Ontology in Narrative: More Tales from the Yogavāsiṣṭha

When we ask our own questions of Indian tales of dreams, we may try to concentrate on the epistemology of the problem—the question of how people think about the world—only to find ourselves drawn back over and over again to the ontology of the problem—the question of what the world really is. That is because the two problems are in fact a single problem; epistemology is the shadow double of ontology. The Indian texts treat it as a single problem from the very start; they ask how our minds affect the world and how the world exists in our minds. They take the quandary of nested dreams (the question of whether we have awakened from the last of a series of dreams) and twist it in upon itself to present a more baffling problem, the enigma of the dreamer dreamt: If we cannot determine whether we are the final dreamer, in the outermost frame, can we determine whether or not we are part of someone else’s dream, part of the dream of the dreamer in the next frame outside ours? Although this question is not directly posed by the myths of Lavaṇa and Gādhi, it is in a sense implicit in them. For if we look at the story from the viewpoint of Lavaṇa, for instance, it is apparent that he might well wonder not only whether he has finished waking up from a series of dreams (first that he is an Untouchable and now that he is a king), but whether he is not the king in the dream of a Brahmin who dreamt he was a king. If we are not sure that we are in the outermost frame of a nested dream, we cannot be sure that we are the final dreamer.

One myth in the Yogavāsiṣṭha tackles this dilemma more directly and powerfully than any text I know. This myth builds our minds—the minds of us, the audience, as we listen—into the story, and it does so by drawing us deeper and deeper into the tale within the tale. In this way it embodies, as well as talks about, the paradox of the author who is a character in someone else’s story, the dreamer who is a figure in someone else’s dream.

The Monk Who Met the People in His Dream

Once upon a time there was a monk who was inclined to imagine things rather a lot. He would meditate and study all the time, and fast for days on end. One day, this fancy came to him: “Just for fun, I will experience what happens to ordinary people.” As soon as he had this idea, his thought somehow took the form of another man, and that man wished for an identity and a name, even though he was just made of thought. And by pure accident, as when a crow happens to be under a tree when a palm fruit falls from it and hits him, he thought, “I am Jīvaṭa.” This dream man, Jīvaṭa, enjoyed himself for a long time in a town made in a dream. There he drank too much and fell into a heavy sleep, and in his dream he saw a Brahmin who read all day long. One day, that Brahmin fell asleep, worn out from the day’s work, but those daily activities were still alive within him, like a tree inside a seed, and so he saw himself, in a dream, as a prince. One day that prince fell asleep after a heavy meal, and in his dream he saw himself as a king who ruled many lands and indulged in every sort of luxury. One day that king fell asleep, having gorged himself on his every desire, and in his dream he saw himself as a celestial woman. That woman fell into a deep sleep in the languor that followed making love, and she saw herself as a doe with darting eyes. That doe one day fell asleep and dreamed that she was a clinging vine, because she had been accustomed to eating vines; for animals dream, too, and they always remember what they have seen and heard.

The vine saw herself as a bee that used to buzz among the vines; the bee fell in love with a lotus in a lotus pond and one day became so intoxicated by the lotus sap he drank that his wits became numb; and just then an elephant came to that pond and trampled the lotus, and the bee, still attached to the lotus, was crushed with it on the elephant’s tusk. As the bee looked at the elephant, he saw himself as an elephant in rut. That elephant in rut fell into a deep pit and became the favorite elephant of a king. One day the elephant was cut to pieces by a sword in battle, and as he went to his final resting place he saw a swarm of bees hovering over the sweet ichor that oozed from his temples, and so the elephant became a bee again. The bee returned to the lotus pond and was trampled under the foot of an elephant, and just then he noticed a goose beside him in the pond, and so he became a goose. That goose moved through other births, other wombs, for a long time, until one day, when he was a goose in a flock of other geese, he realized that, being a goose, he was the same as the swan of Brahmā, the Creator. Just as he had this thought, he was shot by a hunter and he died, and then he was born as the swan of Brahmā.

One day the swan saw the god Rudra, and he thought, with sudden certainty, “I am Rudra.” Immediately that idea was reflected like an image in a mirror, and he took on the form of Rudra. This Rudra indulged in every pleasure that entered his mind, living in the palace of Rudra and attended by Rudra’s servants. But the Rudra that he had become had a special power of knowledge, and in his mind he could see every single one of his former experiences. He was amazed by the hundred dreams he had had, and he said to himself, “How wonderful! This complicated illusion fools everyone; what is unreal seems to be real, like water in a desert that turns out to be a mirage. I am something that can be thought, and I have been thought. There happened to be a soul that, by chance, became a monk in some universe, and he experienced what he had been thinking about: he became Jīvaṭa. But because Jīvaṭa admired Brahmins, he saw himself as a Brahmin; and since the Brahmin had thought about princes all the time, he became a prince. And since that prince was inclined to do things in order to run a kingdom, he became a king; and because the king was full of lust, he became a celestial woman. And that fickle woman was so jealous of the beautiful eyes of a doe that she became a doe; and the doe became a vine that she had noticed, and the vine saw herself as a bee that she had observed for a long time, and the bee was trampled under the feet of an elephant that he had seen, and he wandered in and out of a series of rebirths. At the end of the round of a hundred rebirths is Rudra, and I am Rudra, I am he, the one who stands in the flux of rebirths where everyone is fooled by his own mind. For my amusement, I will raise up all those creatures who are my own rebirths, and I will look at them, and by giving them the ability to look at the matter as it really is, I will make them unite into one.”

When Rudra had decided on this, he went to that universe where the monk was sleeping in his monastery, like a corpse. Joining his mind to the monk’s mind, Rudra woke him up; and then the monk realized the error he had made (in believing his life as Jīvaṭa to be real). And when the monk looked at Rudra, who was the monk himself and was also made of Jīvaṭa and the others, he was amazed, though one who was truly enlightened would not have found cause for amazement. Then Rudra and the monk went, the two of them together, to a certain place in a corner of the space of the mind where Jīvaṭa had been reborn, and then they saw him asleep, unconscious, still holding a sword in his hand: the corpse of Jīvaṭa. Joining their minds to his mind, they woke him up, and then, though they were one, they had three forms: Rudra and Jīvaṭa and the monk. Though they were awake, they did not seem to be awake; they were amazed, and yet not amazed, and they stood there in silence for a moment, like images painted in a picture.

Then all three of them went through the sky to the place, echoing in the empty air, where the Brahmin had been reborn, and there they saw the Brahmin in his house, asleep with his wife, the Brahmin lady, clasping him around his neck. They joined their minds to his mind and woke him up, and they all stood there, overcome with amazement. Then they went to the place where the king had been reborn, and they awakened him with their mind, and then they wandered through the other rebirths until they reached the swan of Brahmā. And at that moment they all united together and became Rudra, a hundred Rudras in one.

Then they were all awakened by Rudra, and they all rejoiced and looked upon one another’s rebirths, seeing illusion for what it was. Then Rudra said, “Now go back to your own places and enjoy yourselves there with your families for a while, and then come back to me. And at doomsday, all of us, the bands of creatures who are part of me, will go to the final resting place.” And Rudra vanished, and Jīvaṭa and the Brahmin and the others all went back to their own places with their own families; but after a while they will wear out their bodies and will unite again back in the world of Rudra.1

This story is a highly sophisticated variant of a much-loved Indo-European folk motif, which includes the story of Chicken-Licken (who told Henny-Penny who told Foxy-Loxy . . . that the sky was falling) and The House That Jack Built. The theme also appears in European literature as the motif of “Magic: Man Magically Made to Believe Himself Bishop, Archbishop, and Pope,” otherwise known as Stith Thompson’s Motif D 2041.5.2

We have already encountered a more specifically Indian reflection of this theme in the variant of the Hariścandra story, in which the king dreamed that he was reborn many times as many things. Indeed, like the theme of which the Hariścandra story is an example (the king among the Untouchables), the tale of the chain of rebirths is a kind of set piece in India. A shorter myth, though with a longer chain of rebirths, appears elsewhere in the Yogavāsiṣṭha:

