The Interpretation of Dreams

The Western assumption that dreams are softer (more subjective, false, private, transient, and illusory) than the hard facts of waking life (which we think of as objective, true, public, permanent, and real) is an assumption that is not shared by Indian texts devoted to the meaning of dreams. Indian medicine and philosophy do not recognize the distinction between two aspects of dream analysis that is made by Roger Caillois, who speaks of “two types of problems concerning dreams that have always puzzled men’s minds.” The first is the meaning of the images inside the dream; the second is “the degree of reality that one may attribute to the dream,” which depends on our understanding of the relationship between dreaming and waking.1

The two aspects of dreams merge from the very start in India, since one word (svapna, etymologically related to the Greek hypnos) designates both the content of dreaming—i.e., the images in the dream, the actual dream that one “sees”—and the form of dreaming—the process of sleeping (including the process of dreaming), which involves the relationship between the dream and the waking world. The first is what we would regard as the soft or subjective aspect of the dream, visible only to the dreamer; the second we think of as the objective or hard aspect of the dream, visible to other observers. The first is what we examine on the psychoanalyst’s soft couch; the second we analyze with the hardware of the sleep laboratory.

DREAMS IN VEDIC AND MEDICAL TEXTS

The earliest Indian reference to dreams, in the Ṛg Veda (c. 1200 B.C.), describes a nightmare, but it leaves ambiguous the question whether what is feared is merely the experience of the dream (the process of having a bad dream) or the content of the dream (the events in the dream and the implication that it will come true): “If someone I have met or a friend has spoken of danger to me in a dream to frighten me, or if a thief should waylay us, or a wolf—protect us from that.” Are the thief and the wolf part of the dream, too, or part of a contrasting reality? A different sort of ambiguity is posed by the waking dream, which is mentioned in the Ṛg Veda as an evil that one wishes to visit on one’s enemies.2 Yet another Ṛg Vedic verse tells of an incubus who bewitches a sleeping woman in her dream. He shades off into the actual person who rapes the woman, either by transforming himself when she is awake or by manipulating her mind when she is bewitched by the demonic powers of illusion:

The one who by changing into your brother, or your husband, or your lover lies with you, who wishes to kill your offspring—we will drive him away from here. The one who bewitches you with dream or darkness and lies with you—we will drive him away from here.3

These scattered references reveal an assumed link not only between the worlds of dream and magic but between the worlds of dream and reality. They also give us an indication of what the ancient Indians thought people dreamed about: a friend warning of danger, a thief’s attack, a wolf, or being raped by someone who assumes an illusory form. These motifs recur in later Indian dream books and myths about dreams.

By the time of the Upaniṣads (c. 700 B.C.), the question of the reality of dreams was approached in a more systematic way. These texts speak of four states of being: waking, dreaming, dreamless sleep (all natural states), and the supernatural, transcendent fourth state, the identity with Godhead.4 Later Indian texts concentrated much of their attention on the first and fourth levels, waking and Godhead, and on the ways in which waking is a distorted image of Godhead. Dreamless sleep and dreaming are the intermediate steps: dreamless sleep gives us a glimpse of the true brahman, the divine mind that does not create; dreaming sleep gives us a glimpse of the god (Viṣṇnu or Rudra) who creates us by dreaming us into existence.

Other Upaniṣads add certain significant details to the outline of the four states. Waking, one knows what is outside and is common to all men; dreaming, one knows what is inside, and one enjoys what is private.5 The private, internal nature of dreams is emphasized: “When he goes to sleep, these worlds are his. . . . Taking his senses with him, he moves around wherever he wishes inside his own body.”6 The fact that the dream exists only inside the body of the dreamer does not, however, imply that it is unreal, as such a dichotomy (inside vs. outside, private vs. public) might imply in Western thinking. The fourth state, which is called the Self (ātman), is the one in which one knows neither inside nor outside; but the dreamer in the second state, it is often said, knows both of these. The third state, deep, dreamless sleep, may also have the creative qualities that are usually associated with dreaming (the second state): in deep sleep, the sleeper constructs (minoti) this whole world and becomes its doomsday (apīti).7 The dream of a universe created and destroyed is a theme that we will often encounter in Indian texts.

The question of the reality of the dream world is taken up in discussions of dreams as projections. The verb sṛj, used to express projection, means literally to “emit” (as semen, or words), and it frequently occurs in stories about the process of creation (sarga, from sṛj) in which the Creator emits the entire universe from himself the way a spider emits a web:8

A man has two conditions: in this world and in the world beyond. But there is also a twilight juncture: the condition of sleep [or dream, svapna]. In this twilight juncture one sees both of the other conditions, this world and the other world. . . . When someone falls asleep, he takes the stuff of the entire world, and he himself takes it apart, and he himself builds it up, and by his own bright light he dreams. . . . There are no chariots there, no harnessings, no roads; but he emits chariots, harnessings, and roads. There are no joys, happinesses, or delights there; but he emits joys, happinesses, and delights. There are no ponds, lotus pools, or flowing streams there, but he emits ponds, lotus pools, and flowing streams. For he is the Maker [Kartṛ].9

This text has not yet reached the extreme idealism of certain later schools (particularly Mahāyāna Buddhism) that suggest that all perception is the result of projection; rather, in one particular liminal state the dreamer is able to understand the relationship between the two worlds, both of them equally real and unreal. The dreamer takes apart the elements of the outside world and, like a bricoleur, rebuilds them into an inside world of dreams, without affecting their reality status. The text does not pass judgment on the substantiality of the elements out of which the external world is built and the internal world is rebuilt; the same verb is used, here and throughout Indian literature, to denote one’s perception of both worlds: one “sees” (dṛś) the world just as one “sees” a dream. Moreover, the same verb (sṛj) that encompasses the concepts of seminal emission (making people), creation (making worlds), speaking (making words), imagining (making ideas), and dreaming (making images) is also used for the simple physical process by which a turtle “emits” (i.e., stretches forth) its limbs, and this is one reason why God is often visualized as a turtle.

In the Upaniṣadic view, the nature of the content of dreams—the subjective reality of dreams—is closely related to the problem of the status, or objective reality, of dreams. The texts tell us the sorts of things that people dream about: “The dreamer, like a god, makes many forms for himself, sometimes enjoying pleasure with women, sometimes laughing, and even seeing things that terrify him. . . . People seem to be killing him, overpowering him, stripping his clothes from him; he seems to be falling into a hole, to be experiencing unpleasant things, to weep.”10 The pupil to whom this doctrine is expounded (Indra, the king of the gods) comes to realize that, because such violent things could not happen to the transcendent Self, the self that one sees in dreams cannot be truly identical with that transcendent Self or Godhead. The nature of dream experiences—their emotion and instability—is taken here as evidence of the inadequacy of dreams as witnesses of reality. Many later philosophers, including Śankara, continued to argue that dreams are less real than waking experience, though the unreality of dreams was taken as a clue to the fact that waking experience, too, is less real than Godhead.

The four Upaniṣadic stages of being also suggest a technique of realization, a means of approaching enlightenment. For if one understands that one is, in fact, dreaming when one thinks that one is awake, one can begin to move toward the true awakening that is enlightenment—the fourth stage. Thus, it is argued in the Yogavāsiṣṭha, when we take the material universe to be the ultimate reality, we make a mistake comparable to the mistake someone makes when he thinks he sees his head cut off in a dream,11 a traditional image in Indian dream books. The metaphor of the dream is further developed:

When someone dreams while he is awake, as when one sees two moons or a mirage of water, that is called a waking dream. And when someone throws off such a dream, he reasons, “I saw this just for a short time, and so it is not true.” Though one may have great confidence in the object that is experienced when one is asleep, as soon as sleep is over one realizes that it was a dream.12

These texts argue that what we call waking life is truly a kind of dream, from which we will awaken only at death. The minor mistakes that we make in confusing waking, dreaming, and dreamless sleep are a clue to the entirely different nature of Godhead, which is not really in the same series at all.

Many of these Upaniṣadic concepts persist even in present-day Indian medicine as practiced by the Āyurvedic physicians, or vaids:

The vaids maintain that the widely held belief that we are in the waking state (“consciousness”) during the daytime is delusionary. In fact, even while awake, dreaming is the predominant psychic activity. Here they seem to be pre-empting Jung’s important insight that we continually dream but that consciousness while waking makes such a noise that we do not “hear” the dream.13

Indian dream theory not only blurs the line between dreaming and waking but emphasizes the importance of dreaming as a kind of mediator between two relatively rare extremes—waking and dreamless sleep. In fact, the Upanisadic fourth stage, added to the triad, is the whole point of the original analysis; called simply turīya, “the fourth,” it is, in a sense, “the first three all in all,”14 the true state toward which the other three point. And since all four stages are regarded as progressive approaches toward what is most real (Godhead), some Indian philosophers assume that dreaming is more “real” than waking. In dreams one sees both the real (sat) and the unreal (asat),15 and this liminal nature of dreams is the key to the material power they possess in later Indian texts. The content of the dream is explicitly related to the objective world: “If during rites done for a wish one sees a woman in his dreams, he should know that he has seen success in this dream vision.”16 The particular significance of the woman in the dream is also highly relevant to later Indian dream analysts.

The significance of the content of the dream was the subject of the sixty-eighth appendix of the Atharva Veda, composed in the sixth century A.D. This text organized dreams with reference to the objective, waking world—for example, according to the physical temperament of the dreamer (fiery, watery, or windy), the time of night the dream took place, and so forth—but it was primarily concerned with the subjective symbolism of dreams or, rather, with the objective results of subjective contents. This is also apparent from the fact that the chapter on the interpretation of dreams is immediately adjacent to the chapter on the interpretation of omens or portents; that is, the things that happen inside people have the same weight as the things that happen outside them and are to be interpreted within the same symbolic system.

The first chapter of this text describes the dreams that people of particular temperaments will have. The fiery (choleric) man will see in his dreams tawny skies and the earth and trees all dried up, great forest fires and parched clothes, limbs covered with blood and a river of blood, gods burning things up, and comets and lightning that burn the sky. Tortured by heat and longing to be cool, he will plunge into forest ponds and drink. Mocked by women, he will pine away and become exhausted. These are the symbols (lakṣaṇe) by which the dreams of fiery people are to be recognized. The dreamer in this text creates an entire world, with planets and trees and everything else; and it is a world marked by his own inner heat. By contrast, watery (phlegmatic) people construct cool rivers in their dreams—rivers covered with snow—and clear skies and moons and swans; the women in their dreams are washed with fine water and wear fine clothes. Windy (bilious) men see flocks of birds and wild animals wandering about in distress, staggering and running and falling from heights, in lands where the mountains are whipped by the wind; the stars and the planets are dark, and the orbits of the sun and moon are shattered.17

On the simplest level (the level of primary interest to the Indian medical texts), dreams reflect the psychosomatic condition of the dreamer; for example, when a particular bodily sense is disturbed, the dreamer will dream of the objects of that sense.18 But there are other causes of dreams, as well, for it is said that dreams that are not conditioned by one’s temperament are sent from the gods.19 The text does not expand on this laconic remark, but it goes on to describe the effects that will result from dreaming specific dreams—or rather, perhaps, from knowing that one has dreamt specific dreams. For it is clearly stated: If one sees a string of dreams but does not remember them, these dreams will not bear fruit.20 So, too, if a man has an auspicious dream and wakes up at that moment, it will bring him luck.21 This may imply that it is the dreamer’s awareness of the dream that brings about its results. The dream is the beginning of a chain of causes, not the result of such a chain or a mere reflection of an event that was always fated to happen and has simply been revealed to the dreamer through his dream (as other Indian texts imply). These two ideas—that dreams reflect reality and that they bring about reality—remain closely intertwined in Indian texts on the interpretation of dreams. Is it always necessary for the dreamer to be conscious not only of his dream but of its hidden meaning in order for it to come true? This is a question that remains highly problematic for the Indian authors. For one might believe that the dream was sent by the gods, or by one’s own unconscious mind, or by someone else, but the agent who would carry out the events in the dream might not necessarily be the same as the sender of the dream, and this agent might work with or without the knowledge of the dreamer.

Chapter two of the Atharva Veda’s appendix sixty-eight is devoted to the symbolism of dreams. Good luck is said to come to anyone who experiences any of a series of what we would certainly classify as nightmares:

Whoever, in a dream, has his head cut off or sees a bloody chariot will become a general or have a long life or get a lot of money. If his ear is cut off, he will have knowledge; his hand cut off, he will get a son; his arms, wealth; his chest or penis, supreme happiness. . . . If he dreams that his limbs are smeared with poison and blood, he will obtain pleasure; if his body is on fire, he will obtain the earth. . . . If, in a dream, a flat-nosed, dark, naked monk urinates, there will be rain; if one dreams that one gives birth to a female boar or female buffalo or female elephant or female bird, there will be an abundance of food. If someone dreams that his bed, chairs, houses, and cities fall into decay, that foretells prosperity.22

Thus, apparently, even an unpleasant dream is regarded by Indian tradition as a good omen, presaging the fulfillment of a wish. But if these are auspicious dreams, one may ask, what would an ominous nightmare be like? Dreams of bad omen are for the most part as unpleasant as the so-called good dreams. Indeed, it is hard to generalize about the characteristics of good versus bad dreams in Indian theory. A systematic (not necessarily structural) analysis of the lists, along the lines of Mary Douglas’s analysis of Leviticus, might tell us much about India, but probably not much more about dreams. Since “good” and “bad” are not trustworthy labels to stick onto any reality, it is necessary to interpret the dream images in their cultural context. Words like “auspicious” and “inauspicious” (śubha, aśubha) imply things that we do and do not want to have happen to us, but we may be wrong either in wanting or not wanting them. For someone committed to the world of saṃsāra, for example, the death of a son is the worst thing that can happen; for someone seeking mokṣa, the death of a son may be the first move on the path to enlightenment. Thus a dream of the death of a son may be a good dream or a bad dream, depending on the point of view not (as in depth psychology) of the individual dreamer but rather the point of view of the author of the particular textbook on dreams. In the text just cited, the dreamer—a man—gives birth to various female animals, and it is a good dream. For a man to dream of giving birth is not regarded as an unnatural nightmare, in part because many mythological males give birth in India,23 and in part because this text assumes that all dreamers are male and therefore that any dream—even a dream of parturition, in itself a natural and positive image—may retain its positive symbolism when applied to a man. The combination of natural symbols, cultural restrictions, and values of the author of the text determines whether a particular dream will be interpreted as portending good or evil for the dreamer. The authors of the Hindu medical textbooks on dreams are primarily saṃsāra-oriented; the Buddhist and philosophical texts are primarily mokṣa-oriented. To an impressive degree, they agree on what people do dream about, but they often differ about whether the dream portends good or evil. The Epics and Purāṇas draw on both traditions of dream interpretation according to the tastes of the author and the situation of the dreamer in the story.

To return to the Atharva Veda, let us take up the other side of the story and look at part of a list of dreams portending what one does not want to happen:

Whoever dreams that he is smeared with oil, or that he enters his mother or enters a blazing fire, or falls from the peak of a mountain, or plunges into wells of mud or drowns in water, or uproots a tree, or has sexual intercourse with a female ape or in the mouth of a maiden, or vomits blood from his throat, or is bound by ropes—he will die. A dream of singing, dancing, laughing, or celebrating a marriage, with joy and rejoicing, is a sight portending evil pleasure or disaster.24

The dreamer’s awareness of certain bad dreams, culturally defined as portending evil, is expected to produce bad results in his life.

By an extension that has fascinating implications for later Indian theories of dreams and myths about dreams, it is also said that the dreamer can dream the dreams of other people; that is, he can have dreams that symbolize the future events that will happen not to him but to his family, particularly to his son or his wife:

If a man sees [in his dreams] objects cut into pieces—teeth, or an arm, or a head—these will cause the destruction of his brother, father, or son. If a man sees shattered two bolted doors and a bed and a doorpost, his wife will be destroyed. If he sees a lizard or a jackal or a yellow man mount [his wife’s] bed, his wife will be raped. If a man kills a white, yellow, and red serpent in a dream or cuts off the head of a black serpent, his son will be destroyed. If a man dreams that a bald man or a man wearing brown or white or red garments mounts his wife, she will be attacked by diseases. The same will happen if a man dreams that she is mounted by a dog or a serpent or a lizard or a snake or a porcupine or a crocodile or a wild dog or a tiger or a leopard or a serpent with a monstrous hood.25

The sexual symbolism of much of this dream content is quite evident, but this apparently natural or universal or, in Jung’s terms, archetypal symbolism (the serpents and violated bedrooms, the bestiality and physical mutilation) is combined throughout with symbols that have a primarily cultural or specific or manifestational weight: the man in red garments suggests both the ascetic’s ochre robe (anathema to the saṃsāric author of this text) and the robe of the condemned criminal in ancient India, and the particular colors of the sinister serpent also have cultural meanings. Moreover, unlike the Buddhist texts and Hindu Epics and Purāṇas, which, as we shall see, described the dreams of women and also depicted women as skillful interpreters of dreams, the medical texts defined a woman as a person whose own dreams were of no significance. Because of this, the woman’s husband had to dream for her; the woman was never the author or subject of a dream, but she was frequently the object of her husband’s dreams. Indeed, she was often dreamt about by her future husband, a phenomenon that has reverberations in the story literature. The husband may dream this sort of dream about his future wife:

If a man sees a lute marked with a cobra’s tooth, he will get a woman. If he sees birds soaring over lotus ponds, or if he mounts an elephant in rut in his dream, he will take away another man’s wife. If he is bound by iron fetters, he will get a virgin.26

This passage supplies a transition between the one in which the man dreams his own dreams and the one in which he dreams for his wife; here he dreams of his wife.

Many of these symbols recur in Indian stories about dreams. One of them in particular is basic to the myths of dreams, illusion, and rebirth: “A man who dreams that his relatives weep pitifully over him will become satisfied; a man who dreams that he is dead will obtain long life.”27 In keeping with the basic view that dreams about sorrow or pain may portend or bring happiness or pleasure, the dream of death is a dream of life. But in the mokṣic context, the vision of oneself as a corpse, being mourned by others, forms a basic metaphor, as we will see.

Thus Indian dreams may have a material effect not only on the dreamer but on those close to him—his wife, children, parents, and others. This makes more sense in the South Asian context than it does in the West, because in India the self is by no means so clearly limited to the individual as it is for us. That is, the individual feels himself to be a physical as well as mental part of other people, to partake in what McKim Marriott has called the “coded substance” of other members of his family and his caste. He is responsible for the sins of his parents; he can amass good karma and transfer it to others; he must pay for the mistakes committed by his own previous incarnations. And, beyond the social level, he is linked not only to those intimate partners in his life but to all people through the matrix of reality (brahman), which is the substance of which all souls are made. Given these strong invisible bonds, it is not surprising that Indian dreamers can dream for other people or that their dreams can affect the lives of other people.

Later ritual texts added more details to this basic approach to the interpretation of dreams. Men possessed by certain goblins (Vināyakas) will see water in their dreams or people with shaven heads, camels, pigs, donkeys, Untouchables (Caṇḍālas), and so forth. They will also dream that they walk on air, or they will have impure dreams.28 The dream of flying is here linked with the sexual dream, a link that we will encounter again in the myths of dreams. These goblins will also cause a man to think, when he walks on a path, “Someone is following me from behind.”29 The dream of danger is thus tied to the paranoid experience of danger in waking life.

The medieval medical texts greatly elaborate on the symbolism of dreams. As befits a profession devoted primarily to the diagnosis of disease, their emphasis is on violent dreams that presage violent realities. Someone may dream that a black woman wearing red garments, laughing, with disheveled hair, grabs him and ties him up and drags him toward the South; or that ghosts or monks seize and embrace him; or that men who have deformed faces and the feet of dogs smell him all over; or that he is naked but for a red garland on his head; or that a bamboo, lotus, or palm tree grows out of his chest; or that a fish swallows him; or that he enters his own mother; or that he falls from the top of a mountain or into a deep, dark pit; or that he is carried off by a swift stream; or that his head is shaven; or that crows overpower him and tie him up . . . . The list goes on and on, and it is all ominous: the man will be destroyed.30

Some dreams have more specific diagnoses. A man who dreams that his teeth fall out will die. Dreaming of friendship with a dog means that the dreamer will become feverish; with a monkey, consumptive; with a demon, insane; with ghosts, amnesiac.31 Some of these motifs are picked up by the Indian mythology of dreams: the black woman with red garments is the Untouchable woman, the succubus who seduces the dreaming king; the fish that swallows the dreamer is the vehicle of transformation and rebirth. Other motifs, like the man who dreams that he enters his own mother or falls from a great height or falls into a deep pit or has intercourse with animals or feels his teeth fall out, occur in the Atharva Veda and are familiar to us also from our own dreams or from Freud’s summaries of widespread dreams.

But the statement that a man who dreams of intimacy with ghosts will lose his memory makes a different kind of sense, for it implies that a dream of a ghost, a figure from the past, will harm one’s mental control over the past. The relationship between ghosts, memory, and dreams is used to explain certain bad dreams: ghosts (pretas) get into your head when you are asleep. Whenever one dreams that one sees the death of one’s wife, friend, son, father, or husband, it is the fault of the ghost; for these ghosts change their forms into that of an elephant, horse, or bull, and they appear to their sons, wives, and relatives.32 Here, long before Freud, is the hypothesis that animals in dreams represent close relatives; and “ghosts” is not a bad way of describing the figures from the past who haunt our dreams and force us to imagine the deaths of those we both love and hate. The ghosts, whose reality status is somewhat vague, nevertheless mediate between two sets of entirely real people: the dreamer and his dead relative or wife. Ghosts are also implicated in the dreamer’s attempts to avert the effects of bad dreams: “If one has a sinister dream, he should not relate it to anyone, but should pass three nights in the temple to honor the ghosts. He will then be delivered from the bad dream.”33 The remark that not telling the dream is a part of the process of making it unreal is surely significant, and it is reinforced by another passage in the same text: “Just as a dream that reflects one’s true nature may be forgotten and come to naught, even so the things that we see and think in broad daylight may have no effect.”34 The text implies that the dream that is not remembered, and therefore is not told, will not have the effect it might have had were it remembered and told; and in this, the text states, dreams are no different from the mental perceptions of waking life.

The question of the distinction between dreams and waking life leads us back, out of the territory of the symbolism of the content of dreams, to the question of the boundaries between dreams and other mental processes or between various kinds of dreams. We have already encountered the Upaniṣadic fourfold classification (waking, dreaming, dreamless sleep, and the experience of the ultimately real) and the Atharva Veda’s threefold classification (according to the three humors of the body), with its supplementary categories of dreams sent by the gods and dreams caused by the excitation of one sense or another. A Buddhist treatise, The Questions of King Milinda, adds to the threefold categorization by humors three more: dreams influenced by a god, dreams arising out of past experience, and prophetic dreams. The first two of this supplementary triad correspond to the two supplementary categories of the Atharva Veda, and the third corresponds to the bulk of dreams that follow in that text, dreams that are portents.

Similarly, the medical text attributed to Caraka divides dreams into several categories: dreams that reflect what has been seen in waking life (dṛṣṭa), dreams that reflect what has been heard in waking life (śruta), dreams that reflect what has been experienced (anubhūta), dreams that foretell the future (bhāvika), and dreams that reflect the disturbance of a particular bodily humor (doṣaja). The first three categories would seem to reflect observations somewhat akin to our own; these categories, however, must be understood in contrast to other classifications, such as that of the Jains, who divided dreams into those that reflect things that have been seen (dṛṣṭa), dreams that reflect things that have not been seen (adṛṣṭa), and those “inscrutably seen” or “both seen and unseen” (avyakta-dṛṣṭa).35 Indeed, these latter two areas are also covered by Caraka in his two final categories: dreams that dramatize individual fantasies (i.e., things unseen), though perhaps based on memory data (kalpita); and dreams that are wish-fulfillments, gratifying desires that could not be gratified in the waking state (prārthita).36 These seven categories of Caraka thus cover waking experience, somatic impulses, imagination, and the influence of the supernatural.

The category of things “unseen” (adṛṣṭa) takes on a new meaning when it appears in another taxonomy of dreams. In certain philosophical schools, adṛṣṭa is “a euphemism, meaning in effect a condition which the philosopher cannot otherwise explain, but which develops later into a fairly sophisticated theory of the unconscious energies of the self.”37 According to the Vaiśeṣika philosopher Praśastapāda, adṛṣṭa causes one of the three kinds of dreams, the kind in which “we dream of things completely unknown in waking life.” These adṛṣṭa dreams are dreams of omens; good ones come out of dharma (dreams in which the dreamer rides on an elephant or gets an umbrella) and bad ones from adharma (dreams in which the dreamer is rubbed with oil or rides on a camel). This category seems to correspond to Caraka’s bhāvika (future-foretelling) and to the Atharva Veda’ s, category of dreams sent by the gods or to the larger, unspecified category of dreams of portent. The second category of Vaiśeṣika dreams is that of dreams due to the strength of the karmic memory traces (as when we dream of things we have thought about hard when we were awake); this corresponds to Caraka’s categories of things seen and heard and experienced. The final Vaiśeṣika category is the most basic one; this is the category of dreams due to the doṣas or humors of the body; for example, a man may dream of flying when wind predominates in his body.38 It is surprisingly hard-headed of this text to give a purely physiological source for the dream upon which the greatest metaphysical and literary energy has been expended in India: the dream of flying.

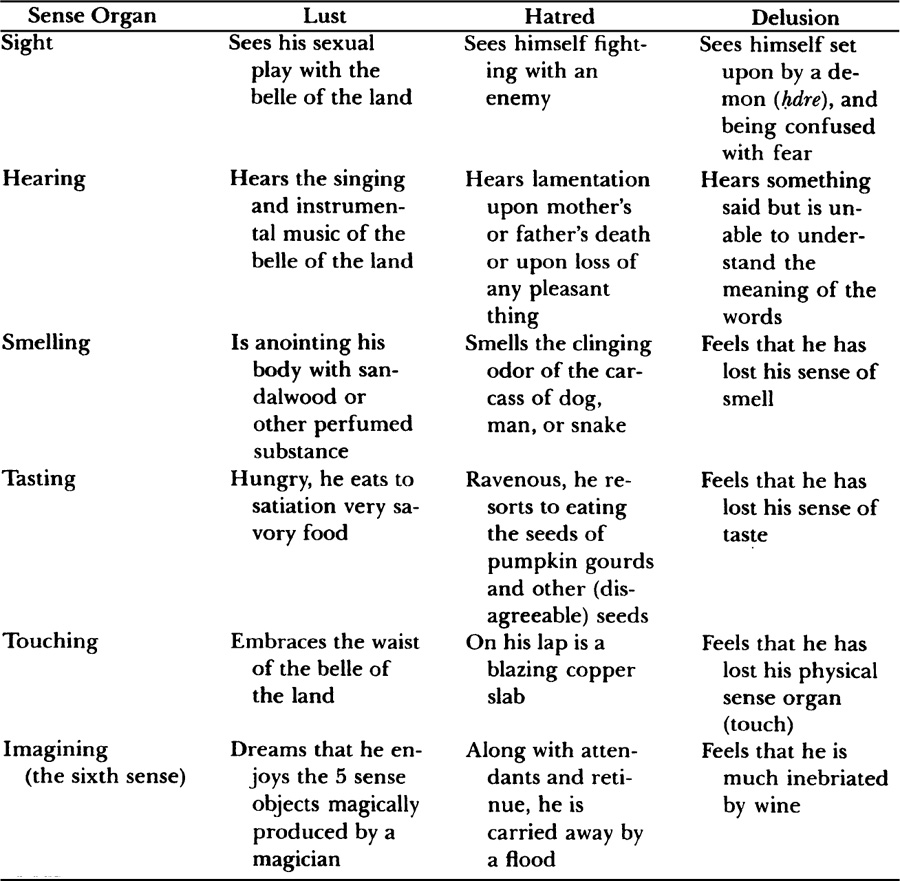

The most elaborate classification of dreams that I know of appears in a Tibetan Mahāyāna text called “The Meeting of the Father and the Son.”39 In this text the threefold classification according to humors is replaced by the threefold classification according to the three “poisons” (also designated by the word for the humors, doṣa): lust, hatred (or anger), and delusion (kāma, krodha, and moha). This triad forms just one axis of the system, however; the other, perhaps based on the Hindu category of dreams arising from the excitation of a particular sense organ, consists of the five sense organs plus the sixth sense, imagination. The resulting grid is shown in figure 1.

The first general point to be made about figure 1 is the evidence it shows of the close attention that Buddhists—particularly Tibetan Buddhists—paid to dreams, an observation that is supported by many Buddhist myths, as we will soon see. Second, we might note the emphasis on emotions as the source of dreams, a factor that we will find essential to our understanding of the Hindu mythology of dreams. It is also significant that imagination and delusion appear as factors in the generation of dreams. Finally, the content of the dreams is strikingly similar to the content of the standard dreams listed in the Hindu sources, though there are different emphases and some new items (such as the loss of the sense of smell or taste or understanding). The familiar items are the vision of sexual pleasure, the vision of a corpse (though here it is the corpse of a parent, not of a child or the self), the eating of good and bad food, a flood that sweeps everything away, the smell of a putrid corpse, and the attack of demons. The important Tibetan category of objects magically created by a magician frequently appears in Hindu myths about dreams, though it is not included in the older Hindu texts on the interpretation of dreams.

Figure 1. A Tibetan Map of Dreams

This chart, which appeared originally in slightly different form in Alex Wayman’s article “Significance of Dreams in India and Tibet” in History of Religions 7 (1967): 5, is reproduced here by permission of History of Religions, © 1967 by The University of Chicago.

The manipulation of the dream itself through magic techniques was also a subject of great interest to Buddhists, particularly in Tibet.40 Tibetan influence spread quickly to Kashmir, where the study of dreams took a new turn in India, leading to a technique by which the dreamer could make the object of his dream materialize when he woke up. This special Tibetan yogic technique was to be employed at the junction of waking and sleeping, the liminal moment of dangerous transition between the two worlds.41 The accomplished yogin is able, at that particular moment, to evoke the desired dream, the dream that becomes real, because he has power not only over the dream but over the objects or people perceived in the dream. The Tantrāloka explains how this comes about: The master and disciple sleep near the sacrificial fire during the initiation; since they have the same consciousness, they have the same dream.42 In this way, the dreamer could actively, purposely, dream a subjective dream that was shared by his teacher and that created an objective, material thing that had not previously existed except in his mind.

Dreams in the Rāmāyaṇa: Sītā and Bharata

The Hindu Epics and Purāṇas incorporated into their narratives many of the traditional dreams analyzed in the philosophical and medical texts. In Vālmīki’s Sanskrit Rāmāyaṇa, when Sītā has been stolen by the demon Rāvaṇa and is being held captive on the island of Lankā, Rāvaṇa gives her this ultimatum: if she refuses to share his bed, he will have her cooked and will eat her for breakfast.43 The story continues:

Sītā lamented, saying that she could not go on living without Rāma. She said that she would never deign to touch Rāvaṇa with her left foot, let alone submit to his lust. “Rāvaṇa will pay for this,” she insisted; “Lankā will soon be destroyed. But since I have been abandoned by Rāma and am in the power of the evil Rāvaṇa, I will kill myself.”

The ogresses threatened Sītā, saying, “Today the demons will eat your flesh,” but one old ogress, named Trijaṭā, said to them, “Eat me, but do not eat Sītā. For last night I saw a terrible dream that made my hair stand on end, foretelling the destruction of the demons and the victory of Sītā’s husband. I saw Rāma coming in a chariot made of ivory, drawn by a hundred horses, and Sītā, wearing white garments, reunited with him. And I saw Rāvaṇa fallen from his chariot, lying on the earth, being dragged about by a woman, and he was wearing dark garments and his head was shaven bald. And then I saw him in a chariot drawn by asses, wearing red garlands and red ointments, driving south into a lake of mud, while a seductive woman dressed in red garments, a dark woman, whose body was smeared with mud, was dragging him southwards to the region of the king of death. And Lankā had fallen into the ocean, and all the demons, wearing red garments, had fallen into a lake of cow dung. So do not revile or threaten Sītā, but console her, or Rāma will never spare you. Such is the dream that I had about Sītā. She will be released from her sufferings and get her beloved husband back again, and then, I think, all the suffering she has undergone will be as insubstantial as a shadow. I see, in her, portents of the victory of Rāma and the defeat of Rāvaṇa: her left eye is twitching and the hair on her left arm is standing on end, for no apparent cause.”

But when Sītā heard the unpleasant speech of Rāvaṇa, she trembled and resolved to kill herself; she took the ribbon from her hair and said, “I will hang myself with this cord and reach the home of the god of death.” Just then, however, she saw many portents: her left eye twitched, her left arm trembled, and her left thigh quivered. These portents enlightened her, for they foretold that she would soon get what she wanted. Her sorrow vanished, her fever was assuaged, and her languor was dispelled.44

Trijaṭā’s dream rings true in at least two ways. First, the symbolism clearly corresponds to the events in the life of Rāvaṇa, who is to be destroyed by a woman (Sītā) for whom he lusts, dragged down into the mud and condemned to death at the hands of the woman’s husband. Second, the symbolism of Trijaṭā’s dream contains traditionally accepted Indian images of evil portents: the red garments, the bald head, the asses dragging the chariot, and so forth. Trijaṭā also correctly glosses the physical signs that appear on Sītā’s body. Yet her dream has no bearing on Sītā’s state of mind, perhaps because Sītā does not know about it (it is not clear from this text whether Sītā is still present when Trijaṭā tells the other demon women about her dream).

When this episode is retold in the Tamil Rāmāyaṇa of Kampaṉ, it is explicitly stated that Trijaṭā does in fact tell her dream to Sītā. Indeed, the ogress tells Sītā why she is revealing the dream to her, and her reason is a most significant one: knowing that Sītā is in despair and is even beginning to worry that Rāma will blame her for all his troubles and will not bother to rescue her, Trijaṭā has pity on Sītā and says to her, “Because you cannot sleep, you have had no dreams. Listen, then, to what I have dreamt, which will certainly come to pass.”45 This statement is built on several assumptions that might not be as obvious to a Western reader as they are to an Indian reader. In the Sanskrit Rāmāyaṇa, in a passage that we are about to look at, Sītā does complain that she cannot sleep and therefore cannot dream. Trijaṭā therefore has the dream for Sītā, just as men often have dreams for their wives (whose dreams would not have been recorded or analyzed) and lovers often dream for each other. Here, in the Tamil Rāmāyaṇa, the ogress dreams on behalf of her prisoner, while in the Sanskrit version the ogress recognizes the external portents on Sītī’s body; since dreams and portents are closely linked, the Tamil simply substitutes for the somatic portents in the Sanskrit text the internal portents of the dream. Trijaṭā in the Tamil text sees into Sītā’s mind as well as into her body. The dream is basically the same in both texts (Rāvaṇa is in a chariot pulled by asses, and so forth), but in the Tamil text it is Sītā’s dream even though it is dreamt by Trijaṭā and then “reported” to Sītā.

In the Sanskrit Rāmāyaṇa, by contrast, Sītā ignores the entire episode and simply responds to the earlier threats of Rāvaṇa. But Sītā does respect the evidence of portents that she experiences in her own body: she is convinced by the trembling of her eye and arm and thigh, the very signs that Trijaṭā had seen. To this extent, Sītā and Trijaṭā may be said to have shared the dream of the good omens, though they did not know that they shared it. This is a situation that we will examine more precisely in chapter two.

It would appear that Sītā is a practical lady who believes in traditional omens when she can feel them herself. Her hard-headedness continues to prevail in the following encounter. Rāma has sent the monkey Hanuman to Sītā; but when Sītā sees Hanuman, she is thrown into an agony of confusion:

“Today I have seen a grotesque dream, the dream of a monkey, that is condemned by the textbooks [on the interpretation of dreams]. I hope nothing bad has happened to Rāma or his brother Lakṣmaṇa or my father the king. But this cannot be a dream, for I am so tortured by sorrow and misery that I cannot sleep. . . . I have been thinking constantly of nothing but Rāma all day today, obsessed by the mental image of him alone, and that is why I have seen and heard these things. This is just wishful thinking—but, nevertheless, I wonder about it, for this monkey speaks to me and has a clearly visible form. I hope the news that he has brought to me will turn out to be true, and not false.”46

When Hanuman continues to approach her, Sītā speaks to him to test his reality. She compares this incident with her previous encounter with a false and destructive illusion: her abduction to Lankā took place when the demon Rāvaṇa took the magical form of a wandering monk, fooling Sītā and luring her away from safety. With this in mind, Sītā is suspicious of Hanuman, and she says to him,

“What if you are a form of Rāvaṇa himself, the master of illusion, once more engaging in magic illusion to make me suffer? It was Rāvaṇa who concealed his true form and took the form of a wandering monk when I saw him in the forest. But if you are truly a messenger from Rāma, welcome to you, best of monkeys; and I will ask you to tell me about Rāma. I have been held captive for so long that I find great happiness in a dream. If I saw Rāma and Lakṣmaṇa even in a dream, I would not despair; even a dream can be exhilarating. But I don’t think this can be a dream, for if you see a monkey in a dream it is an omen of nothing good, but something good has happened to me. This could be a delusion in my mind, or some disturbance caused by indigestion, or madness, or a mental distortion, or a mirage. But it is not madness or delusion, for I am in my right mind, and I see both myself and this monkey.”47

As she wavers in this way, Sītā is inclined to believe that Hanuman must be a demon after all, but then he describes Rāma in great physical and psychological detail and narrates all the events of the Rāmāyaṇa up to that point. Sītā now rejoices and realizes that Hanuman is in fact “truly a monkey” and that it is “not otherwise.”48

In her semihysteria, Sītā has ricocheted back and forth between doubt and blind faith. Her cynicism made her think that she was being duped once again by a demon or that she was simply losing her mind and projecting her wishes onto the empty air. Yet she was confident that she had not lost her mind, and she rationalized this inner conviction by a sophisticated argument based on scholarly tradition (a very orthodox thing to do, as we shall see in chapter four): she accepted the traditional dream-book judgment that a dream of monkeys results in unhappiness (she had already remarked that the dream of a monkey was condemned by the texts of the dream books); then, since she was in fact happy, she argued that she could not have dreamt of a monkey. Moreover, this appeal to learned authority is now supported by yet another “text”: the story of Rāma, the very Rāmāyaṇa in which she herself is appearing as a character. By listening to her own story, she convinces herself not only that she is real but that Hanuman, the narrator of her story, is real. This spilling-over of the story into the frame of the narrative is a technique that is basic to the Vālmīki Rāmāyaṇa. For example, Vālmīki himself appears as a character in the story, as a sage who raises the two sons of Rāma and Sītā and teaches them the Rāmāyaṇa, and, when the boys recite this story to Rāma, he recognizes them as his true sons,49 even as Sītā recognizes Hanuman as a “true monkey” when he tells her the story.

The Rāmāyaṇa also recounts the dream seen by Bharata, Rāma’s brother, during the night preceding the day on which messengers will arrive to tell him to usurp the throne that would rightfully descend to Rāma, the elder son:

On the very night before the messengers arrived in the city, Bharata saw a most unpleasant dream, and at dawn he was deeply upset. He said to his friends, “In a dream I saw my father dirty and with disheveled hair, falling from the peak of a mountain into a lake of cow dung. I saw him swimming in that lake of cow dung, and drinking oil from his cupped hand, and laughing over and over. Head downward, he kept eating rice with sesamum, and his whole body was smeared with oil, and he plunged down right into the oil. And in my dream I saw the ocean dried up, and the moon falling to the earth; I saw the earth split open, and all the trees dried up, and the mountains shattered and smoking. And I saw my father the king dressed in black garments and seated on a throne made of black iron, while lascivious women, dressed in black and yellow, laughed at him. And his body was adorned with red garlands and smeared with red ointments as he was heading south in a chariot drawn by donkeys. This is what I saw during that terrifying night. Either Rāma or Lakṣmaṇa or the king or I will die. For whenever a man dreams that someone travels in a chariot drawn by a donkey, soon the smoke will be arising from his funeral pyre. That is why I am so sad. My throat is dry, and I cannot steady my mind. I some-how despise myself, though I do not see any cause for this. But when I recall that evil dream, which contains many images and cannot be puzzled out, a great fear grasps my heart and will not let go; for I keep thinking about the king, who appeared to me in an unthinkable form.”50

Some of the images in this dream arise directly out of the story that is being told: the king is indeed about to “fall” and to die (to head south, to the land of the dead), and he is being mocked by a lustful woman (the queen, who has made him crown Bharata in place of Rāma). Other images are validated by the traditional dream books, as Bharata himself recognizes. In particular, the images point to fiery or choleric people (as they are characterized by the Atharva Veda), a personality type appropriate to a king. Moreover, as in the Atharva Veda, Bharata dreams not only for himself but for others—his father and his brother; for his brother is about to be exiled, and his father is about to die. Bharata thinks that he does not understand his dream or understand the form in which he saw his father, but he does glimpse the meaning of it; for he despises himself, and this is not, as he claims, for no apparent cause, for he is about to consent, albeit unwillingly, to his brother’s exile, and this will break his father’s heart.

Dreams in the Mahābhārata: Karṇa and Kārtavīrya

The other great Sanskrit epic, the Mahābhārata, presents a set of contrasting dreams on the eve of a great battle: nightmares in those who are about to be defeated, auspicious dreams in those who are about to conquer. These dreams are then paired with good and bad omens observed in the two camps, for the Mahābhārata, like the dream books and the Rāmāyaṇa (in which Trijaṭā’s dream is linked with Sītā’s omens), treats the two phenomena together. Karṇa tells Kṛṣṇa why he believes the Pāṇḍavas (Kṛṣṇa’s faction) will win the battle and the Kurus (on whose side Karṇa is fighting) will lose:

Many horrible dreams are being seen by the Kurus, and many terrible signs and gruesome omens, predicting victory for the Pāṇḍavas. Meteors are falling from the sky, and there are hurricanes and earthquakes. The elephants are trumpeting, and horses are shedding tears and refusing food and water. Horses, elephants, and men are eating little, yet they are shitting prodigiously; wise men say that that is a sign of defeat. They say that, by contrast, the mounts of the Pāṇḍavas are quite happy and that wild animals are circling their camp to the right, a good sign, while all the wild animals are circling the Kurus’ camp to the left. Peacocks, wild geese, and cranes follow the Pāṇḍavas, while vultures, crows, kites, vampires, jackals, and swarms of mosquitoes follow the Kurus. For them, too, the god has sent a rain of flesh and blood, and a magic city in the sky hovers nearby, shining in its walls, moats, ramparts, and gates.

And I had a dream in which I saw the Pāṇḍavas climb to a palace with a thousand pillars. All of them wore white turbans and white robes. And in my dream I saw you, Kṛṣṇa, drape entrails around the earth, which was awash with blood, and I saw the Pāṇḍava Yudhiṣṭhira climb a pile of bones and joyously eat rice and butter from a golden bowl. And I saw him swallow the earth that you had given to him; clearly he will take over the earth. The Pāṇḍavas were mounted on men, and they were wearing white robes and turbans and carrying white umbrellas, while we Kurus were wearing red turbans and were riding in a cart drawn by a camel, traveling to the South.51

This passage, which I have greatly condensed, adds to the traditional list of portents a few original ones, but it tells a fairly straightforward dream, the meaning of which is clear to the dreamer. Animals loom large in both the omens and the dreams, as do directions (left and South being inauspicious) and colors (red being inauspicious, white auspicious). The inauspiciousness of the magic city in the sky, which we will encounter again in chapter six, adds delusions to omens and dreams as a third category of portents.

The medieval Hindu Purāṇas, with their baroque style and insatiable appetite for detail, outdo both the philosophical and medical texts in the lurid features of their dream analyses. The traditional lists of good and bad omens and dreams are built into stories that then go on to demonstrate the consequences of these dreams in the lives of the dreamers. One myth of this type takes the traditional episode that we have just seen in the Mahābhārata—the description of good dreams and omens for one side on the eve of battle, bad dreams and omens on the other—-and breaks it into two separate scenes. First we are told of the dreams of the hero, Paraśurāma, to whom the gods have sent happy dreams of good omen, which include the following visions:

At the end of the night, Paraśurāma saw sweet dreams that he had not thought of with his mind. He saw himself mounted on an elephant, a horse, a mountain, a balcony, a bull, and a flowering tree; he saw himself weeping and being eaten by worms; his whole body was smeared with urine and shit and covered with lard and pus; he was playing the lute; . . . he saw himself eating many kinds of delicious food; he saw himself terrified, being eaten by a leech, a scorpion, a fish, and a snake and running away from them. Then he saw that he had entered the orbit of the sun and moon; he was looking at a woman who had a husband and a son. . . . Adorned with jewels and clad in celestial garments, in his dream he lay with a forbidden woman [agamyāgamanam]. He watched a dancing girl and a whore, and he drank blood and wine; and in his dream his whole body was covered with blood. He ate the flesh of yellow birds and men. Suddenly he was bound with chains, and his body was wounded with a knife. When he had seen this, he woke at dawn, thrilled with joy because of the dream, for he knew that he would surely conquer his enemy.52

One would hardly call this a sweet dream, even if one took into consideration the many pleasant images that I have omitted from my condensed selection. But it is a good dream in the sense that many of its images, however violently painful as natural symbols, are sanctioned by Indian tradition as formal or cultural indications of good luck. Moreover, Paraśurāma knows that the dream did not come from his own mind; from this we may infer that it was an unseen (adṛṣṭa) dream, sent to him from the gods. Thus, even an unpleasant dream is regarded by this tradition, as it was by Freud, as a kind of wish-fulfillment; but where Freud regarded the dream itself as the fulfillment, Indian dream theory regarded the dream as the omen of an event that would fulfill the wish.

But if Paraśurāma’s dream was a good dream—the dream of the victorious hero—what, one wonders, were the villain’s nightmares like? The text tells us:

King Kārtavīrya told his wife that morning, “My dear, listen to the dream I had. The earth was covered with ashes and red China roses; there was no moon or sun in the sky, and the sky was sunset red. I was riding on a donkey, wearing red garments and iron ornaments, playing and laughing in a pile of cremated ashes. I saw a widow whose nose had been cut off; she was dancing and laughing coarsely; her hair was all disheveled, and she wore red garments. Then I saw a funeral pyre with a corpse on it but no fire, just a lot of ashes; and there was a rain of ashes, and a rain of blood, and a rain of fire. . . . I thought, ‘A pot full of water has fallen from my hand and shattered,’ and then I saw that the moon had fallen from the sky, and I saw that the sun had fallen from the sky to the earth. And then I saw a terrifying naked man with a hideous body and a gaping mouth coming toward me. A twelve-year-old girl, wearing fine clothes and jewels, was going out of my house in a fury, and you were saying, ‘My king, give me permission to leave; I am going from your house to the forest.’ This is what I saw in the night. And an angry Brahmin cursed me, and so did an ascetic, and also my guru. And I saw painted dolls dancing on the wall. And I saw dancers and singers at a joyous marriage. . . . A naked widow with disheveled hair, dark-skinned and wearing dark clothes, was embracing me. A barber was shaving my head and beard and cutting my nails. Dried-up trees and headless ghosts were whirling about in the wind, and garlands of skulls, terrible to see, were whirling about in the wind. Ghosts with disheveled hair, vomiting fire, kept terrifying me. And I saw a naked man wandering on the earth with his head down and his feet up.”53

This dream seems more genuinely dreamlike than the dream of Paraśurāma, though not necessarily more sinister. The traditionally bad features (the widow, the upside-down man, and the cremation ground) are followed by strangely surreal sequences: a pot breaks in Kārtavīrya’s hand and becomes the moon in the sky; a young girl rushes from his house in distress, and his wife leaves in dignified sorrow. Unlike Paraśurāma, Kārtavīrya makes no judgment about the portent of his dream, but his wife reacts immediately:

When the queen heard what the king had said, her heart burned in anguish, and she wept and stammered as she said, “Don’t fight Paraśurāma. You think you are a hero because you conquered the evil Rāvaṇa. But he was conquered by his own evil, not by you. Good men [santas] know that the material world [saṃsāra] is like a dream.” She tried in vain to dissuade him from entering the battle, but he argued that one could not overcome time, destiny, and the will of the gods. “I know for certain,” he concluded, “that he is going to kill me, for I know the whole future.”

The queen then committed suicide in the arms of her husband. He performed her funeral rites, consigned her body to the fire, and went to the battlefield. On the way he saw many omens: a weeping naked woman with her nose cut off and disheveled hair; a widow in dark clothing; a bawd, diseased and unchaste in mouth and womb; and a man-chasing witch who had no husband or son. Then he saw a funeral pyre, a burnt corpse, ashes . . . a broken jar . . . a blind man, a deaf man, an Untouchable [a Pulkasa], a man whose penis had been cut off, a man drunk on wine, a man vomiting blood, a buffalo, a donkey, urine, shit, phlegm. . . . Though the king was disturbed at these sights, he went forth to battle, where Paraśurāma killed him.54

Not only do the sights that the doomed Kārtavīrya sees resemble his own dream (corroborating and supporting the omens in that dream); they also supply the mirror image of Paraśurāma’s “good” dream: where Paraśurāma saw a woman with a husband and son, Kārtavīrya sees a widow and a woman who has no husband or son. Thus this text comes to terms with both of the classical dream problems at once: it interprets the dream, and it establishes a definite positive link between dreams and reality.

Buddhist Dreams: Kunāla and the Wicked Queen

The Buddhists, as we have seen, devoted much attention to the interpretation of dreams; they were also concerned with the problem of the relationship between waking and dreaming. The question of the reality or nonreality of dreams was treated at length both by the Sarvāstivādins (Buddhist realists, whose name reflects their doctrine that “Everything exists”) and by the traditional Theravādins. A Buddhist tale of dreams is clearly in the same Indian tradition as many of the Hindu tales of dreams:

The Emperor Aśoka had a handsome son with beautiful eyes; he called the boy Kunāla. One day a Buddhist monk predicted that Kunāla’s eyes would soon be destroyed, and from that time forth the boy devoted himself to Buddhist teachings. Tiṣyarakṣitā, Aśoka’s chief queen, fell in love with Kunāla, but he rejected her and called her “Mother.” Aśoka sent Kunāla to Takṣaśilā on an embassy; on the way, a Brahmin fortuneteller foretold that the prince would lose his eyes.

It happened that Aśoka became very ill. Tiṣyarakṣitā commanded the doctors to send her a man suffering from the same disease; she had him killed, slit open his belly, and examined the stomach. She found a worm there, to which she fed various substances until she discovered that it died when she fed it onions. She then fed onions to Aśoka, who recovered from his illness. In gratitude, he granted her her wish that she would rule as king for seven days. During this period she composed a letter, in Aśoka’s name, telling the people of Takṣaśilā to put out Kunāla’s eyes.

Now, when Aśoka wanted something to be accomplished quickly, he always sealed the orders with his teeth. Therefore, that night, Tiṣyarakṣitā went to Aśoka, thinking that she would get him to bite the seal on the letter with his teeth. But something startled the king, and he woke up and reported that he had had a nightmare: “I saw two vultures trying to pluck out Kunāla’s eyes.” A second time she tried, and this time he dreamed that Kunāla was entering the city with a beard and long hair and long nails. The third time, Tiṣyarakṣitā managed to get the letter sealed with Aśoka’s teeth, and he did not awaken, but he dreamed that his teeth were falling out. In the morning, the queen sent the letter to Takṣaśilā, and Aśoka asked his soothsayers to interpret his dreams. They said that anyone who dreamed such dreams would see the destruction of his son’s eyes, and the death of his son.

The people of Takṣaśilā obeyed the commands in the letter, though they did not want to, and had Kunāla’s eyes put out. Kunāla returned to Aśoka’s palace but was not recognized by the guards. He began to sing a song, telling how his eyes had been ripped out and how he had then attained a vision of the truth. Aśoka recognized the sound of the voice and the song as Kunāla’s, but his servants said it was just a blind beggar. Then Aśoka said, “In a dream, long ago, I saw certain signs; there can be no doubt now, Kunāla’s eyes have been destroyed.” Aśoka sent for him and at first did not recognize him; but when the boy said, “I am Kunāla,” Aśoka fainted. Revived by water splashed in his face, he embraced his son and wept. When he learned that Tiṣyarakṣitā had had Kunāla blinded, Aśoka raged with anger and said, “I’ll tear out her eyes, and then I think I’ll rip open her body with sharp rakes, impale her alive on a spit, cut off her nose with a saw, work on her tongue with a razor, and fill her with poison and beat her.” Though Kunāla begged Aśoka to forgive the queen, he threw her into a lacquer house, where she was burnt to death.55

Hard and soft attitudes to the dream, and to reality in general, are combined in this tale. The hard attitude may be seen in the queen’s highly empirical and scientific approach to her husband’s illness (which she cures not out of love but rather out of fear that, if Aśoka dies, Kunāla will become king and will have her killed) and in the text’s implication that the king’s dreams were the direct result of physiological stimulus: he dreamed that his teeth were falling out because the queen had touched his teeth while he slept. Superimposed on this materialistic model, however, is a far softer approach: the dream of teeth falling out symbolizes impending death or mutilation. In this case, the loss of teeth is explicitly equated with blinding, the punishment inflicted on the stepson who rejects his stepmother’s advances (even as Oedipus was blinded for succumbing to his mother). The soft approach to the dream may also be seen in the value set on the dream as a predictive device; in its equation with other, nondream, predictions (by Buddhist monks and Hindu soothsayers); and in the fact that it is Aśoka’s belief in his dream that allows him to recognize his son, despite the son’s violently altered physical appearance. The truth of the dream is set against the falseness of waking life on several levels. On the level of the plot, it is set against the false queen (who says, “Long live Kunāla” when the king tells her his first two nightmares). On the philosophical level, the metaphor of the dream is absorbed into the larger metaphor of the seeing eye that is blind to the illusion of the world; Kunāla is grateful to the queen, he says, for by having him blinded she has enabled him to obtain true sight.

The actual glossing of Aśoka’s dream by the soothsayers is an essential part of his enlightenment, though he is not completely convinced until the dream comes true; for him, a hard proof is necessary before he believes. In this he is dramatically contrasted with his son, who believes the first prediction by the Buddhist monk; this contrast is maintained even at the end of the story, where the compassionate Kunāla forgives and blesses the queen, while the passionate Aśoka takes a sadistic revenge upon her.

The interpretation of dreams to enlighten a king is a recurrent Buddhist motif. In a Kashmiri text that contains many dream adventures, a Buddhist monk interprets a king’s dream in order to convert him.56 Doubtless, these stories reflect actual Buddhist practice, for other sources corroborate the tradition that Buddhists converted many Indian kings by a combination of public debate, private counseling, medical ministrations (at which the Buddhists surpassed the Hindus, who were restricted by considerations of caste and pollution), and a kind of primitive psychoanalysis: “Always by means of this subtle sleep that owes nothing to experience, the king discovers, little by little, all the faults that stayed hidden at the bottom of his unconscious.”57

Dreams are closely integrated into the hagiography of the Buddha. Gautama himself had several highly significant dreams before his enlightenment, and these were corroborated by the dreams of his father and his wife on the night before his departure from the palace.58 The wife of the great Buddhist king, Vessantara, had a dream that her husband interpreted for her just as Tiṣyarakṣitā interpreted the dreams of King Aśoka.59 We will examine these Buddhist stories more closely in chapter four. But it would be wrong to suppose that the “psychoanalytic aspect of the dream” was more particularly Buddhist than Hindu,60 for it is evident from the sources that we have barely skimmed that such stories are part of the nondenominational, pan-Indian science of the interpretation of dreams.

Our Western attitude to dreams is largely derived from traditions inherited from the Greeks (especially Plato) and from the psychoanalysts (especially Freud). Let us turn to them now, in part to use them as a touchstone against which we may understand the contrasting Indian view, in part to make us aware of the way our assumptions color our reception of the Indian texts, and in part to come to a better general understanding of the meaning of dreams by recalling what a few of our own greatest thinkers have understood about them.

A striking instance of the ambiguity in the Greek attitude to dreams appears in Pindar’s tale of the taming of the winged horse Pegasus by Bellerophon:

[Bellerophon] suffered greatly beside the stream in his longing to yoke Pegasus, the son of the snake-girded Gorgon, until the maiden Pallas brought him a bridle with a golden band. Suddenly the dream became a waking experience [hupar]. She said, “Are you sleeping, king, son of Aeolus? Come, take this charm for the horse, and sacrifice a white bull to the Father, the Tamer [Poseidon].” This is what the maiden with the black shield seemed to say to him as he slept in the darkness. He leapt to his feet and seized the marvel [teras] that lay beside him, and joyfully he went to find the seer of that land, the son of Coiranus. He showed him all that had happened, how he had lain down at night on the altar of the Goddess, as the seer had bid him do, and how she herself, the daughter of Zeus who hurls the thunderbolt, had given him the golden thing to tame the mind [of the horse]. And the seer ordered him to obey the dream as quickly as he could.61

Pindar’s tale begins with the formulaic dream: Bellerophon sleeps at the altar precisely in order to dream, and Athena addresses him with the words that identify her as a creature in his dream: she chides him for sleeping and wakes him up, as various figures in Homer chide and wake the dreamers to whom they appear. Yet, right before Athena speaks these words that identify her as a dream, Pindar tells us that she is not a dream; and he uses the traditional formula from Homer to express this, too: the dream is not a dream (onar) but a waking experience (hupar). This phrase is used in Homer sometimes within a dream and sometimes after a dream. In either case, it functions as a commentary, redefining what we thought was a dream and telling us that it was not, in fact, a dream. But Pindar tells us that Athena brought Bellerophon a bridle in a dream and that then the dream became a nondream; she spoke to him (in a dream, as her words indicate) and gave him not a dream bridle but a real, “waking,” bridle. And when he woke up, though he regarded the bridle as a marvel (since it was the materialization of a dream image), he held it in his hand and used it. It is significant, I think, that the power of this dream bridle—like the power of all bridles—is not primarily physical but mental; the bridle tames not the body of the horse but the mind of the horse. Athena gives Bellerophon the mental power to tame the horse, and so she gives him a magic bridle. The bridle is all the more appropriate for taming Pegasus because Pegasus himself is a dream figure; he is the winged horse who carries the hero into his dream in many myths of this genre, the magic creature who allows the hero to fly to the woman in the dream world. In the myth of Bellerophon, by contrast, the dream horse comes into the hero’s real life and enables him to fly into battle with nightmare women—the Amazons and the fire-breathing Chimaera, whom Pindar goes on to tell us about in the next lines of the ode. The distinction between dreaming and waking is still there—Pindar uses it as the pivot of the entire episode—but the traditional elements of the dream adventure are redistributed in new ways along the continuum.

Bellerophon’s dream embodies a paradox that troubled the minds of Greek philosophers and inspired a more systematic investigation. Greek “common sense” is well expressed by Heraclitus’ famous dictum: “For the waking there is one and the same [literally: common] cosmos, but of the sleeping, each turns away to his own [cosmos, when dreaming].”62 Indian common sense also asserted that, while dreaming was private, the waking state was “common to all men” (vaiśvānara).63 But in India, as we shall see, there is more than one kind of common sense. The Greeks, too, speak with many voices. Plato provided several challenges to Heraclitus, and it is wise to treat them severally.

In the Theaetetus, Plato challenges the idea that there is no permanent reality apart from our mental constructions of it. When Theaetetus agrees that people who are crazy or dreaming are wrong when they think they are gods or when they imagine, in their sleep, that they have wings and are flying, Socrates asks, “What proof could you give if anyone should ask us now, at the present moment, whether we are asleep and our thoughts are a dream, or whether we are awake and talking with each other in a waking condition?”64 Theaetetus then admits that the very conversation they are having could just be something that they were imagining in their sleep, just as people can imagine, in a dream, that they are telling their dreams. “So you see,” concludes Socrates, “it is even open to dispute whether we are awake or in a dream.” Thus we can never prove that we are not dreaming. The wise man, however, will never assume that he is truly awake.

When we turn to the Republic, we find several different approaches to dreams. First, Plato implies (contra Heraclitus) that everyone in the world is actually asleep, with the exception of a few philosophers, who are awake. The man who does not believe that there is such a thing as absolute beauty is dreaming even when he is physically awake, since he believes that something that is merely a likeness of something else is actually the thing itself; the man who does not make such a mistake is awake.65 So, too, the people who have gone out of and then back into the cave (the mouth of God, in the Indian metaphor) will “rule in a state of waking [hupar], not in a dream, as most cities are now ruled, by men who fight shadows.”66 Finally, Plato points out that the beginning of true wakefulness comes only when we realize that we are in fact dreaming; the Heraclitean opposition between actual public waking and illusory private dreaming has thus been replaced by an opposition between illusory public dreaming and actual private awareness of dreaming. A person who is still trapped in the first category, unable to distinguish the idea of the good, is “taken in by dreams and slumbering out his present life; before waking up here, he goes to Hades and finally falls asleep there.”67 The alternative to this state is not the state of being fully awake, which Socrates does not claim for himself, but merely the state of not being “taken in by dreams”—of being aware that, like everyone else, one is dreaming.

One of the qualities of dreaming that made Plato mistrust it was its association, in his opinion, with the lower animal instincts and emotions. (This attitude was by no means shared by all Greeks, but it was Plato who set the fashion, and so it is with him that we must come to terms.) The belief that dreams arise out of powerful and dangerous emotions is, as we will see in chapter five, characteristic of the Indian viewpoint (as it is of Freud’s). The locus classicus for this argument is the beginning of Book IX of the Republic:

There are superfluous desires . . . that are awakened during sleep, when the rest of the soul, the rational and gentle and dominant part, is asleep; but the part that is like a wild beast and untamed, full of food and wine, leaps up and throws off sleep and tries to get out and satisfy itself. Then he will dare to do anything at all, since he is set free from all shame and reason. He will not shrink from copulating with his mother (as he imagines that he does), or with any other human or god or wild beast, and he will not hesitate to commit a polluting murder, and there is nothing he will not eat.68

The crimes that the sleeping soul commits—or, rather, thinks that it commits (Plato is explicit on this point)—include incest, union with a god, bestiality, murder, and the eating of forbidden food (which, in the Greek context, may well indicate cannibalism). (In Indian myths about dreams, all of these sins, but cannibalism in particular, are committed by the dreamer. We will see this in the tale of Triśanku in chapter three and in the myths of Lavaṇa and Gādhi in chapter four.) Plato then goes on to argue that when a man is drunk, or crazy, or in the thrall of erotic passion, he becomes like a tyrant; sleep releases the lawless desires that dwell in all of us, even those who seem to be most moderate.

[The tyrant], being under the tyrannical sway of lust, becomes, always and waking, what he has been rarely and in dreams, and he will hold back from no terrible murder nor from any kind of food or deed. But the lust that holds tyrannical rule within him, and lives in all anarchy and lawlessness, being itself his monarch, will lead him who possesses it, like a polity, into every sort of outrage.69

It is not really necessary for us to know whether we are dreaming or waking, since the god will not deceive us with illusions either in waking or in dreaming.70 This last point is in notable contrast with the predominant Indian attitude, but, in almost everything else in the Republic, Plato is thinking along lines remarkably parallel to those that were being developed in India at this time. The congruence between the two philosophies emerges even more clearly when we look at the myth that Plato used (found or invented) to illustrate his doctrine—to express what, as he himself admitted, was impossible to express in argument.71

The great Platonic myth of dreaming and dying is the story of Er:

Once upon a time, the warrior Er was killed in battle; but after twelve days, when they laid his corpse on the pyre, he came back to life and told what he had seen there [in the other world]. He said that his soul went out of his body and journeyed, with many others, to a place where they were judged, and they cast lots and chose the next life that they would have, as animals or humans, out of the great variety of lives represented in the lots. Yet the choice was both laughable and amazing, since most people chose according to the habits of their former life. The soul that had been Orpheus chose to be a swan, because he so hated the race of women—at whose hands he had met his death—that he did not want to be conceived and born of them. And Er saw a swan changing into the life he chose as a man. When all the souls had chosen their lots, they went to the Plain of Oblivion and drank from the River of Forgetfulness, and then they all fell asleep. In the middle of the night, they were suddenly carried to their births. Er himself did not drink the water. He did not know how he returned to his body, but suddenly he opened his eyes at dawn and saw himself lying on the pyre.72

The memory of former births forces the souls to go on perpetuating their flawed lives; yet that memory is erased before the new life can begin. Er’s unique achievement is in witnessing the process of rebirth without drinking of the River of Forgetfulness; he is the one traveler who returns from the undiscovered country of death. The problem of memory in rebirth is, as we shall see in chapter five, central to the Indian myths of transmigration; and the swan, who appears at the very start of the list of reborn souls, is an Indian symbol of both memory and transmigration.73 In Plato’s version of this myth, Er is always on the outside looking in. He does not experience the rebirths, as the characters in the Indian stories do, but merely sees them and tells about them. Where the Indian hero becomes all the different lives, Er just sees them scattered about, to be experienced by a number of different people.74 The whole long passage is set, rather awkwardly, in indirect discourse; each scene is what Plato says that Socrates says that Er says that people said to him in the other world. This nesting of levels of discourse is also, as we shall see, an Indian trick; yet here it serves to remind us constantly that all of this is happening only in Er’s mind. The text does not explicitly say that Er is dreaming, but at the end he opens his eyes at dawn. Moreover, all the other people inside Er’s dream fall asleep when they drink the waters of forgetfulness and are reborn; Er, by contrast, does not drink the waters, and he wakes up. He is the man who is not “taken in” by the dream—not even when he is inside the dream. He is, therefore, he man who wakes up and the man who does not die—who actually comes back to life after dying. For in Greece, as in India, Death and Sleep are brothers.

Freud on the Reality of Dreams

The relationship between the realities of dreaming and waking was a problem that troubled the man who wrote the dream book for our era, Sigmund Freud:

Dreams, as everyone knows, may be confused, unintelligible, or positively nonsensical; what they say may contradict all that we know of reality; and we behave in them like insane people, since, so long as we are dreaming, we attribute objective reality to the contents of the dream.75

Yet Freud did try to establish what he regarded as scientific ways in which dreams might be distinguished from reality. Clues to the distinction were provided by the dream work of distortion, condensation, and so forth, and by the nonlogical ways in which dreams ignore rules of time and space. Freud also argued that, even while people dream, they are (pace Theaetetus) always aware of the fact that they are dreaming. Not only are they aware of the existence of outside reality, but their primary purpose in dreaming is in fact to keep that reality at a distance. “I am driven to conclude that throughout our whole sleeping state we know just as certainly that we are dreaming as we know that we are sleeping,”76 Freud remarked, and he used this hypothesis to explain the recurrent dream motif in which the dreamer, within the dream, tells himself that he is dreaming: