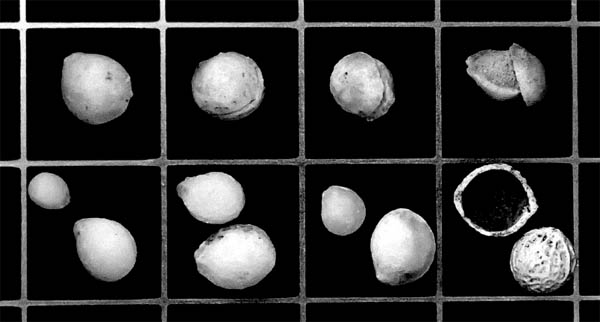

5.1. Hackberry endocarps, including specimens from the Brule Formation of Wyoming (top row and lower left three squares on the bottom row), and modern specimens (lower right square). The fossil endocarps are typically nearly smooth, with only a trace of the reticulation pattern seen in the modern specimens. The fossil endocarps occur in at least two size ranges. The original calcite shells have been recrystallized into coarse calcite crystals. The endocarps have two outer shells of calcium carbonate that can separate. The top row of fossils shows a progression from a complete endocarp (upper left) to an almost completely separated pair of shells (upper right). Grid in centimeters. Photo by the authors.

The sheer abundance and diversity of the paleontological record within the White River Badlands is indeed impressive. This has been well documented by the extensive amount of scientific literature that has been published on this region over the past 150 years. As a result, the fauna of the Big Badlands has played a key role in our understanding of how the North American biota has evolved and adapted in response to climatic change. The enormous depth of this topic has forced us to set some limits. The systematic discussions of paleontology are limited to taxa that have a published occurrence within a 100-mile radius of the Cedar Pass Area within Badlands National Park. However, many of the images featured in the systematics chapter come from areas outside the scope of this project but are of the same genus and species found in published records for Badlands National Park and the surrounding region.

During our research, we encountered some contradictory systematic classifications. This reflects the dynamics of the ongoing paleontological research with regard to the evolution, taxonomy, and systematics of the fossil taxa we include. We followed the most current publications whenever possible. For many taxa, there is a general agreement on the name that should be used for a taxon, but this is not always the case. We were thus forced to select a name. We emphasize that this is not a formal taxonomic revision and that our selection of names was often a matter of convenience to facilitate our ability to convey information. In those cases we have often selected historic names that are well established in the literature rather than more obscure names or newly proposed replacement names, which have not yet been fully accepted or vetted by the professional paleontological community. We realize that research is ongoing and that systematic classifications will continue to change in the coming years. To those specialists in different taxonomic groups who may disagree with our name choices, we apologize if our taxonomy does not exactly match your preferences.

Because of the highly alkaline oxidizing soils, the plant record within the White River Badlands is poor (Retallack, 1983b). There is no record of fossil leaves or pollen. Instead, we find root traces, the endocarps of hackberry seeds (Chaney, 1925), petrified wood (Troxell, 1925; Berry, 1926; Wieland, 1935; Lemley, 1971), and partially digested plant material in herbivore coprolites (Stovall and Strain, 1936). Even with such a limited record, important interpretations about the vegetation communities on the landscape and how they reflect the paleoclimate can be made from these materials.

There is a broad variety of fossil root traces preserved within the White River Group (Plates 6, 7). Root traces are an important indicator of pedogenic activity (soil formation) and are discussed in detail in chapter 3. They can also be an important indicator of ancient climate. According to Retallack (1983b), within a root trace, there is no evidence of original organic material nor any details of anatomy or surface detail. They are simply an opening in the soil left by the root and later filled with soil material or crystalline calcite or chalcedony. The root traces taper and branch downward and are irregular in width and direction, depending on the root structure of the original plant. Some of the most striking root traces are large metaisotubules of reddish clay washed into the yellowish C horizon of the type Yellow Mounds silty clay loam paleosol of the Pierre Shale and Fox Hills Formation. These root traces are up to 3 cm in diameter and indicate the presence of trees or large shrubs. In contrast, fine root traces of 1 to 2 mm are abundant on the surface of all paleosols of the White River and Arikaree groups and are comparable to those of modern prairie grasses and forbes. They don’t reach the density or deep development of root systems of a modern tallgrass prairie but are more similar to a mixed or short-grass prairie (Retallack, 1983b).

5.2. Permineralized (petrified) wood from the Chamberlain Pass Formation near Weta, South Dakota. Note the well-preserved ring structure, which is suggestive of seasonality, as well as the detailed preservation of wood grain. The nonuniform shape of this specimen suggests partial decomposition before burial and fossilization. (A) Cross-sectional view. (B) Long view. (C) Complete specimen. Scales in (A) and (B) are in centimeters. Penny for scale in (C). Photos by the authors.

Chaney (1925) was the first to report the presence of endocarps of hackberry seeds (Celtis hatcheri), which is a plant part much like a stone of a peach (Fig. 5.1). Hackberry seeds are common in many paleosols within the Chadron Formation and the Scenic and Poleslide members of the Brule Formation. Their preservation is due to the large amounts of biogenic calcium carbonate and silica deposited in the plant tissue (Retallack, 1983b). They are easy to identify because of the distinct wrinkled appearance of their outer surface.

The petrified wood found in the White River Badlands is mostly silicified and comprise the remains of dicotyledonous angiosperms (Troxell, 1925; Berry, 1926; Wieland, 1935; Lemley, 1971) and hackberry bushes (Fig. 5.2A) (Chaney, 1925). Stumps and fossil wood are rare but occur in the Chadron Formation and Scenic Member of the Brule Formation in the Badlands.

Animals that lack an internal skeleton composed of hydroxyapatite and lack a vertebral column are called invertebrates (Buchsbaum, 1977). The invertebrate fossil record within the White River Badlands is not well described because the fossils are poorly preserved and have a limited occurrence. However, a few valuable references can be found on the topic (Fig. 5.3) (Meek, 1876; White, 1883; Wanless, 1923). Mollusks, because of their hard shell of calcium carbonate, compose the majority of invertebrate fossils found within the White River Group. Other invertebrates are represented by tracks and traces.

5.3. Freshwater mollusk shells (A–E) and land snails (G–K) known from the White River Group of the Big Badlands. (A) Steinkern of a unionid bivalve from a channel deposit in the Poleslide Member. An outline of the reconstructed left valve is shown. (B) Diagram of the shell of Stagnicola shumardi from the Brule Formation. (C) Diagram of the shell of Physella secalina from the Brule Formation. (D) Diagram of Promenetus nebrascensis from the Brule Formation. (E) Diagram of Gyraulus sp. from the Brule Formation. (F) Series of diagrams of fossil gastropod shells showing the relative sizes of the various genera. (G) Side and apertural views of the type specimen of “Helix” leidyi Hall and Meek, 1855 (AMNH 11174/1, figured in Evanoff and Roth, 1992:figs. 1 and 2). This specimen was collected by Meek or Hayden in 1853 from the “turtle–Oreodon beds” (Scenic Member) in the headwaters of Bear Creek. It is the only known specimen from the Badlands of this species. (H) Apertural and side views of a nearly complete specimen of Skinnerelix leidyi from Chadronian rocks near Douglas, Wyoming (from Evanoff, 1990b:plate 1, fig. 5b and c; UCM 30736, University of Colorado Museum of Natural History, Boulder, Colorado, U.S.A.). (I) Spiral, apertural, and side views of Helminthoglypta sp. from the Brule Formation of northern Nebraska. (J) Diagram of Gastrocopta (Albinula) sp. from the Brule Formation. The apertural barriers are not known for this species. (K) Diagram of Pupoides (Ischnopupoides) sp. from the Brule Formation. Only well-preserved specimens of Ischnopupoides will show the fine radial ridges.

The Mollusca is the second largest phylum in the Kingdom Animalia on the basis of the number of living species. Mollusks live in all possible environments on the surface of the Earth, from the greatest depths of the sea to the highest mountains, and from the Arctic through the tropics to the Antarctic. It is one of the few phyla that have a greater number of fossil species than modern species. The fossil mollusks of the White River Group include the shells of freshwater mussels (clams), freshwater snails, and land snails. All three have relatively thin aragonite (mother-of-pearl) shells that either are recrystallized into calcite or are dissolved away, leaving only internal molds. There has not been a dedicated systematic analysis of the mollusks of the White River Group in the Badlands, but their fossils are locally common. The following taxa represent the most abundant or historically important fossil mollusks in the Badlands.