An ascetic named Long Asceticism [Dīrghatapas] died, and his wife committed suicide. One of their two sons, named Puṇya [Merit], was immune to grief, but the other son, named Pāvana [Purifying], was not. To assuage Pāvana’s grief, Puṇya pointed out that, if Pāvana wished to be consistent in his mourning, he must mourn not only for his recently deceased father and mother but for all the parents he had had in his other lives, and Puṇya reeled off the list: Pāvana had been a deer, a goose, a tree, a lion, a fish, a monkey, a prince, a crow, an elephant, a donkey, a dog, a bird, a fig tree, a termite, a rooster, a Brahmin, a partridge, a horse, a Brahmin again, a worm, a fly, a crane, a birch tree, an ant, a scorpion, a tribal hunter [Pulinda], and a bee. Puṇya added that he himself could clearly recall his own births as a parrot, a frog, a sparrow, a Pulinda, a tree, a camel, a lovebird, a king, a tiger, a vulture, a crocodile, a lion, a quail, a king, and the son of a teacher named Śaila. [See plate 12.]3

Difficult as it is to tell when people of another culture are joking or serious, it does seem that there is at least an element of humor in Pāvana’s list. For Hindus were so familiar with the motif of the chain of rebirths that they could poke fun at it, just as they could satirize the theme of the double universe in the Hindi tale of the pot, recounted in chapter three. Whether or not they believe in it, Indians have a joking relationship with illusion. The theme of the dream of the chain of rebirth was mocked by the poet Rājaśekhara in his play Karpūramañjarī. A conversation takes place, at the start of act three, between a love-sick king and his jester.

KING: I am thinking about a vision I saw in my sleep.

JESTER: Tell me about it.

KING: I thought a beautiful girl stood within my field of vision, even within the range of my hand, as I lay on my bed. I grabbed for the end of her sari, but she went away leaving the sari in my hand, and then my sleep vanished too.

JESTER: [Aside] I should think it would! [Aloud] You know, I had a vision last night, too.

KING: What was your vision?

JESTER: I dreamt last night that I fell asleep by the Ganges and was washed away by her waters and absorbed by a cloud.

KING: How amazing!

JESTER: The cloud rained me into the ocean, and the oysters absorbed me and I became an enormous pearl. I was a drop of cloud-water in sixty-four oysters in succession, and finally I became a perfect pearl. All of the oysters were fished out of the water, and a merchant bought me for a hundred thousand pieces of gold.

KING: What a wonderful vision!

JESTER: The merchant had the jeweler drill a hole through me—that hurt a bit—and then I was strung with the other sixty-three pearls to make a necklace priced at a million pieces of gold. The merchant—who was named Sāgaradatta [Gift from the Sea]—went to king Vajrāyudha, in Kanauj, and sold the necklace to him for ten million pieces of gold. The king put the necklace on the neck of his favorite wife, and at midnight he began to make love to her. But her breasts were so big and hard that I was hurt [by the pressure of the king against her body], and so I awoke.

KING: You knew that my vision, in which I met the woman who is as dear to me as my very breath of life, was not real [na satyam], and so you tried to drive it away with your countervision.4

The king dreams a classic erotic dream and wakes up just as he strips the woman, holding her dress in her hand—but the dress is not there when he wakes up. His dream is not real; the king acknowledges this. The jester then interprets the king’s dream as a monk would do, and he brings the king down to earth by presenting him with a fun-house-mirror distortion of a dream of rebirth. He tells first of a dream within a dream (for he dreams that he falls asleep) and then of a dream of transmigration. The king keeps expressing amazement, as people do when they are told of dreams that come true; but apparently he is just as amazed at the high price brought by the pearl as at the fact that the jester became a pearl at all. (The term for pearl, muktā, may also be a pun on mukta, the released soul or soul that has reached mokṣa.) The theme of the pain or suffering that causes awakening or enlightenment appears here as a satire on the moment of awakening from the orgasmic dream: the sexual climax (not of the jester/pearl, but of the king of Kanauj) causes pain, not pleasure; the pearl is squashed between the woman’s breasts. Thus the jester mocks both the theme of suffering (for it also hurts him when a hole is drilled in the pearl) and the theme of the chain of rebirths, in order to show the king how ridiculous it is to pay any attention to your dreams.

But the story of the monk who dreamed of the hundred Rudras differs from the usual varieties of this theme in at least two important ways: instead of piling up barnyard animals or clergymen, it piles up nested figments of the imagination. And instead of piling them up in a line, it piles them up in a rope that snakes back in upon itself.

The story of the monk’s dream, like all of the stories in the Yogavāsiṣṭha, is told by Vasiṣṭha to Rāma, and Rāma asks Vasiṣṭha a number of questions. These questions elicit both explicit discussions of the metaphysical implications of the text and supplementary episodes that explain some of the events in the basic story (just as the tale of Lavaṇa’s imaginary consecration helped to explain his experience among the Untouchables). For example:

Rāma said, “How did Jīvaṭa and the Brahmin and the other forms that the monk imagined become real? How can an object of the imagination be real?” Vasiṣṭha said, “The reality of the imagination is only partial; do not take it for something entirely real. What isn’t there, isn’t there. Yet the true nature of what is seen in a dream or visualized by the imagination exists at all times. Everything exists in a corner of the mind. . . . A person sees a dream as if it were a solid, hard thing, and then from that dream he falls back into another dream, and from that into yet another dream, and each time it appears hard and solid.”5

Elsewhere Vasiṣṭha gives a different explanation of the monk’s dream:

Then Rāma asked, “What became of the hundred Rudras? Were they all Rudras, or weren’t they? And how could a hundred minds be made from a single mind? How could they be made by that Rudra who was himself made in someone’s dream?” Vasiṣṭha replied, “The monk visualized a hundred bodies in a hundred dreams. But all those forms in the dream were, in fact, Rudra, a hundredfold Rudra. For those who have removed the veil from reality can imagine things so precisely that those mental perceptions are actually experienced. And because of the omnipresence of the universal soul, something that is experienced in a particular way and in a particular place by a mind with true understanding will actually come into existence in that way at that very place.”6

On the one hand, the text seems to say, all the things that we think are real are only parts of a dream—our dream, or someone else’s dream. On the other hand, there is a reality in dreams, for the things that we imagine or dream are reflections of some reality, which does exist at all times and in all places and happens to get into our minds “by accident,” like the accident that makes the monk think that he is Jīvaṭa. In this view, mental images are reflections of an underlying reality; there was a Jīvaṭa, and the monk dreamt of him; it remained then only for Rudra to find the Jïvaṭa that the monk had dreamt of and to introduce them to each other. Though the monk dreamt of a hundred people, those people did exist as a part of the god Rudra. Yet the text also implies that the monk had the power to dream them into existence from his mind upward, all the way up the line from the monk to the swan to Rudra; and Rudra had the power to think them all into existence as part of himself, from his mind downward, all the way from the swan to the monk. The text tells us that all the people in the dream are part of Rudra, physically; and it also says that they are part of his mind, his dream. These are not contradictions. For Rudra to think of something is for him both to make it exist and to find that it has always existed as part of him. These two kinds of creation—making and finding—are the same, for in both cases the mind—or the Godhead—imposes its idea on the spirit/matter dough of reality, cutting it up as with a cookie-cutter, now into stars, now into hearts, now into elephants, now into swans. It makes them, and it finds them already there, like a bricoleur, who makes new forms out of objets trouvés.

Rudra’s mind is the mold that stamps out the images, all of which derive from him. He stamps this mold on the spirit/matter continuum of the universe in such a way that it breaks up into the separate (or, rather, apparently separate) consciousnesses of all of us. The images that he sketches in our minds were already there—in the continuum, and in our minds; but we cannot know them until his mind touches ours, until he “joins his mind to [our] mind.” Finally, when we really know Rudra, the images vanish, and the continuum is seen as it really is, devoid of the fragments of individual figures in the landscape. Then the background becomes the foreground.

Despite Rudra’s extraordinary ontological status, his actual mental processes are flawed like those of even the best of his dream creatures, the monk. The monk, who unknowingly imitates Rudra’s “play” (līlā), begins dispassionately enough; but as soon as he imagines a person with passions (the earthy Jīvaṭa), he is caught up in those passions himself and forced to follow the game into realms he had not intended to explore. So, too, Rudra is caught up in his own sport; he is “amazed” to see what creatures people the brave new world of his imagination. Though he is the mold that cuts the forms, those forms also create themselves, beyond his control, once the process is set in motion. Like the monk, Rudra discovers that creation inevitably leads to imperfection, to the self-perpetuating desire to go on creating. Like the monk, Rudra indulges his frivolity, his creative urge. Not even Rudra can remain deaf to the songs of the sirens he imagines. Someone else is pulling his strings.

