Chapter Ten

Creating a Multilateral Trading System, 1943–1950

Although Congress delegated trade-negotiating powers to the executive branch through the Reciprocal Trade Agreement Act of 1934, the bilateral agreements reached during the 1930s had only a modest effect in reducing import duties. During World War II, the State Department began making ambitious plans for a multilateral agreement to reduce trade barriers and eliminate discriminatory trade policies around the world. The result was the negotiation of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade in 1947. Despite some concerns about this executive action, Congress recognized that a system of open world trade broadly served the nation’s economic and foreign-policy interests, although lack of Congressional support ended the attempt to establish an International Trade Organization.

A New Order for World Trade

Shortly after winning reelection in November 1940, President Franklin Roosevelt started to move away from a policy of neutrality and began helping Britain in the war against Nazi Germany. Britain did not have the financial resources to pay for military and civilian supplies, but the president was determined to provide some form of assistance. The idea of making loans to Britain, as had been done during World War I, was rejected on the grounds that debt repayments had contributed to the instability of the interwar world economy.1 In December 1940, the president unveiled Lend-Lease, a program of economic and military assistance for Britain and others fighting the Axis powers. Under Lend-Lease, the US government would purchase military supplies and provide them to the Allies under the fiction that they would be “returned” after the war, thereby eliminating the need for repayment. After intense debate, Congress approved the Lend-Lease program in March 1941.

Although recipient countries were not expected to pay for the goods, the United States was not prepared simply to give them away without getting something in return. The legislation required the recipients to provide a “direct or indirect benefit which the president deems satisfactory” as compensation for the assistance.2 This unspecified benefit became known as “the consideration” and was the price that Britain, in particular, would have to pay for American support.

The decision to supply Lend-Lease goods without providing loans or asking for payment meant that the State Department, rather than the Treasury Department, was given responsibility for handling the consideration.3 While the Treasury Department would have primary authority for dealing with postwar monetary and financial issues, the State Department would take the lead in most other postwar arrangements. At the top of the State Department’s list of priorities was the reconstruction of the world trading system. Secretary of State Cordell Hull and his followers believed that efforts to promote growing world trade were needed to help lay the groundwork for a lasting peace.

In a radio address in May 1941, Hull set out his vision of the postwar world, stating that it was “none too early to lay down at least some of the principles by which policies must be guided at the conclusion of the war.” The overarching goal for the postwar period was “the task of creating ultimate conditions of peace with justice.” This would require “a broad program of world economic reconstruction” in which “the main principles, as proven by experience, are few and simple.” Among these principles were that “non-discrimination in international commercial relations must be the rule, so that international trade may grow and prosper” and “raw materials must be available to all nations without discrimination.” Furthermore, “extreme nationalism must not again be permitted to express itself in excessive trade restrictions.” Hull concluded by saying that, “in the final reckoning, the problem becomes one of establishing the foundation of an international order in which interdependent nations cooperate freely with each another for their mutual gain.”4

The outbreak of another war in Europe convinced almost everyone that America’s failure to provide leadership after World War I had contributed to the outbreak of World War II, and government officials were determined not to repeat the mistakes of the past. A key goal was simply to free world trade from the destructive trade policies that had arisen during the 1930s and help the world economy flourish once again. As the dominant world power, the United States was in a strong position to help put world trade on an open and non-discriminatory basis. American officials saw an “unparalleled opportunity to obtain a large and world-wide reduction of trade barriers” after the war and believed that “every possible measure should be explored to take advantage of the present unique opportunity to preserve and strengthen the free-enterprise basis of world trade.”5 In addition to reducing tariffs, eliminating quotas, and dismantling discriminatory trading blocs, American policymakers were deeply concerned about how state trading and state-owned industries had begun to crowd out private US firms in world trade. In such a world, the United States, with its largely private enterprise economy, would operate at a competitive disadvantage in foreign markets.

In May 1941, State Department officials began drafting a formal Mutual Aid Agreement. In exchange for Lend-Lease assistance, State Department officials believed that Britain should cooperate with the United States in establishing an open, multilateral trading system, the cornerstone of which would be non-discrimination. Britain’s participation was critical to the success of this endeavor. Although its global power was severely diminished, Britain still played a leading role in international trade and finance, and led a large number of Commonwealth countries, including Australia, Canada, India, South Africa, New Zealand, and Ceylon. If it rejected the American proposals, Britain could create its own formidable trade bloc based on the preferential tariffs in the Ottawa agreements and the sterling-centered payments system, leaving the United States outside that important sphere. As a result, the State Department under Hull wanted to abolish imperial preferences and significantly reduce other trade barriers. Because Britain now desperately needed American assistance, the State Department was in a much stronger position to make demands on Britain than it had been in 1938, when a reciprocal trade agreement failed to accomplish much.6

In June 1941, the British government dispatched John Maynard Keynes, the brilliant economist and influential adviser to the UK Treasury, to Washington to discuss the terms and conditions of the mutual aid agreement. Keynes was the famous author of the General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money (1936), which made a case for activist government policies to maintain economic stability and ensure full employment. At this point, Keynes believed that economic planning would be needed to ensure full employment after the war. Such planning, in his view, would involve controls on international trade, including import quotas and state trading. Keynes was also pessimistic about the prospects for a postwar agreement to ensure open world trade and worried that his country would face severe balance of payments problems after the war. Therefore, he went into the negotiations convinced that Britain would long be dependent upon its privileged bilateral trade relationships within the sterling bloc to conduct its foreign trade.

When Keynes was sent to Washington, Britain’s main objective was simply to postpone any specific commitments on postwar economic policy.7 But American officials were not easily diverted from their goal, and Assistant Secretary of State Dean Acheson presented Keynes with a draft aid agreement in July 1941. In exchange for assistance, article 7 of the draft stated that postwar arrangements “shall be such as to not burden commerce between the two countries but to promote mutually advantageous economic relations between them and the betterment of world-wide economic relations; they shall provide against discrimination in either the United States or the United Kingdom against the importation of any product originating in the other country; and they shall provide for the formulation of measures for the achievement of these ends.”8 Keynes asked whether this implied that imperial preferences, exchange controls, and other trade measures would be restricted in the postwar period. Acheson replied that it did, but assured Keynes that “the article was drawn so as not to impose unilateral obligations, but rather to require the two countries in the final settlement to review all such questions and to work out to the best of their ability provisions which would obviate discriminatory and nationalistic practices and would lead instead to cooperative action to prevent such practices.”9

This exchange produced a long outburst from Keynes, who was dismayed at what he perceived to be an attempt to force unilateral obligations on Britain when it wanted to keep imperial preferences and might need various trade controls to survive in the postwar world.10 Keynes made no promises and told Acheson that the British government was divided over postwar trade policy; some wanted a return to free trade, another group (including Keynes) believed in the use of import controls, and a third group wanted to preserve imperial preferences.11

In fact, Keynes was shocked by the State Department proposals and privately dismissed the draft of article 7 as the “lunatic proposals of Mr. Hull.”12 To him, the Americans seemed to believe in an outdated ideology of limited government intervention that ignored the new reality that governments would need extensive trade controls to ensure economic stability. Keynes (1980, 239) rejected one State Department memo on trade as “a dogmatic statement of the virtues of laissez-faire in international trade along the lines familiar forty years ago, much of which is true, but without any attempt to state theoretically or to tackle practically the difficulties which both the theory and the history of the last twenty years [have] impressed on most modern minds.”13

