The map may not be the territory, but it sure helps you to get around.

—Me (PAL)

Just as maps are useful in finding a particular part of the city, maps of the human organism* are important in navigating the landscape of trauma and informing its healing. The groundbreaking work of Stephen Porges, director of the Brain Body Center at the University of Illinois, Department of Psychiatry, has provided an eloquent, well-reasoned and broadly supported “treasure map” of the psychophysiological systems that govern the traumatic state. These same systems also mediate core feelings of goodness and belonging. Porges’s polyvagal theory of emotion58 illuminates the pathways for recovery and integration described in Chapter 5. In addition, his model clarifies why certain common approaches to trauma psychotherapy frequently fail.

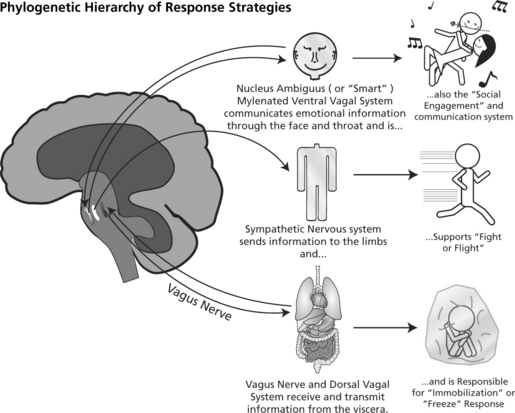

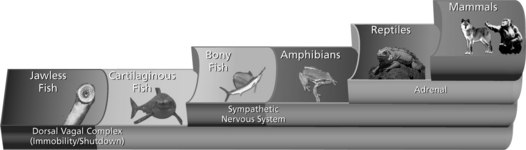

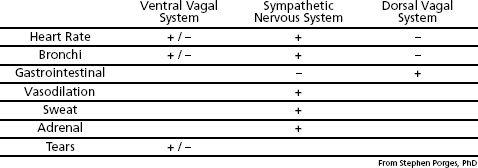

Briefly, Porges’s theory states that, in humans, three basic neural energy subsystems underpin the overall state of the nervous system and correlative behaviors and emotions. The most primitive of these three (spanning about 500 million years) stems from its origin in early fish species.† The function of this primitive system is immobilization, metabolic conservation, and shutdown. Its target of action is the internal organs. Next in evolutionary development is the sympathetic nervous system. This global arousal system has evolved from the reptilian period about 300 million years ago. Its function is mobilization and enhanced action (as in fight or flight); its target in the body is the limbs. Finally, the third, and phylogenetically most recent, system (deriving from about 80 million years ago) exists only in mammals. This neural subsystem shows its greatest refinement in the primates, where it mediates complex social and attachment behaviors. It is the branch of the parasympathetic nervous system that regulates the so-called mammalian or “smart” vagus nerve, which is neuroanatomically linked to the cranial nerves that mediate facial expression and vocalization. This most recently acquired system animates the unconsciously mediated muscles in throat, face, middle ear, heart and lungs, which together communicate our emotions, both to others and to ourselves.59 This most refined system orchestrates relationship, attachment and bonding and also mediates emotional intelligence. Figure 6.1 summarizes the basic mammalian nervous subsystems. For more detail, see Diagram B after this page, which shows the complex wandering of the vagus nerve affecting and being affected by most of the internal organs. The basic functions of these phylogenetic systems are summarized in Figures 6.2a through 6.2d.

Nervous systems are tuned to assess potential risk in the environment—an unconscious evaluative process that Porges calls “neuroception.”‡ If one perceives the environment to be safe, one’s social engagement system inhibits the more primitive limbic and brain stem structures that control fight or flight. After being moderately startled, you might, for example be calmed by another person—as when a mother says to her child, “It’s ok; that was only the wind blowing.”

Generally, when threatened or upset, one first looks to others, wishing to engage their faces and voices and to communicate one’s feelings to secure collective safety. These are called attachment behavior. Attachment is virtually the only defense young children have, as they cannot usually protect themselves by fighting or fleeing. Attachment for security is a general mammalian and primate survival strategy against predation. By dealing with threat in quantity, the individual is less likely to be “picked off.” In addition, if someone in your own group is threatening you, you may first try to “make nice” before resorting to fighting or fleeing.

Simplified Block Diagram of the Polyvagal Components

Figure 6.1

However, when “pro-social” behaviors do not resolve the threatening situation, a less evolved system is engaged. We mobilize our fight-or-flight response. Finally, in this “hierarchy of default”—when neither of the more recently acquired systems (social engagement or fight/flight) resolves the situation, or when death appears imminent—the last-ditch system is engaged. This most primitive system, which governs immobility, shutdown and dissociation, takes over and hijacks all survival efforts.§

Figure 6.2a This figure shows which part of the body is affected by each of the evolutionary subsystems.

The concept of default hierarchies—first described by the preeminent neurologist of the later nineteenth century, Hughlings Jackson60—remains a fundamental principle of neurology‖ and is a primary assumption in Porges’s theory. Basically, Jackson observed that when the brain is injured or stressed, it reverts to a less refined, evolutionarily more primitive level of functioning. If there is subsequent recovery, this regression will reverse, returning the individual to the more refined functions. This is an example of “bottom-up processing,” so important in trauma therapy.

Evolutionary Roots

Figure 6.2b This shows the neural control of the three phylogenetic systems: primitive vagus, sympathetic/adrenal and “smart” (mammalian) vagus.

The more primitive the operative system, the more power it has to take over the overall function of the organism. It does this by inhibiting the more recent and more refined neurological subsystems, effectively preventing them from functioning. In particular, the immobilization system all but completely suppresses the social engagement/attachment system. When you are “scared to death,” you have few resources left to orchestrate the complex behaviors that mediate attachment and calming; social engagement is essentially hijacked. The sympathetic nervous system also blocks the social engagement system, but not as completely as does the immobilization system (the most primitive of the three defenses).

Polyvagal Theory: Phylogenetic Stages of Nervous Control

Figure 6.2c This summarizes the phylogenetic stages of the sympathetic and polyvagal systems.

Immobility and hyperarousal are, as I have explained, organismic responses to threat and prolonged stress. When they are operative, danger (in the case of fight or flight) and doom (with immobility) are what an individual perceives—regardless of the reality of the external situation. The human nervous system does not readily discriminate between a potential source of danger in the environment, such as an abruptly moving shadow, or distress about a situation long past.a Where the distress is generated internally (by muscles and viscera), one experiences an obsessive pressure to locate the source of threat or (when that’s not possible) to manufacture one as a way of explaining to oneself that there is an identifiable source of threat.

Highly traumatized and chronically neglected or abused individuals are dominated by the immobilization/shutdown system. On the other hand, acutely traumatized people (often by a single recent event and without a history of repeated trauma, neglect or abuse) are generally dominated by the sympathetic fight/flight system. They tend to suffer from flashbacks and racing hearts, while the chronically traumatized individuals generally show no change or even a decrease in heart rate. These sufferers tend to be plagued with dissociative symptoms, including frequent spacyness, unreality, depersonalization, and various somatic and health complaints. Somatic symptoms include gastrointestinal problems, migraines, some forms of asthma, persistent pain, chronic fatigue, and general disengagement from life.

Polyvagal Theory: Emergent “Emotion” Subsystems

Figure 6.2d This shows the effect the phylogenetic systems have in either increasing (+ sign) or decreasing (- sign) the activity of the various organ systems.