Freshwater mussels are large clams with relatively thin shells of mother-of-pearl, containing complex hinge teeth with multiple grooves and ridges (Fig. 5.3A, B). As with all bivalves (clams and their kin), the hinge teeth lock the shells together when the clam closes its shell, preventing the shells’ separation by twisting apart. Freshwater mussels thrive in clean, perennial, well-oxygenated running water. Their larvae disperse by attaching onto the gills and fins of fish that transport the larvae through the river system. The larvae eventually drop off the fish and settle on the bottom of the channel. When they are found in the rock record, they indicate that the stream or river that deposited the channel was perennial; had fairly clear water; and was connected with other drainages that allowed the fish (and thus the mussels) to disperse.

The White River freshwater mussels are typically found within the coarse-grained channel deposits of the White River Group. They indicate that the streams flowed throughout the year and were part of a connected tributary system. They are not found in all paleochannel deposits in the White River Group, and their absence indicates that these streams were intermittent and did not flow beyond the Great Plains. They can occur in fine-grained deposits next to the channels (Gries and Bishop, 1966) where floods transported the clams into the surrounding floodplains. The mussels also occur in some lacustrine limestone deposits along with fish fossils (Wanless, 1923). The lakes must have had connections with the river systems, allowing the fish with their attached mussel larvae to enter the lake.

Gries and Bishop (1966) described some internal molds (also called steinkerns) of unionid bivalves from the Chadron Formation in the Indian Creek drainage just outside Badlands National Park. The fossils are preserved in a calcareous claystone, possibly representing a “quiet backwater of a sluggish stream” (Cook and Mansfield, 1933:265), and were probably brought in from a river channel by floods (see Hanley, 1987, for a description of the process). The unionid bivalves described by Gries and Bishop (1966) have not been identified to genus because such an identification would require details of the shell not preserved in these specimens. At the time of this writing, all of the unionid bivalves found within the White River Group are internal molds, making a more specific identification impossible.

Pulmonates are lung-bearing snails that can breathe oxygen from the air and are extremely drought tolerant. The pulmonates include many freshwater snails (Basommatophora) and most land snails (Stylommatophora). Both groups have thin shells made of aragonite that are typically recrystallized to calcite or are dissolved away, leaving internal molds. Fossil pulmonates range from the Triassic to the Recent (Evanoff, Good, and Hanley, 1998).

The freshwater pulmonate snails can live in waters containing low oxygen, turbid waters, or waters containing a high amount of suspended sediment, as well as standing water that seasonally dries (intermittent waters). The fossil freshwater snails of the Big Badlands are all pulmonates, including the high-spired shells of the lymnaeid Stagnicola and the extremely low-spired shells of the planorbids Gyraulus and Promenetus. All of these are easily transported to open waters by birds, where a single snail can start a population because these snails can self-fertilize by a process called hermaphroditism. Early Eocene snail faunas were dominated by gill-bearing snails (the prosobranchs), which require perennial, clean, well-oxygenated waters like that in the eastern United States and the Pacific Northwest. By the time of White River Group deposition, rivers and ponds were much more intermittent and turbid, an environment only the pulmonates could withstand. Turbidity was probably the greatest controlling factor in favoring the pulmonates during the late Eocene and early Oligocene. The snails probably lived in semipermanent ponds and longer-lasting small lakes on the floodplains away from river channels, living on abundant freshwater algae whose photosynthesis helped to precipitate calcium carbonate in the water. All the freshwater snails found in the White River Group in the Badlands have descendants living today in South Dakota (Beetle, 1976). The following descriptions of the modern geographic ranges are from Burch (1989), which is an excellent reference for modern freshwater snail shells. The fossil freshwater snails of the White River Group were summarized by Meek (1876) and White (1883).

Systematics and Evolution The type species of Stagnicola is Buccinum palustre Müller, 1774.

Distinctive Characters The adult shells of the fossil taxa are medium to small, elongate, spindle-shaped shells with slightly inflated whorls; the shell surface is smooth or sculptured with microscopic spiral striations; the columella (the central shaft of the shell) has a well-developed twist or plait (Burch, 1989; Evanoff, 1990b).

Stratigraphic and Geographic Distribution Stagnicola is a geographically widespread genus that occurs throughout North America, Asia, and Europe. Stagnicola elodes, the marsh pond snail, lives in South Dakota today (Beetle, 1976). Fossils of Stagnicola can be found in rocks ranging in age from the Jurassic to Recent (Evanoff, pers. obs.).

Two species of Stagnicola have been described from limestone beds in the Chadron Member near Poeno Spring, north of Badlands National Park (Fig. 5.3C–F). The larger form is S. meeki (Evans and Shumard) 1854, and the smaller form is S. shumardi (Meek) 1876. Both are typically found in thin sheet limestone beds deposited in shallow lakes and ponds. Stagnicola meeki is only known from limestone beds of the Chadron Formation, while S. shumardi occurs in limestone beds extending from the Chadron through the lower Poleslide Member of the Brule Formation in South Dakota. Stagnicola is the most common freshwater snail within the White River Group.

Systematics and Evolution The type species for Gyraulus is the living Planorbis albus Müller, 1774.

Distinctive Characters The adult shells of Gyraulus are small discoidal shells with rapidly expanding whorls forming a distinct umbilicus away from the spire, and a shallow umbilicus on the spiral side. An umbilicus is a depression formed on the spiral axis of the shell by the whorls expanding away from the axis of coiling. The outer margin of the shell is rounded; the shells are typically smooth. The margin can be circular in cross section or can be slightly elongated laterally and away from the spiral side (Burch, 1989).

Stratigraphic and Geographic Distribution Gyraulus is geographically widespread, occurring throughout North America, Asia, and Europe. There are two species of Gyraulus that live in western South Dakota, G. circumstriatus and G. parvus (Beetle, 1976). Fossils of Gyraulus occur in rocks ranging in age from early Jurassic to Recent (Evanoff, Good, and Hanley, 1998). Gyraulus leidyi (Meek and Hayden, 1860) was described from limestone beds in the Chadron Formation near Poeno Spring, north of Badlands (Fig. 5.3G, H). This fossil snail occurs in pond and shallow lake limestone beds within the Chadron Formation through the lower Poleslide Member of the Brule Formation in Badlands National Park.

Systematics and Evolution The type species of Promenetus is Promenetus exacuous (Say, 1821).

Distinctive Characters Adult shells of Promenetus are small lenticular–discoidal shells characterized by a distinct angular margin called a carina. The tip of the carina is not far below the midline of the coiled shell. The shell has an umbilicus on both sides of the shell, but the spire side has a shallower umbilicus. The shell is typically smooth (Burch, 1989; Evanoff, 1990b). Promenetus nebrascensis has a rounded, indistinct carina, while P. vetulus has a distinct, angular carina (similar to what differentiates the shells of P. exacuous from P. umbilicatellus today).

Stratigraphic and Geographic Distribution Fossils of Promenetus range from the early Eocene to the Recent (Hanley, 1976). Promenetus nebrascensis (Evans and Shumard) 1854 and P. vetulus (Meek and Hayden) 1860 are two fossil species that were first collected in the Chadron Formation near Poeno Spring north of Badlands National Park (Fig. 5.3I–L). Promenetus species occur in thin limestone beds deposited in pond and shallow lake environments ranging from the Chadron Formation through the lower Poleslide Member.

Natural History and Paleoecology Promenetus is widespread in quiet freshwater environments of the western United States, and two species, Promenetus exacuous and P. umbilicatellus, live in quiet freshwater environments of South Dakota (Beetle, 1976).

The fossil land snails in the Badlands are all pulmonates and include both snails with large shells (shell heights larger than 10 mm) and very small shells (microshells that are less than 5 mm high). All fossil land snails are identified by the form and size of their shells. The larger shells also have microsculpture on the shells, including small granulations and fine spiral grooves, that can help identify the snail to the family level. The microshelled snails typically have small knoblike barriers in the apertures that are unique for genus and species identifications. All of the known fossil lands snails from Badlands can be identified to the family level of snails now living in North America. Most can be classified to modern genera and in some cases to modern subgenera. All the known fossil land snails in the Badlands occur in the Brule Formation.

No systematic study of the fossil land snails of the White River Group in Badlands has been made, so the following list, based on the observations of snail shells recently collected during the various projects in the field, is rudimentary. Though fossil land snails can be used as biostratigraphic and climatic indicators for the late Eocene and early Oligocene (Evanoff, Prothero, and Lander, 1992), not enough is known about the fossil lands snails at Badlands to make such interpretations.

Systematics and Evolution The type species of Skinnerelix is Helix leidyi Hall and Meek, 1855.

Distinctive Characters Skinnerelix is a large land snail (Fig. 5.3M, N) characterized by a globose–conic shell with a narrow-flared aperture opening and a coarse growth lines with a coarse, granular microsculpture. Skinnerelix has a shell almost identical to the modern Humboltiana except Humboltiana does not have a flared aperture opening.

