2 | Interrogating the Oracle

From the imaginal nature of the Yijing texts and from the approach to divination outlined above, we can derive a few indications about how best to formulate a question to the oracle.

1. Ask only questions that are emotionally significant for you. The emotional charge in your question is the energy that activates the archetypal images in the answer. Only then can they speak to you and cause a rearrangement of your view of the situation. A question asked out of simple curiosity rarely gets a meaningful answer: the psychic energy required for significantly processing the matter is simply not available.

2. Divination is not meant to replace critical reflection and introspection. Interrogating the oracle is useful only after you have deeply examined the situation and yourself and out of this examination you have distilled an appropriate question.

3. Avoid asking the Yijing what to do, and avoid asking questions that expect yes or no as an answer (e.g., is it right to do this? will this succeed?). The answer will consist of images, and it will say neither yes nor no: it will be up to you to decide for a yes or a no, based on the resonance that those images call up in you.

4. Avoid alternatives (e.g., /should I do this or that?). If the question is formulated as an alternative, it is difficult to decide whether the images contained in your answer refer to “this” or to “that.” When you are faced with an alternative, make a tentative choice (maybe the choice that is closer to your heart or the one that awakens more energy in you) and “test” it with the Yijing (“what about doing this?”). The answer will usually indirectly illuminate also the other option. A typical formula we often used at Eranos is “give me an image of . . .” (this situation, this choice, my attitude, etc.).

5. Be as specific as possible. Do not be afraid to narrow your question down. The answer to a vast or general question is often difficult to interpret, because the images can be read in too many different ways. On the contrary, starting from a concrete and emotionally significant question, the answer of the oracle frequently expands to include larger issues in the consultant’s life.

At Eranos (see p. 50ff., “The Yijing at Eranos”) we used to point to a little stone slab in the Eranos garden as a symbol of this narrowing down the question and opening to a wider perspective in the answer.

THE STONE SLAB DEDICATED TO THE “UNKNOWN SPIRIT

OF THE PLACE” AT ERANOS. (Courtesy of the Eranos Foundation)

The slab had been placed there by Olga Froebe-Kapteyn, the founder of Eranos, and C. G. Jung to honor the “unknown spirit of the place.” They both felt that the Eranos endeavor was supported by an unknown presence, a genius loci ignotus. The little monument was commissioned from a sculptor friend of theirs and represents an hourglass shape, which curiously fits with the process of interrogating the oracle. In the top half of the hourglass all the complexity and confusion of our existential situation gets narrowed down to a very pointed, specific question. In the lower half, starting from that narrow focus, the oracle’s answer opens up to embrace a much larger dimension.

In the Yijing, the dynamics of yin and yang is represented by the interplay of two types of line, the opened line7( ![]() ) and the whole line (

) and the whole line (![]() ). The opened line is yin, supple, flexible, pliant, tender, adaptable. The whole line is yang, solid, firm, strong, unyielding, persisting. And just like the two fundamental qualities they represent, the opened and the whole line are animated by a movement that transforms them into each other. For each type of line we are thus led to consider two possibilities: the line can be “young,” i.e. still fully expressing its own nature, or “old,” i.e. past its culmination and ready to transform into its opposite. Altogether we have therefore four types of lines:

). The opened line is yin, supple, flexible, pliant, tender, adaptable. The whole line is yang, solid, firm, strong, unyielding, persisting. And just like the two fundamental qualities they represent, the opened and the whole line are animated by a movement that transforms them into each other. For each type of line we are thus led to consider two possibilities: the line can be “young,” i.e. still fully expressing its own nature, or “old,” i.e. past its culmination and ready to transform into its opposite. Altogether we have therefore four types of lines:

| lao yin, old yin | |

| shao yang, young yang | |

| shao yin, young yin | |

| lao yang, old yang |

The young lines are stable lines, while the old lines are transforming: they are animated by a movement into their opposite and are therefore dealt with in a special way. It is customary to mark the transforming lines in order to distinguish them from the stable lines. In this book they are indicated by the red color. You may also choose to mark them with two different symbols of your choice, e.g. a cross or a circle.

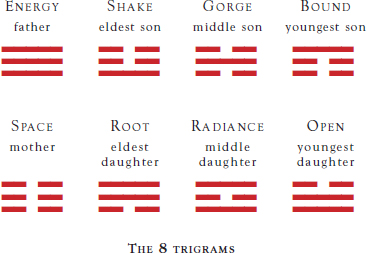

Leaving aside for the moment the issue of transformation and focusing merely on the yin or yang quality of the lines, we see that they can be combined to form a three-line figure, a trigram, in eight possible ways.

