Chapter Nine

The New Deal and Reciprocal Trade Agreements, 1932–1943

The Great Depression produced a major political realignment in favor of the Democrats, who brought about a historic transformation in US trade policy. In 1934, at the request of the Roosevelt administration, Congress enacted the Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act (RTAA) which authorized the president to reduce import duties in trade agreements negotiated with other countries. In making an unprecedented grant of power to the executive, the RTAA changed the process of trade policymaking and put import duties on a downward path. This chapter explains how such a radical change was possible just a few years after Congress enacted high duties in the Hawley-Smoot tariff of 1930.

Trade Policy and the New Deal

The central issue in the presidential election of 1932 was President Herbert Hoover’s handling of the Great Depression.1 Despite some government efforts, including limited public works spending, new federal relief programs, and loans from the Reconstruction Finance Corporation, Hoover’s policies failed to ameliorate the nation’s economic crisis. The monetary contraction continued through the first quarter of 1933, with production continuing to slide and unemployment continuing to increase.

Because of the lingering controversy over the Hawley-Smoot tariff and its contribution to the world’s economic disaster, the election campaign paid some attention to the trade policy differences between the two parties. Hoover and the Republicans defended the recent tariff increase and, in light of the country’s bleak economic situation, strongly opposed any reduction in import duties. They even suggested that further tariff hikes might be necessary to offset the depreciation of foreign currencies against the dollar, particularly after Britain and sterling bloc countries left the gold standard in September 1931. The Republican platform affirmed that the party “has always been the staunch supporter of the American system of a protective tariff. It believes that the home market, built up under that policy, the greatest and richest market in the world, belongs first to American agriculture, industry and labor. No pretext can justify the surrender of that market to such competition as would destroy our farms, mines, and factories, and lower the standard of living which we have established for our workers.”2

Meanwhile, the Democrats were again divided into high-tariff and low-tariff factions based largely on geography. The northern faction, led by the 1928 presidential nominee, Al Smith, and party chair John Jakob Raskob, controlled the Democratic National Committee and tried to write a high-tariff plank into the party’s platform. Raskob’s apparent acceptance of the status quo and suggestion that the party should not reduce tariffs that could harm industrial producers dismayed the party’s southern base, which strongly objected to the Hawley-Smoot tariff.3 Led by its senior statesman, Cordell Hull of Tennessee, the party’s southern wing still championed Woodrow Wilson’s goal of reducing tariffs, particularly if it could undo the damage to US exports. This group insisted that the party take a stand because “there must be more than mere hair-splitting differences between the two political parties on tariff and commercial policy”4

The Democratic presidential candidate, Franklin Roosevelt, did not have a clearly articulated view on trade policy, but he rejected the Smith-Raskob attempt to fix the party’s platform in a way that would alienate the southern wing of the party. As a result, the Democratic platform stated, “We condemn the Hawley-Smoot Tariff Law, the prohibitive rates of which have resulted in retaliatory action by more than forty countries, created international economic hostility, destroyed international trade, driven our factories into foreign countries, robbed the American farmer of his foreign markets, and increased the cost of production.” But the compromise plank also fell short of calling for tariff reductions, proposing instead “a competitive tariff for revenue with a fact-finding tariff commission free from executive interference, reciprocal tariff agreements with other nations, and an international economic conference designed to restore international trade and facilitate exchange.”5

In formulating his position, Roosevelt received a wide range of advice. Raymond Moley, one of Roosevelt’s close advisers and a member of his so-called brain trust, was responsible for drafting the main campaign speech on the tariff. “No speech in the campaign was such a headache as this,” Moley (1939, 50, 47) recalled, because tariff policy was “an apple of discord that had disrupted the Democratic party for a generation.” The speech-writing process was one of “clash and compromise” within the Roosevelt camp as the candidate and his advisors attempted to satisfy various constituencies within the party.

Roosevelt first received a proposed draft from Charles Taussig, the president of the American Molasses Co., a nephew of Frank Taussig, and an intermediary between Cordell Hull and the Roosevelt campaign. The Hull-Taussig draft blamed the economic slump on high tariffs and advocated a 10 percent reduction in duties. Other advisers thought that such a move would be politically impossible in the midst of the depression. Hugh Johnson, who had championed the concept of a parity price for agriculture in the 1920s, argued that there was no assurance that a unilateral tariff reduction would have a favorable impact on trade or improve the economy because trade restrictions had spread around the world. Instead, Johnson prepared an alternative draft that advocated bilateral tariff negotiations with foreign countries to gradually reopen the channels of world commerce. “What is here proposed is that we sit down with each great commercial nation separately and independently and negotiate with it alone,” Johnson wrote, “for the purpose of reopening markets of these countries to our agricultural and industrial surpluses.”6

At this point, Edward Costigan, a Democratic senator from Colorado and former member of the Tariff Commission, suggested that the Hull-Taussig and Johnson drafts be combined with enough equivocation to leave room for maximal flexibility.7 Taking this advice, Roosevelt instructed Moley in September 1932 to “weave the two together.” Moley was left speechless, because the two drafts seemed completely incompatible: one called for unilateral tariff cuts, while the other called for negotiations with trading partners. His difficulties were soon compounded when word reached the campaign that “the reaction to a horizontal tariff proposal in the West and Middle West would be immediate and devastating.” As Moley (1939, 49) learned, “there was a strong sentiment there for tariff increases on certain commodities!” Roosevelt then sought the advice of pro-tariff Congressmen from western states. Rep. Thomas Walsh (D-MT) took over the process, discarded the draft based on Hull’s ideas, and began editing Johnson’s draft that proposed tariff bargaining. According to Moley (1939, 50–51):

We showed Roosevelt the finished product. He rearranged it somewhat, made a few additions, and, when he had sent away the stenographer, smiled at me gayly, ‘There! You see? It wasn’t as hard as you thought it was going to be.’ I allowed that I wouldn’t have thought it would be hard at all had I known he was going to ignore the Hulls of the party, substantially, and merely throw them a couple of sops in the form of statements that some of the ‘outrageously excessive’ rates of the Hawley-Smoot tariff would have to come down. ‘But you don’t understand,’ he said. ‘This speech is a compromise between the free traders and the protectionists.’ And he meant it too!

Moley concluded that Roosevelt had effectively endorsed the Smith-Raskob view in favor of the status quo while giving up the traditional Democratic stance in favor of a “tariff for revenue only,” opting instead for a “tariff for negotiation.” As Moley (1939, 52) concluded, “So began seven years of evasion and cross-purposes on the tariff. But for the student of statesmanship the process was instructive.” Rexford Tugwell (1968, 478), another member of the brain trust, took more benign view of Roosevelt’s equivocation, thinking that it was “doubtless regarded by Roosevelt as no more than a necessary means of avoiding an issue on which he preferred not to take a stand during the campaign—something which, as I have noted, seemed to be the rule about other issues as well.”

Roosevelt gave his tariff speech in Sioux City, Iowa, in September 1932. He condemned the Hawley-Smoot tariff of 1930 for destroying America’s foreign trade, insisting that its “outrageously excessive rates” of duty “must come down.” Roosevelt argued that import duties were a meaningless form of farm relief, given the export position of most American farmers, and one that led to foreign retaliation that diminished the foreign market for the country’s farm surplus. He proposed holding an international conference to reduce tariffs around the world through “Yankee horse trading.” As Roosevelt (1933, 702) put it, “The Democratic tariff policy consists, in large measure, of negotiating agreements with individual countries permitting them to sell goods to us in return for which they will let us sell to them goods and crops which we produce.”8 In the process, he promised not to bring harm to any American industry.

