3

Uses of this Ethical Model

3.1. Implementing the ethical model

In the context of our study, we took inspiration from models proposed by Beauchamp and Childress [BEA 01], Massé [MAS 03], Vézina [VÉZ 06] as well as the ethical analysis space that we created so as to build our own model and theoretical framework based on the four universal ethical principles.

For this reason, an analysis of the production and use of a healthcare IS by investigating specific and concrete areas is necessary. They represent “real justifications,” veritable keys to interpret reality, characterized by various sectors such as technology, organization, politics, behavior and ethics. Note that these justifications were built from a literature review on the subject as well as from semi-structured interviews with managers, designers and users of IS, as well as with individuals known to be “experts” on the topic.

To all these ethical principles were associated values that these justifications reference. The values implicate all that is subjected to either a supportive or a rejecting attitude, or a critical judgment, by an individual or a group of individuals and that results in conscious or subconscious attitudes, behaviors or stances. For this reason, all contemporary writers of medical ethics insist on the personal values of actors as standards used to approach and understand individual behaviors.

Nonetheless, we can see that healthcare professionals also refer to other systems of values than their own, notably within:

- – objectives (therapeutic, preventative, promotional or relational) undertaken;

- – intervention methods and used techniques due to the advances of disciplinary knowledge;

- – the art of intervention drawn from acquired experience.

This process allows for each doctor involved not only to have an awareness of their personal scale of personal and professional values, but also to distinguish and evaluate the differences between these values and those of their patient, which could become reasons for conflict. According to Reigle and Boyle [REI 00], “the clarification of values does not indicate which decision must be taken or which action should be undertaken, but examines the coherence and compatibility between the different value systems involved. It can notably result in more coherent decision-making and behavior”.

Thus, the clarification of personal, professional and institutional values constitutes a prerequisite for all reflective approaches to medical ethics.

Moreover, for clarity and understanding, the creation of this technical and ethical model is based on only four fundamental ethical principles. The ethical rules described in the first paragraphs are not present, even if they are indirectly included in the model through the major ethical principles.

Ultimately, the combination of these different criteria should allow us to highlight locations where ethical issues might lie. The consideration of several justifications on a single parameter of the IS, or the contrast between different principles and resulting moral values, will bring ethical clarity to solutions to the problems and challenges faced by our research (see Tables 3.1 and 3.2).

This model therefore shows ethical principles down the columns and the keys to interpreting reality across the rows. The aim is to identify when one of these justifications can be applied to an ethical principle. Or inversely, to show when one of the ethical principles or social values will be upheld by one of these keys to understanding reality. Supported by this questioning and continuous research of a “human” IS, healthcare establishments will be able to incorporate an ethical methodology and reasoning that will be suggested to managers and users of the IS.

This ethical model is therefore the foundation on which our analytical questionnaire, critical to undertaking our field research, was built. It must not therefore be used as a rigid framework, but rather as a flexible structure to be integrated into the creation, implementation and use of the IS of healthcare establishment.

3.1.1. Implementing the model on the major aims of an information system

This model is composed of 40 justifications that constitute the main aims of an IS. These are split equally across two clearly separate categories (see Tables 3.1 and 3.2):

- – Justifications of the purposes of the main aims of a healthcare IS (corresponding to the teleological dimension of our ethical analysis space), containing 10 characterizing the principle of beneficence and 10 representing the principle of justice.

- – Justifications of the limitations of the main aims of a healthcare IS (corresponding to the deontological dimension of our ethical analysis space), containing 10 characterizing the principle of autonomy and 10 representing the principle of non-maleficence.

These 40 actions composed of the four universal ethical principles have corresponding social values (which refer to the axiological dimension in the ethical analysis space), of which 4 are most significant1: respect for persons, preservation of social links, responsibility and social justice.

Thus, we feed these 40 items into our ethical model represented by the three-dimensional construction of the “ethical cube” (see Figure 2.5). The aim is to measure and compare the “unitary ethical score” of each of the four ethical principles with that of the “acceptable contingency” according to the actors and nature of IS in oncology. The challenge is to prove that our ethical analysis via our approach of “acceptable contingency” conforms to that of the four ethical principles considered as being a universal reference framework.

Table 3.1. Justifications of the purposes, fundamental principles and underlying social values to the main aims of a healthcare information system

| Justifications of the purposes of the main aims of a healthcare information system | Fundamental ethical principles | Associated social values |

| B1: Aiding medical decision-taking as described by the healthcare professional B2: Promoting quality, organization, management and planning of patients being taken into care B3: Working for the good of the patient | Beneficence | Respect for persons |

| B4: Sharing transparent and accessible information between the patient and the healthcare professional B5: Ensuring the quality and choice of information shared with the patient B6: Improving continued treatment B7: Sustaining monitoring of all healthcare activities | Preservation of social links | |

| B8: Aiding the Ministry of Health to respond to the expectations of patients with cancer and to provide support B9: Establishing legitimacy of rights and data management with the patient B10: Establishing an obligation for the security, integrity, traceability and protection of medical data | Responsibility | |

| J1: Evaluating performance and locating areas in which action is required by investigating existing faults J2: Efficiently directing the healthcare establishment by managing costs J3: Allowing for epidemiological or statistical analyses | Justice | Efficiency |

| J4: Improving and encouraging interactions with actors outside the healthcare establishment J5: Improving the availability of healthcare professionals | Preservation of social links | |

| J6: Facilitating user access to medical information: reducing social inequalities | Social justice | |

| J7: Respecting equal access and distribution of information rules regardless of the profile or status of the patient: notion of social justice | ||

| J8: Distributing the advantages and disadvantages of a tool fairly within a healthcare professional’s workload | ||

| J9: Sharing the same information and assistance to medical decision-making among all healthcare professionals involved in the patient’s care J10: Creating and sharing precise information appropriately adapted to all patients | Universality |

Table 3.2. Justifications of the limitations, fundamental principles and underlying social values of the main aims of a healthcare information system

| Justifications of the limitations of the main aims of a healthcare information system | Fundamental ethical principles | Associated social values |

| A1: Putting the patient back at the center of the decision by giving them more comprehensive and rapid medical information: better patient autonomy A2: Ensuring the consent and compliance of the patient A3: Respecting private life and the right to medical secrecy and confidentiality A4: Respecting the right to prior information, rectification and opposition as described in the “information technology and freedom” law A5: Reducing information asymmetry between the doctors and their patients: better equilibrium of the doctor–patient relationship A6: Reinforcing the transversality of services within the structure | Autonomy | Preservation of social links |

| A7: Establishing individual and/or collective use of medical information | Universality | |

| A8: Equating use of medical information with the organization of the healthcare establishment A9: Adapting technology to the knowledge and know-how of the healthcare professional | Respect of persons | |

| A10: Institution of a management and guidance policy on the use of medical information | Efficiency | |

| NM1: Following legislative regulations concerning medical data NM2: Respecting storage, hosting and distribution rules as established by the National Commission on Informatics and Liberties (NCIL) | Non-maleficence l | Universality |

| NM3: Maximizing the ethical quality of decisions and the concern for efficiency and organizational effectiveness of the use of medical information NM4: Developing an organization oriented toward collective performance | Efficiency | |

| NM5: Minimizing or eliminating harm caused to patients due to misinformation NM6: Possessing certainty that used methods must not exceed which is necessary to attain desired objectives NM7: Reducing useless or poorly calculated risks NM8: Ensuring the reliability and continuity of medical data collection NM9: Ensuring technical utility and human merits of the tool | Precaution | |

| NM10: Rendering user guidance a processthat is accountab the entirety of the healthcare establishment | Responsibility |

- – Creation of the unitary ethical score: this score is composed of the sum of the 40 items corresponding to the four ethical principles: autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence and justice. This total is out of 100.