In some exciting research, the brain activity of people suffering from posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) was recorded by functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) while they were read a “traumatic script,” which was a graphic and detailed description of someone’s serious trauma (such as an accident or rape).61 The fMRI, scanning the location and the intensity of brain activity, portrayed them as a rainbow of colors.b So, for example, blue (cold) colors indicated a relative reduction in brain activity, while red (hot) colors might indicate an increase. The distress of the volunteers was intensified by the fact that their heads were immobilized, confined in a noisy clanging metal basket. In these studies, at least 30% of the subjects exhibited a decrease in activity of the insula and the cingulate cortex. The PTSD of these volunteers was characterized by dissociation and (vagal) immobility. On the other hand, about 70% of the subjects studied suffered primarily from the simpler symptoms of sympathetic hyperarousal and showed a dramatic increase in the activity of these same areas.62 The insula and the cingulate are the parts of the brain that receive sensory information from receptors inside the body (interoception) and form the basis of what we feel and know as our very identity.63 Underactivity portrays dissociation, while overactivity is associated with sympathetic arousal.

In my long clinical experience, I found that many (perhaps even a majority of) persons exhibit some symptoms of both systems. The expression of symptoms appears to depend on a variety of factors, including the type and severity of a person’s trauma, the age at which it occurred, and which traumatic patterns and content were activated during treatment. There are also most likely constitutional and gender factors at play as well. In addition, these symptom constellations tend to change over time and even within a single session.c Most important, treatment must be approached differently according to which of these three systems is activated during sessions and which lie dormant.

To effectively guide the processes of healing and transformation in their clients, therapists must be able to perceive and track the physiological footprints and expressions of these organismic systems. Since each of the hierarchical polyvagal systems has its own unique pattern of autonomic and muscular expressions, therapists need to perceive these indicators—skin color, breathing, postural signs and facial expressions—in order to determine the stage (immobilization, hyperarousal or social engagement) their clients are in and when they are transitioning to another.

As we saw with Nancy in Chapter 2, a patient can undergo a wild roller-coaster ride between the three evolutionary subsystems, which demand parallel changes in strategy.d When, for example, the individual is in sympathetic hyperarousal, the therapist can observe a tightening of the muscles in the front of the neck (particularly the anterior scalenes, the sternocleidomastoids and the upper shoulder muscles), a stiffened posture, a general jumpiness, darting eyes, an increase in heart rate (which can be seen in the carotid artery in the front of the neck), dilation (widening) of the pupils, choppy rapid breathing and coldness in the hands, which may appear bluish particularly at the finger tips, as well as pale skin and cold sweat in the hands and forehead. On the other hand, a person going into shutdown often collapses (as though slumping in the diaphragm) and has fixed or spaced-out eyes, markedly reduced breathing, an abrupt slowing and feebleness of heart rate, and a constriction of the pupils. In addition, the skin often turns a pasty, sickly white or even gray. And, finally, the person who is socially engaged has a resting heart rate in the low to mid-seventies, relaxed full breathing, pleasantly warm hands and a mild to moderate pupil aperture. Therapists are rarely trained to make such observations (though they can get a little coaching from watching episodes of the TV series Lie to Me).

Of the three primary instinctual defense systems, the immobility state is controlled by the most primitive of the physiological subsystems. This neural system (mediated by the unmyelinated portion of the vagus nerve) controls energy conservation and is triggered only when a person perceives that death is imminent64—whether from outside, in the form of a mortal threat, or when the threat originates internally, as from illness or serious injury.e Both of these challenges require that one hold still and conserve one’s vital energy. When this most archaic system dominates, one does not move; one barely breathes; one’s voice is choked off; and one is too scared to cry. One remains motionless in preparation for either death or cellular restitution.

This last-ditch immobilization system is meant to function acutely and only for brief periods. When chronically activated, humans become trapped in the gray limbo of nonexistence, where one is neither really living nor actually dying. A therapist’s first job in reaching such shut-down clients is to help them mobilize their energy: to help them, first, to become aware of their physiological paralysis and shutdown in a way that normalizes it, and to shift toward (sympathetic) mobilization. The next step is to gently guide a client through the sudden defensive/self-protective activation that underlies the sympathetic state and back to equilibrium, to the here-and-now and a reengagement in life.

Generally, as a client begins to exit the freeze state, the second most primitive system (sympathetic arousal) engages in preparation for fight or flight. Recall how Nancy went from sympathetic arousal (her heart rate shooting up wildly) to helpless terror and then abruptly to shutdown (her heart rate dropping precipitately), and then finally to mobilization and discharge when she activated her running muscles and escaped from the image of the tiger. The important therapeutic task in the sympathetic/mobilization phase is to ensure that a client contains these intense arousal sensations without becoming overwhelmed (I described this process in Chapter 5). In this way, they are experienced as intense but manageable waves of energy, as well as sensations associated with aggression and self-protection. These sensory experiences include vibration, tingling, and waves of heat and cold (I described both of these phenomena in Chapter 1 and in my report on Nancy in Chapter 2).

When one is able to ride the sometimes bucking bronco of one’s arousal sensations through, and begin to befriend them in a slow and steady way, one is gradually able to discharge the energy that had been channeled into hyperarousal symptoms. This initial stage and foundational piece of the self-regulation pie, and the basic ingredient for restoring equilibrium, is what brought both Nancy and me out of limbo and back to life. Only after this point of intervention does the social engagement system, the third evolutionary subsystem, begin to come back online. An individual who has been able to move out of immobility, and then through sympathetic arousal, begins to experience a restorative and deepening calm. Along with these sensations of OK-ness and goodness, an urge, even a hunger, for face-to-face contact emerges.f Because that yearning may have been painfully unmet during critical periods of infancy, childhood and adolescence (or may have been associated with shame, invasion and abuse), many traumatized individuals also need particular guidance to negotiate this intimacy barrier. This therapeutic guidance can occur only when it becomes physiologically possible to access the social engagement system—that is, when the nervous system is no longer hijacked by the immobilization and the hyperarousal systems.

The intentional use of a mental or physical health practitioner’s own intact heartfelt human expression can be profoundly therapeutic. In spite of the raw dominance of the vagal immobilization and sympathetic arousal systems in suppressing social engagement, the power of human contact to help change another’s internal physiological state (through face-to-face engagement and appropriate touch) should not be underestimated. Thus, as I discussed in Chapter 1, the pediatrician with the kindly face who sat by my side after my auto accident gave me the glimmer of hope I needed at that exact moment in order to go on.

The gentle power of the human face to soothe the “savage beast” is portrayed in a film with the revealing title Cast Away. Tom Hanks plays the lead character, Chuck Noland, who is marooned on a remote, uninhabited island as the sole survivor of an airplane crash. Also washed ashore is some of the plane’s cargo, which includes a white volleyball printed with the Wilson brand name. He aptly names the ball “Wilson” and offhandedly adopts it as his mascot.g To his surprise, it begins to take on a life of its own, becoming the confidant for Noland’s innermost thoughts. One day, in a fit of impotent rage, Noland throws the ball into the sea, but then—realizing how deeply he has become attached to Wilson—he dives in to retrieve it. Back on the beach, he affectionately draws childlike facial features65 (eyes, mouth and nose) on the round volleyball.h Wilson now becomes his most intimate companion, sharing his troubled thoughts, deepest yearnings and anguished feelings of loneliness and despair, as well as his joyful triumphs. Noland’s bonding with Wilson is eerily reminiscent of the ethologist Konrad Lorenz’s orphan ducklings and their powerful attachment (imprinting) to a white ball after their mother was removed from their life shortly after their hatching.66 Once they were permanently bonded to the ball as their surrogate mother, they preferred it even to a live, soft, feathery mother duck.