The eight trigrams, ba gua, have a special significance in Chinese cosmology (for further details, see p. 64, The eight trigrams and their attributes). They are conceived as a family consisting of father, mother, three sons and three daughters.

The eight trigrams are the building blocks of the sixty-four hexagrams (also called gua) of the Yijing, each consisting of a lower (or inner) trigram and an upper (or outer) trigram.

The hexagrams are triggers for the inner process that will lead you to your answer. Each corresponds to a basic configuration of archetypal energies. The Chinese saw the 64 hexagrams as an exhaustive catalog of all possible processes between heaven and earth:

The Book of Changes is vast and great. When one speaks of what is far, it knows no limits. When one speaks of what is near, it is still and right. When one speaks of the space between heaven and earth, it embraces everything.8

You will use the specific hexagram texts identified by casting the yarrow stalks or tossing the coins as entry points to a deeper intuitive understanding of your situation, as seeds of an associative process to clarify the dynamic forces at work in your psyche in the context defined by your question.

Energy moves in the hexagrams from the bottom up, like sap rising in a tree. The lines in a hexagram are numbered accordingly: the bottom line is the first and the top line is the sixth. When you find the lines of your hexagram by counting the yarrow stalks or by tossing the coins, you start from the bottom and sequentially work your way up to the top line. Each toss of the coins or each counting the yarrow stalks gives you one of the four types of line: old yin, young yang, young yin, old yang.

Before you begin the procedure, it is advisable to have your question written down in front of you. Sometimes the exact formulation of the question really makes a difference in the interpretation of the answer.

Tossing three coins six times is the simplest and quickest way to form a hexagram. This procedure became popular during the Southern Song dynasty (1127–1279).

Take three coins and decide which side is yin and which is yang. The yin side takes the value 2, the yang side the value 3. Each toss of the three coins then gives you, upon summing their values, 6, 7, 8 or 9. Write this number down and next to it draw the appropriate type of line according to the following table:

| 6 old yin | |

| 7 young yang | |

| 8 young yin | |

| 9 old yang |

Six tosses of the coins identify the six lines of a hexagram (from the bottom up), including their young or old quality.

This is the traditional way to form a hexagram. It is quite a bit more involved and slower: it is a form of active meditation, and each step of the procedure has a symbolic significance. A further difference between the two procedures is the fact that the probability of obtaining a transforming yin or yang line is symmetric in the coins method and asymmetric in the yarrow stalk one: in the latter, a yang line transforms three times more often than a yin line, i.e. a 9 is cast three times more often than a 6. This is traditionally seen as reflecting an intrinsic difference between the two types of line, yang being more “mobile” than yin.

You need 50 short sticks, traditionally prepared from stalks of yarrow (Achillea millefolium), a common plant in all temperate climates. Yarrow stalks are cut during the summer, when the plant is fully developed, and are left to dry for a few months. If you do not have yarrow stalks, any sticks of manageable size, say between three and ten inches long, will do.

YARROW (ACHILLEA MILLEFOLIUM)

The procedure, which will be described explicitly in the following paragraphs, is thus outlined in the Xici, the Great Treatise, the fundamental commentary on the cosmological symbolism of the oracular texts:

The number of the total is fifty. Of these forty-nine are used. They are divided into two portions, to represent the two primal forces. Hereupon one is set apart, to represent the three powers. They are counted through by fours, to represent the four seasons. The remainder is put aside, to represent the intercalary month. There are two intercalary months in five years, therefore the putting aside is repeated, and this gives the whole.9

The witness

From the bunch of 50 yarrow stalks take one and put it aside. It will be a silent witness to your whole consultation. It symbolizes the axis of heaven and earth, the One, the unmoving center of all change. The Daoist philosopher Wang Bi (226–249) wrote:

Fifty is the number of the great expansion (the number accounting for the transformations of heaven and earth). The fact that only forty-nine [yarrow stalks] are used means that one is not used. Since it is not used, its use is fully realized; since it is not a number [like the others], numbers can accomplish their work. It is the taiji of change . . .10

Forming a line—first step

Divide the remaining 49 stalks into two random portions. This opening gesture (which will be repeated three times for each line of the hexagram) is the crucial moment of divination: symbolically it corresponds to opening up to receiving the answer to your question.

Take a stalk from the left portion and put it between the little finger and the ring finger of your left hand. Count the stalks of the right portion by dividing them in groups of four stalks each, until you have a remainder of one, two, three or four stalks (if there is an exact number of groups of four stalks, the whole last group is the remainder). Put this remainder between the ring finger and the middle finger of your left hand.

Now count the stalks of the left portion in groups of four in the same way, and put the remainder between the middle finger and the index finger of your left hand.

Set aside the stalks you have between your fingers (if you have done things right, their number will be either five or nine) and collect all groups of four (right and left) in a single bunch again.

Forming a line—second step

Again divide the bunch into two random portions; again take a stalk from the left portion; and again count the stalks in the right and left portions in groups of four, exactly as before, putting the remainders between the fingers of your left hand. Set aside the stalks you have between your fingers (this time their number will be either four or eight). Keep them separate from those you have set aside before (a convenient way of doing this is laying them across each other): this will remind you that you have just completed the second step of the procedure. Then collect all groups of four (right and left) in a single bunch again.

Forming a line—third step

Repeat the same sequence of operations a third time: divide into two random portions, take a stalk from the left portion, count the stalks in the right portion and left portion in groups of four, set aside the remainders (again their number must be either four or eight). This time leave the groups of four spread out in front of you and count them. Their number will be 6, 7, 8 or 9.

Write this number down and next to it draw the appropriate type of line according to the table:

| 6 old yin | |

| 7 young yang | |

| 8 young yin | |

| 9 old yang |

This is the first (i.e., bottom) line of your hexagram.

Forming a hexagram

Repeat the same three steps for each of the following lines of your hexagram, building the hexagram from the bottom up.

Primary and potential hexagram

Whether you have used the coins or the yarrow stalk method, after six tosses of the coins or after repeating six times the three steps outlined above you will have a complete hexagram. For the sake of concreteness, let us follow through a specific example of consultation.

Let us assume that you have obtained the following sequence of numbers:

8, 8, 9, 7, 8, 7.

Then you will draw the following hexagram:

| 7 | |

| 8 | |

| 7 | |

| 9 | |

| 8 | |

| 8 |

This is your primary hexagram, the main key to answering the question you have brought to the oracle. If there are no transforming lines (no sixes or nines), the primary hexagram is the whole answer.

If there are transforming lines (as in the above example), then you need to take their transformation into account also. Beside your primary hexagram you will draw a secondary or potential hexagram by copying the stable lines (the sevens and eights) unchanged and replacing the transforming lines (the sixes and nines) with their opposite. Thus in the example above:

| 7 | ||

| 8 | ||

| 7 | ||

| 9 | ||

| 8 | ||

| 8 | ||

| primary hexagram |

potential hexagram |

(Notice that in your potential hexagram the lines are no longer marked as “young” or “old.”)

If your primary hexagram is a map of the archetypal energies constellated by your question and active in your situation, the potential hexagram traces a potential development of that constellation, a tendency that is there in the present situation and will manifest, given the appropriate circumstances. This potential development may be something to aim for or may be something we should strive to avoid, in which case the potential hexagram texts can be read as a warning.

You are now ready to identify your primary and your potential hexagram and to read your answer. The easiest way to identify a hexagram is to look it up in a hexagram table. Find the upper trigram (top three lines) of the hexagram in the top row and the lower trigram (bottom three lines) in the left column of the table. (Disregard the “young” or “old” quality of the lines at this stage: now you only need to consider their opened or whole quality.) The hexagram and its number are given at the intersection of the column corresponding to the upper trigram and the row corresponding to the lower trigram. Thus in our example the primary hexagram is hexagram number 56, Sojourning, and the potential hexagram is hexagram number 35, Prospering.

Hexagram table with example column and rows highlighted

In the Eranos Yijing the oracular texts are printed in red, while all the added explanatory material is in black. The oracular and the exegetic texts of each hexagram are distributed in various sections, which will be illustrated in detail in Sections of a hexagram (see p. 25).

When in your consultation you have no transforming lines (no sixes or nines), your answer consists of all the sections of your primary hexagram, except the Transforming Lines section.