- – Creation of the ethical score of acceptable contingency: this score corresponds to a more refined and detailed quantification of the unitary ethical score.

We must be aware of the values of the five necessary criteria used to evaluate the conditions of acceptable contingency focused on the search for meaning. These indicators are as follows: - – the teleological axis;

- – the deontological axis;

- – the axiological axis;

- – the focus on services to persons;

- – the focus on encouraging relations.

This score is calculated from the sum of the 86 items distributed according to the five indicators listed earlier (see Table 3.3).

Table 3.3. Distribution of the justification in the ethical cube of acceptable contingency

| Teleological axis | Deontological axis | Axiological axis | Services to persons | Encouraging relations | |

| B | B1–B2–B3–B4–B5 B6–B7–B8–B9–B10 | B1–B2–B3–B4–B5 B6–B7–B8–B9–B10 | B1–B3–B8–B9 | B2–B4–B5–B6–B7 | |

| J | J1–J2–J3–J4–J5 J6–J7–J8–J9–J10 | J4–J5–J6–J7–J8 | J4–J5–J6 | ||

| A | A1–A2–A3–A4–A5 A6–A7–A8–A9–A10 | A1–A2–A3–A4–A5 A6–A8–A9 | A3–A4–A9 | A1–A2–A5–A6–A10 | |

| NM | NM1–NM2–NM3–NM4–NM5 NM6–NM7–NM8–NM9–NM10 | NM10 | NM4–NM10 |

The dimension of the acceptable contingency translates the “ethical score of acceptable contingency” of analysis of IS in medical imagery into a score out of 100.

The utility of this model lies in its ability to perform a complete analysis of an IS and of the human–machine interface or “infosphere”, which combines technology and ethics. It represents, therefore, a tool used to translate between technical language and ethical language. Ethical modeling of a “human” IS must pass through this transformation and this genre change so as to go from being universal, abstract and general to practical, concrete and specific.

On the basis of this reasoning, we searched for the ideal representation that reconciles philosophy of thought and mathematical rigor so as to construct an algorithm for resolving ethical problems able to quantify this “ethical score” of acceptable contingency.

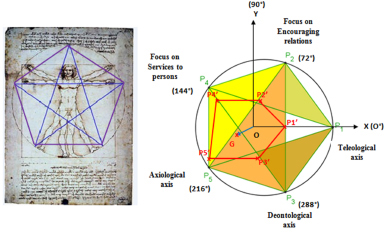

To accomplish this, we turned to Leonardo da Vinci and his Vitruvian Man (or Homo Universalis), which was the result of a study carried out on the proportions of the human body around 1492. This anatomical representation – possessing strong symbolic significance – is the synthesis of anatomic and scientific research. Desiring to show the unity of human proportions, this drawing represents the dual motion of the human body. This mobility allows for the extent of the symbolic value of this diagram. It does not attempt to show the ideal Man but instead displays the geometric model of a “normal” human, which is set within a circle and a square (see Figure 3.1). The circle is the symbol of Nature (macrocosm), infinity, the sky, universality and spirituality. The square represents the ancestral image of the Earth (microcosm), practicality and reason. The Temple is the intermediary between the self and the other, between the top and the bottom. Via the Temple, we obtain the “square of the circle”, representing the inseparable union of the spirit and the matter. The Vitruvian Man is within this Temple and he reaches the “square of the circle”, therefore, he is the said temple.

Figure 3.1. Geometric representations integrated within the sketch of the Vitruvian Man. For a color version of the figure, see www.iste.co.uk/beranger/ethics.zip

Thus for Leonardo da Vinci, the Vitruvian Man is an innate link between the divine spirit and matter. The balanced proportions and mathematical perfection of the drawing result in a representation of the Vitruvian Man as a pentagram within a circle (see blue section of Figure 3.1).

By joining each of the five points of the pentagram, we obtain a pentagon (see purple section of Figure 3.1). This shape contributes to the creation of a perfect geometric shape or golden ratio. In fact, the ratio between one of the sides of the pentagram and one of the sides of the pentagon is equal to 1.618034 = (1 + √5)/2 = Phi = φ, which is the golden ratio2.

Since antiquity, for many Roman, Jewish and Egyptian researchers, artists, mathematicians and philosophers, this geometric representation has symbolized universal perfection and harmony in the visible world. For the Greeks, and mainly for the Pythagorean school that Plato was a student of, this figure illustrates esthetic, geometric and philosophical perfection. It constitutes the link between abstract reflection and specific practices. Regardless of its interpretation throughout history, it has always been perceived as unifying, synonymous with knowledge, meaning and thus contingency.

Our model is, therefore, based on the geometric representation of a pentagon composed of the five criteria of our model (see the green section of Figure 3.2):

Figure 3.2. Implementation structure of an information system

- – P1: the teleological axis;

- – P2: the focus on encouraging relations;

- – P3: the deontological axis;

- – P4: the axiological axis;

- – P5: the focus on services to persons.

We describe our “ethical score of acceptable contingency” as the average of the sum of the unitary scores of each of the five parameters (P1′, P2′, P3′, P4′ and P5′):

Ethical score of acceptable contingency = (P1′+ P2′+ P3′+ P4′+ P5′)/5

We calculate standard deviation of this score so as to analyze the spread and possible homogeneity between the five axes.

After having inserted this pentagon into a trigonometric circle and having considered the teleological axis and the center O of the figure to be the x-axis, we can therefore infer the presence of a y-axis from an orthonormal frame. Using this new geometric reference point, we can calculate the coordinates of P1′, P2′, P3′, P4′ and P5′ (see the red section of Figure 3.1).

To accomplish this, we use the following formulae:

- – P1′:

XP1′ = unitary score of P1′ × COS O°

YP1′ = unitary score of P1′ × SIN O° - – P2′:

XP2′ = unitary score of P2′ × COS 72°

YP2′ = unitary score of P2′ × SIN 72° – P3′: - – P3′:

XP3′ = unitary score of P3′ × COS 288°

YP3′ = unitary score of P3′ × SIN 288° - – P4′:

XP4′ = unitary score of P4′ × COS 144°

YP4′ = unitary score of P4′ × SIN 144° – P5′: - – P5′:

XP5′ = unitary score of P5′ × COS 216°

YP5′ = unitary score of P5′ × SIN 216°

These five coordinates allow us to calculate the coordinates of the center of gravity (G)3 of the red polygon. We can then calculate how much this point is skewed toward any of the five variables from the distance OG. This corresponds to a uniformity test between the five variables. Specifically, the shorter the distance OG, the higher the equilibrium around the center O. In contrast, the greater the distance OG, the more the point will be skewed toward one or several of the five axes.

Moreover, the argument of the function, which is the angle GÔX (in degrees), describes the direction of the skew toward one or two axes. This represents the direction of the vector OG.

