There was a time, back in the late 1950s and early 1960s, when flash photography was a completely manual operation. A correct flash exposure was 100 percent dependent on the use of the right aperture for the corresponding flash-to-subject distance. Flashes came with handy charts listing the best aperture based on the flash-to-subject distance. You simply located your ISO and flash-to-subject distance on the chart, and there was the preferred aperture!

Today, as you’ve just seen in the first chapter, a correct flash exposure is still 100 percent dependent on the use of the right aperture for the corresponding flash-to-subject distance. Now you might think the electronic-flash industry is living in the dark ages, but the fact is that the electronic flash has come a long way, delivering far more sophistication and much more power than were available back in the ’60s. One exciting example of this is that most of today’s flashes have an automated distance scale. You tell the flash what aperture you want to use, and based on your ISO, the automated distance scale tells you the exact distance your flash needs to be from the subject to record a correct exposure. Conversely, you can plug in your ISO, determine your desired distance from flash to subject, and the automated distance scale will tell you the correct aperture. Set that aperture on your lens, and you’re good to shoot! If this isn’t the aperture you wish to use, either increase or decrease your flash-to-subject distance until the scale indicates the aperture you want.

If you know my book Understanding Exposure, then you’re already familiar with my insistence on learning how to shoot a daylight exposure in manual exposure mode. Many of you have reported to me just how liberating that was and how it opened up an entirely new and far more creative world of photography. You also reported—with tremendous enthusiasm—just how darn easy it was. Well, learning to shoot a manual flash exposure is just as easy.

If you’re not sure how to set your flash to manual exposure mode, get out your flash manual, and look it up. (I’ve put together a series of short video clips describing how to set many of the more popular flashes to manual mode. Visit www.ppsop.com/manualflash.aspx to see if your flash is there.) You also want to set your camera to Manual mode. If one of these devices remains on Auto or Program, your camera might default to a much slower shutter speed to account for low light levels in your scene.

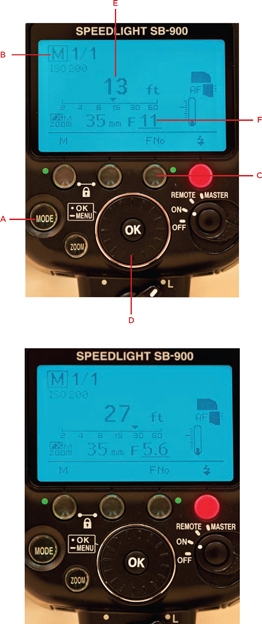

To make this flash exposure of my daughter Sophie at a distance of 13 feet, I used the flash distance scale to determine the correct aperture for my flash-to-subject distance. Pressing the mode button (marked A in the first image, top), I set the flash mode to Manual, indicated by the letter M (B). I’ve now assumed full control of the flash. Since I’ve determined the flash-to-subject distance is 13 feet, I then set the flash distance to 13 feet by pressing the aperture selection button (C) and then turning the wheel (D) until 13 feet shows on the distance scale (E).

(Turning the wheel clockwise causes the distance scale to indicate a shorter flash-to-subject distance and a correspondingly smaller aperture. Turning the wheel counterclockwise causes the distance scale to indicate a greater flash-to-subject distance and a correspondingly larger aperture, as pictured in the bottom image when I turned the dial all the way to 27 feet and the correct aperture became f/5.6.)

Once the distance scale reads 13 feet, the flash’s display indicates a necessary aperture of f/11 (F). So that means the amazing computing power of my flash just told me I need to use an aperture of f/11 to record a perfect flash exposure of a subject that’s 13 feet from the flash. (Note that the flash was mounted on the camera’s hot shoe for this shot.)

Nikon D300S, 24–85mm lens, ISO 200, f/11 for 1/100 sec., Speedlight SB-900

Now it’s time to grab your camera, flash, and a willing subject—maybe a person, animal, or that proverbial vase of flowers on the table. With your camera and flash in Manual mode, set your camera’s shutter speed to 1/100 sec. (Note that it doesn’t matter whether you have a built-in pop-up flash or an external portable electronic flash, as long as you have it set to Manual flash exposure mode.) Then stand at a distance of 13 feet from your subject. Turn the wheel (or it may be buttons, depending on your flash make and model) on the back of your flash until 13 feet shows up on the distance scale (like you see in the display on this page). If your flash doesn’t show exactly 13 feet, no worries; just pick the distance closest to 13 feet (12.3, 12.7, 13.4, or whatever it may be).

