Epistemology in Narrative: Tales from the Yogavāsiṣṭha

In my approach to the Indian myths about illusion and dreams thus far, I have made a formal attempt to separate the texts from the arguments, the stories from the commentaries. This is in part a concession to a Western audience that is accustomed to viewing stories and arguments as two different genres; but it could also be argued, on one level at least, that in India, too, they are significantly different genres. Philosophy is not narrative; philosophy thinks out ideas in formal order, using arguments to indicate a proof. Narratives do not constitute proofs; they act out proofs. Narratives, such as myths, constitute a genre that views the same problems that are elsewhere treated philosophically, but views them through a story.

Myths do not prove anything; they merely tell you what is for them a truth, and you either accept it or you don’t; it either matches an experience of your own, or it doesn’t. The sequence of events is by its very nature compelling, and its philosophy is implicit. Narrative says: “This happened once.” This is a basic form of human communication, because it makes an immediate contact, gathering the hearer into the speaker. The hearer then responds, either by saying, “Yes, it was like that with me, too, it happened to me, too,” or, “It was different with me.”1 Narrative makes it possible for us to share our dreams by transforming them into stories and exchanging them for other peoples’ stories. Narrative does not make it possible for us to prove that our dreams are real—it is, as we shall see in this chapter, impossible to prove the reality of a dream, philosophically or logically—but it makes it possible for us to imagine how we might try to prove that they are real.

Yet narrative does not function in dreams precisely as it functions in myth. The compelling causative sequence of events is absent from dreams; the thread of the plot is replaced by a pattern of images that suggest but never actually spell out the story. For this reason, too, proofs cannot be accomplished within dreams, for proofs depend upon the skeletal structure of cause and result that dreams lack. Myths add to dreams precisely the structure that makes such seeming proofs possible.

Narrative implicitly expresses a theory of causation through the sequence of its events. Nowadays, in the West, myth is boxed between history (which is regarded as true) and the novel (which is regarded as untrue), an ambiguous status. But in illo tempore, and in India, to say that something happened is to say that it is true, to force the hand of belief. The only place in which the power of narrative still functions in this way in Western culture is in psychoanalytic case histories—a sharing of dreams—where the truth of the past can often be expressed only when it is formulated as a story.2

Indian narratives have a peculiar penchant for incorporating into themselves elements that we would label philosophy: formal arguments and long discussions that interrupt the story. In our tradition, such matters would be relegated to textual commentaries. India has these, too; but much of what might be placed in a separate commentary is actually drawn into the narrative text, so that the text carries its own commentary around with it, the way a snail carries its house or a turtle its shell. To a Western reader, these passages often seem to spoil the story; such didactic ramblings in the great Sanskrit epics were invariably labeled “interpolations” by the Western scholars who stubbed their toes on them over and over again in the course of a good story. But to an Indian audience, there is no harsh break between the stories and the commentaries; indeed, the Indian audience tends to view the matter quite the other way around: it sees the philosophical argument as the basic genre and the stories as set into it like gems, as focal points, as moments when the philosophy gathers momentum and breaks out of a problem it cannot solve into a mode of thinking that at least allows it to state the problem and to share it in a parable. Ask a European scholar what the Mahābhārata is about and he will probably say, “The battle between the Kurus and the Pāṇḍavas.” An Indian might give the same answer, but most Indians would say, “It is about dharma” What is foreground for one culture is background for another.

An example of the weight that Indians place on the philosophical content of their stories can be seen in the subject matter of the illustrations in the Chester Beatty manuscript of the Yogavāsiṣṭha, There are forty-one of these, and over a third of them (fifteen) depict not the events told in the stories but rather the people who are telling and explaining the stories. In other words, these illustrations depict what we would regard as the frame rather than the picture. Six illustrate the outer frame; of these, three involve Vasiṣṭha and Rāma. Sir Thomas Arnold, the editor of the catalogue, helpfully summarizes what it is that they are all talking about, but these summaries are entirely arbitrary; the pictures are just pictures of people engaged in conversation. These are the ideas that Arnold would print in invisible balloons above the heads of the figures in the drawings: Vasiṣṭha instructs Rāma “as to the means of attaining moksha (salvation)” or “how the Universe is nothing but a mode of the consciousness of Atma” or “how self-introspection may be attained.” Other teachers are said to be telling other people about “the nature of true knowledge” or about “that bliss of perfect knowledge in which there is no pain” or “the true nature of Maya (illusion).” And the final illustration in the manuscript, a painting of two ascetics, apparently catches them at a moment when they are “discussing the origin of the Universe.” To the Western eye, these are like frozen frames in a “talking” motion picture with the sound track turned off; but to the Indians, who already know the sound track by heart, they are highly evocative pictures, full of the motion, not of the body, but of the mind.

In the West, myth is usually the handmaiden of philosophy. Plato lapses into myth from time to time (as in the myth of the dream of Er in the Republic) to state things that, as he himself admits, can never be entirely spelled out in argument.3 This is, I think, a valid parallel as far as it goes, but there are two important distinctions between the ways in which Plato and the Indian narrators fused philosophy and narrative. In the first place, Plato often invented his myths or called on myths that his audience was not familiar with, while the Indian narrator usually has only to remind his audience of a story that they already know well. Second, there was a complex system by which the Indian stories and commentaries were constantly interleaved, interpenetrating each other until we cannot really tell where the argument leaves off and the story begins. They have become each other, like salt placed in water (in the Upaniṣadic metaphor for the pervasion of the universe by the Godhead).4

In India, just as the commentaries are themselves regarded as a form of literature and are built right into the narratives, so, too, is the audience built into the story. Every Indian text is its own metatext, every Epic is its own epi-Epic, which tells you how to react to the text.5 The story that we hear or read is told by a narrator to another person, who answers him and asks questions, speaking for the audience. Often this answerer is himself an actor within the story that is being told; sometimes the narrator tells his own story in the first person. We are familiar with this technique from the way in which Homer uses Odysseus as the singer of tales in his own story; in India, the process is elaborated and manipulated so that there are often several interlocutors on several levels, each raising different philosophical points that arise from the narrative. In keeping track of the story, one often has to supply a series of encapsulating quotation marks: “‘“”’”. These tales are parables about parables, stories about storytelling as well as examples of storytelling. They build the philosophy into the story by placing a running commentary in the mouths of the characters on each of several different levels of narrative. In a similar way, the secondary elaboration is an explicit part of a dream.

In devotional literature, in particular, the speaker and the listener become collapsed into one as the narrative’s functions of communication and communion merge together. People listen to stories not merely to learn something new (communication) but to relive, together, the stories they already know, stories about themselves (communion).6 A. K. Ramanujan once remarked that no Indian ever hears the Mahābhārata for the first time;7 here is a case of cultural déjà vu, a parallel to the déjà vu of lovers on the personal level. In the Rāmāyaṇa, Rāma listens to the two bards, who are his unrecognized sons, telling him his own story, and through the storytelling he eventually recognizes them.8 And in the Adhyātma-Rāmāyaṇa, when Sītā is admonished by Rāma not to come with him to the forest, she replies in exasperation: “Many Rāmāyaṇas have been heard many times by many Brahmins. Tell me, does Rāma ever go to the forest without Sītā in any of them?”9

The fact that the audience can be expected to know the story has other uses, as well. The text can use the audience’s assumptions and expectations to serve new purposes; it does not necessarily fulfill their expectations.10 In this way, a philosophical text can manipulate stories to make a didactic point, using the stories against themselves, setting up traditional tales in order to undermine and change traditional ways of thinking about traditional philosophical problems. In India, philosophy is the context of narrative. We may, if we wish, seek other contexts as well—sociological, economic, psychological—but always the wave of the story casts us up on the sands of philosophy. As philosophy changes over the years, the same story may be asked to serve several different masters. Indians are not troubled by the simultaneous existence of several variants; they know that texts, too, have many doubles.

The Yogavāsiṣṭtha is a text that makes use of traditional motifs in this creative way. The presence in it of numerous intricately intertwined scraps from the ancient Sanskrit and from contemporary folktales indicates that the author of the Yogavāsiṣṭha had a number of stories to call on to illustrate the points he wished to make. It is particularly striking that few of those earlier sources cared to make those points, to explain how it could be that dreams and waking life might interact as they seem to do. To some extent, it is a matter of priorities. The authors of the earlier texts doubtless knew about māyā; this knowledge adds the color and spice and profundity to the basic stories. They make their own points, both implicitly, in the narration of what happens to people, and occasionally explicitly, as when a character justifies his actions or the narrator comments on his actions. But the deeper philosophical points made in the Yogavāsiṣṭha are not drawn out in earlier Sanskrit texts and folktales.

This was because the philosophical arguments were either not yet fully enough developed or not widely enough diffused in the nonphilosophical segments of the culture to be slipped into a story. But, even more, it was because the story was always bigger, more profound, than any explicit argument that could be made to gloss it; the story always symbolized an insight that spilled over, beyond what the storyteller himself could say it meant. The story is a river whose fish keep jumping out. Paul Ricoeur has said that the symbol gives rise to thought; mythology precedes philosophy. More than that: philosophy is a vain attempt to catch up with mythology; philosophy races after mythology and gets closer and closer but never catches it, just as Achilles never quite reaches the tortoise in Zeno’s paradox.

The story does not merely illustrate a theory, as, for instance, George Gamow wrote the tale of Mr. Tomkins in Wonderland to illustrate the theory of relativity. The story may give an example of the theory, but it also says things that the theory does not account for. There is a kind of mutual feedback between story and theory akin to the feedback that we have seen between myth and dream: each nourishes the other. The author of the Yogavāsiṣṭtha hauls the tales in out of the Indian past and spruces them up to pass inspection by a very different judge. Their old meanings, always there if never fully understood, are dragged out to answer new questions, and they stand there squinting and awkwardly flinching in the unaccustomed light. In this new setting, the stories offer a poetic solution to certain metaphysical problems, creating a metaphysic out of imagery.11

The Yogavāsiṣṭtha is a massive Sanskrit text, consisting of some 27,687 stanzas. It was probably composed in Kashmir, sometime between the sixth and twelfth centuries of our era (its date, like that of most Indian texts, is much disputed).12 In the course of this long philosophical argument, the sage Vasiṣṭha tells about fifty-five stories; many of them are brief parables, but several are long, baroque, elaborately poetic renditions of complex adventures. These stories are both traditional and non-traditional; that is, they build on certain standard Indian narratives of illusion and dreams, but they build new stories out of the old themes, often with an entirely new philosophical point.

The stories in the Yogavāsiṣṭha are stories within another story. The full title of the Yogavāsiṣṭha is the Yogavāsiṣṭtha-Mahā-Rāmāyaṇa, or “The great tale of Rāma as told by the sage Vasiṣṭha in order to expound his philosophy of yoga.” This long poem is attributed to the poet Vālmīki (who is the author of the first Sanskrit Rāmāyaṇa) and is about an incident in the life of Rāma that was not dealt with in the earlier Rāmāyaṇa: a long conversation with the sage Vasiṣṭha. Thus, even the Yogavāsiṣṭha as a whole is a metatext, filling in the supposed gaps in the older text on which it purports to be based, just as many folk versions of the Rāmāyaṇa do. Similarly, Tom Stoppard’s Rosenkrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead fills in certain gaps in Shakespeare’s Hamlet.

The Yogavāsiṣṭha is well loved by Indians; it has been translated into many of the vernacular languages of India and has found its way into “anonymous” oral traditions.13 In this way, although it is a highly sophisticated Sanskrit composition, it both grows out of folklore and grows back into folklore in yet another instance of mutual feedback. (A parallel might be seen in the way in which “Old Man River,” composed by the sophisticated Jerome Kern and Oscar Hammerstein II, is based on folk themes and regarded by many Americans as a folk song.) The Yogavāsiṣṭha was (and may have been intended to be) a means by which sophisticated philosophical ideas were transmitted to an audience that was well educated (able to read Sanskrit) but probably not well trained in philosophy. The text is a curious blend of abstract, classical Indian philosophy and vivid, detailed Indian folklore, a kind of Classic Comics version of the doctrine of illusion.14 In it, a philosophy that often seems hollow or arbitrary comes to life when the narrative spells out its widest implications. It is as if someone took the abstract concept “The universe is illusory” and made it somehow anthropomorphic, producing a kind of teaching device to make us understand what it feels like to realize that everything is an illusion. And it can’t be done; in our hearts, we don’t believe it. But the narrative does not merely discuss this problem; it enacts it. Like dreams, which are not so much thought (with logic and causation) as experienced (emotionally and in images), the Yogavāsiṣṭha presents us with experiences that make the thoughts real. The narrative allows us—nay, forces us—to imagine ourselves in a situation in which we must believe in the doctrine of illusion, in which we must act out the paradox.

Among the many tales in the Yogavāsiṣṭha, I have chosen a few that seem to me particularly powerful and beautiful examples of this genre.15 Two of them are, I think, best read together, as expressions of the Yogavāsistha’ s approach to the problem of psychology or epistemology; these are the tales of King Lavaṇa and the Brahmin Gādhi. Later we will look at other stories, such as the tale of the monk who met the people in his dreams, which reformulate these same problems and make a more direct approach to the problem of ontology.

The King Who Dreamed He Was an Untouchable and Awoke to Find It Was True

Let us begin with the story of King Lavaṇa.

In the lush country of the Northern Pāṇḍavas there once reigned a virtuous king named Lavaṇa, born in the family of Hariścandra. One day when Lavaṇa was seated on his throne in the assembly hall, a magician entered, bowed, and said to the king, “While you sit on your throne, watch this marvelous trick.” Then he waved his peacock-feather wand, and a man from Sindh entered, leading a horse; and as the king gazed at the horse, he remained motionless upon his throne, his eyes fixed and staring, as if in meditation. His courtiers were worried, but they remained still and silent, and after a few minutes the king awoke and began to fall from his throne. Servants caught him as he fell, and the king asked, in confusion, “What is this place? Whose is this hall?” When he finally regained his senses, he told this story:

“While I was sitting in front of the horse and looking at the waving wand of the magician, I had the delusion that I mounted the horse and went out hunting alone. Carried far away, I arrived at a great desert, which I crossed to reach a jungle, and under a tree a creeper caught me and suspended me by the shoulders. As I was hanging there, the horse went out from under me. [See plate 4.] I spent the night in that tree, sleepless and terrified. As I wandered about the next day, I saw a dark-skinned young girl carrying a pot of food, and, since I was starving, I asked her for some food. She told me that she was an Untouchable [a Caṇḍāla] and said that she would feed me only if I married her. I agreed to this, and, after she fed me, she took me back to her village, where I married her and became a foster Untouchable. [See plate 5.]

“She bore me two sons and two daughters, and I spent sixty years with her there, wearing a loincloth stinking and mildewed and full of lice, drinking the still-warm blood of wild animals I killed, eating carrion in the cremation grounds. Though I was the only son of a king, I grew old and gray and worn out, and I forgot that I had been a king; I became firmly established as an Untouchable. One day, when a terrible famine arose and an enormous drought and forest fire, I took my family and escaped into another forest. As my wife slept, I said to my younger son, ‘Cook my flesh and eat it,’ and he agreed to this, as it was his only hope of staying alive. I resolved to die and made a funeral pyre, and, just as I was about to throw myself on it, at that very moment, I, the king, fell from this throne. Then I was awakened by shouts of ‘Hurrah!’ and the sound of music. This is the illusion that the magician wrought upon me.”

As King Lavaṇa finished this speech, the magician suddenly vanished. Then the courtiers, their eyes wide with amazement, said, “My lord, this was no magician; this was some divine illusion sent to give enlightenment about the material world that is a mere mental delusion.” The king set out the very next day to go to the desert, having resolved to find once more the wasteland that had been reflected in the mirror of his mind. With his ministers, he wandered until he found an enormous desert just like the one he had known in his thoughts, and to his amazement he discovered all the exact details he had imagined: he recognized outcaste hunters who were his acquaintances, and he found the village where he had been a foster Untouchable, and he saw this and that man, and this and that woman, and all the various things that people use, and the trees that had been withered by the drought, and the orphaned hunter children. [See plate 6.] And he saw an old woman who was his mother-in-law. He asked her, “What happened here? Who are you?” She told him the story: a king had come there and married her daughter, and they had had children, and then the drought came and all the villagers died. The king became amazed and full of pity. He asked many more questions, and her answers convinced him that the woman was telling the story of his own experience of the Untouchables. Then he returned to the city and to his own palace, where the people welcomed him back.16

The Brahmin Who Dreamed He Was an Untouchable Who Dreamed He Was a King

The story of King Lavaṇa, though complete in itself, is further illuminated by comparison with the story of the Brahmin Gādhi.