Thus, the coordinates of the center of gravity (G) of the red polygon are as follows:

XG = (XP1′+ XP2′+ XP3′+ XP4′+ XP5′)/5

YG = (YP1′ + YP2′ + YP3′ + YP4′ + YP5′)/5

The distance to the center is as follows: OG = √(XG2 + YG2)

The argument GOX is equivalent to:

- – if YG ≥ 0, then the angle GOX = arg(OG) = arccos(XG/OG); or

- – if YG < 0, then the angle GOX = arg(OG) = 360 – arccos(XG/OG).

Note: “arccos” is the function “arc-cosine”, which is the inverse of the cosine function.

Distribution of the ethical justifications: The 40 ethical justifications can be classed based on the different categories of real environmental parameters, from which we can establish the following (see Appendix 1):

- – 11 correspond to the strategic and methodological sector;

- – 11 belong to the organizational and regulatory domain;

- – 9 belong to the structural and technological domain;

- – 9 correspond to the relational and cultural sector.

It can be seen that all the real environmental parameters are represented homogeneously and in a balanced manner. This can be illustrated as shown in Table 3.4.

Table 3.4. Proportion of real environmental parameters within the fundamental ethical principles

| Political and strategic domain | Organizational and technological domain | |||

| Fundamental ethical principles | Strategic and methodological | Relational and cultural | Organizational and regulatory | Structural and technological |

| Beneficence | 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Justice | 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Autonomy | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Non-maleficence | 2 | 2 | 4 | 2 |

| Total of ethical justifications | 11 | 9 | 11 | 9 |

| 20 | 20 | |||

These justifications are crossed with the four fundamental ethical principles and their associated social values (corresponding to the axiological dimension in our ethical analysis space). After putting our model together, it can be seen that the fundamental ethical principles are grouped into two categories (see Appendix 1):

- – The principles that serve only to justify the purposes of the main aims of a healthcare IS:

- - “Beneficence”, which includes:

- – four justifications from the strategic and methodological domain;

- – two justifications belonging to the relational and cultural sector;

- – two justifications belonging to the structural and technological sector;

- – two justifications from the organizational and regulatory domain.

- - “Justice,” which includes

- – four justifications from the strategic and methodological domain;

- – two justifications belonging to the structural and technological sector;

- – two justifications from the organizational and regulatory domain;

- – two justifications belonging to the relational and cultural sector.

- - The principles whose sole purpose is to justify the limitations of the main aims of a healthcare IS:

- - “Autonomy”, which includes:

- – three justifications belonging to the relational and cultural sector;

- – three justifications belonging to the structural and technological sector;

- – three justifications from the organizational and regulatory domain;

- – one justification from the strategic and methodological domain.

- - “Non-maleficence”, which includes

- – four justifications from the organizational and regulatory domain;

- – two justifications from the strategic and methodological domain;

- – two justifications belonging to the structural and technological sector;

- – two justifications belonging to the relational and cultural sector.

- - “Beneficence”, which includes:

Thus, the justifications of the purposes made up of the principles of beneficence and justice are mainly associated with the teleological axis and therefore with the political and strategic sector of our three-dimensional ethical space.

Conversely, the justifications of the limitations including the principles of autonomy and non-maleficence are mainly linked to the deontological axis and therefore to the organizational and technological sector of our three-dimensional ethical space.

In these conditions, it is perfectly reasonable to suggest that the principles of beneficence and justice include 60% of their respective real environmental parameters of strategic and methodological nature, and of relational and cultural nature.

The same can be said for the principles of autonomy and non-maleficence, which also possess 60% of their respective real environmental parameters of structural and technological nature, and of organizational and regulatory nature.

3.1.2. Implementation of the model in the general creation of an information system

We will follow exactly the same process as used to analyze the aims. We will use the second questionnaire including 80 items dedicated to the study of the creation of an IS. Two items will be associated with an action linked to an aim. For example, item 1 of questionnaire 1 on the aims will be described by items 1-1 and 1-2 of questionnaire 2 on the creation of an IS, item 2 will be represented by items 2-1 and 2-2, and so on.

3.2. Presentation of the study’s questionnaires

Using publications in the field of anthropology, we have put together a maintenance framework that has allowed us to create semi-structured interviews with relevant stakeholders. By interpreting the data obtained from these interviews, we created first drafts of questionnaires that were given to a small number of healthcare professionals.

This, in turn, allowed us to modify and correct our tool before distributing it to the entirety of the stakeholders chosen to participate in our research.

These questionnaires allow for a database on the understanding of medical information ethics not only by healthcare professionals particularly aware of such issues in IS, but also by the creator of the IS, healthcare users and publishers of IT.

So as to successfully carry out our field research, we had to create three types of questionnaires:

- – a questionnaire dedicated to analyzing the perceptions of the stakeholders on the main aims of a healthcare IS. It was distributed to almost all4 the study stakeholders (see Appendixes 2 and 3);

- – a questionnaire dedicated to studying the creation and characteristics of the IS. It was distributed to the creators of the IS involved in the healthcare establishment being studied (see Appendix 4);

- – a questionnaire dedicated to analyzing the methods and tools put into place to enable the functioning of the IS. It was only given to the creator of the IS (see Appendix 5).

These three questionnaires allow us to see, among other things:

- – if there are any discrepancies between the aims and the final IS;

- – if the methods used for the creation, installation and use of an IS are real;

- – if there are discrepancies in the ethical perceptions of the different stakeholders involved with the IS;

- – if the market demand is in line with the ethical demands of the creators and users of IS.

With the law of March 4, 2002, relative to rights of patients and the quality of the healthcare system, legislators dedicate a certain number of questions that now reveal good practices within a healthcare establishment. These are usually based on the use of medical information, decision-making guidance, sharing of responsibilities, etc. Such ethical approaches justify initiative that need to be made while considering the reality of the situation on the ground. This questionnaire was prepared on the basis of a significant amount of literature review on the subject, as well as from information derived fromsemi-structured interviews with various stakeholders so as to provide better understanding and improve its creation.

These research interviews correspond to a particular face-to-face situation, that is to say a technique for the collection of spoken information that is produced during social interaction between the researcher and researched. They can be considered as an exploratory technique because the aim of the interview is to understand how the individuals being questioned live their situation and what the questions they ask themselves are. For the purpose of our study, we will use a reasonably flexible structure containing several themes, which is where the term “semi-structured” stems from. The interview will have its own dynamic and a set of questions tailored to the individual.

As such, the use of a questionnaire aims to explain a certain number of practices, to identify what individuals are thinking and to locate their position within social space. An essentially explanatory approach is adopted in the search of explanatory factors. Social factors must be treated as real. Explanatory factors must always be sought after.

The methods used for the creation and analysis of the survey are as follows:

- – The researcher conducts a semi-structured interview and provides a questionnaire to be completed by the stakeholders.

- – The main developer identifies the users said to be “internal” to the IS.

- – Spaces used for free responses to questions allow these to be refined or specified.

- – The interview with the stakeholders on the state of the IS represents the qualitative aspect of the study.

- – Responses are recorded anonymously.

- – Comments made by the stakeholders are quoted in between quotation marks and in italics.

- – The presence of removed sections of quotes is represented as follows: […].

- – Words inserted into quotes so as to give context to the statement will be indicated as follows: [author’s comment].

- – The majority of the questionnaires are numerically weighted and scored based on the following rules:

- - The response “Yes, certainly” is worth 3 points.

- - The response “Yes, partly” is worth 2 points.

- - The response “No, not really” is worth 1 point.

- - The response “No, not at all” is worth 0 points.

- – This weighting of the answers will be applied for the two questionnaires dedicated to the analysis of the aims of an IS and its creation.

- – The third questionnaire dedicated to studying the methods has its responses weighted more simply: “Yes, completely”, “Yes, partly” and “No, not at all” are worth 2, 1 and 0 points, respectively.

- – The results will be expressed as a total score out of 100 or as a unitary score out of 3 (or 2 for the third questionnaire).

- – We consider that a stakeholder takes an ethical principle into account when a score of more than 66.66 of 100 is attained, which is two-thirds of the maximum score. We will use this number as a reference point because the answer “Yes, partly” is worth 2 of 3 possible points.

3.3. Necessary environmental changes for healthcare information systems: recommendations and actions

For about 20 years, constant development of ICTs in the field of healthcare has been contributing to bringing a new access space to medical data for doctors and patients. Doctors are more and more favorable towords the development of computing tools useful to the practice of medicine. As a result, this establishes a new dimension of medical practice as long as each protagonist can access medical information or perform therapeutic and/or diagnostic procedures via an IS. The Internet does pose several security and technical threats, but it is particularly liable to cause cultural shock as the hospital can no longer consider itself to be the center of the world but instead as a satellite provider. These ICTs then result in questions of a societal nature, and these come not only from the ever-growing number of healthcare users but also from traditional creators of health-related information, such as healthcare professionals.

How can healthcare professionals be better prepared to use these new technologies? How can the development of the concept of sharing or co-management of medical decisions be encouraged? Are IS facilitating elements or are they instead an obstacle to the doctor–patient relationship? Will the Internet soon become key to the automatic management of patients, perhaps almost entirely removing the need for “family” doctors [SCH 09]?. Finally, will the very value of medical secrecy, initially created to protect patients, be put into question?

All these questions lead us to logically consider what the necessary environmental changes will be in order to enable an optimal functioning of IS in hospitals.

Most of the methods for organizational change fail because they do not begin at the beginning, that is to say by basing themselves on the very essence of the singular nature of the situation and the initial aims that result from it. The utility of an IS lies less in its concept than it does in its execution. The issue relates to the almost universal difficulty of obtaining continuous performance. The solution therefore lies in the suitable alignment and creation of the aims of the user and the organization, so as to achieve a genuine change of culture and structure, which is based on performance and information.

From this observation, the statement of an aim must be simple, immediately understandable by all and precisely formulated, without ambiguity and such that no confusion may arise in achieving a unique goal. The recommendations made or actions performed in the context of achieving an aim must be quantifiable. The goal must be linked to a specific and precise context. Knowing that a goal is attainable allows individuals to give themselves the means to reach it. All goals considered to be realistic must include internal data (numeric analyses) and external data (economic or financial context).

What will allow me, specifically, to check that I have achieved my objective? What context is necessary to the correct achievement of the said goal? With whom? When? Where? According to what plan? How is the goal even important? What is the price to pay for achieving this goal (money, time, energy, etc.)? What advantages or disadvantages does achieving this goal create?

Having presented the different ethical problems surrounding the lifecycle of an IS from a theoretical perspective, beginning from its creation, its setup and then its final use, it is now time for us to remove this information in order to put together a summary in the form of questions and reflections on the subject.

In this section, we will address a reflection on what an IS that can satisfy our current and future needs should be. This section will include recommendations and strategies grouped depending on the nature of their content, whether from a structural, technological, methodological, organizational, relational or cultural point of view. This will all contribute to projecting us into a reflection on the construction and use of an ideal computing tool created by private software developers.

Finally, we undertook an opinion survey with healthcare professionals from the “AP-HM”, the Assistance Publique – Hôpitaux de Marseille or Public Assistance – Hospitals of Marseille. This survey was conducted on the recommendation of systems to be put into place as well as on the new perspectives that our publication has brought.

As we have previously seen, ethical questioning must guide humanity in the management of medical information as well as in the research of the behavior most concurrent with the impression it has of itself. Faced with new knowledge, how are new decisions and choices to be made and how are new liberties to be given while also assigning new responsibilities? How is the most just equilibrium between society’s demands and the respect of the individual found? How do we settle this conflict of interest and structure common rules for a pluralistic organization that does not always comprehend the same cultural, moral or philosophical standpoints? Who is the actual owner of medical data? In the sense that propriety lies in the ability to possess and use something in an exclusive and absolute manner restricted only by the rules established by legislation.

All these questions will be answered in this section by presenting the preoccupations and aims of the stakeholders involved with the IS.

This suggestion grid allows for a more pedagogical and specific approach. Indeed, the standards and rules determine which actions are undertaken surrounding a decision. The term “rule” suggests something more concrete, closer to the action. The principle of it is often undetermined and allows for various applications. A rule has a precise content. Rules can be numerous and variable.

This grid can be applied prior to beginning a project intent on creating an IS, allowing it to be better integrated within the organization of the healthcare establishment as well as within the definition of technical constraints.

The aim of this chapter is, therefore, to establish recommendations in the form of actions on the implementation, use, methods and means necessary to ensure optimal operation of the IS in a hospital.

3.3.1. From a structural and technological perspective

Practically speaking, three elements are important for the success of the digitization of a radiology department: suitable technical characteristics, taking into account the sequentiality of tasks undertaken within the department, and the use of project management techniques for the implementation process. It is essential that an ergonomic tool that does not require much knowledge or training to be recommended for general use.

The creation of an IS depends on technical factors more or less associated with each other, whose complexity requires the need for a “computer scientist–networkengineer” whose role is to respond to the requirements listed below while ensuring their adequacy with the existing computing setup or a setup in the process of being built [COU 04]:

- – addressing the procedures;

- – security of the computer network;

- – adapted topology of the IS;

- – number of users;

- – applications (intranet, database server, etc.);

- – data type (data weight) and flow (data quantity);

- – ability to bring together the procedures of different developers.

Globally, the integration of an IS can be achieved via the intermediary of an “integrated” offer proposed by a single developer, or assembling elements from different developers. In the first case, we refer to a single-developer system in which the interactions are regulated by proprietary protocols whereas the second refers to a multi-developer solution, based on the use of standards such as DICOM or IHM (see Table 3.5).

Generally speaking, most developers (notably PACS – Picture Archiving and Communication System) have turned toward the second approach “as indicated by their active collaboration with work to standardize DICOM and IHE” [GIB 05].

Table 3.5. Advantages and disadvantages of single- or multi-developer approaches

| Single-developer approach | Multi-developer approach | ||

| For the user | Advantages | – Potentially more effective solution | – Liberty to choose suppliers |

| – Choice of the best of the generation (“best of breed”) for each component | |||

| – Sustainability and scalability of the solution | |||

| Disadvantages | – Disparate levels of quality | – Must manage the issue of integration themselves | |

| – Difficult to improve the system | |||

| For the entrepreneur | Advantages | – Flexibility with regard to technical innovations | – Ability to integrate with a large number of suppliers |

| – Captive customers | – Sustainability and low costs of the solution | ||

| – Ability to cover functional aspects not part of their main skill set | |||

| Disadvantages | – Risks lacking being competitive, or not satisfying customer expectations (who often desire multi-developer solutions) | – All customers are free to choose | |

Moreover, according to “Clusif” (Club for French Information Security), to design a coherent security system, the following are essential [BAL 06]:

- – now the entire IT application is organized around the workflow, that is to say the professional work process: welcome, review, interpretation, reporting, dissemination clinicians, archiving, etc. [DEC 06];

- – managing security, notably by analyzing incidents and rapidly responding to emergent risks, by adapting to the evolution of threats, etc.;

- – being familiar with all the installed hardware;

- – identifying all access and communication points of the information system;

- – covering a wider perimeter than that dictated by the premises of the organization;

- – having a backup system and a continuity plan.