Note the corresponding aperture for the distance of 13 feet, and set that same aperture on your lens. Then simply focus and shoot. Voilà! You just shot a perfect flash exposure of your son, daughter, wife, husband, dog, cat, neighbor, cousin, uncle, grandma, or vase of flowers. This was no fluke! Pretty cool and easy to do, eh? I’ll say it again: Perfect flash exposure has always been—and always will be—about choosing the right aperture for the corresponding distance between the flash and the subject.

(Keep in mind that this perfect exposure is of the main subject only. You may not be particularly fond of the contrast between the subject and the background, much like what you see in my shot at right. Don’t worry about that right now; I’ll get into proper exposure of background elements later.)

And this simple process also works the other way, especially when you’re free to move closer or farther away from your subject: If you have a specific aperture you wish to use—because of depth of field concerns, for example—you can set that aperture on your lens, plug the same aperture into your flash’s distance scale, see the suggested flash-to-subject distance necessary for a correct exposure at that aperture, and simply move to that distance from your subject. Consider again the example shown here, where the subject was 13 feet from the flash. My Nikon Speedlight SB-900 suggested an aperture of f/11 for this distance. But let’s assume I want a lot of depth of field in my image and, therefore, set the lens aperture to f/22. Correspondingly, I’d also set the f-stop on the flash distance scale to f/22, and in turn, the distance scale tells me that to achieve a correct exposure of the subject at that aperture I’d need a flash-to-subject distance of 6 feet. So if the flash is mounted on my camera, I move to a spot 6 feet from the subject, or if the flash isn’t on camera, I move the flash to a spot 6 feet from the subject, and then I’m free to use f/22.

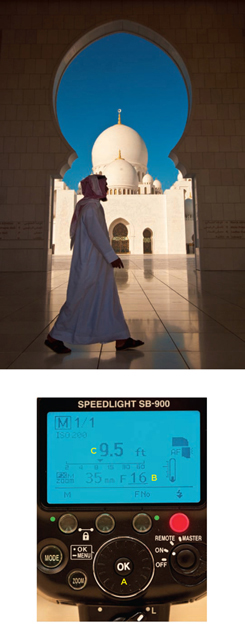

Now that you’ve seen how easy it is to set a manual flash exposure, let’s do it again—but this time in combination with outdoor ambient light. The first step is to determine the correct shutter speed for the ambient light only. In my first image, I metered exclusively for the natural light before me. I knew I wanted somewhat substantial depth of field, so I set the aperture to f/16, and taking a light-meter reading from the blue sky ahead of me, I determined that the correct shutter speed for f/16 would be 1/200 sec. Not surprisingly, Yousif, my subject, recorded slightly silhouetted, since he wasn’t walking in the area lit by the sun; only those areas lit by the sun recorded as a correct exposure.

To bring Yousif “into the light,” I called on my “miniature sun.” Since I wanted to stick with f/16 for depth-of-field reasons, I already knew the correct shutter speed for the ambient light was 1/200 sec. To add flash and correctly expose Yousif, the only thing I needed to determine was the correct flash-to-subject distance. I rotated the dial (A) on the back of my Nikon Speedlight SB-900 and saw that for f/16 (B) the subject should be 9.5 feet (C) from the flash. I estimated that Yousif was around 10 feet from the camera—close enough. I instructed Yousif to walk through the scene once more, and when I exposed the image again at f/16 for 1/200 sec., the flash also fired, illuminating him while still maintaining a correct exposure of the surrounding elements.

So to recap: I determined the correct exposure for the daylight, used that aperture to find the correct flash-to-subject distance, positioned the flash appropriately, and took the shot using the original exposure plus the flash. Are we having fun, or what?

Both photos: Nikon D300, 12–24mm lens at 24mm, ISO 200, f/16 for 1/200 sec. First image: with Speedlight SB-900

As easy as that last example was, let’s look at another in which, once again, I combined the ambient light with the flash’s light for a perfect exposure. For this one, I set up low to the ground on the Alexandria Bridge in Paris, anxious to frame the distant Eiffel Tower through the balustrade lining the bridge. Without the benefit of flash (first image), I was able to record a nice exposure of just the ambient light in the scene. (Since I wanted a large angle of view and great depth of field, I used my 16–35mm lens and f/22, presetting my focus at 1 meter into the scene via the distance scale on the lens, and simply adjusted my shutter speed until 4 seconds indicated a correct exposure.)

For the first image, nothing changed in my exposure settings; I still was at f/22 for 4 seconds. But clearly, something has happened—and that something was the simple addition of flash. Using the flash’s distance scale, I determined that at f/22 the flash set at 1/2 power would need to be about 4 feet from the subject (the balustrade) to record a correct flash exposure. I then simply held the flash in my left hand about 4 feet from the balustrade columns and fired the camera with my right hand. The columns were then illuminated, while at the same time, the ambient exposure of the other areas of the scene was maintained.