When in your consultation you have transforming lines, your answer consists of:

• all the sections of your primary hexagram, except the Transforming Lines section;

• in the Transforming Lines section the texts referring to the specific transforming lines you have got;

• the Image of the Situation and the Outer and Inner Trigram section of your potential hexagram.

Thus, in the example given above, your answer would include:

• all the texts of hexagram 56, except the Transforming Lines section;

• the text of Nine at third in the Transforming Lines section of hexagram 56;

• the Image of the Situation and the Outer and Inner Trigram of hexagram 35.

The amount of information contained in the above mentioned texts may be quite overwhelming at first. It may be helpful to outline priorities, so that you do not get bogged down in details, losing sight of the essential. An easy sketch of the hierarchical order of the layers of information constituting your answer is the following:

• The name of your hexagram with the associated Fields of meaning is the core of your answer. That is the archetypal image that most closely describes the issue raised by your question. While reading all the other texts you should always keep this core message in mind. Other images contained in your answer may modulate it to some extent: but the title of your primary hexagram will remain a constant reference.

In this book, the title of each hexagram is followed by a sentence beginning with the words: “The situation described by this hexagram . . .” This sentence does not belong to the oracular texts, but has a didactic purpose. It should be taken as a first tentative interpretation of that particular hexagram, a first step in familiarizing yourself with it.

• The Image of the Situation of your primary hexagram, together with the associated Fields of meaning, is the next layer of the onion. This is the fundamental oracular text of the hexagram and its first word is the name of the hexagram itself. Traditionally called Tuan (head), this text belongs to the most ancient layer of the Yijing texts.

• The Outer and Inner Trigram section of your primary hexagram, while not being part of the oracular texts proper, will give you an imaginal description of the outer and inner aspects of your situation. The upper or outer trigram will generally mirror aspects of your environment, while the inner may refer to psychic realities operating in yourself.

If you have not got any transforming lines, this is all you need to consider in a first approach to your answer. You may want to return to it later to include further suggestions coming from the remainder of your hexagram.

When there are no transforming lines people sometimes wonder if they should interpret this as a sign that their situation is static and there is no transformation in it. Not at all: in life no situation is exempt from change. If you get a straight hexagram, with no transforming lines, it simply means that that specific archetypal energy constellation is all that is relevant for you to consider right now. You can be sure that from dealing appropriately with it, appropriate change will arise.

• If you have got one or more transforming lines (sixes and nines), the texts of your transforming lines are the next important layer of the onion. They introduce specific features that complete or alter, sometimes significantly, the general picture given by the name of the hexagram and by the Image of the Situation. Generally speaking, if the texts of the hexagram as a whole represent the overall flow of energy in the given situation, the single lines can be taken to describe currents and eddies within that overall flow.

We do not know how oracular responses containing more than one transforming line were traditionally interpreted. Integrating the messages of a number of transforming lines when these are at variance with each other is one of the challenging aspects of Yijing divination. Sometimes these messages refer to aspects of the situation which develop sequentially in time, and sometimes they describe complementary aspects coexisting in the present.

• Next you will read the title and the Image of the Situation of your potential hexagram, together with their Fields of meaning. The potential hexagram, as we have seen, points to a possible development of the situation described by your primary hexagram.

• Finally, take a look at the Outer and Inner Trigram section of your potential hexagram. Which one of the two trigrams has changed? Have they both changed? This transformation may point to a possible development in the outer or inner aspects of your situation.

Exploring these core layers of meaning of your answer should be sufficient to give you a rich picture of your situation, of your attitude and of the potential developments thereof. We suggest you start with this. But then, of course, feel free to revert to your primary hexagram and explore the other sections of it, using the guidance of Sections of a hexagram on p. 25. (Normally in the potential hexagram you will only consider the Image of the Situation and the Outer and Inner Trigram sections.) Pay attention to the words that awaken in you a particular resonance. Put aside whatever does not call up a response in you and focus on what has the strongest emotional resonance, just as you would when analyzing a dream.

Rolling the words in your heart

The language of the Yijing is an imaginal language. Its words have multiple layers of meaning, which this translation makes available to the reader through the Fields of meaning associated with the oracular texts. While reading your answer, try to hold all these meanings simultaneously and feel free to replace any word in the oracular texts with one of its associated meanings, if that meaning has a particular resonance in you.