For pure play does not remain pure for long. Rudra begins to act “for the sake of play/sport/amusement/fun,” or “for the sheer hell of it” (līlārtham)—a term we might also translate as “art for art’s sake.” This same art is implicit in the term māyā, derived from the Sanskrit verb “to make.” Māyā is what Rudra makes (or finds) when he imagines the universe; māyā is his art. Yet māyā is often associated with evil in Indian texts, for it is the trick of the mind that causes us to become, literally, deadly serious about what begins in a spirit of play. Māyā is what makes it possible for Rudra to use his art, but it is also what blinds us to that art. Māyā is what makes us dream, and die.

The Yogavāsiṣṭha tells us of other Hindu gods who have had powers like Rudra’s:

While Viṣṇu remained asleep in the ocean of milk, he was born as a man on earth; while Indra remains on his throne in heaven, he goes down to earth to receive the sacrifice; though Kṛṣṇa was only one person, he became a thousand for the many kings who are his devotees, and for the thousands of women who were his mistresses, by indulging in the game [līlā] of partial incarnation. In this same way, through the power of the understanding of Rudra, Jīvaṭa and the Brahmin and all the others who had been imagined by the monk went to whatever city they had imagined.7

The imaginings of gods are a thousandfold more powerful even than the imaginings of monks. And Rudra in this text is the supreme god.

Rudra is the warp upon which we all weave our dreams; he is the fluid in which we all flow together like the particles in a suspension. He is the place where we all meet in our dreams, the infinity where our parallel lives converge. Rudra is the dream ether that we saw in chapter two, the medium for the rêve à deux in psychoanalysis. The text tells us that the lives that the monk imagined could not see one another, living as they did in separate universes, except through the knowledge of Rudra.8 This last phrase is, I think, purposely ambiguous. It means that only people who know Rudra—in particular, who know that they are Rudra—can meet the people in their dreams or meet the people that they were in their former lives and will be in their future lives. But it also means that only through the fact that Rudra knows them can they hope to bridge the gap between the apparently separate souls; Rudra will show them that they are one another because they are he. For though, as Rīma points out, Rudra is merely a character in someone’s dream—the monk’s dream at first, the swan’s dream at last9—he is also the dreamer of all dreams, including the dream of the one who dreams him, the dream of the monk. Thus, when the text says that Jīvaṭa lives in a universe in a corner of the mind,10 the immediate meaning is that it is a corner of the monk’s mind. But as the tale unfolds, we come to understand that the monk himself exists only in the corner of another mind: Rudra’s mind. Moreover, where the monk merely dreams of Rudra, Rudra produces the monk in a more direct fashion: the monk is a partial incarnation of Rudra, an atom flowing in the veins of Rudra. Rudra is “made of” Jīvaṭa and the others, we are told.

Do the people in the monk’s dream exist for just the one episode that Vasiṣṭha tells us about, which occupies perhaps a few months of an adult life, and do they then suddenly vanish when the monk wakes up or dies? Or do they live entire lives, from birth to death, of which the monk witnesses only a brief fragment? Both situations are possible at once, according to this text, for we can find outside ourselves the things that we imagine inside our heads; they exist before we think of them, but we bring them into existence by thinking of them. This is a story simultaneously about dreams that tune into an already existing reality and about rebirths that create a new reality.

When we reach the point where Rudra begins to retrace his footsteps, he refers to the “flux of rebirth [saṃsāra] in which one is deluded by one’s own mind” and “the various wildernesses of rebirth” through which one has wandered.11 Rudra then goes from one universe to another to find the place where the rebirth of Jīvaṭa, the Brahmin, and so forth had taken place or, even more significantly, had begun; and, at the end, they all wander together in the grounds of the other rebirths. For saṃsāra primarily denotes the physical world in which creatures circulate through their repeated births and deaths.

The figures at the very beginning and the very end of the chain of the monk’s dream—that is, the figures who are directly inside the outer frame formed by the monk and Rudra—are a man named Jīvaṭa and a swan. Jīvaṭa (the only character in the dream who is given a proper name) is a derivative of jīva, the ordinary Sanskrit word for the individual life or the transmigrating soul. The swan12 is an ancient Indian symbol for the soul, and particularly for the returning soul, the transmigrating soul, perhaps because of the natural symbolism of the swan’s seasonal migration. The swan is also a liminal bird, able to live in two worlds, land and water, or matter and spirit. The swan comes to symbolize the memory of past lives, as in a verse from a Sanskrit poem describing the moment when a princess came of age: “When the time came for her to learn, all that she had learned in her former life came back to her, as the rows of swans come back to the Ganges in the autumn.”13 In another myth of the dream of rebirth, King Purañjana is, like Nārada, reborn as a woman. One day he meets a friend from his previous life as a king, who tells him, “Don’t you remember your old friend? You and I, my dear, were two swans who lived together in the lake of the mind until you left me to wander on earth. I created the illusion that made you think you were a man or a woman; our true nature is as two swans.” And when the swan of the mind is awakened by the other swan, he wins back the memory that he had lost.14 Here the swans are explicitly identified with the individual soul and the universal soul and are explicitly said to be one and the same.

In this sense, each of the levels within the monk’s dream is a complete rebirth of a single soul, which goes from Rudra to the monk to Jīvaṭa to the Brahmin, and so on, until it subsides back into Rudra again. This mechanism is clearly at work in the second half of the cycle, when the animals die and are reborn, presumably as young animals that grow up. On the other hand, it appears that the monk transfers his consciousness into an already existing Jīvaṭa, taking up Jīvaṭa’s life in medias res, as it were, and Jīvaṭa joins consciousness with an already existing middle-aged Brahmin, and so forth. This mechanism would explain how all of them continued to exist when the monk awoke and how they were able to meet and talk together when Rudra found them all. Once again, the text says both that the soul makes each new life (from birth to death) and that it finds its new lives (in midstream). There is one single soul, and there are a hundred different souls, and yet they are the same.

We do not see the entire rebirth of each of the characters; none of them is born, and most of them do not die within the story. The monk falls into a deep trance; Jīvaṭa passes out in a drunken stupor; the Brahmin falls asleep after a hard day’s reading; the king and the celestial harlot are exhausted by pleasure; and so forth. These people dream and become what they have habitually dreamt about and are thinking of as they die. The belief that you become what you are thinking of at the moment of death is one that we have encountered in the Telugu story of King Lavaṇa and in the Tibetan Book of the Dead, the express purpose of which is to make the dying man dream the right dream so that he will be reborn in the right way—released, if he is heading for mokṣa, or at least born well, if he is to remain enmeshed in saṃsāra.

Yet, near the end of the chain, some of the animals do seem to die and become what they happen to see at the moment of death: the bee is pulverized on the tusk of an elephant, the elephant is cut to pieces by a sword, the next bee is trampled by another elephant. This elephant’s fate is ambiguous, almost certainly designedly so: he falls into a pit and becomes the favorite elephant of a king. Did he die in the pit and become reborn to an elephant cow in the king’s elephant stables, or did he fall into a trap set by a king to catch a wild elephant, who was then tamed and made into the king’s favorite elephant? We do not know. In any case, these animals experience violent accidents of various sorts. The penultimate transition is explicitly said to be a death: the goose dies, shot by a hunter, and becomes the swan of Brahmā. The swan then experiences the final, and most subtle, transition: as soon as he realizes that he is Rudra, his idea is instantly reflected like an image in a mirror; that is, it is projected from him and becomes a solid figure, or, if you prefer, it becomes reflected in the already existing figure of Rudra himself.15