There was once a wise and dispassionate Brahmin named Gādhi, who performed asceticism by submerging himself in a lake until the god Viṣṇu appeared to him and offered him a boon. [See plate 7.] Gādhi asked to see Viṣṇu’s power of illusion, and Viṣṇu promised him that he would see illusion and then reject it. After Viṣṇu vanished, Gādhi came out of the lake and went about his business for several days. One day he went again to bathe in the lake, and as he went into the water he lost consciousness and saw his own body dead in his own house, being mourned by his wife and his mother and all his friends and relatives, and then he saw them carry his body to the burning grounds and burn his corpse to ashes.

Then, as he remained in the water, Gādhi saw himself reborn as an Untouchable [a Pulkasa] named Katañja: he saw himself squashed inside the disgusting womb of an Untouchable woman, then born, and then growing up as a child. He went hunting with his dogs, married a dark Untouchable woman, made love to her, had many children, and gradually became old. Then, since he outlived all his family, he wandered alone in the wilderness until, one day, he came to the capital city, where the king had just died. The royal elephant picked him up with its trunk, and he was anointed King Gavala in the city of the Kīras, since no one knew that he was an Untouchable. He reigned for eight years, until one day an old Untouchable saw him when he was alone and without his regalia; the old man addressed him as his friend Katañja, thereby identifying him as an Untouchable, and this encounter was witnessed by several people. Though the king repudiated what the Untouchable had said, all his servants refused to touch him, just as if he were a corpse; the people fled from him, his Brahmin ministers all committed suicide because they had been polluted, and the city was in chaos. Realizing that all this was his fault, Gavala decided to immolate himself along with his ministers. As the body named Gavala fell into the fire and became a tangle of limbs, the painful spasms of the burning of his own body in the fire awakened Gādhi in the water.

Gādhi came to his senses and got out of the lake, but he was puzzled when he recalled the wife and mother who had mourned for him, since his parents had died when he was an infant, and he had no wife, nor indeed had he ever seen the true form of a woman’s body. He went home and lived as before, until, after a few days, a Brahmin guest came to his house and casually mentioned that in the Kīra country an Untouchable had been king for eight years until he was discovered and immolated himself, together with hundreds of Brahmin ministers. Gādhi asked him many questions and verified all the details, in amazement and dismay. Then he went to see for himself, and he found the country that he had thought of in his mind: the Untouchables’ huts and all the rest. He asked about Katañja and was told that he had outlived all of his large family, left the village, and become king of the Kīras for eight years, until the citizens unmasked him and he entered the funeral pyre. The Brahmin Gādhi spent a month in the village and learned all the details from the villagers, just as he had experienced it. Then he journeyed to the city of the Kīras and saw all the places he had seen and experienced, and there too he asked and learned about the Untouchable king, who had, they said, died twelve years ago. Seeing the new king, as if he were seeing his own former life before his own eyes, Gādhi felt as if he were experiencing a waking dream, an illusion, a magic net of mistakes.

Then he remembered that Viṣṇu had promised to demonstrate the great power of illusion, and he realized that his enigmatic experience had been precisely that demonstration. He went out of the city and lived for a year and a half in mounting curiosity and puzzlement, until Viṣṇu came to him and explained the nature of his illusion. When Viṣṇu vanished, Gādhi went back to the Untouchables once more to test his delusion; more convinced than ever that he really had been there, and therefore more puzzled than ever, he propitiated Viṣṇu again, and again Viṣṇu explained how Gādhi had seen what he had seen. When Viṣṇu had vanished, Gādhi’s mind was all the more full of agony; then Viṣṇu returned and explained it all to him a third time, and then, at last, Gādhi’s mind found peace.17

Lavaṇa and Gādhi: Mutual Similes

These stories of Lavaṇa and Gādhi are long and complex; they occupy over sixty pages of Sanskrit text and are marbled with various metaphysical asides, to which we will turn our attention soon. It may seem perverse to combine two stories each of which is challenging enough on its own; in particular, it may appear to be asking for trouble to explain the story of Lavaṇa by having recourse to the story of Gādhi, which is so complex that the story of Lavaṇa seems a mere anecdote by comparison. Yet, when we set the stories side by side, they produce a double image of mutually illuminating similes, each standing for the other.

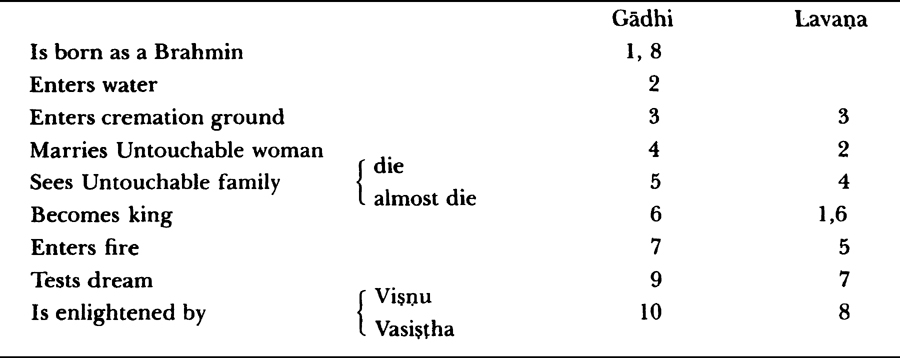

Comparison of the two stories is justifiable on the grounds that the Hindus themselves would have been likely to compare them. The Yogavāsiṣṭha tells over fifty stories, but these two are among the longest and the most important, and both of them are well known in India. Surely the Hindus would have noted, as did von Glasenapp, the striking similarities between the two tales.18 Lavaṇa is a king who dreams that he is an Untouchable in a cremation ground and then goes back to being a king. Gādhi is a Brahmin who dreams first that he is in a cremation ground (his own death place) and then that he is an Untouchable in an Untouchable village, who pretends to be a king, goes back to being an Untouchable when he is unmasked, and ends up as a Brahmin once more. Lavaṇa’s experience of the woman who appears to him in the desert and vanishes when he returns to court is structurally similar to that of King Taladhvaja, the man to whom the female Nārada appears; Gādhi, on the other hand, is far closer to Nārada himself, undergoing his transformation under water and returning to his ascetic life at the end. When we set the Gādhi pattern against the Lavaṇa pattern, it might appear that Lavaṇa takes up the Gādhi story at midpoint: a king who remembers that he has been an Untouchable (see figure 2).

Certain things happen to both of them in the same way. From the standpoint of the onlookers in the outer scene, both are said to have spent only a few “moments” (muhūrtas) in the alternative reality, but, from the standpoint of the participants in the inner scene, they were said to have lived there for many years. Lavaṇa, when he is an Untouchable, forgets that he was a king, and Gādhi, when he is a king, forgets that he was an Untouchable. In addition to the fires in which both commit suicide, each experiences a major conflagration like doomsday: for Lavaṇa it is the forest fire that arises in the drought; for Gādhi it is the great communal immolation fire. And the verses describing the ghastliness of the Untouchables’ villages are strikingly similar in the two stories.

Lavaṇa undergoes an initiation that is like a death and rebirth, but there is no clear break; he enters the Untouchable village in the persona of a king and only gradually sheds it (just as Gādhi enters the city as an Untouchable and changes into a king). This is the mild form of the transformation, brought about in a natural way by motion through space (by horse or on foot); it is the equivalent of the romantic adventure in which the hero simply rides his horse into the other world. Both Lavaṇa and Gādhi experience mild transitions of this kind. Lavaṇa is recognized as a king in the Untouchable village; though he gradually forgets this identity, his mother-in-law remembers that a king had married her daughter. He can be recognized because the two adventures happen in a single time-span. Similarly, Gādhi (Gavala) is recognized as an Untouchable in the royal city, for the same reason, and he still remembers that he is an Untouchable; he lies, but he knows the truth.

