providing there is someone there to help. If you live alone, it is best to spend the first 2 weeks with relatives or friends but, if this is not possible, your doctor should arrange, preferably before the operation, for your convalescence in a convalescent home. You will be given a supply of painkillers, a letter for your family doctor and advice on aspirin, diet and cholesterol medication. If you suffered from high blood pressure beforehand, this usually returns after the operation and will need careful checking. Almost certainly your blood pressure medications will need restarting.

When you return home, you may feel tired for a week or two. Although you are not exerting yourself, your body is doing a lot of repair work during this time.

How will I know that my bypass operation has been successful?

Your angina will be much less or non-existent. You will be less short of breath and have much more energy. You may say to yourself, ‘I didn’t realise how tired I had been’, as you discover a new lease of life. A bypass should be a new start for you and your heart.

What exercise can I do on leaving hospital after my bypass operation?

Regarding exercise, you can do what you like within the bounds

of commonsense! Unless carried to extremes, exercise will not hurt you. Any excess exercise will simply make you feel exhausted, and you can use this as a sign by which to pace yourself as you regain your fitness. In fact, regular exercise is an important factor in rehabilitation (see Chapter 10).