Stratigraphic and Geographic Distribution Skinnerelix is known almost exclusively from Chadronian (upper Eocene) rocks except for the type specimen. For a complete discussion on Skinnerelix leidyi, see Evanoff and Roth (1992).

Helix leidyi was the first fossil land snail species to be described from the western United States. A single slightly crushed specimen (AMNH 11174/1; Fig. 5.3) was collected during the Meek and Hayden expedition to the Badlands in 1853. The specimen came from the head of Bear Creek (in the Scenic basin) from the “turtle–Oreodon” layer (Hall and Meek, 1855) now known as the Scenic Member of the Brule Formation. The specimen is large and globose, and it retains some recrystallized shell just behind the crushed body whorl that has the characteristic coarse granular microsculpture. If this specimen came from the Scenic Member, then it is the only known specimen of Skinnerelix of early Oligocene age. Unfortunately, no other specimens have been found in the Badlands of South Dakota.

Natural History and Paleoecology Humboltiana typically lives on a variety of substrates and woody vegetation, ranging from oak forests on limestone to high coniferous forests and mixed, scattered woodlands on volcanic rocks (Pilsbry, 1939). Humboltiana now has a geographic range from west Texas south to central Mexico.

Systematics and Evolution The type species of Helminthoglypta is the modern Helix tudiculata Binney, 1843.

Distinctive Characters The fossil shells of Helminthoglypta in the Badlands are medium to large size; typically with low spires and moderately inflated whorls; and with fine granular microsculpture oriented in rows oblique to the growth lines. The microsculpture can also include spiral incised lines; the umbilicus is quite narrow. The aperture is flared but narrow and is rarely preserved.

Stratigraphic and Geographic Distribution The geologic range of the genus Helminthoglypta is from Chadronian (late Eocene) to Recent (Evanoff, 1990b). In the Badlands, they are known from the Scenic through the lower Poleslide members of the Brule Formation.

Natural History and Paleoecology The 88 modern species of Helminthoglypta live in forests, shrub lands, and woodlands from southwestern Oregon south to northern Baja California and west of the Cascade and Sierra Nevada mountains. Helminthoglypta is the most abundant large fossil land snail from the Badlands. Their thin aragonite shells are always recrystallized into calcite, but most specimens are represented by internal molds. Typically mistaken for “Helix leidyi,” these snail shells are distinct from Skinnerelix leidyi by their smaller size, lower spire, less inflated whorls, and fine granular and spiral groove microsculpture when the shells are preserved. The genus may be represented by several currently undescribed species that may be distinguished by size, form, and details of shell microsculpture.

Systematics and Evolution The type species for Gastrocopta is the modern Pupa armifera Say, 1821.

Distinctive Characters Shells of Gastrocopta, subgenus Albinula, are small (less than 5 mm long) and oval, and have flared rounded apertures. Gastrocopta shells have many short knoblike barriers in the aperture, with the middle barrier on the spire side of the aperture characteristically long and split at the end (bifid). Gastrocopta (Albinula) has the largest shells of all the Gastrocopta species, with shell lengths as great as 4.5 mm (Metcalf and Smartt, 1997). The fossil Gastrocopta (Albinula) shells of the Brule Formation in Badlands is essentially identical in form and size to Gastrocopta armifera, but the apertural barrier forms and arrangements in the fossils are currently unknown.

Stratigraphic and Geographic Distribution Pupa armifera is widespread east of the Rocky Mountains and lives today in western South Dakota (Beetle, 1976). Gastrocopta (Albinula) shells occur in the Scenic and lower Poleslide members of the Brule Formation in the Badlands. The range of the genus and subgenus is Chadronian (late Eocene) to Recent (Evanoff, 1990b).

Systematics and Evolution The type species for Pupoides (Ischnopupoides) is Pupa hordacea Gabb, 1866.

Distinctive Characters Shells of Pupoides, subgenus Ischnopupoides, are all very small (less than 3.5 mm in length) and cylindrical, with an oval aperture that is thickened and expanded but not flared. The aperture contains no knoblike barriers. The outer whorls can be smooth or can have thin, fine ribs parallel to the growth lines. The shell of Pupa hordacea has fine ribs like most White River fossils of this subgenus (Evanoff, 1990b).

Stratigraphic and Geographic Distribution Pupoides (Ischnopupoides) now lives in the Colorado Plateau and eastern foothills of the Rocky Mountains as far north as Douglas, Wyoming (Evanoff, 1990b). They live in dry locations typically in association with shrubs (Evanoff, 1983). Its geologic range is Chadronian (late Eocene) to Recent (Evanoff, 1990b), but it is only known from the Scenic and lower Poleslide members of the Brule Formation in the Badlands.

The majority of fish material from the White River Badlands is represented by catfish pectoral spines and some unidentified ganoid scales (Lundberg, 1975; Clark, Beerbower, and Kietzke, 1967). There are a few rare occurrences where cranial material has been preserved but none of this material has been identified to species (Lundberg, 1975). In North America, the majority of high-quality Tertiary fish fossils are limited to the quiet, low-energy lacustrine deposits of the Eocene and the Miocene through the Pleistocene (Lundberg, 1975), such as those found in the Eocene Green River Formation. Lacustrine deposits within the White River Badlands that might preserve whole fish skeletons are extremely rare.

Systematics and Evolution The type species of the catfish Ictalurus (Ictalurus) is Silurus punctatus Rafinesque, 1818, later transferred to Ictalurus by Rafinesque in 1820. Cope (1891) described three species of catfish on the basis of vertebrae from the lower Oligocene Calf Creek fauna in the Cypress Hills Formation of Saskatchewan: Rhineastes rhaeas (now I. rhaeas [Cope]), Ameiurus maconelli, and A. cancellatus, now all considered to be I. rhaeas (Lundberg, 1975). There are no specimens from Badlands National Park that are identified to species.

Distinctive Characters Modern ictalurids are distinguished from all other living siluriforms (catfish) by having a massive jaw adductor muscle originating on the skull roof (Lundberg, 1975:45). The oldest known ictalurid showing this character is from the Brule Formation, in Jackson County, South Dakota. Both of the known Oligocene fossil catfish, Ictalurus rhaeas and Ameiurus pectinatus, are assigned to their respective modern genera on the basis of features of the pectoral spine in the former and features of the ventral surface of the skull in the latter.

The pectoral spine shaft in large individuals is ornamented with prominent but narrow, subparallel ridges and deep grooves. On small individuals, the spine shafts are finely striate, and the anterior ridge is prominent and shows traces of regular spaced anterior dentitions. The posterior dentitions in small individuals are uniformly spaced, evenly retrorse, and single cusped (Lundberg, 1975).

Stratigraphic and Geographic Distribution Fossilized remains from Ictalurus can be found in deposits from the Paleocene to Recent (Lundberg, 1975). Ictalurus fossils are found in South Dakota, Saskatchewan, Kansas, Texas, Nebraska, Florida, Oklahoma, Ontario, Mexico, Montana, Colorado, Wyoming, Pennsylvania, Oregon, Idaho, and North Dakota. At Badlands National Park, Ictalurus specimens are found in the Poleslide member of the Brule Formation in the South Unit of the park.

Natural History and Paleoecology The fossil Ictalurus from the Big Badlands probably had a diet similar to modern catfish, including smaller fish, crayfish, mollusks, and plant material (Grande, 1984). Modern catfish also prefer fluvial environments such as streams and rivers, which do not usually have high-quality preservation or articulated remains. Today, native populations of fossil catfish in North America are only found in river drainages east of the continental divide, although fossils are known from the western side of the divide from the Eocene deposits of the Green River Formation in Wyoming and from the Pliocene Glenns Ferry Formation in Idaho. Living catfish are temperature sensitive, and their northern limits are determined by the length of the growing season or, conversely, limited by the length of winters. Warm-water fishes like catfish living in temperate climates can tolerate temperatures close to 0°C for several months. They do, however, require a growing season sufficiently long enough and warm enough (measured in degree-days) to reach sufficient size, with sufficient stored reserves, to survive through the winter into the next growing season (Smith and Patterson, 1994). Their presence in the White River Group supports the idea of generally warmer temperatures throughout the year, or at least mild or short winters

Sediments in the White River Badlands indicative of swamp or marsh habitat are almost nonexistent. Because these areas often are the preferred environments for amphibians, their fossils are extremely rare members of the fauna. There is no record of the Order Caudata or fossil salamanders from the White River Group in western South Dakota. Ambystoma tiheni is present in the late Eocene Calf Creek Fauna in Saskatchewan, Canada (Holman, 1972). The record of Ambystoma continues into the Miocene in South Dakota, where they are fairly abundant. It is difficult to say whether fossil salamanders lived in the White River Badlands or if they were simply not preserved. Hutchison (1992) notes a reduction in the North American amphibian fauna during the Oligocene as a result of increasing aridity. Ambystoma tigrinum is found in South Dakota today.