In addition, in the light of different interviews conducted with “internal” users of healthcare establishments, it appears that the structural setup of an IS is a compromise between:

- – a decentralized network: location of substantial communication. There is no resulting leader and its layout is not particularly efficient. It usually results in a greater number of errors. For this reason, adding an adapted and high-performanceIS renders this setup most adequate for taking patients into care within a healthcare establishment. This type of structure is appreciated by all its members because they feel involved in actions undertaken; and

- – a “combined” model that consists of converting different specific knowledge into a more complex system of specific knowledge, able to be offered to many individuals within and outside the organization. It includes collection, processing, validation, testing and distribution of knowledge. This architecture allows for excellent ICT integration and use.

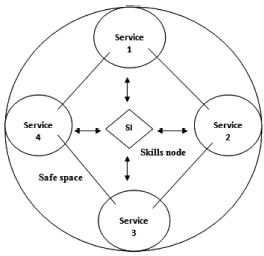

This new implementation structure will be made up of a “safe space” representing the geographical location where the different services involved in the healthcare establishment interact. The IS will be located at the center of this space. An informal communication system is put in place between the IS and the services that make up this space. The interdisciplinarity is therefore represented by spontaneous and flexible links established between the different skills necessary to the functioning of the formal part of the organization. These links form a “skills node” between the IS and the services involved.

The flows of the operational work of health professionals travel in this space. The data integrated within the organization of this area can be stored and then analyzed in the central IS of the governing body of the healthcare establishment via information reporting. This IS aims to centralize the information such that the activities of the different nodes that make up the healthcare establishment can be regulated and controlled (see Figure 3.2).

The implementation of an IS must be accompanied by the setup of a physical space allowing for the creation of informal networks. This includes installation of intranets, newsletters or any other methods allowing individuals to inform themselves and share their working techniques with the IS.

Ultimately, the recommendations for this sector can be summarized as given in Table 3.6.

Table 3.6. Recommendations for the structural and technological domain

| 20 Actions |

| – Establish an IT setup that is suitable and coherent with the organization of healthcare – Have a backup system, an emergency plan and a continuity plan for the IS – Identify and prepare for potential IT threats – Be familiar with all installed hardware so as to create a suitable guidance policy – Cover a wider perimeter than that dictated by the premises of the organization – Identify and order all the challenges and risks associated with the IS – Install the IS at the center of the space that makes up the services involved in the management of targeted treatments – Obtain data with the use of a standardized interface adapted to the user (doctor or patient) – Use reliable knowledge (business rules, computational algorithms) originating from its own knowledge base or from other known databases – Be able to communicate the results of applying rules to patient data to the user in the form of alerts, recommendations, reminders, etc. as well as to its applied environment (prescription system, digitized patient records, etc.) – Construct a technical IS that is comprehensible, useful and easy to use (according to users) – Embed uniform technological reference solutions that are in line with any regulations in effect (DICOM, HL7, etc.) – Create a flexible, adaptable and evolving IS – Insert procedures within the IS that allow patient identity to be kept anonymous – Include good practice protocols within the IT setup – Set up supervision and surveillance mechanisms – Ensure that the IS is monitoredsuch that an alarm can be raised in case of malfunction – Install a system for exporting data (for the State or its governing bodies) – Install a system for exporting epidemiologic data of public health (for the State or its governing bodies) – Add internal human resources charged with regularly monitoring the IS |

Finally, such procedures must be accompanied by strategic and methodological modifications and adjustments.

3.3.2. From a strategic and methodological perspective

Ethics have become an essential element in the way in which IS engineers approach the creation and use of such a tool. Nowadays, there are many who adopt an approach including the following:

- – defining the conditions of sustainability and development of the IS;

- – listing the risks, challenges and dangers that the tool might face;

- – constructing a system of values unique to the IS and its users;

- – creating norms and a code of conduct for its usage;

- – promoting and installing the entirety of the IT setup.

The procedure that we will describe here allows for an ethical dimension to be integrated with the use of medical information by a healthcare professional. This methodological aspect is built on interdisciplinary considerations, as they model the reality of patient care most closely. This procedure has been greatly influenced by the article of Saint-Arnaud entitled “The reflective and interdisciplinary approach to healthcare ethics: a tool for the integration of knowledge and practices” [SAI 07].

This is made up of 10 distinct stages:

- – Identifying the ethical and medical challenges faced: with regard to identifying the challenges in question, the stakeholders involved are invited to describe their perceptions of the problems that they are faced with. Ethical issues are often recognizable due to the emotions they cause. These challenges will be integrated into the learning objectives of the IS for timetable planning, general planning and organizational strategy.

- – Collecting information on the facts of the situation, and identifying those that are relevant to the challenges to be analyzed: ethical decisions do not arise from facts, but they must nonetheless be built on a correct understanding of the facts so as to be pertinent and realistic. It is therefore necessary to research and synthesize information of different origins (therapeutic, psychological, etc.) that surrounds these issues.

- – Listing the individuals involved, their missions and their goals: the individuals involved in taking the patient into care must be identified and those that referred the patients to them must be found such that dialogue between the various parties is facilitated.

The proper progress of a project must pass by defining and identifying the roles of each entity involved with the project management and implementation. A project group bringing together the project managers must as such meet when necessary so as to resolve the conflict linked to the requirements of the proceeding or coordination of the project. This description of tasks must be done for the legitimacy of the IS to be recognized.

- – Identifying the different possible options in terms of interventions: listing the decisions or stages that lead to the issue, but also examining the possible options considering the issue in question. These options are suggested by the parties involved, argued on and discussed in multidisciplinary encounters. During this stage, it is necessary to identify the obstacles to this ethical learning and to develop methods for overcoming them.

- – Identifying the legal, social, deontological, institutional and governmental norms and constraints: at this stage, the norms and constraints that are relevant to the study context are to be identified. The norms give details on what behaviors are or are not accepted. They represent the institutional memory of standards regulating society’s conduct and aid ethical decision-making. Nonetheless, they can also be representative of obstacles to ethical intervention in some cases, when the constraints imposed conflict with requirements of other standards or with the moral obligations created by ethical principles.

- – Identifying the guidelines, case studies, ethical principles and theories that can provide tools for analyzing and reducing the number of errors of the situation in question: these ethical principles and theories reveal ethical competence that itself arises from the field of philosophy. This is a dialectical approach, which examines the possible options based on the facts and appropriate ethical reference points. In this approach, the beneficiary is associated with reflection and the choice of the solution by defaultso as to suggest path or compromises that respect the ethical norms, principles and views and will to agreement. For us at least, the principles that represent the expression of a deontological theory constitute one of the components of the ethical dimension of decision-making. They must be associated with the ethical issues that correspond to the attitudes and feelings of the stakeholders based on theories of virtue, the relationship between healer and healed based on the ethics of “caring” or the theories of fundamental rights based on nature or reason 5 as seen throughout the course of our study.