Figure 2. Lavaṇa and Gādhi: Mutual Similes

(Numbers indicate the sequence of events within each myth.)

But the mother-in-law does not recognize Lavaṇa when he returns to the village, nor do the townspeople recognize Gādhi when he returns to ask his questions. This is because each of them has experienced a return journey that is not a simple natural voyage but is, rather, a rude awakening, a violent transition by fire. On the way back, they have become reborn, losing in a single moment the many years they had amassed in the course of their gradual journey into the other world. To this extent, their experiences are roughly the same in their inner structure (a mild transition followed by a violent transition), though they are mirror opposites in the actual content of that structure: where Lavaṇa goes from king to Untouchable, Gādhi goes from Untouchable to king.

But the reversals are even more striking. What is real for Lavaṇa becomes a simile for Gādhi, and what is real for Gādhi is merely a simile for Lavaṇa. The stories are most vividly opposed in their outer structures. Before his mild transition, Gādhi actually dies; he is then reborn and experiences an entirely new life, beginning with his existence as an embryo. This transition (which takes place under water, like Nārada’s transformation) never happens to Lavaṇa at all. Lavaṇa learns that his illusion is “like seeing one’s own death in a dream,”19 but Gādhi actually does watch his own death and rebirth. On the other hand, the death that Lavaṇa as Katañja really does experience (in the inner story), as a result of the drought and the forest fire, appears as a recurrent simile in the story of Gādhi as an Untouchable: Gādhi sees his corpse “like a leaf that has lost its sap, like a tree that has been brought down by a terrible storm, like a village in a drought, like an old tree covered with eagles”; when he grows old as an Untouchable, he is worn out like the ground in a drought, and his body dries up like a tree in a drought; his family is carried away by death, like forest leaves carried off by a torrent of rain, and he leaves the forest as a bird leaves a lake in a drought; death cuts away his whole family, as a forest fire cuts down a whole forest. The courtiers flee from Gādhi as Gavala, refusing to touch him, as if he were a corpse; yet when Gādhi as Brahmin sees the ruins of his old house, he is like the soul looking at its dried-up corpse.20 One man’s reality is another man’s simile.

In this way, the Lavaṇa story, seen as framed by the Gādhi story, may imply another level, retroactively: A Brahmin may have dreamed that he was Lavaṇa, who dreamed that he was an Untouchable. On a simpler plane, the following questions might arise when we compare the two stories: Which is the object and which is the image of it? What is like what? What is a simile for what? The idea, on the philosophical level, that everything is merely a reflected image of something else (pratibhāsa) is supported on the rhetorical level by the compelling network of similes: everything is likened to something else.

The metaphysical stances of the two tales also differ greatly. Lavaṇa is inside his story and is entirely overwhelmed and mystified by it until the very end; to him, his persona as king certainly seems far more real than his persona as Untouchable, yet he forgets that he ever was a king. The creator of the mirage, the demon or god who is laughing at him, the puppeteer working the strings, remains offstage, invisible to Lavaṇa and to us. Gādhi, by contrast, is outside his story all the time, watching himself play out his scene like a television actor with one eye on the monitor. Sir Ernst Gombrich has suggested that, for visual phenomena, “Illusion, we will find, is hard to describe or analyze, for though we may be intellectually aware of the fact that any given experience must be an illusion, we cannot, strictly speaking, watch ourselves having an illusion.”21 Lavaṇa cannot watch himself having an illusion, though he later realizes that he has had one and comes to understand it and to extricate himself from it. But Gādhi quite literally watches himself watching. To Gādhi, his persona as an Untouchable is far more real than his persona as a king—which is merely a mask within a dream, twice removed from even apparent reality—but both are equally unreal in comparison with his true persona as a Brahmin.

For us, as Westerners, the finality of the Brahmin persona is challenged by the self-perpetuating layers of the story: Why could there not be a woman, say, dreaming that she was a king dreaming . . .? In fact, this cannot happen in our text. For the Hindu, the chain stops with the Brahmin, the linchpin of reality, the witness of the truth. To the extent that the Brahmin represents purity and renunciation, he is real, safely outside the maelstrom of saṃsāra and illusion. Our confusion about our own place in the frames of memory, one contained within another like nesting Chinese boxes, is shared by Lavaṇa until the very end of his tale. But to Gādhi, who is, after all, a Brahmin, the god who pulls the strings is directly manifest and takes pains to open up his bag of tricks right from the start; moreover, he returns three times at the end to make sure that Gādhi has understood his lesson properly.

One implication of this structure is that the entire series of frames is a model of society.22 It is in the nature of social distinctions such as caste to allow each person to frame the whole set of the others. Caste is not a simple stratification but a set of interlocking hierarchies: each person’s circle encompasses the circle of all others. If we turn for a moment from the Yogavāsiṣṭtha stories to Hindu society in general, it is obvious that, from the standpoint of the Brahmin, the Untouchable is impure. It is less obvious, but equally true and equally important, that, from the standpoint of the Untouchable, the Brahmin is impure. Louis Dumont was the first to point out (in Homo Hierarchicus) some of the ramifications of this complex system, which is reflected in the metaphysics rather than in the muted social conscience of the Yogavāsiṣṭha (to which we will soon return). From the standpoint of caste and the criterion of purity, the Brahmin and the Untouchable live in a kind of symbiosis, a paradox of reciprocity. From the standpoint of power, which is so often the partner of purity in Indian conceptual schemes, the king and the Untouchable form such a reciprocal bond. And from the standpoint of society as a whole, the king and the Brahmin supply the double axis from which all other interrelationships are derived. Yet they alone cannot provide the entire grid on which the social cosmos can be mapped. Though the Brahmin provides the latitude and the king the longitude, the Untouchable provides a pole of pollution by which both of the others orient themselves. The Brahmin, the king, and the Untouchable are the players in the eternal triangle of purity, power, and pollution.

The dream of becoming either a Brahmin or a king is a very ancient theme in India. One of the earliest Upaniṣads, composed before 700 B.C., describes the paradigmatic dream in these terms:

When he dreams, these worlds are his. Then he seems to become a great king. Then he seems to become a great Brahmin. He seems to enter into the high and low. As a great king takes his people and moves about in his own country just as he wishes, just so this one takes his own senses and moves about in his own body just as he wishes.23

Here the metaphor of the king preempts the metaphor of the Brahmin and becomes the basis of an extended somatic simile: the human body is indeed a model of society.

The experience of the king who becomes an Untouchable and the experience of the Brahmin who becomes an Untouchable share certain themes but diverge in several important ways. As we will see, either can be transformed into an Untouchable for any of a number of reasons: as punishment for a sin, or in order to learn something of value, or as part of an initiation. But just as the initiation of a king (royal consecration) is different in both form and purpose from the initiation of a Brahmin (preparation for sacred office), so, too, the kinds of transformations that Lavaṇa and Gādhi undergo are very different. The drama of Lavaṇa’s transformation lies in the contrast between the splendor of his life at court and the squalor of his life in the village. The drama of Gādhi’s transformation lies in the contrast between his purity as a Brahmin and his impurity as an Untouchable. In both cases, the fall in social status is extreme; but the king loses, in addition, what we might term economic or political status, while the Brahmin loses sacred or religious status. Let us deal separately with the different problems the king and the Brahmin face when each of them becomes an Untouchable.

The Suffering of the Hindu King

The problem encountered by the Untouchable king is reflected in the quandary described in the frame of the Lavaṇa story, the conversation between Rāma and Vasiṣṭha. The occasion for the discussion is this: Rāma has returned from a pilgrimage in a state of depression and madness (or so his father and the courtiers describe it). Rāma regards as a babbling madman anyone who says, “Act like a king,” though he himself laughs like a holy man whose mind is possessed. He says that everything is unreal, that it is false to believe in the reality of the world, that everything is but the imagination of the mind. He is physically wasting away. The sage Viśvāmitra, who is called in by Rāma’s father, the great emperor Daśaratha, says that Rāma is perfectly right in his understanding of the world, that he has been enlightened. Viśvāmitra then offers to cure him.24

We thus encounter, right at the start, several conflicting interpretations of human reality. Is Rāma crazy, or is he right? Is everyone else crazy? Why does Viśvāmitra offer to cure him if he is not mad? The Yogavāsiṣṭtha suggests that enlightenment by a suitable spiritual authority will remove Rāma’s depression while leaving his (correct) metaphysical apprehensions unimpaired. In Western terms, this is a kind of psychoanalysis that allows the fantasy to continue while making the patient socially functional; stated in Yogavāsiṣṭha terms, it allows the fantasy to be dispelled while making the patient socially functional. Thus Rāma’s father calls in the sage Vasiṣṭha to assist Viśvāmitra, and Vasiṣṭha cures Rāma by assuring him that he is perfectly right. Viśvāmitra says, “What Rāma knows inside him, when he hears that from the mouth of a good man who says, ‘That is true reality,’ then he will have peace of mind.”25 In the tale of Lavaṇa, as in the framing story of Rāma, this corroborating function is performed by the sage Vasiṣṭha.