There are no rules for interpreting these texts. They do not have an intrinsic meaning, independent from you and from your question. The Chinese commentary tradition suggests that turning and rolling the words in your heart is the key to accessing the “light of the gods.” (It is good to remember in this respect that the Chinese word for “heart,” xin, embraces both what we call “heart” and what we call “mind.”) Focus on the words and images that have the strongest impact on you. Remember that the answer does not reside in the words, but arises in the process those words trigger in you. Just as the emotional content of your question is important, so it is important that you let yourself be touched by the answer.

The openness of the oracular texts can be unsettling at first. You may feel overwhelmed by a flood of potential meanings. This wealth of possibilities is an expression of the archetypal nature of the divinatory language. The guiding principle is to listen to the resonances the oracular images arouse in you.

Chinese as an imaginal language

The structure of ancient Chinese is very different from that of Western languages. Its grammar is minimal. Its words are signs (characters) that evoke images. A single character can function as a verb, a noun or an adjective. By itself a character does not specify a mode, tense or person and it does not distinguish between singular and plural. Furthermore it frequently embraces various related clusters of meanings that slide into each other by a sort of free play of the imagination. In this respect Chinese characters are a bit like those iridescent gems that appear to be a different color depending on the angle from which you look at them. Their fluidity of meaning is remarkably similar to the interconnectedness which characterizes archetypal images, as Jung pointed out.

As an example of the “play of archetypal motifs” in Chinese characters consider the word “open,” dui, which is the name of one of the trigrams of the Yijing.

Open, DUI: an open surface, promoting interaction and inter -penetration; pleasant, easy, responsive, free, unhindered; opening, passage; the mouth; exchange, barter; straight, direct; meet, gather; place where water accumulates. Character: mouth and vapor, communication through speech.

The character for dui is composed of the signs for mouth and vapor, which suggest speech and communication. Dui includes the idea of openness, permeability, ease of communication and exchange. Therefore a cluster of meanings extends in the direction of commercial transactions: to barter, to buy, to sell, price, value, equivalent. A market is a meeting place par excellence, so dui is also to meet, meeting place, gathering; and by extension also a place where water is collected, a marsh, a lake, a pond. The image of this body of water still contains the idea of vapor and of permeability: it is conceived as a wide, flat water surface from which vapors rise, so that there is a permeability, an openness not only horizontally, but vertically as well. And still from the idea of a meeting place and gathering, or maybe from the peaceful landscape of the pond, comes another cluster of meanings, which has to do with joy, happiness, satisfaction.

Modern Chinese of course has a number of devices apt to contain this fluidity and make the language more precise. Not so the archaic language of the Yijing, in which the imaginal fields of single characters stand next to each other as islands in an archipelago. They are more akin to figures in a dream than to building blocks of a logical structure. That is the elusive character of the oracular texts—and the source of their potency as mirrors of psychic reality.

BASIC FEATURES OF THE ERANOS TRANSLATION

The Eranos Yijing attempts to preserve as much as possible of the mirroring potency of the oracular language by adopting a translation strategy whose main criteria are outlined below.

Each Chinese character is translated consistently by the same English word, which becomes a sort of code identifying the character. This word corresponds as much as possible to a core of the field of meanings associated with the character, but is not to be taken as a complete rendering of the character. Rather it is a core-word, a key to enter the semantic field of the character.

The semantic field of each character appearing in a given oracular text is described in the Fields of meaning immediately following that text. All the associations listed in it resonate together in the Chinese character, and they can be imagined as being simultaneously present in the core-word. They allow the Western reader to access the range of meanings that a cultured Chinese reader immediately perceives in the character. While reading the answer to your question, you are free to replace a core-word with any of the words listed in the corresponding Field of meaning that have a special resonance in you.

Oracular texts are distinguished from appended explanatory texts by their typographical face: they are printed in red, while all else is in black. Furthermore, within the oracular texts core-words are printed in boldface. Wherever articles, prepositions and conjunctions have been added to render the text at least minimally legible, these are printed in lightface characters. The lightface words are to be taken only as suggestions: the “naked” Chinese text consists only of the boldface words.

The standard reference for all modern versions of the Yijing is the Palace Edition, published by the emperor Kangxi in 1715. In it the Yijing consists of ten books, known as the Ten Wings, and the references to each hexagram are spread throughout the Ten Wings. For ease of consultation, in contemporary use all the texts relating to the same hexagram are collected under that hexagram’s title. The Eranos Yijing also adopts this much more practical format.