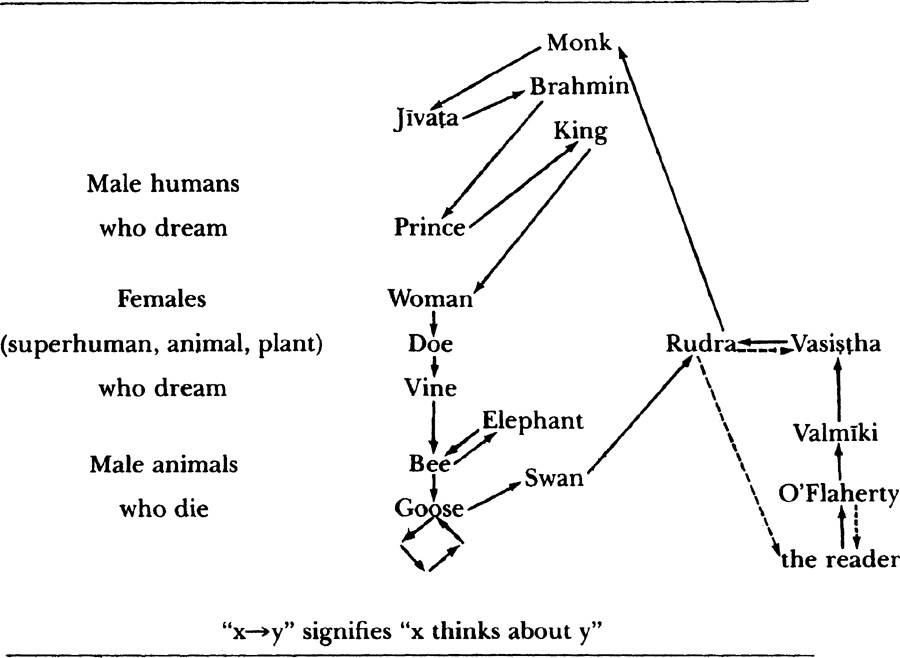

It would appear that the figures are arranged in a kind of hierarchy and that the higher consciousnesses merely dream of a partial rebirth, while the lower ones must actually die—must endure, physically, what the others have experienced only mentally. Setting aside for the moment the monk, as a special case to which we will return, we can see that the characters form three groups, which exhibit decreasing degrees of metaphysical acuity (see figure 5). Jīvaṭa is defined as an ordinary sort of man who loves life; hence he is the logical starting point for an odyssey that is designed to dramatize for ordinary people (the ones who are amazed when the dividing line between dream and reality melts away) the doctrines of illusion and rebirth. He is, moreover, the random sample, the man in the street; the monk thinks of him “by pure chance.”16 Jīvaṭa is the literal embodiment of the transmigrating soul—of Everyman. Paired with Jīvaṭa is the highest human type: the learned Brahmin. In the tale of Gādhi, it is the Brahmin who is the pivotal figure, the dreamer of the outermost dream, but Gādhi experiences the dream helplessly, albeit with understanding. In the tale of the monk’s dream, by contrast, the dreamer (the monk) actively sets out to produce the dream experience and to materialize it; this activity is proper only to perfected monks, not to ordinary Brahmins. Thus the Brahmin and Jīvaṭa are rightly paired as puppets, rather than puppeteers, in this particular episode. (There is, of course, one other Brahmin in the story—Vasiṣṭha; but his role is even more peculiar than that of the monk, and we must postpone for the moment an analysis of his status in the hierarchy.) After the Brahmin come the prince and the king. The royal image is divided into two, of which the first is lower than the second, as was the case with our first pair. These four men roughly (quite roughly) symbolize the four classes (varṇas) of ancient Indian society: the Brahmin, the king, the ordinary citizen (Jīvaṭa), and the servant (the subsidiary feudal lord). It is, I think, significant that there are no Untouchables in this group, for the group represents the system, and Untouchables are out of the system entirely—in another world.

Figure 5. The Dreamer Dreamt

Reproduced by permission of the journal Daedalus from Wendy O’Flaherty, “The Dream Narrative and the Indian Doctrine of Illusion,” Daedalus 111:3 (Summer, 1982): 104.

Below the king is a triad of females, who form the transition from higher to lower consciousness, one semidivine (the celestial woman), one animal (the doe), and one vegetable (the vine). These three figures are still part of the higher echelon who dream rather than die and who become what they have always known, not what they see as they die. The text tells us that animals do dream; so, too, the vine is conscious; she is said to see in herself the embodiment of the loveliness that had been asleep and numb inside the doe for a long time.17 The vine is the incarnation of the metaphor of female beauty (graceful women are always like clinging vines in Sanskrit poetry), even as Jīvaṭa is the embodiment of the soul.

The next quartet, like the first, is divided into two pairs. The elephant and the bee are animals closely associated with violence and eroticism; the wildness of the male elephant in rut carries fairly obvious symbolic meaning, and bees in Indian love poetry are said to form the bowstring of the god of lust and to plunge deep inside the flowers that ooze with sap even as the rutting elephant’s temples ooze with musk. In our text, the bee perishes because his lust for the lotus stupefies him and makes him stick to her even in death.18 The bee and the elephant find violent deaths, over and over again. Then we encounter the last pair, the goose who becomes a swan. Here the hierarchy doubles back on itself; the lowest becomes the highest, and the swan becomes the god, Rudra. The true break comes within this pair: the goose has to be shot dead to become the swan. This is the only explicit death in the story, and it is the most violent transition; by contrast, the swan, in the least violent transition, merely “reflects” itself into Rudra. Once we have reached the swan, we are home. At this point there is no more dreaming; now we begin to unravel all that has been dreamt.

The creatures in the monk’s dream form a pattern that is a masterful combination of order and chance. They are distributed so as to cover the full spectrum of creatures, a point that the text emphasizes by its overall groupings: human males, nonhuman females, and male animals and insects. These groups are, I think, meant to depict a steady general decline in status. Yet within each group are upswings: Jīvaṭa moves up when he becomes a Brahmin or a prince; the bee improves his lot when he becomes an elephant; and the goose becomes a very special swan. Moreover, there are switchbacks (the elephant who relapses into beehood), redundancies (several bees), and, finally, a catchall group of “etceteras” at the end. These irregularities convey the richness and randomness of the process of reincarnation.

This random variation also characterizes the pattern through which all of us will, at some time before the end of infinity, become incarnate as that same monk. Yet, although anything can happen, certain things are more likely to happen; this is how karma skews and orders the chaos of the universe. When the same dream gets into different people’s heads—in this case, the dream of the monk who meets the people in his dreams—there may be minor variations on the theme, minor changes in the manifestations of the archetype: “Again and again these lives revolve in creation like the waves in water, and some [rebirths] are strikingly similar [to what they were beforej, and others are about half the same; some are a little bit the same, some are not very much alike at all, and sometimes they are once again just the same.”19 This flexibility, together with the elements of pure chance and the gravity of karmic tendencies, makes certain coincidences not only possible but probable.

Midway through the round of rebirths, the text moves from dreams to deaths and then begins to talk about them simultaneously, using the image of one to illustrate the other: death is like a dream (or, rather, like an awakening), and a dream or an illusion is experienced as a kind of death. We awaken from ignorance, or from sleep, or from life; the same verb covers all three. In the end, the contrast between creatures who dream and creatures who die is exposed as being as meaningless as the contrast between one transmigrating soul or a hundred dreamt souls.

Our story takes place on three levels of thought that are also three levels of existence. We begin on the most obvious level, with our assumption that dreams are basically different from reality; on this level animals actually change from one form to another form when they die. Mind and matter are distinct; though they may interact and influence each other, they are made of different stuff. On the middle level we encounter the possibility of transforming mind into matter and matter into mind; this is the level where people dream, or think, about assuming another form and so assume it. This middle level has two subdivisions. Truly enlightened people, who understand that mind and matter are not essentially different things, may intentionally use their minds to bring about a change in the forms of matter (or, rather, an apparent change): the monk changes his dreams into living people. But those who are not truly enlightened are forced to undergo what they think are real changes of form, though these changes, too, are merely apparent: the woman is changed into a doe. Finally, on the highest level, we find the undifferentiated substance that is always both mind and matter, the substance that underlies both the apparent changes of material form and the less obvious transmutations that mental forces exert on apparent matter. On this level we realize that nothing ever changes into anything else, that everything was always there all along, and that everything was, for want of a better word, God.