Meanwhile, President Hoover continued to defend high tariffs and suggest that the United States had imported the depression from Europe. If the Hawley-Smoot duties were reduced, he warned, “the grass will grow in the streets of a hundred cities, a thousand towns; the weeds will overrun the fields of a million farms. . . . Their churches, their hospitals and schoolhouses will decay.”9 The president challenged Roosevelt to name which of the “outrageously excessive” rates he would cut. To reassure Western and Midwestern voters, Roosevelt responded by saying that there were no excessively high duties on farm products. He was then challenged by those in the East to specify the excessive duties on industrial products. At this point, Roosevelt fully retreated, stating: “I favor—and do not let the false statements of my opponents deceive you—continued protection for American agriculture as well as American industry.”10

Of course, the Great Depression crushed any hope that the Republicans could retain the presidency. Roosevelt won in a landslide, and the Democrats captured both houses of Congress with large majorities.11 Because of their seniority within the party, many southern Democrats rose to positions of leadership on important committees. Robert Doughton of North Carolina had taken over the House Ways and Means Committee in 1931, and Pat Harrison of Mississippi became chairman of the Senate Finance Committee in 1933. This ensured that the key committees were led by Southern Democrats who were very sympathetic to the reduction of import duties. In addition, Roosevelt appointed Cordell Hull as his secretary of state, ensuring that at least one senior administration official would also favor that policy.

The new president immediately made it clear that measures to promote domestic economic recovery would take priority over foreign trade policy. In his inaugural address in March 1933, Roosevelt stated that “our international trade relations, though vastly important, are in point of time and necessity secondary to the establishment of a sound national economy. I favor as a practical policy the putting of first things first. I shall spare no effort to restore world trade by international economic readjustment, but the emergency at home cannot wait on that accomplishment.”12

In fact, when Roosevelt took office, the country was in the midst of a major banking crisis. The president immediately declared a bank holiday to restore confidence in the nation’s financial system. In April, Roosevelt prohibited the export of gold and suspended the convertibility of the dollar into gold, which effectively took the country off the gold standard. Both actions helped improve monetary and financial conditions. The bank holiday succeeded in restoring confidence in the financial system, and monetary reflation was made possible now that gold reserves were officially no longer a factor in setting monetary policy.

The abandonment of the gold standard had an immediate, positive effect on the economy and started the recovery process. The policy change allowed the Federal Reserve to set monetary policy in line with domestic economic conditions, not simply to defend the dollar’s gold parity. The shift to a more expansionary monetary policy, which allowed the money supply to grow instead of shrink, ended four years of continuous deflation and started the economic recovery. For example, industrial production soared in the four months after March 1933, fell back, and then started rising again, ending the year 28 percent higher than when Roosevelt took office—with virtually no consumer price inflation. More than any other element of the New Deal, the abandonment of the gold standard and the freeing of monetary policy was critical to the subsequent economic expansion.13

Freed from the gold parity, the dollar began to depreciate on foreign exchange markets; by July it had declined 13 percent against the Canadian dollar and roughly 30–45 percent against other major currencies. The impact on trade was quickly felt: the volume of exports rose 40 percent between the first and fourth quarters of 1933, while the volume of imports increased 23 percent over the same period with the economic revival.14

Roosevelt had also promised to negotiate with other countries to reduce trade barriers and help expand foreign commerce. In April 1933, Roosevelt announced his intention to request authority from Congress to begin discussion with other countries to reach agreements that would reduce tariffs. However, as we shall see shortly, he soon postponed this request to ensure that Congress would pass the National Industrial Recovery Act and the Agricultural Adjustment Act. Roosevelt’s political advisors feared that adding trade legislation to the agenda for the first one hundred days might overload Congress and jeopardize the timely passage of the other domestic components of the New Deal.

The delay, along with Roosevelt’s equivocations during the campaign, raised questions about the administration’s commitment to a more liberal approach to trade policy. Indeed, it was not clear what sort of trade policies would emerge from the new administration. As State Department economic adviser Herbert Feis (1966, 262) recalled, there was “chaos and conflict within the government about the nature and direction of our commercial policy during the first year of Roosevelt’s presidency.” One State Department official wrote in late 1933 that “every department, especially the Tariff Commission, was in a fog as to the foreign trade policy to be pursued.”15

The problem was that economic policymakers within the Roosevelt administration were split between New Deal nationalists and Wilsonian internationalists. On one side, the brain trust, led by Columbia University professors Raymond Moley and Rexford Tugwell, were economic nationalists who believed that domestic controls and planning were necessary to restore economic growth and achieve full employment. The New Dealers had little regard for open trade policies and, furthermore, believed that domestic policies to promote economic recovery and foreign trade agreements to liberalize imports were fundamentally incompatible. The New Deal policies they championed sought to raise domestic prices for agricultural and industrial goods by reducing domestic supply; it was thought that this would restore business profitability and thereby reduce unemployment. For example, the National Recovery Administration (NRA) promoted codes of “fair competition” that permitted cartels and business associations in the hope that they would reduce output and increase prices and profits. Of course, the premise behind this approach was erroneous: the previous decline in prices had not been due to overproduction but to the decline in the money supply.16

Yet there was a tension between reducing domestic supply (in an effort to raise prices) and lowering trade barriers. If the supply-reduction policies succeeded and domestic prices rose, consumers might simply shift their purchases to imports and thereby reduce demand for domestic goods. To prevent this from happening, many New Deal policies allowed the president to impose import restrictions to ensure that higher domestic prices would not be undermined by imports. For example, section 3(e) of the National Industrial Recovery Act gave broad powers to the president to use import quotas or fees to regulate any imports that would “render ineffective or seriously endanger the maintenance of any code or agreement.” (The Supreme Court declared the NIRA unconstitutional in 1935.)

The same conflict applied with even greater force in agriculture. New Deal policy was again based on the idea that overproduction of agricultural goods had produced a glut of commodities that depressed prices. The Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA) encouraged production cutbacks and acreage restrictions to reduce supply and thereby increase the price of farm goods; farmers who reduced their acreage under production would be compensated with the revenue from a tax on processors. A 1935 amendment to the AAA gave the president the authority to impose import quotas that would reduce imports by as much as 50 percent from their 1928–33 level if imports were rendering ineffective or materially interfering with its programs.

The primary purpose of these provisions was not to protect domestic producers by reducing the share of imports in the domestic market. Rather, the goal was to prevent additional imports from undercutting government price supports designed to help manufacturers and farmers. At the same time, there was nothing in the statute that would prevent the president from using the authority in a protectionist manner. While some in the administration wanted to employ the authority for that purpose, import quotas were rarely imposed during the 1930s, covering only about 8 percent of imports in 1936, almost entirely sugar.17 However, the introduction and use of import quotas marked a departure from the traditional US opposition to them.18

In contrast to the illiberal approach to trade of the New Dealers, the new secretary of state, Cordell Hull, represented traditional low-tariff southern Democrats. During the administration’s first year, when there was tremendous uncertainty about its trade policy, Hull was a determined advocate of reducing trade barriers through negotiations. Ultimately he was successful, making Hull a pivotal figure in the history of US trade policy. Indeed, of all the people who have left a mark on US policy, none has had a greater or more lasting impact than Cordell Hull. Hull’s lifelong project, the reciprocal trade agreements program, fundamentally changed the direction of US trade policy over the course of the 1930s and 1940s. His success demonstrates that individuals, not just impersonal economic and political forces acting through Congress, can shape policy at critical moments.

