1.

IT’S AN EGG WORLD AFTER ALL

For as long as eggs have popped from bird butts, they’ve been relished the world round—eaten, drunk, steamed, whisked, fried, baked, poached, cracked into dorm-room bowls of Top Ramen, coddled in Michelin-starred restaurants. People eat eggs everywhere. But how did this happen? Why did this happen? When did eggs conquer the world?

This first chapter is all about unlikely voyages: the journey that an egg takes from inside a chicken to the outside, and its geographic journey from Southeast Asia, where our domesticated chicken’s ancestor originated, onto plates and into bowls all over the world. (And that’s just one bird egg’s story—the tip of the egg iceberg! We also eat quail eggs, pheasant eggs, duck eggs, and ostrich eggs; in Iceland, people grapple down steep cliffs to harvest the beautiful blue eggs belonging to seabirds called guillemots. In Chile, birds called tinamous lay eggs that seem like ornaments: iridescent and beautiful—this page.)

Across the globe, despite innumerable cultural differences, we have all come to love eggs for pretty much the same reason: They are delicious. Eggs are what we humans have in common. The English wrap eggs in sausage and call those Scotch eggs (this page)—but people in India do it, too, and call it nargisi kofta. The egg tarts you might order with your dim sum made their way from Portugal to Hong Kong to Macau, and changed like a game of telephone: All the iterations turned out uniquely wonderful. Eggs get hard-boiled and steeped with tea in Taiwan and China (this page), and in Iran they do it, too, but with onion skins (this page). Eggs get poached into spicy tomato sauces in the Middle East as shakshuka (this page), which looks a lot like Italian eggs in purgatory, which looks a lot like Mexican Huevos en Rabo de Mestiza (this page).

This is a book about eggs. But more than that, it’s a book about mankind—it’s a book about us all. Eggs are often the first things that home cooks learn to cook, yet they’re among the hardest ingredients to master. Every great chef boasts a signature egg dish; no diner would ever dream of not offering an omelet. Eggs are a cornerstone of eating, cooking, and, yes, being human. They’re the world’s most important food.

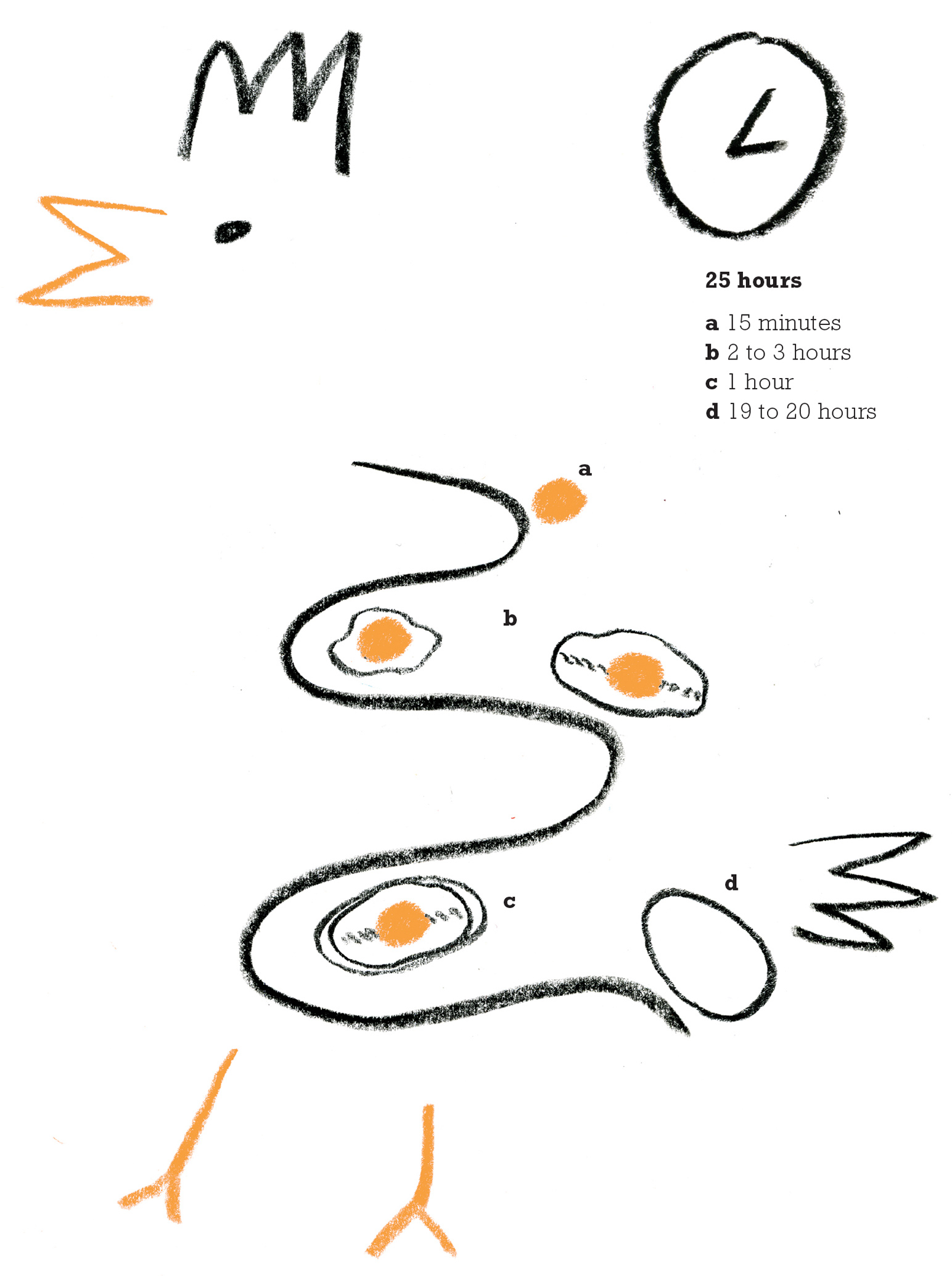

The JOURNEY of an EGG

Nina Bai

The egg is a single cell, the largest and least mobile of the reproductive cells. Avian eggs must contain all the provisions for a growing chick, barring some exchange of gases and water vapor. They’re gargantuan compared to mammalian egg cells, which take up nutrients from the mother via a placenta and can therefore pack light. Where a human egg cell is 0.1 millimeter in diameter, a chicken egg is about 50.

The Yolk

Hens are born with two ovaries, but as in most bird species, only the left one becomes fully developed. This may be an adaptation to cut down on weight for flight. After a hen reaches maturity between four and six months, it lays prolifically. Chickens are known as indeterminate layers, meaning they aim to achieve a certain clutch size (set of eggs) before they stop laying. But if the eggs are taken from the nests by predators—or human collectors—they will keep laying nearly every day. A hen can lay at the rate of about one egg per twenty-five hours. A domesticated chicken kept in conditions that mimic summer daylight hours can produce nearly three hundred eggs a year. A hen invests considerable effort in her eggs, depositing a quarter of her daily energy and about 2 percent of her body weight into each egg. In human terms, that would be a 150-pound woman creating a 3-pound egg—every day. If a hen lays 275 eggs in a year, she will have converted about six times her body weight into eggs.

The hen’s ovary resembles an uneven cluster of grapes, bulging with many egg cells at varying stages of maturity. An egg cell grows over one thousand times in volume during the ten weeks it takes to mature, with most of the action taking place in the tenth week. During this time, the egg cell rapidly accumulates the fats and proteins that form the yolk. These fats and proteins are synthesized by the liver and delivered through the bloodstream. The color of the yolk can vary from pale yellow to deep orange-red and depends on the pigments, called xanthophylls, in the hen’s feed. White maize, wheat, millet, and sorghum yield pale yellow yolks, grass and yellow maize produce dark yellow yolks, and supplements of marigold petals or red peppers can create even deeper shades.

On the outside, an egg-laden hen can be heard giving prelaying calls and seen inspecting her nest. Her nervous system senses the length of daylight, temperature, and food availability and sends the appropriate signals to the pituitary gland.

The White

A burst of luteinizing hormone from the pituitary gland triggers ovulation six to eight hours later. As a completed yolk erupts from the ovary, fleshy writhing fingers projecting from the funnel-shaped opening of the oviduct catch and engulf the yolk. From here, the yolk proceeds on a twenty-five-hour passage through the two-foot-long oviduct and acquires the white, membranes, and shell. (Sometimes two egg cells are released at the same time and become a double-yolked egg. This occurs in roughly one in one thousand ovulations and is more likely to happen in younger hens.)

The first fifteen minutes are spent in the oviduct’s funnel-shaped opening, known as the infundibulum (a), where the egg cell has the opportunity to meet its male counterpart. Sperm can be stored in the hen several weeks after mating. This is the juncture where the egg is fertilized. But sperm or no sperm, the yolk travels on to the magnum, the longest section of the oviduct.

For the next two to three hours, peristaltic muscle contractions move the egg along at 2.3 millimeters per minute. Protein-secreting cells of the oviduct coat the yolk with four layers of albumin (b) of alternating densities. The first layer is deposited while ridges in the oviduct rotate the egg. This forms a twisted hammock of dense albumin called the chalaza, which acts like elastic cords that suspend and anchor the yolk to each end of the shell. The chalaza protects the embryo from premature contact with the shell. Three more layers of albumin are deposited, forming about half the volume of the egg white in a finished egg.

The Shell

An eggshell protects the embryo from its surroundings while allowing gas exchange. In the next hour, moving at the rate of 1.4 millimeters per minute through a narrow section of the oviduct called the isthmus, the egg is enclosed in two thin-but-tough antimicrobial shell membranes (c). The final nineteen to twenty hours are spent in the two-inch-long uterus or shell gland. First, water and salts are pumped through the membranes to fill the albumen up to full volume. Next, calcium carbonate and protein are secreted by the uterine lining to form the shell. Magnesium and phosphate, in very small amounts, are also critical to the integrity of the shell. (An increase in these levels caused by exposure to pesticides such as DDT and DDE led to an epidemic of eggshell thinning that imperiled species from eagles to penguins in the mid-1900s.)

The shell contains some ten thousand microscopic pores, mostly concentrated at the blunt end of the egg. As the last rite in the shell gland, the egg is coated in a thin cuticle (d) that seals the pores to prevent water loss and block bacteria. As the chick grows, however, it requires more access to oxygen. Conveniently, the shell doubles as the source of calcium for the growing embryo, and as the calcium is converted into skeleton, the shell becomes more porous and allows more air exchange.

The cuticle also has a cosmetic effect, coloring the shell with molecules related to hemoglobin, such as porphyrin and biliverdin. Shells come in varying shades of white, brown, blue, green, and speckled patterns depending on the hen’s breed.

Hello, World

At the end of the twenty-five-hour journey, muscular contractions of the shell gland push the egg out of the oviduct through the cloaca. The cloaca is where the reproductive and excretory tracts of the chicken converge, but during laying the cloaca inverts (imagine a sock turned inside out) so that the egg avoids contact with excrement. Although the egg has traveled through the oviduct small end first, it is turned 180 degrees just before laying and comes out blunt end first.

As the egg cools outside the hen, its contents contract, causing the inner shell membrane to pull slightly away from the outer shell membrane, forming an air space at the blunt end. Just before hatching, a chick uses its beak to pierce into this air pocket and take its first breaths.

If the egg was fertilized in the infundibulum, it already contains some twenty thousand cells at the time it is laid. Crack open a typical store-bought egg, however, and you can locate the single nucleus of the unfertilized egg cell in the small white spot on the top of the yolk.

The EGG COLLECTOR

Adam Gollner

My landlord Claude was a kindly, batty old Frenchman—a beardless Santa Claus type, always smiling apologetically. His angel-soft white hair had an uncombable immunity to gravity, making it look like he wore a crown of broken dove wings. Two specific enthusiasms occupied him totally: opera and eggs.

Claude lived alone, a mélomane surrounded by his arias. The other collection was displayed in his foyer: over a hundred specimens of bird eggs inside a glass cabinet. I’d sneak peeks at them while paying the rent. They just sat there, their pastel surfaces radiating mystery and reflecting their owner’s gentle freakiness.

Not long after I moved into the building—I lived on the second floor, above his ground-floor apartment—Claude invited me to a Sunday afternoon get-together. Twenty or so people showed up, mainly fellow Verdi buffs, but also a few actual opera singers. As Claude greeted different partygoers, he seemed to be kind of hopping around, like a limping rooster. It turned out he had a terrible infection on his left foot. He kept hoping it would go away, he said, and now there was a possibility that he would have to have it amputated. His hobbies had grown so all-consuming that he’d neglected to pay attention to his basic health. When he bird-walked over and asked whether I was enjoying the party, I took the opportunity to inquire about the eggs. “You are interested in eggs?” he asked, his smiling face almost pained with nervous solicitude.

At the time, I wasn’t, really. What I was actually interested in was the fact that he was interested in eggs. We turned to the cabinet, where different colored eggs of various sizes had been grouped into neat, oval-contoured formations. “It’s just a little assortment,” he said, running a hand through his nest of hair. “I’m not too picky—as long as it’s an egg, I like it.” Most of the eggs were real bird eggs, but some weren’t. Expertly carved wooden eggs and smooth-shouldered porcelain eggs and faux-Fabergé-style crystal eggs sat next to matte ostrich eggs and marbled crow eggs and small Tiffany-blue robin eggs.

He told me how the actual bird eggs he’d purchased came with their insides removed through little pinholes at the base. These eggshells had identification tags next to them,although several others didn’t have any labels. “I sometimes find eggs on walks around the neighborhood or in the countryside,” he explained with a quiet giggle. He picked up a speckled, oblong one—a wild sparrow egg—and handed it to me. “I keep them whole, as is, the way they are in the nest.”

I felt its cool, light heft. There was something cosmic about the egg Claude had placed in my hands. Its exterior appeared to be spangled with tiny dots like distant stars in the night sky. Beneath that self-enclosed firmament were primordial waters and translucent proteins and a golden yolk, all crystallizing toward sparrowhood. I wasn’t just holding an egg; I was holding an unreadable map of the universe. Or that’s how Claude saw it—or how I saw him seeing it.

“Sometimes I hear a loud pop in the night,” he continued, in a stage whisper. “I’ve even gotten out of bed because I’m sure there’s an intruder in the house. But it always turns out it is just one of these eggs exploding.”

He shrugged in a what can you do? way. “If the bird doesn’t hatch, at a certain point, the gases and bacteria and what-not build up inside of them and the egg bursts. But not always. I don’t know why not.”

He may not have known, but I soon understood, firsthand, why it is that decorative eggshells are traditionally divested of their contents. Several times over the next year that I lived there, a putrid, sulfurous-fart smell would emanate from Claude’s apartment into the stairwell leading up to my apartment. It always took me a day or two to figure it out. The stench would linger there for close to a week, gradually fading away as the gasified embryo made its way back to the elements.

As revolting as those burst eggs smelled—and as relieved as I was to finally move out—I never looked at eggs the same way again.

*

The first times I saw quail, duck, and goose eggs for sale, I bought them, excited to find out how they differed from hen’s eggs. When a new butcher shop in my neighborhood started selling farm-fresh eggs, I noticed that they sometimes had varieties with a blue-green hue. They were from a breed called Araucana chickens, originally from Chile. They may not have tasted any different, but the beauty of their shells seemed to brighten any morning that started with them.

While looking up Araucanas, I came across a study of another South American bird that lays even more beautiful eggs. Tinamous are an order of partridge-like birds whose iridescent, shimmering eggs have been described by egg-spert Mark E. Hauber (author of The Book of Eggs) as being “so unique and unusual that it was hard to take my eyes off them.” In photographs, their glossy and reflective shells look as though they’ve been dunked in fresh paint. These come in a range of colors, from bright green to pale violet to fairy-tale gold. Unfortunately, they don’t seem to be available commercially anywhere in the world—except for one farm in the Bío Bío region of Chile, around a five-hour drive to the south of Santiago. When I reached out to the tinamou farmers via their Facebook page, they responded by inviting me over for breakfast.

Chilean Bush Tinamou

*

The tinamou farm I visited is located on the outskirts of Los Ángeles, Chile—not far from the towns of Santa Fe and Santa Bárbara. The owner is Alberto Matthei, fifty-seven, a tall, slender, kind-eyed, lifelong farmer in a thin plaid shirt and dusty jeans. His wife, Carmen Guzmán, is a pretty, glamorous woman who wears billowing wide-legged pants and a cross necklace.

Their farm turned out to be a modest operation, just a few long rows of chicken-wire coops, each large cage containing around fifteen or so tinamous. They have around six thousand birds. They’re intentionally keeping it small-scale and semi-free range. “We never want the tinamous to face what chickens do on those big farms,” Matthei told me, when we met on a sunny February afternoon.

The tinamous were small and beige, not too different from quails. The birds would spastically rocket off in all directions whenever anyone came near their cages. Guzmán suggested I stand back a few steps in order to not freak them out. But their eggs were as gloriously unique as any I will ever see: a blinged-out purple chocolaty color, kind of like glossy Easter eggs, their surfaces almost mirrorlike. They were more resplendent than any of the eggs in Claude’s collection.

“Nobody really knows why their eggs are so decorative,” Guzmán explained. It may have something to do with the fact that the male tinamous both incubate the eggs and raise them without any assistance from the female birds. There’s been speculation that the eggs may be a means of attracting male incubators. Matthei had only one species of tinamou (Nothoprocta perdicaria), but he was hoping to acquire more, including the green-egged elegant crested tinamou (Eudromia elegans). There are forty-seven different species of tinamou, and Matthei wants to crossbreed some of them, to see what sort of eggs will arise.

“The tinamou is a very efficient bird,” he said. “They don’t eat much and each female lays eighty to ninety eggs a year. It’s a good business. And we consider the meat, which is very lean, to be just as important as the eggs.”

Dinner that evening began with tinamou pâté and ended with tinamou egg meringue pie. The main attraction was fire-roasted tinamous, which reminded me of wild quail but with a tougher, more wiry texture. I felt that their eggs were of greater interest than their meat. Fortunately, I’d be learning more about those extraordinary eggs at breakfast.

We drank liters of pipeño, a light-bodied, refreshing red wine that Chileans like to drink cool. At one point, we all gazed up at the Milky Way glimmering in the dark summer sky above. To me, it looked just like Claude’s sparrow egg at his party all those years ago.

*

The following morning, I met Matthei and Guzmán at their home for breakfast. There was a large bowl full of tinamou eggs looking chocolaty and reflective in the early morning light. I picked one up; it almost seemed like it was made of plastic. “They aren’t hard to crack,” Guzmán assured me.

When I broke one into a bowl, I noticed that the egg white had a slightly pink, coral hue. “That pink color indicates that it is high in iron,” Matthei explained. “These eggs are also rich in a protein called ovotransferrin—twenty percent more than chicken eggs. In fact, it has more of everything good than other eggs. It’s healthier, more beautiful, and lighter, yet even more delicious.”

We tried the eggs in a variety of ways; all of them were good. The boiled eggs retained their delicate pink color, while scrambled tinamou eggs tasted pretty much identical to regular scrambled eggs, perhaps a tad creamier. The yolk in a fried egg was denser than a normal egg yolk, as though thickened with its own natural custard. It had a bit of a duck egg vibe, but less assertive—better.

“If you like eggs, you will like tinamou,” summarized Matthei.

I like eggs, so I liked tinamou eggs. A lot. If I could bend destiny, a tinamou egg is the egg I’d have as my everyday morning egg. While we finished our coffees, I thought again of my landlord Claude, and what my life was like back then. So many things had changed, and there was still so much more to come.