Illusion and rebirth melt together from the very start, in the short poem with which the commentary introduces the whole story: “The story of Jīvaṭa is about the way in which people wrongly believe that they have obtained various bodies; such a wrong perception operated in the mind of the monk as a result of his various karmic memory traces [vāsanās]”20

What are the karmic memory traces? They are the “unconscious memory of past lives.”21 In classical Indian philosophy, they are the bits of experience that adhere to the transmigrating soul and that predispose it to act in one way or another in its new life; they may also be experienced as inexplicable, tantalizing memories, the uneasy aftermath of a dream that has been forgotten by the conscious mind but that continues to haunt the deeper mind—the unconscious mind. The karmic memory traces are “the impressions of anything remaining unconsciously in the mind, the present consciousness of past perceptions; fancy, imagination, idea, notion, false notion, mistake.”22 The second half of this definition indicates how closely karma is associated with illusion: karma is what makes us make mistakes.

It was the karmic memory traces that kept alive the knowledge that returned to the princess when she came of age, like swans returning to the Ganges in autumn; she did not recall her past life, but she recalled what she had known in that life. Our text tells us that after the bee had become an elephant and was then reborn again as a bee, he went back to the same lotus pond where he had previously met with his unfortunate accident, “because people who are not aware of their karmic traces find it hard to give up their bad habits.”23 So, too, when the beautiful woman becomes a doe because she envies the beauty of the doe’s eyes, Rudra remarks, “Alas, the delusion that results from the karmic traces causes such misery among creatures.”24 All of the people in the dream chain are reborn in a particular form because they want something. There is a hunger, unsated in their present lives, that propels them across the barrier of death into a new birth, where this still unfulfilled longing leads them to do what they do.

The cause of rebirth—excessive attachment to the ways of the world—is also the cause of the failure to see through the deception and illusion of the world. The qualities that make the soul cling to rebirth or to illusion are vividly encompassed by a Korean word, won, which has a cluster of meanings, including resentment, ingratitude, regret for lost opportunities, and a knot in the stomach; this state of the soul results from being poorly treated or unappreciated while living or from any of the many situations covered by the rubric “to die screaming.”25 The unwillingness to let go, the inability to leave things unavenged and unfinished, is the drive to rebirth. Though monks and great sages and poets and gods can project themselves into physical bodies whenever they want to, all of us—princes and harlots and bees and professors—helplessly spin, out of our desires, the lives that we have inherited from our former selves. Sooner or later our dreams do become real, whether we want them to or not, whether they are nightmares or wishes that we long to have fulfilled.

Karma is a ready-made classical Hindu explanation for the phenomenon of déjà vu. The karmic traces produce a kind of half-recalled memory from past lives: if you think you have been somewhere before and know that it was not in this life, it was in a preceding life. Each birth makes the others seem unreal, dreamlike, until one gains the knowledge (particularly the knowledge of past, present, and future, which the Hindus call trikālajñāna) to see their reality. The fragmented, imperfect, tantalizing sense of memory, the complete knowledge that hovers just out of reach of the mind’s eye, is interpreted, in India, as the incomplete memory of former lives. These lives are unreal, illusory, not because they are false (in the sense that they never happened at all) but merely because life, like illusion, is by its very nature impermanent.

The sense of déjà vu is surely one of the inspirations of many myths of the dream adventure. A “shock of recognition” appears in the form of déjà vu: we are shocked to recognize, intuitively, something that we feel that we remember—like the dream lover, in chapter two—though we cannot be remembering it, since it has just happened for the first time.26 One is suddenly caught up in a moment so intense that it triggers a sense of memory as well as a sense of experiencing something for the first time. There are many ways to explain this feeling. On the psychological level, it can be seen as an example of retroactive feedback: we dream of something archetypal; then it happens to us in a particular way; then we remember the dream, but now the dream is filled with the details of the actual event, details that now seem to have been in the dream from the very start. We also remember the incident itself differently, investing it with the pattern that we had brought with us from that first dream. On the physiological level, it has been suggested (by Freud, and others) that in a split second we construct a long dream to account for a physical sensation that has just occurred (such as a dream of drowning to accommodate the sensation of wet feet in bed, or a dream of being guillotined in the French Revolution to accommodate a blow on the neck from a collapsing headboard). This overlap between physical and psychical phenomena (or mistaking wet feet for drowning, as one might mistake a rope for a snake) is similar to the overlap explained by the sleep-laboratory analysis that we saw in chapter one: we process physical and mental data in the same way; we process new experiences and memories in the same way. Such double exposures might be triggered by random brain impulses or selected by certain intense emotional events.

And there is a third level on which déjà vu can be explained, after the psychological and the physiological: the theological. Myths like the tale of the monk’s dream affirm that there is some sort of memory that links the past to the present, even over the chasm of death. This force is more basic even than the karmic memory traces themselves: it is the memory built into the divine nature of our mental substance, our mythical DNA. The dream ether holds forever the echoes of all the voices and images that have been transmitted over it. Though we can seldom reach down to touch it, it is always there for us to touch.

A well-known Indian (and Greek) motif associated with this theme is the fish that swallows a ring. We have seen variants of this motif: Hanuman’s shadow was swallowed by a fish, and Pradyumna was brought to Māyāvatī inside a fish (chapter three); the reborn jester became an oyster and was fished out of the sea (chapter five). Usually the fish swallows not the reborn person himself but his symbol, the ring. In tales of this type, the loss of memory may take place not as a result of death and rebirth but merely as the result of a curse within a single life. In “The Recognition of Śakuntalā,” the king seduces a girl in the forest, has a son by her, returns to his palace, and forgets all about her (as the result of a magic curse) until his memory is reawakened: a fish that swallowed the magic ring he had given her to remember him by is caught and served up at the royal table; when the king sees the ring, he remembers the girl in the forest. He realizes then that it has been delusion that made him reject her, or madness, or a dream, or a demon, or fate; and he regards his amnesia as a dream from which he has now awakened, though now he meets her only in his dreams.27 Elements of this story are milder versions of elements in the tale of Lavaṇa: the king’s sojourn in the forest, which is brief in the story of Śakuntalā, is the equivalent of Lavaṇa’s full life in the desert, and Śakuntalā’s rusticity corresponds with the full-fledged Untouchability of Lavaṇa’s consort. But what is particularly relevant here is the implication that each of us, in our present lives, may at any moment be awakened to the memory of another, lost life. The fish symbolizes the persistence of memory, perhaps because the fish’s unblinking, staring eyes suggest a consciousness that never falters for a moment, as ours does when we alternately sleep and wake. Indo-Europeans measure time by the blink of an eye (cf. the German Augenblick, Sanskrit nimeṣa); but for fish, who do not blink, time does not erode memory. The fish is an ancient symbol of liminal consciousness in India: “As a great fish goes along both banks of a river, both the near side and the far side, just so this person [the dreamer] goes along both of these conditions, the condition of sleeping and the condition of waking.”28 And as the fish swims deep in the ocean, it symbolizes deeply submerged memories.

A. K. Ramanujan’s poem “No Amnesiac King” grows out of these themes. The central stanzas are these:

One cannot wait anymore in the back

of one’s mind for that conspiracy

of three fishermen and a palace cook

to bring, dressed in cardamom and clove,

the one well-timed memorable fish,

so one can cut straight with the royal knife

to the ring waiting untarnished in the belly,

and recover at one stroke all lost memory.29

The story of the fish with the ring in his belly is a widely distributed Indo-European motif; Stith Thompson lists it by reference to the Greek tale of the ring of Polycrates.30

In India, the theme of the fish that restores lost memory is enhanced by the theological echoes of Viṣṇu’s avatars: Viṣṇu appears both as a fish who grows from a minnow to a whale and saves Man from the flood, and as a fish or horse-headed aquatic figure who dives down into the depths of the cosmic ocean to bring back the lost Vedas when they have been carried off by a demon.31 The myth of Viṣṇu as the fish is closely tied to the tale of the fish with a ring:

The magic fish [is] the unlikely harbinger of potential good fortune, the symbol of the remote possibility, the unlikely occurrence, the finding of something which had been irretrievably lost, the silvery receptacle of the lost ring, and the reminder to humans that nothing can ever be permanently forgotten, ignored, or submerged in ignorance or non-being.32

Of all the things that we lose, memory is the most precious; it is also the most recoverable, if one knows how to go about it. The myth of the fish and the flood thus extends the motif of the fish with the ring to include not merely the temporary flood, which washes away one individual memory within a lifetime or at death, but the universal flood, which washes everyone away at doomsday. Even then, the myth assures us, Man survives; memory survives.