The clash between Keynes and Acheson over imperial preferences would be repeated at nearly every bilateral meeting over the next six years. For example, a few weeks later, in August 1941, President Roosevelt and Prime Minister Winston Churchill met off the coast of Newfoundland, Canada, to issue a joint declaration on the purposes of the war against fascism and the guiding principles to be followed after the war. Churchill presented a first draft of what became known as the Atlantic Charter, which included a pledge that the two countries would “strive to bring about a fair and equitable distribution of essential produce around the world.”14 Undersecretary of State Sumner Welles tried to introduce tougher language that called for the “elimination of any discrimination.” Roosevelt softened this to say that mutual economic relations would be conducted “without discrimination,” but Churchill insisted that discrimination could be eliminated only “with due respect for existing obligations.”15

Over the strong objections of Welles, Roosevelt accepted this compromise language. As a result, the final version of the Atlantic Charter stated that the countries “will endeavor, with due respect for their existing obligations, to further the enjoyment by all States, great or small, victor or vanquished, of access, on equal terms, to the trade and to the raw materials of the world which are needed for their economic prosperity.” Hull (1948, 975–6) was “keenly disappointed” with this language because the “with due respect” qualification “deprived the article of virtually all significance since it meant that Britain would continue to retain her Empire tariff preferences against which I had been fighting for eight years.” Hull’s State Department would not give up its attack on imperial preferences, which in their view “combined the twin evils of discrimination and politicization of foreign trade.”16

At the same time, Roosevelt urged Churchill to conclude the mutual aid agreement soon, telling him that there was no specific obligation to eliminate imperial preferences, just a commitment to negotiate in good faith over the issue.17 This assurance helped Churchill to persuade his Cabinet to approve the Mutual Aid Agreement, which was signed in Washington in February 1942. Article 7 stated that, in exchange for American assistance, the countries agreed “not to burden commerce between the two countries, but to promote mutually advantageous economic relations between them and the betterment of world-wide economic relations,” and they also agreed to action, “open to participation by all other countries of like mind, directed to the expansion, by appropriate international and domestic measures, of production, employment, and the exchange and consumption of goods, which are the material foundations of the liberty and welfare of all peoples; to the elimination of all forms of discriminatory treatment in international commerce, and to the reduction of tariffs and other trade barriers.” Unfortunately, article 7 continued to be interpreted differently by American and British officials. The State Department viewed it as an implicit promise to abolish imperial preferences, whereas the British government viewed it merely as a pledge to discuss the issue.18

The signing of the Mutual Aid Agreement allowed both sides to focus on bringing the article 7 obligation into effect. British policymakers wanted to come up with their own trade-policy proposals before American officials became wedded to their own plan. In July 1942, James Meade, an economist with the Economic Section of the War Cabinet Secretariat, wrote a short memorandum entitled “Proposal for an International Commercial Union.”19 Meade proposed a multilateral trade convention with three key features: (1) open membership to all states willing to carry out the obligations of membership, (2) no preferences or discrimination (with an exception for imperial preference) among the participants, and (3) a commitment to “remove altogether certain protective devices against the commerce of other members of the Union and to reduce to a defined maximum the degree of protection which they would afford to their own home producers against the produce of other members of the Union.” Meade’s proposal circulated in the British government and generally received approval, with the reservation that Britain would retain the right to impose import quotas if it faced balance of payments difficulties. Meade’s proposal formed the basis for the country’s negotiating position with respect to article 7.20

Meanwhile, US proposals for the implementation of article 7 were delayed through 1942 because of America’s entry into the war after the attack on Pearl Harbor. The delay continued into 1943, when the State Department was focused on getting Congress to renew the RTAA (discussed in chapter 9). Finally, in September 1943, a British delegation arrived in Washington to meet with their American counterparts to discuss trade matters. Officials from the UK Board of Trade and the War Cabinet’s Economic Section, including economists James Meade and Lionel Robbins, met with Harry Hawkins of the State Department and officials from other federal agencies on commercial policy issues. In parallel discussions, John Maynard Keynes and other UK Treasury officials met with Harry Dexter White of the Treasury Department on postwar financial and exchange rate issues.21 These officials represented the staff level, not the political level, of their governments, meaning that these were exploratory discussions to prepare the ground for higher-level negotiations.

The main issues in the commercial policy discussions were tariffs and preferences, quantitative restrictions, investment, employment policy, cartels, commodity agreements, and state trading. With respect to tariffs and preferences, the United States favored bilateral negotiations to reduce duties on a selective, product-by-product basis, in order to avoid reductions on sensitive products, as had been the practice under the RTAA. Britain strongly favored multilateral tariff reductions on an across-the-board basis in order to free up international trade to the fullest extent possible. British officials thought that the more cautious American approach, coupled with the insistence on safeguards and escape clauses, would limit the potential for tariff reductions to expand international trade. As the discussions progressed, the British representatives began to persuade their counterparts about the merits of a broader multilateral approach. US officials did not rule out such an approach, and Hawkins himself seemed to favor it, but it ran counter to the traditional bilateral negotiations that had been pursued under the RTAA.22 The two sides had a wider gap on preferences and matters such as quantitative restrictions: the United States opposed them, but Britain wanted the option of using them for balance of payments purposes.

Still, the discussions were fruitful, and both sides agreed that they had a solid basis for moving forward. As a result, the interagency Special Committee on Relaxation of Trade Barriers issued an interim report in December 1943 that began with a succinct statement of the prevailing view among American officials:

A great expansion in the volume of international trade after the war will be essential to the attainment of full and effective employment in the United States and elsewhere, to the preservation of private enterprise, and to the success of an international security system to prevent future wars. In order to create conditions favorable to the fullest possible expansion of international trade, on a non-discriminatory basis, it will be necessary for nations to turn away from the trade-restricting and trade-diverting practices of the inter-war period and to cooperate in bringing about a reduction of the barriers to trade erected by governments during that period. International trade cannot be developed to an adequate extent unless excessive tariffs, quantitative restrictions on imports and exports, exchange controls, and other government devices to limit trade are substantially reduced or eliminated. Moreover, if this is not done, there may be a further strengthening of the tendency, already strong in many countries before the war, to eliminate private enterprise from international trade in favor of rigid control by the state.23

The report stated that “the most promising means of reducing, eliminating, or regulating these various types of trade restrictions, on a world-wide basis, is the negotiation among as many countries as possible of a multilateral convention on commercial policy” and noted that the United States was the only country that could lead the world in this direction. It proposed “a substantial reduction of protective tariffs in all countries”; the abolition of import quotas, which “are among the devices most destructive of international trade and least conformable to a system of private enterprise”; “the elimination of all forms of discriminatory treatment in international trade,” particularly imperial preferences; the establishment of principles for state trading; the elimination of export subsidies; and the creation of an international commercial policy organization as “essential to the successful operation of the proposed convention.”