The order Anura includes frogs and toads. The record of anurans in the White River Group is better than the salamanders but still quite limited. This group, especially frogs, would also be sensitive to increased aridity during the Oligocene, but perhaps not as extremely sensitive as the salamanders. The specialized modes of swimming and jumping in frogs and toads distinguish them from other amphibians, and this is reflected in the distinctive morphology of their skeleton, which makes them easier to identify. They also have feeding adaptations that allow them to swallow relatively large prey species whole (Holman, 2003).

Although fossil frogs are fairly rare, the pelobatid frogs are some of the most common frogs found in the fossil record (Estes, 1970b). The family is defined by the following characters: procoelous vertebrae, imbricate neural arches, arciferal pectoral girdle, single coccygeal condyle, prominent sternal style, wide dilation of sacral diapophyses, and long anterior and short posterior transverse processes of the vertebrae (Estes, 1970b).

Systematics and Evolution The type species for Eopelobates is E. anthracinus from middle Oligocene lignite beds near Bonn, Germany (Parker, 1929). Zweifel (1956) described an early Oligocene North American species, E. grandis, on the basis of Princeton University No. 16441 (now housed at the Peabody Museum of Natural History, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut), a nearly complete skeleton lacking only some skull and distal limb bones (Fig. 5.4) from the early Oligocene middle part of the Ahern Member of Chadron Formation, Pennington County, South Dakota.

Distinctive Characters Eopelobates is defined by the following characters: prominent elongated external style, strong posterior projection of the ischium, spade absent, long, relatively slender limbs, urostyle either separate, partially or completely fused with the sacrum, sacral diapophyses strongly dilated, tibia longer than femur, approximately subequal orbit and temporal openings, dermal ossification well developed and fused to the skull roof, skull roof flat or concave dorsally, ethmoid wide and blunt anteriorly, squamosal–frontoparietal connection absent, and femur–tibia length approaching or exceeding head–body length (Estes, 1970b).

Stratigraphic and Geographic Distribution Fossilized remains from Eopelobates can be found in the late Cretaceous through the late Eocene. Eopelobates was believed to be Holartic in its coverage by the early Eocene (Estes, 1970b). Eopelobates grandis was described from the late Eocene Chadron Formation from Shannon County, South Dakota (Clark, Beerbower, and Kietzke, 1967), and in Pennington County, South Dakota (Holman, 2003).

Natural History and Paleoecology The various species of the genus, Eopelobates have proven to serve as strong climatic indicators. As fossils, they are known from deposits from the humid, subtropical environment of the late Cretaceous to a warm, temperate environment of the late Eocene (Estes, 1964). Eopelobates grandis is found in late Eocene sediments (Chadronian) and is associated with a more temperate climate. The deterioration of climate during the Eocene–Oligocene transition not only caused the eventual extinction of Eopelobates but also gave rise to the more temperate spadefoot toad line (Estes, 1970b). Close relatives of this frog now inhabit the lowlands of Indonesia and southern China, and the upland forests of the southeastern Tibetan Rim (Clark, Beerbower, and Kietzke, 1967).

5.4. Eopelobates grandis. Skeleton courtesy of the Division of Vertebrate Paleontology, YPM VPPU 16441, holotype, Peabody Museum of Natural History, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut, U.S.A. Scale in centimeters. Photo by Ethan France, Peabody Museum of Natural History.

The record for reptile vertebrate fossils within the White River Badlands is sparse. The only exception is the fossil turtles, which occur in great abundance. The majority of reptilian fossils occur as scattered bone or jaw fragments, while complete shells of turtles are often preserved.

The turtles within the White River Badlands are some of the most common fossils found. Hayden (1858) coined the term “turtle–Oreodon layer,” which was characterized by the abundance of turtles and oreodont fossils at the base of the Scenic Member within the Brule Formation. Both land tortoises and aquatic turtles are found within the White River Group, with the former being much more abundant. Of the land tortoises, Stylemys nebrascensis is by far the most common (Fig. 5.5). Described by Joseph Leidy in 1851, it is the first fossil tortoise documented in North America (O’Harra, 1920; Hutchison, 1996). The thick, high-domed shell of Stylemys lends itself well to preservation within the Badlands strata. Unfortunately, the skull and limb elements are rarely preserved. Shell sizes range from about 100 mm to over 530 mm in length. The aquatic turtles have flatter and more delicate shells and hence are not as well preserved.

Hutchison (1991) characterized the family as having moderately broad plastron lobes. The plastron is 67 percent to 78 percent of the carapace length. The carapace is distinctly tricarinate to smooth. It contains six neurals.

Systematics and Evolution The type species of Xenochelys is X. formosa Hay, 1906, from the Chadron Formation in Shannon County, South Dakota.

Distinctive Characters The carapace of Xenochelys can be as large as 208 mm in length. The plastron is about 82 percent of the carapace length. The plastron and carapace are relatively thin to moderately robust. The perimeter length of the nuchal is no longer than any peripheral. There is a well-developed caudal notch between the two halves of the xiphiplastron (Hutchison, 1996).

Stratigraphic and Geographic Distribution Fossilized remains from Xenochelys can be found in the Wasatchian through the Chadronian. Fossils are found in South Dakota and Wyoming.

Natural History and Paleoecology Clark, Beerbower, and Kietzke (1967) noted that the aquatic turtles are rare and not well preserved but were important climatic indicators. Xenochelys did not make it past the Eocene–Oligocene boundary, probably as a result of the cooling and drying trend found in the Oligocene.

The trionychids, also known as the soft-shelled turtles, can be traced back to the late Cretaceous. They show a sharp increase in size in the Bridgerian and then begin to decrease in diversity. They disappear from the geologic record in the Badlands and western North America in the earliest Orellan, but the living form, Apalone spinifera, is found in the eastern United States. The family is broadly distributed today, and members of this family occur in Africa, Asia, North America, and Southeast Asia, indicating a southern or eastern refugium during the Oligocene and early Miocene (Hutchison, 1992; Estes, 1970a).

Systematics and Evolution The type species for Apalone is the living Florida soft-shelled turtle, originally Trionyx ferox (Schneider, 1783) but transferred to the new genus Apalone by Rafinesque (1832). The fossil species, A. leucopotamica, Cope, 1891, from the Cypress Hills, Saskatchewan, Canada, was originally placed in Trionyx. Meylan (1987) resurrected the genus Apalone for the North American forms, including the three extant species, and restricted Trionyx to certain soft-shelled species found mainly in Africa

Distinctive Characters The diagnosis for A. leucopotamica is as follows. The carapace can grow as much as 325 mm in length. The nuchal width ratio to carapace width ratio is about 0.6. The carapace length to width ratio is about 0.9. The costal margins are tapered, and the carapace is truncated posteriorly (Hutchison, 1998). Hay (1908:537) gave the diagnosis for A. leucopotamica as the only Oligocene species of Apalone. He also describes the carapace as “thin broader than long; nuchal 0.6 the width of the carapace; a fontanel on each side of first neural.”

Stratigraphic and Geographic Distribution Fossilized remains from Apalone can be found in the Chadronian through the Orellan. Fossils are found in South Dakota, Nebraska, North Dakota, and Saskatchewan. In the White River Badlands, Apalone is found in the Chadron Formation. Today the genus is represented by a single species in North America, Apalone spinifera, with a distribution from central-eastern United States (western New York and southern Carolina) to Wisconsin and from Minnesota and southern Ontario as far south as Mexico.

Natural History and Paleoecology Modern soft-shelled turtles are entirely aquatic. An active predator, they are fast in the water. Because of a marked sexual and morphological variation in the carapace, Hutchison (1998) concludes that the group needs major taxonomic revision.

The emydids (pond turtles) can be traced back to the early Eocene. They show a sharp increase in size in the Uintan, followed by a decrease. They also disappear from the geologic record in the Badlands in the earliest Orellan. The family appears to also be sensitive to cooling and drying trends, which has profoundly affected their distribution (Hutchison, 1992; Estes, 1970a). They are characterized by a low domed shell, the absence of a musk duct foramina, and a weak or absent caudal notch. There is only a slight nuchal overlap and little or no anterior constriction (Hutchison, 1996).

Systematics and Evolution The type species for Pseudograptemys is P. inornata (Loomis, 1904) and includes Graptemys cordifera. The type specimens were collected, respectively, in the Chadron Formation, from Pennington and Shannon counties, South Dakota.