Trained as a lawyer, Hull represented Tennessee in Congress when Roosevelt asked him to become secretary of state. Personifying the long-standing southern opposition to high tariffs, Hull believed that excessive import duties discouraged exports, harmed consumers and workers by increasing the cost of living, promoted the growth of monopolies and trusts, and redistributed income from poor farmers in the South and Midwest to rich industrialists in the North.19

World War I opened Hull’s eyes to the international implications of trade policies. The war marked “a milestone in my political thinking,” he recalled in his memoirs. “When the war came in 1914, I was very soon impressed with two points,” Hull (1948, 81) wrote. “I saw that you could not separate the idea of commerce from the idea of war and peace” and that “wars were often largely caused by economic rivalry conducted unfairly.” In Hull’s view, the quest of the European powers to gain access to foreign markets, particularly the competitive rivalry to establish colonial empires and secure preferential access to the world’s raw materials, was a factor behind the international tensions that eventually led to military conflict. Hull “came to believe that if we could eliminate this bitter economic rivalry, if we could increase commercial exchanges among nations over lowered trade and tariff barriers and remove unnatural obstructions to trade, we would go a long way toward eliminating war itself.”20 Having fought for lower tariffs solely for domestic reasons in the past, Hull (1948, 84) found that “for the first time openly I enlarged my views on trade and tariffs from the national to the international theater.”

Therefore, Hull (1948, 81) recalled,

Toward 1916 I embraced the philosophy that I carried throughout my twelve years as Secretary of State. . . . From then on, to me, unhampered trade dovetailed with peace; high tariffs, trade barriers, and unfair economic competition, with war. Though realizing that many other factors were involved, I reasoned that, if we could get a freer flow of trade—freer in the sense of fewer discriminations and obstructions—so that one country would not be deadly jealous of another and the living standards of all countries might rise, thereby eliminating the economic dissatisfaction that breeds war, we might have a reasonable chance for lasting peace.

Consequently, Hull (1948, 84) decided to devote all his political energy to reducing trade barriers: “After long and careful deliberation, I decided to announce and work for a broad policy of removing or lowering all excessive barriers to international trade, exchange and finance of whatsoever kind, and to adopt commercial policies that would make possible the development of vastly increased trade among nations. This part of my proposal was based on a conviction that such liberal commercial policies and the development of the volume of commerce would constitute an essential foundation of any peace structure that civilized nations might erect following the war.”

Hull watched with frustration the failure of international economic conferences during the 1920s, became an outspoken critic of the Hawley-Smoot tariff, and was horrified by the rise of protectionism and fascism around the world as a result of the Great Depression. The spread of illiberal trade policies and the rise of international tensions in the early 1930s seemed only to confirm the lessons he had learned from World War I. Although the prospects for change were dim, Hull never gave up hope that international cooperation on trade policy might make the world a safer and more prosperous place. As Hull (1937, 14) later affirmed, “I have never faltered, and I will never falter, in my belief that the enduring peace and welfare of nations are indissolubly connected with friendliness, fairness, equality, and the maximum practicable degree of freedom in international economic relations.”

In his first address as secretary of state, Hull declared that “most modern military conflicts and other serious international controversies are rooted in economic conditions, and that economic rivalries are in most modern instances the prelude to the actual wars that have occurred.” Easing global political tensions required “fair, friendly, and normal trade relations.” The time had come for the United States to exercise its leadership and establish world trade policies on an open, non-discriminatory basis. “Many years of disastrous experience, resulting in colossal and incalculable losses and injuries, utterly discredit the narrow and blind policy of extreme economic isolation,” he continued. “In my judgment, the destiny of history points to the United States for leadership in the existing grave crisis.”21

Hull was highly respected across the political spectrum for his experience and integrity.22 But his insistence that economic rivalry was the cause and not the consequence of international friction was debatable, to say the least. Many of his contemporaries thought that he was naive and completely exaggerated the likelihood that freer trade would promote peace. Several of his Senate colleagues warned Roosevelt that, as much as they liked and admired Hull, he was unsuited to be secretary of state. While not directly critical of Hull himself, most members of Congress were skeptical that increased trade would solve the political problems of the world. The isolationist Senator Hiram Johnson (R-CA) described him as a man with “more delusions concerning the world than a dog has fleas.”23 Hull was so focused on trade relations in the 1930s that he seemed oblivious to the broader conflicts that were moving the world toward another war. Although he inspired loyalty among those in the State Department, many in the Roosevelt administration viewed Hull as an idealist who chose to believe certain things rather than understand the world as it was. Roosevelt excluded him from most high-level foreign policy decisions.

Yet Hull persevered within the administration and outlasted his critics. The reciprocal trade agreements program was his pet project, and it eventually changed the direction of US trade policy. As Butler (1998, ix) writes, “Cordell Hull’s determination, persistence, and legislative experience were determining factors at every stage of the conception, passage, and implementation of the Trade Agreements Act.” Dean Acheson (1969, 9–10), who was at the State Department at this time and later served as secretary of state, recalled,

The Secretary—slow, circuitous, cautious—concentrated on a central political purpose, the freeing of international trade from tariff and other restrictions as the prerequisite to peace and economic development. With almost fanatical single-mindedness, he devoted himself to getting legislative authority, and then acting upon it, to negotiate ‘mutually beneficial reciprocal trade agreements to reduce tariffs’ on the basis of equal application to all nations, a thoroughly Jeffersonian policy. . . . Mr. Hull’s amazing success with this important undertaking, a reversal of a hundred years of American policy, was due both to his stubborn persistence and to his great authority in the House of Representative and the Senate.24

Toward a New Trade Policy

Had they came to power under ordinary circumstances, the Democrats might simply have reduced import duties through legislation, as they had done in 1894 and 1913. But the domestic and foreign economic situation in the early 1930s conspired to change the situation. First, a unilateral tariff reduction was politically impossible in the midst of the Depression with the unemployment rate so high. Though he had originally proposed a 10 percent reduction in tariffs during the election campaign, Hull (1948, 358) later admitted that “it would have been folly to go to Congress and ask that the Smoot-Hawley Act be repealed or its rates reduced by Congress.”

Furthermore, foreign trade barriers—in the form of higher tariffs, import quotas, and exchange controls—had increased sharply in the early 1930s. Even more problematic, American goods suffered from discrimination in foreign markets. The Ottawa agreements of 1932 created a system of imperial preferences aimed at keeping US goods out of major export markets, such as Canada and Britain. Germany also established preferential trade arrangements with southeastern Europe, while Japan set up the so-called “Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.” Standing outside of these trade blocs, the United States saw its share of world trade shrink. While Hawley-Smoot may have spawned some of these barriers, its unilateral repeal was not going to eliminate them. Many officials feared that abolishing the Hawley-Smoot duties would accomplish little unless opportunities were created for increasing exports as well.25

The World Economic Conference in London in June 1933 presented the new administration with its first opportunity to depart from Republican isolationism and cooperate with other countries in establishing better economic relations. Although the major topic of discussion was international monetary coordination and exchange-rate stability, Hull was determined to propose a multilateral effort to reduce tariffs. He departed for the London conference with the expectation that the administration would soon request trade-negotiating authority from Congress, as the White House had indicated it would, enabling him to make substantive proposals on trade.26 While sailing across the Atlantic, however, Hull was stunned to learn that Roosevelt had decided to postpone such a request. The president cabled Hull to say that trade-negotiating authority was “not only highly inadvisable, but impossible of achievement” at the moment, although the true reason was that trade policy was secondary to securing congressional passage of other New Deal legislation.27

Hull (1948, 251) was devastated—“the message was a terrific blow”—and he considered resigning, but Roosevelt assured him that he would support trade reforms in the near future. In any event, Hull found no support for a multilateral effort to reduce tariffs among the countries participating in the London conference. As Hull (1948, 356) recalled,

In earlier years I had been in favor of any action or agreement that would lower tariff barriers, whether the agreement was multilateral . . . regional . . . [or] bilateral. . . . But during and after the London Conference it was manifest that public support in no country, especially our own, would at that time support a worth-while multilateral undertaking. My associates and I therefore agreed that we should try to secure the enactment of the next best method of reducing trade barriers, that is, by bilateral trade agreements which embraced the most-favored-nation policy in its unconditional form—meaning a policy of nondiscrimination and equality of treatment.