However, plans for postwar trade arrangements materialized slowly, because priority was given to establishing the United Nations (at Dumbarton Oaks, Washington, DC) and the international monetary system (at Bretton Woods, New Hampshire). Only by October 1944 was a sketch of a multilateral commercial convention circulating within the government. The draft suggested that the United States propose a 50 percent horizontal tariff reduction, subject to a 10 percent floor, and the elimination of tariff preferences and import quotas, with some exceptions. The proposed convention would also deal with foreign exchange controls, state trading (ensuring equality of treatment), and subsidies (both export and domestic subsidies would be phased out, with some exceptions). President Roosevelt himself specifically instructed Hull to include provisions on restrictive business practices.24

To this point, Congress and the public were largely unaware of the ambitious plans that the Roosevelt administration had been developing with respect to postwar trade policy. In November 1944, Acheson testified before Congress in one of the first public discussions of the administration’s postwar commercial policy proposals. Acheson (1944, 660) began by warning that “the pre-war network of trade barriers and trade discrimination, if allowed to come back into operation after this war, would greatly restrict the opportunities to revive and expand international trade. Most of these barriers and discriminations are the result of government action. Action by governments, working together to reduce these barriers and to eliminate these discriminations, is needed to pave the way for the increase in trade after the war, which we must have if we are to attain our goal of full employment.” With the approaching transition from war to peace, he continued, the world was “presented with a unique opportunity for constructive action in cooperation with other countries. . . . We therefore propose to seek an early understanding with the leading trading nations, indeed with as many nations as possible, for the effective and substantial reduction of all kinds of barriers to trade.”

Acheson described the US objectives as the elimination of discriminatory treatment in trade, the abolition of import quotas and prohibitions, the reduction of tariffs, and the establishment of rules with respect to government monopolies and state trading. In addition, he anticipated the creation of an international organization to study world trade problems and recommend solutions. “We propose, in other words, that this Government go on with the work which it has been doing during the last 10 years, even more vigorously, with more countries, and in a more fundamental and substantial way,” Acheson (1944, 660) concluded. Even though no specific policy actions were imminent, Acheson set the stage for the renewal of the RTAA in 1945: “In order to achieve this, we need to continue and to extend the efforts that we have made, through the reciprocal trade agreements program, to encourage an expansion of private foreign trade on a non-discriminatory basis.”

The 1945 Renewal of the RTAA

By the presidential election of 1944, the end of World War II was in sight, and political attention shifted away from the military campaign and toward postwar foreign policy. The Democratic platform stated that “world peace is of transcendent importance” and pledged to “extend the trade policies initiated by the present administration,” but provided no specifics.25 The Republican platform revealed a further, if highly qualified, step toward accepting the trade agreements program and the possibility of further tariff reductions negotiated by the president:

If the postwar world is to be properly organized, a great extension of world trade will be necessary to repair the wastes of war and build an enduring peace. The Republican Party, always remembering that its primary obligation . . . is to our own workers, our own farmers and our own industry, pledges that it will join with others in leadership in every co-operative effort to remove unnecessary and destructive barriers to international trade. We will always bear in mind that the domestic market is America’s greatest market and that tariffs which protect it against foreign competition should be modified only by reciprocal bilateral trade agreements approved by Congress.

This suggested that the Republicans accepted the idea of reciprocity but still rejected the unconstrained delegation of authority to the president. If this caveat was not enough to hamper the program, however, the party also pledged to “maintain a fair protective tariff on competitive products so that the standard of living of our people shall not be impaired through the importation of commodities produced abroad by labor of producers functioning upon lower standards than our own.”26

The 1944 election kept the Democrats in control of Congress and Roosevelt as president. With the election settled, the State Department began preparing for the renewal of trade-negotiating authority under the RTAA, which was due to expire in June 1945. For the first time, this renewal would take place without Cordell Hull. After serving as Secretary of State for eleven years, Hull retired from public life in November 1944. Hull had championed the reciprocal trade agreements program from its inception, and this transition could have marked a setback for the program within the State Department and administration. Yet Hull’s immediate successors continued to believe that the program served the national economic interest and furthered the country’s foreign-policy goals. In fact, the new assistant secretary of state for economic affairs, Will Clayton, embraced the cause of non-discriminatory trade liberalization with even greater zeal than Hull. A successful cotton broker, Clayton came from the Southern Democratic tradition in favor of freer trade. As Clayton (1963, 501) later put it, “I have always believed that tariffs and other impediments to international trade were set up for the short-term, special benefit of politically powerful minority groups and were against the national and international interest.” In December 1944, Clayton wrote to the retired Hull, “The first letter I sign on State Department stationary is to you. I want to assure you that your foreign policy is so thoroughly ingrained in my system that I shall always work and fight for it.”27

The political conditions for the 1945 renewal were favorable: Roosevelt had just won an unprecedented fourth term as president, the Democrats still controlled Congress with large majorities, and public opinion favored America’s global leadership to ensure a lasting peace. A Gallup poll found that 75 percent of those questioned supported continuing the trade agreements program, and just 7 percent were opposed, with 18 percent expressing no opinion. When asked if the program should be used for further tariff reductions, 57 percent answered yes, 20 percent no, and 23 percent had no opinion.28

Yet the 1945 renewal of the RTAA was unlike any previous one because it would provide the statutory basis for postwar tariff negotiations. There were two sensitive features to the administration’s proposal: the magnitude of the tariff reduction allowed and the method of tariff reduction permitted. The State Department decided to ask for authority to reduce import duties by up to 50 percent from their 1945 rates, not from the 1934 rates, as in previous renewals. This new tariff-cutting authority was sought because the 50 percent maximum reduction in tariffs specified in the original 1934 act had been made on about 42 percent of dutiable imports in previous reciprocal trade agreements, leaving little room for additional tariff cuts under the old authority.29

State Department officials also debated whether to stick with reducing tariffs on a selective, product-by-product basis or to propose reducing tariffs on a horizontal (across-the-board) basis. The selective basis granted in previous RTAA renewals had been designed to avoid reductions that might harm certain politically powerful, import-sensitive industries. As a result of discussions with Britain and Canada, however, officials had been persuaded that a horizontal tariff reduction would be a more efficient method of reducing import duties. This approach was written into the draft RTAA renewal legislation that the administration circulated for congressional consideration.

In early March 1945, senior State Department officials conferred with key Democratic leaders on Capitol Hill. The initial reaction of House Speaker Sam Rayburn, Ways and Means Committee Chairman Robert Doughton, and others was reported to be “very discouraging.” While the Democratic leadership saw no problem with a three-year renewal of the negotiating authority under section 1 of the draft legislation, or even with the new 50 percent tariff reduction authority in section 2, they regarded section 3, permitting a horizontal as opposed to selective tariff reductions, as problematic. While congressional leaders “seemed to like the objective of the section,” a State Department memo reported, “they were fearful that its inclusion would complicate and prolong Congressional consideration” of the new 50 percent authority and “make it very difficult, if not impossible, to get section 2 unqualified by some form of Congressional approval.” The congressional leaders “did not close the door to section 3 but Departmental officers who met with them came away with the feeling that the leaders felt very strongly that it should be dropped.”30 This left administration officials pondering whether to seek authority to reduce tariffs by up to 50 percent on a selective basis, or to reduce them by a smaller amount on a horizontal basis. State Department staff who had worked on trade matters during the war pressed to keep both, but given the reaction on Capitol Hill, Acheson and Clayton decided to ask for the authority to reduce tariffs by up to 50 percent on a selective basis only.31

Late that month, Roosevelt formally requested the renewal of the RTAA for three years. In making the request, the president stated that “we cannot succeed in building a peaceful world unless we build an economically healthy world” and that “trade is fundamental to the prosperity of nations.” Therefore, he continued,

The reciprocal trade agreement program represented a sustained effort to reduce the barriers which the Nations of the world maintained against each other’s trade. If the economic foundations of the peace are to be as secure as the political foundations, it is clear that this effort must be continued, vigorously and effectively. . . . The purpose of the whole effort is to eliminate economic warfare, to make practical international cooperation effective on as many fronts as possible, and so to lay the economic basis for the secure and peaceful world we all desire.32