Finally, Hanks’s character realizes that the island is apparently outside of any shipping lanes and that he will never be rescued if he remains on it. In his ill-fated attempt to leave on a raft he has made, Wilson is swept away during a fierce storm, and Hanks is inconsolable in his grief.

Face-to-face, soul-to-soul contact is a buffer against the raging seas of inner turmoil. It is what helps you calm any emotional turbulence. So, in spite of the vast primal power of the immobilizing and hyperarousal systems, therapists should recognize the power of facial recognition and social engagement in calming their clients, and in meeting people’s deepest emotional needs and motivating many behaviors, both conscious and unconscious. Lest I leave you in the lurch, Noland, at death’s door, is finally rescued. Upon returning home he takes all of the surviving packages and, traveling across the country, delivers them to their rightful owners. Yes, that’s right: face-to-face.

Deprived of face contact (and even a person who is blind from birth uses his or her hands to “see” other faces), we are (like Hanks’s character) cast away, adrift from our deepest needs and sense of purpose in life. Most of us would go insane without some kind of face-to-face contact. Along with facial recognition, the sound, intonation and rhythm of the human voice (prosody) have an equally calming effect. Even with clients who cannot tolerate face-to-face contact, the sound of the therapist’s voice—like the mother’s cooing to her infant—can be deeply soothing and enveloping.

In a revealing commentary, Dr. Horvitz, a leading computer scientist, recently demonstrated his voice-based system, which asks patients about their symptoms and responds with empathy.67 When a mother said that her child was having diarrhea, the animated face on the screen said, in a supportive tone, “Oh, no; sorry to hear that.” This simple acknowledgment put the woman at ease and helped her to interact with the program in a secure and empowered manner. One physician told Horvitz that “it was wonderful that the system responded to human emotion … I have no time for that.” Perhaps this computer system is the equivalent of Chuck Noland’s volleyball. Its programmed “empathy” was certainly helpful but a meager substitute for the real thing. It is a depressing commentary on the growing alienation of our postmodern, twenty-four-hour texting culture. While so many of our young keep in touch with dozens of people every hour in cyber-relationships, authentic face-to-face engagement is clearly on an apocalyptic wane. How sad and disturbing that the physician believed he didn’t have the minuscule time for such basic and salutary human communication—contact that would help humanize them both. If practiced regularly, it might even help both patient and physician stave off Alzheimer’s or other forms of dementia.68

Many traumatized individuals, and especially those who have been chronically traumatized, live in a world with little or no emotional support, making them even more vulnerable. After a devastating event—be it violence, rape, surgery, war or an automobile accident—or in the aftermath of a childhood of protracted neglect and abuse, traumatized individuals, even those who share a residence with a friend, family member or intimate partner, tend to isolate themselves. Alternatively, they cling desperately to other people in the hope that they will somehow help and protect them. Either way, they are bereft of the real intimacy—the salubrious climate of belonging—that we all crave and need in order to thrive. Traumatized individuals are, at the same time, terrified of intimacy and shun it. So either way, avoidant or clinging, they are unable to maintain the balanced, stable and nurturing affiliations we all need, the egalitarian bond characterized by the Jewish theologian Martin Buber as the “I-thou” relationship.69

When their loneliness becomes too stark, traumatically disconnected individuals may seek increasingly more unrealistic (and sometimes dangerous) “hook-ups.” They see each new relationship possibility (or impossibility) as providing the caring protection that will calm their inner anxieties and buoy up their fragile sense of self. Having had a neglectful or abusive childhood predisposes them to chaotic relationships. These individuals continue to look for love “in all the wrong places”—a folly the song reminds us of. Even when one’s idealized (fantasy) rescuers become abusive, one seems oblivious to the early signs of that abuse and becomes increasingly ensnared in a damaging liaison precisely because it is so familiar or “like family.”

Correcting such maladaptive patterns is the bane of many trauma therapists, who look on helplessly as their clients are repeatedly triggered and seduced into self-destructive affairs, reenacting their original trauma. Many therapists hold to the hope that they can somehow provide their clients with the positive, affirmative (I-thou) relationship that will assuage a client’s fractured psyche and restore his or her wounded soul to wholeness. However, what often happens is that a client’s dependency upon the therapist escalates and gets entirely out of hand–as shown so conspicuously in the gem of a film What About Bob? (1991). In it, Bob, the “abandoned” client, is so dependent, and his feelings about being left alone are so intolerable, that he tracks down his psychiatrist like a sleuth and follows him on a family vacation on Cape Cod.

On the other hand, if a client experiences the therapist, who is supposed to be a healer, as a “proxy” abuser, the therapy often culminates in the client’s profound disappointment and/or seething rage. Traumatized individuals are not made whole through the therapeutic relationship alone. Even with the best of intentions, and highly developed empathic skills, a therapist often misses the mark here. The polyvagal theory and the Jacksonian principle of dissolution help us to understand why and how this happens.70 When the traumatized person is locked in either the immobilization response or the sympathetic arousal system, the social engagement function is physiologically compromised; the former, in particular, both inhibits sympathetic arousal and can almost completely suppress the social engagement system.

A person whose social engagement system is suppressed has trouble reading positive emotions from other people’s faces and postures and also has little capacity to feel his or her own nuanced positive affects. Thus, one finds it difficult to know if that other person can be trusted (whether he or she is threatening or safe, friend or foe). According to the polyvagal theory, being in shutdown (immobility/freezing/or collapse) or in sympathetic/hyperactivation (fight or flight) greatly diminishes a person’s capacity to receive and incorporate empathy and support. The facility for safety and goodness is nowhere to be found. To the degree that traumatized people are dominated by shutdown (the immobility system), they are physiologically unavailable for face-to-face contact and the calming sharing of feelings and attachment. And while immobilization is rarely complete (as it is, for example, in catatonic schizophrenia), its ability to suppress life and one’s capacity for social engagement is extreme. A young man describes his dark plight as follows: “I feel all alone in the universe, dissociated from the human race … I am not sure that I even exist … Everyone is part of the flower; I am still part of the root.”i It is not surprising that, try as they may, many traumatized clients are little able to receive support and caring from their well-intentioned therapists—not because they don’t want to, but because they are stuck in the primitive root of immobility with its greatly reduced capability for reading faces, bodies and emotions; they become cut off from the human race.

For this reason such a client may not be readily calmed by the positive feelings and attitude of empathy the therapist provides, and may even perceive the therapist as a potential threat. Unable to recognize caring feelings in the face and posture of others, such a client finds it extremely difficult to feel that anyone is safe or can really be trusted. And when high hopes are placed on the therapist, one small misstep or inadvertent fumble on the latter’s part can bring the entire relationship crashing down.