Despite the failure of the meeting, Hull received high marks for his performance, which strengthened his hand within the administration. Hull also benefitted from his success at a Pan American conference in Uruguay in December 1933, in which delegates expressed their support for American-led efforts to open up trade. “The President, still pursuing the theory of retaining full discretionary authority to fix tariff rates at any height deemed necessary for the successful operation of the AAA and NRA, was slow to embrace my liberal trade proposal at Montevideo,” Hull (1948, 353) wrote. “But the success it achieved among the Latin American countries and in the press at home made him more friendly toward it.” Shortly after the December conference, Roosevelt announced his intention to request trade-negotiating authority from Congress.

In March 1934, after consulting with key congressional leaders, the president formally requested authority from Congress to undertake trade negotiations with other countries and, “within carefully guarded limits, to modify existing duties and import restrictions in such a way as will benefit American agriculture and industry.” In submitting the proposed legislation, Roosevelt stated that “it is part of an emergency program necessitated by the economic crisis through which we are passing.” As he explained, “a full and permanent domestic recovery depends in part upon a revived and strengthened international trade, and . . . American exports cannot be permanently increased without a corresponding increase in imports.” Noting that “other governments are to an ever-increasing extent winning their share of international trade by negotiating reciprocal trade agreements,” Roosevelt argued that “if American agricultural and industrial interests are to retain their deserved place in this trade, the American government must be in a position to bargain for that place with other governments by rapid and decisive negotiation. . . . If [the government] is not in a position at a given moment rapidly to alter the terms on which it is willing to deal with other countries, it cannot adequately protect its trade against discriminations and against bargains injurious to its interests.” However, in using the proposed authority, the president wished to “give assurance that no sound and important American interests will be injuriously disturbed. The adjustment of our foreign trade relations must rest on the premise of undertaking to benefit and not to injure such interests.”28

The administration’s draft legislation was just three pages long.29 Under the proposal, the Roosevelt administration would have the authority to reduce import duties by up to 50 percent in trade agreements with other countries. These tariff reductions could be implemented by executive order and would not need congressional approval. In addition, the tariff reductions would apply to imports from all countries through the unconditional most-favored-nation (MFN) clause, as adopted by the Harding administration in 1923. This was much more sweeping authority than Congress had ever granted any previous president. The Roosevelt administration justified the unprecedented request on the grounds that the foreign trade situation constituted an “emergency” and that decisive executive action to promote trade was desperately needed.

The administration’s bill was introduced by Robert Doughton (D-NC), the chairman of the Ways and Means Committee. The committee’s hearings were a sharp contrast to its consideration of the Hawley-Smoot tariff just five years earlier. In 1929, the committee heard from 1,131 witnesses (none from the executive branch) over forty-three days, generating 11,200 pages of published testimony (plus index) in 18 volumes. In 1934, the committee heard from just 17 witnesses (7 from the executive branch) over five days in testimony amounting to 479 published pages in one volume. While the 173-page Hawley-Smoot bill took eighteen months to work its way through Congress, the 3-page Reciprocal Trade Agreement Act took just four months to be enacted.30

Several key administration officials testified before the committee and argued that executive action was necessary to revitalize world trade for the benefit of the American economy. Hull argued that “the primary object of this new proposal is both to reopen the old and seek new outlets for our surplus production, through the gradual moderation of the excessive and more extreme impediments to the admission of American products into foreign markets.” He stressed that the negotiating authority was emergency legislation designed to stimulate foreign trade in response to “unprecedented economic conditions.”31

The Democratic majority on the Ways and Means Committee endorsed the administration’s request and favorably reported the bill. The Republican minority report objected that the legislation “contemplates the abandonment of the principle of protection for domestic industry, agriculture, and labor by allowing duties to be modified without reference to the difference in cost of production of domestic and foreign articles.” Republicans complained that the bill gave the president “the absolute power of life and death over every existing domestic industry dependent upon tariff protection, and permits the sacrifice of such industries in what will undoubtedly be a futile attempt to expand the export trade of other industries,” thus risking “serious possibilities of disastrous consequences.” They also charged that the bill was an unconstitutional delegation of Congress’s power to levy taxes and that any negotiated trade agreement had to be approved by Congress.32

To allay some Democratic concerns about the unprecedented grant of authority, Doughton introduced a key amendment on the House floor that would ensure ongoing congressional influence over trade policy.33 While the administration had proposed (with the concurrence of the Ways and Means Committee) that the negotiating authority have no time limit, the House agreed to limit it to just three years, after which it would terminate unless renewed by Congress. This proved to be an important means by which Congress could oversee the program, because the threat of not renewing the negotiating authority would keep the executive branch accountable to the legislature and sensitive to its concerns. Had the time limit not been added, a two-thirds majority of both houses of Congress would have been required to override a presidential veto of any bill stripping away the negotiating authority.34

House Democrats rallied behind the president’s proposal. The Roosevelt administration had enormous political authority in its first few years, and the Democratic Congress was willing to grant it extraordinary powers over the economy. Although giving the president the ability to reduce tariffs would have been unthinkable in ordinary times, the badly handled Hawley-Smoot revision in 1929–30 and the ensuing economic collapse helped persuade Democrats that such discretionary authority was necessary. As Charles Faddis (D-PA) put it, tariff policy

is not a matter which can be satisfactorily disposed of in Congress. . . . It is a matter for slow and careful consideration. It must be gone into cautiously, step by step, with the idea of a general plan. Congress cannot do this, for in this country the tariff is to each Member of Congress a local issue. The tariff has always been a logrolling issue. Such an issue can have no general plan, and without a general plan the issue can never be settled. We must have a national tariff policy. At the present time we can have it no other way except by giving the authority to formulate it to the President.35

Republicans strenuously objected to giving the president the ability to reduce tariffs, arguing that the delegation of such authority was unconstitutional and would erode the protection given to key industries. These criticisms would be repeated for more than a decade. But like the claim during the 1820s that protective tariffs were unconstitutional, the claim that the RTAA was unconstitutional had no force. One problem with the argument was that Republicans themselves had delegated “flexible tariff” authority to the president in 1922 and 1930, which the Supreme Court had ruled as constitutional. Of course, objecting to the constitutionality of the RTAA was just a political maneuver to prevent tariffs from being reduced. When asked why he had supported President Hoover’s bid for a flexible tariff provision but now opposed Roosevelt’s similar request, Harold Knutson (R-MN) replied: “Frankly, I know the purpose of this legislation is to lower rates. If I thought for a minute that it was proposed to raise rates to meet the present conditions, I would vote for this legislation and be glad of the opportunity to do so.”36

Given the large Democratic majority, the House passage of the bill was a foregone conclusion. On March 29, 1934, the House passed the RTAA by a vote of 274–111, with Democrats voting 269–11 in favor, Republicans voting 99–2 against, and Farmer-Laborer voting 3–1 in favor. Western Democrats had the most difficulty supporting the bill because that region was hit hardest by the Depression, and many wanted price supports and tariff protection for their crops and commodities.

But could Democrats hold together and get the bill through the Senate? As seen in the past, party control was much weaker in the Senate, and the West had greater representation. Almost all tariff legislation had encountered difficulties in the Senate, and the minority Republicans still had hopes that they could derail the administration’s plans. They attacked the legislation, arguing that reducing tariffs in the midst of a depression was economic suicide. Arthur Vandenberg (R-MI) called the bill a “dangerous measure” that gave “autocratic Presidential power in connection with the tariff.” Republicans went so far as to say that the RTAA would create a “fascist dictatorship in respect to tariffs” and warned that there were “no shackles upon the use of this extraordinary, tyrannical, dictatorial power over the life and death of the American economy.”37 Even progressive Republicans who opposed the Hawley-Smoot tariff fell in line with their party and objected to the bill. William Borah (R-ID) worried that the trade authority would be used to exchange lower US duties on imported raw materials for lower foreign duties on US manufactured goods, thereby helping the East at the expense of the West.