Both photos: 16–35mm lens at 16mm, f/22 for 4 seconds. Second image: with Speedlight SB-900

If you’ve never messed with your flash’s power settings, then chances are really good that the unit is at full power, since all flashes are shipped from the manufacturer with the default setting of full power in place. A full-power setting is typically indicated as a fraction of 1/1 on the flash’s display screen. If you play around with the power settings, you’ll quickly see that you can change this fraction and the corresponding flash power output. So 1/2 would indicate you’ve powered down the flash to half its full-power output, for example; 1/4 would indicate one-quarter power output; and so on all the way down to possibly 1/32, 1/64, or even 1/128, depending on your flash. Each of these fractions represents the fraction of the full-power output. Too many photographers think that powering down is something you only do when you don’t want the flash to overpower the subject, as in a simple portrait for which all you need is a bit of fill light to reduce the raccoon eyes, for example. However, powering down can also be much more useful than that—it gives you freedom of movement.

What exactly is going on when you mess with the power settings of your flash? Simple math tells you that you’re cutting down the flash power, and simple math is right. At full power (1/1) and with ISO 200 and a subject at a distance of 16 feet, the flash tells me I’ll need to use f/11 to record a correct flash exposure. If I reduce the power to 1/2 (half-power), what happens? Take a look at the distance-scale readouts on this page. Assuming I keep an aperture of f/11, the flash now indicates a flash-to-subject distance of 11 feet.

It’s pretty simple to see what’s happening: The more you power down your flash, the closer the flash must be to your subject to maintain a correct exposure. Trust me, there are many subjects you’ll want to place the flash closer to. With the flash at full power, many of those subjects would be way overexposed, since the flash is putting out too much light based on its distance to the subject. Fortunately, by powering down the flash, you can still come away with a perfect flash exposure, even when working at seriously close distances.

Think of this analogy if it helps you: Assume for a moment that your flash at full power (1/1) is a 1-gallon bucket of water, and the subject you want to douse with this gallon of water is 15 feet away. Press the shutter on your camera, and whoosh! Your subject is now soaking wet from the gallon of water. If you set the flash to half-power (1/2), it’s like you’re swinging the gallon bucket with only half the strength. The water will still come out, but it’ll only travel half as far. So at half-power you must move in closer if you want your subject to be doused by the full gallon of water. When powering down, as long as you move your flash closer to the subject as indicated by the distance scale, your subject will still get the full flash intensity—that entire 1-gallon dose of water.

On a beautiful, sunny day around 2:00 PM during a workshop in Tampa, I noticed our model, Deana, lying in a hammock during a break. This sparked an idea, and lying underneath the hammock, I prepared to photograph upward as she looked down at me, framed by the many ropes of the hammock (first image). However, the resulting available-light exposure of f/11 for 1/125 sec. was quite flat. The sun was still high in the sky, just to her left from this shooting angle, which explains why there wasn’t any light on her face. I could have used a reflector, placed right on top of me to reflect the sunlight up onto her face, but the intense light would surely have caused her to squint, and this was not the time to shoot a “squinting portrait.”

A more favorable option was to call on portable electronic flash. I wanted to replicate the warmth and color of low-angled light on a late-afternoon summer day, so I also placed an amber gel on the flash. (This affected my flash-power setting in this scenario, but I’ll get into that topic later on this page.) I quickly realized that I’d need to power down my flash, because I was very close to Deana—about 18 inches, in fact. I wanted to use an aperture of f/11, the critical aperture at which both sharpness and contrast reign supreme. So with f/11 set on my lens and flash, I began to dial down the power until I saw that 1/128 power would give a correct flash exposure at my flash-to-subject distance of 18 inches. Since I wanted to replicate a low-angled sun, I also chose to hold the flash about 20 inches to my left, creating low-angled sidelight. As you can see, I achieved my goal.

Both photos: Nikon D300S, 12–24mm lens at 24mm, ISO 200, f/11 for 1/125 sec. Bottom: with Speedlight SB-900

Following a workshop I taught in Tucson, two students, my assistant Wayne, and I ventured out for an unscripted evening of shooting. Searching for the perfect cactus-laden desert landscape, we instead came across a dead-end sign that faced a mountain range as we headed west. The sign spoke to me. All it needed was a bit of light to make its voice heard.

So I grabbed my camera, tripod, and two of my Nikon Speedlight SB-900 flashes. Choosing a low-angled position, and shooting upward and close to the sign, created a point of view that elevated the sign to a stature of supreme importance, especially when combined with both ambient light and the light from a couple of flashes.