The problem of memory, linked to the problem of personal identity, is one that has plagued the karma theory from its inception and is particularly a thorn in the side of the Buddhists. Even for the Hindus, there always remains a certain amount of psychological uncertainty33 and cognitive uncertainty34 about one’s previous karma. One cannot know why one has the karmic destiny that one has; moreover, if one cannot feel responsibility for what one has done in a previous life because one cannot remember that life (and therefore, it could be argued, one is not the same person), one cannot feel the justice in being punished for a crime that someone else did (the other, previous self, lost to one’s present memory). One can be told about it and believe it, but that is something else; that is sharing the dream only on the weakest level. But this is not, I think, an insurmountable problem for South Asians. For one thing, the concept of personal identity is in India so fluid that one could very well feel a part of someone else—one’s own ancestor or child or even someone with whom one has had intimate exchanges of food or sex and therefore of “coded substance.”35 If people become a part of strangers in daily intercourse and give parts of themselves in return, the emotional reality of the karmic transfer across the barrier of death and rebirth could be very vivid indeed. The bonds with members of one’s family, one’s own “flesh and blood,” in the past and the future, are even stronger; one’s family, and one’s caste, are one’s self in India. And through the unifying substance of the Godhead, one is linked with the consciousness of all embodied creatures.36

This dissolving of the individual boundaries of the self is what makes it possible for one person to dream for another person, as we saw in chapter one. It also supplies the rebuttal to the challenge of solipsism, as we saw in chapter three: that even if the self is all that exists, the self is not merely one person. Salman Rushdie expresses this concept in his own way:

I am the sum total of everything that went before me, of all I have been seen done, of everything done-to-me. I am everyone everything whose being-in-the-world affected was affected by mine. I am anything that happens after I’ve gone which would not have happened if I had not come. Nor am I particularly exceptional in this matter; each “I,” every one of the now-six-hundred-million-plus of us, contains a similar multitude.37

The Western rebuttal of solipsism consists in distinguishing the self (the ego) from the external world, as Freud and Piaget have taught us to do. But Freud’s ego functions in ways very different from the Hindu self (ātmari) or ego (ahaṃkara). Ahaṃkara, literally “The making of an ‘I,’” is best translated as egoism; it is a mistaken perception, the source of the whole series of errors that cause us to become embroiled in saṃsāra. Once we realize that “I” does not exist, we are free from the most basic of all illusions. It is the Western assurance that the ego is real that drives us to assume that this is the point from which all other frames radiate outward, like the “ego” that anthropologists use to designate the point on their charts from which kinship terms are calculated (ego’s parents, affines, children, etc.). In India as in the West, the ego (ahaṃkara) is the center of the family (or of saṃsāra as epitomized in the family). But the family is the basis of reality in Western psychology and the basis of the illusory material world (saṃsāra) in India. The self (ātmari), by contrast, links one not merely to a certain group of other people but to everyone and, further, to the real world (brahman), which transcends everyone.

For the Buddhists, however, rebirth poses an even more baffling problem, since Buddhists do not believe in the existence of the self (or the Godhead) at all. How can you experience rebirth if there is no self to transmigrate? In addition to the many philosophical gymnastics that Buddhist philosophers have performed, over the ages, to circumvent this problem,38 stories like the myth of the monk’s dream suggest a compromise that might be palatable to some Buddhists: there is no material self, but there is a mental substance that maintains a continuous illusion of self in a kind of cluster of emotional mist that wanders from life to life.

The key to the persistence of memory, and hence the persistence of rebirth, lies in the persistence of emotion. Here, as so often, the Yogavāsiṣṭha tries to do two different things at once, to move in two different directions at the same time. Though it tells us to cut off certain kinds of emotion—lust, in particular—it plays on other emotions throughout, especially amazement, and it exhorts the reader to strive toward a state of enlightenment that is described in many texts as the highest bliss (ānanda), often expressed in sexual terms. As we saw in the mythology of Kṛṣṇa in chapter three, emotion is the key to salvation in bhakti mythology, which does not accept mokṣa as a final goal. But the Yogavāsiṣṭha is not a bhakti text; it is a Vedāntic, mokṣa-oriented text. It asks us to replace the wrong emotions with the right emotions, the wrong sort of lust with the right sort of ecstasy. It simultaneously delights and chastises us; it moves us and stirs us up with its stories, but its goal is to still us and quiet us with the peace (śānti) that comes at the end of a great religious text. The emotion is in the story; the peace is in the commentary.39

Gādhi’s detachment, colored though it is by amazement, pulls him out of the story and makes him an observer, alongside Rāma and Vasiṣṭha and ourselves. Lavaṇa’s helpless involvement is more like our own involvement in the dramas of our own lives. The monk begins the story detached from emotion and firmly (as he thinks) perched on the frame of the story; he is drawn into the vortex and made to experience, rather than merely to think about, his ontological quandary.

The Yogavāsiṣṭha exhorts us to cut off emotion so that we can cut off delusion. Here (as in classical Buddhism and Vedānta) the focal point is hatred of women. Rāma regards women as destruction and cannot be tempted by lovely women; old age is like a worn-out old harlot; longing is a crazy mare that wanders about out of control, like a lecherous old woman who runs in vain after one man and then another and another.40 Both Gādhi and Lavaṇa must abandon the women with whom they have contact in the pivotal episodes of both myths, for they must break the spell of the illusion, a spell made of emotional attachment. Gādhi in his original, waking life does not even know what a woman looks like. The descriptions of his marriage to the Untouchable woman are sensuous: she has breasts like clusters of blossoms, limbs as graceful as young sprouts; he awakens her desire for the first time and lies with her on beds of flowers. But later, when he returns to the Untouchable village, he is full of shame and disgust when he remembers how he embraced her on a bloody lion skin when he was drunk on wine spiked with the aphrodisiac made from the musk of elephants in rut.41 The dream values saṃsāra, but Gādhi’s waking life is devoted to mokṣa.

A man in the grip of illusion and emotion will be the victim of other people’s māyā (as Lavaṇa was overwhelmed by the image projected by the Untouchable Katañja), and, insofar as everyone projects the images of his own emotions, he will project dangerous realities on others (as Lavaṇa projects his own image on the Untouchables). The Yogavāsiṣṭha tells a vivid tale about the power of lust to project material images:

Once upon a time there was a king named Indradyumna, whose wife, named Ahalyā, had heard the story of the seduction of Ahalyā, wife of the sage Gautama, by Indra, king of the gods. Now, in that city there lived a pimp named Indra, and because of all the stories of Indra and Ahalyā, the queen Ahalyā fell passionately in love with the pimp Indra, sent for him, and made love with him night after night. The king found out about the affair and had the couple tortured: they were thrown into cold water in winter, placed on a heated iron pan, tied to the feet of elephants, whipped, and tortured over and over with everything the king could devise, but they merely laughed, delighting in each other. Indra said to the king, “Your punishments do not bother us, for the universe is made of my beloved, and she thinks the universe is made of me.” Infuriated, the king commanded a sage to curse them, but the lovers merely said, “You are foolish to waste your powers by cursing us, for though our bodies may be destroyed, our inner forms will be unhurt.” As they fell to the ground because of the curse, they were reborn as deer, still firmly attached to their illicit passion, and then as birds, and then as a Brahmin married couple. And because of their karmic impressions and memories and their delusion, they were always reborn as a married couple, for their love was real [akṛtrima]”42

The love of Ahalyā the queen and Indra the pimp is, at the start, an imitation of another, more classical, story: the archetypal adultery of Indra, the king of the gods, and Ahalyā, the wife of Gautama.43 The text does not, however, romanticize the queen and the pimp; it merely demonstrates how their passions kept them together despite all opposition. It may or may not be a good thing to be reborn over and over again, helplessly in love; but clearly the lovers think it is a very good thing indeed (as did King Lavaṇa and his Untouchable wife in the Telugu variant of the tale). People do get what they want; that is what karma is all about. The force of Yaśodā’s maternal love gives her a god who is her child, while Mārkaṇḍeya gets a god who is a father. Sages, too, get what they want; the lustful Nārada is vividly contrasted with the detached Vasiṣṭha, while Viśvāmitra hovers liminally between them.