As highly dissociated and shut-down clients involuntarily retreat, they experience additional self-recrimination and shame. Tormented by this loss of control, they are unable to accept and respond to the warmth and security offered by their therapist and may engage in unproductive transference and “acting out.” The inherent disconnect that then occurs often leaves both client and therapist bewildered and frustrated, feeling that they are failing in their respective roles. The client may perceive this breakdown as a devastating confirmation of his or her inadequacy, adding to a lifetime of (many perceived) failures. Therapists may also feel confused, helpless, inadequate and self-reproaching. Such situations, where the two partners are locked against one another, can readily become intractable Gordian knots. These therapeutic cul-de-sacs may eventually result in termination of treatment.

Shut-down and dissociated people are not “in their bodies,” being, as we have seen, nearly unable to make real here-and-now contact no matter how hard they try. It is only when they can first engage their arousal systems (enough to begin to pull them up, out of immobility and dissociation), and then discharge that activation, that it becomes physiologically possible to make contact and receive support. Fortunately, there is a way to escape the immobilization system’s domination of the two less primitive systems—a way that healing practitioners must learn to exercise.

This therapeutic solution is supported by Lanius and Hopper’s fMRI work mentioned earlier.71 This compelling research, recording activity in the part of the brain associated with the awareness of bodily states and emotions, makes a clear differentiation between sympathetic arousal and dissociation in traumatized subjects. The brain area associated with awareness of bodily states and emotions is called the right anterior insula and is located in the frontal part of the limbic (emotional) brain, squeezed in directly under the prefrontal cortex—the locus of our most refined consciousness. The research showed that the insulaj is strongly inhibited during shutdown and dissociation, and it confirmed that these traumatized individuals are unable to feel their bodies, to differentiate their emotions, or even to know who they (or another person) really are.72 On the other hand, when subjects are in a state of sympathetic hyperarousal, this same area is highly activated. This dramatic increase in the activity of the right anterior insula strongly suggests a clear differentiation of little or no body awareness (in immobility/shutdown and dissociation) to a kind of “hyper-sensation” in sympathetic arousal. In addition, the sympathetic state, at least, provides the possibility of coherent awareness, processing and resolution. These data support the crucial steps to trauma resolution outlined in Chapter 5 (Step 5) and further clarify the strategy of helping clients move from shutdown to mobilization while learning to manage their physical (bodily) sensations as they shift into sympathetic arousal.

A related, and seminal, research study was carried out by Bessel van der Kolk.73 He and his colleagues read a traumatic story to a group of clients and compared two brain regions in each (measured with fMRI). The researchers found that the amygdala, the so-called fear or “smoke detector,” lit up with electrical activity; at the same time, a region in the left cerebral cortex, called Broca’s area, went dim. The latter is the primary language center—the part of the brain that takes what we are feeling and expresses it with words. That trauma is about wordless terror is also demonstrated in these brain scans. Frequently when traumatized people try to put their feelings into words—as when, for example, one is asked by the therapist to tell about his or her rape—they speak about it as though it had happened to someone else (see the story of Sharon in Chapter 8). Or clients try to speak of their horror, then become frustrated and flooded, incurring more shutdown in Broca’s area, and thus enter into a retraumatizing feedback loop of frustration, shutdown and dissociation.

This language barrier in traumatized individuals makes it especially important to work with sensations—the only language that the reptilian brain speaks. Doing so both helps people to move out of shutdown and dissociation and diminishes a client’s frustration and flooding when working with traumatic material.

The body must be doing something to keep the insula, the cingulate cortex, and Broca’s area online. Even though the capacity for engagement is inhibited by the sympathetic nervous system, it is not thoroughly squelched in the debilitating way it was by the more primitive immobility system. In sympathetic arousal, clients are better able to respond to their therapist’s promptings and suggestions, as well as to be more receptive to his or her calming presence. In turn, it is this very receptivity that helps to attenuate the sympathetic arousal. When a client begins to make the breakthrough out of immobility and into sympathetic arousal, the astute therapist seizes this momentary opportunity, first by detecting the client’s shift and then by facilitating the awareness of his or her transition. The therapist endeavors to enlarge the client’s awareness of what is going on in him- or herself while simultaneously helping the client avoid being overwhelmed by the intense sympathetic arousal. Such guidance helps clients move out of immobility and through complete cycles of activation, discharge/deactivation and equilibrium (steps 7 and 8 in Chapter 5). In this way, the individual learns that what goes up (gets activated) can, and will, come down. Clients learn to trust that moderate activation unwinds on its own when one doesn’t avoid and recoil from it: that is, when one doesn’t interfere with the natural course of one’s sensations of arousal. Thus a therapist can seize the day—by giving clients the gift of this bodily experience.

Whatever increases, decreases, limits or extends the body’s power of action, increases, decreases, limits or extends the mind’s power of action. And whatever increases, decreases, limits or extends the mind’s power of action, also increases, decreases, limits or extends the body’s power of action.

—Spinoza (1632–1677), Ethics

Many therapists, realizing how difficult it is to reach highly dissociated and shut-down clients, have developed valuable cognitive and emotional methods to help connect with them.74 Somatic approaches can also be enormously useful, or even critical, in this healing effort. They help clients move out of immobility, into sympathetic arousal, through mobilization, into discharge of activation and then finally onward to equilibrium, embodiment and social engagement. The following somatically based awareness exercises begin this process by helping individuals move out of shutdown and dissociation.

The first is a simple exercise that clients can do by themselves to help enliven their body-sense and minimize shutdown, dissociation and collapse. By being able to practice in the privacy of their own homes, clients can spare themselves potential embarrassment or shame in their awakening process. This exercise, and those that follow, are meant to be done regularly, over time, for maximum benefit—and therapists should practice the exercises themselves.

For ten minutes or so (a few times a week), take a gentle, pulsating shower in the following way: at a comfortable temperature, expose your body to the pulsing water. Direct your awareness into the region of your body where the rhythmical stimulation is focused. Let your consciousness move to each part of your body. For example, hold the backs of your hands to the shower head, then the palms and wrists, then your head, shoulders, underarms, both sides of your neck, etc. Try to include each part of your body, and pay attention to the sensation in each area, even if it feels blank, numb, or uncomfortable. While you are doing this, say, “This is my arm, head, neck,” etc. “I welcome you back.” You can also do this exercise by gently tapping those same parts of your body with your fingertips. When done regularly over time, this and the following exercises will help reestablish awareness of your body boundary through awakening skin sensations.

A sequel to this shower exercise involves bringing boundary awareness into the muscles. You start by using a hand to grasp and gently squeeze the opposite forearm; then you squeeze the upper arm, the shoulders, neck, thighs, calves, feet, etc. The important element is to be mindful of how your muscles feel from the inside as they are being squeezed. You can begin to recognize the rigidity or flaccidity of the tissue as well as its general quality of aliveness. Generally, tight, constricted muscles are associated with the alarm and hypervigilence of the sympathetic arousal system. Flaccid muscles, on the other hand, belie how the body collapses when dominated by the immobilization system. In the case of flaccid muscles, you need to linger and gently hold them, almost as though you were holding a baby. With the practice of gentle, focused touch and resistance exercises, you can learn to bring life back into those muscles as the fragile fibers learn to fire coherently and thus vitalize the organism.

These two exercises are best done regularly, several times per week. As body consciousness grows, so, too, will a more palpable sense of boundary awareness, as well as greater aliveness. For some clients, classes in gentle yoga or martial arts, such as tai chi, aikido or chi gong, can be beneficial in restoring connection to their bodies and defining body boundaries. For these classes to be helpful, it is important that the teacher have some experience in working with traumatized individuals.