Distinctive Characters The carapace is unsculptured except for traces of a low, rounded median keel. The posterior peripherals are notched at the marginal sulcus. The hypoplastron buttress is well developed and articulates with costal 5. The xiphiplastron ends are distinctly pointed (Hutchison, 1998).

Stratigraphic and Geographic Distribution Fossilized remains from Pseudograptemys can be found in the Chadronian. Fossils are found in South Dakota. The genus Graptemys is considered to be the closest living relative of the fossil form.

Natural History and Paleoecology The extant map turtle Graptemys provides the closest relative for comparison to the fossil genus Pseudograptemys. Map turtles are freshwater turtles restricted to river systems in the eastern United States (Wood, 1977). Most of the modern species have some temperature constraints and are only found in the warm rivers of the southern United States. A few species have a more northern distribution, occurring in rivers that regularly freeze in the winter. Graptemys is also limited to temperate regions. Of the nine living species, seven are described as carnivores. It appears that Graptemys and Pseudograptemys were influenced by climatic and physiographic changes throughout the geologic record (Wood, 1977).

Systematics and Evolution Chrysemys antiqua Clark, 1937, was found in the Chadron Formation in Pennington County, South Dakota. The type specimen of C. antiqua is YPM PU 13839.

Distinctive Characters The carapace is of moderate size (to 190 mm), is moderately domed with or without sculpture, lacks keels, and has a sharp but moderately incised sulci. The anterior nuchal margin is straight to moderately concave (Hutchison, 1996:343).

Stratigraphic and Geographic Distribution Chrysemys antiqua is found in the Chadron Formation in Pennington County, South Dakota. It is also found in Colorado, Nebraska, and North Dakota. Chrysemys antiqua is found in the Chadronian through the Whitneyan. The genus Chrysemys ranges from the Oligocene through the Recent.

The family Testudinidae includes the most common turtles within the White River Group (Hay, 1908; Hutchison, 1992, 1996), and they occur throughout the section. First appearing in the Wasatchian, they increase in size in the Bridgerian and then tend to decrease in size into the Orellan in response to lower precipitation levels and cooler temperatures (Hutchison, 1992). Four tortoise genera have classically been assigned to this family. Two of the genera, Testudo and Geochelone, are now restricted to non–North American taxa (Williams, 1952; Preston, 1979; Hutchison, 1996). Hesperotestudo, Stylemys, and Gopherus are still used for the tortoises from the White River Group and will be discussed here.

Systematics and Evolution The type species of Hesperotestudo is H. brontops Marsh, 1890. The type specimen was collected from the Chadron Formation in Pennington County, South Dakota.

Distinctive Characters Hesperotestudo is characterized by a reduced or absent premaxillary ridge. There is no symphyseal dentary groove. The costals alternate from narrow to wide laterally. Hesperotestudo has a moderate to short tail and caudal vertebrae with interpostzygapophyseal notches. The armor on the forelimbs is moderately to well-developed with a patch of sutured dermal ossicles on the thigh and perhaps tail in adults. The nuchal scale is longer than wide (Hutchison, 1996:345).

Stratigraphic and Geographic Distribution Hesperotestudo occurs in the Chadron and Brule formations of the White River Badlands of South Dakota.

Systematics and Evolution The type species of Stylemys is S. nebrascensis Leidy, 1851. The type specimen was collected from the Scenic Member, Brule Formation, in South Dakota.

Distinctive Characters Unfortunately, the majority of defining features for the genus Stylemys relate to the skull, dentary, and pes structures, which are rarely preserved. Hay (1908) proposed many shell features that later were linked to ontogenetic changes (Auffenberg, 1964). One shell feature used to define the genus Stylemys is that the costals (bones of the carapace derived from ribs) only slightly alternate between narrower and wider width laterally (Fig. 5.5), in contrast to Gopherus, in which they distinctly alternate between narrower and wider width laterally. Another shell feature is that the nuchal scale is longer than it is wide (Auffenberg, 1964, 1974; Hutchison, 1996). Some other defining features are as follows: premaxillary ridge present; a symphyseal dentary groove; a moderately long, unspecialized tail with some of the caudal vertebrae lacking interpostzygopophyseal notches; free proximal portion of the ribs long; and minimum of armor on forelimbs (Auffenberg, 1964, 1974; Hutchison, 1996).

Auffenberg (1962) described Stylemys nebrascensis as having a carapace as much as 530 mm or more in length; peripheral pits for reception of costal ribs; proportionally thicker and more rounded shell; weak lateral notch on xiphiplastron; anterior lobe of plastron wider than long; posterior length distinctly less than bridge length.

Stratigraphic and Geographic Distribution Fossilized remains from Stylemys can be found in the Chadronian through the Whitneyan. Fossils are found in Oregon, California, South Dakota, Nebraska, Utah, Texas, Wyoming, and Colorado.

Natural History and Paleoecology Stylemys was defined as an extinct Holarctic genus with a climatic range of temperate to subtropical (Brattstrom, 1961; Auffenberg, 1964). Fossil turtle eggs from the Oligocene of the Western Interior were described by Hay (1908:391) and on the basis of their macro-features were assigned to the genus Stylemys.

5.5. Stylemys nebrascensis. (A) Plastron. (B) Carapace. (C) Left lateral view (Leidy, 1853:plates 22, 24). Scale in centimeters.

Systematics and Evolution The type species for Gopherus is the living species, G. polyphemus, originally Testudo polyphemus Daudin, 1802, that today lives in the southeastern United States. The fossil form found in the White River Group is G. (Oligopherus) laticuneus Cope, 1873, the type specimen of which was collected from Weld County, Colorado.

Distinctive Characters Gopherus shares many diagnostic features with Stylemys. Some of these include premaxillary ridge present and a symphyseal dentary groove (Hutchison, 1996). In contrast with Stylemys, Gopherus has costals that distinctly alternate narrower with wider laterally, and the nuchal scale is wide or wider than long (Hutchison, 1996). Auffenberg (1974) includes the following additional features: short cervical vertebrae; flattened forelimbs adapted for digging; fourth vertebral scute usually wider than long.

Hutchison (1996) proposed the subgenus Oligopherus, characterized by the following features: the posterior epiplastron excavation is shallow; cervical vertebrae not appreciably shortened; pre- and postzygopophyses not elongated, widely separated; first dorsal vertebra with small zygopophyses and the neural arch structurally united with neural 1. The new subgenus included G. laticuneus, a better-known taxon.

Stratigraphic and Geographic Distribution Fossilized remains of Gopherus can be found throughout the White River Group in the Badlands. Beyond this area the time range of the genus is from Oligocene to Recent. The type of G. (Oligopherus) laticuneus, AMNH 1160, was found in Weld County, Colorado. Fossils are found in all of the Nearctic Region south of Canada and south throughout northern Mexico. Extant species are now limited to the southern United States and northern Mexico (Brattstrom, 1961; Auffenberg, 1974).

Natural History and Paleoecology The genus Gopherus includes the modern gopher tortoises, which are named for their ability to dig large, deep burrows. All four living species are found in xeric habitats.

Fossil members of the order Squamata (lizards and snakes) from central North America are best preserved and have their greatest diversity in the Orellan. In contrast, the squamates are much less diverse in the Chadronian and the Whitneyan. Overall, the squamatofauna of the Great Plains in North America are more primitive than originally thought (Sullivan and Holman, 1996). All of the fossil squamata found within the White River Badlands discovered to date are fossorial or ground dwelling (Maddox and Wall, 1998), features of their ecology that facilitated their preservation as fossils. Hutchison (1992) concluded that the increase in aridity and accompanying decrease in aquatic habitats during the Eocene–Oligocene transition had a greater impact on herpetofauna species diversity than a change in temperature. The squamate fauna within the White River Badlands seem to support Hutchison’s interpretation (Maddox and Wall, 1998).

Systematics and Evolution The type species for Peltosaurus is P. granulosus Cope, 1873. The type specimen was collected from the White River Formation in Logan County, Colorado.

Distinctive Characters Peltosaurus is characterized by seven teeth on the premaxillary and 10 teeth on the dentary. The parietal bone is broad and flat, and the frontals are greatly narrowed and united. The postorbital and postfrontal are coalesced, and the parietal is in contact with the squamosal (Fig. 5.6). The head and body are covered with unkeeled, finely granular scutes (Gilmore, 1928).

Stratigraphic and Geographic Distribution Fossilized remains from Peltosaurus can be found in the Orellan to Arikareean. Fossils are found in South Dakota, Nebraska, Florida, and Colorado. In the White River Badlands, Peltosaurus is found in the Brule Formation.