I decided I wanted passing red taillights heading into the dead end up ahead, so I asked Wayne to drive our van into the scene during my exposure. Since I wanted taillight streaks, I needed an exposure time of at least 4 seconds. These 4 seconds would allow the taillights to streak across the entire composition as Wayne drove through the scene. So with ISO 200 and the shutter speed set to 4 seconds, I metered off the dusky blue sky and adjusted my aperture until the camera’s light meter indicated f/11 for a correct exposure.

This, of course, was the correct exposure for the ambient light. Since my ambient exposure relied on the aperture of f/11, I was committed to using that same aperture for the flash exposure. With both of my flashes set to Manual, their distance scales indicated a flash-to-subject distance of about 11 feet for a full-power (1/1) exposure at f/11. That just wasn’t going to happen, since I had every intention of staying close to this road sign. As I powered down both flashes, I found that at 1/32 power at f/11, the flash-to-subject distance was now 2 feet. Perfect!

I placed one flash on the ground, pointing it up at a slight angle toward the gray post. I also placed a red gel on this flash to turn the gray post blood red. (Don’t let my use of a red gel here throw you off; even without it, my setup for this shot wouldn’t have been any different, and I’ll talk about the use of gels more on this page.) I held my other flash in my left hand, off to the left of the sign. And since I was introducing motion into this scene, I set the camera to rear-curtain sync. Most flashes fire at the beginning of an exposure, but with rear-curtain sync, the flash doesn’t fire until the end of the exposure, which is what I needed here with the extended shutter speed and going for taillight streaks. (See more on rear-curtain sync.)

At this point I signaled to Wayne, who was waiting on the road about 10 feet behind me. Just before the van entered my composition, I tripped the shutter release, and 4 seconds later, this image was the result.

Nikon D300S, 12–24mm lens at 12mm, ISO 200, f/11 for 4 seconds, Speedlight SB-900

In this image you’re seeing various shots of the display screen on the back of my Nikon Speedlight SB-900. Take a look at how the required flash-to-subject distance displayed by the distance scale gets smaller as I power down the flash output. The mode (M for Manual) and the power-output fraction are in the upper left corner of each screen. In the top readout, that fraction is 1/1, indicating that I’m at full power, and the necessary flash-to-subject distance is 16 feet. Reduced to 1/2, that flash-to-subject distance shrinks to 11 feet. If I reduce power from 1/2 to 1/4, the flash indicates I can achieve a correct exposure only if my subject is 8 feet from the flash. At 1/8 power, it’s 5.6 feet. At 1/16 power, 4 feet. And finally at 1/32 power, a correct exposure requires a flash-to-subject distance of 2.8 feet. It’s a clear illustration of the relationship between power output and flash-to-subject distance.

In the late 1960s, Honeywell came up with automatic flash, thus eliminating, in theory, the need to readjust the aperture every time someone moved from the distance for which the flash was set. Eventually this automatic flash concept was further developed into what is today known as TTL (through-the-lens) flash, initially introduced with great fanfare by Olympus back in the ’70s. Today’s flashes are even more sophisticated, most using E-TTL (evaluative through-the-lens), while Nikon now has i-TTL (intelligent through-the-lens). And to be clear, TTL isn’t limited to portable flash. It’s the “norm” for all of those built-in or pop-up flashes found on digital point-and-shoots and many DSLRs. Just as you can change the setting for TTL on a portable flash to Manual flash exposure mode, you can also change the standard TTL default setting to Manual flash mode on most pop-up and some built-in flashes.

TTL works on a simple premise of first sending out a “pre-flash”—an infrared beam or white light—that strikes your intended subject, travels back to the camera, and tells your flash’s onboard computer how much flash power is needed to create a correct flash exposure based on the amount of light that comes back to the camera’s meter. The pre-flash beam calculates the amount of light needed based on the light actually coming through the lens along with the subject-to-flash distance. The camera’s onboard computer then adjusts the flash power based on the amount of light reflecting back into the camera. This pre-flash journeys out from near the flash head and returns so darn fast that you don’t even know it happened. What pre-flash? Exactly.

Let’s say you want to take a picture of your son, who’s standing 12 feet away, and you’re using an aperture of f/8. As you press the shutter button, the pre-flash zips out of your electronic flash, bounces off your son, and flies back to the flash unit to tell the onboard computer, Okay, Boss, here’s the deal: We need to light a subject 12 feet away, and the photographer is using an aperture of f/8. The onboard computer makes a calculation based on these variables and tells the flash to put out exactly the right amount of power. To ensure even more accuracy, this pre-flash is metered at whatever you focus on.