Most psychotherapists work with clients when both are sitting in chairs. Since sitting requires little proprioceptive and kinesthetic information to maintain an erect posture, the body easily becomes absent, disappearing from its owner. Recall the fMRI study of Lanius and Hopper, where dissociated patients showed a great reduction of activity in the parts of the brain (insula and cingulate) that register body sensations. In contrast, a standing position requires one to engage in at least a modicum of interoceptive activity and awareness to maintain one’s balance via proprioceptive and kinesthetic integration. Often, this simple change in stance can make the difference between whether or not a client is able to stay present in the body while processing difficult sensations and feelings. Another supportive variant is to invite the client to sit on a suitable-sized gymnastic ball. Since balancing on a ball requires making multiple adjustments to maintain equilibrium, not only does it help one to be in touch with internal sensations due to the feedback from this pliable surface, but in addition, explorations in muscle awareness, grounding, centering, protective reflexes and core strength bring a whole new dimension to developing a body consciousness. Naturally, the therapist has to be sure that the client is present and integrated enough not to fall off the ball and possibly sustain an injury.

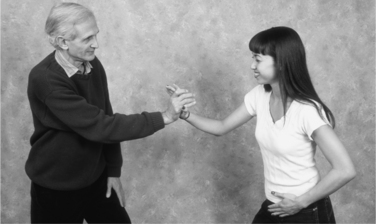

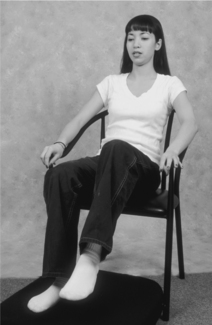

The following is another technique to help clients remain conscious of their bodily sensations while at the same time learning how to manage assertion and aggression. First, have your client stand up and face you. It is important to check whether she is comfortable with the distance between the two of you. Next, ask the client to notice what she is aware of as her feet contact the ground. Then encourage her to broaden her perception, moving up through her ankles, calves and thighs. To encourage a sense of groundedness, continue this exercise by proposing a slow and gentle weight shift from one foot to the other. Also, you could suggest that your client think of her feet as suction cups (like the feet of a frog) flexibly rooted in the earth. Next, have the client bring her attention to her hips, spine, neck, and then head. Now have her notice how her shoulders hang from her neck like a tent. Awareness of breathing is evoked as the client is asked to sense her shoulders as they gently rise and fall with each breath. Now bring her attention to her chest and belly; and, using breath, help the client locate the center of gravity in her abdomen. Again have her slowly shift her weight from side to side between her two feet, and then have her add a slight sway from front to back. This type of movement requires a fairly sophisticated proprioceptive ability (joint position) and sense of muscle tension (kinesthesia).k As your client practices this, have her imagine a plumb line from her center down to the floor between her feet. Finally, have her notice how this line moves with her gentle swaying. A client who has developed this centered awareness is ready to move to the position shown in Figure 6.3a.l

Figure 6.3a Physical awareness exercise to cultivate the experience of healthy aggression. Hand positioning for evoking healthy aggression (in Figure 6.3a).

Figure 6.3b

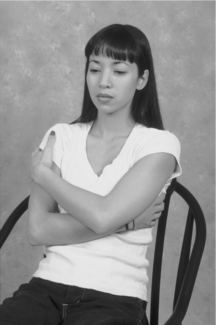

The idea, now, is to have the client feel her feet on the ground, feel her center and then push firmly, but gently, into the therapist’s hand (see Figure 6.3b). As the therapist, you will offer just enough resistance to allow the client to sense herself pushing out from her center. You will be asking her to feel how the movement seems to originate from her belly and is expressed through her shoulders and into her arms and hands. Continue to check with the client to ascertain whether the resistance feels right—not too much or too little—and whether the distance feels safe enough. Should the client feel unsafe, first ask whether she can indicate where she would like you to stand. Now suggest that she try to notice where in her body it feels unsafe or unstable, and then to notice what happens if she brings her attention back to her feet and legs. Ask her to attempt to recapture a sense of the grounding established at the beginning of the exercise. When your client is able to feel a sense of safety, ask her to notice where in her body she feels safe now and to describe how she experiences her (often brand-new) sense of self. Repeat this resistance activity several times, having your client push with both hands, until there is a loosening up and developing sense of confidence. The next progression of this exercise involves more of a give and take between the therapist and the client, each of you alternately pushing and receiving the movement. When one’s body is able to experience a relaxed sense of strength, one’s mind is able to experience a relaxed sense of focused alertness.

The next somatic tool is designed to help posttraumatic stress disorder survivors learn that even when they feel paralyzed, there is a latent active response of running and escaping inside of them. A new experience of this dormant defense contradicts the traumatic encounter with being frozen and trapped (see Figure 6.4). It is essential for the therapist to have a pillow placed on the floor that is firm and thick enough to safely absorb the impact of vigorous running movements if they should occur. Begin by asking the client to run in place from a seated position. Encourage him to gently alternate his legs, lifting and stepping down, as he attends to the way his hips, legs, ankles and feet organize themselves from the inside out. The key element is to have the client stay fully aware of his legs as he makes this movement. In other words, the client needs to remain present to his bodily experience, rather than just mechanically performing or dramatizing the act of running. This is not role-playing, but rather an intentional heightening of kinesthetic and proprioceptive perception, telling a client how his body and brain together are designed to protect him by engaging innate escape movement patterns. Later, when the client brings up traumatic material that involves feeling paralyzed and unable to escape, have him put his story aside and, again, feel his legs. Have him begin to run in place as before in order to incorporate his new empowered awareness. In this way, the direct experiencing of “body wisdom” develops as the muscles discharge their latent energy.

Figure 6.4 Safely practicing the running escape response to counter feeling trapped and helpless. It is important to cultivate the awareness of running.

It has long been known that the brain can influence our internal organs. When this process goes awry, one becomes the unfortunate bearer of what has been referred to as psychosomatic illness. The principal idea of the one-way effect of mind over body evolved as the “psychosomatic paradigm” of the 1930s through 1950s. Today, it remains conventional wisdom, and few doctors deny that an overwrought mind and unsettled emotions affect the human body in the form of “functional” disorders, which include high blood pressure, gastrointestinal symptoms, chronic pain, fibromyalgia and migraines, as well as a multitude of other, so-called idiopathic diseases. In 1872, however, long before the rise of psychosomatic medicine, the amazing Charles Darwin realized that there was a vital two-way connectivity between brain and body:

When the heart is affected it reacts on the brain; and the state of the brain reacts through the pneumo-gastric on the heart; so under any excitement, there will be much mutual action and reaction between these, the two most important organs in the body.75 [italics mine]

The “pneumo-gastric” nerve Darwin speaks of is none other than the vagus nerve described in Porges’s polyvagal theory. The primitive (unmyelinated) vagus nerve of the immobilization system connects the brain with most of our internal organs. This enormous nerve is the second largest nerve in our body, comparable in size to the spinal cord. In particular, this nerve largely serves the gastrointestinal system, influencing ingestion, digestion, assimilation and elimination. It also significantly affects the heart and lungs, as Darwin clearly recognized.