Natural History and Paleoecology Peltosaurus is the most common of all Oligocene “melanosaur” lizards and is known from numerous specimens (Sullivan and Holman, 1996).

Systematics and Evolution The type species of Helodermoides is H. tuberculatus Douglass, 1903. The type specimen is Chadronian and was found in Jefferson County, Montana.

Distinctive Characters Helodermoides is characterized by distinct frontals and a bulbous cephalic osteoderms. There are numerous tubercles without definite arrangement. Sometimes they are arranged in a ring shape. Six or seven rows of cephalic osteoderms occur between the orbits. The teeth are subconical and the posterior ones are slightly recurved. The jugal blade is curved and the maxilla is straight. The dentary is moderately slender and the supratemporal fenestra is closed. The skull is highly vaulted (Sullivan, 1979).

Stratigraphic and Geographic Distribution Fossilized remains from Helodermoides can be found in the Chadronian to Orellan. Fossils are found in South Dakota (Maddox and Wall, 1998), Wyoming, Montana, and Nebraska. In the White River Badlands, Helodermoides is found in the Chadron and Brule formations.

Natural History and Paleoecology Gilmore (1928) synonymized Helodermoides with Glyptosaurus. Sullivan (1979) resurrected the genus Helodermoides, describing numerous characters that separated it from Glyptosaurus and other glyptosaurs.

5.6. Peltosaurus granulosus. Skull, left lateral view, AMNH 8138. Scale in centimeters. Photo by the authors of a specimen from the American Museum of Natural History, New York, New York, U.S.A.

Systematics and Evolution The type species of Rhineura is R. floridana (Baird, 1859). Rhineura hatcheri (Baur, 1893) is the species found at Badlands National Park. The type specimen was found in Logan County, Colorado. According to Sullivan and Holman (1996), the various characters used by previous workers to diagnose species of Rhineura may not be valid for recognizing distinct genera. The size differences may be due to growth stages as opposed to character differences. The Oligocene Rhineura may be only known by one species, R. hatcheri. If R. floridana is a valid taxon, then the genus Rhineura would have a relatively long temporal range (Oligocene to Recent). It would be the only recent squamate genus represented in the early Oligocene squamatofauna (Sullivan and Holman, 1996).

Distinctive Characters Rhineura is characterized by a compact, well-ossified skull, with pleurodont teeth lacking the postorbital and postfrontal squamosal arches and epipterygoid (Gilmore, 1928).

Stratigraphic and Geographic Distribution Fossilized remains from Rhineura can be found in the Brule Formation of the White River Badlands. Fossils are found in South Dakota and Colorado.

The snake fauna of the White River Badlands is sparse and consists of a few taxa of boids, mostly small in size.

Systematics and Evolution The type species of Calamagras is C. murivorus Cope, 1873. The type of Calamagras is from the early Oligocene (Orellan) part of the White River Formation, Logan County, Colorado.

Distinctive Characters Calamagras has a short, thick neural spine on its vertebrae. The vertebral centra are less than 9 mm in length. The neural spine is less than one-half the total length of the centrum, but it is not tubular or dorsally swollen (Holman, 1979). Cope (1873) described a second species, C. talpivorus from the same locality as the type of C. murivorus, Cedar Creek, Logan County, Colorado. Calamagras talpivorus is considered to be the same species as C. murivorus. A third species of the genus from the same locality, also described by Cope (1873) and still considered valid, is C. angulatus.

Stratigraphic and Geographic Distribution Fossilized remains from Calamagras can be found in the late Bridgerian (Hecht, 1959) through the Arikareean. Fossils are most abundant in the Brule Formation of the White River Badlands of South Dakota (Maddox and Wall, 1998). Calamagras is found in the Chadronian in Saskatchewan. They are also found in Nebraska and Colorado. The genus is also known from the early Miocene (early Hemingfordian) of California and Delaware (Holman, 2000).

Natural History and Paleoecology Holman (1979) believed this poorly defined small boalike snake might have vestiges of hind limbs. Calamagras is a member of the Infraorder Henophidia, and general characteristics for this group include vaulted neural arches, round condyles and cotyles on the vertebrae, and a poorly developed hemal keel (Maddox and Wall, 1998).

Systematics and Evolution The type species of Geringophis is G. depressus Holman, 1976. It is from the late Oligocene (early Arikareean) Gering Formation, Crawford locality, Dawes County, Nebraska. Geringophis vetus Holman, 1982, is believed to be found in the Brule Formation in the White River Badlands (Maddox and Wall, 1998). Geringophis vetus is the earliest occurrence of Geringophis in the fossil record (Sullivan and Holman, 1996). It is unknown whether the genus arose from Cadurcoboa from the Eocene of France and immigrated to North America from the Old World or whether it originated from an erycine boid with a flattened vertebral form such as Calamagras angulatus (Sullivan and Holman, 1996).

Distinctive Characters This erycine boid is distinct from other small boid genera found in the White River Group in that the vertebrae have a flattened shape and a long, high neural spine (Holman, 1982). Holman (1979) describes Geringophis as having the following unique characters; the vertebrae contained a reduced neural arch, a long, well-developed, dorsally expanded neural spine, and a well-developed hemal keel and subcentral ridges.

Stratigraphic and Geographic Distribution Fossilized remains from Geringophis occur from the Orellan through the late Barstovian. Fossils are found in South Dakota (Maddox and Wall, 1998), Colorado; the early and late Arikareean; medial and late Barstovian of Nebraska; and early Arikareean of Wyoming (Holman, 2000). Geringophis vetus was described from the early Oligocene (late Orellan) Toadstool Geologic Park in Sioux County, Nebraska.

Systematics and Evolution The type species for Coprophis is C. dakotaensis Parris and Holman, 1978. The type specimen for C. dakotaensis was found in the Big Badlands of South Dakota (Pennington and Shannon Counties). Sullivan and Holman (1996) believe the genus should be assigned to the superfamily Booidea because of they have a wider, more indistinct hemal keel.

Distinctive Characters Coprophis is characterized by vertebra with a narrow, well-developed hemal keel (see Parris and Holman, 1978).

Stratigraphic and Geographic Distribution The type and only known record of Coprophis is from the early Oligocene (Orellan) Scenic Member of the Brule Formation. Fossils of this animal are only known from South Dakota.

Natural History and Paleoecology The vertebrae of Coprophis were discovered during a comprehensive study of the mammalian coprolites from the Brule Formation by D. C. Parris. The type specimen, which consists of vertebrae, are somewhat eroded because of their partially digested state. The coprolite is thought to be produced by a mammal because large nonmammalian carnivores are unknown in the Brule Formation. They were assigned to the new genus Coprophis on the basis of a combination of characters outlined in Parris and Holman (1978).

The suborder Eusuchia includes the modern crocodiles, which have been known since the late Cretaceous. There are three living families of crocodiles: the Alligatoridae, the Crocodylidae, and the Gavialidae. Only members of the Alligatoridae are found in the White River Badlands. The basic crocodilian features such as the massive skull and long snout have not changed since the late Triassic. Other features that characterize the order include a skull that is strongly buttressed and has a fenestrate appearance. Crocodilians also have a secondary palate that separates the nasal passages from the mouth (Carroll, 1988). The suborder Eusuchia is defined by procoelous vertebral centra, and the internal nares within the skull are completely surrounded by the pterygoid. The Eusuchians were much more diverse, numerous, and widespread in the early Tertiary than they are today. Their decline was due to the climatic cooling and drying that has occurred since the early Cenozoic.

5.7. Complete skeleton of Alligator cf. prenasalis. Courtesy of the Division of Vertebrate Paleontology; YPM VPPU 013799, Peabody Museum of Natural History, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut, U.S.A.

The family Alligatoridae is characterized by a short and broad snout. The nasal bones usually reach the external narial aperture. The supratemporal fenestrae are usually smaller than the orbits and sometimes closed over secondarily. The mandibular symphysis is short. The first mandibular teeth and usually the fourth bite into pits in the palate. There are two or more rows of dorsal scutes (Mook, 1934).

Systematics and Evolution The type species of Alligator is the living Crocodilus mississippiensis Daudin, 1801 [1802]. Alligator prenasalis (Loomis, 1904) is the only fossil alligator found in the White River Badlands. Originally described as Crocodilus prenasalis by Loomis (1904), Matthew (1918) reassigned it to Alligator on the basis of more complete material. Alligator prenasalis is well described and has been extensively collected in the White River Badlands. It is includes the oldest specimens assignable to Alligator (Brochu, 1999).