Lust and suffering represent the two ends of the emotional spectrum in India, a spectrum that is then itself set in opposition to the pole of detachment. Just as lust may draw the unwary man into an illusion, so suffering may draw the receptive man out of one. The unpleasantness of life among the Untouchables is the turning point for both Lavaṇa the king and the Brahmin Gādhi. At first this suffering is what makes their lives seem so very real to them; but when the suffering becomes intolerable, with the experience of the death of a son or the disgrace of dethronement, the recording needle leaps right off the paper; then Lavaṇa and Gādhi wake up and say, “It was only a dream.” So, too, it is suffering that first draws us into the story, makes us read on, and makes the story real to us; but it is also suffering that makes us finally look up from the page: “Only when we want to resist the pull of the illusion, when what we read becomes too unpleasant, we . . . tell ourselves that after all we need not submit to words on paper.”44 Only when we fear that the hero will not survive do we say to ourselves, “It’s only a story, after all.” The reader’s conscious suspension of disbelief is quite different from Lavaṇa’s unwitting immersion in a dream. Yet the two awakenings are similar enough to explain each other in ways that we will explore in chapter six and the Conclusion.

Emotion is what drives karma forward; it is what causes us to be reborn. We have seen the close connection between dreams and rebirth; it is therefore not surprising to learn that, according to the Upaniṣads, emotion is also what causes us to dream: dreamless sleep occurs when someone has no desires whatsoever and therefore sees no dream whatsoever.45 It is emotion that makes us want to see things when they are not there, emotion that makes us project our wishes onto material reality. A vivid instance of the emotional power of illusion—or, more precisely, of mistakes—occurs in the Yogavāsiṣṭha during a famine, when people and animals driven to the extremities of hunger, thirst, and fear fall prey to ludicrous misperceptions: “Buffaloes plunged into the ‘water’ that was a mere shining mirage of specks of light; people devoured scraps of hardwood trees in the mistaken apprehension that they were flesh, and fragments of forest stones that they thought were cakes; people ate their own blood-smeared fingers in their frenzy at the smell of flesh.”46

The Yogavāsiṣṭha also uses emotion to explain the distortions of time that take place in dreams and trances. Playing on the well-known phenomenon of the expansion and contraction of waking time—time drags when we are unhappy and flies when we are happy—the Yogavāsiṣṭha demonstrates how mental time drags while physical time flies. That is, dream time is long compared with waking time (a long dream adventure takes place while less than a single night elapses), and yogic time is even longer than dream time (many centuries pass for the yogin’s mind, while only a few days pass for his body; hundreds of years pass during the monk’s twenty-one-day meditation). Both dream time and yogic time are contrasted with physical, emotional, passionate time, in which, as the text insists over and over again, the whole night passes in what seems like just a minute, and many years pass like a single day. Sensuality shrinks time and erodes life; we awaken from the dream of lust to find that we have become old. But we awaken from the dream of enlightenment to find that we never aged at all.

The contraction and expansion of time under the influence of emotion is manifest in other ways that are relevant to the problem of dreams and narratives. It is often said, in the Epics and Purāṇas, that listening to a good story well told makes the whole night pass as if it were a single moment.47 The passion involved in hearing a good story makes time pass quickly, like the passion involved in making love all night, rather than making it pass slowly, as it would in a night spent dreaming. One might have thought that the link between stories and dreams would be closer than the link between stories and love-making—that stories would expand time rather than contract it. But stories and love-making are often connected. In the story of the two Līlās, in chapter three, the king and his queens find equal pleasure in making love and in telling stories of their former lives, and traditions such as the one surrounding Scheherezade and her thousand and one stories demonstrate that women (as well as men) may use stories as a substitute for sex. This ambiguous quality of stories, linked to dreams on the one hand and sex on the other, may also be seen in the ambiguity of the orgasmic dream: to the extent that it is a sexual experience, it shrinks time, but to the extent that it is a dream, it expands time. Indeed, according to Śankara, all dreams are ambiguous in this respect: some make time pass faster, and some make time pass slower.48 Perhaps yogic dreams make time pass slower, while orgasmic dreams make time pass faster. Perhaps, too, philosophical stories (like the Yogavāsiṣṭha) make time pass slower, while adventure stories (like the Rāmāyaṇa) make time pass faster. Perhaps good stories shrink time, while bad stories stretch time. Happiness is quick; sadness, slow. It is emotion and content, rather than form or genre, that primarily determine the direction in which time will be distorted.

A vivid example of the manner in which lust shrinks time may be seen in the tale of King Yayāti. Yayāti succeeded in obtaining youth after he had become old, in order to satisfy his lust for his young wife; when he fell from heaven, he was suspended for a while between heaven and earth, like Triśanku.49 He then resolved not to strive for heaven but to make heaven on earth, and he managed to remain physically young despite his years, like Dorian Grey, until one day Kāma himself and the Gandharvas and celestial nymphs and Old Age incarnate appeared to Yayāti as dancers and singers. They deluded him, and, when the dance was over and the dancers had gone away, the king had become an old man.50 It was Yayāti’s religious virtue that kept him young, against the grain of normal time; and it was his lust that snapped the thread and brought him back into the sway of time once more.

We have seen that the Indian map of the cosmos is as much a diagram of time as it is of space, that the infinity that it attempts to describe extends in the fourth dimension as much as in the first three. If everything changes constantly (as the Buddhists teach us), then change is the only thing that never changes; time is all that is real. The regressive twist that we will soon see in the universe is also a flashback in time. Déjà vu tells us that memory can work into the future as well as into the past; the Indian sage, like Lewis Carroll’s White Queen, has a memory that “works both ways”: “It’s a poor sort of memory that only works backwards,” the Queen remarks.51 Contrariwise, as Salman Rushdie points out, “No people whose word for ‘yesterday’ is the same as their word for ‘tomorrow’ can be said to have a firm grip on time.”52 (The Hindi word kal, literally “time,” designates either yesterday or tomorrow, depending on context.) It all depends on what sort of time one wishes to grip.

The Indian rāga, a traditional musical theme with infinite possibilities of individual variation, is another example of a self-referential cultural form. A rāga does not usually end at all; people wander in and out of it and fade away on the periphery, like the World-non-World mountain that flickers in and out of the material world. The rāga never ends; but the musicians, sooner or later, stop playing it; the audience dozes off or goes home. Since the end of each variation is the beginning of the next, it does not really matter where you leave off or where you begin again. The rāga as it exists in sound—when it is played—expresses the paradox of time that circles back on itself.53

Karma is a memory that works both ways: emotions in the present carry us back into the past and project us into the future. The sage who is free of emotion is free of time; this is the express goal of yoga. The mind can also project us sideways through time in the present; this is what allows Lavaṇa to be in two places at the same time. Time is the key to what appear to be spatial paradoxes in the Yogavāsiṣṭha.

The relevance of the doctrine of karma to the study of the mythology of dreams needs no further belaboring. The central metaphor of the dream adventure, the flight to another world, is commonly used to describe the movement of the soul from one body to another. In the Upaniṣads, the soul is depicted as a bird returning to its nest, and the Yogavāsiṣṭha says, “Flying up and flying up, enjoying one body after another, the particles of life finally go back to the place that is their own nest.”54 Yet the popularity of the story of the dream adventure in cultures where reincarnation is not generally accepted must make us pause before placing too much emphasis on karma as a generating, rather than simply a reinforcing, element of the story in India. For the paradox of the dreamer dreamt poses a challenge that is not entirely met by the theory of karma.

The monk is said to be free from the emotions, the unfulfilled longings, that animate and reanimate the creatures in his dream. His involvement in rebirth seems at first to be different from that of all the other characters in Vasiṣṭha’s story (or within the monk’s dream). The text insists that the monk himself was born purely by chance and that, again by chance, he became Jīvaṭa.55 That is, the monk did not become reborn to quench a thirst; he dreamed of another life out of pure intellectual curiosity. In other words, he became Jīvaṭa merely in play or for amusement (līlārtham), the word for purposeless sport being the same as the one used to describe why it is that God, who has no desires, bothers to make the universe at all. Rudra insists that the monk indulged in pure play when he imagined Jīvaṭa, and it is this same spirit of pure play that leads Rudra himself to decide to travel through the universes to wake up all the figures in the monk’s dream.56 The purity of the monk’s mind gave him the ability to become whatever he thought of; that is, he emptied his mind of everything but the one thing he wanted to become, with the result that he became that thought. The commentator adds that the monk assumed the form of another man in the manner of ascetics (yatis),57 for yogins can enter other peoples’ real, existing bodies.