The EGGS We EAT

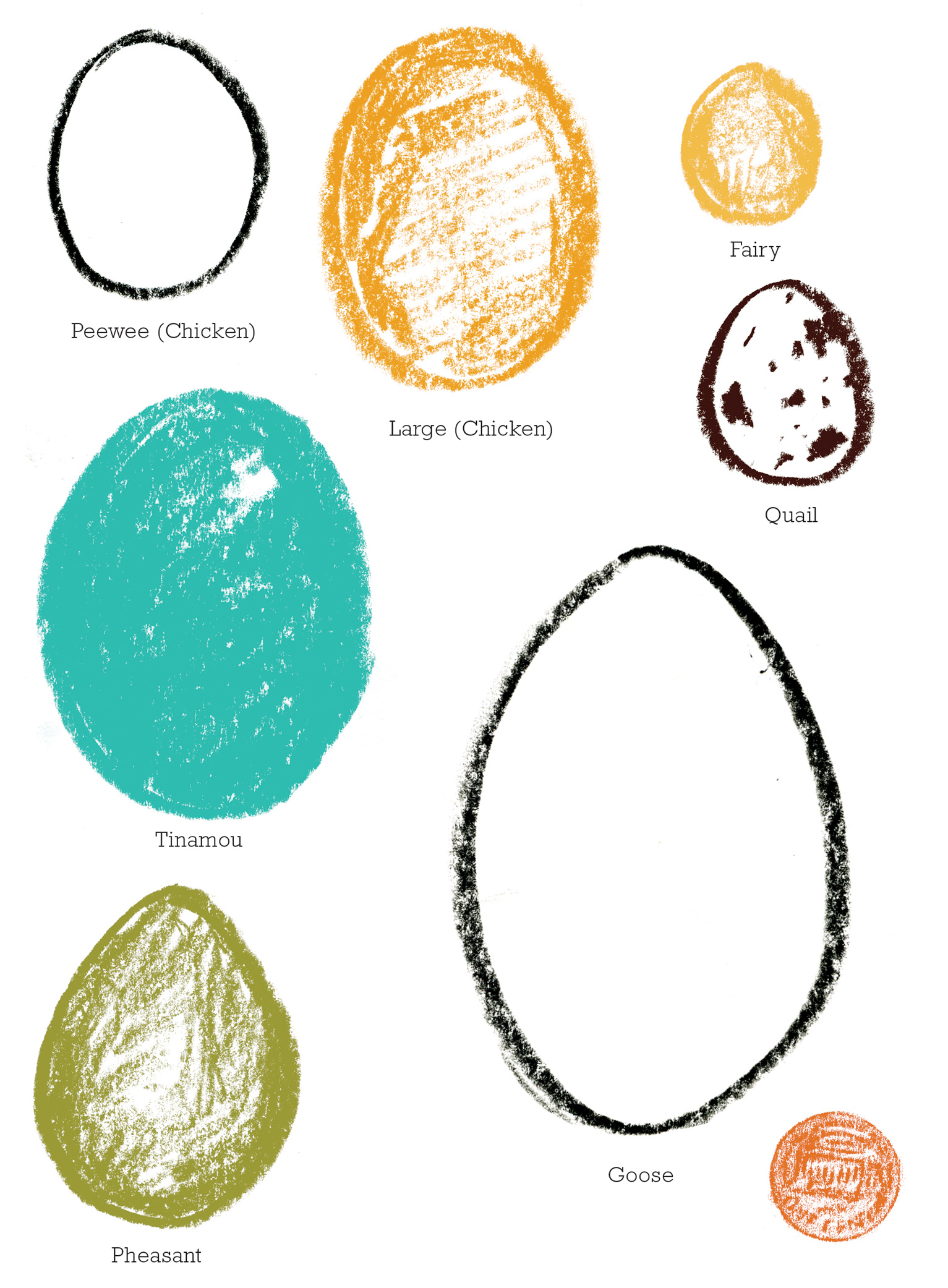

Fairy

This is a yolkless chicken egg, often laid by a young hen. Usually it has a rough shell. (Also called witch egg, wind egg, and fart egg.) It really spooked people in the olden days. In the 1600s they called these tiny eggs “cock’s eggs,” and believed that they would hatch glittering-eyed monsters called basilisks (especially if you incubated your egg under a toad).

Quail

About 1 inch long and roughly a fifth the size of a large chicken egg, the quail egg is the smallest commercially available egg. They take just three minutes to hard-boil, and two minutes to soft-boil. Gram for gram, quail eggs are more densely nutritious than chicken eggs, with more B vitamins, iron, and zinc. They’re used medicinally in China, and are deep-fried and sold as a street-food snack called kwek kwek in the Philippines (this page).

Chicken

Chicken eggs, the focus of this book, come in an array of sizes depending on many factors, including the hen’s breed and how old she is. Here’s how eggs are classified commercially: peewee (1.25 ounces), small (1.5 ounces), medium (1.75 ounces), large (2 ounces), extra large (2.25 ounces), and jumbo (2.5 ounces).

Pheasant

Pheasant eggs are smaller than average chicken eggs and bigger than quail eggs. The shells are a pretty blue on the inside. The ancient Greeks and Romans used to eat them. A pheasant egg contains more yolk than a chicken egg (nearly twice as much), and tends to be yellower.

Duck

Duck eggs have rich, thick yolks with three times the cholesterol of chicken eggs. Their whites also contain more protein than chicken eggs—which means that they can get fluffier than chicken eggs in meringues (this page) and cakes. People with chicken egg allergies can sometimes eat duck eggs without problems. They’re especially popular in Asia, where they get salted (this page) and preserved (this page).

Turkey

About one and a half times the size of chicken eggs, turkey eggs contain four times the amount of cholesterol. Centuries ago, these freckled eggs used to be more commonly eaten: Native Americans gathered eggs from wild turkeys; Europeans brought turkeys over to their continent in the sixteenth century, and a seventeenth-century English cookbook writer called the eggs “exceeding wholesome to eate.” Delmonico’s served them in omelets in the nineteenth century. They’ve waned in popularity, probably because of their cost in comparison to chicken eggs: Turkeys lay about one hundred eggs a year—a lot fewer than an average chicken’s three hundred—and usually sell for $2 to $3 each.

Goose

Goose eggs clock in larger than duck eggs, almost triple the size of jumbo chicken eggs. Like duck eggs they have big, deeply orange yolks, and are prized for their richness. Golden or otherwise, goose eggs aren’t super available—probably because geese lay only about forty eggs per year, mostly in the spring.

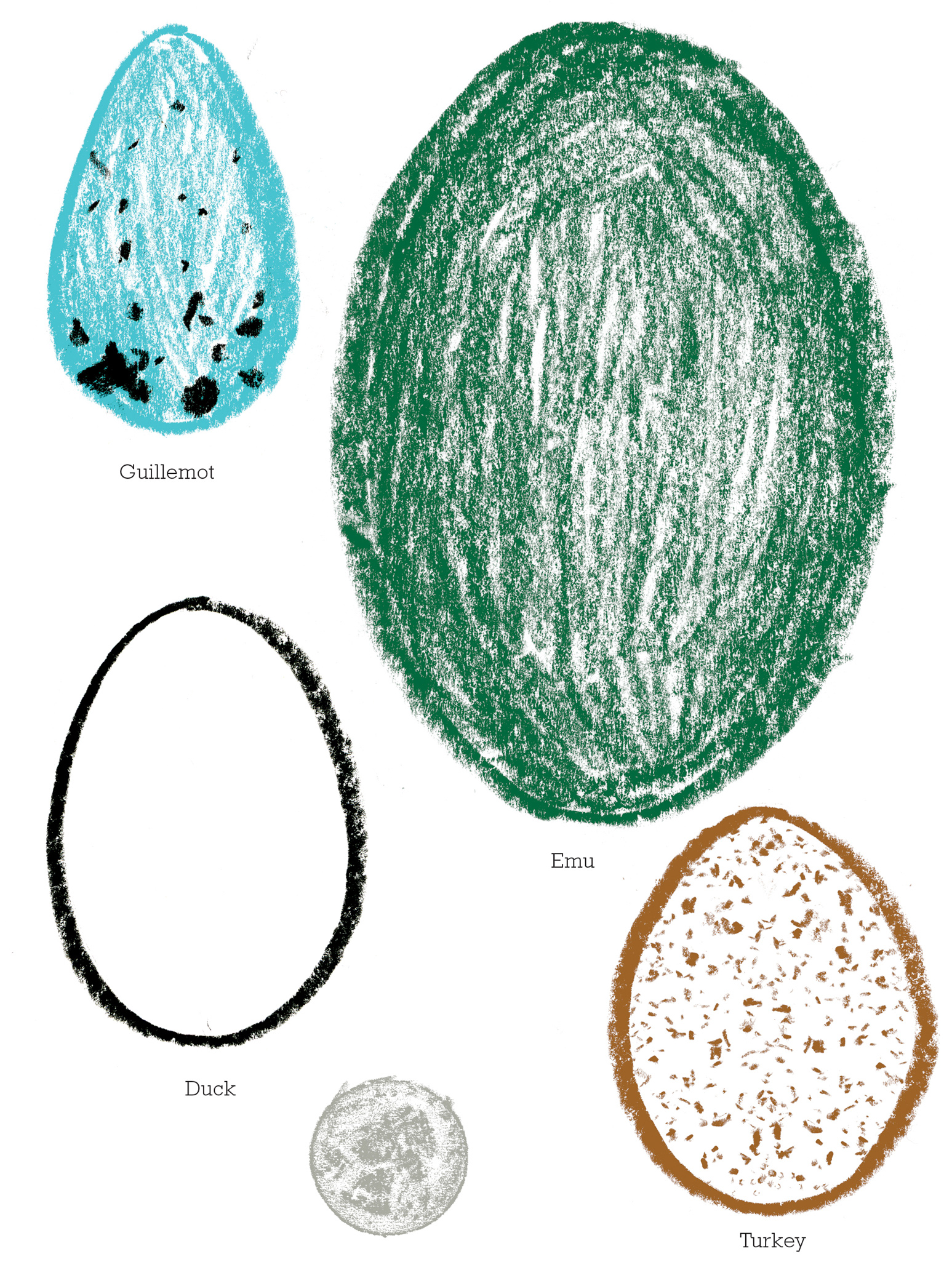

Emu

Emus, native to Australia, are the second-largest living bird—second only to the ostrich—and their emerald green eggs weigh two pounds a pop. Each one is about the equivalent of a dozen jumbo chicken eggs. But they’re milder than chicken eggs and have a white-to-yolk ratio of one to one.