Nevertheless the texts extracted from various places in the Ten Wings differ widely in origins, style and function. Therefore in each hexagram they are presented in different sections, which are briefly described below.

This is the fundamental oracular text of each hexagram and its first word is the name of the hexagram itself. Traditionally called Tuan (head), this text belongs to the most ancient layer of the Yijing and together with the main text of the Transforming Lines constitutes the First and Second Wing (Tuan zhuan, commentary on the Tuan).

As we have noted above, this section is the core of your answer, the basic archetypal configuration you are confronted with.

The next two sections do not include oracular texts, but contain exegetic material related to the structure of the hexagram.

This section analyzes the hexagram in terms of the two trigrams that constitute it. The upper trigram is traditionally associated with the outer aspects of your situation, while the lower trigram reflects the inner (psychic) aspects of your situation. In this respect the transition from the third line (top of the lower trigram) to the fourth line (bottom of the upper trigram) often corresponds to a transition from the inner gestation to the outer manifestation of a certain archetypal image.

The attributes of the two trigrams outlined in this section are drawn from the Eighth Wing, Shuogua, Discussion of the Trigrams, and their placement in the Universal Compass (see below) is based on the correlative system outlined in the Baihu Tong, Discussions in the White Tiger Hall,11the proceedings of the scholarly gathering that consolidated the interpretation of the Confucian classics under the Han in 79 CE.

Beside the upper and lower trigram, two inner or “nuclear” trigrams have attracted the scholars’ attention since Han times (206 BCE – 220 CE). They consist of the second, third and fourth line and of the third, fourth and fifth line respectively. When these two trigrams are placed one on top of the other, we obtain a hugua, a “twisted hexagram,” also called, in modern use, a “nuclear hexagram.” The nature of the procedure is such that in a nuclear hexagram the two top lines of the lower trigram are identical to the two bottom lines of the upper trigram: therefore there are only 16 nuclear hexagrams for the 64 hexagrams. (Furthermore the nuclear hexagrams of number 1 and number 2, composed of all yang and all yin lines respectively, coincide with the hexagrams themselves.)

There is no traditional consensus on the interpretation of nuclear hexagrams. In the Eranos Yijing they are called “counter hexagrams” and they are taken to represent a shift in emphasis, often in the opposite direction compared to that of the primary hexagram. The “counter hexagram” therefore points to something that is not the case or that should not be done in the given situation.

The text of this section is drawn from the Ninth Wing, Xugua, Sequence of the Hexagrams, which connects the 64 hexagrams in a series, deriving the action of each as a natural consequence of some aspect of the action of the previous one. This section always contains the sentence From anterior acquiescence derives the use of . . . followed by the name of the hexagram. This rather awkward formula means that fully availing yourself of the present hexagram requires understanding and accepting its connection with the preceding one. This connection may highlight some aspect of the origin of your situation and your question.

This section, drawn from Tenth Wing, Zagua, Mixed Hexagrams, draws a comparison between adjacent hexagrams which are structurally related to each other (an odd numbered one and the following even numbered one) by emphasizing a specific characteristic of each, sometimes by contrast, sometimes by a more subtle differentiation.

This section is present in ten hexagrams only. It comes from the Xici, Additional Texts,12also known as Dazhuan, Great Treatise, which constitutes the Fifth and Sixth Wing and is the largest and most important commentary on the oracular texts. This section relates the action of the hexagram to the realization of dao, the exercise of virtue or fulfillment of one’s true nature.

Together with the Comments part of the Transforming Lines, the texts of this section constitute the Third and Fourth Wing, Xiang Zhuan, Commentary on the Images (or Symbols). They consist of two parts.

The first part identifies the hexagram through the symbols of the two trigrams that compose it (e.g. Clouds and thunder: sprouting or Below the mountain emerges springwater. Enveloping). See The eight trigrams and their attributes, p. 64, for the symbols of the trigrams.

The second part describes an exemplary behavior, offering as a model a junzi, a “disciple of wisdom,” one who strives to manifest dao in her or his actions, the “crown-prince,” or the “earlier kings,” sovereigns of a mythical age when humans were in tune with heaven and earth.

This section contains the oracular texts connected with the individual lines of the hexagram. Each line has a main text and a commentary text. The main text comes from the First and Second Wing, together with the Image of the Situation. The commentary text, together with the Patterns of Wisdom, comes from the Third and Fourth Wing.