Furthermore, embedded within the lining of the gastrointestinal wall itself there is a massive plexus of nerves. This complex network of sensory, motor and interneurons (those nerve cells that connect between the sensory and motor neurons) integrates the digestive and eliminative organs so that they function coherently.m This intricate system has about the same number of neurons and white matter as does a cat’s brain. Because of this complexity, it has sometimes been called the second or enteric brain; the other three are the reptilian (instinctual), the paleomammalian (limbic/emotional) and the primate (enlarged, rational) neocortex. The enteric nervous system is our oldest brain, evolving hundreds of millions of years ago. It produces many beneficial hormones, including 95% of the serotonin in the body,n and thus is a primary natural medicine factory and warehouse for feel-good hormones.76

Amazingly, as much as 90% of the vagus nerve that connects our guts and brains is sensory! In other words, for every one motor nerve fibero that relays commands from the brain to the gut, nine sensory nerves send information about the state of the viscera to the brain. The sensory fibers in the vagus nerve pick up the complex telecommunications going on in the gut and relay them, first up to the (mid) brain stem and then to the thalamus. From there, these signals virtually influence the entire brain, and subliminal “decisions” are made that profoundly influence our actions. Many of our likes and dislikes, our attractions and repulsions, as well as our irrational fears, are the result of these implicit computations in our internal states.

It can be said that humans have two brains: one in the gut (the enteric brain) and the “upstairs brain,” sitting within the vaulted dome of the cranium. These two brains are in direct communication with each other through the hefty vagus nerve. And if we go with the numbers—nine sensory/afferent nerves to every one motor/efferent nerve—our guts apparently have more to say to our brains (by a ratio of 9:1) than our brains have to say to our guts!p

Let’s look more deeply at the functions of this massive nerve, which not only connects organs and brain, but functions primarily in the direction of gut to brain. Why is it even important for the body to talk to the brain in the first place? From the perspective of evolution (and the general parsimony of nature), it is unlikely that such a myriad of nerve fibers would be allotted to making bidirectional communication possible if that linkage weren’t vitally important.

Most of us have experienced butterflies in our stomach when asked to make a public speech. On the other hand, some people are known for “having gall,” while others are quite “bitter” or “bilious.” And then too, at times we may have “knots in our guts” and are “twisted up inside.”q Or we may be “heavyhearted” or nursing a “heartache.” And blessed are the times when we have surrendered to the pure mirth of a spontaneous “belly laugh.” Or, again, we may be “openhearted and filled with warmth in our bellies,” feeling an inner peace and love for the whole world. On the occasions when we have accomplished notable achievements, our chests may “swell with pride.” Such is the variety of poignant messages emanating from our viscera.

When aroused to fight or flight (sympathetic arousal), our guts tighten, and the motility of the gastrointestinal system is inhibited. After all, there is no sense in spending a lot of metabolic energy on digestion when it is best used to speed up the heart’s rhythm and to strengthen its contraction, as well as to tense our muscles in readiness for impending action. When we are mortally threatened, or when the threat is internal (say, from the flu or from eating a bacterially infected food), our survival response is to vomit or to expel the contents of our intestines with diarrhea, and then to lie still so as to conserve energy. It seems possible that prey animals also resort to this reaction when a predator suddenly springs on it from within striking distance. In this case, the violent expulsion of the animal’s intestinal contents may actually lighten its weight and give it a better chance of escaping. This fraction-of-a-second advantage could mean the difference between life or death. I have seen this happen on several occasions when a mountain lion has lunged at a group of deer drinking from the North St. Vrain River, which runs behind my Colorado home.

The powerful effects of both the sympathetic and the vagus nerves on the viscera serve critical survival functions. The activation of these two systems is meant to be brief in response to acute emergency. When they become stuck (in either sympathetic overdrive or vagal overactivity), the survival function is drastically subverted: one may end up suffering from a painfully knotted gut, as in the case of persistent sympathetic hyperarousal, or be tormented by spasms of twisting cramps and disruptive diarrhea in chronic vagal hyperactivity.r When equilibrium is not restored, these states become chronic, and illness ensues.

Together, these complex systems (the vagus and the enteric plexus), not unlike a great marriage, put gut and brain in either blissful harmony or in dreadful unending battle. When there is a coherent balance between the two, the hedonic (concerned with pleasure or pleasurable sensations) fulcrum is tipped toward heaven; when the regulatory relationship is disordered, the gates of hell are opened wide like the great maw of misery.

Our nervous system assesses threat in two basic ways. First of all, we use our external sense organs to discern and evaluate threat from salient features in the environment. So, for example, a sudden shadow alerts one to a potential risk, while the large looming contours of a bear or the sleek, crouching silhouette of a mountain lion let one know that one is in grave danger. We also assess threat directly from the state of our viscera and our muscles—our internal sense organs. If our muscles are tense, we unconsciously interpret these tensions as foretelling the existence of danger, even when none actually exists. Tight muscles in the neck and shoulders may, for example, signal to the brain that you are likely to be hit. Tense legs, along with furtive eyes, may tell you that you need to run and escape, and taut arms may signal that you’re ready to strike out. We suffer even greater distress when our guts are persistently overstimulated by the vagus nerve. If we are nauseated, twisted in our guts, feel our muscles collapsing, and lack in energy, we feel helpless and hopeless—even though there is no actual decimating threat. In other words, the churning itself signals grave threat and dread to the brain, even when nothing is currently wrong—at least not externally.

Our muscular and visceral states color both our perceptions and our evaluation of the intentions of others. While we may believe that certain individuals will do us no harm, we still feel endangered.s

Even something as neutral as a room, a street corner or a sunlit meadow may seem ominous. Conversely, experiencing relaxed (and well-toned) muscles and belly can signal safety even when a person’s daily affairs are in turmoil. As an illustration of this point, I overheard a person saying after receiving a full-body massage, “The world’s not such a bad place after all. I feel terrific.” While a wonderful massage is a great way to give a person a new way of feeling good, it will take a major shift in the ongoing dialogue on the brain-gut highway to free up more than ephemerally the congestion caused by chronic stress and trauma.

The intense visceral reactions associated with threat are meant to be acute and temporary. Once the danger has passed, these reactions (be it inhibition of gastric motility by the sympathetic nervous system or violent overstimulation of motility by the primitive vagus nerve) need to cease in order to return the organism to equilibrium, fresh and flowing in the here and now. When balance is not restored, one is left in acute and, eventually, chronic distress.

In order to prevent trauma as well as to reverse it when it has already occurred, individuals must become aware of their visceral sensations.t In addition, our gut sensations are vital in orchestrating positive feelings of aliveness and in directing our lives. They are also the source of much of our intuition. As we can learn from traditional, shamanic and spiritual practices, embraced for thousands of years throughout the world, feelings of goodness are embodied directly as visceral sensations. When we ignore our “gut instincts,” it is at our own great expense, if not peril.

In states of immobilization and shutdown, the sensations in our guts are so dreadful that we routinely block them from consciousness. But this strategy of “absence” only maintains the status quo at best, keeping both brain and body hopelessly stuck in an information traffic jam. It is a recipe for trauma and a diminished life, a cardboard existence. The following is another simple exit strategy for undoing the brain/gut knot.

The first seat of our primal consciousness is the solar plexus, the great nerve-centre situated behind the stomach. From this centre we are first dynamically conscious.