The Senate Finance Committee amended the House bill to include a requirement that the administration give public notice of its intent to negotiate an agreement and allow interested parties to have a voice in the process. Otherwise, the committee moved quickly, reporting the bill less than a month after the House passage. On the Senate floor, the Democratic leadership defeated a series of proposed amendments, mainly from Republicans, ranging from an exemption of wool and other agricultural commodities from any tariff reduction to a requirement that Congress approve any trade agreement and a ban on any agreement with countries whose wages were less than 80 percent of those in the United States. Democrats held together and fought these proposed changes to the legislation. “If we are going to destroy the ability of the President to act promptly we might as well quit wasting our time in debating the bill at all,” Alben Barkley (D-KY) argued.38

On June 4, 1934, the Senate approved the RTAA by a vote of 57–33, with Democrats voting 51–5 in favor and Republicans voting 28–5 against. The House concurred with the Senate changes and sent the bill to the president for his signature. Hull (1948, 357) later recalled the moment: “At 9:15 on the night of June 12 I watched the President sign our bill in the White House. Each stroke of the pen seemed to write a message of gladness on my heart. My fight of many long years for the reciprocal trade policy and the lowering of trade barriers was won. To say I was delighted is a bald understatement.”

Hull (1948, 357) later contended that “in both House and Senate we were aided by the severe reaction of public opinion against the Smoot-Hawley Act.” In fact, the passage of the RTAA simply reflected the massive change in the partisan composition of Congress, with Democrats replacing Republicans. After examining the votes of all members of Congress who voted on both Hawley-Smoot and the RTAA, Schnietz (2000) clearly shows that Congress did not “change its mind” about the wisdom of the Hawley-Smoot tariff. That would imply that members who voted for Hawley-Smoot later regretted its consequences and voted for the RTAA. Of the ninety-five members of Congress who voted in favor of Hawley-Smoot, only nine voted in favor of the RTAA. Of those nine, seven were Democrats; only two of eighty-six Republicans changed their view.

One of the two Republicans, Arthur Capper of Kansas, may have changed his mind due to the events that followed the passage of Hawley-Smoot. “I am a firm believer in the protective tariff,” Caper stated. “But it has seemed to me ever since we enacted the latest tariff act . . . that the United States has a Gordian knot to undo in the matter of interference with world trade by tariffs, quotas, embargos, and similar trade restrictions.” In Capper’s view, if the United States wanted to restore world trade, it had few options other than to seek reciprocal trade agreements.

But if reciprocal trade agreements are to be negotiated, it does not look as if Congress, from the practical viewpoint, is qualified, or even able, to undertake the task. . . . . our experience in writing tariff legislation, particularly in the postwar era, has been discouraging. Trading between groups and sections is inevitable. Log-rolling is inevitable, and in its most pernicious form. We do not write a national tariff law. We jam together, through various unholy alliances and combinations, a potpourri or hodgepodge of section and local tariff rates, which often add to our troubles and increase world misery. For myself, I see no reason to believe that another attempt would result in a more happy ending.39

One remarkable aspect of the RTAA was the utter lack of interest by the industry groups that usually tried to influence Congress’s setting of tariff rates. The Ways and Means Committee received only sixty-three pieces of RTAA-related correspondence, fifty-nine of which opposed the bill. Unlike the Hawley-Smoot tariff, the RTAA attracted very little support or opposition by interest groups, even export associations who stood to benefit from it.40 One reason for the almost complete lack of interest, according to Haggard (1988, 112), is that in contrast to 1930 “when interest groups were the main protagonists and specific tariff rates the issue, the most important issues at stake in 1934 were institutional, centering on the transfer of authority from Congress to the executive.” The RTAA was simply enabling legislation, and no one knew how the authority would be used, how successful the negotiations would be, how extensive any agreements might be, or which interests might be most affected. When the RTAA was passed, Congress and trade-affected economic interests could not anticipate how important the legislation would become, or even whether it would be sustained by future Congresses.

Thus, the RTAA did not arise because of the demands of interest groups, but because Cordell Hull and other southern Democrats had long championed a significant reduction in tariffs and the promotion of exports. The Great Depression prevented a unilateral tariff reduction and presented policymakers with the need to address the many foreign trade barriers that had arisen against US exports. The policy change was not driven by interest groups; instead, administration officials took the lead in changing policy, and interest groups later followed. Similarly, it is interesting to recall that the Hawley-Smoot tariff was also largely initiated by politicians as a way of appeasing agricultural interests; it was not something that industry demanded or that farmers believed would help them in any significant way. This suggests that politicians can sometime use economic interests to achieve their political goals and that a country’s tariff policy is not just the result of economic interests manipulating politicians for their own self-interested ends.

The Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act of 1934

According to its preamble, the RTAA was enacted “for the purpose of expanding foreign markets for the products of the United States . . . as a means of assisting in the present emergency in restoring the American standard of living.” The president could proclaim lower duties on foreign goods entering the United States “in accordance with the characteristics and needs of various branches of American production.”41 The RTAA, which was technically an amendment to the Tariff Act of 1930, allowed the president to enter into trade agreements with foreign countries provided “reasonable” public notice of the intention to negotiate an agreement was given to allow interested parties to present their views. This authority would expire in three years. As a result of such agreements, the president could issue an executive order increasing or decreasing import duties on particular goods by no more than 50 percent, but could not transfer any article between the dutiable and duty-free lists. The duties would apply to imports from all countries on an unconditional MFN basis.

Because of its importance for US trade policy, the RTAA has long attracted the interest of scholars studying regime change.42 Some studies have interpreted the RTAA as a cleverly designed institutional mechanism to lock in the Democrats’ preferred tariff level. With hindsight, this interpretation seems true, but the RTAA’s success was not guaranteed from the outset. There was absolutely no assurance that other countries would be willing to negotiate with the United States or that any such agreements would reduce tariffs in any significant degree. The Democratic Congress and the Roosevelt administration could not commit future policymakers to continue the reciprocal trade agreements approach. The RTAA could easily have been reversed by the Republicans when they returned to power, and until the early 1940s they explicitly vowed to abolish the RTAA and even reverse any tariff changes that it brought about. While the reputational costs to American foreign policy of reversing the tariff reduction by withdrawing from a trade agreement were higher than a reversal of a unilateral tariff reduction, those costs were not prohibitive. A bipartisan consensus in favor of the RTAA did not emerge until after World War II (as discussed in chapter 10).

Rather than a far-sighted Democratic ploy to introduce irreversible tariff changes, the RTAA was a pragmatic response to the circumstances of the day: The Great Depression prevented any serious consideration of a unilateral tariff reduction, and the proliferation of new foreign trade barriers that so impeded US exports demanded a response. Of course, the RTAA also tipped the political balance of power in favor of lower tariffs. First, Congress essentially gave up the ability to legislate duties on specific goods when it delegated tariff-negotiating power to the executive. If the president was successful in concluding trade agreements, Congress would no longer have to set import duties and go through the process of vote-trading to help different import-competing interests. Once tariffs were bound in a trade agreement, it would be more difficult for Congress to start changing them in legislation. Furthermore, Congressional votes on trade policy were now framed simply in terms of whether to continue the RTAA program or not, and if so under what conditions.

The RTAA also reduced the threshold of political support needed for members of Congress to approve tariff reductions by means of executive agreements as opposed to treaties. The renewal of the RTAA required a simple majority in Congress, whereas any treaty negotiated by the president prior to the RTAA had to be approved by two-thirds of the Senate. This reduced the number of legislators needed to pass agreements that reduced import duties and conversely increased the number of legislators needed to block such agreements under the RTAA.

In addition, the RTAA delegated powers over trade policy to the executive branch, which was more likely to favor moderate tariffs than the Congress. The president had a national electoral base and was more likely to favor policies that would benefit the nation as a whole than were members of Congress, who represented specific geographic regions. The president was also more likely than Congress to take into account a broader set of factors in setting trade policy, including exporter and consumer interests, as well as foreign policy and national security considerations.