Distinctive Characters Alligator prenasalis has a broad and flat snout, which is considered primitive when compared to other species within the group (Fig. 5.7) (Brochu, 2004). The undivided nasal opening is located quite far forward on the rostrum and does not have a distinctive anterior border. The nostril opening would be directed to the front rather than upward on top of the snout (Loomis, 1904). There is a constriction on the maxilla to receive a tooth from the lower jaw. This occurs just behind the ninth superior tooth. The upper surface of the frontals is covered with large pits (Loomis, 1904). The animal was about 1.5 m long when alive (Fig. 5.7) (O’Harra, 1920).

Stratigraphic and Geographic Distribution Fossilized remains from Alligator can be found in the Chadronian to the Recent in North America (Brochu, 1999). In the White River Badlands, they are found in the Chadron Formation. Fossils of similar age are also found in Nebraska, Colorado, and Florida.

Natural History and Paleoecology Because alligators do not tolerate saltwater, it is thought that they only traveled to other continents via land bridges and were not as widely dispersed as crocodylids. Alligatorids occur exclusively in the Western Hemisphere and Asia during the Tertiary. Within the White River Badlands, alligator remains are found within the channel deposits in the Chadron Formation (Clark, Beerbower, and Kietzke, 1967).

Alligators today are restricted to the southeastern United States along the Gulf Coast through Florida and as far north along the Atlantic Coast to North Carolina. Alligators live in wetland habitat. They are apex predators. The living American alligators are less prone to cold than other crocodilians and can survive colder temperatures. This may explain their presence farther north in the fossil record: the living American alligators can spread farther north than the American crocodile. It is found farther from the equator and is more equipped to deal with cooler conditions than any other crocodilian. As apex predators, they help control the population of rodents and other animals that might overtax the marshland vegetation.

Cenozoic herpetofaunas serve as good indicators for climatic change. A decrease in the diversity of reptiles and amphibians, primarily aquatic forms, begins to occur as early as the Uintan in North America (Hutchison, 1992). There is a significant decline in the diversity of aquatic amphibians and reptiles in faunas within the interval between the Chadronian and Orellan but only a modest decrease in diversity within the terrestrial herpetofauna (Hutchison, 1992). Hutchison (1992) also notes a change in maximum carapace length in tortoises from 80 cm in the Bridgerian to 50 cm between the Chadronian and Orellan. A significant modernization of amphibians and reptiles can be seen after the Eocene–Oligocene transition and through much of the Oligocene. The smaller, lower vertebrates from this time period are not well preserved and so are not well documented. In contrast, a much better record of the larger forms such as the turtles and crocodiles exists. Hay (1908) correlated the reduction in diversity of aquatic turtle faunas to a significant drying on the western plains. Tihen (1964) noted an abrupt transition between the archaic to more modern faunas during this time period. Hutchison (1982) attributed the significant decline in diversity to the reduction in the availability of permanent surface water. The large-scale changes involved the infilling of early Tertiary lacustrine basins, a general increase in aridity, and the decrease or even absence of permanent rivers and streams (Hutchison, 1992).

In addition to being strong climatic indicators, the herpetofauna of the Tertiary Great Plains sediments have provided important information on the transition between archaic and modern faunas from both a biostratigraphic and evolutionary perspective (Sullivan and Holman, 1996).

Compared to other vertebrates, the fossil record for birds is limited in the White River Badlands. Most avian fossils are from the limbs of birds. Complete skeletons or even skull fragments are rare (Adolphson, 1973). The skeletons of birds are lightweight and fragile and are easily destroyed. Fossilization of avian skulls is a rare occurrence because of the delicate nature of this part of the skeleton. Braincases are often not found attached to the beak, as they can be easily separated at the hinge between these two parts of the skull. When a bird dies and floats on a body of water, it is subject to destruction by aquatic predators and scavengers. Its buoyancy usually prevents it from settling on the bottom where it can be buried by sediments. Most bird fossils are restricted to fine-grained, relatively undisturbed geologic sediments (Welty and Baptista, 1988).

The avian skeleton achieves strength with lightness and is constructed with the greatest possible economy of materials. Some bones common to other vertebrates are completely eliminated, and others are fused together. Many of the bones are pneumatized, or filled with airspaces instead of bone marrow (Welty and Baptista, 1988).

There is also a limited record of fossil bird eggs within the White River Badlands. The eggs can be identified on the basis of their general shape and shell texture.

The family Accipitridae includes the red-shouldered and red-tailed hawks. This family and the genus Buteo are widely spread over the world today (Adolphson, 1973).

Systematics and Evolution The type species of Buteo is Falco buteo Linnaeus. The fossil species, B. grangeri Wetmore and Case, 1934, extends the age of the genus Buteo back to the Orellan (Wetmore and Case, 1934). Hawks of a similar type are well represented in the Miocene and Pliocene sediments in Sioux County, Nebraska. The type specimen of B. grangeri (UMMP 14405) was found in the Brule Formation, Jackson County, South Dakota.

Distinctive Characters Buteo grangeri is similar to Buteo melanoleucus, the living black buzzard-eagle, but is slightly smaller, with the frontal relatively narrower between the orbits. The maxilla is stronger, heavier, and deeper. The palatine bones are somewhat more slender. The species is similar to the living red-tailed hawk, Buteo borealis, except that it is larger.

Stratigraphic and Geographic Distribution The range for the genus Buteo is from the Orellan to the Recent. Buteo grangeri fossils were found in South Dakota. The genus Buteo is found worldwide today.

Natural History and Paleoecology Because of their trophic level as predators, hawks and other birds of prey are even less common then other types of birds in the fossil record, and it is difficult to determine specifics about their paleoecology.

5.8. Procrax brevipes, holotype, SDSM 511. Skeleton is almost complete except for skull and vertebral column on limestone slab. Scale in centimeters. Photo by the authors of specimen from the Museum of Geology, South Dakota School of Mines and Technology, Rapid City, South Dakota, U.S.A.

The family Cracidae includes the curassows, guans, and chachalacas; members of the family are found today from the lower Rio Grande Valley in Texas to south to Argentina. In North America, fossils from this family are known from the Cenozoic of Florida, Nebraska, and South Dakota. Features that define the family include the absence of the strongly developed intermetacarpal tuberosity on the metacarpal II, the absence of the prominent notch on the posterior palmer surface of the carpal trochlea, and a small pollical facet on the metacarpal I. There is a flaring of the internal condyle into the shaft of the tibiotarsus, a less prominent internal condyle of the humerus, and a less ruggedly built coracoid (Tordoff and Macdonald, 1957).

The family now has a Neotropical distribution, but it originated in North America. It underwent a substantial adaptive radiation before it retreated southward. Living cracids are most abundant in the tropical zone, but they range also into the subtropical and even the temperate zones in the mountains. They are arboreal and live and nest in trees (Wetmore, 1956).

Systematics and Evolution The type species for Procrax is P. brevipes. The type specimen (SDSM 511) was collected from the Chadron Formation in Pennington County, South Dakota, and consists of an almost complete skeleton except for the skull and cervical vertebrae (Fig. 5.8). Five other fossil members of the family are known in North America. Procrax brevipes is the oldest known cracid.

Distinctive Characters Procrax brevipes has shorter legs and smaller feet and claws than its living relatives Mitu, Crax, Penelope, Ortalis, and Penelopina. Procrax most resembles Pipile but is smaller and has proportionally shorter and thicker claws. It is larger than the Oligocene Palaeonossax (Tordoff and Macdonald, 1957).

Stratigraphic and Geographic Distribution Procrax brevipes fossils were found only in South Dakota. The specimen is preserved in a fine-grained freshwater limestone (Fig. 5.8). These types of deposits are rare in the White River Badlands.

Natural History and Paleoecology Procrax is the largest of the fossil cracids and was believed to have a superior flying ability in comparison to modern forms. Because of its shorter legs and shorter and thicker claws, it was capable of rapid locomotion on the ground and through trees (Tordoff and Macdonald, 1957).

Systematics and Evolution The type species of Palaeonossax is P. senectus Wetmore, 1956. The type specimen (SDSM 457) was collected from the Poleslide Member of the Brule Formation in Pennington County, South Dakota. The genus and species definitions are based on one fragmentary specimen, a distal end of a right humerus. However, Wetmore (1956) thought the features that were preserved were diagnostic enough to name a new genus and species.

Distinctive Characters The distal end of the humerus is similar to Ortalis but with the entepicondyle reduced in size and with a more definite separation from the internal condyle. The internal condyle is relatively smaller and more rounded. The external condyle is relatively shorter and slightly broader. The distal end is more delicate and less swollen (Wetmore, 1956).

Stratigraphic and Geographic Distribution Fossilized remains from Palaeonossax senectus can be found in the Poleslide Member of the Brule Formation. The distal end of the humerus of Palaeonossax senectus was found in Pennington County, South Dakota.