Only the texts corresponding to the transforming lines you have obtained when casting your hexagram (the sixes and nines) belong to your answer. They introduce specific features that complete or alter more or less significantly the general picture given by the Image of the Situation.

This is a commentary text on the Image of the Situation, also included in the Tuan Zhuan, the First and Second Wing. It amplifies and paraphrases words and sentences of the Image and offers a technical analysis of the structure of the hexagram in terms of:

• solid and supple, i.e. relationships between whole and opened lines in the hexagram;

• appropriate or non appropriate position of individual lines (a whole line is in an appropriate position in an odd numbered place, an opened line is in an appropriate position in an even numbered place);

• correspondence or non correspondence between lines occupying the same position in the upper and the lower trigram, i.e. between the first and fourth, second and fifth, third and sixth line of the hexagram (these are said to be in correspondence if one is whole and the other is opened).

These technical aspects are the foundation of a complex geometry and numerology of the Yijing. The Eranos Yijing, focusing on the imaginal content of the oracular texts, does not particularly pursue this line of thought. For this reason the Image Tradition has been placed at the end of each hexagram: although adding useful insights, it does not fundamentally change the picture defined by the other sections.

| Eranos Yijing | Wilhelm translation | Palace Edition |

| Image of the Situation | The Judgment | Tuan Zhuan (Wings 1 and 2) |

| Outer and Inner Trigram | Book II—Discussion of | Shuogua (Wing 8) the Trigrams |

| Counter Hexagram | Book II—The Eight Trigrams and Their Application | Preceding Situation |

| The Sequence | Xugua (Wing 9) | Hexagrams in Pairs |

| Miscellaneous Notes | Zagua (Wing 10) | Additional Texts |

| Appended Judgments | Xici (Wings 5 and 6) | Patterns of Wisdom |

| The Image | Xiang Zhuan (Wings 3 and 4) | Transforming lines— |

| The Lines a) | Tuan Zhuan (Wings 1 and 2) main text | Transforming lines— |

| The Lines b) | Xiang Zhuan (Wings 3 and 4) comments | Image Tradition |

| Commentary on the Decision | Tuan Zhuan | (Wings 1 and 2) |

SECTIONS OF A HEXAGRAM IN THE ERANOS, WILHELM

AND PALACE EDITIONS OF THE YIJING

REMARKS ABOUT THE ERANOS TRANSLATION

The Eranos Yijing’s aim is to open up as much as possible the imaginal richness and flexibility of the oracular texts to a Western user who is not a sinologist. The following remarks are meant to allow the reader to form a clearer picture of the original Chinese texts through the Eranos translation.

Romanization of Chinese characters

The romanization of Chinese characters in this book follows the pinyin system, officially adopted by the Chinese government in 1958 and by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) in 1982.

In the past a variety of systems have been used in the West, originating considerable confusion. The most widespread of these, and formerly the standard in English-speaking countries, was the Wade–Giles system. Many terms are much more familiar to the Western reader in their Wade–Giles transcription than in the pinyin one (e.g. the title of this book is I Ching in Wade–Giles, Yijing in pinyin). But pinyin is now fast becoming the international standard, and it is definitely worthwhile having a single universal system.

Sources of the Fields of meaning

The associations listed in the Fields of meaning are drawn from the classic Chinese dictionary published by the emperor Kangxi in 1716 and from a number of valuable Western sources, particularly Wells Williams,13Couvreur14and the excellent recent dictionary of the Ricci Institute.15

The description of the characters is based on the Shuowen, the fundamental Han dictionary published in 121 CE. This traditional way of understanding characters does not necessarily fit with modern philological theories about their origins; but it has been kept here because it describes the “aura” surrounding these terms in Chinese literature and poetry.

A basic concept of the Eranos Yijing is to preserve a one-to-one correspondence between Chinese characters and English core-words, so that a core-word unerringly identifies a certain Chinese character. This device allows a Western reader to form as precise an idea as possible of the original Chinese text and makes a concordance to the Yijing in a Western language possible for the first time.

A rigorous application of the above criterion, though, is a very stringent constraint: in some cases a single English word effectively representing the coremeaning of a given character simply does not exist. Two further devices have been introduced in order to obviate this.

Hyphen: when two or more English words are needed to render the coremeaning of a single Chinese character, they have been joined by a hyphen. Hyphenated words therefore must be read as a single word. Examples: actualizedao, before-zenith, big-toe, break-up, bushy-tailed, etc.