Roosevelt died a month later, making this his last statement on trade policy. But his death did little to change US policy, because his successor, Harry Truman, assured continuity. As a Democratic Senator from Missouri, Truman had always faithfully supported the RTAA. In his first press conference as president, just days after taking office, Truman affirmed, “I am for the reciprocal trade agreements program. Always have been for it. I think you will find in the record where I stood before, when it was up in the Senate before, and I haven’t changed.” At the same time, Truman did not understand all the details of the negotiations or even the issues at stake. After Clayton briefed him on the status of the postwar plans for commercial policy, Truman sighed, “I don’t know anything about these things. I certainly don’t know what I’m doing about them. I need help.”33

The stakes in the 1945 RTAA renewal were much greater than in any previous renewal. The Ways and Means Committee began hearings in mid-April and heard from eighty-nine witnesses, thirty-three of whom favored the renewal (seven were administration officials). Clayton testified that without American leadership, an open multilateral trading system would likely be supplanted by economic blocs and government barter arrangements, both of which distorted trade and were “contrary to our deepest convictions about the kind of economic order which is most conducive to the preservation of peace.”34 Among the groups that testified in favor were the American Farm Bureau Federation, the Congress of Industrial Organizations (United Automobile and Aircraft Workers), and the Chamber of Commerce, groups that saw the advantages of larger export markets in the postwar world. The witnesses against the bill included representatives from some labor groups and small- and medium-sized producers from specific industries, such as glass and pottery, wool growing and processing, textiles and shoes, lumber, cattle, and sugar.

In favorably reporting the bill, the Democratic majority stressed the opportunity to create a new system for postwar world trade. The Republican minority denied that they were economic isolationists but worried about imports harming domestic industries. They accused the Democrats of having “bowed to the demands of the State Department” and claimed that they had “been overreached by the soft talk of world planners and globocrats who, we believe, would put the American worker, the American farmer, and the American businessman on the international auction block.”35

Robert Doughton (D-NC), who had been the Ways and Means chairman in 1934 when the original RTAA had been passed, began the debate on the House floor by stating that “the whole idea of the Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act is to find a better market for our surplus products in a world freer from economic barriers, which means fuller employment, larger profits, and a higher standard of living.” He argued that “opponents of the bill admitted that they had not been hurt by the reductions in tariff rates already made, but expressed fear that sometime in the distant and uncertain future they might suffer because of duties lowered under trade agreements. Fear was the text, the sermon and the song of the opposition.”36

Some Republicans stated that they would support a renewal, but only if the new tariff-cutting authority allowed for in section 2 was removed. Leading the opposition, Harold Knutson (R-MN) warned against deep tariff cuts on employment grounds: “The chairman spoke eloquently about wanting to provide jobs for the returning veterans. Please tell me how you are going to provide jobs if you transfer our payrolls to Czechoslovakia, France, the United Kingdom, China, Germany, Russia, and India?” Charles Plumley (R-VT) said, “I feel very strongly that now more than ever the United States needs reasonable barriers in the nature of protective tariffs against the flood of goods from destitute and devastated areas, manufactured and produced at starvation wages supporting a standard of living we will not tolerate and with which we cannot compete.” He added, “America can best help the world by being prosperous and strong, and we can remain neither if we surrender our home market to the pauperized labor of all the world.”37

Dean Acheson was unimpressed by the Congressional debate, which speculated more about the potential impact of imports on domestic industries than it focused on the foreign-policy goal of strengthening the free world through cooperative measures to expand trade. Acheson (1969, 107) wrote that he found it “a dreary and wholly unrealistic debate. Few of the claimed virtues of the bill were really true and none of the fancied dangers. The true facts lay in a different field from that where the shells from both sides were landing.” On the third day of the debate, Acheson (1969, 107) wrote, “I have had a day of frenzied lobbying on the Hill. We are in real trouble and may or may not come through tomorrow. We are trying to get a letter from the president in which he lays his political head on the block with ours. It will be interesting to see if he signs it.”

On the final day of the House debate, Knutson proposed deleting all of section 2 of the proposed bill, the new 50 percent tariff-cutting authority, which was “the crux of the whole fight.”38 Anticipating this motion, House Speaker Sam Rayburn took the unusual step of addressing the House from the floor, warning that “there is a big chance here to make a big mistake.” Rayburn argued that the trade agreements program had to be strengthened to ensure postwar cooperation on economic matters. He then read a letter from President Truman pledging that American industry and labor would not be sold out in any trade agreement. The president wrote,

I assume there is no doubt that the act will be renewed. The real question is whether the renewal is to be in such a form as to make the act effective. For that purpose the enlargement of authority provided by section 2 of the pending bill is essential. I have had drawn to my attention statements to the effect that this increased authority might be used in such a way as to endanger or “trade out”’ segments of American industry, American agriculture, or American labor. No such action was taken under President Roosevelt and Cordell Hull, and no such action will take place under my presidency.39

The proposed amendment to eliminate section 2 was narrowly rejected by a vote of 197–174. A swing of just twelve members of the House could have reversed the outcome of this crucial vote and brought down the plans for significant trade liberalization after the war. Galvanized by the president’s appeal, the Democratic leadership helped defeat the remaining amendments that would have given Congress veto power over any agreement, reduced or eliminated the new authority, or otherwise eviscerated the bill, with close but somewhat larger majorities.

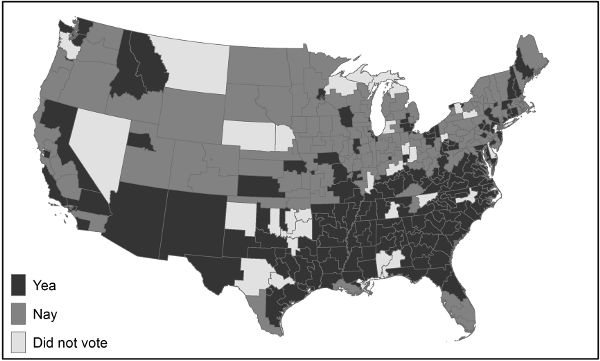

At about 6:30 p.m., on May 26, 1945, the House voted 239–153 to renew the RTAA for three years. As usual, the final vote was largely along party lines: Democrats voted 203–12 in favor, and Republicans voted 139–33 against. Although the final margin was comfortable, Acheson (1969, 107) noted that “this does not tell the true story. It was very close on the critical amendments which would have killed the bill. Our toughest one was an amendment to strike out the additional authority given the President to reduce tariffs.” Figure 10.1 shows the House vote, with support mainly coming from the Democratic South, as usual, but with some new support also coming from the Northeast, where manufacturing industries hoped to benefit from expanding postwar exports.

Figure 10.1. House voting on the RTAA renewal, May 26, 1945. (Map courtesy Citrin GIS/Applied Spatial Analysis Lab, Dartmouth College.)

The renewal then moved to the Senate, where it faced more dangers. In the Finance Committee, Democrats defeated Republican amendments to reduce the authority to two years and require congressional approval of trade agreements, but Robert Taft (R-OH) persuaded the committee, in a 10–9 vote, to eliminate section 2 of the bill, and three of eleven Democrats voted against the president. Acting Secretary of State Joseph Grew criticized the committee’s action and told the press that, without section 2, the renewal would be “an empty symbol of our hopes for cooperation with the rest of the world in an economic field.”40

On the Senate floor, the Democratic leadership insisted that unless the new 50 percent negotiating authority were reinstated, the renewal would be meaningless. Taft said that he agreed that the Smoot-Hawley rates were too high and supported the trade agreements program, but opposed the authority to reduce tariffs by an additional 50 percent because the existing tariff cuts had not been tried under normal conditions. “If we reduce the rates by 50 percent, . . . the country will be hurt,” he worried. “We have the responsibility of doing all we can to prevent our people being driven out of work.”41 The Democratic majority managed to save section 2 of the bill by a 47–33 vote and then defeated another six hostile amendments, including a requirement that the Senate ratify all trade agreements, a prohibition on any cuts in duties on agricultural commodities, and the imposition of import quotas on textiles.