Technology can be good, and for some, TTL flash technology is the greatest of all. If you’re a professional wedding photographer, event photographer, photojournalist, or member of the paparazzi, operating in TTL mode makes perfect sense. You don’t have to think about anything—just point and shoot. I’m all for TTL in some instances, but even the latest and greatest flash out there will become a useless tool if you don’t know where to aim it and understand where the light is going—even when using TTL.

Why do I dislike TTL? Because it has a heck of time dealing with white or black subjects. Consider this example of my wife, Kate, standing in an alleyway against a black wall while wearing a white blouse. As you can see in the first image, TTL flash mode produces an essentially underexposed result. In TTL mode, the flash powers down a bit automatically, limiting its light output, because it gets fooled by the white blouse. The flash attempts to make the white blouse gray, and it does a fairly good job, but since Kate’s blouse is white, I want it to look white.

When I switch to Manual flash exposure, I know, without question, that I’ll record a perfect flash exposure, simply because the aperture I’m using corresponds to the flash-to-subject distance. Unlike TTL mode, in Manual mode there’s no infrared beam that measures the reflected value and distance to the subject—and thus, no opportunity to record a bad exposure. The full power of the flash is realized, since I set the exposure, and unlike the TTL metering, the flash isn’t being fooled by the white blouse. As the second example clearly shows, the correct flash exposure reveals a much more stunning Kate!

Both photos: Nikon D300S, 24–85mm lens, f/8 for 1/200 sec., Speedlight SB-900. First image: TTL mode. Second image: Manual flash mode

Let’s examine the manual vs. TTL flash question a little deeper. The thought process usually goes something like this: Just use TTL flash, and it will take a perfect flash exposure every time. It does so without asking anything of you. No matter where you take are, no matter what your subject, no matter what time of day, just call on TTL! If you’ve spent any time in photo chat rooms, at camera clubs, or jawin’ with other photographers at your local Starbucks, you are no doubt familiar with this argument. Well, guess what? This assertion just isn’t always true. You can get perfect exposures in TTL, sure, but it requires some degree of input from you. The day of simply aiming, focusing, and shooting has yet to arrive. With TTL, we’re really, really close, but manual flash exposure still provides the most control over your flash exposure in the widest variety of shooting situations.

Outside of the aforementioned wedding photographers, photojournalists, and paparazzi, there are but a handful of photographers who honestly understand flash so well that when they operate in TTL mode they can actually predict the outcome almost all of the time. I want to know what’s going on with the camera and flash before I shoot. I want full control, from start to finish, of both my exposure and composition. My deliberate manual mentality carries over to my use of flash. I have deliberately set my flash to Manual mode, and for the most part, it never leaves this parking spot. I know, just about every time, what the flash is going to do, where it’s going to go, what it’s going to light, and how the light will be shaped before I press the shutter release.

Since I’m a fair guy, I must be fair to TTL and describe where I think it’s most useful. While it does take some time—albeit just seconds—to establish a proper manual flash exposure, it takes even less time to use TTL. If you have a moving subject, for example a speed walker heading straight for you on the sidewalk or the airborne boy opposite, the distance from subject to flash is constantly changing. Unless you can function at warp speed, it will be a challenge, if not impossible, to keep up with evaluating the flash-to-subject distance and then spinning the aperture dial quickly in an attempt to provide an accurate manual flash exposure. By the time you calculate the distances and settings, they will have changed. In this case, TTL allows you to just pay attention to the moving subject and concentrate on framing and composition. You have to make the choice that works best for you, which may be manual flash for some subjects and TTL for others.

The reason I usually choose manual is that, while today’s flash units are highly advanced, the TTL metering can still be fooled. Alternatively, when you work in manual flash and adjust your settings correctly, your exposures are perfect every time. Here’s an example: Let’s say your neighbor’s cousin asks you to photograph his summer wedding. After doing some group portraits, you switch your camera to TTL so that you can circulate through the reception, capturing candid moments of moving subjects. A few moments later, however, the bride returns and grabs you for one more portrait. As she poses in front of the white wall with her flowing white gown and her three nieces, also in white dresses, you click away. But when you check the results, you flinch at what you see. Each of those frames is dark and gray, indicating an “under-flashed” exposure.

What happened? TTL metering was fooled by all the white in the scene (the white wall and white dresses). With TTL, all faith is placed in the flash’s ability to meter the light reflected back off the subject. Because white is highly reflective, when the pre-flash bounced back to the camera, it indicated a higher-than-actual amount of light, causing the flash meter to say “enough flash” and prematurely stop the flash, resulting in an under-flashed picture.