The order Gruiformes includes cranes, rails, limpkins, and their relatives. This group arose late in the Mesozoic from the base of land bird radiation. Most of the order is specialized for life in or over the surface of the water. The order Gruiformes is the most primitive modern order within the assemblage. Most members of the order inhabit aquatic or swampy environments; however, there are few that live on dry land, and some even live in deserts (Carroll, 1988).

The Cariamae include one or more groups of giant, early Tertiary predators.

This is an extinct Gruiform family that was most abundant in the Oligocene. The center of its distribution was in the Northern Great Plains, especially in Colorado, Nebraska, South Dakota, and Wyoming. All of members of this family were flightless and were adapted to a cursorial way of life, similar to the cariamas in South America. Cracraft (1973) proposes that these morphological changes were an adaption to the overall cooling and drying trend in the Oligocene. There is a great diversity in size, ranging from birds 1 m to over 2 m tall (Cracraft, 1968). The fossil history of the family is one of the best-documented records for an avian family over such a short period of time.

Systematics and Evolution The type species of Bathornis is B. veredus Wetmore, 1927. The type specimen (CMNH 805) is a lower portion of a right tarsometatarsus from the Chadron Formation in Weld County, Colorado. Three other species of Bathornis have been described, B. celeripes, B. cursor, and B. geographicus. The type specimen (SDSM 4030) of B. geographicus Wetmore, 1942, is an almost complete left tarsometatarsus from Shannon County, South Dakota. It was collected from the Poleslide Member of the Brule Formation.

Distinctive Characters The genus Bathornis is characterized by a tibiotarsus with condyles not as compressed lateromedially compared to Eutreptornis. The internal condyle with notch in distal border is slight or absent. Internal ligamental prominence is poorly developed. The supratendinal bridge narrows proximodistally. The anterior intercondylar fossa is deep. Condyles spread anteriorly. The tarsometatarsus has a short proximal hypotarsus. The intercotylar prominence is smaller than in Eutreptornis. The humerus has an internal condyle that is raised somewhat distally relative to the external condyle in comparison to Paracrax (Cracraft, 1973). It is believed that many species of Bathornis coexisted at the same time. The tarsometatarsus of B. veredus is much larger than any known species within the genus.

5.9. Fossil bird and bird egg from the White River Badlands. (A) Badistornis aramus, SDSM 3631, holotype, almost complete left tarsometatarsus. (B) Fossil bird egg, crushed side, DMNS 59335. (C) Bird egg, uncrushed side, DMNS 59335. Scales in centimeters. Photos by the authors of specimens SDSM 3631, Museum of Geology, South Dakota School of Mines and Technology, Rapid City, South Dakota, U.S.A., and DMNS 59335, Denver Museum of Nature and Science, Denver, Colorado, U.S.A. All rights reserved.

Stratigraphic and Geographic Distribution Bathornis is found in Colorado, South Dakota, Nebraska, and Wyoming. Fossils are found from the late Eocene through the early Miocene.

Natural History and Paleoecology Species from the genus Bathornis range in a broad variety of sizes and are adapted to wetland or swampy types of environments.

Systematics and Evolution The type species of Paracrax is Paracrax antiqua. The type specimen (YPM 537) is the distal end of a right humerus and was collected from Weld County, Colorado. Three species are described: P. wetmorei Cracraft, 1968; P. gigantea Cracraft, 1968; and P. antiqua Cracraft, 1968. The type specimen (FAM 42998) for P. wetmorei Cracraft, 1968, is a complete right humerus from the Poleslide Member of the Brule Formation, Shannon County, South Dakota. The type specimen (FAM 42999) for P. gigantea is the distal end of a right humerus from the Poleslide Member of the Brule Formation, Jackson County, South Dakota.

Distinctive Characters The humerus resembles that of Bathornis veredus but with an internal condyle that is less distinctly raised relative to the external condyle. The intercondylar furrow is less well marked; the entepicondyle is slightly less raised distally relative to the internal condyle; the brachial depression is slightly less deep; the distal end of the shaft is straighter, not curved when viewed from the side; the area of attachment of the anterior articular ligament is slightly less pronounced; and the external condyle is turned more internally as seen from palmar side. Paracrax gigantea is much larger than P. wetmorei, with all of the features proportionately more massive. Paracrax gigantea was truly a huge bird, standing at about 2 m (Cracraft, 1968).

Stratigraphic and Geographic Distribution Paracrax was found in South Dakota and Colorado in the Oligocene Brule Formation.

Natural History and Paleoecology Paracrax was considered to be a ground-dwelling predator.

Systematics and Evolution The type species of Badistornis is Badistornis aramus Wetmore, 1940. The type specimen (SDSM 3631) is a complete left tarsometatarsus (Fig. 5.9A) collected in Pennington County, South Dakota.

Distinctive Characters Badistornis is characterized by a tarsometatarsus with the inner trochlea projecting distally only to the base of the middle trochlea and turned far posteriorly. In anterior view, the anteroposterior plane of the middle trochlea is inclined internally away from the longitudinal axis of the shaft (Cracraft, 1973:92). Badistornis aramus is the earliest record of a limpkin in North America (Brodkorb, 1967). The tarsometatarsus of B. aramus closely resembles that of the living Aramus scolopaceus (Wetmore, 1940). The tarsometatarsus of B. aramus is slightly longer than that of the limpkin A. guarauna (Wetmore, 1940). Badistornis is a distinctive genus within the suborder Grui and appears to be an aramid that became cranelike during the Orellan, and probably had similar locomotor habits. It shares intermediate features between cranes and limpkins even though these taxa do not have a common ancestor (Cracraft, 1973).

Chandler and Wall (2001) describe three fossilized bird eggs from Badlands National Park, which they believe to be from B. aramus. The eggs compare closest to the eggs from the living limpkin, Aramus guarauna. The overall egg geometry consists of average elongation, average bicone, and asymmetry. The eggs are elliptical in profile and similar to those of other members of the family Aramidae (Preston, 1968, 1969). They also describe the eggshell as porous. Figure 5.9B, C shows DMNS 59335, a partially crushed fossil bird egg from Converse County, Wyoming.

Stratigraphic and Geographic Distribution Fossilized remains from Badistornis aramus can be found in the Scenic Member of the Brule Formation, in South Dakota.

Natural History and Paleoecology Another published record of a fossilized bird egg, possibly from a duck, is from the White River Badlands; however, the collecting data are not precise (Farrington, 1899). It should be noted that no bones of any member of the Anseriformes (ducks, geese, swans) have been found in the Big Badlands, which makes the identification of this egg as a member of this order suspect.

Systematics and Evolution The type species for Gnotornis is Gnotornis aramielus Wetmore, 1942. The type specimen for Gnotornis aramielus is SDSM 40158, distal left humerus from the Poleslide Member of the Brule Formation, Shannon County, South Dakota. This is the only species.

Distinctive Characters The humerus is similar to Aramus but differs in that the entepicondylar area projects only slightly laterally. The ectepicondylar area is relatively larger (Wetmore, 1942). The entepicondyle of Gnotornis projects more distally and that internal contour of the distal end of the shaft is straighter (Cracraft, 1973).

Stratigraphic and Geographic Distribution The type specimen was collected in the Poleslide Member of the Brule Formation in Shannon County, South Dakota.

Natural History and Paleoecology Gnotornis aramielus is described as a volant piscivore, meaning it was able to fly and it fed on fish. These fossils were collected from the Protoceras channel sandstones from the Poleslide Member of the Brule Formation, thus associating them with a riparian environment.

Mammals have been the dominant terrestrial vertebrates for the last 65 million years. The majority of mammalian groups are either marsupials or placentals. The late Eocene and Oligocene have often been referred to a period in Earth’s history when mammals became quite abundant and diverse. Mammal skeletons from the White River Badlands are well preserved in the rock record, with the majority of remains consisting of skulls and teeth.

Marsupials originated in North America during the Cretaceous (Clemens, 1979; Johanson, 1996; Cifelli and Muizon, 1997; Cifelli, 1999). They dispersed from North America and developed two major living assemblages, one in South America and one in Australia (Benton, 2000). The North American Tertiary marsupial record extends from the Paleocene into the early middle Miocene (Barstovian), when they became extinct (Slaughter, 1978). They reappear in North America in the middle Pleistocene (Irvingtonian) (Kurtén and Anderson, 1980) when the modern opossum, Didelphis, entered from South America after the formation of the Panamanian land bridge between the two continents.

North American marsupials were not very diverse, either morphologically or taxonomically. Even though they are represented in nearly all major faunas from the Paleocene through the Oligocene, they make up a small percentage of the sample (Korth, 2008). The marsupial fossil record consists mostly of dental elements, and the group becomes rare by the Miocene.