But the true nature of Rāma’s madness is hinted at when people tell him to act like a king, and this madness can best be understood in the context of Indian mythology. Rāma’s pilgrimage has been his first experience of suffering, and in reaction to this he has reevaluated his life as a king and found it to be unreal. The sage who persuades him to go on living his life despite this new insight is performing a role close to that of the incarnate god Kṛṣṇa in the Mahābhārata; for there, when Arjuna is depressed by the imminent death of his relatives (the situation that was used to extricate Lavaṇa and Nārada from their dream existences), Kṛṣṇa persuades him to go on anyway, to “act like a warrior.” Several verses of this dialogue (the Bhagavad Gītā) are closely akin to some in the Yogavāsiṣṭha and may have been in the back of its author’s mind.26 To this extent, at least, the Yogavāsiṣṭha argues that the most important reality—that is, what is most valued, if not necessarily most solid physically—is social reality. This is, of course, a most orthodox Hindu point of view. In this logic, to know that a course of action is intrinsically unreal is an argument to do it, not an argument not to do it. When Arjuna realizes that he is not really killing his cousins, he can go on and kill them; when Rāma realizes that he is not really a king, he can go on and rule.

The Indian king found himself by definition in an ambivalent position. His basic dharma, or social duty, was to rule, to “act like a king,” and this dharma is affirmed even in the myths of illusion. When Nārada returns to being Nārada after having been a queen, Viṣṇu advises his erstwhile dream-world husband, King Tāladhvaja, to stop neglecting his royal duties, and the king returns to his responsibilities. According to the Hindu textbooks on dharma, the king is not allowed to renounce his kingdom; in the Mahābhārata, King Yudhiṣṭhira agonizes over this problem for a long time and finally resigns himself to remaining king. In Buddhism, however, as we will see, kings do renounce their office. The Buddha himself set the example, and it is relevant to note that Yudhiṣṭhira, like the philosopher Śankara, was accused of being a closet Buddhist (pracchannabauddha). Moreover, the Mahābhārata heroes do spend twelve years in exile, and the Rāma of the Vālmîki Rāmāyaṇa, who has certain Buddhist leanings, is forced to renounce his throne for a while; he dwells among animals and demons in the forest and in Lankā (a kind of other world) before he returns to resume his duties as the true king. This theme of royal renunciation appears in the Yogavāsiṣṭha when Rāma returns from his pilgrimage and does not wish to be a king. Torn between the Hindu and Buddhist concepts of kingship and renunciation, what better compromise could an Indian king find than to dream of renouncing?

This compromise is also reflected in a subepisode of the tale of Lavaṇa in which the king creates a mental sacrifice. When Rāma expresses his puzzlement at the apparent contradictions in the story of Lavaṇa, Vasiṣṭha tells this story:

Once, in the past, Lavaṇa recalled that his grandfather, Hariścandra, had performed the sacrifice of royal consecration, and he resolved to perform that sacrifice in his mind. He made all the preparations mentally: he summoned the priests and honored the sages, invited the gods and kindled the fires. A whole year passed as he sacrificed to the gods and sages in the forest, but then the king awoke at the end of a single day, right there in the palace grove. Thus by his mind alone King Lavaṇa achieved the fruits of the sacrifice of royal consecration. [See plate 8.] But those who perform the sacrifice experience twelve years of suffering through various tortures and hardships. Therefore Indra sent a messenger of the gods from heaven in order to make Lavaṇa suffer. This messenger was the magician, who created great misfortune for the king who had performed the sacrificial ritual of consecration, and then the messenger returned to heaven.27

Out of his compassion for King Lavaṇa, Indra substitutes for the real suffering he would normally have undergone an experience of suffering (a long period of existence as an Untouchable) that occupies just a moment in his life as a king. What is perhaps most striking in terms of the problem set forth by the text—the interaction between mental experience and physical evidence—is the fact that, in order to ground the king’s mental experience in physical reality (so that he may have the fruits of the mental sacrifice in his real life), the gods send him imaginary sufferings that he may fulfill the (real) requirements of the traditional initiation. For his imaginary sufferings among the Untouchables are less real than an actual consecration, involving hardships, but more real than an imaginary consecration involving no hardships. Unhappiness is more real than happiness.

Lavaṇa’s initiation bears a certain resemblance to shamanic initiations.28 But there is a source for the theme of the imaginary consecration that is more specifically Indian than the Central Asian shamanistic corpus and is also more directly relevant to the tale of Lavaṇa. To this day, many Indian sects hold that anyone who dreams that he is initiated has in fact been initiated. This belief has an ancient precedent. In the Vedic sacrifice (the very one that Lavaṇa managed to perform mentally, though with the assistance of a number of mentally conjured priests, as the text and plate 8 demonstrate), one particular priest was employed as the witness. This priest, the Brāhman, did absolutely nothing; his job was to sit there and to think the sacrifice while the others did it. He was the silent witness, essential to the sacrifice, in particular because he was responsible for ensuring that no mistakes occurred. From this practice (three priests performing the sacrifice, while one—the “transcendent fourth” in Indian culture—performed it mentally) it was not a very large step to take to reach the practice in the Upaniṣads, where meditation on the sacrifice was far more important than its actual performance; and from there it was no great further distance to the purely imaginary sacrifice of the Yogavāsiṣṭtha.

Hariścandra among the Untouchables

It is particularly ironic that Lavaṇa modeled his imaginary consecration on that of his grandfather, Hariścandra, since Hariścandra himself experienced a dreamlike initiation among Untouchables, like that of Lavaṇa himself, in addition to his conventional initiation. This story, which can be traced back to the eighth century B.C.,29 is told more elaborately in the Purāṇas:

One day when King Hariścandra was hunting in the forest, the King of Obstacles, who was jealous of Hariścandra’s great achievements, entered him. As a result of this possession, Hariścandra in fury cursed Viśvāmitra to fall into a deep sleep. Viśvāmitra then became furious in turn, and Hariścandra became contrite and begged Viśvāmitra to forgive him. Viśvāmitra made Hariścandra promise to give him everything he had, and, in order to pay Viśvāmitra, Hariścandra sold his wife and son to an old Brahmin. Then Hariścandra said, “I am no human, but an ogre, or even more evil than that.” Still Viśvāmitra demanded more payment, and then the god Dharma approached Hariścandra in the form of an Untouchable [a Caṇḍāla], foul-smelling and disfigured, and, in order to pay Viśvāmitra, Hariścandra sold himself in slavery to the Untouchable and went to work in the cremation ground, stripping the corpses of their clothing. With its jackals and vultures, heaps of bones and half-burnt bodies, the burning ground was like the world at doomsday. The singing of the throngs of vampires and ghouls sounded like the screams of doomsday, and the yells and moans of the mourners sounded like the cries of hell. Thus the king, while still alive, entered another birth, and thus he passed a year that seemed like a hundred years.

One day Hariścandra fell into an exhausted sleep, motionlessly dreaming that he paid for his lapse by suffering for twelve years. He saw a great wonder: He saw himself reborn as a Pulkasa [a different kind of Untouchable], out of the womb of a Pulkasa woman. He grew up, and when he was seven years old he went to work in the cremation ground. One day some Brahmins brought a dead Brahmin there, and when the boy asked them for the payment due him they refused, saying, “Go on and do your evil job. Once upon a time, Viśvāmitra cursed King Hariścandra to be a Pulkasa because he had lost his merit by injuring the Brahmin with sleep.” They went on mocking him like this, and, when he could no longer bear it, they cursed him to go to hell. Immediately he was dragged off to hell, where he was horribly tortured, still in the form of a seven-year-old Pulkasa. He stayed there for one day, which was a hundred years, for that is what the denizens of hell call a hundred years.