The opposite problem can occur with dark subjects. Take the groom and all the groomsmen and position them in front of some dark burgundy curtains, and the TTL flash metering may very well be fooled again. Those black, light-absorbing tuxedos may not bounce back enough light to the flash metering system, so the flash thinks it needs to send out extra light to brighten up the dark subjects. This results in “over-flashing” the groom and groomsmen, which renders those black tuxedos gray instead of their true shade.

As simple and easy as TTL is to use, you now understand my preference for manual. Manual flash mode takes a little more thinking and some simple math (estimating the distance between the flash and the subject), while TTL is quick and easy but a little less reliable. The choice is now yours!

To assure you that I’m not too set in my ways, I’ll admit that I have used TTL flash both indoors and outdoors. And this shot is one example of the latter. While at a skate park in New Zealand, I found kids everywhere, zooming past me at varying distances and speeds and making repeated jumps with their scooters and skateboards. With my aperture set to f/11, TTL told me, Don’t you worry about a thing, Bryan! We know you’re at f/11, and as you can see on the distance indicator, as long as you shoot subjects that are within 2 and 10 feet, we’ve got you covered!

I took around fifty shots over the course of the next 10 minutes, but none was more satisfying than this.

Nikon D300, 12–24mm lens at 24mm, ISO 200, f/11 for 1/80 sec., TTL mode

I do on occasion shoot in TTL mode. On one crisp fall afternoon in Chicago as my daughter Sophie played outside with her friend Orion, I noticed the strong backlight around Orion’s hair. With my lens at a focal length of 200mm and the flash head set to 200mm (see this page), I fired up the flash and set it for TTL. Since I wanted to render the background trees as out-of-focus tones, I chose an aperture of f/5.6 for shallow depth of field and adjusted my shutter speed until 1/200 sec. indicated about a 2-stop underexposure for the natural light reflecting off Orion’s face. As you can see in the first image, her face was still a bit too dark.

I could have simply changed my shutter speed from 1/200 sec. to 1/50 sec. and rendered her face as a brighter exposure, but in doing so, her naturally backlit hair would have been recorded as another full stop overexposed (it was already about 3 stops overexposed). Also, the bright background of out-of-focus leaves would have been too bright. So what was my option? Flash, of course. With my flash mounted atop my camera and covered with a small diffuser, my flash’s distance scale told me that in TTL mode I could take my picture at f/5.6 as long as I wasn’t closer to the subject than 3 feet or farther away than 45 feet. Since I was about 15 feet away, I was well within the TTL range, and as the second image shows, a perfect flash exposure resulted.

Both photos: 70–300mm lens at 200mm, f/5.6 for 1/200 sec. Second image: with Speedlight SB-900

You may have heard about the low noise and fine grain that you can expect when shooting with the high ISOs found on many cameras today. The argument suggests that you no longer need to use a flash because these high ISOs allow you to handhold your camera even in low light, using shutter speeds fast enough to capture properly exposed images with low noise. So when is it better to use a high ISO with natural light, and when should you use a flash?

Let’s say you’re at your child’s basketball game in a gym illuminated by the typical artificial gym lights. I would never suggest that you try to light up your kid’s basketball game with a flash. Instead, I’d suggest a much more logical solution: available light. If you’re using a modern DSLR with ISO 6400 and your white balance on Automatic, at least initially, you’d find yourself shooting exposures at f/4 for 1/250 sec. At the end of the game, you’d not only have some great shots but shots that were far from being massively grainy, due to the low-noise capabilities of most modern cameras—and all made, of course, without an electronic flash. Taking advantage of these low-noise high ISOs is certainly not limited to the gymnasium. At indoor birthday parties, turn up the lights in your house, set your camera to ISO 6400 and your white balance to Incandescent or Fluorescent, and with your lens aperture set at or near wide open, you’re good to go.

Like many parents today, I, too, am faced with photographic challenges that revolve around school activities, indoors or out, and many of those challenges and subsequent decisions involve the use or “non-use” of flash. However, when it comes to indoor volleyball and basketball—and, in some cases, even school plays—I am of the mind-set that one use the highest-quality ISO in lieu of flash.

Most gyms, and even stages, are lit well enough that recording acceptable handheld exposures is the norm with today’s DSLRs. It’s as if the camera manufacturers are in a constant race to see who can deliver the highest ISO without a truly noticeable drop-off in overall color, contrast, and distracting noise. In the photograph here, I found myself on the sidelines at one of my daughter Sophie’s volleyball games. Handholding my Nikon D300S with my ISO set to 6400, I was easily shooting correct exposures at f/4 for 1/320 sec. with my 16-35mm Nikkor zoom. A no-brainer for me! If I had tried to light up this entire gym with my single Nikon Speedlight SB-900 flash, I would have been ensured of recording very cavelike exposures thanks to the Inverse Square Law.