Finally, the RTAA helped boost the bargaining position and lobbying strength of exporters in the political process. Previously, import-competing domestic producers were the main lobby group on Capitol Hill in relation to trade legislation, since they reaped the benefits of high tariffs. Such tariffs harmed exporters, but only indirectly: The cost to any exporter of any particular import duty was miniscule, and therefore exporters failed to organize an effective political opposition. By directly tying lower foreign tariffs to lower domestic tariffs, the RTAA fostered the development of exporters as an organized group opposed to high tariffs and supporting trade agreements. The lower tariffs negotiated under the RTAA also increased the size of the export sector and thereby strengthened political support for continuing the program.

Of course, the RTAA did not end lobbying by industries facing foreign competition. As Francis B. Sayre (1939, 96), an assistant secretary of state responsible for overseeing the trade agreements program, stated, “Every time it is proposed to lower a tariff, the lobbyists and the politicians descend upon Washington, and intense pressures are brought to bear upon those responsible for decisions.” Although this did not change, the RTAA diverted such political pressure away from a relatively sympathetic Congress toward the less sympathetic executive branch. The State Department was much less responsive to producer interests than members of Congress who faced reelection by these constituents. The State Department was also able to balance pressure from import-competing interests with export interests, as well as to consider the broader diplomatic and economic benefits of trade agreements. For this reason, Vandenberg complained that negotiated tariff reductions represented “the cloistered and wishful guesses of bureaucrats with free-trade inclinations”43

Of course, the RTAA did not make a shift toward freer trade inevitable, because sustaining the program required the ongoing support of the president and a majority in Congress. The RTAA passed easily in 1934 because the Democrats had large majorities in Congress. As long as those majorities were maintained, the RTAA was likely to be continued, but the program would have been in serious jeopardy had the Republicans regained control of Congress in the 1930s.

The Trade Agreements Program in Operation

Less than three months after the enactment of the RTAA, the State Department signed a trade agreement with Cuba and announced its intention to negotiate with eleven other countries. Yet the trade agreements program got off to a slow start because of intense conflict with the Roosevelt administration. As Hull (1948, 370) recalled, “The greatest threat to the trade agreements program [in its first year] came not from foreign countries, not from the Republicans, not from certain manufacturers or growers, but from within the Roosevelt administration itself, in the person of George N. Peek.” This bureaucratic infighting nearly destroyed the entire program.

Within the administration, George Peek was not alone in his belief that lower tariffs would conflict with New Deal programs that sought to raise domestic prices. In March 1934, Roosevelt appointed Peek to be his foreign trade adviser, operating outside the State Department. Hull (1948, 370) was dumbfounded: “If Mr. Roosevelt had hit me between the eyes with a sledgehammer he could not have stunned me more than by this appointment.” Despite his help in drafting the RTAA legislation, Peek branded agreements to reduce tariffs as “unilateral economic disarmament” and scorned the unconditional MFN clause as “un-American.” Taking high tariffs, exchange controls, and import quotas as a fixed part of the global trade environment, Peek favored government-brokered bilateral trade deals to dispose of America’s surplus agricultural production. Peek proposed to negotiate barter arrangements, deal by deal, making the government a commercial agent for the nation’s exports and imports. “Under an emergency short-time approach every effort should be made to effect trade ‘deals’ between this and other countries that are mutually advantageous,” Peek (1936, 178) wrote. “We should explore, for example, the possibilities of selling wheat to China, pork to Russia, and the like. Direct barter, to obviate exchange difficulties, in some cases may be possible.”

Hull abhorred the idea that the government should become the broker for American farmers and manufacturers, cutting deals and making trade bargains with other countries. If the United States adopted this approach, and other countries followed, it could find itself on the losing end of managed trade arrangements. Hull wanted to eliminate special trade deals entirely and make equality of treatment the cornerstone of trade relations. Government should get out of directing trade flows and ensure that private enterprise had an opportunity to compete in an open and non-discriminatory world market, free from government interference and trade preferences. Peek thought Hull was naive and impractical for trying to return the world economy to non-discriminatory, market-driven trade.

These fundamentally different visions for trade policy led to internecine battles in the Roosevelt administration. As Peek jockeyed with other agencies for influence over trade policy, Hull and the State Department were forced to spend much of 1934 and early 1935 fighting off his efforts to gain control of trade policy. When Peek was also appointed to head the Export-Import Bank, a new government agency designed to finance exports through concessional loans to foreign purchasers, he was positioned to broker specific trade deals.44 For example, in December 1934, Peek arranged for the Bank to sell eight hundred thousand bales of cotton to Germany for a certain amount of money, one-quarter of which would be paid in dollars and the remainder in German marks, with a premium. The marks would then be sold by the Export-Import Bank at a discount to American importers of German goods.

Hull and his assistant Francis Sayre argued strenuously against such preferential deal-making. In their view, Peek failed to recognize that economic nationalism through government-brokered transactions would not help American commerce flourish in the long-run. That strategy risked a further carving up of world trade on the basis of political deals and, to the extent that the United States was successful, made it vulnerable to the threat of foreign retaliation. Indeed, Brazil threatened to cut off trade negotiations with the United States and retaliate, because its cotton exports were going to be displaced as a result of Peek’s deal with Germany. After the State Department intervened, Roosevelt withdrew support for Peek’s plan; that this arrangement had been made with Nazi Germany did not help Peek’s cause. Thereafter, Peek’s influence began to wane. He became an increasingly strident internal critic of the administration, and Roosevelt accepted his resignation in November 1935. Out of office, Peek wrote a blistering attack on the RTAA in his 1936 book Why Quit Our Own?

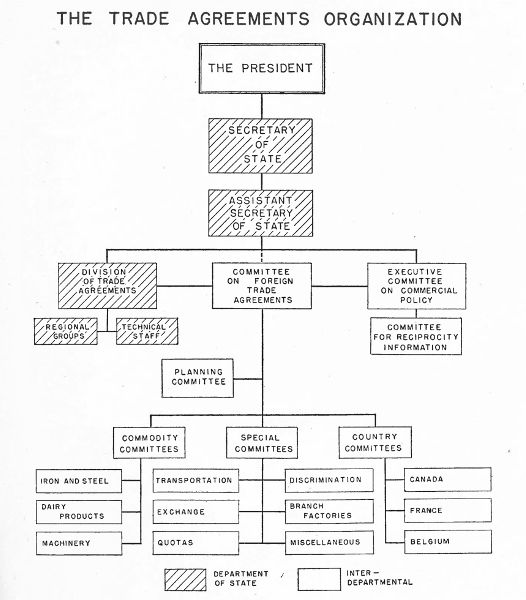

With Peek’s departure, the State Department consolidated its control over trade policy and began to move forward with trade negotiations. The organizational structure is shown in figure 9.1 The trade agreements program was overseen by the Executive Committee on Commercial Policy, administered by the interdepartmental Trade Agreements Committee, and assisted by the Committee on Reciprocity Information. Each of these committees included representatives from the Departments of Agriculture, Commerce, and Treasury, as well as the Tariff Commission, but the State Department coordinated and dominated the process.

The trade agreements process worked as follows. The assistant secretary of state would first explore whether certain countries were interested in negotiating a trade agreement with the United States. If the country was agreeable in principle to reducing tariffs, the interdepartmental committee would announce the government’s intent to negotiate with the country. Time was set aside for public comment, usually from exporters hoping that particular foreign tariffs would be reduced and from domestic producers opposed to tariff reductions on certain commodities imported from the prospective partner country. These comments were received by the Committee for Reciprocity Information. “Often the outcry at public hearings over the expected ruinous effects of proposed tariff cuts would be based on fear rather than fact,” Sayre (1957, 170) recalled. Yet, he continued, “the hearings were real, never superficial. We always were ready to modify our original ideas as a result of these hearings. We were bent on doing an honest and sound piece of work.”