On June 20, 1945, “after what seemed like a millennium of talk” in Acheson’s (1969, 108) view, the Senate approved the extension by a 54–21 vote. Democrats voted 38–5 in favor, along with one Progressive, while Republicans voted 16–15 against. Thus, at this critical juncture, 15 of 31 (48 percent) Senate Republicans broke ranks and supported the renewal, even though some had voted for the limiting amendments. As Edward Johnson (R-CO) said, “I don’t know how it happens, but somehow it always seems that a day or two before you come to voting on reciprocal trade you always have enough votes to beat it, but then when you vote somehow all your votes disappear and it passes.”42

The Republican split on trade policy in 1945 was driven largely by a swing of Northern Republicans behind the RTAA, particularly in the northeast, whose states had an above-average concentration of export-oriented producers.43 A simple comparison of Senate Republican voting in 1934 and 1945 makes this point. The propensity of Midwest Republicans to vote for the RTAA was unchanged: six of fourteen Midwest Republicans voted for the RTAA in 1934 (the only Republicans to do so) and eight of twenty Midwest Republicans voted for the renewal in 1945. However, the propensity of northeastern Republicans to support the RTAA increased dramatically: in 1934, not one of the fifteen Northern Republicans favored the RTAA, but six of nine Northern Republicans did so in 1945. With the Republicans dropping their pledge to repeal the RTAA and ending their attacks on its constitutionality, some cross-party support for the program was beginning to emerge, at least in the Senate. Indeed, if the RTAA was to survive, it would need some cross-party appeal at some point, because eventually the Republicans would return to power.

Harry Hawkins later wrote that the 1945 renewal “marks the high point in the legislative basis of the trade-agreements program.”44 However, he noted, “this enactment took place when the war was drawing to a close—at a time when there was a shortage of goods rather than serious market competition, when the creation of a permanent peace was still widely regarded as an attainable goal, and when peaceful trade among nations was widely recognized as an important foundation for international peace.” These unique circumstances facilitated its passage. Even so, securing Congress’s support for the RTAA had not been easy, and changing conditions would only make its renewal more difficult in the future.

Toward a Multilateral Trade Agreement

Just days after Congress renewed the RTAA, Hawkins, now posted at the US Embassy in London, informed his British counterparts that Congress had approved legislative authority to undertake significant tariff reductions, but only on a selective basis, with no horizontal tariff cuts. Therefore, the United States proposed going ahead with a “multilateral-bilateral” approach, wherein countries would negotiate bilaterally on a product-by-product basis with the principal supplier of a good in question and then generalize the resulting tariff reductions to other participating countries via the unconditional MFN clause.45 British officials were sorely disappointed at this news, which was a blow to their hopes for a large, across-the-board multilateral tariff reduction. The British were also pessimistic about the length of time it would take to negotiate bilaterally, citing the protracted 1938 trade negotiations between the two countries.

The United States also briefed Canadian officials on this development. Norman Robertson, Canada’s Undersecretary of State for External Affairs and a staunch supporter of an open, multilateral trading system, was “deeply disappointed and dismayed” by the news that a horizontal tariff reduction would be impossible. Selective tariff reductions, the Canadians emphasized, would “emphasize the sanctity of protectionism” and make countries “adopt the same careful and cautious attitude toward the reduction or removal of tariffs” and “obscure the truth that trade barrier reduction is also of benefit to the country doing the reducing.”46

Yet Canadian officials also made a suggestion that soon took on enormous consequence. If the multilateral-bilateral approach had to be taken, they thought it would be undesirable to have many countries at the bargaining table. In Canada’s view, “a general conference of all countries might be dangerous, since the views of the many small countries might unduly weaken the bolder measures which the large trading nations might find it possible to agree upon. . . . judging from past experience, the presence at a general international conference of the less important, and for the most part protectionist-minded, countries, would inevitably result in a watering-down of the commitment which a smaller number of the major trading nations might find it possible to enter into.”47 Therefore, Canadian officials suggested that a small “nuclear” group of eight to twelve countries that were deeply committed to reducing trade barriers be convened first. Until Canada’s suggestion, the State Department had envisioned a single, large multilateral gathering that would negotiate tariff reductions, establish rules about trade policy, and create an International Trade Organization (ITO). Canada proposed moving in two steps: a smaller group would negotiate a reduction in trade barriers first, and then a larger group would finalize the text of an agreement creating an ITO.

This idea had an immediate impact on American policy. In July 1945, the Executive Committee on Economic Foreign Policy recommended abandoning the multilateral-bilateral approach and adopting instead a “selective nuclear multilateral-bilateral” approach.48 Under this approach, about a dozen countries would negotiate bilateral agreements for selective tariff reductions and reach informal agreement on rules dealing with tariff and non-tariff barriers to trade. This agreement would then be presented to a larger international conference that would create the ITO. Thus, by July 1945, the United States had a rough conception of the process by which it could move from draft proposals to negotiated agreements through a two-track procedure that would lead to a General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade as distinct from an International Trade Organization.

Despite protesting the limitations on US negotiating authority, Britain was still a reluctant partner, especially as a new Labour government confronted the country’s severe economic problems. What rekindled the stalled discussions between the two countries was President Truman’s abrupt decision in August 1945, after Japan’s surrender ended World War II, to terminate Lend-Lease aid to Britain and the allies. The decision stunned the British government, which still lacked the ability to pay for critical imports of food, fuel, and raw materials. Keynes (1979, 410) warned that, without financial assistance, Britain was facing a “financial Dunkirk.” He was immediately dispatched to the United States to secure a loan that would help finance Britain’s balance of payments shortfall.

The British loan negotiations took place in Washington in September–November 1945, with parallel discussions over article 4 and commercial policy. The US trade negotiators handled the contentious issue of imperial preferences clumsily. Assistant Secretary of State Clayton implied that Britain had agreed to abolish imperial preferences in the Mutual Aid agreement, which was not the case, and implicitly threatened to deny Britain financial assistance if it did not eliminate them, a stand the British viewed as blackmail. When Britain resisted, American officials backed down and accepted the position that elimination of preferences was not a condition for financial assistance.

Despite this friction, these Anglo-American commercial policy discussions proved to be a critical breakthrough that ended two years of inaction. By November, the two sides issued a joint statement that “action for the elimination of preferences will be taken in conjunction with adequate measures for the substantial reduction in barriers to world trade on a broad scale” and that existing commitments would not stand in the way of actions to reduce preferences.49 More importantly, the two sides agreed on the outline of a trade-policy charter that would be presented to other governments for consideration.

In December 1945, the State Department published its “Proposals for Expansion of World Trade and Employment,” the first public disclosure of the administration’s plans. The proposals sought to address the four factors held responsible for the diminished volume of world trade: government trade restrictions, private trade restrictions (cartels and combinations), disorderly markets for primary commodities, and irregularity in domestic production and employment. Regarding the first factor, the proposals stated that “barriers of this sort are imposed because they serve or seem to serve some purpose other than the expansion of world trade. Within limits they cannot be forbidden. But when they grow too high, and especially when they discriminate between countries or interrupt previous business connections, they create bad feeling and destroy prosperity. The objective of international action should be to reduce them all and to state fair rules within which those that remain should be confined.”50 The proposals called for an international conference on tariffs to be held “not later than the summer of 1946” and noted that “no government is ready to embrace ‘free trade’ in any absolute sense. Nevertheless, much can usefully be done by international agreement toward reduction of governmental barriers to trade.”