Nikon D300S, 16–35mm zoom lens, ISO 6400, f/4 for 1/320 sec.

One important thing to note: The low-noise, high ISO approach deals only with brightness levels. It provides little help for poor-quality lighting. Just because you can use high ISOs with shutter speeds fast enough to handhold doesn’t mean you should always choose that option over flash. Here’s why: The ambient light isn’t always complementary to your subjects. High ISOs will not improve poor lighting conditions. If you’re outside preparing to take a picture of your family at high noon, the sunlight will be directly overhead and create “raccoon eyes” on everyone. This effect can also occur indoors where the light source is straight above the subject. In this circumstance, you want to use flash in a fill-flash capacity to correct the poor light conditions by providing supplemental light on the faces that eliminates the raccoon eyes. (See more on fill flash.) The low noise now seen with high ISOs is very useful, but it will never be a replacement for using flash to achieve better-quality lighting.

While exploring the many small villages that surround the area around Angkor Wat in Cambodia, I came upon this mother and child. It was near dusk, the sun had been hiding behind some cloud cover for the past thirty minutes, and by the looks of the western sky, the clouds weren’t in any mood to give the sun a final chance to cast its golden glow on the people and landscape before setting below the horizon. As a result, we found ourselves clearly in a very low-light situation.

I could have just cranked up the ISO, but I thought I’d also try re-creating the look of low-angled sunlight with flash. If you compare the two options here, I bet you’ll agree that flash is the winner. For the natural-light exposure (top), I handheld my camera and, with my ISO set to 1600, chose an aperture of f/8 and adjusted my shutter speed to 1/100 sec. With only ambient light (i.e., without flash), the light is flat, since the sun is well obscured by cloud cover. For the flash exposure (bottom), I again handheld my camera but set my ISO to 200. I was still using f/8, and since I wanted to kill what little ambient light was left, I also kept the shutter speed at 1/100 sec. (Note: f/8 for 1/100 sec. was the correct exposure for ISO 1600, but since I reduced the ISO down to 200, I was in effect recording a 3-stop underexposure of the ambient light.)

When I covered my flash with a light-amber gel, I found that at f/8 I needed a flash-to-subject distance of 3 feet with the flash set to 1/16 power. So I tethered the flash to the camera via a remote hot-shoe cord and held the flash in my extended left arm. I then fired away, and a much warmer, sharper, and colorful image resulted.

High ISOs are a great addition to your arsenal of photographic choices and should be called upon whenever flash cannot light up the entire necessary area or when the use of flash is either strictly forbidden or would get you “discovered” or would scare your subject. If none of these criteria apply in your shooting situation, however, don’t let yourself get complacent; take the extra minute to set up your flash and flatter your subject while letting your peers also know that you are indeed serious about photography!

Both photos: 105mm lens, f/8 for 1/100 sec. Top: ISO 1600. Bottom: ISO 200, Speedlight SB-900

If you’re serious about flash photography, you’ll have far better results if you invest in a portable external flash, which is what I used for most of the images in this book. However, that doesn’t mean pop-up flashes are totally useless; rather, you have to work within their limitations. One of those limitations is that pop-up flash isn’t very powerful and is best suited for subjects that are 10 to 12 feet from the camera. In addition, if you’re using a wide-angle lens zoomed out to its widest focal length, the top of the lens will partially obstruct the pop-up flash light, casting a shadow on the bottom of your picture.

The position of the pop-up flash is also limiting, because it sits right there on top of your camera, pointing straight out at the same subject you see through your lens. There’s no ability to rotate or change angles to “bounce” the flash off a reflective surface. (See this page for more on this technique.) And this limited positioning and lack of mobility also contributes to the pop-up flash’s frequent deer-in-headlights results. One way to dim your flash is to hold or wrap a small white tissue over it. You’ll still see the deer-in-headlights effect but without the harsh, glaring results of raw, on-camera flash.

And I have to admit that when, on occasion, I forget my portable flash, the pop-up saves me from completely missing out on any photographic opportunities, as the images on this page and this page prove.

That deer-in-headlights look seen in the first image is one of the most common outcomes when using pop-up (or even portable) flash indoors, and it’s one of the reasons why most of us don’t look forward to taking pictures indoors. But you can lessen this effect, whether indoors or out, with a simple fix: white tissues.