Ostrich

Ostriches are the largest birds on earth, which means they lay the largest eggs. An ostrich egg is equivalent to two dozen jumbo chicken eggs. The shells are five to ten times thicker than a chicken egg’s, so they don’t break when they’re being incubated (at night by their 300-pound fathers, and during the day by their mothers). To open an ostrich egg, a hacksaw or power drill can help.

Guillemot

Guillemots, seabirds found in the Arctic Circle and the North Pacific and Atlantic oceans, lay conical turquoise eggs. The birds spend their lives mostly at sea, only coming to shore to lay their eggs in the spring, when Icelanders will rappel down cliffs to harvest them (they taste “nothing of the sea,” according to one guillemot egg harvester, but have a different texture from chicken eggs). These eggs get laid directly on the bare rock ledges, in large colonies without nests, so each female’s egg has distinct markings. Their pointy shape means that, if disturbed, the eggs won’t roll off the cliffs, but will roll in a circle instead.

Tinamou

Tinamous, found in Mexico, South America, and Central America, lay eggs that are brilliantly colored, glossy, and iridescent. We aren’t sure why they’re so beautiful, but some say it’s to draw the attention of male tinamous, and signal them to incubate the eggs (see this page).

Gull

Historically eaten in England (and, now, restaurants), the eggs of the black-headed gull have mottled shells and orange, creamy yolks. The eggs have a very short season—about three to four weeks in the spring—and are hand-harvested from nests in salt marshes and wetlands. Egg harvesting is highly regulated, and eggers are permitted to take only one egg from each gull’s nest.

Tart to Tart: An EGG TART Evolution

Anna Ling Kaye

My introduction to egg tarts happened in childhood, at family dim sum meals in Hong Kong. After we’d knocked back an array of chicken claws, beef balls, and turnip cakes, I’d get sent to find the dessert lady. Clutching our rectangular dim sum chart, I’d navigate the women pushing heavy carts laden with steaming delicacies till I found the cart with glass shelves for fried foods and plated desserts. There, I’d point at the sun-hearted egg tarts (dan taht), the whole reason for dim sum, as far as I was concerned. The dessert lady would stamp my chart, and I’d parade back to our table victorious. No matter how much we overate at dim sum, there was always extra room for egg tarts, best washed down with earthy and bitter bo lei tea (watered down for us kids).

I have no illusions that I’m alone in my egg tart affinity. (Chris Patten, the last British governor of Hong Kong, was apparently so fond of the pastry he earned the Cantonese nickname “Fatty Patten.”) The most symmetrical of desserts, the Cantonese egg tart is concentric circles of golden shortcrust or puff pastry cradling smooth, bright yellow custard. The secret of the traditional egg tart is lard, which allows the crust to crumble in the mouth and complements the eggy center without overwhelming it. A good Cantonese egg tart has a flat custard that is firm with a gentle give, and its crust brings salty-sweet balance. It is as elemental to a modern Hong Kong childhood as apple pie is to an American one.

So it was a surprise to learn that the pastry is a relatively new export to the Cantonese table. It appeared in Guangzhou bakeries sometime in the first part of the twentieth century, and made its way to Hong Kong tea shops by the 1940s, when it quickly gained menu-must status.

But if the egg tart wasn’t a Hong Kong original, where was it from? Some sources pointed to the English custard tart, which has a similar crust. Then I got wind that in nearby Macau they served a more caramelized version of the egg tart, called the Macanese egg tart, or in Cantonese, the poh taht.

*

Macau is known today as Asia’s casino capital, and to wander there is to navigate flashing neon promising cash and glory, with the accompanying girls in heels and skimpy dresses happy to help you spend your hypothetical earnings. But if you know where to go, you will find yourself seeking a different but arguably far more rewarding treasure: the Macanese egg tart.

My go-to spot lies in the shadow of the golden towers of the legendary Hotel Lisboa. Follow the psychedelically patterned black-and-white cobblestone sidewalk of Avenida de Dom João (the street names and cobblestones are vestiges of recent days as a Portuguese colony), and veer a hard right into a quiet alley. Tucked between a local street-side eatery and a motorcycle parking area, you’ll find a queue of patiently waiting confection fans trailing out the door and halfway around the block. This is how you will identify the Macanese egg tart mecca of Margaret Wong Stow’s Café e Nata.

Café e Nata serves egg tarts fresh out of the oven until they run out, usually by around six p.m., at which point the shutters promptly come down, and any late birds will simply have to try again the next morning.

The Macanese egg tart is a delightfully ugly beast. It’s never symmetrical, always tilting to one side or the other, with black blotches on the crumpled, leathery face of its top, and a layered crust of flaky pastry that falls away to the touch like ancient mummy skin. These are all promising signs: The blotches are caramelized sugar, the leathery face is as crisp as the thinnest of crème brûlée shells, and the crust is airily light with a slight salty kick to it. The savory pastry cradles the heart of this lopsided tart—a rich, smoky custard with far more complexity than its paler, more symmetrical Cantonese cousin.

“Everything has to be handmade,” owner Margaret Wong Stow tells me, as we walk through the small back room where the egg tarts are made. Two women are on pastry duty, cutting long tubes of puff pastry into coins, which they press into the tart tins by thumb. This small-batch treatment, according to Margaret, makes the pastry layered and flakier. The kitchen staff at Café e Nata can be counted off on one hand, but they turn out 165 trays of 45 tarts, or 7,425 tarts daily. “Even if people try to copy us, they can’t,” Margaret says confidently.

Another game changer is Café e Nata’s use of margarine in the pastry dough, not the lard popular in Cantonese egg tarts. The margarine is likely what gives Margaret’s crust its salty finish. The puff pastry is prepared at an off-site factory, where it is chilled for twelve to twenty-four hours before being sent to the in-town bakery. Once the pastry is molded, the trays are shunted over to the custard chef, who prepares and pours the custard filling: made from scratch with egg yolks, cream, milk, and white sugar. Margaret’s daughter, Audrey, offers an important tip for the custard preparation: “You have to dissolve the sugar in the egg yolk in the beginning. And then we add the milk and the cream. Many people use a blowtorch to caramelize the top. We don’t need to.” Café e Nata’s favored custard pouring tool is a repurposed glass coffeemaker pot, which has the perfect handle and spout for mass baking. The tarts are then transferred to a ceiling-high industrial oven kept at a piping-hot 250°C (482°F) all day long, where they are baked for thirty minutes (the high heat creates the hallmark caramelized custard top).

The Macanese egg tart is so iconic it’s a major tourist attraction. But Margaret and Andrew Stow, her husband at the time, baked their first tray of egg tarts in 1990. It’s not that there were no egg tarts available in Macau at the time; they just weren’t widely available commercially. Macau was still a Portuguese colony then, so Margaret, who is Chinese, and Andrew, who is British, decided there was a niche to be explored in serving the sweets to homesick Portuguese, using a recipe Margaret says was passed to them by the governor’s personal chef. Originally a pharmacist, Andrew tinkered with the recipe, switching custard powder for custard made from scratch.

“We took the first tray out from the oven,” Margaret told me, “and the local Chinese people said, No, I don’t want it. It’s burned, it will give you cancer.” They didn’t sell a single tart, and Andrew was ready to throw the whole batch out. Instead, the couple decided to give away their egg tarts for free.

“They had the first bite. Then they had a second one,” Margaret says. “Then they asked me for a third one. And I said, Money, yeah?” Their original bakery, Lord Stow’s, still stands in its original location in the idyllic backwaters of a local neighborhood called Coloane. Margaret opened her own café in 1992 when the couple divorced. Either you’re a Margaret’s customer or a Lord Stow’s customer, and never the twain shall meet. Unless you are Audrey Stow, that is, in which case you stand to ultimately inherit both. Although the bakeries use the same recipe, their suppliers are different, and this, to discerning customers, makes all the difference. When Margaret sold her proprietary recipe to Kentucky Fried Chicken, the Macanese egg tart craze spread to Hong Kong, Taiwan, Singapore, and the Philippines. Lord Stow’s has opened franchises across East Asia.

*

The Cantonese egg tart took off in the 1940s, and the Macanese egg tart with its puff pastry crust only really caught on in the 1990s. They were the innovations. For the original egg tart, I followed the direction pointed by the Macanese egg tart’s Cantonese name: poh taht, or the Portuguese egg tart.

In 1496, at the bidding of Portugal’s King Manuel I, a large monastery was commissioned to be built on the banks of the Tagus River, now known as the neighborhood of Belém on the outskirts of Lisbon. At the turn of the century, this portion of the Tagus was where the great Portuguese explorers such as Vasco da Gama would launch their world-defining voyages. A century later, the monastery was completed, a fantastical structure with spindly turrets studding its length. When the many, many nuns moved into this architectural jewel, there was a sudden spike in the need for egg whites to starch their clothes and wimples, and as a result, an unanticipated surplus of egg yolks. Thus was born a wide array of decadent egg yolk experimentation, the most famous of which is the pastéis de nata, which is easily the Yoda of egg tarts. It has the smallest, gnarliest, lumpiest appearance of the trio, is hundreds of years more ancient, and its flavor profile is immense. Smaller on the palm of the hand than its Macanese or Cantonese kin, the pastéis de nata coddles a creamy, smoked custard, set by high heat, in paper-thin pastry. The result is triumphant balance: The custard is creamy but not eggy, the crust is flaky but not dry, the sweet center delights without cloying. The smallness of the pastéis de nata makes it easy to consume in multiples.

When the Jerónimos Monastery closed in the 1820s because of changing taste in politics and religion, the pastéis bakers struggled to make a living from their egg tarts, which also came to be called pastéis de Belém. In 1837, even these destitute bakers were forced to sell their recipe to a savvy businessman, who began baking the egg tarts in the monastery’s neighboring sugar refinery. He’s kept the recipe in his family ever since, serving tarts out of the Fabrica dos Pastéis de Belém. Here, egg tarts get elevated from a street-side snack to ritual. Waistcoated waiters take your order at small café tables in a beautiful blue-and-white tiled room. The traditional drink pairing for a pastéis de Belém is espresso, served in china cups. The egg tarts arrive fresh out of the oven, their centers still wobbling and steaming. It’s recommended you eat the pastéis in two bites, with a dash of cinnamon (and powdered sugar, for the sweet-toothed).

*

To me, each of the three egg tarts is delicious in its own way. But for a confection with a uniquely global story, my favorite is the smoky-sweet Macanese egg tart, its Portuguese ancestry reimagined and popularized by the experimentations and entrepreneurship of a Chinese woman and a British man.

Yank Sing’s Egg Tart

Hong Kong

Our Hong Kong–style egg tarts have been on our menu since Alice Chan opened Yank Sing in San Francisco in 1958. We’ve adapted it over the years, as customer tastes have evolved to favor a lighter, flakier pastry and a more delicate, silky filling. The ingredients have also changed over time: We’ve replaced shortening with butter. We’re looking for a light, melt-in-the-mouth texture, so we try not to overcook the tarts and use only pasteurized eggs for the filling.

—Nathan Waller

Makes 12 tarts

Puff Pastry

1½ sticks (6 oz) cold butter, cut into 1-inch cubes

1½ cups all-purpose flour, plus more for the work surface

1 egg

2 tbsp water

Egg Custard

1 cup water

½ cup sugar

4 eggs

¼ cup evaporated milk

½ tsp vanilla extract

+ salt

1. Make the puff pastry: Mix the butter and ¾ cup of the flour together to form an “oil dough.” Knead the dough into a ball, wrap in plastic, and refrigerate for 20 minutes.

2. Meanwhile, mix the egg and water into the remaining ¾ cup flour to form a “water dough.” Knead the dough into a ball, wrap in plastic, and refrigerate for 20 minutes.

3. Flour a work surface and remove the water dough from the refrigerator. Roll the dough out into a large square, about 11 × 11 inches.

4. Take the oil dough out of the refrigerator and spread it out on top of the water dough, leaving a large enough border of the water dough to be able to fold over the oil dough entirely. Fold the sides of the water dough over the oil dough.

5. Roll the entire dough out to a large square, again aiming for about 11 × 11 inches, and mark it into thirds. Fold each outer third over the center third and roll the folded rectangle out into a large square again. Repeat two more times.

6. After the third fold, roll out the dough again and this time mark it into fourths. Fold each outer quarter into the center and then roll the rectangle out. Wrap the dough in plastic and place in the refrigerator for at least 20 minutes.

7. On a lightly floured work surface, roll out to a ¼-inch thickness. Cut out disk shapes with a round cutter.

8. Lightly grease the inside of 12 fluted tart molds and press the pastry disks into the molds. Transfer to the refrigerator while you make the filling.

9. Make the custard: Combine the water and sugar in a saucepan and heat over medium heat until the sugar dissolves, 3 to 5 minutes. Remove the pan from the heat and cool.

10. When the sugar syrup has cooled, whisk the eggs into the sugar syrup. Stir in the evaporated milk, vanilla, and a pinch of salt. Strain the mixture through a fine-mesh strainer into a container with a pouring lip.

11. Heat the oven to 350°F.

12. Fill each of the pastry-lined tart molds three-quarters of the way up with egg custard.

13. Position the tarts evenly on a baking sheet and place in the oven. Bake until the crust is golden brown and the filling raises to a slight dome, about 45 minutes. Remove from the oven and leave to cool for 5 to 10 minutes, then carefully tap the molds to remove the tarts.

White-Winged Dove

South America: Put an Egg IN It!

Naomi Tomky

Latin Americans not only “put an egg on it,” they also put their eggs in things. When stuffed inside meat, dough, or vegetables, hard-boiled eggs serve a multitude of purposes: helping to stretch expensive ingredients, and adding texture and luxurious flavor. (Plus, they look cool.)

Empanadas

Filling-stuffed dough has infinite variations across the continent, from the dough (wheat, corn, yuca, or plantain) to the filling, but in many countries—particularly those of the Cono Sur—hard-boiled eggs play a key role.

In Argentina, where empanadas are daily bread, the prototypical version is stuffed with ground beef, onions, olives, and hard-boiled egg, the addition of which seems like plain common sense: Eggs are way cheaper than beef and transform the filling into something more complex. In Chile, that egg-and-beef mixture gets combined with raisins and is called pino; in Bolivia, it’s part of the soup dumpling–esque salteñas. Farther north, Nicaraguan pastelitos come with a pork or chicken filling, are highly seasoned with a tomatoey sauce, spices, olives, capers, and chopped eggs, then fried and rolled in sugar. Guatemalan empanadas are made with pork, almonds, sweet spices, and chopped eggs.

Pastel de Choclo

The Chilean pastel de choclo is a sort of luxurious corn pudding. A favorite home-cooked casserole in Chile, it combines the colonial-influenced meat filling as a bottom layer and the indigenous corn, caramelized in the oven on top, segregated by slices of hard-boiled egg. In other parts of Latin America, similar meaty casseroles are made with beaten eggs and local starches, like yuca or plantain in the Dominican Republic and Puerto Rico, where they’re called pastelones.

Torta Pascualina

Because roughly 60 percent of Argentineans are of Italian ancestry, Argentina has happily inherited the traditions of these immigrants (try walking five blocks in Buenos Aires without running into a slice of pizza). One of the more directly adapted dishes is Easter pie—torta pascualina. Beneath a puff pastry crust, a dense filling of greens and ricotta cheese houses whole eggs, making a rich vegetarian dish perfect for Lent, as well as quite the visual spectacle when sliced. From inches of solid green peek sunny yellow yolks, bordered by white.

Matambre

Matambre is Argentinean steak stuffed with vegetables and eggs, and means, in Spanish, “hunger killer.” Served warm as an entree or cold as an appetizer, it’s a butterflied flank steak lined with vegetables and hard-boiled eggs. Rolled and pinned, it’s cooked either by braising in red wine or on the grill, and then sliced so that each cross-section is a beautiful pinwheel slice of meat, vegetable, and squished-up hard-boiled egg.

Matambre

Scotch Eggs

England

A Scotch egg is a boiled egg coated with meat and bread crumbs—a spherical and portable snack with a yolk at its core. But why? To what end? Whose idea was it?

The story everyone tends to run with is that the Scotch egg comes from the fancy London department store Fortnum & Mason. They like to take full responsibility for the Scotch egg. They claim that in 1738 London’s wealthy travelers demanded it for their long and arduous carriage rides. Around that time, so the story goes, Fortnum & Mason had a special kitchen that produced pies, cakes, and breads for travelers. The Scotch egg would have come out of that kitchen. (Other items designed by the kitchen included a meat lozenge, which is like a big fruit pastille, but meat—a protein hit for travelers, sportsmen, and MPs on all-night parliamentary sittings.)

“We had been supplying travelers’ baskets for some time,” says Dr. Andrea Tanner, the store’s archivist. “The Scotch egg was most likely a natural progression, based on the perceived demands of the travelers. It is a compact snack that required no cutlery, and could be transported easily—even in a pocket, wrapped in a handkerchief.”

Back then, the egg would have come from a pullet—a young hen, which isn’t really in the business of laying proper eggs yet—and would have been much smaller than eggs are now. The covering would have been made from forcemeat (lean meat, ground up and bound with fat) rather than the sausage we use these days. It would’ve been heavily seasoned with pepper and mace.

But no chef creates meat-covered egg balls in isolation. Anonymous must have taken inspiration from somewhere. A search of Victorian cookbooks reveals numerous receipts for egg balls—hard-boiled eggs, put through a sieve, mixed with parsley, flour, cayenne pepper, and raw egg, rolled into balls and re-boiled—and forcemeat balls: veal, pounded through a sieve, mixed with butter, bread crumbs, parsley, shallots, and egg, rolled into balls and boiled. In The English Art of Cookery, According to the Present Practice (1788), Richard Briggs writes, “In almost every made dish you may put in what you think proper, to enlarge it and make it good; such as sweetbreads, ox palates boiled tender…force-meat balls, egg balls.” The Scotch egg was the Cronut of the eighteenth century: a hybrid ball.

These days, Scotch eggs are pub snacks. And in that context, they are perfect. I’m not sure I’d ever eat one like a hand fruit on the bus, or on a horse-and-cart ride to my house in the country (I’d get crumbs on my bustle!). But cut in half, fresh from the fryer, egg yolk gently relenting, they are beautiful.

Michael Harrison, head chef of the Cornwall Project, which brings produce up to London from Cornwall and turns it into perfect pub food, talked us through his basic Scotch egg formula, which is infinitely adaptable.

—Laura Goodman

Makes 10 Scotch eggs

2 lb breakfast sausage, casings removed if links

+ salt

10 eggs, at room temperature, plus 2 eggs, beaten

+ extra-virgin olive oil

⅓ cup whole milk

1 cup panko bread crumbs

1 cup rolled oats

2 cups all-purpose flour

+ neutral oil, for deep-frying

+ sea salt

1. Divide the sausage meat into 10 balls (about 3.25 oz each). Chill them.

2. Bring a large pan of water to a boil. Add salt until it starts to taste unpleasantly salty. Have a timer ready to count down 5 minutes 35 seconds. Half-fill a same-size container with ice, water, and salt. When the water is boiling, take the 10 eggs and dip them into the boiling water with a slotted spoon—dip once, twice, and then gently lower them in and start the timer. The water must keep boiling vigorously. At the end, drop them into the ice bath and let them sit for 10 minutes. Peel them carefully, as they’re soft inside. Dry the eggs and chill them.

3. Rub your hands with a thin film of extra-virgin olive oil. Press a ball of meat flat onto your hand, so that it’s about ⅓ inch thick.

4. Place the egg in the middle and wrap the egg with the meat. Pinch the edges together and smooth the ball so that there are no gaps or bumps. (If the covering isn’t even, the Scotch egg will split during cooking.) If you’re struggling with the wrapping of the egg, try covering your work surface with oiled plastic wrap and pressing the balls flat on that, rather than on your hand.

5. Beat together the remaining 2 eggs and the milk in a shallow bowl. In a second shallow bowl, combine the panko and oats. Dredge the balls in the flour. Roll them in the milk-egg mixture, then in the panko-oat combo. (I use panko for texture and stability, mixed with oats for presentation and crunch.)

6. Heat the oven (preferably convection) to 350°F.

7. Heat the oil in a deep fryer to 350°F.

8. Deep-fry the eggs in batches for 1 minute, then bake them in the oven until the sausage is cooked through (firm to the touch and 160°F), about 10 minutes.

9. Serve them straight away (or the eggs will keep cooking). Season the yolk with a good sea salt (preferably Cornish!). I finish mine with cracked green pepper and sliced celery leaf. Lots of condiments work. I use brown sauce flavored with wildflower honey and Cornish ale. If you’d rather serve them cold, take them out of the oven after 8 minutes and the yolk will still be runny.

India does it, too! Northern India is home to the nargisi kofta, a deep-fried meatball with a hard-boiled egg inside, served with curry.

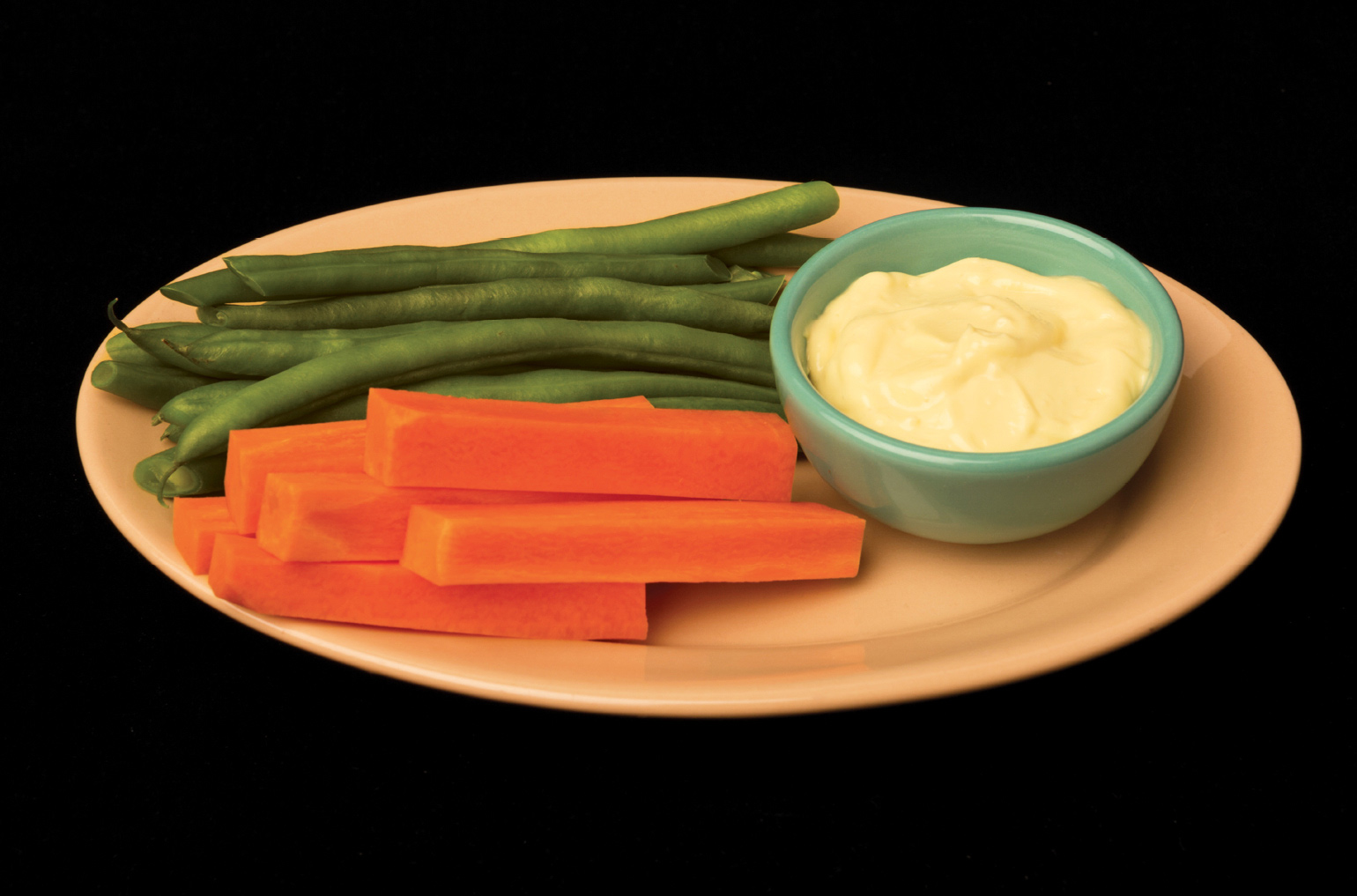

Aioli

France

Hunger is the best sauce, yes, but aioli is second best—homey and luxurious, the perfect eggy emulsion. In the villages throughout the Provençal region of Var, shops serve it with their salt cod on Fridays. In Solliès-Toucas, aioli and salt cod get served with boiled potatoes, carrots, and snails. Throughout Provence, summer festivals serve aïoli monstre on their final day: Village populations turn out to watch fireworks, fill their plates with cod, potatoes, carrots, green beans, artichokes, chickpeas, beets, hard-boiled eggs, snails, and squid stew, and top it all with a generous cap of aioli. In that spirit, put this aioli wherever you want an alluringly garlicky condiment: on vegetables raw or boiled, on fish, in sandwiches instead of mayo. Traditionally it’s made start to finish by hand—in a mortar and pestle—but I am impatient, so I do just the mashing-garlic part in the mortar and pestle, and the rest in the food processor.

Makes 1 cup

2 garlic cloves

+ salt

1 egg yolk, at room temperature

a few drops water

¼ cup canola oil

½ cup extra-virgin olive oil

1 tbsp fresh lemon juice

1. Pound the garlic cloves with a big pinch of salt in a mortar and pestle until they’re a paste. Set aside.

2. Slide the egg yolk into a blender or mini food processor and blend. Add a few drops of water from your fingers and ¼ teaspoon salt. Add a few drops of canola oil, and run the processor. Glug more canola oil in with the food processor running, then the olive oil. You’ll see the emulsion start to take when the food processor starts to get louder, and the oil will turn from clear to opaque. Add more drops of water if the mixture becomes too thick or looks like it may break.

3. Once the aioli is emulsified and thickened, stop the machine. Taste. Add more salt to taste. When it’s salty to your liking, add the garlic paste and the lemon juice. If the aioli breaks or doesn’t emulsify, start over with a new egg yolk and use the broken mixture in place of the oil.

Great Blue Heron

Egg Curry

India

This is a recipe my mom would make when there was little else on hand and she had yet to go to the store. It’s a great recipe for a hangover or when you’re feeling lazy or both. Some people quarter the eggs so the yolks fall apart and make the sauce thicker, but I find that too muddled. Others throw in some boiled and peeled baby potatoes too. We used to make this dish when we had unexpected guests to feed and it never disappointed. I love the fiery tomato sauce and like to sop it up with whole pieces of toast.

—Padma Lakshmi

Makes 4 servings

2 to 3 tbsp butter

1 tsp cumin seeds

3 whole cloves

1 pod black cardamom

1 cup diced red onion

1 tbsp chopped fresh ginger

2 garlic cloves, minced

2 or 3 fresh bay leaves

2 to 3 serrano chilies, seeded and sliced

½ cup diced green bell pepper

1 tsp garam masala

½ tsp amchoor (optional)

4 cups chopped tomatoes

¼ cup water

+ salt

1 cup yogurt

+ crushed black pepper

8 hard-boiled eggs (this page), peeled

2 tbsp fresh lime juice

2 slices sourdough toast, cubed into croutons

1 cup cilantro, roughly chopped

+ rice or rotis, for serving

1. Melt the butter in a deep skillet over medium heat until just slightly browned, about 2 minutes. Add the cumin, cloves, and black cardamom and stir until fragrant, 1 to 2 minutes.

2. Add the onion, ginger, garlic, bay leaves, chilies, and bell pepper. Stir and sauté until the onions are glassy, about 5 minutes.

3. Add the garam masala and amchoor (if using) and stir until the spices begin to darken slightly, about 3 minutes.

4. Add the tomatoes, water, and salt to taste. Stir, cover, and cook for 5 to 7 minutes more.

5. In a small bowl, whip the yogurt with a fork until runs a bit thin. Season with salt and black pepper.

6. Stir the tomato gravy, adding a bit more water if needed. Add the whole boiled eggs to the skillet, gently nestling them into the tomato gravy, and pouring some over the eggs to cover them. Cover and cook for 5 to 7 more minutes.

7. Remove from the heat and stir in the lime juice. Transfer the egg curry to a serving dish. Drizzle the yogurt evenly all over and then garnish on top with the croutons and cilantro.

8. Serve with rice or rotis.

Egg Hoppers

Sri Lanka

In Sri Lanka, curry is a given at just about every meal—what changes is the starch with which you eat it. At breakfast it’s often the incredible bowl-shaped, egg-cuddling rice-flour crepe called a hopper, or appa, which means “rice cake” in Tamil. Hoppers are also eaten in southern India, but on this neighboring island they reach their culinary destiny—served as a common breakfast and occasional dinner.

Anchored by the twin pillar ingredients of Sri Lankan cuisine, rice (in flour form) and coconut (in milk form), hoppers combine a fun shape with a sourdoughesque zing. They come either sweet or savory, and can be eaten with any type of curry or condiment. But the best of them have an egg dropped in the center and fused to the bottom of the pancake (ideally with the yolk still runny).

At the open-air food stalls of Sri Lanka, cooks—often shirtless and sarong clad—expertly swirl the lightly fermented batter of rice flour and coconut milk in pans made specifically for hoppers. They look like tiny woks. Swirling the batter along the sides of the hot pan forms crisp, lacy edges. An egg gets cracked directly into the center, cooking with the pancake. After a few minutes, the edges of the pancake brown and curl away from the pan and the whole bowl-shaped breakfast slides out with ease, ready to be dolloped with lunu miris—the local sambal (spicy condiment)—and dipped in whatever curry gravy is lying around.

Because appachatti (hopper pans) aren’t easy to track down outside the subcontinent (nor is toddy, the local palm wine used to ferment the pancakes), it takes some improvisation to make these at home. Subbing in a small wok or a pan with gently sloping sides, it’s possible to make a pretty decent copycat.

—Naomi Tomky

Makes 6 hoppers

½ tsp active dry yeast

½ cup plus 2 tbsp warm water

1 cup rice flour

¼ tsp salt

¼ tsp sugar

1¼ cups coconut milk

⅛ tsp baking soda

1 tbsp neutral oil

6 eggs

+ curry, sambal, or hot sauce, for serving

1. Dissolve the yeast in the warm water and let it sit for a few minutes, until active.

2. Mix together the rice flour, salt, and sugar in a large bowl. Add the yeast mixture and stir the batter until smooth.

3. Cover the batter and leave in a warm spot for 2 to 3 hours (many recipes call for “room temperature,” but be advised that room temperature in Sri Lanka is often over 90°F).

4. Stir in the coconut milk, re-cover, and return to the warm spot for an additional hour. After the hour has elapsed, add the baking soda.

5. Heat a hopper pan, small wok, or omelet pan over medium-high heat. If you are using an omelet pan, roll the pan around over the burner, making sure that all the pan’s sides and bottom are quite hot. Very lightly oil the pan. This is best done with an oil mister or pastry brush, as the oil needs to cover both the bottom and sides, and too much oil will make the hoppers greasy.

6. Ladle about ¼ cup of the batter into the bottom of the pan, then immediately begin to roll the pan, swirling it around so that the batter climbs up the sides of the pan. Keep doing this until there is no batter left swirling and it is in a thin layer all over the inside of the pan (including the sides). Crack an egg into the center. Cover the pan immediately and leave to cook for 3 to 4 minutes.

7. When you lift the lid to check on it, the top edges should be browned and crisp, starting to pull away from the edges, and the white of the egg should be cooked through. If so, use a spatula to gently separate the pancake from the pan. If it’s sticking, it may need a little bit more time over the heat.

8. Slide the pancake onto a plate and repeat with the remaining batter and eggs.

9. Serve right away, with curry or sambal. If you don’t have or don’t want to make curry, a spoonful of any good hot sauce is a more than worthy accompaniment.

Common Loon

Shakshuka

Middle East & Africa

Algeria, Israel, Morocco, Saudi Arabia, Libya, Yemen…People in lots of places eat shakshuka, eggs poached in peppery tomato sauce. (In Italy there’s uova in purgatorio, or eggs in purgatory; Mexico does it, too! See opposite.) It’s popular for obvious reasons—it’s delicious. But one theory goes that once upon a time in the Ottoman Empire, there was a meze called saksuka—an eggless meat-and-vegetable stew. In Maghreb, the Jewish population turned saksuka into shakshuka: a meatless dish, with eggs. Here’s a not-at-all-traditional one I like to make, adapted from cookbook author David Lebovitz’s inspired recipe.

Makes 4 servings

3 tbsp olive oil

1 yellow onion, chopped

1 green bell pepper, chopped

1 serrano chili, chopped

1½ tsp salt

4 garlic cloves, minced

½ tsp freshly ground black pepper

1 tsp caraway seeds, crushed

1 tsp paprika

1 tsp ground cumin

⅛ tsp cayenne pepper

1 can (28 oz) whole tomatoes

2 tbsp tomato paste

2 tsp honey

1 tsp red wine vinegar

½ cup water

1 cup chopped kale or chard

¼ cup feta cheese or whole-milk yogurt

4 eggs (preferably cracked into ramekins)

1 tbsp chopped parsley

+ bread or toast, for serving

1. Heat the olive oil in a large skillet over medium heat. Add the onion, bell pepper, serrano, and ½ teaspoon of the salt. Cook until soft, about 8 minutes. Add the garlic, black pepper, caraway, paprika, cumin, and cayenne. Cook, stirring so nothing sticks, until fragrant, another 2 to 3 minutes.

2. Break up the whole tomatoes and add them, along with all their juices, to the pan. Stir in the tomato paste, honey, vinegar, water, and remaining 1 teaspoon salt. Reduce the heat to medium-low and simmer until the sauce has thickened, 12 to 15 minutes. Stir in the kale or chard and remove from the heat. If you’re using feta (and not yogurt), mix it in at this point.

3. Make 4 indentations in the sauce with the back of a big spoon and slide each egg into its own well. Use a fork to intermingle the whites with the sauce a little. Turn the heat back on, to low, so the sauce is at a gentle simmer, and cook until the whites turn opaque around the sides and middle, 7 to 8 minutes. Cover the pan and cook until the whites are fully opaque but the yolks are still runny, about 3 more minutes.

4. Remove from the heat and sprinkle the parsley all over. Serve with bread or toast, and the yogurt if you opted out of the feta.

Huevos en Rabo de Mestiza

Mexico does it, too!

“This is the perfect thing in the summer when tomatoes and chilies are at their peak,” says Karen Taylor, the chef and owner of El Molino Central in Sonoma, California, of huevos en rabo de mestiza. “But it needs a new name.”

The translations for rabo de mestiza are as colorful as the dish itself: from “tattered clothing of a mixed-race girl” to “a whore’s ass.” (Mestiza was a term ascribed to the daughter of a Mexican and a Spaniard in the colonial era.)

Thought to have originated in the Central Mexico state of San Luis Potosí, a peasant dish of eggs poached in spicy tomato sauce à la shakshuka and Italian eggs in purgatory, huevos en rabo de mestiza is now a popular brunch dish throughout Mexico. Some variations call for hard-boiled eggs instead of poaching the eggs directly in the sauce, but traditional chefs do not always approve. This is Karen Taylor’s recipe.

—Aralyn Beaumont

Makes 4 servings

3 tomatoes

2 serrano chilies

1 tbsp salt

4 poblano chilies

¼ cup olive oil

1 small white onion, sliced into thin half-moons

2 epazote sprigs

1½ cups chicken stock

8 eggs

8 thin slices queso fresco

1. Fill a medium saucepan with water and bring to a boil over medium heat. Add the tomatoes and serrano chilies and boil for 5 minutes.

2. Remove the tomatoes and chilies from the water and place on a plate lined with paper towels. When they’re cool enough to handle, place them in a blender or food processor and add the salt. Blend until smooth.

3. Char the poblanos over a gas flame or under the broiler, then put them in a plastic bag. Once cool enough to handle, peel the poblanos and slice them into thin strips.

4. Heat the olive oil in a large saucepan over medium heat. Add the poblanos and onion and sauté until softened, 10 to 12 minutes. Add the puréed tomato-serrano mixture and the epazote, and cook for 10 to 15 minutes. Add the chicken stock and cook 5 minutes more.

5. Working with one at a time, crack an egg into a small bowl and slide it into the tomato-chili sauce. Try not to crowd them.

6. Cover the pan and cook the eggs until they’re halfway done, about 5 minutes.

7. Add the slices of queso fresco, cover, and cook until the eggs are set and the cheese is melted, 5 to 7 minutes. Serve right away.

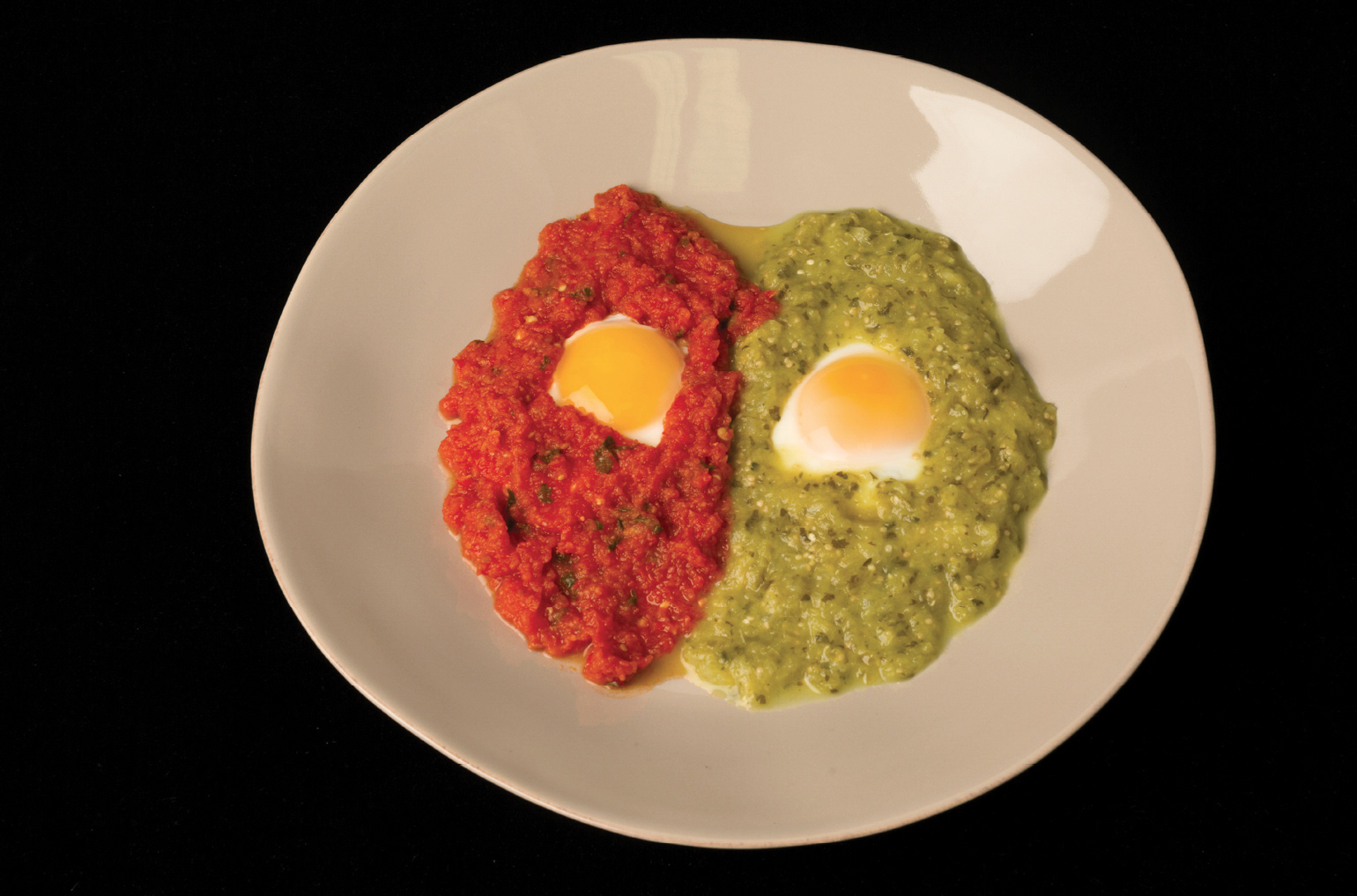

Huevos Divorciados

Mexico

In Mexico, we regularly eat eggs for breakfast, preparing them in many different ways with various sauces—spicy red and green tomato sauces being the most common. Huevos divorciados is two fried eggs, each topped with one of the sauces. You get a dish that is half red and half green, which inspired the name “divorciados,” because we usually eat fried eggs with just one sauce in Mexico. The dish is generally accompanied with refried beans, though some people will ask for chilaquiles on the side. Chilaquiles turn green, red, or black, depending on the sauce used. This is the recipe of my mom, Titita Ramírez Degollado—it’s very popular at our restaurants.

—Raúl Ramírez Degollado

Makes 1 plato

¼ cup Salsa Roja (recipe follows)

¼ cup Salsa Verde (recipe follows)

+ refried beans and/or chilaquiles, for serving

1. Place the fried eggs next to each other on a plate. Top one egg with the salsa roja and the other with the salsa verde.

2. Serve with refried beans and/or chilaquiles.

Salsa Roja

Makes 4 cups

4 garlic cloves

½ medium onion, chopped

1 tbsp vegetable oil

2 jalapeño chilies, chopped

2 lb plum tomatoes or 1 can (28 oz) whole tomatoes

1 small bunch epazote, finely chopped, or ½ cup chopped cilantro

1 tsp salt

1. Place the garlic and onion in a blender or food processor and blend until smooth.

2. Heat the oil in a medium pot over medium-low heat. Add the blended garlic and onion, reduce the heat, and simmer for 15 minutes, stirring occasionally.

3. Working in batches if necessary, add the jalapeños and tomatoes to the blender and blend until smooth. Add the mixture to the simmering pot along with the epazote, mix to combine, and let simmer for 45 minutes, stirring occasionally. Stir in the salt and let cool.

Salsa Verde

Makes 4 cups

3 tbsp vegetable oil

½ medium onion, finely chopped

2 lb green tomatoes or tomatillos, husked

2 jalapeño chilies

½ cup roughly chopped cilantro

+ salt

1. Make a sofrito de cebolla: Heat 2 tablespoons of the oil in a medium skillet over medium-low heat. Add the onion and sauté until soft and translucent, about 15 minutes. Remove from the heat and set aside.

2. Place the tomatoes and jalapeños in a medium pot and fill with water to cover. Set the pot over high heat, bring the water to a rapid boil, then drain the tomatoes and jalapeños and leave to cool.

3. Once cooled, stem the jalapeños. Working in batches if necessary, place the tomatoes, jalapeños, and sofrito de cebolla in a blender or food processor and blend until smooth.

4. Add the remaining 1 tablespoon oil to the drained pot and heat over medium-high heat. Pour all but a few tablespoons of the tomato mixture into the pot and bring to a light boil.

5. Meanwhile, add the cilantro to the blender. Blend with the remaining sauce into a smooth paste.

6. Before the salsa starts to boil rapidly, add the cilantro paste and mix to combine. Once the salsa is at a full boil, add 1 teaspoon salt and cook for 2 minutes. Remove from the heat, season with more salt if necessary, and chill the salsa before serving.

Brown Pelican

Spaghetti alla Carbonara

Italy

This is pasta that’s been made with egg and sauced in egg, so it was more or less mandatory in this egg book. Carbone, Italy, has nothing to do with carbonara—this is a Roman dish. It’s possible that carbonara did come from a restaurant called La Carbonara in Rome, but we can’t be 100 percent sure. What we do know is that carbonara (a spaghetti dish that’s finished with a mixture of beaten eggs, pecorino, and bacon or guanciale or pancetta) didn’t become internationally popular until after World War II. Historians speculate that the original pasta carbonara was a modernized version made by food-strapped cooks with leftover American war rations (in which bacon and powdered egg yolks would have been bountiful). The original was a dish endemic to central and southern Italy, and consisted, simply, of pasta dressed with melted lard and beaten eggs and cheese. Carbonara is simple to put together—provided you temper the eggs, warming them up with the pasta water a little at a time so they don’t curdle—and best eaten within a few minutes of cooking.

Makes 4 servings

4 oz guanciale, finely diced

+ salt

12 oz spaghetti

2 eggs

2 egg yolks

1 cup finely grated pecorino cheese

1 tsp freshly ground black pepper

1. Place the guanciale in a large cold skillet and set over medium heat. Cook, stirring often, until the guanciale is crisp and rendered, about 12 minutes. Remove the meat to a bowl and reserve the drippings.

2. Bring a large pot of water to a boil, salt it well, then add the spaghetti. Cook until al dente, 8 to 10 minutes.

3. Meanwhile, whisk the whole eggs and the yolks, pecorino, pepper, and 3 tablespoons of the guanciale drippings together in a large heatproof bowl. Gradually temper the mixture with ⅓ cup pasta water. Reserve in a warm spot.

4. When the spaghetti is al dente, lift it with tongs from the pot directly into the bowl with the egg mixture, and toss it vigorously in the sauce until the sauce thickens and clings to the noodles, about 30 seconds, adding splashes of pasta water if necessary. Add the guanciale and toss again.

5. Divide among four warm bowls and serve immediately.

Uitsmijter

Netherlands

Uitsmijter, pronounced outs-my-ter, means “out-thrower” in Dutch. As in the person who kicks you out of the bar when you’ve had a few too many Heinekens—the bouncer. How this egg-and-bread dish came to be named is unknown, but it probably has something to do with the fact that uitsmijter is Holland’s national late-night food. After a long night of drinking, you might order an uitsmijter at the bar or at a nearby eetcafé (literally “eating café”) to soak up all that booze. Cheap, hot, and easy to make, uitsmijter is also what you serve your friends after a house party. My cousin Martijn subsisted solely on uitsmijters during his first year of college, when he lived in a frat house overlooking one of Leiden’s famous canals.

The thing about uitsmijter is that it allows Dutch ingredients—creamy butter, fantastic cheese, and really fresh bread—to shine. Although the fresh produce of this gray, soggy nation isn’t anything to write home about, iconic Holstein cows turn rain-soaked grass into delicious butter and cheese. The very best cheese for uitsmijter is the creamy-yet-sliceable jonge (young, aged about four weeks) boerenkaas (farmers’ cheese), an EU-protected designation that ensures the cheese was produced with raw milk that came from the same farm where it was aged. But if you can’t find boerenkaas, it’s fine to use gouda or any other semi-firm cheese available.

Although high-quality cheese and bread will enhance your uitsmijter experience, they’re not necessary at all: Uitsmijter is the great leveler. Simple enough to make while hung over (or still drunk) and composed of things most folks have in the fridge, it’s satisfying every time.

—Sascha Bos

Makes 1 serving

1 tbsp butter

2 eggs

2 oz semi-firm cheese, such as gouda, sliced

2 slices ham

2 slices white or whole-wheat sandwich bread, lightly toasted

+ salt and freshly ground black pepper

1. Melt the butter in a medium skillet over medium-high heat. Gently crack the eggs into the foaming melted butter and fry until the white is almost set and the yolk is still quite runny—just a bit less cooked than you like your sunny-side-up eggs—about 2 minutes. It’s okay if the whites merge together to form one super-egg. Reduce the heat.

2. Arrange the cheese slices over the whites of the eggs, tearing to fit around the yolk. Cover the skillet, and allow the cheese to melt. When fully melted, remove from the heat.

3. Place a slice of ham on each piece of toast and top with a cheesy egg. Season with salt and pepper. Eat immediately.