The United States then did two things. First, the State Department invited fifteen countries to participate in a meeting of “nuclear” countries that would negotiate tariff reductions. However, domestic politics intruded. In April 1946, Truman was asked to sign off on the list of items contemplated for duty reduction, while also being warned that “experience has shown that once this list is published, minority interests will put strong pressure on the Administration for commitments that particular tariff rates will not be cut.”51 This request triggered alarm bells at the White House and higher levels of the State Department because of the upcoming midterm elections. As a result, Truman and Secretary of State James Byrnes decided to postpone the negotiations among the “nuclear” countries until early 1947. The rationale was that the administration wanted Congress to pass the British loan before the State Department gave the required ninety-day public notice about the tariff items that would be subject to negotiation. If Congress approved the loan in mid-1946, as anticipated, then the public notice and public hearings on the potential tariff reductions would come uncomfortably close to the congressional elections. To avoid stirring up political controversy over the trade proposals, Truman and Byrnes decided to issue the public notice immediately after the election, meaning that the negotiations could not begin until early 1947. Clayton sent an impassioned memo asking to adhere to the original schedule; he wanted to accelerate the process, supposedly quipping that “we need to act before the vested interests get their vests on.”52 However, the decision had been made, and this plea failed.

Second, in February 1946, the United States proposed convening a general United Nations conference on trade and employment. The goal of the conference was not to engage in tariff negotiations, but to prepare a charter for an International Trade Organization, although the committee drafting an agenda would work in concert with the smaller nuclear group that was exchanging tariff concessions. The first meeting of the UN Preparatory Committee for the International Conference on Trade and Employment convened at Church House in London during October–November 1946.53 This preparatory meeting was the first one in which other countries (including Australia, India, China, Ceylon, Lebanon, Brazil, Chile, and several others) could help shape the multilateral convention on commercial policy. The main goal of the developing countries was to ensure that the rules did not prevent them from using import quotas to promote objectives related to employment and economic development. As a result, new chapters of the draft ITO charter were included on both issues.

At the landmark London meeting, the participants agreed on most of the provisions of a draft charter for an ITO, although the draft was not yet binding on governments. The participants agreed to limit the use of quantitative restrictions, exchange controls, and export subsidies, except under specific circumstances. Other chapters set out broad rules regarding state trading, economic development, restrictive business practices, intergovernmental commodity agreements, and the structure of the ITO. The Preparatory Committee recommended a process to implement “certain provisions of the charter of the International Trade Organization by means of a general agreement on tariffs and trade” among a smaller group of countries, perhaps the first mention of a general agreement separate from the ITO.54

In November 1946, shortly after the midterm elections, President Truman approved the plans for the meeting to negotiate tariff reductions, signing off on the publication of the list of goods on which the United States was prepared to offer concessions. The State Department announced that the tariff negotiations would take place in Geneva in April 1947, with at least eighteen countries participating. The public hearings on the proposed tariff reductions were not nearly as contentious as officials had feared. But the outcome of the November election was stunning: a Republican sweep gave them control of Congress for the first time since 1932, temporarily ending a long era of Democratic political dominance. Given the past Republican support for protective tariffs and hostility toward the RTAA, this electoral shift threatened the impending Geneva negotiations. Although the Republicans could not revoke the negotiating authority granted in 1945 (they could not override a presidential veto of such a measure), the new majority in Congress could severely complicate the negotiations.

Indeed, conservative Republicans immediately called for postponing the April meeting and repealing the RTAA in the future. In December 1946, Senator Hugh Butler (R-NE) wrote a forceful letter to Clayton arguing that the voters had repudiated the administration’s tariff-reduction program, and therefore the Geneva negotiations should “be temporarily suspended until the new Congress shall have an opportunity to write a new foreign trade policy.” As Butler put it, “The attempt to use the authority of the Trade Agreements Act, previously wrested from a Democratic Congress, to destroy our system of tariff protection, seems to me a direct affront to the popular will expressed last month.”55

Clayton refused to postpone the Geneva meeting and countered every point in Butler’s letter, maintaining that

far from intending “to destroy our system of tariff protection,” our Government is entering into the projected trade negotiations for the purpose of insuring that tariffs, rather than discriminatory import quotas, exchange controls, and bilateral barter deals, shall be the accepted method by which nations regulate their foreign trade. If it were not for the initiative which our Government has taken in this matter, the world would be headed straight toward the deliberate strangulation of its commerce through the imposition of detailed administrative controls. I need hardly tell you that such a development would be seriously prejudicial to the essential interests of the United States.

Clayton also shot back, “We are fighting for the preservation of the sort of world in which Americans want to live—a world which holds out some promise for the future of private enterprise, of economic freedom, of rising standards of living, of international cooperation, of security and peace. The trade agreements program is an instrument whose aid we need if we are to achieve these ends.”56

In January 1947, Thomas Jenkins (R-OH) introduced a resolution to postpone the Geneva negotiations until the Tariff Commission could report on the impact of lower tariffs on domestic industries. Given the length of time it would take the commission to undertake such a study, the Jenkins resolution would delay the Geneva conference indefinitely. To prevent a serious rift from developing between Congress and the administration, Senators Arthur Vandenberg (R-MI) and Eugene Millikin (R-CO), chairmen of the Foreign Relations and Finance Committees, respectively, met with Acheson and Clayton. A former isolationist who had become a strong proponent of a bipartisan foreign policy, Vandenberg had opposed the RTAA in the 1930s but now supported multilateral cooperation to reduce trade barriers.57 However, he feared that the State Department put too much weight on foreign-policy considerations and discounted the potential harm to domestic producer interests when it negotiated tariff reductions. The Senate leaders wanted to limit the executive’s authority over tariff matters without jeopardizing the entire trade agreements program.

These discussions produced a compromise that allowed the Geneva conference to go forward. In February 1947, Vandenberg and Millikin issued a statement arguing that it would be “undesirable” to postpone the April conference in view of the extensive preparations for it. They also suggested that legislative changes to the RTAA would be “made more appropriately” in 1948 when it was up for renewal. However, they noted “considerable sentiment for procedural improvements leading to more certain assurance that our domestic economy will not be imperiled by tariff reductions and concessions.” In particular, they requested five procedural changes to address the fear that a “tariff adequate to safeguard our domestic economy may be subordinated to extraneous and overvalued diplomatic objectives.”58 These included allowing the Tariff Commission to determine the point beyond which import duties should not be reduced for fear of harming a domestic industry, something that became known as “peril points.” More importantly, Vandenberg and Millikin wanted the mandatory inclusion of an escape-clause procedure that would make it easier for domestic industries to receive temporary protection if they were faced with injury as a result of imports.

A few weeks later, President Truman issued an executive order embracing most of these recommendations. The order established an administrative process for considering and acting upon complaints from domestic firms about the harmful impact of foreign competition as a result of negotiated tariff reductions. It required that, in all future trade agreements, the United States could withdraw or modify concessions “if, as a result of unforeseen developments and of the concession granted by the United States on any article in the trade agreement, such article is being imported in such increased quantities and under such conditions as to cause, or threaten, serious injury to domestic producers of like or similar articles.”59 The process would work as follows. Any domestic producer that felt harmed by foreign competition could petition the government for relief from imports. The Tariff Commission would investigate the complaint and make a recommendation to the president “for his consideration in light of the public interest.” If the Tariff Commission found grounds for restricting imports to prevent injury, the president had the option of restricting imports or doing nothing.