- – Analyzing by establishing links between relevant facts and appropriate ethical reference points bearing the problematic situation in mind: the ethical principles in question are those of autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence and justice, as previously integrated within our ethical model. They must be explained based on the purpose of the healthcare sector and the problematic situations that these encounter. They imply a moral obligation for healthcare professionals.

- – Suggesting an ethically acceptable framework and discussing this with the parties concerned to reach consensus on a code of ethics to be instigated: it is in this phase that the four fundamental ethical principles of our conceptual framework enter into play. This stage is aimed at avoiding that power games develop and that the code does not serve any interest other than that of the patient’s well-being.

- – Implementing the code of ethics: this ethical reference document has the aim of advising healthcare professionals as well as the creator of the IS to integrate ethical behaviors into their daily work with the system. This code is therefore relevant to all the internal users as well as the professionals that are involved in the creation and implementation of the IS. For this reason, it is necessary to integrate these recommendations within the existing procedures.

- – Evaluating the intervention and documenting it in a report: this final step addresses the assessment and drafting of a report that serves as the memory of the healthcare establishment using the code of ethics. Over time, this will come to make up the organization’s own philosophy. Human resources–related mechanisms can be used for this purpose, as well as for supervision and assessment of the staff so as to ensure monitoring and assessment of individual contributions to teaching the IS. Supervising the implementation of an IS requires simultaneous implementation of a schedule designed to receive feedback on a daily basis such that all users can express any difficulties they face.

Furthermore, according to the “Clusif”, the control and protection of information requires action such as:

- – identifying vulnerabilities, both those relative to technology but also those relating to various human, organizational or physical factors used by the organization;

- – selecting which information requires protection;

- – defining and assessing acceptable risk levels, bearing in mind their consequences as well as the costs and constraints resulting from reducing them;

- – ensuring that all measures put into place are proportional to the value of the information in question, both in terms of acceptable costs but also such that communication possibilities are not endangered and without imposing disproportionate constraints on users;

- – opting for a comprehensive and consistent approach;

- – stopping classification rules of information and the terms of distribution, operating conditions, storage and destruction;

- – not limiting oneself to protecting information exclusively within the organization but also any information that enters, exits or orbits it. [BAL 06]

Furthermore, the quality of the IT tool is a direct result of specifically adapted management combined with an established decision process. For this reason, we believe it is important for certain key reflective elements and techniques that contribute to improving the quality of an IS to be highlighted:

- – supplier choices;

- – role distribution;

- – cost distribution;

- – security and access rights monitoring;

- – data integration;

- – data backup;

- – network monitoring;

- – hardware monitoring;

- – user assistance and ease of use;

- – IT department’s ensured technical competence;

- – study, research and development implementation.

Finally, this new strategic and methodological focus contributes to increasing the dissemination of internal information while making it more relevant to the coordination of collective patient healthcare within a healthcare establishment.

For this reason, IS-related methods must evolve so as to include and return reliable and relevant medical information while tending toward greater interconnectivity of information, resulting in a decisive IT network and excellent collective performance.

Ultimately, the recommendations and suggested courses of action for this sector can be summarized as shown in Table 3.7.

Table 3.7. Recommendations for the strategic and methodological domain

| 20 Actions |

| – Establish an adapted management, accompanied by an established decision-making process – Identify the ethical and medical challenges associated with patient rights in the IS – List patient needs relating to the nature, quality and quantity of medical information shared by the IS – Collect, identify and (statistically) analyze information of facts relevant to taking patients into care – List the individuals affected by the IS, their missions, their goals and their levels of access to medical information – Calculate the impact of the IS on the daily workload of healthcare professionals – Enforce a rigorous and evolving security policy – Identify the different possible options for the healthcare professional to act on the IS – Ensure patient participation in the choice of the medical decision that will be taken – Transmit as much concise and essential information as possible to the patient via the IS – Establish links between relevant facts and the IS’ ethical reference points that are applicable to the patient – Suggest a reasonable ethical framework on the acquisition and accessibility criteria of medical information by the patient – Implement a code of ethics on the handling of medical data around the patient – Assess healthcare interventions and publically document them using reports – Carry out a retrospective study on the evolution of the methods put into place compared to the initially envisaged objectives – Create an information master plan of the IS based on the existing version – Develop a comprehensive project methodology centered on the IS – Create a steering committee for the IS – Create a monitoring committee for the IS – Use planning techniques (Pert, Gantt, History Network, MPM, dashboards, activity indicators and assessment criteria) |

Here, it can be clearly seen that the challenges to IS are significant. Our passive IS require tending toward greater interoperability with the real world. It is for this reason that ICTs require greater involvement in organization and regulations in these conditions.

3.3.3. From an organizational and regulatory perspective

Organizations allow for individual behaviors to tend toward a common goal. They register their existence and activity within an environment undergoing continual change. ICTs cause organizational changes at the level of technological structures and human management methods. This refers to the socio-technical school of thought emerging from the research conducted by Eric Trist at the Tavistock Institute of London and by Einar Thorsrud in Norway.

It is based on the observation the group work depends on both technology and group behavior. An organization is at once a social and a technical system, which means that it is a socio-technical system. Creating an information system is a mutual transformation process wherein organization and technology are simultaneously transformed during the implementation process. This process is part of a greater strategy leading to the transformation of an organization. According to the socio-technological approach [BER 01], this is a mutual transformation process. The IS should contribute to the transformation of primary and secondary tasks.

In these conditions, a specific action plan must be put in place so that various stakeholders can work together to solve the issues raised by adjusting the organization to its environment.

Within healthcare establishments, the IS are on the whole created to exchange relevant information in order to prepare for various activities, such as providing the best possible patient care or publishing and distributing information to patients. They must contribute to organizational decisions, such as medical or long-term management decisions. In this way, information tools have the purpose of improving the consistency of the institution: their implementation implies a “precise analysis of the organization of different processes concurrent to the conducting of an imaging exam and the transmission of its results (workflows)” [BRU 07]. Henceforth, all of the computer application is organized around the workflow, that is to say, the professional work process: reception, examination, interpretation, report, distribution to clinicians, archiving, etc. [DEC 06].

According to Abbad [ABB 01], “driving change only makes sense in the search of a new organization that places mankind at the center of its concerns”. The keys to this change rely on organization and management. This organization allows for unsuitable life or work attitudes to be corrected and refined as well as to manage costs. It is studied from the point of view of different parameters that it covers: its borders, structure, specialization, distribution of power, coordination methods, mission, identity, culture, etc.

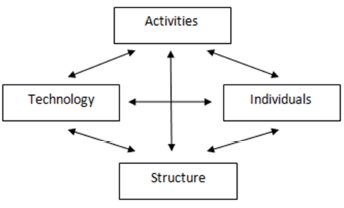

Moreover, all activities of an organization are just a chain of interactions and communications processes: they are the oil that allows for the organizational cogs to function. Generally speaking, the science of organization represents an interaction between four forces: technology, activities, individuals and structure (see Figure 3.3).