Then the Trade Agreements Committee would begin the bilateral negotiations. The United States would not offer an across-the-board tariff reduction; instead, it would offer tariff cuts on a selective, product-by-product basis “in accordance with the characteristics and needs of the various branches of American production,” as required by the RTAA. The selective approach had two purposes. First, certain politically important, import-sensitive sectors could be exempted from the reduction and thus not have to face greater foreign competition. Second, tariffs would be reduced only on goods of which the partner country was a “principal supplier.” This would give other countries an incentive to negotiate with the United States, since their exporters would benefit the most, in addition to mitigating the problem of other countries free riding on the unconditional MFN nature of the tariff reductions. If an agreement was concluded, the changes in the tariff rates would take effect by executive order.

As the State Department built up negotiating experience, it developed a template for reciprocal trade agreements with a set of provisions that could be modified to reflect the particulars of each country. The first section of the agreement related to trade in general and included articles on the most-favored-nation clause, internal taxes, quotas and exchange controls, and monopolies and government purchases. The second section contained provisions relating to the tariff concessions, such as the changes in import duties by each country and the conditions governing the withdrawal or modification of those concessions. (Of course, the exact changes in duties were determined in the negotiations.) The final section dealt with matters such as territorial application, exceptions to MFN treatment, general reservations, consultations on technical matters (such as sanitary regulations of trade), and the provisional application, duration, and possible termination of the agreement.45

The trade agreements process meant that the State Department and other executive branch officials began to play a more important role in the formation of trade policy than the committee chairs in Congress who traditionally dominated the process. Although Secretary Hull was rarely involved in the details of the trade negotiations himself, his strong support for the program made it a central part of the State Department’s activities during the 1930s. Given his passionate interest in reducing trade barriers and his long tenure as Secretary of State, Hull gave the State Department a lasting purpose and direction that shaped its approach to trade policy long after his departure.46

At the start of the RTAA, Assistant Secretary of State Francis Sayre, a Harvard law professor and son-in-law of Woodrow Wilson, and Herbert Feis, a State Department official and an economist, were responsible for implementing and overseeing the program. Although Sayre and Feis had other responsibilities, both “would play very important roles in drafting the trade legislation, lobbying for its passage through Congress, ensuring that the State Department oversaw its implementation after passage, and negotiating individual agreements with the United States’ trading partners.”47 Another economist, Henry Grady, headed the Trade Agreements Committee from 1934 to 1936. He was succeeded by Harry Hawkins, also an economist, who ran the Department’s Trade Agreements Division from 1936 until 1944. By all accounts, Hawkins was the key individual responsible for the success of the program. He was highly respected and handled the negotiations and the interdepartmental process with great diplomatic skill. In his memoirs, Hull (1948, 366) singled out Hawkins for unusually high praise: “No one in the entire economic service of the Government, in my opinion, rendered more valuable service than he. Hawkins was a tower of strength to the department throughout the development of the trade agreements, and especially in our negotiation with other countries, which at times were exceedingly difficult.”48

The trade agreements program got off to a slow start not just because of the Hull-Peek dispute but because other countries were reluctant to reduce trade barriers when their economies were still far from full employment and weak from the Depression. As a result, the United States had mixed success in concluding trade agreements during the 1930s and even less success in negotiating sizeable reductions in import duties. By 1936, agreements had been reached with only three of the nine largest US export markets: Canada, France, and the Netherlands. Germany had requested negotiations, but the United States refused because of its discriminatory trade policies, particularly its privileged barter arrangements with southeastern Europe. Japan, Argentina, and Australia expressed no interest in negotiating with the United States, and talks with Italy broke down. Many of the agreements were with Latin American countries, whose raw material exports did not pose a threat to domestic industries.49

Hull keenly wanted a trade agreement with Britain, the second largest US export market. As we saw in chapter 8, Britain adopted a system of imperial preferences that gave special treatment to goods from the British Empire. The State Department was particularly keen to reduce the preference margins in the Ottawa agreements that discriminated against American goods in Britain and Canada, America’s two most important foreign markets.50 Testifying before Congress in 1940, Hull called imperial preferences “the greatest injury, in a commercial way, that has been inflicted on this country since I have been in public life.”51

After the midterm election of 1936, Hull pressed Britain to open trade negotiations, but British officials were reluctant. The United States took just 6 percent of British exports, and Britain did not want to jeopardize its preferential access to markets where it had a much larger commercial stake. As the risk of a European war increased, Britain began to recognize the diplomatic advantages of reaching an agreement with the United States. Britain eventually decided to pursue it to solidify Anglo-American cooperation. Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain agreed to move forward because “it would help to educate American opinion to act more and more with us, and because I felt sure it would frighten the totalitarians. Coming at this moment, it looks just like an answer to the Berlin-Rome-Tokyo axis.”52 Because the United States was formally a neutral power, however, the State Department had to downplay the foreign policy implications of the agreement “in deference to the widespread isolationist sentiment here,” Hull (1948, 529) recalled. “We could stress our belief that liberal commercial policy, epitomized by the trade agreements, tended to promote peace, but we had to be careful to emphasize that an agreement with Britain on trade comported no agreement whatever in the nature of a mutual political or defense policy.”

In January 1938, both countries formally announced their intention to start negotiations, which began the following month. The discussions were difficult on both sides: the United States was in the midst of the severe 1937–38 recession, which made officials reluctant to expose manufacturing industries to more competition from imports, while Britain was reluctant to reduce its imperial preferences and wanted more concessions from the United States, on the grounds that its tariffs were, on average, much higher than Britain’s. The result was “a limited and unspectacular treaty, produced by difficult and protracted negotiations.”53 The extent of the tariff reductions was exceedingly modest, and little progress was made in reducing the margins of preference that discriminated against American exports. At the same time, public opinion supported the effort. In a March 1938 poll, nearly three-quarters of respondents thought that the United States should reduce its tariffs on British goods if Britain did the same for American goods; only one-quarter opposed such a policy, and there was no significant partisan difference in the result.54

However, the agreement was in effect for less than a year before Britain entered World War II in September 1939. The agreement was rendered inoperative because Britain was forced to adopt severe trade controls as part of the war effort. Still, the agreement marked the beginning of closer political and economic ties between the two nations.

By the end of the 1930s, the RTAA could be considered a modest success. By 1940, the United States had signed agreements with twenty-one nations that accounted for nearly two-thirds of US trade. Table 9.1 lists the countries that signed trade agreements with the United States during this period. The State Department publicized the fact that exports to agreement countries rose 63 percent between 1934–35 and 1938–39, while exports to non–agreement countries rose only 32 percent. Meanwhile, imports from agreement countries rose 22 percent, while imports from non–agreement countries rose 13 percent over the same period.55 Furthermore, the United States seemed to be making progress in regaining its previous share of world trade. The United States accounted for 61 percent of Canada’s imports in 1932, when imperial preferences were introduced. That share fell to 57 percent in 1936, but rose to 63 percent by 1939.56 How much of this recovery can be attributed to the RTAA is open to question, but the general trend seemed to support the view that the trade agreements made a positive contribution in expanding the US share in some foreign markets.