—D. H. Lawrence, Psychoanalysis and the Unconscious

Along with multitudes of other people, I have experienced various chanting and ancient “sounding” practices that facilitate healing and help open the “doors of perception.” Singing and chanting are used in religious and spiritual ceremonies among every culture for “lightening the load” of earthly existence. When you open up to chant or sing in deep, resonant lower belly tones, you also open up your chest (heart and lungs), mouth and throat, pleasurably stimulating the many serpentine branches of the vagus nerve.u

Certain Tibetan chants have been used successfully for thousands of years. In my practice, I use a sound borrowed (with certain modifications) from some of these chants. This sound opens, expands and vibrates the viscera in a way that provides new signals to a shut-down or overstimulated nervous system. The practice is quite simple: make an extended “voooo …” (soft o, like ou in you) sound, focusing on the vibrations stimulated in the belly as you complete a full expiration of breath.

In introducing the “voo” sound to my clients, I often ask them to imagine a foghorn in a foggy bay sounding through the murk to alert ship captains that they are nearing land, and to guide them safely home. This image works on different levels. First of all, the image of the fog represents the fog of numbness and dissociation. The foghorn represents the beacon that guides the lost boat (soul) back to safe harbor, to home in breath and belly. This image also inspires the client to take on the hero role of protecting sailors and passengers from imminent danger, as well as giving him or her permission to be silly and thereby play. Most important are the image’s physiological effects. The sound vibrations of “voo” enliven sensations from the viscera, while the full expiration of the breath produces the optimal balance of oxygen and carbon dioxide.77

Begin the exercise by finding a comfortable place to sit. Then slowly inhale, pause momentarily, and then, on the out breath, gently utter “voo,” sustaining the sound throughout the entire exhalation. Vibrate the sound as though it were coming from your belly. At the end of the breath, pause briefly and allow the next breath to slowly fill your belly and chest. When the in breath feels complete, pause, and again make the “voo” sound on the exhalation until it feels complete. It is important to let sound and breath expire fully, and then to pause and wait for the next breath to enter (be taken) on its own, when it is ready. Repeat this exercise several times and then rest. Next, focus your attention on your body, primarily on your abdomen, the internal cavity that holds your organs.

This “sounding,” with its emphasis on both waiting and allowing, has multiple functions. First of all, directing the sound into the belly evokes a particular type of sensation while keeping the observing ego “online.” People often report various qualities of vibration and tingling, as well as changes in temperature–generally from cold (or hot) to cool and warm. These sensations are generally pleasant (with a little practice, at least). Most important, they contradict the twisted, agonizing, nauseating, deadening, numbing sensations associated with the immobility state. It seems likely that the change in the afferent messages (from organs to brain) allows the 90% of the sensory (ascending) vagus nerve to powerfully influence the 10% going from brain to organs so as to restore balance.v

Porges concurs on this key regulatory system: “The afferent feedback from the viscera provides a major mediator of the accessibility of prosocial circuits associated with social engagement behaviors.”78

The salubrious sensations evoked by the combination of breathing and the sound’s reverberations allow the individual to contact an inner security and trust along with some sense of orientation in the here and now. They also facilitate a degree of face-to-face, eye-to-eye, voice-to-ear, I-thou contact and thus make it possible for the client to negotiate a small opening into the “social engagement system,” which is then able to help him or her to develop a robust resilience through increasing cycles of sympathetic arousal (charge) and discharge and thereby to deepen regulation and relaxation. Charles Darwin, I can happily imagine, would have knowingly winked his approval at the “voo” clinical application of his astute, anatomical and physiological 1872 observation.

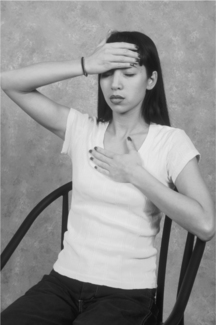

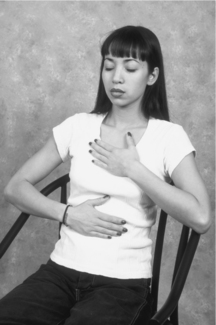

Another exercise can provide clients with a way to manage and regulate distressing arousal symptoms. This “self-help” technique is taken from a system of “energy flows” called Jin Shin Jyutsu.w Figures 6.5A–D demonstrate a simple Jin Shin sequence to help clients learn to regulate their arousal and deepen their relaxation.79 Again, I suggest that therapists experiment first on themselves before teaching these exercises to their clients. Encourage your clients to practice at home, first at times when they are not upset and then when they are. Each position can be maintained for two to ten minutes. What the client looks for is a sensation of either energy flow or relaxation.

Figure 6.5a These figures show the arm/hand positioning that help to establish energy flows between upper and lower body segments. These exercises promote relaxation.

Figure 6.5b

Figure 6.5c These figures show the arm/hand positioning for containing arousal and promoting self-compassion.

Figure 6.5d

In 1932 Sir Charles Sherrington received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for showing that the nervous system is made up of a combination of excitatory and inhibitory nerve cells. It is the balance of these two neural systems that allows us to move our limbs in a smooth, coordinated, accurate way. Without inhibition, our movements would be wildly spastic and uncoordinated. While Sherrington’s work was primarily on the sensory/motor system (at the level of the spinal cord), the balancing of excitatory systems by inhibitory ones occurs throughout the nervous system and is considered a fundamental principle of it. This organization is the basic architecture of self-regulation. Let us look at an analogy from ordinary life:

In its simplest form (mechano-electric) regulation is what allows our house temperature to be kept in a comfortable range, regardless of the outside temperature. So let us say that on a winter’s day we would like to keep the indoor temperature at a comfortable 70 degrees. To do this, we would set the thermostat at the desired temperature. This turns on the furnace. However, the furnace is not turned on all the time. If it were, the temperature would continue to rise, and we would have to open windows to bring the temperature down. But then, as the temperature dropped, we would have to close the window. The reason that we don’t have to do all of this is that the temperature is controlled by a negative feedback loop. Like Sherrington’s inhibitory system, the temperature rises, say to 72 degrees, and the furnace shuts off until the temperature drops to 68 degrees, at which time the furnace turns on again. This brings the temperature back to 72 degrees, giving us an average temperature of 70 degrees. With the aid of a light cotton sweater, a relatively comfortable environment is reached. If, on the other hand, the furnace were to turn up as the temperature rose, we would have rather quite an uncomfortable situation. Not only would we have to take our pullover off, but we would soon be going around the house stark naked. In the first example we have a smoothly regulated temperature mediated by a negative feedback system (with positive consequences). In the second situation, we have a positive feedback loop with negative consequences; our house becomes a sauna and sweat lodge.

In distress and trauma, I believe that a positive feedback loop, with extremely negative consequences, is set up. Indeed, most of us recognize that primal negative emotions readily turn into self-reinforcing, runaway positive feedback loops. Fear and anger can readily explode into terror and rage. Here trauma is the ouroboros, the serpent swallowing its own tail, eternally re-creating itself.