Then he was reborn on earth as a dog, eating carrion and vomit. And he saw himself reborn as a donkey, an elephant, a monkey, an ox, a goat, a cat, a heron, a bull, a sheep, a bird, a worm, a fish, a tortoise, a wild boar, a porcupine, a cock, a parrot, a crane, a snake, and many other creatures; and a day was like a hundred years. Finally he saw himself reborn again as a king, who lost his kingdom playing dice; his wife and son were taken from him, and he wandered alone into the forest. At last he went up to heaven, but Yama’s servants came to drag him away to hell with nooses made of serpents. At that moment, however, Viśvāmitra spoke to Yama about Hariścandra, and Yama told his servants what Viśvāmitra had done. Then the change in him that had come about from a violation of dharma ceased to grow. Yama said to him, “Viśvāmitra’s anger is terrible; he is even going to kill your son. Go back to the world of men and experience the rest of your suffering, and then you will find happiness.” These were all the conditions that Hariścandra saw in his dream and experienced for twelve years. And at the end of this period of twelve years of suffering, the king fell from the sky, hurled out by Yama’s messengers.

As he fell, he woke up in confusion [sambhramāt], thinking, “In my dream I saw great suffering, with no end. But have twelve years passed, as I saw in my dream?” He asked the Pulkasas who were standing there, and when they said, “No,” the miserable king sought refuge with the gods, praying, “Let all be well with me, and with my wife and son.” Then he went back to work as a Pulkasa, selling corpses, and seemed to lose his memory; there was no wife or child within the range of his lost memory.

One day his wife came there, bringing the body of their son, who had died of snakebite. As she grieved over the little corpse, Hariścandra saw her and hastened toward her, thinking only to take the clothing from the corpse. She saw him, too, but they had been so changed by their sufferings in their long exile that they did not recognize each other; she was so transformed that she looked like a woman in another birth. But when the king saw the dead child, he remembered his own son, and when he heard the queen lamenting for her husband, Hariścandra, he recognized his wife and son. He spoke, and the queen recognized his voice; she also recognized the shape of his nose and the spacing of his teeth. But when she saw that he was an Untouchable, she clasped him around the neck and said, “O King, is this a dream, or is it real [tathyam]? Tell me what you think, for my mind is confused [mohita].” The king told her how he had come to be a dog-cooker, and she told him how their son had died. They resolved to immolate themselves together on the pyre of their dead son, but at that moment Indra and Dharma came there with all the gods and told them that they had won the right to eternal worlds, together with their son. Indra revived the boy and brought all three of them to heaven.30

In this story, metaphors and transformations replace one another, as do demons and Untouchables. Hariścandra says that he is like an ogre long before he becomes an Untouchable, and even that transition takes place not by magic (by a sudden transformation of his skin and body, as in the case of Triśanku) but simply by habit: he acts like an Untouchable, and so he is an Untouchable. Years of behaving like an Untouchable transform him until even his wife cannot recognize him at first. Her recognition involves physical evidence: she recognizes his voice and his physiognomy, hard material signs that shine through despite the dirt and disease and scars and wrinkles. But when she sees that he is an Untouchable, dark-skinned after years of working in the sun, and hideously clad, she rejects the reality of that vision, calling him “King” and hoping to dismiss the whole tragedy by saying, “It is all just a dream.”

Many of the motifs in this myth appear in the tales of Lavaṇa and Gādhi. The death of a son and the decision to enter the fire lead to the sudden awakening, and the experience of life as an Untouchable purifies the king and gives him release. But in this text (which is set in the context of saṃsāric traditions and devotional values), that release is not mokṣa but physical transportation to heaven, and it is a worldly heaven, like Triśanku’s, not an abstract merging with Godhead. In the end, Hariścandra and his wife do not go back to their original life, as Lavaṇa and Gādhi do; they leave both the earthly dream and the earthly reality, the royal pleasures and the Untouchable horrors. And Hariścandra’s wife from the real world suffers with him inside the other world (though not inside the dream within the dream or even in the same part of the other world, the same Untouchable village). Hariścandra has no Untouchable wife, therefore, and no Untouchable child; his entire family moves into the nightmare with him, and at the end they move out of it with him to heaven. Even the child whose death precipitates the awakening is himself awakened from the dead in time to go to heaven, a bhakti twist that wipes out the final traces of any orientation toward mokṣa. The heaven to which they are all transported is probably not yet the eternal, infinite heaven of the full-fledged bhakti movement but simply the heaven of Indra, a place where earthly pleasures are greatly magnified and from which one must eventually return to earth.

The metaphor of transformation is acted out in several ways. Hariścandra is “like” an Untouchable and then becomes one; he is “as if” reborn and then dreams that he is actually reborn; the cremation ground is “like” hell, and then Hariścandra dreams that he is actually in hell. And the metaphor of the expansion and contraction of time is realized in several ways. Because of the ghastliness of the king’s experience among the Untouchables, each year seems like a hundred years (a characteristic of dream adventures in general). But when the king dreams that he is in hell, he discovers that, in that world, there is another system of time reckoning: the people in hell call what we would call a hundred years “a day.” And when the king dreams that he must suffer for twelve years to expiate his sin, he believes this; when he wakes up, he is deeply depressed to discover that twelve years have not, in fact, elapsed in the waking world; only one night has passed, the night in which he dreamed. He is convinced of this by some Pulkasas—the same Pulkasas who were there in his dream; now they are outside the dream, and they set the standard of reality. Unlike King Lavaṇa, Hariścandra must suffer in reality, in real time, the twelve years of suffering that are the traditional initiation of a king; the dream of twelve years does not count.

The Suffering of the Buddhist King

The tale of Hariścandra may well have been influenced by the Vessantara Jātaka, the famous Buddhist story of a king who was generous to a fault. As Richard Gombrich remarks, the tale of Vessantara is a thoroughly Buddhist story, but “it is interesting that another story of a man who gave away his family, Hariścandra, is extremely popular in Hindu Bengal. We posit that a story, like any other social phenomenon, is most likely to survive and flourish when it answers the most disparate purposes, in other words when its appeal is overdetermined.”31 In addition to the purposes that it served for the Buddhists, the tale of Vessantara clearly had meanings for the Hindus, meanings that we have encountered in other, related stories, and particularly in the tale of Hariścandra.

King Vessantara gave away everything; one day he gave away the royal elephant, and for this excess he was banished. While he wandered in the forest with his wife, Maddī, and their two children, a wicked Brahmin named Jūjaka determined to ask Vessantara for the children. That night, Maddī dreamed that a black man wearing yellow robes, with red flowers in his ears, dragged her out of the hut by her hair, threw her down on her back, and, ignoring her screams, tore out her two eyes, cut off her two arms, cut open her breast, and tore out her heart and carried it away, dripping with blood. She awoke in terror and went to Vessantara’s hut to ask him to interpret her dream. At first he asked her why she had violated her promise not to approach him at night except during her fertile season, but she said, “It is not improper desires which bring me here; I have had a nightmare.” Then he asked her to tell him her dream, and when he heard it he realized that it meant that someone would ask him for his children, the final test and perfection of his generosity. But he said to Maddī, to calm her, “Don’t worry; because you were lying in an awkward position, or perhaps because you ate something that disagreed with you, your mind was disturbed.” She was deceived and consoled by this; she kissed the children and embraced them and left them in Vessantara’s care.