That’s just what I did as my family headed out to dinner on a recent vacation. The strong backlight of a setting sun will almost always require the use of the flash if you have a subject in front of that backlight that you want to illuminate. Remember, your camera’s “vision” is more limited than yours (see this page). Even though you can see both the setting sun and your subject, the camera’s image sensor cannot. If you simply aim and shoot without benefit of flash, you’ll get a silhouetted subject (top).

While pop-up camera flashes aren’t ideal, if that’s all you have available, you can still illuminate the scene. You just need to take one step to avoid or soften the deer-in-headlights, blown-out flash look: Cover the flash with a small piece of white tissue—a single layer will do—then trip the shutter release, and voilà! When I did this image (bottom), the pop-up flash light was diffused as it passed through the tissue, creating softer foreground illumination of my daughter Chloë while still properly exposing her against the strong backlight of the setting sun.

Bottom: Nikon D300, 35–70mm lens, ISO 200, f/5.6 for 1/250 sec., TTL flash

I made these shots one summer when my nephew Tyler joined me for a day in Seattle’s Alki Point neighborhood. As the afternoon progressed to dusk, I noticed the potential for one of those magical shots of a west-facing city skyline, realizing from experience that all that glass in the buildings would soon reflect the sunset colors in the western sky behind me. I knew I’d have no depth-of-field concerns, since everything was at the same focal distance, and metering off the dusky blue sky, I got a correct exposure at f/11 for 1/8 sec. Then I recomposed with the skyline as the main subject (top).

About this time, Tyler was standing atop a nearby picnic table pretending to be a rock star onstage. How cool would it be, I thought, if I were to light him up with the Seattle skyline in the background? But when I reached for my Nikon Speedlight SB-900 flash, my heart sank. I had left it behind. Fortunately, the Nikon D300 camera has a built-in pop-up flash. Its power is certainly not that of the SB-900, but it can still play with the big boys as long as I help it along by moving closer to my subjects.

So with the flash popped up and set to TTL mode, I changed my aperture to f/4, because I wanted to set an exposure for the ambient light of the city and be able to handhold the camera. I found that f/4 let me use a shutter speed of 1/60 sec.—fast enough to handhold without risk of camera shake blurring the image. My flash distance scale indicated that f/4 would work for any subject within 4 and 10 feet. Since I’d already established that f/4 for 1/60 sec. was also the exposure needed for the distant dusky skyline, I knew I could safely record a flash exposure of Tyler while also recording a correct ambient-light exposure of the city behind him.

Top: Nikon D300, 28–70mm lens, f/11 for 1/8 sec. Bottom: Nikon D300, 28–70mm lens at 50mm, f/4 for 1/60 sec., TTL flash

If you went out and bought a new flash—something above and beyond the pop-up that comes with your camera—you may have set about trying to fill an entire room up with light only to find it didn’t work. How come? There are three reasons why your flash doesn’t fill up an entire room: (1) Though often shocking to many shooters, flash is constantly at the mercy of the Inverse Square Law, which, as discussed, dictates that light falls off from its source, often before it reaches the subject. (2) The flash may not have the necessary power to light up most rooms in their entirety. And (3), when you shoot indoors, you’re probably mounting the flash on camera and pointing it in the wrong direction.

This last one’s important, so let’s consider it in more detail: Firing your flash while pointing it directly at the subject will often result in something resembling a mug shot. If the person in your photograph were holding a sign with a booking number, the image could pass for a mug shot taken by your local police department. The cops are using a camera with—you guessed it—a pop-up flash or a portable flash mounted on the camera’s hot shoe and pointed directly at the suspected criminal. I seriously doubt that you’re striving to make everyone you shoot look like a hardened criminal, and therein lies the problem with on-camera flash (whether pop-up or portable). It is one-dimensional, creates flat light that’s harsh and filled with contrast, and rarely flatters the subject.

Learning how to power up or down your pop-up flash, or using the exposure compensation settings when in TTL mode, can help somewhat, but let’s not forget that pop-up flashes are always pointed in the wrong direction and are therefore darn near useless for indoor photography. There, I said it. There’s no reason to sugarcoat it. Facts are facts, and the fact is that, unlike a portable electronic flash that you can position and place just about anywhere, your built-in pop-up flash can never move from its perch atop your camera. This flash position, especially indoors, often leads to the deer-in-headlights type of flash picture—one in which the subject is overly illuminated, with dark shadows behind. That look is a direct result of combining the bright output of your flash with the darker ambient light in a room. The room may seem well lit to your eyes, but your flash doesn’t “see” what you see. Your flash only knows how to do one thing: light up a subject in front of it with “daylight.” Its primary goal is to make everything look lit by the sun. Your flash produces imitation daylight, and the lights inside of your house do their best but can’t reach the same intensity, especially once the sun has gone down.