In the reciprocal enervation discovered by Sherrington, the nervous system operates primarily as a negative feedback system much like—but infinitely more complicated than—a house thermostat. Self-regulation of the complex nervous system exhibits what are called emergent properties, which are often somewhat unpredictable and rich in nuance. They frequently lead to finding new and creative solutions and are cherished when they happen in life and in psychotherapy. So while the nervous system operates under the principle of self-regulation, the psyche operates under the emergent properties of creative self-regulation. We might say that as the nervous system self-regulates, the psyche engages with these emergent properties: that is, to creative self-regulation. The relationship between the viscera and the brain is a complex self-regulating system. The richness of creative emergent properties allows these “sounding” and breathing techniques (like the “voo” sound) to initiate change throughout the nervous system. In a situation of inescapable and mortal threat, the brain stem, or reptilian brain, sends intense signals to the viscera, causing some of them to go into hyperdrive (as with the gastrointestinal system) and others to constrict and close down, as with the bronchioles of the lungs or the beating of the heart. In the first instance (hyperdrive), we get symptoms like butterflies, knots in the gut or rumbling, uncontrollable diarrhea. With the lungs, we have feelings of tightness and suffocation, which, when chronic, can lead to the symptoms of asthma. Likewise, the effect of the primitive vagus on the heart is to decrease the beat to a level so low that it can actually lead to (voodoo) death.80 Because these sensations feel so dreadful, they themselves become the source of threat. So rather than coming from outside, the threat now emanates from deep within one’s bowels, lungs, heart and other organs and can cause the exact same effect upon the viscera that the original threat evoked. This situation is the unfortunate setup for a positive feedback loop with disastrous negative consequences. In addition, because traumatized individuals are experiencing (intense) threat signals, they project this inner turmoil outward and thus perceive the world as being responsible for their inner distress—and so remove themselves from both the real source of the problem and its potential solution. This dynamic also wreaks havoc not only on the body but also on relationships.

The “voo” sound—by, first of all, focusing awareness upon the inner locus of the real problem—allows one to begin to change one’s experience from dreadful to pleasant and thus moves the situation from being a positive feedback loop (with negative consequences) to being a negative feedback loop, which helps restore homeostatic balance, equilibrium and, hence, feelings of goodness. This shift, even if only brief, opens an opportunity for the client to experience the warmth of the supportive therapeutic relationship, which, in turn, also provides a buffer against the rush of (sympathetic) hyperarousal soon to follow. Then the self-regulatory system (negative feedback loop) brings down arousal, allowing for much deeper, more stable and enduring sensations of goodness, as well as a more resilient nervous system and psyche.

* Merriam-Webster’s definition of organism is “a complex structure of interdependent and subordinate elements whose relations and properties are largely determined by their function in the whole.” Organism describes a wholeness, which derives not from the sum of its individual parts (i.e., bones, chemicals, muscles, nerves, organs, etc.); rather, it emerges from their dynamic, complex interrelation. Body and mind, primitive instincts, emotions, intellect, and spirituality all need to be considered together in studying the organism.

† Namely, in the cartilaginous and even jawless fish, in which it regulates metabolic energy conservation.

‡ Any situation that can increase one’s sense of safety has the potential of enlisting the evolutionarily more advanced neural circuits that support the behaviors of the social engagement system.

§ For a thorough discussion of the structure and complexities of dissociation, the reader is referred to the following comprehensive article: van der Hart, O., Nijenhuis, E., Steele, K., & Brown, D. (2004). Trauma-Related Dissociation: Conceptual Clarity Lost and Found. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 38, 906–914. These authors define dissociation, contextually, thus: “Dissociation in trauma entails a division of an individual’s personality, that is, of the dynamic, biopsychosocial system as a whole that determines his or her characteristic mental and behavioral actions. This division of personality constitutes a core feature of trauma. It evolves when the individual lacks the capacity to integrate adverse experiences in part or in full, can support adaptation in this context, but commonly also implies adaptive limitations. The division involves two or more insufficiently integrated dynamic but excessively stable subsystems.”

‖ Jacksonian dissolution is, essentially, the precursor of Paul McLean’s triune brain theory. See McLean’s The Triune Brain in Evolution: Role in Paleocerebral Functions (New York: Springer, 1990).

a It is most probable that sensory afferents, both from the external senses (e.g., sight and sound) and from the interior of the body (from muscles, viscera and joints), converge in the thalamus at the uppermost portion of the brain stem and, from there, proceed to the insula and cingulate cortex.

b While brain maps are useful, these are somewhat artificial situations, as fMRIs are more like static snapshots of dynamic brain circuitries.

c Remember that because fMRIs are fixed images, they would not be able to pick up such dynamic changes.

d To make matters more complex, one often observes indications of concurrent combinations of sympathetic arousal and parasympathetic (vagal immobility) activation. This occurs particularly at high-stress and transition points. Concomitant indicators include low heart rate (vagal/parasympathetic) along with cold hands (sympathetic).

e It can also be evoked by intense and unremitting stress.

f The social engagement system controls the voice, ear and facial muscles, which are all used together in nuanced communication.

g Screenwriter William Broyles Jr. actually spent a full week marooned on a desert island, and many aspects of the 2000 film were informed by his firsthand experiences.

h The power of simple contours representative of the human face may trace back to an innate pattern recognition that is already functioning just after birth. A number of clever experiments have been devised, all showing that the newborn is drawn preferentially to simple (curving) contours and not attracted, for example, to angular shapes.

i Indeed, the brain stem’s immobilization system is the “root” of the default hierarchy.

j These same brain regions (in the medial temporal lobe) that process memory and emotion, when malfunctioning, contribute to delusions of identity. To people with injury here, their mother looks and sounds exactly as she should, but they have lost the sensation of her presence; she seems somehow unreal.

k Along with the vestibular system, this is how we know where we are in gravity space.

l These figures are taken from Healing Trauma: A Pioneering Program for Restoring the Wisdom of Your Body written by Peter Levine and published by Sounds True. Used with permission from Sounds True, www.soundstrue.com.

m This diffuse brain lines the entire alimental canal (almost 30 feet from the esophagus to the anus).

n It should be noted that excess levels of serotonin in the gut also lead to problematic states.

o Motor neurons that act on the viscera are called viscero-motor neurons.

p In addition, there are multiple and bidirectional “neuropeptide” systems studied by Candice Pert and others. See Pert et al.’s Molecules of Emotion: The Science behind Mind-Body Medicine (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1999).

q It is interesting that many autistic children have GI abnormalities. See Hadhazy, A. (2010). Think Twice: How the Gut’s “Second Brain” Influences Mood and Well-Being. Scientific American, February 12.

r As previously mentioned, many people experience a combination of sympathetic and vagal hyperactivity—a fact that makes the symptom profile more complex. For example, in the case of patients diagnosed with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) or “spastic colon,” there is often a vacillation between constipation and diarrhea.

s Therapists may be taken aback when certain clients perceive them as a threat or as either a hero or a villain.

t Many medical texts still teach that no sensations or feelings arise from the guts. The only thing we feel in our guts, they say, is pain—and then only when the pain is referred to areas like the lower back.

u I recommend the wonderful Swedish film As It Is in Heaven (2004).

v See the next section for a more detailed explanation of how feedback influences core regulation.

w Jin Shin Jyutsu®, an ancient healing system for “harmonizing the life energy in the body,” has been passed down from generation to generation by apprenticeship. The art fell into obscurity until the early 1900s when it was dramatically revived by Master Jiro Murai in Japan and then brought to the United States by Mary Burmeister. In 1979, I had the privilege of meeting this vital octogenarian in Scottsdale, Arizona, where she continued to practice and teach well into her eighties.