In announcing the new procedures, Truman insisted that “the provisions of the order do not deviate from the traditional Cordell Hull principles,” but “simply make assurance doubly sure that American interests will be properly safeguarded.” The executive order did not incorporate all of the senators’ suggestions, in particular one in which the Tariff Commission would recommend tariff limits (or “peril points”) below which a negotiated reduction should not go. While Butler rejected the president’s action as inadequate, Vandenberg and Millikin welcomed it as “a substantial advance in the legitimate and essential domestic protections which should be part of an equally essential foreign trade program.”60

The compromise was one of several critical moments in the process of forging a bipartisan consensus in favor of creating a system of open trade after World War II. The agreement avoided a repeat of the conflict between a Democratic president and a Republican Congress that occurred after World War I. This particular compromise established an important component of US trade policy—the “escape clause”—which provided that domestic interests could be safeguarded against the possible adverse effects of trade liberalization.61 Such a safeguard was essential in addressing the concerns of some Republicans about the trade agreements program and helped win their acquiescence to the Geneva conference, though not necessarily their support for it.62 It also proved to be a politically useful device for Congress to channel protectionist pressures away from the legislature.

In March 1947, Truman threw his support behind the upcoming Geneva meeting in a speech at Baylor University in Texas. The president stressed the importance of reaching an international agreement on trade policy:

If the nations can agree to observe a code of good conduct in international trade, they will cooperate more readily in other international affairs. Such agreement will prevent the bitterness that is engendered by an economic war. It will provide an atmosphere congenial to the preservation of peace. As a part of this program we have asked the other nations of the world to join with us in reducing barriers to trade. We have not asked them to remove all barriers. Nor have we ourselves offered to do so. But we have proposed negotiations directed toward the reduction of tariffs, here and abroad, toward the elimination of other restrictive measures and the abandonment of discrimination. These negotiations are to be undertaken at the meeting which opens in Geneva next month. The success of this program is essential to the establishment of the International Trade Organization [and] to the strength of the whole United Nations structure of cooperation in economic and political affairs. . . . The negotiations at Geneva must not fail.63

A month later, Dean Acheson, Will Clayton, and Winthrop Brown (chairman of the Committee on Trade Agreements) met with the president to review the tariff concessions that the State Department was prepared to offer at Geneva and discuss the political sensitivities involved, particularly in the case of zinc, woolen goods, and cotton textiles. When told that he could expect strong political protests from some special interests, Truman replied “I am ready for it” and approved the recommendations.64

The General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade

In April 1947, at the Palais des Nations in Geneva, Switzerland, representatives from eighteen countries met to conclude an agreement on the principles for the conduct of trade policy and to negotiate tariff reductions. The United States was anxious to reduce tariffs, ban import quotas, and modify or eliminate imperial preferences. Meanwhile, Western European countries were facing huge balance of payments deficits and wanted the maximum tariff concessions from the United States so that they could increase their exports and earn the precious dollars they needed to purchase the imports. These imports were vital for their economic reconstruction, but they also wanted to retain the right to use trade controls to limit spending on imports because of their balance of payments difficulties.

The negotiation of the proposed General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) proceeded smoothly due to extensive preparatory work.65 The preamble to the agreement stated that trade relations “should be conducted with a view to raising standards of living, ensuring full employment and a large and steadily growing volume of real income and effective demand.” These objectives could be achieved in part “by entering into reciprocal and mutually advantageous arrangements directed to the substantial reduction of tariffs and other barriers to trade and to the elimination of discriminatory treatment in international commerce.”66

Many provisions of the GATT were taken from the reciprocal trade agreements of the 1930s. Article 1 set forth the unconditional most-favored-nation (MFN) clause, which stated that “any advantage, favour, privilege or immunity granted by any contracting party to any product originating in or destined for any other country shall be accorded immediately and unconditionally to the like product originating in or destined for the territories of all other contracting parties.” Exceptions were granted for preexisting preferences, such as imperial preferences and the special trading relationship between the United States and Cuba. Article 2 was the (annexed) schedule of tariff concessions produced by the Geneva negotiations. Article 3 called for national treatment (non-discrimination) in internal taxes and regulations by declaring that they “should not be applied to imported or domestic products so as to afford protection to domestic production.” Article 11 introduced a general ban on import quotas, with exceptions for countries experiencing balance of payments difficulties or when agricultural imports interfered with domestic measures (article 12).

Other provisions in the GATT allowed countries to reimpose trade barriers otherwise prohibited by articles 2 and 11 of the agreement. Article 6 concerned dumping, defined as the selling of goods at “less than the normal value,” and set out procedures for imposing antidumping duties in cases where the dumping “causes or threatens material injury to an established industry . . . or materially retards the establishment of a domestic industry.” Article 19 adopted the US language regarding the escape clause. Other articles contained further qualifications to the principle of non-discrimination and the objective of reducing trade barriers. Article 18 permitted developing countries to impose trade restrictions to foster economic development. Article 20 allowed trade interventions to safeguard public health and safety. Article 21 covered action to protect national security. Many other articles dealt with mundane issues such as marks of origin, customs valuation, goods in transit, the publication and administration of trade regulations, state trading enterprises, and governmental assistance for economic development.

Along with finalizing these rules, the participating countries also negotiated tariff reductions on a bilateral, product-by-product basis. The tariff negotiations were much more contentious than finalizing the text of the general agreement had been. Going into the conference, State Department officials faced the choice of revealing all of the tariff reductions authorized by the president, showing the maximum degree to which the US delegation could reduce duties and thereby minimizing strategic bargaining, or holding some concessions back in the hopes of striking a better deal. As an act of good faith, Clayton decided to put all of the American offers on the table from the start. Other countries professed not to be impressed, held back their offers, and the stalemate began.67

One commodity, wool, took on critical importance. Owing to domestic political sensitivities, the US delegation had no authorization to reduce the wool tariff. As the Geneva conference began, the new Republican Congress was even in the process of enacting legislation that would further tighten restrictions on imported wool in an effort to support domestic prices.68 The House passed the measure in May 1947 by the sizable majority of 151–65, with many Democrats voting in favor. The Senate had already passed similar legislation and, despite strong objections from the administration, the conference committee not only kept the import fee but allowed the president to impose import quotas as well. Though they accounted for just 1 percent of total farm income, wool producers had historically been one of the most politically powerful agricultural groups in Congress.69

The wool legislation could have jeopardized the entire Geneva negotiation. Australia was a major wool exporter, and it was the main commodity on which they sought a US tariff reduction. Outraged that the United States was unwilling to make any concessions on wool and might even restrict imports further, the Australian delegation threatened to walk out of the conference, taking other members of the British Commonwealth with them. This threat was viewed as credible. Clayton flew back to Washington to intervene at the highest political levels. The president granted Clayton and Secretary of Agriculture Clinton Anderson, who supported the bill, fifteen minutes each to make their case. Clayton urged the president to veto the bill, arguing that it would wreck the ongoing negotiations. Anderson urged the president to sign the bill, saying that the Geneva meeting was doomed to failure, and the legislation would help rural farmers. Clayton apparently had the better argument: Truman vetoed the bill on the grounds that it “contains features which would have an adverse effect on our international relations and which are not necessarily for the support of our domestic wool growers.”70

Truman did more than just veto the legislation. He immediately gave Clayton the authority to reduce the wool tariff by 25 percent. The president’s approval of a significant reduction in the wool tariff after Congress had just approved an increase was “the greatest act of political courage that I have ever witnessed,” Clayton (1963, 499) later said. Although Australia grumbled about the small size of the tariff reduction, Truman and Clayton saved the conference with their quick and decisive action. Once the authorization to reduce the wool tariff was made official in August, the stalemate over tariff reductions was broken, and more offers were forthcoming.