Slash: when the core-meaning of a Chinese character has two equally important and intimately connected faces which are rendered in English by two distinct words, a slash has been used. Examples: almost/hint, big-toe/thumb, day/sun, etc. In these cases only one aspect of the word will appear in the text, e.g. sun, but the entry in the following Fields of meaning will list both aspects, for example“Day/sun, RI: the sun and the time of a sun-cycle, a day,” reminding us that the words “day” and “sun” are interchangeable and correspond to the same Chinese character.

A special case of composite entry is the word ’s/of/derive/it, zhi, which has two main uses in the Yijing:

’s/of/derive/it, ZHI: establishes between two terms a connection similar to the Saxon genitive, in which the second term belongs to the first one; at the end of a sentence it refers to something previously mentioned or implied.

The first use of zhi is a somewhat emphasized Saxon genitive, in that the Chinese language also has a plain possessive expressed by simply juxtaposing two terms (this has been rendered by a lightface ’s in the oracular texts). Therefore in the body of a sentence zhi has been rendered by a boldface ’s or by the words of or derive. For example:

Humbling: actualizing-dao’s handle indeed.

From anterior acquiescence derives the use of enveloping.

At the end of a sentence zhi has been rendered by it. For example, in

Using enveloping the great: heaviness. The Pattern King uses it.

it refers to the previously mentioned “heaviness of enveloping the great.” (The king mentioned, by the way, is King Wen, the mythical author of the Yijing, about whom see below, The Pattern King.)

Another special case is the general third person pronoun one/one’s, qi, which also means it/its, he/his, she/her, they/their. A proper entry for this word in the Fields of meaning would be rather cumbersome, as it would list all of the above separated by slashes. In this case we have made an exception to the general rule, adopting in the Fields of meaning different listings for the same character, but including a reference to all the other forms. For example:

Dragons struggle tending-towards the countryside.

Their blood indigo and yellow.

They/their, QI: general third person pronoun and possessive adjective; also: one/one’s, it/its, he/his, she/her.

A tiger observing: glaring, glaring.

Its appetites: pursuing, pursuing.

It/its, QI: general third person pronoun and possessive adjective; also: one/one’s, he/his, she/her, they/their.

Their in the first example and its in the second are the same word, qi. Notice also that the it of ’s/of/derive/it is not the same character as the it of it/its.

Frequently two or more characters are used as a unit, they make a short idiomatic phrase which has in the Yijing a specific sense. One such expression is below heaven, which indicates “the world.” In such cases the Fields of meaning describe the whole phrase, rather than the single terms. For example:

Below heaven, TIAN XIA: human world, between heaven and earth.

These idiomatic phrases have their own specific listing in the concordance. For example, all the occurrences of below heaven are listed separately from the occurrences of below and those of heaven in other contexts (and a reference “see also: below heaven” is added to the last two).

Some terms are used in the Eranos Yijing in a special way. The most significant of these are probably the words great and small. The corresponding Fields of meaning are:

Great, DA: big, noble, important, very; orient the will toward a selfimposed goal, impose direction; ability to lead or guide one’s life; contrasts with small, XIAO, flexible adaptation to what crosses one’s path.

Small, XIAO: little, common, unimportant; adapting to what crosses your path; ability to move in harmony with the vicissitudes of life; contrasts with great, DA, self-imposed theme or goal.

In the context of the oracular use of the Yijing, these terms more often refer to a way of dealing with situations than to something literally (or even metaphorically) great or small. Accordingly, in the Eranos Yijing they are generally used in the substantive form the great and the small. For example, the expressions usually translated as “great people” (or “the great man”) and “small people” are here rendered as the great in the person and the small in the person, referring to attitudes the consultant can identify in herself/himself, rather than to “great” or “small” people outside.

The reader who wishes to acquire an in-depth understanding of the language of the Yijing is warmly encouraged to make use of the concordance (a listing of all the occurrences of each word in the oracular texts). Comparing all the contexts in which a given term occurs adds significantly to the understanding of how that term is used in the Yijing. Noticing in which sections of the hexagrams specific words recur more frequently (or exclusively) offers interesting insights into the language of the various layers of the book. And the possibility of searching for a sentence by simply remembering one or two words is a precious tool for reconstructing past consultations or comparing answers obtained in different occasions.