Table 9.1. Trade agreements, 1934–1944

| Country | Signed | Effective |

|---|---|---|

|

Cuba |

Aug. 24, 1934 |

Sept. 3, 1934 |

|

Brazil |

Feb. 2, 1935 |

Jan. 1, 1936 |

|

Belgium (and Luxembourg) |

Feb. 27, 1935 |

May 1, 1935 |

|

Haiti |

March 28, 1935 |

June 3, 1935 |

|

Sweden |

May 25, 1935 |

Aug. 5, 1935 |

|

Colombia |

Sept. 13, 1935 |

May 20, 1936 |

|

Canada |

Nov. 15, 1935 |

Jan. 1, 1936 |

|

Honduras |

Dec. 18, 1935 |

Mar. 2, 1936 |

|

The Netherlands |

Dec. 20, 1935 |

Feb. 1, 1936 |

|

Switzerland |

Jan. 9, 1936 |

Feb. 15, 1936 |

|

Nicaragua |

Mar. 11, 1936 |

Oct. 1, 1936 |

|

Guatemala |

Apr. 24, 1936 |

June 15, 1936 |

|

France |

May 6, 1936 |

June 15, 1936 |

|

Finland |

May 18, 1936 |

Nov. 2, 1936 |

|

Costa Rica |

Nov 28, 1936 |

Aug. 2, 1937 |

|

El Salvador |

Feb. 19, 1937 |

May 31, 1937 |

|

Czechoslovakia |

Mar. 7, 1938 |

April 16, 1938 |

|

Ecuador |

Aug. 6, 1938 |

Oct. 23, 1938 |

|

United Kingdom |

Nov. 17, 1938 |

Jan. 1, 1939 |

|

Canada (second agreement) |

Nov. 17, 1938 |

Jan. 1, 1939 |

|

Turkey |

Apr. 1, 1939 |

May 5, 1939 |

|

Venezuela |

Nov. 6, 1939 |

Dec. 16, 1939 |

|

Cuba (first supplementary agreement) |

Dec. 18, 1939 |

Dec. 23, 1939 |

|

Canada (supplementary fox-fur agreement) |

Dec. 13, 1940 |

Dec. 20, 1940 |

|

Argentina |

Oct. 14, 1941 |

Nov. 15, 1941 |

|

Cuba (second supplementary agreement) |

Dec. 23, 1941 |

Jan. 5, 1942 |

|

Peru |

May 7, 1942 |

July 29, 1942 |

|

Uruguay |

July 21, 1942 |

Jan. 1, 1943 |

|

Mexico |

Dec. 23, 1942 |

Jan. 30, 1943 |

|

Iran |

Apr. 8, 1943 |

Jun. 28, 1944 |

|

Iceland |

Aug. 27, 1943 |

Nov. 19, 1943 |

Source: US Tariff Commission 1948.

The trade agreements had a relatively modest effect in reducing US import duties. Figure 9.2 shows a scatterplot of the average tariff rate by schedule in 1880 and in 1939. This figure reveals that the basic structure of import duties was little changed from the late nineteenth century, another indication of the lasting stability of policy over this period. In addition, tariff rates had come down only slightly. The Tariff Commission found that the first thirteen agreements implemented by 1936 reduced the average tariff on dutiable imports from 46.7 percent to 40.7 percent, a six-percentage-point drop. This would bring the average tariff back to where it had been prior to the enactment of the Hawley-Smoot duties.57 Thus it could be said that the tariff reductions negotiated under the RTAA effectively reversed the Hawley-Smoot increase with the added advantage of having foreign countries reduce their tariffs on US exports as well.

Figure 9.2. Average tariff rate by schedule, 1880 and 1939. (Statistical Abstract of the United States 1885, 13–4; 1942, 572–74).

More broadly, the average tariff on dutiable imports fell from 46.7 percent in 1934 to 37.3 percent in 1939, putting it just below the pre-Hawley-Smoot level of 40.1 percent in 1929. Some of this decline was the result of an 11 percent increase in import prices between 1934 and 1939, which reduced the ad valorem equivalent of the specific duties that had been nominally set in 1930. These higher import prices knocked about 3.3 percentage points off the average tariff. Therefore, of the actual decline in the tariff of 9.4 percentage points, 6.1 percentage points were due to trade agreements, and 3.3 percentage points were due to import price inflation.58

What was the impact of this tariff reduction on America’s foreign trade? The impact on exports is very difficult to determine because information is not available on the extent to which other countries reduced their tariffs. Regarding imports, if the lower tariffs were fully passed through to import prices, the tariff reduction attributable to the RTAA would have reduced the average price of dutiable imports by about 4 percent. This would have a limited impact on total imports, the growth of which was driven more by the economic recovery. The volume of imports only rose 23 percent between 1933 and 1939, a number kept down because of the severe 1937–38 recession, while export volume rose 60 percent over that period.59 While there are no conclusive studies on the matter, the RTAA may have made a small contribution to the economic recovery after 1933 by promoting export growth.

The impact on imports, although distorted by the recession, was modest by design. Hull instructed his department to undertake the tariff reductions with vigor but “gradually and with due care at every stage.”60 Hull was very cautious and did not want to offend powerful domestic interests that might trigger congressional opposition to the program. Hull and his deputies went to great lengths to avoid harming domestic producers by reducing tariffs more on imports that did not compete with domestic production. He consistently maintained that the program was designed to reduce excessive tariffs, not introduce free trade. As Sayre (1957, 170) recalled, “Our whole program was based upon finding places in the tariff wall where reductions could be made without substantial injury to American producers.” (One could read “without substantial injury” as meaning “without arousing political opposition.”) “The trade agreements program is not in any sense a free trade program,” Grady (1936, 295) held. “It is merely an attempt . . . to restore . . . to American enterprise its natural markets abroad and at the same time [provide] reasonable protection for domestic industry.”

The extent of the tariff reductions varied considerably across commodities because the State Department negotiators had discretion in choosing where to make the cuts, avoiding politically sensitive industries wherever possible. Hull insisted that the president be briefed on the concessions in every prospective trade agreement to ensure that the State Department had political cover for any trade agreement that it reached. Roosevelt usually approved the agreements put before him and was much more willing than Hull to take political risks. As Francis Sayre (1957, 170) recalled, “Occasionally, however, a proposed cut might do local hurt, and I would say to the President: ‘Here we must make a tariff cut which might harm you politically. You may hear about this.’ Almost always he would reply, ‘Well, Frank, if it’s necessary, go ahead, go ahead.’ He had confidence in us and did not hesitate to follow through with our program.”61

The Roosevelt administration highlighted its cautious approach when it appealed to Congress to renew the program in 1937. In a letter to the Ways and Means Committee, the president stated, “In the process of obtaining improvement in our export position the interests of our producers in the domestic market have been scrupulously safeguarded.”62 Testifying before Congress in 1940, Hull argued,

No evidence of serious injury has been adduced in the assertions and allegations which have been put forward by the opponents and critics of the trade-agreements program. Naturally, in some individual cases, producers have had to make adjustments to the new rates. Generally speaking, because of the moderate, painstakingly considered, and carefully safeguarded nature of the duty reduction made in the trade agreements, such adjustments have not occasioned serious difficulty. . . . I invite any person to show a single instance of general tariff readjustment either upward or downward, in the entire fiscal history of the Nation, wherein there has been exercised as much impartiality, care, and accuracy as to facts as has uniformly characterized the negotiation of our 33 agreements—or any more solicitude for the welfare of agriculture, labor, business, and the population of the country in its entirety.63

In fact, even the American Tariff League conceded that the trade agreements program had been run fairly.64

Despite the modest overall reduction in duties over the 1930s, the program remained controversial. Many politically active, import-sensitive interests were frustrated in having to deal with the State Department instead of their elected representatives on Capitol Hill. Unlike members of Congress, State Department officials generally resisted pressure from industry groups who wanted exemptions from possible tariff reductions.65 Indeed, these interests had significantly less influence on the executive branch than they had with Congress.66 To administration supporters, this was a good thing: as Senator Harry Truman (D-MO) argued, the administration had “placed the adjustment of tariff duties in the hands of the most competent men available for the purpose, men beyond the reach of political logrolling and tariff lobbying at the expense of national welfare.”67 The RTAA was beginning to change the process of trade policymaking even more than it was changing the schedule of import duties themselves.

Renewing the RTAA in 1937