Figure 3.3. Forces that characterize organization

Architecture of an IS must be relevant to the organization of the healthcare structure already in place. To accomplish this, we deem it necessary to cover the various aspects of an IS organization:

- – Functional: the IS comprises software applications considered to be “vertical”, which is to say that they serve to respond to overall requirements, and of professionals, who add technical value.

- – Integrational: this is the driver of communication. The aim here is to have all interfaces converge in a single point. These interfaces make up the foundation of the IS. This also includes integration of PACSs or other medical storage systems within the existing IS, whether at departmental level or for the whole establishment.

An IS is a setup that evolves across time and whose interfaces are not always defined by standards. When choosing a product (notably a PACS), it is extremely important to be vigilant and choose the product that conforms the most to current standards (such as DICOM and HL-7 in medicine). It is essential to choose a developer that is able to integrate the setup with the IS.

- – Consolidation: the creator of the IS must identify the source of reference information.

- – Distribution: this can be illustrated by an intranet. This transmission of information is characterized by:

- - standardization of the user interface;

- - technical flexibility;

- - a system unaffected by the number of accessed servers and the number of applications used;

- - adaptability;

- - a system unaffected by the physical location of servers;

- - an array of services allowing for messaging, discussion forums, database access, image/video visualization, audio transfer, etc. to be combined.

- – Coordination: this is resource management. Beyond the vertical division of services within the healthcare establishment and the transversal division by general use tools (such as the Internet messaging or the Internet access), there is space for tools that partially cross both axes, which are known as “virtual communities”.

Coordination refers to a setup of fluid virtual structures based on relational and expertise-based networks, and on intelligent use of human and technical resources. A database server can be considered to be an active member of a study group.

- – Cooperation: this has the aim of:

- - obtaining better project organization and management;

- - possessing as much available knowledge as possible;

- - harmonizing decisions (coordination and synchronization);

- - contributing to the integration and control of many trades involved in the project (reciprocal learning).

The collective action of an organization requires to be based around task specialization [PED 04] in which each individual does that which he or she is best at. This model can work only if a function, that of coordination and interrelational communication, is constantly active.

According to the Comité Consultatif National d’Ethique or National Ethics Consultation Committee (CCNE), the spirit of cooperation is a key measure of success of a new approach. The users of an IS must feel involved and integrate as much in the creation of protocols as in the coordination of working groups.

- – Federative level: This corresponds to an opening onto the world and expansion toward it.

Furthermore, all large human organizations require numerous individuals in different categories work together coherently while following any applicable rules or laws. This is all the more true for a healthcare establishment in which the terms “multiplicity” and “multi-professionalism” are key words. According to Fessler and Grémy [FES 01], the collective characteristics involve defining and respecting common goals, rules of life, duties and rights.

In this sense, ethics leads to many definitions. In these conditions, the creation and use of an IS must answer to three “keys” at the organizational level of a healthcare establishment:

- – The first key corresponds to the shared belief that an IS,above everything else,is a tool for social coherence within the institution.

- – The second key constitutes a veritable democratic debate between all the stakeholders involved. Such a debate is democratic both due to the transparency of its content and due to the reliable manner in which it is led. It involves multi-professional reflection and a process that defines, accepts and puts the collective goals into action. It therefore requires common semantics, a timetable of the specific goals that have to be carried out successively, the rights and duties to access treatment results, and appropriate regulations.

Such agreements and procedures cannot be obtained without mutual respect between the different stakeholders directly or indirectly involved with the IS. They cannot, therefore, be arrived at without frank and honest discussions theoretically leading to mutual trust.

- – The third key represents the belief that all have a common obligation that transcends their individual professional ambitions: to construct a structure and system centered on the patient, within which healthcare quality, respect for others and consideration of patient desires and wishes are permanent and simultaneously considered by all stakeholders.

Clearly, the collective preoccupations of a healthcare establishment have a significant impact on the creation, setup and use of an IS. Certain tools and specific methods can be useful for the execution of these “keys”, such as

- – auditing systems;

- – referral centers for good information practices;

- – specific ethical charter issuance;

- – ethical information committees for resolving specific cases;

- – organization of intranet forums;

- – models allowing for future issues to be anticipated;

- – multidisciplinary teams to develop the guidelines, procedures and policies to be implemented;

- – a liaison position to support the management and transmission of knowledge and use of the IS;

- – a scope statement considering the current setup of the healthcare establishment, allowing it to evolve in such a way that it mirrors the IS6;

- – a training plan for the project management and the project owner to have a common language and develop a project method, conducting interviews or meetings, etc.;

- – a well-identified project manager who is supported by the management offices. It must be an individual convinced that the project will succeed and who believes that the IS will be beneficial. They will motivate the organization and their enthusiasm shall win the support of even the most reluctant. From this point of view, supporting the hierarchy is a kind of legitimacy guarantee;

- – services associated with the delivery of the IT product (connecting to the existing network, training, operation).

In the context of an ethical reflection on the organization, collective action cannot be removed from the concept of subsidiarity that designates the same social reality but oriented toward the principle of justice. This notion is therefore based on the values of liberty and responsibility of each individual relative to society. As was highlighted by Patrick Pirazzoli in 19957 during a university/industry dialogue on the theme of the spread of new technology and the analysis of consequences, “ethics cannot be the business of the structure. It is the responsibility of every individual” [HER 96].

The importance of personal imitative is therefore highlighted, thus overturning the common concept of authority within the division of labor. The association of the principle of subsidiarity applied to collective action shows that the latter is as much a question of justice as of performance. The purpose of hierarchical authority is to contribute to the common well-being by allowing the individuals concerned to state their skills, abilities and talents, and to reveal their sense of initiative.

However, the improvement of an organization has the aim of creating a convergence of different interests and to orient itself toward the personal fulfillment of individuals. It is therefore responsible for intrinsic elements. According to Hertzberg’s theory, when all these intrinsic factors are positive, they have the ability to motivate individuals. The efficiency of organization results from rigorous management and regulation, among other things. This hospital management must be applied to information security with the apparition and institutionalization of healthcare data, measure of how optimized the healthcare quality is.

An organization is the harmonious and optimal implementation of means (installations and equipment) and resources (human and financial) so as to carry out a mission and permanently offer services that conform to needs. Its role is to produce goods and expected services for the best price, at the right time.

Ultimately, the success of organization within a healthcare establishment partly relies on the convergence of several factors, such as the assertion of participatory management, service and technology quality, the professionalism of the social body and the management style of human resources. According to the Comité National de l’Organisation Française or National Committee of French Organization 8, “the introduction of new techniques will only be successful if it is accompanied by a change deep within management styles, both at the level of the organization of the company and at the level of management methods and the involvement of men at work”.

It would be ideal to create a culture said to be “rational and organic”, in which a company is split into several result centers each having its own aims and abilities to assess the efficiency of managers. Responsibilities are decentralized from a project manager who takes the expectations and recommendations of the user base into account.

The organizational chart, which defines entities and their superiors, is the centerpiece of an organization. It must be sufficiently stable over time such that commitments and results can be confronted. Hierarchical control is based on past events and responds to malfunctions by adapting processes. Responsibility is decentralized to the project manager and those undertaking the implementation. The staff are molded by working. The qualities expected of them are adaptability (being able to activate many processes), common sense (making decisions in specific cases) and the spirit of responsibility (taking responsibility for decisions without worry).