With the wool problem resolved, the Geneva negotiations turned to address the largest obstacle to a successful agreement: Britain’s imperial preferences. The elimination of these discriminatory preferences had been a key US objective since the Ottawa Agreements were reached in 1932. Yet the Geneva conference began on an inauspicious note. At an opening press conference, when asked if a 50 percent US tariff reduction would be sufficient incentive to eliminate imperial preferences, the lead British negotiator, Stafford Cripps, replied with a terse “no.”71 Cripps stubbornly defended imperial preferences, partly due to the extreme economic difficulties that Britain faced after the war. He also gave a speech that harshly criticized the United States and disparaged the importance of tariff negotiations and the ITO charter.

The sour British attitude cast a pall over the whole conference.72 In a key meeting in July 1947, Clayton and Cripps clashed over preferences. Clayton insisted that the time had come for Britain to eliminate them, a demand Cripps dismissed out of hand. A US cable described Cripps as “marked by complete indifference bordering on open hostility toward the objectives of the Geneva conference” and that the “vested interests that have been built up under the preferential system are strong, and the United Kingdom has shown no willingness to take the political risks involved in reducing or removing the protection afforded them by the preferences which they enjoy.”73 Clayton was furious over Cripps’s “callous disregard of their commitment on preferences,” and the American team was flabbergasted when Cripps suggested that the United States should withdraw some of its offers if it believed it had not received adequate concessions.74

Fears about the foreign-policy ramifications of a breakdown in the Geneva negotiations, and concerns about Britain’s evident economic weakness, played a key role the negotiation’s end-game. In late August, with the GATT text finalized but the tariff negotiations still deadlocked, Clayton cabled Undersecretary of State Robert A. Lovett in Washington and outlined four options: (1) conclude an agreement without a substantial elimination of preferences; (2) conclude an agreement without a substantial elimination of preferences by withdrawing some US offers on tariff reductions, as twice suggested by Cripps; (3) discontinue negotiations with Britain and seek to conclude agreements with others on multilateral basis; (4) adjourn the tariff negotiations indefinitely.75 Clayton was so upset with the British negotiating stance that he recommended the third option, although his staff strongly disagreed.

Lovett discussed the alternatives with Truman in the Oval Office. The president rejected options 1 and 4 and favored option 2 over 3, and the two agreed that option 2 was the lesser of two evils. In explaining the decision, Lovett made it clear to Clayton that foreign-policy considerations were paramount. In particular, the president and senior State Department officials were worried that a failure at the conference would further weaken Britain’s economic and political position and strengthen that of the Soviet Union.76 The president’s decision, overriding Clayton’s advice to abandon an agreement with Britain because of imperial preferences, brought the Geneva negotiations to a conclusion. To Clayton’s disappointment, Britain’s imperial preferences remained largely intact, as margins were unchanged on 70 percent of Britain exports to the Commonwealth, but he accepted the “practical necessity” of compromise.77

On October 29, 1947, President Truman welcomed the conclusion of the Geneva conference as “a landmark in the history of international economic relations. Never before have so many nations combined in such a sustained effort to lower barriers to trade. Never before have nations agreed upon action, on tariffs and preferences, so extensive in its coverage and so far-reaching in its effects, . . . [and] it confirms the general acceptance of an expanding multilateral trading system as the goal of national policies.”78 Other world leaders also hailed the result. Max Suetens of Belgium, the chairman of the Geneva meeting, praised the meeting as “the most comprehensive, the most significant, and the most far-reaching negotiations ever undertaken in the history of world trade.”79 In Canada, Prime Minister Mackenzie King praised the result as “the widest measure of agreement on trading practices and for tariff reductions that the nations of the world have ever witnessed. . . . For Canada, the importance of the general agreement can scarcely be exaggerated. The freeing of world trade on a broad multilateral basis is of fundamental importance for our entire national welfare.”80 By contrast, British officials were muted in noting the conclusion of the conference.

In the United States, the retired Cordell Hull issued a statement noting his “profound gratification” at the conclusion of the Geneva conference, stating that “the nations which participated in the negotiations have made a long stride toward the goal of economic betterment and world peace.”81 The public also seemed to be pleased with the agreement. At the conclusion of the Geneva negotiations, Gallup (1972, 1:695) reported that only 34 percent of those surveyed had heard of the GATT; of those who had heard, 63 percent approved of the agreement, 12 percent opposed, and 25 percent expressed no opinion.

However, Republicans in Congress were critical of the outcome and made it clear that they would soon attempt to restrict the president’s future authority over trade policy. Millikin worried about the future consequences of the tariff reductions: “In anything resembling normal times, some of the cuts would be catastrophic. For example, they made substantial reductions in the raw material productions of the West which would not be borne in normal times. Copper, livestock, livestock products such as hides and wool, numerous metals, agricultural products—all of these things can be produced cheaper abroad than here.”82 He predicted that Congress would seek to implement the “peril points” provision that Truman had rejected earlier in the year. And Harold Knutson (R-MN), the chairman of the Ways and Means Committee, attacked the Geneva agreement and complained about “the do-gooders who have traded us off for very dubious and nebulous trade concessions that may never be realized.”83

The GATT was an achievement of the State Department and White House, but would not have been possible without the tacit support of key Republicans, particularly Arthur Vandenberg. The GATT also put into practice three long-standing Republican ideas: the notion of reciprocity, the unconditional MFN policy, and the opposition to quantitative restrictions on trade. The RTAA had started the process of trade agreements and tariff reductions; the GATT was a more formal multilateral mechanism that bound import tariffs at lower levels (for three years, later extended indefinitely) and raised the political costs of any attempt to raise them. But what really ensured the preservation of the lower tariffs into the future was that enough Republicans, even after having won control of Congress in the 1946 election, now accepted the trade agreements program and allowed the Geneva negotiations to proceed. Of course, the GATT was neither a treaty nor an organization, but simply a trade agreement put into effect by executive order. As a result, participants were “contracting parties” (not “members”), and the agreement was an interim arrangement to be applied provisionally until Congress approved the ITO Charter.

The Decline in US Tariffs

During World War II, the average tariff on dutiable imports was largely unchanged, standing at 33 percent in 1944. Just six years later, it had fallen to almost 13 percent, a decline of 60 percent, as figure 10.2 shows. What accounts for this enormous drop? How was it politically possible for Congress to have allowed tariffs to fall to their lowest level since 1791?

Figure 10.2. Average tariffs of the United States, 1900–1970. (US Bureau of the Census 1975, series U-211–12.)

The obvious explanation for the decline in tariffs is the 1947 Geneva negotiation. In fact, however, these negotiated reductions in tariff rates were responsible for only a fraction of the decline. The main reason for the postwar decline was the sharp increase in import prices after the war. About two-thirds of the tariffs were specific duties, and rising import prices reduced the ad valorem equivalent of those duties, just as deflation increased the ad valorem equivalent during the Great Depression. In this case, import prices rose 41 percent between 1944 and 1947, and this increase was largely responsible for the sharp decline in the average tariff in the immediate postwar period.84