Yet the monk is caught up, like the others, in his own imaginings; like them, he is astonished when brought face to face with the people in his dream, and Rudra says that the monk became Jīvaṭa because of his still-decaying karmic memory traces. The monk experiences precisely what they all experience, even though, unlike them, he sets out to do it on purpose. He was the victim of a mistaken perception (vibhrama); as soon as he wanted to become someone else, his mind lost its calm, like an ocean stirred by a whirlpool; his form changed because of the emotion that moved him at that time.58 Rāma is puzzled by this problem and asks Vasiṣṭha how a monk of such spiritual distinction could be caught up in the web of delusion.59 Vasiṣṭha does not answer this question specifically, but the subsequent analysis makes it clear that the monk’s great degree of mental control, though temporarily swept aside by the intensity of the dream, reasserted itself so that the monk could realize the dream of Rudra, could become awakened. The commentator introduces the last chapter with this verse: “In this chapter, the body of the monk is destroyed when he has been released through his meditation; just as the monk was first bound by and then released from his false perception, so, too, other people become bound and are released at their own awakenings.”60 The monk is part of the chain gang of rebirth, like all the rest of us, but he is first in line; and the story in the Yogavāsiṣṭha describes the moment when he breaks out, to set an example for all of us. At the end of the story, the monk is described as one who has become released from the wheel of rebirth during his lifetime.61

The monk is a Buddhist monk; he lives in a Buddhist monastery in a northern country called Jina, perhaps China. He is thus probably a Tibetan or Mahāyāna monk and, moreover, a shaman and a magician. But the power that he has is one that is possessed by Hindu yogins as well: “By their own powers over time and space, yogins and female yoginīs here can stand somewhere else, wherever they wish.”62 Vasiṣṭha is a Hindu Brahmin and a yogin; but he is also a storyteller. Like the monk and Rudra, Vasiṣṭha is able to make his dreams come true—and not merely his dreams but even his conscious, didactic examples. Moreover, Vasiṣṭha is not amazed at the things that happen in his story—not even at the fact that his story turns out to be true. He creates not out of idle curiosity or even in a spirit of playfulness but to teach Rāma a lesson. Unlike the Brahmin in the monk’s dream, who, albeit a Brahmin, was not a particularly subtle theologian or accomplished sage, Vasiṣṭha knows all the answers; he alone never seems to be fooled.

Or so it seems. But when Vasiṣṭha replies to another of Rāma’s questions, the dilemma moves onto another plane altogether:

When Vasiṣṭha had finished speaking, Rāma asked, “Is there such a monk? Search within yourself and tell me right away.” Vasiṣṭha said, “Tonight I will go into a deep trance and search the universe to find out if there is such a monk or not, and tomorrow morning I will tell you.” When they met again on the next morning, Vasiṣṭha said, “Rāma, I searched for that monk for a long time yesterday, with the eye of knowledge, the eye of meditation. Hoping to see such a monk, I wandered through the seven continents, and over the mountains of the earth, but no matter how far I went, I could not find him. For how could something from the realm of the mind be found outside it?

“But then, near dawn, once more I went north in my mind, to a glorious country named Jina, where there is a famous monastery built over an anthill. And in that monastery, in the corner of a hut, there was a monk named Far Sight [Dīrghadṛśa], who had been meditating for twenty-one nights. His own servants did not enter his firmly bolted house, for they feared that they might disturb his meditation. In his own mind he was there for a thousand years. (In a former eon there was once another monk of this very sort, just as I described him, and this one today is a second.) And when, just in play, I searched through other universes, I found, in a universe in the corner of space in the future, another monk just like that, with the same powers. And even in this very assembly there are people who will someday have the very same experiences and take on such a form and do such things, when this illusion will cast its spell over them.”

Then Rāma’s father, Daśaratha, said to Vasiṣṭha, “Greatest of sages, let me send my men to the hut of that monk to awaken him and bring him right back here.” Vasiṣṭha said, “Greatest of kings, the body of that monk no longer has the breath of life in it; it is dissolved with rot; it is no longer the vessel of a living creature. The soul of that monk has become the swan of Brahmā; during his own lifetime he has been released and is no longer subject to rebirth. At the end of a month, the monk’s servants, longing to see him, will force open the bolts, and they will wash his body and throw it away. Since the monk himself has left that body and has gone somewhere else, how could anyone wake up that ruined corpse in the monastery?”63

What are we to make of this epilogue? Rāma’s questions begin to consider the possible reality not of the characters in the monk’s dream but of the monk himself, that is, the reality of a character in a story told by Vasiṣṭha. And in his response to Rāma, Vasiṣṭha jumps out of the frame of narration and into his own story, just as the monk jumps out of the frame of his dream to meet the people he dreams of—or, perhaps, as Rudra jumps out of the frame of his divine mind to meet the thoughts in it. This adds a new dimension to the nested levels of the dream, for now we have Vasiṣṭha thinking of Rudra, who is realizing the monk, who is dreaming of Jāvaṭa and the others. It also adds another figure, Vasiṣṭha, to the list of those who are privileged to manipulate the strings of the puppets within the cosmic drama by giving physical form to their mental images.

Vasiṣṭha is at first skeptical of any possibility that his own mental constructs could be real; as he says to Rāma, “No matter how far I went, I could not find such a monk; for how could something from the realm of the mind be found outside it?”64 It would appear that, at this point at least, Vasiṣṭha aligns himself with those who are amazed to find their mental creations coming to life. Yet he does go to look for the monk, nevertheless. By seeking the monk, Vasiṣṭha acts out the idealistic assumptions of the text, assumptions that have already been challenged by the skepticism of Rāma and by Vasiṣṭha own initial doubts. But Vasiṣṭha finds the monk, and, by finding him, he not only discredits that skepticism but greatly strengthens and enhances the idealistic argument; for he demonstrates that works of artistic creation—the stories that we make up to prove a point—reflect some aspect of reality, one that most of us do not have the powers to prove, as Vasiṣṭha did. This is an important extension, for it implies that this reality is reflected not only in dreams—which we take to be real while dreaming but retroactively define as unreal when we awake—but even in stories which we take to be unreal from the start—artistic creations, which we think we control. The artist, like the god, catches the wave of māyā; the things that he imagines are real.

Why did Vasiṣṭha think that he could find the monk, since the monk was merely a creature in a story he had told and, presumably, made up himself? The commentary suggests that Rāma might have wrestled with this problem before framing his question to Vasiṣṭha:

Rāma was full of doubt and curiosity. He praised his guru and recognized the purpose of his instruction, but he said, “Search within yourself and ask yourself this question: ‘Even though I imagined this monk and spoke about him in order to enlighten you, Rāma, nevertheless did he actually come into existence somewhere?’ For it is simply not possible that a person that you would talk about would not have some sort of true essence.”65

Rāma was amazed by the tale of the monk’s dream; that is, he shared to some extent our common-sense intuition that dreams are not real. Yet Rāma’s question and Vasiṣṭha implicit affirmative answer—for he does go to look for the monk—suggest that both of them were at least half convinced of the real existence of the monk; that is, they shared to some extent the philosophy set forth in the text, in flagrant violation of their common sense. Their ambivalence is explicitly stated: they were amazed and not amazed. They wanted to find out for sure, and so Vasiṣṭha set out to test his hypothesis. Both Rāma and Vasiṣṭha felt that there was, in fact, a possibility that Vasiṣṭha mental creations might have a physical reality. The fact that it never occurred to Vasiṣṭha to go and look for the monk until Rāma asked him to do so, and the brusqueness of his initial reply to Rāma—“How could you expect to find . . .”—probably indicate Vasiṣṭha belief that it does not really matter at all if one finds the specific real monk of the dream; Vasiṣṭha didactic point lies elsewhere. People do not usually test such basic assumptions, as we saw in the context of unreality testing in chapter four. Nevertheless, to please Rāma, he does go and look, and he is not at all amazed in the end to find that the monk does exist. This is the psychology of the text, and it is similar to the psychology of the stories of Lavaṇa and Gādhi.