Then Jūjaka came and asked for the children, and Vessantara gave them to him. As Maddī returned to the hermitage, she thought about the nightmare she had had, and so she hurried home. Then her right eye began to throb, and trees with fruit seemed bare, and bare trees seemed to have fruit, and she completely lost her bearings. Eventually, Vessantara told her what had happened, and she praised his generosity. Indra then took the form of a Brahmin and asked Vessantara to give Maddī to him; he did so, but then Indra gave her back again. Finally, Vessantara was called back out of exile, and he and Maddī were reunited with their children. And the noble king Vessantara, full of wisdom after so much giving, at the dissolution of his body was reborn in heaven.32

Many of the elements in this story seem to be transformations of another famous Buddhist story that we have seen, the dream of Aśoka. Maddi’s dream, like Anoka’s, is a textbook nightmare that foretells a tragedy that will befall a child, a nightmare that does come true. Vessantara lies to her about it, as Aśoka’s wicked queen lies to him; the interpreter of the dream—Vessantara in the one tale, Aśoka’s wife in the other—knows that the dream is truly prophetic but says that it is merely somatic. Maddi (like Aśoka’s son, Kunāla) sees and rightly interprets a set of evil omens and the image of a topsy-turvy world. The roles are curiously mixed in their transformations: Maddī is like Aśoka in having the dream, but she is like Aśoka’s wife in her sexual threat to the king, and it is Vessantara, not Maddī, who is the primary hero of the tale. In the end, all is restored; after his nightmare existence in the wilderness, Vessantara returns to the royal city. There he sets free all living creatures, even the cats, and gives everything away. This is what a king ideally, but never actually, does. The ambiguity of the king who gives everything away may be traced back to the Brāhmanas, where it is said that the ideal sacrificer (of whom the epitome is the king) should give everything away and go to heaven immediately; yet the sacrificer is warned not to do this, and he is explicitly told to make certain that he comes back from heaven when he goes there during the sacrifice.33 The king’s tension between renunciation and life in this world is already manifest in these early texts.

Vessantara returns to rule, but to rule as a renouncing king and perhaps not for very long. When he dies, he goes to a heaven like Hariścandra’s, not a permanent release but a temporary way station full of superearthly pleasures. The ambiguity of this ending is retained in a Hindu retelling of the tale of Vessantara.34 There the king is named Tārāvaloka, and he has twin sons named Rāma and Lakṣmaṇa, but he is still married to a woman named Maddī (Madrī, in the Sanskrit). When Tārāvaloka has been reunited with his children, he becomes king not of his own human kingdom but of the realm of the Vidyādharas, or celestial magicians, and he flies through the air to their land and learns all of their secret knowledge by the grace of the goddess Lakṣmī. This ending, with the hero flying away in the arms of a female magician, comes straight from the Hindu tales of dream adventures; it celebrates the worldly, saṃsāra-oriented values of that genre. But suddenly, at the end, the story is given a mokṣa-based (or Buddhist) twist: Tarāvaloka becomes disgusted with all worldly pleasures and retires to the forest as an ascetic.

Vessantara and Tarāvaloka do not live among Untouchables, as the kings in the Hindu paradigm do, because for the Buddhists, who are outside the caste system, the Untouchables cannot symbolize human reversals or royal sufferings. Yet suffering of one sort or another is still the key to the experience of the Buddhist as well as the Hindu kings. Suffering is what alerts us to the insubstantiality of saṃsāra, in part because it makes us want to believe that our pain is unreal, and in part because pain is a useful shock mechanism to awaken someone from a dream. A myth of cosmogony narrated in the Yogavāsiṣṭtha expresses this power of suffering:

When Brahmā made the universe, he created, in the land of India, all the people who are plagued by disease and pain. When Brahmā saw their misery [duḥkha], he felt pity, as a father feels pity for the unhappiness of his son. Realizing that there was no end to their misery except through nirvāṇa and release from rebirth, Brahmā created Vasiṣṭha and said to him, “Come, my son. For just a moment I will cause your mind, fickle as a monkey, to be engulfed in ignorance.” As soon as he cursed Vasiṣṭha in this way, Vasiṣṭha forgot everything he knew; he was tortured by misery, sorrow, and confusion. Then he asked Brahmā, “My lord, how did such misery enter into worldly existence [saṃsāra], and how can a man get rid of it?” And in answer to Vasiṣṭha’s question, Brahmā taught him the supreme knowledge. Then he restored Vasiṣṭha to his natural condition and said, “I used a curse to make you ignorant, and as a result of your ignorance you began to ask questions, my son. That was why you wanted to have this essential knowledge in order to help all people.”35

Until Vasiṣṭha experiences suffering, he lacks the impetus to seek knowledge; the experience of the illusion of ignorance is necessary before one can understand the illusion of reality. The particular emphasis on ignorance (avidyā, or Pali avijjā) as the root of suffering, together with the exhortation to help all people, are clues to the Buddhist sympathies of this story.

The story of Lavaṇa involves just such an enlightening “curse,” one that occurs in a brief moment (muhūrtam) but has effects that last for a lifetime. The key to Lavaṇa’s enlightenment lies, moreover, not merely in his own suffering but in his exposure to other people who are by definition beyond the pale of comfortable Hindu society. These people are epitomized by the Untouchables, but other sorts of outcastes are assimilated to them, principally demons and women. Thus the king is enlightened in two related ways: by his own suffering and by being exposed to people outside his court; that is, he is forced to learn from people who are entirely different from him.

Ironically, this very theme—of learning from people who are “outside” (bahiṣkṛta)—comes to the author of the Yogavāsiṣṭha from people who are outside his tradition, the Buddhists. Another unmistakable hint of this heritage may be seen in the use of nirvāṇa (“extinction”) as the term for release in the myth of Vasiṣṭha’s suffering, for this is the Buddhist term for what a Hindu would normally refer to as mokṣa. So, too, duḥkha (suffering) is the key to Buddhist formulations of the nature and origins of the world. But a far more extensive Buddhist influence in narrative themes (as well as in the philosophical discussion of illusion) pervades the Yogavāsiṣṭtha as a whole.

For in early Buddhism as well as in Hinduism we find the paradigm of the king who is enlightened by suffering, and in light of the heavy Buddhist influence on the extreme form of the doctrine of illusion (and hence upon the philosophy of the Yogavāsiṣṭtha), the borrowing of this Buddhist theme should not surprise us. Looming behind Rāma’s experience of suffering—as behind that of Lavaṇa, whose debasement among the Untouchables is so graphically described—is the story of the Buddha, Gautama Śākyamuni, a king who never left his palace until he was a grown man and who did so then to discover the existence of suffering as the basis of enlightenment.

This episode is retold in Buddhist texts over many centuries, and the variations tell us much about the shifting spectrum of Buddhist concepts of reality and illusion. In one set of texts, within the Pali canon (and hence probably, but not certainly, the oldest version of the story), the future Buddha or Bodhisattva simply thinks about the three forms of suffering: old age, disease, and death. Indeed, he merely thinks about someone else thinking about these things. Gautama tells his own story in the first person:

Monks, I was delicately nurtured. . . . I had three palaces. . . . In the four months of the rains . . . I came not down from my palace. To me . . . this thought occurred: surely one of the uneducated manyfolk, though himself subject to old age and decay, not having passed beyond old age and decay, when he sees another broken down with age, is troubled, ashamed, disgusted, forgetful that he himself is such a one. . . . When he sees another person diseased . . . [and] when he sees another person subject to death . . . .36

In another set of Pali texts, Gautama does not merely think about someone seeing an old man, a sick man, and a dead man; he himself actually sees such men:

When the Bodhisattva was fourteen years old, he drove out of the eastern gate of the city and happened to see an old man with a white head. He asked his charioteer, “What is that man?” “It is an old man.” . . . Some time later, he went out of the southern gate of the city and happened to see a sick man. . . . Some time later, he went out of the western gate of the city and happened to see a dead man. And as he returned home in his chariot, he happened to see a holy man, a renouncer.37

This text not only depicts the three men as physically real rather than imagined by Gautama; it also adds a fourth man, also physically real, who represents the answer to the question posed by the first three: the holy man, the transcendent fourth, who counterbalances the worldly triad.