Ultimately, the recommendations for this sector can be summarized as shown in Table 3.8.

Table 3.8. Recommendations for the organizational and legislative domain

| 20 Actions |

| – Create the architecture of the IS following the existing organization of healthcare – Create a liaison position with the exterior to support the management and transmission of knowledge and use of the IS – Create a scope statement that takes into account the methods used for distributing medical information via the IS – Establish a training program allowing for the project management and the project owner to have a common language around the IS – Apply data storage and hosting rules as instituted by the CNIL – Apply medical information distribution rules as instituted by the CNIL – Control the processes put into place for the IS hierarchically – Deploy specific management techniques and means, accessible to all tiers of the organization and adapted to the decision-making level so as to focus on overall performance – Establish 24/7 maintenance (maintenance contract) – Bring preliminary information on the progress of patient healthcare via the IS – Define the aims of the IS based on the analysis of user needs and the characteristics of the problems faced; – Integrate the IS in the communications setup so as to become one of the partners and participate in resolving actions (doctor–patient–IS triangulation) – Install the intranet within the healthcare structure – Develop an interface for exchanging and sharing information that refers to the IS between the doctor and the patient – Identify and conceal any personal information that is not required for the patient’s care in the IS – Identify and choose exchanged data to favor inter-service communications – Carry out structural and organizational changes (organizational charts, superiors, etc.) to accompany the implementation of the IS – Identify the legal, social, deontological, institutional and governmental norms and constraints – Apply the legal, social, deontological, institutional and governmental norms and constraints that concern information access |

Finally, the successful implementation of an IS does not rely only on organizational and legislative characteristics. Relational elements must also be considered in order to develop a true human–IS culture. Thus, the success of an IS fundamentally depends on the quality of the individuals concerned and their management of the tool.

3.3.4. From a relational and cultural perspective

The computerization of a healthcare establishment can be seen not only through technical modifications but also by a perturbation of the entirety of human relationships insofar as IT impacts on the main influential factor, that is, information. The technical setup cannot substitute for human relationships, which remain essential for an optimal medical organization. The relationship between technology and behavior when using the system is unpredictable.

According to Oumar Bagayoko et al. [OUM 08], “an individual, being a physical person, is at the heart of issues surrounding information systems”.

Any IS can be a source of conflict and disorder between individuals. For this reason, such a process cannot be developed without the consent and approval of senior management and future users of the tool [BER 01]. In fact, all the choices established within a collective IS depend on the views that the creators have of the types of relationships that exist between users, both among them and the managers. These social, ideological and cultural choices have strong ethical connotations: the division of labor and rights between members of staff, conforming to the general aims of the organization.

When an IS is built for a specific category of professionals, considerable risk would be involved in believing that it can be built for them while ignoring the aims and interests of others. This is particularly important in the case of medical information systems, but even more so in management information systems.

Thus, medical specialization is reflective of the omnipresence of the therapeutic act for which human relationship techniques should not be added. It is this approach that we develop throughout this section. The concept of simplicity via relationships goes against the technical belief that complexity is born from the processes within systems.

Communication is ambivalent. It is not perfect, as parts of individual experience cannot be communicated. However, it is the richest element without which life in organized societies, which rely on exchanges, would be inconceivable. Relational communication is a key activity of the life of an organization that we have seen previously. It must continuously guarantee the correct communication of an organizational project with the strategy of human resources and the action plans put into place.

It therefore becomes a fundamental and operational tool for overseeing change, incentivizing social dialogue. This instrument puts at least three parameters into play: its form, its content and its users (producer and consumers).

On the basis of this characteristic, the psychology of communication must articulate three levels, that of

- – the subject: its motivations and cognitive and emotional functions;

- – interaction and its relational dynamics;

- – the social context: its norms, rituals and roles.

This communication is involved in the search for a relational equilibrium favoring cooperation and individual development. It also becomes one of the solutions for breaking the extremely hierarchical partitioning of the structure put into question so as to ensure better patient care.

In these conditions of equilibrium and relational harmony, individual morals are associated with collective reason so as to better resolve medical ethics issues. In the current case, reason is therefore not in opposition to morals, it merely facilitates their expression [MIC 07]. According to Abbad [ABB 01], this social communication is essential for the growth, development and affirmation of each organization. It contributes to nourishing a corporate culture characterized by a system of values, norms and concepts. According to him, the structure of a social dialogue contributes to

- – organizing reflection and defining projects;

- – enriching and reinforcing inter-professional relations;

- – encouraging staff adhesion;

- – developing social dialogue.

To interpret the behavior of communicating individuals, we must seek to understand the meaning that they are giving to their actions. This meaning is the product of an interaction between the act of communication and all the other elements that form this context. It results in various parameters such as the physical and sensory environment, spatial organization, temporal data, norms, positioning processes of individuals and the expression of identity, fundamental to “relational quality”. Through this complex combination of process criteria, a system is thus formed, which the individual will give meaning to their way of communicating and behaving.

For this reason, the first challenge is the “creation of shared meaning” and organization is an integral part in this situation.

Thus, it is essential to rely on as many multidisciplinary working groups as possible. These allow for a stronger dynamic to be created around the computerization project and facilitate the adherence of a vast user base by involving them in the implementation process.

Moreover, culture is one of the results of a learning process that an individual uses to understand, assimilate and respond to the world around him or her. It is social in nature and is a key process for developing the capacities of individuals and organizations. The IS usually reflect the values of the healthcare establishment. This cultural vision is not only based on knowledge but also involves ideas, skills, values, beliefs, habits, attitudes, wisdom, feelings, self-consciousness and common concepts.

It corresponds to a development process that simultaneously combines ethical reflection and medical practice. Culture gives a specific purpose to the use of technical knowledge by always being specific to a given context. The successful integration and use of an IS must pass by organizational learning perfectly integrated within organizational culture. In effect, this will result in encouraging, rewarding, valuing and using what its members have learnt, both individually and collectively.

Moreover, health facilities still operate by hierarchy. It is therefore essential to convince those at the top (heads of departments, hospital doctors) of the utility of the IS. The adherence of these medical “decision-makers” will have a much greater impact than that of the administration on other users. It is also important to win the trust of the doctors that use the IS on a daily basis by showing them that technical obstacles are reduced. To do this, the organizers must identify their skills, availability and roles; answer their fears, especially in terms of training them to use the IS; and convince them of the usefulness of the IT setup and its potential integration into their daily practices.

From these results, it seems essential to develop mechanisms aiming to institute a collective culture in response to the result and use of the IS. The challenges are, therefore:

- – to establish trusting relationships and reinforce interpersonal relationships;

- – to create a position of coordinator–host essential for maintaining a cohesive and credible system, especially if it is accessibly by many users;

- – to set up mentoring and support systems;

- – to create a clear organizational vision of the way in which organizational learning can contribute to capacity, efficiency and durability of the IS within an organization;

- – to recognize the importance of cultural dimensions of the use of an IS when developing skills, processes, methods, protocols and tools for patient healthcare;

- – to raise staff awareness as to correct ITC use while preserving individual liberty;

- – to make individuals handling sensitive information accountable so that they ensure its security [BAL 06];

- – to create consensus between the different stakeholders of the structure.

Ultimately, the recommendations for this sector can be illustrated as given in Table 3.9.

Table 3.9. Recommendations for the relational and cultural domain

| 20 Actions |