A Tibetan text follows the pattern of this last version, with one significant variation: the Bodhisattva sees a (real) old man, sick man, and dead man, but the fourth is different:

And yet on another occasion he met a deva [god] of the pure abode who had assumed the appearance of a shaved and shorn mendicant, bearing an alms-bowl and going from door to door. . . .38

Why did a god assume the form of a mendicant? One can imagine several good reasons: the transcendent fourth is of a nature different from the preceding three; the real mendicant—the Buddhist monk—does not yet exist, since the Buddha has yet to invent him. Yet our second text was not troubled by the first objection, and none of the other texts that we will encounter is troubled by the second; for if there were as yet no Buddhist monks in India, there were certainly other kinds of renouncers. A better answer to the question is, I think, supplied by the hypothesis that the Tibetan text has conflated the second version (in which Gautama actually sees the men) and the story as it is told in a number of other texts, beginning with the Pali introduction to the Jātaka, in which the gods take the form of all four of the men. The Bodhisattva goes in his chariot to a park, and at that moment the gods think, “The time for the enlightenment of Prince Siddhattha draws near; we must show him a sign.” They change one of their number into a decrepit old man, visible to no one but Siddhattha. Subsequently the Bodhisattva encounters a diseased man whom the gods had fashioned, a dead man whom the gods had fashioned, and a monk whom the gods had fashioned.39

A Sanskrit version of this episode continues to regard the four men as products of the gods rather than as natural occurrences or thoughts, but the fourth man continues to be distinguished from the other three:

When the gods saw the city as joyful as paradise itself, they made a man worn out by old age in order to incite the son of the king to go forth. . . . He asked the charioteer, “Is this some transformation in the man, or his natural state?” Then the gods deluded [moha] the charioteer’s mind so that he spoke of what he should have kept secret, not seeing the fault [in speaking]. . . . The gods created a man diseased. . . . Then the Bodhisattva began to think about old age, and disease, and death. A man dressed as a monk [bhikṣu] came up to him, unseen by other men, and spoke to him. Then, as the king’s son was watching, he flew up to the sky. For he was a god who had taken that form; he had seen other Buddhas and had come to him to make him remember.40

The charioteer, who answered freely in the first Pali text, now identifies the three men only because the gods have deluded him; yet it is because of this delusion that he speaks the truth instead of lying, as the Bodhisattva’s father would have had him do. And where the gods make the first three men, one of them actually becomes the fourth and speaks to Gautama, which none of the others does. Moreover, though the first three men are visible to the charioteer as well as to the Buddha (and, presumably, to other men as well, as are the “real” men in the other versions), the fourth man is visible only to the future Buddha; he flies up right before the Buddha’s eyes, just as Athena does in the Odyssey when no one but Odysseus knows that she is a god. Why must the gods make the first three men if they behave just like “natural” men (i.e., they are visible to others besides the Buddha, unlike dream images or thoughts)? Because, according to this text, the king had gone to great pains to remove from his son’s path all of the real old, sick, and dead men that he might encounter. Thus the gods have to produce an illusion in order to replace the reality that has been unnaturally distorted, even as they have to delude the charioteer in order to make sure that he will speak the truth.

A final version of this episode further encases the four sights within the framework of other dreams; indeed, the chapter in which the prince encounters the four men is called “Dreams”:

King Śuddhodana, Gautama’s father, had a dream in which he saw his son leaving the palace surrounded by gods, and he saw that he became a wandering religious mendicant, wearing an ochre robe. And so he had three palaces built and stationed five hundred men on the stairs so that the prince could not leave without being noticed. When the prince announced his intention to go out to the pleasure garden, the king stationed his men all along the prince’s route; but at the very instant when the Bodhisattva [Gautama] came out of the eastern gate of the city, by the mental power of the Bodhisattva himself there appeared an old man. The Bodhisattva asked his charioteer who the man was, and the charioteer told him about old age. Another time, as the Bodhisattva went out of the southern gate, he saw a sick man, and another time, by the western gate, he saw a dead man. Finally, when he went out of the northern gate, the gods used Gautama’s own mental powers to fashion on the road the image of a holy man. When the Bodhisattva saw him, he asked his charioteer about him, and the charioteer replied, “That is a man called a monk [bhikṣu].”41

Gautama’s father, the king, has a predictive dream that he rightly interprets and tries to avert. Yet the Bodhisattva manages to escape all the same, and the dream comes true. By his own mental powers (anubhāva: authority, belief, intention) he produces the illusion of a man he has never seen and does not understand (for he asks the charioteer about him). Then he “sees” (a verb that can indicate the perception of a dream as well as a waking reality) a sick man and a dead man. The fourth man, the monk, is the ambiguous pivot: his ochre robe, always an evil omen in a Hindu dream, is a symbol of evil for King Suddhodana; but for the Bodhisattva, and for the Buddhist reader, it takes on a new meaning as the emblem of the future order that Gautama is about to create. This fourth man appears first in the king’s dream and then outside; he is visible to the charioteer, just as the other three men were. All four images are thus accessible to public corroboration, whether they are naturally there to be seen or are made by the gods or imagined by the Bodhisattva.

This last text goes on to describe other dreams that occur when the king continues to fight against the omens. This episode is also a part of our very first Pali text (in which the Buddha merely thinks of the three men), which tells it thus:

When the Tathāgata [Gautama] was not yet wholly awakened but was awakening, he had five great dreams. He dreamt that the world was his bed of state, that the mountain Himalaya was his pillow; this meant that he was becoming fully awakened. Then he dreamt that grass came out of his navel and grew till it reached the clouds; this meant that he would proclaim the noble doctrine of the eightfold path as far as gods and men exist. He dreamt that white worms with black heads crept up over his feet to his knees; this meant that white-robed householders would find life-long refuge in him. He dreamt that four birds of various colors fell at his feet and became pure white; the four classes of society [varṇas] would take up renunciation and find release. And, finally, he dreamt that he walked on a great mountain of shit but wasn’t dirtied by it; this meant that he would receive robes, alms, lodgings, and medicine but would not be attached to them.42

We have encountered several of these dreams in traditional Hindu dream books; indeed, the Buddhist commentator on this passage shows his awareness of this heritage when he rehearses the four causes of dreams: somatic disturbances due to bile, etc., will produce dreams such as falling from a precipice or flying or being chased by a beast or a robber; other dreams are caused by previous events, by possession by the gods (sometimes for one’s good, sometimes otherwise), and as premonitions (the Buddha’s dreams were of this fourth, premonitory, type). There are also a few personal or universal themes. But all of these motifs, personal or traditional, are given decidedly untraditional (i.e., non-Hindu) Buddhist glosses. The archaic image of the magic plant growing out of the navel (which appears in Hinduism as the lotus growing out of Viṣṇu’s navel) becomes the doctrine of the eightfold path; the worms that surge over Gautama’s feet are merely householders; the falling birds, so pregnant with meaning for ancient Indians as well as ancient Greeks, now become (by virtue of a pun on the word varṇa, “color” or “class”) symbols of the classes of society; and the mountain of shit, which looms so ominously in Hindu dreams, is reduced to being a symbol of the material goods that Buddhist monks had perforce to receive from Buddhist lay people—a problem that is indeed highly charged for Buddhists, but culturally rather than personally charged.

In the Sanskrit text that tells of King Śuddhodana’s dream, the dream that the Bodhisattva himself dreamed is also related, in terms somewhat different from those of the Pali canon:

He saw enormous hands and feet waving about in the waters of the four oceans; the whole earth became a magnificent bed, and Mount Meru a crown. He saw the shadows of darkness clearing away, and a great umbrella, which came out of the earth to shed light on the triple world and dispel its suffering. Four black-and-white animals licked their feet; birds of four colors came and became one color. He climbed a great mountain of disgusting shit, but he wasn’t soiled by it. He saw a river in spate, carrying along millions of creatures in its current, and he became a boat and carried them to the far bank. He saw many people suffering from diseases, and he became a doctor and gave them medicine and saved them all. Then he sat on Mount Meru, his throne, and he saw his disciples and the gods bowing low before him. He saw victory in battle, and a joyous cry from the gods in the sky.43

Some of the more dreamlike images from the Pali-canon version are omitted (the grass from the navel, the worms on the feet). The more conventional, culturally accessible images are retained and expanded. As a result of this editing, and perhaps also as a result of the assumption that the audience would be familiar with the Pali story, the explicit commentary is omitted; the secondary elaboration is subtly integrated into the dream itself.

This Sanskrit text had added, we saw, as a prelude to Gautama’s own dream, a description of his father’s dream, which consisted of a fairly simple, entirely realistic vision of the Bodhisattva’s renunciation. It also added, as a kind of postlude to the half-illusory experience of the four men (and as a prelude to Gautama’s own dream, which comes at the very end), the dream that Gautama’s wife had on the eve of his awakening. This dream is more elaborate and surreal than Gautama’s dream, but it, too, echoes many traditional Indian dream motifs: